ABSTRACT

There is a research gap with respect to understanding the role of cultural attitudes in favour of entrepreneurial activity for actual start-up behaviour. The paper combines historical self-employment data with a psychological measure for entrepreneurial attitudes. The results reveal a positive relationship between the historical level of self-employment in a region and the presence of people with an entrepreneurial personality structure today. This measure is positively related not only to the level of new business formation but also to the amount of innovation activity.

INTRODUCTION

Several recent empirical studies have found pronounced persistence of regional levels of entrepreneurial activity over longer periods of time.Footnote1 In the case of Germany, Fritsch and Wyrwich (Citation2014, Citation2017, Citation2019) find that regions with higher levels of self-employment in the 1920s also have higher levels of new business formation today. The multiple disruptive shocks that impacted Germany in the period of these analyses clearly exclude an explanation that builds on persistence of the regional determinants of self-employment and new business formation. This paper argues and presents evidence showing that historical differences in self-employment may lead to the prevalence of cultural attitudes in favour of entrepreneurship that has a positive effect on rates of new firm formation today.

We extend earlier work (e.g., Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2014; Huggins & Thompson, Citation2017; Minniti, Citation2005) in several ways. First, we introduce a psychological measure of cultural attitudes in favour of entrepreneurship – the entrepreneurial personality fit of the today’s local population – and investigate its link to current levels of new business formation. Second, we analyze the two-stage relationship between historical entrepreneurship, the entrepreneurial personality fit of the local population, and the level of entrepreneurial activity today. Third, we examine the link between historical entrepreneurship, cultural attitudes in favour of entrepreneurship and innovation activity.

We find a significant positive relationship between the levels of historical self-employment in a region and the entrepreneurial personality fit of the local population. This indicates that areas with high historical levels of self-employment are marked by cultural attitudes in favour of entrepreneurship today. Based on this observation, we show that variation in the average entrepreneurial personality fit across regions that is due to historical differences in self-employment has a positive effect on current levels of new business formation. Moreover, our analyses reveal a similar two-stage link for innovation activity.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section overviews the relationship between historical roots of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship-facilitating local conditions. The third section introduces the empirical strategy. Results are reported in the fourth and fifth sections. The final section discusses limitations, offers conclusions and suggests avenues for further research.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Self-perpetuation of regional entrepreneurship and the emergence of cultural attitude

One important cultural driving force of entrepreneurship is the social legitimacy of entrepreneurs and their activities (Etzioni, Citation1987). Empirical research has revealed pronounced regional differences of this kind of social (Kibler, Kautonen, & Fink, Citation2014), as well as of the local public attitude to entrepreneurship (Westlund, Larsson, & Olsson, Citation2014). This social acceptance also implies a low stigma of failure and lower psychological costs (fear of failure) of starting a firm (e.g., Wyrwich, Stuetzer, & Sternberg, Citation2016, Citation2018). Variation in social acceptance of entrepreneurship is also the narrative for explaining differences in regional entrepreneurship in case study-based research (e.g., Chinitz, Citation1961; Saxenian, Citation1994).

The acceptance of entrepreneurship within a society can be regarded as part of the informal institutions of a community, which is defined as codes of conduct as well as norms and values (North, Citation1994). Informal institutions are the building blocks of ‘culture’. According to Williamson (Citation2000), culture belongs to the level of social structure that is deeply embedded in a population and that tends to change very slowly over long periods of time. Another element of an entrepreneurial culture is social capital such as the presence of entrepreneurship-facilitating network relationships (Westlund et al., Citation2014).

According to a widespread belief, there is a pronounced effect of the number of entrepreneurial role models in a region on the level of acceptance or legitimacy of entrepreneurship (Andersson & Koster, Citation2011; Arenius & Minniti, Citation2005; Minniti, Citation2005). The main idea behind this hypothesis is that an individual’s perception of entrepreneurship, his or her cognitive representation, is shaped by observing entrepreneurial role models in his or her social environment. This supposedly enhances the social acceptance of entrepreneurial lifestyles, boosts entrepreneurial self-efficacy beliefs and increases the propensity of adopting entrepreneurial behaviour. Furthermore, entrepreneurs in the local environment provide opportunities to observe and learn about entrepreneurial tasks (e.g., Bosma, Hessels, Schutjens, van Praag, & Verheul, Citation2012; Minniti, Citation2005; Nanda & Sørenson, Citation2010). Observing successful entrepreneurs provides potential entrepreneurs with examples of how to organize resources and activities and can lead to increased self-confidence in the sense of ‘if they can do it, I can, too’ (Sorenson & Audia, Citation2000, p. 443).

In this way, factual entrepreneurship, that is, visible entrepreneurial activity in a region, creates a perceptual non-pecuniary externality that spurs additional start-up activity and makes entrepreneurship self-reinforcing. Furthermore, individuals who observe successful entrepreneurs among their peers may perceive entrepreneurship as a favourable career option (for a detailed exposition of this argument, see Fornahl, Citation2003). Hence, people in regions characterized by a widespread positive attitude towards entrepreneurial activities may be more likely to perceive entrepreneurship as a viable career option and to start their own business. A self-perpetuating effect of high levels of new business formation in a region stems from the fact that most new ventures remain rather small (Schindele & Weyh, Citation2011). Hence, high levels of start-ups in a region lead to large shares of small business employment and a high density of entrepreneurial role models. Since small firms have been found to be a fertile seedbed for future entrepreneurs, large shares of small business employment due to high levels of new business formation today may lead to correspondingly high levels of entrepreneurship in the future (Elfenbein, Hamilton, & Zenger, Citation2010; Parker, Citation2009).

A further self-perpetuating effect of high levels of new business formation in a region can emerge if the newcomers create additional entrepreneurial opportunities that induce further start-ups. Empirical evidence suggests that persistence of start-up rates is stronger in high-entrepreneurship areas (Andersson & Koster, Citation2011; Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2014). This suggests that new business formation and entrepreneurial role models accelerate future entrepreneurship, particularly in areas with high levels of entrepreneurship due to the aforementioned mechanisms of self-perpetuation.

Minniti (Citation2005) provides a theoretical model that, based on the above-mentioned regional role-model effects, explains why regions with initially similar characteristics may end up with different levels of entrepreneurial activity. In this model, chance events at the outset of such a process may induce entrepreneurial choice among individuals that leads to different levels of regional entrepreneurship. In historical terms, one could also think of certain natural conditions and institutional shocks that influence the emergence of entrepreneurship (Sorenson, Citation2017). The presence of entrepreneurial role models in the social environment reduces ambiguity for potential entrepreneurs and may help them acquire necessary information and entrepreneurial skills. In Minniti’s model, this self-reinforcing effect of entrepreneurship depends critically on the ability of individuals ‘to observe someone else’s behaviour and the consequences of it’ (Minniti, Citation2005, p. 5). Another mechanism contributing to self-perpetuation of regional levels of new business formation and self-employment is intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurial values (e.g., Laspita, Breugst, Heblich, & Patzelt, Citation2012; Niittykangas & Tervo, Citation2005).

Based on the mechanisms described above, past entrepreneurship fosters the self-perpetuation of entrepreneurship via promoting cultural attitudes among the local population, which are more predisposing to entrepreneurship.Footnote2 Such attitudes can be also regarded a proxy for the prevalence of entrepreneurship-facilitating regional conditions.

The personality profile as an element of an entrepreneurial culture

Adapting a famous phrase from Hofstede, Beugelsdijk (Citation2007, p. 190) talks about ‘a positive collective programming of the mind’ in favour of entrepreneurship within a certain population. Other researchers refer to an aggregate psychological trait in favour of entrepreneurial activity (Freytag & Thurik, Citation2007). This can be regarded as entrepreneurship-facilitating personality characteristics among the population (see also Davidsson, Citation1995; Davidsson & Wiklund, Citation1997). This conceptualization follows the logic of a trait psychology approach to culture (Hofstede & McCrae, Citation2004; McCrae, Citation2001). This approach has delivered promising and replicated results in entrepreneurship research concerned with the origin and effects of regional differences in entrepreneurship (Obschonka, Schmitt-Rodermund, Silbereisen, Gosling, & Potter, Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2016; Stuetzer et al., Citation2016, Citation2017). In essence, there are certain psychological traits that are positively related to cultural attitudes, which are predisposing entrepreneurial behaviour (Huggins & Thompson, Citation2017).

At the individual level, research often reveals that entrepreneurs score relatively high on the Big Five personality traits ‘extraversion’, ‘conscientiousness’ and ‘openness’ but score relatively low on ‘agreeableness’ and ‘neuroticism’ (Caliendo, Fossen, & Kritikos, Citation2014; John, Naumann, & Soto, Citation2008; Zhao & Seibert, Citation2006). Combining these five traits into an entrepreneurial profile index leads to an intra-individual entrepreneurial Big Five profile (entrepreneurial constellation of Big Five traits within the individual) that indeed predicts entrepreneurial skill growth, motivation, self-identity, intention and behaviour at the individual level (Obschonka & Stuetzer, Citation2017; Schmitt-Rodermund, Citation2004). Thus, the share of people with an entrepreneurship-prone personality profile in the regional population or the deviation of the population’s average personality profile from an ideal entrepreneurial personality structure is a proxy for psychological traits that are positively related to entrepreneurship-facilitating cultural attitudes.

According to Rentfrow, Gosling, and Potter’s (Citation2008) theory on the emergence, persistence and expression of regional personality profiles, regional differences in the share of people with an entrepreneurial mindset today may be explained by social influence within the region as people respond, adapt to or become socialized according to regional norms, attitudes and beliefs. This suggests that the role model and peer mechanisms of self-perpetuation of entrepreneurship described in the previous section imply that regions with a high level of entrepreneurship in the past should have a stronger prevalence of people with an entrepreneurship-facilitating personality. Furthermore, people with an entrepreneurial mindset may tend to migrate to places where the local population has similar personality characteristics or where they find better framework conditions and opportunities for entrepreneurial endeavours (see also Obschonka et al., Citation2013, Citation2015).

Entrepreneurship research on the cultural dimension of entrepreneurship has mainly focussed on broad cultural values and dimensions with mixed and often disappointingly inconsistent results (Hayton & Cacciotti, Citation2013). The personality approach based on aggregate regional values in the entrepreneurial personality profile has several advantages. It builds on the established trait psychology approach (Hofstede & McCrae, Citation2004; McCrae, Citation2001). This approach finds considerable empirical support by individual-level research regarding the effect of such personality profiles, as well as by results at an aggregate regional level, that have indicated regional variations of personality differences in general (Bleidorn et al., Citation2016; Rentfrow et al., Citation2008; Talhelm et al., Citation2014).

A personality-based approach to entrepreneurship can help solve (or at least investigate) some of the most pressing questions in regional entrepreneurship research and practice such as the reasons for the persistence of regional variation in entrepreneurial activity (Huggins & Thompson, Citation2017; Obschonka et al., Citation2013) or different regions’ reactions during and after major economic crises (Obschonka et al., Citation2016). At the regional level of aggregate values of individual personality scores, research found a similarly robust link between regional variation in this entrepreneurial personality profile and regional variation in regional entrepreneurial activity (Obschonka et al., Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2016).

Hypotheses

We argued that past self-employment fosters the self-perpetuation of entrepreneurship by triggering cultural attitudes among the local population that are conducive to entrepreneurial activity. Furthermore, the prevalence of such attitudes should be strongly correlated with a high share of people with an entrepreneurship-prone personality profile. Thus, historical self-employment rates should be positively related to the prevalence of people with such a personality structure today. In a second step, the presence of such people should be positively linked to entrepreneurial activity today. If this two-stage relationship holds, this indicates that the presence of cultural attitudes in favour of entrepreneurship is behind the well-established empirical regularity that past entrepreneurship has a positive long-run effect on current entrepreneurial rates.

Finally, entrepreneurship in its very core includes behaviours such as creativity, recognition of opportunities, taking initiative, readiness to assume risk and introducing new ideas, products and services to the market. These behavioural elements are not only conducive to setting up one’s own business but also should be particularly relevant for innovation activity – the process of transforming new ideas and knowledge into concrete products and services that are accepted in the marketplace. Thus, the relationship between historical self-employment and the regional share of people with an entrepreneurship-prone personality file should also positively affect innovation activity.

DATA AND MEASUREMENT

Historical and current levels of entrepreneurship

The indicator for the historical level of entrepreneurship is the number of self-employed persons in the private sector divided by the total regional labour force. We use two definitions of the self-employment rate in 1925. Per the first definition, we exclude self-employment in agriculture as well as homeworkers (Heimgewerbetreibende). Homeworkers are omitted in this first definition because homework can be regarded as a rather marginal form of self-employment, one that is often characterized by strong economic dependence on a single customer. We consider it unlikely that this group of self-employed people and self-employment in agriculture represents the ‘nucleus’ that drives the self-perpetuation of entrepreneurship over time (for details, see Appendix B in the supplemental data online). We test this conjecture by employing a self-employment rate in 1925 that only comprises homeworkers and self-employed in agriculture in the denominator.

We also include a measure for science-based historical self-employment. This is the number of self-employed in certain industries that may be regarded as being reliant on academic knowledgeFootnote3 divided by the workforce. The rationale behind this strategy is to have an indicator that disentangles high-quality entrepreneurship which could be a particularly important source for the self-perpetuation of entrepreneurship in line with our arguments presented in section 2.

The historical data are derived from a full-sample census conducted in 1925 (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, Citation1927). These historical data include detailed information on the number of employees broken down by gender, industry (26 industries) and ‘social status’ at the level of counties (kleinere Verwaltungsbezirke). The variable social status distinguishes between blue-collar workers, white-collar employees, self-employed people, homeworkers and helping family members.

Although the definition of administrative districts at that time was considerably different from what is defined as an administrative district today, it is nevertheless possible to assign the historical districts to current planning regions. The spatial framework of our analysis is comprised of the 92 planning regions of Germany,Footnote4 which represent functionally integrated spatial units comparable with labour-market areas in the United States. If a historical district falls within two or more current planning regions, we assign employment to the respective planning regions based on each region’s share of the geographical area.

The information on current levels of new business formation are from the Enterprise Panel of the Center for European Economic Research (ZEW-Mannheim). These data are based on information from the largest German credit-rating agency (Creditreform). As in the case of many other data sources on start-ups, these data may not have complete coverage of solo entrepreneurs. However, once a firm is registered, hires employees, requests a bank loan or conducts reasonable economic activities, even as a solo entrepreneur, it is included, and its information is gathered starting from the date the firm was established. Hence, many solo entrepreneurs are captured along with the business founding date. This information is limited to the set-up of a firm’s headquarters and does not include the foundation of branches. Based on these criteria, solo entrepreneurs who are not covered are likely to be of low economic significance or set up primarily out of necessity and therefore not suitable for our analysis since it is unlikely that necessity-driven entrepreneurship is promoted by the long-term self-perpetuation mechanisms described in the second section. In our empirical analysis, we use the average annual number of start-ups formed between 2000 and 2016 per population in working age (in 10,000s) as the main outcome variable.Footnote5

The self-employment rate in 1925 measures the share of entrepreneurial role models within the total regional labour force, thereby reflecting how widespread self-employment was at the time. In line with our conceptualization above, we do not regard the historical self-employment rate as such to be a measure of culture. We rather argue that any effect of the historical self-employment rate on current entrepreneurship indicates the prevalence of cultural attitudes in favour of entrepreneurship. The reason behind this train of thought is that Germany faced severe historical shocks over the course of the 20th century. We argue that these numerous disruptive shocks largely rule out that persistence of entrepreneurship is driven by persistence of structural determinants of entrepreneurship. Thus, only the alternative channel behind persistence, namely the local prevalence of entrepreneurship-facilitating attitudes remains as a plausible explanatory factor of persistence (for details, see Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2017). A measure that should be positively related with such attitudes, which we employ in the data set is, the average entrepreneurial personality profile of the local population. In the following section, we describe how we measure this profile empirically.

The entrepreneurial personality profile

In line with earlier research on the entrepreneurial personality profile, we construct an overall indicator for an entrepreneurial personality fit based on the Big Five personality traits measured at the individual level (Obschonka & Stuetzer, Citation2017). We use German data from the global Gosling–Potter Internet project, which collects personality data in a number of countries (http://www.outofservice.com; see Rentfrow et al., Citation2008, for details). Respondents indicated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with 44 statements using a five-point Likert-style rating scale. The database for Germany consists of 73,756 respondents between 2003 and 2015 (Fritsch et al., Citation2018; Obschonka, Stuetzer, Rentfrow, Potter, & Gosling, Citation2017, Citation2018). Individual respondents were allocated to a planning region based on their current residence, specifically using their ZIP code. The sample can be regarded as representative for the German population (for details, see Appendix A in the supplemental data online).

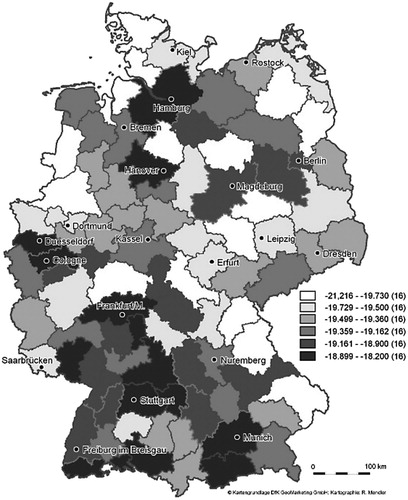

Our indicator for an entrepreneurial personality profile measures the deviation from the statistical reference profile of an entrepreneurial personality structure (highest scores on extraversion, conscientiousness and openness; lowest scores on agreeableness and neuroticism). This fixed reference profile is determined by the outer limits of the single Big Five traits within an entrepreneurial personality structure (Obschonka & Stuetzer, Citation2017). The individual-level entrepreneurial personality fit is the sum of the squared deviations of the individual Big Five scores from this reference profile (Cronbach & Gleser’s, Citation1953, D2 measure). The individual values on the profile are then aggregated to the regional level (average score based on respondents’ current residence) to achieve the regional value. This index has a mean of 19.39 (standard deviation = 0.563) across German planning regions. shows that there are quite considerable differences in the population’s entrepreneurial personality profile across the German planning regions (see Fritsch et al., Citation2018, and Figure A1 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online for a more detailed presentation).

Measures of innovation activity

We use two measures for current regional innovation activity in our analyses: the number of patents per population in working age (in 10,000s) and the share of research and development (R&D) employees. Patents are taken from the regional patent database (REGPAT) and are assigned to the region in which the inventor claims his or her residence. We have access to information for the period 2000–12. If a patent has more than one inventor, the count is divided by the number of inventors, and each inventor is assigned his or her share of the patent. Data on the share of R&D employees are from German Employment Statistics, which cover all employees subject to compulsory social insurance contributions (Spengler, Citation2008). R&D employees are defined as those with tertiary degrees working as engineers or natural scientists. We have access to information for the period 2000–14.

Further information is from different sources, particularly the 1925 Census and other publications from the Statistical Offices. Our indicator for the historical regional knowledge base is the presence of higher education institutions that existed already in the 19th century. We distinguish between ‘classical’ universities, technical universities and higher commercial schools (Hoehere Gewerbeschulen).Footnote6 We form three distance-based measures indicating the minimum distance to a region hosting a classical university or technical university. We also consider higher commercial schools. The indicator is set to zero if the region hosted a respective higher education institution. Classical universities, technical universities and higher commercial schools represent the regional knowledge base, which, according to the knowledge-spillover theory of entrepreneurship (Acs, Braunerhjelm, Audretsch, & Carlsson, Citation2009), may stimulate regional new business formation. Since knowledge is typically regionally bounded, distance to these historical knowledge centres should matter.

Controls

Because German federal states are an important level of policy-making, we include dummy variables for federal states in all models to control for their influence. Population density, in turn, is supposed to account for a variety of factors such as agglomeration economies, wages and land prices, which are closely correlated with population density.

The employment share of manufacturing controls for the sectoral structure of the regional economy. For these variables, we use the values for 1925 in the main models and not a more current period in order to minimize concerns that these controls could directly influence the level of new business formation in the period 2000–16. We also provide robustness checks with current controls. However, it should be noted that most of the historical control variables show high correlations with current values (Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2018). Table A1 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online summarizes the definition of variables; Table A2 provides descriptive statistics; and Table A3 shows correlations between variables.

RESULTS

Historical self-employment, entrepreneurial personality profile and new business formation today

Comparing the historical self-employment rate without including agriculture and homework to the regional level of new business formation in the period 2000–16 reveals a pronounced positive relationship (, columns I and II).Footnote7 The self-employment rate in science-based industries is also positively related to the overall level of new business formation today (, column III).

Table 1. Relationship between the self-employment rate (SER) in 1925, the entrepreneurial personality fit of today’s population and current new firm formation (ordinary least squares (OLS) regression).

The relationship between current levels of new business formation and the share of homeworkers and self-employed people in agriculture in 1925 is, however, negative (, columns V and VI). These different results for the two versions of the self-employment rate clearly indicate that homeworkers and self-employed in agriculture are not relevant for the self-perpetuation of entrepreneurship. The reason for the non-significance of homeworkers could be that most of them were more or less dependent on a single main customer and did not perform many of the tasks, such as marketing, management etc., that characterize entrepreneurship. The non-significance of historical self-employment in agriculture confirms the preconceived notion that farm owners make up a rather special case with regard to their business model, as well as their qualifications and abilities, that differs considerably from entrepreneurship in other sectors.

In line with findings documented in previous research (Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2014, Citation2017), we find that the positive relationship between the narrowly defined self-employment rates and current levels of new business formation is rather robust if a number of controls are included (, columns II and IV). In contrast, the historical self-employment rate for farmers and homeworkers is negatively related to new business formation (, column VI).

Comparing the self-employment rate that excludes agriculture and homeworkers in 1925 with the entrepreneurial personality fit of today’s population, we find a significantly positive relationship even when a set of control variables is included. A similar pattern is found for the self-employment rate in science-based industries. There is no statistically significant relationship between the historical level of homeworking and self-employment in agriculture and the entrepreneurial personality fit (, columns VII–XII). This result clearly indicates that the historical level of self-employment excluding agriculture and homework is not promoting an entrepreneurship-facilitating mindset among the local population in the sense of an aggregate psychological trait of today’s population. There is no robust relationship between the control variables, new business formation and the entrepreneurial personality fit. Finally, we also find that the entrepreneurial personality fit of the local population is positively related to the start-up rate (, columns XIII and XIV). The results for our main variables of interest are not affected by including historical controls. Thus, any potential multicollinearity between historical levels of self-employment and the historical controls is no issue.Footnote8

Historical self-employment, entrepreneurial personality profile and innovation activity today

We use the share of R&D employees in the regional workforce and number of patents per member of the working population as outcome variables reflecting regional innovation activity today. We regress these measures on historical self-employment rates and on the entrepreneurial personality structure today.

The results of show a clear statistically significant relationship between the historical self-employment rate and our two measures of regional innovation activity when no regional controls are considered (, columns I, III, V and VII). This relationship becomes, however, insignificant for R&D employment when regional controls are included (, columns II and IV) and it is only weakly significant for patenting when the general historical self-employment rate is employed (, column VI).Footnote9

Table 2. Relationship between the self-employment rate (SER) in 1925, entrepreneurial personality fit and innovation activity today (ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions).

Taking the entrepreneurial personality fit, we also find a positive and statistically significant relationship with current innovation activities. In the case of the share of R&D employment, regional differences in the entrepreneurial personality structure do not remain statistically significant when the controls for regional conditions are added (, columns IX–XII).

We find a negative relationship between geographical distance to a technical university that already existed before 1900 and today’s innovation activity. Distance to a classical university has a somewhat weaker negative effect on R&D employment. It also has a less pronounced negative relationship with patenting. These results suggest there is also persistence in the regional presence of relatively high levels of innovation activity. Historical population density is positively related to R&D employment today and there is a positive relationship between the employment share in manufacturing in 1925 with both measures of current innovation activities (see Tables A6 and A7 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online).

Instrumental variable approach

Based on the findings of and as well as the two-stage relationship proposed in the conceptual part of the paper (in the second section), we transform the analysis into a two-stage least square instrumental variable approach (2SLS IV) where the historical self-employment rate is taken as an instrument for the share of people with an entrepreneurship-prone personality profile. In the second stage, the variation in the local personality structure that is due to historical differences in entrepreneurship is used to explain regional differences in new business formation today (, columns I–IV) (for a similar application, see Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2017).Footnote10 Since historical self-employment in agriculture and homework is also never statistically significant in our further analyses, we do not present the results for this group.Footnote11

Table 3. Relationship between the self-employment rate (SER) in 1925, the entrepreneurial personality fit of today’s population and start-up rates/innovation activities today: two-stage least squares (2SLS) instrumental variables (IV) regressions (second stage).a

The estimates of the 2SLS IV approach confirm the ordinary least squares (OLS) analysis. In essence, the entrepreneurial personality profile of a region that is due to historical differences in entrepreneurship is positively related to current levels of new business formation. Assessing the first-stage F-statistics reveals that the relationship is more pronounced for science-based historical entrepreneurship.Footnote12

As for new firm formation, we transform the analysis into a 2SLS IV estimation approach (, columns V–VIII). The only difference is that our measures for innovation activities are the dependent variables in the second stage of the estimation. We also restrict the analysis to models with historical science-based entrepreneurship as an instrument for the entrepreneurial personality fit because we showed in the previous section that the first-stage F-statistics for the relevance of non-science-based self-employment as an instrument are much weaker.

Applying our two-stage estimation procedure reveals that there is a positive effect of the entrepreneurship-prone personality profile on patenting activity but no significant relationship with the share of R&D employment. We cautiously interpret this finding as evidence that the relationship between the entrepreneurship-prone personality profile and innovation activity is more robust for innovation output (patents) than for innovation input (share of R&D employees).Footnote13

We conducted several robustness checks and falsification tests. First, we used the employment share of science-based industries as an instrument to test whether it is the general presence of such industries rather than science-based entrepreneurship that is behind the two-stage relationship that we revealed in the main analysis. The analysis shows that there is no meaningful relationship for entrepreneurship today when using the employment share in science-based industries. Thus, it is entrepreneurship in science-based industries in general that matter. For innovation activity, there is also a significant first-stage relationship for the employment share in science-based industries which is, however, much smaller than for science-based entrepreneurship in the case of patenting activity. We also employed lagged historical controls for industry structure and population density from a full census conducted in 1907 (Statistik des Deutschen Reichs, Citation1909).

Finally, instead of historical regional conditions, we considered controls for current population density, industry structure and the regional knowledge base which is captured by the employment share of R&D employees. The latter model is also a reasonable approach of controlling for how the disruptive shocks that Germany faced in the 20th century and the development in the aftermath of these shocks imprinted regional conditions for entrepreneurship.Footnote14 Our two-stage relationship is not affected by this model adjustment (see Table A10 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online for robustness checks).

CONCLUSIONS

Our investigation has led to several interesting results. First, self-employment in agriculture as well as marginal forms of self-employment such as homework do not have a lasting effect on entrepreneurship and on our measure for cultural attitudes in favour of entrepreneurship. Second, the higher the level of historical self-employment in a region, the more pronounced the entrepreneurial personality fit of today’s population is. Third, regions with higher levels of historical self-employment and a more pronounced entrepreneurial personality fit of the population have higher levels of innovation activity that may be an important driver of future growth. The second and third findings are particularly pronounced for past science-based entrepreneurship.

A main conclusion that can be drawn from these results is that regional differences in the entrepreneurial personality fit, new business formation and innovative activities today have historical roots. We argued that the entrepreneurial personality fit of the local population is triggered by the entrepreneurial tradition of places due to local role-modelling processes that enhance the social acceptance of entrepreneurship that was transmitted across generations. This transmission mechanism warrants in-depth exploration in future research. It is, for example, unclear to what extent such a transmission has been impaired by disruptive external shocks, such as the devastating Second World War and 40 years of a socialist regime in East Germany. We also lack data on historic cultural aspects that could affect this transmission process and entrepreneurship in general. Another factor that needs further analysis in this regard is the geographical mobility of people. Do people with an entrepreneurial mindset show a tendency to migrate to regions with a pronounced entrepreneurship-promoting environment?

In this paper, we were also silent on the sources of historical self-employment rates. Future research should particularly investigate the role of exogenous natural conditions (e.g., location fundamentals, quality of soil, access to natural resources) for the emergence of entrepreneurship. A potential complex multi-stage relationship to be analyzed is the interplay of natural conditions and the emergence of entrepreneurship in the past that, in turn, triggers cultural attitudes regarding entrepreneurship and ultimately determine the level of entrepreneurship today. This assessment is beyond the scope of this paper. In the current paper, our intention was to establish in the first place that the mechanism behind the link between historical and current entrepreneurship is the prevalence of cultural attitudes in favour of entrepreneurship in areas with pronounced entrepreneurial tradition.

Apart from natural conditions there might be further historical factors that determined the emergence and persistence of entrepreneurship (e.g., quasi-exogenous institutional shocks). Learning about the factors that engendered the emergence of entrepreneurship and an entrepreneurship-facilitating environment may be particularly helpful when it comes to developing policies for regions in which this is absent.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (526 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Michael Fritsch http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0337-4182

Martin Obschonka http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0853-7166

Michael Wyrwich http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7746-694X

Notes

1. Andersson and Koster (Citation2011) for Sweden; Fotopoulos (Citation2014) and Fotopoulos and Storey (Citation2017) for the UK; and Glaeser, Kerr, and Kerr (Citation2015) for US cities.

2. Such regions are likely to have an infrastructure of supporting services, particularly good availability of competent consulting as well as appropriate financial institutions.

3. We classified machine, apparatus, and vehicle construction, electrical engineering, precision mechanics, optics, chemicals, as well as rubber and asbestos as science based.

4. There are 96 German planning regions. The cities of Hamburg and Bremen are defined as planning regions even though they are not functional economic units. To avoid distortions, we merged these cities with adjacent planning regions. Further, we exclude the ‘Saarland’ since most of its area was not under German administration in 1925. The small sample size is a limitation of the analysis.

5. On average, the ZEW data record approximately 214,000 new businesses per year over the period 2000–13. A total of 82% of start-ups are in the service sector, while only 5% are in manufacturing (Bersch, Gottschalk, Müller, & Niefert, Citation2014). For the regional distribution of start-ups in 2000–16, see Figure A2 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online.

6. For details about the role of different types of higher education institutions for (persistent) entrepreneurship and innovation, see Fritsch and Wyrwich (Citation2018).

7. The correlation coefficient between these two variables is 0.36 and is statistically significant at the 5% level (see Table A3 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online).

8. The mean variance inflation factor (VIF) is only about 1.52 in the full specification. For the coefficient estimates for control variables, see Tables A4 and A5 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online.

9. Including the employment share in manufacturing in 1925 leads to the insignificance of historical self-employment and the entrepreneurial personality fit. The mean VIF with the manufacturing control of 1.52 clearly indicates that multicollinearity is no issue here. There is still a significant effect with regional controls when instrumenting the personality fit with the historical science-based self-employment rate.

10. In their approach, historical entrepreneurship is used as an instrument for current new business formation. Regional employment growth was the dependent variable in the second stage.

11. The positive relationship between the historical self-employment rate and entrepreneurship (innovation activity) shown in and is not a violation of the exclusion restriction. The models in and can be regarded as ‘reduced form estimates’, which should be related to the outcome variable if the instrument is valid. The exclusion restriction holds if the instrument affects the outcome exclusively via its effect on the treatment (for details, see Becker, Citation2016). This is exactly what we discussed in our conceptual framework.

12. A plausible interpretation of this pattern is that science-based entrepreneurship is a cleaner measure for the self-perpetuation of entrepreneurship and the according emergence of an entrepreneurship culture. This may also explain the higher coefficient estimates in the second stage of the IV analysis. The general private-sector self-employment rate certainly includes also the necessity self-employed, which is unlikely to induce entrepreneurship-facilitating mechanisms as described in the conceptual part.

13. There is also a higher coefficient estimate for the entrepreneurial personality fit as compared with the OLS models of . Thus, regional differences in personality structure which are explained by historically high levels of self-employment are particularly important for regional innovation activity.

14. Pre-war population density and industrialization are highly correlated with Allied bombing and wartime destruction while, for example, the inflow of expellees after the Second World War is negatively related to population density (e.g., Brakman, Garretsen, & Schramm, Citation2004; Wyrwich, Citation2018). Others shocks such as the introduction of socialism in East Germany was not region specific and perfectly captured by federal state dummies. Thus, the shocks are already controlled for in the main analysis.

REFERENCES

- Acs, Z. J., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32, 15–30. doi: 10.1007/s11187-008-9157-3

- Andersson, M., & Koster, S. (2011). Sources of persistence in regional start-up rates – Evidence from Sweden. Journal of Economic Geography, 11, 179–201. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbp069

- Arenius, P., & Minniti, M. (2005). Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 24, 233–247. doi: 10.1007/s11187-005-1984-x

- Becker, S. O. (2016). Using instrumental variables to establish causality. IZA World of Labor, 250. doi:10.15185/izawol.250.

- Bersch, J., Gottschalk, S., Müller, B., & Niefert, M. (2014). The Mannheim Enterprise Panel (MUP) and firm statistics for Germany (ZEW Discussion Paper No. 14-104). Mannheim: ZEW. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2548385

- Beugelsdijk, S. (2007). Entrepreneurship culture, regional innovativeness and economic growth. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 17, 187–210. doi: 10.1007/s00191-006-0048-y

- Bleidorn, W., Schönbrodt, F., Gebauer, J. E., Rentfrow, P. J., Potter, J., & Gosling, S. D. (2016). To live among like-minded others: Exploring the links between person–city personality fit and self-esteem. Psychological Science, 27(3), 419–427. doi: 10.1177/0956797615627133

- Bosma, N., Hessels, J., Schutjens, V., van Praag, M., & Verheul, I. (2012). Entrepreneurship and role models. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33, 410–424. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2011.03.004

- Brakman, S., Garretsen, H., & Schramm, M. (2004). The strategic bombing of German cities during World War II and its impact on city growth. Journal of Economic Geography, 4, 201–218. doi: 10.1093/jeg/4.2.201

- Caliendo, M., Fossen, F., & Kritikos, A. (2014). Personality characteristics and the decision to become and stay self-employed. Small Business Economics, 42, 787–814. doi: 10.1007/s11187-013-9514-8

- Chinitz, B. (1961). Contrasts in agglomeration: Pittsburgh and New York City. American Economic Review, 51, 279–289.

- Cronbach, L. J., & Gleser, G. C. (1953). Assessing the similarity between profiles. Psychological Bulletin, 50, 456–473. doi: 10.1037/h0057173

- Davidsson, P. (1995). Culture, structure and regional levels of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 7, 41–62. doi: 10.1080/08985629500000003

- Davidsson, P., & Wiklund, J. (1997). Values, beliefs and regional variations in new firm formation rates. Journal of Economic Psychology, 18, 179–199. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4870(97)00004-4

- Elfenbein, D. W., Hamilton, B. H., & Zenger, T. R. (2010). The small firm effect and the entrepreneurial spawning of scientists and engineers. Management Science, 56, 659–681. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1090.1130

- Etzioni, A. (1987). Entrepreneurship, adaptation and legitimation. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 8, 175–199. doi: 10.1016/0167-2681(87)90002-3

- Fornahl, D. (2003). Entrepreneurial activities in a regional context. In D. Fornahl, & T. Brenner (Eds.), Cooperation, networks, and institutions in regional innovation systems (pp. 38–57). Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

- Fotopoulos, G. (2014). On the spatial stickiness of UK new firm formation rates. Journal of Economic Geography, 14, 651–679. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbt011

- Fotopoulos, G., & Storey, D. J. (2017). Persistence and change in interregional differences in entrepreneurship: England and Wales, 1921–2011. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49, 670–702. doi: 10.1177/0308518X16674336

- Freytag, A., & Thurik, R. (2007). Entrepreneurship and its determinants in a cross-country setting. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 17, 117–131. doi: 10.1007/s00191-006-0044-2

- Fritsch, M., Obschonka, M., Wyrwich, M., Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Potter, J. (2018). Regionale Unterschiede der Verteilung von Personen mit unternehmerischem Persönlichkeitsprofil in Deutschland – Ein Überblick [Regional differences of people with an entrepreneurial personality structure in Germany – An overview]. Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 76, 65–81. doi: 10.1007/s13147-018-0519-2

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2014). The long persistence of regional levels of entrepreneurship: Germany 1925 to 2005. Regional Studies, 48, 955–973. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2013.816414

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2017). The effect of entrepreneurship for economic development – An empirical analysis using regional entrepreneurship culture. Journal of Economic Geography, 17, 157–189. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbv049

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2018). Regional knowledge, entrepreneurship culture and innovative start-ups over time and space – An empirical investigation. Small Business Economics, 51, 337–353. doi: 10.1007/s11187-018-0016-6

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2019). Regional Trajectories of entrepreneurship, knowledge, and growth – The role of history and culture. Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-97782-9

- Glaeser, E., Kerr, S. K., & Kerr, W. R. (2015). Entrepreneurship and urban growth: An empirical assessment with historical mines. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97, 498–520. doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00456

- Hayton, J. C., & Cacciotti, G. (2013). Is there an entrepreneurship culture? A review of empirical research. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 25(9–10), 708–731. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2013.862962

- Hofstede, G., & McCrae, R. R. (2004). Personality and culture revisited: Linking traits and dimensions of culture. Cross-Cultural Research, 38(1), 52–88. doi: 10.1177/1069397103259443

- Huggins, R., & Thompson, P. (2017). The behavioural foundations of urban and regional development: Culture, psychology and agency. Journal of Economic Geography. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbx040

- John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 114–158). New York: Guilford.

- Kibler, E., Kautonen, T., & Fink, M. (2014). Regional social legitimacy of entrepreneurship: Implications for entrepreneurial intention and start-up behaviour. Regional Studies, 48, 995–1015. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2013.851373

- Laspita, S., Breugst, N., Heblich, S., & Patzelt, H. (2012). Intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 27, 414–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.11.006

- McCrae, R. R. (2001). Trait psychology and culture: Exploring intercultural comparisons. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 819–846. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.696166

- Minniti, M. (2005). Entrepreneurship and network externalities. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 57, 1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2004.10.002

- Nanda, R., & Sørenson, J. B. (2010). Workplace peers and entrepreneurship. Management Science, 56, 1116–1126. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1100.1179

- Niittykangas, H., & Tervo, H. (2005). Spatial variations in intergenerational transmission of self-employment. Regional Studies, 39, 319–332. doi: 10.1080/00343400500087166

- North, D. C. (1994). Economic performance through time. American Economic Review, 84, 359–368.

- Obschonka, M., Schmitt-Rodermund, E., Silbereisen, R. K., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2013). The regional distribution and correlates of an entrepreneurship-prone personality profile in the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom: A socioecological perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(1), 104–122. doi: 10.1037/a0032275

- Obschonka, M., & Stuetzer, M. (2017). Integrating psychological approaches to entrepreneurship: The entrepreneurial personality system (EPS). Small Business Economics. doi: 10.1007/s11187-016-9821-y

- Obschonka, M., Stuetzer, M., Audretsch, D. B., Rentfrow, P. J., Potter, J., & Gosling, S. D. (2016). Macro-psychological factors predict regional economic resilience during a major economic crisis. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(2), 95–104. doi: 10.1177/1948550615608402

- Obschonka, M., Stuetzer, M., Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., Lamb, M. E., Potter, J., & Audretsch, D. B. (2015). Entrepreneurial regions: Do macro-psychological cultural characteristics of regions help solve the ‘knowledge paradox’ of economics? PLOS ONE, 10(6), e0129332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129332

- Obschonka, M., Stuetzer, M., Rentfrow, P. J., Potter, J., & Gosling, S. D. (2017). Did strategic bombing in the Second World War lead to ‘German Angst’? A large-scale empirical test across 89 German Cities. European Journal of Personality, 31(3), 234–257. doi: 10.1002/per.2104

- Obschonka, M., Wyrwich, M., Fritsch, M., Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Potter, J. (2018). Von unterkühlten Norddeutschen, gemütlichen Süddeutschen und aufgeschlossenen Großstädtern: Regionale Persönlichkeitsunterschiede in Deutschland. Psychologische Rundschau. doi: 10.1026/0033-3042/a000414

- Parker, S. (2009). Why do small firms produce the entrepreneurs? Journal of Socio-Economics, 38, 484–494. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2008.07.013

- Rentfrow, P. J., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2008). A theory of the emergence, persistence, and expression of geographic variation in psychological characteristics. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 339–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00084.x

- Saxenian, A. (1994). Regional advantage. Culture and competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. doi: 10.1177/027046769601600314

- Schindele, Y., & Weyh, A. (2011). The direct employment effects of new businesses in Germany revisited: An empirical investigation for 1976–2004. Small Business Economics, 36, 353–363. doi: 10.1007/s11187-009-9218-2

- Schmitt-Rodermund, E. (2004). Pathways to successful entrepreneurship: Parenting, personality, early entrepreneurial competence, and interests. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(3), 498–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.007

- Sorenson, O. (2017). Regional ecologies of entrepreneurship. Journal of Economic Geography. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbx031

- Sorenson, O., & Audia, P. G. (2000). The social structure of entrepreneurial activity: Geographic concentration of footwear production in the United States, 1940–1989. American Journal of Sociology, 106, 424–462. doi: 10.1086/316962

- Spengler, A. (2008). The establishment history panel. Schmollers Jahrbuch/Journal of Applied Social Science Studies, 128, 501–509.

- Statistik des Deutschen Reichs. (1909). Gewerbestatistik, Vol. 209. Berlin: Puttkammer & Mühlbrecht.

- Statistik des Deutschen Reichs. (1927). Volks-, Berufs- und Betriebszaehlung vom 16 Juni 1925: Die berufliche und soziale Gliederung der Bevoelkerung in den Laendern und Landesteilen, Vol. 403–405. Berlin: Reimar Hobbing.

- Stuetzer, M., Audretsch, D. B., Obschonka, M., Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Potter, J. (2017). Entrepreneurship culture, knowledge spillovers and the growth of regions. Regional Studies. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2017.1294251

- Stuetzer, M., Obschonka, M., Audretsch, D. B., Wyrwich, M., Rentfrow, P. J., Coombes, M., … Satchell, M. (2016). Industry structure, entrepreneurship, and culture: An empirical analysis using historical coalfields. European Economic Review, 86, 52–72. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.08.012

- Talhelm, T., Zhang, X., Oishi, S., Shimin, C., Duan, D., Lan, X., & Kitayama, S. (2014). Large-scale psychological differences within China explained by rice versus wheat agriculture. Science, 344(6184), 603–608. doi: 10.1126/science.1246850

- Westlund, H., Larsson, J. P., & Olsson, A. R. (2014). Start-ups and local entrepreneurial social capital in the Municipalities of Sweden. Regional Studies, 48, 974–994. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2013.865836

- Williamson, O. (2000). The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38, 595–613. doi: 10.1257/jel.38.3.595

- Wyrwich, M. (2018). Migration and regional development: Evidence from large-scale expulsions of Germans after World War II (Jena Economic Research Paper No. 2018-002).

- Wyrwich, M., Stuetzer, M., & Sternberg, R. (2016). Entrepreneurial role models, fear of failure, and institutional approval of entrepreneurship: A tale of two regions. Small Business Economics, 46, 467–492. doi: 10.1007/s11187-015-9695-4

- Wyrwich, M., Stuetzer, M., & Sternberg, R. (2018). Failing role models and the formation of fear of entrepreneurial failure: A study of regional peer effects in German regions. Journal of Economic Geography. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lby023

- Zhao, H., & Seibert, S. E. (2006). The Big-Five personality dimensions and entrepreneurial status: A meta-analytical review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 259–271. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.259