ABSTRACT

Purpose of the Study

Obesity is a major risk factor for development and worsening of osteoarthritis (OA). Managing obesity with effective weight loss strategies can improve patients’ OA symptoms, functionality, and quality of life. However, little is known about the clinical journey of patients with both OA and obesity. This study aimed to map the medical journey of patients with OA and obesity by characterizing the roles of health care providers, influential factors, and how treatment decisions are made.

Study Design

A cross-sectional study was completed with 304 patients diagnosed with OA and a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2 and 101 primary care physicians (PCPs) treating patients who have OA and obesity.

Results

Patients with OA and obesity self-manage their OA for an average of five years before seeking care from a healthcare provider, typically a PCP. Upon diagnosis, OA treatments were discussed; many (61%) patients reported also discussing weight/weight management. Despite most (74%) patients being at least somewhat interested in anti-obesity medication, few (13%) discussed this with their PCP. Few (12%) physicians think their patients are motivated to lose weight, but almost all (90%) patients have/are currently trying to lose weight. Another barrier to effective obesity management in patients with OA is the low utilization of clinical guidelines for OA and obesity management by PCPs.

Conclusions

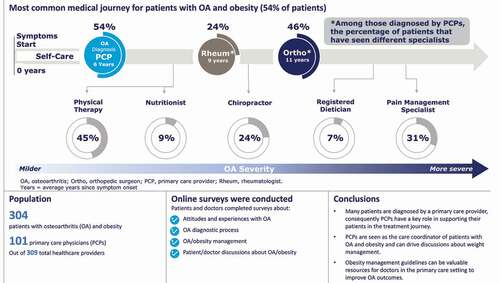

As the care coordinator of patients with OA and obesity, PCPs have a key role in supporting their patients in the treatment journey; obesity management guidelines can be valuable resources.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a disease where the soft tissue between joints wears out causing pain and swelling. Obesity, having unhealthy extra body weight, increases the chances of a person getting OA and can make their OA worse.

We wanted to learn more about what patients with OA and obesity experience as they try to manage their OA, including the doctors they talked to, the treatments they used, and if their weight was discussed. To better understand this journey, 304 people with OA and obesity and 101 primary care doctors who treat people with OA and obesity took an online survey.

We found that people with OA and obesity tried to manage their OA symptoms on their own for an average of five years before going to a doctor for help. Many (54%) talked with their primary care doctor first. When people with obesity were told by doctors that they had OA, most people (61%) said that they talked about weight and weight loss. Most people (72%) also talked with their doctors about OA treatments.

Few doctors (12%) thought their patients were serious about losing weight but almost all patients (90%) said they had tried or were still trying to lose weight. About half of doctors followed guidelines for taking care of people with OA (51%) and obesity (61%).

Primary care doctors play a key role in helping patients with OA and obesity. Doctors can follow guidelines and provide treatment options including referrals to other specialists to support weight loss efforts.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

More than 54 million U.S. adults have provider-diagnosed arthritis [Citation1], however, this could be markedly underestimated [Citation2]. Additionally, the prevalence of obesity in patients with arthritis is 38.1%[Citation3]. Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common type of arthritis, currently affecting an estimated 32.5 million adults [Citation4], and is expected to increase to 78 million by 2040 [Citation5]. Obesity is a risk factor for OA development and progression [Citation6,Citation7]. The benefits of weight loss among patients with OA include symptom relief, as well as improved function and quality of life. Strategies for weight loss in patients with OA and obesity include dietary interventions, exercise, medications, and bariatric surgery [Citation8–10].

Several organizations offer clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of OA [Citation11–16] with treatment recommendations pertaining to core non-pharmacological interventions such as patient education, exercise, and weight loss for patients with overweight or obesity, as well as pharmacological and surgical treatment for OA. Most OA guidelines include recommendations related to weight management for patients with OA and obesity [Citation17,Citation18], but provide clinicians little guidance on how to implement those recommendations in clinical practice and how to achieve and maintain weight loss. In general, OA guidelines lack a comprehensive approach to weight loss: 1) specific recommendations for obesity treatment options (e.g. lifestyle, behavioral, pharmacological, surgical), 2) referral to specialists and allied health professionals for obesity treatment, and 3) treatment targets including absolute and percent of total body weight loss, BMI, percent body fat, waist circumference, and other response variables that demonstrate effective obesity treatment. Despite this, from 2002 to 2014, healthcare provider counseling for weight loss increased from 35% to 45% [Citation19] and counseling for exercise increased from 52% to 60% [Citation20] among U.S. adults with OA and overweight/obesity.

There is little in the literature regarding the medical journey of patients with OA and obesity, and the perceptions of healthcare providers and patients regarding treatment for obesity as an approach to treating their OA. To better address the specific needs of patients with OA and obesity, this study sought a comprehensive understanding of the OA patient medical journey by mapping the various touch points and documenting the health care provider roles, influential factors, and how treatment decisions are made. To gain a comprehensive view from a range of healthcare providers, the study was conducted with primary care physicians (PCPs), orthopedic specialists, and rheumatologists. The primary focus of this paper is to define the role of the PCP in the OA patient journey, assess how obesity is addressed in the management of OA, and identify opportunities to improve treatment and outcomes for patients with OA and obesity.

Methods

Study design and participants

A cross-sectional study consisting of an anonymous national online survey was conducted between January 2nd and January 23rd, 2020 among patients with OA and obesity and among healthcare providers treating patients with OA. A total of 309 healthcare providers participated in the study. The focus of this paper is reporting results for the PCP segment of these healthcare providers which included 101 PCPs self-identified as family medicine, internal medicine, or general practice. All respondents were recruited via e-mail from online panel companies to which respondents had provided permission to be contacted for research purposes.

Patient respondents qualified for the survey if they met the inclusion criteria of U.S. residency; age 18–75; self-reported diagnosis by a healthcare provider of OA of the knee, hip, or lumbar/spine; currently seeing a healthcare provider to treat/manage their OA; currently managing their OA with lifestyle changes, over-the-counter therapies, prescription medication, or previous joint replacement surgery; experiences joint pain and discomfort at least occasionally; and has a BMI of ≥30 kg/m2 based on self-reported height and weight. Self-reported pain was defined as follows: 1) mild OA = occasional pain after a long day of walking or running, greater stiffness in the joint(s) when it’s not used for several hours, or tenderness when using the joint(s) at full extension. 2) moderate OA = frequent pain when walking, running, bending, or kneeling, joint stiffness after sitting for long periods of time or when waking up in the morning, and sometimes have joint swelling after extended periods of activity. 3) severe OA = severe and frequent pain doing everyday tasks such as walking or descending stairs, and frequent stiffness after sitting or when waking up in the morning, frequent swelling after any activity. PCPs were eligible to participate if they were: employed in the U.S. (except Maine and Vermont to comply with Sunshine reporting requirements); board certified or eligible; in practice at least two years; based in a hospital or office setting; and treating at least 40 patients in the past month with OA and obesity.

The surveys were developed based on extensive literature review and qualitative interviews with patients with OA and obesity and healthcare providers who treat OA to identify areas requiring further exploration and quantification. Separate surveys were used for each audience to measure attitudes and experiences with OA, the OA diagnosis process, OA management/treatment, attitudes toward obesity and its management, and patient-provider discussions about OA and obesity. The surveys consisted of a variety of binary, multiple-choice, and Likert-scale questions. The study samples were independent, i.e. patients and PCPs surveyed were not matched pairs. See Appendices 1 and 2 for the surveys.

The surveys were online and anonymous; thus, institutional review board approval was not sought. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles and guidelines established by the Office for Human Research Protections and the Insights Association Code of Standards and Ethics. Respondents provided consent to participate in the survey prior to entering the screening portion of the survey. Respondents could discontinue the survey at any time.

Statistical analyses

We performed descriptive statistical analysis (means, frequencies) using SPSS Statistics for Windows 23 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois). Tests of differences (chi-square, t-tests) within respondent types were performed using SPSS tables; additional analyses were performed using Stata/IC 14.1. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, using 2-tailed tests. Data are presented as number and percentage for categorical variables, and continuous data expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise specified. Patients’ BMI was calculated based on self-reported height and weight and categorized into obesity classes defined as Class I: BMI of 30 – <35, Class II: BMI of 35 – <40 kg/m2, and Class III: BMI ≥40.

Role of the funding source

This study was funded by Novo Nordisk, Inc. employees of which co-designed the study (SM) and had a role in the analysis and interpretation of the data (SM and KE).

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 304 patients with OA and obesity participated in the survey (). The majority of respondents were female and had moderate OA severity defined as self-reported frequent joint pain. One-third of patients reported severe and frequent pain (severe OA), and a small percentage (11%) had occasional pain (mild OA). Twenty-one percent of patients reported prior joint replacement surgery. The mean BMI for patients was 39.9 kg/m2. The most common self-reported HCP-diagnosed comorbidities were hypertension (63%), depression (52%), anxiety (42%), sleep apnea (34%), and type 2 diabetes (33%). Additionally, 309 healthcare providers took the survey (), 33% of which were PCPs. The PCP segment is described in .

Table 1. Characteristics of the study sample

Table 2. Characteristics of the primary care physician sample

Pre-OA diagnosis of patients with OA and obesity

Patients self-managed their OA for an average of 5.5 years prior to seeking care from a healthcare provider. Most patients with OA and obesity attributed their OA to aging (78%) or being overweight (73%). Patients with Class III obesity were significantly more likely than those in Obesity Class I or II to believe their OA was caused by excess weight (87% vs. 60% and 69%, respectively). Prior to seeking care, most patients self-managed with over the counter (OTC) oral pain relievers (89%) or analgesic patches or gels (52%). Many patients, particularly those with moderate (42%) and severe (57%) OA also reduced physical activity. Most patients with OA and obesity were first motivated to speak with a healthcare provider because of worsening symptoms (82%). The most common reasons for not discussing OA symptoms sooner was a lack of limitation on daily functioning (42%), a belief that their symptoms were a normal part of aging (41%), and the ability to manage symptoms on their own (38%).

OA diagnosis of patients with OA and obesity

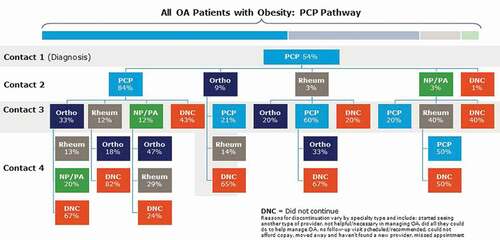

Patients’ journey from first experiencing OA symptoms to seeking care and receiving treatment for their condition varied greatly across the patients surveyed. Patients with OA and obesity were most commonly diagnosed with OA by a PCP (54%) and most (79%) continued to see a PCP for their OA. After being diagnosed by a PCP, a small proportion of patients next saw an orthopedist (9%) or a rheumatologist (3%) (). Many patients also reported seeing ancillary healthcare providers for their OA care, including physical therapists (45%), chiropractors (24%), and pain management specialists (31%). Few patients diagnosed by a PCP have seen a nutritionist (9%), registered dietitian (7%), or a weight loss/obesity medicine specialist (1%).

Characteristics of patients diagnosed by a PCP (n = 164) are described in . Upon a diagnosis of OA, PCPs reported discussing OA treatments (96%), how patients’ weight impacts their OA (89%), causes of OA (83%), progression of OA (70%), and how OA is related to or impacts other health conditions (66%). Although the majority of patients (72%) diagnosed by a PCP recalled discussing treatments for OA, they were much less likely to report other topics being part of the OA diagnosis conversation; only 45% reported their PCP talking about OA causes (45%) or progression (42%), and how OA is related to or impacts other health conditions (32%). However, 61% of patients did recall their PCP discussing their weight or weight management when first diagnosed with OA; the most common topics were the effect of weight on their overall health (76%), effect of weight on their OA (74%), exercise (66%), and diet (59%). Few (13%) reported discussing anti-obesity (weight loss) medications. Most PCPs (70%) provided resources about OA management to their patients at diagnosis, with a pamphlet or website being the most common; however, almost half of patients (48%) indicated their PCP did not provide them with any resources.

Table 3. Characteristics of patients with OA and obesity diagnosed by or managed by a PCP

OA management of patients with OA and obesity

A total of 229 patients surveyed reported seeing a PCP (family medicine, internal medicine, or general practice provider) at some point for the treatment and management of their OA () and are the focus for the remainder of this paper. PCPs and patients were aligned in viewing PCPs as the care coordinator of patients who have OA and obesity (83% and 80%, respectively). Half of patients with OA and obesity (52%) were extremely satisfied (rating of 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale) with their PCP’s approach to the treatment and management of their OA. Most patients reported that their PCP’s approach was helpful (62%) and informative (51%), but only 29% felt it was motivating.

Half of PCPs (49%) reported not following any specific OA clinical treatment guidelines (). Almost all PCPs recommended OTC pain relievers (94%) and lifestyle changes (nutrition and physical activity, 94%) to their patients with OA and obesity; prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were widely provided (87%). Patient-reported treatments align with those reported by PCPs, with OTC pain relievers (65%), lifestyle changes (62%) and prescription NSAIDs (50%) as the most common treatments.

Obesity experiences and perceptions

Although most patients in the study described themselves as having overweight or obesity, only 25% of patients with Obesity Class I and 53% of patients with Obesity Class II described themselves as having obesity. Very few patients with OA and obesity were very comfortable with their current weight (10%) and most (90%) had made at least one serious weight loss effort in their adult life, with an average of 8 attempts. Almost all patients (89%) reported currently trying to lose weight, primarily through traditional diet (80%) and exercise (57%). Overall, three-quarters (78%) of patients were at least somewhat interested in prescription weight loss medication usage and 44% were highly interested, particularly those with severe OA (59%). The majority of patients (71%) and PCPs (57%) felt they have a responsibility to actively contribute to their/their patients’ weight loss efforts. However, only 38% of patients and 12% of PCPs completely agreed they/their patients are motivated to lose weight, and only 24% of patients agreed they know how to maintain long term weight loss.

Obesity treatment and management

If using guidelines for treatment, PCPs most commonly follow national clinical practice guidelines (47%) for the treatment and management of obesity, but many (39%) reported not following any guidelines (). Of the PCPs using obesity management guidelines, few (15%) think they are very or extremely effective. PCPs reported recording the BMI of their patients with OA and obesity at almost all appointments (91%), but documented a diagnosis of obesity in the patient’s medical record in fewer visits (71%) and informed patients of their BMI in only 66% of appointments.

Almost three-quarters (72%) of PCPs reported discussing weight management with their patients who have OA and obesity at every visit or almost every visit; 56% of patients report these conversations occurring this frequently. Of the healthcare providers with whom patients have discussed weight/obesity management, PCPs are considered by patients to be the most helpful (75%) as compared to specialists or ancillary health professionals (range: 2%-6%).

When talking about weight or weight management with their patients who have OA and obesity, PCPs were much more likely than patients to report discussing the effect patients’ weight has on their OA and overall health, helping patients set goals to improve their weight and understand why they have excess weight, and making patients aware of medications that will help them lose weight (). Patients reported that diet and exercise were also commonly discussed (). Patients were less likely than PCPs to feel their weight has much of an impact on 1) when OA develops (35% vs. 63%), 2) how quickly OA progresses (43% vs. 66%), and 3) how severe OA becomes (55% vs. 74%).

Figure 3. Topics discussed during conversations about weight/weight management between PCPs and patients with OA and obesity

PCPs reported prescribing anti-obesity medications to an average of 21% of their patients with OA and obesity. More than half of PCPs utilize technology to help manage their patients with OA and obesity including online patient portals (54%), activity tracking apps or devices (67%), and food tracking apps or devices (68%). On average, PCPs reported referring a small proportion of their patients with OA and obesity to bariatric surgeons (10%), obesity medicine specialists (11%), registered dietitians (17%), or nutritionists (25%). Patients were typically referred when significant weight loss is required to have joint replacement surgery. These treatment referrals were to bariatric surgeons (73%), obesity medicine specialists (63%), dietitians (80%), and nutritionists(74%). Lack of patient motivation and compliance was ranked by PCPs as the greatest barrier to the treatment and management of obesity in their patients with OA; only one-quarter ranked lack of time during patient visits as the top barrier.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that PCPs are the main contact for patients with OA and obesity at diagnosis and throughout their OA journey. PCPs are the care coordinator, are engaged in weight management/obesity treatment discussions, feel responsible to advise and assist patients on weight loss, and use resources to help manage their patients with OA and obesity. PCPs and patients generally recognize the connection between OA and obesity; PCPs inform patients of the impact of their weight/obesity on OA at diagnosis and at follow-up visits. Although many patients report their weight as a main cause of their OA, this perception was less common among those with Class I and II obesity. Patients acknowledge lack of motivation to lose weight, potentially due to previous and current challenges with maintaining weight loss, lack of effective resources from their PCP, and multiple past attempts to lose weight. PCPs believe lack of patient compliance and motivation are barriers to patients losing weight; however, many physicians do not inform patients of their BMI.

Clinical practice guidelines can be valuable resources for physicians in their management of OA and obesity. However, our study found that clinical guidelines for the treatment of OA are followed by only half of PCPs. Obesity guideline use is slightly higher, but generally considered to be ineffective. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) [Citation15] strongly recommends that all patients with symptomatic knee or hip OA who are overweight be counseled regarding weight loss. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) identifies obesity as a risk factor for total hip arthroplasty adverse outcomes [Citation12] and suggests weight loss for patients with symptomatic knee OA and a BMI ≥25 kg/m2 [Citation11]. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) offers a core recommendation of weight management for knee OA and includes a good clinical practice statement suggesting weight management for patients with hip OA [Citation13]. Some regional and international clinical guidelines provide more specific information such as addressing obesity using a multi-faceted individualized treatment plan, including education and counseling regarding weight reduction [Citation16] and weight loss targeted to at least 10% of body weight to achieve significant symptom benefit [Citation14].

PCPs treating patients with OA and obesity could benefit from using clinical guidelines focused specifically on the management of obesity [Citation21,Citation22] which provide strategies including screening for BMI, communication of the benefits of sustained weight loss of 5%-10%, dietary therapy based on patients’ preferences and as appropriate for their health conditions, provision of behavioral counseling and utilization of anti-obesity medications and/or bariatric surgery. A notable challenge for PCPs is the limited focus on OA within their practice as well as time limitations in engaging in long-term support needed for weight loss and weight loss maintenance, but the latter was not cited as a main barrier by the PCPs we surveyed. Crucially, individuals receiving obesity management counseling are more likely to try to lose weight [Citation23] and are four times more likely to be successful at losing weight than those who do not receive counseling [Citation24].

Following the 5 A’s Behavior Change Model (Ask, Assess, Advise, Agree, and Assist) can be a valuable approach for PCPs as they support patients with OA and obesity in their weight management efforts [Citation25], as it has been shown that all aspects of this approach are critical for success [Citation26]. The PCPs surveyed in our study understood the importance of treating obesity and were eager to help their patients. There are several strategies PCPs can leverage that could have substantial positive impacts on the outcomes of patients with OA and obesity including 1) more regular assessment and communication of obesity, 2) advising on the importance of a long-term strategy and available treatment options including and beyond lifestyle intervention, 3) agreement on weight loss goals and obesity treatment plans, 4) assisting in overcoming barriers by providing effective resources based on patients’ needs and learning styles, and 5) early referrals to additional beneficial healthcare providers. Previous research has demonstrated that not all patients with obesity are embarrassed [Citation27] or uncomfortable talking about their weight with their HCP [Citation28]. Additionally, there is interest in anti-obesity medications among the patients we surveyed, yet PCPs prescribe these obesity treatments infrequently. Referrals to obesity medicine specialists, bariatric surgeons, exercise specialists, and dietitians are typically to lower weight in preparation for joint replacement surgery, rather than earlier in the patient journey where there is greater potential for reduction of disease progression.

Although the objective for weight-reduction counseling has not been retained in Healthy People 203029, we strongly encourage physicians to provide or refer patients for counseling as outlined in the clinical guidelines to help patients successfully manage and treat OA and obesity. Progress had previously been made regarding the Healthy People 2020 objectives as of 2014, meeting the goal for the proportion of adults with OA and overweight or obesity who receive weight-reduction counseling, and exceeding the target for receiving physical activity or exercise counseling [Citation29]. Additional training and support for PCPs can help effectively advance the management of OA and obesity to meet the new 2030 targets for exercise counseling [Citation30], ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Limitations

The cross-sectional design and self-reported nature of height and weight are potential limitations; however, there is evidence that BMI is often underestimated based on self-report [Citation31]. Patients and physicians belonging to an online panel may differ from those who are not panel members including gender, ethnicity, and age. Furthermore, responders may have different demographic characteristics than non-responders, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the entire population of patients with OA and obesity. Although responder bias could exist, this was mitigated by not revealing the topic of the survey to respondents until they met all the required screening criteria. It is possible that patients with OA and obesity currently seeing a healthcare provider may differ from those not under the care of a physician or advanced practitioner. As the patient and PCP respondents were sampled independently and thus not matched, differences in perceptions and experiences of the two groups could be related to differences in the patients with OA and obesity and patients with OA and obesity managed by the PCPs. Differences could also be attributed screening criteria for inclusion, PCPs had to identify their practice as meeting a volume level of patients with OA to demonstrate experience with OA; the PCPs treating the patients in the study may not all meet the same level of experience in treating OA.

Conclusions

PCPs are uniquely positioned to support patients with OA and obesity. Following current OA and obesity guidelines can assist these physicians and advanced practitioners in using a multifaceted approach for the management of obesity including lifestyle therapy, specialist referrals, counseling, anti-obesity medications, and bariatric surgery. Using the 5 A’s of Obesity Management as a framework for behavior change with particular focus on ‘Assisting’ as an approach, PCPs can help patients manage their obesity which in turn will improve patients’ OA symptoms and quality of life.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

DBH is a consultant for Currax, Gelesis, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk.

CD has collaborated in research with Breg, Inc. His spouse is an employee of Pfizer and has accepted personal consultancy and speaker fees from the following companies: Allergan, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Teva.

AN has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly.

KE is an employee of Novo Nordisk and owns stock in Novo Nordisk.

SM is an employee of Novo Nordisk and owns stock in Novo Nordisk

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (508.7 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Rebecca Hahn and Elizabeth Tanner of KJT Group, Inc. for medical writing and editing assistance and support (funding provided by Novo Nordisk) and the Osteoarthritis Medical Interface Mapping Study Group: Abhilasha Ramasamy, B. Gabriel Smolarz, Carol Hamersky, Cate Nojiri, Nathan Howard, Kaushal Mehta, Laura Hamway, Todd Paulsen, and Travis Fisher.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barbour KE, Helmick CG, Boring M, et al. Vital signs: prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation — United States, 2013–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(9):246–253.

- Jafarzadeh SR, Felson DT. Updated estimates suggest a much higher prevalence of arthritis in United States adults than previous ones. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(2):185–192. [published Online First: 2017/11/28].

- Barbour KE, Helmick CG, Boring M, et al. Obesity trends among US adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis 2009–2014. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69(3):376–383.

- United States Bone and Joint Initiative: The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States (BMUS), Fourth Edition, 2020. Rosemont, IL. Available at http://www.boneandjointburden.org. Accessed on September 23, 2021.

- Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Barbour KE, et al. Updated projected prevalence of self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation among US adults, 2015-2040. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(7):1582–1587. [published Online First: 2016/03/26].

- Vina ER, Kwoh CK. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: literature update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30(2):160–167. [published Online First: 2017/12/12].

- Thijssen E, van Caam A, van der Kraan PM. Obesity and osteoarthritis, more than just wear and tear: pivotal roles for inflamed adipose tissue and dyslipidaemia in obesity-induced osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2014;54(4):588–600.

- Dadabo J, Fram J, Jayabalan P. Noninterventional therapies for the management of knee osteoarthritis. J Knee Surg. 2019;32(1):46–54.

- Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1745–1759. [published Online First: 2019/04/30].

- Martel-Pelletier J, Barr AJ, Cicuttini FM, et al. Osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2(1). DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.72

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Management of Osteoarthritis of the Knee (Non-Arthroplasty) Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. https://www.aaos.org/oak3cpg Published August 31, 2021

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hip Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/quality-and-practiceresources/osteoarthritis-of-the-hip/oa-hip-cpg_6-11-19.pdf Published March 13, 2017.

- Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(11):1578–1589.

- Bruyère O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP, et al. An algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis in Europe and internationally: a report from a task force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(3):253–263.

- Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. 2019 American college of rheumatology/arthritis foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(2):220–233. [published Online First: 2020/01/08].

- Michigan Quality Improvement Consortium Guideline. Medical management of adults with osteoarthritis. 2017

- Brosseau L, Rahman P, Toupin-April K, et al. A systematic critical appraisal for non-pharmacological management of osteoarthritis using the appraisal of guidelines research and evaluation II instrument. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1). DOI:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082986

- Ferreira de Meneses S, Rannou F, Hunter DJ. Osteoarthritis guidelines: barriers to implementation and solutions. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59(3):170–173.

- Guglielmo D, Hootman JM, Murphy LB, et al. Health care provider counseling for weight loss among adults with arthritis and overweight or obesity — United States, 2002–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(17):485–490.

- Hootman JM, Murphy LB, Omura JD, et al. Health care provider counseling for physical activity or exercise among adults with arthritis — United States, 2002 and 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;66(5152):1398–1401.

- Bays HES, Primack C J, Long J, et al. Obesity algorithm, presented by the obesity medicine association. 2017-2018 Available from: www.obesityalgorithm.org cited 2020 Nov 11.

- Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists and american college of endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(Suppl 3):1–203. [published Online First: 2016/05/25].

- Mehrotra C, Naimi TS, Serdula M, et al. Arthritis, body mass index, and professional advice to lose weight: implications for clinical medicine and public health. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(1):16–21.

- Rose SA, Poynter PS, Anderson JW, et al. Physician weight loss advice and patient weight loss behavior change: a literature review and meta-analysis of survey data. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(1):118–128. [published Online First: 2012/03/28].

- Vallis M, Piccinini-Vallis H, Sharma AM, et al. Clinical review: modified 5 As: minimal intervention for obesity counseling in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(1):27–31. [published Online First: 2013/01/24].

- Alexander SC, Cox ME, Boling Turer CL, et al. Do the five A’s work when physicians counsel about weight loss? Fam Med. 2011;43(3):179–184. [published Online First: 2011/03/08].

- Kaplan LM, Golden A, Jinnett K, et al. Perceptions of barriers to effective obesity care: results from the national ACTION study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26(1):61–69.

- Look M, Kolotkin RL, Dhurandhar NV, et al. Implications of differing attitudes and experiences between providers and persons with obesity: results of the national ACTION study. Postgrad Med. 2019;131(5):357–365. [published Online First: 2019/06/04].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy people 2030. How has healthy people changed? Available from: https://health.gov/healthypeople/about/how-has-healthy-people-changed cited 2020 Nov 11.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Chapter 3: Arthritis, Osteoporosis, and Chronic Back Conditions. Healthy People 2020 Midcourse Review. Hyattsville, MD. 2016

- Shiely F, Hayes K, Perry IJ, et al. Height and weight bias: the influence of time. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54386. [published Online First: 2013/02/02].