ABSTRACT

Objectives

Early diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and mild Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia is crucial for effective disease management and optimizing patient outcomes. We sought to better understand the MCI and mild AD dementia medical journey from the perspective of patients, care partners, and physicians.

Methods

We conducted online surveys in the United States among patients/care partners and physicians in 2021.

Results

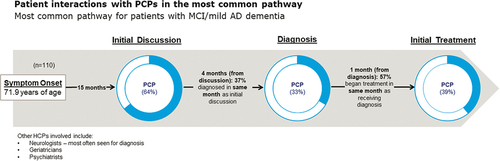

103 patients with all-cause MCI or mild AD dementia aged 46–90 years, 150 care partners for someone with all-cause MCI or mild AD dementia, and 301 physicians (101 of which were primary care physicians, [PCPs]) completed surveys. Most patient/care partners reported that experiencing forgetfulness (71%) and short-term memory loss (68%) occurred before talking to a healthcare professional. Most patients (73%) followed a common medical journey, in which the initial discussion with a PCP took place 15 months after symptom onset. However, only 33% and 39% were diagnosed and treated by a PCP, respectively. Most (74%) PCPs viewed themselves as coordinators of care for their patients with MCI and mild AD dementia. Over one-third (37%) of patients/care partners viewed PCPs as the care coordinator.

Conclusions

PCPs play a vital role in the timely diagnosis and treatment of MCI and mild AD dementia but often are not considered the care coordinator. For the majority of patients, the initial discussion with a PCP took place 15 months after symptom onset; therefore, it is important to educate patients/care partners and PCPs on MCI and AD risk factors, early symptom recognition, and the need for early diagnosis and treatment. PCPs could improve patient care and outcomes by building their understanding of the need for early AD diagnosis and treatment and improving the efficiency of the patient medical journey by serving as coordinators of care.

Plain Language Summary

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is not a normal part of aging, but many people develop AD as they age, and it is the seventh leading cause of death in the US. AD is a neurological condition that begins as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or mild AD dementia. To understand the medical journey of patients with MCI or mild AD dementia, we surveyed 103 patients with MCI or mild AD dementia, 150 care partners, and 301 doctors. Patients had several symptoms before talking to a doctor, including forgetfulness and short-term memory loss; most patients (64%) first discussed these symptoms with a primary care physician (PCP) on average 15 months later. However, most patients were not diagnosed or treated by a PCP for MCI or mild AD dementia. We asked patients/care partners who they believe is the coordinator of their care for MCI and mild AD dementia. Thirty-seven percent felt the PCP was the coordinator of care. Most surveyed PCPs (74%) considered themselves to be the coordinator of care for their patients with MCI or mild AD dementia. In conclusion, PCPs play a key role in the care of patients with MCI and mild AD dementia. It is important for patients and care partners to understand the symptoms of MCI and mild AD dementia, and the need to get a diagnosis and treatment soon after symptoms appear. PCPs can play an important role in early diagnosis and treatment and serve as coordinators of care for their patients with MCI and mild AD dementia.

Introduction

Dementia is a syndrome associated with memory loss, confusion, and difficulty with language or problem-solving skills, that results in the inability to function independently. The most common cause of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), accounting for up to 80% of dementia cases [Citation1]. AD is a progressive disease characterized by pathologic accumulation of beta-amyloid and neurofibrillary tau tangles in the brain, leading to neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and cognitive impairment [Citation2]. AD is associated with cardiometabolic conditions [Citation3–6] with a potential bidirectional relationship [Citation7]. Dementia syndromes and cardiovascular disease share risk factors such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking, type 2 diabetes, and poor exercise habits [Citation8]. The underlying pathophysiology of AD begins decades before cognitive symptoms develop, with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) classified as the first clinical stage. The next stage is AD dementia, categorized as mild, moderate, or severe based on symptom severity [Citation2]. MCI describes a condition where individuals have cognitive impairment with minimal disruption to instrumental activities of daily living [Citation9]. MCI can be the first cognitive expression of AD, but it can also be a sign of other neurologic and psychiatric disorders [Citation9]. MCI is estimated to be prevalent in 6.7% of individuals aged 60–64 years, rising to 25.2% in individuals aged 80–84 years [Citation9]. A meta-analysis estimated that 14.9% of individuals aged ≥65 years with MCI developed dementia within the 2-year study period [Citation9].

AD dementia affects about 6.5 million people in the US and is projected to increase to 13.8 million by 2060 [Citation2,Citation10]. AD is the seventh leading cause of death in the US overall, and the fifth among people aged 65 or older [Citation11]. Between 2000 and 2019, the AD mortality rate increased from 17.6/100,000 to 37.0/100,000 individuals [Citation2,Citation11]. Registry data showed that within 10 years, all-cause mortality was 30% in people aged 70 without AD dementia, compared to 61% of people with AD dementia [Citation12]. Additionally, AD is the sixth leading cause of disability-adjusted life years in the US [Citation13].

Early detection and diagnosis of MCI and mild AD dementia are essential to guide appropriate treatment and management [Citation14–16]; primary care physicians (PCPs) play a critical role in the process [Citation17–19]. Timely identification can help patients by allowing more time to plan for future care and implement measures to slow disease progression as well as providing an opportunity to discuss lifestyle interventions to optimize cognitive outcomes [Citation8,Citation20,Citation21]. However, timely diagnosis can be challenging because of delays in patients seeking care, lack of diagnostic tools, lack of multidisciplinary teams, and limited treatment options [Citation16,Citation22,Citation23]. The World Health Organization recommends interventions including physical activity, social activity, tobacco cessation, Mediterranean-like diets, and management of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity to manage risk factors and slow cognitive decline [Citation21].

To better understand experiences of patients with all-cause MCI and mild AD dementia, we explored the medical journey from the perspective of patients/care partners and PCPs. We aimed to map the touch points along the journey, assess how MCI and mild AD dementia are diagnosed and managed, and identify opportunities to improve patient outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study design

In 2021, we conducted an online survey with patients diagnosed with all-cause MCI or mild AD dementia, care partners, and physicians treating patients with MCI or mild AD dementia. We recruited study participants from online panel companies (ClinicalVoice Community, Survey Healthcare Global, Dynata LLC, Schlesinger Group, Prodege, and Cint) of individuals (general population and healthcare professionals) across the US who have opted-into research survey participation. Email invitations indicated the voluntary nature of the research and that respondents could discontinue at any time. We required respondents to consent prior to screening. Several screening questions were asked of respondents to determine if they qualified for the survey (inclusion/exclusion criteria). Those qualifying for and completing the survey received a modest monetary incentive. Western Institutional Review Board reviewed the study protocol and determined the study to be exempt from review. The survey was conducted by a third-party vendor (KJT Group, Inc., Rochester, NY, U.S.A). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki with adequate protections for the survey participants.

Patients/care partners and physicians completed separate surveys (Appendix 1) with similar content to enable comparisons regarding attitudes and experiences. Survey topics included symptoms, discussions with healthcare professionals (HCPs), and attitudes about comorbidities. The surveys were developed by the study team based on a literature review and qualitative interviews with patients with MCI or mild AD dementia, care partners, and treating physicians. As the surveys were intended to be descriptive in nature, they were not validated. The surveys consisted of yes/no, single-select, multiple-choice, and Likert-scale questions. Some questions were only asked of care partners, such as those regarding receipt of health care by the patient with MCI or mild AD dementia.

Participants

Participating patients, care partners, and physicians were independent of each other. Qualified patients were US residents, had an MCI or mild AD dementia diagnosis, and were aged ≥46 years. Qualified care partners were at least age 18 and involved in making medical decisions for someone with MCI or mild AD dementia. Respondents were excluded if they/the person they care for were diagnosed with another type of dementia or were in the moderate/severe stage of AD. Qualified physicians were those practicing in the US; specializing in primary care, geriatrics/gerontology, neurology, or psychiatry; in practice between 1–35 years; board-certified; and treating at least 10 or 25 patients (PCPs and all other physicians, respectively) with all-cause MCI or mild AD dementia in the past month. Physicians were excluded if they practiced in a government/Veteran’s Affairs hospital or ambulatory surgical center.

To ensure we properly identified study participants, we presented survey respondents with a list of medical conditions including ‘mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or cognitive dysfunction,’ ‘Alzheimer’s disease (AD),’ and ‘dementia (frontotemporal, vascular, mixed, early-onset),’ and asked them to self-report if they/someone they care for had been diagnosed by a healthcare professional with any of these. Respondents selecting ‘Alzheimer’s disease’ were asked if the stage of AD was ‘early (or prodromal),’ ‘mild,’ or ‘moderate/severe.’ We asked physicians to only consider their patients for whom the underlying etiology of MCI was unknown, or suspected to be AD. Therefore, we have chosen to refer to the cohort of eligible patients as having all-cause MCI or mild AD dementia.

Statistical analyses

We performed descriptive statistical analyses of the aggregated data using Q Research Software for Windows 23 (A Division of Displayr, Inc., New South Wales, Australia). Tests of differences (chi square, t-tests) within respondent types were performed using Q Research Software tables; we performed additional analyses using R Statistical Software (R Core Team 2020). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, using two-tailed tests. We present categorical data as percentages and continuous data as mean values. To assess the medical journey of patients with MCI or mild AD dementia, we asked care partners to list the order in which they/patients 1) had discussions about possible MCI or AD symptoms, 2) received a diagnosis, and 3) received treatment. The ‘most common medical journey’ was defined as the medical journey reported by the majority of care partners for the patients they assist based on the multiple possible permutations. Patients with MCI or mild AD dementia may not be able to accurately recall their experiences, thus we limited questions regarding the patient medical journey to care partners. Patient and care partner response data were typically grouped for reporting purposes; care partner respondents were surveyed to act as proxies for patients with MCI or mild AD dementia and were not linked with patient respondents. However, there were instances where care partner responses differed, in aggregate, from patient responses and we highlighted those discrepancies in the results.

Results

Sample characteristics

Of the 12,272 patient or care partner respondents who entered the survey, 253 completed the survey; the remainder did not meet the qualification criteria or did not finish the survey. Of these 253 respondents, 103 patients completed the survey on their own; 150 care partners took the survey on behalf of someone with MCI or mild AD dementia. Of the 728 physician respondents entering the survey, 427 did not meet the qualification criteria, did not finish the survey, or were over the allotted quota. Of the 301 qualified physician participants, 101 identified as PCPs; although their responses are the focus of this paper, we make some comparisons to the other physicians surveyed which include neurologists, geriatricians, and psychiatrists. The perspective of neurologists has been previously reported [Citation24]. Data presented represents the demographics of patients with MCI and mild AD dementia regardless of the survey-taker; care partners responded on behalf of the person for whom they provide care. Participant characteristics are shown in .

Table 1. Characteristics of patient/care partner and physician survey respondents.

Pre-diagnosis

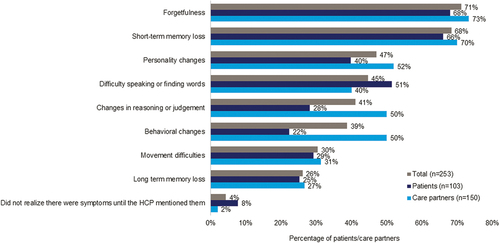

Patients/care partners reported that patients most often experienced forgetfulness (71%) and short-term memory loss (68%) before discussing MCI or mild AD dementia symptoms with an HCP (). Patients/care partners indicated the reasons for delaying discussions of symptoms were attributing symptoms to normal aging (49%), denying experiencing a cognitive health/memory issue (44%), lack of impact on daily functioning (32%), and fear of being diagnosed (31%). Care partners (51%) were more likely than patients (34%) to report delays due to patient denial. Only 2% of patients/care partners made an appointment as soon as possible after noticing symptoms. The primary reasons patients/care partners initiated discussions with an HCP were symptoms interfering with activities of daily life (51%), symptoms not resolving on their own (46%), encouragement from family or friends (44%), and worsening symptoms (43%).

Figure 1. MCI or Mild AD dementia symptoms experienced prior to first discussion with an HCP.

As reported by care partners, 73% of patients followed a similar medical journey of initial discussion, diagnosis, and treatment, termed ‘the most common medical journey.’ This medical journey is shown in , highlighting the proportion of patients who had contact with a PCP in their journey. Mean symptom onset was age 72, with initial discussion most often with a PCP occurring 15 months later. One-third of patients were diagnosed by a PCP, whereas 51% were diagnosed by a neurologist, 11% by a geriatrician, and 5% by a psychiatrist. Patients received treatment primarily from a PCP (39%) () or a neurologist (39%, data not shown). Of their patients presenting with MCI or mild AD dementia symptoms, PCPs reported diagnosing about half (54%) of these patients themselves. Among PCPs who referred their patients (n = 86) to another clinician to confirm the diagnosis of MCI or mild AD dementia, most (93%) sent their patients to a neurologist.

Diagnosis

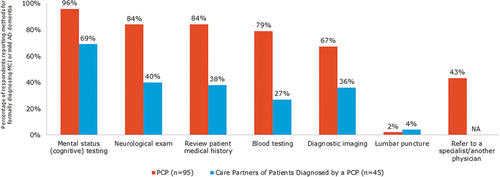

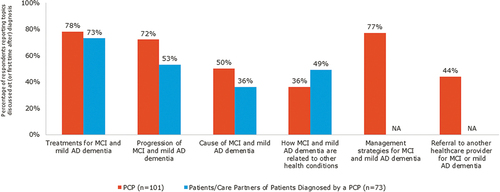

PCPs and care partners reported that cognitive testing was the most commonly used tool for making a formal diagnosis (). Upon diagnosis, the topic most commonly discussed by PCPs and patients/care partners was ‘treatments for MCI and mild AD dementia’ (). PCPs were less likely than the other physicians surveyed to report discussing ‘causes of MCI and mild AD dementia’ (50% vs 59% to 83%) and ‘how MCI and mild AD dementia are related to other health conditions’ (36% vs 54% to 64%). However, PCPs were more likely than the other physicians surveyed (44% vs 12%-19%) to discuss a referral to another physician for MCI and mild AD dementia care.

Treatment and management of MCI and mild AD dementia

PCPs reported initiating treatments for 50% of their patients with MCI or mild AD dementia and referring 33% to another physician for treatment/management, more than any other physician specialty surveyed (12%-14%). PCPs reported referring most of their patients (58%) to neurologists because of worsening symptoms, for additional management or treatment, or the need for specialized symptom management. For ongoing treatment and management of their patients with MCI or mild AD dementia, PCPs prescribed or recommended acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors (82%), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists (84%), medications to manage comorbidities (84%), general improvements in lifestyle (80%), mental exercises (78%), and vitamins/supplements (42%).

Over half (55%) of PCPs reported discussing cardiometabolic conditions in relation to MCI and mild AD dementia with their patients at every/almost every visit. Nearly all PCPs (92%) believed cardiometabolic conditions put people at risk for MCI or mild AD dementia, with over half (55%) reporting a bidirectional relationship. Approximately half of PCPs felt that cardiometabolic conditions greatly impact the initial development (41%), severity (52%), and rate of progression (53%) of MCI and mild AD dementia.

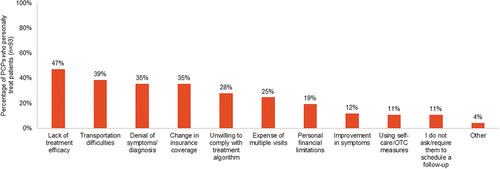

PCPs reported the top three barriers to managing MCI and mild AD dementia were lack of efficacious treatments (82%), patient motivation and adherence (50%), and limited time during patient visits (46%). Lack of treatment efficacy was cited as a primary reason PCPs believed their patients may stop seeing them for MCI or mild AD dementia management ().

Attitudes and behaviors regarding MCI and mild AD treatment and management

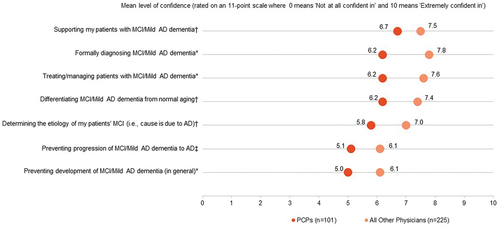

Over one-quarter (29%) of PCPs reported not following any specific guidelines for MCI and mild AD dementia management. Less than half (42%) reported receiving formal training in diagnosing and managing MCI and mild AD dementia. Three-quarters of surveyed PCPs (74%) viewed themselves as coordinators of care for their patients with MCI or mild AD dementia. Thirty-seven percent of patients/care partners viewed PCP as the care coordinators. No one specialty was identified as the main care coordinator with 8% to 35% of patients/care partners considering geriatricians, psychiatrists, or neurologists to be the primary care coordinator. PCPs were moderately confident with providing care for patients with MCI or mild AD dementia, lower than the other physicians surveyed (). PCPs reported being significantly less confident than the other physicians surveyed (neurologists, geriatricians, and psychiatrists) in formally diagnosing AD dementia (6.2 vs 7.8, p < 0.05), treating/managing patients with AD dementia (6.2 vs 7.6, p < 0.05), and preventing development of MCI/mild AD dementia in general (5.0 vs 6.1, p < 0.05). However, PCPs were moderately interested in providing care to patients with MCI or mild AD dementia – they rated each aspect of care 6.8 to 7.2 on an 11-point scale, with zero being ‘not at all interested’ to ten being ‘extremely interested.’

Figure 6. Level of confidence in providing care for patients with MCI or mild AD dementia.

Discussion

Findings in the context of published literature

This research examined the patient medical journey for all-cause MCI and mild AD dementia from multiple perspectives, adding to the limited literature on this topic which is primarily qualitative in nature and focused on the difficulties of living with MCI or AD [Citation25–30]. Getting the perspective of patients with these conditions can be challenging; however, it is important to assess their viewpoint as it may differ significantly from those of care partners [Citation31]. Early AD diagnosis and treatment is critical; however, patients in the ‘most common medical journey’ waited over a year to talk to an HCP about their cognitive symptoms. Discussions were typically initiated when symptoms interfered with daily life activities or failed to resolve.

These findings are similar to a 2021 Alzheimer’s Association survey of US adults demonstrating that most Americans would wait to talk to a doctor until symptoms worsened or until their friends or family expressed concern [Citation2]. PCPs are typically the first point of contact for patients with MCI or mild AD dementia, and PCPs see themselves as the coordinators of care. PCPs report personally diagnosing about half of their patients who present with MCI or mild AD dementia, but most referred to a neurologist for diagnosis. Initial discussion of cognitive symptoms typically occurred with a PCP, but only one-third of patients in ‘the most common medical journey’ received their diagnosis from a PCP. Our results differ from an analysis of Medicare beneficiaries showing 85% of patients with all-cause dementia were initially diagnosed by non-specialists [Citation32]. These differences could be due to data collection timing, patient demographics, inclusion of any dementia type in the Medicare study, and care partner recall in our study [Citation32].

We found that PCPs believe the greatest barrier to managing MCI and mild AD dementia is lack of effective treatment options. Delaying development of AD dementia in patients with MCI may be possible with early diagnosis and treatment [Citation8]. This is particularly important due to the substantial loss of quality of life and the financial burden to the patient, care partner, and society that AD dementia imparts [Citation2,Citation8,Citation33–38]. Our results are similar to other studies in which PCPs reported barriers to early diagnosis including patients’ attributing symptoms to normal aging; and lack of time for patient assessments, treatment options, diagnostic tools, interdisciplinary teams, connections with community social service agencies, and support for PCPs [Citation22,Citation39]. We found modest levels of PCP confidence in providing various aspects of care related to MCI and mild AD dementia, similar to other surveys of PCPs [Citation2,Citation40,Citation41]. Since this survey was conducted, pharmacological therapies have been approved for treatment of AD in the US, and other compounds in development for AD are showing promise [Citation42]. It is anticipated that continued advances in pharmacological therapies for AD will improve patient outcomes and encourage PCPs to be more proactive in diagnosing and treating the disease.

Education of patients and care partners is also a crucial step in effectively diagnosing and managing MCI and AD. It is important that patients and care partners recognize the symptoms of MCI and mild AD dementia and understand the importance of talking to their PCP when symptoms first develop; however, only 18% of adults are familiar with MCI [Citation2]. It is also important for patients to understand risk factors for MCI and mild AD dementia, such as cardiometabolic comorbidities, in order to reduce risk where possible.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include self-reporting and the absence of medical records/biomarker evidence to confirm an MCI or mild AD dementia diagnosis. Patients with MCI or mild AD dementia may not be able to accurately recall their experiences, thus we limited questions regarding the patient medical journey to care partners. We also only included patients early in their disease where cognitive decline is less pronounced. Additionally, the patients were not matched to the care partners or to the physicians surveyed. Thus, it is possible that differences between responses from patients/care partners and physicians may not represent actual variations in perceptions. Patients for whom care partners completed the surveys may have different MCI or mild AD dementia features than patients who took the survey themselves.

Patients/care partners in our study were aware that they/the person they care for had all-cause MCI or mild AD dementia. As such, our survey findings may not be generalizable to other patients with undiagnosed MCI or mild AD dementia. Another limitation is the exclusion of respondents who selected ‘dementia (frontotemporal, vascular, mixed, early-onset)’ as patients may believe or been told they have dementia but actually have MCI or AD. Additionally, patients/care partners belonging to an online panel and those responding to the survey may be different than nonmembers or non-responders. We reduced the potential for responder bias by not revealing the specific survey topic until respondents met the required screening criteria. Lastly, because the surveyed physicians had to have seen more than a certain threshold of patients with MCI or mild AD dementia, they may be different than physicians seeing fewer patients per month.

Conclusions

We explored the medical journey of patients with all-cause MCI and mild AD dementia from the perspective of patients/care partners and PCPs and aimed to map the touch points along the journey, assess how MCI and mild AD dementia are diagnosed and managed, and identify opportunities to improve patient outcomes.

Timely diagnosis is essential for appropriate treatment and management with the potential for improved patient outcomes. PCPs can play a vital role in diagnosing and managing MCI and mild AD dementia, although most reported that they have not received formal training in this area and are not highly confident in their ability to do so. Additionally, lack of effective treatments was reported as a substantial barrier to managing MCI and mild AD dementia. It is important to educate patients/care partners and PCPs on MCI and AD risk factors, early symptom recognition, and the need for early diagnosis and treatment. Future research could further investigate and evaluate effective approaches to reducing the time to AD diagnosis and improving the efficiency of the patient medical journey.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

S Brunton has received consulting fees from Acadia and Novo Nordisk; and is also on the speakers’ bureau for Novo Nordisk. J Pruzin has received grants from the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center for a research project involving cardiovascular disease, APOE, and blood biomarkers in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease; he is the recipient of an Alzheimer’s Association Clinician Scientist Fellowship award examining physical activity, cardiovascular risk and their influence on AD. S Alford, C Hamersky and A Sabharwal are employees and shareholders of Novo Nordisk Inc. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

S Brunton, J Pruzin, and G Gopalakrishna interpreted the data included in the manuscript and critically revised each draft. S Alford, C Hamersky, and A Sabharwal contributed to the design and conduct of the study, interpreted the data included in the manuscript, and critically revised each draft. All authors had access to the study data, decided where to submit the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (563.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rebecca Hahn and Elizabeth Tanner of KJT Group, Inc., Rochester, NY for providing medical writing support, which was funded by Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, NJ in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

Data availability statement

The underlying dataset discussed in this manuscript is proprietary and will not be posted publicly. However, the data can be made available to researchers upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2023.2217025

Additional information

Funding

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). What is Alzheimer’s disease [May 27, 2022]. Available from: https://www.alzheimers.gov/alzheimers-dementias/alzheimers-disease

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2022 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(4):700–789. doi:10.1002/alz.12638

- Alonso A, Knopman DS, Gottesman RF, et al. Correlates of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in patients with atrial fibrillation: the atherosclerosis risk in communities neurocognitive study (ARIC-NCS). J Am Heart Assoc. 2017 Jul 24;6(7). doi :10.1161/JAHA.117.006014.

- Bhat NR. Linking cardiometabolic disorders to sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: a perspective on potential mechanisms and mediators. J Neurochem. 2010 Nov;115(3):551–562.

- Lu Y, Fülöp T, Gwee X, et al. Cardiometabolic and vascular disease factors and mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Gerontology. 2022 Jan;68(9):1–9.

- Mazzoccoli G, Dagostino MP, Vinciguerra M, et al. An association study between epicardial fat thickness and cognitive impairment in the elderly. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014 Nov 1;307(9):H1269–76.

- Rojas M, Chávez-Castillo M, Pirela D, et al. Metabolic syndrome: is it time to add the central nervous system? Nutrients. 2021 Jun 30;13(7):2254.

- Rasmussen J, Langerman H. Alzheimer’s disease - why we need early diagnosis. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis. 2019;9:123–130.

- Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, et al. Practice guideline update summary: mild cognitive impairment: report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018 Jan 16;90(3):126–135.

- Rajan KB, Weuve J, Barnes LL, et al. Population estimate of people with clinical Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020-2060). Alzheimers Dement. 2021 Dec;17(12):1966–1975.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying cause of death 1999-2020 on CDC WONDER online database: centers for disease control and prevention; 2021 [Apr 5, 2022]. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2020, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.]. Available from: http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html

- Arrighi HM, Neumann PJ, Lieberburg IM, et al. Lethality of Alzheimer disease and its impact on nursing home placement. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010 Jan;24(1):90–95.

- US Burden of Disease Collaborators, Mokad Ali H, Ballestros K, et al. The state of US health, 1990-2016: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US states. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1444–1472.

- Atri A. The Alzheimer’s disease clinical spectrum: diagnosis and management. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103(2):263–293.

- Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Pentzek M. Clinical recognition of dementia and cognitive impairment in primary care: a meta-analysis of physician accuracy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124(3):165–183.

- Porsteinsson AP, Isaacson RS, Knox S, et al. Diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease: clinical practice in 2021. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2021;8(3):371–386. DOI:10.14283/jpad.2021.23

- Villars H, Oustric S, Andrieu S, et al. The primary care physician and Alzheimer’s disease: an international position paper. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010 Feb;14(2):110–120.

- Herman L, Atri A, Salloway S. Alzheimer’s Disease in primary care: the significance of early detection, diagnosis, and intervention. Am J Med. 2017;130(6):756.

- Moore A, Frank C, Chambers LW. Role of the family physician in dementia care. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(10):717–719.

- Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, et al. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2009;23(4):306–314. DOI:10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181a6bebc

- World Health Organization. Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia: WHO guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

- Judge D, Roberts J, Khandker R, et al. Physician perceptions about the barriers to prompt diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2019 2019 Mar 21;2019:3637954.

- Kurtz KR, McKee A, Murphy V, et al. Examining the lived experience of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI): an evidence-based practice project. Retrieved from https://sophia.stkate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=ot_grad.

- Pruzin JJ, Brunton S, Alford S, et al. Medical journey of patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild alzheimer’s disease dementia: a cross-sectional survey of patients, care partners, and neurologists. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2023;10(2):162–170. DOI:10.14283/jpad.2023.21

- Beard RL, Neary TM. Making sense of nonsense: experiences of mild cognitive impairment. Sociology Of Health & Illness. 2013;35(1):130–146. DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01481.x

- Hailu T, Cannuscio CC, Dupuis R, et al. A typical day with mild cognitive impairment. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):927–928. DOI:10.2105/AJPH.2017.303752

- Admin JAD Case Study: Understanding the Alzheimer’s Disease (including MCI) Patient Journey with Limited Patient Voice. 2020. [cited Mar 18, 2020]. Available from: https://www.j-alz.com/editors-blog/posts/case-study-understanding-alzheimers-disease-including-mci-patient-journey

- Lingler JH, Nightingale MC, Erlen JA, et al. Making sense of mild cognitive impairment: a qualitative exploration of the patient’s experience. Gerontologist. 2006 Dec;46(6):791–800.

- Morris JL, Hu L, Hunsaker A, et al. Patients’ and family members’ subjective experiences of a diagnostic evaluation of mild cognitive impairment. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(1):124–131. DOI:10.1177/2374373518818204

- Riquelme-Galindo J, García-Sanjuán S, Lillo-Crespo M, et al. Experience of people in mild and moderate stages of Alzheimer’s disease in Spain. Aquichan. 2020;20(4):1–11. DOI:10.5294/aqui.2020.20.4.4

- Lepore MSB, Wiener JM, Gould E. Challenges in involving people with dementia as study participants in research on care and services. US Department of Health and Human Services research summit on dementia care: building evidence for services and supports. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2017.

- Drabo EF, Barthold D, Joyce G, et al. Longitudinal analysis of dementia diagnosis and specialty care among racially diverse Medicare beneficiaries. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(11):1402–1411. DOI:10.1016/j.jalz.2019.07.005

- Zucchella C, Bartolo M, Pasotti C, et al. Caregiver burden and coping in early-stage Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012 Jan;26(1):55–60.

- Bárrios H, Narciso S, Guerreiro M, et al. Quality of life in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Aging Mental Health. 2013;17(3):287–292. DOI:10.1080/13607863.2012.747083

- Teng E, Tassniyom K, Lu PH. Reduced quality-of-life ratings in mild cognitive impairment: analyses of subject and informant responses. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012 Dec;20(12):1016–1025.

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2021 Mar;17(3):327–406. DOI:10.1002/alz.12328

- Jutkowitz E, Kane RL, Gaugler JE, et al. Societal and family lifetime cost of dementia: implications for policy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017 Oct;65(10):2169–2175.

- Grabher BJ. Effects of Alzheimer disease on patients and their family. J Nucl Med Technol. 2018;46(4):335.

- Hinton L, Franz CE, Reddy G, et al. Practice constraints, behavioral problems, and dementia care: primary care physicians’ perspectives. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Nov;22(11):1487–1492.

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2020 Mar 10.

- Bernstein A, Rogers KM, Possin KL, et al. Dementia assessment and management in primary care settings: a survey of current provider practices in the United States. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019 2019Nov29;19(1):919. DOI:10.1186/s12913-019-4603-2.

- Conti Filho CE, Loss LB, Marcolongo-Pereira C, et al. Advances in Alzheimer’s disease’s pharmacological treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1101452.