Abstract

The online pivot has opened many people’s eyes to new possibilities and challenges in the postpandemic world. This article describes what five geographers in three different countries learned from the experiment and assesses how the lessons can be carried forward. One of the big surprises for some of us was the extent to which students were open to different ways of learning during the 2020–2021 academic year. It is clear that some students wish to continue their programs either partially or completely online, although it is also clear that students continue to enjoy field work. The online pivot also showed us that assessment needs to be reexamined, student stress levels need to be lowered, and inequities among students need to be addressed. There are challenges associated with online education across international borders. From a faculty perspective, we have found that nobody needs to be isolated from research opportunities and collaboration, but there are also limits on what we can do. There are growing threats to academic freedom, and we need to move faculty away from precarious employment. Finally, some of us learned the importance of work–life balance.

網路轉型讓我們看到後疫情時代的新機遇與新挑戰。本文闡述了來自三個國家的五位地理學者從此轉型中所汲取的經驗, 並思考如何應用於日後的教與學。學生在2020-21學年對於不同的教學方法的開放態度令部分人感到驚訝。儘管學生繼續對田野實察感興趣, 一些學生希望通過網路完成部分或全部課程。另一方面, 網路轉型揭示了不少改善的需要, 包括重新檢視評核機制、減輕學生壓力, 以及消弭學生間的社經差異, 同時突出了跨國網路教學的挑戰。就教師而言, 參與各種線上活動雖然有助維持疫情下的科研合作, 但應量力而爲。我們需要關注學術自由面臨日益增加的威脅, 也要致力減少以不安定模式僱用教師。最後, 部分人認識到平衡工作與生活的重要性。

El pivote en línea ha abierto los ojos a mucha gente sobre las nuevas posibilidades y retos del mundo pospandémico. Este artículo describe lo que cinco geógrafos de tres países diferentes aprendieron del experimento, y evalúa cómo se pueden llevar a cabo las lecciones. Una de las grandes sorpresas para algunos de nosotros fue el grado de apertura de los estudiantes a diversas forma de aprendizaje durante el año académico 2020-2021. Claramente se nota que algunos estudiantes desean continuar sus programas en línea de manera parcial o total, aunque también queda claro que los estudiantes siguen disfrutando del trabajo de campo. El pivote en línea también nos mostró que la evaluación requiere ser reexaminada, los niveles de estrés de los estudiantes deben ser reducidos y las desigualdades entre los estudiantes demandan atención. Existen retos relacionados con la educación en línea a través de las fronteras internacionales. Desde la perspectiva de los docentes, hemos hallado que nadie quiere ser marginado de las oportunidades de investigación y colaboración, aunque hay también límites sobre lo que podemos hacer. La libertad académica está cada día más amenazada y necesitamos blindar al profesorado contra la precariedad laboral. Finalmente, algunos hemos aprendido la importancia de conciliar la vida laboral y familiar.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused the rapid move of campus-based classroom learning to an online environment, a shift widely known as the online pivot (e.g., Donovan Citation2020; Gardner Citation2020). The largest, most extensive, and most sudden change in postsecondary education ever undertaken, this change affected many millions of postsecondary students studying a broad range of subjects in universities and colleges around the globe in early 2020. The impacts of the online pivot were uneven, and some students and faculty were severely disadvantaged (Day et al. Citation2021).

Pandemics have a life span. The virus is unlikely to disappear but will become more manageable as an endemic disease (Torjesen Citation2021). Many people are already anticipating a return to “normal,” but normal is an ever-shifting paradigm. Major changes in the teaching of geography (and other subjects) were already underway prior to the pandemic. Accompanied by government funding reductions, neoliberalism was encouraging massification, consumerism, vocationalism, and precarity in postsecondary education before the online pivot (Hill, Walkington, and Dyer Citation2019). More technology was used in teaching and learning in different environments (e.g., Welsh et al. Citation2018; Godlewska et al. Citation2019; Wood Citation2020), curriculum renewal was under discussion (e.g., Boehm, Solem, and Zadrozny Citation2018; Walkington et al. Citation2018; Lewin and Gregory Citation2019), and field work was being invigorated by new technologies and pedagogies (e.g., Raath and Golightly Citation2017; Wang, Van Elzakker, and Kraak Citation2017; France and Haigh Citation2018). Internationalization was also of growing importance (e.g., C. Clark and Wilson Citation2017; Simm and Marvell Citation2017), as was indigenization, especially in Canada and Australia (e.g., Gaudry and Lorenz Citation2018; Nursey-Bray Citation2019; Moorman, Evanovitch, and Muliaina Citation2021). Learning management systems (LMSs) were already widely used before the pandemic in different ways by faculty in campus-based teaching and learning. At the same time, there was also prepandemic growth in the availability of online courses in geography (Schultz and DeMers Citation2020).

Spaces of learning were also changing prior to the pandemic (R. Brooks, Fuller, and Waters Citation2012), and the pandemic has accelerated change. The online pivot highlighted the role of place in postsecondary education (Thomas et al. Citation2021), but it also questioned it. Arguably, the geography of postsecondary education has changed at multiple scales. Some students are taking online courses from campus, and others are attending face-to-face courses online from off-campus locations. Students no longer need to be at a place, but many want to be anyway. Binary choices about whether to attend a lecture or not have now been replaced by more options. The implications are profound for pedagogy, student recruitment, and funding.

Prepandemic trends in geography education might continue but will inevitably be informed and disrupted by our individual and collective pandemic experience. COVID-19 is a cultural inflection point within the academy (Bryson et al. Citation2021). We postulate that every faculty member, department, and institution has learned something from the online pivot, and that those lessons can be carried forward in a way that does not evoke nostalgia for prepandemic times. Although institutions commonly believe they pay sufficient attention to the design of learning experiences, educational inclusion, and student and faculty workloads, faculty and students’ experience might suggest otherwise.

In this study, we both acknowledge the achievements of the online pivot and also are reflective and self-critical with a view to moving forward. Our approach is based on diverse personal experiences at different types of institutions in different countries (), together with extended discussions among ourselves, and with students and colleagues since early 2020. All five authors have experienced the responsibility and stress of caring for loved ones and borne the grief of illness, death or both of family and friends during the pandemic. Students and colleagues have turned to us for hope, and in turn we have listened and learned from those who sought help from us. Two of us, as department chairs, have been privy to many heart-wrenching situations as faculty and students sought relief from impossible situations.

Table 1 A brief guide to the researchers and their institutions

We do not argue that our learning is applicable everywhere. Systems of postsecondary education differ from place to place and between institutions. The lessons learned in one institution through the experience of the online pivot might already have been previously learned and implemented in other universities and colleges prior to the pandemic. Rather, we hope the diversity of experiences from our five institutions in three different countries can complement the many single-institution or single-jurisdiction research studies that have been or will soon be published. For clarity, we have provided descriptions of key terms used in the article ().

Table 2 Terminology used in this article

Lessons from the Pandemic

Course Modalities: Students Are Open to Different Ways of Learning

Many students spent the online pivot looking forward to a return to campus (Day et al. Citation2021), but many others discovered they enjoyed online classes, or at least aspects of them. This is an acceleration of a preexisting trend of student interest in online learning. A 2019 survey of more than 40,000 undergraduates studying a range of different subjects in postsecondary institutions across the United States showed that approximately 30 percent of students had a preference for all or most of their learning being online, and 56 percent preferred some form of blended learning (Gierdowski Citation2019).

Since the start of the pandemic, some students’ only option has been to explore online learning. The result has been startling. According to a survey in December 2020 by U.S. nonprofit organizations New America and Third Way, 76 percent of more than 1,000 U.S. students wanted classes to continue in a mixed or online format (Burke Citation2021). Unanticipated high levels of demand were also found in an unpublished December 2020 survey at Okanagan College (OC), with 42 percent of students wanting online lectures to continue, even though the college previously had few online courses. Student comments in teaching evaluations show that students at the University of Texas, Austin (UT) appreciated faculty who became engaged in the online teaching and learning process and were less enthusiastic about those who did not. Personality traits of students might also affect individual student responses (Dikaya et al. Citation2021).

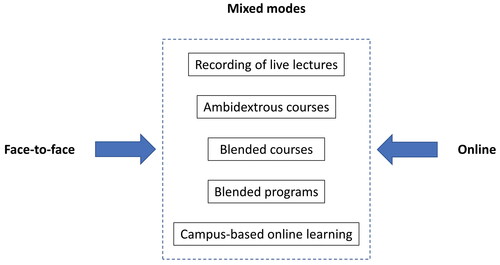

Things might change in the future, but for the present online teaching is not for everyone, and neither is online learning. It is possible that enrollment and preference for online courses will increase as a result of experience during the online pivot (O’Neill et al. Citation2021). Those students look forward to being able to complete their education while taking up paid employment, taking care of family, or fulfilling other responsibilities. Student and faculty choices on course modality are no longer binary, however. There are a range of other options, including watching and listening to lectures recorded live, ambidextrous courses, blended courses, blended programs, and the option for students to take their online course while on campus working together with their friends ().

Some faculty developed ambidextrous courses during the pandemic (Thomas and Bryson Citation2021). These “room and Zoom” approaches gave students the choice of being online or in a face-to-face environment. They were popular among students, but at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) and Sinclair Community College (SCC) they were found to be demanding on faculty, if done well. It was found to be difficult to ensure that equal attention is given to students in the classroom and online; for example, it is easier to spot the reactions of those in the classroom. Occasional technical glitches also made the approach challenging. It appears the experiment has been successful, though, as these courses continue to be offered in some institutions.

Recording of synchronous lectures has blurred the difference between synchronous and asynchronous approaches to online education. This practice has been popular with students, especially for those with home or employment responsibilities for whom attendance at a lecture was difficult or impossible. At UT, lecture capture was popular before the online pivot but involved information technology specialists recording face-to-face lectures. At Kennesaw State University (KSU), where geography courses were already offered in a variety of face-to-face, online, and mixed formats, some faculty already had lecture recordings available for their online courses. At OC this was not the case, although some students requested permission to record lectures, which was usually agreed to by faculty.

The online pivot also meant that student researchers who lacked the resources to attend in-person conferences have also been able to participate and present at no-cost or low-cost virtual conferences. This “internationalization at home” (Rauer et al. Citation2021) reduced costs, time, and carbon emissions. Carbon emissions for conferences and field work are emerging as a difficult and important constraint on departmental activities (Anderson, Martin, and Nevins Citation2022; MacDonald Citation2022; Williams and Love Citation2022).

At the same time, live, in-person lectures can be theatrical and entertaining. Students continue to enjoy well-organized lectures with active student participation taught by passionate, enthusiastic lecturers (Revell and Wainwright Citation2009). Lecturers can see and respond to “enlightened, confused, bewildered, or even bored looks” from students (Bain Citation2004, 118). Video might have killed the radio star, but lectures survived the online pivot.

The availability of a range of both online and live face-to-face modes, along with various mixed modes, reflects the range of student aspirations and needs. For some students, postsecondary education is a service that provides knowledge, skills, and a credential. For other students, though, a college or university education provides an experience with, in addition to those elements we just listed, late nights talking and listening, sports, dances, victories and failures, dead ends, and friendships lost and gained. This distinction between a service and an experience is well recognized within the business community (Pine and Gilmore Citation2011), and perhaps needs to be better understood and accommodated in universities and colleges.

The enhanced range of different teaching and learning opportunities and choices is a win for students, and to some extent a win for faculty, too, with more flexibility on where and how to work.

Social Constructivism: Online and Campus-Based Pedagogies Learn from Each Other

Constructivism has long been the dominant paradigm in teaching and learning research (Day Citation2012). The construction of knowledge is increasingly seen as a shared activity among students, however. Social constructivism connects learning to what students already know, based on shared goals and dialogue among students, as well as dialogue between the class and faculty (Hill, Walkington, and Dyer Citation2019). Students in courses with collaborative activities during the online pivot typically did better than students in similar courses without collaborative activities (Motz et al. Citation2022).

Although physical connections in a place facilitate study groups and group work, social constructivism has risen to the fore in recognition of learning communities as a critical aspect of online course design. Wikis, blogs, and chat on social networks are all common components of online courses (e.g., Barak Citation2017) that recognize the fact that students do not learn in isolation; they learn as part of a class. These online learning communities are now becoming an online component in face-to-face teaching, however.

During the pandemic, we have observed more comprehensive use and broader acceptance of LMSs in our institutions. Although this aligns with experience elsewhere (Raza et al. Citation2021), the implementation of LMSs during COVID was uneven across the world (see Cavus, Mohammed, and Yakubu Citation2021; Mohammadi, Mohibbi, and Hedayati Citation2021).

We were surprised that online student consultations with screen sharing capabilities (e.g., through Zoom) worked so well. Traditional office hours are inconvenient to faculty and part-time students, and e-mail is ineffective when students struggle to describe what they do not understand. Online asynchronous discussion through an LMS discussion board also worked well for graduate courses at CUHK and undergraduate courses at KSU. Faculty in traditional content-intensive courses taught on campus have discovered the learning community aspects of their LMS through the forced experiment of the online pivot. Students have also become more familiar with the technologies, and that has generated higher levels of engagement in online learning since the online pivot (OC, KSU, SCC).

Faculty requests for students to turn on their video were reported to work well at UT, with increased engagement and better approximation with face-to-face conditions. Social constructivism is promoted as faculty were better able to “read” the mood of a class, and students get to see their peers. There is also a case for training students to become comfortable with cameras as they are a common aspect of contemporary professional life. There are also cases, however, in which students turned up for lectures with their video turned off, and did not answer when called on (OC, UT).

Reasons for such acts might vary from case to case. Some students might be deceiving their parents or partners into believing that they were listening to a lecture when they were not, or funders who require evidence of attendance as a condition for funding. Nonetheless, there could also be students who are concerned about personal privacy or attempt to screen their home environment and social background from others’ gaze. Virtual or blurred backgrounds are available in some online conferencing systems, but not all. Without ascertaining students’ motivation for keeping their video off, a mandatory video-on class policy risks doing more harm than good to the bonding between faculty and students.

Traditional online learning might also have something to learn from the online pivot. During the early days of the online pivot, specialists in online education distanced themselves from “emergency remote” teaching (Hodges et al. Citation2020; Schultz and DeMers Citation2020). The difference has become increasingly blurred, though, as some students prefer the spontaneity and relatable presence of their professor on the screen to the “talking head” of traditional asynchronous online courses. Synchronous (but recorded) online courses lack the high production values of asynchronous courses, but our experience is that their spontaneity and human connection are engaging to students. We suggest that traditional online courses would benefit from more active “live” participation of faculty. Other suggestions include a broadening of learning objectives to social rather than just individual goals, and the availability of faculty during virtual “office hours” (O’Neill et al. Citation2021). There is also a need to update the teaching of study skills to reflect new teaching and learning realities (Boström et al. Citation2021).

International Education: The Challenge of Teaching and Learning Across Borders

With many classes shifted online, however, there are reasons for all faculties and students not to take their usual teaching and learning context for granted. Especially for institutions with international students stranded in or returned to their home countries, spaces of education have been stretched across borders digitally to parts of the world with political and legal circumstances that faculties and students might be scarcely familiar with. Given the prevalence of online surveillance of scholarly activities (Tanczer et al. Citation2020), students attending online classes might worry about exposing themselves to unwanted attention for discussing issues that are considered controversial or even censored in places where they or their peers are located. As faculty endeavor to promote critical debates in teaching, they should also recognize the varying sociopolitical contexts within which their students find themselves and be conscious of the potential implications of their pedagogies to students.

Jurisdictional boundaries and different regulations can also cause other forms of unequal access to learning resources. Faculty at OC noted that textbooks are sometimes not available for purchase in some countries. The reasons for this are sometimes unclear but might include copyright issues or government approval of textbooks. International online retailers with national sites sometimes make a textbook available in one country but not in another, or do not accept commonly accepted credit cards issued in some countries. This situation also must be accommodated.

Assessment: A Rethink is Required

One of the disappointments of the online pivot was the demonstrable cheating that took place in many courses. There are threats to academic integrity with the rise of homework help sites such as Chegg, CourseHero, and Brainly. In British Columbia, answers to a set of new physical geography labs were posted on Chegg shortly after publication. This is not just a local problem. There has been a documented rise in student subscriptions to homework help sites during the pandemic (Lancaster and Cotarlan Citation2021), and increased student use is also reflected in a 2.8-times jump in the price of publicly listed Chegg stock between March 2020 and June 2021.

Contract cheating is the practice of paying someone to complete an assignment for a student. Essay writing services, including the cynically named unemployedprofessors.com, cannot usually be identified by plagiarism detection software. Contract cheating by “ghost students” who complete an entire course for a student can also be purchased (Hollis Citation2018). Contract cheating is difficult to detect, underreported, and growing (Newton Citation2018). The causes apparently relate to dissatisfaction with the teaching and learning environment, and the opportunity to cheat (Bretag et al. Citation2019). Students who do not cheat express frustration about other students cheating.

There are no simple solutions to the problem, although the UK government intends to make it a criminal offense to provide, arrange, or advertise cheating services for financial gain in all postsixteen education institutions in England (Department for Education and Burghart 2021). In other jurisdictions, concerns have largely been addressed by making it harder for students to cheat.

Even honest students dislike proctoring software, such as Respondus and HonorLock. They accentuate test anxiety and invade a student’s privacy. There have also been suggestions by some students that there is a racial bias in some of the software (see University of Wisconsin [Citation2021]). The use of surveillance systems is explicitly rejected by some universities, such as the University of Victoria (Citationn.d.) in Canada.

Cheating has also been addressed by the creation of test banks where each student has a random collection of questions (OC, UT, SCC), and by using quizzes as low-stakes reviews of reading materials with students given the option to complete a quiz twice (SCC). Because faculty quickly created them, some test bank questions have not been properly tested and might be unclear. Another approach is to create more open-ended questions (CUHK) and to make them open book (CUHK, KSU, OC), with the reduced use of “model answers” promoting critical thinking about issues. Oral examinations have also been used in undergraduate courses (OC).

A better solution might be to create graded assignments that are meaningful to the students, where fewer students would want to cheat. Although authentic assessment does not stop contract cheating (Ellis et al. Citation2020), the opportunity for students to resubmit assignments turns assignments away from being an assessment toward being a learning activity (Moll Citation2020). Assignments that involve developing a new applied skills set and learning the basics of a new technology, such as free open source online mapping and geovisualization tools, to create a deliverable product to address an applied issue of concern were interesting to students (KSU). Personalization of teaching and assessment is another possibility (Whalley et al. Citation2021). Likely, some combination of different types of assessment might be best because some students perform better on certain types of assignments.

There is no panacea to this problem. Despite evidence of widespread cheating, many faculty prefer to believe it does not happen in their classes. We think the first step is to move away from denial of the problem, and for departments to engage in meaningful discussions about how to address the issue. Security of the assessment system should be one aspect of the discussion, but there are also broader issues relating to the nature and purpose of assessment. Articulation or transfer of courses between institutions could be an issue, however, if the assessment is changed. For example, The University of British Columbia, to which many OC students transfer, requires that all transferred courses have a final examination. Discussions could benefit from the incorporation of student perspectives.

Field Work: It Remains an Essential Component of Geography Education

Field work is widely regarded as an essential part of student training and has been characterized as a “signature pedagogy” in geography (Kim Citation2022).

At UT, a field techniques course was taught in person during the fall 2020 semester despite the pandemic. The justification made to the university administration was based on the small class size (fourteen students), outdoor environment, and use of small groups within the class. As the only face-to-face class that semester, held outdoors, and with perfect weather, this was the best experience possible for both faculty and students.

In general, though, the pandemic required reimagination of class field work (Gibbes and Skop Citation2022). As a substitute, at CUHK, OC, SCC, and UT, field exercises were developed that students completed independently, in their local environment, with recording devices or borrowed or homemade equipment. For example, SCC collaborated with the City of Dayton to conduct a tree equity project in which students related socioeconomic vulnerability indexes to the neighborhood’s tree canopy. At CUHK, one faculty member asked students to visit sites in small groups at designated times, where he would be present to answer their questions. During the fall 2021 semester, a UT geographer received permission to teach a synchronous environmental management field course from Botswana, with students in Austin in real time participating in activities such as controlled burns and interviews with government officials. Each approach stimulated engagement with the subject and their environment and, based on the nature and quality of student reports, was enjoyed by students. The approach also encourages student independence and accountability with the need for students to document their experience. Safety briefings need to be carefully considered in a local context.

At CUHK and KSU, faculty prepared Google Earth “visits” and “tours” to various places and subregions. For KSU, a scheduled field trip to the nearby Centers for Disease Control Museum in Atlanta used the virtual exhibition instead (see http://www.cdcmuseum.org/). There is recognition, however, of the need to expand the role of virtual field work to include data collection, day-to-day logistical issues (de Paz-Álvarez et al. Citation2022), and the social attributes of real-world field work, such as teamwork and communication (Li et al. Citation2022; Wright et al. Citation2022).

Although virtual field trips are not a valid substitute for the multisensory experience of “real field work,” they provide, as with social work placements (Tortorelli et al. Citation2021), the opportunity to participate in “visits” to areas that would otherwise be too hazardous for students. It is likely that virtual field work will continue to function as an important preparation for field visits, as an adjunct to lectures, and as a component of course assignments to engage students in different mapping technologies.

Based on evidence from course evaluations and informal surveys, we suspect that these types of activities will continue in the future, although there is some uncertainty as to whether online field classes will meet the professional registration requirements of geoscience licensing bodies.

Mental Health: Student Stress Levels Need to Be Lowered

Students told us how stressed they were during the pandemic, and this is one of the best documented aspects of the online pivot (e.g., Mheidly, Fares, and Fares Citation2020; Browning et al. Citation2021; Copeland et al. Citation2021; Fruehwirth, Biswas, and Perreira Citation2021; Villani et al. Citation2021). For our part, we observe more disengagement in some students but also experience obsessive engagement in other students with microaggressions during class discussions and in e-mails to faculty. In general, students have been and are stressed. We see more withdrawals from courses and programs, and greater demand for tutoring and counseling. We have responded with in-class discussions of mental health challenges and promotion of counseling services within our institutions. In addition, OC, SCC, KSU, and CUHK have provided extensions for students, often without demanding documentation.

Mental health issues had been increasing prior to the pandemic (Linden, Boyes, and Stuart Citation2021). The period immediately after the online pivot shed light on nonacademic issues that affect student stress and success and highlighted inequalities in already underserved student populations (Duran and Núñez Citation2021; Lederer et al. Citation2021). The pandemic exacerbated many of these issues with changes in living conditions, housing and food insecurities, uncertain employment, health issues, and social isolation (Lederer et al. Citation2021). These stressors manifested themselves in different ways for different students. The situation in Hong Kong was exacerbated by stress associated with earlier social unrest (CUHK), whereas at SCC heightened awareness of mental health issues must be placed in the context of a challenging year (2019) in the community that included a White supremacist rally, a devastating tornado, and a mass shooting. Everywhere, environmental issues are depressing, with a recognized need to provide hope and agency to students (Petersen and Barnes Citation2020; Marazziti et al. Citation2021).

Although the causes of student mental health issues are complex and diverse, course workload issues during the pandemic were important. Students report increased workloads related to online learning (Motz et al. Citation2021; Amri Citation2022). Surveys at different institutions confirmed these findings. At the University of Wisconsin, Madison, approximately 59 percent of students reported their fall 2020 course workload was less manageable than their spring 2020 course workload (see University of Wisconsin [Citation2021]). An October 2020 survey at Memorial University of Newfoundland found that students spent an average of 9.2 hours per course. Seventy-three percent of undergraduates and 50 percent of graduates found this to be more than they expected (see Hawkins [Citation2020]). At the University of Waterloo, 59.9 percent of all students reported spending more time on online courses than on-campus courses. Of these, 46.4 percent of full-time and 23.2 percent of part-time students said they spent much more time (see University of Waterloo [Citation2020]). A survey of undergraduates at the University of Maryland showed that academic demands were the leading reason why students did not seek mental health support services or treatment (see Oliveira et al. [Citation2020]).

Student surveys in many institutions show a perceived increase in student workload with online courses. We suspect that some of this “pandemic of busywork” (Motz et al. Citation2021) is attributable to faculty attempting various student engagement approaches in addition to their normal course material. This might now be a problem in face-to-face instruction with the addition of online assignments to conventional classroom pedagogy. Classroom time is stipulated for courses in institutions, but the time commitment expected of students outside the classroom in four out of five of our institutions (KSU, OC, SCC, UT) is left to the discretion of faculty or department. Will there now be a requirement to watch faculty-produced videos, and to complete multiple small-stakes online exercises, in addition to reading a textbook, attending a lecture, and completing assignments? How can students find time to make friends, talk about the issues of the day, exercise, and make enough money to pay for their tuition, laptop, high-speed Internet, day-to-day living expenses, and in many cases support their family as well?

The postpandemic period provides us with an opportunity to rethink what is taught and how it is taught (Fuller et al. Citation2021; McPhee Citation2021). There is a need for discussion within departments on the standardization of workload requirements between courses to enable students to appropriately manage their time. The problem extends beyond departments when a course is a component of several programs, each with different workload expectations. The requirement for a term paper at the end of a course, for example, might seem reasonable in the context of one course, but when students have multiple courses with term papers due in the same week, then not only is stress heightened, but performance declines in courses that do not have a term paper requirement.

In general, we have observed a trend of ongoing addition of material and assignments to the existing curriculum in recent years, evidenced by an increase in the size of textbooks (Day Citation2012). This might increase what some students learn, but an increase in workload will increase stress for many students. Learning geography should be enjoyable, not something that sends students to a counselor.

Inequities: There Is a Need to Address Inequities among Students

In our institutions and elsewhere (Barrot, Llenares, and del Rosario Citation2021; Richardson et al. Citation2021; Jenkins, Gardner, and Sun Citation2022), the pandemic revealed the nature and extent of inequities and barriers to higher education from race, gender, sexual orientation, disability, poverty, and whether one lives in a rural or urban area.

Internet access and the need for new computers and related technology are increasingly issues for concern as software becomes more sophisticated, especially with GIS and virtual field work requirements. Students in unstable housing conditions are particularly vulnerable to Internet access issues. These issues are especially of concern in the developing world, with inadequate electricity supply (Adarkwah Citation2021). In West Bengal, 31 percent of students solely relied on reading a textbook to keep up with their studies (Kapasia et al. Citation2020). In places with lockdowns or mobility restrictions, it was particularly difficult for students who did not have adequate Internet service at home (Barrot, Llenares, and del Rosario Citation2021). The digital divide is still an issue in North America, particularly among students with few resources who often depend on their institution for stable Internet connections and quiet study spaces (Quach and Chen Citation2021). At OC, many students logged into classes on multiple occasions as they struggled with Internet connections.

Many inequities were well known from previous surveys and studies (Lee Citation2004: Sólorzano, Villalpando, and Oseguera Citation2005), and some of these inequities were enhanced by reductions in social services (Farnish and Schoenfeld Citation2022). The pandemic provided both opportunities and challenges for faculty to build relationships with students in difficulty. The challenge is to design and instruct a more equitable course where every student can successfully engage with course content, and to cultivate relationships with students that lead to improvements in student success for all students, including underserved populations (Beschorner Citation2021). This is time-consuming and lacks recognition in the tenure and promotion process.

The pandemic also encouraged more dialogue between faculty and students with a disability. Accessibility services and similar departments continued to assess the requirements of students with disabilities during the pandemic and often did not reveal the nature of the disability to faculty. Facilities such as quiet rooms for supervised examinations were no longer available, though, and faculty arranged accommodations directly with the student. Some students voluntarily revealed the complex nature of their challenges, and sympathetic faculty better understood the barriers faced by students with disabilities. This knowledge makes it easier for caring faculty to better understand some of the issues students face. On the other hand, not all faculty have been accommodating to students, with occasional student concerns about faculty refusal to accommodate or the belittling of students with disabilities (D. C. Brooks Citation2021).

There is a risk that inequities will persist as future undergraduate cohorts will have some students who effectively missed a year or more of their secondary schooling due to the pandemic. Many universities and colleges adjusted their entrance requirements to facilitate recruitment, and some graduate programs dropped their GRE requirement (UT). It is possible that some students, especially those from less well-resourced schools, face challenges as they catch up.

Faculty: A Need for More Support and/or Adjustment in Institutional Expectations

Although the role of faculty as teachers, mentors, researchers, and administrators continued during the pandemic, the online pivot and its aftermath added multiple layers of complexity to the job.

New opportunities for research collaboration presented themselves after the online pivot. This article is an example of collective work by a group of authors who have never met personally as a group. There is an opportunity for “stand-alone geographers” to collaborate more with academics from different institutions, and to use online platforms for collaborative research and writing.

Although we have been unable to travel, we have been able to reach out to different parts of the world through video conferencing. We have been able to bring guest speakers into our classrooms, and attend more conferences, workshops, and seminars than we normally do. There are more online lecture series and conference opportunities available with low or free registration costs, no travel or accommodation expenses, and no visa issues, which have broadened participation in international conferences. There is also less time to commit to a conference, however. Freed of the constraints of geographic location, faculty are tempted to participate in too many conferences while continuing regular responsibilities. It is common that people attending an online conference are also multitasking (Niner and Wassermann Citation2021).

In general, workload increased for many faculty. New technologies had to be learned in workshops or on our own, courses had to be redesigned, new asynchronous materials developed, and online test banks constructed. There has also been a need to address student academic and nonacademic concerns (e.g., housing and food insecurity, lack of access to and experience with technology, employment and immigration concerns) and also to fill in for other faculty. Ambidextrous courses have been especially demanding. Some faculty have felt the need to immediately respond to student requests around the clock. Fortunately, communities of practice have been developed to share ideas and offer support (Donitsa-Schmidt and Ramot Citation2020), but that has also been a time commitment. All this has taken a toll. Students have observed that faculty sometimes ignore their e-mails, fail to maintain course LMS sites (D. C. Brooks Citation2021), and provide inadequate feedback on student assignments (Paris Citation2022). Additional research responsibilities along with other increases in workload could threaten the research–teaching nexus (Hordósy and McLean Citation2022).

For those in chair positions, the workload has become even more complex: guiding modality changes, ensuring proper training and consulting availability for faculty, coping with faculty and student health issues (in some cases ensuring that COVID tracing was adequate), continually realigning schedules to meet new needs, managing risk, and still moving forward on non-COVID related initiatives.

The faculty workload issue is not just a problem of the online pivot and its aftermath. Demands on faculty have grown in recent years as the scope of institutional management has broadened, and the number of managers and administrators at our institutions has increased (Zywicki and Koopman Citation2017; Stogner Citation2021). Each one of the new positions creates new work for faculty, with requests for more committee work, more outreach, more initiatives, more surveys, more data requests, more “opportunities” for service, and just more of everything. Meanwhile, there has been a long-term trend of reduced administrative support for faculty (OC).

The result of all these demands is that faculty are stressed. This affects some faculty more than others (Abilleira et al. Citation2021). Some people have observed forgetfulness and irritability in themselves and colleagues. There is a need for additional support and to rationalize and prioritize workloads. This is especially true for faculty in early career positions as they attempt to effectively allot time among varying workload model percentages for the three major areas of teaching, research, and service. Departments and institutions might have to adjust their expectations of faculty.

Employment Practices: There Is a Need to Move Faculty Away from Precarious Employment

Many faculty teaching at universities and colleges around the world are in precarious employment, a situation characterized by employment insecurity, income inadequacy, and a lack of rights and protections (Kreshpaj et al. Citation2020). The pandemic has produced significant financial stress for faculty in precarious employment (Malisch et al. Citation2020; Watermeyer et al. Citation2021), with day care, food, and housing security issues and a need to look after young children and elderly parents. In some cases, part-time faculty needed classes to pay their rent.

Some departments have been especially supportive of their part-time and contract faculty. Some departments were able to ensure that all non-tenure-track faculty could continue their employment in the face of declining enrollment (SCC). In other cases, however, budget constraints have reduced employment (UT).

The high costs of the pandemic borne by governments and institutions could result in future budget impacts on departments. This will affect all faculty, but it is important to particularly bear in mind the needs of those in precarious employment. To the extent that it is possible, we suggest that the needs of part-time faculty be respected in timetabling and course assignments, especially when there is a genuine demand for more faculty to handle the increased workload consequences of the online pivot on students’ learning and well-being. At the same time, we recognize the structural inequities of hiring practices that produce this undesirable and unfair situation.

Academic Freedom: Discretion and Tenure under Siege

Academic freedom, in its various aspects, has come under challenge during the pandemic. Within universities, some expressed frustration that responses to COVID-19 “were being made unilaterally by university leaders without staff consultation or input” in the United Kingdom (Watermeyer et al. Citation2021, 656). These responses include more micromanagement of teaching and assessment practices associated with the online pivot, undermining teachers’ freedom to teach in terms of “pedagogic self-governance” (Macfarlane Citation2021).

Elsewhere, the challenge to academic freedom comes in the form of governments taking advantage of COVID chaos when faculty were engrossed in the online pivot and other pandemic responses to launch surprise attacks on the institutional underpinnings supporting “the free search for truth and its free exposition” (American Association of University Professors n.d.).

For example, amid the added stresses of the pandemic, with minimal faculty participation, in the U.S. state of Georgia, the politically appointed Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia voted in October 2021 to change its posttenure review policy, making it possible to fire tenured faculty without due process of a dismissal hearing. This action effectively abolished tenure and led to the American Association of University Professors censuring Georgia’s university system (American Association of University Professors Citation2021).

Beyond Georgia, attempts to stifle academic freedom and censor faculty expertise in other U.S. states in 2021 include the University of Florida initially denying permission to three political scientists who wanted to serve as expert witnesses in a lawsuit challenging new voting restrictions in Florida; a bill recently introduced in the South Carolina legislature entitled the Cancelling Professor Tenure Act; a bill in Rhode Island that would prevent teaching “divisive concepts”; and a bill in Iowa threatening funding for higher education institutions that incorporated teaching about slavery (Whittington Citation2021). Earlier in 2021, the American Association of Geographers (AAG) sent a letter to the Chancellor of the University of Kansas regarding a recent decision by the Kansas Board of Regents that would allow the suspension and termination of tenured faculty. All these situations threaten academic freedom (Langham Citation2021).

Academic freedom is a complex and evolving concept (Axelrod Citation2021). It is generally not available to faculty in precarious employment, nor is it meant to promote racism, sexism, or harassment. The extent to which it allows cultural appropriation is unclear. Given our concerns for sociospatial variations, however, geographers can contribute significantly to the revelation of “the many contextual factors and diverse situations and relationships that can compromise [or, in some cases, promote] the existence and exercise of academic freedom” (Bartel Citation2019, 364).

Personal Life: It Is Healthy to Cultivate a Work–Life Balance

People’s experience of working from home varied. Some faculty lacked an appropriate workspace, found it difficult to work with children and partners around, and preferred the structure and social aspects of the workplace. As one journal editor framed it, “The lines between ‘work’ and ‘home’ have become so blurred that ‘work/life balance’ has become a laughable aspiration” (Marsh Citation2020, 141). It was nearly impossible to create any sense of balance, as faculty navigated the unpredictability of K–12 school, COVID exposure, and care of extended family. Faculty already disadvantaged by intersecting social identities, including their race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, age, family obligations and responsibilities, among others, were especially affected (Anwer Citation2020; D. Clark, Mickey, and Misra Citation2020; Neely and Lopez Citation2022). The emotional labor of managing one’s own feelings to manage the feelings of others (Hochschild Citation1983) also took its toll (Flynn and Noonan Citation2020; Littlejohn et al. Citation2021).

Some of us, however, have also found that it is good to spend more time at home with our partner and family. For some of us, the pandemic has been stressful but also reminded us of the need to strike a balance between our professional and personal lives. One described working from home as “spring training for retirement.”

Conclusions

Under current conditions of stress and uncertainty, can we encourage people and organizations toward meaningful change to the curriculum, pedagogy, student services, and employment practices? We think we can (). All faculty have a common experience on which they can build. This pandemic has been humbling for everyone. Now is the time to build a shared vision within departments, and work to build a future for geography in higher education. Implementation of the lessons described here requires three different types of activity.

Table 3 Lessons and their implementation

Individuals have a role to play. To the extent that it is determined by faculty, consideration should be given to the careful design and greater use of online delivery modes, greater use of the course LMS, modification of course curriculum and assessment, the development of more field work options within courses, respect for student privacy, and recognition and accommodation of challenges faced by individual students. Isolated faculty are encouraged to seek research opportunities through online collaborations. These suggestions are not intended to be prescriptive, and faculty should consider issues in the context of local and personal circumstances.

The pandemic has shown that departments need to have conversations about the expectations of students and faculty. We also need to discuss the role of precarious employment within the future of our discipline. This is both a fairness issue, and a strategic issue with respect to the unsustainable nature of part-time and contract positions as a hiring practice. We recognize the hard work put in by faculty in precarious employment, but in general students are more likely to be inspired by well-supported faculty, and more likely to become professional geographers themselves if they can see a future for themselves. Some of these issues will likely need to be elevated to a higher administrative level. Consideration of departmental expectations of students requires dialogue between students and departments through student societies, liaison committees, and/or student surveys.

Some of the lessons raise systemic, institutional, and structural issues that are unlikely to be resolved by individuals or departments. Nothing makes eyes glaze over faster than strategic planning discussions, and yet it is institutional strategic planning that ultimately controls and influences decisions about the hiring and workload practices that produce structural inequality and unfairness. It is critical that we develop institutional strategic plans that reflect fairness and sustainability. Only then is it possible to authoritatively call out university and college leadership if they fail to respond to that strategic initiative.

Better postsecondary educational practices might be one of the few desirable outcomes of the pandemic.

Acknowledgments

The literature review was assisted by Julie McDaniel, Student Success Librarian at Sinclair Community College. Stephanie Bunclark and Todd Redding of Okanagan College contributed observations and discussion. The pandemic has been hard for everyone and we would like to acknowledge family and friends we lost during this period: Kathleen Behan, Moon Hing Chan, Kai Wing Choy, John Clark, Randall McDaniel, Lynn Rigsbee, Álvaro Sánchez-Crispin, and Billie Lee Turner.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Terence Day

TERENCE DAY is a Professor in the Department of Geography, Earth and Environmental Science, Okanagan College, Kelowna, BC V1Y 4X8, Canada. E-mail: [email protected]. He is a physical geographer with research interests in undergraduate teaching and learning, and the scope and nature of physical geography.

Calvin King Lam Chung

CALVIN KING LAM CHUNG is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography and Resource Management, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include state spatial restructuring, politics of planning, and political ecology in China.

William E. Doolittle

WILLIAM E. DOOLITTLE is the Erich W. Zimmermann Regents Professor of Geography, and Chair of the Department of Geography and the Environment, The University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712. E-mail: [email protected]. His research focuses on ancient and historical agricultural landscapes and irrigation technology of México and the U.S. Southwest.

Jacqueline Housel

JACQUELINE HOUSEL is a Professor and Chair of the Department of Sociology, Geography and Social Work, Sinclair Community College, Dayton, OH 45402. E-mail: [email protected]. She is a community geographer with interests in local immigration, racial and ethnic identity, policing, and undergraduate teaching and learning.

Paul N. McDaniel

PAUL N. McDANIEL is an Associate Professor of Geography in the Department of Geography and Anthropology, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA 30144. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include the geography of place-branding as it relates to the causes, processes, and implications of immigration to urban regions, with emphasis on immigrant settlement, adjustment, integration, and receptivity in cities and metropolitan areas.

Literature Cited

- Abilleira, M. P., M. L. Rodicio-García, M. P. Ríos-de Deus, and M. J. Mosquera-González. 2021. Technostress in Spanish university teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology 12:617650. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.617650.

- Adarkwah, M. A. 2021. “I’m not against online teaching, but what about us?”: ICT in Ghana post Covid-19. Education and Information Technologies 26 (2):1665–85. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10331-z.

- American Association of University Professors. n.d. 1940 statement of principles on academic freedom and tenure. Accessed June 7, 2022. https://www.aaup.org/report/1940-statement-principles-academic-freedom-and-tenure.

- American Association of University Professors. 2021. University system of Georgia eviscerates tenure. AAUP Updates, December 8. Accessed June 7, 2022. https://www.aaup.org/news/university-system-georgia-eviscerates-tenure#.Yp-qdhrMI2w.

- Amri, M. 2022. Rethinking public health pedagogy: Lessons learned and pertinent questions. University of Toronto Journal of Public Health 3 (2). doi:10.33137/utjph.v3i2.37285.

- Anderson, K., P. Martin, and J. Nevins. 2022. Introduction and abridged text of lecture: Laggards or leaders: Academia and its responsibility in delivering on the Paris commitments. The Professional Geographer 74 (1):122–26. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2021.1915809.

- Anwer, M. 2020. Academic labor and the global pandemic: Revisiting life–work balance under COVID-19. Susan Bulkeley Butler Center for Leadership Excellence and ADVANCE Working Paper Series 3 (2):5–13.

- Axelrod, P. 2021. Academic freedom and its constraints: A complex history. Canadian Journal of Higher Education 51:51–66. doi: 10.47678/cjhe.vi0.189143.

- Bain, K. 2004. What the best college teachers do. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Barak, M. 2017. Science teacher education in the twenty-first century: A pedagogical framework for technology-integrated social constructivism. Research in Science Education 47 (2):283–303. doi: 10.1007/s11165-015-9501-y.

- Barrot, J. S., I. I. Llenares, and L. S. del Rosario. 2021. Students’ online learning challenges during the pandemic and how they cope with them: The case of the Philippines. Education and Information Technologies 26 (6):7321–38. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10589-x.

- Bartel, R. 2019. Academic freedom and an invitation to promote its advancement. Geographical Research 57 (3):359–67. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12350.

- Beschorner, B. 2021. Revisiting Kuo and Belland’s exploratory study of undergraduate students’ perceptions of online learning: Minority students in continuing education. Educational Technology Research and Development 69 (1):47–50. doi: 10.1007/s11423-020-09900-3.

- Boehm, R. G., M. Solem, and J. Zadrozny. 2018. The rise of powerful geography. The Social Studies 109 (2):125–35. doi: 10.1080/00377996.2018.1460570.

- Boström, L., C. Charlotta, U. Damber, and U. Gidlund. 2021. A rapid transition from campus to emergent distant education: Effects on students’ study strategies in higher education. Education Sciences 11 (11):721. doi: 10.3390/educsci11110721.

- Bretag, T., R. Harper, M. Burton, C. Ellis, P. Newton, P. Rozenberg, S. Saddiqui, and K. van Haeringen. 2019. Contract cheating: A survey of Australian university students. Studies in Higher Education 44 (11):1837–56. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2018.1462788.

- Brooks, D. C. 2021. Student experiences learning with technology in the pandemic. Research report, EDUCAUSE, Boulder, CO. Accessed July 30, 2021. https://www.educause.edu/ecar/research-publications/2021/student-experiences-learning-with-technology-in-the-pandemic/introduction-and-key-findings.

- Brooks, R., A. Fuller, and J. L. Waters, eds. 2012. Changing spaces of education: New perspectives on the nature of learning. London and New York: Routledge.

- Browning, M. H. E. M., L. R. Larson, I. Sharaievska, A. Rigolon, O. McAnirlin, L. Mullenbach, S. Cloutier, T. M. Vu, J. Thomsen, N. Reigner, et al. 2021. Psychological impacts from COVID-19 among university students: Risk factors across seven states in the United States. PLoS ONE 16 (1):e0245327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245327.

- Bryson, J. R., L. Andres, A. Ersoy, and L. Reardon. 2021. A year into the pandemic: Shifts, improvisations and impacts for places, people and policy. In Living with pandemics: Places, people and policy, ed J. R. Bryson, L. Andres, A. Ersoy, and L. Reardon, 2–35. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Burke, L. 2021. 10 months in. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2021/01/22/survey-outlines-student-concerns-10-months-pandemic.

- Cavus, N., Y. B. Mohammed, and M. N. Yakubu. 2021. Determinants of learning management systems during COVID-19 pandemic for sustainable education. Sustainability 13 (9):5189. doi: 10.3390/su13095189.

- Clark, C., and B. P. Wilson. 2017. The potential for university collaboration and online learning to internationalise geography education. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 41 (4):488–505. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2017.1337087.

- Clark, D., E. L. Mickey, and J. Misra. 2020. Reflections on institutional equity for faculty in response to COVID-19. Susan Bulkeley Butler Center for Leadership Excellence and ADVANCE Working Paper Series 3 (2):92–114.

- Copeland, W. E., E. McGinnis, Y. Bai, Z. Adams, H. Nardone, V. Devadanam, J. Rettew, and J. J. Hudziak. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 60 (1):134–41.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.466.

- Day, T. 2012. Undergraduate teaching and learning in physical geography. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 36 (3):305–32. doi: 10.1177/0309133312442521.

- Day, T., I.-C. C. Chang, C. K. L. Chung, W. E. Doolittle, J. Housel, and P. N. McDaniel. 2021. The immediate impact of COVID-19 on postsecondary teaching and learning. The Professional Geographer 73 (1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2020.1823864.

- Department of Education and Burghart, A. 2021. Essay mills to be banned under plans to reform post-16 education. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/essay-mills-to-be-banned-under-plans-to-reform-post-16-education.

- de Paz-Álvarez, M. I., T. G. Blenkinsop, D. M. Buchs, G. E. Gibbons, and L. Cherns. 2022. Virtual field trip to the Esla Nappe (Cantabrian Zone, NW Spain): Delivering traditional geological mapping skills remotely using real data. Solid Earth.13 (1):1–14. doi: 10.5194/se-13-1-2022.

- Dikaya, L. A., G. Avanesian, I. S. Dikiy, V. A. Kirik, and V. A. Egorova. 2021. How personality traits are related to the attitudes toward forced remote learning during COVID-19: Predictive analysis using generalized additive modeling. Frontiers in Education 6:629213. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.629213.

- Donitsa-Schmidt, S., and R. Ramot. 2020. Opportunities and challenges: Teacher education in Israel in the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Education for Teaching 46 (4):586–95. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2020.1799708.

- Donovan, W. J. 2020. The whiplash of a COVID-19 teaching pivot and the lessons learned for the future. Journal of Chemical Education 97 (9):2917–21. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00755.

- Duran, A., and A. M. Núñez. 2021. Food and housing insecurity for Latinx/a/o college students: Advancing an intersectional research agenda. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 20 (2):134–48. doi: 10.1177/1538192720963579.

- Ellis, C., K. van Haeringen, R. Harper, T. Bretag, I. Zucker, S. McBride, P. Rozenberg, P. Newton, and S. Saddiqui. 2020. Does authentic assessment assure academic integrity? Evidence from contract cheating data. Higher Education Research & Development 39 (3):454–69. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2019.1680956.

- Farnish, K. A., and E. A. Schoenfeld. 2022. Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for youth housing and homelessness services. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s10560-022-00830-y.

- Flynn, S., and G. Noonan. 2020. Mind the gap: Academic staff experiences of remote teaching during the Covid 19 emergency. All Ireland Journal of Higher Education 12 (3):1–19.

- France, D., and M. Haigh. 2018. Fieldwork@40: Fieldwork in geography higher education. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 42 (4):1–514. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2018.1515187.

- Fruehwirth, J. C., S. Biswas, and K. M. Perreira. 2021. The Covid-19 pandemic and mental health of first-year college students: Examining the effect of Covid-19 stressors using longitudinal data. PLoS ONE 16 (3):e0247999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247999.

- Fuller, S., K. Ruming, A. Burridge, R. Carter-White, D. Houston, L. Kelly, K. Lloyd, A. McGregor, J. McLean, F. Miller, et al. 2021. Delivering the discipline: Teaching geography and planning during COVID-19. Geographical Research 59 (3):331–40. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12472.

- Gardner, L. 2020. Covid-19 has forced higher ed to pivot to online learning. Here are 7 takeaways so far. The Chronicle of Higher Education, March 20.

- Gaudry, A., and D. Lorenz. 2018. Indigenization as inclusion, reconciliation, and decolonization: Navigating the different visions for indigenizing the Canadian academy. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 14 (3):218–27. doi: 10.1177/1177180118785382.

- Gibbes, C., and E. Skop. E 2022. Disruption, discovery, and field courses: A case study of student engagement during a global pandemic. The Professional Geographer 74 (1):31–40. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2021.1970593.

- Gierdowski, D. C. 2019. 2019 study of undergraduate students and information technology. Research report, EDUCAUSE, Boulder, CO. Accessed July 30, 2021. https://library.educause.edu/resources/2019/10/2019-study-of-undergraduate-students-and-information-technology.

- Godlewska, A., W. Beyer, S. Whetstone, L. Schaefli, J. Rose, B. Talan, S. Kamin-Patterson, C. Lamb, and M. Forcione. 2019. Converting a large lecture class to an active blended learning class: Why, how, and what we learned. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 43 (1):96–115. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2019.1570090.

- Hawkins, T. 2020. Remote instruction student survey: Results summary. Memorial University of Newfoundland. https://citl.mun.ca/Student_experience_survey_results.pdf

- Hill, J., H. Walkington, and S. Dyer. 2019. Teaching, learning and assessing in geography: A foundation for the future. In Handbook for teaching and learning in geography, ed. H. Walkington, J. Hill, and S. Dyer, 474–86. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Hochschild, A. R. 1983. The managed heart: The commercialization of human feeling, Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

- Hodges, C., S. Moore, B. Lockee, T. Trust, and A. Bond. 2020. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review, March 27. Accessed June 7, 2022. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning.

- Hollis, L. P. 2018. Ghost‐students and the new wave of online cheating for community college students. New Directions for Community Colleges 2018 (183):25–34. doi: 10.1002/cc.20314.

- Hordósy, R., and M. McLean. 2022. The future of the research and teaching nexus in a post-pandemic world. Educational Review 74 (3):378–401. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2021.2014786.

- Jenkins, B. M., T. E. Gardner, and W. Sun. 2022. African American college students’ stress management and wellness during COVID-19. In Higher education implications for teaching and learning during COVID-19, ed. M. G. Strawser, 65–80. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

- Kapasia, N., P. Paul, A. Roy, J. Saha, A. Zaveri, R. Mallick, B. Barman, P. Das, and P. Chouhan. 2020. Impact of lockdown on learning status of undergraduate and postgraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal, India. Children and Youth Services Review 116:105194. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105194.

- Kim, M. 2022. Developing pre-service teachers’ fieldwork pedagogical and content knowledge through designing enquiry-based fieldwork. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 46 (1):61–79. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2020.1849065.

- Kreshpaj, B., C. Orellana, B. Burström, L. Davis, T. Hemmingsson, G. Johansson, G. K. Kjellberg, J. Jonsson, D. H. Wegman, and T. Bodin. 2020. What is precarious employment? A systematic review of definitions and operationalizations from quantitative and qualitative studies. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 46 (3):235–47. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3875.

- Lancaster, T., and C. Cotarlan. 2021. Contract cheating by STEM students through a file sharing website: A Covid-19 pandemic perspective. International Journal of Education Integrity 17 (3):1–16. doi: 10.1007/s40979-021-00070-0.

- Langham, G. 2021. In Kansas, an early warning for higher education and geography. American Association of Geographers, Washington, DC. Accessed June 7, 2022. https://www.aag.org/in-kansas-an-early-warning-for-higher-education-and-geography/.

- Lederer, A. M., M. T. Hoban, S. K. Lipson, S. Zhou, and D. Eisenberg. 2021. More than inconvenienced: The unique needs of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education 48 (1):14–19. doi: 10.1177/1090198120969372.

- Lee, J. 2004. Multiple facets of inequity in racial and ethnic achievement gaps. Peabody Journal of Education 79 (2):51–73. doi: 10.1207/s15327930pje7902_5.

- Lewin, J., and K. J. Gregory. 2019. Evolving curricula and syllabi—Challenges for physical geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 43 (1):7–23. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2018.1554631.

- Li, Y., S. Krause, A. McLendon, and I. Jo. 2022. Teaching a geography field methods course amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Reflections and lessons learned. Journal of Geography in Higher Education. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2022.2041571.

- Linden, B., R. Boyes, and H. Stuart. 2021. Cross-sectional trend analysis of the NCHA II survey data on Canadian post-secondary student mental health and wellbeing from 2013 to 2019. BMC Public Health 21 (1):590. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10622-1.

- Littlejohn, A., L. Gourlay, E. Kennedy, K. Logan, T. Neumann, M. Oliver, J. Potter, and J. A. Rode. 2021. Moving teaching online: Cultural barriers experienced by university teachers during Covid-19. Journal of Interactive Media in Education 2021 (1):7–15. doi: 10.5334/jime.631.

- MacDonald, G. 2022. Climate change: Geography’s debt and geography’s dilemma. The Professional Geographer 74 (1):137–38. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2021.1915815.

- Macfarlane, B. 2021. Why choice of teaching method is essential to academic freedom: A dialogue with Finn. Teaching in Higher Education. Advance Online Publication. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2021.2007473.

- Malisch, J. L., B. N. Harris, S. M. Sherrer, K. A. Lewis, S. L. Shepherd, P. C. McCarthy, J. L. Spott, E. P. Karam, N. Moustaid-Moussa, J. M. Calarco, et al. 2020. Opinion: In the wake of COVID-19, academia needs new solutions to ensure gender equity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117 (27):15378–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010636117.

- Marazziti, D., P. Cianconi, F. Mucci, L. Foresi, I. Chiarantini, and A. Della Vecchia. 2021. Climate change, environment pollution, COVID-19 pandemic and mental health. The Science of the Total Environment 773:145182. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145182.

- Marsh, M. 2020. Editorial. Journal of Geography 119 (5):141. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2020.1814054.

- McPhee, S. R. 2021. Advocating for blended pedagogy as a shift to more holistic inclusive geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education. Advance Online Publication. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2021.1957802.

- Mheidly, N., M. Y. Fares, and J. Fares. 2020. Coping with stress and burnout associated with telecommunication and online learning. Frontiers in Public Health 8:574969. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.574969.

- Mohammadi, M. K., A. A. Mohibbi, and M. H. Hedayati. 2021. Investigating the challenges and factors influencing the use of the learning management system during the Covid-19 pandemic in Afghanistan. Education and Information Technologies 26 (5):5165–98. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10517-z.

- Moll, H. L. 2020. Leveling up grades: A pilot study of student motivation when an entry-level geography course uses point-accrual class assessment. Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers 82 (1):145–59. doi: 10.1353/pcg.2020.0008.

- Moorman, L., J. Evanovitch, and T. Muliaina. 2021. Envisioning indigenized geography: A two-eyed seeing approach. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 45 (2):201–20. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2021.1872060.

- Motz, B. A., J. D. Quick, A. S. Morrone, R. Flynn, and F. Blumberg. 2022. When online courses became the student union: Technologies for peer interaction and their association with improved outcomes during COVID-19. Technology, Mind, and Behavior 3 (1). doi: 10.1037/tmb0000061.

- Motz, B. A., J. D. Quick, J. A. Wernert, and T. A. Miles. 2021. A pandemic of busywork: Increased online coursework following the transition to remote instruction is associated with reduced academic achievement. Online Learning 25 (1):70–85. doi: 10.24059/olj.v25i1.2475.

- Neely, A. H., and P. J. Lopez. 2022. The differential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in geography in the United States. The Professional Geographer. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2021.2000448.

- Newton, P. M. 2018. How common is commercial contract cheating in higher education and is it increasing? A systematic review. Frontiers in Education 3:67. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00067.

- Niner, H. J., and S. M. Wassermann. 2021. Better for whom? Leveling the injustices of international conferences by moving online. Frontiers in Marine Science 8:146. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.638025.

- Nursey-Bray, M. 2019. Uncoupling binaries, unsettling narratives and enriching pedagogical practice: Lessons from a trial to indigenize geography curricula at the University of Adelaide, Australia. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 43 (3):323–42. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2019.1608921.

- Oliveira, M., M. Masters, M. Clark, A. Lancaster, B. Akramov, S. Tullier, B. Supple, C. Joshi, Y.-W. Wang, S. La Voy, A. Socha, D. Glazer, J. Edwards, A. Donlan, and M. Patel. 2020. Fall 2020 student experience survey: Undergraduate student initial results. College Park, MD: University of Maryland. https://svp.umd.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/Fall%202020%20Student%20Survey%20-%20undergraduates%20-%20initial%20results%20-%20Nov%202020.pdf

- O’Neill, K., N. Lopes, J. Nesbit, S. Reinhardt, and K. Jayasundera. 2021. Modeling undergraduates’ selection of course modality: A large sample, multi-discipline study. The Internet and Higher Education 48:100776. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2020.100776.

- Paris, B. M. 2022. Instructors’ perspectives of challenges and barriers to providing effective feedback. Teaching & Learning Inquiry 10. doi: 10.20343/teachlearninqu.10.3.

- Petersen, B., and J. R. Barnes. 2020. From hopelessness to transformation in geography classrooms. Journal of Geography 119 (1):3–11. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2019.1566395.

- Pine, B. J., and J. H. Gilmore. 2011. The experience economy. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Quach, A., and V. T. Chen. 2021. Inequalities on the digital campus. Dissent 68 (4):57–61. doi: 10.1353/dss.2021.0059.

- Raath, S., and A. Golightly. 2017. Geography education students’ experiences with a problem-based learning fieldwork activity. Journal of Geography 116 (5):217–25. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2016.1264059.

- Rauer, J. N., M. Kroiss, N. Kryvinska, N. C. Engelhardt-Nowitzki, and M. Aburaia. 2021. Cross-university virtual teamwork as a means of internationalization at home. The International Journal of Management Education 19 (3):100512. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100512.

- Raza, S. A., W. Qazi, K. A. Khan, and J. Salam. 2021. Social isolation and acceptance of the learning management system (LMS) in the time of COVID-19 pandemic: An expansion of the UTAUT model. Journal of Educational Computing Research 59 (2):183–208. doi: 10.1177/0735633120960421.

- Revell, A., and E. Wainwright. 2009. What makes lectures “unmissable”? Insights into teaching excellence and active learning. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 33 (2):209–23. doi: 10.1080/03098260802276771.

- Richardson, E., D. Fisher, D. Oetjen, R. Oetjen, J. Gordon, S. Conklin, and E. Knowles. 2021. In transition: Supporting competency attainment in Black and Latinx students. Competency-Based Education 6:e01240. doi: 10.1002/cbe2.1240.

- Schultz, R. B., and M. N. DeMers. 2020. Transitioning from emergency remote learning to deep online learning experiences in geography education. Journal of Geography 119 (5):142–6. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2020.1813791.

- Simm, D., and A. Marvell. 2017. Creating global students: Opportunities, challenges and experiences of internationalizing the geography curriculum in higher education. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 41 (4):467–74. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2017.1373332.

- Sólorzano, D. G., O. Villalpando, and L. Oseguera. 2005. Educational inequities and Latina/o undergraduate students in the United States: A critical race analysis of their educational progress. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 4 (3):272–94. doi: 10.1177/1538192705276550.

- Stogner, J. 2021. Academia shrugs: How addressing systemic barriers to research efficiency and quality teaching would allow criminology to make a broader difference. American Journal of Criminal Justice. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09598-2.

- Tanczer, L. M., R. J. Deibert, D. Bigo, M. I. Franklin, L. Melgaço, D. Lyon, B. Kazansky, and S. Milan. 2020. Online surveillance, censorship, and encryption in academia. International Studies Perspectives 21 (1):1–36. doi: 10.1093/isp/ekz016.

- Thomas, M., and J. R. Bryson. 2021. Combining proximate with online learning in real-time: Ambidextrous teaching and pathways towards inclusion during COVID-19 restrictions and beyond. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 45 (3):446–64. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2021.1900085.

- Thomas, M., T. Gonondo, P. Rautenbach, K. Seeley, A. Shkurti, A. Thomas, and H. Westlake. 2021. Living with pandemics in higher education: People, place and policy. In Living with pandemics: Places, people and policy, ed. J. R. Bryson, L. Andres, A. Ersoy, and L. Reardon, 47–58. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Torjesen, I. 2021. Covid-19 will become endemic but with decreased potency over time, scientists believe. BMJ: British Medical Journal (Online) 372:n494. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n494.

- Tortorelli, C., P. Choate, M. Clayton, N. E. Jamal, S. Kaur, and K. Schantz. 2021. Simulation in social work: Creativity of students and faculty during COVID-19. Social Sciences 10 (1):7. doi: 10.3390/socsci10010007.

- University of Victoria. n.d. Invigilation Brightspace exams at UVic: Zoom and Respondus options. Accessed July 22, 2022. https://onlineacademiccommunity.uvic.ca/TeachAnywhere/2020/10/21/invigilating-online-exams-at-uvic/

- University of Waterloo. 2020. Spring student survey. Accessed July 22, 2022. https://uwaterloo.ca/coronavirus/sites/ca.coronavirus/files/uploads/files/spring_2020_student_survey_results_final_final-ua.pdf

- University of Wisconsin. 2021. Undergraduate student needs and experiences survey. Accessed July 21, 2022. https://advising.wisc.edu/facstaff/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Fall-2020-Student-Survey-Slides-qualitative-1.pdf

- Villani, L., R. Pastorino, E. Molinari, F. Anelli, W. Ricciardi, G. Graffigna, and S. Boccia. 2021. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological well-being of students in an Italian university: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Globalization and Health 17 (1):39. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00680-w.

- Walkington, H., S. Dyer, M. Solem, M. Haigh, and S. Waddington. 2018. A capabilities approach to higher education: Geocapabilities and implications for geography curricula. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 42 (1):7–24. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2017.1379060.

- Wang, X., C. P. Van Elzakker, and M. J. Kraak. 2017. Conceptual design of a mobile application for geography fieldwork learning. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 6 (11):355. doi: 10.3390/ijgi6110355.

- Watermeyer, R., K. Shankar, T. Crick, C. Knight, F. McGaughey, J. Hardman, V. R. Suri, R. Chung, and D. Phelan. 2021. “Pandemia”: A reckoning of UK universities’ corporate response to COVID-19 and its academic fallout. British Journal of Sociology of Education 42 (5–6):651–66. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2021.1937058.

- Welsh, K. E., A. L. Mauchline, D. France, V. Powell, W. B. Whalley, and J. Park. 2018. Would bring your own device (BYOD) be welcomed by undergraduate students to support their learning during fieldwork? Journal of Geography in Higher Education 42 (3):356–71. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2018.1437396.

- Whalley, B., D. France, J. Park, A. Mauchline, and K. Welsh. 2021. Towards flexible personalized learning and the future educational system in the fourth industrial revolution in the wake of Covid-19. Higher Education Pedagogies 6 (1):79–99. doi: 10.1080/23752696.2021.1883458.

- Whittington, K. E. 2021. The intellectual freedom that made public colleges great is under threat. Washington Post, December 15. Accessed June 7 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/12/15/academic-freedom-crt-public-universities/.

- Williams, J., and W. Love. 2022. Low-carbon research and teaching in geography: Pathways and perspectives. The Professional Geographer 74 (1):41–51. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2021.1977156.