Abstract

Despite decades of recognition and worry about diversity, our discipline remains persistently white. That is, it is dominated by white bodies and it continues to conform to norms, practices, and ideologies of whiteness. This is a loss. At best, it limits the possibilities and impact of our work as geographers. At worst, it perpetuates harmful exclusions in our discipline: its working environments, its institutions, and its knowledge production. This remains deeply concerning for many geographers, and there has been important research, commentary, and institutional activity over the years. Yet, research shows us that little meaningful progress has been made. We know that mentoring is one vital part of the journey toward change. As such, we reflect here on our experience developing a research collective built on a transformative mentoring practice. We outline the key challenges, strategies, and tentative successes of the collective in supporting women of color undergraduate, graduate, and faculty geographers, arguing that such feminist formations are a vital part of the path to intellectual racial justice in our field. Key Words: diversity, feminist geography, higher education, mentoring, race.

尽管我们承认并担忧多样性的问题已有数十年, 但我们的学科仍不断维持白人优势, 亦即由白人的身体所支配, 并持续遵循白人的规范、实践与意识型态。这是一个损失。在最好的情况下, 它限制了我们作为地理学者的研究可能性与影响力, 最糟的情况则是导致有害的排外性在我们的学科中永久续存。该问题持续深深地困扰诸多地理学者, 且于过去数年中已有重要的研究、评论和制度活动。但研究却向我们揭露, 有意义的进展相当有限。我们了解, 导师制是迈向改变旅程的重要一环。我们因而于此反思我们建立在转型的导师实践上的研究集体打造的经验。我们摘要出支持有色族裔女性地理学本科生、研究生、以及教职员的集体之关键挑战、策略和暂时性的成功, 主张此般女权主义的形成, 是通往我们领域中的知识种族正义的关键部分。关键词:多样性, 女权主义地理学, 高等教育, 导师制, 种族。

Pese a décadas de reconocimiento y preocupación acerca de la diversidad, nuestra disciplina sigue siendo persistentemente blanca. Es decir, está dominada por cuerpos blancos y sigue ajustada a las normas, prácticas e ideologías de lo blanco. Esto es un desastre. En el mejor de los casos, tal condición limita las posibilidades e impacto de nuestro trabajo como geógrafos. En el peor, perpetúa dañinas exclusiones en nuestra disciplina: sus entornos de trabajo, sus instituciones y su producción de conocimiento. Tal situación sigue siendo preocupación seria para muchos geógrafos y durante años se han realizado importantes investigaciones, comentarios y actividad institucional al respecto. No obstante, la investigación nos muestra que muy poco progreso significativo ha sido logrado. Sabemos que la consejería es una parte vital de las jornadas hacia el cambio. De por sí, aquí reflexionamos sobre nuestra experiencia desarrollando una investigación colectiva edificada sobre una práctica transformadora de la consejería. Bosquejamos los retos y estrategias claves, y los éxitos tentativos del colectivo para apoyar las mujeres de pregrado y las posgraduadas de color y los geógrafos de la facultad, sosteniendo que tales formaciones feministas son una parte vital de la justicia racial intelectual en nuestro campo.

In almost every instance, integration appears to have resulted more in invisibility than in the achievement of equality. Even geography has fallen short in its efforts to be fully integrated in the sense that integration means that minorities are recognized as valuable and integral to the development of the discipline.

—Sanders (Citation1990, 229)

I think the hardest thing for me to grapple with from all my visits was the lack of representation in faculty who look like me, and as much as I did not want that to be the case, geography as a discipline has a long way to go to where we need to be.

—E-mail communication, prospective student (2017, used with permission)

Made nearly thirty years apart, these statements speak to our discipline’s entrenched and ongoing problem with race or, rather, with whiteness (Frankenberg Citation1993; hooks Citation1997; Bonilla-Silva Citation2012) and the challenges this poses for promoting, valuing, and sustaining students and faculty of color. There is much to unpack in these powerful words: the pervasive domination of geography by white bodies and the past-presents of white privilege; the repelling effect on non-white scholars; the reciprocal lifelines of support faculty and students of color afford one another and the crucial mentoring resource that white faculty have been and can become, if this is an ethical and professional priority; the missed opportunities for all when the difficult work of racial intellectual justice is repeatedly, systematically, quietly sidelined or, in exhaustion, given up on.

The first author received the e-mail just cited late in the spring semester of 2017. It came as a deep, but unsurprising, disappointment. This student held one of the strongest academic records she had seen in seven years assessing graduate applications. Just a year out of undergraduate studies, this student already had substantive research experience, publications in print and on the way, and several research awards. Her scholarship was exciting, connecting several disciplines and approaches, and rooted in social justice. Although she was trained outside of the discipline, the first author knew that her project would be richly extended by the field. She felt the same, describing her excitement at the possibilities of a geographic future. We saw great potential in her, worked hard to secure a prestigious pocket of college-level recruitment funding, and made a competitive offer. After much reflection, this student declined.

Of course, this is not the first time, nor the last, that we will lose excellent graduate students in recruitment efforts. Their decisions involve many factors, including those unrelated to a particular program or wider discipline. This student’s words, though, touch on the complex challenges in recruiting students of color into our program and geography more broadly. Paired with Sanders’s (Citation1990) argument, made nearly three decades prior, it seems clear that our discipline has yet to demonstrate that addressing racial injustice, and its intellectual, institutional, and personal losses, is a priority.

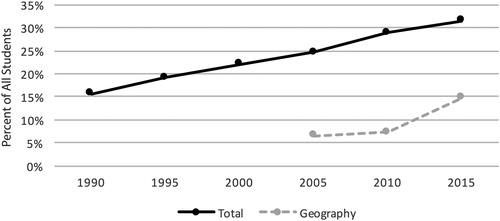

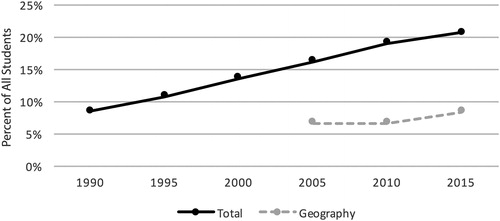

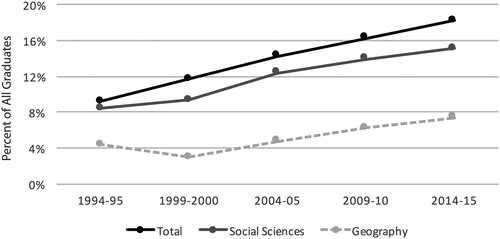

A quantitative analysis highlights the scale of the problem. In 1990, African Americans and Hispanics1 comprised 2 percent of American Association of Geographers (AAG) members. Given increased response rates, comparisons over time are difficult, but nonetheless this figure rose to just 10 percent in 2015 (AAG Citation2016a). Looking deeper, between 1990 and 2015 the proportion of African American and Hispanic students enrolled in undergraduate degree-granting institutions increased from 16 to 31 percent (). Graduate enrollment increased from 8 to 21 percent (). Yet for available geography data (2005–2015), undergraduate and graduate enrollment of African American and Hispanic students hovered around 7 percent. Growing minority membership depends, in part, on developing a larger pool of undergraduate, graduate, and faculty of color in our field. Such growth has occurred in the wider academy but not in our discipline. In fact, many departments reported no undergraduate or graduate students of color in their programs (Solís et al. Citation2014).

Figure 1 Undergraduate enrollment in degree-granting institutions. Sources: National Center for Education Statistics (Citation2016b); Adams, Solís, and McKendry (Citation2014; 2005, n = 48); 2010 Association of American Geographers Survey on Diversity in Geography Departments (Citation2016; 2010, n = 61; 2015, n = 30).

Figure 2 Graduate enrollment in degree-granting institutions (African American and Hispanic students). Sources: National Center for Education Statistics (Citation2016b); Adams, Solís, and McKendry (Citation2014; 2005, n = 40); 2010 Association of American Geographers Survey on Diversity in Geography Departments (Citation2016; 2010, n = 45; 2015, n = 23).

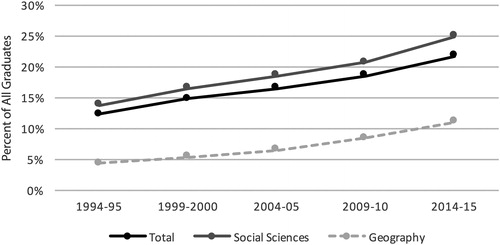

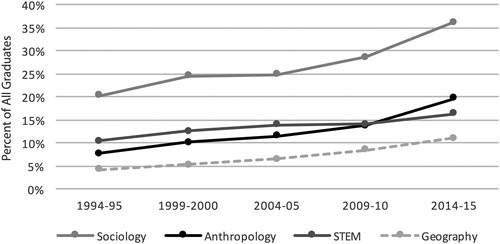

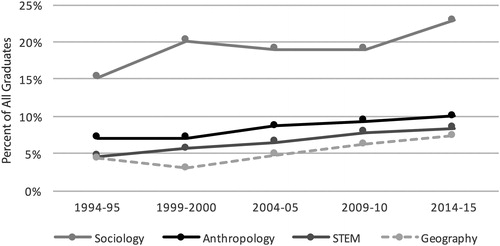

Number of degrees conferred is also important to consider. In geography, undergraduate degrees conferred for African American and Hispanic students rose from 4 percent in 1995 (our earliest available data) to 11 percent in 2015 ( and ). In the same time period, graduate degrees conferred rose from 4 to 7 percent ( and ), lagging significantly behind related disciplines like sociology, anthropology, and wider science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM)2 fields (). Indeed, geography must double its African American and Hispanic graduates to match the social sciences3 and all combined disciplines ( and ).

Figure 3 Graph of bachelor degrees conferred I (African American and Hispanic students). Sources: National Center for Education Statistics (Citation2016), Integrated Postsecondary Education Data.

Figure 4 Graph of bachelor degrees conferred II (African American and Hispanic students). Sources: National Center for Education Statistics (Citation2016a); Classification of Instructional Programs for Geography and Cartography (includes geography, geographic information science and cartography, and geography other).

Figure 5 Graph and table of graduate degrees conferred I (African American and Hispanic students). Graduate degrees include master’s and doctorates. Sources: National Center for Education Statistics (Citation2016a); Integrated Postsecondary Education Data (Citation2016).

Figure 6 Graph and table of graduate degrees conferred II (African American and Hispanic students). Sources: National Center for Education Statistics (Citation2016a), Integrated Postsecondary Education Data (Citation2016).

Another crucial move toward intellectual racial justice is the recruitment and retention of faculty of color. Despite the modest increases in graduate degrees conferred, the proportion of African American and Hispanic geography faculty hovered at 4 to 5 percent between 2005 and 2015 (AAG Citation2016b). To compare, in 2015 the figure was 10 percent across all higher education faculty, twice that of geography (National Center for Education Statistics Citation2016b). Data on tenure-track and tenured faculty also reveal key challenges in recruiting and promoting faculty of color, particularly women of color. In a survey of geography departments, African Americans and Hispanics comprised 3.7 percent of tenured faculty in 2010 and 4.7 percent in 2015 (AAG Citation2016a). Most African American and Hispanic geography faculty are assistant professors, instructors, or adjuncts (59 percent in 2010, 58 percent in 2015), mirroring wider findings on the disproportionately female and minority makeup of contingent faculty (Finkelstein, Conley, and Schuster Citation2016). The reverse is true for white faculty. The majority hold full and associate positions: 57 percent in 2010 and 54 percent in 2015 (AAG Citation2016b). Although our statistical analysis is limited by small numbers and underrepresentation, robust qualitative research underscores the precarity experienced by faculty of color (Mahtani Citation2004, Citation2006; Solís et al. Citation2014; Tolia‐Kelly Citation2017). Together these data signal racial injustice in both the recruitment and promotion of faculty of color. It offers us a stark indication of the whitening of the discipline as we move into its highest, most secure, and powerful ranks.

This overview paints a sobering picture of whiteness across U.S. geography, suggesting sustained challenges for building and sustaining racial diversity in geography. The ALIGNED project (Addressing Locally Tailored Information Infrastructure and Geoscience Needs for Enhancing Diversity) echoes these findings and underscores the geographically specific challenges of building geographic racial justice (Solís et al. Citation2014).

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin), part of the ALIGNED pilot project, offers one geographically particular account of these challenges. Here diversity is also on the agenda. UT Austin has seen a rise in combined rates of Hispanic and African American students from 16 percent in 1990 to 27 percent in 2015. Most growth is among Hispanics,4 with the figures for African Americans remaining static at around 4 to 5 percent for more than twenty-five years (UT Institutional Reporting [UTIR] Citation2017). These diversity measures are mirrored in the College of Liberal Arts. Hispanics are underrepresented here, comprising 22 percent of undergraduates in 2015 (UTIR Citation2017) but 44.6 percent of the eighteen- to twenty-four-year-old Hispanic population in Texas (U.S. Census Bureau Citation2015). The disparity is greater for African Americans, who form only 4.9 percent of undergraduates but 13.3 percent of the state’s eighteen- to twenty-four-year-old African American population. In turn, most of the college’s faculty5 body remains predominantly white, with retention and recruitment of faculty of color a key problem (Heinzelman and Nicholus Citation2017). Over fifteen years (2001–2016) we have seen only modest gains in Hispanic and African American faculty, from 7 to 10 percent and 2 to 6 percent, respectively.

At the department level, we have made gains in undergraduate student diversity, although they are uneven. Hispanic and African American enrollment grew sporadically from 13 to nearly 25 percent between 2000 and 2015 (UTIR Citation2017). In addition to our geography major, we house three others, including urban studies, which was established in 2003 as part of a university-wide diversity initiative (Schlemper and Monk Citation2011). Although no subfield should be seen as beyond the interest of underrepresented students, urban studies is historically far more diverse, with 23 percent Hispanic and African American undergraduates in 2005 compared with 9 percent in geography (UTIR Citation2017). Encouragingly, the gap between the two programs is narrowing, with rates of 28 and 25 percent, respectively, in 2015. Despite these gains, our diversity rates remain below the college and the university levels (which trend near 30 percent). Further, and heeding ALIGNED calls to situate departmental diversity geographically, these rates are far from reflecting the diversity of our state (UTIR Citation2017).

At the graduate level, racial diversity at UT Austin remains well below that of undergrads. The proportion of Hispanic and African American graduate students enrolled university-wide and in our college has grown slowly, from 7 and 8 percent, respectively, in 2000 to 13 and 16 percent fifteen years later. Our department is doing no better than the college or university. For the period for which we have data (2001–2015), there were no geography degrees conferred to African American graduate students, with just a few conferred over the sixty-plus-year history of the department. We are not unique (Solís et al. Citation2014). Interestingly, we are doing well in terms of recruiting and retaining women undergraduates and graduates. In fact, for the period from 2000 to 2012, a recent study places us first in terms of the percentage of graduates who are female (Kaplan and Mapes Citation2016). This is an important achievement given the sustained challenges for women across the discipline (Domosh Citation2000; Luzzadder-Beach and Macfarlane Citation2000; Monk, Fortuijn, and Raleigh Citation2004). This finding also gives us pause, however. It highlights the elided challenges faced by women of color and suggests to us that distinct, if connected, strategies are required to address sexism as it interacts with antiblackness. In turn, it suggests that liberal efforts to increase, for example, numbers of female graduate students often do not fundamentally challenge wider-reaching power structures.

Our review of national, institutional, and departmental-level data, along with established and long-standing research, makes clear that racial injustice in our discipline is a reality. Crucially, our discipline recognizes this as a problem. This is evidenced in part by the many statements, speeches, funds, and pilot programs initiated by the AAG (Lawson Citation2004; Attoh et al. Citation2006; Estaville and Frazier Citation2009; Pandit Citation2009; Kobayashi Citation2011, Citation2012; Schlemper and Monk Citation2011; Sheppard Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Solís et al. Citation2014; Domosh Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2015c; Alderman Citation2017; MacDonald Citation2017). Together, this body of commentary and analysis confirms the reflections of our prospective student that,, indeed, geography has a long way to go.

The Grounds of Whiteness in Geography

Why is this the case? Higher education itself is situated within a wider structural context that limits educational equity (Solís et al. Citation2014).6 Our quantitative analysis, however, is powerful in demonstrating that, although these structural factors affect all STEM and social science fields, geography’s African American and Hispanic rates still lag behind. As such, we ask this question: Why, despite these common challenges, does geography in particular still see lower rates of African American and Hispanic students?

Geographers, along with a wider body of scholars, have carefully researched this issue. We now have a solid understanding of the interwoven elements producing this stasis. Kobayashi (Citation2012, 3) argued that to understand the challenges of building “diversity” in geography, and indeed celebrate it, we must first confront our discipline’s long histories of racism. We first follow her words and those of Kobayashi and Peake (Citation2000), Katz (Citation2001), and McKittrick (Citation2013) in seeking to understand the grounds of this complex issue: its historical production and sedimentation, how it produces and constructs power inequities, and how it forms in particular ways in distinct intellectual and physical places.

Geography has deeply rooted racist grounds, formed via capitalist colonial endeavors that extend to the present day (Kobayashi and Peake Citation2000). The connected and colonially rooted racialization of “wilderness,” “nature,” and “the great outdoors” has alienated, distanced, and dispossessed people of color (Finney Citation2014; Mollett Citation2015). This has powerful legacies for the construction of nature (and formerly colonized spaces and subjects more generally) as appropriate objects of study for white researchers (Kobayashi Citation1994; Abbott Citation2006; Pulido Citation2015). Further layered here is the exclusion, marginalization, and nonrecognition of black and antiracist thought from the discipline’s early formations, the ongoing forgetting of key geographers of color in our intellectual history (Kobayashi Citation2014).

This racialized, colonial history plays an important part in geography’s ongoing injustices. The problem, however, is also entrenched and reproduced by racisms that take more contemporary and varied forms, rooted in and produced through place. Explicit and overt aggressions, what Pulido (2010) called “personal prejudice and racial hostility” (3), are influential, although they are widely (at least publicly) condemned in our geographic community.7 Racial injustice is woven into a more expansive and widely sanctioned quilt of structural racisms, though the policies, ideologies, and cultural practices of our institutions and departments, through their legal frameworks and systems of governance (Kobayashi and Peake Citation1994; Peake and Kobayashi Citation2002; Pulido Citation2002, Citation2014), and via the whitening imperatives of our neoliberalizing public educational system (Abbott Citation2006; Kobayashi Citation2014; Kobayashi, Lawson, and Sanders Citation2014; Pulido Citation2015). These structural racisms are reinforced and enacted in our everyday ways of working and being together: dismissals, closures, silences, denials, and exclusions; the sense of being unseen, unheard, misheard; the expected and considerable labor of “fitting in” and how this goes unrecognized, unvoiced, and unchallenged; the lack of encouragement, recognition, and invitation; the limited engagement with racial power in our curricula, colloquia, and research agendas; and on and on. These factors all work quietly to turn students away from our discipline and to hinder the recruitment, support, retention, and advancement of women, people of color, women of color, and, indeed, all those who are underrepresented in geography.

Research in the United States (Pulido Citation2002, Citation2014; Domosh Citation2015a; Joshi, McCutcheon, and Sweet Citation2015), the United Kingdom, and Canada (Mahtani Citation2004, Citation2006; Ahmed Citation2012; Desai Citation2017; Tolia‐Kelly Citation2017) sheds light on these quotidian violences of intellectual injustice, the adhesive holding together our disciplinary apparatus of structural sexism and racism. One recent and incisive report on faculty diversity at UT Austin argues, “Nothing will change if one expects only those who are here ‘being diversity’ to also undertake the enormous task of ‘doing diversity.’ Diverse faculty long for relief from the emotional, intellectual and physical exhaustion that accompanies their academic and personal lives” (Heinzelman and Nicholus Citation2017, 8). Rather than simply a quality or quantity problem, then, an argument that positions students and faculty of color as lacking, the evidence confirms that the cause of our disciplinary whiteness is rooted in far more complex, historically rooted, and sustained structural racisms. Together these cement the “toxic environments” (Mahtani Citation2014, Citation2017) that stymie a just geography.

Moving Forward: Research Collectives

These reflections prompt a sense of intractability, of paralysis. We sit with and recognize this feeling, and we try to move. Scholars have devoted their careers to understanding what works (Smith et al. Citation2004; Bengochea Citation2010; Turner et al. Citation2017). We now have well-recognized, effective strategies to build racial justice in our academy. Many are not complicated or difficult to implement, if the will is there. In geography we have seen important positive moves.8 Most comprehensively, the ALIGNED project participants developed thirty-two experience-based ideas9 for geography departments to enhance diversity (Solís and Ng Citation2012). Varied and instructive, they speak to the importance of prioritizing diversity (e.g., developing and evaluating plans for recruitment and department well-being), conveying this priority publicly (e.g., through the Web site, job advertisements, and recruitment materials), and using nontraditional networks in faculty and graduate recruitment (e.g., targeting historically black colleges and universities, Hispanic-serving institutions, nontraditional undergraduate majors, and more diverse mailing lists). Although clear and achievable, they are not simply a checklist but an effective tool to prompt meaningful and sustained discussion, action, and structural change.

Mentoring is widely recognized as a vital part of these wider efforts (Reddick Citation2012; Reddick and Young Citation2012). Within our field, feminist geographers have long advocated for the radical potential of mentoring for women (Moss et al. Citation1999; Hardwick Citation2005; Domosh Citation2015b; Datta and Lund Citation2018; see Oberhauser and Caretta [Citation2018], for the most recent AAG panel discussions see Al-Saleh et al. [Citation2018]), although they are not alone in highlighting its wider importance (Cheruvelil et al. Citation2014). Mentoring generates relationships of trust and care that in return transform research itself, decentralizing and challenging hegemonic research practices and advising norms and knowledge production. Mentoring policy and practices alone, without wider institutional and societal shifts, might not foster diversity. Because much of the structure of the academy is centered around research, and instruction and advising tied to research, however, radical mentorship serves as a site for deeply rooted structural change.

Recognizing these transformative possibilities, student and peer–faculty mentoring has become a central part of what makes geography meaningful. Yet, we are academic workers at a flagship university, powerfully driven by neoliberalizing benchmarks (Mountz et al. Citation2015; Caretta et al. Citation2018). We each face the usual professional hurdles of finding a job, keeping it, and getting promoted, while also navigating the gendered and racialized environments we have described. We find ourselves under pressure. We are keenly aware of the many hours we invest in mentoring work that we do not spend “writingpublishingwritingpublishing.” We recognize and value calls for slow, meaningful scholarship while providing emotional, intellectual, and professional support to our peers and students (Mahtani Citation2006; Mountz et al. Citation2015). As feminist geographers we refuse—indeed, we are epistemologically unable—to separate our “work” from these kinds of efforts. For us, a research collective offers one way forward.

The Feminist Geography Collective at UT Austin emerged out of these connected imperatives: to survive, thrive, and resist in a neoliberalizing research institution; to expand our departmental space through networks of feminist intellectual thought and practice; and to support students excited by geographic research but who do not see a place for themselves within the discipline.10 We strive to make our collective that place. Founded on longer established mentoring and research relationships, Caroline Faria, a graduate student (Dominica Whitesell), and an undergraduate student (Annie Elledge) self-organized as a “collective” in fall 2016. Their connected research centered Faria’s National Science Foundation (NSF)–funded project on the geographies of hair and beauty, with a rich, qualitative data set of images, newspaper articles, social media coverage, participatory maps, focus groups, and interview transcripts collected from field sites in Uganda and the United Arab Emirates. We began to meet for two hours each week. In spring 2017 three undergraduates joined the group. Some came regularly, others when they could. Others we described as “friends of the collective,” offering or asking for support as needed. We sought to create a space of support, retreat, and recuperation, of fun and feminist rigor, where enthusiasm for academia, excitement about ideas, and an embrace of challenging and complex problems are cultivated as and through the practice of feminist antiracist research.

The collective is founded on a feminist ethics of knowledge production, research practice, and caring, transformative space making. We view mentoring and research as inseparable. First, a feminist and antiracist epistemology informs our attitude toward knowledge and knowledge production. It shapes the research design, analysis, writing, and sharing of our findings. At each stage we reflect on how power, in varied forms and including our own, shapes the process. Such an approach also demands that we recognize the centrality of our research collaborators in Uganda, who are part of the collective and with whom we maintain regular, often daily contact. This enables a more rigorous and grounded approach to our data, strengthening our findings and fostering more innovative, accessible outputs.

Our feminist epistemology reflects and informs our feminist and antiracist practice, the nuts and bolts of our weekly work. We recognize and try to deconstruct power hierarchies in the academy and in our group, fostering a sense of responsibility to the collective that respects the different pressures we each face. Members practice peer-to-peer, bottom-up, and traditional top-down mentoring, taking turns at more tedious labor, presenting research, facilitating meetings, and writing. Through this model each participant (including the faculty) receives useful mentoring tools and provides valuable research labor to the group. Moreover, by sharing the mentoring responsibility, the weight and repetition of mentoring labor is reduced. This intellectual labor provides analyzed data from Faria’s NSF-funded project and makes possible a set of shared “outputs” (in neoliberal terms), including academic grants and publications (coauthored and lead authored by student members), honors and graduate theses, conference presentations, and posters.

Also central here is a feminist practice of collaboration and sharing or “commoning” (see Henry Citation2019), one that rejects neoliberal drives for competition. This includes creating a database of materials like sample research proposals, human subjects applications, graduate applications, and editorial cover letters. It also means word-of-mouth advice to navigate the frustrations, roadblocks, and opportunities (often obscured to women and minority students) of everyday academic life.

Finally, we work to create a caring, rigorous, and transformative feminist space for our work. We take time to discuss the week’s pressures and longer term challenges, and we build solidarity by sharing and learning from experiences of others. This might mean watching or listening to lectures on the topic (e.g., Mahtani’s [Citation2017] live-streamed presentation at Penn State’s Critical Geography Conference) or sharing our reflections on campus presentations, readings, assignments, or events that prompted frustration, irritation, anxiety, or paralysis. In these moments we also critically reflect on our own words and actions, to acknowledge and learn from our own moments of racism, sexism, and privilege. This critical, caring space extends to UT-based friends of the collective, a wider and growing network of feminist collectives (in the United States, Canada, and Switzerland), and our research collaborators in Kampala, Uganda.

It was in one of these moments of critical reflexivity, at the end of our first year, that the racial makeup of the group came into focus. We had solicited undergraduate members through informal networks and recommendations within geography and a program that the department is closely aligned with, international relations and global studies (housed in government). We had welcomed all those who knew of and expressed interest in the group. This unintentional, and thus uncritical, recruitment method shaped the racial formation of our initial membership. The students were self-motivated and inspiring to work with, and they all identified as white.

Critically reflecting on our recruitment strategy, we recognized that we were reproducing the whiteness of the discipline. Less evident in debates around mentoring is the fact that not all practices of mentoring are effective in supporting gender and racial diversity, and not all feminist practices of mentoring are effective in supporting students of color. They must be attentive to the interconnected work of both racial and gendered power. Despite our thoughtful efforts to build a feminist space, we realized that we were no more transformative in terms of racial justice than the wider field of critical geography (both human and physical). This, as Berg (Citation2012) powerfully noted, remains “an amazingly white field of research and teaching” (509).

In response, we researched strategies to address intersectional exclusion. ALIGNED’s thirty-two tips (Solís and Ng Citation2012) helped, as did our varied experiences. For faculty, this included many hours of work on campus faculty searches in centers and departments, like women’s and gender studies, where diversity was actively valued and deliberately attended to. In turn, the students brought their experiences with, and strategies to mitigate, racism and sexism in their everyday classroom settings. We determined four strategies. First, we crafted an advertisement and accompanying Web site that centered on our commitment to diversity. We then mailed this out to a broader range of undergraduate advisors and listservs. Although this included geography and government and international relations, it also now included much more diverse campus units like Africa and African diaspora studies, women’s and gender studies, Middle Eastern studies, and Latin American studies. In our application request, we now asked candidates to talk explicitly about their interest in a collective like ours, one committed to gender and racial diversity. Finally, we recognized the economic constraints around our collective model. In several ways it mirrored unpaid volunteer internships and uncredited research experiences that can exclude minority and working-class students. In response, we formalized a system of course credit for all participants and clearly stated in our advertisement that research experiences (from lunches to conference and field travel) would be financially covered.

That semester, we received a range of excellent applications. The pool was dramatically diversified. Our collective, and its growing visibility, also played a vital role in the successful and highly competitive recruitment of a graduate student and a new assistant professor that year, both geographers and both women of color. We have also brought scholars of color into the field. One new undergraduate member majoring in history and black studies noted in our end-of-year reflections that she had never considered geography as a field of study. When she read the advertisement, though, and learned more about the collective, she began to see herself as a geographer. This is a sea change from the sentiment expressed in the opening of this article.

A year later, the collective and its members are doing well. Last spring four of our undergraduate members presented posters and papers at the AAG meeting in New Orleans, and the last was in the field conducting fully funded independent research on gender and state violence in Turkey. We have won multiple college, university, and national awards (including our college’s sole social science undergraduate thesis award for a project on the geographies of beauty), many undergraduate research fellowships, a Mellon-Mays undergraduate fellowship, a department-wide undergraduate research paper award, and an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program award. The undergraduate students alone have earned over $40,000 in research funding and awards, presented on campus, nationally, and internationally, and are now submitting articles for consideration in our discipline’s top journals. Research conducted by our two most junior members was among only six projects to reach the final in a university-wide undergraduate research competition. In a competition dominated by the natural sciences and engineering, they were the only finalists selected from our college—two women of color representing undergraduate research for the entire College of Liberal Arts. We recognize that these metrics of success exemplify the kinds of measures that are aggressively reshaping intellectual life and work. Yet through the collective, we have found that we can provide both a supportive environment for navigating academia and a space to produce meaningful, rigorous, intellectual work. In this sense, we used the research collective to operate more healthily within our neoliberalizing academy, one cast in the existing mold of racial and gendered power.

This fall, we have grown to include three new faculty members, a new graduate student, and a host of new undergraduate students, with new strands of research on environmental racism, feminist economic geography, and feminist migration studies. Women of color are now well represented; indeed, they form the majority at each career stage. Building on our efforts to attract and support more students of color, we are more clearly articulating an antiracist feminist practice. Although our focus is intersectional, we see insights for wider diversity work. It does not mean that we will all now sail through all of the challenges of life and work in the academy, but we believe that such a collective is part of the path that makes the journey possible.

We might seem provocative, or naïve, to suggest that it was not that hard to diversify our small corner of geography. Of course, though, in addition to a few hours of reflection and critical redirection, we had already spent years thinking, reading, and listening to understand that racial diversity matters, to know the language to use, and to build recruitment networks. ALIGNED’s resources are an excellent starting point for those without this background. Of course, succeeding requires wide-ranging structural policy and practice shifts, but we can make meaningful changes in how we think, act, and produce knowledge within our field, no matter our chosen epistemologies and methodologies. Given that even critical strands of geography are dominated by white scholars and norms of whiteness, this move alone might not foster, and might even confound, racial justice (Pulido Citation2002; Mahtani Citation2006; Sanders Citation2006; Berg Citation2012; Kobayashi, Lawson, and Sanders Citation2014). As such, we must also support and sustain far more students and faculty of color across all reaches of the field. Antiracist mentoring must be part of a department- and discipline-wide transformation if we are to see meaningful diversity; that is, intellectual racial justice in geography.11

Conclusion

We began this article with the words of scholars at very different ends of the professional spectrum: a preeminent geographer with an expansive body of urban geographic work and an undergraduate student, a geographer in the making. Their words, complemented by wide-ranging qualitative and quantitative data, make clear that in three decades our discipline has failed to make meaningful progress toward racial justice, in our AAG membership, and in the faculty and student makeup of most of our departments. Other fields are making strides. The American Association for the Advancement of Science (Citation2011), American Geophysical Union (Citation2002), and National Academy of Sciences (2011) all have concrete goals for improving diversity as well as dedicated funding and resources. These plans also recognize that their disciplines must assume responsibility for the “limited participation of diverse groups” and correct for how weaknesses in their structure and culture have impinged upon minorities (American Geophysical Union Citation2002, 1). Given our slow disciplinary progress, we must double our efforts to disrupt the social and spatial foundations of racism, inequality, and exclusion. If we do not commit to this we will never meaningfully address the intellectual, institutional, and personal losses inflicted by racial power. We will not answer our most urgent questions; indeed, they might never be asked. More important, perhaps, we cannot claim to be a discipline with justice of any kind at its heart: environmental, human, or other. What, then, does that make us?

We refuse to close here, though. We are filled with excitement and energy for another geographic world. We firmly support sustained structural changes at the national and departmental levels, mirroring and exceeding efforts we see elsewhere in the academy. As part of this work, and following feminist geographic moves elsewhere (Mountz et al. Citation2015; Fem-Mentee Collective Citation2017; and the unpublished but vital work of collectives like those at University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, the University of Kentucky, and Penn State), we recognize the centrality of mentorship to racial intellectual justice. Research collectives, in myriad forms but always with social justice at their heart, are one expression that disciplinary-changing mentoring as research might take. They enrich our work, provide respite, and energize, detoxify, and make us more responsive to the most pressing issues of our time. Although racial injustice has always been a problem, in this moment of explicit white nationalist ascendancy, more geographers are recognizing its centrality in shaping our lives and the importance of responding. Let us use this moment to do so meaningfully and effectively, to build on the sophisticated, layered, and largely unheeded work that has gone before and move toward racial justice in geography. ■

Acknowledgments

We thank Alberto Martinez, Richard Reddick, Patricia Solís, our anonymous reviewers, and our editor Barney Warf for their close reading, detailed engagement, and thoughtful feedback. Their care and rigor with the ideas presented here greatly strengthened the article and represent another form of mentoring, for which we are deeply grateful. We are indebted to our own mentors, including advisors, colleagues, peers, and students in and beyond the discipline, who have and continue to support us as geographers.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Caroline Faria

CAROLINE FARIA is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography and the Environment at The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78701. E-mail: [email protected]. She is a feminist political and cultural geographer and her research examines how gendered and racial power shape nationalism and neoliberal globalization, with a focus on East Africa-Gulf networks and the geographies of hair and beauty.

Bisola Falola

BISOLA FALOLA is a feminist geographer and doctoral graduate from The University of Texas at Austin, and is now a program officer at the Open Society Foundations in New York City, NY 10019. E-mail: [email protected]. She works on youth, urban precarity, and marginalization, and specializing in narrative and cultural change strategies.

Jane Henderson

JANE HENDERSON is a PhD student in the Department of Geography at the University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720-4740. E-mail: [email protected]. She draws on black geographies and feminist political ecology to connect analyses of racial formation, liberal multiculturalism, community organizing and affect economies in the U.S. Midwest. She is a 2017 National Science Graduate Fellowship Program fellow.

Rebecca Maria Torres

REBECCA MARIA TORRES is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography and the Environment at The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78701. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research interests include Mexican and Central American migration to the United States, rural restructuring in Latin America, feminist geography, children's geography, and activist and community-engaged scholarship.

Notes

1 These terms reflect those used in the quantitative data we analyzed. We acknowledge that racial or ethnic identity is more complex than these categories capture and that other minorities experience exclusion. We contend that all minorities are differently and negatively affected by racial intellectual injustice, as is the discipline as a whole. We focus on African American and Hispanic communities here, though, because they see some of the highest rates of exclusion and marginalization in wider academia (Reddick and Young Citation2012), in our discipline (Solís et al. Citation2014), and in our institution (Heinzelman and Nicholus Citation2017). Despite this, as others have argued (Winders and Schein Citation2014, among others), we still have few studies in geography that focus specifically on these groups or the specific forms of racism they experience. In connection, studies of “diversity” that do not carefully disaggregate by racial groups, although valuable, can actually mask the different experiences, forms, and effects of racism. In response, our article highlights a particular feminist antiracist intervention that explicitly addresses the intersections of sexism and antiblackness (Mollett and Faria Citation2018).

2 STEM fields include biological and biomedical sciences, computer and information sciences, engineering and engineering technologies, mathematics and statistics, and physical sciences and science technologies.

3 Social sciences, as defined by the National Center for Education Statistics, includes anthropology, geography, political science and government, urban studies, and sociology, among others. Data for 1990 to 2000 include history; the years thereafter do not.

4 The University of Texas at Austin, unlike a number of its sister institutions in Texas, is not yet an “Emerging Hispanic-Serving Institution” (Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities 2016). Its rates of Hispanic students remain below the threshold required for this status.

5 We refer here to the “teaching faculty” used in the report by Heinzelman and Nicholus (Citation2017), which includes tenured, tenure-track, and nontenured instructional faculty.

6 Neighborhood and school poverty, racially segregated schools, and inadequate funding for a wide range of health care, food, and other safety nets diminish minority and low-income students’ access to educational opportunities and educational outcomes (Katz Citation2004; Ellis et al. Citation2014; Falola Citation2017; Falola and Faria Citation2018). In turn, factors such as exclusionary discipline practices, inadequate or nonexistent materials and labs, and highly uneven access to college preparatory or Advanced Placement courses also create structural barriers. These work together to reinforce the dramatic underrepresentation of minority students, and particularly African American and Hispanic students, in higher education and across the disciplines (Kobayashi, Lawson, and Sanders Citation2014).

7 Consider, most recently, the widely condemned publication of a procolonial argument in Third World Quarterly Gilley (Citation2017, retracted), a piece rejected in the review process but subsequently published. Itself an act of intellectual racism, the important organizing efforts of one female geographer of color were met with an aggressive backlash. Such overt racism inflicts visceral violence on individuals and also sends chilling shock waves throughout our wider community (Sultana Citation2018).

8 For example, the long-standing work of the Race, Ethnicity and Place steering committee; diversity efforts in the Department of Geography at the University of Washington (see https://geography.washington.edu/diversity-and-inclusivity); the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill’s Moore Undergraduate Research Program, with which geographers are actively involved; the University of Tennessee–Knoxville’s faculty development program; a recent Berkeley Black Geographies Symposium (see berkeleyblackgeographies.com); and the work of the Black Geographies specialty group (see https://blackgeographies.org). We welcome further examples ongoing within and beyond the United States.

9 ALIGNED’s thirty-two ideas are available at http://www.aag.org/cs/programs/diversity/aligned/32ideas

10 We are inspired by varied collective models, including within geography departments at Penn State, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, the University of Kentucky, and the University of Bern, and within transdepartmental groups like the Great Lakes Feminist Geography Collective.

11 We recognize here, and value deeply, the vital role of our own mentors. Echoing Kobayashi (2006), given our discipline’s whiteness, most of these have not been faculty of color, nor have they all been feminist geographers. We say this to make clear that all geographers committed to a just discipline have a role to play.

Literature Cited

- Abbott, D. 2006. Disrupting the “whiteness” of fieldwork in geography. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 27 (3):326–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9493.2006.00265.x.

- Adams, J. K., P. Solís, and J. McKendry. 2014. The landscape of diversity in U.S. higher education geography. The Professional Geographer 66 (2):183–94. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2012.735935.

- Ahmed, S. 2012. On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. London: Duke University Press.

- Alderman, D. 2017. Expanding and empowering a culture of mentorship. American Association of Geographers President’s Column. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://news.aag.org/2017/07/expanding-and-empowering-a-culture-of-mentorship/.

- Al-Saleh, D., M. A. Caretta, A. Oberhauser, K. Gillespie, C. Faria, R. Theobald, and E. Noterman. 2018. Difference and mentoring in feminist geography II. Panel session at the annual meeting of the American Association of Geographers, New Orleans, LA, April 13.

- American Association for the Advancement of Science. 2011. Measuring diversity: An evaluation guide for STEM graduate program leaders. Accessed November 8, 2017. http://www.nsfagep.org/files/2011/04/MeasuringDiversity-EvalGuide.pdf.

- American Association of Geographers. 2016a. AAG departments data. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://www.aag.org/cs/disciplinarydata/aagdepartmentsdata.

- ———. 2016b. AAG membership data. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://www.aag.org/cs/disciplinarydata/aagmembershipdata.

- American Geophysical Union. 2002. AGU diversity plan. Accessed November 8, 2017. https://education.agu.org/diversity-programs/agu-diversity-plan/.

- Attoh, S. A., A. Coleman, J. T. Darden, L. Estaville, V. Lawson, J. Marston, I. Miyares, et al. 2006. Final report: An action strategy for geography departments as agents of change. Report for the AAG Diversity Taskforce. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://www.aag.org/galleries/default-file/diversityreport.pdf.

- Bengochea, A. 2010. How we diversified. Inside Higher Ed. Accessed November 1, 2017. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2010/03/10/how-we-diversified.

- Berg, L. D. 2012. Geographies of identity I: Geography—(neo) liberalism—white supremacy. Progress in Human Geography 36 (4):508–17. doi: 10.1177/0309132511428713.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. 2012. ERS annual 2011 lecture. The invisible weight of whiteness: The racial grammar of everyday life in contemporary America. Ethnic and Racial Studies 35 (2):173–94. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2011.613997.

- Caretta, M. A., D. Drozdzewski, J. C. Jokinen, and E. Falconer. 2018. Who can play this game? The lived experiences of doctoral candidates and early career women in the neoliberal university. The Journal of Geography in Higher Education 42 (2):261–75.

- Cheruvelil, K. S., P. A. Soranno, K. C. Weathers, P. C. Hanson, S. J. Goring, C. T. Filstrup, and E. K. Read. 2014. Creating and maintaining high‐performing collaborative research teams: The importance of diversity and interpersonal skills. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 12 (1):31–38. doi: 10.1890/130001.

- Datta, A., and R. Lund. 2018. Mentoring, mothering and journeys towards inspiring spaces. Emotion, Space and Society 26:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2017.08.004.

- Desai, V. 2017. Black and minority ethnic (BME) student and staff in contemporary British geography. Area 49 (3):320–23. doi: 10.1111/area.12372.

- Domosh, M. 2000. Unintentional transgressions and other reflections on the job search process. The Professional Geographer 52 (4):703–8. doi: 10.1111/0033-0124.00259.

- ———. 2015a. How we hurt each other every day, and what we might do about it. American Association of Geographers President’s Column. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://news.aag.org/2015/05/how-we-hurt-each-other-every-day/.

- ———. 2015b. Keeping track of us and keeping us on track. American Association of Geographers President’s Column. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://news.aag.org/2015/02/keeping-track-of-us-and-keeping-us-on-track/.

- ———. 2015c. Why is our geography curriculum so white? American Association of Geographers President’s Column. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://news.aag.org/2015/06/why-is-our-geography-curriculum-so-white/.

- Ellis, M., R. Wright, S. Holloway, and L. Fiorio. 2014. Remaking white residential segregation: Metropolitan diversity and neighborhood change in the United States. The Professional Geographer 66 (2):173–82.

- Estaville, L. E., and J. W. Frazier. 2009. Race, ethnicity, and place. Journal of Geography 107 (6):209–10. doi: 10.1080/00221340802619927.

- Falola, B. 2017. Imagining adulthood from the CC terraces, PhD dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin.

- Falola, B., and C. Faria. 2018. The terrains of trauma: A children’s geography of urban disinvestment. Human Geography: A Journal of Radical Geography 11 (1):73–78.

- Fem-Mentee Collective, A. L. Bain, R. Baker, N. Laliberté, A. Milan, W. J. Payne, L. Ravensbergen, and D. Saad. 2017. Emotional masking and spill-outs in the neoliberalized university: A feminist geographic perspective on mentorship. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 41 (4):590–607. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2017.1331424.

- Finkelstein, M. J., V. M. Conley, and J. Schuster. 2016. Taking the measure of faculty diversity. New York: Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America.

- Finney, C. 2014. Black faces, white spaces: Reimagining the relationship of African Americans to the great outdoors. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press Books.

- Frankenberg, R. 1993. White women, race matters: The social construction of whiteness. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gilley, B. (2017, retracted) The case for colonialism. Third World Quarterly. https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/doi/abs/10.1080/01436597.2017.1369037

- Hardwick, S. 2005. Mentoring early career faculty in geography: Issues and strategies. The Professional Geographer 57:21–27.

- Heinzelman, S., and A. E. Nicholus. 2017. College of liberal arts diversity and inclusion report and recommendations. Austin: University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts.

- Henry, C. 2019. Three reflections on Revolution at point zero for (re)producing an alternative academy. Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography. Advance published online. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1462771.

- Hispanic Association of Colleges and University. 2016. HACU list of emerging Hispanic-serving institutions (HSIs) 2015–16. Accessed December 6, 2017. https://www.hacu.net/hacu/HSIs.asp.

- hooks, b. 1997. Representing whiteness in the black imagination. In Representing whiteness: Essays in cultural criticism, ed. R. Frankenberg, 338–46. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. 2016. Statistical data tables. Accessed November 8, 2017. https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/Home/UseTheData

- Joshi, S., P. McCutcheon, and E. Sweet. 2015. Visceral geographies of whiteness and invisible microaggressions. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 14 (1):298–323.

- Kaplan, D., and J. J. Mapes. 2016. Where are the women? Accounting for discrepancies in female doctorates in U.S. geography. The Professional Geographer 68 (3):427–35. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2015.1102030.

- Katz, C. 2001. On the grounds of globalization: A topography for feminist political engagement. Signs 26 (4):1213–34.

- ———. 2004. Growing up global: Economic restructuring and children’s everyday lives. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Kobayashi, A. 1994. Coloring the field: Gender, “race,” and the politics of fieldwork. The Professional Geographer 46 (1):73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.0033-0124.1994.00073.x.

- ———. 2006. Why women of colour in geography? Gender, Place, and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 13 (1):33–38.

- ———. 2011. Geography and social justice: An invitation. American Association of Geographers President’s Column. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://www.aag.org/galleries/presidents-columns/PresKobayashi20119.pdf.

- ———. 2012. Can geography overcome racism? American Association of Geographers President’s Column. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://www.aag.org/galleries/presidents-columns/PresKobayashi20125.pdf.

- ———. 2014. The dialectic of race and the discipline of geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104 (6):1101–15.

- Kobayashi, A., V. Lawson, and R. Sanders. 2014. A commentary on the whitening of the public university: The context for diversifying geography. The Professional Geographer 66 (2):230–35. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2012.735943.

- Kobayashi, A., and L. Peake. 1994. Unnatural discourse: “Race” and gender in geography. Gender, Place, and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 1 (2):225–43. doi: 10.1080/09663699408721211.

- ———. 2000. Racism out of place: Thoughts on whiteness and an antiracist geography in the new millennium. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90 (2):392–403.

- Lawson, V. 2004. Diversifying geography. American Association of Geographers President’s Column. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://www.aag.org/galleries/presidents-columns/PresLawson200478.pdf.

- Luzzadder-Beach, S., and A. Macfarlane. 2000. The environment of gender and science: Status and perspectives of women and men in physical geography. The Professional Geographer 52 (3):407–24. doi: 10.1111/0033-0124.00235.

- MacDonald, G. 2017. Strengths and challenges of diversity. American Association of Geographers President’s Column. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://news.aag.org/2017/01/strengths-and-challenges-of-diversity/.

- Mahtani, M. 2004. Mapping race and gender in the academy: The experiences of women of colour faculty and graduate students in Britain, the U.S. and Canada. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 28 (1):91–99. doi: 10.1080/0309826042000198666.

- ———. 2006. Challenging the ivory tower: Proposing anti-racist geographies within the academy. Gender, Place, and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 13 (1):21–25.

- ———. 2014. Toxic geographies: Absences in critical race thought and practice in social and cultural geography. Social & Cultural Geography 15 (4):359–67.

- ———. 2017. Toxic geographies: Absences in critical race thought and practice in social and cultural geography. Keynote lecture at Penn State Critical Geographies Conference. Accessed October 27, 2017. http://www.geog.psu.edu/news/events/critical-geography-keynote-minelle-mahtani-toxic-geographies-absences-critical-race.

- McKittrick, K. 2013. Plantation futures. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 17 (3):1–42.

- Mollett, S. 2015. Displaced futures: Indigeneity, land struggle, and mothering in Honduras. Politics, Groups, and Identities 3 (4):678–83. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2015.1080620.

- Mollett, S., and C. Faria. 2018. The spatialities of intersectional thinking: Fashioning feminist geographic futures. Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 25 (4):565–77. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2018.1454404.

- Monk, J., J. D. Fortuijn, and C. Raleigh. 2004. The representation of women in academic geography: Contexts, climate and curricula. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 28 (1):83–90. doi: 10.1080/0309826042000198657.

- Moss, P., K. J. DeBres, A. Cravey, J. Hyndman, K. Hirschboeck, and M. Masucci. 1999. Toward mentoring as feminist praxis: Strategies for ourselves and others. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 23 (3):413–27. doi: 10.1080/03098269985371.

- Mountz, A., A. Bonds, B. Mansfield, J. Loyd, J. Hyndman, M. Walton-Roberts, R. Basu, et al. 2015. For slow scholarship: A feminist politics of resistance through collective action in the neoliberal university. ACME: An International e-Journal for Critical Geographies 14 (4):1235–59.

- National Academy of Sciences. 2011. Expanding underrepresented minority participation: America's science and technology talent at the crossroads. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). 2016a. Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) for Geography and Cartography 1995-2015. Accessed February 11, 2019. https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/cipcode/Default.aspx?y=55

- ———. 2016b. Digest of education statistics: PostSecondary education 1990–2015. Accessed November 8, 2017. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/current_tables.asp.

- Oberhauser, A. M., and M. A. Caretta. 2018. Mentoring for early career women geographers in the neoliberal academy: Dialogue, reflexivity, and ethics of care. Geografiska Annaler, Series B. Advance onlne publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2018.1556566

- Pandit, K. 2009. Leading internationalization. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 99 (4):645–56. doi: 10.1080/00045600903120552.

- Peake, L., and A. Kobayashi. 2002. Policies and practices for an antiracist geography at the millennium. The Professional Geographer 54 (1):50–61. doi: 10.1111/0033-0124.00314.

- Pulido, L. 2002. Reflections on a white discipline. The Professional Geographer 54 (1):42–49. doi: 10.1111/0033-0124.00313.

- ———. 2014. Faculty governance at the University of Southern California. In The imperial university: Race, war, and the nation-state, ed. M. Sunaina and P. Chatterjee, 145–68. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- ———. 2015. Geographies of race and ethnicity 1: White supremacy vs white privilege in environmental racism research. Progress in Human Geography 39 (6):809–17.

- Reddick, R. J. 2012. Male faculty mentors in black and white. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education 1 (1):1–33.

- Reddick, R. J., and M. Young. 2012. Mentoring graduate students of color. In Sage handbook of mentoring and coaching in education, ed. S. Fletcher and C. A. Mullen, 412–29. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Sanders, R. 1990. Integrating race and ethnicity into geographic gender studies. The Professional Geographer 42 (2):228–31. doi: 10.1111/j.0033-0124.1990.00228.x.

- ———. 2006. Social justice and women of color in geography: Philosophical musings, trying again. Gender, Place and Culture 13 (1):49–55.

- Schlemper, B., and J. J. Monk. 2011. Discourses on “diversity”: Perspectives from graduate programs in geography in the United States. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 35 (1):23–46. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2010.499564.

- Sheppard, E. 2012a. Diversifying geography. American Association of Geographers President’s Column. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://news.aag.org/2012/12/diversifying-geography/.

- ———. 2012b. Geography outside. American Association of Geographers President’s Column. Accessed November 1, 2017. http://www.aag.org/galleries/newsletter-files/JUAG_NL_2012_FINAL.pdf.

- Smith, D. G., C. S. Turner, N. Osei-Kofi, and S. Richards. 2004. Interrupting the usual: Successful strategies for hiring diverse faculty. The Journal of Higher Education 75 (2):133–60. doi: 10.1353/jhe.2004.0006.

- Solís, P., J. K. Adams, L. A. Duram, S. Hume, A. Kuslikis, V. Lawson, I. M. Miyares, D. A. Padgett, and A. Ramírez. 2014. Diverse experiences in diversity at the geography department scale. The Professional Geographer 66 (2):205–20. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2012.735940.

- Solís, P., and A. Ng. 2012. 32 strategies to enhance diversity in your geography department or program. Washington, DC: Association of American Geographers.

- Sultana, F. 2018. The false equivalence of academic freedom and free speech: Defending academic integrity in the age of white supremacy, colonial nostalgia, and anti-intellectualism. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geography 17 (2):228–57.

- Tolia‐Kelly. D. P. 2017. A day in the life of a geographer: “Lone,” black, female. Area 49 (3):324–28.

- Turner, C. S. V., P. X. Cosmé, L. Dinehart, R. Martí, D. McDonald, M. Ramirez, L. Sandres Rápalo, and J. Zamora. 2017. Hispanic-serving institution scholars and administrators on improving Latina/Latino/Latinx/Hispanic teacher pipelines: Critical junctures along career pathways. Association of Mexican American Educators Journal 11 (3):251–75. doi: 10.24974/amae.11.3.369.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2015. 2011–2015 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. Accessed November 8, 2017. http://factfinder2.census.gov.

- University of Texas at Austin Institutional Reporting. 2017. Public database. Austin: University of Texas at Austin.

- Winders, J., and R. Schein. 2014. Race and diversity: What have we learned? The Professional Geographer 66 (2):221–29. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2012.735941.