?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the main determinants of the representation of foreign employees across German regions. Since migration determinants are not necessarily the same for workers of different nationalities, spatial patterns are explained not only for total foreign employment but also for the 35 most important migration countries to Germany. Based on a total census for all 402 German districts, the paper starts by showing the spatial distributions of workers with different nationalities and explains the emerging patterns by spatial error models. Although large heterogeneity in determinants across nationalities are found, similarities between country groups prevail. Economic conditions matter for most nationalities, whereas the importance of amenities and openness differ.

INTRODUCTION

About 3 million foreign employees work in Germany, but these workers are not uniformly distributed across German regions. Economically weak and rural regions attract far fewer foreign workers than do prosperous metropolitan areas. Moreover, workers of a certain nationality tend to settle in the same region. This paper investigates the reasons behind these patterns seeing that little is known about the determinants of foreign workers’ choice of a certain place of work at the regional level. There are certainly more characteristics involved in these decisions than economic conditions. Such characteristics might include proximity to the home country, functioning networks, cultural aspects or certain amenities.

This paper studies the determinants of foreign employees for German districts. We provide analyses for workers from each of the EU-28 countries separately as well as from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Norway, Russia, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine and the United States. We take a closer look at the influence of a rich set of possible determinants that have been found relevant in the literature.

The literature on determinants of migration is substantial. Labour market conditions (Buch, Hamann, Niebuhr, & Rossen, Citation2014; Scott, Citation2010) and amenities (Chen & Rosenthal, Citation2008; Partridge, Citation2010; Rodríguez-Pose & Ketterer, Citation2012) are often mentioned as the most important driving forces of migration. A low unemployment rate attract workers, as does a low crime rate, good medical care and rich cultural offerings.

Cultural and ethnic factors have become an increasingly focus of academics. Ethnic diversity may indicate tolerance (Florida, Citation2002), but it also leads to more differentiated preferences in the provision of public goods (Alesina & La Ferrara, Citation2005). A cultural environment similar to the home country also fosters migration. Geis, Übelmesser, and Werding (Citation2011) show a positive effect of cultural closeness on the migration decision, whereas Wang, De Graff, and Nijkamp (Citation2016) point out that a region’s cultural diversity can increase its attractiveness for migrants. Isphording and Otten (Citation2014) especially stress the positive effect of linguistic closeness.

Networks also have a strong positive effect on migration decisions (Ruyssen, Everaert, & Rayp, Citation2014). However, Pedersen, Pytlikova, and Smith (Citation2008) point out that the strength of the network effect can vary between different nationalities and types of welfare states. Climatic factors also play a role in migration decisions; the recent study by Beine and Parsons (Citation2015) shows that long-run climatic factors have an indirect effect on migration through the wage channel.

Besides the already mentioned determinants, previous studies also focused on the role of geographical distance. This focus is motivated by the idea of modelling immigration via a gravity model (Lewer & Van den Berg, Citation2008) that assumes distance to be one of the main migration costs (Clark, Hatton, & Williamson, Citation2007; Mayda, Citation2010). Throughout the literature there is broad evidence for the importance of distance in explaining migration (Arntz, Citation2010; Bessey, Citation2012; Clark et al., Citation2007; Etzo, Citation2011; Mayda, Citation2010). Although long-distance interregional migration is mainly driven by economic factors and short-term interregional migration is mainly driven by amenities, distance seems to be relevant in both cases (Biagi, Faggian, & McCann, Citation2011; Niedomysl, Citation2011).

As we are interested in the ‘big picture’ and therefore in all aspects of migration determinants, we complement the literature by studying labour market and economic conditions, amenities, aspects of openness, and distance as pull factors for labour migration at the regional level in Germany. To our knowledge, spatial distribution within the host country of foreign workers of different nationalities has not been studied in much detail. We begin our investigation with descriptive evidence for the spatial distribution in Germany of foreign workers from 35 countries. To capture over- and under-representation of foreign employment at the district level, we calculate representation quotients using a total census from the German Federal Employment Agency. A rich set of migration determinants for the German districts is then employed to explain the different representation patterns that emerge for different nationalities.

We find that the determinants of migration vary in importance between workers from different home countries. Regional economic conditions seem to be the most important determinants for workers from the EU-15 (excluding Germany). Amenities are, on the opposite, most important for workers from countries that joined the European Union in 2004 or later. Also variables for regional openness are predominant determinants. Distance is found to be an important factor as well, especially for workers from countries geographically adjacent or geographically close to Germany.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section shows spatial patterns of workers with different nationalities. The third section sets out the empirical strategy and describes the data. The fourth section presents the results. The final section concludes.

SPATIAL DISTRIBUTIONS OF FOREIGN EMPLOYMENT

The literature contains well-grounded insights into the migration interdependence between countries and the determinants of emerging migration patterns. However, these insights do not indicate much about the distribution of foreign workers within the host country. In this section we take a closer look at the distribution of workers from a particular country across German regions.

A distribution is characterized either by the absolute number of values or in terms of relative frequencies. We use the fraction of relative frequencies to show the representation of foreign workers in relation to total employment at the regional level. To measure this representation of workers with nationality j for the German district i at time t, we use the following representation quotient :

with

and

The first component of the

is the foreign worker quotient (

), which shows the distribution of employees with nationality j within Germany. It holds:

However, simply using these shares would not correctly indicate the size of the regional entity or its corresponding labour market. We therefore divide the FWQ by our second component: the employment quotient (

). Note that the

is invariant to the nationality; instead, it reveals the distribution of employed persons across German regions. It also holds:

The is basically the share of foreign employees in a specific district weighted by the relative size of the local labour market. As we apply district-constant weights,

is a comparable measure across nationalities. It is defined between zero and infinity, with zero meaning that nobody with nationality j works in that district. An

indicates that the distribution of workers matches their total German representation. Consequently, an

indicates over-representation and an

under-representation compared with the German average.

To calculate the representation quotients, we rely on a total census of employees subject to social security insurance (German Federal Employment Agency, Citation2013; see also the supplemental data online). The reported district is the workplace of the employee. Thus, we know the total number of employees with nationality j as well as the total number of all employees for each district i in Germany. We use annual data from 2004 to 2012 that are reported at the cut-off date of 31 December. The cross-section dimension includes all 402 German districts and district-free cities as of 2016. We can rely on data for 35 nationalities that comprise all nine direct neighbours of Germany, as well as the complete European Union and other important immigration countries such as Belarus, Russia, Turkey and Ukraine. Norway and the United States complete the picture. In 2012, these 35 nationalities represented about 81% of all foreign employees in Germany.

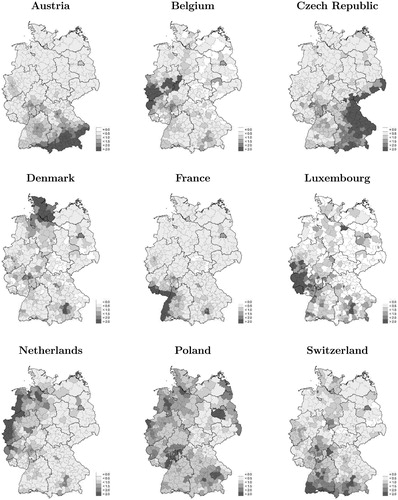

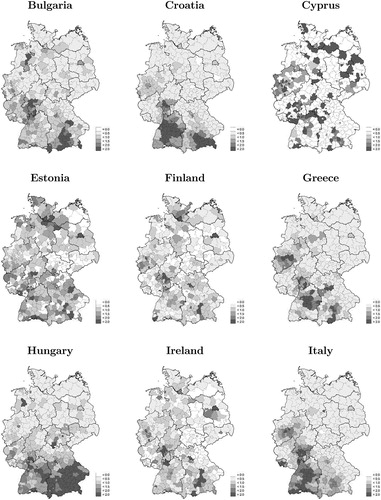

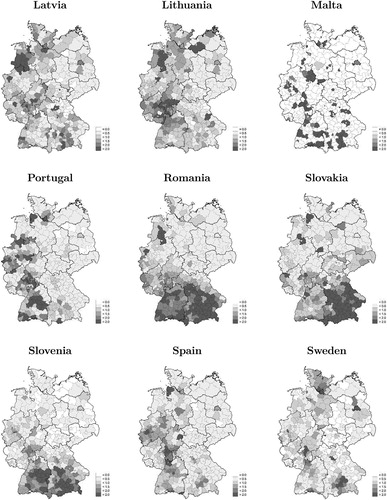

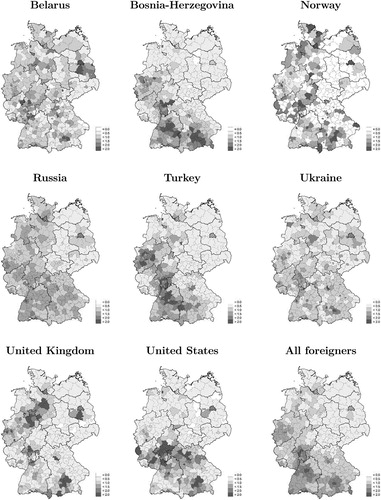

The simplest way of detecting regional patterns is to draw maps; the results can be seen in (for further descriptives, see the supplemental data online). presents the representation quotients in 2012 for the countries neighbouring Germany. and show the same for the European Union member states. contains the remaining countries and total foreign employment. To achieve comparability, we use the same six RQ categories in each figure, running from RQ = 0.0 to > 2.0 in 0.5 steps. The colour coding runs from white (no foreign worker) to dark grey (high over-representation).

reveals interesting patterns for Germany’s neighbours. First, several hotspots such as Frankfurt am Main and Munich are preferred by workers from abroad. A high wage level and a broad range of amenities could be two of several reasons for their attractiveness. Second, with the exception of Poland and the Czech Republic, a clear east–west gap in the representation quotients exists. Not many employees from Germany’s western or southern neighbour countries work in eastern Germany. An exception is Berlin, which is perceived as very attractive by people from around the world. The third and most interesting pattern is the close location to the neighbouring country’s border. This pattern holds for all neighbours with one exception: Poland. Whereas workers from the other eight neighbours cluster in rather small areas close to their home country border, Polish employees are over-represented in western Germany, which can be attributed to historical circumstances on which we elaborate more in the results section. , however, leads us to hypothesize that, next to important economic, social or cultural factors, distance from the home country might be a key factor in the location decisions of workers from Germany’s neighbouring countries.

For the remaining countries, the patterns are not clear-cut. Next to obvious country peculiarities, we also find remarkable similarities between non-neighbouring countries. Like their peers from neighbouring countries, workers from non-neighbouring countries also appear to prefer the large German cities as destination. Besides the already mentioned high wage level and amenities, the attractiveness of workers from non-neighbouring countries might also be because European institutions are located in large German cities (e.g., the European Central Bank (ECB) in Frankfurt am Main or the European Patent Office (EPO) in Munich).

In order to systematize the visual evidence for the non-neighbours, we base our description on the countries’ geographical position of the non-neighbours. Workers from countries located to the north of Germany (Finland, Norway, Sweden and the UK, but not Ireland as shown in ) are over-represented in large cities such as Hamburg, Berlin or Munich. also reveal that these workers appear to prefer the northern part of Germany. This finding could either be due to regional determinants or related to proximity to their home countries.

A very distinct pattern emerges for the non-neighbouring countries located to the south-west of Germany – Portugal and Spain. There seems to be an imaginary inner German border for Spanish and Portuguese workers which they do not cross. These workers are mostly over-represented in districts of four western German federal states: Baden-Württemberg, Hesse, North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate. This finding can partly be related to historical circumstances, on which we elaborate more in the results section.

Historical reasons might also be one driver for the emerging patterns of two large foreign communities in Germany: workers from Italy in the south and Turkey in the south-east. Both nationalities are over-represented in the two southern German federal states Baden-Württemberg and the Free State of Bavaria and in the south-western state Rhineland-Palatinate. As for workers from Turkey, Greek employees are also over-represented in the south-western part of Germany.

The next group comprises countries from Central and Eastern Europe. Remarkable similarities can be found for workers from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia, all over-represented in southern Germany. In addition to economic reasons and various amenities, we expect that distance may matter for workers from these countries. Former Soviet Union countries located to the east of Germany (Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Ukraine) do not exhibit a common pattern.

Workers from the United States are over-represented in the southern and south-western parts of Germany, since many US military bases are located in these areas. Although US soldiers and military staff are not relevant for our calculation, their relatives may work in the areas close to the bases. However, cities such as Frankfurt am Main and Munich are also hotspots for US workers, and thus the military base explanation falls short of completely explaining the distribution of US workers. This may, again, be attributed to the presence of European institutions.

In summary, the districts in the south or south-west of Germany are magnets for foreign workers, whereas there is clear under-representation in eastern German districts. In the following, we provide an empirical assessment of these patterns.

EMPIRICAL STRATEGY AND DATA

Empirical model

The maps revealed very different patterns among the nationalities considered. The next step is to discover which district- and nationality-specific factors correlate with these patterns. To do so, we use as the dependent variable in our empirical approach. Since the representation quotients do not vary much over time within the cross-section, we pooled the data in advance and employ the following empirical model:

(1)

(1)

From this general representation, we can derive three possible empirical models: (i) the spatial lag model (SLM) with

; (ii) the spatial error model (SEM) with

; and (iii) the standard cross-sectional model (CSM) with

and

.

represents the spatial weighting matrix based on inverse distances between the regional entities. The distances are calculated based on the longitude and latitude of each district as documented in Wikipedia.Footnote1 All district-specific characteristics that do not vary across nationalities are captured in the vector Xi; nationality-specific variables that also differ across districts are summarized in

. The model- and nationality-specific constant is denoted by

; and

represents the idiosyncratic error term.

The question arises which empirical model should be fitted to the data. Therefore, we first conduct a formal test on spatial dependence. There are several available tests for spatial correlation (for details, see Anselin, Citation2001) from which we chose Moran’s I as the common one. For all RQs and variables described below, we find a persistent pattern of spatial correlation. Thus, the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimators for the standard CSM can be biased (Eckey, Kosfeld, & Türck, Citation2007; Lerbs & Oberst, Citation2014).

Next, we have to decide whether to use the SLM or SEM. This decision can easily be based on the mechanics of the two models. The intuition of the SLM is straightforward: the representation quotient of district i is influenced by the RQs of all the other districts (with higher or lower intensity according to the attributed weights). Labour movement from one to another district is one reason. The SEM works differently than the SLM since it captures the spatial dependence within the error term, whereas the SLM only maps the cross-section dependence of the dependent variable. Thus, we argue that the SEM is better able to capture all general forms of spatial dependence. Consider an economic shock that hits the neighbouring district. This shock is then either transmitted directly (via changes in the RQs) or indirectly (via changes in the covariates or even through unobservable factors). Thus, the error term may capture all general spatial influences that can bias the coefficient estimates. Therefore, we base our empirical strategy on the SEM. The parameters are estimated by maximum likelihood and we apply standard errors robust to autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity.

Explanatory variables

Following the literature discussed above, we group the district-specific variables in into three categories: (1) labour market and economic conditions; (2) amenities; and (3) openness. A fourth group, which we call (4) miscellaneous, comprises the nationality-specific variables from

. The supplemental data online capture a summary of all variables, their description and source as well as descriptive statistics.

Labour market and economic conditions are intuitive determinants. For example, a district’s unemployment rate is an indicator of how tight the regional labour market is. We also add the median of monthly gross earnings to approximate a district’s overall wage level, the sectoral structure and the share of highly qualified employees as proxy of the general education level of the district’s workforce. Especially the district-specific economic structure reveals several agglomerations with clusters in regional economic activity.

The second category comprises local amenities given that quality of life can be an important factor in location decisions. We use standard measures of amenities from the literature: accessibility of European metropolises, density of physicians, share of green area, average land price, average flat size, crime rate and the number of overnight stays as a measure of a district’s overall attractiveness.

The third category includes two variables measuring openness: the ethnic diversity of a district and the total share of foreigners. Ethnic diversity is calculated as an inverse Herfindahl–Hirschman index (HHI) based on the shares of 207 nationalities. The share of foreigners is self-explanatory and captures local network effects to some extent.

The last category subsumes two variables: the average annual net change of foreign employment and geographical distance. Both variables vary by nationality and district. Net changes in foreign employment capture the regional persistence of the RQs over time, thus representing variation that arises either from network effects or because of historical reasons. Including geographical distance is based on the idea that people would rather work closer to their home countries than far away. We additionally introduce a quadratic term of distance to measure non-linearities.

In the end, we expect that the regional representation of foreign workers correlates with the above-mentioned factors, which enables one to explain the observed patterns in more detail. We also presume that the correlations vary considerably by nationality.

EXPLAINING THE SPATIAL PATTERNS

Total foreign employment

To discover which determinants are responsible for spatial patterns and to make the present study comparable with the existing literature, we first present the estimation results for the representation quotient of total foreign employment (RQALL) in .Footnote2 Thereafter, we estimate nationality-specific effects and discuss similarities and differences across country groups. We start with a similar model as used by Buch et al. (Citation2014) in column (1).Footnote3 This allows one to compare the empirical effects. Based on this model, we subsequently add the regional economic structure (2), European accessibility (3), ethnic diversity (4) and, in our full model (5), the net change in total foreign employment.Footnote4

Table 1. Estimation results – total foreign employment.

The inclusion of variables that mirror the sectoral structure of each region in the first step might reveal foreign workers’ preferred sectors. In the second step, we add European accessibility to capture the importance of infrastructural hotspots, airports and international hubs. In a third step, ethnic diversity is included under the assumption that workers prefer to locate in multicultural districts that contain a substantial number of foreigners. To capture, at least to some extent, regional networks and average effects from persistent historical movements, we add the net flow of total foreign employment in the fourth step.

In general, most amenities and determinants that measure openness correlate with the representation of total foreign employment. The explanatory power of our models for the variation between districts is generally very high (see the pseudo-R2). Starting with labour market and economic conditions, we find the expected negative coefficient of the unemployment rate. The district-specific sectoral structure also seems to matter. Districts in which total foreign employment is over-represented are characterized by a higher share in manufacturing as well as advanced and basic services. For gross earnings we find a positive and significant coefficient that vanishes after introducing the regional economic structure. Thus, maybe the median of overall gross earnings does not describe the spatial pattern, but rather sector-specific wages that we cannot observe.

Local amenities are most important in attracting foreign labour. Districts with a higher density of physicians and larger green areas exhibit higher RQs. As a disamenity, the crime rate shows the expected negative sign; thus, regions with higher representation quotients are characterized by less crime. The land price has a positive effect, which may reflect the higher perceived attractiveness of a district. The variables European accessibility, physician density and green area hint to the fact that the over-representation of foreign employment is higher in rural than urban areas. Rural regions are typically characterized by a worse connection to railroads and airports, fewer sealed areas and a worse provision of medical services.

Turning to openness, we find that districts with higher RQs also have a higher share of foreigners, but are less ethnically diverse. The net change variable points to a high persistence of RQs as this variable has no significant impact. These findings let us suggest that the observed patterns are more driven by historical reasons than by newly arrived workers.

In summary, the present approach for total foreign employment mirrors the results by Buch et al. (Citation2014). Thus, we can build on existing work to study similarities and differences across nationalities.

Similarities and differences across nationalities

Focusing on total foreign employment may obscure nationality-specific effects. In the following section we therefore ask whether the main determinants for the local representation of foreign workers differ across various countries and group of countries. For detailed estimation results, see the supplemental data online. First, we summarize the general findings. Second, we discuss the differences and similarities between three groups of countries: (1) neighbouring versus non-neighbouring countries; (2) old versus new member states of the European Union; and (3) northern versus southern Europe. After the presentation of these country group differences, we finally enrich our explanations by arguments obtained from historical circumstances. Each country-specific estimation model contains the variables from : the net flow of nationality-specific foreign employment, geographical distance by country and a corresponding squared term. Geographical distance is a value expressed in kilometres from the centre of each German district to the centroid of the respective country.

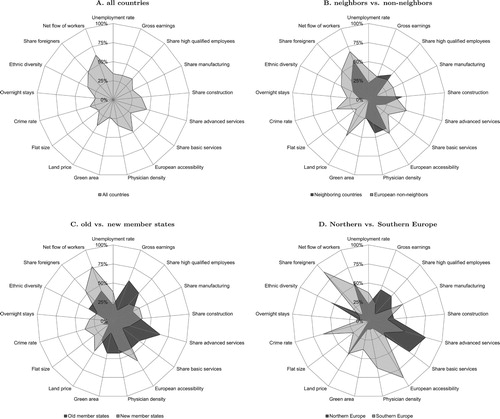

In order to densify the information, we introduce the spider charts in , which contains the relative importance of the different determinants for all countries together (panel A) and the three groups of countries (panels B–D). Relative importance is measured as the share of significant country estimations either in the total number of countries (35) or in each specific subgroup (neighbours: nine, non-neighbours: 25, old members: 14, new members: 13, northern Europe: nine, southern Europe: eight). To explain , we use the share of advanced services as an example. The relative importance is approximately 46% for all countries (panel A), which is the ratio of 16 significant coefficients divided by the total number of 35 countries in the sample. Another example is the share of foreigners for southern European countries. The importance of that determinant is approximately 88% for this subgroup, which is the ratio of seven significant estimates for eight countries. In the same manner we calculate all remaining ratios; for the exact numbers of , see the supplemental data online.

General findings for all countries

Despite the fact that a large variation in the importance of determinants exists across nationalities, the results in panel A of are clear-cut. The most important characteristic is the nationality-specific net flow of foreign workers. For 22 of 35 countries in the sample, the net change in foreign employment matters significantly. The net change is also a perfect example of effects that can be obscured by investigating aggregates. That is, for total foreign employment in we found no significant correlation at all, which points to the fact that nationality-specific effects cancel each other out. Immediately following in terms of importance is the share of foreigners, European accessibility and the share of advanced services. Overall, it seems that determinants measuring openness and amenities correlate in more cases with the RQs compared with labour market and economic conditions.

Another crucial determinant is distance to the specific home country. The largest negative coefficients can be found for Germany’s neighbours. The striking exception is Poland: there is no significant effect of distance. This result is because Poland has experienced large emigration waves throughout its history (Warchol-Schlottmann, Citation2001). The first large wave took place in the 19th century when Polish people, so called Ruhr-Polen, mainly migrated to the Ruhr area to obtain employment in mining or German industry. A second large wave occurred in the 1970s and was mainly comprised of Polish people with German ancestors, the so called Aussiedler. These people were distributed between the federal states according to a distribution scheme call Königssteiner Schlüssel (Dietz, Citation2011), which is based on tax receipts (weight: 2/3) and population (weight: 1/3) of a district. Another large wave took place in the 1980s; this was mainly comprised of late repatriates or political emigrants who had been involved in the strike movement Solidarność. Nevertheless, we observe a small band of over-representation of Polish workers in German districts next to the Polish border. Possibly there is some inherent distance effect, but the variation between the districts is not large enough to indicate a statistical difference.

Distance also plays a major role in the distribution of workers from non-neighbouring countries. For 19 of the remaining 24 countries, distance has a significant influence on nationality-specific RQs. We also find non-linearities in the distance effect. Thus, after a certain distance is reached, workers from that country become less represented. This finding clearly underpins the visual evidence described in the second section.

Neighbours versus non-neighbours

, panel B, compares the determinants between German neighbours and the remaining European non-neighbours. The most important determinant for both groups is the net flow of workers, which underpins the role of network effects. Panel B also shows remarkable differences. Whereas amenities correlate in more cases with the representation of non-neighbouring countries, local economic conditions describe the patterns of the German neighbours. Especially the importance of the local economic structure differs. Workers from neighbouring countries are over-represented in districts characterized by a higher share of qualified employees and a larger construction sector. The districts with over-represented European non-neighbouring nationalities exhibit a higher share of manufacturing and advanced services.

Old versus new EU member states

Compared with the neighbouring versus non-neighbouring discussion, the differences between old and new member EU statesFootnote5 are even more pronounced (, panel C). Economic conditions such as the median of gross earnings, the share of highly qualified employees and the share of advanced services are more important for the old member states compared with the newly joined countries. On the contrary, amenities characterize those German districts that show a higher over-representation of foreign workers from the new member states. However, the unemployment rate as well as the shares of manufacturing and construction seem to be important for the new member states. Also, possible network effects are even more pronounced in the case of the new member states, since the nationality-specific net flow of foreign workers correlates with more than three-quarters of the countries.

Northern versus southern Europe

Finally, we compare northern and southern European states.Footnote6 The main motivation for this comparison are the huge economic differences between these states. Whereas northern Europe is characterized by rather rich and economic prospering regions, the southern part of Europe contends with structural problems such as high unemployment rates or high debt levels. We observe sharp differences in the importance of determinants between northern and southern Europe (, panel D). For the representation of northern European nationalities, economic conditions such as gross earnings, the share of highly qualified employees or the economic structure are the important determinants used to describe local patterns. Amenities such as European accessibility, physician density and local crime rate are most important to explain the regional representation of southern European nationalities in Germany. Also, the share of foreigners is important, which hints at a large influence of possible network effects, since especially southern European countries are characterized by an intensive migration history with Germany.

Historical influences

We have already mentioned the influence of possible network effects to describe regional patterns. As the share of foreigners and the net flow of foreign workers significantly correlate with the regional representation of especially southern European countries, we have to elaborate on the migration waves to Germany after the Second World War. Owing to the German Wirtschaftswunder in the 1950s and 1960s, Germany signed recruitment agreements with several southern European countries (Italy in 1955, Greece and Spain in 1960 and Portugal in 1964) in order to legitimate free movement to Germany (Höhne, Linden, Seils, & Wiebel, Citation2014; Hönekopp, Citation1997; Seifert, Citation2012). These workers, usually called Gastarbeiter, are located in the Ruhr area as well as in the southern Germany. These are also the regions for which we find persistent patterns of foreign employment of those nationalities.Footnote7 One of the largest migration communities in Germany is the Turkish one. Again, the regional patterns for Turkish workers can also be described by historical circumstances. As for the former countries, Germany signed a recruitment agreement with Turkey in 1961, which also led to Turks settling as Gastarbeiter in the Ruhr area and south-western Germany.

CONCLUSIONS

Most studies on the determinants of migration focus on the country level. To date, not much is known about the within-country spatial distribution of foreign employment. This study takes a step toward addressing this gap in the knowledge with three major results for the German case that were derived by relying on a total census of employment.

We first provide descriptive evidence about the spatial distributions of foreign workers from 35 different nationalities. This evidence suggests that there are both similarities and differences in the migration determinants across nationalities. What is common to all the considered nationalities is a strong over-representation in metropolitan agglomerations. Workers from countries geographically close to Germany seem to prefer to work in proximity to their home countries. The striking exception is Poland. We suggest that strong network effects, because of a large immigration wave of Polish people to Germany in the 1970s, is the main driver for this pattern. Additionally, several country-specific hotspots are identified that were created in the past by means of recruitment agreements between Germany and several countries in the 1950s and 1960s.

In a second step, we investigate which local determinants significantly correlate with the representation of total foreign employment. We mirror the results of other work and find that in addition to local amenities and the economic structure of a region, ethnic diversity and the share of foreigners are important. Thus, this study replicates effects found in previous studies, thus providing a firm foundation for the third contribution: the exploration of variation in location determinants across nationalities. Variables measuring openness and amenities correlate in more cases with the nationality-specific representation quotients than do local labour market and economic conditions. However, we study different groups of countries for which certain determinants are more important than others. For the old EU member states, it is mainly labour market and economic conditions that explain the location patterns. A balanced mixture of labour market and economic conditions as well as some amenities and cultural factors are important for the location decisions of workers from the new EU member states. Additionally, a remarkable pronounced north/south pattern exists, with a higher importance of economic conditions for nationalities from the north and a relative higher importance of amenities and network effects for southern European nationalities. One explanation is the migration history of Germany after the Second World War.

We believe that the results presented in this paper have wide-ranging relevance that goes beyond a merely economic focus. For example, the results should be of interest to firm owners since the findings will enable them to target their recruitment efforts specifically toward those workers who have the highest probability of moving to the firm’s district. For politicians, the results carry implications for economic prosperity and social policy. In light of a shrinking and ageing population, rural regions might be especially harmed by their paucity of foreign labour. We leave such considerations and potential investigations to future research and suggest that such work not focus exclusively on economic questions, but take a more interdisciplinary approach.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (428.9 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to two anonymous referees for their very helpful comments and suggestions. They also thank Georg Hirte, Marcel Thum, Silke Übelmesser and seminar participants at: the Technische Universität Dresden; the 8th Summer Conference in Regional Science 2015, Kiel; the 71st Annual Congress of the International Institute of Public Finance (IIPF) 2015, Dublin; the 55th Congress of the European Regional Science Association (ERSA) 2015, Lisbon; the 8th Geoffrey J. D. Hewings Regional Economics Workshop 2015, Vienna; the 2015 Workshop on Migration Barriers at the Friedrich-Schiller-Universität, Jena; the ifo/CES Christmas Conference 2015, Munich; the 14th Public Finance Seminar 2015, Berlin; the Joint Annual Meeting of the Austrian Economic Association and the Slovak Economic Association 2016, Bratislava; and the 29th Conference of the European Association of Labour Economists (EALE) 2017, St Gallen. Antje Fanghänel, Franziska Kruse and Frank Simmen provided excellent research assistance. The authors also thank Deborah Willow for language editing.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Robert Lehmann http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6684-7536

Wolfgang Nagl http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8181-5284

Notes

1. Geographical data were collected and provided by Wikipedia: WikiProject Geographical coordinates. For more details, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:WikiProject_Geographical_coordinates/.

2. We also estimated the SLM and CSM. As spatial dependence is present, the coefficient and standard error estimates become more precise in the SEM and SLM case. However, the bias is not large at all. A small bias between the different specifications is also found by Berlemann and Jahn (Citation2016).

3. We use almost the same set of explanatory variables as do Buch et al. (Citation2014), but their research question is quite different from ours. Whereas we focus on stocks, they describe the effects on net flows of migrants. Nevertheless, we take their paper as an object of comparison since they focus on German cities.

4. The model for total foreign employment does not include any nationality-specific variable, such as distance. Also, the net flow of total foreign employment is an aggregate over all nationalities. In our nationality-specific estimations, however, we use the net flow of the specific nationality. Hence, the net flow varies by nationality.

5. The group of old member states comprises the EU-15 without Germany. The new member states are all countries that joined the EU in 2004 or later.

6. The distinction between northern and southern Europe is based on the United Nations definitions.

7. Population data by the German Federal Statistical Office confirm these regional patterns.

REFERENCES

- Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2005). Ethnic diversity and economic performance. Journal of Economic Literature, 43, 762–800. doi: 10.1257/002205105774431243

- Anselin, L. (2001). Spatial econometrics. In B. H. Baltagi (Ed.), A companion to theoretical econometrics (pp. 310–330). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Arntz, M. (2010). What attracts human capital? Understanding the skill composition of interregional job matches in Germany. Regional Studies, 44(4), 423–441. doi: 10.1080/00343400802663532

- Beine, M., & Parsons, C. (2015). Climatic factors as determinants of international migration. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 117(2), 723–767. doi: 10.1111/sjoe.12098

- Berlemann, M., & Jahn, V. (2016). Regional importance of Mittelstand firms and innovation performance. Regional Studies, 50(11), 1819–1833. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1058923

- Bessey, D. (2012). International student migration to Germany. Empirical Economics, 42(1), 345–361. doi: 10.1007/s00181-010-0417-0

- Biagi, B., Faggian, A., & McCann, P. (2011). Long and short distance migration in Italy: The role of economic, social and environmental characteristics. Spatial Economic Analysis, 6(1), 111–131. doi: 10.1080/17421772.2010.540035

- Buch, T., Hamann, S., Niebuhr, A., & Rossen, A. (2014). What makes cities attractive? The determinants of urban labour migration in Germany. Urban Studies, 51(9), 1960–1978. doi: 10.1177/0042098013499796

- Chen, Y., & Rosenthal, S. (2008). Local amenities and life-cycle migration: Do people move for jobs or fun? Journal of Urban Economics, 64(3), 519–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2008.05.005

- Clark, X., Hatton, T. J., & Williamson, J. G. (2007). Explaining U.S. immigration, 1971–1998. Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(2), 359–373. doi: 10.1162/rest.89.2.359

- Dietz, B. (2011). Immigrants from East Central Europe and post-Soviet countries in Germany (ENRI-East Research Report No. 16). Regensburg: Osteuropa-Institut. Retrieved from https://www.ios-regensburg.de/fileadmin/doc/ENRI_final_2011.pdf

- Eckey, H.-F., Kosfeld, R., & Türck, M. (2007). Regionale Entwicklung mit und ohne räumliche Spillover-Effekte. Review of Regional Research, 27(1), 23–42. doi: 10.1007/s10037-006-0007-y

- Etzo, I. (2011). The determinants of the recent interregional migration flows in Italy: A panel data analysis. Journal of Regional Science, 51(5), 948–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9787.2011.00730.x

- Florida, R. (2002). Bohemia and economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 2(1), 55–71. doi: 10.1093/jeg/2.1.55

- Geis, W., Übelmesser, S., & Werding, M. (2011). Why go to France or Germany, if you could as well go to the UK or the US? Selective features of immigration to the EU ‘big three’ and the United States. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 49(4), 767–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02154.x

- German Federal Employment Agency. (2013). Statistics of the German Federal Employment Agency – Employed persons subject to social security according to selected nationalities, German regions (NUTS-3). Data are from the German Federal Employment Agency upon request, Nuremberg 2013.

- Höhne, J., Linden, B., Seils, E., & Wiebel, E. (2014). Die Gastarbeiter – Geschichte und aktuelle soziale Lage (WSI Report No. 16). Düsseldorf: WSI - Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaftliches Institut. Retrieved from https://www.boeckler.de/pdf/p_wsi_report_16_2014.pdf

- Hönekopp, E. (1997). Labour migration to Germany from Central and Eastern Europe – Old and new trends (IAB Labour Market Research Topics No. 23). Nuremberg: Institute for Employment Research. Retrieved from http://doku.iab.de/topics/1997/topics23.pdf

- Isphording, I. E., & Otten, S. (2014). Linguistic barriers in the destination language acquisition of immigrants. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 105, 30–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2014.03.027

- Lerbs, O. W., & Oberst, C. A. (2014). Explaining the spatial variation in homeownership rates: Results for German regions. Regional Studies, 48(5), 844–865. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2012.685464

- Lewer, J. J., & Van den Berg, H. (2008). A gravity model of immigration. Economics Letters, 99(1), 164–167. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2007.06.019

- Mayda, A. M. (2010). International migration: A panel data analysis of the determinants of bilateral flows. Journal of Population Economics, 23(4), 1249–1274. doi: 10.1007/s00148-009-0251-x

- Niedomysl, T. (2011). How migration motives change over migration distance: Evidence on variation across socio-economic and demographic groups. Regional Studies, 45(6), 843–855. doi: 10.1080/00343401003614266

- Partridge, M. (2010). The duelling models: NEG vs amenity migration in explaining US engines of growth. Papers in Regional Science, 89(3), 513–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1435-5957.2010.00315.x

- Pedersen, P. J., Pytlikova, M., & Smith, N. (2008). Selection and network effects – Migration flows into OECD countries 1990–2000. European Economic Review, 52(7), 1160–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2007.12.002

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Ketterer, T. D. (2012). Do local amenities affect the appeal of regions in Europe for migrants? Journal of Regional Science, 52(4), 535–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9787.2012.00779.x

- Ruyssen, I., Everaert, G., & Rayp, G. (2014). Determinants and dynamics of migration to OECD countries in a three-dimensional panel framework. Empirical Economics, 46(1), 175–197. doi: 10.1007/s00181-012-0674-1

- Scott, A. J. (2010). Jobs or amenities? Destination choices of migrant engineers in the USA. Papers in Regional Science, 89(1), 43–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1435-5957.2009.00263.x

- Seifert, W. (2012). Geschichte der Zuwanderung nach Deutschland nach 1950. Bonn: Federal Agency for Civic Education (bpb). Retrieved from http://www.bpb.de/politik/grundfragen/deutsche-verhaeltnisse-eine-sozialkunde/138012/geschichte-der-zuwanderung-nach-deutschland-nach-1950?p=all

- Wang, Z., De Graff, T., & Nijkamp, P. (2016). Cultural diversity and cultural distance as choice determinants of migration destination. Spatial Economic Analysis, 11(2), 176–200. doi: 10.1080/17421772.2016.1102956

- Warchol-Schlottmann, M. (2001). Polonia in Germany. Samartian Review, 21(2), 786–792.