?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has been pouring into China for decades. This article analyzes the spatial distribution and mechanism of FDI inflows to Chinese city-regions, combining location theories with the Chinese context. It provides a fresh perspective for understanding spatial FDI inflows in China. The spatial pattern of significant clustering features in FDI inflows remains, but it has shown a weakening trend over the past two decades. The Yangtze River Delta has grown as the largest agglomeration region of FDI in China. The great regional development in midwest China has brought large amounts of FDI to inland cities as well. These are atypical cases, though, as spatial dependence of FDI inflows based on geographic proximity is insignificant on a national scale. Local economic factors like energy supply, market consumption, and labor wages play roles in the spatial FDI inflows. This work can enrich the research practice and deepen the knowledge of spatial inequalities of FDI in the Chinese context.

外国直接投资(FDI)涌入中国已经有几十年的历史。本文结合区位理论和中国国情, 分析了FDI进入中国城市的空间分布和机制。本文为理解中国FDI的空间输入提供了新视角。过去二十年中, 具有显著集群特征的FDI流入空间格局仍然存在, 但呈现减弱趋势。长三角地区已成为中国最大的FDI聚集区。中国中西部大开发也给内陆城市带来了大量FDI。然而, 这些例子都不具有典型性, 因为在全国范围内基于地理邻近性的FDI流入空间依赖性并不显著。能源供应、市场消费和劳动力工资等地方经济因素, 影响了FDI的空间流入。本文丰富了研究实践, 加强了对中国FDI空间不均衡性的认识。

La inversión foránea directa (FDI) lleva décadas entrando a chorros a China. Este artículo analiza la distribución espacial y el mecanismo de entrada de los flujos de FDI a las ciudades-región chinas, combinando las teorías locacionales con el contexto chino. El artículo proporciona una perspectiva fresca para entender los flujos de FDI a China. Se mantiene el patrón espacial de los rasgos de agrupación significativos en los flujos de FDI, pero aquel muestra una tendencia de debilitamiento durante las dos últimas décadas. El delta del Rio Yangtzé se ha convertido en la región de mayor aglomeración de FDI de ese país. El gran desarrollo regional en el medio oeste de China ha atraído también grandes cantidades de FDI a las ciudades del interior. No obstante, estos casos son atípicos en cuanto que la dependencia espacial de las entradas de FDI basada en proximidad geográfica es insignificante a escala nacional. Los factores económicos locales, como el suministro de energía, mercado de consumo y los salarios de la mano de obra, desempeñan un papel en las entradas espaciales de las FDI. Este trabajo puede enriquecer la práctica de la investigación y ahondar en el conocimiento de las desigualdades espaciales de la FDI en el contexto chino.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) plays an important role in the economic development of China. As a growth engine, FDI has spurred China’s productive capacity, technological progress, and international trade (Fan, He, and Kwan Citation2019; Y. Hu, Fisher-Vanden, and Su Citation2020; Kim and Xin Citation2021). The market opening and attracting foreign capital are crucial components of China’s development strategy. In the early 1990s, China had become the largest recipient of FDI in the developing world (Sun Citation1998). After joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2002, China surpassed the United States as the country with the most foreign investment inflow and it has remained at the forefront globally ever since. According to the World Investment Prospects Survey (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) in the past ten years, China has consistently been one of the most attractive destinations for multinational capital. In 2017 through 2019, China has grown as a major investment destination, second only to the United States and clearly ahead of other economic entities.

The investment location, associated with labor availability, energy supply, or transport convenience, can affect the cost, efficiency, and profitability of foreign-funded enterprises. A series of factors have proven the positive roles in attracting FDI, including economic growth, natural resources, the size of markets, the real exchange rate, and policy favors (Alfalih and Hadj Citation2020; Wako Citation2021). The institutional environment in terms of trade openness, domestic credit, regulation, or rules particularly acts as a differentiator in countries’ attractiveness for FDI (Bailey Citation2018; Nguyen et al. Citation2018; Bhasin and Garg Citation2020). Numerous studies have explored the international or global flows of FDI, but the regional or spatial patterns and mechanisms within the host country are far less known. The particularity of China’s domestic economic development and regional differences could cause extra effects on the location choice of FDI. Local economic factors of Chinese subnational areas (provinces or prefectures) can influence the regional strategy and spatial layout of multinationals on the national scale. China has unique coastal–inland disparities and geographic inequalities in a wider sense (Hao and Wei Citation2010; Li and Fang Citation2014; Liao, Wei, and Huang Citation2020). The spatial distribution of FDI in China, therefore, might show some patterns different from those of other countries. At the same time, regional development strategies, planning, or projects can cause the spatial bias of FDI locations, and it could change at different time frames.

The issues about spatial inequalities of FDI in China have gotten scholars’ attention (L. Zhang and Wei Citation2015, Citation2017; Huang and Wei Citation2016). Geographic proximity is regarded as a factor that shapes regional or spatial linkages of FDI (Zhao, Chan, and Chan Citation2012; Schiller, Burger, and Karreman Citation2015). The investment bases first opened for foreign capital, such as Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and Xiamen, are port cities close to Hong Kong and Southeast Asia. In the early Chinese reform period, most of Hong Kong’s manufacturing industries moved to China and, in particular, to the nearby Pearl River Delta, which formed a renowned regional production model, namely “front shop, back factories” (Yeh Citation2012; Yuan Citation2021). The connotation of geographic proximity might go beyond physical distance, involving common cultural groups and identity recognition. The investment boom among Southeast Asian Chinese businessmen once helped the development of their hometowns located in the southern coastal areas of China (W. Wang and Lin Citation2008). On the other hand, from an economic perspective, the agglomeration economy and positive externalities could motivate multinationals to colocate production facilities and drive their investment decisions in surrounding areas (He Citation2002, Citation2003; Tuan and Ng Citation2003; Y. Chen Citation2009). The effect tends to diminish as distance increases. Whether geographic proximity of FDI is universal across the country, however, rather than in a few particular cases or within a certain region, remains to be tested. It is noteworthy that with the institutional reforms, Chinese FDI policies and regulation have changed over time (C. Chen Citation2018; J. Hu Citation2020). Little mandatory regulation has remained for multinationals’ and FDI’s location selection nationwide. Under the circumstances, the spatial interaction between local economic factors and FDI inflows requires clarification in logics. It is already suitable for quantitative assessment. In this article, we focus on the spatial distribution of FDI inflows in China since it joined the WTO. It will unveil the distribution patterns, trends, and linkage with regional development. The role of geographic proximity in the location choice of FDI will be assessed on a national scale, based on a spatial regression model. The regression analysis will also indicate the contribution of local economic factors to FDI inflows. This research covers the three dimensions that affect spatial FDI inflows: regional development, local economic factors, and geographic proximity. The integrated framework helps to generate novel insights and enrich relevant literatures.

Theoretical Framework

Cross-national flows of FDI have garnered the attention of scholars for a long time, and given birth to some classic theories. Hymer first put forward the monopolistic advantage theory in his PhD dissertation, “The International Operations of National Firms” (Buckley Citation2006, Citation2011). He argued that a direct foreign investor possesses some proprietary or monopolistic advantage not available to local firms, such as economies of scale, superior technology, or superior knowledge in marketing, management, or finance. Dunning (Citation1988, Citation2001) provided an eclectic response by bringing the competing theories together to form a single theory, or paradigm as it is more often referred to. The basic premise of Dunning’s paradigm is that it links together Hymer’s ownership advantages with the internalization school, and at the same time adds a locational dimension to the theory, which at the time had not been fully explored (Jones and Wren Citation2016). Dunning’s “investment development path (IDP)” theory and its latest version are implicitly built on the notion that the global economy is necessarily hierarchical in terms of the various stages of economic development in which its diverse constituent nations are situated (Dunning and Narula Citation1996; Dunning and Lundan Citation2008). Porter (Citation1986) believed that besides comparative advantages among various domestic industries, there are competitive advantages among the same industries of different countries. In Porter’s (Citation1998) book The Competitive Advantage of Nations focused on the role of geographic location in competitive advantage. It conveys a business concept that companies can extend their activities to several different locations, and through global network coordination, let activities in different locations generate potential competitive advantages. Along competitive advantage theories, Ozawa (Citation1992, Citation2007) proposed that the international direct investment model should be a cross-border capital flow that is compatible with changes in the countries’ economic structure, which poses transnational replacement and transfer of industries.

In the Chinese context, regional and spatial inequality of FDI distribution has been given particular attention. It is regarded as a result of institutional environment and unbalanced economic development. Various special economic zones, development zones, and industrial parks established in the process of reform and opening up have become gathering hubs for foreign-funded enterprises in China (Mah Citation2008; Dennis Wei, Lu, and Chen Citation2009; Tao and Yuan Citation2019). Zhao, Chan, and Chan (Citation2012) surveyed the spatial and sectoral distribution of FDI in China from the 1990s to 2000s. They found FDI had shifted to the Yangtze River Delta and the Bohai Economic Rim in the early years of this century, and Guangdong and Jiangsu are the two major recipient areas of FDI. Most FDI in China has been in the manufacturing sector, making China well-known as the “world factory of manufacturing.” Huang and Wei (Citation2016) believed the spatial inequality features of FDI in China are affected by three factors: institutional change, agglomeration economies, and market access. With the rise of Chinese urban economies, foreign hypermarket retailers entering China became an emerging part of FDI in the 2010s. L. Zhang and Wei (Citation2015) examined the spatial penetration and local embeddedness of foreign hypermarket retailers in China. They found the spatial expansion of foreign hypermarket retailers in two directions: from the eastern costal region to the central and western hinterland, and along China’s urban hierarchy from larger cities to smaller cities. Although home economies greatly influenced their initial strategies, foreign hypermarket retailers are constantly adjusting to better embed in the Chinese market. L. Zhang and Wei (Citation2017) also noticed the spatial inequality and dynamics of foreign hypermarket retailers in China. Leading foreign retailers have first-city and city size preferences in their provincial expansions in China. The relative gaps in foreign hypermarkets among Chinese regions are narrowing, whereas the absolute gaps are widening.

The economic causes of FDI locations in China are derived from the endowment conditions in different regions, cities, and economic zones (Belkhodja, Mohiuddin, and Karuranga Citation2017; Wong et al. Citation2020). Some provinces can be favored by foreign firms due to low labor costs and large market size (Boermans, Roelfsema, and Zhang Citation2011). In particular, according to a local statistical bulletin, Sichuan, the most populous province in western China, has grown into a new FDI destination for U.S. multinationals in China. The provincial capital, Chengdu, also a central city of southwest China, received intensive U.S. investments of more than $1 billion per year between 2016 and 2019. Foreign enterprises usually undertake investment projects to ensure an easy domestic supply of natural resources needed as scarce factor inputs in manufacturing activities (L. Luo et al. Citation2008). FDI inflow might show a dependence with the existing capital stock of a region, as the capital stock can reduce the risk and cost for subsequent investments (Zheng Citation2011). As the neoclassical location theories highlight, a series of economic factors involving labor, resources, transportation, and market potential can affect the current FDI locations in various parts of China. Combined with location theories and the Chinese context, this work undertakes a rigorous analysis for the spatial distribution features of FDI inflows. It explores and assesses its linkage with unbalanced regional development, local economic factors, and geographic proximity.

Research Design

Spatial Data Survey and Plotting

FDI plays an important role in the economic development of host areas. It is widely valued by the government and has become a key item in the economic system of China. We choose the annual amount of foreign capital actually used as the indicator to measure of FDI inflows. The survey and accounting are carried out by statistical departments at all administrative levels in China with the cooperation of commercial departments. The conception of actual utilization is based on local perceptions of the positive effect of FDI. It is distinct from the contract capital and highlights the monetary amount received in the current period, according to the explanation of the National Bureau of Statistics of China. We collect the data from Chinese statistical yearbooks or bulletins and plot them on the map. This reflects the annual FDI inflows of Chinese city-regions (prefectural areas and municipalities). The locations of FDI are often interrelated with the geographic or regional systems of host areas. It causes some spatial patterns such as clustering, dispersion, or visually random distributions. Moran’s I and Getis–Ord G statistics will be applied for the pattern analysis (Anselin Citation1996; Getis and Ord Citation2010). It will assess the autocorrelation of spatial data distribution, and judge the pattern—clustered, random, or dispersed—as well as high–low value clusters, based on significance statistics (Mitchell and Griffin Citation2021). Some sparsely populated areas in the far west are not included in this research. Also, data for Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan are not included as they are considered as a source of FDI to mainland China. Further, we employ hot spot analysis (Getis–Ord Gi*) to detect the high or low value clusters, and the Anselin local Moran’s I for some outliers of spatial distribution of FDI.

Spatial Economic Model and Regression

The ultimate goal of FDI is to obtain profits from the host country, whether it is for the establishment of factories, sales outlets, or service organizations. Multinationals tend to be attracted to areas with favorable economic conditions including a series of factors for production, market demand, and supporting infrastructures. At the regional level, factors of production include the physical, human, and financial resources that are necessary for the firm’s operation (Fainshmidt, Smith, and Judge Citation2016). Access to advanced factors of production, such as a high-tech base and skilled labor, enables firms to enhance their competitiveness and efficiency (Porter Citation1998; Elia and Santangelo Citation2017). Regions that have vibrant factor markets can enjoy locational advantages for FDI attraction, especially multinationals with efficiency- or strategic asset-seeking objectives (Cui et al. Citation2020). Regional demand conditions are central to the foreign market entry strategies for multinationals with market-seeking objectives (Rugman and Verbeke Citation1993; Rugman, Oh, and Lim Citation2012). Different sectoral attributes could lead to the different FDI motivations that market seeking is valued by service-oriented corporations, whereas cost reduction influences manufacturing more (Riedl Citation2010). Sharply distinguishing sectors or industries of FDI can be difficult and unrealistic, however, because they could involve multiple intersecting areas of the production and marketing systems. Multinational corporations and their subsidiaries could cover multiple subsectors, especially in the dual context of China as a production base as well as a consumer market. Some enterprises are also extensively engaged in reinvestment activities in addition to their main business. We do not intend to distinguish the industry attributes of multinationals and FDI, but the flow of foreign capital between areas in a general sense. It aims to explore its spatial interaction mechanism with local economic factors in the context of China. Of course, we consider possible effects of location factors on companies with different sectoral backgrounds. These will be incorporated into a unified analytical framework. It is summarized by the major paths of seeking production factors, seeking (consumer) market, and reducing costs.

To assess the relationship with FDI inflows, we select some typical regional economic indicators as variables. As shown in the , the amount of foreign capital actually utilized (in U.S. dollars) is employed to measure annual FDI inflow to each prefectural-level or municipality area of China. Market area entry and occupation are closely related to the realization of commodity trade. Market-seeking becomes a major motivation of FDI, given the continuous growth of the Chinese consumer economy. It influences the regional or spatial layout of business corporations as service and goods suppliers or intermediaries. We use total retail sales of consumer goods to measure the market size of regional consumption, and expect a positive correlation with FDI inflow. For industrial enterprises, stable and sufficient energy supply is often a key consideration. In addition to natural resource reserves, energy supply relies on good infrastructure and distribution networks. We select the total regional gas supply to represent the energy and resource endowment. Technical advantages can result in cost reduction, higher profits, and enhanced market competitiveness. The thirst for technological innovation is a motivation for transnational investment, which is regarded as a springboard for firms to fulfill that aim (Y. Luo and Tung Citation2018). The number of patent applications granted is selected to measure regional technology and innovation. Labor cost is always one of the main concerns of business operations. We use the regional indicator average wage of employed staff and workers to measure the labor cost of each area, and predict a negative interrelationship with local FDI flow (LFDI). Good transport conditions are favored by investors normally. We use the total freight traffic by modes of transport (highway, water, and civil aviation) to measure the transport convenience of each region. The agglomeration of firms might affect the attraction of investment locations. In search of local knowledge, foreign investors tend to colocate with common-background FDI firms (C. Wang, Clegg, and Kafouros Citation2009; Tan and Meyer Citation2011). We use the number of industrial enterprises above designated size with foreign funds as an indicator to measure the regional agglomeration degree of FDI firms.

Table 1 Definitions of variables and data sources

In addition to some economic factors, spatial dependence could be an external cause of local FDI inflows. The inflow of FDI in a certain place can be due to relevant investment projects in neighboring areas. Multinationals might be interested in entering somewhere adjacent to their existing locations for business expansion, and conduct a networking layout spatially. It can generate spatial spillovers and driving effects to local FDI inflows, based on the geographic proximity. Such interaction, however, might be subject to the constitutive features of regional systems. The characteristics of regional political and economic polarization or fragmentation can lead to the location bias of FDI. The concentration of socioeconomic resources will increase the investment attractiveness of central cities. Regional integration and coordinated development might facilitate more FDI flowing to peripheral areas. Things are different over the vast territory of China, however. Different development models of the coastal and inland regions make the economy of areas relatively balanced in the east spatially, but in the midwest the economy is highly concentrated. On a national scale, there are multiple mechanisms and possibilities for the contribution of spatial dependence to the location choice of FDI. Its overall significance remains to be assessed based on the geographic proximity of local areas nationwide. Therefore, we employ the spatial lag model (SLM) and combine it with the variable system for regression analysis. The SLM was developed to introduce a spatial lag term based on the traditional data model, thus involving spatial correlation (W. Zhang and Wang Citation2018). It can measure the spatial dependence and neighboring effects of dependent variables, and the effects of independent variables in a unified framework. The spatial weight matrix allows for the dependent variable observations in a single area i depending on the immediate area j (j ≠ i) of the cases. Based on the principle of geographic proximity, we use the Queen contiguity weight. The artificial setting of distance or bandwidth for spatial dependence might be hard and unsubstantiated for rationality. If spatial dependence acts, though, it will surely influence the variable of the adjacent areas first. The Queen contiguity is therefore selected to generate a spatial matrix. Its criterion for adjacency is shared boundaries or vertices. When the i and j areas are judged to be adjacent, the spatial weight value (Wij) is 1; otherwise, it is 0. Our study sample is cross-sectional data from 2018, made up of 328 geographic cells (city-regions), the same as the plotting scope. With a unified framework, we aim to assess the role of spatial dependence and various local economic factors in spatial FDI inflows. The model is specified as follows:

where the definition of variables is shown in . W represents the weighting matrix;

is the spatial autocorrelation coefficient, which reflects the value and direction of spatial correlation of dependent variables;

is the coefficient vector of independent variables; and

refers to the vector of residuals.

Results and Discussion

Spatial Distribution Pattern and Trends

Since joining the WTO in 2002, China has gradually formed an all-around, multilevel, and wide-ranging opening system. The development model of attracting investment has been highly valued and implemented in more regions. The advent of the era of FDI liberalization has inspired multinational corporations to go deep into China. They are actively expanding their commercial presence in the vast territory of mainland China. Differences in economic conditions across China make FDI inflows spatially unbalanced. Changes in regional economies cause FDI inflows to shift over time. This affects its spatial distribution pattern. Due to their economic strength and competitiveness, well-developed regions can get continuous attention from multinationals. Economic development and construction in some lagging regions also attract FDI, however. We quantitatively examine the spatial distribution patterns of FDI in the years of 2002, 2010, and 2018 to reveal the spatial distribution trend of annual FDI flows since China became involved in the international trade system.

The time frame of our research is selected according to the major changes in China's development and reforms in the past twenty years. China’s entry into the WTO at the beginning of this century has greatly driven its foreign trade, manufacturing capacity, and economic take-off. It has stimulated a wave of FDI to China. Entering the 2010s, China began large-scale infrastructure and residential construction, including the central government’s $4 trillion investment plan to stimulate economic growth in the era following the 2008 financial crisis. At the same time, China has witnessed the rapid growth of its urban population, and changes in its domestic supply and demand structure. A large amount of foreign capital has been invested in Chinese real estate and urbanization construction (He and Zhu Citation2010; He, Wang, and Cheng Citation2011), and more attention to the growing urban consumption demand (L. Zhang and Wei Citation2017; Zhong and Wei Citation2018). In recent years, China’s regulation and market access for FDI has been greatly liberalized. After trial implementation in some regions, the market access negative list system has been in official use nationwide from 2018. Many restrictions are abolished for foreign investment and business operations. It thus becomes a catalyst for a new round of FDI in China.

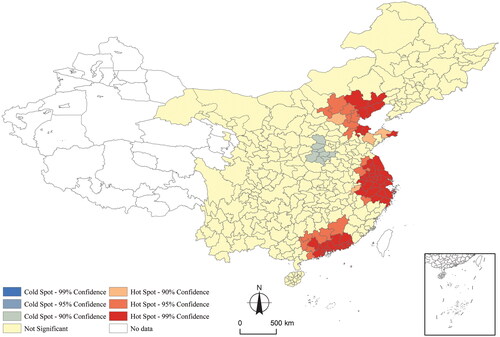

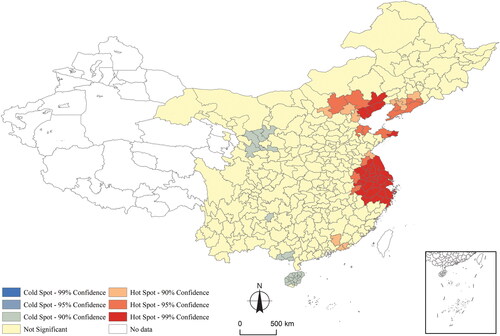

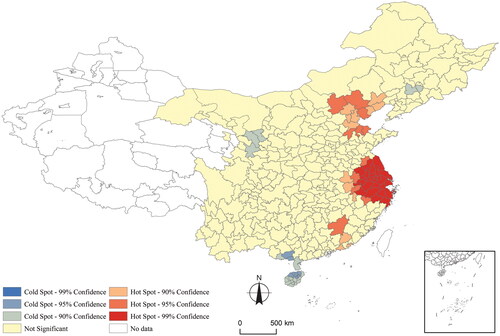

For quantitive assessment, the Moran’s I and Getis–Ord G statistics are used to evaluate the spatial pattern of annual FDI inflows in China. The Moran’s I statistic measures spatial autocorrelation based on both feature locations and feature values simultaneously. It calculates the Moran's I index value and both a z score and p value to evaluate the significance of that index. The general G statistic measures the concentration of high or low values for a given study area. It is a most appropriate tool when looking for unexpected spatial spikes of high values. The results of our calculation () show that for both indexes, the p value is statistically significant and the z score is positive. The Moran’s I tell us that spatial distribution of high values or low values in the data set is more spatially clustered than would be expected. The general G statistic further demonstrates the spatial clustering of high values. In the research years of 2002, 2010, and 2018, the Moran’s I index and its z score went through a continuous decline, as did the z score of Getis–Ord. It indicates the spatially sparse trend of LFDI value in China, especially for the period of 2010 through 2018 with a much sharper decline in the index values. This suggests that the location options for foreign investment in China are more spatially diversified, and more areas are favored by foreign capital.

Table 2 Results of Moran’s I and Getis–Ord global statistics

Spatial Clusters and Agglomeration Areas

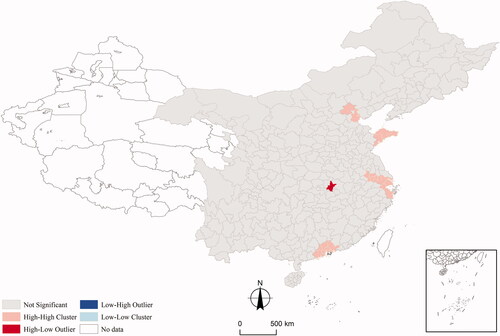

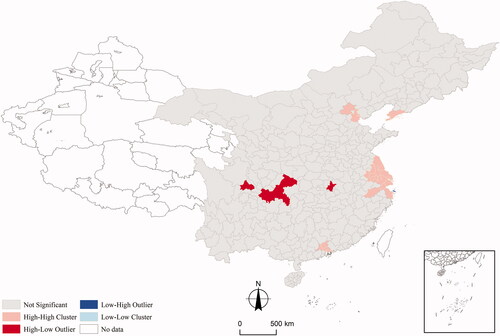

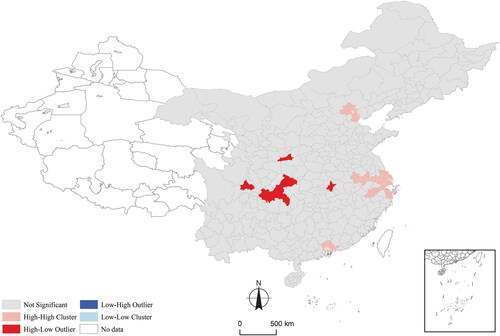

The Getis–Ord local statistic (z score) is applied for each feature in the data set spatially. It works by looking at each feature within the context of neighboring features. The results of z scores and p values can tell us where features with either high or low values cluster spatially. The analysis result is displayed on the input map (). Hot spots (in red), with statistical significance, mean that a feature has a high value and is surrounded by other features with relatively high values as well, forming the high-value cluster spatially. Cold spots (in blue), if they exist, represent the converse case. The maps show some hot spots in the coastal regions of China with high levels of FDI attractiveness. They are clustered in the Pearl River Delta, Yangtze River Delta, and Bohai Bay Rim, from the south to the north coastal region. With the passage of time, the concentration of hot spots in the Bohai Bay Rim and Pearl River Delta has declined, but there has been a trend of expansion in the Yangtze River Delta. Although FDI is still concentrated along the coast of China on a national scale, it is undeniable that it is spreading inland. There are also some cities in the inland areas that are favored by foreign investors, which cannot be underestimated. We use the Anselin local Moran’s I to judge the spatial cluster or outlier of LFDI on a local scale. The results () clearly revealed that some central cities (in bright red) in the middle or western areas of China are increasingly favored by FDI, besides coastal metropolitan areas like Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou.

Due to improving conditions for production and trade, the middle and western regions are increasingly receiving FDI inflows. This includes easy access to natural resources and labor and lower land rents. The western development strategy and the coastal–inland economic collaborative system have greatly changed the original backwardness of the midwestern region. The interregional fiscal transfer system enhances their financial strength. It promotes regional construction and economic growth in the inland areas. The Belt and Road Initiative has accelerated inland infrastructure construction as well. The new Eurasian Continental Bridge, represented by the China-Europe Railway Express, significantly improves the international transportation capacity of China’s inland regions. It makes western cities like Xi’an an international trade hub as well as an important inland port. Large-scale international and intergovernmental cooperation projects expand international trade routes in western China. The China-Singapore (Chongqing) Demonstration Initiative on Strategic Connectivity, covering all of southwest China, is in line with the development strategies of the Belt and Road, Western Development, and Yangtze River Economic Belts. A new corridor for international land–sea trade and business has been building at the regional level since the project’s implementation in 2015. Relying on this project, Chongqing is becoming a western growth pole with international influence. This has attracted many financial institutions and multinational organizations to set up branches. In midwestern China, economic development and construction are based on central or node cities. These inland cities have developed at an extremely fast pace in the past decade. Within the framework of a series of development strategies, planning, or policies, they enjoy the vast majority of economic and financial resources, thus giving them agglomeration power. Inland major cities have grown to be competitive, holding investment attractiveness that surpasses that of surrounding areas. Relevant research also found distance-adjusted FDI can generate cross-regional impacts, and the coastal FDI creates positive impacts on inland regions in China (Ouyang and Yao Citation2017). How much this is related to geographic proximity is still in question.

Spatial Effects of Economic Factors on FDI Inflows

The coefficient of the spatial lag term (W_FDI) is close to zero and not significant (). This shows that on a national scale, spatial dependence does not play a determining role in the location selection of FDI. FDI spreads from the eastern region to the middle and western regions, but this is not a spatial process in the order of geographic proximity. Spatial correlation and clustering features exist only in a few coastal areas. In the vast midwestern and inland areas, due to the high concentration of social and economic resources, central cities play an important role in settlement for multinational companies to deploy regional markets. It generates extreme FDI agglomeration on a local scale (large regions or provinces in the context of China). These centers of FDI in the midwestern region are far from the coast, spaced apart from each other, and also have little influence on adjacent places. Of course, foreign-funded enterprises and investment projects in different regions have organizational affiliations inextricably, but this is not necessarily geographic proximity, nor is it spatially dependent in nature. In China as a whole, the pure spatial linkage of FDI locations might not be as significant as it is in some other developing countries, such as Vietnam and Mexico (Esiyok and Ugur Citation2017; Fonseca and Llamosas-Rosas Citation2019). This is a result of China’s vast inland hinterland, unique regional development model, and polycentric compositions. The political and economic uniqueness of Chinese subregions and provinces will prompt multinational companies to adopt different regional layout strategies, which goes beyond the general sense of spatial proximity.

Table 3 Results of spatial autocorrelation regression

Energy supply and locale consumption are the most fundamental factors affecting the location of FDI, with the highest statistical significance of areas. This is relevant with the two basic motivations for current FDI in China, seeking the market and obtaining production convenience. Compared with the energy factor, technology or innovation plays a far less important role in location choice for FDI. This could be because most investment projects in China require greater energy access rather than technology-oriented resources. Foreign-funded firm agglomeration has a high coefficient strength with FDI inflows, but the statistical significance (probability) is the lowest compared with other variables. Places with lots of foreign-funded enterprises can usually attract more FDI afterward, but that is not inevitable. Somewhere that has been unengaged by multinationals before can still get receive subsequent FDI. This is also embodied in the diffusion trend of FDI spatial distribution. The gradual sparseness pattern implies emerging FDI will not only care about the hot spots of foreign firm clusters, but new market regions as well. Labor costs did not produce negative constraints on the location choice of FDI as expected. On the contrary, there is a significant positive relationship. This is related to the demand of foreign-funded enterprises for high-quality talents or highly skilled workers. In China, areas with higher wage levels tend to have a better labor market. It not only benefits the availability of labor in a larger geographical range, but provides more highly knowledgeable or skilled workers for corporations. Transportation becomes a less significant factor with limited effects on the FDI inflows. That could be due to the improved transportation conditions generally in China.

Conclusions

This work systematically investigated the spatial distribution and temporal changes of FDI inflows of Chinese city-regions on a national scale. The pattern of spatial FDI inflows still shows significant clustering features, but it has clearly shown a weakening trend over the past two decades. The Yangtze River Delta has grown into the largest agglomeration region of FDI in China spatially. A spatial diffusion of FDI proceeds from the coastal regions to the vast inland. The great regional development in midwestern China has brought a large amount of FDI to inland cities. The economic centralization, however, makes only several major cities able to get the benefits. This hinders the further spread of FDI to more areas in the midwestern region. The uniqueness of China’s local economy can lead multinational companies to have different considerations for regional layouts. This makes spatial dependence of FDI inflows based on geographic proximity insignificant across the country. Among local economic factors, energy supply, market consumption, and labor wages are significant variables. The requirement for high-quality workers makes wage level positively correlated with the local FDI inflows in China, which is not a pure cost factor for reduction. Thanks to the vigorous labor market, the much higher wage levels of some metropolises have not obstructed their FDI attraction. The spatial diffusion of FDI clusters from the eastern coastal region to the interior shows the trend of FDI convergence among regions. It was also mentioned by Huang and Wei (Citation2016), but our work can provide more details about spatial relations and interregional differences due to the application of geographic information systems and a spatial analysis approach. Market size has been highlighted by Huang and Wei (Citation2016) as well. Nonetheless, the energy supply for production still plays a key role in the location choice of FDI in China. It might be even more crucial against the current backdrop of global market volatility and tight energy supplies. This work supplements research findings on subnational distribution and location choice of FDI within China. It will deepen the knowledge base and help scholars or policymakers understand the regional differences and spatial patterns of FDI inflows in the Chinese context.

Acknowledgments

The author appreciates kind suggestions of the editor and two anonymous reviewers.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Qinchen Zhang

QINCHEN ZHANG is a PhD Student in the School of Natural and Built Environment at Queen’s University, Belfast BT7 1NN, Northern Ireland. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include Chinese economy, regional development, urbanization, and spatial inequality.

Literature Cited

- Alfalih, A. A., and T. B. Hadj. 2020. Foreign direct investment determinants in an oil abundant host country: Short and long-run approach for Saudi Arabia. Resources Policy 66:101616. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101616.

- Anselin, L. 1996. The Moran scatterplot as an ESDA tool to assess local instability in spatial association. In Spatial analytical perspectives on GIS, ed. M. Fischer, H. J. Scholten, and D. Unwin, 111–26. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bailey, N. 2018. Exploring the relationship between institutional factors and FDI attractiveness: A meta-analytic review. International Business Review 27 (1):139–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.05.012.

- Bhasin, N., and S. Garg. 2020. Impact of institutional environment on inward FDI: A case of select emerging market economies. Global Business Review 21 (5):1279–1301. doi: 10.1177/0972150919856989.

- Buckley, P. J. 2006. Stephen Hymer: Three phases, one approach? International Business Review 15 (2):140–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2005.03.008.

- Buckley, P. J. 2011. The theory of international business pre-Hymer. Journal of World Business 46 (1):61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2010.05.018.

- Belkhodja, O., M. Mohiuddin, and E. Karuranga. 2017. The determinants of FDI location choice in China: A discrete-choice analysis. Applied Economics 49 (13):1241–54. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2016.1153786.

- Boermans, M. A., H. Roelfsema, and Y. Zhang. 2011. Regional determinants of FDI in China: A factor-based approach. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies 9 (1):23–42. doi: 10.1080/14765284.2011.542884.

- Chen, C. 2018. The liberalisation of FDI policies and the impacts of FDI on China’s economic development. In China’s 40 years of reform and development, ed. R. Garnaut, L. Song, and C. Fang, 595–617. Canberra, Australia: ANU Press.

- Chen, Y. 2009. Agglomeration and location of foreign direct investment: The case of China. China Economic Review 20 (3):549–57. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2009.03.005.

- Cui, L., D. Fan, Y. Li, and Y. Choi. 2020. Regional competitiveness for attracting and retaining foreign direct investment: A configurational analysis of Chinese provinces. Regional Studies 54 (5):692–703. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2019.1636023.

- Dennis Wei, Y. H., Y. Lu, and W. Chen. 2009. Globalizing regional development in Sunan, China: Does Suzhou industrial park fit a neo-Marshallian district model? Regional Studies 43 (3):409–27. doi: 10.1080/00343400802662617.

- Dunning, J. 1988. The eclectic paradigm of international production: A restatement and some possible extensions. Journal of International Business Studies 19 (1):1–31. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490372.

- Dunning, J. H. 2001. The eclectic (OLI) paradigm of international production: Past, present and future. International Journal of the Economics of Business 8 (2):173–90. doi: 10.1080/13571510110051441.

- Dunning, J. H., and S. M. Lundan. 2008. Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Cheltenham, UK, and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

- Dunning, J., and R. Narula. 1996. Foreign direct investment and governments: Catalysts for economic restructuring. London and New York: Routledge.

- Elia, S., and G. D. Santangelo. 2017. The evolution of strategic asset-seeking acquisitions by emerging market multinationals. International Business Review 26 (5):855–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.02.004.

- Esiyok, B., and M. Ugur. 2017. A spatial regression approach to FDI in Vietnam: Province-level evidence. The Singapore Economic Review 62 (2):459–81. doi: 10.1142/S0217590815501155.

- Fainshmidt, S., A. Smith, and W. Q. Judge. 2016. National competitiveness and Porter’s diamond model: The role of MNE penetration and governance quality. Global Strategy Journal 6 (2):81–104. doi: 10.1002/gsj.1116.

- Fan, H., S. He, and Y. K. Kwan. 2019. Foreign direct investment and productivity spillovers: Is China different? Applied Economics Letters 26 (20):1675–82. doi: 10.1080/13504851.2019.1591591.

- Fonseca, F. J., and I. Llamosas-Rosas. 2019. Spatial linkages and third-region effects: Evidence from manufacturing FDI in Mexico. The Annals of Regional Science 62 (2):265–84. doi: 10.1007/s00168-019-00895-1.

- Getis, A., and J. K. Ord. 2010. The analysis of spatial association by use of distance statistics. In Perspectives on spatial data analysis, ed. L. Anselin and S. J. Rey, 127–45. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Hao, R., and Z. Wei. 2010. Fundamental causes of inland–coastal income inequality in post-reform China. The Annals of Regional Science 45 (1):181–206. doi: 10.1007/s00168-008-0281-4.

- He, C. 2002. Information costs, agglomeration economies and the location of foreign direct investment in China. Regional Studies 36 (9):1029–36. doi: 10.1080/0034340022000022530.

- He, C. 2003. Location of foreign manufacturers in China: Agglomeration economies and country of origin effects. Papers in Regional Science 82 (3):351–72. doi: 10.1007/s10110-003-0168-9.

- He, C., J. Wang, and S. Cheng. 2011. What attracts foreign direct investment in China’s real estate development? The Annals of Regional Science 46 (2):267–93. doi: 10.1007/s00168-009-0341-4.

- He, C., and Y. Zhu. 2010. Real estate FDI in Chinese cities: Local market conditions and regional institutions. Eurasian Geography and Economics 51 (3):360–84. doi: 10.2747/1539-7216.51.3.360.

- Hu, J. 2020. From SEZ to FTZ: An evolutionary change toward FDI in China. In Handbook of international investment law and policy, ed. J. Chaisse, L. Choukroune, and S. Jusoh, 2395–416. Singapore: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-5744-2_79-1.

- Hu, Y., K. Fisher-Vanden, and B. Su. 2020. Technological spillover through industrial and regional linkages: Firm-level evidence from China. Economic Modelling 89:523–45. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2019.11.018.

- Huang, H., and Y. D. Wei. 2016. Spatial inequality of foreign direct investment in China: Institutional change, agglomeration economies, and market access. Applied Geography 69:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.12.014.

- Jones, J., and C. Wren. 2016. Foreign direct investment and the regional economy. London and New York: Routledge.

- Kim, M., and D. Xin. 2021. Export spillover from foreign direct investment in China during pre-and post-WTO accession. Journal of Asian Economics 75:101337. doi: 10.1016/j.asieco.2021.101337.

- Li, G., and C. Fang. 2014. Analyzing the multi-mechanism of regional inequality in China. The Annals of Regional Science 52 (1):155–82. doi: 10.1007/s00168-013-0580-2.

- Liao, F. H., Y. D. Wei, and L. Huang. 2020. Regional inequality in transitional China. London and New York: Routledge.

- Luo, L., L. Brennan, C. Liu, and Y. Luo. 2008. Factors influencing FDI location choice in China’s inland areas. China & World Economy 16 (2):93–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-124X.2008.00109.x.

- Luo, Y., and R. L. Tung. 2018. A general theory of springboard MNEs. Journal of International Business Studies 49 (2):129–52. doi: 10.1057/s41267-017-0114-8.

- Mah, J. S. 2008. Foreign direct investment inflows and economic development: The case of Shenzhen special economic zone in China. The Journal of World Investment & Trade 9:319–31. doi: 10.1163/221190008X00098.

- Mitchell, A., and L. S. Griffin. 2021. The ESRI guide to GIS analysis, volume 2: Spatial measurements and statistics. 2nd ed. Redlands, CA: ESRI Press.

- Nguyen, C. P., C. Schinckus, T. D. Su, and F. Chong. 2018. Institutions, inward foreign direct investment, trade openness and credit level in emerging market economies. Review of Development Finance 8 (2):75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.rdf.2018.11.005.

- Ouyang, P., and S. Yao. 2017. Developing inland China: The role of coastal foreign direct investment and exports. The World Economy 40:2403–23. doi: 10.1111/twec.12527.

- Ozawa, T. 1992. Foreign direct investment and economic development. Transnational Corporations 1:27–54.

- Ozawa, T. 2007. Institutions, industrial upgrading, and economic performance in Japan: The flying-geese paradigm of catch-up growth. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

- Porter, M. E., ed. 1986. Competition in global industries. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Porter, M. E. 1998. The competitive advantage of nations. 2nd ed. New York: Free Press.

- Riedl, A. 2010. Location factors of FDI and the growing services economy: Evidence for transition countries. Economics of Transition 18 (4):741–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0351.2010.00391.x.

- Rugman, A. M., C. H. Oh, and D. S. Lim. 2012. The regional and global competitiveness of multinational firms. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40 (2):218–35. doi: 10.1007/s11747-011-0270-5.

- Rugman, A. M., and A. Verbeke. 1993. Foreign subsidiaries and multinational strategic management: An extension and correction of Porter’s single diamond framework. MIR: Management International Review 33:71–84.

- Schiller, D., M. J. Burger, and B. Karreman. 2015. The functional and sectoral division of labour between Hong Kong and the Pearl River Delta: From complementarities in production to competition in producer services? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 47 (1):188–208. doi: 10.1068/a140128p.

- Sun, H. 1998. Foreign investment and economic development in China: 1979–1996. London and New York: Routledge.

- Tan, D., and K. E. Meyer. 2011. Country-of-origin and industry FDI agglomeration of foreign investors in an emerging economy. Journal of International Business Studies 42 (4):504–20. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2011.4.

- Tao, Y., and Y. Yuan, eds. 2019. Annual report on the development of China’s special economic zones (2017): Blue book of China’s special economic zones. Singapore: Springer Nature.

- Tuan, C., and L. F. Ng. 2003. FDI facilitated by agglomeration economies: Evidence from manufacturing and services joint ventures in China. Journal of Asian Economics 13 (6):749–65. doi: 10.1016/S1049-0078(02)00183-5.

- Wako, H. A. 2021. Foreign direct investment in sub-Saharan Africa: Beyond its growth effect. Research in Globalization 3:100054. doi: 10.1016/j.resglo.2021.100054.

- Wang, C., J. Clegg, and M. Kafouros. 2009. Country-of-origin effects of foreign direct investment. Management International Review 49 (2):179–98. doi: 10.1007/s11575-008-0135-4.

- Wang, W., and Z. Lin. 2008. Investment in China: The role of Southeast Asian Chinese businessmen. In China in the world: Contemporary issues and perspectives, ed. K. K. Yeoh, 147–60. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Institute of China Studies, University of Malaya.

- Wong, D. W., H. F. Lee, S. X. Zhao, and Q. Pei. 2020. Region‐specific determinants of the foreign direct investment in China. Geographical Research 58 (2):126–40. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12398.

- Yeh, A. 2012. Hong Kong: The turning of the dragon head. In Planning Asian cities: Risks and resilience, ed. S. Hamnett and D. Forbes, 192–212. London and New York: Routledge.

- Yuan, Y., ed. 2021. The historical evolution and the future of Shenzhen-Hong Kong relations on economic development. In Studies on China’s special economic zones, volume 4, 199–207. Singapore: Springer.

- Zhang, L., and Y. D. Wei. 2015. Foreign hypermarket retailers in China: Spatial penetration, local embeddedness, and structural paradox. Geographical Review 105 (4):528–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1931-0846.2015.12090.x.

- Zhang, L., and Y. D. Wei. 2017. Spatial inequality and dynamics of foreign hypermarket retailers in China. Geographical Research 55 (4):395–411. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12235.

- Zhang, W., and M. Y. Wang. 2018. Spatial-temporal characteristics and determinants of land urbanization quality in China: Evidence from 285 prefecture-level cities. Sustainable Cities and Society 38:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2017.12.011.

- Zhao, S. X., R. C. Chan, and N. Y. M. Chan. 2012. Spatial polarization and dynamic pathways of foreign direct investment in China 1990–2009. Geoforum 43 (4):836–50. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.02.001.

- Zheng, P. 2011. The determinants of disparities in inward FDI flows to the three macro-regions of China. Post-Communist Economies 23 (2):257–70. doi: 10.1080/14631377.2011.570053.

- Zhong, Y., and Y. D. Wei. 2018. Economic transition, urban hierarchy, and service industry growth in China. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 109 (2):189–209. doi: 10.1111/tesg.12276.