Abstract

Since the U.S. Embassy in Beijing placed an air quality sensor on its roof and began publishing the results on Twitter in 2008, air quality has gained widespread attention on Chinese microblogs. When the Chinese government introduced new air quality standards in 2012, some hailed this as a victory for Chinese microbloggers, signifying the emergence of social media as a democratizing force leading to greater citizen power. Using a representative sample of microblog posts collected from October 2012 to June 2013 on the topic of air pollution, as well as contextual information from a variety of sources, we examine how the government, companies, nongovernmental organizations, and individuals approach the Chinese social media landscape. We find that although microblogs are capable of empowering citizens to advance an environmental cause, social media have also been increasingly employed by the government as a tool for social monitoring and control and by companies as a platform for profiting from air pollution.

自从2008年美国驻北京大使馆在屋顶安置了一个空气品质感应器,并开始在推特上发表侦测结果以来,空气品质便在中国的微博得到广泛的关注。当中国政府于2012年引进新的空气品质标准时,部分人士欢呼此为中国微博客的胜利,强调新兴的社群媒体做为引领更强大的公民力量的民主化趋势。我们运用搜集自2012年十月至2013年六月中,在微博以空气污染为主题所发表的文章之代表性案例,以及不同来源的脉络化信息,检视政府、企业、非政府组织与个人,如何应对中国的社群媒体地景。我们发现,儘管微博能够对公民进行培力,以促进环境保育的目标,社群媒体却同时逐渐被政府使用作为社会监控的工具,并被企业用来作为从空气污染中获利的平台。

Desde cuando la Embajada de los EE.UU. en Beijing colocó en su techo un sensor de calidad del aire y empezó a publicar los registros en Twitter en 2008, la calidad del aire ha ganado vasta atención en los microblog chinos. Cuando el gobierno chino presentó nuevos estándares sobre calidad del aire en 2012, algunos saludaron esta acción como una victoria de los microblogueros chinos, viéndola como el surgimiento de los medios sociales como una fuerza democratizadora que apuntaba hacia un mayor empoderamiento ciudadano. Mediante el uso de una muestra representativa de correos de las microblog recogida entre octubre de 2012 y junio de 2013 sobre el tópico de la polución aérea, lo mismo que información contextual obtenida de una variedad de fuentes, examinamos la forma como abocan el paisaje de los medios sociales chinos el gobierno, las compañías, las organizaciones no gubernamentales y los individuos. Descubrimos que si bien las microblog son capaces de empoderar a los ciudadanos para promover una causa ambiental, los medios sociales también han sido crecientemente empleados por el gobierno como una herramienta de monitoreo y control, y por las compañías como una plataforma para beneficiarse con el tema de la polución del aire.

Years of planning, billions of dollars, and untold hours of labor went into the three-week-long Summer Olympics that took place in Beijing, China, in August 2008. Monumental stadiums were constructed, lines were added to the subway, and a terminal was added to the airport; even the sky was made ready. At the urging of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), the Chinese government shut down hundreds of factories, power plants, and construction sites within a 150-km radius of Beijing; removed millions of vehicles from the road; planted trees to prevent sandstorms; and seeded clouds to change the weather. These costly efforts resulted in a significant reduction in air pollution in Beijing (Rich et al. Citation2012). The emissions reduction coincided with a drop in biomarkers of cardiovascular disease among young adults, which increased again when the games and air pollution reduction measures ended (Rich et al. Citation2012). Although the measures taken to prepare for the 2008 Summer Olympics cleared the skies and temporarily improved health, they were short-lived. In the years since the Olympics, air pollution has worsened, but Chinese citizens have also become more vocal about the issue than ever before, particularly using the medium of microblogs. This article examines the perplexing role of social media in the debate over air pollution in Chinese cities.

For decades, the Chinese government blamed hazy days on fog or dust. Publicly released government air pollution reports completely ignored certain pollutants such as PM2.5, airborne particulate matter 2.5 micrometers or less in diameter, which because of its small size can penetrate deep into the cardiovascular and respiratory systems (Rich et al. Citation2012). Starting in 2008, when the U.S. Embassy in Beijing began publishing air quality data on its official Twitter feed, PM2.5 received more attention on Chinese social media as microbloggers reposted and commented on the U.S. Embassy numbers, much to the consternation of Chinese officials. In 2012, the central government adopted new national air pollution standards, and by early 2013 the air pollution problem led to unprecedented political transparency as municipal governments began to release PM2.5 readings and the news media began to more freely report on the issue. These developments have been hailed by some (Stout Citation2013; Wong Citation2013) as a “bottom-up” victory for ordinary people.

This article problematizes the role of the social media landscape in the debate over air pollution as a field for the creation and contestation of environmental knowledge and narratives. We examine the multiple ways in which ideas about air pollution are produced and contested by different users of Sina Weibo, China's most popular microblogging web site. Taking a critical political ecology approach, we examine the intersection of the socioecological process of urbanization, its attendant environmental and social problems, the neoliberalization of Chinese environmental governance, and the role of social media in the production and contestation of environmental knowledge and narratives. Using the case study of the debate over PM2.5 that has played out largely on microblogs, we discuss whether social media represent an effective (or ineffective), just (or unjust) new form of citizen power in China and how they contribute to or detract from the likelihood of adaptation and mitigation.

Social Media, Unfair Air, and China's Environmental Governance

Social Media in China: A “Liberation Technology?”

More than 500 million people use the Internet in China, and more than 400 million of them use Sina Weibo.Footnote Some herald the Internet and microblogs as a possible step toward democratic civil society in China (Hu Citation2010), but an elaborate and robust system of censorship enables the state to use the Internet and microblogs for its own purposes, privileging the creation of certain types of knowledge by certain types of people. Scholars disagree over whether social media in China will act as what Diamond (Citation2012) calls a “liberation technology,” perhaps bringing about more open, democratic policy debates, or will instead contribute to a broadening and deepening of government control over public discourse.

Xiao (Citation2011) argues that the Internet, although subject to government censorship, has created a new class of “netizens” engaged in a relatively open “cyberpolitics” with real-world results. Censorship remains a formidable force on the Chinese Internet (Warf Citation2010), but Xiao points to the clever ways in which Chinese web users have resisted efforts at censorship, such as the creation of the “grass mud horse.”Footnote Xiao argues that the Chinese state has adapted to the Internet by becoming more responsive to citizens and allowing greater citizen participation in decision making.

On the other hand, MacKinnon (Citation2012) argues that what has emerged out of the growth of the Internet in China is a repressive “networked authoritarianism.” The Chinese government has adapted to the spread of the Internet and social media, she argues, by using it as a surveillance tool to predict and prevent or rechannel protests. This capability was demonstrated in May 2013 when officials in Chengdu, having caught wind of the details of a protest against the construction of an oil refinery through social media and text messages, altered the work week (making Saturday, 4 May, a workday) and deploying a heavy police and paramilitary presence near the site of the planned protest (Lim Citation2013). Social media, which allowed organizers to easily communicate the details of the protest to a wide audience, also made it easy for the government to prevent the protest and identify key organizers through their positions in online networks.

Due to the socially and spatially uneven distribution of Internet access and technological literacy in China, many people are excluded from these networks (Xiao Citation2011). Weibo users are young—about 92 percent were born since 1980—and highly educated; more than 70 percent of Weibo users have received higher education (Sina Weibo 2013), compared to less than 9 percent of the overall Chinese population (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2011). Weibo has slightly more female than male users, but male users are more likely to have larger numbers of followers (Sun Citation2013). Moreover, microblog posts are censored at widely different rates in different regions: 53 percent in Tibet and Qinghai, compared to 12 percent in the eastern provinces and cities (Bamman, O’Connor, and Smith 2012). China's Internet censorship likewise takes several different forms. A large number of outside web sites and networks are blocked by the “Great Firewall,” search terms are screened, and chat and microblog posts are selectively deleted. In many cases, censorship involves detaining or threatening to detain outspoken bloggers. Internet companies are held responsible for content posted on their sites, obligating them to carry out their own censorship activities alongside those of the government (Xiao Citation2011; Bamman, O’Connor, and Smith 2012; Eaves 2012; Magistad Citation2012). But censorship is not about completely preventing the spread of any news or knowledge or even government criticism. Many recent cases, such as the discussion of the Bo Xilai scandal on microblogs, show how the government will allow many online debates to continue more or less unfettered as long as these online discussions are not translated into organized political actions (King, Pan, and Roberts 2013).

Political Ecology of Urban Air Pollution

In 2011, China's urban population outnumbered its rural population for the first time. The United States passed this threshold in 1920 and the world as a whole is estimated to have passed it in 2007. As an increasing proportion of the world's population lives in cities, scholars have engaged more deeply with urbanization and society's relationship with nature, in part through the interdisciplinary field of urban political ecology (UPE; Cronon Citation1991; Heynen, Kaika, and Swyngedouw 2006; Cook and Swyngedouw Citation2012). With roots in Marxist analysis and historical materialism, UPE rejects the notion that cities are not natural places and investigates urbanization as a socioecological process taking place within a context of uneven power structures. UPE examines the role of power and politics in the production of “urban natures,” investigating “who produces what kind of socio-ecological configurations for whom” (Heynen, Kaika, and Swyngedouw 2006, 2).

Although much of the political ecology literature has focused on natural resources such as water, minerals, and land, scholars have recently turned their attention to how power relations manifest in the air (Harper Citation2004; Véron Citation2006; Buzzelli Citation2008; Whitehead Citation2009). Much air pollution research focuses on the outdoors, but Biehler and Simon (Citation2011) have called on geographers to examine the indoors as political–ecological spaces that are both socially produced and inextricably linked with the outdoors. Although outdoor air is difficult to capture and commodify at the human scale, air conditioning and filtration can produce clean air indoors, for a price.

Writing about Houston, Texas, Harper (Citation2004, 309) argues that air pollution is relatively egalitarian: “All Americans, regardless of social standing, breathe polluted air; and a number of middle-income white communities … are near freeways and polluting industries.” Indoor air filtration technologies, however, have the potential to counteract the ostensibly nondiscriminatory behavior of air pollution. Those who can afford to live in apartments, shop in malls, and drive in vehicles equipped with this technology consume clean air (and cardiovascular and respiratory health) as a luxury good, especially when we consider the fact that we as humans spend only 5 to 15 percent of our entire life outdoors (Myers and Maynard Citation2005). Paradoxically, although severe air pollution has been shown to take an economic toll of possibly hundreds of millions of dollars (Schmitz Citation2013), it creates opportunities for profit for a burgeoning filtration industry, real estate developers, and others. Companies from Haier and 3M to Geely-Volvo and Pond's have moved quickly to capitalize on the air pollution crisis.

China's Environmental Governance

Scholars have recently noted a neoliberal turn in China's environmental governance characterized in part by the emergence of “ecological modernization” as a dominant state narrative (Carter and Mol Citation2006; Yeh Citation2009). This narrative “privileges entrepreneurship and market dynamics in creating environmental solutions” (Yeh Citation2009, 884). Yeh argues that Chinese ecological modernization favors technical solutions over political innovations. This bias is evident in the Chinese state's policies toward PM2.5. Since more openly acknowledging the existence of the air pollution problem in 2012, the state has undertaken extensive air pollution monitoring efforts similar to but technologically far more advanced than London's twentieth-century urban smoke observers (Whitehead Citation2009).

The Chinese state contends that the air pollution problem can be solved through the adoption of new technologies rather than any fundamental shift in China's political or economic structures, treating air pollution as a scientific problem, not a political problem. The state's use of social media to disseminate its deluge of air pollution data (and drown out alternative data and opinions through censorship) can be thought of as a kind of technologically mediated political innovation, albeit one that is meant to maintain a political and social status quo.

Grumbine (Citation2007) argues that China's rise is driven by government policy decisions, globalization, and the scale of development and is constrained by environmental degradation, political instability, coal and oil consumption, and carbon dioxide emissions. We argue that through its adoption of a narrative of ecological modernization, China's leadership is trying to turn environmental degradation to their advantage by using the air pollution problem to advance a regime of urban atmospheric governance that contributes to the political and social status quo. Yeh (Citation2009, 885) reminds us that “environmental projects are always more than environmental projects.” Through narratives such as ecological modernization, China's leaders are responding to environmental problems in ways that strengthen their continued rule. According to Wang (Citation2013), the central government has turned to cadre evaluation as a way to reduce air pollution, devolving responsibility for pollution reduction to governors, mayors, and state-owned enterprises, while also demanding continued economic growth. Wang argues that this policy is designed to limit risks to the regime's hold on power, using environmental protection to further the goals of economic growth and social stability. This form of accountability encourages local leaders to bend the rules by falsifying pollution numbers or concealing the operation of major pollution sources (Ma Citation2011; Wang Citation2013). Citizen science and crowd mapping could offer new powerful ways to rectify these problems in China's environmental governance (Sui 2013b).

In summary, by situating this article in the broader context of recent research on social media, UPE, and environmental governance in China, we aim to shed light on the ways in which multiple actors use social media to tackle the air pollution issue in China. We argue that although it is encouraging that a peaceful outpouring of clearly articulated public opinion over social media helped prompt an authoritarian regime to change national environmental laws, we should be mindful that the debate over air pollution and the regime's response is more than a straightforward victory for social media as a liberation technology.

Chinese Urban Air Pollution and Social Media: A Case Study

Air pollution is closely associated with China's changing position within the global economic system. The main sources of air pollution in Chinese cities include industry, construction, vehicles, and household pollution (Hao and Wang 2005). Polluting industries come to China in part through the process of international dirty industry migration (DIM), which means that some of the pollution is essentially being offshored from the United States and other countries that import manufactured goods from China (Mehra and Das Citation2007; Lu Citation2008; Sui Citation2013a). Among air pollutants, airborne particulate matter (PM) can be especially harmful, contributing to cardiopulmonary disease (Kappos Citation2011) and decreased life expectancy (Chen et al. Citation2013). The smaller the particle, the more harmful it is. Partially for this reason, PM2.5 was quickly able to capture the attention of Chinese microbloggers.

The recent social media debate over PM2.5 in China was spurred in part by the decision in August 2008 of the U.S. Embassy in Beijing to install an air quality monitor on its rooftop and publish real-time readings on Twitter every hour (). At the time, Beijing's Environmental Protection Bureau (EPB) did not widely collect or publicize PM2.5 levels but instead based its air quality announcements on other pollutants, such as PM10.Footnote In 2009, Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) representatives met with U.S. State Department officials to protest the publication of the readings. According to a leaked State Department cable, MFA representatives complained that the data released on the Twitter feed “conflicted” with “official” Beijing EPB data, causing “confusion” and “undesirable ‘social consequences’ among the Chinese public” (U.S. State Department 2009).

Figure 1 PM2.5 monitoring device mounted on the roof of the U.S. Embassy in Beijing (Source: Reuters/U.S. Embassy Press Office).

Undesirable social consequences and confusion did indeed ensue, as Chinese microbloggers took notice of the disparity between the U.S. Twitter feed and official EPB assessments. During a period in 2011 when PM2.5 readings went off the chart (beyond index) of the U.S. Embassy Twitter feed, key opinion leaders on Weibo, including Pan Shiyi, a prominent real estate developer, organized an informal vote on Weibo calling for stricter air quality standards.

In January 2012, the Beijing EPB started reporting PM2.5 levels, and on 1 March 2012, the State Council adopted new nationwide air quality standards that included PM2.5 for the first time. Official state media reported the new standards as a victory for microbloggers under the headline “PM2.5 in air quality standards, positive response to net campaign” (Xinhua Citation2012). The debate over air pollution in China is ongoing. In January 2013, several days of severe air pollution again prompted a social media outcry but—for the first time—also garnered significant coverage in state media outlets and relatively open discussion by officials. Off-the-chart pollution levels were widely reported in Chinese and Western news outlets (Wong Citation2013). In January 2014, the government announced that it would require major polluters to begin releasing near-real-time air quality measurements.

In the period of a few years, air pollution went from a taboo subject with data either not collected or shrouded in secrecy to a sensitive but widely discussed issue. Near-real-time air pollution readings from a dizzying array of sources are now available to technologically savvy Chinese citizens. The rapidly shifting debate about urban air pollution in China has changed the way the government, corporations, and citizens talk about, think about, and adapt to the polluted air.

The central role of microblogs in the air pollution debate has prompted hopes that social media can act as a stand-in for a democratic process—a kind of government-by-crowd-sourcing—and that the social media landscape could be rich territory for occupation by activists. To assess these possibilities, we took a closer look at the air pollution debate as it unfolded on Sina Weibo, asking who is posting (and where), what they are posting, who gets the most attention, and to what extent these answers align with an “even” social media landscape conducive to open, democratic discussions, or an “uneven” authoritarian landscape.

Data and Methods

We draw on a number of sources to examine the social media–driven debate over air pollution in Chinese cities, including Weibo posts, collected from October 2012 to June 2013; official and unofficial media coverage in China; advertisements for various air pollution–related products; diplomatic communications; government reports; and public statements made by officials.

Methodologically, this article is tied to the growing literature on using mapping and analyzing social media data (Tsou and Leitner Citation2013; Xu, Wong, and Yang 2013). The primary object of our analysis is the debate over air pollution on Weibo. Using a purpose-built crawler, we collected about 250,000 statuses, reposts and comments from about 127,000 Weibo users from October 2012 through June 2013Footnote with a six-day gap in January 2013. Most social media sites have an application programming interface (API) for the purpose of collecting an unbiased subset of data. We employed a heuristic procedure, first collecting sample posts to identify key terms relevant to the topic and then using those key terms to collect our data set. The terms we used to collect our sample were PM2.5, PM, haze, air pollution, xikeliwu,Footnote and air quality.

Using the Sina Weibo search topic API, our database of microblogs containing these terms was continuously updated. The data were then cleaned and geocoded. One of our primary analytical tools was to measure the frequency of different terms in our data set. Unlike English, words in Chinese are not separated by spaces, so calculating terms’ frequencies first required word segmentation analysis. To accomplish this, we integrated ICTCLAS (Zhang et al. Citation2003)—a popular Chinese-language analytical module—into the Weibo crawler.

To create a spatial–temporal model of the data, it was necessary to geocode the posts. Posts from Global Positioning System (GPS)-enabled devices already included latitude and longitude coordinates. To extrapolate approximate location from nongeocoded posts, the crawler took the location information from the user profile, and attempted to find corresponding coordinates first in the gazetteer database and, if unsuccessful, in pygeocoder, a Python library that makes use of Google's geocoding functionality. Next, the data were checked for semantic and logic areas. Using this process, the sample was collected from Weibo, cleaned, geocoded, and built into a database. illustrates this process.

Results and Discussion

The Chinese central government (eventually) responded to the PM2.5 debate by acknowledging an air pollution problem, setting new air pollution guidelines, and introducing new enforcement mechanisms. Although many (including, notably, the Chinese government) hail these steps as a victory for microbloggers, bolstering the hopes that Sina Weibo and other social media will become democratizing “liberation technologies” in China, our analysis of the data also show how companies, the government, and a few opinion leaders have shaped the discussion along narrow—and profitable—lines. The most influential users in the debate were almost entirely comprised of government sources, companies, or famous individuals.

We first address the question of who participated in the social media debate and where they were. One way of assessing the extent to which a social media debate reflects the sentiment of the general public is to see whether the participants in the debate roughly match the general public demographically. As discussed earlier, Sina Weibo users tend to be younger, more educated, and more affluent than the Chinese population as a whole. Our analysis shows that participants in this particular debate are even more out of line with the Chinese population than the general pool of Sina Weibo users.

Mao Zedong famously declared that Chinese women “hold up half the sky,” but our analysis shows that they are underrepresented in the social media debate over the pollutants in that sky. The underrepresentation of women in this debate is particularly significant in a country where only about 10 percent of provincial party elites are female (Su Citation2006) and female legislators attending the eighteenth party congress were described by state media as “beautiful scenery” (People's Daily 2012). Female users are estimated to slightly outnumber male users of Sina Weibo (Sun Citation2013), but our data show that the opposite is true for participants in this debate; female users account for only 46.5 percent of users participating in the air pollution debate. The disparities only get more extreme when looking at the most influential users measured by weighted in degree, a measure of users’ importance to a debate.Footnote

We found that the top 1 percent of users in our sample (measured by weighted in degree), numbering 1,270, account for over 80 percent of the total weighted in degree. The top 0.01 percent (127 out of a pool of about 127,000 users) account for over 60 percent of the weighted in degree. In other words, 127 users hold about 60 percent of the influence among a group of 127,000. This elite group deserves closer scrutiny. shows the attributes of the top twenty users—the elite of the elite.

Table 1 Attributes of the top 20 most influential users

We found that most of the users with the highest weighted in degree were not individuals but were government agencies, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and companies. Of the top 0.01 percent of users, just 20 percent are individuals. At the time of writing, all accounts on Weibo—including those not associated with an individual person—are required to identify as either male or female. Of the top 0.01 percent of users, 56 percent identified themselves as male. Among the subgroups (government, company, NGO, or individual), slight majorities of companies and NGOs identified as female (51 percent and 52 percent, respectively), whereas 64 percent of the individual accounts and nearly 90 percent of the government accounts identified themselves as male.

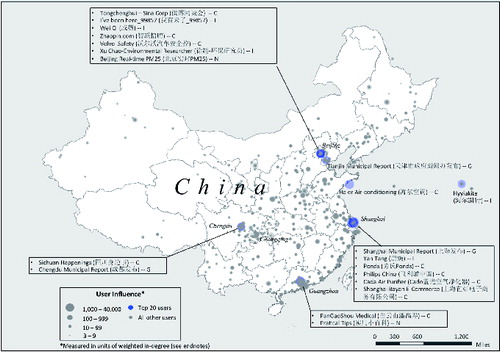

By geocoding the Sina Weibo users, we are able to map out the geographical distribution of the top twenty users and their level of influence by weighted in degree (). Four urban clusters clearly dominated in the debate. Not surprisingly, three (Beijing/Tianjin, Shanghai, and Guangzhou/Shenzhen) out of the four urban clusters are located in the eastern, economically more prosperous region of China. Only one of these urban clusters—Chengdu—is located in the Western interior, showing that concerns about air quality are not simply confined to the more crowded east. Although these four clusters are dominant in the debate, air pollution is increasingly becoming an issue in smaller cities. reveals that concerns over air quality are spiraling down the urban hierarchy, as evidenced by the increasing proliferation of discussions on air pollution in second and even third-tier cities.

Figure 3 Spatial distribution of the top twenty Sina Weibo users in the air pollution debate measured by weighted in degree, a measure of how influential a user's posts are (generated by Wordle). Note: C = company, G = government; I = individual; N = nongovernmental organizations.

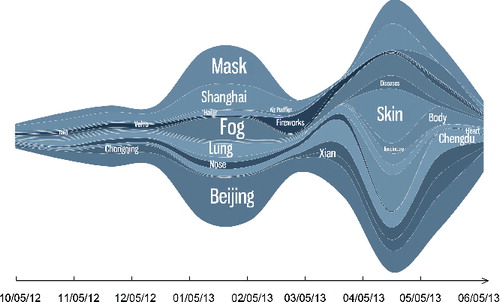

We now turn our attention to the content users posted on Weibo. In general, the social media debate emphasizes adaptation and steps that individuals can take (e.g., buying an air filter or staying indoors), deemphasizing steps that society generally and the government specifically could take (e.g., new petroleum standards, shutting down coal plants, or paying for air pollution–related health care). A word cloud () gives a basic overview of some of the main terms appearing in posts, and a stream graph () gives a sense of the changing magnitude of posts over time as well as the changing top terms during the period of our study.

Figure 4 This word cloud shows the top 150 high-frequency terms from our data set generated by Wordle.

Figure 5 A stream graph shows the changing magnitude of number of posts as well as the changing top terms over the time period of our study.

Although the social media debate contributed to new government air quality standards, ostensibly benefiting everyone equally, these standards have yet to produce meaningful reductions in pollution levels. At the same time, companies have shrewdly used social media to advertise products for adaptation. Although the goal of many participants in the Sina Weibo debate might have been to achieve cleaner air for all, the result thus far has been an increasingly wide gap between those few who can afford luxury adaptation technologies and the vast majority of the Chinese population who cannot.

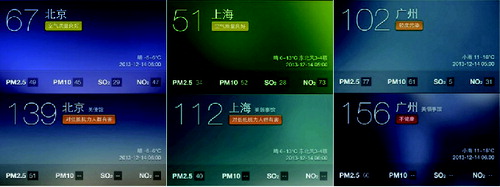

What is contained in some of the most influential posts? Periodically, Pan Shiyi—with 16.6 million followers and counting—posts the official Chinese and U.S. air quality readings for various cities (). He also frequently posts about going for jogs in the park (when the air is clear enough) and installing top-of-the-line air filtration systems in his company's buildings. With his posts, Pan is perpetuating an environmental imaginary in which clean air and a healthy lifestyle are consumable goods. As a celebrity real estate developer, he has every reason to do this; it increases the value of his company's buildings as well as his own cachet. Pan is not alone in the endeavor of commodifying clean air. Chinese companies such as Haier and multinationals such as 3M advertise air filtration systems on Weibo (). Haier advertises a basic model for 9,999 Yuan, which is slightly less than half the median per capita income for urban residents in 2011 (23,979 Yuan) and surpasses the median per capita income of rural residents (6,977 Yuan) in the same year (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2012).

Figure 6 A sample of Pan Shiyi's Weibo posts dated 14 December 2013 showing the composite air quality index (from left to right) of Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. The official Chinese numbers (top) are juxtaposed with the U.S. Embassy or Consulate readings (bottom) (Source: Sina Weibo).

Figure 7 Air filtration system advertisement by Haier on Weibo. (The advertisement states that “using the most advanced technology for the filtration of PM2.5,” Haier's product will enable customers to “breathe healthier air.”) (Source: Sina Weibo).

Companies that sell air filters and real estate developers who sell buildings with filtered air are obvious candidates for posting air pollution advertisements in the microblogosphere, but they are hardly alone in the rush to profit from pollution. Pond's, a brand of beauty and hygiene products owned by international corporation Unilever, was quick to bring a line of PM2.5-fighting beauty products to market, advertised in part by the personal Weibo accounts of celebrity actresses such as Tang Yan (唐嫣). Tang Yan and a handful of other users were in large part responsible for the sudden increase in occurrences of the word skin (皮肤) during April and May 2013 (). During April and May, among the top thirty posts including the word skin receiving the most reposts, twenty-five made mention of Pond's. These twenty-five posts were reposted a total of 138 times. This kind of sudden popularity for a term is suggestive of the presence of the “online water army” (网络水军), a group of Internet users paid by companies to promote their products. Our analysis showed that companies significantly influenced the popularity of certain terms with or without the water army. For instance, Samsung contributed to the popularity of the term fog during the first few months of 2013 () by using it in advertisements for its air filters. Advertising through social media, as opposed to web site banner ads or those on the side of a bus, means that companies can rely on users—whether paid “water army” members or regular people—to spread their message for them to their online acquaintances. Our data show that companies have shrewdly capitalized on the social media debate about air pollution to gain popularity and sell their products.

Meanwhile, the Chinese government has used social media to give the impression that the air pollution problem can be solved mostly or entirely through technology and without sacrificing economic growth. Government accounts are largely responsible for the overall significance of terms such as weather, data, and density (). This is part of the Chinese state's efforts to make air pollution a scientific rather than a political problem.

Breathing clean air is the privilege of those who can afford to live, work, shop, and drive in buildings and vehicles equipped with air filtration technology. This is not merely a matter of comfort but one of life and death. In a study carried out in Shanghai, Huang et al. (2009) found that low visibility, which is highly correlated with increased concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10, is significantly associated with elevated death rates from cardiovascular disease on the time scale of just one day. Guo et al. (Citation2010) found that outdoor air pollution has an hour-to-hour effect on indoor air pollution levels, meaning that staying inside (without air filtration) provides little respite from pollutants, to say nothing of those commuting by foot or bicycle. It is likely that it will be several decades before clean air is abundant enough in Chinese cities to be enjoyed by those who cannot afford prime real estate or air filtration systems. In a Sina Weibo post from 16 January 2014, Pan Shiyi stated the obvious: “The outdoor air pollution problem cannot be completely resolved for the time being. At least we can maintain the indoor air quality to a higher standard.” This prescription is only available to the class of people who can afford expensive indoor air filtration technology; Pan's suggestion is simply out of reach for most Chinese citizens.

Like PM2.5, power relations flow through spaces and buildings occupied by different people (Biehler and Simon Citation2011), in turn producing atmospheric subjects (Whitehead Citation2009). Chinese city-dwellers are sorted into the categories of those who can afford to adapt to air pollution and those who cannot. The Communist party recognized that this inequality could threaten its rule. In a 2009 meeting with U.S. diplomats to lodge a diplomatic complaint about the U.S. Embassy posting air quality data on its Twitter feed, Chinese officials expressed concern about the “undesirable social consequences” that could arise if the air pollution issue remained unresolved (U.S. State Department 2009). Although the party-state attempted for several years to end the debate by grossly understating the extent of the air pollution, the persistence of microblog users and the continued presence of the U.S. Embassy Twitter feed made this difficult. The government could shut down Sina Weibo tomorrow,Footnote but their goal is to channel the public expression of netizens, not eliminate it altogether. Instead of banning it, the government seeks to use social media as a tool for keeping track of public opinion and communicating with the public (Hu Citation2010). This does not mean that the government is embracing a democratic medium or a new “online politics.” Hu (2011) writes, “The online discussion of politics and democratic politics are two separate things. And online discussion of politics will not automatically eliminate the difficulties in communication that we see in our politics today.”

Chinese blogger Jing Zhao (aka Michael Anti), as paraphrased by Eaves (2012), argues that the central government uses social media as a “safety valve” to “give people the sense that they can complain about issues” without actually engaging in collective actions that could threaten the central authority of the state. Allowing open discussion of some issues might be as important to the party-state as preventing discussion of other issues. Nonetheless, to the extent that the government fears that it cannot control a certain issue because of its proliferation on microblogs, it might take substantive action on the issue rather than continue to sideline it through propaganda and censorship. We argue that this is the kind of calculation the government made in the way it eventually responded to the debate over air pollution. Rather than allowing pressure from microblogs to threaten its legitimacy, the party-state shrewdly occupied the social media landscape (shoulder to shoulder with companies) to advance its own environmental narrative.

Conclusions

The goal of this article is to assess the role of social media as a liberation technology in the debate over urban air pollution in China. Contextualized by earlier literature on social media, political ecology, and environmental governance in China, we conducted a case study on the social media debate on air pollution in Chinese cities from October 2012 to June 2013. By identifying who is participating in the debate, what they are posting about, and who the most influential users are, we were able to trace the broad trends in the air pollution debate as it took place on Sina Weibo. We found that companies (seeking profit) and the government (seeking social stability) play a disproportionate role in the social media debate. Although this case study shows the clear potential of social media as liberation technologies in China, their current limitations make them unrepresentative of the population in general and highly uneven along lines of gender, class, and location.

It is unlikely that the new air quality standards will result in significant mitigation in the short term as evidenced by recent headlines that more major cities all over China have been hit by heavy smog (Xinhua 2013), with devastating impacts ranging from local school closures to disabled security cameras (Simpson Citation2013) and perhaps even harmful impacts on sperm quality (Phillips Citation2013). According to Wu Dui, an official in the Guangdong Meteorological agency, Chinese city dwellers can expect to breathe heavily polluted air for “another 20–30 years” (Watts Citation2012). Air pollution mitigation will likely take a slow, incremental path: Cleaner technologies will likely be gradually introduced, and dirty industries will eventually migrate away from cities and perhaps to other countries as environmental regulations are more evenly applied throughout China. In the meanwhile, those who can adapt by consuming clean air as a luxury good will be adding (perhaps negligibly but still symbolically) to energy demand and thus emissions by running their filtration systems. It is unlikely that Chinese urban dwellers will ever again see anything like the drastic, short-lived pollution mitigation strategies that produced blue(ish) skies for the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

Our research shows that microblogs are an especially uneven medium for the creation and contestation of environmental knowledge and narratives. As a stand-in for a democratic political system, social media disenfranchise anyone without Internet access, literacy, or leisure time to browse microblogging web sites. Poor and rural residents are almost entirely excluded from the social media landscape. Pellow (Citation2006, 227) argues that digital technologies “facilitate the development and dissemination of various discourses and cultural imaginings, the most effective of which reinforce capitalist and racist hierarchies within and across societies” (italics added). Moreover, social media are subject to falling under networked authoritarianism. Through direct (action taken directly by state censors) and indirect (action taken by companies under explicit or implied pressure from the state) censorship, the Chinese state has the ability to shape the social media debate over air pollution or any other topic. In addition to repressive censorship, the government and companies can also coopt social media to advance their own agenda, whether that means defending the political bottom line of social stability or the business bottom line of selling products. Our analysis shows that they have done this very successfully. Therefore, it is not surprising that the social media discussion of PM2.5 ultimately has not posed a significant threat to party-state rule or placed greater decision-making power in the hands of ordinary people.

Although Chinese microbloggers clearly helped precipitate a policy response from the government, it is unclear whether Chinese microblogs in their current form—beholden to state censorship and largely unavailable to the very citizens who suffer the worst effects of pollution—are an effective or just medium for public debate. ▪

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Professor Morton O’Kelly and Jens Blegvad of the Ohio State Center for Urban and Regional Analysis for making our data collection possible through their generous logistical support, three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments in helping us prepare the final version of this article, and our friends in the Peking University College of Urban and Environmental Sciences for their logistical support and invaluable insights. The usual disclaimers apply.

Funding

Research for this article is a result of a collaborative research project, “A GIScience Approach for Assessing the Quality, Potential Applications, and Impact of Volunteered Geographic Information,” funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation (Award #104810).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Samuel Kay

SAMUEL KAY carried out this research as a master's student in Geography at Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include urban political ecology, health geography, Chinese urbanization, and environmental justice.

Bo Zhao

BO ZHAO is a PhD student in Geography at the Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include GIScience, social media, crowdsourcing, and volunteered geographic information.

Daniel Sui

DANIEL SUI is a Distinguished Professor of Social & Behavioral Sciences and Chair of the Department of Geography, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include GIScience, crowdsourcing, volunteered geographic information, Chinese cities, and health geography.

Notes

1 Twitter has been banned in China since June 2009.

2 The “grass mud horse,” or cao ni ma, is a homophone of a profane Chinese expression. The phrase became popular in China in 2009 as a symbol of evading censors.

3 Particulate matter 10 micrometers or less in diameter.

4 Due to the nature of Sina Weibo's search API, these posts represent only a portion of all the air-pollution-related posts from this time period. It is not possible to know precisely what percentage of all the air pollution posts were collected by our crawler.

5 Xikeliwu, which can be translated as “fine particulate matter” was adopted in 2013 as the official Chinese name for PM2.5

6 In degree is a measurement of how many users repost or comment on another user's post. Weighted in degree measures the number of reposts or comments a particular user receives. (In degree counts users, whereas weighted in degree counts reposts and comments irrespective of the number of users making the reposts or comments.) Out degree is a measurement of how much a user comments on or reposts other users’ content.

7 Weibo and other microblog services were temporarily disabled in July 2010 to implement “security” measures (Pierson 2010). Comments and other features are also sometimes temporarily disabled (Magistad Citation2012).

Literature Cited

- Bamman, D., B. O’Connor, and N. Smith. 2012. Censorship and deletion practices in Chinese social media. First Monday 17:3–5.

- Biehler, D., and G. Simon. 2011. The great indoors: Research frontiers on indoor environments as active political-ecological spaces. Progress in Human Geography 35 (2): 172–92.

- Buzzelli, M. 2008. A political ecology of scale in urban air pollution monitoring. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 33:502–17.

- Carter, N., and A. Mol. 2006. China and the environment: Domestic and transnational dynamics of a future hegemon. Environmental Politics 15 (2): 330–44.

- Chen, Y., A. Ebenstein, M. Greenstone, and H. Li. 2013. Evidence on the impact of sustained exposure to air pollution on life expectancy from China's Huai River policy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (32): 12936–941.

- Cook, I., and E. Swyngedouw. 2012. Cities, social cohesion and the environment: Towards a future research agenda. Urban Studies 49 (9): 1959–79.

- Cronon, W. 1991. Nature's metropolis. New York: Norton.

- Diamond, L. 2012. Liberation technology. In Liberation technology, ed. L. Diamond and M. Plattner, 3–17. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Eaves, D. 2012. Is Sina Weibo a means of free speech or a means of social control? TechPresident. http://techpresident.com/news/wegov/22736/weibo-centralizing-force (last accessed 22 October 2014).

- Grumbine, R. 2007. China's emergence and the prospects for global sustainability. BioScience 57 (3): 249–55.

- Guo, H., L. Morawska, C. He, Y. L. Zhang, G. Ayoko, and M. Cao. 2010. Characterization of particle number concentrations and PM2.5 in a school: Influence of outdoor air pollution on indoor air. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 17 (6): 1268–78.

- Hao, J., and L. Wang. 2005. Improving urban air quality in China: Beijing case study. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 55 (9): 1298–1305.

- Harper, J. 2004. Breathless in Houston: A political ecology of health approach to understanding environmental health concerns. Medical Anthropology 23 (4): 295–326.

- Heynen, N., M. Kaika, and E. Swyngedouw. 2006. Urban political ecology: Politicizing the production of urban natures. In In the nature of cities: Urban political ecology and the politics of urban metabolism, ed. N. Heynen, M. Kaika, and E. Swyngedouw, 1–19. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hu, Y. 2010. Microblogs are crucial in China. Southern Metropolis Daily. http://cmp.hku.hk/2010/08/06/6439/ ( last accessed 10 May 2013).

- ———. 2011. What government microblogs do (and don’t) mean. The Beijing News. http://cmp.hku.hk/2011/05/23/12633/ ( last accessed 10 May 2013).

- Huang, W., J. Tan, H. Kan, N. Zhao, W. Song, G. Song, and G. Chen. 2009. Visibility, air quality and daily mortality in Shanghai, China. The Science of the Total Environment 407 (10): 3295–300.

- Kappos, A. D. 2011. Urban airborne particulate matter. In Urban airborne particulate matter: Origin, chemistry, fate and health impacts, ed. F. Zereini and C. L. S. Wiseman, 527–51. Berlin: Springer.

- King, G., J. Pan, and M. E. Roberts. 2013. How censorship in China allows government criticism but silences collective expression. American Political Science Review 107 (2): 1–18.

- Lim, L. 2013. To silence discontent, Chinese officials alter workweek. http://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2013/05/04/181154978/to-silence-discontent-chinese-officials-alter-calendar ( last accessed 22 December 2013).

- Lu, H. 2008. The role of China in global dirty industry migration. Oxford, UK: Chandos.

- Ma, J. 2011. A road map to blue skies: China's atmospheric pollution source positioning report. Beijing: IPE.

- MacKinnon, R. 2012. China's “networked authoritarianism.” In Liberation technology, ed. L. Diamond and M. Plattner, 78–94. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Magistad, M. 2012. How Weibo is changing China. Yale Global Online. http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/how-weibo-changing-china ( last accessed 10 November 2012).

- Mehra, M. K., and S. P. Das. 2007. North–south trade and pollution migration: The debate revisited. Environmental and Resource Economics 40 (1): 139–64.

- Myers, I., and R. L. Maynard. 2005. Polluted air—Outdoors and indoors. Occupational Medicine 55:432–38.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2011. Communique of the National Bureau of Statistics of People's Republic of China on major figures of the 2010 population census. http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/NewsEvents/201104/t20110428_26449.html (last accessed 22 October 2014).

- ———. 2012. Income of urban and rural residents in 2011. http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/t20120130_402787464.htm ( last accessed 17 February 2013).

- Pellow, D. 2006. Transnational alliances and global politics: New geographies of urban environmental justice struggles. In In the nature of cities: Urban political ecology and the politics of urban metabolism, ed. N. Heynen, M. Kaika, and E. Swyngedouw, 216–33. London and New York: Routledge.

- People's Daily. 2012. “Beautiful Scenery” at 18th CPC National Congress. http://english.people.com.cn/90785/8011490.html ( last accessed 9 December 2012).

- Phillips, T. 2013. Pollution pushes Shanghai towards semen crisis. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/china/10432226/Pollution-pushes-Shanghai-towards-semen-crisis.html ( last accessed 22 December 2013).

- Pierson, D. Chinese sensors take notice of Twitter-style blogs. Los Angeles Times. http://articles.latimes.com/2010/jul/31/business/la-fi-china-microblog-20100731 (last accessed 22 October 2014).

- Rich, D. Q., H. M. Kipen, W. Huang, G. Wang, Y. Wang, P. Zhu, P. Ohman-Strickland, et al. 2012. Association between changes in air pollution levels during the Beijing Olympics and biomarkers of inflammation and thrombosis in healthy young adults. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 307 (19): 2068–78.

- Schmitz, R. 2013. Pollution boosts clean air industry in China. http://www.marketplace.org/topics/world/pollution-boosts- clean-air-industry-china ( last accessed 30 July 2013).

- Simpson, P. 2013. Chinese smog a “terror risk”: Pollution is now so bad security cameras at sensitive sites can no longer film through the haze. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2488075/Chinese-smog-terror-risk-Pollution-bad-security-cameras-sensitive-sites-longer-film-haze.html#ixzz20De2Q3hr ( last accessed 22 December 2013).

- Sina Weibo. 2013. 2013 development report microblogging users. http://data.weibo.com/ (last accessed 22 October 2014).

- Stout, K. L. 2013. Can social media clear air over China? http://www.cnn.com/2013/04/19/world/asia/lu-stout-china-pollution ( last accessed 10 May 2013)

- Su, F. 2006. Gender inequality in Chinese politics: An empirical analysis of provincial elites. Politics and Gender 2 (2): 143–63.

- Sun, H. 2013. More females on Sina Weibo but less influential than males? http://civic.mit.edu/blog/huan-sun/more-females-on-sina-weibo-but-less-influential-than-males ( last accessed 29 August 2013).

- Sui, D. Z. 2013a. Can red China become green China? Or why do we need to care about China's current environmental crisis? GeoWorld June:21–23.———. 2013b. Citizen science, crowd mapping, and China's environmental problems. GeoWorld September:15–16.

- Tsou, M., and M. Leitner. 2013. Visualization of social media: Seeing a mirage or a message? Cartography and Geographic Information Science 40 (2): 55–60.

- U.S. State Department. 2009. Embassy air quality Tweets said to “confuse” Chinese [Diplomatic cable]. http://wikileaks.org/cable/2009/07/09BEIJING1945.html ( last accessed 15 November 2012).

- Véron, R. 2006. Remaking urban environments: The political ecology of air pollution in Delhi. Environment and Planning A 38 (11): 2093–2109.

- Wang, A. 2013. The search for sustainable legitimacy: Environmental law and bureaucracy in China. Harvard Environmental Law Review 37 (2): 365–440.

- Warf, B. 2010. Geographies of global Internet censorship. GeoJournal 76 (1): 1–23.

- Watts, J. 2012. China's city dwellers to breathe unhealthy air “for another 20–30 years.” The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/jan/03/china-unhealthy-air-pollution ( last accessed 15 November 2012).

- Whitehead, M. 2009. State, science and the skies. New York: Wiley.

- Wong, E. 2013. China lets media report on air pollution crisis. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/15/world/asia/china-allows-media-to-report-alarming-air-pollution-crisis.html?_r=0m ( last accessed 17 February 2013).

- Xiao, Q. 2011. The battle for the Chinese Internet. Journal of Democracy 22 (2): 47–61.

- Xinhua. 2012. PM2.5 in air quality standards, positive response to net campaign. Xinhua News Agency. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2012--03/01/c_122773759.htm ( last accessed 12 January 2013).

- ———. 2013. Chinese cities covered by smog. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013--12/19/c_132981453.htm ( last accessed 12 January 2014).

- Xu, C., D. W. Wong, and C. Yang. 2013. Evaluating the “geographical awareness” of individuals: An exploratory analysis of Twitter data. Cartography and Geographic Information Science 40 (2): 103–15.

- Yeh, E. 2009. Greening western China: A critical view. Geoforum 40:884–94.

- Zhang, H. P., H. K. Yu, D. Y. Xiong, and Q. Liu. 2003. HHMM-based Chinese lexical analyzer ICTCLAS. In Proceedings of the second SIGHAN workshop on Chinese language processing: Vol. 17, ed. Q. Ma and F. Xia, 184–87. Association for Computational Linguistics. http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W/W03/W03-1730.pdf (last accessed 22 October 2014).