ABSTRACT

Objectives

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) are closely linked conditions, and the presence of each condition promotes incidence and progression of the other. In this study, we sought to better understand the medical journey of patients with CKD and ASCVD and to uncover patients’ and healthcare providers’ (HCPs) perceptions and attitudes toward CKD and ASCVD diagnosis, treatment, and care coordination.

Methods

Cross-sectional, US-population-based online surveys were conducted between May 18, 2021, and June 17, 2021, among 239 HCPs (70 of whom were primary care physicians, or PCPs) and 195 patients with CKD and ASCVD.

Results

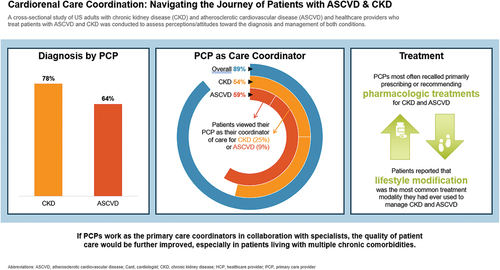

PCPs reported personally diagnosing CKD in 78% and ASVD in 64% of their patients, respectively. PCPs reported they are more likely to serve as the overall coordinator of their patient’s care (89%), while slightly more than half of PCPs self-identified as a patient’s coordinator of care specifically for CKD (54%) or ASCVD (59%). In contrast, patients viewed their PCP as their coordinator of care for CKD (25%) or ASCVD (9%). PCPs who personally treated patients with CKD and ASCVD most often recalled primarily prescribing or recommending pharmacologic treatments for CKD and ASCVD; however, patients reported that lifestyle modification was the most common treatment modality they had ever used to manage CKD and ASCVD.

Conclusion

CKD and ASCVD are interrelated cardiometabolic conditions with underlying risk factors that can be managed in a primary care setting. However, few patients in our study considered their PCP to be the coordinator of their care for CKD or ASCVD. PCPs can and should take a more active role in educating patients and coordinating care for those with CKD and ASCVD.

Plain Language Summary

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a medical condition where the kidneys are damaged, and their function is reduced. CKD is often linked to other health problems. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is a condition where cholesterol builds up in the arteries, leading to reduced blood flow and heart issues. This study wanted to understand what patients and healthcare providers (HCPs) know about these two conditions and how they are managed. We sent questionnaires to 195 patients with CKD and ASCVD as well as 239 HCPs who treat patients with CKD and ASCVD. The results showed primary care physicians (PCPs) are the main healthcare providers for most patients, but specialists are often involved in managing CKD and ASCVD. PCPs play a crucial role in helping patients understand how other health care conditions can impact their risk for CKD and ASCVD. PCPs can also guide patients on making lifestyle changes to lower their risk of these diseases and can refer patients to specialists, while still providing guidance on management of these conditions.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), a condition characterized by an abnormality of the kidney structure resulting in a decrement in function that persists for more than three months, is estimated to currently affect approximately 14% of adults in the United States (US) [Citation1]., With an aging population and increasing rates of comorbidities such as obesity, hypertension and Type 2 diabetes (T2D), it is anticipated that the impact will continue to increase over time [Citation1]. CKD is frequently under-recognized in the primary care setting, largely due to its asymptomatic presentation at earlier stages [Citation2]. It is believed that as many as nine out of 10 adults with CKD do not know they have CKD, and two out of five adults with severe CKD are unaware they have CKD at all [Citation3,Citation4]. Research suggests that gaps may exist between clinical practice guidelines and use of diagnostic screenings, such as ACR testing, which may lead to under-diagnosis of CKD [Citation5,Citation6].

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), characterized by arterial atherosclerosis leading to coronary events such as myocardial infarction (MI) or stable angina, ischemic stroke or peripheral artery disease, is estimated to affect [Citation7–9] approximately 26 million US adults [Citation10], although as many as 125 million people in the US are at risk of developing ASCVD due to coexisting conditions such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes and CKD [Citation11]. ASCVD is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in US adults, with an estimated 400,000 deaths each year [Citation11].

CKD and ASCVD share common risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia; inflammation is a driver for the progression of both CKD and CVD [Citation12,Citation13]. Similarly, those with reduced kidney function measured by eGFR exhibit increased risk for atherosclerosis, meaning those with CKD are at higher risk for major cardiovascular events [Citation14–16]. As both CKD and ASCVD clinical presentations can vary, patients with multiple underlying risk factors should be evaluated with a high degree of clinical suspicion and screened for both conditions according to clinical practice guidelines [Citation17,Citation18]. However, many patients may lack one primary provider who is aware of all their conditions (particularly those that interact with each other), interventions, and diagnoses, offers comprehensive support, and serves as a link to other providers and resources. Many coordinated care models have, over time, demonstrated that disease management outcomes do improve with the implementation of a coordinated and comprehensive approach to evidence-based care [Citation19,Citation20].

The presentation of traditional risk factors for CKD and ASCVD offers many opportunities for primary care providers (PCPs) to address both conditions in a primary care setting: patient education about their risk for developing each condition, particularly in the presence of the other; risk reduction strategies; and identification of treatment modalities that can be managed by a PCP. Due to the interrelation of ASCVD, CKD and other cardiometabolic diseases, we sought to assess the patient journey within the health care system and to identify gaps in understanding of their conditions. The main objectives of this study were to better understand the attitudes and perceptions regarding how care is coordinated and treatment decisions are made regarding CKD and ASCVD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and participants

We conducted two cross-sectional studies among 195 patients living with both ASCVD and CKD and 239 healthcare providers (HCPs) who provide care for patients diagnosed with both conditions. The studies included a self-administered online survey (one per audience) that was emailed to respondents and completed between 18 May 2021, and 17 June 2021. The HCP respondents included physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants in various clinical settings (family and general practice, internal medicine, cardiology, nephrology, and endocrinology).

Respondents were recruited via e-mail invitations from online panel companies to which they had provided permission to be contacted for research purposes. Respondents were made aware that the research was voluntary, and they were allowed to opt out at any time. Participants were blinded to the study sponsor and the study sponsor was blinded to the participants. Respondents completed a series of screening questions to determine their eligibility for the study; only those who selected ‘yes’ (from yes/no options) to indicate consent to participate in the study were allowed to continue to the screening portion of the survey. All responses were self-reported and were not verified through a third party. Participants were provided a modest monetary incentive upon completion of the survey. The study samples were independent; patients and HCPs surveyed were not matched pairs.

To be included in the study, patients were required to be US residents between the age of 40–79 years, who had been diagnosed with CKD and ASCVD. At the time of the survey, they were required to be in CKD Stage 2, 3 or 4 based on self-reported knowledge of their diagnosis. Patients were excluded if they didn’t know their CKD stage or were in kidney failure.

HCPs were required to be board-certified in their specialty, practicing in the US (except for Maine and Vermont to comply with Sunshine Act reporting requirements), have been in practice for 3–35 years, not be primarily seeing patients in a government or VA hospital or an ambulatory surgical center, and actively treating patients with both CKD and ASCVD in a typical month. HCPs were asked to provide their best estimates of patients seen and/or treated with CKD and ASCVD across a number of questions in the survey.

The study protocol was submitted to the WCG Institutional Review Board for ethical approval and was determined to be exempt because the research included survey procedures with adequate provisions to protect the privacy of subjects and maintain data confidentiality.

2.2 Survey design

Qualitative interviews with HCPs (n = 23) and patients (n = 28) were conducted via in-depth telephone interviews or asynchronously in an online format prior to the online survey in addition to a targeted literature review to inform the types of questions used in the survey tools. The survey instruments (Appendices 1 and 2) were not validated, and pilot testing was not conducted. Separate quantitative surveys were created for HCPs and patients to measure their perceptions of care for CKD and ASCVD, focusing on their experiences with diagnosis, treatment, and management. The surveys consisted of a variety of yes/no, multiple choice and Likert scale questions. We asked each patient to recall their age of diagnosis and the order in which each condition was diagnosed if multiple conditions were diagnosed in the same year, along with specialist referral for CKD and ASCVD, which led to constructing certain care pathways. The ‘most common patient journey’ discussed in this paper references a pathway wherein the diagnosis, treatment and management of patients followed a similar progression.

Patients were also asked to recall what topics they discussed with their HCP at diagnosis and regarding treatment and ongoing management of their conditions. The survey asked patients to consider the healthcare provider who is primarily responsible for managing their CKD or ASCVD in conjunction with any other conditions they have as their ‘coordinator of care.’ HCPs were asked to estimate the percentage of patients they personally diagnose with CKD and ASCVD, if they refer patients with suspected CKD and ASCVD to specialists (and if so, to whom), how often they follow up with patients with each condition, and what they prescribe or recommend for treatment and ongoing management.

2.3 Statistical analyses

We performed descriptive statistical analyses (means, frequencies) of the aggregated data using Q Research Software for Windows (A Division of Displayr, Inc., New South Wales, Australia). Tests of differences (chi square, t-tests) within respondent types were performed using Q Research Software tables; additional analyses to evaluate ages at which patients were diagnosed and to construct the patient journeys were performed using Stata/IC 14.1 and R (A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, using 2-tailed tests. Categorical data are expressed as counts and percentages.

3. Results

3.1 Sample characteristics

A total of 4,608 patient respondents entered the survey, and 4% (n = 195) qualified. Remaining respondents did not complete the survey, did not qualify or were over the quota. Of the 195 patient respondents who were diagnosed with both CKD and ASCVD, most (65%, n = 126) categorized themselves as being in CKD Stage 3 at the time of the survey. Twenty percent of patients (n = 39) were in CKD Stage 2 and 15% (n = 30) were in Stage 4.

A total of 1,522 HCPs entered the survey; of these, 239 HCPs who treat patients diagnosed with both CKD and ASCVD qualified (with remaining respondents having not completed the survey, not qualifying or being over quota). Of the 239 HCP respondents, 70 were PCPs; while their responses are the focus of this paper, we make some comparisons to the other HCPs surveyed, which included 74 with a focus in cardiovascular disease management (including cardiology nurse practitioners and physician assistants), 58 nephrologists, and 37 endocrinologists. Median patient survey length was 27 minutes and median HCP survey length was 29 minutes.

Seventy-three of the 195 patients (37%) had Type 2 diabetes and 122 (63%) did not. Sample characteristics of patients are shown in , and sample characteristics of HCPs are shown in .

Table 1. Patients’ baseline characteristics.

Table 2. HCPs’ baseline characteristics.

3.2 Initial discussion and diagnosis

According to all patients surveyed (n = 195), nearly half of them (46%) reported that they were diagnosed with CKD during an appointment that was scheduled to discuss their CKD symptoms, 41% reported they were diagnosed with ASCVD during an appointment to discuss their ASCVD symptoms, and 25% were diagnosed during a visit for an acute event. In qualitative interviews with patients prior to the online survey, six patients reported CKD symptoms to be frequent urination, fatigue, edema, water retention, and itching.

PCPs reported personally diagnosing 78% of their patients with CKD and 64% of their patients with ASCVD. Of those they personally diagnosed with CKD, PCPs reported patients in their clinical settings were at varying degrees of stages of the disease (26% at Stage 1, 30% at Stage 2 and 27% at Stage 3). Among patients who recalled that their HCP discussed the risk of developing CKD prior to their formal diagnosis (n = 69), 48% reported it was their PCP who most often discussed this. Among patients who recalled that their HCP discussed the risk of developing ASCVD prior to their formal diagnosis (n = 73), 56% reported it was their PCP who most often discussed this.

Looking across all patients (n = 195), 51% reported being diagnosed with CKD before ASCVD, 42% reported being diagnosed with ASCVD before CKD, and 8% reported being diagnosed in the same year, most often at the same time or appointment. In specifically looking at the most common medical patient journey, diagnosis order did not change by T2D status; 39% of patients without T2D (n = 77) were diagnosed with CKD prior to ASCVD. In the second most common patient journey, which also included patients without T2D, less than one quarter of patients (22%, n = 42) reported that their diagnosis of ASCVD preceded a CKD diagnosis.

3.3 Referral and care coordination

Of the PCPs who reported that they referred patients to other providers to confirm a patient’s CKD or ASCVD diagnosis, 47 referred to another provider for CKD diagnosis and 59 referred to another provider for ASCVD diagnosis. Nearly all HCPs (n = 211) claim they collaborate with a PCP for various reasons: care plan development across patients’ comorbidities (55%); updates on the progression or severity of the condition(s) they manage (55%); and lifestyle modification plan and progress (54%).

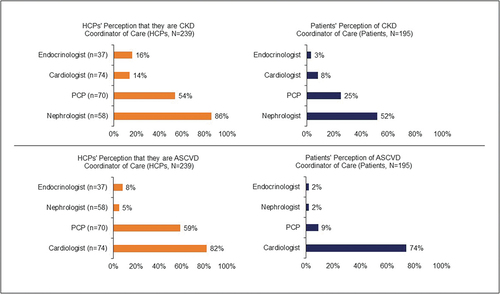

Patients’ perception of the coordinator of care for CKD, specifically, differed with their CKD stage. While 54% of patients in CKD Stage 3 considered their nephrologist to be their coordinator of CKD care (with 27% considering their PCP to be the coordinator of their CKD care), 80% of those in CKD Stage 4 considered their nephrologist to be the coordinator of their CKD care and none considered their PCP as such. PCPs reported they are more likely to take on responsibility for care coordination across all conditions, believing they are the overall coordinator of their patients’ care (89%). However, patients consider the relevant specialist to be the coordinator of care for their respective conditions (74% see their cardiologist as their coordinator for ASCVD and 52% see their nephrologist as their coordinator for CKD) ().

Figure 1. Overall patient and HCP perceptions of the coordinator of care for CKD and ASCVD. Based on patient respondents who answered “What type of healthcare provider do you typically think of as the ‘coordinator’ of your care?” for each condition, and HCP respondents who answered “I am the coordinator of care” to the question “What type of healthcare provider do you typically think of as the‘coordinator of care’ of patients with CKD / ASCVD?” for each condition. ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HCP, health care provider; PCP, primary care physician.

Although 54% of PCPs self-identified as a patient’s coordinator of care for CKD, and 59% self-identified as the coordinator of care for ASCVD, fewer patients saw their PCP as their coordinator of care for either condition (25% and 9%, respectively, ).

3.4 Treatment and ongoing management

HCPs reported in qualitative interviews (n = 23) that they understood the links between CKD and ASCVD but had limited certainty about the underlying mechanisms driving these links. Results from the quantitative survey (n = 239) revealed that a greater proportion of HCPs believed CKD increases the risk of ASCVD development (76%) than believed ASCVD increases the risk of CKD development (65%). In comparison to HCPs, fewer patients reported strong agreement that each condition serves as a risk factor for the other; only 37% of patient reported they ‘agree’ or ‘completely agree’ that CKD increases the risk of developing CVD, and 41% ‘agree’ or ‘completely agree’ that CVD increases the risk of developing CKD.

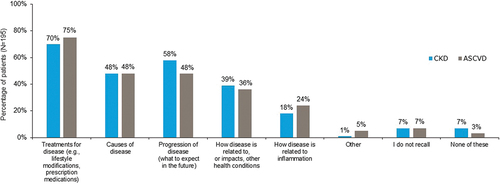

Upon diagnosis, patients reported that their HCP predominantly spoke to them about treatments for the disease (). However, patients and PCPs reported different perceptions of the focal point of recommendations for CKD and ASCVD treatment. PCPs who personally treat CKD or ASCVD most often recalled primarily prescribing or recommending pharmacologic treatments: ACE inhibitors (87% for CKD, 79% for ASCVD); ARBs (85% for CKD, 79% for ASCVD); and statins (84% for ASCVD) or SGLT-2 inhibitors (82% for CKD).

Figure 2. Topics reported by patients to be discussed at diagnosis. ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

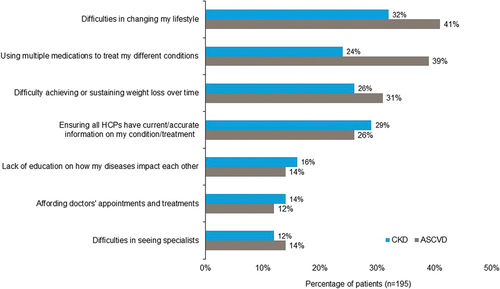

More than two thirds of patients recalled that lifestyle changes were the most common treatment modality they had ever used for these conditions (63% for CKD, 64% for ASCVD), and slightly more than half of patients reported currently using lifestyle changes to treat these conditions (53% for CKD, 56% for ASCVD). Lifestyle changes were also the treatment patients with T2D (n = 73) most commonly recalled ever using; 77% reported that lifestyle modifications were, at some point, used for their ongoing treatment and management of diabetes, and 70% reported currently using lifestyle changes to manage T2D. Patients reported lifestyle changes to be the top challenge in managing both CKD and ASCVD (); those with T2D (n = 73) were even more likely to say they have had difficulty in managing their lifestyle (40% for CKD, 52% for ASCVD).

Figure 3. Patient-reported challenges in managing CKD and ASCVD. ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HCP, health care provider.

When treating patients diagnosed with both CKD and ASCVD, PCPs were more likely than other specialties (44% for CKD, 53% for ASCVD) to measure or test for inflammation directly (most commonly high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hs-CRP]) and consider it in their treatment decision-making.

4. Discussion

CKD and ASCVD have a bidirectional relationship, driven by comorbidities such as obesity, hypertension and diabetes [Citation12,Citation13]. While CKD and ASCVD are traditionally managed by nephrologists and cardiologists, respectively, patients with underlying risk factors are also typically co-managed by PCPs who often serve as the overall care coordinator [Citation2,Citation7]. Patients with more advanced stages of CKD and ASCVD may still need to be under the care of specialists; however, PCPs play an important role in risk reduction through implementing prevention strategies such as monitoring potential drug interactions, educating patients about the disease states and their modifiable risk factors, early diagnosis, and managing therapies to slow disease progression. As coordinated care models have shown, patients who have someone dedicated to bridging gaps in care, assisting with transitions to other providers, and navigating the complexity of the healthcare system tend to have better outcomes [Citation21].

In this study, we surveyed patients with CKD and ASCVD and HCPs who treat patients with CKD and ASCVD to better understand who patients primarily receive their diagnosis from, who is responsible for their treatment and how treatments are conveyed and managed. We found that patient and PCP perception differs in terms of who serves as the coordinator of care for CKD and ASCVD and how each condition is addressed and effectively treated. HCPs surveyed largely agreed that CKD and ASCVD each increase the risk of patients’ development of the other condition, although patients were much less likely to understand these connections. The study suggests opportunities to educate PCPs on the importance of communication to patients about the pathophysiology behind these conditions, which can improve patients’ understanding of the relationship between cardiometabolic risk factors [Citation22,Citation23]. Further, providing PCPs with a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology behind CKD and ASCVD would allow for greater opportunities to discuss symptoms, treatment, and management of CKD and ASCVD with their patients, particularly among those with T2D [Citation4,Citation24,Citation25].

At the time of diagnosis, less than half of patients surveyed recalled discussing the relationship between CKD or ASCVD and other conditions or how their diseases are related to inflammation. This highlights the need to increase awareness of the mechanisms of inflammatory conditions such as CKD, ASCVD and T2D and target risk factors to reduce the burden of these diseases. Risk stratification of patients with CKD and ASCVD may lead to improved outcomes and prevention of kidney damage and/or cardiovascular events [Citation16,Citation26,Citation27]. However, some literature states that modification of many traditional risk factors may prove ineffective due to contribution from novel risk factors such as inflammation [Citation15,Citation23]. This suggests that PCPs would benefit from awareness of a wide range of risk factors that influence CKD and ASCVD and therefore may consult specialists if appropriate. PCPs’ regular engagement with patients at high risk of or having cardiometabolic diseases can help to ensure there are reduced gaps in communication and understanding of next steps in managing their conditions.

To prevent therapeutic inertia, which is defined as the lack of timely adjustment to therapy when a patient’s treatment goals are not met [Citation28], patients should be routinely monitored in the healthcare setting to avoid delays in care. Routine clinical follow-ups ensure that patients understand that value of risk reduction by controlling hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and T2D in lowering the risk of ASCVD and CKD progression [Citation27,Citation29]. Shared decision-making among PCPs and specialists can help reduce inertia commonly found in patients with T2D and cardiorenal complications. Having a clear understanding of who facilitates which specific aspect of treatment can also help to reduce therapeutic inertia commonly found in patients with T2D and cardiorenal complications [Citation25,Citation28].

Our research suggests that PCPs are well positioned to coordinate the multidisciplinary approach to care because they tend to personally diagnose patients with CKD and ASCVD earlier in their diseases and then refer them to specialists, which is especially important for individuals in early stages of CKD but at high risk of cardiovascular complications. Additionally, as the prevalence of CKD and ASCVD (among other conditions) continues to increase, patients may be challenged to manage growing numbers of therapies, including medications, to effectively treat their conditions. PCPs who stand at the center of care coordination may help improve collaboration and continuity of care, thereby avoiding fragmented care for patients.

4.1 Limitations

The quantitative survey tools used in this study were not validated or pilot tested. Patient respondents of our study were predominantly males (65%), white (88%), and well educated (65% held a bachelor’s degree or higher), characteristics which may not be generalizable to the total population of those with CKD and ASCVD. We attempted to fill quotas to receive a representative sample of patients and HCPs; however, respondents to the survey were of a limited range of ethnicities. Further, HCP respondents to the survey were primarily males in suburban practice settings, which also may limit the generalizability of our study to the population of HCPs treating patients with CKD and ASCVD, particularly in rural areas.

Patient respondents to our study had to have access to and familiarity with online surveys, rely on memory of when they were diagnosed with the two conditions, be knowledgeable about their conditions, and be aware of the severity of CKD as assessed by CKD stage. This may represent both recall and selection biases and therefore may limit the generalizability of these conditions to the broader population, particularly for CKD, which can be largely asymptomatic in early stages. Additionally, the survey excluded patients with Stages 1 and 5 CKD and renal failure and those who did not know their CKD stage; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to a patient population with very early or advanced CKD.

Similarly, HCP respondents were asked to estimate the percentage of patients they personally saw or treated with CKD and/or ASCVD, which may represent recall bias and therefore limit the generalizability to a broader population of HCPs.

In asking patients what topics their HCP talked to them about upon CKD and ASCVD diagnosis, respondents overwhelmingly reported that treatment options were primarily discussed. However, the survey combined both prescription and lifestyle-based treatments within this option and did not identify specific types of pharmacologic therapies, which may be useful to better understand treatment receptivity of certain medications among patients. Similarly, the questionnaire did not allow respondents to provide more granular information about specific disease etiologies, such as high cholesterol, hypertension, or uncontrolled diabetes.

Additionally, the research survey was conducted in 2020 and as such, indications for SGLT-2 inhibitors independent of T2D were different than they are currently, particularly in light of recent clinical trial data related to the EMPEROR and DELIVER studies [Citation30,Citation31].

5. Conclusion

Our findings shed light on important aspects regarding the coordination of care for patients with both CKD and ASCVD. It is evident that many patients do not consider their PCP as the primary coordinator of care for these conditions. Additionally, there exists a notable disconnect between the perceptions of HCPs and patients regarding the topics being discussed during healthcare encounters.

These insights emphasize the urgent need for improved communication, patient education and care coordination, which can be optimally facilitated by PCPs. By assuming a more proactive role in coordinating care, especially for patients with multiple chronic comorbidities, PCPs can bridge the gap between patients and other HCPs, ensuring consistent and effective communication. Furthermore, enhanced patient education about cardiometabolic conditions, their risk factors and management can empower individuals to actively participate in their own healthcare decisions, which may help remedy some challenges patients experience with their conditions.

In summary, our study underscores the importance of recognizing the optimal role of PCPs in coordinating care for patients with CKD and ASCVD. Coordinated care with timely and clear identification of disease states is central to the intervention of cardiorenal conditions. The need for increased discussion of the gaps in diagnosis and patient awareness are evident in this research. Addressing the existing gaps through better patient education and cardiorenal-metabolic care coordination has the potential to improve outcomes and enhance the overall quality of care provided.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

E Miller serves on the Speakers Bureau and as an Advisory Board member for Eli Lilly, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Abbott, Bayer and Research Abbott. M Cavender reports research support to his institution for studies in which he is the principal investigator from Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, CSL Behring; consulting fees from Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Medtronic, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Zoll. S Mehanna and R Ochsner are employees of, and shareholders in, Novo Nordisk, Inc. At the time of the study, T Namvar was a health economics and outcomes research fellow with Novo Nordisk, Inc. and Rutgers University. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (585.7 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephanie Burkhead of KJT Group, Inc., Rochester, NY for providing medical writing support, which was funded by Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, NJ in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Eden Miller, upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2023.2256209

Additional information

Funding

References

- U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2022.

- Bakris G. Use of SGLT-2 inhibitors to treat chronic kidney disease in primary care. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:S88–S93. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0389

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/publications-resources/ckd-national-facts.html

- de Boer IH, Khunti K, Sadusky T, et al. Diabetes management in Chronic kidney disease: a consensus report by the American diabetes Association (ADA) and kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO). Diabetes Care. 2022 Dec 1;45(12):3075–3090. doi: 10.2337/dci22-0027

- Garg D, Naugler C, Bhella V, et al. Chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes: does an abnormal urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio need to be retested? Can Fam Physician. 2018 Oct;64(10):e446–e452.

- Wang M, Peter SS, Chu CD, et al. Analysis of specialty nephrology care among patients with Chronic kidney disease and high risk of disease progression. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8):e2225797–e2225797. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.25797

- Mathew RO, Bangalore S, Lavelle MP, et al. Diagnosis and management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease: a review. Kidney Int. 2017;91(4):797–807. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.049

- Rosenblit P. Extreme atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk recognition. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(8):1–20. doi: 10.1007/s11892-019-1178-6

- Sajja A, Li H-F, Spinelli KJ, et al. A simplified approach to identification of risk status in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2021 Sep 01;7:100187.

- Vasan RS, Enserro DM, Xanthakis V, et al. Temporal trends in the remaining lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease among middle-aged adults across 6 decades: the Framingham study. Circulation. 2022;145(17):1324–1338. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.057889

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of cardiology/American heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(18):e895–e1032.

- Amdur RL, Feldman HI, Dominic EA, et al. Use of measures of inflammation and kidney function for prediction of atherosclerotic vascular disease events and death in patients with CKD: findings from the CRIC study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019 Mar;73(3):344–353. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.09.012

- Amdur RL, Feldman HI, Gupta J, et al. Inflammation and progression of CKD: the CRIC study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 Sep 7;11(9):1546–1556. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13121215

- Bajaj A, Xie D, Cedillo-Couvert E, et al. Lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in persons with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019 Jun;73(6):827–836. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.11.010

- Sarnak MJ, Amann K, Bangalore S, et al. Chronic kidney disease and coronary artery disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Oct 8;74(14):1823–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.1017

- Poudel B, Rosenson RS, Bittner V, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events in adults with CKD taking a moderate- or high-intensity statin: the Chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Kidney Med. 2021 Sep;3(5):722–731.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2021.04.008

- Eknoyan G, Lameire N, Eckardt K, et al. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013 Jan 1;3(1):5–14.

- Chen TK, Knicely DH, Grams ME. Chronic kidney disease diagnosis and management. JAMA. 2019;322(13):1294–1304. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.14745

- Pagidipati NJ, Nelson AJ, Kaltenbach LA, et al. Coordinated care to optimize cardiovascular preventive therapies in type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;329(15):1261–1270. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.2854

- Stellefson M, Dipnarine K, Stopka C. The chronic care model and diabetes management in US primary care settings: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E26. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120180

- Duan-Porter W, Ullman K, Majeski B, et al. Care coordination models and tools: a systematic review and key informant interviews [internet]. (WA) D.C: Department of Veteran Affairs; 2020.

- Wong ND, Budoff MJ, Ferdinand K, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk assessment: an American Society for Preventive cardiology clinical practice statement. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2022 Jun;10:100335.

- Gregg LP, Hedayati SS. Management of traditional cardiovascular risk factors in CKD: what are the data? Am J Kidney Dis. 2018 Nov;72(5):728–744. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.12.007

- Tuttle KR, Jones CR, Daratha KB, et al. Incidence of Chronic kidney disease among adults with diabetes, 2015-2020. N Engl J Med. 2022 Oct 13;387(15):1430–1431. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2207018

- Kushner PR, Cavender MA, Mende CW. Role of primary care clinicians in the management of patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiorenal diseases. Clin Diabetes. 2022 Fall;40(4):401–412. doi: 10.2337/cd21-0119.

- Branch M, German C, Bertoni A, et al. Incremental risk of cardiovascular disease and/or chronic kidney disease for future ASCVD and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: ACCORD trial. J Diabetes Complications. 2019 Jul;33(7):468–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2019.04.004

- Chaudhry RI, Mathew RO, Sidhu MS, et al. Detection of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in patients with advanced Chronic kidney disease in the cardiology and nephrology communities. Cardiorenal Med. 2018;8(4):285–295. doi: 10.1159/000490768

- American Diabetes Association. Getting to goal: overcoming therapeutic inertia in diabetes care; 2022. [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.therapeuticinertia.diabetes.org/about-therapeutic-inertia

- Khatib R, Glowacki N, Lauffenburger J, et al. Race/Ethnic differences in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors among patients with hypertension: analysis from 143 primary care clinics. Am J Hypertens. 2021;34(9):948–955. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpab053

- Packer M. 2020. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 383(15):1413–1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022190

- Solomon SD. 2022. Dapagliflozin in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 387(12):1089–1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206286