ABSTRACT

This essay identifies how the very conception of public woman is infused with the opprobrium hurled against a wanton woman – a sexualized figure who has lost claims to moral standing or social worth. Our analysis begins diachronically by using thin description to trace the historical conflation of public woman in general, and Black woman in particular, with prostitute to outline the contours of the trope of public woman that have solidified across time. We document how the public woman became equated with prostitute, and then how the label prostitute was affixed to women in public to situate them as promiscuous or prurient. Our analysis proceeds synchronically as we argue that the toxic archive of memes and hashtags that name Kamala Harris a “ho” operates as a contemporary iteration of misogynoir that conflates public woman with prostitute. The result of our analysis is an identification of the digital public woman wherein the acceleration and repetition of such tropes ensures a recalcitrant public sentiment toward public women and hides the technological and rhetorical connections that intensify such public feelings.

In August 2020, the National Basketball Association fired independent contractor Bill Baptist, a Houston-based photographer who had worked with the Rockets for over 30 years. The reason: Baptist posted a meme on his Facebook page that was a modified logo for the Biden–Harris campaign that read “Joe and the Hoe.” Baptist had seen this popular meme and chose to circulate it, seemingly unfazed by the blatant misogyny and racism within the image, even going so far as to claim the meme did not reflect his “personal views.”Footnote1

This casual, mundane circulation of a racist and misogynistic meme warrants attention. It is not novel, idiosyncratic, unique, or an outlier. The meme recited a centuries-long trope leveraged against women in general and Black women in particular: a public woman is a prostitute. In fact, we open with this meme not to focus on this moment, but to make clear the practice of conflating public woman with prostitute/whore is not an historical anachronism. We italicize public woman to make clear it is a phrase with distinct meaning, one that continues to lurk in understandings of women, particularly Black women, who claim space in the public sphere.

The conflation of public woman with prostitute is an example of “despicable discourse” (identified by Mary Stuckey as “the problem of how to resist stereotypes without also reinscribing them”Footnote2). We seek to challenge the stereotypical conflation between wantonness and publicity, which often operates at a subterranean level, without also reinscribing it when we dredge up its past to explore its implications for the present. We amass anecdotal evidence both diachronically and synchronicallyFootnote3 to document the historic conflation of public woman with prostitute and its continued circulation and impacts in contemporary public discourse. To be clear, our attention to the deployment of prostitution is not a rejection of sex work; prostitutes absolutely have a place in public as public women and as women in public. At the same time a delinking of public woman from the dishonorable implications of prostitution is needed so, too, is a full-throated defense of sex workers as having a place in public in all its forms, economic and political.

Although tethered to the current moment’s circulation of prostitute memes about public figure Kamala Harris, this essay is about more than just those memes. Our broad diachronic argument is that, across time, the conflation of public woman with prostitute has circumscribed women’s political agency (in general) and Black women’s agency (in particular), and such conflation continues to seep into contemporary disquiet with women in public. Our narrower synchronic argument is the proliferation of memes about Harris are simply the most recent proof the conflation of public woman with prostitute persists and, instead of weakening, is supercharged by digital misogynoir.

This essay’s argument highlights how the very conception of public woman is infused with the opprobrium hurled against a wanton woman – a woman whose very publicness calls into question her moral qualifications because to be a woman in public is to be a sexualized figure who has lost claims to moral standing or social worth. A nuanced distinction between those who are sexually objectified and those who are sexualized is in operation. Although a sexually objectified woman can still be considered morally pure because she is characterized as passively the object of others’ desire, a sexualized woman is presumptively impure because she is characterized as actively seeking sex, for pleasure or compensation, and thus is stripped of claims to morality and social standing. Despicably, the public woman forfeits her claim to public standing by the very nature of her publicness.

Our analysis begins diachronically by using thin description to trace the historical conflation of public woman in general, and Black women in particular, with prostitute to outline the contours of the trope of public woman that have solidified across time. We document and analyze myriad instances in which public woman became equated with prostitute, and then how the label prostitute was affixed to women in public generally, and to Black women particularly, to situate them as promiscuous or prurient, an object of moral and social derision. This historical analysis is essential to understanding the contemporary manifestations of public-woman-as-prostitute.

Second, we review existing literature that details how digital circulation entrenches misogynoir in today’s media ecology, where social media content and other iterative posts (such as memes and hashtags) are a location in which the trope of the public woman is used as to demean women.

Third, we pivot our analysis synchronically to the current moment. We compile and analyze the toxic archive of hypersexualized memes, hashtags, and talking points circulating during and after the 2020 election that trafficked in the trope of public-woman-as-prostitute. The proliferation and trade in memes about Kamala Harris and the media coverage that alleged she brokered sexual actions for political favors reduced her to a sexualized figure, which at scale intensifies the impacts noted in existing research on sexist discourse in politics.

Fourth, we end by exploring how Harris’s responses leaning into Momala (the nick-name given to Harris by Ella and Cole Emhoff) still positioned Harris within the matrices of rhetorical misogynoir, demonstrating the stickiness of despicable discourse. The result of our analysis is a mapping of the public-woman-as-prostitute trope and an identification of the digital public woman wherein the acceleration and repetition of such tropes ensure a recalcitrant public sentiment toward public women and camouflage the technological and rhetorical connections that intensify such public feelings.Footnote4

Public-woman-as-prostitute: tracking circulation via methodological thinness

Proving the phrase public woman is a synonym for prostitute, and the synonymic meaning embeds even in contemporary connotations attached to the phrase, requires a note on method. Ruja Benjamin, in Race after Technology, borrows from John L. Jackson’s work on thin description to challenge the distinction of “evidence versus anecdote,” a distinction that must be undone to study the way practices of racialization (and we would add sexualization) treat people as a surface.Footnote5 Thin description, the collection of a range of anecdotes across time and space, “allows greater elasticity, engaging fields of thought and action too often disconnected. This analytic flexibility … is an antidote to digital disconnection, tracing links between individual and institutional, mundane and spectacular, desirable and deadly in a way that troubles easy distinctions.”Footnote6 Even though Benjamin focuses on the utility of thin description for the analysis of digital circulations, we note how disconnected analog artifacts, too, racialize and sexualize people, treating them as surface.

Thin descriptions of a diachronic range of individual and institutional artifacts across time and space (e.g., government licenses, medical text drawings, bisque figures, tropes, editorial letters, Biblical references, and song lyrics) demonstrate how the so-called prostitute has been conflated with public woman and sutured onto the surface of women in public generally and Black women specifically. Our compilation of these artifacts is a core part of our analysis, “not an analytic failure, but an acceptance of fragility” because “racism [and we would add sexism and, thus, racialized sexism and sexualized racism] is a mercurial practice, shape-shifting, adept at disguising itself in progressive-like rhetoric.”Footnote7 Thin descriptions require agility and, as such, we offer a galloping ride through historical anecdotes that track the mercurial practices that conflate public woman in general, and Black women in particular because they are presumptively always already public, with prostitute and suture them so tightly that contemporary memes effortlessly can replicate, circulate, and mutate this conflation.Footnote8 This historical legacy is a dexterous practice that legitimates violence against public Black women.

Rhetorical history suggests women faced considerable obstacles when they advocated about public concerns. Although women’s public participation is far richer and more complex than the narrative of separate public and private spheres would indicate,Footnote9 women still faced discipline for violating social dictates relegating them to the home. The separate spheres’ casting of (presumably white) woman as the angel in the house and valorization of domestic white womanhood are well-known. When white women ventured into the contentious realms of politics and the economy, they were bad women because they lost their femininity. Tomes of research demonstrate women in public were bad women because they were seen as unfeminine. However, not all women were disciplined in the same way. Some women, particularly women of color and poor women, were never afforded the femininity attached to domesticity.Footnote10

Less discussed is how characterizations hypersexualized women who did venture into public. Our argument is that characterizations of public woman depicted women in public as bad women not because they were unfeminine but because they were cast as morally suspect. A public woman was a bad woman because she was promiscuous. As we detail below, historically, the phrase public woman literally meant prostitute. Moreover, because Black women were never afforded their own domesticity and white people sought to legitimize sexual violence against them,Footnote11 Black women were hypersexualized presumptively, as prostitutes. According to Jacqueline Jones Royster, Black women who entered the public had to face “disempowering images of themselves as amoral, unredeemable, and undeserving, they have had to carve out a space of credibility and respect as women.”Footnote12 The following anecdotes provide evidence for our claim that public women, and particularly Black women in public, were rhetorically fused with prostitution.

Anecdote one: an 1862 General Order. In May of 1862, the commander of the Union forces in New Orleans issued the following General Order in response to public actions of white women:

As the officers and soldiers of the United States have been subject to repeated insults from the women (calling themselves ladies) of New Orleans … it is ordered that hereafter when any female shall, by word, gesture or movement, insult or show contempt for any officer or soldier of the United States, she shall be regarded and held liable to be treated as a woman of the town plying her avocation.Footnote13

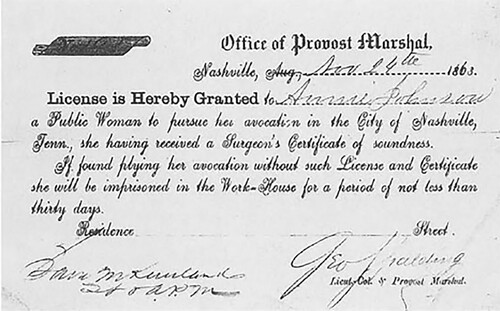

Anecdote two: an 1863 prostitution license. On August 20, 1863, the Nashville Experiment started. Union General Granger and Provost Lt. Col. George Spalding, after an eviction policy failed, legalized prostitution in an effort to save the Union army from sexually transmitted infections. The process of legalization required a sex worker receive a license, weekly medical examinations, access to “a special hospital for ailing prostitutes,” and a 30-day sentence to the city workhouse if she was found “plying her trade without a license and health certificate.”Footnote15 The license in question was granted to “a Public Woman to pursue her avocation.”Footnote16 Public woman and prostitute were synonyms. Of the 500 women who were licensed, 50 were Black women ().Footnote17

Figure 1. Nashville Experiment Prostitution License, reproduced from Jones, courtesy of Tennessee State Library & Archives.

These anecdotes illustrate how being in public meant a woman made herself sexually available to the public composed of men and how a public woman is presumptively a prostitute until proven otherwise. Moreover, the licensure distinction illustrates the ways publicness was dissected: White women were allowed to license themselves, while far fewer Black women were licensed, suggesting even statured forms of publicness were reserved and tiered when it came to racialized divisions. The suturing of public woman and prostitute was even more tightly knotted for Black women, illustrated in these further historical notations.

Anecdote three: nineteenth-century art and medical textbooks. Historically, white supremacist discourses treated all Black women as prostitutes. One reason is because Black women were never afforded the privilege of domesticity; they were forced to work and move in public as a result of enslavement or economic need. A second reason is Black women, whether in public or private, were coded as hypersexual. Sander L. Gilman’s oft-cited study of nineteenth-century artistic and medical iconography traces how the female Hottentot came “to represent the black female in nuce, and the prostitute to represent the sexualized woman” and how these two “seemingly unrelated female images” become linked as “the perception of the prostitute … merged with the perception of the black.”Footnote18 Given Black women were presumed “always-already sexual,”Footnote19 prostitute was synonymous with Black woman and Black woman with prostitute. Historian Paula Giddings convincingly demonstrates how, by the end of the nineteenth century, the Black woman was “seen in dualistic opposition to their upper-class, pure, and passionless white sisters” because Black women were “the epitome of the immorality, pathology, and impurity of the age.”Footnote20 A Black woman was always already a public woman.

Anecdote four: an 1895 editor’s open letter. In a well-known response to Ida B. Wells’s anti-lynching work, the president of the Missouri Press Association penned a declaration against Black women, describing them as “wholly devoid of morality” and declaring that all Black women are “prostitutes and all are natural liars and thieves.”Footnote21 To silence a Black woman who was a public figure, opponents merely labeled all Black women prostitutes.

Anecdote five: girls and women walking on streets. In December 1895, New York City police arrested young, white, working-class Amelia Elizabeth “Lizzie” Schauer for engaging in disorderly conduct. Her crime? She was out in public at night and asked for directions from two men. The fact that she was a woman, alone, and on a public street was enough to prove she was a “‘public woman,’ or prostitute.”Footnote22 Schauer was not released from the workhouse until local newspapersFootnote23 campaigned for her release and she was examined by a doctor who affirmed she was a “good girl,” a virgin.Footnote24

Public outcry and newspaper coverage of Schauer’s case led to her release, a precursor to the “missing white woman syndrome” identified by Gwen Ifill over two decades ago to describe how white women are seen as in need of rescue, while other public women are merely a problem.Footnote25 Let us be clear: many Black women and girls went missing from public streets from 1882–1925, locked into jails, workhouses, and reformatories as a result of vagrancy laws that criminalized Black women for walking, “running,” or “roaming” public streets.Footnote26 Saidiya Hartman’s exploration of “wayward” Black girls and women details how simply being in public meant “[a]ll colored women were vulnerable to being seized at random by the police; those who worked late hours, or returned home after the saloon closed or the lights were extinguished at the dance hall, might be arrested and charged with soliciting.”Footnote27 Being out in public, “[b]eing too loud or loitering in the hallway of your building or on the front stoop was a violation of the law; … running the streets was prostitution.”Footnote28 A woman who walked on public streets, who ventured outside her home to work or to engage in politics or to visit friends, was a streetwalker. A woman on a street corner is plying her trade, not about to mount a soapbox.

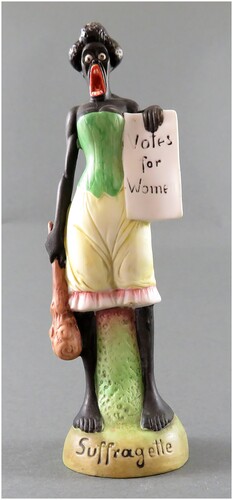

Anecdote six: a 1915 German-made bisque figure of a Black woman, possibly Sojourner Truth, showing her en dishabille. The figure, a pre-digital meme, could be read as ridicule of the bloomer movement, or as a recreation of the exaggerated story that Sojourner Truth bared her breast (or shoulders) when demonstrating her womanhood in “Aren’t I a Woman,”Footnote29 or as an illustration of the threat of Black women voting. Regardless, the figure recites the image of Black women as hypersexualized prostitutes as an argument against legal recognition through enfranchisement ().

Figure 2. Schafer and Vater bisque figurine, circa 1915. Image courtesy of Kenneth Florey.

Anecdote seven: the Jezebel. Historically, the Biblical figure of Jezebel was the archetype of the wicked woman, wicked because she was associated with false prophets and acted as a political power in her own right. Interestingly, as a Christian figure, the nature of the Jezebel’s political and religious wickedness evolved into a sexual wickedness as a Jezebel became a fallen woman, a sexual woman, a prostitute. Patricia Hill Collins identifies four controlling images of Black women: the mammy, the black matriarch, the welfare mother, and the Jezebel.Footnote30 Of particular relevance for this essay is the Jezebel, who possesses a “deviant Black female sexuality” characterized by being “sexually aggressive.”Footnote31 She is not an object of desire, but an agent of deviant sexual agency.

The Jezebel trope justified sexual assault and economic exploitation.Footnote32 If Black women were sexually aggressive, this meant they were always willing, which, in turn, legitimized white men’s widespread sexual assault of Black women. Furthermore, if Black women were sexually aggressive, they were simultaneously fertile and therefore able to reproduce future laborers. The trope of the Jezebel became an anchor point, a way to manage how Black women as public figures were to be treated.

Anecdote eight: the ho. Black-woman-as-prostitute circulated across space and time and was not confined solely to White Supremacists. Mireille Miller-Young argues the “ho” of “black vernacular hip hop” is the updated “version of the super-sexual Jezebel or whorish ‘naughty woman’” targeted specifically at “black working-class or sexual nonconformist womanhood since the early 1990s.”Footnote33 Ho, as a trope, circulates across popular culture in “pornography, and commercial hip hop discourse, including in song lyrics and visual imagery used in videos, concerts, and marketing.”Footnote34

The figure of the ho in rap music recirculates the good/bad woman distinction. Shanara R. Reid Brinkley’s analysis of rap music and videos notes how “the good/bad black woman dialectic was described in terms of the queen or princess vs. the ho (whore). The ‘queen’ represents the good black woman and the ‘ho’ is the bad black woman.”Footnote35 The circulation of the ho trope in a number of locations entrenches social perceptions of Black women as a Jezebel, “ho,” or “bitch,” depictions that participate in the “degradation of black femininity.”Footnote36

These figures recur throughout different periods to discipline and control public women, particularly Black public women. The 1990s convergence of hip-hop and pornography’s mainstreaming into commercial media re-entrenched the Jezebel in public understandings and depictions of Black female sexuality.Footnote37 While Hill Collins identifies the Biblical origins of the Jezebel trope, Miller-Young diagnoses the current moment as one where “the discourse and structural forces that surround black women and shape their experiences are increasingly bound up with this trope.”Footnote38 The ubiquitous usage of ho, combined with the historical power of the Jezebel and public woman tropes, means that once this label is attached to a Black woman, it sticks.

These anecdotes illustrate how public woman as a figure, and particularly the Black public woman, became coded as prostitute through a whole host of institutional and individual discourses and practices. Accusations of prostitute hurled at Black women like Wells, though, were not about sexual desire, but more about social opprobrium. Black women were bad women, not just bad women. Although such constructions might have excused white men’s sexual attraction to Black women, they also made it clear Black women were not welcome into public discourse because their access to public space made them public women.

Economically privileged white women could respond to this public opprobrium by retreating into domesticity and by positioning themselves on the virgin side of the virgin/whore dichotomy. Black women, particularly Black working women (which was most Black women), had few options to rebuke such appeals. As Chandra Talpade Mohanty makes clear:

Ideologies of womanhood have as much to do with class and race as they have to do with sex. Thus, during the period of American slavery, constructions of white womanhood as chaste, domesticated, and morally pure had everything to do with corresponding constructions of black slave women as promiscuous, available plantation workers. It is the intersections of the various systemic networks of class, race, (hetero)sexuality, and nation, then, that positions us as “women.”Footnote39

This conflation of public woman, Black woman, citizenship status, and criminality is not relegated to a past long gone. Amy Brandzel’s critique of discourses of citizenship notes how “Antiblackness and the specter of Black ‘criminality’ constantly haunts discourses of citizenship, and, as such, is a readily available discourse for others to use to claim their righteous inclusion.”Footnote41 As Black women have claimed space in public, accusations of being public women haunt them.

Digital misogynoir

We connect our analysis of historical artifacts to our analysis of contemporary memes with a short interlude that introduces an important heuristic term (misogynoir) and a new rhetorical context (the digital). Our goal here is to illustrate how historical tropes of public woman gain traction today.

Misogynoir is a term introduced in 2008 by Moya Bailey and Trudy (aka @thetrudz).Footnote42 Bailey explains how the neologism was necessary “to describe the anti-Black racist misogyny that Black women experience, particularly in US visual and digital culture.”Footnote43 Although Bailey uses the term to describe contemporary digital culture, our anecdotes identify misogynoir in the circulation of memes across analog forms like medical textbooks, music, bisque figures, licenses, and Biblical references.

We amplify Bailey’s declaration that broader public discourses about Black women “as animalistic, strong, and insatiable have had material consequences on their lives and bodies since Africans’ nonconsensual arrival in the West.”Footnote44 Patricia Hill Collins and bell hooks have amply demonstrated how “controlling images,” such as tropes, shape oppressive systems.Footnote45 Hip-hop feminist scholars such as Joan Morgan, Brittney Cooper, and Treva Lindsey have expanded notions of how feminist criticism of these figures and tropes should proceed.Footnote46 Catherine Knight Steele’s recent work extends hip-hop feminism to digital Black feminism, arguing that the term must be able to reflect ongoing tensions that exist online and that are specific to the time periods in which digital practices are used within matrices of oppression.Footnote47 The same critical lens taken to popular culture must be turned towards studying the political arena. Black woman as public woman permeates discourses and, to be challenged, it needs to be named. Yet, the circulatory power of iconography and imagery changes as new modes of address are cultivated. Digital modes of misogynoir intensify the circulatory power of the Jezebel/ho/public woman trope.

Historically, both institutional (e.g., government licenses, medical text drawings, editorial letters) and cultural (e.g., bisque figures, tropes, song lyrics) operated as powerful (and violent) technologies of control, surveillance, and policing. Today, no less powerful (and violent) technologies of control, surveillance, and policing are enmeshed within the social media platforms and content that punctuate daily life. One of the most significant vehicles for shaping today’s understanding of public women is the use of memesFootnote48 and other digital shorthand that entrench sexist, racist, and sexualized – misogynoir – stereotypes of Black women, magnified by visual technologies and cultural practices of circulation. Moya Bailey urges us to see “the power of the image to serve the hegemony of ‘white supremacist capitalist patriarchy’ by controlling the way society views marginalized groups and how we view ourselves.”Footnote49 The figure, the image, and the trope matter as they skitter across digital surfaces and, in so skittering, construct the surface of the bodies to which they refer.

Misogynoir discourses and practices are central to how digital spaces operate and constitute Black women as figures against which hatred and violence are legitimated, if not encouraged. In other words, the misogynoir of digital public culture ensures memes, commentary, and even tweeted death threats are mundane, if not acceptable, forms of public discourse that reify racist digital and material structures dehumanizing Black women.Footnote50 Examining the specific ways digital content shapes the contours of such oppression is necessary.

For Black women especially, Kishonna Gray argues “modern digital segregation mirrors the historical practice of designating space as ‘whites only’.”Footnote51 Such segregationist practices include online harassment, lack of inclusion, toxic environments, and outright violence. For Black women, these modes of digital segregation exemplify the desire and brutality of misogynoir.

Digital misogynoir also stalks Black women political candidates. Scholars must not trivialize memes (or similar digital discourses) because their effects are not trivial; they are deployed to minimize Black women as public figures, expel women from the public, re-entrench hegemonic understandings of race, and limit the capacity for change. The digital world accelerates the speed of such insults, ensuring it is not just one audience who hears the insult, but a wide swath of the public that comes to understand public women as women to be brutalized, as both available to be sexualized and simultaneously punished for their sexualization.Footnote52

The circulatory nature of these rhetorical forms entrenches misogynoir in specific ways. They rely on preponderance: their ubiquity makes them appear reasonable, descriptive, and true.Footnote53 The memes and other digital content deploying misogynoir against Kamala Harris demonstrate the extent to which the public woman trope continues to animate politics. According to the Pew Research Center, “one in five adults get their political news from social media.”Footnote54 Given what is known about how algorithms are structured (and how quickly one can encounter a toxic archive on the internet), 20 percent of voters (at least) are only a few clicks away from seeing these memes. Memes, and internet discourse more broadly, are mainstream political commentary. Therefore, scholarly attention must be paid to the differential uptake of misogynoir in digital spaces. With memes and other digital hashtags, attacks bubbling up in cloistered toxic technocultures are leveraged against public women to shape politics.Footnote55

Digital misogynoir’s toxic archive targeting Kamala Harris

Those who run for elected office allow themselves to be made visible in culture, even more so in an intensely visual culture. To run for office, cis-gendered women candidates need to appear to be good women and good candidates for public office, two attributes that combine into the oxymoron of a good public woman.Footnote56 A woman may forfeit her goodness in many ways. She can be a bad woman because she is not feminine; by definition seeking office means a woman is being ambitious, power-seeking, public, and a leader, none of which are intelligible as feminine.Footnote57 She also can be a bad woman because her public-ness is sexualized.Footnote58

Analyses of media coverage of (predominantly white) women candidates have long noted the attention to women’s appearance and the reduction of women to fetish objects.Footnote59 Roseann M. Mandziuk notes how this focus on appearance is “a key point of contention when considering whether a woman is performing the intelligible version of her gender, particularly as that woman enters into public spaces.”Footnote60 Diana B. Carlin and Kelly Winfrey identify how Rosabeth Moss Kanter’s four archetypes of professional woman as “seductress or sex object, mother, pet, and iron maiden” structured media coverage of Sarah Palin and Hillary Clinton in 2008.Footnote61 Karrin Vasby Anderson names how media frame women political candidates and women’s support of candidates in a manner that pornifies women. In an assessment of the 2008 campaign, Anderson demonstrates how media coverage used “metaphors of pornography” and, in so doing, situated “women candidates in ways that revealed the persistence of cultural stereotypes” that “reinstantiate women citizens and leaders as vixens, sex objects, and/or nymphomaniacs.”Footnote62 Within this pornified coverage, “a sadomasochistic narrative emerges that explicitly depicts or defends sexualized violence against women as pleasurable, natural, or deserved.”Footnote63 Sheeler and Anderson explain, “Pornification highlights sexuality in contexts that otherwise are not normally sexualized and, through the use of crude humor or gender-based parody, disciplines individuals who do not conform to traditional gender norms.”Footnote64 Pornification does not require the explicitness of actual pornography, but it “connotes interpretations that are hypersexual or sexually exploitative.”Footnote65

Scholarly attention to the reduction of women to objects of desire is warranted and accurate. However, it does not capture the full scope of how women, particularly Black women, were and are disciplined when acting as women in public. Our analysis makes clear women are sexualized in two distinct ways: as objects of sexual desire and as targets of misogynoir derision. Attention to the latter is needed.

This section explores how digital misogynoir intensifies pornification, with some forms of sexualized discourse (e.g., “ho”) so entrenched that they are taken as average insults. We explore how Harris’s political authority is minimized by misogynoir, made mundane by the public woman/Black woman as prostitute trope. We detail how the nature of digital attacks on a public Black woman use algorithmic amplification to astroturf broader criticisms and intensify critiques. The key connection between these modern forms of vitriol directed at digital public woman focuses on the leverage of publicity, on appearance as such. Just as historical public women walked a tightrope of public visibility, today’s digital public women must fight against differing models of publicity that can villainize in digital modalities.

Memes and hashtags hypersexualizing Harris, and then punishing Harris on the basis of being sexual, operate as an instance of misogynoir. In her most recent book on misogynoir, Bailey describes the “Joe and the hoe” “misogynoiristic slogan” against the Biden–Harris ticket as a “ubiquitous insult.”Footnote66 We agree it is ubiquitous, synchronically replicated, and circulated. But its current power also rides on the diachronic history of non-digital replication and circulation of public-woman-as-prostitute.

These misogynoir depictions of Harris as a “ho” participate in the Jezebel trope and anchor to an origin story alleging Harris achieved her public success due to a sexual relationship with an older, powerful Black male politician. Understanding contemporary memes requires attention to the origin story and how it has circulated when and where Harris claimed space in public. To work through this argument, we first describe Harris’s political history, noting how her public-ness was called into question when the public woman and Black woman as prostitute accusations began to haunt her political origin story. We then map the operations of the memes that transmitted those accusations during the presidential campaign.

Harris’s pre-presidential political history

On November 21, 2020, Kamala Harris became “the first woman, the first Black American, and first South Asian American elected vice president in U.S. history.”Footnote67 These accomplishments added to her growing list: first Black and first woman California Attorney General, first Indian-American woman senator, and second Black woman senator. Harris’s pathway to these accomplishments began when she emerged on the political scene as a deputy prosecuting attorney of Alameda County, California, from 1990–1998 where she sought to change laws regarding sex trafficking, women’s rights, truancy, and gang violence. She was promoted to the career criminal unit of the San Francisco district attorney’s office in 1998 and earned another promotion to Chief of the Community and Neighborhood Division. In 2003 she served as head of the Children and Family Division in Oakland. She then began her campaign for San Francisco District Attorney against her former boss Terrence Hallinan in 2003 (a position for which she ran unopposed for reelection in 2007). She ran for California Attorney General in 2010 and won; she was reelected in 2014. In 2016, she ran for and won the California Senate seat. Even though this progression of positions documents a development of qualifications, Harris was dogged by claims she is promiscuous, unlearned, or generally not “fit” for public office.

It is necessary to return to Harris’s first electoral campaign to trace the roots of the Black public woman trope as it circulated about her from 2003 to the present. In 2003, Hallinan’s messaging foregrounded Harris’s presumed sexuality when it targeted Harris as a part of the city’s problem with corrupt political figures.Footnote68 Hallinan used Harris’s mid-1990s romantic relationship with San Francisco Mayor Willie BrownFootnote69 as an example of corruption, not just of city politics but of Harris herself. Campaign mailers quoted a voter saying, “I don’t care if Willie Brown is Kamala Harris’ ex-boyfriend. What bothers me is that Kamala accepted two appointments from Willie Brown to high-paying, part-time state boards – including one she had no training for – while being paid $100,000 a year as a full-time county employee.”Footnote70 The mailer did not need to reference Harris’s supposed romantic (and presumptively sexual) relationship with Brown to make the point about appointments, but the mailer did. By explicitly referencing the relationship and linking Harris to monetary payments, the mailer closed the circuit on the prostitute trope. Hallinan’s campaign depicted Harris as corrupt – not only because she received undeserved appointments but because she allegedly used her sexuality in a corrupt way. As Anderson notes: “Framing women’s political agency in terms of sexual influence is a familiar strategy, one that has shaped both ancient and contemporary narratives.”Footnote71 Even early in her career, the Jezebel trope and Harris’s potential licentiousness were used to question her political qualifications.

During the 2003 San Francisco District Attorney election campaign, criticism of Harris’s past relationship with Brown became the focus of the media narrative. In a run-off debate against Hallinan, an audience member again connected her to Brown, asking: “If elected district attorney would she operate independently from Brown’s political machine?”Footnote72 Harris answered the question by centering on Hallinan’s corruption, even suggesting she would be willing to investigate Hallinan himself for corruption. Despite the criticism, Harris won by a margin of 51 to 49 percent. Harris served as the District Attorney of San Francisco from 2004 to 2011 and would go on to be elected the Attorney General of California.

However, Kamala Harris had ambitions beyond the courtroom. When Senator Barbara Boxer announced her resignation after 20 years as a US Senator, the next week Harris announced her candidacy for the position. Harris was elected to the US Senate in 2017, and quickly became a national public figure. Harris’s performances during the 2018 Supreme Court Justice nomination hearing of Brett Kavanaugh renewed discussions of the prosecutor as a public woman. Her examination of the nominee upset then-President Donald Trump, who described Harris as “extraordinarily nasty to Kavanaugh … She was nasty to a level that was just a horrible thing the way she was.”Footnote73 “Nasty,” a favorite Trump epithet, appeals to tropes regarding assertive women as unfeminine, but also hearkens back to the idea that a woman in public is out of place, as in dirty, inappropriate, and overly sexual. In these brief examples, we see that Kamala Harris has long been plagued by derogatory and dehumanizing memes sexualizing and fetishizing her. This framing of Harris intensified during the general election campaign as she ran for the vice-presidency as Joe Biden’s running mate.

Misogynoir in the 2020 presidential campaign

In the despicable discourses directed against Harris, the anecdotal work of memes appears as mere happenstance. It just happens “Joe and the hoe” memes were popularized through tweets and platform images. It just happens the hashtag #heelsupHarris circulated on Twitter. It just happens these memes leveraged a hypersexualized version of her to diminish her political bona fides. Of course, such happenings are not simply anecdotal, but, as Benjamin insists, they are networked and made to generate meaningful public traction.Footnote74 The trope of the public woman was deployed against Harris as an act of misogynoir.

A toxic archive

To describe both algorithms and author-generated archives, Caitlin Bruce “mused the phrase” toxic archive during the RSA 2021 Rhetoric, Culture, and Technology seminar led by Adam J. Banks and Damien Smith Pfister, inspired by “work in performance studies and queer theory about archives and their limits and pains … to think about how do we learn about a past that is harmful without becoming contaminated/poisoned by it.”Footnote75 Our compilation of memes, hashtags, statements, tropes, and narratives that circulated, replicated, and mutated about Harris for the 2020 presidential campaign constitutes a toxic archive, created both by the algorithms that govern social media platforms and created by us as researchers as we document their circulations, mutations, and replications.

The term toxic archive offers much insight into how to handle collections of despicable discourse: How can our scholarship avoid being another instance of contamination? What labor is required to excavate that which seeps into the dark recesses of the internet, the digital ground on which we walk, the air we breathe, the water we drink? We make public the personal archives individual users encounter in their digital activities, hoping that a bit of sunshine can, indeed, be a powerful disinfectant. We also hope our work laying out how this toxicity has seeped into conceptions of a Black public woman provides protection against its toxic effects.

Bruce’s caution also asks for consideration of our positionality as authors. We are a collective of authors unpacking how the public woman trope became rhetorically powerful and the impacts of digital culture on the trope. We have been shaped by the same algorithms that govern social media but navigate these digital archives with some resistance to their toxicity. In these ways, we take seriously the work of rhetorical criticism to understand and undermine rhetoric’s ideological work. The risks of engaging in this work are unique for each author. Some of us have received harm or death threats because of our scholarship. Yet, even those who have not been threatened face opposition simply by naming misogynoir and highlighting how public women have been treated. All of us are public women, but have mitigated the risks of the publicity in different ways. Put simply, some of us have accepted more risk than others and that risk calculus is hemmed by misogynoir.

As we excavated the toxic technoculture created by algorithms, we created a toxic archive,Footnote76 risking recirculation and replication of the very thing that gains power through its replication and circulation. We encountered the problem of despicable discourse. This is a risk we must take. There are many connections between thin description and the curation of a toxic archive. When archiving, one amasses documents, artifacts, texts, and images, transforming the ephemeral into the enduring through an act of preservation. Moreover, with an archive, items disparately placed in space in time are collected in one place to be encountered at the same time. Creating our own toxic archive enabled us to engage with, as Benjamin earlier noted, “fields of thought and action too often disconnected.”Footnote77 We collect these acts of despicable discourse, knowing in their replication we recirculate them, but we do so as “an antidote to digital disconnection.”Footnote78 We must call to account toxic technocultures to make them visible, audible, and answerable. We must collect them to make clear they are not mere happenstance but possess rhetorical force.

Hashtags, memes, and commentary about Harris

The circulation of hashtags, memes, and commentary during the presidential campaign deployed and strengthened the misogynoir trope of Black-public-woman-as-prostitute, some by questioning how Harris ascended the political ranks and others simply by declaring her a “hoe.” Through an examination of the toxic archive of tweets, memes, and hashtags about vice-presidential candidate Harris, we can surmise what sources were the turning point in circulation after she was named Biden’s running mate on August 11, 2020.

The speed with which the Brown narrative resurfaced is noteworthy: “Within 24 hours of Ms. Harris’s campaign kickoff, some critics were bringing up her onetime relationship with a powerful California politician, Willie Brown – a common tactic faced by women that sexualizes them and reduces their successes to a relationship with a man.”Footnote79 Our analysis illustrates how social media (particularly memes and hashtags) have intensified these vitriolic, misogynoir attacks. The hashtag #HeelsUpHarris is tethered to a Facebook post by Steve Baldwin and #JoeAndTheHoe is tethered to segments from Rush Limbaugh’s radio show.

First, on August 12, 2020 (the day after Biden announced Harris would be his running mate), former California state assemblyperson Steve Baldwin posted on his personal Facebook: “Willie launched her because she was having sex with him. The idea that she is an ‘independent’ woman who worked her way up the political ladder because she worked hard is baloney. She slept her way into powerful jobs.”Footnote80 As a comprehensive analysis by Washington Post reporters detailed, the premise of the post was false; by the time Harris won her first election, her relationship with Brown had been over for 8 years. Initially, the post received little response (only 185 “likes”). Then, the post began to spread across social media posts declaring Baldwin had “exposed” Harris. In what appears to be a “behind-the-scenes coordinated effort,” right-wing blogs altered Baldwin’s post to include new content, new links, and new memes and images, which led to the emergence of #HeelsUpHarris.Footnote81 #HeelsUpHarris references to a particular sex position where the woman lays on her back, typically naked, with her legs spread and feet up in the air ready to engage in intercourse.

The week after Harris was named to the ticket, the hashtag appeared in 35,479 Twitter posts and would be seen 630,000 times on Twitter alone by October 2020.Footnote82 Researchers found false claims about Harris were circulating at a rate of 3,000 an hour.Footnote83 Although all candidates are subject to fake news, Zignal Labs found fake news about Harris was four times as prevalent than about Tim Kaine in 2016 and Mike Pence in 2020.Footnote84 Baldwin’s Facebook post led to the resurgence (and re-articulation) of gendered and racialized – misogynoir – attacks on Harris: a Black public woman was a prostitute, trading sex for political currency. The recirculation did not end with social media platforms.

Second, on August 14, 2020, shortly after Baldwin’s Facebook post, Rush Limbaugh made a series of statements on his radio show that Senator Harris slept her way to the top.Footnote85 Limbaugh accused Harris of being “a whore” and announced a nickname (that was not created by him) for the Biden/Harris presidential ticket: “Joe and the Hoe.”Footnote86 He even emphasized the spelling of “hoe” with an “e,” so it was not confused with “ghetto slang.”Footnote87 The announcement on his radio show accelerated the phrase’s circulation. The phrase “Joe and the Hoe” appeared on Twitter, blogs, and even a car dealership billboard in Massachusetts, and has since spread to bumper stickers, T-shirts, clothing patches, flags, and yard signs.Footnote88 A message or slogan moving across platforms is not novel, but the hashtag of #JoeAndTheHoe operated distinctly through its ability to link conversations and simultaneously create a toxic archive through algorithms.

We now turn to explore how these two initial statements stuck through the circulation of memes and hashtags. “Hoe” as a visual and verbal meme stuck, in part, because it recirculated the same accusation embedded within historical conflations of public woman in general, and Black woman in particular, with prostitute and that were hurled during Harris’s first electoral campaign in 2003. False content sites and memes recirculated the accusation Harris had gained prominence in California politics because of her relationship with Brown. Consider these anecdotes: social media posts and reactionary news outlets declared Harris “started out her career as Willie Brown’s Bratwurst Bun,”Footnote89 “slept her way to the position she’s in now,”Footnote90 was “CamelToe Harris,”Footnote91 and (echoing Don Imus’s misogynoir comment about Rutgers’s women basketball players) was a “Nappy headed hoe.”Footnote92 One asked: “Who Says You Can’t Still Sleep Your Way To The Top?”Footnote93 These misogynoir internet accusations circulated offline as well. At a rally on August 28, 2020, Trump said, “You know, I want to see the first woman president also, but I don’t want to see a woman president get into that position the way she’d do it – and she’s not competent. She’s not competent.”Footnote94 On September 21, 2020, Representative Matt Gaetz declared, “Kamala Harris moved up in California politics because she was dating Willie Brown.”Footnote95

These anecdotes quite grotesquely portray the relationship between Harris and Brown as quid pro quo. In October 2020, actor James Woods (with 2.6 million Twitter followers) described Harris as a “smug former courtesan” who “started on her knees.”Footnote96 A Reddit meme showed Harris and Brown speaking (a photo from a long-ago campaign event), with Brown telling Harris she could have a $72,000 job if she was “happy to see” the “banana in his pocket.”Footnote97 Still other circulations were far more grotesque, with YouTube content highlighting how Harris would “fuck and suck” Brown’s “Big Black Dick” to get her “Ho Ass a job.”Footnote98 These digital memes replicated, circulated, and mutated the non-digital memes of Black woman as whore/ho, public-woman-as-prostitute, and the Jezebel trope. The memes declared Harris to be a “whore” and “ho” possessing a “deviant Black female sexuality” characterized by being “sexually aggressive.” She was a sexual servant, ready to please those who would help her attain political prominence. Women’s exhibition of political ambition has long been perceived as deviant.Footnote99 Here, political deviance was equated to sexual deviance, conflated in the public woman of Kamala Harris.

References to fellatio are ubiquitous. Examples included: a meme showing Harris performing fellatio on the J in a Joe 2020 campaign logo,Footnote100 tweets declaring “YOU LOOK BETTER QITH[sic] YOUR MOUTH SHUT”Footnote101 and asking “Is it ok for a black woman to suck dicks to become a VP?” On Etsy, you can buy clothing patches that declare “Biden sucks” and “Harris blows.” Others referenced Harris being French as how “she got her career off the ground” (“French treatment” being a reference to fellatioFootnote102), and a meme and hashtag #Banana say “to mouth Kamala, it will be hard for you, but #Practice makes perfect.”Footnote103 A meme described the Democratic ticket as “pee pads and knee pads.”Footnote104 A Harris faux action figure’s box declared, “WILL SUCK COCK FOR A JOB.” In Massachusetts, an auto business erected a sign announcing the “Joe and the Hoe sniff and blow tour.”Footnote105

These slurs persisted into 2022. After the Kentucky Derby, stories circulated reporting the winning horse’s trainer responded to a Sebastian Gorka query on January 12 “So what exactly are Kamala’s qualifications?” with the answer “Heard she’s good on her knees!!”Footnote106 It is no accident that characterizations of Harris as a “hoe” exhibit an obsession with fellatio, as public women are presumed to be those who would perform sexual acts others would not. More pointedly, Catharine A. MacKinnon, in critiquing pornography, asked: “Even if she can form words, who listens to a woman with a penis in her mouth?”Footnote107

These connections possess a misogynoir inflection when applied to Harris. Harris, as a Black public woman, is silenced by a symbolic dick in her mouth. She is positioned on her knees (a servant) and as someone who would perform (deviant) sexual practices that other (white) women would ostensibly not, and as someone who gives pleasure not in return for her own but in return for payment (a hoe). Such memes manifest both a sexual desire and a desire to deride Harris, to turn her into a person who is literally brought to her knees. As Bailey wrote, this form of misogynoir “describes the uniquely co-constitutive racialized and sexist violence that befalls Black women as a result of their … interlocking oppression at the intersection of racial and gender marginalization.”Footnote108 These memes invigorate the general historic tropes as they are leveraged against Harris in her particularity.

The use of memes to contain Harris illustrates the extent to which the desire of misogynoir retains its perverse rhetorical outcomes. Memetic fixation on Harris and oral sex is not simply sexist discourse, but also minimizes Harris to deviant sexuality, maximizes Harris’s publicness as sexual and not political, and describes her presence in the public as an unabashed attempt to follow her ambitions. As Caitlin Lawson has shown in an analysis of the misogynoir directed against Leslie Jones, current far-right individuals’ toxic messaging recirculates whenever opportunity strikes.Footnote109 Those toxic messages are acutely leveraged against Black women as public figures precisely because of their success. These individuals insist on creating pornographic and scornful remarks. But, beyond the creation of these memes and hashtags, the virulent manner in which they spread marks the ways memetic replication, circulation, and mutation are used to punish Black women for existing in public, for daring to speak on issues of broader concern, or for publicizing themselves at all.

The circulation of claims identifying Harris as a public woman entrench the rubrics through which such figures are understood. Harris becomes diminished in her authority and accomplishments through toxic claims that can only read her as deviant. Tressie McMillan Cottom, writing for Harper’s Bazaar, put a fine point on the issue: “From health care to celebrity, our culture’s ideas about what constitutes a body worthy of being in public has one imperative: Protect the idea of white bodies at all costs.”Footnote110 Harris is used to uphold the unstated normality of whiteness as it relates to public political figures. Far from simply imagining the sexualized acts Harris would perform, the larger rhetorical goal is to consume her, to render her nothing more than a fantasy for projections of a false white superiority.

As is true of memetic invention, these efforts ebb and flow in relationship to spectacular or noteworthy media events. As Harris announced her run for the presidency, became Biden’s vice-presidential running mate, or debated against Vice President Pence, her public presence was met with memes that replicated, circulated, and mutated the centuries-old meme of Black-public-woman-as-prostitute to mock her skills and diminish her authority. In these instances, a political woman like Kamala Harris was transformed into a public woman of old, available for caricature as a public sexualized figure rather than as a public political figure. The mechanics of digital culture, particularly hashtags, intensify and expedite this effect. As hashtags channel the analog and digital memes we detailed earlier, they operate at different levels of valence. Hashtags are not a mere replication and circulation; hashtags are also an amplification as they do the work of generating a toxic archive for consumption (rather than for analysis).

When a Twitter user decides to follow a hashtag, they typically post and receive messages that utilize the hashtag from accounts outside of the accounts they already follow.Footnote111 With the mere click of a button, users have access to a larger audience by providing a mechanism to access and constitute circulating discourses of fellow Twitter users who are engaging in these misogynoir depictions. From there, Twitter’s algorithm populates Twitter users’ timeline with similar conversations based on hashtags used in conjunction with #JoeAndTheHoe (such as #HeelsUpHarris, #HeadBoardHarris, #KamalaToeHarris, etc.). Thus, not only are hashtags linking separate individual conversations across accounts, but they also craft (and expose) the Twitter user to a toxic archive and, because it is created online, it is much quicker at disseminating information than non-digital modalities.

Beyond the hashtag’s ability to index a toxic archive, #JoeAndTheHoe serves as a linking mechanism between the analog misogynoir against the Black public woman and the digital traces of misogynoir commentary on Harris’s early political career, while simultaneously crafting new vitriolic digital trails to discredit and demean her current accomplishments and political ideas. Without #JoeAndTheHoe, it is unlikely the average Twitter user would have knowledge of the previous commentary falsely questioning how Harris ascended the political ranks. The hashtag connects analog and digital traces of previous misogynoir sentiments, focuses misogynoir against Harris, and provides a shorthand commentary to express dismay at the policy choices being made by Harris (and the Biden administration) long after the campaign. Ongoing digital circulation of #JoeAndTheHoe enables Twitter users to tie together current online efforts to discredit Vice President Harris’s policy initiatives. The toxic archive showcases how the proliferation of hashtags and memes that sexualized Harris sought to discredit her previous political accomplishments, prevent her success in the 2020 U.S. Presidential election, and (after the 2020 Presidential election) to demean her present political actions.

Hashtags also enable Twitter users to feel a sense of creative agency even as they collaborate to build a toxic archive. The stickiness of the hashtag is enabled because, even in its uniqueness, it is still tethered to centuries of shorthand and tropes about the Black public woman. Hashtags can widely circulate misogyny and gendered vitriol due to the inherent design of hashtags themselves. The end result is hashtags facilitate a “broader digital circulation of misogyny, violent threats, and gendered vitriol that is typically directed towards women through online platforms.”Footnote112 Hashtags curate a toxic archive.

These digital interactions continue to circulate. On February 11, 2022, a former Republican podcaster posted an image on Twitter of a sticker seen on a car in New York City. The “Joe and the Hoe” campaign slogan was no longer alone; now it was topped with the word “Fuck” written in assault rifles so the sticker read “Fuck Joe and the Hoe.” Other Twitter users highlighted where they had seen similar stickers in Florida, Texas, California, and Georgia (authors of this paper have seen the bumper sticker in Texas, Illinois, and Iowa). Digital misogynoir against Black women such as Harris demonstrate such vitriol is not limited to the internet, but circulates in and among the world, generating even more cult-like devotion to violence. “Joe and the Hoe” is not simply a bland meme or hashtag that harasses Harris. It is a warrant for continued violence against the Black public woman.

Momala and tropes of Black womanhood

In contrast to these memes and hashtags, popular news outlets and late-night comedy shows projected a mammified persona of Harris; she was heralded as a caregiver to others’ children as she donned the mantle of Momala.Footnote113 News articles and interviews focused on how her stepchildren refer to her as “Momala,”Footnote114 and Saturday Night Live had sketches about Harris being the “funt” (i.e., fun aunt).Footnote115 Harris settling into the role of Momala could be an example of the “modern mammy” or “Black lady” frame, which “is designed to counter claims of Black women’s promiscuity.”Footnote116 In the political sphere, the “modern mammy” is understood to symbolize the “dominant group’s perceptions of the ideal Black female relationship to elite White male power.”Footnote117 Even in the process of selecting Harris as the Vice President, efforts were made to show Harris “fronting a softer and smitten persona.”Footnote118 Displaying Harris’s bubbly personality on the campaign trail made her more “likable,”Footnote119 while also working to “ameliorate any concerns about Harris fulfilling the ‘myth’ of an ‘angry black woman’.”Footnote120 The attempts to make Harris more likable mirrored the “media makeover” First Lady Michelle Obama was given to craft “a new Michelle, carefully edited for public consumption.”Footnote121

Harris’s deployment of Momala and embrace of her political agency as a prosecutor with Copmala given her time as AG demonstrate her capacity as a public Black woman, even as they may reinforce aspects of other tropes. Our analysis of the toxic archive is not meant to imply Harris was without agency or that there is no way out of the toxic cesspool. Catherine Knight Steele argues whenever tropes are used, there is still agency in that trope:

[E]ven in the deplorable stereotypes meant to mock and marginalize Black women, the mammy and jezebel demonstrate the capacity of Black women. Black women were caretakers who ran households, crafted medicinal cures for ailments, delivered babies, fashioned devices used to feed, clothe, and provide sustenance to their own families and families in their care.Footnote122

Conclusion

This essay leaves rhetorical scholars with a range of questions. What possibilities are there for public woman as a woman who has a place in public? Can public woman serve as a resource, practice, or figure that makes intelligible women’s many public roles? Where might one turn in the search for less constrained and constraining ideologies of women in public that better illuminate the dialectics of subjectivity that affect women in public? How might we make public woman intelligible as a woman in public? What can correct the misrecognition of public woman in general and of Black public woman in particular?

First, scholars must continue to complicate the intersecting racialization and sexualization of the public woman. Political theorists like Cathy Cohen, Melissa Harris-Perry, and Christina Greer have identified the nuanced ways Blackness is manifest on the political. Black women in the political sphere are constantly contending with “derogatory assumptions about their character and identity.”Footnote123 However, instead of condemning Black women’s actions in the public sphere for not conforming to respectability politics, it is important to note the structural constraints they experience as they stand in what Perry calls the “crooked room” that creates “warped images of their humanity.”Footnote124 bell hooks asserted that to grapple with these harmful perceptions of Black women and “step toward liberation and equality,” the first critical step is “challenging white people’s assumptions about what they see when they view Black people.”Footnote125 As rhetorical scholars, we can challenge these assumptions by revealing the walls of the “crooked room” in which Black women in public must operate. Beyond challenging white people’s assumptions about Black people, we see promise in the emerging Black women collectives dismantling the crooked room that currently constrains Black women in the political sphere. For example, the contemporary M4BL (Movement for Black Lives) was started by queer, Black millennial women. This organization is “unapologetically Black, intersectional, and rejects respectability politics”Footnote126 and seeks to “win rights, recognition, and resources for Black people”Footnote127 through social and political activism.

Second, though the phrase public woman carries similar valences in other cultures and languages (e.g., Danish’s offentlig kvinde), some countries have developed the sensemaking apparatus available for understanding women in public and see women rise to national leadership (e.g., Denmark’s Prime Ministers Helle Thorning-Schmid and Mette Frederiksen). Exploring how other countries have created a sense of public subjectivity for women, particularly among women with other marginalized identities, might offer pathways for the United States. Concomitantly, other countries also struggle with constructing a conception of public woman that foregrounds agency rather than sexualization. Comparative studies would be of use.

Finally, we reiterate our point from the beginning of the essay. At the same time a delinkage of public woman from prostitution is needed so, too, is a full-throated defense of prostitutes as having a place in public in all its forms, economic and political. As long as sexuality is used to discredit women, being a public woman will remain fraught. Thus, the challenge is not just to find resources, practices, and figures for public woman. The challenge is also to destigmatize the sexual woman.

Today’s digital public woman faces a daunting set of constraints against being a rhetorical figure, whether performing, speaking, tweeting, writing, or running for public office. Our point is not just women candidates are treated as sex objects, but that public women are equated with prurience, particularly Black public women, and that equation functions as a disqualifying force. Patricia Hill Collins relates this to the “politics of respectability” whereby Black women must adhere to standards of white femininity or be deemed deviant. Black public women are framed as “‘hos’ who trade sexual favors for jobs, money, drugs, and other material items” or a “female hustler … who is willing to sell, rent, or use her sexuality to get whatever she wants.”Footnote128 The labeling of a woman as a public woman is not to assess them on the basis of their attractiveness and sexual appeal but is to declare them a bad (immoral) woman and a bad (unqualified) candidate.

Positioning Kamala Harris as a ho is not just ad hominem; it is a particularly pernicious deployment of misogynoir tropes supercharged diachronically by the equation of public woman in general and Black woman in particular with prostitute and supercharged synchronically by the replication and circulation on social media, intensified by hashtags’ ability to compile a toxic archive and make the misogynoir seem normal, common, just a happenstance. The public woman trope is uniquely harmful when leveraged against Black women. This trope works to depict women (particularly Black women) candidates as unfit for office, and ultimately leads to the normalization and acceptance of violence towards Black women who dare to run for public office. Misogynoir as a mode of rhetorical attack both constrains Harris’s authority and ensures white supremacist violence remains an ambient threat.

The public-woman-as-prostitute trope and current memes that recirculate it allows that trope to operate with significant intensity and stickiness for women who are marked by difference. Informed by Benjamin’s understanding of “thinness,” the elasticity of attacks on a Black public woman makes clear the “fragility” at stake in such pronouncements. Attacks against public women are not universal, but instead, directed through select rhetorical forms that may appear as mere anecdote. The forms are mercurial, shifting their shapes and disguising themselves as humor, or play, or satire, or just a share of a friend’s post.Footnote129 Yet, the trope is another way to sexualize and racialize the people to whom it is applied. As the trope skims across surfaces, it sticks to them, directing public gazes to see and judge. What this essay makes clear, though, is the rhetorical labor we must do. We (as scholars, as a society, as a people) cannot have full acceptance of women as public officials until we have reckoned with the linkage between public woman and women in public. We cannot honor, witness, and recognize Black women as public figures until we have reckoned with the conflation of Black women and prostitution in the rhetoric of political campaigns.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 As cited in Utkarsh Bhatla, “NBA Fires Photographer Bill Baptist over Offensive Meme on Kamala Harris,” The Sports Rush, August 15, 2020, https://thesportsrush.com/nba-news-nba-fires-photographer-bill-baptist-over-offensive-meme-on-kamala-harris/.

2 Mary Stuckey, “Arguing Sideways: The 1491s’ ‘I’m an Indian Too,’” in Disturbing Argument, ed. Catherine H. Palczewski (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2014), 75–80, 76, 79.

3 We nod here to the approach used by McGee on ideographs and the argument that analysis of them requires both a synchronic and diachronic orientation. Michael C. McGee, “The ‘Ideograph’: A Link Between Rhetoric and Ideology,” Quarterly Journal of Speech, 66, no. 1 (February 1980), 1–16.

4 Stephanie Madden et al., “Mediated Misogynoir: Intersecting Race and Gender in Online Harassment,” in Mediating Misogyny: Gender, Technology, and Harassment, ed. Jacqueline Ryan Vickery and Tracy Everbach (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018), 71–90, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72917-6_4.

5 Ruja Benjamin, Race after Technology (New York: Polity, 2019), 45.

6 Benjamin, Race after Technology, 45, 46.

7 Benjamin, Race after Technology, 46.

8 Memes are characterized by these three actions. See Eric S. Jenkins, “The Modes of Visual Rhetoric: Circulating Memes as Expressions,” Quarterly Journal of Speech, 100, no. 4 (November 2014), 442–66; Davi Johnson, “Mapping the Meme: A Geographical Approach to Materialist Rhetorical Criticism,” Communication and Critical Cultural Studies, 4, no. 1 (March 2007), 27–50; Michele Kennerly and Damien Smith Pfister, Ancient Rhetorics and Digital Networks (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2018).

9 See Carolyn Eastman, A Nation of Speechifiers: Making an American Public after the Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009); Glenna Matthews, The Rise of Public Woman: Woman’s Power and Woman’s Place in the United States 1630–1970 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992); Alison Piepmeier, Out in Public: Configurations of Women’s Bodies in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2004); Mary P. Ryan, Women in Public: Between Banners and Ballots, 1825–1880 (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990).

10 Chandra Talpede Mohanty, Feminism without Borders (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 55.

11 Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (New York: Routledge, 2000), 81.

12 Jacqueline Jones Royster, Traces of a Stream: Literacy and Social Change Among African American Women. (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000), 109.

13 Ryan, Women in Public, 3.

14 Ryan, Women in Public, 4.

15 James B. Jones, “Municipal Vice: The Management of Prostitution in Tennessee’s Urban Experience. Part I: The Experience of Nashville and Memphis, 1854–1917,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, 50, no. 1 (Spring 1991), 33–41, 34.

16 Sarah Handley-Cousins, “Prostitutes!” National Museum of Civil War Medicine, February 15, 2017, http://www.civilwarmed.org/prostitutes/; William Moss Wilson, “The Nashville Experiment,” New York Times, December 5, 2013, https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/12/05/the-nashville-experiment/.

17 William Moss Wilson, “The Nashville Experiment,” New York Times, Opinionator blogs, December 5, 2013, https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/12/05/the-nashville-experiment/.

18 Sander L. Gilman, “Black Bodies, White Bodies: Toward an Iconography of Female Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-Century Art, Medicine, and Literature,” Critical Inquiry, 12, no. 1 (Autumn 1985), 204–42, 206, 229.

19 Evelynn M. Hammonds, “Toward a Genealogy of Black Female Sexuality: The Problematic of Silence,” in Feminist Genealogies, Colonial legacies, Democratic Futures, ed. M. Jacqui Alexander and Chandra Talpade Mohanty, 170–82 (New York: Routledge, 1997), 173.

20 Paula Giddings, “The Last Taboo,” in Race-ing Justice, En-gender-ing Power, ed. Toni Morrison, 441–63 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1992), 450.

21 John W. Jacks quoted in Shirley Wilson Logan, With Pen and Voice: A Critical Anthology of Nineteenth-Century African-American Women (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1995), 120. Jno. W. Jacks, letter to Florence Balgarnie, March 19, 1895, https://rwklose.files.wordpress.com/2021/03/jacks-letter.jpg.

22 Matthews, The Rise of Public Woman, 3.

23 “The Liberation of Lizzie Schauer,” New York Journal (December 10, 1895) cited in endnote 48 in Karen Roggenkamp, Narrating the News: New Journalism and Literary Genre in Late Nineteenth-Century American Newspapers and Fiction (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2005). Matthews cites the New York World as the crusading paper. See also the role of the New York World in Richard Zacks, Island of Vice: Theodore Roosevelt's Quest to Clean Up Sin-Loving New York (New York: Anchor, 2012), 188–91.

24 Matthews, The Rise of Public Woman, 3.

25 Katie Robertson, “News Media Can’t Shake ‘Missing White Woman Syndrome,’ Critics Say, New York Times, September 30, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/22/business/media/gabby-petito-missing-white-woman-syndrome.html?action=click&pgtype=Article&state=default&module=styln-petito&variant=1_show®ion=MAIN_CONTENT_1&context=STYLN_TOP_LINKS_recirc.

26 Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2019), 218, 224.

27 Hartman, Wayward Lives, 221.

28 Hartman, Wayward Lives, 241.

29 Although typically referred to as “Ain’t I a Woman,” Campbell makes a compelling case that Frances Dana Gage used “the argot of blackface minstrel shows” and “racist caricatures” when they published a version of the speech 12 years after it was delivered, likely attributing to Truth an idiom unlikely to have actually been used by Truth. Karlyn Kohrs Campbell, “Agency: Promiscuous and Protean,” Communication & Critical/Cultural Studies, 2, no. 1 (2005), 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/1479142042000332134. See also Roseann M. Mandziuk, “‘Grotesque and Ludicrous, but Yet Inspiring’: Depictions of Sojourner Truth and Rhetorics of Domination,” Quarterly Journal of Speech, 100, no. 4 (2014), 467–487, https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630.2014.989896; Roseann M. Mandziuk and Suzzane Pullon Fitch, “The Rhetorical Construction of Sojourner Truth,” Southern Communication Journal, 66, no. 2 (2001), 120–37, https://doi.org/10.1080/10417940109373192.

30 See Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (New York: Routledge, 2000).

31 Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought, 81.

32 Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought, 81.

33 Mireille Miller-Young. A Taste for Brown Sugar: Black Women in Pornography (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 144.

34 Miller-Young, A Taste, 144.

35 Shanara R. Reid Brinkley. “The Essence of Res(ex)pectability: Black Women’s Negotiation of Black Femininity in Rap Music and Music Video,” Meridians, 8, no. 1 (2008), 236–60, 246.

36 Reid-Brinkley, “The Essence,” 244.

37 Miller-Young, A Taste, 145.

38 Miller-Young, A Taste, 145.

39 Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Feminism without Borders (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 55.

40 Barbara Welter, Dimity Convictions: The American Woman in the Nineteenth Century (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1976).

41 Amy Brandzel, Against Citizenship: The Violence of the Normative (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2016), 15.

42 Moya Bailey and Trudy, “On Misogynoir: Citation, Erasure, and Plagiarism,” Feminist Media Studies 18, no. 4 (2018): 762–68, https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1447395; Moya Bailey, Misogynoir Transformed (New York: New York University Press, 2021).

43 Bailey, Misogynoir Transformed, 1.

44 Bailey, Misogynoir Transformed, 2.

45 Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought; bell hooks, Ain’t I a Woman (Boston: South End Press, 1981).

46 Joan Morgan, When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: A Hip-Hop Feminist Breaks It Down (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000); Brittney C. Cooper, Susana M. Morris, and Robin M. Boylorn, The Crunk Feminist Collective (New York: The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2017); Treva B. Lindsey, “Let Me Blow Your Mind: Hip Hop Feminist Futures in Theory and Praxis,” Urban Education, 50, no. 1 (January 2015), 52–77, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085914563184.

47 Catherine Knight Steele, Digital Black Feminism (New York: New York University Press, 2021).

48 Our understanding of the rhetorical power of memes is influenced by Heather Suzanne Woods and Leslie A. Hahner’s Make America Meme Again: The Rhetoric of the Alt-Right (New York: Peter Lang, 2017).

49 Bailey, Misogynoir Transformed, 1.

50 Kishonna Gray, Intersectional Tech: Black Users in Digital Gaming (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2020), 111.

51 Gray, Intersectional Tech, 90.

52 Bailey and Trudy, “On Misogynoir,” 763.

53 Katy Steinmetz, “How Your Brain Tricks You into Believing Fake News,” Time, August 9, 2018, http://time.com/5362183/the-real-fake-news-crisis/.

54 Amy Mitchell, Mark Jurkowitz, J. Baxter Oliphant, and Elisa Shearer, “Americans Who Mainly Get Their News on Social Media Are Less Engaged, Less Knowledgeable,” Pew Research Center, July 30, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2020/07/30/americans-who-mainly-get-their-news-on-social-media-are-less-engaged-less-knowledgeable/.

55 Alice E. Marwick and Robyn Caplan, “Drinking Male Tears: Language, the Manosphere, and Networked Harassment,” Feminist Media Studies, 18, no. 4 (2018), 543–59, https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1450568; Adrienne Massanari, “#Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s Algorithm, Governance, and Culture Support Toxic Technocultures,” New Media & Society, 19, no. 3 (2017), 329–46, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807.

56 Karlyn Kohrs Campbell, “The Discursive Performance of Femininity: Hating Hillary,” Rhetoric and Public Affairs, 1, no. 1 (1998), 1–19; Kristina Horn Sheeler, “Marginalizing Metaphors of the Feminine, in Navigating Boundaries: The Rhetoric of Women Governors, ed. Brenda DeVore Marshall and Molly A. Mayhead (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000), 15–30.

57 Tyler G. Okimoto and Victoria L. Brescoll, “The Price of Power: Power-Seeking and Backlash against Female Politicians,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, no. 7 (2010), 923–36.

58 Catherine H. Palczewski, “The Male Madonna and the Feminine Uncle Sam: Visual Argument, Icons, and Ideographs in 1909 Anti-Woman Suffrage Postcards,” The Quarterly Journal of Speech, 91, no. 4 (November 2005), 365–94.

59 Caroline Heldman, Susan J. Carroll, and Stephanie Olson, “‘She Brought Only a Skirt’: Print Media Coverage of Elizabeth Dole’s Bid for the Republican Presidential Nomination,” Political Communication, 22 (2015), 315–35;