ABSTRACT

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a debilitating mental disorder that can be treated with a number of different antidepressant therapies, each with its own unique prescribing considerations. Complicating the selection of an appropriate antidepressant for adults with MDD is the heterogeneity of clinical profiles and depression subtypes. Additionally, patient comorbidities, preferences, and likelihood of adhering to treatment must all be considered when selecting an appropriate therapy. With the majority of prescriptions being written by primary care practitioners, it is appropriate to review the unique characteristics of all available antidepressants, including safety considerations. Prior to initiating antidepressant treatment and when patients do not respond adequately to initial therapy and/or exhibit any hypomanic or manic symptoms, bipolar disorder must be ruled out, and evaluation for psychiatric comorbidities must be considered as well. Patients with an inadequate response may then require a treatment switch to another drug with a different mechanism of action, combination, or augmentation strategy. In this narrative review, we propose that careful selection of the most appropriate antidepressant for adult patients with MDD based on their clinical profile and comorbidities is vital for initial treatment selection.

Strategies must be considered for addressing partial and inadequate responses as well to help patients achieve full remission and sustained functional recovery. This review also highlights data for MDD clinical outcomes for which gaps in the literature have been identified, including the effects of antidepressants on functional outcomes, sleep disturbances, emotional and cognitive blunting, anxiety, and residual symptoms of depression.

Plain Language Summary

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a leading cause of disability worldwide and can affect each patient differently. Antidepressants play a critical role in treatment; however, with multiple antidepressant options available, it is important that providers select the best fit for each patient. Rather than use a “one size fits all” approach, it is important to consider each patient’s symptoms, medical and psychiatric comorbidities, as well as their treatment preferences. A clear summary of each antidepressant’s distinctive characteristics is essential for providers to select antidepressants to best match each patient’s needs.

This narrative review aims to discuss the latest information on available antidepressants, including their risks and benefits and how they impact symptoms of MDD such as sleep disturbances, anxiety, emotional blunting, and changes in cognition, as well as different treatment goals, such as the ability to function in everyday life. This information can guide clinical practice recommendations and further enable shared decision-making between the provider and patient, incorporating individual treatment needs and preferences.

In addition, many patients do not reach their treatment goals with the first antidepressant or may continue to have symptoms of depression after treatment. This review discusses strategies to increase the likelihood of symptom improvement and creates awareness of patient-specific considerations.

Overall, careful, personalized selection of antidepressant treatment is critical for finding the right balance of maximized antidepressant effect with minimized side effects, leading to the best possibility for patients to tolerate the medication and ultimately helping patients reach their treatment goals.

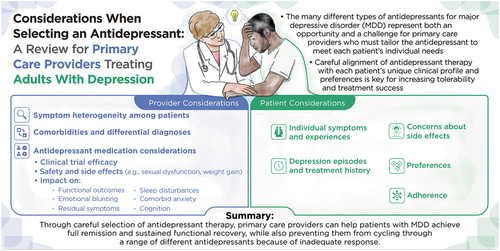

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Depression, or major depressive disorder (MDD), is recognized as an important mental health concern in the United States (US) and global populations. The devastating impact depression has on individuals and society is well documented [Citation1,Citation2]. The 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health reported that an estimated 14.8 million adults in the US had a major depressive episode with severe impairment in the past year. Globally, the 12-month prevalence of MDD is 6%, and the risk of MDD over a lifetime is approximately 11.1%–14.6% [Citation2,Citation3]. With the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators estimate that throughout 2020, the pandemic led to a clinically significant 27.6% increase in cases of depression. The exacerbation of MDD as a global burden highlights an urgent need to strengthen mental healthcare systems, which includes prioritizing promotion of well-being and development of depression mitigation strategies [Citation4]. Optimizing the management of depression in primary care settings represents a critical strategy for addressing the burden of depression, as approximately 60% of mental healthcare is provided in primary care settings and almost 80% of antidepressant prescriptions are written by providers who are not mental health care specialists [Citation5]. This narrative literature review aims to differentiate available antidepressants by presenting a comprehensive examination of their risks and benefits in order to support personalized treatment selection and help patients with MDD reach their treatment goals.

2. Treatment options for adults with MDD

Depression is highly heterogeneous in its clinical presentation and is associated with a constellation of symptoms across a wide range of different emotional, physical, functional, and cognitive domains depending on each individual patient presentation [Citation5–7]. For this reason, a multidisciplinary approach to the management of adult patients with MDD is increasingly considered to provide them with the best chance of achieving remission, often defined as the absence of clinical levels of depressive symptoms, and sustained functional recovery, especially for moderate to severe MDD [Citation8]. This multidisciplinary approach may include pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, a combination of medications and psychotherapy, or other somatic therapies such as electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation or light therapy, and alternative therapies [Citation3,Citation5,Citation8]. Pharmacotherapy for depression has been available for more than 50 years, since the first antidepressants targeting multiple monoaminergic pathways became available in the 1950s, and remains the mainstay of treatment [Citation9]. Nevertheless, a healthy diet and exercise are also important factors in the global treatment of MDD [Citation10,Citation11]. An increase in our understanding of the neurobiology of depression has provided a more complex picture beyond monoaminergic transmission, with MDD now thought to involve a complex interplay of various genes, neural networks, structural neurobiological changes, and neurotransmitters including serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, glutamate, GABA-ergic systems, and histamine at certain brain regions [Citation12–15]. This complexity is further reflected by the different subtypes of depression that can occur, such as anxious depression. Furthermore, psychiatric and medical comorbidities including sleep disorders, anxiety disorders, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obesity and eating disorders, as well as pain and cardiovascular disease are now regarded as important risk factors for the development of depression that can also influence treatment [Citation3,Citation8,Citation13,Citation16]. As our understanding of the neurobiology of depression has advanced, so too has the number of treatments available, with more than 35 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved antidepressant medications [Citation3,Citation17]. This understanding provides both an opportunity and a challenge – an opportunity to tailor treatment to the patient’s specific clinical and pharmacogenomic profile, comorbidities, and preferences, and a challenge, especially in primary care, because clinicians who do not specialize in psychiatry have limited exposure to the nuances of the different compounds and their risk-benefit profiles [Citation12,Citation18].

The abundance of pharmacotherapeutic options for MDD has coincided with a consistent increase in the number of patients being prescribed antidepressants () [Citation19]. As many as 1 in 10 people in the US are currently prescribed an antidepressant, reflecting possible overtreatment of patients with subsyndromal MDD or adjustment disorders; however, only half of patients diagnosed with MDD receive an adequate prescription, suggesting that overprescribing and inadequate prescribing must be addressed [Citation12]. It is possible that the array of antidepressants is not well differentiated and understood by some primary care providers, who frequently contend with time constraints and large caseloads, not to mention the disruption to healthcare delivery in primary care settings caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, physicians in primary care may default to 1 or 2 different antidepressants for all adult patients, thus applying a “one size fits all” approach to a disease with a highly individualized clinical profile. This is consistent with the observation that inadequate responses to initial antidepressants are common, and clear guidance is lacking for primary care providers concerning how partial responses may be addressed [Citation10]. Just as with initial antidepressant selection, the choice of medication in cases of partial response should be guided by the patient’s clinical profile or depression subtype and comorbid conditions. Additionally, some antidepressants are associated with emotional and cognitive blunting, which may add to the burden of illness for patients so affected [Citation20].

Figure 1. Growth in number of patients prescribed antidepressants for MDD: 1996–2015 [Citation19].

![Figure 1. Growth in number of patients prescribed antidepressants for MDD: 1996–2015 [Citation19].](/cms/asset/ac806471-3609-4e1a-acb6-c82c2e176d8a/ipgm_a_2189868_f0001_c.jpg)

3. Addressing literature gaps

There are few review articles aimed at educating a primary care audience about the factors to consider when choosing an antidepressant, as well as about general principle-guided algorithms to follow for treatment initiation or switch. In this article, we review some of the latest data for antidepressants to treat adults with MDD and revisit the latest clinical practice recommendations, highlighting the importance of tailoring treatment to the clinical profile and comorbidities of the patient. Additionally, when emotional blunting is secondary to antidepressant selection, guidelines for diagnosis and strategies for treatment modification must be developed [Citation21,Citation22]. We propose that careful selection of the most appropriate antidepressant for adult patients with MDD is the best way to counter both inadequate prescribing of antidepressants and address partial and inadequate responses to antidepressant therapy. This article also highlights data for MDD clinical outcomes for which gaps in the literature have been identified that may influence response to treatment, including the effects of antidepressants on functional outcomes, sleep disturbances, anxiety, emotional and cognitive blunting, and any residual symptoms of depression.

4. Overview of antidepressant therapies by class

Acute-phase pharmacotherapies for MDD include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists, atypicals, and serotonin modulators that have more complex mechanisms of action and cannot be easily categorized () [Citation8,Citation12,Citation13,Citation23–26]. The efficacy of these treatments compared with placebo has been established in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [Citation12,Citation23–26]. Below we discuss some of the key safety and prescribing considerations for each.

Table 1. Antidepressant profiles by class.

4.1. TCAs and MAOIs

TCAs and MAOIs were the first antidepressants to be introduced following the discovery of their antidepressant properties in the 1950s [Citation27,Citation28]. TCAs act primarily by elevating extracellular serotonin and norepinephrine levels via uptake inhibition [Citation12]. TCAs are prone to anticholinergic side effects (e.g. dry mouth, blurry vision, constipation, urinary retention), which often limit their utility. TCAs can cause significant weight gain and sedation, resulting in relatively high discontinuation rates. They can also block cardiac sodium channels, which in the case of overdose can lead to sudden cardiac death [Citation12]. Once SSRIs and SNRIs became available, there was generally less use of TCAs, but they continue to be of use for patients with comorbid insomnia, pain, and social anxiety disorder, and in severe or resistant MDD with melancholia [Citation8,Citation19].

The broad mechanism of action (MOA) of MAOIs means that they have significant adverse events, such as weight gain, fatigue, and sexual side effects, making them now used almost exclusively in patients who have not responded to other antidepressant classes or those with MDD with atypical features, such as reactive moods or sensitivity to rejection [Citation8,Citation28,Citation29]. Early, nonselective MAOIs had potentially lethal interactions with food, particularly foods rich in tyramine, and with other medications, which can precipitate fatal serotonin syndrome or hypertensive crises [Citation12]. Because of this, MAOIs should not be used in antidepressant augmentation with SSRIs because of a potentially lethal increase in serotonin in the central nervous system (CNS) [Citation29,Citation30]. There is some evidence that the risk and severity of adverse dietary reactions with MAOIs may be less severe than previously thought, especially when proper monitoring by clinicians and adherence by patients are followed [Citation29,Citation31].

4.2. SSRIs and SNRIs

SSRIs are the most widely used antidepressants in contemporary treatment for MDD and include fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram, and escitalopram [Citation8,Citation12,Citation32]. A large body of literature supports the efficacy of SSRIs compared with placebo for the treatment of MDD, and their relative safety has driven a sharp increase in the prescribing of pharmacotherapy for MDD [Citation8,Citation12,Citation32]. Within the class, SSRIs have noteworthy yet nuanced differences in their pharmacologic profiles that may impact their clinical application, of which prescribers should be aware [Citation12]. A slower emergence of the therapeutic effects of fluoxetine compared with other SSRIs is one example. Further, some SSRIs are also specifically approved to treat panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bulimia nervosa, and/or premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Sertraline and paroxetine have several FDA approvals and indications to treat a myriad of psychiatric disorders [Citation12]. All SSRIs may cause nausea, headaches, gastrointestinal (GI) issues, insomnia, fatigue, weight gain, anxiety, dizziness, dry mouth, and sexual side effects and have been associated with increased risk of falls and fractures [Citation8,Citation27,Citation33,Citation34]. Paroxetine eventually may cause more weight gain, and paroxetine and citalopram may be the most sedating. Sertraline may have more adverse GI effects, and paroxetine and fluoxetine have more drug-drug interactions via the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 hepatic enzyme inhibition [Citation12]. SSRIs, particularly citalopram, have the potential to prolong the QT interval, which can lead to torsade de pointes, a rare but potentially fatal arrythmia [Citation32,Citation35]. SSRIs have also been associated with coagulopathy, and use in combination with pain relievers such as aspirin, naproxen, and blood thinners may increase the risk of bleeding [Citation32,Citation36]. In addition, SSRIs may cause the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, with the greatest risk among elderly patients.

SNRIs include venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine (the active metabolite of venlafaxine), duloxetine, milnacipran, and levomilnacipran [Citation37]. Each of these medications is efficacious (superior to placebo in controlled studies and meta-analyses), and venlafaxine (75–150 mg/day) and duloxetine (60 mg/day) showed comparable efficacy in a pair of similarly designed RCTs directly comparing these 2 antidepressants [Citation8,Citation38]. Side effects most common to the class of SNRIs include nausea and vomiting, dizziness, and sweating. Duloxetine and venlafaxine, in particular, may cause sexual dysfunction [Citation33,Citation37]. Other side effects include fatigue, insomnia, and headache [Citation33].

Antidepressants, and in particular SSRIs and SNRIs, are also associated with emotional blunting or indifference [Citation20,Citation22]. This may be underrecognized by both patients and clinicians and poses a challenge for effective treatment because it is frequently a cause for treatment discontinuation [Citation20,Citation22]. Later in this review, we have a dedicated section on treatment strategies for emergent emotional blunting in MDD.

Another issue associated with the use of SSRIs and SNRIs is the emergence of withdrawal symptoms of varying severity following discontinuation or interruption of treatment [Citation33,Citation39]. Symptoms of this so-called “discontinuation syndrome” can include tremors, sweating, tachycardia, agitation, neuralgia, sleep disturbances, vivid dreams, GI symptoms, worsening anxiety, and mood instability [Citation33,Citation39]. Symptoms can be unpredictable and may affect everyone differently, emerging within a few days to weeks and potentially persisting for months or even years [Citation33,Citation39]. In particular, sertraline and paroxetine of the SSRIs, and venlafaxine and its active metabolite, desvenlafaxine, of the SNRIs, have been associated with significant withdrawal symptoms, which may be due to their shorter half-lives [Citation12,Citation33,Citation37,Citation39,Citation40]. Tapering of the treatment over weeks to months may help to mitigate symptoms related to discontinuation of SSRIs and SNRIs [Citation33].

4.3. Atypicals

4.3.1 Mirtazapine: A pooled analysis showed fast onset of antidepressant effect with mirtazapine, and a meta-analysis has confirmed accelerated onset of efficacy of mirtazapine but equal efficacy by week 8 compared with SSRIs (fluoxetine, citalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline) [Citation41]. Mirtazapine has significant sedation properties, tends to promote weight gain and causes dry mouth, but has a low rate of sexual dysfunction [Citation8,Citation12]. The sedative, antiemetic, anxiolytic, and appetite-stimulating effects of mirtazapine suggest that it can also be prescribed off-label for insomnia, panic disorder, PTSD, OCD, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder, headaches, and migraines [Citation42,Citation43]. Mirtazapine will generally be prescribed for MDD after an SSRI, or in depressed adults with comorbid insomnia or those who are underweight [Citation42].

4.3.2 Trazodone: Trazodone was an early second-generation antidepressant whose low side-effect and toxicity profile made it a popular alternative to MAOIs and TCAs in the early 1980s; it is still relatively widely used [Citation8,Citation12]. It is considered a sedating antidepressant, making it suited to patients with comorbid insomnia or GAD [Citation44,Citation45]. A slow-release preparation is available that lowers plasma levels and tends to minimize the sedating side effects relative to the standard formulation [Citation46]. Nefazodone has a structure analogous to trazodone but has different pharmacologic properties. It has largely fallen out of use because of concerns about hepatotoxicity and the need for periodic liver function monitoring [Citation12,Citation44].

4.3.3 Agomelatine: Agomelatine was first marketed in Europe in 2009 and has been available in Australia since 2010 but is not currently available in the United States [Citation47]. Agomelatine has a unique MOA, targeting both melatonergic and serotonergic receptors, with demonstrated superior effects on subjective or objective sleep measures, in addition to being an effective antidepressant [Citation48]. In countries where it is available, it is often recommended for individuals with MDD and sleep disturbances [Citation48]. While agomelatine has been demonstrated to be safe and effective, there is potential for drug interactions mediated via CYP1A2, and it is also associated with liver damage with longer-term use and is contraindicated in patients with impaired liver function [Citation47].

4.3.4 Bupropion: Bupropion was initially approved in the United States in the 1980s as an antidepressant but subsequently removed from the market because of induction of seizures in patients with MDD. It was remarketed after lower doses were noted to be safer [Citation12,Citation49]. A meta-analysis of 7 RCTs demonstrated comparable efficacy between bupropion and the SSRIs fluoxetine, sertraline, and paroxetine [Citation41]. The side-effect profile of bupropion reflects its unique MOA, having no sexual dysfunction or weight gain tendencies [Citation12], yet it is also more activating with regard to insomnia and anxiety, causing agitation, mild cognitive dysfunction, and GI upset, and should be avoided in individuals with comorbid eating disorders because of the increased risk of seizures [Citation8]. It is frequently prescribed as a combination antidepressant, often added to an initially partially effective SSRI [Citation50].

4.4. Serotonin modulators

4.4.1 Vilazodone and vortioxetine: Vilazodone and vortioxetine are more recent entries to the antidepressant space, and each may be considered a “serotonin modulator and stimulator” or multimodal antidepressant [Citation12,Citation51]. Vilazodone appears to have a lower risk of weight gain and sexual side effects than the SSRIs or SNRIs based on noncomparative trials [Citation12,Citation52,Citation53]. Vilazodone should be taken with food to ensure adequate absorption, and a titrated dosing schedule is recommended to minimize GI effects that are frequently observed [Citation48,Citation53].

Vortioxetine has demonstrated suitability for patients with MDD aged 18 to 88 years, including those experiencing treatment-related sexual dysfunction with other antidepressants, and those with deficits in cognitive processing speed [Citation54,Citation55]. GI symptoms, which were dose dependent, were the most common adverse events in clinical trials. Vortioxetine can be taken with or without food [Citation52,Citation55].

4.5. NMDA receptor antagonists

4.5.1 Ketamine and esketamine: The delayed onset of effect seen with most traditional antidepressants has led to great interest in the use of agents with a rapid onset of effect [Citation56]. NMDA receptor antagonists [Citation23], such as ketamine and esketamine, have demonstrated a rapid and robust antidepressant effect in adults with treatment-resistant depression (TRD), defined as lack of response to at least 2 adequate antidepressant treatments from different pharmacological classes [Citation57], with esketamine also approved for MDD with suicidality [Citation23]. However, both ketamine and esketamine carry potential for clinically significant adverse effects, abuse, and misuse, and have limited [Citation23] evidence of long-term efficacy. Patient selection for these agents should involve thorough evaluation of treatment history and other physical and psychological factors [Citation58], and it is recommended that a psychiatrist or other healthcare provider with expertise in the treatment of patients with mood disorders conduct a psychiatric assessment before and after treatment [Citation23]. In addition, clinicians must exercise caution when prescribing, factoring in relevant regulatory requirements, such as the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy drug safety program [Citation23].

4.5.2 Dextromethorphan-bupropion: Similar to ketamine, dextromethorphan is an NMDA receptor antagonist with multimodal activity [Citation56]; however, its clinical use has been limited by the difficulty in achieving therapeutic plasma levels due to its rapid metabolism via cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) [Citation56]. An oral tablet combining dextromethorphan with bupropion, a known antidepressant and inhibitor of CYP2D6 that increases the bioavailability and half-life of dextromethorphan and leads to sustained therapeutic concentrations [Citation24,Citation56], has shown promising results in a 6-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study [Citation24]; significant improvements in depressive symptoms compared to placebo were demonstrated as early as 1 week after treatment initiation [Citation24]. Notably, dextromethorphan-bupropion was not associated with psychomimetic effects. The FDA granted approval for its use in MDD in August 2022 [Citation59]; however, additional data investigating long-term efficacy and safety will help define its role in the MDD treatment landscape [Citation60].

5. Assessment of suicide risk in patients starting antidepressant therapy

When initiating patients on antidepressant therapy, suicide risk must be monitored, as some antidepressants have been associated with an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, particularly in children, adolescents, and young adults [Citation48,Citation61,Citation62]. In 2004, the FDA directed manufacturers of all antidepressants to revise their labeling as the result of an increase in suicidality among children and adolescents being treated with antidepressants. This warning was based on a combined analysis of 24 short-term (up to 4 months), placebo-controlled trials of 9 antidepressant drugs among more than 4400 children and adolescents with MDD or other psychiatric disorders. A greater risk of suicide during the first few months of treatment was observed in patients receiving antidepressants (4% vs. 2% in patients receiving placebo) [Citation62]. In 2007, the FDA revised the warning, changing the target period from childhood and adolescence to young adulthood (aged 18–24 years) during initial treatment [Citation62]. However, clinicians should continue to monitor for suicidality in all patients being treated for depression with or without antidepressant medication.

6. Selecting pharmacotherapy for the treatment of MDD: what do the guidelines say? Factors to consider when initiating antidepressant treatment in primary care settings

6.1. Efficacy

Given that depression is a heterogeneous illness with multiple clinical presentations, antidepressant selection should be based on patient profile and tolerability, especially considering any comorbidities (for example, ADHD) [Citation12,Citation63]. Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of MDD generally emphasize the importance of tailoring the selected therapy to the patient based on their clinical profile and individual preferences () [Citation3,Citation8,Citation48]. For example, the 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZP) clinical practice guidelines for major depression note that there is a modest hierarchy with respect to efficacy of antidepressants. These guidelines state that, generally, the medications with a broader spectrum of action, such as TCAs, appear to be more clinically efficacious than those that are more selective [Citation3]. Although TCAs and MAOIs may exert effectiveness in treating depression, their safety profiles are of significant concern [Citation12]. Hence, more selective may mean less effective in some patients. However, the 2010 American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder states that the effectiveness of antidepressants is generally comparable between and within classes of medications [Citation8]. The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Adults With Major Depressive Disorder provide evidence of superiority of some antidepressants over others. However, they also emphasize the importance of tailoring pharmacologic treatment to the patient’s symptoms and preferences, similarly stressing that there are no absolutes [Citation48].

Figure 2. Treating MDD in primary care: factors influencing initial antidepressant selection [Citation3,Citation8,Citation84].

![Figure 2. Treating MDD in primary care: factors influencing initial antidepressant selection [Citation3,Citation8,Citation84].](/cms/asset/898e4938-826f-446b-ad81-e02b5e4fb2a6/ipgm_a_2189868_f0002_c.jpg)

Figure 3. Summary algorithm for selecting an antidepressant [Citation3,Citation8,Citation48,Citation88].

![Figure 3. Summary algorithm for selecting an antidepressant [Citation3,Citation8,Citation48,Citation88].](/cms/asset/66c24f7e-d0e5-49cf-9597-3774415bcd10/ipgm_a_2189868_f0003_c.jpg)

A comprehensive and relatively recent network meta-analysis by Cipriani et al. consisting of 522 clinical trials and 116,477 participants with acute MDD reported that in head-to-head studies, agomelatine, amitriptyline, escitalopram, mirtazapine, paroxetine, venlafaxine, and vortioxetine were more effective than other antidepressants, whereas fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, reboxetine, and trazodone were the least efficacious drugs [Citation64]. For acceptability (defined as treatment discontinuations due to any cause), agomelatine, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, and vortioxetine were more tolerable than other antidepressants, whereas amitriptyline, clomipramine, duloxetine, fluvoxamine, reboxetine, trazodone, and venlafaxine had the highest dropout rates [Citation64]. The authors noted that the results should inform guideline and policy developers on the relative merits of the different antidepressants available [Citation64]. Until there is consensus regarding the superiority of one class of antidepressant over another, initial selection of an antidepressant will be based largely on cost, patient preference and previous responses, anticipated side effects, nuances of patient’s clinical profile including comorbidities, and their specific and most severe/dominant symptoms () [Citation3,Citation8]. Additionally, pharmacologic properties of the medication (e.g. half-life, actions on CYP enzymes, other drug interactions) must be considered [Citation49].

7. Patient clinical profile and comorbidities

It is logical that an initial antidepressant is selected based on the most prominent/severe depressive symptoms experienced by the patient (e.g. suicide risk, sleep disturbances, cognitive disturbances, anxiety, somatic symptoms, or atypical features such as oversleeping and overeating) [Citation28,Citation48]. Clinical practice guidelines address the different depression subtypes that can be an important modifier of antidepressant efficacy, such as depression with melancholic features (psychomotor slowing, diurnal mood variation), depression with anxious distress, or depression with psychotic or catatonic features [Citation3,Citation48]. The Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Depressive Disorder provides first- and second-line recommendations for nonpsychotic depression, psychotic depression, and specific depression subtypes [Citation62]. Other patient-related factors, such as cost, age, level of sexual activity, comorbid conditions, preferences, use of concomitant medications, response to prior antidepressants, and pregnancy status, all become necessary considerations as well [Citation8,Citation48]. In addition, pharmacogenetic testing can sometimes guide providers in choosing potential pharmacotherapy, and patients may qualify for enrollment in clinical trials, as multiple neurotransmitter and receptor targets are currently under investigation and may help guide and improve patient outcomes, including time to response and complete remission of depression [Citation65,Citation66].

8. Tolerability and adherence

The 2010 APA guideline states that ”the optimal regimen is the one that the patient prefers and will adhere to [Citation8].” Tolerability and patient preference therefore become critical because they relate directly to medication adherence, which has implications for response and remission, and antidepressants differ in their potential to cause certain side effects (as described in the previous section and ) [Citation8,Citation67]. Indeed, an important part of patient satisfaction with MDD treatment comes from adequately addressing concerns about side effects such as weight gain and sexual dysfunction. In a study of 180 patients receiving treatment for MDD, key concerns expressed by patients included weight gain, withdrawal effects, and sexual dysfunction [Citation68]. However, other side effects commonly associated with antidepressants, of which patients may be less aware, include hypertensive crises, serotonin syndrome, and cardiovascular and neurological effects, all of which are important for the prescriber to consider [Citation8]. Other factors that can influence adherence include the patient’s clinical profile, sociocultural background, financial factors, and beliefs regarding the effectiveness of the treatment. This is where physician expertise and a strong doctor-patient relationship become vital [Citation67].

9. Patient preference and shared decision-making

From the perspective of the primary care provider, physician expertise can help guide the patient to select the antidepressant that suits their preferences while also being best suited to their clinical profile [Citation3]. The concept of the “therapeutic alliance” between the patient and provider is important in primary care settings, with the aim being to establish an effective partnership, taking into consideration the patient’s preferences and ensuring that they adhere to treatment and do not discontinue due to issues with tolerability without first speaking with their provider. This gives patients the greatest chance of achieving response, remission, and sustained functional recovery while on therapy [Citation8]. Measurement-guided care, which uses validated screening and monitoring tools, is encouraged for use by clinicians to quantify the presence and severity of depressive symptoms and track improvements in functional outcomes and adverse events following initiation of an antidepressant. The incorporation of measurement-guided care increases the likelihood of remission, treatment adherence, and sustained functional recovery [Citation8,Citation69].

10. Guideline recommendations for antidepressants

There is considerable variability among clinical practice guidelines. The 2010 APA guideline describes the different classes of antidepressants but does not make prescriptive recommendations concerning their selection [Citation8]. The 2016 CANMAT guidelines list SSRIs, SNRIs, agomelatine, bupropion, mirtazapine, and vortioxetine as first-line recommendations [Citation48]. Second-line recommendations include TCAs, quetiapine, and trazodone (owing to higher side-effect burden); moclobemide and selegiline (potential serious drug interactions); levomilnacipran (lack of comparative and relapse-prevention data); and vilazodone (lack of comparative and relapse-prevention data and the need to titrate and take with food) [Citation48]. Third-line recommendations include MAOIs (owing to higher side-effect burden and potential serious drug and dietary interactions) and reboxetine (lower efficacy) [Citation48]. The 2020 RANZP guidelines for major depression list 7 molecules with different MOAs that they recommend as “Choice” antidepressants, which is a unique approach to treatment recommendations (escitalopram, vortioxetine, agomelatine, venlafaxine, mirtazapine, bupropion, amitriptyline) [Citation3]. The RANZP guidelines also provide guidance on selecting these molecules according to the patient’s clinical profile and to minimize side effects [Citation3]. While many if not all recommendations provided by the guidelines discussed may continue to be applicable, updates are needed, particularly for inclusion of newer agents such as NMDA receptor antagonists.

11. Partial or inadequate response to initial antidepressant

Regardless of the intervention used, a substantial proportion of patients do not adequately respond or achieve remission after initial treatment. For example, about 40% of patients treated with second-generation antidepressants do not respond, and approximately 70% do not achieve remission [Citation10]. Partial or inadequate response is important to address because a lack of early improvement in symptoms (defined in RCTs as a 20%–30% reduction from baseline in a depression rating scale after 2–4 weeks) is a predictor of later antidepressant nonresponse/nonremission. However, there is only low-quality evidence to support early switching at 2 or 4 weeks for nonresponders to an initial antidepressant [Citation48]. Inadequate responses to antidepressants can also prompt nonadherence, which can be an important driver of poor response to an antidepressant therapy [Citation3,Citation67]. In primary care settings where defining partial or inadequate response may be ambiguous, measurement-guided care using time-efficient patient- and clinician-completed rating scales may help with patient monitoring following initiation of an antidepressant (). This can assist both the patient and provider in tracking and clinical management of symptoms and functioning over time, identifying factors influencing inadequate response, and understanding if treatment adjustments are needed [Citation8,Citation69].

11.1. Increasing the dose/duration of antidepressants

Almost all approved antidepressants have an initial dose that can be incrementally increased depending on the patient’s response and tolerability [Citation8]. Partial responses to antidepressants can be addressed by first increasing the dosage at 2 to 4 weeks if tolerated [Citation3,Citation48]. In addition, the 2010 APA guideline suggests doing this after 4–8 weeks of treatment and provides guidance for the starting dose of the different classes of antidepressants and the usual daily dosage, which should be increased incrementally [Citation8]. Prescribing information for each antidepressant can also be consulted for the most up-to-date dosing information.

11.2. Assessing treatment adherence and reevaluating diagnosis: bipolar disorder (BPD) and comorbid ADHD as examples

Unipolar depression is a diagnosis of exclusion, as bipolar depression, or BPD, must first be ruled out. Often the first presentation of BPD is a major depressive episode (MDE), which may be indistinguishable from that of unipolar depression [Citation70]. Up to 25% of patients presenting with an MDE may in fact have BPD [Citation71]. Screening tools are available for evaluation of BPD in primary care, such as the Rapid Mood Screener, a validated scale, and the Mood Disorder Questionnaire; both are time-sensitive and extremely helpful for ruling out BPD [Citation70]. It is also important to rule out BPD because there is evidence suggesting that antidepressant monotherapy in individuals with BPD can induce states of hypomania, mood destabilization, and potential increase in suicidality [Citation72,Citation73]. The consensus is that individuals diagnosed with BPD should not be treated with antidepressant monotherapy as a first-line strategy, as mood stabilizers and second-generation antipsychotics are considered to be more appropriate and are less likely to cause mood cycling [Citation72,Citation74]. Once BPD is excluded, the APA guideline suggests that if at least moderate improvement in symptoms of unipolar depression is not observed within 4–8 weeks of treatment initiation, the diagnosis should be reassessed. Antidepressant side effects should be taken into consideration, complicating co-occurring conditions and psychosocial factors reviewed, and the treatment plan adjusted accordingly [Citation8,Citation75,Citation76]. Other factors to consider include pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic influences on efficacy, as blood levels of antidepressants can help determine if dosage adjustments are needed [Citation8]. Treatment adherence should also be evaluated [Citation8], as there is evidence that up to 20% of patients may have poor adherence [Citation48]. This should be done before moving on to a different antidepressant.

ADHD is frequently comorbid with both BPD and MDD, and a mean prevalence of 7.8% of comorbid ADHD in individuals with depression has been reported, complicating identification and management of each disorder [Citation16,Citation63,Citation77]. Depressive symptoms in adults with ADHD may manifest as a result of coping with lower hedonic tone, and in one study, up to 28% of individuals referred to a tertiary clinic for mood and anxiety disorders had undetected ADHD [Citation16,Citation78]. Symptoms of ADHD may also be masked by substance use disorder, as individuals with ADHD have double the risk of substance abuse and dependence compared with the general population [Citation79]. Symptoms of ADHD respond best to catecholaminergic agents such as psychostimulants or norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors such as bupropion, which has shown potential off-label use for treatment of ADHD [Citation80]. In addition, viloxazine, an SNRI previously used for treatment of MDD in Europe, was recently approved by the FDA for treatment of ADHD and has shown promise as a nonstimulant option [Citation27,Citation81,Citation82]. Serotonergic agents alone do not improve symptoms of ADHD; thus, initiation of treatment with an SSRI alone for MDD in an individual with comorbid ADHD is likely to yield unsatisfactory response to treatment for either MDD or ADHD [Citation16].

In primary care settings where depressive symptoms may be more frequently reported by adults and therefore more easily diagnosed, clinicians may benefit from asking adult patients presenting with depressive symptoms questions about previous diagnosis or family history of ADHD, or whether they had difficulty in school. This may help to identify comorbid ADHD in their patients [Citation77].

11.3. Combination, switching, and augmentation strategies

In clinical practice guidelines, there is no consistent evidence supporting switching within or between antidepressant classes. Switching within a class has been noted as acceptable if the antidepressant was not taken as prescribed because of poor adherence or side effects; however, there is limited guidance on how to switch to a different antidepressant in the same class [Citation3,Citation48]. There are few RCTs comparing a switch strategy to continuing the same antidepressant, and thus the value of switching between or within classes remains controversial [Citation48]. One theory regarding why patients often respond suboptimally to their initial antidepressant is that receptor tolerance to drug action precipitates antidepressant nonresponse, so treatment switching to a different class could be considered a reasonable strategy [Citation83]. There is limited information about which treatments may be best suited as second-line therapies in patients who have not achieved an adequate response with their initial antidepressant, but the selection of the subsequent therapy should account for the class/MOA and response to initial antidepressant [Citation84].

Combination and augmentation strategies are additional approaches to consider if the patient continues to have a partial or inadequate response at the maximally tolerated dose of initial therapy after an adequate duration of treatment [Citation3,Citation62,Citation76]. The combination of 2 antidepressants with different MOAs may have synergistic effects that enhance response in inadequate responders, and there is some evidence supporting the addition of bupropion to an SSRI [Citation8,Citation76]. Further, prescribers must be aware of the risk for serotonin syndrome when combining antidepressants.

Augmentation typically involves the addition of a non-antidepressant to a current antidepressant. As we have mentioned, multiple comorbidities can drive the patient to experience symptoms of depression, which must be kept in mind when approaching augmentation and combination strategies. Augmentation with lithium and atypical antipsychotics (e.g. aripiprazole, cariprazine [Citation85], brexpiprazole, risperidone, quetiapine, or olanzapine) may be appropriate strategies to consider for non- or partial responders who may have mixed features, TRD, or BPD, for example [Citation3,Citation8,Citation48]. For adults with MDD who have comorbid ADHD, most antidepressants can be combined (with monitoring) with long- or short-acting stimulants to treat ADHD symptoms [Citation16,Citation63,Citation77,Citation79]. Long-acting preparations are preferred when using psychostimulants.

12. Antidepressant therapy for MDD: filling the literature gaps

There is heightened awareness of the ability of antidepressants to aid patients with MDD struggling to achieve full functional recovery, as well as of the impact of comorbid symptoms such as distractibility, sleep disturbance/apnea, emotional blunting, and anxiety. This section aims to highlight recently published data on antidepressant effectiveness for these specific issues where literature gaps have been identified. We conducted a search of articles in English from 2013 to the present pertaining to use of antidepressants for functional recovery, and comorbid symptoms such as sleep disturbances, emotional blunting, and anxiety. Data continue to emerge on a range of antidepressants that may be prescribed to address these specific challenges in individuals with MDD, and longer-term and real-world studies are providing insights into which antidepressants may be best suited for patients experiencing specific symptoms. Of note is that distinguishing symptoms such as sleep disturbances or emotional blunting with antidepressant therapy from residual symptoms of MDD remain a challenge.

12.1. Antidepressant therapy, cognitive dysfunction, and functional outcomes

In 2015, CANMAT published recommendations for assessment of functional outcomes in individuals with MDD, which highlighted the critical impact of depressive symptoms on social, occupational, and physical functioning [Citation48,Citation86]. Functional status relates to an individual’s ability to “perform the tasks of daily life and to engage in mutual relationships with other people in ways that are gratifying and that meet the needs of the individual and the community in which they live” [Citation86]. The CANMAT guidelines emphasized that recovery from depression must involve both relief of symptoms and improvement of functioning, but systematic reviews show that functional outcomes are only modestly correlated with symptom outcomes, and functional improvement may lag behind symptom improvement, which is prioritized as an outcome in the majority of RCTs [Citation48,Citation86,Citation87].

Symptoms of cognitive impairment may have a particularly adverse effect on functional outcomes and have been linked to psychosocial dysfunction, patient employment status, and ability to functionally recover [Citation88–91]. Further, antidepressants that are best suited to treat cognitive symptoms may lead to improvements in functional outcomes for patients, but there are few studies that address this subject. PERFORM-J, a 6-month, noninterventional, prospective, longitudinal study, investigated the relationship among cognitive disturbances, severity of depressive symptoms, and social functioning in patients with MDD in Japan. Notably, improvement of depressive symptoms in the early stages of antidepressant treatment was associated with a reduced risk of residual cognitive symptoms after 6 months in patients with MDD, highlighting the importance of early improvements in depressive symptoms for long-term remission and the need for early and aggressive monitoring and treatment modifications with measurement-guided care [Citation91,Citation92]. Also, residual cognitive disturbances have been demonstrated in individuals with MDD even after achieving remission from mood symptoms, which can have an impact on long-term outcomes including remission, relapse, and social functioning [Citation92]. In a 3-year follow-up study, approximately 44% of individuals with MDD who reported partial/full remission with treatment continued to experience impairments in cognitive function despite the resolution of their depressed mood [Citation90]. The precise mechanisms for the lasting cognitive impairment, even in remitters from mood symptoms, are unclear, but it is possible that neurobiological insults due to recurring depressive episodes may be responsible (some patients with MDD show atrophy of the hippocampus, which may be associated with lingering cognitive symptoms) [Citation92].

Baune and colleagues conducted a systematic review of 35 studies evaluating pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments of cognitive impairment primarily in the domains of memory, attention, processing speed, and executive function in clinical depression [Citation89]. The results showed that various classes of antidepressants exert improving effects on cognitive function across several cognitive domains. Specifically, SSRIs, the selective serotonin reuptake enhancer tianeptine, the SNRI duloxetine, vortioxetine, and other antidepressants such as bupropion and moclobemide may exert specific positive effects on cognitive function in depression, such as learning, memory, and executive function [Citation89]. In addition to their positive effects on cognitive function, sertraline, citalopram, and nortriptyline or paroxetine improved overall psychosocial functioning, and duloxetine improved overall social functioning and enjoyment of life, which may be due in part to its pain-alleviating effect [Citation89]. Further, in a separate analysis, Pan and colleagues note that while most antidepressants exert procognitive effects, vortioxetine and duloxetine are the only antidepressants that have established these effects when a rigorous methodology is used [Citation90].

A recent publication reported on the real-world effectiveness of vortioxetine for functional outcomes in patients with MDD. In this 24-week observational study of outpatients initiating MDD treatment with vortioxetine, the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) was used as the main outcome measure to evaluate patient functioning. Significant improvements in functioning were observed, and the proportion of patients with severe functional impairment decreased substantially [Citation93]. Sustained improvements in functioning were seen over the 24 weeks of treatment irrespective of vortioxetine treatment line [Citation93].

In one of the few studies directly assessing antidepressant effects on functional outcomes, a meta-analysis of 17 RCTs exploring occupational (workplace) impairment in MDD reported a small positive effect versus placebo of duloxetine, desvenlafaxine, venlafaxine, paroxetine, escitalopram, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine on occupational impairment in the short term as measured by the SDS-work subscale. However, the authors questioned the overall clinical significance of the findings due to a small effect size [Citation87]. While the ability of antidepressants to exert positive effects on cognition is relatively well studied, more large-scale, longer-term studies that directly assess their impact on functional outcomes are needed to be able to provide more robust treatment recommendations for one antidepressant over another [Citation48,Citation87,Citation89]. From a primary care perspective, sustained functional recovery in patients with MDD should be considered an important treatment goal [Citation91], and providers should maintain a partnership with their patients to monitor functional outcomes with antidepressant therapy over time.

12.2. Antidepressant therapy and sleep disturbances

Sleep disturbance is a prominent symptom in patients with MDD, and depressed patients with sleep disturbance are more likely to present with more severe symptoms and difficulties with treatment [Citation94,Citation95]. Insomnia is a predisposing factor for the development of new or recurring depression in young and older adults [Citation94]. Persistent insomnia is the most common residual symptom in depressed patients, is considered a vital predictor of depression relapse, and may contribute to adverse clinical outcomes [Citation94]. There are several different proposed mechanisms involved in sleep disturbances and MDD; most notably for patients with MDD, there may be a disruption to circadian rhythm, specifically rapid eye movement (REM) sleep disturbances and dysfunction of the monoaminergic and cholinergic systems [Citation94,Citation95]. Improving sleep outcomes in patients with MDD should be prioritized in primary care; however, some antidepressants can worsen sleep quality due to their role in modulating levels of neurotransmitters involved in the sleep-wake cycle. These include the SNRIs, MAOIs, SNRIs, SSRIs, and TCAs [Citation94,Citation96]. Polysomnography studies have reported that SSRIs, SNRIs, and activating TCAs increase REM sleep latency, suppress REM sleep, and impair sleep continuity. Sedating antidepressants, such as mirtazapine and trazodone, decrease sleep latency, ameliorate sleep efficiency, and increase slow-wave sleep, with little effect on REM sleep. In this regard, sedating antidepressants are favorable for patients with comorbid depression and sleep disturbance [Citation94]. In a meta-analysis of 276 RCTs exploring insomnia and somnolence associated with second-generation antidepressants, 10 of 14 antidepressants showed significantly higher rates of insomnia than placebo, with the following increasing order of incidence: escitalopram, duloxetine, venlafaxine, paroxetine, reboxetine, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, desvenlafaxine, and bupropion. Agomelatine was the only antidepressant that had a lower likelihood of inducing insomnia than placebo. Mirtazapine, milnacipran, and citalopram did not differ from placebo in terms of insomnia rates [Citation96].

12.3. Emotional blunting

Limited evidence-based information exists on how emotional blunting, or “numbness” of both positive and negative emotions caused by antidepressant therapy, may be addressed in individuals with MDD [Citation22]. Patients with MDD who suffer from emotional blunting are subject to a reduction in a broader range of emotions, including love, affection, fear, and anger, which is distinct from anhedonia and apathy, and may lead to reduced quality of life or reduced social responsibilities [Citation22]. Emotional blunting is frequently reported by patients receiving antidepressant treatment for MDD, particularly SSRIs, and is considered to be one of the most prominent side effects leading to treatment discontinuation [Citation21,Citation22,Citation97]. Approximately 40%–60% of patients who suffered from MDD and were treated with either SSRIs, SNRIs, and TCAs experienced some degree of emotional blunting [Citation97,Citation98]. Some studies suggest that emotional blunting is not simply a side effect of antidepressants, but also a residual symptom of depression due to incomplete treatment, adding further complexity to understanding how it may be mitigated by appropriate treatment selection [Citation22,Citation98].

Studies aimed at understanding the etiology of antidepressant-induced emotional blunting have generally focused on SSRIs and a possible modulating effect on frontal lobe activity via serotonergic signaling [Citation22]. Other studies hypothesize a mutually opposed relationship between serotonergic and dopaminergic systems, which may have inhibitory effects on rewarding and aversive stimuli [Citation22,Citation99]. Emotional blunting with antidepressants appears to be dose related, with several case studies noting a reduction in emotional blunting with an incremental tapering of the dose of SSRI. Thus, from a clinical perspective, dose reduction of SSRIs or other antidepressant is a promising strategy if clinically feasible [Citation22]. If there is any question as to whether emotional blunting is still of concern, the Oxford Depression Questionnaire should be administered [Citation100]. Another strategy is to switch to a different class of antidepressant [Citation22]. In more recent studies, emotional blunting has been found to be less frequent in patients taking agomelatine than in those taking escitalopram (an SSRI), and less severe when medication was switched from SSRIs/SNRIs to vortioxetine [Citation101,Citation102]. Augmentation may also be considered; however, the evidence for this as an effective strategy to address emotional blunting is less robust [Citation22].

12.4. MDD and comorbid anxiety

Few dedicated trials have been conducted in patients with anxious depression, as MDD with comorbid GAD has not yet been recognized as a distinct disorder. Consequently, specific treatment guidelines and recommendations are lacking [Citation103]. Fortunately, there is considerable therapeutic overlap between agents used to treat both anxiety and depression, with many pharmacotherapies demonstrating efficacy for both disorders [Citation103]. Treatment selection for patients with MDD and comorbid anxiety should therefore focus on antidepressants that also demonstrate efficacy for anxiety, or vice versa, such as the SSRIs, SNRIs, and serotonin modulators (e.g. vortioxetine and vilazodone). Goodwin provides recommendations for treatment options for MDD and GAD that include off-label use of TCAs, agomelatine, vortioxetine, and bupropion [Citation103].

In a meta-analysis of 3 RCTs, vilazodone was found to be superior to placebo in the short-term treatment of GAD [Citation104]. However, a later meta-analysis demonstrated poor tolerability, highlighting the need for additional studies to confirm overall benefit [Citation105]. Recently published data from an 8-week, open-label study of vortioxetine in 100 adult patients with severe MDD and comorbid severe GAD demonstrated clinically meaningful and statistically significant improvements in patient- and clinician-assessed symptoms of depression and anxiety. In the trial, vortioxetine was administered as a first-line therapy or in patients switching to vortioxetine due to inadequate response to another antidepressant [Citation106]. Significant improvements in overall functioning and health-related quality of life were also noted [Citation106]. In the trial, treatment with vortioxetine was initiated at 10 mg/day and titrated up to 20 mg/day after one week, with dose reductions permitted based on individual tolerability [Citation106].

Conclusions

The multitude of different types of antidepressants for MDD represents both an opportunity and a challenge for primary care providers who must tailor the antidepressant to their patient. Practitioners prescribing antidepressants in primary care can achieve better outcomes for their patients and help prevent them from cycling through a range of different antidepressants with inadequate response through careful selection of an initial antidepressant therapy. An initial therapy that fits the patient’s clinical profile and comorbidities is most likely to be successful and tolerated. Providers need to not only focus on relieving the symptoms related to MDD, but also focus on improving functional outcomes for their patients. Prioritizing the management of residual symptoms that can adversely impact response, remission, and precipitate reoccurrence will help provide the patient with the best chance of symptomatic and functional remission.

List of Abbreviations

Declaration of interest

C. Brendan Montano has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Arbor, Eisai, Neos, Novo Nordisk, Otsuka, Sunovion, Supernus, and Takeda, and has also received payment/honoraria from AbbVie, Arbor, Eisai, Otsuka, and Takeda. W. Clay Jackson has received consulting fees and payment/honoraria from AbbVie, Alkermes, Genentech, Otsuka, and Sunovion; has received honoraria from AbbVie, Alkermes, Genentech, Otsuka, and Sunovion for attending meetings and/or travel; and has participated on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for AbbVie, Alkermes, Genentech, Otsuka, and Sunovion. Denise Vanacore has received payment/honoraria from AbbVie. Richard Weisler has received grants or contracts from Allergan, Alkermes, Astellas, Axsome Therapeutics, Ironshore, Janssen, Lundbeck, Major League Baseball, Neos Therapeutics, Otsuka America Pharmaceuticals, Sirtsei Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, and Validus. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed receiving manuscript or speaker’s fees from Astellas, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Elsevier Japan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Yakuhin, Lundbeck Japan, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Shire, Sumitomo Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tsumura, Viatris, Wiley Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin; and research grants from Eisai, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Shionogi and Sumitomo Pharma. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Under the direction of the authors, medical writing assistance was provided by Katherine Price, PhD, and Leandra Dang, PharmD, on behalf of Syneos Health Medical Communications, LLC. Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc., and H. Lundbeck A/S provided funding to Syneos Health for support in writing this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Villarroel MA, Terlizzi EP. Symptoms of depression among adults: united States. NCHS Data Brief. 2019;2020(379):1–8.

- Delphin-Rittmon ME. In: SAMHSA: key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2020 national survey on drug use and health [Internet]. Jul 2020. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Available fromhttps://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/slides-2020-nsduh/2020NSDUHNationalSlides072522.pdf

- Malhi GS, Bell E, Singh AB, et al. The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders: major depression summary. Bipolar Disord. 2020;22(8):788–804.

- Sakai C, Tsuji T, Nakai T, et al. Change in antidepressant use after initiation of ADHD medication in Japanese adults with comorbid depression: a real-world database analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:3097–3108.

- Park LT, Zarate CA Jr. Depression in the primary care setting. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(6):559–568.

- Ferenchick EK, Ramanuj P, Pincus HA. Depression in primary care: part 1—screening and diagnosis. BMJ. 2019;365:l794.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, et al. In: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder[Internet] 3rd. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2010. Available fromhttp://www.psychiatryonline.com/pracGuide/pracGuideTopic_7.aspx

- Ban TA. The role of serendipity in drug discovery. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(3):335–344.

- Gartlehner G, Gaynes BN, Amick HR, et al. Comparative benefits and harms of antidepressant, psychological, complementary, and exercise treatments for major depression: an evidence report for a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(5):331–341.

- Ljungberg T, Bondza E, Lethin C. Evidence of the importance of dietary habits regarding depressive symptoms and depression. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1616.

- Santarsieri D, Schwartz TL. Antidepressant efficacy and side-effect burden: a quick guide for clinicians. Drugs Context. 2015;4:212290.

- Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Phillips ML. Major depressive disorder: new clinical, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1045–1055.

- aan het Rot M, Mathew SJ, Charney DS. Neurobiological mechanisms in major depressive disorder. CMAJ. 2009;180(3):305–313.

- Yamada Y, Yoshikawa T, Naganuma F, et al. Chronic brain histamine depletion in adult mice induced depression-like behaviours and impaired sleep-wake cycle. Neuropharmacology. 2020;175:108179.

- Katzman MA, Bilkey TS, Chokka PR, et al. Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):302.

- FDA. In: Depression medicines [Internet]. September 2019. Silver Spring (MD): Food and Drug Administration. Available fromhttps://www.fda.gov/media/132665/download

- Papakostas GI, Jackson WC, Rafeyan R, et al. Overcoming challenges to treat inadequate response in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81:3.

- Luo Y, Kataoka Y, Ostinelli EG, et al. National prescription patterns of antidepressants in the treatment of adults with major depression in the US between 1996 and 2015: a population representative survey based analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:35.

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA. SSRI-induced indifference. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(10):14–18.

- Rosenblat JD, Simon GE, Sachs GS, et al. Treatment effectiveness and tolerability outcomes that are most important to individuals with bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:116–120.

- Ma H, Cai M, Wang H. Emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder: a brief non-systematic review of current research. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:792960.

- McIntyre RS, Rosenblat JD, Nemeroff CB, et al. Synthesizing the evidence for ketamine and esketamine in treatment-resistant depression: an international expert opinion on the available evidence and implementation. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(5):385–399.

- Iosifescu DV, Jones A, O’Gorman C, et al. Efficacy and safety of AXS-05 (dextromethorphan-bupropion) in patients with major depressive disorder: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial (GEMINI). J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83(4):21m14345.

- Kryst J, Kawalec P, Mitoraj AM, et al. Efficacy of single and repeated administration of ketamine in unipolar and bipolar depression: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Pharmacol Rep. 2020;72(3):543–562.

- Ng J, Rosenblat JD, Lui LMW, et al. Efficacy of ketamine and esketamine on functional outcomes in treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2021;293:285–294.

- Richards JB, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, et al. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on the risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(2):188–194.

- Kang S, Han M, Park CI, et al. Use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of subsequent bone loss in a nationwide population-based cohort study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13461.

- Faquih AE, Memon RI, Hafeez H, et al. A review of novel antidepressants: a guide for clinicians. Cureus. 2019;11(3):e4185.

- De Bodinat C, Guardiola-Lemaitre B, Mocaer E, et al. Agomelatine, the first melatonergic antidepressant: discovery, characterization and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(8):628–642.

- Rosenbaum SB, Gupta V, Patel P, et al. Ketamine. Updated 2022 Nov 24. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470357/

- Salahudeen M, Wright CM, Peterson GM. Esketamine: new hope for the treatment of treatment-resistant depression? A narrative review. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2020;11:1–23.

- Cosci F, Chouinard G. The monoamine hypothesis of depression revisited: could it mechanistically novel antidepressant strategies? In: Quevedo J, Carvalho AF, Zarate CA, eds. Neurobiology of Depression: Road to Novel Therapeutics. London: Academic Press. 2019. 63–73.

- Sub Laban T, Saadabadi A. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Suchting R, Tirumalajaru V, Gareeb R, et al. Revisiting monoamine oxidase inhibitors for the treatment of depressive disorders: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:1153–1160.

- Bodkin JA, Dunlop BW. Moving on with monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2021;19(1):50–52.

- Grady MM, Stahl SM. Practical guide for prescribing MAOIs: debunking myths and removing barriers. CNS Spectr. 2012;17(1):2–10.

- Chu A, Wadhwa R. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Carvalho AF, Sharma MS, Brunoni AR, et al. The safety, tolerability and risks associated with the use of newer generation antidepressant drugs: a critical review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85(5):270–288.

- Warden SJ, Fuchs RK. Do selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) cause fractures? Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2016;14(5):211–218.

- FDA. In: FDA Drug Safety Communication: revised recommendations for Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide) related to a potential risk of abnormal heart rhythms with high doses [Internet]. updated 2012 Mar 28. Silver Spring (MD): Food and Drug Administration. Available fromhttps://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-revised-recommendations-celexa-citalopram-hydrobromide-related

- Yuet WC, Derasari D, Sivoravong J, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and risk of gastrointestinal and intracranial bleeding. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119(2):102–111.

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors: a pharmacological comparison. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2014;11(3–4):37–42.

- Perahia DG, Pritchett YL, Kajdasz DK, et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of duloxetine and venlafaxine in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(1):22–34.

- Fava GA, Benasi G, Lucente M, et al. Withdrawal symptoms after serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2018;87(4):195–203.

- Cosci F, Chouinard G. Acute and persistent withdrawal syndromes following discontinuation of psychotropic medications. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89(5):283–306.

- Thase ME, Nierenberg AA, Vrijland P, et al. Remission with mirtazapine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 15 controlled trials of acute phase treatment of major depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(4):189–198.

- Jilani TN, Gibbons JR, Faizy RM, et al. Mirtazapine. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Croom KF, Perry CM, Plosker GL. Mirtazapine: a review of its use in major depression and other psychiatric disorders. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(5):427–452.

- Shin JJ, Saadabadi A. Trazodone. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Jaffer KY, Chang T, Vanle B, et al. Trazodone for insomnia: a systematic review. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2017;14(7–8):24–34.

- Goracci A, Forgione RN, De Giorgi R, et al. Practical guidance for prescribing trazodone extended-release in major depression. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;17(3):433–441.

- Staiger B. What is agomelatine and why isn’t it available in the United States? [Internet]. Updated 2019 Oct 28. Available from. https://walrus.com/articles/what-is-agomelatine-and-why-isn-t-it-available-in-the-united-states

- Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 3. Pharmacological treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):540–560.

- Jefferson JW, Pradko JF, Muir KT. Bupropion for major depressive disorder: pharmacokinetic and formulation considerations. Clin Ther. 2005;27(11):1685–1695.

- Patel K, Allen S, Haque MN, et al. Bupropion: a systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness as an antidepressant. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(2):99–144.

- Sanchez C, Asin KE, Artigas F. Vortioxetine, a novel antidepressant with multimodal activity: review of preclinical and clinical data. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;145:43–57.

- Citrome L. Vilazodone, levomilnacipran and vortioxetine for major depressive disorder: the 15-min challenge to sort these agents out. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(2):151–155.

- Wang SM, Han C, Lee SJ, et al. Vilazodone for the treatment of depression: an update. Chonnam Med J. 2016;52(2):91–100.

- Trintellix [package insert]. Deerfield. IL: Takeda Pharmaceuticals America, Inc; 2021.

- Montano CB, Jackson WC, Vanacore D, et al. Practical advice for primary care clinicians on the safe and effective use of vortioxetine for patients with major depressive disorder (MDD). Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2022;18:867–879.

- Stahl SM. Dextromethorphan/bupropion: a novel oral NMDA (N-methyl-d-aspartate) receptor antagonist with multimodal activity. CNS Spectr. 2019;24(5):461–466.

- Messer MM, Haller IV. Minn Med.2018;November/December:36–40.

- Sanacora G, Frye MA, McDonald W, et al. A consensus statement on the use of ketamine in the treatment of mood disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):399–405.

- Auvelity [package insert]. New York NY: Axsome Therapeutics, Inc; 2022.

- Khabir Y, Hashmi MR, Ali Asghar A. Rapid-acting oral drug (Auvelity) for major depressive disorder. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;82:104629.

- Ng CW, How CH, Ng YP. Depression in primary care: assessing suicide risk. Singapore Med J. 2017;58(2):72–77.

- Seok Seo J, Rim Song H, Bin Lee H, et al. The Korean medication algorithm for depressive disorder: second revision. J Affect Disord. 2014;167:312–321.

- Bond DJ, Hadjipavlou G, Lam RW, et al. The Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) task force recommendations for the management of patients with mood disorders and comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012;24(1):23–37.

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1357–1366.

- Del Casale A, Pomes LM, Bonanni L, et al. Pharmacogenomics-guided pharmacotherapy in patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder affected by treatment-resistant depressive episodes: a long-term follow-up study. J Pers Med. 2022;12(2):316.

- Li Z, Ruan M, Chen J, et al. Major depressive disorder: advances in neuroscience research and translational applications. Neurosci Bull. 2021;37(6):863–880.

- Carvajal C. Poor response to treatment: beyond medication. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2004;6(1):93–103.

- Cartwright C, Gibson K, Read J, et al. Long-term antidepressant use: patient perspectives of benefits and adverse effects. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1401–1407.

- McIntyre RS. Using measurement strategies to identify and monitor residual symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(Suppl 2):14–18.

- McIntyre RS, Patel MD, Masand PS, et al. The Rapid Mood Screener (RMS): a novel and pragmatic screener for bipolar I disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(1):135–144.

- Ratheesh A, Davey C, Hetrick S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective transition from major depression to bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(4):273–284.

- Gitlin MJ. Antidepressants in bipolar depression: an enduring controversy. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):25.

- McElroy SL, Kotwal R, Kaneria R, et al. Antidepressants and suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(5 Pt 2):596–617.

- Kishi T, Ikuta T, Matsuda Y, et al. Mood stabilizers and/or antipsychotics for bipolar disorder in the maintenance phase: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(8):4146–4157.

- Haddad PM, Talbot PS, Anderson IM, et al. Managing inadequate antidepressant response in depressive illness. Br Med Bull. 2015;115(1):183–201.

- Chan HN, Mitchell PB, Loo CK, et al. Pharmacological treatment approaches to difficult-to-treat depression. Med J Aust. 2013;199(Suppl 6):S44–S47.

- McIntosh D, Kutcher S, Binder C, et al. Adult ADHD and comorbid depression: a consensus-derived diagnostic algorithm for ADHD. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:137–150.

- Sternat T, Katzman MA. Neurobiology of hedonic tone: the relationship between treatment-resistant depression, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and substance abuse. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2149–2164.

- Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance (CADDRA). Canadian ADHD practice guidelines. 4th ed. Toronto (ON): CADDRA; 2018.

- Verbeeck W, Bekkering GE, Van den Noortgate W, et al. Bupropion for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;10(10):CD009504.

- Yu C, Garcia-Olivares J, Candler S, et al. New insights into the mechanism of action of viloxazine: serotonin and norepinephrine modulating properties. J Exp Pharmacol. 2020;12:285–300.

- Qelbree [package insert]. Rockville. MD: Supernus Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2022.

- Kinrys G, Gold AK, Pisano VD, et al. Tachyphylaxis in major depressive disorder: a review of the current state of research. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:488–497.

- MacQueen G, Santaguida P, Keshavarz H, et al. Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines for failed antidepressant treatment response in major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and subthreshold depression in adults. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(1):11–23.

- Durgam S, Earley W, Guo H, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive cariprazine in inadequate responders to antidepressants: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adult patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(3):371–378.

- Lam RW, Parikh SV, Michalak EE, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) consensus recommendations for functional outcomes in major depressive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2015;27(2):142–149.

- Evans VC, Alamian G, McLeod J, et al. The effects of newer antidepressants on occupational impairment in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. CNS Drugs. 2016;30(5):405–417.