?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper analyzes the impact of the European Union's Cohesion Policy on firm growth in the programming period 2007–13 in seven European countries. Results show that Cohesion Policy support promotes firm growth in size (value added and employment) more than in productivity. However, even when the policy is the same and similar projects and beneficiaries are considered, its effectiveness varies across different territorial contexts, among but also within countries. In several cases, the impact of grants on firm growth is larger in regions with lower income or scant endowments of territorial assets, most likely because firms in those regions cannot rely on external assets.

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades a large body of literature has focused on the effectiveness of European Union (EU) Cohesion Policy (CP) and its impact on regional development, interpreted mainly in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and employment growth (e.g., Dall’erba & Fang, Citation2017; Gripaios, Bishop, Hart, & McVittie, Citation2008; Pieńkowski & Berkowitz, Citation2015). The evidence for an aggregate positive association between CP funding and economic prosperity, however, appears to be unstable across studies.

One reason explaining the divergence in the empirical findings is that regional policy implementation is characterized by (at least) two dimensions of heterogeneity. First, EU CP is a highly diversified programme of public intervention. It uses different funding schemes and targets various policy areas ranging from the provision of transportation and social infrastructure to the support of life-long learning schemes in businesses. It is likely that actions in different areas generate different effects on economic growth (Rodríguez-Pose & Fratesi, Citation2004). Second, although the principles of CP are the same across the entire EU, some recent papers (Fratesi, Citation2016; Rodríguez-Pose & Garcilazo, Citation2015) have shown that the way in which communitarian policies are implemented and their success depends on the context of implementation. This context can be defined by specific territorial assets with which EU regions are endowed (Crescenzi, Di Cataldo, & Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2016; Fratesi & Perucca, Citation2014, Citation2016).

In light of these considerations, the aim of this paper is to investigate the second dimension of heterogeneity, that is, the impact of CP in policy settings characterized by different territorial conditions. The analysis focuses on a specific kind of policy action, that is, financial support (co-funding of projects) for firms in the manufacturing sector during the programming period 2007–13. The choice of a narrow but particularly important part of the CP programme makes it possible to focus on the second dimension of heterogeneity and, therefore, to identify the ‘pure’ association between territorial characteristics and the policy impact. The focus on the programming period 2007–13 is interesting for three reasons: (1) the Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries benefited from communitarian support for the first time; (2) some recent works (Bachtrögler, Citation2016; Becker, Egger, & Von Ehrlich, Citation2018) warn about the deterioration in the effectiveness of CP in less developed regions during this period; and (3) with the 2007–13 programming period, the emphasis on competitiveness was reinforced, including the streamlining of a number of objectives into that of regional competitiveness and employment.

The theoretical framework employed for the identification of appropriate characteristics to describe the context of policy implementation is the concept of territorial capital, as defined by Camagni (Citation2009). This represents the set of elements that constitute the development potential of places. The European Commission (Citation2005) confirms that:

each region has a specific ‘territorial capital’ that is distinct from that of other areas and generates a higher return for specific kinds of investments than for others, since these are better suited to the area and use its assets and potential more effectively. (p. 1)

From a methodological point of view, the present study applies propensity score matching (PSM) techniques to analyze unique firm-level data assembled from three databases: a comprehensive database of EU projects and structural funds and Cohesion Fund beneficiaries in selected EU countries for the programming period 2007–13;Footnote1 a database with firm-level information for the period 2006–16; and a data set of territorial assets and characteristics for all European NUTS-2 regions in 2006.Footnote2 In the empirical analysis, the performance of the beneficiaries of CP support is assessed by considering the performance of comparable non-beneficiaries. Therefore, the hypothesis to be tested is that the impact of CP is not the same for supported firms located in different places, and in particular that the territorial characteristics of the EU NUTS-2 regions in which these firms are located mediate the impact of the EU support. In other words, the hypothesis states that the impact of being a beneficiary of CP on the respective firm’s economic performance is not expected to be uniform across manufacturing firms since the impact of the policy is also strongly related to the local context in which the firm operates.

Especially places with different levels of economic development and complementary local assets may experience different policy impacts, which raises the question of whether there is a trade off between the CP objectives of fostering cohesion and competitiveness. If the policy is more effective in poor regions or in those endowed with relatively scant growth assets that would enable a firm to increase productivity or maintain the volume of sales (firms located there are expected to be more in need of financial assistance), providing EU funds to firms in those regions will be in favour of both objectives. Contrarily, if the policy is more effective in regions endowed with relatively abundant growth assets, there will be a trade off between the goals of cohesion and competitiveness. This study shows that the former possibility turns out to be true in most cases.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section presents the theoretical framework, the related literature and the conceptual issues. The third section describes the empirical framework and statistical methods adopted in the paper, while the fourth section presents the data employed in the empirical analysis. The fifth section analyzes the results of the empirical analysis, comparing firm-level effects across and within countries with regard to regional characteristics. Finally, policy implications are discussed in the concluding section.

COHESION POLICY IN DIFFERENT PLACES AND IN THE CONTEXT OF DIFFERENT TERRITORIAL CHARACTERISTICS

The empirical findings of the broad stream of research focused on the evaluation of CP have not yet led to a shared agreement on the effectiveness of CP in promoting regional development. While some studies point to a positive effect of CP on regional economic growth (e.g., Dall’erba, Citation2005; Ramajo, Márquez, Hewings, & Salinas, Citation2008), others find no or limited evidence of such a relationship (e.g., Dall’erba & Le Gallo, Citation2008; Esposti & Bussoletti, Citation2008).

As indicated in the introduction, a large strand of the literature suggests that this lack of consistency among studies may be caused by two kinds of heterogeneity characterizing CP. First, CP may finance a broad variety of actions, some more focused on the economic return of investments, others on the achievement of progress in the social sphere. Second, CP is implemented in highly diversified territorial settings that may affect the outcome of the communitarian action.

Concerning the first issue, evidence supporting the assumption of a different impact of CP across axes of intervention was first provided by Rodríguez-Pose and Fratesi (Citation2004), who find different returns on four axes, of which only policies targeted at improving human capital provided significant and long-lasting returns. Similarly, in his analysis focused on Italy, Percoco (Citation2005) indicates that the best-performing regions were those that allocated CP funds according to the hierarchy of marginal productivities in different policy fields.

Regarding the second dimension of heterogeneity, some studies (e.g., Cappelen, Castellacci, Fagerberg, & Verspagen, Citation2003; Mohl & Hagen, Citation2010) define the local conditions assumed to affect the impact of CP in general terms, for example, as the overall regional level of development (and therefore the intensity of EU support). Findings show that the return on CP actions was higher in more developed regions. Further studies have addressed the same issue by interpreting regional policy settings as the combination of specific territorial conditions and assets expected to mediate the impact of CP. Ederveen, Groot, and Nahuis (Citation2006) stress the crucial importance of institutional quality as a factor in the explanation of CP effectiveness. Rodríguez-Pose and Garcilazo (Citation2015) and Crescenzi et al. (Citation2016) reach similar conclusions in empirical studies focused on specific CP areas of intervention. Other studies have analyzed many other different conditioning factors, that is, local characteristics explaining a differential impact of the policy, such as regional industrial structure (Cappelen et al., Citation2003; Percoco, Citation2017), regional settlement structure (Gagliardi & Percoco, Citation2017), territorial capital (Fratesi & Perucca, Citation2014, Citation2018b; Sotiriou & Tsiapa, Citation2015), human capital (Becker, Egger, & Von Ehrlich, Citation2013), or the alignment with the socioeconomic structure (Crescenzi, Citation2009).

The two dimensions of heterogeneity are actually not independent of each other for two reasons. First, the kind of policy undertaken in different regions is related to their territorial characteristics (Fratesi & Perucca, Citation2016). More specifically, lagging-behind regions tend to devote a larger share of funds to the provision of infrastructure, while more advanced regional economic systems focus more on matters such as the support of the productive environment and social policies. Second, the mediation effect of the territorial conditions is not expected to be the same for actions in different policy fields. In an empirical study on the EU-12 member states, for instance, Fratesi and Perucca (Citation2014) show that the territorial characteristics of regions are likely to foster the effectiveness of CP actions only in certain fields of intervention. Moreover, with a systemic analysis of regions of the EU-15 member states, they also show that regions obtain higher benefits when their CP investments target assets which are complementary to those present in the region (Fratesi & Perucca, Citation2018b).

The aim of the present paper is to study the effectiveness of CP in regions characterized by different territorial characteristics, that is, the second dimension of heterogeneity of CP. In order to limit the impact of the first dimension (the focus of CP on different policy fields) on the results, the analysis is restricted to the actions aimed at fostering the competitiveness of manufacturing firms, because support for manufacturing firms is generally targeted at increasing their competitiveness and sales (hence, by generating new jobs), while in other sectors (e.g., in public services or public administration) more diversified objectives may coexist. In some market and business services, funding is also expected to be principally aimed at fostering competitiveness, but the database does not allow for a clear-cut distinction between the different objectives of service sectors projects.

A FRAMEWORK FOR EVALUATING THE SAME POLICY IN DIFFERENT PLACES

This paper deals with the issue of a potentially heterogeneous impact of CP in different territorial settings. To be more precise, we want to test whether specific characteristics of the regions in which CP actions are undertaken reinforce or hamper the effectiveness of EU regional policy.

A potential source of bias in this kind of analysis stems from the likely association between the territorial settings and the kind of policy implemented. In order to avoid this issue, the empirical analysis adopts a firm-level perspective (instead of a regional one) allowing comparisons to be made between very similar interventions focused on comparable structural funds actions (projects) and actors (firms operating in the manufacturing sector) with the same economic goal (competitiveness or sales).

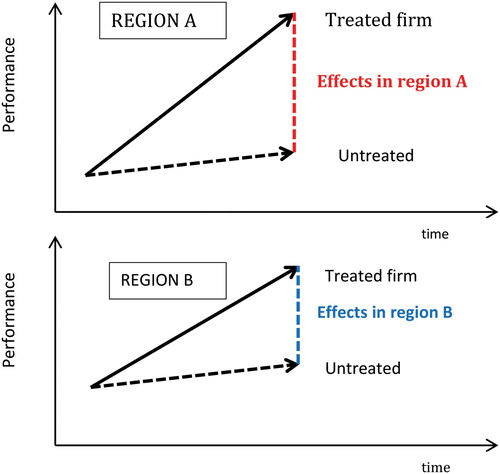

The conceptual framework adopted in the analysis is represented in . The purpose is to compare the effectiveness of CP funding in promoting firms’ performance in different contexts. This requires, as a starting point, the comparison of firms that have been treated by CP (i.e., benefited from CP funding) with those that have not been treated (i.e., are not beneficiaries of the structural funds or the Cohesion Fund), following a difference-in-difference approach. The effect of the policy in region A is depicted by the red dashed line in the upper part of , which compares the performance of a treated and an untreated firm. However, this paper argues that the effect of the treatment can differ from the one achieved in another region, say region B, characterized by different local conditions. In region B, the effects of the same policy may be lower or higher because of interactions between the policy and characteristics shaping the local context.

In order to test whether the policy effects vary in qualitative terms, in addition to their different (quantitative) extent, the firms’ performance analyzed in the paper is not restricted to one indicator. That is, the empirical analysis focuses on three different performance indicators of manufacturing firms, namely growth in value added, employment and productivity.

From a methodological perspective, the solution adopted to compare policies with a similar goal and firms with similar characteristics consists in using PSM together with a difference-in-difference approach. By that means, differences in the three outcome variables across similar treated and untreated firms are captured, whereby the probability of receiving the treatment (the propensity score), which depends on a set of firm characteristics, is considered in order to assess the similarity of firms before the treatment. The estimated average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) is then compared across different countries and territorial settings.

Regarding the measurement of territorial characteristics defining the local settings in NUTS-2 regions, for which the ATT is estimated and thus across which CP actions are compared, we apply the conceptual framework of ‘territorial capital’ (Camagni, Citation2009). The latter consists of all those characteristics deeply rooted in a territory that are expected to promote regional development. According to this approach, the regional territorial assets can be classified based on two dimensions: rivalry and materiality. These categories take into account that territorial assets of regions can be of very different nature, ranging from tangible and rival goods (such as private investments) to intangible and non-rival resources (such as rule of law and institutions), and can follow different laws of accumulation and depletion.Footnote3 The idea is that the effectiveness of investments (and therefore also of CP firm grants) may not be neutral to the territorial capital endowment of regions. If this holds true, as suggested by the literature discussed in the previous section, it is essential to investigate the possible occurrence of synergies and complementarities between EU actions and the current territorial assets characterizing each policy setting (in a region). The research question of this paper therefore is whether and to which extent the effects of the regional CP investments on supported manufacturing firms’ performance vary across different territorial settings. We formulate two alternative hypotheses to be tested, which are supplemented by the ‘null hypothesis’ (hypothesis 0) saying that there is no variation in the impact of CP across regions with different endowments of territorial assets:

Hypothesis 1: The impact of the policy is higher in regions more endowed with territorial assets that foster economic growth (growth assets). This may be the case because the policy action has synergies and complementarities with local assets, such that policies are more effective in improving firm performance when there are local conditions that facilitate firm operations.

Hypothesis 2: The impact of the policy is lower in regions more endowed with growth assets. The underlying reason may be that firms are more in need when operating in an environment with depleted territorial assets, or, put differently, firms may encounter important obstacles when operating in contexts where they find few territorial assets complementary to theirs and, as a consequence, cannot be competitive (or at a larger cost) without policy support.

It is also possible that hypothesis 1 holds for some countries and hypothesis 2 holds for others. And it is possible that all regions within a country (with a relatively high GDP) are endowed with sufficient complementary assets so that their firms can work independently; consequently, EU funds to businesses are similarly effective across regions (one indication for hypothesis 0 to hold). The empirical study of these hypotheses requires data that have very recently been made available and can be used to assess the firm-level impact of CP, as described in the next section.

A DATABASE COMBINING POLICY, FIRM AND TERRITORIAL CHARACTERISTICS

In this study, we use a recently compiled database of actual projects co-funded by structural funds and the Cohesion Fund in the multi-annual financial framework 2007–13 (for a detailed description of the data, see Bachtrögler, Hammer, Reuter, & Schwendinger, Citation2017). This database includes data on over 2 million projects corresponding to over 1 million single beneficiaries, that is, firms, institutions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), etc. in 25 EU member states collected from lists of beneficiaries published by managing authorities. The data on beneficiary entities have been matched with the ORBIS business database by the Bureau van Dijk (Ribeiro, Menghinello, & De Backer, Citation2010) in order to gain additional information on the beneficiaries of EU’s CP funds.

In this paper, we only consider firms operating in the manufacturing sector (NACE Rev. 2) to ensure the comparability of co-funded projects.Footnote4 We control for the subsectors of manufacturing in a robustness check in Appendix D in the supplemental data online. In total, the beneficiaries’ database contains 115,526 projects carried out by 63,808 firms in the manufacturing sector in 21 EU member states matched with ORBIS.Footnote5

In order to match treated with untreated firms, all manufacturing firms in the respective countries in ORBIS that are not identified as beneficiaries (and for which the required data are available) are considered as part of the control group. Merging the beneficiaries’ data with ORBIS entails losing observations as we cannot take into account firms for which no balance sheet or employment data are available both before and after the funding, or because the matching is not possible as ORBIS identification numbers have changed or firm names are not unique.Footnote6 Moreover, in line with the literature (e.g., Oberhofer, Citation2013), we exclude those firms for which consolidated accounts are reported in ORBIS. This is the case when firms are part of company groups and balance sheet data and other business information do not refer to the single entity, which would bias results.Footnote7

Since the aim of this paper is to compare firm-level effects of CP across European countries and NUTS-2 regions, we combine the firm-level data with the set of territorial characteristics of NUTS-2 regions. Therefore, it is necessary to reduce the sample. First, countries corresponding to only one NUTS-2 region are excluded, for example, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Second, firms for which no NUTS-2 information is available drop out. Finally, due to poor data availability of outcome and control variables in ORBIS, we skip countries with relatively small control groups to be sure of having a sufficiently numerous sample of untreated units. Therefore, the analysis includes seven countries: Czech Republic, Spain, France, Italy, Portugal, Romania and Slovakia.

The firm-level effects of EU CP are measured in terms of three outcome variables: (1) change in value added, that is, the log difference between the post- and pre-treatment values; (2) employment growth, that is, the log difference in the number of employees; and (3) the growth in productivity (measured in terms of value added per employee).Footnote8 In order to compare the effects across the same set of firms, we only consider firms for which all outcome variables can be calculated (as well as all variables needed for the PSM are available in ORBIS), that is, 17,201 treated firms.

The goal is to verify whether the policy impact on the outcomes is reinforced under specific characteristics of the policy implementation settings, that is, the regional endowment of territorial capital. In order to capture this heterogeneity, four indicators of different territorial capital elements are defined based on previous literature (Perucca, Citation2013):Footnote9

An indicator for public and hard territorial capital, proxied by the infrastructure endowment of regions (captured by the density of motorways; source: EUROSTAT).

An indicator for private and hard territorial capital, proxied by per capita private capital invested in the manufacturing sector in a region (source: Cambridge Econometrics database).

An indicator depicting public and soft territorial capital assets, proxied by an index of institutional quality of regions (source: Charron, Dijkstra, & Lapuente, Citation2014).

An indicator for private and soft territorial capital, modelled by the human capital endowment of regions as measured in terms of the regional population share that has attained tertiary education (International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) levels 5–6; source: EUROSTAT).

METHODOLOGY

The objective of the empirical analysis is, first, to verify whether having benefited from CP funding is associated with a better performance by manufacturing firms. Second, we test whether this association has the same strength and intensity in regions characterized by different territorial conditions.

In principle, we would like to compare the value of outcome variable Y of firm i as a beneficiary of CP support with the outcome at the same point in time if firm i had not been treated:(1)

(1) Intuitively, it is not possible to observe the outcome in both situations. Therefore, we need to find similar firms (before the treatment) that have not received CP funding in order to estimate the expected impact of the treatment (Ti = [0,1]) on the supported firm i’s performance (difference-in-difference estimation), which is defined as the ATT.

In order to make treated firms, that is, those that have carried out a co-funded project during the multi-annual financial framework (MFF) 2007–13, and non-treated firms comparable, we control for several characteristics. That is, the allocation of Structural Funds and the Cohesion Fund is not random but depends on the administrative region in which the firm is located, because, for example, less developed regions can distribute a relatively higher amount of CP funds to beneficiaries. Furthermore, depending on the funding scheme or priority (theme), funds assignment may be influenced by a set of pre-intervention characteristics of the firms, such as their size or industrial sector.

Thus, in the first stage of the empirical analysis, we apply PSM (Rosenbaum & Rubin, Citation1983), allowing one to match treated and untreated units on an estimated probability of treatment known as the ‘propensity score’. The propensity score is estimated using a logit regression model, where the objective variable (i.e., the dichotomous treatment variable Ti) is assumed to depend on a set of pre-treatment characteristics (w):(2)

(2) where F(.) denotes the logistic cumulative distribution function assumed, and the propensity score p can take on values from 0 to 1 (a probability of 100% for receiving funds).

The choice of the pre-treatment firm characteristics to be considered is crucial. Bondonio and Greenbaum (Citation2006) identify four main types of characteristics: (1) macro-business cycles that may affect the outcome of firms located within the same country; (2) economic conditions characterizing the local and regional settings at the firms’ location; (3) industry-specific market characteristics, which are common to all firms operating in that sector; and (4) further firm characteristics such as size or age.

The set w of pre-treatment characteristics defined in the present analysis comprises variables pertaining to each of the four conceptual categories summarized above. Country-specific fixed effects capture the heterogeneity of national business cycles in the period considered (1). A dummy equal to 1 if the NUTS-2 region in which the firm is located is a convergence region, that is, a region that is eligible for the convergence objective (former Objective 1, excluding phasing-out regions), in the programming period 2007–13 proxies the relative level of regional economic development and, indirectly, the extent of CP support (2). Sector-specific market conditions (3) do not pose any particular threats to the validity of the analysis, since our focus is restricted to manufacturing firms.Footnote10 Finally, a number of firm characteristics is assumed to be associated with the probability of receiving the treatment. Explicitly, the model includes the following control variables, both included in linear and quadratic terms:Footnote11 First, the (log of) initial employment, that is, the number of employees in 2006 or, if not available, in 2007. Second, (the log of) initial firm age measured as the years since the incorporation of the firm until 2007. Third, (the log of) initial capital intensity, that is, fixed assets (€ thousands) per employee in 2007. Fourth, the (log of) firms’ initial current ratio, that is, its current assets divided by its current liabilities, as an indicator of liquidity (in 2007).

In the second stage of the analysis, treated firms are matched with untreated controls based on the value of the propensity score and a kernel matching estimator. Using a kernel matching approach (Epanechnikov) implies that all non-treated firms are considered when forming the control group; however, firms with a propensity score that is closer to that of the treated ones are assigned a higher weight in the estimation of the ATT. Moreover, a limit for the maximum difference between propensity scores is implemented in the matching algorithm, and firms that cannot be matched considering that are excluded from the difference-in-difference estimation.Footnote12

Given the conditional independence assumption of outcomes (from the observables determining the probability of treatment), the causal effect (ATT) of CP assistance on the performance of treated firms is estimated by:

(3)

(3) Following Becker et al. (Citation2012) and Bernini and Pellegrini (Citation2011), the standard errors of the ATT are estimated using bootstrapping (1000 replications).

The econometric analysis is performed using three samples. The first comprises manufacturing firms in all countries in the data set in order to test for the whole sample whether the conditional difference in the outcomes, which is achieved by treated firms due to the CP funding, is significantly different from zero. The same analysis is then replicated separately for firms located in the same EU member state in order to verify whether the impact of the treatment is heterogeneous across countries. Finally, the third step is a comparative analysis of the ATT for firms within each country, which are located in regions characterized by different initial territorial conditions.

COHESION POLICY IMPACT IN DIFFERENT TERRITORIAL SETTINGS

The first step is to estimate the impact of CP in the whole sample of seven countries, thereby obtaining an overview on its effectiveness in enhancing firm growth. As presented in , results indicate that CP support has a significant effect on the performance of treated firms regarding all three outcome variables.

Table 1. Impact of Cohesion Policy on manufacturing firms in different countries (estimated average treatment effects on the treated).

Assisted firms outperform similar but unassisted firms by about 26 percentage points in terms of value added and employment growth over the time span of the multi-annual financial framework, 2007–13. Also, growth in value added per employee exceeds that of the control group, but in this case the coefficient is much lower, though statistically significant. This implies that the growth impact of CP on firms is larger in terms of size expansion than in terms of productivity gains, since treated firms outperform comparable ones in terms of significantly larger employment and value added growth in parallel, which also explains the smaller differences in terms of value added per employee.

Cohesion Policy impact in different countries

This pattern may not necessarily be the same across all countries that are part of the sample. It is possible that the firm-level effects in different countries are quantitatively or qualitatively distinct from each other due to administrative structures or the presence of different local assets. If the policy impact is different across countries, the analysis at a subnational level will necessarily have to be conducted country by country. Moreover, if firms in different countries gain differently from CP, it may be crucial to take this into account for the design of the EU’s post-2020 regional policy.

The lower panel of reports the estimation results for each country. As expected, the impact of CP varies across countries in both quantitative and qualitative terms. When inspecting the results for value added growth (the fourth column of ), it becomes evident that CP-treated firms in general face significantly higher growth rates than the respective control group. However, the extent to which this occurs is different, with the magnitude of the ATT being three times higher in Romania than in France. The result with regard to employment growth is similar, since it proves to be significantly higher in treated firms due to the financial assistance they received in all member states considered. Again, the size of the ATT varies. It is largest in Romania and smallest in Italy and Slovakia (the second panel of ).

The regression outcomes in terms of value added per employee are less straightforward and differ among countries. For the three Mediterranean ones in the sample (Italy, Spain and Portugal) and for Romania, the treatment of CP induces small additional increases in terms of labour productivity, whereas for the other countries (France, Czech Republic and Slovakia) this is not the case as the policy impact on productivity is not statistically significant (the third panel of ).

The results presented in suggest that, in some countries, CP assistance to firms makes them only grow in size (with parallel increases of employment and value added), while in others it also induces qualitative firm growth in terms of productivity. In general, the impact on growth appears to be quantitatively more important in countries with a relatively lower GDP, such as Romania and Portugal, which points to more effective CP in countries which are more in need of financial assistance.

Cohesion Policy impact in regions with different territorial characteristics

Having shown that CP has a heterogeneous impact on firm growth in different countries, the research question to be addressed in this subsection concerns the possibility of having also a differentiated impact across regions within the same country. As discussed above, we aim at verifying whether there are synergies and complementarities between CP actions and territorial capital assets of regions, that is, whether a region that is well endowed with growth assets faces a higher or lower ATT than other regions.

The estimation results are presented in , which reports the ATT coefficients for the three outcome variables in two territorial situations defined for each country, that is, one in which the territorial capital indicator is above and one in which it lies below the national average. For example, in the upper part of , we compare the impact of CP on treated firms’ performance among regions characterized by an endowment of public and hard territorial capital (measured in terms of motorway density) either above or below the respective country average.Footnote13 For each outcome variable (a percentage change in value added, employment and productivity), the third column contains the difference between the ATT for firms in regions endowed with above-average territorial capital and the ATT in regions with a lower endowment of the specific territorial capital asset relative to the national average. A t-test of the mean differences shows whether this difference is statistically significant (denoted with asterisks).

Table 2. Impact of Cohesion Policy on manufacturing firms in the presence of different territorial capital (TC) assets (estimated average treatment effects on the treated and differences).

Table 2. Continued

Recalling the two hypotheses defined above, on the one hand, a positive mean difference implies the validity of hypothesis 1, that is, the impact of the policy is higher in regions that are more endowed with growth assets. On the other, a negative difference between the means of the two groups confirms hypothesis 2, saying that the impact of the policy is lower in regions more endowed with the particular element of territorial capital.

Results reported in suggest that the relationship between territorial settings and the return of CP on firms’ performance does not systematically verify any of these hypotheses. In fact, the empirical findings point to an outcome of CP that is highly diversified not only across countries but also across different territorial settings within the same country.

The most frequent findings indicate a lower return of CP funding in regions characterized by an endowment of territorial capital above the country average, but this result differs depending on the asset and the country. Estimation results suggest significant differences within countries when considering growth in firms’ employment and value added. It is interesting to note that, for both outcomes, most significant mean differences are negative, meaning that firms located in regions more endowed with territorial capital, on average, tend to experience a lower impact of the policy than the others. Therefore, CP seems to promote convergence within countries, between less and more developed regions (which is reflected in hypothesis 2). However, when analyzing the impact on productivity, the number of statistically significant differences diminishes and, in case they are significant, these differences tend to be positive, suggesting some occurrences of a higher impact of CP funding on productivity in regions that are endowed with relatively much territorial capital.

Regarding the particular territorial assets, the infrastructure endowment of regions (a public and hard asset) does not seem to be crucial for the CP impact on treated firms’ value added or employment growth; however, it is positively linked to productivity growth in Slovakia and Portugal. In Portugal, this appears to be due to a slightly higher impact of CP on value added than on employment growth, while firms in Slovakia register a lower effect on employment growth. Thus, CP and the local policy settings in terms of infrastructure may be complementary in those countries.

Likewise, there does not seem to be a coherent relationship between ATTs on employment or value added growth and public and soft assets, measured by the perceived quality of regional institutions For productivity there are two significant differences across regions with distinct institutional quality, however, with opposite signs (Czech Republic and Slovakia). This weak association may appear to contrast with what was pointed out by Rodríguez-Pose and Garcilazo (Citation2015), who concluded that the impact of CP is higher in regions with better institutions. Their study, however, is focused on the impact of total regional cohesion expenditure on aggregate regional GDP and, compared with the present work, it therefore considers a variety of funding programmes and actions that are focused on various fields and not specifically on business support. As we restrict the analysis to individual firms’ performance in this paper, it may be an intuitive result that those assets that are directly employed in the production process might matter most.

When private assets are analyzed, the results clearly point to a larger need of policy support for firms operating in local environments that lack territorial capital. Regarding private capital invested in the manufacturing industry (the hard and private asset), the difference between ATTs is negative for value added and employment growth in several countries (France, Italy and Spain), which means that firms benefit more from CP support when there is relatively little private capital invested in the region. This is most likely the case as, without financial assistance via Structural Funds, they may not be able to access sufficient capital for expanding and improving production and sales processes.

The results for human capital (as a soft and private asset) provide further evidence for the second hypothesis (hypothesis 2) to hold, as the impact of CP on value added and employment growth tends to be larger in regions with a lower share of inhabitants with tertiary education. Again, this finding varies from country to country, whereby the difference in ATTs is relatively large in Italy and Spain. Interestingly, firms located in regions with relatively more human capital in Slovakia appear to be significantly more affected by CP in terms of productivity growth.Footnote14

Although the empirical evidence points to a confirmation of hypothesis 2, this is not true everywhere. In order to gain more insights, we focus specifically on the impact of CP on firms in regions with different levels of economic development, as measured by regional GDP per capita (before the treatment). There are two reasons for this, whereby one stems from a theoretical perspective and the other from an empirical one: the theoretical reason is that territorial capital assets are expected to influence the competitiveness of territories and, therefore, also their overall level of economic development. The empirical point is that this indicator is, as expected, correlated with all the four territorial capital indicators, while the four indicators might not always be correlated among themselves.Footnote15

The estimations performed for different groups of regions within countries according to their income level are presented in the last part of . It turns out that hypothesis 2 appears to be valid more often than hypothesis 1 as, in most cases, the policy impact on firm employment and value added growth is significantly higher in less developed regions. The differences are especially large in Romania, Italy and Spain, where firms in poorest regions receive a larger boost from CP. However, there are also regression results showing that the level of development of regions makes no difference for firm-level effects.

Concerning the impact on productivity, we do not find any significant difference in ATTs among regions,Footnote16 which can be explained by the fact that assisted firms in relatively poor regions tend to gain more from CP in terms of quantitative growth (in both value added and employment) than in terms of qualitative progress (productivity).

CONCLUSIONS: DIFFERENT IMPACTS IN DIFFERENT PLACES, BUT LIMITED TRADE-OFFS BETWEEN COHESION AND COMPETITIVENESS

This paper uses a novel data set to analyze the impact of CP support on the economic performance of manufacturing firms, which have actually received financial assistance during the programming period 2007–13, in seven EU member states. The results of the microeconometric evaluation show that the firm-level effectiveness of EU CP differs with regard to the outcome variable considered and, furthermore, substantially across European countries and different territorial contexts.

Regarding the use of different firm performance indicators, the analysis shows that the average treatment effect on supported (treated) firms (ATT) is relatively large in terms of boosting both value added and employment growth, which implies that treated firms grow more in size than the control group. However, the impact on qualitative growth (productivity) is smaller and, when comparing results across countries, not always significant. This finding may contribute to understanding why studies that evaluate CP on an aggregate, for example, regional, level have not come to a definite conclusion on CP effectiveness so far.

Another important finding of this study is that firm-level effects of CP are far from uniform across Europe, which may explain part of the diverse popularity and political support for the policy across countries. In order to be able to compare CP effects on firm performance among different territorial contexts, the paper considers grants to firms in the manufacturing sector, which is only a part of what CP does. Nevertheless, even in this case, the empirical analysis reveals heterogeneous outcomes (regarding the different performance indicators considered) across EU member states. We are not able to provide a causal analysis of the reasons for differences of ATTs among countries, which may stem from institutional, organizational or macroeconomic characteristics. However, estimation results suggest that the impact of CP grants tends to be larger in relatively poor countries (Romania in CEE and Portugal among the EU-15 member states), where firms may face harder conditions and, as a consequence, may be more in need of policy support.

The effects of CP support on firm performance do not only differ across countries. This paper shows that, furthermore, local specificities of the region in which a beneficiary is located matter for the impact (ATT) of CP firm grants on the supported firms’ performance. Regarding the regional endowment of territorial assets, public ones (infrastructure and institutional quality) tend to make little difference for the impact of firm support across regions, while the same firm assistance proves to be more effective in regions which are relatively poor in private assets (private investment in production processes and human capital) with respect to the country average. This indicates that in regions in which it is more difficult to gather private assets, firms are likely to be more in need of financial support than elsewhere, in order to grow in employment, value added and productivity.

Taking the overall economic development level of regions into account and investigating whether the impact of firm CP support is stronger in poorer or richer regions allows further important insights, also due to its repercussions on the cohesion/competitiveness debate. On the one hand, complementarities of the firm grant with local assets could make the policy impact stronger in richer regions; however, on the other hand, firms in poorer regions may benefit more from CP funds because they are more reliant on them. The prevailing of the former effect would imply the existence of a trade-off between the policy objectives of increasing cohesion and competitiveness, which would not occur when the latter effect prevails. The empirical analysis shows that, in most countries within the sample (most significantly in Spain, Italy and Romania), the impact on firm performance is stronger in poor regions, signalling that in most cases there is no trade-off arising.

The findings of this study have important normative consequences. First, firm-level effects of CP support are far from uniform as they are mediated by national and territorial differences which appear to be crucial in that context, also in the sense that the political support for the policies is likely to be different in different places. Second, CP assistance to firms seems to contribute significantly to firm expansion, while the impact on productivity appears to be rather limited.

Both of the latter results indicate important policy implications with regard to the reform of EU CP. The fact that supporting firms tends to be more effective in poorer countries, and poorer regions within countries, is an indication for sustaining the CP principle of concentration, that is, the focus on the less developed regions within the EU. From a researcher’s point of view, the fact that the impact of the same policy is not uniform across space still makes it necessary to conduct further studies to get a better understanding of the conditioning factors that determine the success of policy implementation. Moreover, the findings of this paper suggest that funding for regions or firms, in fact, should be targeted in light of the units’ particular characteristics and the expected impact at the same time.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (44.3 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful for valuable comments and suggestions made by three anonymous referees as well as the participants at numerous conferences, such as the European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Regional Studies Association (RSA) and Associazione Italiana di Scienze Regionali (AISRe) conferences in 2017, and of seminars at the Joint Research Centre as well as the University of Salerno. Moreover, they thank Guido Pellegrini for discussing the paper at ERSA 2017, as well Harald Oberhofer and Harald Badinger for their detailed feedback.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Julia Bachtrögler http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6312-3492

Ugo Fratesi http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0755-460X

Giovanni Perucca http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5582-1912

Notes

1. For the programming period 2007–13, the managing authorities of operational programmes were obliged to report the beneficiaries of CP funds for the first time.

2. NUTS = Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics.

3. We exclude the intermediate cases (intermediate levels of rivalry and materiality), which are difficult to measure and would make the analysis very complex and the results difficult to interpret in terms of policy implications.

4. NACE = Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community.

5. Croatia, Ireland, Luxembourg and Malta have no beneficiaries of EU Cohesion Policy that can be matched with ORBIS.

6. For most countries, the number of beneficiaries that we cannot consider due to this account for less than 5% of the total number of beneficiaries in the database. For Romania, the share of beneficiaries that can be compared with a control group amounts to only 32.4% due to firm data availability.

7. Kalemli-Ozcan, Sorensen, Villegas-Sanchez, Volosovych, and Yesiltas (Citation2015) discuss issues arising when working with ORBIS, which does not provide the full population of firms or perfect data coverage. We are aware of these issues, some of which cannot be controlled for, but believe that it is the best possible data set for this analysis and the matching exercise means a significant advancement compared with existing data sets.

8. We refer to 2007 as a pre-treatment observation in general; for employment, we also have 2006 ORBIS data and consider it as a pre-treatment value if available. The post-treatment value is measured in 2014 (integrated with 2015 or 2016 data when 2014 data were not reported).

9. Given the period of analysis, characterized by a large economic crisis (Fratesi & Perucca, Citation2018a), it would also have been interesting to test for other, more conjunctural indicators, for instance, access to credit in the different regions. To the best of our knowledge, however, these data are not available at the NUTS-2 level.

10. We control for the NACE Rev. 2 four-digit sub-industry code in a consistency check.

11. Regarding the choice of control variables, we take previous literature into account (Bernini & Pellegrini, Citation2011; De Zwaan & Merlevede, Citation2013; Oberhofer, Citation2013; Ribeiro et al., Citation2010).

12. Moreover, in all estimations the common support restriction is imposed. We check for the homogeneity of the characteristics of treated and untreated observations by comparing the distribution of pre-treatment observables across the matched and non-matched sample (more information on this is available from the authors upon request). In order to check whether outliers and the distribution of firm size and productivity among the treatment and control group bias the results, the results of several consistency checks are reported in Table D1 in Appendix D in the supplemental data online. They consist of running the estimations using specific subsamples that exclude potentially influential observations, that is, large or small firms in terms of their number of employees or high-productivity firms.

13. Table C1 in Appendix C in the supplemental data online reports the number of observations in each policy setting (for each group of regions).

14. This result may be driven by the small sample of treated firms in Slovakia (see Appendix C in the supplemental data online).

15. For a correlation matrix, see Table B1 in Appendix B in the supplemental data online.

16. Again, Slovakia is an exception, potentially due to its small number of observations.

REFERENCES

- Bachtrögler, J. (2016). On the effectiveness of EU Structural Funds during the Great Recession: Estimates from a heterogeneous local average treatment effects framework (Department of Economics Working Paper Series No. 230). Vienna: WU Vienna University of Economics and Business.

- Bachtrögler, J., Hammer, C., Reuter, W. H., & Schwendinger, F. (2017). Spotlight on the beneficiaries of EU regional funds: A new firm-level dataset (Department of Economics Working Paper Series No. 246). Vienna: WU Vienna University of Economics and Business.

- Becker, S. O., Egger, P. H., & Von Ehrlich, M. (2012). Too much of a good thing? On the growth effects of the EU’s regional policy. European Economic Review, 56(4), 648–668. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2012.03.001

- Becker, S. O., Egger, P. H., & Von Ehrlich, M. (2013). Absorptive capacity and the growth and investment effects of regional transfers: A regression discontinuity design with heterogeneous treatment effects. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 5(4), 29–77. doi: 10.1257/pol.5.4.29

- Becker, S. O., Egger, P. H., & Von Ehrlich, M. (2018). Effects of EU regional policy: 1989–2013. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 69, 143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2017.12.001

- Bernini, C., & Pellegrini, G. (2011). How are growth and productivity in private firms affected by public subsidy? Evidence from a regional policy. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 41(3), 253–265. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2011.01.005

- Bondonio, D., & Greenbaum, R. T. (2006). Do business investment incentives promote employment in declining areas? Evidence from EU Objective-2 regions. European Urban and Regional Studies, 13(3), 225–244. doi: 10.1177/0969776406065432

- Camagni, R. (2009). Territorial capital and regional development. In R. Capello, & P. Nijkamp (Eds.), Handbook of regional growth and development Theories (pp. 118–132). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Cappelen, A., Castellacci, F., Fagerberg, J., & Verspagen, B. (2003). The impact of EU regional support on growth and convergence in the European Union. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 41(4), 621–644. doi: 10.1111/1468-5965.00438

- Charron, N., Dijkstra, L., & Lapuente, V. (2014). Regional governance matters: Quality of government within European Union member states. Regional Studies, 48(1), 68–90. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2013.770141

- Crescenzi, R. (2009). Undermining the principle of concentration? European Union regional policy and the socio-economic disadvantage of European regions. Regional Studies, 43(1), 111–133. doi: 10.1080/00343400801932276

- Crescenzi, R., Di Cataldo, M., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2016). Government quality and the economic returns of transport infrastructure investment in European regions. Journal of Regional Science, 56(4), 555–582. doi: 10.1111/jors.12264

- Dall’erba, S. (2005). Distribution of regional income and regional funds in Europe 1989–1999: An exploratory spatial data analysis. Annals of Regional Science, 39(1), 121–148. doi: 10.1007/s00168-004-0199-4

- Dall’erba, S., & Fang, F. (2017). Meta-analysis of the impact of European Union Structural Funds on regional growth. Regional Studies, 51(6), 822–832. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1100285

- Dall’erba, S., & Le Gallo, J. (2008). Regional convergence and the impact of European Structural Funds 1989–1999: A spatial econometric analysis. Papers in Regional Science, 87(2), 219–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1435-5957.2008.00184.x

- De Zwaan, M., & Merlevede, B. (2013). Regional policy and firm productivity (European Trade Study Group (ETSG), Working Paper No. 377).

- Ederveen, S., Groot, H. L. F., & Nahuis, R. (2006). Fertile soil for Structural Funds? A panel data analysis of the conditional effectiveness of European Cohesion Policy. Kyklos, 59(1), 17–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6435.2006.00318.x

- Esposti, R., & Bussoletti, S. (2008). Impact of Objective 1 funds on regional growth convergence in the European Union: A panel-data approach. Regional Studies, 42(2), 159–173. doi: 10.1080/00343400601142753

- European Commission. (2005). Territorial state and perspectives of the European Union, Scoping document and summary of political messages (May). Brussels: European Commission.

- Fratesi, U. (2016). Impact assessment of EU Cohesion Policy: Theoretical and empirical issues. In S. Piattoni, & L. Polverari (Eds.), Handbook on Cohesion Policy in the EU (pp. 443–460). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Fratesi, U., & Perucca, G. (2014). Territorial capital and the effectiveness of cohesion policies: An Assessment for CEE regions. Investigaciones Regionales: Journal of Regional Research, 29, 165–191.

- Fratesi, U., & Perucca, G. (2016). Territorial capital and EU Cohesion Policy. In J. Bachtler, P. Berkowitz, S. Hardy, & T. Muravska (Eds.), EU Cohesion Policy: Reassessing performance and direction (pp. 255–270). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Fratesi, U., & Perucca, G. (2018a). Territorial capital and the resilience of European regions. Annals of Regional Science, 60(2), 241–264. doi: 10.1007/s00168-017-0828-3

- Fratesi, U., & Perucca, G. (2018b). EU regional development policy and territorial capital: A systemic approach. Papers in Regional Science. doi: 10.1111/pirs.12360

- Gagliardi, L., & Percoco, M. (2017). The impact of the European Cohesion Policy in urban and rural regions. Regional Studies, 51(6), 857–868. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2016.1179384

- Gripaios, P., Bishop, P., Hart, T., & McVittie, E. (2008). Analysing the impact of Objective 1 funding in Europe: A review. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 26, 499–524. doi: 10.1068/c64m

- Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Sorensen, B., Villegas-Sanchez, C., Volosovych, V., & Yesiltas, S. (2015). How to construct nationally representative firm level data from the ORBIS global database (Technical Report). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

- Mohl, P., & Hagen, T. (2010). Do EU Structural Funds promote regional growth? New evidence from various panel data approaches. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 40(5), 353–365. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2010.03.005

- Oberhofer, H. (2013). Employment effects of acquisitions: Evidence from acquired European firms. Review of Industrial Organization, 42(3), 345–363. doi: 10.1007/s11151-012-9353-9

- Percoco, M. (2005). The impact of Structural Funds on the Italian Mezzogiorno, 1994–1999. Région et Développement, 21, 141–152.

- Percoco, M. (2017). The impact of European Cohesion Policy on regional growth: Does local economic structure matter? Regional Studies, 51(6), 833–843. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2016.1213382

- Perucca, G. (2013). A redefinition of Italian macro-areas: The role of territorial capital. Rivista di Economia e Statistica del Territorio, 2, 37–65. doi: 10.3280/REST2013-002003

- Pieńkowski, J., & Berkowitz, P. (2015). Econometric assessments of Cohesion Policy growth effects: How to make them more relevant for policy makers? (European Commission Working Paper No. 02/2015). Brussels: European Commission.

- Ramajo, J., Márquez, M. A., Hewings, G. J. D., & Salinas, M. M. (2008). Spatial heterogeneity and interregional spillovers in the European Union: Do Cohesion Policies encourage convergence across regions? European Economic Review, 52(3), 551–567. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2007.05.006

- Ribeiro, S. P., Menghinello, S., & De Backer, K. (2010). The OECD ORBIS database: Responding to the need for firm-level micro-data in the OECD (OECD Statistics Working Papers No. 2010(1), 1). Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Fratesi, U. (2004). Between development and social policies: The impact of European Structural Funds in Objective 1 regions. Regional Studies, 38(1), 97–113. doi: 10.1080/00343400310001632226

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Garcilazo, E. (2015). Quality of government and the returns of investment: Examining the impact of Cohesion expenditure in European regions. Regional Studies, 49(8), 1274–1290. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1007933

- Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55. doi: 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41

- Sotiriou, A., & Tsiapa, M. (2015). The asymmetric influence of Structural Funds on regional growth in Greece. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 33(4), 863–881. doi: 10.1177/0263774X15603905