Abstract

Objectives: The objective of this study was to investigate the risk factors of suicidal ideation and their population attributable fraction (PAF) in a representative sample of the elderly population in Korea. Method: We examined the data set from the Survey of Living Conditions and Welfare Needs of Korean Older Persons, which was conducted by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) in 2011. In that survey, 10,674 participants were randomly selected from those older than age 65. Simultaneous multivariate logistic regression was used to investigate the risk factors of suicidal ideation in terms of their sociodemographic and health-related variables. Subsequently, the PAF was calculated with adjustment for other risk factors. Results: The weighted prevalences of depression and suicidal ideation were 30.3% and 11.2%, respectively. In multivariate analysis, factors significantly associated with decreased risk of suicidal ideation included old-old age (odds ratio [OR] = 0.66 for 75 to 79 years, OR = 0.52 for 80 to 84 years, OR = 0.32 for older than 85 years), economic status (OR = 0.59 for 5th quintile; more than US$25,700 per year), whereas those associated with increased risk included poor social support (OR = 1.28), currently smoking (OR = 1.42), sleep problems (OR = 1.74), chronic illness (OR = 1.40), poor subjective health (OR = 1.56), functional impairment (OR = 1.45), and depression (OR = 4.36). Depression was associated with a fully adjusted PAF of 45.7%, followed by chronic illness (19.4%), poor subjective health status (18.9%), sleep problems (14.1%), functional impairment (4.9%), poor social support (4.2%), and currently smoking (3.6%). Conclusions: Preventive strategies focused particularly on depression might reduce the impact of suicidal ideation in the elderly population. Also, specific mental health centers focused on the specific needs of the elderly population should be established to manage suicidal risk.

Suicide is a tragic loss of human potentiality that causes considerable distress to families, carers, and health professionals. Unfortunately, the suicide rate in South Korea (hereafter Korea) is the highest among the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, and suicide rates in Korea have also continued to increase sharply during the past two decades (OECD, Citation2014). Suicide is now the fourth leading cause of death in Korea (Korea National Statistical Office [KNSO], Citation2014). Suicide rates increase with age (Shah, Citation2007), and the suicide rate among those older than age 65 is much higher than in other age groups. The suicide rate in individuals older than age 80 (123.3 per 100,000) is five times higher than that of individuals in their twenties (24.4 per 100,000) (Korean Association for Suicide Prevention, Citation2011). International statistics have indicated there is, on average, one suicide in the world among the elderly every 90 minutes (Amore, Baratta, Di Vittorio, Innamorati, & Lester, Citation2012). Suicide among the elderly has become a significant concern, and it is important to understand the factors associated with suicidal ideation among the elderly in order to promote their mental health.

In the past two decades, Korea has experienced a period of industrialization and globalization, with a rapid change from traditional and collective moral values, which the elderly hold dear, to a Western individualistic and materialistic culture. Within this rapid cultural change, Korean society has faced decreased social integration and increased social problems, including as drug use, crime, divorce, and unemployment (Park & Lester, Citation2006). The percentage of the population classified as older than age 65 in Korea was 11.3% in 2011. In addition, this proportion of elderly is expected to grow to the level of an “aged society (14% over 65)” when the population of elderly age 65 or older reaches 14.3% in 2018 and a “post-aged society (20% over 65)” at 20.8% in 2026 (KNSO, Citation2010). The aging of Korea is progressing rapidly compared to the United States, France, and other developed countries, as it is anticipated to take eight years to transition from an aged society to a post-aged society (KNSO, Citation2010). Rapid transition to a post-aged society will increasingly raise the demand for welfare needs, health care, and long-term medical expenses. Even combined with low birth rate, rapid aging is likely to change economic structure and lower economic growth. These rapid and unprepared changes in Korean society were proposed as possible explanations for the sharp increase in elderly suicide (Park & Lester, Citation2008).

Elderly individuals age 65 and older are known to be vulnerable to mental health problems (Lee, Citation2007). In previous Korean studies, the prevalence of depression among the elderly was reported to be 15.8% (Cho, Hahm, Jhoo, Bae, & Kwon, Citation1998), 13.4% (Kim, Shin, Yoon, & Stewart, Citation2002), and 27.8% (Park et al., Citation2012). Although not specifically related to the elderly, depression in general adversely affected the patients’ lives, including problems in interpersonal relationships, comorbid medical conditions and risks, worsening of cognition and mobility, and even increased mortality from suicide and from the interactions between depression and medical conditions (Reynolds, Citation2009). It has been clearly suggested that depression is the major predictor of suicidal ideation among older adults (Chopra et al., Citation2005). As a fair number of elderly people suffer from depression, a significant number of elderly are reporting suicidal ideation and, at the extreme end, some elderly individuals have actually died from suicide. Previous studies with community-dwelling elderly reported the prevalence of elderly suicidal ideation as 6% to 20% (Cheon, Lee, Roh, & Oh, Citation2005; Ono et al., Citation2001; Suh, Kim, Jung, Kim, & Cho, Citation1999; Yen et al., Citation2005; Yip et al., Citation2003).

Suicide risk evaluation in the elderly is particularly difficult to perform because they are more reluctant to directly express their intention to commit suicide than are younger adults (Conwell et al., Citation1998). Numerous research studies have identified the risk factors of elderly suicide. In addition, numerous community programs and organizations for suicide prevention have been established to manage suicide. Prevention of suicide, as in every medical field, is a crucial step, because prevention could alleviate the psychological suffering, disease burden, and medical cost associated with suicides. However, despite the wealth of knowledge provided by previous studies, our knowledge about how much these preventive interventions will affect the suicide rate is not fully known. An odds ratio (OR) or risk ratio is more meaningful to the clinicians who are managing the health of individual patients. However, if we are to advance our knowledge and our ability to prevent suicide, we should evaluate the efficiency of suicide prevention programs in a more scientific way. The efficiency of preventive interventions for suicidal ideation could be evaluated with respect to both the impact of the preventive intervention and the efforts needed to accomplish it (Reynolds et al., Citation2012). Impact is reflected in the proportion of suicidal ideation that would be prevented if the specific risk factor were thoroughly eliminated (population attributable fraction, or PAF). Effort is reflected by the number of persons who would need to be treated with prevention intervention to eliminate suicidal ideation (number needed to treat, or NNT). To achieve a high efficiency in preventive intervention, one should target risk factors with a high PAF coupled with a low NNT. In 1953, Levin initially proposed the concept of PAF to quantify the impact of smoking on lung cancer occurrence. PAF takes into account both the prevalence of the risk factor and its strength of association with the condition. Since then, PAF has been widely used to estimate the consequences of an association between a risk factor and a disease at the population level (Benichou, Citation2001). However, the concept of PAF has been underused in the literature relating to suicide, especially in the elderly population.

Suicide prevention strategies consist of universal, selective, and indicated prevention (Goldsmith, Pellmar, Kleinman, & Bunney, Citation2002). Universal strategies address an entire general population. Selective strategies address subsets from among the total population who have risk factors for suicide but who do not show any current signs. Indicated strategies address specific high-risk individuals who are showing early signs of suicide potential. Because suicidal ideation typically precedes suicide planning, which may result in an actual attempt, it provides an opportunity to intervene before a suicidal attempt and to improve outcome for such cases. Experts have contended that suicidal ideation should be a target of suicide prevention (Mann et al., Citation2005), and aggressive indicated interventions should be initiated when suicidal ideation is detected. There are indications that suicidal ideation is a predictor of suicidal attempts and completions (Mireault & De Man, Citation1996). The onset of suicidal ideation is associated with increased suicide attempts within a year of onset of suicidal ideation in general adult population (Kessler et al., 1999). Even in 20-year prospective study, suicidal ideation was a long-term risk factor for completed suicide in psychiatric outpatients (Brown et al., 2000). The guidelines for suicidal behaviors recommend screening for suicidal ideation and obtaining further information (i.e., the presence of a plan and intent) to evaluate the severity of risk (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2003). Therefore, understanding risk factors and their attributable fractions for suicidal ideation would have implications for the design of preventive interventions in the elderly and provide a promising approach to reducing suicide rates. Because a multitude of factors are associated with suicidal ideation in the elderly population, evidence-based preventive interventions would benefit from evidence analyzed from large community studies of elderly Koreans that investigate the relevant diverse demographic, health-related, and psychosocial variables to enhance the generalizability of the data. Thus, in this article, we aimed to investigate the risk factors of suicidal ideation and their attributable fraction by adapting the epidemiological concept of PAF in a large, representative elderly population.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This study examined the data set from the Survey of Living Conditions and Welfare Needs of Korean Older Persons, which was conducted by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) in 2011. The Survey of Living Conditions and Welfare Needs of Korean Older Persons is a government-approved statistical survey (Statistics Korea, Approval No. 11771) that has been conducted every three years since 2008 using representative samples of noninstitutionalized elderly people in Korea. The study sample was drawn from the 2005 census using a stratified, two-stage cluster sampling strategy, with census blocks as the primary sampling units (PSUs) and households as the secondary sampling units (SSUs). The household sampling procedure was conducted using primary and secondary stratifications at the district level, including primary stratification with seven metropolitan cities and nine provinces and secondary stratification using the streets, towns, and villages of the nine provinces. In total, there were 2,858 enumeration districts, 12,567 sample households, and 15,146 elderly samples. Details of the survey design are described elsewhere (Jung, Lee, Park, Lee, & Lee, Citation2012)

From August to November in 2011, a total 68 trained interviewers visited each selected household and conducted face-to-face interviews using a questionnaire that gathered information about sociodemographic variables and health-related variables, including chronic illness, subjective health status, functional impairment, cognitive impairment, depression, and suicidal ideation. There were no specific exclusion criteria other than age. All participants gave written informed consent. For 125 participants with severe physical or mental disabilities, key informants were also interviewed for this survey. The participants included 11,542 elderly individuals older than age 60 (response rate = 76.2%). In this study, we limited our analysis to the 10,997 elderly individuals older than age 65 who completed the survey. This study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Chonbuk National University Hospital, Jeonju, Korea.

Assessment

Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics

Participants provided information about their age (65 to 69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, 80 to 84, Over 85 years), gender (Male/Female), marital status [Married/Nonmarried (single, widowed, divorced)], educational status (No education/6 years or less/7 to 12 years/13 years or more), current employment status (Yes/No), economic status (1st quintile as annual income US$6,186 or less/2nd quintile as US$6,187 to US$9,672/3rd quintile as US$9,673 to US$14,990/4th quintile as 14,991 to US$25,699/5th quintile as US$25,700 or more), religion (Yes/No). Social support was categorized as None/1 to 2 persons/3 to 5 persons/More than 6 persons using responses to the following question: “How many close friends and close relatives do you have (people you feel at ease with and can talk to about what is on your mind)?” Information on body mass index (BMI) (Underweight [BMI < 18.5]/Normal [18.5 ≤ BMI < 25]/Overweight [BMI ≥ 25]), smoking status (Current smoker/Past smoker/Never smoker), alcohol use (Yes/No), sleep duration (Less than 6 hours/6 to 9 hours/More than 9 hours), and exercise (Yes/No) were gathered as health-related characteristics. For the analysis using the parsimonious model, we dichotomized social support (No/More than 1 person), BMI (Normal/Over- or underweight), smoking status (Current smoking No/Current smoking yes), and sleep duration (6 to 9 hours/Other).

Number of chronic illnesses was evaluated using responses to the following question: “Do you currently have [type of chronic illness] which has lasted for more than three months which was diagnosed by a physician?” The types of chronic illnesses included hypertension, stroke, hyperlipidemia, ischemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, arthritis, osteoporosis, back pain, chronic bronchitis, asthma, tuberculosis, eye disease, chronic otitis media, cancer, gastric ulcer, liver disease, and kidney disease. Because multimorbidity (co-occurrence of more than two chronic illnesses), which has an effect on disability, functioning, and quality of life, is a crucial problem in elderly (Marengoni et al., Citation2011), the number of chronic illnesses was categorized into two groups: 0 or 1/More than 2. The subjective health status was evaluated by asking participants the following: “How would you rate your health in general?” The choices for the subjective health status were classified as Very good, Good, Fair, Poor, and Very poor. For analysis, we dichotomize the subjective health status into two categories (Good, fair versus Poor): Good, fair included Very good, Good, and Fair; Poor included Poor and Very poor.

Functional Impairment and Cognitive Impairment

Functional status was measured using the Korean Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (K-IADL) assessment, which was validated by Won et al. (2002) in Korean. The activities are categorized into 10 IADL domains (personal grooming, doing housework, preparing meals, doing laundry, going out for short distance, using transportation, shopping, managing money, using a telephone, and taking medicine). Most items consist of three options—Fully independent (1), Partially dependent on others (2), Fully dependent on others (3)—but three items (Managing money, Using a telephone, and Taking medicine) consist of four options, from 1 to 4. The total score of K-IADL ranges from 10 to 33 and a lower score indicating a higher level of independence. Functional impairment was defined as a necessity for partial or complete personal help in at least one item (more than 11) of the K-IADL.

Cognitive impairment was evaluated by the Mini-Mental Status Examination—Korean Version (MMSE–KC), which was standardized into Korean by Lee et al. (Citation2002). The total score of the MMSE-KC ranges from 0 to 30. The subdomain of MMSE-KC is comprised of items assessing orientation to time and place, registration, attention and calculation, recall, naming, repetition, commands, and constructional ability. Cognitive impairment was defined as a z score of −1.5% or lower, which is at least 1.5 SD below the average score of Korean elders calculated by adjusting for age, gender, and education (Lee et al., Citation2004).

Depression and Suicidal Ideation

Depression was evaluated using the short version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (SGDS; Yesavage and Sheikh, 1986), a 15-item questionnaire that was validated by Bae and Cho (2004) in Korean. Each item consists of two options (Yes/No), with scores ranging from 0 to 1 and 5 items (item 1, 5, 7, 11, 13) were scored reversely. The total SGDS score ranges from 0 to 15, where high scores reflect more depressive symptoms during the past week. Participants who scored higher than 8 were defined as having depression; this score has been shown to have high sensitivity (0.943) and specificity (0.726) for depression based on a previous study of Cho et al. (1999). For evaluation of suicidal ideation, a specific question was asked about the occurrence of suicidal ideation (“Have you ever seriously thought about committing suicide after you reached sixty years of age?”) with response choices of Yes/No.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics (including the frequency and percentage) were used to describe sociodemographic and health-related characteristics among the participants. Comparisons of different groups (without suicidal ideation/with suicidal ideation) were made on sociodemographic and health-related characteristics using the t test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Weighted logistic regression was used to calculate unadjusted and adjusted ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To create a parsimonious model in the multivariate regression analysis, we dichotomized some risk factors as exposed including no social support, BMI (over- or underweight), currently smoking, sleep abnormality (sleep duration other than six to nine hours), chronic illness (more than two), and poor subjective health status, functional impairment, cognitive impairment, and depression as described under the assessment. Separate univariate logistic regressions were used to estimate the crude ORs of suicidal ideation by all independent variables investigated. Simultaneous multivariate logistic regressions were used to calculate the adjusted ORs of suicidal ideation by including all independent variables simultaneously into the regression model. To calculate a crude PAF, we used the traditional formula of Levin (Citation1953). However, because the PAF might be confounded and overestimated in the case of a lack of adjustment for other risk factors, Mortensen, Agerbo, Erikson, Qin, and Westergaard-Nielsen (Citation2000) and Goldney (Citation2004), in their studies of the PAF of suicide, stressed the importance of using adjusted PAF estimations. The adjusted PAF was calculated after adjustment for other risk factors from the multivariate logistic regression analysis. We used two different methods to estimate the adjusted PAF. First, we decided that the formula of Rockhill, Newman, and Weinberg (Citation1998) was more appropriate than that of Levin (Citation1953) because the use of adjusted OR estimates with the traditional Levin formula could result in bias, such as over- or underestimation of PAF (Darrow & Steenland, Citation2011). Second, we calculated adjusted PAF based on Greenland and Drescher (Citation1993), who adapted the punaf command in the STATA Version 14 statistical package (StataCorp, College Station, TX). The level of significance was set at 5%, and a two-tailed test was used.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic and Psychological Characteristics of the Subjects

A total of 10,674 subjects (unweighted n = 10,997), ranging in age from 65 to 100, participated in this study. The weighted mean age of the subjects was 73.65 years (SD = 6.18). The weighted prevalence of depression and suicidal ideation were 30.3% (unweighted n = 3,520) and 11.2 % (unweighted n = 1,208), respectively. The weighted mean score on the SGDS of the entire sample was 4.84 (SD = 4.77). provides the sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of study participants.

TABLE 1. Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics of Study Participants.

Risk Factors for Suicidal Ideation

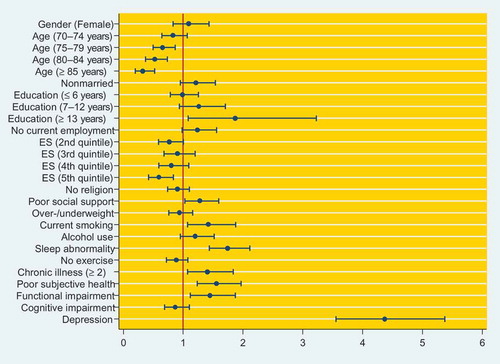

presents the crude and adjusted ORs for suicidal ideation by risk factor. There were a number of significant associations among the independent variables. The univariate regression analysis revealed that being female (OR = 1.27), being older than age 85 (OR = 0.63), being nonmarried (OR = 1.47), having less education (OR = 0.73 for 6 years or less; OR = 0.80 for 7 to 12 years), having no employment (OR = 1.72), having lower economic status (OR = 0.68, OR = 0.62, OR = 0.58, OR = 0.38 for 2nd to 4th quintile, respectively), having poor social support (OR = 1.70), currently smoking (OR = 1.28), having sleep problems (OR = 2.20), having a chronic illness (OR = 2.25), having poor subjective health (OR = 2.74), having functional impairment (OR = 2.18), and having depression (OR = 5.75) were significantly associated with suicidal ideation. We used multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine the adjusted OR of suicidal ideation for all of the measured factors listed in (all factors included simultaneously into the regression model). The results are illustrated in . Even after controlling for all confounding variables, old-old age groups (75 to 79 years, 80 to 84 years, and older than 85 years) significantly showed 0.32 to 0.66 times more suicidal ideation than age group of 60 to 64 years old; education of 13 or more years showed 1.87 times more suicidal ideation than no education; 5th quintile economic status showed 0.59 times more suicidal ideation than 1st quintile economic status; no social support showed 1.28 times more suicidal ideation than social support of more than 1; currently smoking showed 1.42 times more suicidal ideation than no smoking; sleep problems showed 1.74 times more suicidal ideation than sleep duration of six to nine hours; chronic illness of more than two showed 1.40 times more suicidal ideation than chronic illness of zero or one; poor subjective health status showed 1.56 times more suicidal ideation than good or fair subjective health status; functional impairment showed 1.45 times more suicidal ideation than no cognitive impairment; and depression showed 4.36 times more suicidal ideation than no depression.

TABLE 2. Risk Factors for Suicidal Ideation

FIGURE 1. The adjusted odds ratio of suicidal ideation according to various sociodemographic and health-related variables, functional impairment, cognitive impairment, and depression (total weighted n = 8,842). Notes. ES = economic status; The dots indicate the adjusted odds ratio presented in and the whiskers indicate the 95% CI. Reference category for each independent variable are gender (male), age (60–64 years), marital status (married), no education, current employment status (yes), economic status (1st quintile), has religion, social support (more than one person), normal BMI, not currently smoking, no alcohol use, sleep duration (6–9 hours), chronic illness (0–1), subjective health status (good, fair), no functional impairment, no cognitive impairment, and no depression. Information on their body mass index (BMI) includes underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal (18.5 ≤ BMI < 25), and overweight (BMI ≥ 25). Sleep abnormality indicates sleep duration less than six hours per day and more than nine hours per day.)

Population Attributable Fraction for Suicidal Ideation

The PAF for each risk factor was also investigated. The crude and adjusted PAFs of suicidal ideation associated with each risk factor are shown in . Depression was associated with a crude PAF of 60.5%, indicating that 60.5% of suicidal ideation could be prevented or reduced if depression was eliminated. A crude PAF for other risk factors were chronic illness (47.3%), poor subjective health status (44.8%), sleep problems (24.5%), functional impairment (13.6%), poor social support (11.4%), and currently smoking (3.3%). After adjustment of the confounding variables, we found a lowered adjusted PAF than the crude PAF calculated with the formula of Rockhill and colleagues (Citation1998) and Greenland and Drescher (Citation1993). Depression was associated with a fully adjusted PAF of 45.7%, followed by chronic illness (19.4%), poor subjective health status (18.9%), sleep problems (14.1%), functional impairment (4.9%), poor social support (4.2%), and currently smoking (3.6%).

TABLE 3. Population Attributable Fraction of Suicidal Ideation

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to investigate the risk factors and their attributable fractions of suicidal ideation in a large representative sample of elderly people in Korea. Although prior studies have demonstrated the association of many putative risk factors with suicidal ideation, our study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to identify the PAF for optimal risk factor levels to investigate the extent to which suicidal ideation could be reduced if each risk factor was prevented in elderly people. In addition, no studies have investigated PAF for major risk factors, along with depression, of suicidal ideation simultaneously in elderly people, such as chronic illness, poor subjective health status, and functional impairment. In multivariate regression analysis, the risk factor of suicidal ideation showing the highest OR was depression, followed by those with sleep problems, poor subjective health, functional impairment, chronic illness, currently smoking, and poor social support. However, to establish most efficient preventive intervention, it is important to consider the strength of the contribution and focus on the risk factors with high PAF, in other words, risk factors which have high ORs (even after adjustment of confounding variables) coupled with a high prevalence rather than low prevalence. The priority of contribution to suicidal ideation after considering adjusted PAF of each risk factor was somewhat different from that of adjusted OR. Depression was still the most important risk factor with the largest PAF (45.7%) for suicidal ideation, which means that 45.7% of suicidal ideation could be reduced if depression was prevented in elderly people. The PAF for chronic illness was 19.4%, followed by poor subjective health status (18.9%), sleep problems (14.1%), functional impairment (4.9%), poor social support (4.2%), and currently smoking (3.6%). Our result suggests that preventive intervention of suicidal ideation in the elderly might have great efficiency when focusing on depression, followed by other risk factors as the priority according to PAF.

Our result is consistent with previous studies that utilized PAF to examine the importance of depression in suicidal ideation in an adult population. Previous studies with general adult populations (Cheung, Law, Chan, Liu, & Yip, Citation2006; Goldney, Dal Grande, Fisher, & Wilson, Citation2003; Goldney, Wilson, Grande, Fisher, & McFarlane, Citation2000) have reported PAFs for depression as 46.9%, 56.6%, and 43%, and PAF for affective disorder as 38.8% (Pirkis, Burgess, & Dunt, Citation2000). With regard to PAF, depression, among various factors, contributed greatly to suicidal ideation. These results may suggest that if depression could be prevented or treated effectively, 38.8% to 56.6% of suicidal ideation could be eliminated. In a study of elderly people, Almeida et al. (Citation2012) reported that PAFs for depression and past depressive disorder were 8.8% and 23.6%, respectively. In our results, the weighted prevalence of elderly depression was 30.3%, which is comparable to the percentage found in a previous nationwide survey of elderly depression (27.8%) in Korea (Park et al., Citation2012). However, this prevalence is higher than that found in community studies of Western countries (13.5%, Beekman, Copeland, & Prince, Citation1999) and Asian countries (12.5–17.7%, Chi et al., Citation2005; Chiu, Chen, Huang, & Mau, Citation2005; Niti, Ng, Kua, Ho, & Tan, Citation2007). The relatively higher rate of elderly depression in our result might be attributed to the rapid industrial and cultural changes in Korean society over the past few decades, as mentioned in the introduction. As has been widely investigated, depression has been found to be the strongest predictor of suicidal ideation in community elderly populations (Awata et al., Citation2005; Barnow, Linden, & Freyberger, Citation2004; Yip et al., Citation2003). Our identification of depression as the major contributor to suicidal ideation further supports the evidence of indicated prevention strategies targeting high-risk individuals who have early signs of depression. In two large-scale studies, preventive interventions called Improving Mood: Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment program (IMPACT) (Unützer et al., Citation2002; Unützer et al., Citation2006) and Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (PROSPECT) (Alexopoulos et al., Citation2009; Bruce et al., Citation2004) demonstrated the advantages of indicated preventive interventions of depression in older primary care patients. IMPACT and PROSPECT provided collaborative management, including education, case management, and brief psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy. Trained depression care managers (nurses, psychologists, or social workers) helped physicians recognize depression, offered algorithm-based recommendations, monitored depression, provided brief psychotherapy, and included follow-up. These two studies had been shown to be effective in treating depression and suicidal ideation even in the long term (24 months). Therefore, when dealing with the elderly with suicidal ideation, mental health professionals should be alert to the possible existence of depression and treat or refer appropriately, if indicated.

Along with depression, chronic illness, poor subjective health status, and functional impairment also accounted for a considerable portion in the PAF of suicidal ideation, at 19.4%, 18.9%, and 4.9%, respectively. Chronic illness, poor subjective health status, and functional impairment are especially important in the elderly compared to in younger age groups, who are generally healthy and more independent than the elderly. As elderly people get older, most develop chronic illnesses. Management of a chronic illness is important if they are to successfully maintain their daily lives, including maintaining healthy relationships with their peers. Cheung et al. (Citation2006) found that the PAF for chronic illness was 9.0% but did not investigate the effect of perceived health status in the general population, ages 15 to 59. Almeida et al. (Citation2012) reported that the PAF for poor perceived health status was 7.6% but that chronic illness was not significantly associated with suicidal ideation in community-derived elderly aged 60 years or more. Indeed, the majority of previous studies have reported that poor perceived health is a risk factor for suicidal ideation in the elderly population (Jorm, Henderson, Scott, Korten, Christensen, & Mackinnon, Citation1995; Scocco, Meneghel, Caon, Dello Buono, & De Leo, Citation2001; Yip et al., Citation2003). Although both chronic illness and poor subjective health status were risk factors for depression in the elderly, poor subjective health status might be more strongly associated with depression than chronic illness (Park, Park, Yang, & Chung, Citation2016). In addition, the presence of somatic symptoms that are not fully explained by comorbid physical illness or functional impairment seemed to be an independent factor associated with late-life depression and suicide (Jeong et al., Citation2014). Functional impairment was also a significant risk factor for suicidal ideation in our result and accounted for a considerable portion (4.9%) in the PAF of suicidal ideation. This result was also consistent with previous studies of suicidal ideation in an elderly population (Awata et al., Citation2005; Yip et al., Citation2003). Shah, Hoxey, and Mayadunne (Citation2000) suggested that functional disability and suicidal ideation were independently associated with the mortality of medically ill inpatients and might have a causal effect. Far better characterization of chronic illness, subjective health status, and functional impairment as associated with suicidal ideation deserves particular attention in the elderly, not only because of the high prevalence but because the majority of high-risk individuals with suicide are in active contact with a primary care provider. Luoma, Martin, and Pearson (Citation2002) reported in their review paper that, on average, 45% of individuals who completed suicide had contact with primary care providers within one month of suicide, and this percentage increased to 77% for contact within one year. Adults aged 55 and older especially had higher rates (58% versus 23%) of contact with primary care providers within one month of completed suicide than adults aged 35 and younger. Therefore, primary care providers should be trained to screen for suicidal ideation. Although the recognition and management of depression in the elderly is fundamentally important in reducing suicidal ideation, the significant role of chronic illness, poor subjective health status, and functional impairment is highlighted by our findings. Our findings might be useful in informing strategies for prevention of suicidal ideation, such as targeting those elderly via community-based programs or screening of high-risk groups, such as elderly patients in primary care and hospital settings.

Interestingly, in our results abnormal sleep duration was significantly associated with suicidal ideation, and the PAF for abnormal sleep duration accounted for 14.1%. Our result is somewhat consistent with previous studies. A long sleep duration (≥ 9 hours) was found to be a significant predictor (RR = 4.6) of completed suicide among 11,888 retirement community residents (Ross, Bernstein, Trent, Henderson, & Paganini-Hill, Citation1990). Although short or long sleep durations do not necessarily indicate a sleep disturbance, poor sleep quality was significantly associated with sleep duration (Gilmour et al., Citation2013). Turvey et al. (Citation2002) demonstrated, from a large longitudinal study, that poor sleep quality was associated with increased risk of suicide within 10 years in elderly. Although depression showed the strongest risk for suicide, poor sleep quality increased the suicide risk by 34% (Turvey et al., Citation2002). Gunnell, Chang, Tsai, Tsao, and Wen (Citation2013) demonstrated that both short (< 6 hours) and long (> 8 hours) sleep durations were associated with an increased risk of suicide in a general adult population (average age about 40). The hazard ratios for suicide associated with sleep duration were 3.5 for 0 to 4 hours, 1.5 for 4 to 6 hours, and 1.5 for >8 hours, when compared with sleep duration (6 to 8 hours).

Sleep disturbances in the elderly are often consequent to psychosocial and medical morbidity, such as depression, heart disease, or chronic pain, and not to aging per se (Foley, Ancoli-Israel, Britz, & Walsh, Citation2004). However, growing evidence suggests that the association between sleep disturbance and suicide is not explainable by mental illnesses, which means that sleep disturbance independently affects suicide (Pigeon, Pinquart, & Conner, Citation2012; Goodwin & Marusic, Citation2008). As aging proceeds, sleep patterns change and are characterized by an advanced sleep phase, including earlier bedtimes and wake times, reduced sleep consolidation, and changes in sleep architecture, indicating a transition to lighter sleep (Dijk, Duffy, & Czeisler, Citation2000). Because there is a common misconception among clinicians and the public that sleep disturbances are an inevitable consequence of aging, they are often underrecognized and undertreated. Thus, sleep-related questions and special attention might be needed in the elderly population, and targeting abnormal sleep duration as a warning sign of suicidal ideation might constitute an opportunity for enhanced risk detection, particularly among high-risk elderly.

Also of note in our findings is that poor social support was significantly associated with suicidal ideation, and the PAF for social support accounted for 4.2%. Our results support previous findings showing an association between poor social support and suicidal ideation in elderly populations (Awata et al., Citation2005; Vanderhorst & McLaren, Citation2005). Interestingly, one study reported that poor social support (38.0%) accounted for a larger proportion of cases than depression (Almeida et al., Citation2012). It is generally reported that social networks and support are critical for older people (Litwin, Citation2001). Social support is a coping resource that is obtained from various interpersonal relationships, including family, friends, neighbors, and others, which is helpful in alleviating psychological suffering. Social support has been reported to be an important contributor to health promotion and long-term mortality in the later stages of life (Mazzella et al., Citation2010; Mor-Barak & Miller, Citation1991). The traditional society of Korea is characterized by an extended family system in small villages. However, the social and family system structure in Korea has been changing as a result of rapid industrialization and modernization. The social atmosphere in which children assume responsibility for their elderly parents is fading (Chung & Park, Citation2008). Also, the nuclear family has become more common in Korea, and an increasing number of elderly individuals live apart from their children (Cha, Citation2004). In addition, it is estimated that one-person households with an individual older than age 75 will increase to 2,105,000 households by 2035; this constitutes 51.4% of householders aged over 75 (KNSO, Citation2012). Given these emerging social trends of increase in solitary living (Cha, Citation2004), elderly individuals are becoming more vulnerable to psychological suffering and mental illness. Social factors such as loneliness and social isolation are associated with suicidal behavior in the elderly (Fässberg et al., Citation2012). An intervention that could enhance social support for the elderly might contribute to the prevention of suicidal ideation (Jané-Llopis, Hosman, Jenkins, & Anderson, Citation2003). Cattan, White, Bond, and Learmouth (Citation2005) suggested in their review that group interventions with an educational or social activity could alleviate social isolation and loneliness in the elderly. These issues should be discussed mainly with respect to their public aspects and social support resources. Institutional support, such as welfare centers and mental health centers in the community, could be utilized.

Several noteworthy limitations should be acknowledged in our study. First, our findings should be considered in the context of the limitation of the PAF as a statistical method, because PAF is based on the assumption of causal relationship between the risk factors and the outcome of interest (suicidal ideation). The design of our study was cross-sectional; thus, our findings do not allow for the inference of a causal relationship between suicidal ideation and risk factors. However, indeed, the majority of studies regarding risks for suicidal behavior examining the PAF have been of cross-sectional design (Krysinska & Martin, Citation2009), and the potential applications for PAF are extended to cross-sectional and case-control studies (Eide and Heuch, 2001). Second, our study might be limited by response bias, in that information about risk factors and suicidal ideation was based on retrospective self-reports. In addition, the evaluation time period of the suicidal ideation and risk factors might not overlap because we evaluated suicidal ideation of participants after reaching age 60. Third, in the multiple regression analyses, substantial proportions (15.9%) of the data were excluded due to missing values. These missing data may have led to selection bias and may limit the generalizability of our findings. Fourth, some risk factors of suicidal ideation were not available for analysis, including psychiatric disease other than depression, past psychiatric history, and sexual or physical abuse. However, the strength of our study lies in the use of a large representative sample, obtained using a household sampling procedure in Korea, with a robust response rate and a sizable sample of the elderly aged 65 and older. In addition to the large sample size, the estimation of PAFs associated with risk factors increased the statistical robustness of our results.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the results of our study demonstrate the contributions of various risk factors to suicidal ideation in elderly people. Our findings suggest that, in dealing with elderly people, health care practitioners should pay attention to risk factors with a high PAF, such as depression. Preventive strategies focusing on treating depression in particular might have the greatest impact on reducing suicidal ideation. In addition, mental health centers focused on the specific needs of the elderly population should be established to manage suicidal risk.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jong-Il Park

Jong-Il Park, MD, PhD, Jong-Chul Yang, MD, PhD, Tae Won Park, MD, PhD, and Sang-Keun Chung, MD, PhD, are affiliated with the Department of Psychiatry, Chonbuk National University Medical School, Jeonju, South Korea, and the Research Institute of Clinical Medicine of Chonbuk National University–Biomedical Research Institute of Chonbuk National University Hospital, Jeonju, South Korea.

Jong-Chul Yang

Jong-Il Park, MD, PhD, Jong-Chul Yang, MD, PhD, Tae Won Park, MD, PhD, and Sang-Keun Chung, MD, PhD, are affiliated with the Department of Psychiatry, Chonbuk National University Medical School, Jeonju, South Korea, and the Research Institute of Clinical Medicine of Chonbuk National University–Biomedical Research Institute of Chonbuk National University Hospital, Jeonju, South Korea.

Changsu Han

Changsu Han, MD, PhD, MHS, is affiliated with the Department of Psychiatry, Korea University Ansan Hospital, Korea University College of Medicine, Ansan, South Korea.

Tae Won Park

Jong-Il Park, MD, PhD, Jong-Chul Yang, MD, PhD, Tae Won Park, MD, PhD, and Sang-Keun Chung, MD, PhD, are affiliated with the Department of Psychiatry, Chonbuk National University Medical School, Jeonju, South Korea, and the Research Institute of Clinical Medicine of Chonbuk National University–Biomedical Research Institute of Chonbuk National University Hospital, Jeonju, South Korea.

Sang-Keun Chung

Jong-Il Park, MD, PhD, Jong-Chul Yang, MD, PhD, Tae Won Park, MD, PhD, and Sang-Keun Chung, MD, PhD, are affiliated with the Department of Psychiatry, Chonbuk National University Medical School, Jeonju, South Korea, and the Research Institute of Clinical Medicine of Chonbuk National University–Biomedical Research Institute of Chonbuk National University Hospital, Jeonju, South Korea.

References

- Alexopoulos, G. S., Reynolds, C. F., III, Bruce, M. L., Katz, I. R., Raue, P. J., Mulsant, B. H., … Ten Have, T. (2009). Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT Study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(8), 882–890. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121779

- Almeida, O. P., Draper, B., Snowdon, J., Lautenschlager, N. T., Pirkis, J., Byrne, G., … Pfaff, J. J. (2012). Factors associated with suicidal thoughts in a large community study of older adults. British Journal of Psychiatry, 201(6), 466–472. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.112.110130

- American Psychiatric Association. (2003). Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Retrieved from http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/suicide.pdf

- Amore, M., Baratta, S., Di Vittorio, C., Innamorati, M., & Lester, D. (2012). Suicide among the elderly. In M. Pompili (Ed.), Suicide: A global perspective (pp. 267–278). Sharjah, UAE: Bentham Science.

- Awata, S., Seki, T., Koizumi, Y., Sato, S., Hozawa, A., Omori, K., … Tsuji, I. (2005). Factors associated with suicidal ideation in an elderly urban Japanese population: A community‐based, cross‐sectional study. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 59(3), 327–336. doi:10.1111/pcn.2005.59.issue-3

- Bae, J. N., & Cho, M. J. (2004). Development of the Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale and its short form among elderly psychiatric patients. Journal of psychosomatic research, 57(3), 297–305.

- Barnow, S., Linden, M., & Freyberger, H. J. (2004). The relation between suicidal feelings and mental disorders in the elderly: Results from the Berlin Aging Study (BASE). Psychological Medicine, 34(04), 741–746. doi:10.1017/S0033291703008912

- Beekman, A. T., Copeland, J. R., & Prince, M. J. (1999). Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. British Journal of Psychiatry, 174(4), 307–311. doi:10.1192/bjp.174.4.307

- Benichou, J. (2001). A review of adjusted estimators of attributable risk. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 10(3), 195–216. doi:10.1191/096228001680195157

- Brown, G. K., Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Grisham, J. R. (2000). Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: a 20-year prospective study. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 68(3), 371–377.

- Bruce, M. L., Ten Have, T. R., Reynolds, C. F., III, Katz, I. I., Schulberg, H. C., Mulsant, B. H., … Alexopoulos, G. S. (2004). Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 291(9), 1081–1091. doi:10.1001/jama.291.9.1081

- Cattan, M., White, M., Bond, J., & Learmouth, A. (2005). Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: A systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing and Society, 25(01), 41–67. doi:10.1017/S0144686X04002594

- Cha, H. B. (2004). Public policy on aging in Korea. Geriatrics and Gerontology International, 4(S1), S45–S48. doi:10.1111/ggi.2004.4.issue-s1

- Cheon, J. S., Lee, S. S., Roh, J. R., & Oh, B. H. (2005). Psychosocial factors associated with suicidal ideation among Korean elderly. Journal of Korean Geriatric Psychiatry, 9(2), 132–139.

- Cheung, Y. B., Law, C. K., Chan, B., Liu, K. Y., & Yip, P. S. (2006). Suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts in a population-based study of Chinese people: Risk attributable to hopelessness, depression, and social factors. Journal of Affective Disorders, 90(2), 193–199. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.11.018

- Chi, I., Yip, P. S., Chiu, H. F., Chou, K. L., Chan, K. S., Kwan, C. W., … Caine, E. (2005). Prevalence of depression and its correlates in Hong Kong’s Chinese older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13(5), 409–416. doi:10.1097/00019442-200505000-00010

- Chiu, H. C., Chen, C. M., Huang, C. J., & Mau, L. W. (2005). Depressive symptoms, chronic medical conditions, and functional status: A comparison of urban and rural elders in Taiwan. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(7), 635–644. doi:10.1002/gps.1292

- Cho, M. J., Bae, J. N., Suh, G. H., Hahm, B. J., Kim, J. K., Lee, D. W., & Kang, M. H. (1999). Validation of geriatric depression scale, Korean version (GDS) in the assessment of DSM-III-R major depression. Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association, 38(1), 48–63.

- Cho, M. J., Hahm, B. J., Jhoo, J. H., Bae, J. N., & Kwon, J. S. (1998). Prevalence of cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms among the elderly in an urban community. Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association, 37(2), 352–362.

- Chopra, M. P., Zubritsky, C., Knott, K., Ten Have, T., Hadley, T., Coyne, J. C., & Oslin, D. W. (2005). Importance of subsyndromal symptoms of depression in elderly patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13(7), 597–606. doi:10.1097/00019442-200507000-00008

- Chung, S., & Park, S. J. (2008). Successful ageing among low-income older people in South Korea. Ageing and Society, 28(8), 1061–1074. doi:10.1017/S0144686X08007393

- Conwell, Y., Duberstein, P. R., & Caine, E. D. (2002). Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biological Psychiatry, 52(3), 193–204. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01347-1

- Conwell, Y., Duberstein, P. R., Cox, C., Herrmann, J., Forbes, N., & Caine, E. D. (1998). Age differences in behaviors leading to completed suicide. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 6(2), 122–126. doi:10.1097/00019442-199805000-00005

- Darrow, L. A., & Steenland, N. K. (2011). Confounding and bias in the attributable fraction. Epidemiology, 22(1), 53–58. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181fce49b

- Dijk, D. J., Duffy, J. F., & Czeisler, C. A. (2000). Contribution of circadian physiology and sleep homeostasis to age-related changes in human sleep. Chronobiology International, 17(3), 285–311. doi:10.1081/CBI-100101049

- Eide, G. E., & Heuch, I. (2001). Attributable fractions: fundamental concepts and their visualization. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 10(3), 159–193.

- Fässberg, M. M., Orden, K. A. V., Duberstein, P., Erlangsen, A., Lapierre, S., Bodner, E., … Waern, M. (2012). A systematic review of social factors and suicidal behavior in older adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(12), 722–745. doi:10.3390/ijerph9030722

- Foley, D., Ancoli-Israel, S., Britz, P., & Walsh, J. (2004). Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: Results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America survey. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56(5), 497–502. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.010

- Gilmour, H., Stranges, S., Kaplan, M., Feeny, D., McFarland, B., Huguet, N., & Bernier, J. (2013). Longitudinal trajectories of sleep duration in the general population. Health Reports, 24(11), 14–20.

- Goldney, R. D. (2004). Suicide research based on Danish registers. Crisis, 25(4), 189–190. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.25.4.189

- Goldney, R. D., Dal Grande, E., Fisher, L. J., & Wilson, D. (2003). Population attributable risk of major depression for suicidal ideation in a random and representative community sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 74(3), 267–272. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00017-4

- Goldney, R. D., Wilson, D., Grande, E. D., Fisher, L. J., & McFarlane, A. C. (2000). Suicidal ideation in a random community sample: Attributable risk due to depression and psychosocial and traumatic events. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 34(1), 98–106. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2000.00646.x

- Goldsmith, S. K., Pellmar, T. C., Kleinman, A. M., & Bunney, W. E. (2002). Reducing suicide: A national imperative. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Goodwin, R. D., & Marusic, A. (2008). Association between short sleep and suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among adults in the general population. Sleep, 31(8), 1097–1101.

- Greenland, S., & Drescher, K. (1993). Maximum likelihood estimation of the attributable fraction from logistic models. Biometrics, 49, 865–872. doi:10.2307/2532206

- Gunnell, D., Chang, S. S., Tsai, M. K., Tsao, C. K., & Wen, C. P. (2013). Sleep and suicide: An analysis of a cohort of 394,000 Taiwanese adults. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(9), 1457–1465. doi:10.1007/s00127-013-0675-1

- Jané-Llopis, E. V. A., Hosman, C., Jenkins, R., & Anderson, P. (2003). Predictors of efficacy in depression prevention programmes: Meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 183(5), 384–397. doi:10.1192/bjp.183.5.384

- Jeong, H. G., Han, C., Park, M. H., Ryu, S. H., Pae, C. U., Lee, J. Y., … Steffens, D. C. (2014). Influence of the number and severity of somatic symptoms on the severity of depression and suicidality in community‐dwelling elders. Asia‐Pacific Psychiatry, 6(3), 274–283. doi:10.1111/appy.2014.6.issue-3

- Jorm, A. F., Henderson, A. S., Scott, R., Korten, A. E., Christensen, H., & Mackinnon, A. J. (1995). Factors associated with the wish to die in elderly people. Age and Ageing, 24(5), 389–392. doi:10.1093/ageing/24.5.389

- Jung, K. H., Lee, Y. K., Park, B. M., Lee, S. J., & Lee, Y. H. (2012). Analysis of the survey of living conditions and welfare needs of Korean older persons. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. Report No.: Research Report 2012-47-14.

- Kessler, R. C., Borges, G., & Walters, E. E. (1999). Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(7), 617–626.

- Kim, J. M., Shin, I. S., Yoon, J. S., & Stewart, R. (2002). Prevalence and correlates of late‐life depression compared between urban and rural populations in Korea. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(5), 409–415. doi:10.1002/gps.622

- Korea National Statistical Office. (2010). The aged statistics. Daejeon, South Korea: Korea National Statistical Office.

- Korea National Statistical Office. (2012). Household projections for Korea: 2010–2035. Daejeon, South Korea: Korea National Statistical Office.

- Korea National Statistical Office. (2014). 2013 cause of mortality statistics. Daejeon, South Korea: Statistics Korea.

- Korean Association for Suicide Prevention. (2011). Annual suicide report in Korea. Seoul: Korean Association for Suicide Prevention.

- Krysinska, K., & Martin, G. (2009). The struggle to prevent and evaluate: Application of population attributable risk and preventive fraction to suicide prevention research. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 39(5), 548–557. doi:10.1521/suli.2009.39.5.548

- Lee, D. Y., Lee, K. U., Lee, J. H., Kim, K. W., Jhoo, J. H., Kim, S. Y., … Woo, J. I. (2004). A normative study of the CERAD neuropsychological assessment battery in the Korean elderly. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 10(01), 72–81. doi:10.1017/S1355617704101094

- Lee, J. H., Lee, K. U., Lee, D. Y., Kim, K. W., Jhoo, J. H., Kim, J. H., … Woo, J. I. (2002). Development of the Korean version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease assessment packet (CERAD-K): Clinical and neuropsychological assessment batteries. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(1), P47–P53. doi:10.1093/geronb/57.1.P47

- Lee, M. (2007). Improving services and support for older people with mental health problems: The second report from the UK Inquiry into Mental Health and Well-Being in Later Life. London, United Kingdom: Age Concern.

- Levin, M. L. (1953). The occurrence of lung cancer in man. Acta-Unio Internationalis Contra Cancrum, 9(3), 531–541.

- Litwin, H. (2001). Social network type and morale in old age. The Gerontologist, 41(4), 516–524. doi:10.1093/geront/41.4.516

- Luoma, J. B., Martin, C. E., & Pearson, J. L. (2002). Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(6), 909–916. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909

- Mann, J. J., Apter, A., Bertolote, J., Beautrais, A., Currier, D., Haas, A., … Hendin, H. (2005). Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. JAMA, 294(16), 2064–2074. doi:10.1001/jama.294.16.2064

- Marengoni, A., Angleman, S., Melis, R., Mangialasche, F., Karp, A., Garmen, A., … Fratiglioni, L. (2011). Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Research Reviews, 10(4), 430–439. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003

- Mark, J., Williams, G., & Swales, M. (2004). The use of mindfulness-based approaches for suicidal patients. Archives of Suicide Research, 8(4), 315–329. doi:10.1080/13811110490476671

- Mazzella, F., Cacciatore, F., Galizia, G., Della-Morte, D., Rossetti, M., Abbruzzese, R., … Abete, P. (2010). Social support and long-term mortality in the elderly: Role of comorbidity. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 51(3), 323–328. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2010.01.011

- Mireault, M., & De Man, A. F. (1996). Suicidal ideation among the elderly: Personal variables, stress, and social support. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 24(4), 385–392. doi:10.2224/sbp.1996.24.4.385

- Mor-Barak, M. E., & Miller, L. S. (1991). A longitudinal study of the causal relationship between social networks and health of the poor frail elderly. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 10(3), 293–310. doi:10.1177/073346489101000305

- Mortensen, P. B., Agerbo, E., Erikson, T., Qin, P., & Westergaard-Nielsen, N. (2000). Psychiatric illness and risk factors for suicide in Denmark. The Lancet, 355(9197), 9–12. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06376-X

- Niti, M., Ng, T. P., Kua, E. H., Ho, R. C. M., & Tan, C. H. (2007). Depression and chronic medical illnesses in Asian older adults: The role of subjective health and functional status. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(11), 1087–1094. doi:10.1002/gps.1789

- OECD. (2014). OECD factbook: Economic, environmental, and social statistics 2014. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

- Ono, Y., Tanaka, E., Oyama, H., Toyokawa, K., Koizumi, T., Shinohe, K., … Yoshimura, K. (2001). Epidemiology of suicidal ideation and help‐seeking behaviors among the elderly in Japan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 55(6), 605–610. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1819.2001.00912.x

- Park, B. C. B., & Lester, D. (2006). Social integration and suicide in South Korea. Crisis, 27(1), 48–50. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.27.1.48

- Park, B. C. B., & Lester, D. (2008). South Korea. In P. S. F. Yip (Ed.), Suicide in Asia: Causes and prevention (pp. 19–30). Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong University Press.

- Park, J. H., Kim, K. W., Kim, M. H., Kim, M. D., Kim, B. J., Kim, S. K., … Ryu, S. H. (2012). A nationwide survey on the prevalence and risk factors of late life depression in South Korea. Journal of Affective Disorders, 138(1), 34–40. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.038

- Park, J. I., Park, T. W., Yang, J. C., & Chung, S. K. (2016). Factors associated with depression among elderly Koreans: The role of chronic illness, subjective health status, and cognitive impairment. Psychogeriatrics, 16(1), 62–69. doi:10.1111/psyg.12160

- Pigeon, W. R., Pinquart, M., & Conner, K. (2012). Meta-analysis of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 73(9), e1160–e1167. doi:10.4088/JCP.11r07586

- Pirkis, J., Burgess, P., & Dunt, D. (2000). Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Australian adults. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 21(1), 16–25. doi:10.1027//0227-5910.21.1.16

- Reynolds, C. F. (2009). Prevention of depressive disorders: A brave new world. Depression and Anxiety, 26(12), 1062–1065. doi:10.1002/da.v26:12

- Reynolds, C. F., III, Cuijpers, P., Patel, V., Cohen, A., Dias, A., Chowdhary, N., … Albert, S. M. (2012). Early intervention to reduce the global health and economic burden of major depression in older adults. Annual Review of Public Health, 33, 123–135. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124544

- Rockhill, B., Newman, B., & Weinberg, C. (1998). Use and misuse of population attributable fractions. American Journal of Public Health, 88(1), 15–19. doi:10.2105/AJPH.88.1.15

- Ross, R. K., Bernstein, L., Trent, L., Henderson, B. E., & Paganini-Hill, A. (1990). A prospective study of risk factors for traumatic deaths in a retirement community. Preventive Medicine, 19(3), 323–334. doi:10.1016/0091-7435(90)90032-F

- Scocco, P., Meneghel, G., Caon, F., Dello Buono, M. D., & De Leo, D. (2001). Death ideation and its correlates: Survey of an over-65-year-old population. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 189(4), 210–218. doi:10.1097/00005053-200104000-00002

- Shah, A. (2007). The relationship between suicide rates and age: An analysis of multinational data from the world health organization. International Psychogeriatrics, 19(6), 1141–1152. doi:10.1017/S1041610207005285

- Shah, A., Hoxey, K., & Mayadunne, V. (2000). Some predictors of mortality in acutely medically ill elderly inpatients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(6), 493–499. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-1166

- Suh, G. H., Kim, J. K., Jung, H. Y., Kim, M. J., & Cho, M. J. (1999). Wish to die and associated factors in the rural elderly. Journal of Korean Geriatric Psychiatry, 3(1), 70–77.

- Turvey, C. L., Conwell, Y., Jones, M. P., Phillips, C., Simonsick, E., Pearson, J. L., & Wallace, R. (2002). Risk factors for late-life suicide: A prospective, community-based study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 10(4), 398–406. doi:10.1097/00019442-200207000-00006

- Unützer, J., Katon, W., Callahan, C. M., Williams, J. J., Hunkeler, E., Harpole, L., … the IMPACT Investigators. (2002). Improving mood-promoting access to collaborative treatment: Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 288(22), 2836–2845. doi:10.1001/jama.288.22.2836

- Unützer, J., Tang, L., Oishi, S., Katon, W., Williams, J. W., Hunkeler, E., … Langston, C. (2006). Reducing suicidal ideation in depressed older primary care patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(10), 1550–1556. doi:10.1111/jgs.2006.54.issue-10

- Vanderhorst, R. K., & McLaren, S. (2005). Social relationships as predictors of depression and suicidal ideation in older adults. Aging and Mental Health, 9(6), 517–525. doi:10.1080/13607860500193062

- Won, C. W., Rho, Y. G., SunWoo, D., & Lee, Y. S. (2002). The validity and reliability of Korean Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (K-IADL) scale. Journal of the Korean Geriatrics Society, 6(4), 273–280.

- Yen, Y. C., Yang, M. J., Yang, M. S., Lung, F. W., Shih, C. H., Hahn, C. Y., & Lo, H. Y. (2005). Suicidal ideation and associated factors among community‐dwelling elders in Taiwan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 59(4), 365–371. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01387.x

- Yip, P. S., Chi, I., Chiu, H., Wai, K., Conwell, Y., & Caine, E. (2003). A prevalence study of suicide ideation among older adults in Hong Kong SAR. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(11), 1056–1062. doi:10.1002/gps.1014