ABSTRACT

The concept of ‘Inclusive Growth’ – a concern with the pace and pattern of growth – has become a new mantra in local economic development. Despite enthusiasm from some policy-makers, others argue it is a buzzword which is changing little. This paper summarizes and critiques this agenda. There are important unresolved issues with the concept of Inclusive Growth, which is conceptually fuzzy and operationally problematic, has only a limited evidence base, and reflects an overconfidence in local government’s ability to create or shape growth. Yet, while imperfect, an Inclusive Growth model is better than one which simply ignores distributional concerns.

KEYWORDS:

INTRODUCTION

when you ask five economists to define the concept [of Inclusive Growth], you will likely end up with six answers.

(Durán, Citation2015, n.p.)

Inclusive Growth is fast becoming a new mantra in urban and regional policy. Its popularity has been driven, in large part, by two linked trends. The first is widespread concern about the scale and consequences of inequality (Cavanaugh & Breau, Citation2017). Global inequality has probably fallen over the past 30 years, mainly due to progress in China. But inequality within countries has tended to increase, with incomes rising for the already affluent while living standards stagnate for much of the population (Benner & Pastor, Citation2015; The Resolution Foundation, Citation2014; Summers & Balls, Citation2015). For example, the average male full-time worker in the United States earned less in real terms in 2014 than in 1973 (Wessel, Citation2015); real pay levels in the UK fell between 2009 and the start of 2015 (Clarke & D’Arcy, Citation2016); and even egalitarian Sweden has seen long-term increases in inequality (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2011). Some have argued that growing inequality was one cause of populist victories such as the UK referendum on the European Union or Donald Trump’s election as US president (Gordon, Citation2018; Lee, Morris, & Kemeny, Citation2018; Shearer & Berube, Citation2017).

The second trend is the growing economic and political importance of cities. Cities are increasingly seen as significant economic and political actors (Harrison, Citation2012; Ianchovichina, Lundstrom, & Garrido, Citation2009; Storper, Citation2013). They are often where inequalities are starkest and clearest, and their political importance is increasing, with local government given new powers and responsibilities to drive economic growth (Rodríguez-Pose & Gill, Citation2003). But while cities are now seen as ‘drivers of growth’, this growth is not shared equally. Instead, the most successful cities are often the most unequal (Glaeser, Resseger, & Tobio, Citation2009; Lee, Sissons, & Jones, Citation2016), with growth failing to trickle down to the poorest (Lee & Sissons, Citation2016; Lupton, Rafferty, & Hughes, Citation2016). This has led policy-makers to question how they can ensure the benefits of growth are more widely shared.

In this context, Inclusive Growth has become one of the most fashionable concepts in urban and regional policy. It can be defined, loosely, as a concern with both the pace and pattern of growth. It became popular with economic development policy-makers in the Global South in the late 2000s and is incorporated into the Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, Citation2016). But following an initial interest from national policy-makers in the Global South, there has been a wave of interest from urban policy-makers internationally. In 2016, the OECD (Citation2016, p. 1) launched an ‘Inclusive Growth in Cities’ programme, with ‘champion mayors’ signed up to show their commitment to ‘tackling inequalities and promoting more inclusive economic growth in cities’. The World Bank (Citation2017, p. 1) has argued for a focus on ‘Inclusive Urbanisation’ for ‘Inclusive Growth’. Perhaps most importantly, the concept was used in the New Urban Agenda which argued that economic development should be achieved in a way that achieved opportunity for all, because ‘private business activity, investment and innovation are major drivers of productivity, inclusive growth and job creation’ (United Nations, Citation2016, p. 33).

The Inclusive Growth agenda has been taken up with particular enthusiasm in the UK. Since the crisis of 2007–08, employment rates have been strong, but many of the new jobs have been in low-paid self-employment or temporary work (Green & Livanos, Citation2015) and wage growth has been weak (Clarke & D’Arcy, Citation2016). At the same time, a series of city deals were agreed as part of a rhetorical ‘devolution revolution’ (Ayres, Flinders, & Sandford, Citation2018; Tomaney, Citation2016), and the idea that cities should encourage Inclusive Growth has become a new orthodoxy. There have been a series of high-profile reports published and research centres launched, including the final report of the Inclusive Growth Commission of the Royal Society of Arts (RSA), a series of practice focused reports by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) (e.g., Crisp et al., Citation2017; Green, Kispeter, Sissons, & Froy, Citation2017; Pike, Lee, MacKinnon, Kempton, & Iddawela, Citation2017) and an influential new research centre – the Inclusive Growth Analysis Unit (IGAU) – established at the University of Manchester. The term has influenced policy: ‘Inclusive Growth’ is one of the Scottish government’s goals in its Agenda for Cities (Scottish Government, Citation2015), and cities such as Leeds have introduced Inclusive Growth strategies (Leeds City Council, Citation2017).

Yet, despite significant policy interest, there has been little critical analysis of the Inclusive Growth-in-cities agenda. One exception is Turok (Citation2010), but this predates the current enthusiasm. The agenda is underpinned by good intentions, and this has perhaps meant little critique. But widespread use of the term ‘Inclusive Growth’ raises an important question: is Inclusive Growth a genuinely useful concept for economic development, or a buzzword, offering policy-makers the promise of addressing two major problems – inequality and low growth – simultaneously, but achieving little? This paper summarizes and critically reviews the emerging work in this area. It investigates the concept of Inclusive Growth, consider its strengths and limitations, and in doing so consider ways in which the concept might be best operationalized. While the scope of the paper is global, it draws on examples from the UK, where the agenda has been enthusiastically but uncritically adopted.

This paper is sympathetic to the overall concept of Inclusive Growth, which represents an important, clever and overdue attempt to link economic development to distribution. However, it argues that Inclusive Growth remains a fuzzy concept which is often vaguely and inconsistently defined and is rapidly becoming a buzzword used to signal progressive intent but with relatively little evidence, to date, of actual implementation. When applied to cities, it represents an overconfidence in the ability of local government to stimulate growth, let alone shape it, and there is still little evidence on what works. Cities have an important role to play in Inclusive Growth but, given their relatively limited powers and resources in many places, national government still needs to play a leading role. Inclusive Growth is a potentially important agenda, but the challenge will be delivery.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section provides a brief history of the concept and its roots in the development policy literature. The third section considers various definitions and suggests that ‘Inclusive Growth’ can be considered a concept, a policy agenda but also a buzzword. The fourth section develops a critique of the concept based on its fuzziness, the challenges in operationalizing it and the problems of a policy agenda which offers to solve two very difficult problems simultaneously. The fifth section concludes with an evaluation of the concept, and the argument that while it is not perfect, Inclusive Growth is certainly an improvement on a narrow focus on growth alone.

THE ROOTS OF INCLUSIVE GROWTH

There is, of course, a long history of debate about the relationship between growth and the income distribution. The dominant theoretical model has been the Kuznets (Citation1955) curve. This suggests that inequality initially increases with development as structural change creates new, well-paid jobs for a few workers; later, inequality falls as more workers enter well-paid sectors and wages in other sectors catch up. This model – in which inequality is simply a side-effect of the level of development – was associated with the trickle-down idea of development and a view that growth is the first step in poverty reduction (Kanbur, Citation2000; Kakwani & Pernia, Citation2000). Yet, the basic insight of the Kuznets curve seemed inconsistent with the results of studies on the determinants of inequality (Kanbur, Citation2000; Yin, Citation2004) and has been replaced with the more nuanced idea that development could be achieved in different ways and with different income distributions (Ranieri & Ramos, Citation2013). As Yin (Citation2004) notes, growing inequality is not inevitable but the result of policy choices made as part of national development strategies.

More recently, there has been concern that economic growth was simply increasing inequality, without benefiting those on low incomes. In particular, Piketty’s (Citation2014) seminal work highlighted long-term growth in inequality, determined by the balance between returns to capital and the growth rate. According to Piketty, low growth would lead to growing inequality as gains to capital earners outstripped those of labour. This story seems consistent with the experience of many advanced economies. For example, according to estimates by the Brookings Institution, in the United States the average male full-time worker earned less in 2014 than in 1973, a wage stagnation disguised in national averages by significant growth for top earners (Wessel, Citation2015). In the UK, income inequality has fallen since the 2008 recession, but it remains relatively unequal by OECD standards and inequality is expected to increase over the long-term (Hood & Waters, Citation2017; OECD, Citation2011).

The literature on the distributional impact of growth shows that while growth can benefit those on low incomes, this is not inevitable (Ravallion, Citation2015). Instead, the growth–poverty relationship is dependent on the nature of growth, in terms of its sectoral structure, and local context, such as initial inequality (Ferreira, Leite, & Ravallion Citation2010). This recognition that different types of ‘growth’ may have different implications for poverty and the income structure led to new concepts that sought to link growth with distribution. In 1974, the World Bank published an influential study Redistribution with Growth (Chenery, Ahluwalia, Duloy, Bell, & Jolly, Citation1974) that made the case for distributional considerations to be made more prominent in economic development policies. It suggested that rather than assuming increased incomes were of equal value in the economy, as does gross domestic product (GDP), instead ‘distributional weights’ should be used to reflect the greater utility of increased income for those on low incomes.

The most significant concept in these debates was ‘Pro-Poor Growth’, defined as the difference between the poverty reduction associated with any particular growth spell and the poverty reduction had growth been equally distributed (Kakwani & Pernia, Citation2000). The literature on Pro-Poor Growth had two goals: one technical, of developing new indicators to focus policy on poverty reduction; one economic, as a reaction to Washington Consensus policies which were seen as having increased inequality, with little impact on poverty (Grimm, Sipangule, Thiele, & Wiebelt, Citation2015; O’Connell, Citation2014). Pro-Poor Growth represented a way of refocusing policy to ensure that the poor gained, but without losing the focus on growth which most saw as necessary. The concept gained in popularity through the late 1990s until, in 2004, Ravallion (Citation2004, p. 1) noted that ‘almost everyone in the development community is talking about “Pro-Poor Growth’”.

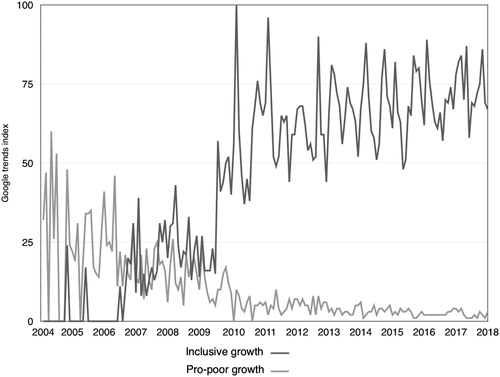

Yet, despite its popularity, there were some important critiques of the idea of Pro-Poor Growth. Multiple definitions used by different actors made it hard to track its implementation: academics talked about it in precise, statistical terms, but policy-makers often had a different set of concepts in mind (Lopez, Citation2004). It was also relatively narrow, and the focus on poverty meant those just above the poverty line were ignored. In the late 2000s it was replaced by a new concept, ‘Inclusive Growth’, as the dominant term in international development (Grimm et al., Citation2015). To show this switch, shows Google Trends search data – a rough measure of interest – for ‘Inclusive Growth’ and ‘Pro-Poor Growth’. In around 2004 – when Ravallion suggested interest had peaked – Pro-Poor Growth started to wane, with Inclusive Growth taking its place. The latter concept spread quickly from the Global South to the Global North, and then from national governments to cities and regions. This reflected a general quickening of the spreading of policy concepts related to poverty, with Peck (Citation2011, p. 167) noting that the geographies of anti-poverty policy became ‘jumbled up as never before’.

DEFINING ‘INCLUSIVE GROWTH’

Unsurprisingly, given the range of actors who use the term, there is no universal definition of Inclusive Growth. In an early definition, The World Bank (Ianchovichina et al., Citation2009, p. 1) argue Inclusive Growth is both about ‘pace and pattern’ of growth and these two components seem to be generally important in definitions. For example, the OECD (Citation2014) argues that it is ‘a new approach to economic growth that aims to improve living standards and share the benefits of increased prosperity more evenly across social groups’ (p. 8; added emphasis). Most definitions take these two components as a starting point but broaden out, adding extra components (Rauniyar & Kanbur, Citation2010). For example, the Asian Development Bank (Citation2018) adds an additional element, social welfare, in its definition of Inclusive Growth as: ‘high, sustainable growth to create and expand economic opportunities, broader access to these opportunities to ensure that members of society can participate and benefit from growth, and social safety nets to prevent extreme deprivation’.

One common feature of many institutional definitions is that they highlight not just the importance of Inclusive Growth but also suggest that by making growth inclusive it will reach untapped sections of the economy and so increase overall output. For example, the G20 (Citation2013, p. 1) – a representative body of 20 large economies – suggested that:

Too many of our citizens have yet to participate in the economic global recovery that is underway. The G20 must strive not only for strong, sustainable and balanced growth, but also for a more inclusive pattern of growth that will better mobilize the talent of our populations.

In this way, Inclusive Growth ceases to be about a trade-off between equity and efficiency, but instead suggests that by increasing equity, efficiency will also improve (Ranieri & Ramos, Citation2013).

gives a set of definitions used by both government and non-governmental organizations. The important point is that, as would be expected, the definitions vary. But this leads to considerable scope in what falls under the concept. In particular, it is unclear whether Inclusive Growth is about reducing poverty (whether absolute or relative), reducing inequality or something more general that does not necessarily take living standards into account (some definitions include the environment). The European Commission seems to define it as being about empowerment, compared with the WEF’s view which is more about sectors and poverty reduction. Definitions of institutions considering the developing world tend to focus on opportunities for productive employment, but where employment is already high, definitions are more about the opportunity to participate in the economy.

Table 1. Definitions of Inclusive Growth.

Some definitions are sprawling or vague. Perhaps the sharpest is that of the Scottish Government (Citation2015, p. 1), which narrowly suggest it is ‘growth that combines increases in prosperity with greater equity, creates opportunities for all and distributes the dividends of increased prosperity fairly’. This reflects the importance of the concept, as it does not seek to leave growth behind, but shapes it to share the benefits more widely (Ranieri & Ramos, Citation2013). Inclusive Growth is not just redistribution but increasing output and ensuring that the increase is distributed in such a way as to be ‘inclusive’. However, the wide range of definitions do little to set out how Inclusive Growth should be achieved. ‘Growth’ is a relatively simple concept, with clear, standardized and generally accepted metrics. ‘Poverty reduction’ is less clear, but still has a simple goal. But the definitions of ‘Inclusive Growth’ are vaguer and so harder to operationalize.

Several studies have tried to measure Inclusive Growth. The Brookings Institution (Shearer & Berube, Citation2017) has defined it statistically as three things: (1) the overall size of the economy – measured through jobs, new firms and output; (2) a measure of prosperity – productivity, average wages or standard of living; and (3) some indicator of narrowing economic disparity – either ‘general’ with employment, middle-class wages, working poverty or ‘racial’ – outcomes for whites and people of colour and disparities between different groups. Testing these across 100 US metro areas between 2010 and 2015, it found that only four metro areas achieved ‘Inclusive Growth’, although some metros did better by more limited definitions. In the UK, Beatty, Crisp, and Gore (Citation2016) have an ‘Inclusive Growth monitor’ for the 39 local enterprise partnership (LEP) areas of England. This uses a richer set of 18 indicators to show that while the richest places tend to be more inclusive, there is no relationship over time.

Given these varying definitions, how can Inclusive Growth be defined? Lupton (Citation2017, p. 1) argues that it is a ‘long-term, multi-faceted agenda, not a single policy initiative’ that is intended to shape policy across a range of areas. Lupton and Hughes (Citation2016, p. 6) suggest that:

the key idea is that if we want to have societies which are more equal and have less poverty, we need to focus on the economy and the connections between economic and social policies. Strategies for investment and economic development, productivity, skills, employment and wage regulation must be integral to attempts to achieve greater fairness and social inclusion. Likewise, enabling more people to participate fully in economic activity must be fundamental to developing prosperous and sustainable economies.

Another way of considering Inclusive Growth is to take a broader view, situating the concept in current politics. First, Inclusive Growth is a concept in the sense that Lupton and Hughes discuss it, although, as they note, it is fuzzy and subject to multiple meanings and definitions. Related to this, frameworks are being developed, allowing this concept to be applied, although these are still nascent. Second, the concept underpins a new agenda in urban and regional economic development. Inclusive Growth represents a shared set of interests at the heart of which is the idea that by linking growth and inclusion it is possible to reconcile the two. Organizations signed up to this generally do so in a well-meaning way with progressive goals. They may have different exact definitions, but their broad direction is similar. However, a third way of understanding Inclusive Growth is more critical: it can also be understood as a buzzword, applied to policy regardless of whether policy has changed because of the policy agenda, and used simply to signal intent. Like other buzzwords used in similar situations, it has multiple meanings and can be used to justify different types of policy intervention (Cornwall & Brock, Citation2005). It allows policy to be branded with a certain set of intentions and associations. However, the danger of a buzzword is that it can lose meaning and so be applied to pre-existing policies while changing little.

THE RATIONALE FOR INCLUSIVE GROWTH IN CITIES

Underpinning the Inclusive Growth-in-cities agenda are two related, but distinct, sets of arguments: those outlining why Inclusive Growth is a necessary approach, and those for why cities are the appropriate scale. Most arguments in the former group start with concerns about poverty and inequality, followed by some assertion that economic growth, without intervention, will either bypass or worsen these problems. Any new high-technology cluster, business park, skills policy or neighbourhood scheme will benefit some over others, regardless of its success. Yet, this is too rarely considered by policy-makers (Pike, Rodríguez-Pose, & Tomaney, Citation2007). As Green, Froy, Sissons, and Kispeter (Citation2017) argue, the Inclusive Growth agenda can have a dual impact, both through new policies and in shaping existing ones.

There are also strong pragmatic justifications for attempts to link growth with inclusion. In less developed countries the popularity of Inclusive Growth was partly because smaller states made redistribution harder (Ianchovichina et al., Citation2009). Similarly, redistribution is rarely near the top of public concerns in the Global North. In the UK, for example, 30% of the population in 2014 agreed the government should spend more on welfare benefits for the poor; but 39% disagreed (NatCen, Citation2015). Inclusive Growth helps avoid the electoral challenges of taxation and redistribution. It is probably no coincidence that Inclusive Growth has become important in the developed world at a time when most countries face austerity and government is unwilling to spend on redistribution.

Inclusive Growth also highlights the potential benefits of reducing poverty and inequality for growth. Empirical evidence, including a famous study from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Ostry, Berg, & Tsangarides, Citation2014), has shown that inequality can be a drag on growth. Some of the significant reports as part of the Inclusive Growth agenda have made similar claims. For example, the RSA’s Inclusive Growth Commission (Citation2016, p. 4) argued that ‘reducing inequality and deprivation can itself drive growth’. Alongside this, Inclusive Growth highlights the important links between economic and social policy.Footnote1 These links are clearest in employment and skills policies, where investments in skills provision can achieve the dual goal of increasing individual welfare while improving aggregate economic success. But they extend across other policy areas, including education, health services and social care. By bringing these links onto the agenda, the agenda recognizes the contribution of other public services to growth, but also the relationships between society and the economy.

An important strength of the Inclusive Growth agenda is that it offers the potential for a holistic approach to addressing poverty and inequality (Lupton, Citation2017). By building links across policy areas, Inclusive Growth can also help marshal new resources to address poverty and inequality. Policy-makers are unlikely to give up their focus on growth: it is the dominant discourse, public institutions are focused on it, and few politicians could run successfully on an anti-growth agenda. In linking the growth agenda with an inclusive one, the agenda can attract new resources and help organizations which have a longstanding focus on growth to address a new target. In doing so, the Inclusive Growth agenda helps mobilize new resources to the challenge of reducing poverty and inequality. It takes a policy goal with widespread interest and considerable resources (growth) and uses it to address an issue for which public support has sometimes waned (inclusion).

A second set of arguments focus specifically on why cities should be the focus of Inclusive Growth. There has been a ‘global trend to devolution’ (Rodríguez-Pose & Gill, Citation2003), with subnational governments in many parts of the world being given new powers and responsibilities. This trend has been most clear in cities – with a range of popular books highlighting the economic importance of the urban area, and their crucial economic role (e.g., Storper, Citation2013). Structural change and globalization have, paradoxically, made cities seem particularly important economic actors. Having been partially resurgent from post-industrial shift, cities were then in a position to focus on the distribution of the benefits (Lupton et al., Citation2016).

Approaches focused on cities also reflect the fact that these are where inequality is most obvious (Glaeser et al., Citation2009; Lee et al., Citation2016). Scholars have expressed concern about this inequality for some time, while high-profile urban politicians have successfully run for office on anti-inequality mandates, most famously Bill De Blasio, Mayor of New York. Related to this is a third factor: the increased dissatisfaction of some urban electorates with the anti-poverty strategies of national policy-makers.

According to proponents, there are significant practical justifications for a local approach to Inclusive Growth. Growth is context specific and the obsession with GDP ignores factors such as the composition of growth (by sector, occupation or other factors) which may help growth translate to improved living standards. Turok (Citation2010) suggests that urban approaches provide multiple benefits for Inclusive Growth: (1) they allow new approaches to be developed and trialled in a local area, with the successful ones then used elsewhere; (2) a city focus allows a unified approach with different local actors engaging towards a unified goal; (3) better targeting of groups who may not be benefiting from increased living standards; (4) developing community potential; (5) coordination of policy agendas; and (6) because the composition of growth tends to be local, they allow tailored policy to be developed for a specific local context. Some argue that cities can come up with new approaches to Inclusive Growth. For example, the OECD’s Angel Guerria suggested – when launching the OECD’s work on Inclusive Growth – that:

If we are to succeed, then we have to ensure that cities are at the heart of the fight. After all, while it is in cities where the pernicious effects of inequalities are most acutely felt, it is also in cities that the most innovative and effective solutions can be brought to bear.

(OECD, Citation2016, p. 2)

THE INCLUSIVE GROWTH AGENDA: LIMITATIONS

What is problematic about the Inclusive Growth-in-cities agenda? It seems hardhearted to critique such a well-meaning agenda, but there are problems both with the concept of Inclusive Growth and its practical application. In particular, its fuzziness makes it hard to operationalize; it remains unclear what works in achieving it; and it reflects an overconfidence in the ability of subnational governments to shape their local economies. This leads to concerns it is simply a placebo, promising to address two difficult issues – low growth and high inequality – but doing little except make policy-makers feel better about themselves.

Fuzzy concepts and unfocused policy

In a classic study, Markusen (Citation1999, p. 702) set out the problem of ‘fuzzy concepts’ where ‘researchers may believe they are addressing the same phenomena but may actually be targeting quite different ones’. Given its multiple definitions, Inclusive Growth falls into this category. Definitions vary and, while all tend to be based around the need for growth to provide opportunities for all, are often sprawling, including policy areas which extend far from the basic concept (Green, Kispeter, et al., Citation2017). Definitions often put almost any progressive policy goal – quality of life, health, jobs, environment and community – under the Inclusive Growth banner. The concept also has overlaps with the more specific notion of Inclusive Innovation (George, McGahan, & Prabhu, Citation2012). But it is often defined according to the prior interests or beliefs of the interpreter, like a conceptual Rorschach test.

One fuzzy issue is spatial scale. The literature on Inclusive Growth in cities tends to consider two related but distinct goals: inequality between and within places. For example, the European Commission (Citation2010) considers territorial cohesion as a key aspect and the RSA’s Inclusive Growth Commission (Citation2016, p. 6) explicitly argued for the need to address ‘inequalities in opportunities between different parts of the country and within economic geographies’. Yet, both goals are problematic. Addressing inequalities between different parts of the county is basically the goal of regional policy. Policy-makers have worked to improve regional policy for more than 50 years, but disparities remain large. If the Inclusive Growth agenda helps attract more resources for this goal, or improved ways of doing things, then it can be positive here. But the danger is that Inclusive Growth simply becomes a label for doing things which were not done particularly well or would have been done anyway. Addressing inequalities within cities or regions is also difficult. If new resources were found, it is not clear what the balance of priorities should be: should money be focused at inner-cities or wider areas? Any new agenda is likely to fall victim to the longstanding problems of competition between different local government areas and agencies (Gordon, Citation1999).

Another unanswered question about Inclusive Growth is: should it focus specifically on the relationship between growth and inclusion or be a broader concept? It is hard to operationalize the central idea at the heart of the Inclusive Growth agenda – that growth and inclusion are linked. There are some obvious areas that sit between the two, such as skills or labour market policy. But it is difficult to have a strategy that consists solely of these overlapping issues, meaning that strategies focused on Inclusive Growth often also include policy areas that might be more appropriately focused on growth or inclusion separately. For example, the Inclusive Growth Strategy of Leeds, a city in the North of England, focused on 12 ‘Big Ideas’, policy areas under which other policy is made. But there are clear tensions in a strategy such as this: some Big Ideas, such as skills, have a clear link to Inclusive Growth; others such as health, relate largely to social policy with little link made to growth; others seem parts of a standard economic development strategy with no attempt to make them ‘inclusive’.

Of course, it matters little if the concept is erratically defined, so long as it is still used to shape policy in an effective manner. But definitions matter: they enable measurement, and measurement is a crucial tool in targeting policy, focusing finances and ensuring effective evaluation. Pro-Poor Growth was reasonably clearly defined, yet there were still debates about how it could be achieved (Grimm et al., Citation2015). Inclusive Growth is broader and harder to pin down, making it even harder to focus resources on it. Without some sort of focus, any new resources that come with the wave of interest in Inclusive Growth will be spread thinly and risk having little impact. If Inclusive Growth is used too loosely it starts to lose meaning and, eventually, usefulness.

Unless it has a clear meaning, Inclusive Growth can become a policy buzzword – a label applied to policies that might have happened anyway or which are some distance from the initial concept. One example of this is the concept of ‘poverty reduction’, which began as a progressive goal but was eventually applied loosely to policies with little direct impact on poverty (Cornwall & Brock, Citation2005). There are early signs that Inclusive Growth is being used as such a buzzword, with strategies making reference to Inclusive Growth but little different than they would have been if the term had not become fashionable. One example is the UK’s Greater Birmingham and Solihull LEP, a body tasked with furthering economic development in the region. The LEP has the goal of achieving ‘smarter, more sustainable and more inclusive growth’ in the region (Greater Birmingham and Solihull LEP, Citation2016, p. 5). However, the body’s economic strategy is narrowly focused on the traditional goal of reducing unemployment. In this case, Inclusive Growth resembles a buzzword, used by policy-maker with little practical effect, rather than a genuine attempt to shift policy. If Inclusive Growth had a more precise definition, it would be harder for this to happen.

What works in local Inclusive Growth?

The conceptual fuzziness of Inclusive Growth makes it hard to produce useful policy frameworks: fuzzy concepts lead to unfocused policy. In particular, it is not clear what the goal of Inclusive Growth should be. If Inclusive Growth is aimed at reducing inequality, it may distract attention from investments which increase overall welfare, but where the benefits are skewed (Ianchovichina et al., Citation2009). Growth can be socially beneficial even when it is not inclusive: China’s economic success in the 1990s and 2000s reduced poverty in 500 million people, but, as inequality rose, it was not necessarily ‘inclusive’ (Ranieri & Ramos, Citation2013).

It is not yet clear if the Inclusive Growth-in-cities agenda has led to meaningful change, in developed countries at least. Many of the policies around Inclusive Growth may have happened anyway. Skills are often cited as being a vital part of Inclusive Growth, but this has always been a priority for some policy-makers (if not all). So it is not clear whether integration of these things into new Inclusive Growth strategies is a change on what would have happened without the agenda. In one study of the policy impact of the agenda, Sissons, Green, and Broughton (Citation2017) consider the case of UK devolution. They show that cities are focused on supply-side interventions in the labour market, with little evidence of a deeper integration of Inclusive Growth into city strategies.

One problem is that the evidence base on what works in making growth inclusive is still weak. This is a problem in the developing world where, despite the concept having been used for some time, there is little evidence on the appropriate policy mix to make growth inclusive (Dollar, Kleineberg, & Kraay, Citation2016). This problem is far worse in the developed world where the concept has only recently become popular. An evidence base is developing, however (Benner & Pastor, Citation2015; Beel, Jones, Rees Jones, & Escadale, Citation2017). In the UK, institutions such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) and the RSA have started to produce frameworks. One such framework is that produced by the IGAU at the University of Manchester, which outlines seven pillars of inclusive local economic growth. But it takes time for evidence to be developed and used by policy, and the policy-makers are currently running ahead of the evidence base. The danger is that strategies are rolled out before we know whether or not they will work.

The politics of Inclusive Growth

Another set of critiques focus on the political use of Inclusive Growth. The concept implies that trade-offs can be avoided, with no tension between growth-focused policy and that addressing inequality. But this means that redistribution, often the most effective way of addressing poverty, becomes secondary as a tool for raising living standards. This is explicit in justifications of the concept in a World Bank paper on Inclusive Growth. Ianchovichina et al. (Citation2009, p. 2) argue ‘the focus is on productive employment rather than on direct income redistribution, as a means of increasing incomes for excluded groups’. The concept grew in importance in the developing world, where state income was not large enough to allow redistribution. As with Pro-Poor Growth, Inclusive Growth has become popular in response to a controversial set of policies – the Washington Consensus and Austerity respectively (Leschke, Theodoropolou, Watt, & Lehndorff, Citation2012) – in cities, which often lack the resources of national government. But it raises the following question: is it is a pragmatic attempt to do something in these circumstances or a buzzword used to avoid hard choices in periods of austerity?

The most important critique of the Inclusive Growth-in-cities agenda is that cities have only limited ability to shape either growth or inclusion in their local area. Cities often lack the powers they need to make growth inclusive. Turok (Citation2010) argues Inclusive Growth can only succeed with ‘active state involvement in market mechanisms’ – but while powers vary, cities in countries such as the UK tend to lack powers in areas that would be considered basic at a national level, such as skills. Much of the new Inclusive Growth-in-cities agenda reflects the argument and challenges made by those arguing more generally for devolution of power to local areas. Yet, this agenda suffered from significant problems. Devolution of power to subnational areas is no guarantee of economic success (Pike, Rodríguez-Pose, Tomaney, Torrisi, & Tselios, Citation2012). The Inclusive Growth agenda is no less problematic. There are always concerns that cities or regions in areas that have experienced significant growth tend to be the most unequal (Lee et al., Citation2016). Affluent places tend to have more resources to address their social challenges, and it is likely in these places that the agenda will have most success. It is harder to see how the agenda can succeed in low-growth cities or regions without national intervention. In countries such as the UK, these challenges are compounded by the significant reductions in public spending, with this austerity policy disproportionately reducing funding for local government (Pike et al., Citation2017). Cities have few powers to make growth Inclusive, and their funding is, in many cases, falling.

Even if cities did have the powers to ‘drive’ growth, it would be hard for them to do so. National government tends to have the major powers to shape the economy, ranging from levers of the macroeconomy to demand-side policy. Even with these powers, growth is difficult. This problem is much worse at a local level. Cities already devote considerable attention to achieving growth, whether or not it is inclusive. But the pursuit of growth is often futile, as the impact of urban policy on city economies is inevitably marginal compared with the impact of wider economic change (Champion & Townsend, Citation2011). The processes of technological change and globalization that have probably contributed to the uneven income distributions in many countries are global trends. While national government can certainly mitigate against these trends, city governments tend to have fewer powers. Many of the problems of poverty and inequality faced by cities are the result of city policy (Lupton & Hughes, Citation2016). City governments cannot magic up economic growth, and they will find it even harder to shape it.

CONCLUSIONS

There is now significant momentum around the Inclusive Growth-in-cities agenda. The concept was initially popular in development, before spreading to countries and then cities in the developed world. It has parallels with past attempts to reconcile growth and equity, such as Pro-Poor Growth, in that it has come about at a time of austerity, with growing concerns about inequality and political differences between cities and national governments. The Inclusive Growth agenda is a long-overdue recognition that urban economic development has tended to focus on growth, with little consideration of who benefits. It has drawn new organizations into the debate on inequality, has mobilized new resources and has already had an impact on policy. Perhaps most importantly, it may be shaping pre-existing policies in a way that means they now consider distribution (Green, Froy, et al., Citation2017), and it can do this without the painful and difficult challenge of redistribution.

Yet, as the agenda becomes more mainstream in local economic development, it faces significant challenges, not least that it overstates the extent to which city governments can drive growth and shape its distribution, that policy frameworks are still developing, and that the evidence base on ‘what works’ is poor. Inclusive Growth is a fuzzy concept, with the benefits and potential costs that entails. Because it is so hard to disagree with the notion of Inclusive Growth, the danger is that it becomes a sort of placebo: helping policy-makers feel they are doing the right thing, but without leading to meaningful change. And as the Inclusive Growth agenda gains in popularity, it does so in a challenging context. UK local government is experiencing long-term cuts in its budgets, with the austerity policies of central government having a disproportionate impact on local government (Fitzgerald & Lupton, Citation2015; Pike, Coombes, O’Brien, & Tomaney, Citation2018). The Inclusive Growth agenda is only a sticking plaster over these deep cuts.

But the Inclusive Growth agenda does not have to be perfect, it simply has to be better than the alternatives. Given the political challenges faced by any form of redistribution, the continued desire for growth and the public perception that reducing the national debt should be a policy priority, it is hard to see what the alternatives are for urban policy-makers who lack the finance or powers to redistribute. In the end, success for Inclusive Growth as a policy agenda may not be in the new policies and frameworks, but in the way existing programmes and policies are reconfigured to consider distributional considerations (Green, Froy, et al., Citation2017). The Inclusive Growth agenda highlights the importance of distribution, and – in some respects – the trade-offs necessary in policy-making (OECD, Citation2014). Rather than a single, focused policy initiative, it can be better understood as a wider agenda (Lupton et al., Citation2016). It might be that this agenda causes policy-makers to reflect and adapt policies across a range of areas to consider their potential impact on low-income groups. In doing so, the fuzziness of the concept may actually be helpful as it is both politically acceptable and can be used by multiple agencies. The precise definition of Inclusive Growth is fuzzy, but the overall goal is clear.

The challenge for the Inclusive Growth agenda is to prove that it is achieving change. Similar policy agendas have offered the ‘allure of optimism and purpose’ but have led to relatively little positive change (Cornwall & Brock, Citation2005, p. 1044), and early evidence suggests this may be true of Inclusive Growth (Sissons et al., Citation2017). To do this, the frameworks being developed need to be refined and developed. While these provide a useful strategic overview, they need to be fleshed out with evidence on the actual interventions that help translate intentions into outcomes. Initiatives such as the IGAU at the University of Manchester have helped to do this. But evaluation of policy takes time, and the benefits of the agenda may not be apparent for a while. The challenge for proponents of the agenda is to maintain momentum while refining concepts and developing realistic frameworks that work but doing so without offering more than local policy-makers can realistically achieve.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper draws significantly on a discussion the author had with Richard Crisp. The author also thanks two excellent referees and the editor, David Bailey, along with David Beel, Francesca Froy, Steve Gibbons, Anne Green, Mike Hawking, Martin Jones, Ruth Lupton, Andy Pike, Alistair Rae, Atif Shafiq, Paul Sissons and Josh Stott, and the attendees at seminars at Sheffield Hallam University and Sheffield University.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The author is grateful to a referee for this point.

REFERENCES

- Asian Development Bank. (2018). Inclusive growth. Retrieved May 25, 2018, from https://www.adb.org/themes/social-development/poverty-reduction/inclusive-growth

- Ayres, S., Flinders, M., & Sandford, M. (2018). Territory, power and statecraft: Understanding English devolution. Regional Studies, 52(6), 853–864. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2017.1360486

- Beatty, C., Crisp, R., & Gore, T. (2016). An inclusive growth monitor for measuring the relationship between poverty and growth. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF).

- Beel, D., Jones, M., Rees Jones, I., & Escadale, W. (2017). Connected growth: Developing a framework to drive inclusive growth across a city-region. Local Economy: Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 32(6), 565–575. doi: 10.1177/0269094217727236

- Benner, C., & Pastor, M. (2015). Equity, growth, and community: What the nation can learn from America’s metro areas. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Cavanaugh, A., & Breau, S. (2017). Locating geographies of inequality: Publication trends across OECD countries. Regional Studies, 45, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2017.1371292

- Champion, T., & Townsend, A. (2011). The fluctuating record of economic regeneration in England’s second-order city-regions, 1984–2007. Urban Studies, 48(8), 1539–1562. doi: 10.1177/0042098010375320

- Chenery, H., Ahluwalia, M. S., Duloy, J. H., Bell, C. L. G., & Jolly, R. (1974). Redistribution with growth; Policies to improve income distribution in developing countries in the context of economic growth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Clarke, S., & D’Arcy, C. (2016). Low pay Britain 2016. London: Resolution Foundation.

- Cornwall, A., & Brock, K. (2005). What do buzzwords do for development policy? A critical look at ‘participation’, ‘empowerment’ and ‘poverty reduction’. Third World Quarterly, 26(7), 1043–1060. doi: 10.1080/01436590500235603

- Crisp, R., Cole, I., Eadson, W., Ferrari, E., Powell, R., & While, A. (2017). Tackling poverty through housing and planning policy in city regions. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF). Retrieved from https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/tackling-poverty-through-housing-and-planning-policycity-regions

- Dollar, D., Kleineberg, T., & Kraay, A. (2016). Growth still is good for the poor. European Economic Review, 81, 68–85. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.05.008

- Durán, P. (2015). What does inclusive economic growth actually mean in practice?, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Our Perspectives blog. Retrieved from http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2015/7/31/What-does-inclusive-economic-growth-actually-mean-in-practice-.html

- European Commission. (2010). Europe 2020: A European strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Brussels: European Commission.

- Ferreira, F. H., Leite, P. G., & Ravallion, M. (2010). Poverty reduction without economic growth?: Explaining Brazil's poverty dynamics, 1985–2004. Journal of Development Economics, 93(1), 20–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2009.06.001

- Fitzgerald, A., & Lupton, R. (2015). The limits to resilience? The impact of local government spending cuts in London. Local Government Studies, 41(4), 582–600.

- George, G., McGahan, A., & Prabhu, J. (2012). Innovation for inclusive growth: Towards a theoretical framework and a research agenda. Journal of Management Studies, 49(4), 661–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01048.x

- Glaeser, E. L., Resseger, M., & Tobio, K. (2009). Inequality in cities. Journal of Regional Science, 49(4), 617–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9787.2009.00627.x

- Gordon, I. (1999). Internationalisation and urban competition. Urban Studies, 36(5–6), 1001–1016. doi: 10.1080/0042098993321

- Gordon, I. R. (2018). In what sense left behind by globalisation? Looking for a less reductionist geography of the populist surge in Europe. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 95–113. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsx028

- Greater Birmingham and Solihull LEP. (2016). A greater Birmingham for a Greater Britain. Retrieved from http://centreofenterprise.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/GBSLEP-SEP-2016-30.pdf

- Green, A., Froy, F., Sissons, P., & Kispeter, E. (2017). How do cities lead an inclusive growth agenda? International experiences. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF).

- Green, A., Kispeter, E., Sissons, P., & Froy, F. (2017). How international cities lead inclusive growth agendas. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Green, A. E., & Livanos, I. (2015). Involuntary non-standard employment and the economic crisis: Regional insights from the UK. Regional Studies, 49(7), 1223–1235. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2013.825712

- Grimm, M., Sipangule, K., Thiele, R., & Wiebelt, M. (2015). Changing views on growth: What became of pro-poor growth? (PEGNet Policy Brief No. 1/2015). Retrieved from https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/122093/1/pegnet-policy-brief-2015-01.pdf

- Group of Twenty (G20). (2013). Declaration of the leaders of the G20 St Petersburg Summit. St Petersburg: G20.

- Harrison, J. (2012). Life after regions? The evolution of city-regionalism in England. Regional Studies, 46(9), 1243–1259. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2010.521148

- Hood, A., & Waters, T. (2017). Incomes and inequality: the last decade and the next parliament (IFS Briefing Note BN202). London: Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

- Ianchovichina, E., Lundstrom, S., & Garrido, L. (2009). What is inclusive growth? (World Bank Discussion Note). Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTDEBTDEPT/Resources/468980-1218567884549/WhatIsInclusiveGrowth20081230.pdf

- Kakwani, N., & Pernia, E. M. (2000). What is pro-poor growth? Asian Development Review, 18(1), 1–16.

- Kanbur, R. (2000). Income distribution and development. In A. B. Atkinson, & F. Bourguignon (Eds.), Handbook of income distribution (Vol. 1, pp. 791–841). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Kuznets, S. (1955). Economic growth and income inequality. American Economic Review, 45(1), 1–28.

- Lee, N., Morris, K., & Kemeny, T. (2018). Immobility and the Brexit vote. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 143–163. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsx027

- Lee, N., & Sissons, P. (2016). Inclusive growth? The relationship between economic growth and poverty in British cities. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(11), 2317–2339. doi: 10.1177/0308518X16656000

- Lee, N., Sissons, P., & Jones, K. (2016). The geography of wage inequality in British cities. Regional Studies, 50(10), 1714–1727. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1053859

- Leeds City Council. (2017). Leeds Inclusive Growth Strategy: Draft for consultation. Leeds: Leeds City Council.

- Leschke, J., Theodoropolou, S., Watt, A., & Lehndorff, S. (2012). How do economic governance reforms and austerity measures affect inclusive growth as formulated in the Europe 2020 strategy? In S. Lehndorff (Ed.), A triumph of failed ideas. European models of capitalism in crisis (pp. 243–281). Brussels: ETUI.

- Lopez, J. H. (2004). Pro-poor growth: A review of what we know (and of what we don’t). Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from http://www.eldis.org/vfile/upload/1/document/0708/DOC17880.pdf

- Lupton, R. (2017). Towards inclusive growth in Greater Manchester. Retrieved from http://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/mui/igau/events/Ruth-Lupton.pdf

- Lupton, R., & Hughes, C. (2016). Achieving inclusive growth in Greater Manchester: What can be done? Manchester: Inclusive Growth Analysis Unit, University of Manchester.

- Lupton, R., Rafferty, A., & Hughes, C. (2016). Inclusive growth: Opportunities and challenges for Greater Manchester. Manchester: Inclusive Growth Analysis Unit, University of Manchester.

- Markusen, A. (1999). Fuzzy concepts, scanty evidence, policy distance: The case for rigour and policy relevance in critical regional studies. Regional Studies, 33(9), 869–884. doi: 10.1080/00343409950075506

- NatCen. (2015). British Social Attitudes Survey 32. London: NatCen. Retrieved from http://www.bsa.natcen.ac.uk

- O’Connell, S. A. (2014). Redistribution with growth, 40 years on. Frontiers in Development 2014: Ending Extreme Poverty, 58–63.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2011). Divided we stand: Why inequality keeps rising. Paris: OECD.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2014). All on board: Making inclusive growth happen. Paris: OECD.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2016). The New York proposal for inclusive growth in cities. Paris: OECD.

- Ostry, J., Berg, A., & Tsangarides, C. G. (2014). Redistribution, inequality, and growth (IMF Staff Discussion Note No. SDN/14/02). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund (IMF).

- Peck, J. (2011). Global policy models, globalizing poverty management: International convergence or fast-policy integration?. Geography Compass, 5(4), 165–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00417.x

- Pike, A., Coombes, M., O’Brien, P., & Tomaney, J. (2018). Austerity states, institutional dismantling and the governance of sub-national economic development: The demise of the regional development agencies in England. Territory, Politics, Governance, 6(1), 118–144. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2016.1228475

- Pike, A., Lee, N., MacKinnon, D., Kempton, L., & Iddawela, Y. (2017). Job creation for inclusive growth in cities. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF).

- Pike, A., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2007). What kind of local and regional development and for whom? Regional Studies, 41(9), 1253–1269. doi: 10.1080/00343400701543355

- Pike, A., Rodríguez-Pose, A., Tomaney, J., Torrisi, G., & Tselios, V. (2012). In search of the ‘economic dividend’ of devolution: Spatial disparities, spatial economic policy, and decentralisation in the UK. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 30(1), 10–28. doi: 10.1068/c10214r

- Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ranieri, R., & Ramos, A. R. (2013). Inclusive growth: Building up a concept (Working Paper No. 104). Washington, DC: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth.

- Rauniyar, G., & Kanbur, R. (2010). Inclusive growth and inclusive development: A review and synthesis of Asian Development Bank literature. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 15(4), 455–469. doi: 10.1080/13547860.2010.517680

- Ravallion, M. (2004). Pro-poor growth: A primer (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 3242). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Ravallion, M. (2015). The economics of poverty: History, measurement, and policy. Washington, DC: Oxford University Press.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Gill, N. (2003). The global trend towards devolution and its implications. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 21(3), 333–351. doi: 10.1068/c0235

- Royal Society of Arts (RSA). (2016). Inclusive Growth Commission: Prospectus of inquiry. London: RSA.

- Royal Society of Arts (RSA). (2017). Inclusive Growth Commission: Making our economy work for everyone. London: RSA.

- Scottish Government. (2015). Scotland’s economic strategy. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Shearer, R., & Berube, A. (2017, April 27). The surprisingly short list of U.S. metro areas achieving inclusive economic growth. Brookings Institution Avenue blog. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2017/04/27/the-surprisingly-short-list-of-u-s-metro-areas-achieving-inclusive-economic-growth/

- Sissons, P., Green, A., & Broughton, K. (2017, June). Inclusive growth in English cities: mainstreamed or sidelined? Paper presented to the Regional Studies Association (RSA).

- Storper, M. (2013). Keys to the city: How economics, institutions, social interaction and politics shape development. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Summers, L. H., & Balls, E. (2015). Report of the Commission on Inclusive Prosperity. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

- The Resolution Foundation. (2014). Growth without gain? The final report of the Commission on Living Standards. London: Resolution Foundation.

- Tomaney, J. (2016). Limits of devolution: Localism, economics and post-democracy. Political Quarterly, 87(4), 546–552. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12280

- Turok, I. (2010). Inclusive growth: Meaningful goal or mirage? In A. Pike, A. Rodríguez-Pose, & J. Tomaney (Eds.), Handbook of local and regional development (pp. 74–86). London: Routledge.

- United Nations. (2016). New urban agenda. New York: United Nations.

- Wessel, D. (2015). The typical male U.S. worker earned less in 2014 than in 1973. New York Times, September 18. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/the-typical-male-u-s-worker-earned-less-in-2014-than-in-1973/

- World Bank. (2017). Promoting inclusive growth by creating opportunities for the urban poor ( Philippines Urbanization Review Policy Note). Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/904471495808486974/Promoting-inclusive-growth-by-creating-opportunities-for-the-urban-poor

- World Economic Forum (WEF). (2015). The inclusive growth and development report 2015. Retrieved from http://www.weforum.org/reports/inclusive-growth-and-development-report-2015

- Yin, J. Y. (2004). Developing strategies for inclusive growth in developing Asia. Asian Development Review, 22, 1–27.