Abstract

Recent feminist geographic scholarship has urged geographers to distance themselves from androcentric and Eurocentric approaches, and to open up the discipline to diverse perspectives. Whereas numerous studies have focused on diversifying and decolonizing geography through recruitment practices, mentoring, and knowledge production, only a few have analyzed how diversity translates into teaching practices, particularly in contexts where diversity is relatively well-established among staff. Based on a questionnaire survey among the teaching staff, a content analysis of course syllabi, and a quantitative analysis of the department’s employee data, this article explores to what extent diversity within the department leads to diversity in teaching practices. By developing a framework of spaces of diversity, we analyze three spaces that potentially enable practicing diversity in teaching: The department’s academic space promotes free choice of research and teaching topics and flexible working conditions; the department space enables individuals to engage in shaping geographical teaching; and the knowledge space promotes diversity as an ideal. We found, however, that practicing diversity in geography is challenged through traditional and neoliberal university structures and formal and perceived hierarchies. Moreover, there is a need for concrete diversity practices on individual and institutional levels to actively bring diverse perspectives into the classroom.

女权地理学的最新研究, 敦促地理学者远离以男性和欧洲为核心的方法, 接受不同的观点。许多研究都侧重通过招聘、指导和知识生产, 去实现地理学的多样化和去殖民化。只有少数研究分析了多样性如何转化为教学实践(尤其是在教职员工多样性相对稳定的情况下)。基于教师问卷调查、课程大纲内容分析以及对地理系员工数据的定量分析, 本文探讨了地理系的多样性在多大程度上导致教学实践的多样性。我们建立了一个多样性的空间框架, 分析了可能实现教学多样性的三个空间:“学术空间”促进对研究课题、课程题目和灵活工作条件的自由选择, “地理系空间”使个人能够参与地理教学的建设, “知识空间”促进理想的多样性。然而, 传统的和新自由主义的大学体系以及严格的等级制度, 是实现地理多样性的挑战。此外, 还需要在个人和体制层面采取切实的多样性实践, 积极地将不同观点带入课堂。

La reciente erudición geográfica feminista ha urgido a los geógrafos a distanciarse de los enfoques androcéntricos y eurocéntricos, y a abrir la disciplina a perspectivas diversas. En tanto que numerosos estudios se han enfocado a diversificar y descolonizar la geografía por medio de prácticas de reclutamiento, tutoría y producción de conocimiento, solo muy pocos han analizado cómo se traduce la diversidad en las prácticas de enseñanza, en particular en contextos donde la diversidad está relativamente bien establecida entre el personal. Basado en una encuesta por cuestionario entre el personal docente, en un análisis del contenido de los programas de los cursos y un análisis cuantitativo de los datos de los empleados del departamento, este artículo explora hasta qué punto la diversidad dentro del departamento conduce a la diversidad en las prácticas de la enseñanza. Desarrollando un marco de los espacios de la diversidad, analizamos tres espacios que potencialmente permiten practicar la diversidad en la enseñanza: El espacio académico del departamento promueve la libre elección de los tópicos de investigación y enseñanza, y las condiciones flexibles del trabajo; el espacio del departamento permite a los individuos asumir compromisos en la configuración de la enseñanza geográfica; y el espacio del conocimiento promueve la diversidad como un ideal. Sin embargo, encontramos que practicar la diversidad en geografía implica enfrentar los retos de las estructuras universitarias tradicionales y neoliberales y de las jerarquías formales y percibidas. Aún más, existe una necesidad de prácticas concretas sobre diversidad a niveles individuales e institucionales para llevar activamente las diversas perspectivas al salón de clase.

We understand diversity as the openness to include different perspectives in research and teaching (Maldonado-Torres Citation2011; Jazeel Citation2017). Diversity, ideally, “goes through the system” (Ahmed Citation2012, 29) and is, in addition to diverse representation, visible in knowledge production and institutional structures. Recent feminist studies on diversity in higher education in geography have called for enhancing diversity through staff recruitment, reflecting on curricula and teaching practices, mentoring of women and Black and ethnic minority students and early career researchers, and decolonizing geographical knowledge production more broadly (Daigle and Sundberg Citation2017). These studies have argued that departments (Solís et al. Citation2014) and faculties (Gordon et al. Citation2021) are critical spaces for promoting and implementing diversity. So far, though, only a few studies have asked how departments promote diversity in teaching, especially in contexts where diversity is supported by federal (Swissuniversities Citation2021) and university (University of Bern Citation2021a) action plans, and where diversity among staff is relatively well-established, as is the case at the Department of Geography in Bern.

In the context of geography departments in the German-speaking region (Bauriedl et al. Citation2016), the United States (Adams, Solís, and McKendry Citation2014; Kaplan and Mapes Citation2016), Canada (Nentwich Citation2010), and the United Kindom (Maddrell et al. Citation2016), the Institute of Geography in Bern (GIUBFootnote1) has a high level of gender equality among professorships, postdoctoral researchers, doctoral students, and undergraduate students (). Since 1996, the institute has held—thanks to a student initiative urging the appointment of a woman professor—the first professorship for social and cultural geography in the German-speaking region that explicitly focuses on (and as of recently, unofficially carries the name) feminist geography. Largely because of this professor’s dedication, the women professors who were subsequently appointed, and the department’s support, the GIUB has transformed in twenty years from a male-dominated department to one with equal representation of gender. These continuous efforts have recently been rewarded by the Prix Lux, the Equal Opportunities Prize of the University of Bern (University of Bern Citation2021b).

Table 1 Percentage of women per employment level

This progress in gender parity has been accompanied by a generational change: In the past ten years, nine of ten professors have retired and two new professorships were founded. Six of twelve professors are women and all new professors were at the beginning of their contract between thirty-five and forty years old. These changes relate to recent developments in geography departments in Western European countries more broadly (Al-Hindi Citation2000).

In addition, due to international and third-party-funded projects, the department employs a high proportion of foreign PhD candidates and postdoctoral researchers from Asia, Latin America, Africa, and North America in research. The diversity and internationalization among staff, however, has not yet reached the same level of those of other geography departments, for example in the United States (Adams, Solís, and McKendry Citation2014). Similar to other universities in the German-speaking countries (Germany, Austria, and some parts of Switzerland), institutional action plans and practices are still mostly focused on gender equality between women and men, rather than on nonbinary, gender queer, and other gender identities, or other social identities such as race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status.

Finally, alongside other geography departments in Europe, there has been a change from a holistic to a pluralistic theoretical approach (Schlottmann and Wintzer Citation2019), informed by critical geographies. Based on the department’s publications and the course catalog, the geography department researches with and teaches about a wide range of social constructivist and poststructuralist and decolonial approaches with regard to climate change, food security, mobility, social inequality, regional development, housing, living, politics, and reproduction. Thus, critical reflections on knowledge production and on a persistent Eurocentric appropriation of the world are a crucial part of the geographical training in Bern.

Having witnessed these developments both as doctoral students and as teaching staff at the GIUB for many years, we were curious to explore to what extent this progress in gender equality and diversity among the academic staff translates into diversity in teaching practices in the classroom. With this study, we aim to contribute to recent debates in feminist geographic research on diversifying geography (Adams, Solís, and McKendry Citation2014; Solís et al. Citation2014; Daigle and Sundberg Citation2017; Radcliffe Citation2017; Faria et al. Citation2019), and bring these studies into conversation with other feminist and broader scholarship on diversity in higher education (Ahmed Citation2006; Mirza Citation2014). We acknowledge that studying (and even conceptualizing) diversity is complex, and our aim is not to provide a detailed analysis of how diverse one geography department is. Instead, we focus here on diversity in teaching practices, and by doing so, we wish to generate debate on diversity practices at geography departments—and in the end, discuss some ways to enhance such practices.

Our analysis is based on a questionnaire survey conducted in August 2020, a content analysis of course syllabi in 2020, and a quantitative analysis of the department’s employee data. Starting with the assumption that teaching is part of a broader academic and institutional content (cf. Daigle and Sundberg Citation2017), we include in our analysis the broader academic, institutional, and structural conditions that shape researchers’ experiences with diversity more broadly, in addition to the respondents’ individual experiences.

Studying diverse teaching practices is important because geographical knowledge is transferred to schools, universities, and policymaking. Therefore, actors in different fields use geographical knowledge, which creates extensive potential for shaping social debates and prepares students for a global society (Bigatti et al. Citation2012). We assume that future geographers with diverse perspectives give voice to the diverse needs of actors and thus provide conditions to establish spaces of diversity in society more broadly (Dorling and Shaw Citation2002; Mitchell Citation2016).

We understand space as socially constructed by actions and their consequences (Massey Citation1994; Staeheli and Martin Citation2000) and thus, as the dimension of things being and existing at the same time: a space of simultaneity and multiplicity (Massey Citation2005), shaped by interactions and structures. From a feminist and social geographic perspective (Valentine Citation2001; Pain Citation2003; Staeheli and Lawson Citation2010), we ask this: To what extent does space—and the interactions and structures within it—provide possibilities to act, and to practice diversity in teaching? Following critical geographic scholarship, we view educational spaces such as universities and schools paramount for acknowledging “the complex geographies of everyday life in globalized space” (Helfenbein and Taylor Citation2009, 238) and focus on the institutional geographies and the sociospatial processes within them (Cook and Hemming Citation2011).

In this study, we develop a theoretical framework of “spaces of diversity” in teaching in geographical higher education. Our analysis revealed three potential spaces of diversity in teaching in geographical higher education but also, their barriers. Based on these findings, we argue that despite diversity among the staff and in theoretical approaches, spaces of diversity are not used to their full potential. This shows how transferring geographical knowledge from diverse perspectives in teaching to students (future professionals, teachers, and policymakers) remains a constant challenge for teaching in higher education in geography.

Diversity Research in Higher Education in Geography: State of Research

In the past twenty years, geographic studies on diversity in higher education have mapped the presence of women (Wastl-Walter Citation1985; Monk, Fortuijn, and Raleigh Citation2004; Adams, Solís, and McKendry Citation2014) and their personal experiences (Duplan Citation2019; Johnston-Anumonwo Citation2019) at geography departments as well as the ways feminist and gender perspectives have shaped geographic research more broadly (Bauriedl, Fleischmann, and Meyer-Hanschen Citation2001; Brinegar Citation2001; Johnson Citation2012). These studies have found that despite vast developments toward gender equality, a “culture of maleness” (in German, “Kultur der Männlichkeit”) still prevails in geography departments in many European countries (Döll and Wucherpfennig Citation2011; see also Maddrell et al. Citation2016) as well as in North America (Kaplan and Mapes Citation2016).

In addition to reflecting on women’s position in geography, scholars have explored the ways the discipline has historically excluded Black and Indigenous people and people of color. The very colonial roots of geography are connected to discovering “savage” and “new” places and people, and they have placed people of color as objects of research rather than as subjects (Faria et al. Citation2019; Wald et al. Citation2019). Scholars have drawn attention to geography’s Whiteness as a discipline more broadly (Mahtani Citation2006; Faria and Mollett Citation2020), which refers to norms, practices, and ideologies of Whiteness as a set of historical and cultural practices and a structural advantage and standpoint (Faria and Mollett Citation2016).

These scholars have urged geography departments and individual researchers to “lead difficult conversations” about teaching and curriculum planning, and critically view geography’s imperial histories and theorizing as well as to find ways to detach the production of geographical knowledge from the hegemony of the disciplinary infrastructure (Jazeel Citation2017). By doing so, scholars have urged geographers to decolonize knowledge production (Radcliffe Citation2017; Brönnimann and Wintzer Citation2019), to open reason “beyond Eurocentric and provincial horizons, as well as producing knowledge beyond strict disciplinary impositions” (Maldonado-Torres Citation2011, 10).

In this study, we first draw on this extensive feminist geographic scholarship analyzing diversity in higher education beyond representation based on gender, race, ethnicity, and other social identities. We agree with studies on diversity in higher education arguing that such a broader approach to diversity is critical to create a better learning environment, to prepare students for real-world experiences, to increase awareness and understanding for diverse perspectives, and to build up empathy (Gordon et al. Citation2021). Thus, instead of focusing on decolonizing knowledge, we seek to understand how diversity translates into teaching practices in the classroom. “Opening up the discipline” then involves diverse individuals and groups (Clark, Fasching-Varner, and Brimhall-Vargas Citation2012) in not only theorizing and decolonizing knowledge, but also in encouraging researchers to reflect on what kind of knowledge they bring into research, the classroom, and curriculum planning—and how this knowledge transforms teaching.

Second, our understanding of diversity is based on broader research on diversity in higher education arguing that diversity is regionally varied (Price Citation2015). As we discuss in this article, for example, language is an important factor for recruiting and consequently, for teaching staff in Switzerland and European countries more broadly. Beyond teaching, the language question is crucial in the German-speaking region concerning diversity where professorships in geography are still mostly awarded to German-speaking White men. For example, in Austria, until 2021, all chair holders in geography were from German-speaking countries (Ermann Citation2020) and all but three were male. The language question applies also beyond the German-speaking context and is linked to international trends in academia where, for example, people with certain languages, backgrounds, and origins hold positions on editorial boards and professorships more often than others (Garcia Ramon Citation2004; Kitchin Citation2005; Schurr, Müller, and Imhof Citation2020).

Third, besides considering regional differences, we share the assumption of these studies that diversity efforts should be informed by the context: the institution type, size, mission, and location (Solís and Miyares Citation2014; Price Citation2015). Enhancing diversity in practice means concrete structural measures (Ahmed Citation2012; Solís et al. Citation2014) and—important also for our study—small departments generally have fewer employees and fewer resources than larger departments to implement such measures. Before studying diversity, it is therefore important to ask these questions: What is diversity here? What is possible to enhance spaces of diversity here?

Finally, although our study focuses on a geography department in Switzerland, we see various similarities with other geography departments in other countries. We thus situate this study among broader efforts of feminist scholars to investigate diversity in geography, particularly at departmental level (Solís et al. Citation2014); to diversify geography (Monk, Fortuijn, and Raleigh Citation2004; Faria et al. Citation2019), and to continue shaping geography as a discipline (Valentine Citation2001; Lee et al. Citation2014).

Studying Diversity in Higher Education: Methods and Methodology

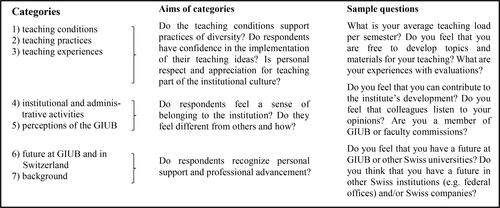

In human geography, practices are usually investigated through ethnographic methods, such as participant observation and interviewing (DeLyser et al. Citation2010) to understand decision-making and acting in social-spatial contexts (Hay Citation2016). In spring 2020, however, data collection was restricted due to COVID-19. Additionally, we as researchers are part of the GIUB staff and therefore, research principles such as neutrality and anonymity would have been compromised, situations of social desirability would have possibly emerged, and an overall bias with respect to the data material would have been expected (cf. Sin Citation2003; Vähäsantanen and Saarinen 2012; Roulston 2013). Last, but not least, the Web-based questionnaire in English enabled us to send the survey to all teaching staff (n = 50) at the GIUB in August 2020 (), with a response count of 38 participants. Therefore, we generated our data by using (1) a Web-based questionnaire survey, (2) a content analysis of the course syllabi, and (3) a quantitative analysis of the GIUB’s employee data.

Table 2 Sociodemographic data of the survey participants

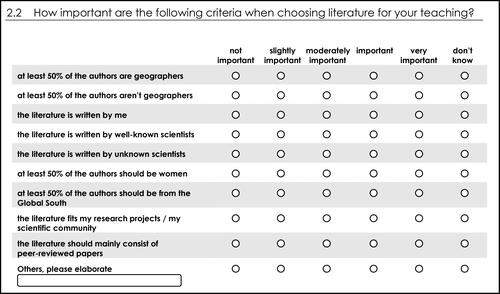

Developing questions for a questionnaire begins with a list of research topics researchers seek to investigate. McGuirk and O’Neill (Citation2016, 248) pointed out that a questionnaire is the consequence of translating research topics (e.g., diversity in teaching) into indicators (e.g., freedom of teaching) and indicators into questions (e.g., Do you feel that you are free to develop topics and materials for your teaching? When you teach, what are the three main criteria for your teaching?). In so doing we created an overview of “measuring” diversity at universities beyond quantitative data about gender, race, ethnicity, origin, and age (Schlemper and Monk Citation2011; Adams, Solís, and McKendry Citation2014; Price Citation2015). The questions aimed to capture how employees based on their diverse identities perceive opportunities and challenges to practice diversity in their work environment (Bennett Citation2001; Valentine Citation2005; Dowling, Lloyd, and Suchet-Pearson Citation2016; McGuirk and O’Neill Citation2016; ).Footnote2

Table 3 Guiding questions to develop the Web-based questionnaire

We posed closed questions, especially matrix questions using a Likert scale (Likert Citation1932). We are aware that matrix questions list all possible answers to a question that sensitize the participants to aspects that are less part of their own routine but are selected because of social desirability (Tourangeau, Singer, and Presser Citation2003; Mummendey and Grau Citation2014; McLafferty Citation2016). To counteract social desirability, the participants were obliged to choose the three most appropriate answers to each question. Most of the questions contained an open answer field.

We created a questionnaire with an approximate duration of twenty minutes consisting of seven questionnaire categories with twenty-two questions regarding teaching experiences and practices (, ). We analyzed the answers using content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005; Elo and Kyngäs Citation2008) according to our seven categories (). We focused on respondents’ perceptions, feelings, and activities that (implicitly or explicitly) referred to both diversity and lack of diversity in teaching experiences and practices.

After conducting the survey, we analyzed all course syllabi from 2020. The content analysis of the lecture syllabi provided insights into the topics, theories, and methods taught at GIUB as well as into the literature provided and recommended for the courses. Our context analysis focused on two questions: Do the topics, theories, and methods contain explicit or implicit references to diversity? Does the literature reflect or how much of the literature reflects an awareness of diversity in terms of gender, race, and origin of the authors? Next, we analyzed the department’s employee data. Due to data protection laws,Footnote3 however, the department could only provide an anonymous list of employees regarding gender. Hence, we retracted information on gender based on the persons’ names on the department’s Web site. It was not possible to gather an accurate list of the employees’ race, ethnicity, or origin, though, because this type of information is not collected by default.

Based on the content analysis of the survey and the course syllabi as well as the employee data, we identified three spaces of diversity and their barriers. We defined these three spaces as (1) the academic space, (2) the department space, and (3) the knowledge space.

Findings: Three Potential Spaces for Diversity and Their Barriers

Academic Space: Freedom of Research and Teaching vs. the Neoliberal and Traditional Academia

I can motivate students and include their interests and questions into my teaching.

I sometimes try out new teaching methods and styles.

I share the experiences with my research group and the other groups.

A large majority, 88 percent, feel they are free to develop their own teaching content and materials, which opens up possibilities for practicing diversity. Further, the general workload of the teaching staff is feasible, with one to three classes per week with a medium employment rate of 70 percent. Despite these flexible teaching conditions, particularly some postdocs and doctoral candidates felt pressured to prioritize research over teaching.

“Priority is research. Teaching is seen as a burden, rather than career advance,” stated one respondent when asked about experiences with teaching. Twenty percent teach due to personal interest, 21 percent consider teaching important for their career, and 18 percent teach to support their research group. These findings correspond to scholars’ experiences with pressure in the neoliberal university worldwide (Slaughter and Leslie Citation1999; Taylor and Lahad Citation2018), also dubbed a dilemma of “publish or perish.” “Teaching is seen,” then, refers to the prevailing expectations of the international academic space, rather than individuals or the department itself.

Preference for research was visible also in the respondents’ training in higher education: 30 percent of the respondents have a pedagogical education in teaching in higher education, and a few have taken individual courses but not the entire Certificate of Advanced Studies in Teaching in Higher Education (which is free of charge for all university employees). Seventy percent explained they would attend such training courses but perceived a lack of time to do so.

These responses reflect other studies that explain that neoliberal university policies result in increasing overall workload coupled with “an ever-competitive funding panorama” (Webster and Caretta Citation2019); temporary postdoctoral positions have become the norm and lectureship positions focusing on teaching are rare (Swiss Academy of Humanities and Social Sciences Citation2018). Early and advanced career researchers aim directly for professorships, which are few and still very traditionally organized. By traditional, we mean that at Swiss universities, as well as in Germany, Austria, and many other European countries, disciplines are predominantly divided into one-professor’s-research groups. This reflects a Humboldtian concept of the university: Professors are appointed as chair holders with elaborate gatekeeping processes leading to a big jump in prestige, authority, autonomy, and job security (cf. Enders Citation2001), but also to increased barriers for diversity concerning gender, race, and ethnicity because these few positions are still often awarded to White men (cf. Holmes et al. Citation2008). This leaves those untenured in between postdocs facing an uncertain job market (Caretta et al. Citation2018; Herschberg, Benschop, and van den Brink Citation2018).

The academic space is further shaped by language policies and practices. Switzerland is renowned for its multilingual state with four official languages. The official languages of the universities are regulated by the canton, which in Bern are German and French. With some exceptions, most undergraduate courses in Bern are taught in German, determining—understandably—that a key requirement for teaching is sufficient knowledge in German. This is also reflected in our survey participants: 88 percent of all respondents speak German as their first language. In spring 2021, 8 percent of undergraduate courses were taught in English and 92 percent in German. On the graduate level, however, 55 percent of all courses were taught in English and 45 percent in German. The language question is not only important in the Swiss context, but in numerous countries where departments, particularly since the Bologna reform, seek to balance internationalization with the social realities of the university’s location and language and to counteract the Anglicization of the local university culture (Erling and Hilgendorf Citation2006; Philipson Citation2006). Promoting non-Anglophone languages, particularly students’ first languages, is therefore crucial for maintaining social equality and diversity in academic research and teaching in a global context (Garcia Ramon Citation2004).

Hence, there are spaces of diversity, for example, to develop teaching content, to exchange teaching experiences with others, and to attend training courses. Further, the University of Bern is restructuring its career path models to offer diverse career perspectives to early career researchers in the future (Uni Link Citation2019). The responses, however, indicate that the aforementioned opportunities are not being used to their full potential due to the perceived and explicitly stated pressure to prioritize research and publish scientific papers (particularly for early career researchers) to follow academic career paths that are shaped by neoliberal university structures. Finally, the diversity among teaching staff is difficult to enhance due to the dilemma of languages and to maintain diversity within a global academic context.

Department Space: Individual Engagement vs. Formal and Perceived Hierarchies

The high degree of self-administration and the constant search for more deliberative and democratic decision-making processes offer me a good entry of becoming part of the evolution of GIUB.

Diversity is about a feeling of being included (Ahmed Citation2012), thus diverse department cultures are shaped by personal relationships. A sense of friendliness and welcome are important factors of a “daily place-sharing across difference” (Wise Citation2005, 172, cited in Price 2014). To understand such feelings of inclusion or exclusion, we asked participants how they would describe GIUB with three adjectives. The respondents viewed the department generally positively as “innovative and engaged,” “ambitious, polite,” “friendly and slow,” “friendly, welcoming, interdisciplinary,” and even “diverse,” but also “proud of its tradition.”

The respondents described their relationships with colleagues as constructive, supportive, emphatic, friendly, fruitful, pleasant, close, warm, respectful, and interested, among others. In our study, two thirds of respondents felt they could contribute to the department’s development and were listened to by their colleagues. One respondent noted, “We shape the program and the courses together.”

Hence, these personal relationships open up countless spaces to individually promote diversity. Some respondents, however, regretted that change was often difficult to achieve due to traditional structures. One participant argued that when suggesting changes, some referred to traditions and “the answer is often ‘it has always been like this.’”

The respondents often started their open-ended answers with “as a member of the lower midstaff” or “as a professor.” This reflects the way universities are generally organized and the ways responsibilities are divided between employees according to their position. One respondent said:

Yes, as a professor I am in a position where I can shape those [teaching and research culture]; I am in the process of developing my teaching in a direction I want it to go; I have full freedom to do research and a very good exchange with colleagues and support for new ideas”

These statements were interesting particularly because most respondents, from teaching assistants to professors, perceived their possibilities to contribute to the institute’s development similarly and thus, their employment status made little difference to the ways they perceived their possibilities to individually shape their teaching practices. One early career researcher stated:

Through the liberty in developing teaching materials and courses and the ways in which I teach I think I contribute to the institute’s teaching culture (defining alternative/new canons of relevant literature for example, addressing social and global inequalities in my teaching).

Some respondents, though, felt that formal hierarchies deterred their individual engagement when discussing broader institutional decisions beyond teaching. Hierarchies at the GIUB reflect typical academic structures at universities in the German-speaking region. The Gruppenuniversität (“group university”) was established as a democratic alternative to the Ordinarienuniversität (decision-making relies on full professors) at Western European universities from the 1950s onward (cf. Müller-Böhling Citation2000). Gruppenuniversitäten are organized according to four Stände (estates): students, lower midstaff (PhD, postdoc), upper midstaff (habilitated assistant professor, lecturers), and professors. Importantly, in all decision-making processes, students, lower midstaff, and upper midstaff are each represented by one representative, and all professors represent their departments individually, so that decision-making still rests with professors.

For example, one participant appreciated the many spaces of diversity, but was even more confounded about the hierarchies in broader decision-making processes:

At a department like the GIUB, where people do research about equality, participatory approaches, gender-related topics, etc, I don’t understand why actions and decisions are “top-down.”

This observation is common across universities worldwide and echoes studies on the persistent tension between structure and agency in educational spaces “through the influence of authority and control and individuals’ possibilities to resist prevailing expectations” (Cook and Hemming Citation2011, 2). Such observations reach also beyond departments to geographic journals that are led by critical geographers but often fall into traditional (White, Euro(anglo)centric) ideas regarding editorial board, authors, content, and language (Kitchin Citation2005): Critical and feminist approaches are well established as research perspectives to analyze societal phenomena including institutional structures, but still need to be internalized as possibilities to change structures within institutions.

Knowledge Space: Diversity as an Ideal vs. Need for Diversity Practices

I can bring my own experience and vision especially regarding interdisciplinarity, practical experience as well as a strong interest in questions of justice in sustainability.

Ninety percent of the respondents considered interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary knowledge important for their teaching. Although interdisciplinary research is not a guarantee for diversity, it could be informed and facilitated by efforts to promote multiculturalism and diversity (Maldonado-Torres Citation2011; cf. Reich and Reich Citation2006), as our study conducted at the GIUB indicates. Geography’s openness to other disciplines is visible and considerably high at the GIUB: Only 19 percent consider it important to include geographers in their literature and for 62 percent, the discipline is not important. Ninety percent considered teaching topics of their own group and GIUB curriculum relevant and 95 percent think that these topics reflect students’ interests. Hence, there is potential for including different perspectives.

Course literature is often considered an obstacle or opportunity for diversity (Mahtani Citation2004) and feminist scholars have advocated for considering race, ethnicity, gender, and origin and thus, decolonizing course curriculum (Noxolo Citation2017; Faria et al. Citation2019; Liboiron Citation2019), which is “more than including some indigenous writers on the reading schedule” (Liboiron Citation2019). In our study, 45 percent of the respondents reflected on social identities of the authors and 65 percent considered it moderately or very important to teach about social inequalities.

Simultaneously, academic disciplines and departments and their traditions determine what is viewed as knowledge and what sort of knowledge is possible and “[t]hey differ over what is interesting and what is valuable” (Bauer Citation1990, 106).Footnote4 Our study heavily reflected this idea: Almost half of the respondents considered it important to include well-known scientists in their literature and 75 percent considered the scientific community and their research projects important.

For example, in open responses, one participant explained they “prioritized the research content”:

The literature should cover the subject area at the appropriate level, length, and depth—this is extremely hard to find, so authorship was never a consideration so far.

In addition to reflecting on course literature, emphasizing different perspectives in teaching methods opens possibilities for enhancing diversity (Daigle and Sundberg Citation2017). Two thirds of the respondents considered interactive methods important and at the same time, 86 percent regarded traditional lectures as important. One respondent of the senior staff stated that individually, lecturers were able, and even encouraged, to apply different teaching methods, but there was a need for joint efforts to ensure diverse methods becoming part of the curriculum.

I wish we would implement much more [diverse methods] and follow up on discussions and decisions.

Thus, diversity is viewed as an ideal and partly practiced through interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary teaching content, which is also visible in the course bibliographies’ high amount of nongeographic literature and diverse teaching methods. Here, we see potential for enhancing diversity in terms of the knowledge we bring into classroom, particularly the authors’ social identities, which we believe would diversify the voices discussed in the courses, but also encourage both teaching staff and students to engage in broader questions around societal inequalities, discrimination, and diversity from different perspectives.

How Should Diversity in Teaching Look?

Our findings revealed that the diversity among department staff (particularly gender, age, and nationality) and among research and teaching topics offer a promising starting point for practicing diversity in teaching. The department’s flexible working conditions in teaching enable and even encourage a strong individual engagement for teaching. The high interest in interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research and exchange between research groups create spaces of diversity. Fully realizing diversity and transforming teaching practices into diverse teaching practices beyond representation based on gender, race, ethnicity, and other social identities, though, requires both concrete individual and institutional efforts. Otherwise, diversity remains an ideal.

This conclusion brings out the following questions, at GIUB but also in geography departments more broadly: How should a diverse department look, and how could diversity be practiced, particularly in our local context?

First, our findings call for changing neoliberal university structures (Mountz et al. Citation2015) as well as its traditional institutions. Instead of simply focusing on the negative aspects of “the neoliberal university,” however, we would like to think with a positive ontology: “one where acts and practices continually generate subjects in an endless stream of possibilities” (Kern et al. Citation2014, 836). According to our study, teaching is already a space where staff from doctoral students to professors have freedom in choosing their teaching content and methods. Thus, within neoliberal university structures, teaching could “be seen”—and practiced—as a space that enhances cocontribution of different knowledges. Rather than proposing to “add indigenous and stir,” we take inspiration from Liboiron (Citation2019), who suggested working with students and colleagues to teach, do research, and become citizens who do not perpetuate problematic historical or traditional patterns such as colonialism. We see interactive lectures (e.g., workshops, project-based learning), creative methods (e.g., film projects), and interdisciplinary knowledge production (which based on our research are well established at GIUB) as good departure points for such an “endless stream of possibilities.”

Second, for diversity to “go through the system” within the academic, department, and knowledge spaces, we need actions on both institutional and individual levels. At GIUB, we see potential in the Better Science initiative (betterscience.ch) initiated by some of the GIUB’s staff, which encourages us to think that breaking neoliberal, hierarchical, and traditional models of the university is possible. We believe that practicing better science includes reflecting on diversity measures on institutional levels (both faculty and departments); for example, seeking ways to benefit from the international staff in teaching, including diversity practices into existing committees such as the study committee, and making concrete suggestions for diversity practices in the classroom. Such practices include pushing teaching staff to consider gender, race, ethnicity, origin, and other social identities in course literature, and to reflect, for example, on how colonialism is embedded in local contexts (Purtschert, Lüthi, and Falk Citation2013; dos Santos Pinto et al. Citation2022), and providing spaces to sensitize staff for such practices. Simultaneously, we encourage individuals to find support for enhancing diversity in teaching and beyond through more informal settings such as friendships in academy (Webster and Boyd Citation2019; Metcalfe and Blanco Citation2021), and through feminist praxis and everyday practices (Smyth, Linz, and Hudson Citation2020).

Third, we encourage all geographers in teaching to be bold and to think beyond traditional norms and the “ways it has always been.” Diversity becomes possible when lecturers become aware of the daily and scientific borders impeding diversity such as routines instead of reflective and conscious choice of literature and theories. Decolonizing geography in regard to human resources is a crucial and a long process because of the sociodemographic constellation of students and teaching staff. But we could ask these questions: How is diversity visible in our lives, in our teaching, and in our department, in our local context, today? What can we, individually, do to enhance diversity? In this way, we may come to recognize that we are far from conveying diverse standpoints and diverse realities.

Thus, critical geography remains an adjunct in contrast to mainstream approaches and cannot establish itself as a norm of geographical thought und practice without explicit efforts to enhance spaces of diversity. In line with critical and feminist geographers, we therefore stress that there are geographies being created elsewhere that we need to engage with (Kitchin Citation2005; Maldonado-Torres Citation2011; Sundberg Citation2014). We would like to urge geographers to explicitly engage with these diverse geographies in the classroom to establish spaces of diversity in the department, which, in the long term, will help create such spaces in the society more broadly.

Acknowledgments

We would first of all like to thank our colleagues who shared their experiences with us. We are especially grateful to Doris Wastl-Walter, Heike Mayer, and Elisabeth Militz, whose insights on earlier versions of this article helped develop our argument, and reflect on the questions from different viewpoints. Thank you also to the Institute Board at GIUB for their openness, and for discussing and acknowledging the value of this study. Thanks also to the editor and reviewers for their thought-provoking and constructive comments.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Maaret Jokela-Pansini

MAARET JOKELA-PANSINI is a Swiss National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of Geography and the Environment at the University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3QY, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. She is interested in participatory methods and people’s embodied experiences with (ill) health, environmental pollution, and marginalization, as well as in the ways that questions of social inequality and diversity are promoted in academic spaces.

Jeannine Wintzer

JEANNINE WINTZER is a Lecturer for Qualitative Methods in the Department of Geography at the University of Bern, Bern 3012, Switzerland. E-mail: [email protected]. She works on the history, theories, and methods of geography, and is committed to reflecting on university teaching after the Bologna reform and COVID-19.

Notes

1 This abbreviation refers to the German designation: Geographisches Institut der Universität Bern.

2 Qualitative research principles call for open-ended questions above all because they have greater potential to enable the respondents to communicate their own experiences and practices (Silverman 2010). COVID-19, however, led to challenges such as home offices, additional workload through the care of entrusted persons, and time bottlenecks among many colleagues (Corbera et al. 2020).

3 To generalize our study in a wider national context, we sought to conduct a quantitative analysis of the employee data at GIUB as well as other geography departments in Switzerland, provided by the institutes on request. We asked all six geography departments in Switzerland (Geneva, Lausanne, Neuchatel, Zurich, Basel, Bern) to provide an overview of the nationality and gender of their employees. Only one department delivered the required data, however: In Switzerland, data protection generally prohibits sharing information about the origin, nationality, and even gender of individual departments’ employees. In most European countries, documenting citizens’ race and ethnicity is generally rare compared, for example, to North America (Burton, Nandi, and Platt Citation2010; Simon and Piché Citation2012; Simon Citation2017), mostly due to data protection regulations.

4 We complemented the questionnaire data by analyzing nineteen mandatory courses (2020) our students attend during the first six semesters of their undergraduate studies. The obligatory literature the respondents used (n = 68) consisted of forty-one men, twenty-one women (eighteen in human geography), and four a mix of both. Men generally referred to male authors in their courses (except for in two cases where women were coauthors), whereas all women cited at least one female author.

Literature Cited

- Adams, J. K., P. Solís, and J. McKendry. 2014. The landscape of diversity in U.S. higher education geography. The Professional Geographer 66 (2):183–94. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2012.735935.

- Ahmed, S. 2006. Doing diversity work in higher education in Australia. Educational Philosophy and Theory 38 (6):745–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-5812.2006.00228.x.

- Ahmed, S. 2012. On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Al-Hindi, K. F. 2000. Women in geography in the 21st century. Introductory remarks: Structure, agency, and women geographers in academia at the end of the long twentieth century. The Professional Geographer 52 (4):697–702. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2000.9628415.

- Bauer, H. H. 1990. Barriers against interdisciplinarity: Implications for studies of science, technology, and society (STS). Science, Technology, & Human Values 15 (1):105–19. doi: 10.1177/016224399001500110.

- Bauriedl, S., K. Fleischmann, and U. Meyer-Hanschen. 2001. Feministische Ansätze in physischer Geographie [Feminist approaches in physical geography]. In PerspektivenWechsel. Frauen- und Geschlechterforschung zu Mathematik und Naturwissenschaften, ed. H. Götschel and H. Daduna, 149–65. Mössingen: Talheimer Verlag.

- Bauriedl, S., N. Marquardt, P. Döll, P. Gans, I. Helbrecht, J. Miggelbrink, and B. Neuer. 2016. Auswertung der Studie “Geschlechterverhältnisse an geographischen Instituten deutscher Hochschulen und raumwissenschaftlichen For-schungsinstituten” und Handlungsempfehlungen der VGDH-Task Force [Evaluation of the study “Gender relations at geography departments in German” VGDH Task Force].

- Bennett, K. 2001. Interviews and focus groups. In Doing cultural geography, ed. P. Shurmer-Smith, 151–64. London: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781446219706.n14.

- Bigatti, S. M., G. S. Gibau, S. Boys, K. Grove, L. Ashburn, K. Khaja, and J. T. Springer. 2012. Faculty perceptions of multicultural teaching in a large urban university. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 12 (2):78–93.

- Brinegar, S. J. 2001. Female representation in the discipline of geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 25 (3):311–20. doi: 10.1080/03098260120084395.

- Brönnimann, S., and J. Wintzer. 2019. Climate data empathy. WIREs Climate Change 10 (2):e559. doi: 10.1002/wcc.559.

- Burton, J., A. Nandi, and L. Platt. 2010. Measuring ethnicity: Challenges and opportunities for survey research. Ethnic and Racial Studies 33 (8):1332–49.

- Caretta, M. A., D. Drozdzewski, J. C. Jokinen, and E. Falconer. 2018. “Who can play this game?” The lived experiences of doctoral candidates and early career women in the neoliberal university. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 42 (2):261–75. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2018.1434762.

- Clark, C., K. J. Fasching-Varner, and M. Brimhall-Vargas. 2012. Occupying the academy: Just how important is diversity work in higher education? Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Cook, V. A., and P. J. Hemming. 2011. Education spaces: Embodied dimensions and dynamics. Social & Cultural Geography 12 (1):1–8. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2011.542483.

- Daigle, M., and J. Sundberg. 2017. From where we stand: Unsettling geographical knowledges in the classroom. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42 (3):338–41. doi: 10.1111/tran.12201.

- DeLyser, D., S. Herbert, S. Aitken, M. Crang, and L. McDowell, eds. 2010. SAGE handbook of qualitative geography. London: Sage Publications.

- Döll, P., and C. Wucherpfennig. 2011. Studie zur Situation von Doktorand_innen und Post-Doktorand_innen am Fachbereich Geowissenschaften/Geographie der Goethe-Universität Frankfurt [A study on the situation of PhD students and postdocs in Geosciences/Geography at the Goethe University Frankfurt].

- Dorling, D., and M. Shaw. 2002. Geographies of the agenda: Public policy, the discipline and its (re)turns. Progress in Human Geography 26 (5):629–46. doi: 10.1191/0309132502ph390oa.

- dos Santos Pinto, J., P. Ohene-Nyako, M.-E. Pétrémont, A. Lavanchy, B. Lüthi, P. Purtschert, and D. Skenderovic. 2022. Un/doing race. Zürich, Switzerland: Seismo Press. https://www.seismoverlag.ch/en/daten/un-doing-race/.

- Dowling, R., K. Lloyd, and S. Suchet-Pearson. 2016. Qualitative methods 1. Progress in Human Geography 40 (5):679–86. doi: 10.1177/0309132515596880.

- Duplan, K. 2019. A feminist geographer in a strange land: Building bridges through informal mentoring in Switzerland. Gender, Place and Culture 26 (7–9):1271–79. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2018.1552249.

- Elo, S., and H. Kyngäs. 2008. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 62 (1):107–15.

- Enders, J. 2001. A chair system in transition: Appointments, promotions, and gate-keeping in German higher education. Higher Education 41 (1–2):3–25. doi: 10.1023/A:1026790026117.

- Erling, E. J., and S. K. Hilgendorf. 2006. Language policies in the context of German higher education. Language Policy 5 (3):267–93. doi: 10.1007/s10993-006-9026-3.

- Ermann, U. 2020. Editorial. Rundbrief Der Geographie, März(283), 1–3.

- Faria, C., B. Falola, J. Henderson, and R. Maria Torres. 2019. A long way to go: Collective paths to racial justice in geography. The Professional Geographer 71 (2):364–76. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2018.1547977.

- Faria, C., and S. Mollett. 2016. Critical feminist reflexivity and the politics of whiteness in the field. Gender, Place & Culture 23 (1):79–93. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2014.958065.

- Faria, C., and S. Mollett. 2020. “We didn’t have time to sit still and be scared”: A postcolonial feminist geographic reading of “An other geography.” Dialogues in Human Geography 10(1):23–29. doi: 10.1177/2043820619898895.

- Garcia Ramon, M. D. 2004. On diversity and difference in geography: A southern European perspective. European Urban and Regional Studies 11 (4):367–70. doi: 10.1177/0969776404046270.

- Gordon, S. R., M. Yough, E. A. Finney-Miller, S. Mathew, A. Haken-Hughes, and J. Ariati. 2021. Faculty perceptions of teaching diversity: Definitions, benefits, drawbacks, and barriers. Current Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01406-2.

- Hay, I. 2016. Qualitative research methods in human geography. Don Mills, Canada: Oxford University Press.

- Helfenbein, R. J., and L. H. Taylor. 2009. Critical geographies in/of education: Introduction. Educational Studies 45 (3):236–39. doi: 10.1080/00131940902910941.

- Herschberg, C., Y. Benschop, and M. van den Brink. 2018. Precarious postdocs: A comparative study on recruitment and selection of early-career researchers. Scandinavian Journal of Management 34 (4):303–10. doi: 10.1016/j.scaman.2018.10.001.

- Holmes, S. L. 2008. Narrated Voices of African American Women in Academe. Journal of Thought 43 (3–4):101–124. doi: 10.2307/jthought.43.3-4.101.

- Hsieh, H.-F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15 (9):1277–88. [Database] doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Jazeel, T. 2017. Mainstreaming geography’s decolonial imperative. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42 (3):334–37. doi: 10.1111/tran.12200.

- Johnson, L. C. 2012. Feminist geography 30 years on—They came. Geographical Research 50 (4):345–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-5871.2012.00785.x.

- Johnston-Anumonwo, I. 2019. Mentoring across difference: Success and struggle in an academic geography career. Gender, Place and Culture 26 (12):1683–1700. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2019.1681369.

- Kaplan, D. H., and J. E. Mapes. 2016. Where are the women? Accounting for discrepancies in female doctorates in U.S. geography. The Professional Geographer 68 (3):427–35. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2015.1102030.

- Kern, L., R. Hawkins, K. F. Al-Hindi, and P. Moss. 2014. A collective biography of joy in academic practice. Social & Cultural Geography 15 (7):834–51. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2014.929729.

- Kitchin, R. 2005. Disrupting and destabilizing Anglo-American and English-language hegemony in geography. Social & Cultural Geography 6 (1):1–15. doi: 10.1080/1464936052000335937.

- Lee, R., N. Castree, R. Kitchin, V. Lawson, A. Paasi, C. Philo, S. Radcliffe, S. M. Roberts, and C. Withers. 2014. The Sage handbook of human geography. London: Sage.

- Liboiron, M. 2019. Decolonizing your syllabus? You might have missed some steps. Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR). Accessed February 8, 2022. https://civiclaboratory.nl/2019/08/12/decolonizing-your-syllabus-you-might-have-missed-some-steps/.

- Likert, R. 1932. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology 22 (140):55.

- Maddrell, A., K. Strauss, N. J. Thomas, and S. Wyse. 2016. Mind the gap: Gender disparities still to be addressed in UK higher education geography. Area 48 (1):48–56. doi: 10.1111/area.12223.

- Mahtani, M. 2004. Mapping race and gender in the academy: The experiences of women of colour faculty and graduate students in Britain, the US and Canada. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 28 (1):91–99. doi: 10.1080/0309826042000198666.

- Mahtani, M. 2006. Challenging the ivory tower: Proposing anti-racist geographies within the academy. Gender, Place and Culture 13 (1):21–25. doi: 10.1080/09663690500530909.

- Maldonado-Torres, N. 2011. Thinking through the decolonial turn: Post-continental interventions in theory, philosophy, and critique—An introduction. Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 1 (2):1–15. doi: 10.5070/T412011805.

- Massey, D. 1994. Space, place and gender. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Massey, D. 2005. For space. Sage.

- McGuirk, P., and P. O’Neill. 2016. Using questionnaires in qualitative human geography. In Qualitative research methods in human geography, ed. I. Hay, 246–74. Don Mills, Canada: Oxford University Press.

- McLafferty, S. 2016. Conducting questionnaire surveys. In Key methods in geography, ed. M. C. Clifford, T. W. Gillespie, and S. French, 129–42. London: Sage.

- Metcalfe, A. S., and G. L. Blanco. 2021. “Love is calling”: Academic friendship and international research collaboration amid a global pandemic. Emotion, Space and Society 38:100763. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2021.100763.

- Mirza, H. 2014. Decolonizing higher education: Black feminism and the intersectionality of race and gender. Journal of Feminist Scholarship 7 (7):1–12. doi: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs/vol7/iss7/3.

- Mitchell, D. 2016. Geography teachers and curriculum making in “changing times.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 25 (2):121–33. doi: 10.1080/10382046.2016.1149338.

- Monk, J., J. D. Fortuijn, and C. Raleigh. 2004. The representation of women in academic geography: Contexts, climate and curricula. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 28 (1):83–90. doi: 10.1080/0309826042000198657.

- Mountz, A., A. Bonds, B. Mansfield, J. Loyd, J. Hyndman, M. Walton-Roberts, R. Basu, R. Whitson, R. Hawkins, T. Hamilton, et al. 2015. For slow scholarship: A feminist politics of resistance through collective action in the neoliberal university. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 14 (4):1235–59.

- Müller-Böhling, D. 2000. Die entfesselte hochschule [The unchained university]. Gütersloh, Germany: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Mummendey, H. D., and I. Grau. 2014. Die Fragebogen-Methode. Grundlage und anwendung in persönlichkeits-, einstellungs- und selbstkonzeptforschung [The questionnaire method. Basis and application in personality, attitudinal and self-concept research]. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

- Nentwich, F. 2010. Issues in Canadian geoscience: Women in the geosciences in Canada and the United States—A comparative study. Geoscience Canada 37 (3):127–34.

- Noxolo, P. 2017. Decolonial theory in a time of the re-colonisation of UK research. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42 (3):342–44. doi: 10.1111/tran.12202.

- Pain, R. 2003. Social geography: On action-orientated research. Progress in Human Geography 27 (5):649–57. doi: 10.1191/0309132503ph455pr.

- Philipson, R. 2006. English, a cuckoo in the European higher education nest of languages? European Journal of English Studies 10:13–32.

- Price, P. L. 2015. Race and ethnicity III. Progress in Human Geography 39 (4):497–506. doi: 10.1177/0309132514535877.

- Purtschert, P., B. Lüthi, and F. Falk. 2013. Postkoloniale Schweiz: Formen und Folgen eines Kolonialismus ohne Kolonien [Postcolonial Switzerland: Forms and consequences of a colonialism without colonies]. Bielelfeld, Germany: Transcript Verlag.

- Radcliffe, S. A. 2017. Decolonising geographical knowledges. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42 (3):329–33. doi: 10.1111/tran.12195.

- Reich, S. M., and J. A. Reich. 2006. Cultural competence in interdisciplinary collaborations: A method for respecting diversity in research partnerships. American Journal of Community Psychology 38 (1–2):51–62. doi: 10.1007/s10464-006-9064-1.

- Schlemper, B., and J. Monk. 2011. Discourses on “diversity”: Perspectives from graduate programs in geography in the United States. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 35 (1):23–46. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2010.499564.

- Schlottmann, A., and J. Wintzer. 2019. Weltbildwechsel: Ideengeschichte geographischen Denkens und Handelns. Bern: Haupt Verlag.

- Schurr, C., M. Müller, and N. Imhof. 2020. Who makes geographical knowledge? The gender of geography’s gatekeepers. The Professional Geographer 72 (3):317–31. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2020.1744169.

- Simon, P. 2017. The failure of the importation of ethno-racial statistics in Europe: Debates and controversies. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (13):326–32.

- Simon, P., and V. Piché. 2012. Accounting for ethnic and racial diversity: The challenge of enumeration. Ethnic and Racial Studies 35 (8):1357–65.

- Sin, C. H., 2003. Interviewing in ‘place’: The socio-spatial construction of interview data. Area 35 (3):305–12. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2010.499564.

- Slaughter, S., and L. L. Leslie. 1999. Academic capitalism: Politics, policies, and the entrepreneurial university. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

- Smyth, A., J. Linz, and L. Hudson. 2020. A feminist coven in the university. Gender, Place & Culture 27 (6):854–80. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2019.1681367.

- Solís, P., J. K. Adams, L. A. Duram, S. Hume, A. Kuslikis, V. Lawson, I. M. Miyares, D. A. Padgett, and A. Ramírez. 2014. Diverse experiences in diversity at the geography department scale. The Professional Geographer 66 (2):205–20. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2012.735940.

- Solís, P., and I. M. Miyares. 2014. Introduction: Rethinking practices for enhancing diversity in the discipline. The Professional Geographer 66 (2):169–72. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2012.735920.

- Staeheli, L. A., and V. A. Lawson. 2010. Feminism, praxis, and human geography. Geographical Analysis 27 (4):321–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-4632.1995.tb00914.x.

- Staeheli, L. A., and P. M. Martin. 2000. Spaces for feminism in geography. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 571 (1):135–50. doi: 10.1177/000271620057100110.

- Sundberg, J. 2014. Decolonizing posthumanist geographies. Cultural Geographies 21 (1):33–47. doi: 10.1177/1474474013486067.

- Swiss Academy of Humanities and Social Sciences. 2018. Next generation: für eine wirksame Nachwuchsförderung [Next generation: For an effective promotion of young researchers]. Swiss Academies Report 13 (1). Accessed May 15, 2020. https://www.sagw.ch/fileadmin/redaktion_sagw/dokumente/Publikationen/Berichte/Next_Generation_Deutsch.pdf

- Swissuniversities. 2021. P-7 Diversität, Inklusion und Chancengerechtigkeit in der Hochschulentwicklung (2021–2024) [Diversity, inclusion and equal opportunities in development of higher education]. Accessed March 3, 2021. https://www.swissuniversities.ch/en/themen/chancengleichheit-diversity/p-7-diversitaet-inklusion-und-chancengerechtigkeit.

- Taylor, Y., and K. Lahad. 2018. Feeling academic in the neoliberal university: Feminist flights, fights and failures. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tourangeau, R., E. Singer, and S. Presser. 2003. Context effects in attitude surveys. Sociological Methods & Research 31 (4):486–513. doi: 10.1177/0049124103251950.

- Uni Link. 2019. Neue Wege in der Uni-Laufbahn [New paths in university careers]. Uni Link, January:2–3.

- University of Bern. 2021a. Action plan: Equal opportunities. Accessed November 8, 2021. https://www.unibe.ch/university/portrait/self_image/equality/action_plan_equal_opportunities/index_eng.html.

- University of Bern. 2021b. Equal opportunities prize of the University of Bern. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://www.unibe.ch/university/portrait/self_image/equality/equality_at_the_university_of_bern/prix_lux/index_eng.html.

- Valentine, G. 2001. Social geographies. London and New York: Routledge.

- Valentine, G. 2005. Geography and ethics: Moral geographies? Ethical commitment in research and teaching. Progress in Human Geography 29 (4):483–87. doi: 10.1191/0309132505ph561pr.

- Wald, S. D., D. J. Vázquez, P. S. Ybarra, and S. J. Ray. 2019. Introduction: Why Latinx environmentalisms? In Latinx environmentalisms: Place, justice, and the decolonial. ed. S. D. Wald, D. J. Vázquez, P. Solis Ybarra, and S. J. Ray. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Wastl-Walter, D. 1985. Geographie --Eine wissenschaft für männer? Eine Reflexion über die Frau in der Arbeitswelt und über die Inhalte dieser Diszipline [Geography - A science for men? A reflection on women in the world of work and about the contents of this discipline]. Klagenfurter Geographische Schriften 6:157–64.

- Webster, N. A., and M. Boyd. 2019. Exploring the importance of inter-departmental women’s friendship in geography as resistance in the neoliberal academy. Geografiska Annaler, Series B: Human Geography 101 (1):44–55. doi: 10.1080/04353684.2018.1507612.

- Webster, N. A., and M. A. Caretta. 2019. Early-career women in geography: Practical pathways to advancement in the neoliberal university. Geografiska Annaler, Series B: Human Geography 101 (1):1–6. doi: 10.1080/04353684.2019.1571868.

- Wise, A. 2005. Hope and belonging in a multicultural suburb. Journal of Intercultural Studies 26 (1–2):171–86. doi: 10.1080/07256860500074383.