ABSTRACT

Objectives

Patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) report dissatisfaction with the diagnostic process and are more likely to have overweight or obesity. We wanted to understand the role that primary care physicians (PCPs) play in the diagnosis of PCOS and how they contribute to treatment of patients with PCOS and obesity.

Methods

A cross-sectional online survey was completed by 251 patients with PCOS and obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and 305 healthcare providers (PCPs, obstetricians/gynecologists, reproductive and general endocrinologists). This paper focuses on the 75 PCPs treating patients with PCOS and obesity.

Results

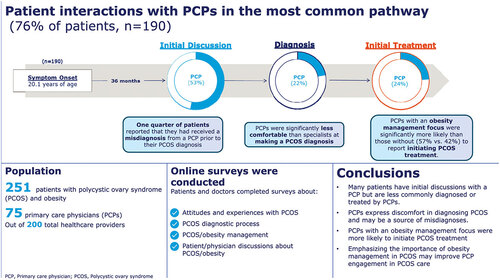

In the most common patient journey, we found that most patients with PCOS and obesity (53%) have initial discussions about PCOS symptoms with PCPs. However, less than one quarter of patients receive a PCOS diagnosis (22%) or initial treatment (24%) for PCOS from a PCP. One quarter of patients also reported receiving a misdiagnosis from a PCP prior to their PCOS diagnosis. Compared to other healthcare providers surveyed, PCPs were the least comfortable making a PCOS diagnosis. Compared to PCPs without an obesity management focus, PCPs with an obesity management focus were more likely to diagnose patients themselves (38% vs 62%) and initiate PCOS treatment themselves (42% vs 57%). According to PCPs, difficulty with obesity management (47%) was the top reason that patients with PCOS and obesity stop seeing them for PCOS management.

Conclusion

PCPs are often the initial medical touchpoint for patients with PCOS and obesity. However, PCPs play a smaller role in diagnosis and treatment of PCOS. Increasing education on obesity management may encourage PCPs to diagnose and treat more patients with PCOS and offer strategies to help patients with obesity management.

Plain Language Summary

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a condition where women may make more male hormones than usual, have irregular periods, and have trouble getting pregnant. PCOS can look very different in different patients. This can make it difficult to diagnose. Patients with PCOS are more likely to have obesity (unhealthy excess weight). Having obesity can make patients’ PCOS worse and losing weight is an important treatment for PCOS.

We wanted to learn more about what patients with PCOS and obesity experience as they try to manage their PCOS and the role of primary care doctors in diagnosing and treating patients with PCOS. To better understand this journey, 251 patients with PCOS and obesity and 75 primary care doctors who treat patients with PCOS and obesity took an online survey.

Most patients (53%) first talked about PCOS symptoms with a primary care doctor. However, less than 25% of patients received a PCOS diagnosis or first treatment from a primary care doctor. One quarter of all patients said they were misdiagnosed by a primary care doctor before being diagnosed with PCOS. Primary care doctors were less comfortable than specialist doctors in diagnosing and treating patients with PCOS. Primary care doctors with a focus on weight management were more likely than other primary care doctors to diagnose and treat patients with PCOS themselves.

Giving primary care doctors more educational support with PCOS diagnosis and weight management could help patients with PCOS get diagnosed earlier and treated better.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine disorder affecting between 5% and 20% of reproductive aged women [Citation1] and is the most common endocrine disorder affecting women of this demographic. PCOS is often characterized by acne, hirsutism, infertility, and menstrual dysfunction [Citation2]. However, PCOS is a heterogenous disorder in both phenotype and in severity of metabolic consequences [Citation2]. Employing the most widely used diagnostic criteria, the Rotterdam criteria, a patient can be diagnosed with PCOS if they have two out of three of the following conditions: excessive androgen production (hyperandrogenism), ovulatory dysfunction, and polycystic ovarian morphology (excessive preantral follicles in the ovaries) [Citation3].

1.2 Burden of PCOS

PCOS represents a major burden to our society from both economic and health perspectives. For example, patients with PCOS are hospitalized more than twice as often as patients without PCOS during early adulthood [Citation4] and United States (US) medical expenditures associated with PCOS were between $1.6 and $4.4 billion annually between 2005 and 2010 [Citation5,Citation6]. Patients with PCOS are significantly more likely to experience pregnancy complications, such as pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes, than patients without PCOS [Citation7]. Patients with PCOS are also more likely to experience anxiety and depression [Citation4,Citation8] and have an increased risk of obesity, infertility, type 2 diabetes, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and other cardiometabolic comorbidities [Citation4,Citation9,Citation10] all of which contribute to the economic burden of this disease.

1.3 PCOS and obesity

Patients with PCOS are significantly more likely to have overweight or obesity compared to patients without PCOS [Citation11]. Prevalence of obesity in patients with PCOS is estimated at 49% [Citation11]. Most patients with PCOS experience some degree of hyperandrogenism [Citation12] and insulin resistance [Citation13,Citation14]. Both hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance are thought to drive fat accumulation and contribute to obesity in patients with PCOS.

Hyperandrogenism is suspected to initiate a positive feedback loop where androgen excess leads to increased abdominal adiposity which in turn promotes androgen production [Citation15]. Increased abdominal adiposity portends additional associated risks and is considered the key driver for many components of metabolic syndrome [Citation16], which is a clustering of many conditions, such as insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and central obesity [Citation17].

Insulin resistance leads to compensatory hyperinsulinemia which causes neuroendocrine disruptions in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. It is thought that compensatory hyperinsulinemia and enhanced pituitary sensitivity to gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) leads to overproduction of luteinizing hormone (LH) [Citation18]. Increased LH expression coupled with normal or low follicle stimulating hormone expression leads to overproduction of androgens in the theca cells of the ovaries [Citation19]. The increased production of androgens can, in turn, increase insulin resistance by interfering with insulin signaling and by triggering lipolysis [Citation18]. Therefore, insulin resistance and hyperandrogenemia can act as a complicated positive feedback loop that worsens PCOS and obesity. These metabolic pathways can be influenced by genetic and environmental factors that are highly heterogenous across patients with PCOS and obesity and are areas of active research [Citation18].

1.4 The patient experience

In a global online survey, 34% of patients reported that their PCOS diagnosis was delayed by more than two years, and only 35% were satisfied with their diagnostic experiences [Citation20]. In the same study, only 25% of patients with PCOS reported being satisfied with information provided about lifestyle management and medical therapy [Citation20]. Dissatisfaction with diagnosis, information provided, and standard of PCOS care are common themes in PCOS research [Citation21]. Patients with PCOS are significantly more likely than patients without PCOS to distrust the opinions of primary care physicians (PCPs) [Citation22]. Patients with PCOS were more likely than those without PCOS to believe that PCPs spent less effort and were less qualified to treat PCOS health concerns over general health concerns [Citation22]. Collectively, these data demonstrate a need to better understand the relationship between PCPs and patients with PCOS to improve patient satisfaction and health outcomes.

1.5 Objectives

We aimed to understand the typical medical journey of patients with PCOS and obesity, to understand the role of PCPs in diagnosing and treating patients with PCOS and obesity, and to identify existing gaps in diagnosis and treatment of patients with PCOS and obesity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and ethical approval

A cross-sectional study consisting of an anonymous national online survey was conducted among both healthcare providers treating patients with PCOS and obesity and patients with obesity and a self-reported diagnosis of PCOS. Data were collected from October 30th to December 1st, 2020. All respondents were recruited via e-mail and all respondents had provided permission to be contacted for research purposes. Eligible participants completing the entire survey received a modest monetary incentive. The study protocol was submitted to the Western Institutional Review Board (WIRB) for ethical approval. WIRB is a central institutional review board which was used due to the lack of review boards at the authors’ affiliated institutes. WIRB reviewed the study protocol and determined the study to be exempt from further review because the research includes survey procedures with adequate provisions to protect the privacy of participants and maintain data confidentiality. Respondents were informed of the purpose of the research, consented to the terms, and could withdraw at any point.

2.2 Survey design

Separate surveys were used for patients (Appendix 1) and healthcare providers (Appendix 2) to measure: 1) attitudes and experiences with PCOS prior to diagnosis; 2) experience with the diagnosis process; 3) management and treatment of PCOS; 4) PCOS management guidelines (healthcare providers only); 5) obesity discussions, management, and attitudes; and 6) informational sources for PCOS and obesity. The surveys consisted of a variety of yes/no, multiple-choice, and Likert scale questions on a seven-point scale from one to seven .

2.3 Participants

The study samples were independent, i.e. patients and healthcare providers surveyed were not matched pairs. Patients were included if they were US residents, aged 18–55 years, had a self-reported diagnosis of PCOS, were born female and identify as female, were seeking help with fertility or other PCOS-related issues (e.g. obesity, hirsutism, irregular menses), and had obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2). Healthcare providers included clinicians employed in US facilities (except Maine and Vermont to comply with Sunshine Act reporting requirements), physicians practicing as PCPs (internal medicine, general practice, and family practice), obstetricians/gynecologists (OB/GYNs), general endocrinologists, or reproductive endocrinologists. Clinicians treating at least five patients (PCPs and general endocrinologists) or ten patients (OB/GYNs and reproductive endocrinologists) with PCOS and obesity in the past month and those with board certification or eligibility in their chosen specialty who were in practice for 3–25 years but not working in a government facility or an ambulatory surgical center were included in this study. PCPs were asked if their current practice and caseload focused primarily on the treatment of obesity or excess weight; those responding affirmatively were classified as PCPs with an obesity management focus for downstream data analyses.

2.4 Statistical analyses

We performed descriptive statistical analysis (means, frequencies) using SPSS Statistics for Windows 23 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois). Tests of differences (chi square, t-tests) within respondent types were performed using SPSS. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, using 2-tailed tests. Patients were asked to list the order in which they had discussions about PCOS symptoms, received treatment for PCOS symptoms, and were diagnosed with PCOS. Based on this order patients were grouped into different medical pathways. The most common pathway comprised 76% of patients and included patients who 1) had initial discussions about PCOS symptoms 2) were diagnosed with PCOS and 3) received treatment for PCOS. Some statistical reporting focuses on the subset of patients in the most common pathway.

3. Results

3.1 Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics of patients with PCOS and obesity and healthcare providers surveyed are shown in . All patients included in this study had obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) as calculated from their self-reported height and weight and 74% of patients self-reported obesity as a comorbidity.

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

3.2 Pre-diagnosis symptoms

On average, patients with PCOS and obesity reported that they first experienced symptoms at 20.4 years of age. Prior to discussing PCOS symptoms with a healthcare provider, patients experienced irregular periods (82%), weight gain (73%), painful periods (60%), excessive hair growth (52%), and absence of periods (50%). Patients ultimately discussed their symptoms with a healthcare provider due to symptoms worsening (52%), not resolving (52%), and interfering too much in their daily life (45%). Patients did not discuss symptoms with a healthcare provider sooner because they thought symptoms were due to normal puberty or genetics (43%), did not think there was anything a healthcare provider could do about it (34%), or did not want to admit they were experiencing a health issue (26%).

3.3 Initial discussions

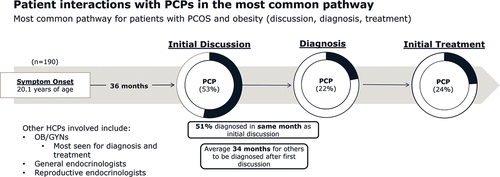

In the most common pathway to diagnosis (comprising 76% of patients), approximately half of all patients (53%) had their initial discussions about PCOS symptoms with a PCP (). Patients who experienced moderate (age 18–30) or late (age ≥31) PCOS onset were more likely to have their initial discussions about PCOS symptoms with an OB/GYN. In the most common pathway, 51% of patients were diagnosed in the same month that they had initial discussions with a healthcare provider. However, the other 49% of patients waited an average of 34 months to be diagnosed after their initial discussions about PCOS symptoms ().

Figure 1. Most common pathway for patients with PCOS and obesity (n = 190 or 76% of patients). The ‘pathway’ relates to patients who had initial discussions with healthcare providers, followed by a PCOS diagnosis, and ultimately treatment for PCOS. Abbreviations: HCP, healthcare provider; OB/GYN, obstetrician/gynecologist; PCP, primary care physician.

3.4 Misdiagnosis

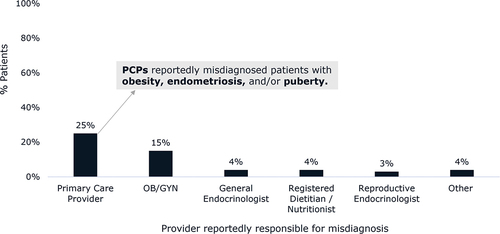

Some patients in our study (33%) reported being misdiagnosed with another condition prior to receiving a formal PCOS diagnosis. Most (25%) recounted receiving a misdiagnosis from a PCP (). PCPs reportedly misdiagnosed these patients with obesity, endometriosis, and/or common manifestations of puberty.

Figure 2. Percentage of all patients (n = 251) with PCOS and obesity reporting that they were misdiagnosed by the indicated type of healthcare providers. Patients could select multiple provider types that reportedly had previously misdiagnosed their PCOS symptoms, and 82 patients reported receiving a misdiagnosis prior to their PCOS diagnosis. Abbreviations: OB/GYN, obstetrician/gynecologist; PCP, primary care physician.

3.5 Diagnosis appointments

In our study, 93% of PCPs reported having diagnosed patients with PCOS. PCPs were asked about which types of appointments they usually discussed PCOS symptoms with patients. PCPs estimated that they discussed PCOS symptoms at appointments made for well-visits or annual exams (36%), at appointments made specifically to address PCOS symptoms (32%), and at appointments to discuss other conditions (27%). Among their patients with PCOS and obesity, PCPs estimated that they personally diagnosed half (51%) of them. PCPs with an obesity management focus (62%) were significantly more likely than those without (38%) to personally diagnose patients with PCOS (p < 0.05).

3.6 Diagnosis topics discussed

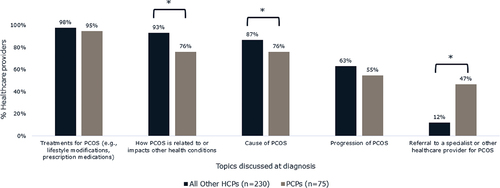

At the time of diagnosis, PCPs (47%) were significantly more likely than all other healthcare providers surveyed (OB/GYNs [9%], reproductive endocrinologists [13%], general endocrinologists [17%]) to discuss referral to a specialist for PCOS treatment (p < 0.05) (). PCPs were the least likely healthcare provider type to discuss how a patient’s PCOS is related to or impacts other health conditions (PCPs [76%], OB/GYNs [94%], reproductive endocrinologists [93%], general endocrinologists [91%]) ().

Figure 3. Topics all other healthcare providers (n = 230) and PCPs (n = 75) discuss with patients with PCOS and obesity at the time of PCOS diagnosis. Other healthcare providers surveyed included OB/GYNs, general endocrinologists, and reproductive endocrinologists. PCPs were significantly more likely than other healthcare providers to discuss referral to a specialist for PCOS treatment (p < 0.05). *Brackets indicate significant difference between groups (p < 0.05). Abbreviations: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; PCP, primary care physician.

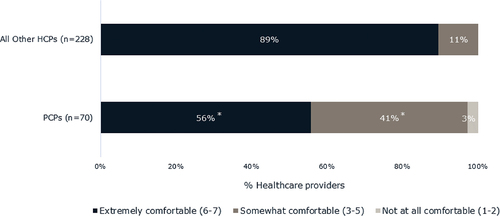

3.7 PCP comfort diagnosing PCOS

Just over half (56%) of PCPs reported feeling extremely comfortable (6–7 on a 7-point Likert scale) making a PCOS diagnosis among patients with PCOS and obesity; notably they were significantly less likely compared to all other healthcare providers (89%) surveyed to report feeling extremely comfortable (p < 0.05). Four in ten (41%) PCPs were somewhat comfortable (3–5 on 7-point Likert scale) diagnosing patients with PCOS and 3% were not at all comfortable making a PCOS diagnosis (1–2 on 7-point Likert scale) ().

Figure 4. Levels of comfort of all other healthcare providers and of PCPs in making a PCOS diagnosis. Question was asked of HCPs who diagnose some patients with PCOS and obesity. Significantly fewer PCPs felt extremely comfortable making a PCOS diagnosis relative to other healthcare providers. Other healthcare providers surveyed included OB/GYNs, general endocrinologists, and reproductive endocrinologists. *Indicates that the means for PCPs differ significantly from the means of all other healthcare providers surveyed (p < 0.05). Other healthcare providers included OB/GYNs, general endocrinologists, and reproductive endocrinologists. Abbreviations: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; PCP, primary care physician.

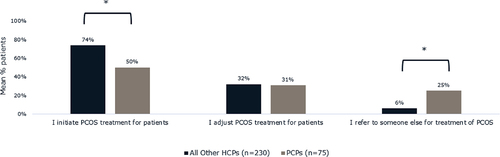

3.8 Provision of treatment

PCPs (50%) were significantly less likely compared to all other healthcare providers (74%) to initiate PCOS treatment for patients with PCOS and obesity (p < 0.05). On average, PCPs estimated that they initiated PCOS treatment for 50% of their patients with PCOS and obesity (). PCPs with a focus on obesity management (57%) estimated that they initiated treatment for significantly more patients than PCPs without an obesity management focus (42%) to initiate PCOS treatment (p < 0.05). Approximately four in ten (39%) PCPs said that other providers do not typically refer patients with PCOS to them for treatment. When other providers did refer patients with PCOS and obesity to PCPs for PCOS treatment, the most common reason given by other providers was for treatment of comorbidities (69%). Only 19% of patients considered PCPs to be the coordinator of their PCOS care and 18% did not consider any healthcare provider to be the coordinator of their PCOS care. Over half of patients (51%) considered OB/GYNs to be the coordinator of their PCOS care.

Figure 5. Roles of all other healthcare providers and of PCPs in treating patients with PCOS and obesity. Healthcare providers were asked to estimate the proportion of patients living with PCOS and obesity for whom they initiate treatment, adjust treatment, or refer to someone else for treatment of PCOS. *Brackets indicate a significant difference in the estimates of PCPs compared to all other healthcare providers surveyed (p < 0.05). Abbreviations: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; PCP, primary care physician.

3.9 Treatment approaches

Most (77%) PCPs indicated that they follow clinical practice guidelines for the management of PCOS. The guideline most frequently followed by PCPs (58%) was that of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). For ongoing management of PCOS symptoms in patients with obesity, PCPs reported they typically prescribe metformin (92%), lifestyle change (81%), oral contraceptives (78%), spironolactone (77%), specific diets (62%), anti-obesity medications (55%), medroxyprogesterone (28%), and/or letrozole (31%). Patients were asked which treatments they had ever been prescribed and used for ongoing treatment of PCOS. Patients had previously used or were currently using lifestyle changes (84%), oral contraceptives (84%), over-the-counter treatments for menstrual pain, acne or excessive hair growth (79%), metformin (59%), and over-the-counter weight loss treatments (52%).

3.10 Obesity management

PCPs were more likely than patients to understand the impact of obesity on the development, progression, and severity of PCOS. Almost all PCPs (88%) believed PCOS placed patients at increased risk of cardiometabolic conditions. Among patients who recalled discussions of obesity at diagnosis and were diagnosed by PCPs, about half said that PCPs explained the effect obesity has on their PCOS (54%) and/or the effect PCOS has on obesity (51%). Fewer patients said that PCPs told them about ways to lose weight (31%), helped set weight loss goals (31%), or told them about anti-obesity medications (17%). PCPs were more likely to suggest that these patients see a dietitian or nutritionist (43%). PCPs with a focus on obesity management were significantly more likely to address obesity at every visit compared to those without an obesity management focus (48% vs 24%, respectively) (p < 0.05). Most patients who had seen a PCP for ongoing management of PCOS and obesity said that PCPs discussed their weight at every appointment (34%), at most appointments (26%), or at some appointments (16%). Almost one in four (24%) said that PCPs rarely or never discussed their weight at appointments.

PCPs were asked to estimate the proportion of patients for which they recommend certain obesity management regimens. Compared to PCPs without an obesity management focus, PCPs with an obesity management focus estimated that they recommend a significantly greater proportion of patients try medical weight loss programs (15% vs 29%) or anti-obesity medication (15% vs 31%) (p < 0.05). Most PCPs said difficulty with obesity management (47%), lack of treatment efficacy (41%), and change in insurance coverage (35%) were among the top three reasons patients with PCOS and obesity stop seeing them for PCOS management. Among patients who had seen multiple providers who discussed obesity management, 23% said PCPs had been the most helpful while 30% said no providers had been helpful in supporting their obesity management efforts.

4. Discussion

4.1 Summary of key findings

Our study showed that approximately half of patients with PCOS and obesity have their initial discussion of PCOS symptoms with a PCP. According to patients, PCPs were the healthcare provider most frequently involved in PCOS misdiagnoses. PCPs reported being the least comfortable in making PCOS diagnoses among all healthcare professionals surveyed. PCPs were less involved in the treatment of patients with PCOS and obesity as compared to other HCPs, particularly OB/GYNs. PCPs with an obesity management focus were more likely to initiate treatment for patients with PCOS and obesity; they were also more likely to refer patients to a weight loss program and prescribe anti-obesity medications. This suggests that improving PCP education around obesity management may encourage PCPs to engage more in treatment of their patients with PCOS and obesity.

4.2 PCPs are often the first medical touchpoint for patients with PCOS and obesity

If PCPs do not recognize PCOS in adolescence, it can go undetected well into adulthood with repercussions for patient health. In the most common patient journey, most patients had their initial discussions about PCOS symptoms with a PCP. However, patients with moderate and late onset PCOS were more likely to have their initial discussions with an OB/GYN. This suggests that previously undetected PCOS is uncovered by OB/GYNs in adulthood. PCOS can be difficult to identify in adolescence due to the phenotypic similarities of normal pubertal development and symptoms of PCOS [Citation23]. In addition, hormonal birth control can mask symptoms of PCOS by treating symptoms of hyperandrogenism [Citation24]. Patients may not receive a PCOS diagnosis until discontinuing birth control.

4.3 PCPs may delay proper diagnosis for patients with PCOS and obesity

In our study, PCPs reported low confidence in diagnosing PCOS. Less than one quarter of patients were diagnosed by a PCP; most were diagnosed by OB/GYNs which mirrors findings from a similar study [Citation21]. Patients reported that PCPs were the most likely healthcare providers to misdiagnose them with a condition other than PCOS, which is an important finding as misdiagnoses and lack of referral could lead to delays in proper diagnosis for patients with PCOS and obesity. The latter was captured in our study as we found that in the most common pathway, half of patients were diagnosed in the same month that they had their initial discussion of symptoms with a PCP. However, the other half of patients waited an average of 34 months for a proper diagnosis. A similar study in Canada found that 34% of patients waited more than 2 years for a PCOS diagnosis and 41% saw three or more doctors before receiving their diagnosis [Citation25]. A survey of patients with PCOS found that seeing ≥5 health professionals and >2 years’ time to diagnosis were both negatively associated with diagnosis satisfaction [Citation20]. Therefore, healthcare professionals should aim to improve the time to diagnosis for patients with PCOS.

4.4 PCP role in treatment of patients with PCOS

In our study, PCPs played a small role in primary treatment of PCOS. In the most common patient journey, most patients with PCOS and obesity were treated by OB/GYNs. PCPs were most likely to refer patients with PCOS and obesity to other providers for treatment. PCPs reported a lack of confidence in treatment options and motivation of patients to lose weight. These results suggest that PCPs feel ill-equipped to treat PCOS and other studies confirm that patients feel dissatisfied with guidance provided by physicians [Citation26]. ACOG clinical practice guidelines recommend lifestyle modifications as the best approach to reducing risks for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes in patients with PCOS [Citation27]. ACOG also recommends the use of insulin-sensitizing drugs and statins where appropriate [Citation27]. The ACOG clinical practice guidelines stress the importance of treating symptoms and comorbidities in patients with PCOS. PCPs can administer such treatments, and most report following ACOG guidelines for the treatment of PCOS. Few PCPs reported following no guidelines for the management of PCOS. Thus, it is surprising that the PCPs surveyed did not feel more confident in treating patients with PCOS and obesity. PCPs may feel that patients would be better managed by OB/GYNs or endocrinologists for PCOS treatment.

4.5 PCOS and obesity

As front-line care providers, PCPs may ultimately improve patient outcomes by diagnosing and intervening earlier in PCOS and obesity treatment as PCOS and obesity are drivers of related metabolic comorbidities. Patients with PCOS often have obesity and other features of metabolic syndrome, such as insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia [Citation10,Citation28]. Abdominal adiposity is the key driver in most pathways of metabolic syndrome [Citation16]. Lifestyle modification to reduce visceral adiposity is seen as the primary mechanism to treat metabolic syndrome [Citation16]. NAFLD is another adiposity-based chronic disease associated with metabolic syndrome [Citation29]. PCOS and obesity are both independently associated with an increased risk of NAFLD [Citation30]. Like PCOS, NAFLD is associated with poor cardiometabolic outcomes later in life which highlight the importance of early diagnosis and intervention [Citation31].

4.6 PCPs and obesity management

PCPs reported a strong understanding of the effect that obesity has on PCOS and the effect of PCOS on cardiometabolic health. Few patients said that PCPs told them about ways to lose weight, helped them set weight loss goals, or told them about anti-obesity medications; similar findings were seen in a qualitative study from India where only 9% of patients received information about PCOS from their doctors [Citation32]. It is surprising that theuse of anti-obesity medications was low in our study given the body of research demonstrating their efficacy in many patients [Citation33,Citation34]. Research has shown that patients with PCOS can benefit from weight loss, oral contraceptives, antiandrogens, insulin sensitizers, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), and behavioral interventions [Citation34]. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and American College of Endocrinology (ACE) guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity recommend that concurrent initiation of pharmacotherapy and lifestyle change be considered in patients with weight-related complications that can be ameliorated with weight loss [Citation35]. Recent reviews of the scientific literature suggest a role for dietary modification (such as calorie restriction and reduced carbohydrate intake) to ameliorate PCOS symptoms, but the findings are mixed and support an individualized approach to dietary modification in patients with PCOS [Citation36–38]. The AACE/ACE guidelines also specifically recommend patients with overweight or obesity and PCOS be considered for treatment with orlistat, metformin, and/or liraglutide because these medications can decrease weight and improve PCOS symptoms [Citation35]. A recent randomized Phase 3 study of women with PCOS and obesity found that treatment with liraglutide 3 mg for 32 weeks resulted in weight loss and improvement in hyperandrogenism symptoms [Citation39]. PCPs said difficulty with obesity management and lack of treatment efficacy were the top reasons patients with PCOS and obesity stop seeing them for PCOS management. These results suggest that PCPs understand the importance of obesity management in their patients with PCOS and obesity but lack awareness of, or confidence in, tools for obesity management.

4.7 PCPs with an obesity management focus compared to those without

PCPs with an obesity management focus are more familiar with PCOS and more confident to diagnose it themselves than those without an obesity management focus. PCPs with an obesity management focus were also more likely to discuss weight at every visit, refer patients to weight loss clinics, and prescribe anti-obesity medications. This may hold clues for how to equip more PCPs to be more effective at diagnosing and treating PCOS. Providing PCPs with education, resources, and actionable strategies for obesity management for their patients with PCOS and obesity may improve patient outcomes. Lifestyle change is still a primary recommendation for managing PCOS, but anti-obesity medications and bariatric surgery could also play important roles.

4.8 Limitations

Data, including body weight and PCOS diagnosis, was self-reported by patients with PCOS and obesity and by healthcare providers. Results reflect respondents’ perceptions and may differ in important ways from reality [Citation40]. Surveyed healthcare providers and patients are independent groups. Patients surveyed are not necessarily the patients of the healthcare providers surveyed. When the responses from healthcare providers and patients differ on a particular topic this may reflect real differences between the two groups rather than differences in perceptions. Patients responding to the survey were aware that they had PCOS and may represent a particularly informed subset of patients with PCOS. We must be cautious in generalizing the results of this survey to the wider population of patients with PCOS, particularly those who remain undiagnosed.

5. Conclusion

PCPs are often the first medical touchpoint for patients with PCOS and obesity, but PCPs play a smaller role in diagnosis and treatment. However, PCPs with an obesity management focus were more likely to make a diagnosis of PCOS themselves, to initiate treatment, to prescribe anti-obesity medications, and to refer patients to weight loss programs than PCPs without an obesity management focus. This suggests that improving PCP education on obesity management could improve PCP engagement in PCOS diagnosis and treatment. Empowering PCPs to confidently diagnose and treat patients with PCOS and obesity may improve time to diagnosis, time to intervention, patient satisfaction, and health outcomes for patients.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Dr. Sherif received travel compensation from Novo Nordisk to present data at a conference. Dr. Gill declares no conflicts of interest. Dr. Coborn is an employee of Novo Nordisk and owns stock in Novo Nordisk. Dr. Hoovler is an employee of Novo Nordisk and owns stock in Novo Nordisk. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (836 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank John Newman and Elizabeth Tanner of KJT Group, Inc. (Rochester, NY, USA) for medical writing and editing assistance and support (funding provided by Novo Nordisk).

Data availability statement

Data is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2022.2140511

Additional information

Funding

References

- Azziz R, Carmina E, Chen Z, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016 Aug 11;2(1):16057.

- Escobar-Morreale HF. Polycystic ovary syndrome: definition, aetiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018 May;14(5):270–284.

- Rotterdam. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004 Jan;81(1):19–25.

- Hart R, Doherty DA. The potential implications of a PCOS diagnosis on a woman’s long-term health using data linkage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Mar;100(3):911–919.

- Jason J. Polycystic ovary syndrome in the United States: clinical visit rates, characteristics, and associated health care costs. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Jul 11;171(13):1209–1211.

- Azziz R, Marin C, Hoq L, et al. Health care-related economic burden of the polycystic ovary syndrome during the reproductive life span. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Aug;90(8):4650–4658.

- Palomba S, de Wilde MA, Falbo A, et al. Pregnancy complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(5):575–592.

- Cooney LG, Lee I, Sammel MD, et al. High prevalence of moderate and severe depressive and anxiety symptoms in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2017 May 1;32(5):1075–1091.

- Cooney LG, Dokras A. Beyond fertility: polycystic ovary syndrome and long-term health. Fertil Steril. 2018 Oct;110(5):794–809.

- Gilbert EW, Tay CT, Hiam DS, et al. Comorbidities and complications of polycystic ovary syndrome: an overview of systematic reviews. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2018 Dec;89(6):683–699.

- Lim SS, Davies MJ, Norman RJ, et al. Overweight, obesity and central obesity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18(6):618–637.

- Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. Positions statement: criteria for defining polycystic ovary syndrome as a predominantly hyperandrogenic syndrome: an androgen excess society guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Nov;91(11):4237–4245.

- Mathur R, Alexander CJ, Yano J, et al. Use of metformin in polycystic ovary syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Dec;199(6):596–609.

- DeUgarte CM, Bartolucci AA, Azziz R. Prevalence of insulin resistance in the polycystic ovary syndrome using the homeostasis model assessment. Fertil Steril. 2005 May;83(5):1454–1460.

- Escobar-Morreale HF, San Millán JL. Abdominal adiposity and the polycystic ovary syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Sep;18(7):266–272.

- Matsuzawa Y, Funahashi T, Nakamura T. The concept of metabolic syndrome: contribution of visceral fat accumulation and its molecular mechanism. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2011;18(8):629–639.

- Mendrick DL, Diehl AM, Topor LS, et al. Metabolic syndrome and associated diseases: from the bench to the clinic. Toxicol Sci. 2018;162(1):36–42.

- Rojas J, Chávez M, Olivar L, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome, insulin resistance, and obesity: navigating the pathophysiologic labyrinth. Int J Reprod Med. 2014;2014:719050.

- Johansson J, Stener-Victorin E. Polycystic ovary syndrome: effect and mechanisms of acupuncture for ovulation induction. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:762615.

- Gibson-Helm M, Teede H, Dunaif A, et al. Delayed diagnosis and a lack of information associated with dissatisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Feb 1;102(2):604–612.

- Hoyos LR, Putra M, Armstrong AA, et al. Measures of patient dissatisfaction with health care in polycystic ovary syndrome: retrospective analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Apr 21;22(4):e16541.

- Lin AW, Bergomi EJ, Dollahite JS, et al. Trust in physicians and medical experience beliefs differ between women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2(9):1001–1009.

- Roe AH, Dokras A. The diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. Rev Obstet Gynecol. Summer 2011;4(2):45–51.

- de Melo AS, Dos Reis RM, Ferriani RA, et al. Hormonal contraception in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: choices, challenges, and noncontraceptive benefits. Open Access J Contracept. 2017;8:13–23.

- Ismayilova M, Yaya S. “I felt like she didn’t take me seriously”: a multi-methods study examining patient satisfaction and experiences with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in Canada. BMC Women's Health. 2022 Feb 23;22(1):47.

- Ismayilova M, Yaya S. ‘I’m usually being my own doctor’: women’s experiences of managing polycystic ovary syndrome in Canada. Int Health. 2022 May 14:ihac028.

- ACOG. ACOG practice bulletin No. 194 summary: polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun;131(6):1174–1176.

- Rosenfield RL, Ehrmann DA. The pathogenesis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): the hypothesis of PCOS as functional ovarian hyperandrogenism revisited. Endocr Rev. 2016 Oct;37(5):467–520.

- Godoy-Matos AF, Silva Júnior WS, Valerio CM. NAFLD as a continuum: from obesity to metabolic syndrome and diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2020 July 14;12(1):60.

- Kumarendran B, O’Reilly MW, Manolopoulos KN, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome, androgen excess, and the risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in women: a longitudinal study based on a United Kingdom primary care database. PLoS Med. 2018 Mar;15(3):e1002542.

- Ando Y, Jou JH. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and recent guideline updates. Clin Liver Dis. 2021 Jan 01;17(1):23–28.

- Kaur I, Suri V, Rana SV, et al. Treatment pathways traversed by polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) patients: a mixed-method study. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0255830.

- Tak YJ, Lee SY. Long-term efficacy and safety of anti-obesity treatment: where do we stand? Curr Obes Rep. 2021;10(1):14–30.

- Yanes Cardozo LL, Romero DG. Management of cardiometabolic complications in polycystic ovary syndrome: unmet needs. Faseb J. 2021 Nov;35(11):e21945.

- Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists and American College of endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016 Jul;22(Suppl 3):1–203.

- Barrea L, Frias-Toral E, Verde L, et al. PCOS and nutritional approaches: differences between lean and obese phenotype. Metabol Open.2021Dec;12:100123

- Neves LPP, Marcondes RR, Maffazioli GN, et al. Nutritional and dietary aspects in polycystic ovary syndrome: insights into the biology of nutritional interventions. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2020 Dec;36(12):1047–1050.

- Frias-Toral E, Garcia-Velasquez E, de Los Angeles Carignano M, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome and obesity: clinical aspects and nutritional management. Minerva Endocrinol (Torino). 2022 Jun;47(2):215–241

- Elkind-Hirsch KE, Chappell N, Shaler D, et al. Liraglutide 3 mg on weight, body composition, and hormonal and metabolic parameters in women with obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized placebo-controlled-phase 3 study. Fertil Steril. 2022;118(2):371–381.

- Short ME, Goetzel RZ, Pei X, et al. How accurate are self-reports? Analysis of self-reported health care utilization and absence when compared with administrative data. J Occup Environ Med. 2009 Jul;51(7):786–796.