Abstract

Urban agriculture has gained prominence in enhancing food security and sustainability in cities globally. This research explores the dynamics of urban agriculture (UA), focusing specifically on home gardens, which are often overlooked despite their potential to contribute to sustainability in urban environments. UA involves the cultivation of crops and agricultural products within urban and periurban areas, ranging from small-scale gardens to larger individual urban farms. Its benefits span environmental, social, and economic dimensions. This research addresses a notable gap in the existing literature by highlighting the importance of sustainable practices within home gardens, particularly in low-income communities. By examining the role of civil society actors and innovative approaches employed by home gardeners, this study aims to inspire and provide insights to promote sustainable UA, even within constrained urban spaces. The significance of sustainable practices in home gardens is underscored by their potential to improve local food nutrition, reduce waste, and minimize the environmental impact of food transportation.

Urban agriculture (UA) is defined as “small areas (e.g., vacant plots, gardens, verges, balconies, containers) within the city for growing crops and raising small livestock or milk cows for own consumption or sale in neighbourhood markets” (FAO UN Citation2020, 5), and it can be a source of food and income for urban dwellers. This multifaceted form of agriculture can be observed in a range of practices, from home gardening and community gardening, often facilitated by churches and schools, to larger individually operated urban farms (Atlink and Hart Citation2023). The prevalence of UA is notable across numerous African cities, including but not limited to Nakura, Kenya (Willkomm, Follmann, and Dannenberg Citation2021), Bulawayo, Zimbabwe (Ziga and Karriem Citation2023), and Cape Town, South Africa (Philander and Karriem Citation2016).

UA has been extensively studied, focusing on its environmental, social, and economic dimensions. Notably, UA offers transportation cost reductions by cultivating produce closer to consumption points, thus shortening supply chains (Atlink and Hart Citation2023). Moreover, it helps mitigate runoff and soil erosion by absorbing excess water, ultimately enhancing air quality through carbon dioxide absorption and oxygen release (Tomatis et al. Citation2023). UA serves beyond material gains, with individuals benefiting from an array of social, spiritual, and environmental aspects (Sofo and Sofo Citation2020). Studies highlight nonfood and nonmarketable benefits that positively affect the urban environment. They also emphasize the economic advantage of food security and household savings through self-produced food. UA supports the urban poor by providing both economic opportunities and nutritional security (Willkomm, Follmann, and Dannenberg Citation2021). Therefore, UA is closely linked to the achievement of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as Goal 1 (No poverty), Goal 2 (Zero hunger), and Goal 11 (Sustainable cities and communities). Recognizing these multifaceted benefits underscores the need to promote UA sustainably (see Azunre et al. Citation2019; Ayoni et al. Citation2023, who arrived at similar conclusions).

A notable gap in this body of literature revolves around the effective practice of urban cultivation within limited spaces, specifically in the context of home gardens. Home gardening is the practice of cultivating flowers, fruits, vegetables, or ornamental plants on a small portion of land for personal use by the owner or tenants of a property (Galhena, Freed, and Maredia Citation2013). Typically situated around the household or within walking distance, home gardens constitute a mixed cropping system, encompassing vegetables, fruits, plantation crops, spices, herbs, and ornamental and medicinal plants, along with livestock. Serving as a supplementary source of food and income, home gardens contribute to a diversified and sustainable cultivation approach.

The majority of existing literature tends to emphasize community gardens and urban farms at the periurban zones, inadvertently overlooking the substantial potential of home gardens in contributing to sustainability within urban settings. Moreover, the research in South Africa has failed to highlight the environmental benefits of the practice (Kanosvamhira Citation2024b). This is a critical oversight given the prevalence of home gardens and their potential impact on the urban environment. The exploration of sustainable practices within home gardens in urban settings is vital for several reasons. Home gardens represent a vast yet underutilized potential for food production, waste reduction, and community resilience (Galhena, Freed, and Maredia Citation2013). They can play a pivotal role in achieving local food security, reducing the strain on external food sources, and minimizing the carbon footprint associated with food transportation. Furthermore, sustainable practices within home gardens can encompass organic farming, composting, water conservation, and efficient space utilization, ultimately promoting a more sustainable lifestyle (Al-Mayahi et al. Citation2019; Ayoni et al. Citation2023; Radigoana et al. 2023).

Highlighting and addressing this gap, this study contributes to the existing literature by delving into how home gardeners capacitated by civil society actors cultivate sustainably, particularly in the challenging physical environment of low-income communities in Cape Town, South Africa. The findings shed light on the innovative and resourceful approaches employed by home gardeners, highlighting their resilience in overcoming constraints and practicing sustainable UA. The findings also explore how water conservation techniques, waste management strategies, and cultivation methodologies are aligned with sustainable cultivation within the harsh environmental context of the study area. By uncovering and analyzing these approaches, I hope to inspire and provide insights for encouraging and promoting sustainable UA even in constrained and confined urban environments.

Key Debates on UA and Home Gardens in South Africa

Home gardens, present since prehistoric times, hold significance due to their proximity to homes, close ties to family activities, and diverse cultivation of crops and livestock (FAO UN Citation2021). Serving as a cornerstone for household security, they have played a vital role in providing sustenance, fuel, fiber, and materials, and establishing land ownership as societies transitioned from nomadic to settled lifestyles. Research on home gardens in South African townships has historically concentrated on their contribution to food production, echoing the wider connection between urban poverty and farming practices in developing nations (van Vuuren, Van Averbeke, and Slabbert Citation2020). The primary focus has been on the prospect of urban food production to boost income, curtail food costs, and enhance nutritional well-being. The significance of home gardens and UA in South Africa, particularly in advancing food security and alleviating poverty, has sparked substantial discourse (Webb Citation1998; Webb and Kasumba Citation2009). Central to this discussion is the pivotal inquiry into their capacity to propel socioeconomic development within urban settings.

Academic discourse on UA gained momentum in South Africa after 1992, emphasizing its viability as a livelihood option for the urban poor amidst growing urban populations and limited economic opportunities (Rogerson Citation1993; Rogerson and May Citation1995). Advocates stressed the need to harness the prospects of urban and periurban cultivation, even though they acknowledged its limitations in economic gains (Thornton and Nel Citation2007; Thornton Citation2008, Citation2009; Malan Citation2015). Conclusive evidence on its ability to alleviate poverty and ensure food security remains cautious (Tembo and Louw Citation2013, 229). Similarly, critics argued that UA’s benefits were modest, questioning its effectiveness as a poverty alleviation strategy (Webb and Kasumba Citation2009). Webb (Citation2011) emphasized the lack of empirical evidence supporting its promotion, suggesting a disconnect between discourse and actual practice. Studies like the one of Webb and Kasumba (Citation2009) in Ezebelini showed limited produce duration; minimal income contribution; negligible employment; and modest environmental, social, and psychological benefits. Advocates counter by emphasizing the need to enhance productivity for urban gardeners (Thornton Citation2008). They argue that UA augments household income (Rogerson Citation1993).

Scholars have also argued that only a small percentage of the urban poor engage in UA, challenging its pro-poor impact (Webb Citation2011; Crush, Hovorka, and Tevera Citation2011). This, however, does not refute the practice’s potential (Rogerson Citation2003). Instead, it prompts exploration into why the poorest might not participate (Rogerson Citation1993; Moller Citation2005). Quick income-generating alternatives like renting backyard shacks might be preferred (Rogerson Citation1993). Additionally, social grant systems could disincentive engagement in UA (Thornton Citation2008). Haysom, Crush, and Caesar (Citation2017) indicated that even with grants, food security might still be an issue due to prioritized household expenditures. Critics stress the need for realistic expectations rather than exaggerating outcomes (Ruysenaar Citation2013).

UA persists and expands in South Africa, despite skepticism (Rogerson Citation2011). The discourse highlights the need to consider benefits beyond economic incentives (Slater Citation2001; Olivier and Heinecken Citation2017). Studies underscore intangible gains that are challenging to quantify (Moller Citation2005). Slater (Citation2001) highlighted the social empowerment urban gardening provides, especially for impoverished women in Cape Town. Averbeke’s (Citation2007) research in Pretoria revealed urban farming’s modest financial contributions to household income and food security but emphasized its role in reducing social alienation and family breakdown stemming from urban poverty. In the Cape Flats, the social benefits of UA outweighed financial gains, reaffirming the need to appreciate nonmonetary advantages in assessing UA’s impact (Martin, Oudwater, and Meadows Citation2000; Kanosvamhira Citation2019).

In summary, despite limited economic gains, urban home gardens hold potential for enhancing socioeconomic and environmental benefits. The practice’s value extends beyond economics, warranting its adoption due to its capacity to contribute to the SDGs (Kanosvamhira Citation2024b). South Africa’s contentious UA landscape calls for ongoing research to inform policy decisions and create an enabling environment for its development.

Study Area

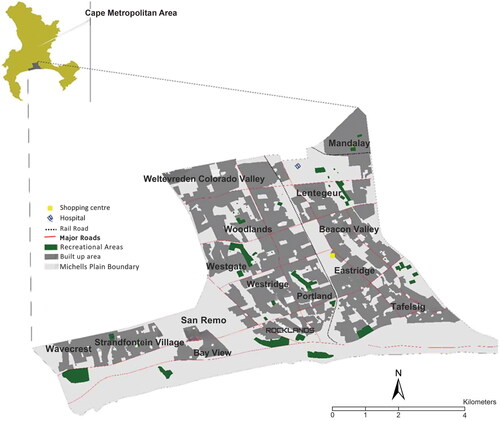

The Cape Flats, situated on the outskirts of Cape Town, encompass the eastern parts of the city’s northern and southern suburbs, which include Black and Colored townships. During the apartheid era, this area was earmarked as a relocation site for Black individuals due to the “White Only” areas declaration. Historically the Cape Flats have faced a significant lack of recreational and social amenities, as well as industrial and commercial centers (Karaan and Mohamed Citation1998). This deficiency highlights the vital role of UA within this region. One of its townships, Mitchells Plain, is a low- to middle-income area located on the southern edge of the Cape Flats, accommodating around 310,485 people (StatsSA 2013). Originating in the 1970s due to apartheid policies such as the Group Areas Act of 1950, it became a resettlement site for displaced Colored residents from places like District Six in Cape Town, exemplifying the lasting impact of apartheid spatial planning, which sought to segregate non-White populations to the city periphery (). Although UA might have a limited impact on the broader city’s food system, it remains essential for approximately 6,000 urban gardeners in the area. These individuals cultivate their own produce and sell the surplus within the Cape Flats, contributing to local sustenance and economic activity (Jagganath Citation2021).

Despite efforts aimed at supporting UA, the city of Cape Town struggled with an escalating water crisis, characterized by the most severe drought in decades (Reinders Citation2018). This posed a considerable threat, given that UA relies heavily on water availability. Efforts to mitigate this crisis involved supporting urban gardeners by providing essential infrastructure such as boreholes, tapping into the extensive underlying water reserves across the city. The sustainability of groundwater extraction is becoming an increasing concern, however, underscoring the necessity for more enduring solutions. Regulatory measures, including restrictions on borehole water usage for irrigation (City of Cape Town Citation2018), further exacerbate the challenges faced by home gardeners.

Water scarcity affected home gardeners, who are dependent on rain and tap water for their agricultural pursuits. The implementation of stringent water restrictions during the “Day Zero” campaign significantly compelled reductions or even discontinuation due to inadequate water supply (City of Cape Town Citation2017). Operating under Level 6B water restrictions, allowing a maximum of only eighty-seven liters of water per individual per day, any use of tap water for gardening was now subject to penalties. In response to this crisis, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) played a role in disseminating strategies to sustain gardening amidst these challenging conditions. The two main organizations working in the area are Soil for Life (see https://soilforlife.co.za) and the Schools Environmental Education and Development (SEED; see https://seed.org.za). Soil for Life is dedicated to educating individuals on creating sustainable food gardens that cultivate healthy, fertile soils, fostering optimal production of nutrient-rich crops in any available space. On the other hand, SEED is a distinguished nonprofit and public benefits organization based at Rocklands Primary School in Mitchells Plain on the Cape Flats, with a national reach through its schools-based outdoor learning program and youth applied permaculture training.

Materials and Methods

This research employed a mixed-methods research approach spanning from 2017 to 2018. The primary method of data collection involved conducting semistructured interviews with key stakeholders in UA, including home gardeners, civil society actors, and a government official.

The questionnaire used in the initial phase of the research was developed following extensive background research on sustainable cultivation methods and the attendance of UA workshops in Cape Town. The structured questionnaire aimed to gather information on various aspects of urban gardening, including practices, challenges, water conservation, and waste management. With permission from two major organizations working in the study area, the researcher randomly selected sixty urban gardeners, thirty from each NGO, using membership registers. The random selection process was automated using Microsoft Excel. A spreadsheet was created for each cohort, assigning urban gardeners a number. The 'RAND()' function generated random numbers for each gardener, and records were sorted accordingly. For instance, in a sampling frame of 200 urban gardeners, thirty were selected by sorting the first thirty randomly generated numbers. This procedure was replicated for the second sampling frame, resulting in a total sample size of sixty. Questionnaires were administered during weekdays at respondents’ homes or NGO sites, and the survey was complemented by observations.

Quantitative data, collected through questionnaires, underwent a thorough cleaning process to identify errors before being coded and entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The data were then exported to IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Version 25.0) for analysis. Descriptive statistics, including graphs and tabulations, were used to describe the basic features of the data. Subsequently, twenty participants were selected for semistructured interviews, coded by gender, gardening method, and age. The interviews lasted approximately forty minutes. The interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcriptions underwent careful study, coding, and content analysis based on dominant themes. Emerging themes were presented in prose to reflect each interviewee’s perspective on specific questions. Open-ended questionnaire responses were used to complement respective quantitative responses, often included as direct quotations. This comprehensive approach aimed to capture diverse perspectives within the UA ecosystem, ensuring a nuanced understanding of urban gardening practices.

Furthermore, interacting with civil society actors provided insights into the initiatives, campaigns, and strategies they deploy to promote sustainable UA practices. Additionally, conducting semistructured interviews with the Provincial Department of Agriculture extension officer allowed for a deeper understanding of the policy landscape, regulations, and potential areas for collaboration and improvement within the realm of UA. The triangulation of data gathered from these interviews contributed to more consolidated findings. This approach also yielded a more comprehensive understanding of the evolving dynamics and the progress made in promoting sustainable UA practices over time.

The research adhered to ethical principles over the course of the research. Prior informed consent was obtained, and all interviews were audio-recorded with explicit permission. Transcription of recordings followed strict verbatim procedures. The analysis involved careful consideration of ethical standards, ensuring confidentiality and anonymity for participants. Open-ended questionnaire responses were used ethically, respecting respondents’ perspectives.

Findings and Discussion

This section encapsulates the findings and subsequent discussion, organized into three primary themes: water conservation techniques, waste management strategies, and cultivation methods. Before delving into these themes, the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents and measures employed to accommodate gardening are presented for context and understanding ().

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

The gender breakdown in this study aligns with broader patterns in sub-Saharan Africa, where 58.3 percent of respondents were female, consistent with the region’s UA gender distribution (Maconachie, Binns, and Tengbe Citation2012). Similarly, studies in South African settings report a higher proportion of female respondents (Olivier and Heinecken Citation2017). Regarding age, the majority of respondents were elderly, with 38.8 percent being above sixty years old. According to the survey findings, 43 percent of respondents completed high school (matriculated), whereas only 13.3 percent pursued further education, including courses, certificates, diplomas, or degrees. Ten percent of respondents completed only primary school (from Grade 1–Grade 7), and 23.3 percent left school between Grades 8 and 12.Footnote1

Motivations for home gardening were diverse, with social benefits (41.0 percent) and health benefits (35.8 percent) being the primary drivers, emphasizing nonfinancial motivations for urban gardening (Battersby and Marshak Citation2013; Kanosvamhira Citation2023). When queried about the utilization of the harvested food, a substantial majority (81.7 percent) of respondents conveyed that the produce was exclusively used for household consumption. In contrast, a mere 1.7 percent specified that the produce was solely intended for selling, and 16.7 percent articulated that the primary objectives were self-consumption and generating cash. The cultivated food items encompassed a variety, including tomatoes, onions, carrots, and spinach, as well as assorted herbs like lemongrass and aloe.

On average, respondents have engaged in urban gardening in their backyards for 7.85 years, ranging from one to an impressive forty years. All gardeners received training from NGOs, a crucial factor ensuring skills were adapted to their operating soil conditions, with 80 percent of respondents having had some cultivation experience before training. For instance, Soil for Life, an NGO, empowers individuals through a twelve-week Home Food Gardening & Basic Health program, imparting sustainable gardening practices and providing essential resources like seeds, seedlings, compost, and mulch. This training equips gardeners to plan for future inputs without significant expenses. After training, gardeners benefit from six months of mentorship, home visits, and incentives. Hence, supporting organizations play crucial roles in equipping gardeners with the necessary skills and expertise to cultivate sustainably (Porter Citation2018). Despite challenges such as water scarcity, respondents demonstrated strong determination to continue gardening, highlighting the belief that intrinsic motivations outweigh modest material gains in UA (Maswikaneng et al. Citation2002).

The study indicates that home gardeners typically practice UA in confined spaces, averaging around 1.2 m2. To overcome space limitations, 70.0 percent of gardeners employ a combination of ground space and containers, with 18.3 percent specifically opting for containers (). Health concerns drive the preference for containers, particularly among elderly gardeners, as ground cultivation proves physically taxing. One elderly gardener expressed, “My body is becoming weaker, so I do not have strength; I feel at this present time I cannot dig into the ground anymore, so I must look into containers” (Female, over age sixty). Container cultivation is favored for its reduced physical strain, especially for elderly gardeners. Beyond addressing space constraints, the advantages of container gardening mentioned include fewer occurrences of weeds and pests, as well as overall tidiness. Civil society organizations have played a crucial role in promoting container gardening and providing discounts for the containers, facilitating cultivation in limited spaces.

The city of Cape Town at the time of the research was grappling with its worst drought in decades, posing a significant threat to UA due to its heavy reliance on water availability. Most of the home gardeners depend on rain and tap water for their home UA activities. With the introduction of water restrictions (City of Cape Town Citation2017) this meant that tap water could not be used for cultivation. For instance, the city was at the time operating at Level 6B water restrictions that allocate a maximum of eighty-seven liters of water per individual in a day. In fact, it is a punishable offense to use tap water for watering a garden during this period. Therefore, regular gardeners had been severely curtailed in maintaining their gardens. Survey results revealed that home gardeners were indeed grappling with the water crisis affecting the city. Despite these challenges, respondents who had received training from NGOs adopted various water conservation techniques to sustain their cultivation efforts under stringent conditions. Previous research indicates that households need to be provided with the skills, resources, and knowledge to be able to grow fruit and vegetables (e.g., soil improvement, space management) for food availability (Du Toit et al. Citation2022). For instance, one interviewee indicated, the “greatest challenge is the water challenge because luckily I have a JoJo tank, look I brought tanks and I have two and I do catch the gutter water and I know now, we had rains two or three weeks ago and I caught a lot of that rain so I am away again” (Female, forty to forty-nine years old). A prominent approach adopted by 90 percent of the respondents was the reuse of gray water for gardening (). Existing literature suggests that gray water reuse is a prevalent practice in South Africa (Carstens, Hay, and Van der Laan Citation2012) and other developing nations, often used as a coping strategy during periods of water scarcity (Radigoana et al. 2023). The use of gray water for food crops, however, was met with a level of suspicion from the other 5 percent of respondents who preferred to use other techniques such as watering at recommended times and mulching.

Table 2 Variables related to garden activities by the respondents

Initiatives like SEED and Soil for Life play a vital role by providing training and workshops, advocating for climate-smart gardening techniques, water recycling, and the cultivation of drought-resistant crops (Haysom, Crush, and Caesar Citation2017). Key informants representing civil society organizations highlighted that training was tailored to the region’s soil characteristics and water challenges, emphasizing crucial aspects such as enriching soil with compost and adopting mulching techniques to reduce evaporation and suppress weeds. Additionally, optimizing watering times, such as in the morning, was also highlighted as a valuable strategy to combat water scarcity. As one informant indicated, “They have learned so much, for example, how to make compost, a worm farm, how to plant when to plant, plant protection, there was a lot of stuff that they learned out of the workshops that they did and even with the designing your own place” (key informant, SEED).

The survey results shed light on the proactive approach of the gardeners toward kitchen waste management. A total of 100 percent of the respondents highlighted their conscientious practice of composting organic waste generated in their kitchens. This environmentally responsible behavior not only demonstrates their commitment to sustainable practices but also highlights their understanding of the benefits of composting. Crucially, a key informant substantiated this observation by confirming that these gardeners had indeed received training on effective composting techniques and the creation of trench beds. Particularly beneficial for those with adequate space and labor resources, these practices culminate in the development of fertile soils. These soils exhibit exceptional properties, including the capacity for optimal water absorption and efficient water storage. As a result, they offer a valuable advantage, allowing for the establishment of immediately usable planting beds even in areas characterized by shallow or poor-quality soils.

Moreover, the role of the city in advancing sustainable practices within the community cannot be understated. The provision of compost bins by the city marked a significant step toward encouraging responsible waste management and sustainable UA. It is noteworthy, however, that only 40 percent of the survey respondents reported receiving these compost bins from the local municipality. For those fortunate enough to have access to these compost bins, they proved to be invaluable assets for waste composting. The resulting compost was then thoughtfully integrated into their gardens following recommended procedures, thus contributing to the cultivation of healthier plants and a more sustainable urban environment ().

The final theme identified was the utilization of gardening techniques that prioritize environmental conservation and healthy food production. All the home gardeners (see ) identified during the research refrain from using synthetic chemicals and fertilizers in their cultivation practices. Instead, they emphasize environmental protection, opting to employ traditional cultivation methods that are gentle on the environment. The results from semistructured interviews indicate that this preference is not only driven by the perceived negative effects of synthetic fertilizers but also by the prohibitive costs associated with these chemicals. The literature indicates that this kind of cultivation offers multiple benefits to the physical environment and food harvested (see Winkler, Maier, and Lewandowski Citation2019). For instance, Hill (Citation2021) indicated that despite 60 percent of the respondents primarily relying on supermarkets, home gardens present a viable option for fresh and nutritious food options for residents in Detroit, Michigan. Research in Cape Town indicates that supermarkets located in low-income regions typically provide fewer healthy food choices compared to those found in wealthier neighborhoods (Kanosvamhira Citation2024a). Hence, healthier food sources from these gardens present an additional food source for individuals from these communities. Conversations with various supporting actors highlighted their role in educating and training home gardeners about environmentally friendly cultivation techniques, as well as healthier food options. These organizations typically offer courses at different levels, covering diverse aspects of cultivation such as composting, pest management, and water conservation techniques as well as healthy eating and food preparation.

Moreover, civil society actors not only provide training but also conduct regular monitoring of home gardeners to ensure the translation of taught principles into practice. They also offer additional guidance where necessary. Insights from the garden underscored that the chosen cultivation methods were consciously adopted, with a strong commitment to safeguarding the soil and the subsequent produce from their gardens. As a result, home gardeners have developed personalized techniques tailored to suit the unique needs of their gardens, ensuring a harmonious blend of sustainable practices and effective cultivation (Hill Citation2021).

Conclusion

Amidst rapid urbanization and escalating environmental challenges, sustainable UA, particularly in the realm of home gardens, has emerged as a pivotal force for ensuring food sustainability and enhancing community resilience. This research underscores the significance of sustainable practices within UA, emphasizing the often underestimated role of home gardens, especially in low-income communities of the Global South. UA, inclusive of home gardens, offers a comprehensive approach addressing not only environmental concerns but also social and economic dimensions. The research highlights the vital role of sustainable practices within home gardens, showcasing their potential to improve access to fresh vegetables and reduce organic waste. Civil society actors such as Soil for Life and SEED play a crucial role by equipping home gardeners with the knowledge and resources needed to thrive in challenging cultivating environments such as Cape Town. Investigating the innovative approaches employed by home gardeners, the research not only sheds light on current dynamics but also seeks to inspire and offer insights to propel sustainable UA, even within spatially limited urban settings found in township areas. The integration of sustainable practices is deemed crucial to address challenges like water scarcity and the physical limitations faced by elderly gardeners, with container gardening emerging as an essential technique for efficient space utilization and reduced physical strain.

Persistent challenges, notably the water crisis in regions like Cape Town, underscore the vulnerability of UA to environmental uncertainties. Despite the demonstrated resilience of home gardeners and the support from civil society organizations, the sustainability of urban agriculture faces barriers related to resource availability and societal perceptions. Initiatives from NGOs have proven instrumental in disseminating knowledge and strategies, yet financial constraints and cautious approaches toward water recycling and innovative gardening techniques remain hurdles.

In conclusion, unlocking the full potential of sustainable UA requires collaborative efforts. Policymakers, researchers, community organizations, and individual gardeners should come together to establish an environment conducive to sustainable UA. This entails furnishing essential resources, offering education, and developing appropriate policy frameworks. The transformative potential of UA is vast and should be harnessed with concerted efforts to build resilient, sustainable, and inclusive cities for a prosperous future. The research contributes to the literature by emphasizing the multifaceted dimensions of home gardening and urging collaborative action to overcome existing challenges. Future research could investigate additional sustainable techniques, like vertical farming, embraced by gardeners in low-income communities to further improve sustainability practices.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Note

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tinashe P. Kanosvamhira

TINASHE P. KANOSVAMHIRA is a honorary research fellow in the Department of Geography, Environmental Studies and Tourism, University of the Western Cape, Bellville 7535, South Africa. E-mail: [email protected]. His research primarily focuses on urban geography with a specific emphasis on sub-Saharan Africa. His diverse research interests encompass various socio-spatial issues, including sustainable infrastructures, governance, livelihood strategies of the less privileged, and food systems.

Notes

1 These percentages represent the educational attainment of respondents who provided answers to the survey question. The remaining percentage accounts for respondents who did not disclose their educational background.

Literature Cited

- Al-Mayahi, A., S. Al-Ismaily, T. Gibreel, A. Kacimov, and A. Al-Maktoumi. 2019. Home gardening in Muscat, Oman: Gardeners’ practices, perceptions and motivations. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 38:286–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2019.01.011.

- Atlink, H., and T. Hart. 2023. Feeding the community: Urban farming in Johannesburg. Human Sciences Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa.

- Averbeke, V. 2007. Urban farming in the informal settlements of Atteridgeville, Pretoria, South Africa. Water SA 33 (3):337–342.

- Ayoni, V. D N., N. N. Ramli, M. N. Shamsudin, and A. H. I. Abdul Hadi. 2023. Non-growers’ perspectives on home gardening: Exploring for future attraction. Journal of Regional and City Planning 34 (1):16–34. doi: 10.5614/jpwk.2023.34.1.2.

- Azunre, G. A., O. Amponsah, C. Peprah, S. A. Takyi, and I. Braimah. 2019. A review of the role of urban agriculture in the sustainable city discourse. Cities 93:104–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.04.006.

- Battersby, J., and M. Marshak. 2013. Growing communities: Integrating the social and economic benefits of urban agriculture in Cape Town. Urban Forum 24 (4):447–61. doi: 10.1007/s12132-013-9193-1.

- Carstens, G., R. Hay, and M. Van der Laan. 2012. Can home gardening significantly reduce food insecurity in South Africa during times of economic distress? South African Journal of Science 117 (9–10):Article 8730. doi: 10.17159/sajs.2021/8730.

- City of Cape Town. 2013. Food gardens policy in support of poverty alleviation and reduction. Policy No. 12399C. City of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

- City of Cape Town. 2017. Integrated development plan 2017–2022. City of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

- City of Cape Town. 2018. Level 6b water restrictions. http://resource.capetown.gov.za/documentcentre/Documents/Procedures,%20guidelines%20and%20regulations/Level%206B%20Water%20restriction%20guidelines-%20eng.pdf.

- Crush, J., A. Hovorka, and D. Tevera. 2011. Food security in Southern African cities: The place of urban agriculture. Progress in Development Studies 11 (4):285–305. doi: 10.1177/146499341001100402.

- Du Toit, M. J., O. Rendón, V. Cologna, S. S. Cilliers, and M. Dallimer. 2022. Why home gardens fail in enhancing food security and dietary diversity. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 10:804523. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2022.804523.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO UN). 2020. Urban and peri-urban agriculture. Rome: FAO.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (FAO UN). 2021. Urban food agenda. Rome: FAO.

- Galhena, D. H., R. Freed, and K. M. Maredia. 2013. Home gardens: A promising approach to enhance household food security and wellbeing. Agriculture & Food Security 2 (8):1–12. doi: 10.1186/2048-7010-2-8.

- Haysom, G., J. Crush, and M. Caesar. 2017. The urban food system of Cape Town, South Africa. Hungry Cities Report No. 3. Accessed August 10, 2017. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317348661.

- Hill, A. 2021. “Treat everybody right”: Examining foodways to improve food access. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 10 (3):1–8. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2021.103.012.

- Jagganath, G. 2021. The transforming city: Exploring the potential for smart cities and urban agriculture in Africa. The Oriental Anthropologist: A Bi-Annual International Journal of the Science of Man 22 (1):24–40. doi: 10.1177/0972558X211057162.

- Kanosvamhira, T. 2019. The organisation of urban agriculture in Cape Town, South Africa: A social capital perspective. Development Southern Africa 36 (3):283–94. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2018.1456910.

- Kanosvamhira, T. P. 2023. How do we get the community gardening? Grassroots perspectives from urban gardeners in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Cultural Geography 40 (1):47–63. doi: 10.1080/08873631.2023.2187509.

- Kanosvamhira, T. P. 2024a. Healthy food is hard to come by in Cape Town’s poorer areas: How community gardens can fix that. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/healthy-food-is-hard-to-come-by-in-cape-towns-poorer-areas-how-community-gardens-can-fix-that-215742.

- Kanosvamhira, T. P. 2024b. Urban agriculture and the sustainability nexus in South Africa: Past, current, and future trends. Urban Forum 35 (1):83–100. doi: 10.1007/s12132-023-09480-4.

- Karaan, M., and N. Mohamed. 1998. The performance and support of food gardens in some townships of the Cape metropolitan area: An evaluation of Abalimi Bezekhaya. Development Southern Africa 15 (1):67–83. doi: 10.1080/03768359808439996.

- Maconachie, R., T. Binns, and P. Tengbe. 2012. Urban farming associations, youth and food security in post-war Freetown, Sierra Leone. Cities 29 (3):192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2011.09.001.

- Malan, N. 2015. Urban farmers and urban agriculture in Johannesburg: Responding to the food resilience strategy. Agrekon 54 (2):51–75. doi: 10.1080/03031853.2015.1072997.

- Martin, A., N. Oudwater, and K. Meadows. 2000. Urban agriculture and the livelihoods of the poor in Southern Africa case studies from Cape Town and Pretoria, South Africa and Harare, Zimbabwe. Paper presented at the International Symposium “Urban Agriculture and Horticulture—The Linkage with Urban Planning,” Berlin, Germany, July 7–9, 2000.

- Maswikaneng, M. J., W. Van Averbeke, R. Böhringer, and E. Albertse. 2002. Extension domains among urban farmers in Atteridgeville (Pretoria, South Africa). Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education 9 (2):15–22. doi: 10.5191/jiaee.2002.09202.

- May, J., and C. M. Rogerson. 1995. Poverty and sustainable cities in South Africa: The role of urban cultivation. Habitat International 19 (2):165–81. doi: 10.1016/0197-3975(94)00064-9.

- Moller, V. 2005. Attitudes to food gardening from a generational perspective: A South African case study. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 3 (2):63–80.

- Olivier, D., and L. Heinecken. 2017. The personal and social benefits of urban agriculture experienced by cultivators on the Cape Flats. Development Southern Africa 34 (2):168–81. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2016.1259988.

- Philander, F., and A. Karriem. 2016. Assessment of urban agriculture as a livelihood strategy for household food security: An appraisal of urban gardens in Langa, Cape Town. International Journal of Arts & Sciences 6934 (9):327–38.

- Porter, C. M. 2018. What gardens grow: Outcomes from home and community gardens supported by community-based food justice organizations. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 8 (Suppl. 1):187–205. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2018.08A.002.

- Radingoana, M. P., T. Dube, and D. Mazvimavi. 2020. Progress in greywater reuse for home gardening: Opportunities, perceptions and challenges. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C 116:102853. doi: 10.1016/j.pce.2020.102853.

- Reinders, S. 2018. Water crisis grips Cape Town after South African drought stretching years. NBC News, January 29. https://www.nbcwashington.com/news/national-international/Cape-Town-Drought-Water-Crisis471659864.html?_osource=SocialFlowTwt_DCBrand.

- Rogerson, C. 1993. Urban agriculture in South Africa: Scope, issues and potential. GeoJournal 30 (1):21–28. doi: 10.1007/BF00807823.

- Rogerson, C. 2003. Towards “pro-poor” urban development in South Africa: The case of urban agriculture. Acta Academica :130–58. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC15129.

- Rogerson, C. M. 2011. Urban agriculture and public administration: Institutional context and local response in Gauteng. Urban Forum 22 (2):183–98. doi: 10.1007/s12132-011-9111-3.

- Rogerson, C., and J. May. 1995. Poverty and sustainable cities in South Africa: The role of urban cultivation. Habitat International 19 (2):165–81. doi: 10.1016/0197-3975(94)00064-9.

- Ruysenaar, S. 2013. Reconsidering the “Letsema principle” and the role of community gardens in food security: Evidence from Gauteng, South Africa. Urban Forum 24 (2):219–49. doi: 10.1007/s12132-012-9158-9.

- Slater, R. 2001. Urban agriculture, gender and empowerment: An alternative view. Development Southern Africa 18 (5):635–50. doi: 10.1080/03768350120097478.

- Sofo, A., and A. Sofo. 2020. Converting home spaces into food gardens at the time of Covid-19 quarantine: All the benefits of plants in this difficult and unprecedented period. Human Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Journal 48 (2):131–39. doi: 10.1007/s10745-020-00147-3.

- Tembo, R., and J. Louw. 2013. Conceptualising and implementing two community gardening projects on the cape flats, cape town. Development Southern Africa 30 (2):224–37. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2013.797220.

- Thornton, A. 2008. Beyond the metropolis: Small town case studies of urban and peri-urban agriculture in South Africa. Urban Forum 19 (3):243–62. doi: 10.1007/s12132-008-9036-7.

- Thornton, A. 2009. Pastures of plenty? Land rights and community-based agriculture in Peddie, a former homeland town in South Africa. Applied Geography 29 (1):12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2008.06.001.

- Thornton, A., and E. Nel. 2007. The significance of urban and peri-urban agriculture in Peddie, in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. Africanus 37 (1):13–20.

- Tomatis, F., Egerer, M., Correa-Guimaraes, A., and Navas-Gracia, L. M. 2023. Urban gardening in a changing climate: A review of effects, responses and adaptation capacities for cities. Agriculture 13 (2):502. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13020502.

- van Vuuren, M. J., W. B. Van Averbeke, and M. M. Slabbert. 2020. Urban home garden design in Ga-Rankuwa, City of Tshwane, South Africa. Acta Horticulturae 1279:117–24. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2020.1279.18.

- Webb, N. L. 1998. Urban agriculture environment, ecology and the urban poor. Urban Forum 9 (1):95–107. doi: 10.1007/BF03033131.

- Webb, N. 2011. When is enough enough? Advocacy, evidence and criticism in the field of urban agriculture in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 28 (2):195–208. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2011.570067.

- Webb, N., and H. Kasumba. 2009. Urban agriculture in Ezibeleni (Queenstown): Contributing to the empirical base in the Eastern Cape. Africanus 39:27–39.

- Willkomm, M., A. Follmann, and P. Dannenberg. 2021. Between replacement and intensification: Spatiotemporal dynamics of different land use types of urban and peri-urban agriculture under rapid urban growth in Nakuru, Kenya. The Professional Geographer 73 (2):186–99. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2020.1835500.

- Winkler, B., A. Maier, and I. Lewandowski. 2019. Urban gardening in Germany: Cultivating a sustainable lifestyle for the societal transition to a bioeconomy. Sustainability 11 (3):801. doi: 10.3390/su11030801.

- Ziga, M., and A. Karriem. 2023. Role of urban agriculture policy in promoting food security in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. In The Palgrave encyclopedia of urban and regional futures, 1462–68. Cham: Springer International Publishing.