ABSTRACT

Background: Lasmiditan is a selective serotonin (1F) receptor agonist approved for acute treatment of migraine with 3 doses: 50, 100, and 200 mg.

Objective: To help provide dosing insights, we assessed the efficacy and safety of lasmiditan in patients who treated two migraine attacks with the same or different lasmiditan doses.

Methods: Integrated analyses used data from the migraine attack treated in either of two controlled, Phase 3, single attack studies (SAMURAI/SPARTAN), and after the first attack treated in the open-label GLADIATOR extension study. Eight patient groups were created based on the initial dose received in SAMURAI or SPARTAN and the subsequent dose in GLADIATOR: placebo-100, placebo-200, 50–100, 50–200, 100–100, 100–200, 200–100, 200–200. Migraine pain freedom, migraine-related functional disability freedom, most bothersome symptom (MBS) freedom, and pain relief were evaluated at 2-h post-dose. The occurrence of most common treatment-emergent adverse events (MC-TEAE) was evaluated. Shift analyses were performed for pain freedom and ≥1 MC-TEAE. The incidence of patients with a specific outcome from the first and subsequent doses were compared within each dose change group using McNemar’s test.

Results: Small, but consistent, increases in incidences of pain freedom, migraine-related functional disability freedom, MBS freedom, and pain relief occurred when the second lasmiditan dose was higher than the initial dose. For patients starting on 50 mg, increasing to 100 or 200 mg provided a positive efficacy-TEAE balance, despite an increase in incidence of ≥1 MC-TEAE. For patients starting on 100 mg, increasing to 200 mg provided a positive efficacy-TEAE balance. If the initial dose was 100 or 200 mg, the incidence of patients experiencing ≥1 MC-TEAE decreased or stayed the same with their subsequent dose, regardless of dose. Decreasing from 200 to 100 mg led to a decrease in patients with pain freedom and ≥1 MC-TEAE, resulting in a neutral efficacy-TEAE balance. Shift analyses supported these findings.

Conclusion: A positive efficacy-TEAE balance exists for patients increasing their lasmiditan dose for treatment of a subsequent migraine attack. These results could be important for optimizing dosing for individual patients.

Clinicaltrials.gov: SAMURAI (NCT02439320); SPARTAN (NCT02605174); GLADIATOR (NCT02565186).

1. Introduction

Lasmiditan, a selective serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) 1F receptor agonist approved in the United States (US) for the acute treatment of migraine in adults [Citation1], is a first-in-class ditan [Citation2], which has a different structure and mechanism of action than triptans utilized for treatment of migraine [Citation3]. Evidence suggests that lasmiditan exerts its therapeutic effects by decreasing neuropeptide release and inhibiting pain pathways, without causing vasoconstriction [Citation3]. Lasmiditan’s high lipophilicity and the locations of 5-HT1F receptors suggest that lasmiditan acts on both the peripheral and central nervous systems [Citation3–9]. As lasmiditan was recently approved in the US for the acute treatment of migraine, with 3 efficacious doses (50, 100, and 200 mg) [Citation1], examination of the effect of changing lasmiditan dose from initial to subsequent migraine attacks on efficacy and safety could help guide healthcare providers in making dosing decisions for their patients.

The first two Phase 3 studies (SAMURAI and SPARTAN) with lasmiditan were similarly designed for treatment of a single migraine attack [Citation10,Citation11]. Based on data from these studies, all doses (50 [SPARTAN only], 100 and 200 mg) of lasmiditan resulted in a significantly greater proportion of patients who experienced pain freedom, migraine-related functional disability freedom, most bothersome symptom (MBS) freedom, and pain relief at 2 hours after dosing compared to placebo [Citation12]. Lasmiditan was also associated with a dose-dependent increase in the incidence of adverse events. These events were generally mild or moderate in severity and of limited duration [Citation13]. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (MC-TEAEs) were dizziness, fatigue, paresthesia, sedation (includes somnolence), nausea and/or vomiting, and muscle weakness [Citation2]. Post hoc analyses of SAMURAI and SPARTAN data showed a positive correlation between efficacy and the most common TEAEs [Citation13–15], which could be a factor for healthcare providers and their patients in making dosing decisions.

The open-label Phase 3 study, GLADIATOR, was designed to assess the long-term safety and efficacy of lasmiditan treatment (100 and 200 mg) for multiple migraine attacks [Citation16]. The incidence of TEAEs and the most common TEAEs were consistent with the single attack studies and TEAE frequency decreased with subsequent-treated attacks. Conversely, incidence of pain freedom and other efficacy outcomes remained similar over time across multiple-treated attacks [Citation16]. Understanding that the incidence of TEAEs may go down while the efficacy may remain constant across subsequent lasmiditan treatments for migraine attacks over time may help inform treatment decisions.

The purpose of this study was to assess the effects of a change in lasmiditan dose on drug efficacy and safety for the treatment of a single migraine attack in SAMURAI or SPARTAN and the first migraine attack experienced in the follow-up GLADIATOR study. This study assesses the efficacy and safety of lasmiditan across treatment of 2 migraine attacks as an initial dose and a subsequent dose. The current results provide information relevant to choosing the first lasmiditan dose for treating a migraine attack and subsequent dose for treating another migraine attack when lasmiditan 50, 100, and 200 mg choices are available.

2. Methods

Data for these analyses come from studies, which were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and internationally accepted standards of Good Clinical Practice. All patients gave written informed consent before enrollment.

2.1. Study designs

SAMURAI (NCT02439320) and SPARTAN (NCT02605174) were double-blind, single attack, Phase 3 migraine acute treatment studies in which patients with migraine were randomly assigned to lasmiditan 50 mg (SPARTAN only), 100 mg, 200 mg, or placebo. Details of study design, including randomization, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, and outcome measures were previously described () [Citation10,Citation11].

Figure 1. Study designs of SAMURAI, SPARTAN, and GLADIATOR

GLADIATOR (NCT02565186), a prospective, open-label Phase 3 study, consisted of patients who had completed either SAMURAI or SPARTAN, met study entry criteria, and opted to enter GLADIATOR. It was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of treating multiple migraine attacks for up to 1 year with lasmiditan. Patients were rerandomized to either lasmiditan 100 mg or 200 mg () [Citation16]. Neither a lasmiditan 50-mg treatment arm nor a placebo or active comparator was available in GLADIATOR.

For both safety and efficacy analyses, eight patient groups were created based on the initial dose received in SAMURAI or SPARTAN and the subsequent dose received in GLADIATOR (SAMURAI/SPARTAN dose-GLADIATOR dose): placebo-100, placebo-200, 50–100, 50–200, 100–100, 100–200, 200–100, 200–200.

2.2. Analysis populations

The current analyses included only the patients from SAMURAI or SPARTAN who were randomly assigned in GLADIATOR.

All efficacy assessments were conducted on data from patients that were in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population of SAMURAI or SPARTAN and GLADIATOR. The ITT population consisted of randomly assigned patients who took a dose of study drug and who recorded any post-dose headache severity or symptom assessments. Patients were encouraged not to take their dose until the migraine pain was either moderate or severe per the study protocol. Less than 2.0% of patients (total) had mild pain severity at the time of dosing.

The safety population consisted of randomly assigned patients who took a dose of study drug in SAMURAI or SPARTAN and GLADIATOR, regardless of whether they underwent any study assessments. The safety population was used for the demographics, patient characteristics, and safety analyses.

2.3. Outcomes

The efficacy endpoints were pain freedom, migraine-related functional disability freedom, MBS freedom, or pain relief at 2 hours after the first dose and defined in the original reports [Citation10,Citation11,Citation16]. Pain freedom is the reduction in headache severity from mild, moderate, or severe at baseline to none at the indicated assessment time. Migraine-related functional disability freedom is the reduction in migraine-related functional disability from ‘mild interference’, ‘marked interference’, or ‘need complete bed rest’ at baseline to ‘not at all’. MBS freedom is the complete resolution of either nausea, phonophobia, or photophobia as designated at baseline. Pain relief is the decrease in pain from severe or moderate to none or mild, or reduction from mild to none. The incidence of patients who met each efficacy parameter was assessed for the treated attack in SAMURAI or SPARTAN (first dose) and assessed again for the first attack treated in GLADIATOR (subsequent dose).

Safety assessments were based on the incidence of patients with ≥1 MC-TEAE within 48 hours of treatment dose. A MC-TEAE is a TEAE that occurred in ≥2% of lasmiditan-treated patients after rounding and more frequently than placebo in SAMURAI and SPARTAN. Most common TEAEs included dizziness, fatigue (includes asthenia and malaise), paresthesia (includes paresthesia oral, hypoesthesia, and hypoesthesia oral), sedation (includes somnolence), nausea and/or vomiting (includes both terms), and muscular weakness. Safety assessments were conducted in SAMURAI or SPARTAN and in GLADIATOR separately.

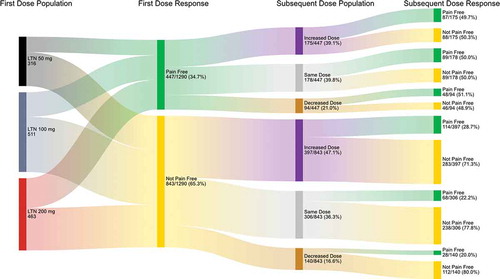

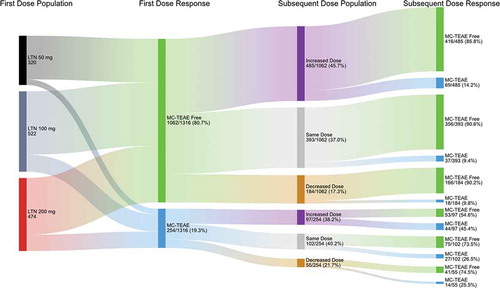

The eight dosing patient groups were assessed for efficacy and safety shifts from one dosed attack to the next-dosed attack: pain-free to pain-free, pain-free to not pain-free, not pain-free to not pain-free, and not pain-free to pain-free; MC-TEAE free to MC-TEAE free, MC-TEAE free to not MC-TEAE free, not MC-TEAE free to not MC-TEAE free, and not MC-TEAE free to MC-TEAE free.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Summary statistics were used to generate baseline demographic and patient characteristics, including frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, as well as for means and standard deviations for continuous variables.

To evaluate how a change in dose affects efficacy, the percentage of patients who achieved pain freedom at 2 hours after the first dose and the subsequent dose for each dose change group was analyzed. McNemar’s test was used to assess whether the incidence of patients who achieve efficacy outcomes were different between the first and subsequent dose and a p-value was reported for each dose change group.

The number of patients who shifted their response status from the first dose to the subsequent dose was summarized in each dose change group. A Fisher’s exact test was used to statistically compare the most clinically relevant shifts. For patients with a first dose of PBO, 50 mg, or 100 mg who did not achieve pain freedom at 2 hours, the association between a patient’s subsequent dose of lasmiditan 100 or 200 mg and whether or not they achieved pain freedom with their subsequent dose were evaluated. For patients with a first dose of lasmiditan 200 mg who achieved pain freedom at 2 hours, the association between a patient’s subsequent dose of lasmiditan 100 or 200 mg and whether or not they achieved pain freedom with their subsequent dose were evaluated. These analyses were repeated for migraine-related functional disability freedom, MBS freedom, and pain relief. Additionally, for patients with a first dose of PBO, 50 mg, or 100 mg who were MC-TEAE free, the association between a patient’s subsequent dose of lasmiditan 100 or 200 mg and whether or not they were MC-TEAE free with their subsequent dose were evaluated. For patients with a first dose of lasmiditan 200 mg who were not MC-TEAE free, the association between a patient’s subsequent dose of lasmiditan 100 or 200 mg and whether or not they were not MC-TEAE free with their subsequent dose were evaluated.

All statistical tests conducted were 2-sided. Any p-value of less than 0.05 indicates statistical significance. All analyses were performed using the software SAS Enterprise Guide Version 7.1.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

Baseline patient characteristics and demographics were similar between patients who had the same first dose but different subsequent dose. At baseline, across eight dose change patient groups, the range of sample size was 159 to 304 patients. Over 80% of patients were female. Most subjects had moderate or severe pain at baseline. The mean duration of migraine history was around 18 to 19 years and the range of the average migraines per month was 5.1 to 5.3 in the past 3 months (). Patients across dose groups for each study included in the current analyses were balanced for patient and disease characteristics, including comorbidities and concomitant medications [Citation10,Citation11,Citation16,Citation17].

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics and demographics

3.2. Efficacy and treatment-emergent adverse events

3.2.1. First dose: 50 mg

3.2.1.1. Increase subsequent dose

Increasing lasmiditan dose from 50 mg for a single migraine attack in SPARTAN to a 100- or 200-mg dose for the first migraine attack in GLADIATOR consistently improved the rate of pain freedom (50–100 = 29.5–31.4%; 50–200 = 33.1–38.1%) (), migraine-related functional disability freedom (50–100 = 33.3–36.4%; 50–200 = 36.6–40.8%) (), MBS freedom (50–100 = 46.8–47.6%; 50–200 = 48.4–59.4%, p <0.05) (), and pain relief (50–100 = 63.2–72.8%, p <0.05; 50–200 = 61.5–73.0%, p <0.05) (). Increasing from lasmiditan 50 to 100 or 200 mg increased the incidence of patients with ≥1 MC-TEAE from 10.7% to 17.0%, a 6.3% change, and 12.4% to 16.8%, a 4.4% change, respectively (, ). This increased incidence of having ≥1 MC-TEAE is less than the increase in incidence of pain relief (difference of 9.6% and 11.5%, respectively) ().

Figure 2. Efficacy outcomes for the first dose and subsequent dose

Figure 3. Incidence of patients who experienced at least one MC- TEAE with the first dose and subsequent dose

Table 2. Efficacy-TEAE balance change from first dose to subsequent dose

Table 3. Pain freedom (a), Disability freedom (b), Most bothersome symptom freedom (c), Pain relief (d), and Most common treatment-emergent adverse event MC-TEAE freedom (e) – Distribution of patients in each of four outcome shift categories by dose scheme

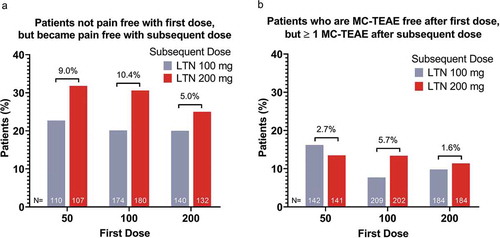

For patients who were not pain-free after taking lasmiditan 50 mg, changing to 200 versus 100 mg to treat the second migraine attack resulted in a greater percentage (9.0% difference) of patients experiencing pain freedom (). For patients who were MC-TEAE free after taking lasmiditan 50 mg, taking lasmiditan 200 versus 100 mg to treat a subsequent attack did not result in a greater percentage of patients experiencing a MC-TEAE ().

Figure 4. Incidence of pain-free patients after the subsequent dose among patients who were not pain-free after the initial dose (a); incidence of patients not MC-TEAE free after the subsequent dose among patients who were MC-TEAE free after the initial dose (b)

While supporting the currently described trends, increasing the dose from lasmiditan 50 to 200 mg did not result in a significant difference in the 2-h shift analysis from not pain-free to pain-free (). There was, however, a significantly (p <0.05) greater incidence of patients shifting from not MBS free to MBS free with increasing lasmiditan dose from 50 to 200 mg (24.2%) versus an increase from 50 to 100 mg (15.3%) ().

3.2.1.2. Same subsequent dose

Based on study design, there are no data available to assess the effect of treating a patient’s first migraine attack with lasmiditan 50 mg and then repeating the same dose for a second migraine attack.

3.2.1.3. Decrease subsequent dose

Based on study design, there are no data available to assess the effect of treating a patient’s first migraine attack with lasmiditan 50 mg and then placebo for a second migraine attack.

3.2.2. First dose: 100 mg

3.2.2.1. Increase subsequent dose

Increasing lasmiditan dose from 100 mg to 200 mg (100–200) consistently improved the rate of pain freedom (29.7–35.5%) (), migraine-related functional disability freedom (34.9–40.7%) (), MBS freedom (43.5–48.9%) (), and pain relief (65.0–70.1%) (). Increasing the lasmiditan dose from 100 to 200 mg did not relevantly change the incidence of patients with ≥1 MC-TEAEs (0.4% decrease) ().

For patients who were not pain-free after taking lasmiditan 100 mg, changing to 200 versus 100 mg to treat the second migraine attack resulted in a greater percentage (10.4% increase; p <0.05) of patients experiencing pain freedom (, ). For patients who were MC-TEAE free after taking lasmiditan 100 mg, changing to 200 mg versus 100 mg to treat a subsequent attack resulted in a higher percentage of patients (5.7% difference) experiencing a MC-TEAE ().

3.2.2.2. Same subsequent dose

Repeating the lasmiditan 100-mg dose (100–100) resulted in small decreases in the incidence of patients with pain freedom (31.8–29.0%) () and migraine-related functional disability freedom (36.6–33.0%) (), similar incidence of MBS freedom (43.8–43.3%) (), and an increase in pain relief (63.6–66.7%) (). Repeating the 100-mg dose also resulted in a decreased incidence of patients with ≥1 MC-TEAE from 19.6% to 10.0% (p <0.05) ().

3.2.2.3. Decrease subsequent dose

Based upon study design, there are no data available to assess the effect of treating a patient’s first migraine attack with lasmiditan 100 mg and then decreasing the dose for a second migraine attack.

3.2.3. First dose 200 mg

3.2.3.1. Increase subsequent dose

Based upon study design, there is no data available to assess the effect of treating a patient’s first migraine attack with lasmiditan 200 mg and then increasing the dose for a second migraine attack.

3.2.3.2. Same subsequent dose

Repeating the lasmiditan 200-mg dose (200–200) led to a decrease in rate of pain freedom (42.4–36.2%) () and migraine-related functional disability freedom (43.9–38.3%) (), whereas MBS freedom (49.4–50.0%) () and pain relief (69.0–70.0%) () rates stayed approximately the same. Repeating the 200-mg dose also resulted in a decreased incidence of patients with ≥1 MC-TEAE from 21.7% to 16.2% ().

3.2.3.3. Decrease subsequent dose

Decreasing lasmiditan dose from 200 mg to 100 mg (200–100) decreased the rate of pain freedom (40.2–32.5%, p <0.05) (), whereas migraine-related functional disability freedom (41.1–40.5%) () and MBS freedom (51.2–48.8%) () stayed approximately the same, while pain relief improved (64.1–71.8%) (). Decreasing the lasmiditan dose from 200 to 100 mg decreased the incidence of patients with ≥1 MC-TEAE from 23.0% to 13.4% (p <0.05) ().

For patients who were pain-free at 2 hours after taking lasmiditan 200 mg, changing to 100 or repeating the 200-mg dose resulted in a similar incidence of patients shifting from pain-free to not pain-free (19.7% versus 20.5%, respectively; (). Patients who experienced ≥1 MC-TEAE after a 200-mg dose to treat their first attack and decreased their subsequent dose to 100 mg, had a lower incidence of ≥1 MC-TEAE (5.9%) compared to those patients who took the same dose for their second attack (7.2%) (). For patients who were MC-TEAE free after taking lasmiditan 200 mg, changing to 100 or 200 mg resulted in a similar incidence of patients shifting from MC-TEAE free to not MC-TEAE free (7.5% versus 8.9%, respectively; ().

3.2.4. Efficacy and adverse event outcome shifts independent of first dose

Regardless of starting dose, for patients still having pain after taking an initial lasmiditan dose, increasing the dose for a subsequent migraine attack resulted in an increased incidence of patients becoming pain-free (28.7%) versus patients remaining on the same dose or decreasing their dose (22.2% and 20.0%, respectively) (). Conversely, if a patient was pain-free after taking an initial dose, changing lasmiditan dose did not seem to impact the incidence of pain freedom after subsequent dose. Regardless of whether a patient was or was not MC-TEAE free after taking an initial lasmiditan dose, increasing dose for treatment of the subsequent migraine attack was associated with a lower incidence of patients who were MC-TEAE free versus patients who remained on the same dose (). Of patients who were MC-TEAE free (80.7%) for their first dose, 90.6% remaining on the same dose and 85.8% who took an increased dose were MC-TEAE free for their second dose. Of patients who were not MC-TEAE free (19.3%) for their first dose, 73.5% remaining on the same dose and 54.6% who took an increased dose were MC-TEAE free for their second dose.

Figure 5. Effect of changing lasmiditan dose on pain response based on pain outcome after the first treated attack

Figure 6. Effect of changing lasmiditan dose on the percentage of patients experiencing a MC-TEAE based on whether a MC-TEAE was experienced with treatment of the first attack

4. Discussion

Making lasmiditan dosing decisions can depend on multiple factors, including the weight or magnitude of an increased chance at pain freedom versus that of an increased chance of a MC-TEAE occurring. We examined the effect of lasmiditan dose change on efficacy and adverse event outcomes in patients who took either placebo, lasmiditan 50, 100, or 200 mg to treat a single migraine attack in SAMURAI or SPARTAN studies compared to the first attack treated in the extension GLADIATOR study in which patients were randomly assigned to take lasmiditan 100 or 200 mg (first dose and subsequent dose, respectively). In these analyses, various lasmiditan dose combinations were assessed: placebo-lasmiditan 100 mg, placebo-lasmiditan 200 mg, lasmiditan 50–100, 50–200, 100–100, 100–200, 200–200, and 200–100 mg. The objective for these post hoc analyses was to investigate the efficacy and safety of lasmiditan-lasmiditan dose combinations. The placebo-lasmiditan dose groups were included as a reference to assess consistency with the primary studies.

The number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve efficacy outcomes at 2 hours post-treatment relative to placebo has previously been reported [Citation12], which supports a dose-related efficacy response. The NNT for pain freedom was 10 with lasmiditan 50 mg, 9 with 100 mg, and 6 with 200 mg; for pain relief was 7 with 50 mg, 6 with 100 mg, and 6 with 200 mg; for MBS freedom was 11 with 50 mg, 9 with 100 mg, and 8 for 200 mg [Citation12]. Furthermore, a higher incidence of patients who experience positive efficacy outcomes appears to occur in those who have a TEAE than those who do not [Citation13–15]; this is an important consideration when deciding on lasmiditan dosing options. Understanding MC-TEAE incidence for an initial starting dose versus a subsequent dose across multiple attacks over time is important in considering the efficacy versus TEAE trade-off decisions.

In the current analyses, increasing the subsequent dose improved the rate of pain freedom, migraine-related functional disability freedom, MBS freedom, and pain relief. While mean differences were small and generally not statistically significant, the trends in these exploratory analyses were consistent and suggestive of a positive efficacy-TEAE balance when increasing lasmiditan dose over time. For example, if a patient took 50 mg and then 100 or 200 mg, they had a greater chance of efficacy as well as an increased chance at having ≥1 MC-TEAE; however, the efficacy-TEAE balance was positive. For patients who started on 50 mg for treatment of their first attack and then switched to 200 mg for treatment of their second attack, the increase in incidence of pain relief was 2.6-fold greater than the increase of ≥1 MC-TEAE. Increasing an initial lasmiditan dose from 50 or 100 mg to 200 mg for future migraine attacks may be beneficial to maximize the patients’ chance at pain freedom, while still providing a tolerable safety profile. If tolerability is not adequate, waiting to increase the dose may be a preferred option. This conclusion is supported with data showing that lasmiditan efficacy is maintained over multiple-treated migraine attacks while the likelihood of having a MC-TEAE goes down [Citation16,Citation18].

For patients who took the same lasmiditan dose for treatment of both their first and second migraine attack, the efficacy-TEAE balance seemed to be neutral. Continuing an efficacious dose may be advantageous for some patients, even if they have some TEAEs, because the incidence and severity of MC-TEAEs may diminish with treatment of subsequent migraine attacks as early as the second migraine attack treatment [Citation16,Citation18]. This phenomenon was observed in the current analyses, where the incidence of patients experiencing ≥1 MC-TEAE was similar or decreased from the first lasmiditan dose to the subsequent dose if the initial dose was 100 or 200 mg. This concept can be important for patients to understand as ascertainment of an acceptable steady state efficacy-TEAE balance with lasmiditan for an individual patient may require assessment of multiple-treated migraine attacks.

Treatment with lasmiditan 200 mg followed by 200 mg resulted in decreased pain freedom. This finding is not consistent with GLADIATOR multi-attack lasmiditan 200-mg dosing data that demonstrated stable levels of efficacy response across migraine attacks with lasmiditan 200-mg treatment [Citation16,Citation18]. In CENTURION, a randomly assigned, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase 3 study specifically designed to study consistency of effect across migraine attacks, both lasmiditan 100 and 200 mg were significantly superior to placebo in the proportion of patients obtaining pain freedom 2-h post-dose in at least 2 out of 3 treated migraine attacks [Citation19]. Lasmiditan was also superior to placebo for the gated secondary endpoint, pain relief at 2-hours post-dose in at least 2 out of 3 treated migraine attacks [Citation19]. These data support intra-patient consistency of response to the effect of lasmiditan for the first and subsequent dose treatments.

For patients who decreased their dose for their second attack, the efficacy-TEAE balance seemed to be relatively neutral, driven by decreased incidence of having ≥1 MC-TEAE. For example, for patients who decreased lasmiditan dose from 200 to 100 mg, the incidence of pain freedom and MBS freedom worsened, while migraine-related functional disability stayed the same and pain relief improved; however, the incidence of having ≥1 MC-TEAE decreased. For this example, a patient’s decrease in chance at pain freedom was less than their decreased chance of having a MC-TEAE.

In fact, for all dose combinations that resulted in increased incidence of ≥1 MC-TEAE for the subsequent dose, the magnitude of increase in pain relief exceeded the magnitude of increase in the incidence of patients experiencing ≥1 MC-TEAE. Moreover, patients starting on lasmiditan 100 or 200 mg had an increase in incidence of pain relief, while having a decrease in incidence of MC-TEAE regardless of which dose they received to treat their second attack.

Starting lasmiditan dose and dose adjustment optimization are likely to be affected by an individual patient’s physiology, tolerance, and personal needs. Ultimately, dosing optimization should be dependent on the patient and the relative importance of treatment attributes to the patient. If a patient initially does not see a benefit, the chance of having satisfactory results may be increased with dose optimization and additional lasmiditan use. The current results could be important for dosing decisions, particularly if a patient prioritizes a chance at pain freedom over a chance of having a mild to moderate common TEAE of short duration.

4.1. Limitations

There were several limitations in this study. The original Phase 3 studies were not specifically designed or powered to study dose change effects between studies for these post hoc exploratory analyses, and the sample sizes, especially for the shift group comparisons, were relatively small. While trends were consistent, it is possible that the 0 to 10% differences in incidence of patients from first to second dose assessments observed could be associated with normal variation.

SAMURAI and SPARTAN were placebo-controlled double-blinded studies whereas GLADIATOR was open-label. Patients who entered GLADIATOR who were previously on study drug in SAMURAI or SPARTAN may be more likely to be lasmiditan responders and tolerant of lasmiditan. Examining patient results across studies may have added unforeseen and uncontrolled variables.

GLADIATOR only had two treatment arms, lasmiditan 100 and 200 mg; therefore, no comparisons involving placebo or 50 mg dose combinations could be made. Study design also resulted in the availability of only one decreased dose. Each attack has variability regarding migraine attack severity, duration, and symptom presence.

5. Conclusion

The current data suggest a positive efficacy-TEAE balance for patients increasing their lasmiditan dose for subsequent migraine attacks. For example, the efficacy-TEAE balance for lasmiditan 100 to 200 mg was positive, where patients’ incidence of positive efficacy increased across all assessments, while the incidence of patients with at least one MC-TEAE stayed the same.

These data suggest that if a patient:

Started on lasmiditan 50 mg, increasing their dose for treating subsequent migraine attacks may provide a more optimized efficacy-TEAE balance.

Started on lasmiditan 100 mg, it may be beneficial to switch to 200 mg for subsequent migraine attacks because there is potential for a gain in pain freedom without an increase in side effects or possibly even a reduction in side effects.

Had a good response resulting in pain freedom starting on lasmiditan 100 mg but experienced side effects, it may be worth trying 100 mg again, as side effects may be less likely to appear.

Had a good response resulting in pain freedom starting on lasmiditan 200 mg but experienced intolerable side effects, decreasing their dose can reduce side effects; in this case, the efficacy-TEAE balance may be neutral, trading reduced side effects for reduced pain freedom while being able to maintain pain relief.

The results of these analyses could be important for helping healthcare providers optimize dosing for individual patients prescribed lasmiditan, particularly if they prioritize a chance at pain freedom over a chance of having a MC-TEAE. Optimizing dosing for chronic neurological diseases, such as migraine, remains important to reduce discontinuation due to a lack of efficacy or intolerability.

Declaration of funding

Eli Lilly and Company sponsored this study.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

JA: Honoraria: Lundbeck, Allergan, Amgen, Axsome, Biohaven, Eli Lilly and Company, Impel, Satsuma, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Vorso. Speakers Bureau: Allergan, Biohaven, Lundbeck, Eli Lilly, Teva. Clinical trials: Allergan, Biohaven, Eli Lilly, Satsuma, and Zosano.

MP: Allergan, Eli Lilly and Company, Eurofarma, Libbs, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Teva.

DC, HH, YD and PH are employees/minor stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Geological information

SAMURAI was conducted at 99 sites in the United States. SPARTAN was conducted at 125 sites in the United States, United Kingdom and Germany. GLADIATOR was conducted at 199 study sites in the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany.

Declaration of interest

Other than declaration of financial/other relationships above, no potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored, funded, and supported by Eli Lilly and Company. The data from this study were presented in part at the June 15-30, 2020 62nd American Headache Society Annual Meeting. The authors would like to thank Jarrett Meyer, Eli Lilly Advanced Analytics and Data Sciences, for help with the shift analysis Sankey graphs.

Data availability

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

References

- ReyvowTM (lasmiditan) tablets. [Package insert]. Eli lilly and Company; [cited 2019 Nov 6]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/211280s000lbl.pdf

- Tfelt-Hansen PC, Pihl T, Hougaard A, et al. Drugs targeting 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors in acute treatments of migraine attacks. A review of new drugs and new administration forms of established drugs. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2014 Mar;23(3):375–385.

- Clemow DB, Johnson KW, Hochstetler HM, et al. Lasmiditan mechanism of action – review of a selective 5-HT1F agonist. J Headache Pain. 2020 Jun 10;21(1):71.

- Kovalchin J, Ghiglieri A, Zanelli E, et al. Lasmiditan acts specifically on the 5-HT1F receptor in the central nervous system. Cephalalgia. 2016;36(1_suppl):103.

- Labastida-Ramirez A, Rubio-Beltran E, Haanes KA, et al. Lasmiditan inhibits calcitonin gene-related peptide release in the rodent trigeminovascular system. Pain. 2020 May;161(5):1092–1099.

- Rubio-Beltran E, Labastida-Ramirez A, Villalon CM, et al. Is selective 5-HT1F receptor agonism an entity apart from that of the triptans in antimigraine therapy? Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Jun;186:88–97.

- Nelson DL, Phebus LA, Johnson KW, et al. Preclinical pharmacological profile of the selective 5-HT1F receptor agonist lasmiditan. Cephalalgia. 2010 Oct;30(10):1159–1169.

- Rubio-Beltran E, Labastida-Ramirez A, Haanes KA, et al. Characterization of binding, functional activity, and contractile responses of the selective 5-HT1F receptor agonist lasmiditan. Br J Pharmacol. 2019 Dec;176(24):4681–4695.

- Vila-Pueyo M. Targeted 5-HT1F therapies for migraine. Neurotherapeutics. 2018 Apr;15(2):291–303.

- Goadsby PJ, Wietecha LA, Dennehy EB, et al. Phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of lasmiditan for acute treatment of migraine. Brain. 2019 Jul 1;142(7):1894–1904.

- Kuca B, Silberstein SD, Wietecha L, et al. Lasmiditan is an effective acute treatment for migraine: a phase 3 randomized study. Neurology. 2018 Dec 11;91(24):e2222–e2232.

- Ashina M, Vasudeva R, Jin L, et al. Onset of efficacy following oral treatment with lasmiditan for the acute treatment of migraine: integrated results from 2 randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical studies. Headache. 2019 Nov;59(10):1788–1801.

- Krege JH, Rizzoli PB, Liffick E, et al. Safety findings from phase 3 lasmiditan studies for acute treatment of migraine: results from SAMURAI and SPARTAN. Cephalalgia. 2019 Jul;39(8):957–966.

- Smith T, Krege JH, Rathmann SS, et al. Improvement in function after lasmiditan treatment: post hoc analysis of data from phase 3 studies. Neurol Ther. 2020 May 23. DOI:10.1007/s40120-020-00185-5.

- Tepper SJ, Krege JH, Lombard L, et al. Characterization of dizziness after lasmiditan usage: findings from the SAMURAI and SPARTAN acute migraine treatment randomized trials. Headache. 2019 Jul;59(7):1052–1062.

- Brandes JL, Klise S, Krege JH, et al. Interim results of a prospective, randomized, open-label, Phase 3 study of the long-term safety and efficacy of lasmiditan for acute treatment of migraine (the GLADIATOR study). Cephalalgia. 2019 Oct;39(11):1343–1357.

- Clemow DB, Baygani SK, Hauck PM, et al. Lasmiditan in patients with common migraine comorbidities: a post hoc efficacy and safety analysis of two phase 3 randomized clinical trials. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;6:1–16.

- Brandes JL, Klise S, Krege JH, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of lasmiditan for acute treatment of migraine: final results of the GLADIATOR study. Cephalalgia Rep. 2020;3:2515816320958176.

- Migraine trust virtual 2020 – oral presentations. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(1_suppl):3–17.