ABSTRACT

Obesity negatively impacts patients’ health-related quality of life (QOL) and is associated with a range of complications such as type 2 diabetes (T2D), cardiovascular disease, and sleep apnea, alongside decreased physical function, mobility, and control of eating. The Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with obesity (STEP) trials compared once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg with placebo in adults with overweight or obesity, with or without T2D. This article reviews the effects of semaglutide 2.4 mg on QOL, control of eating, and body composition. Weight-related QOL was assessed using the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite Clinical Trials Version (IWQOL-Lite-CT), and health-related QOL was assessed with the 36-item Short Form Health Survey version 2 (SF-36v2®). Control of eating was evaluated using the Control of Eating questionnaire in a subgroup of participants in one trial. Body composition was evaluated via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry in another trial, in a subgroup of participants with a body mass index of ≤40 kg/m2. All IWQOL-Lite-CT scores (Physical Function, Physical, Psychosocial, and Total Score) improved with semaglutide 2.4 mg significantly more than with placebo. Across the trials, changes in SF-36v2 scores were generally in favor of semaglutide versus placebo. There were significant improvements in all Control of Eating questionnaire domains (craving control, craving for savory, craving for sweet, and positive mood) up to week 52 with semaglutide treatment versus placebo, with improvements in craving control and craving for savory remaining significantly different at week 104. Body composition findings showed that reductions in total fat mass were greater with semaglutide versus placebo. These findings highlight the wider benefits that patients can experience with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg, in addition to weight loss, including improvements in patients’ wellbeing and ability to perform daily activities. Taken together, these are important considerations for primary care when incorporating pharmacotherapy for weight management.

1. Introduction

Exploring the Wider Benefits of Semaglutide

Obesity is a chronic, relapsing disease that is associated with weight-related complications such as type 2 diabetes (T2D), cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis, urinary incontinence, and certain cancers [Citation1,Citation2]. The negative effects of obesity on quality of life (QOL) are multidimensional and dynamic, impacted by a range of factors including weight stigma and cravings [Citation3–6]. QOL differs between individuals, is changeable, and is influenced by the disparity between a person’s expectation of health and their experience of it [Citation3]. The degree of obesity is intrinsically linked with the level of QOL impairment, and the presence of comorbidities and weight-related complications can also impact QOL [Citation7–9]. Changes in body composition relating to increased fat mass not only negatively impact QOL but can result in decreased physical activity levels and mobility limitations [Citation10,Citation11]. In addition, excess adipose tissue leads to elevated levels of systemic inflammation, which mediates multiple pathogenic mechanisms, and is linked with cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, T2D, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome [Citation12]. While the daily lives of people with obesity can be physically impacted, obesity is also associated with mental health conditions such as anxiety, sleep disorders, low self-esteem, and eating disorders [Citation9,Citation13,Citation14]. Furthermore, widespread beliefs that weight control is a consequence of personal willpower result in weight stigma and discrimination, which is associated with weight gain and other detrimental consequences for both mental and physical health [Citation6,Citation15].

Weight loss can improve the health of people with overweight or obesity, decrease systemic inflammation, and prevent or reduce weight-related complications [Citation2,Citation12,Citation16]. A weight loss of 5–≥15% is recommended for patients with weight-related complications such as T2D, hypertension, and dyslipidemia; ≥10% is recommended for osteoarthritis; and >7–11% is recommended for obstructive sleep apnea [Citation2]. While a weight-loss goal for a beneficial effect on QOL has not been generally defined, a clear relationship has been shown between weight loss and improvements in QOL [Citation8,Citation16,Citation17]. However, it may be difficult to achieve and maintain weight loss through behavioral approaches, such as diet and exercise, alone [Citation18]. Food cravings experienced in everyday life may compound the potential for weight gain and impair the effectiveness of weight-loss efforts, leading to increased food consumption, particularly of calorically-dense foods [Citation19]. In addition, compensatory neuroendocrine mechanisms involving a multitude of hormones that regulate hunger, appetite, and satiety (such as ghrelin, leptin, glucagon-like peptide-1, cholecystokinin, and peptide YY) encourage weight regain after the weight loss [Citation20] and may persist for at least a year after the initial weight loss [Citation21–23]. Thus, there is a strong physiological basis for relapse among people with obesity [Citation5,Citation22].

Treatment with pharmacotherapies, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), can achieve sustained weight loss by targeting weight-regulating neuroendocrine pathways [Citation21,Citation24,Citation25], and can result in improved QOL [Citation26]. The GLP-1RAs subcutaneous liraglutide 3 mg once daily and subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg once weekly are US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for chronic weight management among people with overweight in the presence of at least one weight-related comorbidity or obesity [Citation27,Citation28]; they are also approved at lower doses to improve glycemic control in adults with T2D and to reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in adults with T2D and established cardiovascular disease [Citation29,Citation30]. The global phase 3 Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with obesity (STEP) program assessed the efficacy and safety of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg for weight management in adults with overweight (body mass index [BMI] ≥27.0 kg/m2) with at least one weight-related comorbidity, or obesity (BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2), with or without T2D [Citation24,Citation31–35]. Here we review the effects of semaglutide 2.4 mg on weight- and health-related QOL, control of eating, and body composition. This article aims to give primary care providers a deeper understanding of the wider effects of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg treatment in addition to weight loss and of the potential benefits these could have on the daily lives of people with overweight or obesity.

Article overview and relevance to your clinical practice

This supplement summarizes key efficacy and safety results from the global phase 3 STEP program for once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg, which is approved for weight management in adults with overweight or obesity with or without T2D.

In this third article in the supplement, we focus on the effects of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg versus placebo on weight- and health-related QOL, control of eating, and body composition.

ln STEP 1 and 2, adults with overweight or obesity, with or without T2D, experienced significant improvements in weight-related QOL with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg versus placebo, as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention.

Further benefits associated with semaglutide 2.4 mg treatment in the STEP program included improvements in health-related QOL, control of eating, and body composition versus placebo.

2. The STEP 1–5 trials

2.1. Trial design overview

Adults with overweight or obesity received once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg or placebo for 68 weeks in STEP 1–3 [Citation31,Citation33,Citation34] and for 104 weeks in STEP 5 [Citation35]. In STEP 4, all participants received semaglutide 2.4 mg for a 20-week run-in period, then were randomized at week 20 (baseline) to continue treatment with semaglutide or were switched to placebo for the remaining 48 weeks [Citation32]. In all five trials, semaglutide dose-escalation was implemented over a 16-week period to reach the target dose of 2.4 mg [Citation24]. Participants received treatment as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention (500 kcal/day-deficit diet and 150 minutes/week of physical activity) in STEP 1, 2, 4, and 5, whereas intensive behavioral therapy and a low-calorie diet with meal replacements (1000–1200 kcal/day) for the initial 8 weeks was provided in STEP 3 followed by a hypocaloric diet [Citation31–35]. STEP 2 enrolled participants who had been diagnosed with T2D, with an average glycated hemoglobin of 8.1% and duration of diabetes of 8 years [Citation31]. While STEP 1–5 trials did not include children and adolescents, the safety and efficacy of semaglutide 2.4 mg is being investigated in adolescents aged 12–17 years in the ongoing STEP TEENS trial (NCT04102189).

2.2. Evaluation of quality of life, control of eating, and body composition

As well as the primary weight loss endpoints, weight- and health-related QOL, control of eating, and body composition were evaluated across the STEP trials as a mixture of confirmatory secondary, supportive secondary, and exploratory endpoints, as detailed below. In STEP 1 and 2, weight-related QOL was assessed using the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite for Clinical Trials Version (IWQOL-Lite-CT) questionnaire [Citation31,Citation34], and health-related QOL was assessed in STEP 1–4 using the 36-item Short Form Health Survey version 2 (SF-36v2®) questionnaire [Citation31–34]. Changes from baseline in IWQOL-Lite-CT Physical Function and SF-36v2 Physical Functioning scores were confirmatory secondary endpoints. Changes in IWQOL-Lite-CT Psychosocial and Total scores were supportive secondary endpoints, as were SF-36v2 Role-Physical, Bodily Pain, General Health, Vitality, Social Functioning, Role-Emotional, Mental Health, Physical Component Summary, and Mental Component Summary scores [Citation31–34]. As supportive secondary endpoint analyses were not adjusted for multiplicity, P-values were not reported in the primary publications for many of these endpoints. Control of eating was assessed as an exploratory endpoint in a subgroup of participants in STEP 5; P-values for these data were not adjusted for multiplicity [Citation36]. In STEP 1, body composition was assessed as a supportive secondary endpoint in a subgroup of participants [Citation34].

2.3. Endpoint assessments

2.3.1. Quality of life

2.3.1.1. Weight-related quality of life

The IWQOL-Lite was originally developed to assess weight-related physical and psychosocial functioning [Citation37]. An alternative version of the questionnaire, the IWQOL-Lite-CT, was developed for use in patient populations typically targeted for weight management clinical trials, in accordance with FDA guidance [Citation14,Citation38].

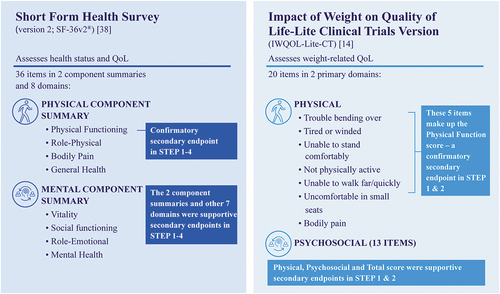

The IWQOL-Lite-CT was first used in the STEP 1 and 2 trials and has been recently validated based on these results [Citation39]. This 20-item patient-reported outcome instrument evaluates weight-related Physical (seven items) and Psychosocial (13 items) functioning () [Citation14]. Within the Physical domain, five items are assessed for the Physical Function composite score: trouble bending over; tired or winded; unable to stand comfortably; not physically active; and unable to walk far/quickly. Two additional items (uncomfortable in small seats, bodily pain) are not included in the Physical Function score but are in the Physical domain [Citation14]. The Psychosocial domain encompasses a range of items for evaluation including self-conscious eating in social settings, less confident, feel judged by others, and frustrated shopping for clothes. Overall, the range of possible scores for the IWQOL-Lite-CT is 0–100, with higher values indicating better patient functioning [Citation14]. No assessment of correlation between gastrointestinal adverse events, such as nausea, and the willingness of participants to perform daily activities and exercise were made within the STEP clinical trials.

2.3.1.2. Health-related quality of life

Participants in the STEP 1–4 trials (N = 4585) completed the SF-36v2, a patient-reported outcome instrument that measures health-related QOL not specific to age, disease, or treatment group () [Citation31–34,Citation40,Citation41]. The SF-36v2 consists of eight domains that are divided into two component summaries, the Physical Component Summary and the Mental Component Summary. The Physical Component Summary includes the four domains of Physical Functioning, Role-Physical, Bodily Pain, and General Health. The Physical Functioning domain includes questions on whether the respondent’s health limits specific daily physical activities, such as carrying out moderate or vigorous activities, walking more than a mile, and climbing several flights of stairs. The Role-Physical domain includes questions on whether any problems have been experienced with work or regular daily activities as a result of their health, including if they have accomplished less or if they needed to cut down the amount of time spent on activities. Bodily Pain assesses how much physical pain is experienced and the impact of this, and the General Health domain evaluates how they feel about their health. The Mental Component Summary includes the domains of Vitality, Social Functioning, Role-Emotional, and Mental Health. The Vitality domain includes questions on their energy levels, Social Functioning on how much their health has interfered with social activities, Role-Emotional on whether work or other regular daily activities have been impacted by emotional problems, and Mental Health on whether they have felt nervous, happy, peaceful, or down. Overall, SF-36v2 scores are norm-based scores, i.e. transformed to a scale where the 2009 US general population has a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10, with higher scores representing better health-related QOL [Citation40,Citation41].

2.3.2. Control of eating

To assess the intensity and type of food cravings, as well as subjective sensations of appetite, hunger, fullness, and mood, a subgroup of participants in STEP 5 from Canada/USA were evaluated using the Control of Eating patient-reported outcome questionnaire [Citation36]. Scores from 19 individual items were grouped into four domains for craving control, craving for savory, craving for sweet, and positive mood. Data were not collected for circulating hormones related to hunger control.

2.3.3. Body composition

In STEP 1, body composition was assessed in a subgroup of 140 participants with a BMI ≤40 kg/m2 [Citation34,Citation42]. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), which differentiates between bone mass, fat mass, and lean body mass, was used to evaluate total fat mass and total lean body mass at baseline and week 68. These were calculated both as absolute mass (kg) and as percent of total body mass [Citation34]. The impact of body composition changes on functional capacity were not assessed. Assessment of body composition in STEP 1 enabled evaluation of whether weight loss with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg treatment was primarily due to fat loss, rather than lean body mass (muscle), in line with guidance from the FDA and European Medicines Agency [Citation34,Citation43,Citation44].

Key clinical take-home points: Evaluation of quality of life, control of eating, and body composition

The STEP 1–5 trials investigated the effects of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg in adults with overweight or obesity.

As well as the primary weight loss endpoints, QOL, control of eating, and body composition were evaluated.

Two different questionnaires were used to assess QOL:

Weight-related QOL was assessed using the IWQOL-Lite-CT questionnaire in STEP 1 and 2;

Health-related QOL was assessed using the SF-36v2 questionnaire in STEP 1–4.

Control of eating was assessed using the Control of Eating questionnaire in a subgroup of participants in STEP 5.

Body composition was assessed using DEXA scanning in a subgroup of participants in STEP 1.

3. Effects of semaglutide 2.4 mg on quality of life, control of eating, and body composition

3.1. Key weight loss results from STEP 1–5

The STEP 1–5 trials demonstrated significant and sustained, clinically relevant reductions in body weight with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg compared with placebo [Citation31–35]. The reported body weight changes from baseline to week 68 (STEP 1–3) or week 104 (STEP 5) for patients receiving treatment with semaglutide 2.4 mg versus placebo were: STEP 1, –14.9% versus –2.4%; STEP 2, –9.6% versus –3.4%; STEP 3, –16.0% versus –5.7%; STEP 5, –15.2% versus –2.6%. Meanwhile, the STEP 4 study demonstrated the benefit of maintenance treatment with semaglutide: after the initial weight loss of –10.6% during the 20-week semaglutide run-in period, continued semaglutide 2.4 mg treatment was associated with an additional significant reduction in body weight (–7.9%) compared with an increase in body weight (+6.9%) with a switch to placebo.

3.2. Quality of life

3.2.1. Weight-related quality of life results from STEP 1 and 2 (IWQOL-Lite-CT)

In STEP 1 and 2, results from the weight-specific QOL questionnaire, IWQOL-Lite-CT, showed improvements from baseline in all domain scores (Physical Function [], Physical, Psychosocial, and Total score) that were significantly greater with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg than with placebo at week 68 (STEP 1, P < 0.001; STEP 2, P < 0.01) [Citation31,Citation34,Citation45–48]. To define a clinically meaningful within-person improvement, an obesity-specific responder threshold for each domain score (Physical [≥13.5 points], Physical Function [≥14.6 points], Psychosocial [≥16.2 points], and Total [≥16.6 points]) was derived in accordance with FDA guidance on patient-reported outcome measures [Citation31,Citation34,Citation38,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49]. There were significantly more patients achieving the clinically meaningful improvement threshold with semaglutide 2.4 mg versus placebo for all IWQOL-Lite-CT scores in STEP 1 (P < 0.001 for all: Physical Functioning, 52.1% vs 32.9%; Physical, 49.5% vs 31.6%; Psychosocial, 47.8% vs 25.4%; Total, 43.8% vs 21.9%) and for most IWQOL-Lite-CT scores in STEP 2 (Physical Functioning, 42.6% vs 31.0% [P = 0.009]; Physical, 40.2% vs 28.5% [P = 0.012]; Psychosocial, 26.3% vs 18.6% [P = 0.079]; Total, 26.3% vs 17.5% [P = 0.048]) [Citation31,Citation34,Citation45–48]. It should be noted that baseline scores impacted the proportions of participants able to achieve clinically meaningful improvements. For some patients, their baseline scores for some domains were close enough to the maximum possible scores that an increase in score of the amount required to be clinically meaningful was impossible. In STEP 2, for example, the proportions of participants who could not be responders by domain were 25.0% for Physical Function, 21.7% for Physical, 43.0% for Psychosocial, and 36.6% for Total [Citation49].

Figure 2. Effect of semaglutide versus placebo on IWQOL-Lite-CT Physical Function scores in STEP 1 and 2 [Citation31,Citation34].

![Figure 2. Effect of semaglutide versus placebo on IWQOL-Lite-CT Physical Function scores in STEP 1 and 2 [Citation31,Citation34].](/cms/asset/65ae78cd-7428-4c11-982b-d0e78de3f977/ipgm_a_2150006_f0002_c.jpg)

3.2.1.1. The impact of sex on IWQOL-Lite-CT scores in STEP 2

The impact of obesity on health-related QOL has been reported to be worse in females compared with males [Citation50,Citation51], most notably in terms of a greater negative effect on mental health [Citation51]. Additional analyses of STEP 2 data (participants with T2D) evaluated changes in IWQOL-Lite-CT scores from baseline to week 68 by sex for once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg compared with placebo, and showed no significant treatment-by-sex interaction on mean score changes for each domain [Citation49]. However, mean score changes favored once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide versus placebo for all domains (Physical Function, Physical, Psychosocial, and Total) for females but not males [Citation49]. It is important to note that understanding the impact of sex on QOL after weight loss is complex and deserves further study.

3.2.1.2. IWQOL-Lite-CT score differences between STEP 1 and 2

Baseline IWQOL-Lite-CT Psychosocial scores were lower in STEP 1 than in STEP 2 [Citation46,Citation47]. This finding could indicate worse perceived psychosocial functioning among those with overweight or obesity alone than those also with T2D. It may also reflect the higher baseline mean BMI and body weight in the STEP 1 trial (38 kg/m2 and 105.3 kg, respectively) compared with STEP 2 (36 kg/m2 and 99.8 kg, respectively). Given the focus of this assessment on perception of self in society (e.g. body image, body shape and size, and sense of judgment by others), it may be that the individual’s QOL experience with obesity is viewed through the lens of weight-related stigma [Citation6]. Furthermore, greater treatment benefit with semaglutide versus placebo was seen for all IWQOL-Lite-CT domains (+9.1–10.5 points) in individuals in STEP 1 (who lost more weight) [Citation47], compared to those in STEP 2 (+2.9–4.9 points); this may reflect the importance that weight loss plays in QOL but could also be a result of the greater baseline QOL scores in STEP 2, allowing less scope for improvement.

Beyond body weight and BMI, there were other key differences between the STEP 1 and STEP 2 patient populations in terms of mean age (46 years and 55 years, respectively), and proportion of female patients (74.1% and 50.9%, respectively), as well as in T2D status (excluded in STEP 1 and required in STEP 2) [Citation31,Citation34]. Furthermore, as noted earlier, the magnitude of weight loss with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg was greater in STEP 1 than in STEP 2 [Citation31,Citation34]. In addition, it must also be noted that the majority of the IWQOL-Lite-CT questions begin with ”because of my weight,” explicitly requiring the respondent to focus on the contribution of their weight [Citation37]. In STEP 2, participants were all aware that their T2D was relevant to their inclusion in the trial, and therefore it is possible that they may have considered the relative contributions of weight and T2D to each impact, but we cannot rule out that their T2D did not affect how they responded to the questionnaire. Collectively, these between-trial differences in patient population and changes in body weight may have influenced QOL results, and differences between trials should therefore be interpreted cautiously. Understanding the differences between disease states and perceived QOL is an area that warrants exploration in the future.

3.2.2. Health-related quality of life results from STEP 1–4 (SF-36v2)

Across STEP 1–4, improvements in SF-36v2 scores were typically greater with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg than placebo [Citation31–34].

In STEP 1, there were significantly greater improvements with semaglutide 2.4 mg than with placebo in Physical Functioning (), Role-Physical, Bodily Pain, General Health, Vitality, Social Functioning, Physical Component Summary (P < 0.001 for all), Mental Health (P = 0.003), and Mental Component Summary (P = 0.027) scores, but not in Role-Emotional (P = 0.098) [Citation34,Citation47]. In STEP 2, improvements were smaller than in STEP 1, but were significantly greater with semaglutide 2.4 mg compared with placebo for Physical Functioning (P = 0.006), General Health (P = 0.003), Mental Health (P = 0.046), and Physical Component Summary (P = 0.036); non-significant changes appeared to favor semaglutide for Role-Physical (P = 0.282), Bodily Pain (P = 0.499), Vitality (P = 0.068), Social Functioning (P = 0.631), and Mental Component Summary (P = 0.504), and similar changes between treatment groups were observed for Role-Emotional (P = 0.856) [Citation31,Citation46].

Figure 3. Effect of semaglutide versus placebo on SF-36v2 Physical Functioning scores in STEP 1–4 [Citation31–34].

![Figure 3. Effect of semaglutide versus placebo on SF-36v2 Physical Functioning scores in STEP 1–4 [Citation31–34].](/cms/asset/26d481ad-4f6a-4b57-87d2-af91aa810b58/ipgm_a_2150006_f0003_c.jpg)

In STEP 3, the SF-36v2 Mental Component Summary score improved significantly (P < 0.011) more with semaglutide 2.4 mg compared with placebo; non-significant differences favored semaglutide for Physical Functioning (; P = 0.12) and Physical Component Summary scores (P = 0.27) [Citation33]. It should be noted that participants in both treatment groups received intensive behavioral therapy and a low-calorie diet with meal replacements for the initial 8-weeks (as opposed to less intensive lifestyle intervention in other STEP trials). As a result, mean weight loss in the placebo group in STEP 3 (5.7%) was greater than seen in STEP 1 (2.4%), while the reductions with semaglutide 2.4 mg were similar (16.0% and 14.9%, respectively) [Citation33,Citation34]. Notably, the weight decrease in the placebo group in STEP 3 exceeded the consensus threshold for clinically meaningful weight loss (≥5%), a threshold that has been associated with positive benefits on health-related QOL, particularly physical components of QOL [Citation52]. This, combined with the slightly smaller difference in weight loss between the semaglutide 2.4 mg and placebo arms in STEP 3 versus STEP 1, may have contributed to the less substantial improvement in physical functioning seen with semaglutide 2.4 mg versus placebo in STEP 3 [Citation33]. Improvement in physical function has been shown to be directly related to the amount of weight lost in the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study of participants with overweight or obesity and T2D who received either intensive lifestyle intervention or diabetes support and education [Citation53]. Those individuals who achieved a target weight loss of ≥7% had better physical function than those who did not meet their target.

In STEP 4, changes in all SF-36v2 scores (Physical Functioning [], Role-Physical, Bodily Pain, General Health, Vitality, Social Functioning, Physical Component Summary, Mental Health, Role-Emotional, and Mental Component Summary) significantly improved from randomization at week 20 (baseline) to week 68 with continued semaglutide 2.4 mg treatment, whereas they deteriorated among those switching to placebo (semaglutide 2.4 mg vs placebo differences were P < 0.05 for all domains) [Citation32,Citation54].

3.2.2.1. The impact of sex on SF-36v2 scores in STEP 2

There was no significant treatment-by-sex interaction across SF-36v2 domains [Citation49]. Changes in SF-36v2 favored once weekly subcutaneous semaglutide versus placebo in Physical Functioning and General Health domains in males, and General Health and Mental Health domains for females [Citation49].

3.2.2.2. SF-36v2 score differences between STEP 1 and 2

Baseline scores among people with overweight or obesity in STEP 1 and those also with T2D in STEP 2 were generally comparable [Citation31,Citation34,Citation46,Citation48]. However, Physical Functioning, General Health, and the Physical Component Summary scores were slightly lower in STEP 2 than STEP 1, suggesting worse perceived physical functioning in those with T2D [Citation46]. These results differ from those observed for the obesity-specific QOL measure IWQOL-Lite-CT and could be due to the use of a disease-specific, versus a disease-generic, patient-reported outcome instrument, alongside differences in the perceived disease burden for these two populations [Citation14,Citation39,Citation41,Citation55]. As noted earlier, differences in magnitude of weight loss between STEP 1 and STEP 2 may have contributed to the differences in QOL score improvement between trials.

3.3. Control of eating results from STEP 5

While some studies suggest that weight loss interventions can increase appetite, hunger, and craving [Citation22,Citation56], most suggest decreases in those phenomena with such interventions [Citation56–58]. However, these phenomena can differ during the intervention and during maintenance therapy. The relationship between food restriction and food craving is complex and there is evidence to suggest that there are both physiological and psychological mediatory mechanisms involved [Citation56]. Food cravings can vary by weight loss intervention and individual, and are further complicated by mood, situational factors, physical activity, food cues/exposure, and dysregulated eating behaviors such as binge eating [Citation5,Citation56,Citation59]. Therefore, it is important to evaluate how treatment with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg impacts a patient’s perceived control of eating.

Results from earlier trials with semaglutide showed significantly reduced hunger, better control of eating, and fewer/weaker food cravings when compared with placebo [Citation60,Citation61]; significantly (P < 0.05) reduced prospective food consumption, increased fullness and satiety were observed in one study [Citation61], and a significantly (P < 0.05) lower preference for high fat foods observed in another [Citation60]. In STEP 5, treatment with semaglutide 2.4 mg, compared to placebo, resulted in significantly greater improvements in all four domain scores of the Control of Eating questionnaire (craving control, craving for savory, craving for sweet, and positive mood) at weeks 20 and 52 (all P < 0.05) [Citation36]. The improvements for craving control and craving for savory domains were sustained to week 104 (P < 0.01) [Citation36]. Items relating to resisting cravings and difficulty in control of eating were significantly reduced from baseline to week 104 (both P < 0.05); hunger and fullness also improved, but the differences were only significant at week 20 (P < 0.001) [Citation36]. Further research is needed to examine the relationship between control of eating, perceived stress, and QOL, and how these are impacted during and after acute weight loss.

3.4. Body composition results from STEP 1

To ascertain whether weight loss with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg treatment was primarily due to fat loss, rather than lean body mass, a subgroup of participants in STEP 1 with a body mass index of ≤40 kg/m2 were evaluated for their body composition via DEXA. During the trial, body weight in this subgroup decreased from baseline to week 68 by 15.0% with semaglutide 2.4 mg and 3.6% with placebo [Citation42]. At baseline, body composition for the semaglutide group was 43.4% (42.1 kg) total fat mass and 53.9% (52.4 kg) total lean body mass, and for the placebo group was 44.6% (43.3 kg) and 52.7% (51.5 kg), respectively [Citation34]. Resulting body composition changes from baseline to week 68 with semaglutide 2.4 mg were –8.36 kg total fat mass and –5.26 kg total lean body mass, compared with –1.37 kg and –1.83 kg for placebo, respectively () [Citation34]. These results are consistent with previous studies with semaglutide 1.0 mg, oral semaglutide, and liraglutide, which showed that weight loss with these agents was predominantly due to loss of fat mass rather than lean body mass [Citation60,Citation62,Citation63]. Despite the greater loss of lean body mass versus fat mass observed for the placebo group in STEP 1, preferential loss of fat mass is typically also seen with non-pharmacological weight-loss interventions [Citation64,Citation65].

Figure 4. Effect of semaglutide and placebo on body composition from baseline to week 68 in STEP 1 [Citation34,Citation42].

![Figure 4. Effect of semaglutide and placebo on body composition from baseline to week 68 in STEP 1 [Citation34,Citation42].](/cms/asset/56bc4661-6e90-45bd-8e48-e93ea21d77c3/ipgm_a_2150006_f0004_c.jpg)

Body composition may also influence physical functioning; for example, a greater percentage of fat-free mass has been shown to correlate with greater walking capacity in patients with obesity, when evaluated by the distance that can be walked in 6 minutes (6-minute walking test) [Citation66]. Weight loss has been associated with increased walking capacity when evaluated using the 6-minute walking test in a pooled group of participants receiving liraglutide and placebo with intensive behavioral therapy and in a group of participants in a lifestyle change weight loss program [Citation67]; however, these studies did not report whether these improvements were correlated with changes in body composition. Although the 6-minute walking test was evaluated in STEP 2 to provide indication of muscle function and functional exercise capacity, these results have not been reported. As well as evaluating the impact of weight loss on fat mass loss and lean body mass, it is important to assess the effects of body composition changes on muscle function. Future research into these effects is warranted alongside the impact these changes may have on QOL.

Key clinical take-home points: The effects of semaglutide 2.4 mg on quality of life, control of eating, and body composition

Weight-related QOL: In STEP 1 and 2, all IWQOL-Lite-CT scores (Physical Function, Physical, Psychosocial, and Total score) improved significantly more with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg than with placebo.

Health-related QOL: Across STEP 1–4, changes in SF-36v2 scores were generally in favor of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg versus placebo.

Control of eating: In STEP 5, all four domain scores of the Control of Eating questionnaire (craving control, craving for savory, craving for sweet, and positive mood) were significantly improved with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg compared with placebo at week 20 and 52, and remained significantly improved for craving control and craving for savory at week 104.

Body composition: In STEP 1, reductions in total fat mass were greater with semaglutide 2.4 mg compared with placebo.

4. Conclusions

In addition to the well-established benefits of weight loss in reducing the risks of obesity-related complications, weight loss can also lead to wider improvements of crucial relevance to people with obesity. Weight loss alongside improved functioning and well-being can provide important benefits for people with obesity and positively impact their daily lives [Citation68]. In the STEP trials, substantial weight loss was observed with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg, together with significant improvements in weight- and health-related QOL, cravings, and control of eating. There were also additional weight loss benefits, including improvements in body composition. The authors believe that despite the added expense of treatment with semaglutide 2.4 mg, the considerable degree of improvements across a multitude of outcomes would translate to a longer-term reduction in the burden of obesity on the healthcare system and will strengthen the argument for broader insurance cover in the future. These findings help to encourage primary care providers to be informed of the wider day-to-day benefits beyond weight loss, including day-to-day functional improvements, that can be achieved with semaglutide 2.4 mg treatment for people with overweight or obesity.

Abbreviations

BMI, body mass index

CI, confidence interval

DEXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

ETD, estimated treatment difference

FDA, US Food and Drug Administration

GLP-1RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist

IBT, intensive behavioral therapy

IWQOL-Lite-CT, Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite Clinical Trials Version

OW, once weekly

QOL, quality of life

SF-36v2, 36-item Short Form Health Survey version 2

STEP, Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with obesity

T2D, type 2 diabetes

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Patrick M. O’Neil: research grants to his university – Eli Lilly, Epitomee Medical, Novo Nordisk, and WW International; fees for consulting or advisory board participation – Gedeon Richter and Pfizer; and honoraria for non-promotional talks – Novo Nordisk and Robard.

Domenica M. Rubino: investigator, consultant, and speaker – Novo Nordisk; investigator – Boehringer Ingelheim and Epitomee Medical; and honoraria for CME talks – Endocrine Society, PeerView, and WebMD.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Nicole Cash, PhD, of Axis, a division of Spirit Medical Communications Group Limited, and Emma Marshman, PhD, a contract writer working on behalf of Axis (and were funded by Novo Nordisk Inc.), under direction of the authors. Novo Nordisk Inc. also performed a medical accuracy review.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH, et al. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):715–723.

- Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(Suppl 3):1–203.

- Carr AJ, Gibson B, Robinson PG. Measuring quality of life: is quality of life determined by expectations or experience? BMJ. 2001;322(7296):1240–1243.

- White MA, O’Neil PM, Kolotkin RL, et al. Gender, race, and obesity-related quality of life at extreme levels of obesity. Obes Res. 2004;12(6):949–955.

- Zorjan S, Schienle A. Temporal dynamics of mental imagery, craving and consumption of craved foods: an experience sampling study. Psychol Health. 2022;1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2022.2033239

- Emmer C, Bosnjak M, Mata J. The association between weight stigma and mental health: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2020;21(1):e12935.

- Ul-Haq Z, Mackay DF, Fenwick E, et al. Meta-analysis of the association between body mass index and health-related quality of life among children and adolescents, assessed using the pediatric quality of life inventory index. J Pediatr. 2013;162(2):280–286.e1.

- Kolotkin RL, Andersen JR. A systematic review of reviews: exploring the relationship between obesity, weight loss and health-related quality of life. Clin Obes. 2017;7(5):273–289.

- Stephenson J, Smith CM, Kearns B, et al. The association between obesity and quality of life: a retrospective analysis of a large-scale population-based cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1990.

- Chlabicz M, Dubatowka M, Jamiolkowski J, et al. Subjective well-being in non-obese individuals depends strongly on body composition. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):21797.

- Mikkola TM, Kautiainen H, von Bonsdorff MB, et al. Body composition and changes in health-related quality of life in older age: a 10-year follow-up of the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(8):2039–2050.

- Berg AH, Scherer PE. Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2005;96(9):939–949.

- Avila C, Holloway AC, Hahn MK, et al. An overview of links between obesity and mental health. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4(3):303–310.

- Kolotkin RL, Williams VSL, Ervin CM, et al. Validation of a new measure of quality of life in obesity trials: Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite Clinical Trials Version. Clin Obes. 2019;9(3):e12310.

- Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(5):941–964.

- Bischoff SC, Damms-Machado A, Betz C, et al. Multicenter evaluation of an interdisciplinary 52-week weight loss program for obesity with regard to body weight, comorbidities and quality of life–a prospective study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012;36(4):614–624.

- Zawisza K, Tobiasz-Adamczyk B, Galas A, et al. Changes in body mass index and quality of life—population-based follow-up study COURAGE and COURAGE-POLFUS, Poland. Appl Res Qual Life. 2021;16(2):501–526.

- Greenway FL. Physiological adaptations to weight loss and factors favouring weight regain. Int J Obes (Lond). 2015;39(8):1188–1196.

- Boswell RG, Kober H. Food cue reactivity and craving predict eating and weight gain: a meta-analytic review. Obes Rev. 2016;17(2):159–177.

- Sumithran P, Proietto J. The defence of body weight: a physiological basis for weight regain after weight loss. Clin Sci (Lond). 2013;124(4):231–241.

- Sweeting AN, Hocking SL, Markovic TP. Pharmacotherapy for the treatment of obesity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;418 Pt 2:173–183.

- Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, et al. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(17):1597–1604.

- Blomain ES, Dirhan DA, Valentino MA, et al. Mechanisms of weight regain following weight loss. ISRN Obes. 2013;2013:210524.

- Kushner RF, Calanna S, Davies M, et al. Semaglutide 2.4 mg for the treatment of obesity: key elements of the STEP trials 1 to 5. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28(6):1050–1061.

- Rose F, Bloom S, Tan T. Novel approaches to anti-obesity drug discovery with gut hormones over the past 10 years. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2019;14(11):1151–1159.

- Bays H, Pi-Sunyer X, Hemmingsson JU, et al. Liraglutide 3.0 mg for weight management: weight-loss dependent and independent effects. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(2):225–229.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Saxenda® highlights of prescribing information. 2014 [cited 2022 Aug 9]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/206321Orig1s000lbl.pdf

- US Food and Drug Administration. Wegovy highlights of prescribing information. 2021 [cited 2022 Aug 9]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/215256s000lbl.pdf

- US Food and Drug Administration. Victoza® highlights of prescribing information. 2010 [cited 2022 Aug 9]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/022341s035lbl.pdf

- US Food and Drug Administration. Ozempic® highlights of prescribing information. 2017 [cited 2022 Aug 9]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/209637s003lbl.pdf

- Davies M, Færch L, Jeppesen OK, et al. Semaglutide 2·4 mg once a week in adults with overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (STEP 2): a randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10278):971–984.

- Rubino D, Abrahamsson N, Davies M, et al. Effect of continued weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo on weight loss maintenance in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 4 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(14):1414–1425.

- Wadden TA, Bailey TS, Billings LK, et al. Effect of subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo as an adjunct to intensive behavioral therapy on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(14):1403–1413.

- Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(11):989–1002.

- Garvey TW, Batterham RL, Bhatta M, et al. Two-year effect of semaglutide 2.4 mg vs placebo in adults with overweight or obesity: STEP 5. Abstract presented at the 39th Annual Meeting of the Obesity Society at ObesityWeek® [Oral 096]; 2021 Nov 1–5; Virtual 2021.

- Wharton S, Batterham RL, Bhatta M, et al. Two-year effect of semaglutide 2.4 mg on control of eating in adults with overweight/obesity: STEP 5. Abstract presented at the 39th Annual Meeting of the Obesity Society at ObesityWeek® [Oral 095]; 2021 Nov 1–5; Virtual 2021.

- Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD, et al. Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9(2):102–111.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. 2009 [cited 2022 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/77832/download

- Kolotkin RL, Williams VSL, von Huth Smith L, et al. Confirmatory psychometric evaluations of the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite Clinical Trials Version (IWQOL-Lite-CT). Clin Obes. 2021;11(5):e12477.

- Maruish ME, editor. User’s manual for the SF-36v2 health survey. QualityMetric Inc. 3rd ed. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Inc; 2011.

- Ware JE Jr., Gandek B. Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) project. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):903–912.

- Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Impact of semaglutide on body composition in adults with overweight or obesity: exploratory analysis of the STEP 1 study. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5(Suppl 1):A16–A17.

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on clinical evaluation of medicinal products used in weight management. 2016 [cited 2022 Aug 9]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-clinical-evaluation-medicinal-products-used-weight-management-revision-1_en.pdf

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry developing products for weight management. 2007 [cited 2022 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/71252/download

- Wharton S, Bjorner JB, Kushner RF, et al. AD12.08: Semaglutide 2.4 mg once weekly improves patient-reported outcome measures of physical functioning in adults with overweight or obesity in the STEP 1 trial. Obes Facts. 2021;14(Suppl 1):1–154. pg 52.

- Rubino D, Færch L, Meincke HH, et al. 84-OR: Semaglutide 2.4 mg improves health-related quality of life in adults with overweight/obesity and type 2 diabetes in the STEP 2 trial. Diabetes. 2021;70(Supplement 1):84–OR.

- Rubino DM, Bjorner JB, Kushner RF, et al. EP4-25: Beneficial effect of semaglutide 2.4 mg once weekly on patient-reported outcome measures of weight-related and health-related quality of life in adults with overweight or obesity in the STEP 1 trial. Obes Facts. 2021;14(Suppl 1):1–154. pg 118.

- Wharton S, Meincke HH, Kushner RF, et al. 85-OR: Semaglutide 2.4 mg improves patient reported outcome measures of physical functioning in adults with overweight/obesity and type 2 diabetes in the STEP 2 trial. Diabetes. 2021;70(Supplement 1):85–OR.

- Rubino D, Færch L, Meincke HH, et al. 84-OR: Semaglutide 2.4 mg improves health-related quality of life in adults with overweight/obesity and type 2 diabetes in the STEP 2 trial. Presentation at the 81st Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association; 2021 June 25–29; Virtual 2021.

- Muennig P, Lubetkin E, Jia H, et al. Gender and the burden of disease attributable to obesity. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(9):1662–1668.

- Audureau E, Pouchot J, Coste J. Gender-related differential effects of obesity on health-related quality of life via obesity-related comorbidities: a mediation analysis of a French nationwide survey. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9(3):246–256.

- Horn DB, Almandoz JP, Look M. What is clinically relevant weight loss for your patients and how can it be achieved? A narrative review. Postgrad Med. 2022;134(4):359–375.

- Houston DK, Leng X, Bray GA, et al. A long-term intensive lifestyle intervention and physical function: the Look AHEAD Movement and Memory study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(1):77–84.

- Sharma A, Meincke H, Jensen C, et al. Continued semaglutide 2.4 mg once weekly improved health related quality of life in the STEP 4 trial. Abstract presented at the 39th Annual Meeting of the Obesity Society at ObesityWeek® [Oral 014]; 2021 Nov 1–5; Virtual 2021.

- Abraham SB, Abel BS, Rubino D, et al. A direct comparison of quality of life in obese and Cushing’s syndrome patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;168(5):787–793.

- Meule A. The psychology of food cravings: the role of food deprivation. Curr Nutr Rep. 2020;9(3):251–257.

- Myers CA, Martin CK, Apolzan JW. Food cravings and body weight: a conditioning response. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2018;25(5):298–302.

- Martin CK, O’Neil PM, Pawlow L. Changes in food cravings during low-calorie and very-low-calorie diets. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(1):115–121.

- Morin I, Bégin C, Maltais-Giguère J, et al. Impact of experimentally induced cognitive dietary restraint on eating behavior traits, appetite sensations, and markers of stress during energy restriction in overweight/obese women. J Obes. 2018;2018:4259389.

- Blundell J, Finlayson G, Axelsen M, et al. Effects of once-weekly semaglutide on appetite, energy intake, control of eating, food preference and body weight in subjects with obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(9):1242–1251.

- Friedrichsen M, Breitschaft A, Tadayon S, et al. The effect of semaglutide 2.4 mg once weekly on energy intake, appetite, control of eating, and gastric emptying in adults with obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(3):754–762.

- Gibbons C, Blundell J, Tetens Hoff S, et al. Effects of oral semaglutide on energy intake, food preference, appetite, control of eating and body weight in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(2):581–588.

- Lundgren JR, Janus C, Jensen SBK, et al. Healthy weight loss maintenance with exercise, liraglutide, or both combined. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(18):1719–1730.

- Cava E, Yeat NC, Mittendorfer B. Preserving healthy muscle during weight loss. Adv Nutr. 2017;8(3):511–519.

- Willoughby D, Hewlings S, Kalman D. Body composition changes in weight loss: strategies and supplementation for maintaining lean body mass, a brief review. Nutrients. 2018;10(12):1876.

- Correia de Faria Santarém G, de Cleva R, Santo MA, et al. Correlation between body composition and walking capacity in severe obesity. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130268.

- Hales SB, Schulte EM, Turner TF, et al. Pilot evaluation of a personalized commercial program on weight loss, health outcomes, and quality of life. Transl Behav Med. 2021;11(12):2091–2098.

- Kolotkin RL, Gabriel Smolarz B, Meincke HH, et al. Improvements in health-related quality of life over 3 years with liraglutide 3.0 mg compared with placebo in participants with overweight or obesity. Clin Obes. 2018;8(1):1–10.