ABSTRACT

This study applies the global financial network (GFN) framework to investigate the process and consequences of global financing for a regional economy in a financial globalization era. Using Linyi, a prefectural-level city in China as a case study, it illustrates how the regional economy has been linked with GFN via overseas listings of the lead regional firms. By incorporating in offshore jurisdictions, listing on overseas stock exchanges in world cities and through interaction with international advanced business services firms, since the early 2000s the lead firms and regional economy of Linyi have established global capital and knowledge pipelines.

INTRODUCTION

The financing activities of firms were considered a ‘black box’ and ‘a largely taken-for-granted aspect of production’ (Pollard, Citation2003, p. 429). However, in the context of financialization and globalization of the world economy, finance has influenced society significantly at different scales, from national, through firms to individuals, as documented in the burgeoning research on financialization (Sokol, Citation2013). This research, however, has paid insufficient attention to the local and regional scale of analysis (French, Leyshon, & Wainwright, Citation2011). With financialization, firms and regional economies have been integrated to various degrees and in various ways into the global capital market (Pike, Citation2006; Wójcik & Camilleri, Citation2015; Zademach, Citation2009). As a result, explaining local and regional financial systems is not sufficient for understanding the financial drivers of local and regional development (Pike, Citation2006). How local and regional economies insert themselves into the global financial system, and vice versa, influences their development trajectories beyond the financial sphere, with implications for growth, innovation, inequality and sustainability (Zademach, Citation2009).

The key challenge to economic geography and regional studies is to unpack the relationships between the benefits and costs of international financial integration under different local conditions and circumstances. While the existing literature highlights the importance of insertion into the global production networks (GPN) and global value chains for the development of firms and regional economies (Coe, Dicken, & Hess, Citation2008; Coe, Hess, Yeung, Dicken, & Henderson, Citation2004; Giuliani, Pietrobelli, & Rabellotti, Citation2005; Humphrey & Schmitz, Citation2002), less attention has been paid to the role of global capital markets in regional development in the era of globalization in economic geography research. The concept of global financial network (GFN) has been developed recently by Coe, Lai, and Wójcik (Citation2014), and has been used to analyze how firms are connecting with and using the global financial markets in a recent study on China Mobile (Wójcik & Camilleri, Citation2015). While this framework has not been adopted to perform the analysis at a regional level, this study tries to fill in the gap, highlighting the importance of integration into GFN for regional development in less developed countries. We argue that firms and regional economies can create the global capital as well as knowledge pipelines via integration into the GFN.

Chinese firms and regional economies have engaged with the GFN particularly through overseas listings. The last 20 years have witnessed a growing number of Chinese firms going public on overseas stock exchanges (Pan & Brooker, Citation2014; Wójcik & Burger, Citation2010). So far, over 1000 firms from mainland China have gone public on overseas stock exchanges, with Hong Kong, New York, Singapore and London as major destinations (Pan & Brooker, Citation2014). Firms listing overseas are not only from the largest metropolitan areas, such as Beijing and Shanghai, but also from less developed regions in the country (Pan & Brooker, Citation2014; Wójcik & Burger, Citation2010). In fact, many Chinese local governments are very supportive of overseas listing of local firms, due to the perceived benefits to local economic development.Footnote1

Drawing on the case of Linyi, a prefectural-level city in China, this study explores the process and consequences of global financing of a regional economy based on the GFN framework. The key components of GFN, including the world cities, offshore jurisdictions and key advanced business service (ABS) firms are analyzed in the case study. By establishing the global capital and knowledge pipelines via integration into GFN from the early 2000s, the regional lead firms in Linyi have raised a large amount of capital, and adjusted their corporate governance and management, with consequences for regional economic development. The empirical analysis demonstrates the potential of the GFN framework to analyze regional development from the perspective of globalization and financialization.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section introduces the GFN framework and elaborates how integration into the GFN might influence regional development. The third section uses the Linyi case to elaborate on the process of integration of a regional economy into the GFN, followed, in the fourth section, by the analysis of impacts of this integration. The last section concludes.

EXPLORING OVERSEAS LISTING AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT FROM THE GFN PERSPECTIVE

GFN as a framework for understanding global finance

Financial globalization describes the integration of a country's financial system into international financial systems (Schmukler, Citation2004), and it has been on the rise since at least the 1980s, albeit arguably at a slower pace since the outbreak of the global financial crisis in 2008 (Clark, Citation2005; French et al., Citation2011). With capital flowing more freely across borders (Clark, Citation2005; Martin, Citation2011), global financial markets have become more integrated. On the one hand, global investors can make investments more freely all over the world. On the other hand, with falling barriers to trade in financial assets, firms can choose to list on foreign exchanges and raise funds abroad (Stulz, Citation2005). Cross-border equity issues in capital markets are an important channel of global financial integration (Kenen, Citation2007). By raising funds through overseas listings, borrowers can reduce the cost of fund raising, expand their investor base and increase liquidity (Schmukler, Citation2004). It was in this context that the concept of GFN was recently coined to capture the geographical structure and analyze major players in global financial markets linking regional economies with world cities and with each other (Coe et al., Citation2014).

GFN is defined as the articulation of ABS firms (with financial firms in the lead) across world cities and offshore jurisdictions (Coe et al., Citation2014). In particular, when local or domestic financial system cannot provide sufficient capital and financial services in both quantity and quality for local firms, integration into the GFN could be an alternative way for a regional economy to raise capital and obtain external services and knowledge. As firms in regions from less developed economies usually suffer more from the shortages in the supply of capital and financial services, linking with the GFN could be an opportunity for both local firms and the regional economy to foster development.

Two specific territories, world cities and offshore jurisdictions, are extremely important in the process of linking regions with the GFN (Coe et al., Citation2014; Wójcik & Camilleri, Citation2015). The world cities are ‘key nodes in an evolving global network’ and ‘vital territories in the spatial articulation and manifestation of intersecting global finance networks’ (Coe et al., Citation2014, p. 764). The world cities are ideal places for regions to raise capital from, as many of them also perform the role of international financial centres, including cities such as New York, London, Hong Kong and Singapore (Pan & Brooker, Citation2014; Wójcik & Burger, Citation2010). These financial centres have mature financial infrastructure and well-developed key financial institutions.

Offshore jurisdictions, such as the Cayman Islands and British Virgin Islands (BVI), are an ‘integral component within a framework that examines global flows and networks of investment and profits’ (Coe et al., Citation2014, p. 764), as they are widely used by corporations, individuals and also states themselves to arrange the financial flows strategically by setting up investment vehicles in these places to deal with tax, legal and regulatory matters (Coe et al., Citation2014). For instance, a large number of Chinese firms, including those overseas listing firms, are incorporated in the Cayman Islands, BVI, Hong Kong and Singapore (Buckley, Sutherland, Voss, & El-Gohari, Citation2015; Pan, He, Sigler, Martinus, & Derudder, Citation2018). Owing to the importance of offshore jurisdictions in accounting for global financial activities, they are integral to the GFN framework.

GFN cannot function without the work of the key actors: ABS firms, which intermediate and facilitate financial activities and help to connect specific firms and regions to world cities and offshore jurisdictions. As pointed out by Coe et al. (Citation2014), finance and professional business services are conceptualized under the broad category of ABS within the GFN framework. In addition to banks, insurance companies and other financial institutions, accountancy, law and business consultancy are also important ABS in mobilizing capital globally. ABS firms are highly concentrated in world cities to enjoy agglomeration economies and other benefits, and play a key role in directing corporate and other clients to offshore jurisdictions.

In fact, financial services firms, which bridge borrowers and investors in financial markets, are a major driving force of financial globalization (Schmukler, Citation2004). In developed economies, competition in financial markets is quite fierce and high-end financial service firms have started to look for opportunities in new markets in emerging economies (Schmukler, Citation2004). Although the location of stock markets is crucial to the geographies of financial services and centres (Wójcik, Citation2009), the global financial services firms can reach the faraway regions where firms with growth potential are in need of capital. Thus, with the help of global financial services firms, the investment could be ‘less spatially bounded’ (Wray, Citation2012). In the case of overseas listings, the stock exchanges themselves are key actors in the GFN. Stock exchange activities are concentrated in leading financial centres (Wójcik, Citation2007), while the competition between stock exchanges compels them to develop promotional activities (Pagano, Röell, & Zechner, Citation2002; Wójcik, Citation2007) to attract more listings from emerging countries, where untapped potential for overseas listings is particularly large.

Integration into GFN via overseas listing and regional development

As a typical way to integrate into the GFN, overseas listings have a significant potential to influence regional development in two ways. On the one hand, insertion in the GFN can help a regional economy overcome capital constraints, as it helps regional firms raise capital and develop a capital pipeline linking the region with world cities and overseas investors. The financial system facilitates the allocation and deployment of economic resources both temporally and spatially (Dixon, Citation2011), and different financial systems have various impacts on firms’ competitiveness, the long-term economic performance and even social structures (Clark & Wójcik, Citation2003, Citation2005; Klagge & Martin, Citation2005). For instance, the local venture capital system has been considered to be critical for the rise of Silicon Valley (Martin, Sunley, & Turner, Citation2002). In contrast, many regional economies in less developed economies suffer from lack of financial resources (Long & Zhang, Citation2011; Ruan & Zhang, Citation2009, Citation2012). Firms in less developed economies have relied largely on local and regional bank loans or other informal financial networks as major sources of financing (Ruan & Zhang, Citation2009, Citation2012). However, the domestic financial resources are often insufficient and the lack of capital is harmful for the formation of flexible and specialized production clusters and networks (Bathelt & Graf, Citation2008; Glassmann, Citation2008) and innovation (Sturgeon, Van Biesebroeck, & Gereffi, Citation2008). Thus, one major challenge for regional development is to make sure firms in the region can obtain sufficient financial resources. Overseas listings provide an important way for firms with growth potential in a regional economy of less developed countries to raise capital (Doidge, Karolyi, & Stulz, Citation2004; Pagano et al., Citation2002). With capital raised through global capital pipelines, lead regional firms can expand their business and invest more in innovation and marketing activities. The regional production networks can also benefit from the expansion of lead firms.

On the other hand, external information and knowledge can be brought through integration into the GFN establishing a global knowledge pipeline in addition to a capital pipeline. It is considered that geographical proximity is critical for accessing knowledge (Gertler, Citation2003). However, by listing on overseas stock exchanges, a typical way of integration into the GFN, firms and regional economy can break into new commercial networks and knowledge pools without geographical proximity. Previous research claimed that firms could benefit from corporate governance, know-how, management and reputation via overseas listing (Doidge et al., Citation2004; Pagano et al., Citation2002). For instance, global investors tend to demand stricter governance standards than their domestic counterparts, which could have a positive impact on performance (Kose, Prasad, Rogoff, & Wei, Citation2006). In addition, global investors may have capacities that allow them to monitor management better than local investors (Kose et al., Citation2006). Furthermore, by listing on an overseas stock exchange, a foreign firm is subject to local laws and regulations and is monitored by the exchange and regulators (Stulz, Citation2005). To meet such requirements, firms are forced to restructure corporate governance and adjust management following the standards defined in the world cities and host countries (Wójcik, Citation2006). In the long term, the regional economy could benefit from such knowledge of modern corporate governance and management obtained from the world cities due to the spillover effects from the listing firms (Kose et al., Citation2006).

A recent case study based on the overseas listing of one single firm, China Mobile, illustrated the potential of GFN in analyzing how global financing activity has occurred and its impacts on firm development. China Mobile was integrated into GFN ‘through registration in Hong Kong, cross-listing in Hong Kong and New York, and creation of offshore entities in the BVI’ (Wójcik & Camilleri, Citation2015, p. 465). Some ABS firms including Goldman Sachs, Linklaters and KPMG played key roles in the initial public offerings (IPOs) of China Mobile (Wójcik & Camilleri, Citation2015). This case also shows integration into GFN has allowed China Mobile to gain capital and expertise to consolidate, expand and modernize its business, and consequently China Mobile has become the largest telecom company in the world (Wójcik & Camilleri, Citation2015).

There is, however, a deficit of empirical evidence applying the GFN framework to the processes and consequences of integration into the global capital markets for regional economies, despite the rapid growing number of firms from emerging economies being listed on stock markets in world cities (Pan & Brooker, Citation2014; Wójcik & Burger, Citation2010). In this study, we will apply the GFN framework to find out how global financing has occurred and impacted regional development based on a case from China.

INTEGRATION INTO THE GFN VIA OVERSEAS LISTINGS: THE LINYI CASE

Research area and methodology

We use Linyi as a case study as it represents a concentration of local and regional firms with overseas listings. Our motivation was also to study an area outside of the most researched agglomerations of Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen. Linyi is a prefectural-level city located in Shandong province () with a population exceeding 10 million. It had a gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of RMB23,886 compared with the average of RMB41,106 in the province in 2010. The city consists of three districts and nine counties with an urbanization rate of 48% in 2010. The unique feature of the city is the dominance of the private sector in its economy. In 2010, for instance, private enterprises generated more than 86% of the city's industrial output value added,Footnote2 which was much higher than the national average. In Linyi, there are 20 firms listing on overseas stock exchanges (), while only three firms are listed on domestic stock exchanges.

Table 1. IPO of firms from Linyi on overseas stock exchanges.

We pay special attention to firms listed on Singapore Stock Exchange (SGX) and firms from the food industry, as these were the first firms from Linyi that conducted an IPO on overseas stock exchanges. Linyi has a dynamic and fast-growing food sector. In 2000, the food processing and food manufacturing industries accounted for 34.7% of all industrial output of the city. Nine of 20 firms that went public on the SGX, Hong Kong Exchange (HKEX) and American Stock Exchange (AMEX) are from the food industry. The SGX, as the first destination, has 10 firms from Linyi and half are from the food sector.

This study is based on both primary and secondary data. On the one hand, we conducted interviews with senior managers of listing firms, local government officials involved in the process and representatives of international stock exchanges. We conducted a field study in Linyi in July 2012, interviewing four senior managers of the two lead food firms listed on the SGX. In addition, we interviewed two local government officials from the Financial Work Office (Jinrong Ban) of Linyi. The local government officials had been involved directly in the overseas listings of regional lead firms. Furthermore, we interviewed managers from the representative offices of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, Deutsche Börse (DB) and the New York Stock Exchange located in Beijing in 2012. In addition, we collected prospectuses and annual reports of all publicly listed firms in Linyi to obtain corporate information, financial details, information on senior managers and ABS firms involved in the IPO. In addition, we collected related news reports from local newspapers and information from the websites of the local government, listing firms and stock exchanges.

Integration process of Linyi's regional economy into GFN

There were 20 IPOs on overseas stock exchanges in Linyi's history. In 2001, two firms were listed on the SGX, People's Food first and United Food later. In the following year, People's Food was cross-listed on the main board of the HKEX. In 2003, the third firm, China Food, was listed on the SGX. In the following years to 2006, seven firms were listed on the SGX (). With time the destinations of overseas-listed firms became more diverse. From 2005 to the present, four firms were listed on the HKEX, two on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX), one on the London Stock Exchange (LSE), one on the DB and one on the AMEX. In contrast, there were only two new domestic listings after 2000: one in 2010 and the other in 2011.

World cities and offshore jurisdictions are two important spatial units connected with regional economies through the operation of ABS firms (Coe et al., Citation2014; Wójcik & Camilleri, Citation2015). As shown in , all overseas listing firms from Linyi are listed on stock exchanges in world cities including Singapore, Hong Kong, London, New York, Frankfort, Kuala Lumpur and Sydney. Singapore and Hong Kong are the two most important destinations, which indicates that there exists a proximity preference in choosing listing destinations (Pan & Brooker, Citation2014).

Offshore jurisdictions are places where most overseas listed firms are incorporated. Taking the nine firms listed on the SGX, for example, four of them are incorporated in Bermuda and five in Singapore (). As the boundary between onshore and offshore financial activities is blurred, Singapore and Hong Kong are often chosen as incorporation places due to their unique combination of ‘offshore advantages and onshore traits’ (Coe et al., Citation2014, p. 765). In addition, incorporating in offshore jurisdictions is also an opportunity for Chinese firms to avoid the constraints that the Chinese government agencies put on overseas listings (Pan & Brooker, Citation2014).

Table 2. Structure of the global financial networks (GFNs) for firms from Linyi listed on the Singapore Stock Exchange (SGX).

As a typical way of integration into the GFN, overseas listings could not have taken place without the operation of ABS firms (Coe et al., Citation2014; Wójcik & Camilleri, Citation2015). As listed in , most ABS firms that were involved in the IPO process at the SGX are global firms from Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia and other countries. China Construction Bank Singapore branch is the only intermediary that has its headquarters in mainland China. With the integration of China in the global economy, international financial firms have focused on China as an important market. The division of labour between the financial and other ABS firms is clear:

Financial service firms were in charge of the whole process. They picked up and helped the potential firms. Business consulting firms design the whole road map; investing banks pushed further; accounting and lawyer firms help to prepare the official documents.Footnote3

The financial intermediaries including stock exchanges, investment banks, consulting companies, and accounting companies and others are also looking for business in China. They were especially interested in those ambitious and far-sighted entrepreneurs. Those people visited Linyi and asked for help from the local government.Footnote5

The representatives of the stock exchanges visited Linyi very frequently. Take Hong Kong for instance, the HKEX has a promotion division in Shanghai and the chief representative visited Linyi every year. They came to Linyi to give lectures, teaching entrepreneurs how to become a public listed firm and promoting the stock exchange they belonged to. I just attended a lecture held by the chief representative of Hong Kong stock exchange.Footnote6

We organize regular events in some cities working with local governments. Local governments invite firms with listing potentials to attend the events. By doing this, more firms and entrepreneurs can get the information about overseas listings on our stock exchange.Footnote7

The subsidiary of our firm located in Hong Kong tried to find external capital. It was found that the financial standards for listing on the SGX were lower than that on the HKEX. So our firm chose the SGX as the destination for overseas listing.Footnote8

IMPACTS OF INTEGRATION INTO THE GFN ON LINYI'S REGIONAL ECONOMY

Insertion in the GFN has significantly reshaped the development trajectories of listed firms as well as the regional economy of Linyi. Considering these development impacts, we will continue to focus on the food industry.Footnote9

Table 3. Advanced financial and business service firms involved in the initial public offering (IPO) of People's Food and United Food.

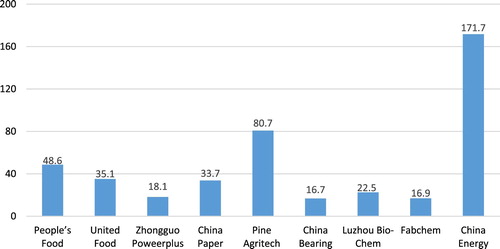

First, a global capital pipeline with Singapore has been established via the listing of the lead firms from Linyi. For example, People's Food raised as much as S$48.6 million by listing shares on the SGX, followed by S$35.1 million raised by United Food (). The two IPOs occurred in 2001 when capital was in short supply and expensive in mainland China. In that period, it was extremely difficult for private firms to borrow from banks and very few private firms had an opportunity to become listed on domestic stock exchanges (Pan & Brooker, Citation2014; Pan & Xia, Citation2014). Therefore, money raised through the IPOs on the SGX was critical for the rapid growth of the two firms. As the manager of one firm complained, ‘The firm was in need of capital very much at that time. It was difficult to borrow from banks. Moreover, domestic listing was not available for our firm.’Footnote10 In addition to the capital raised from the IPOs, both United Food and People's Food conducted further public offerings to raise more capital through the SGX in 2002. In other words, firms and the regional economy in question have created a global capital pipeline after the firms were listed on foreign stock exchanges. Money raised through the global capital pipeline has arguably helped the firms and local economy grow faster than their domestic counterparts.

Figure 2. Capital raised via initial public offerings (IPOs) on the Singapore Stock Exchange (SGX) (Singapore dollars, millions).

Source: Prospectus of the listed firms and media reports.

Using money raised from overseas listings, Linyi's lead food firms invested in expansion. As disclosed in the prospectus, People's Food planned to spend RMB100 million for the acquisition of land-use rights in facilities in three cities within China, RMB43 and 60 million to expand fresh meat production and low-temperature meat products in its new factories. In addition, the firm planned to spend new capital on expanding retail shops in China and investing in research and development. United Food had similar plans. In addition, United Food planned to set up a sales office in Moscow to promote direct sales of their frozen pork products in Russia.

Second, Linyi has also created a global knowledge pipeline with world cities and beyond via integration in the GFN. Two major mechanisms are identified in the field study in Linyi. One has to do with corporate governance standards required by the host stock exchanges. The two listing firms are required to disclose more information and are subject to investigation by the SGX, in addition to investors and analysts from all over the world, which has forced the firms to adjust corporate governance and management accordingly. This could generate spillovers effects for other firms in the regional economy in the long term. As one manager stressed:

Firms need to disclose the business operations and financial information regularly in the annual reports and financial reports. Investors and analysts will examine them very carefully. With the interaction between firms and the global capital market, information is known by domestic entrepreneurs, which is beneficial to the corporate governance, corporate culture and the entrepreneurs. The local entrepreneurs become more qualified.Footnote11

Table 4. Structure of board members of firms listed on the Singapore Stock Exchange (SGX).

They were very strict. Compared to their counterparts in domestic listing firms, they were much more responsible towards investors. With these external people joining the firm, it was easier for us to get new information and improve the governance of the firm. The benefits were obvious.Footnote12

Overall, the regional food industry has grown rapidly since the lead firms’ integration into the GFN. On the one hand, the lead firms have significantly grown their business. According to the financial prospectuses and annual reports, the total sales of People's Food grew from RMB2.3 billion in 1999 to RMB16.8 billion in 2011; the total sales of United Food grew from RMB1 billion in 1999 to RMB5.3 billion in 2011. People's Food, with its Chinese name Jinluo, has become one of the largest pork-processing companies in China since 2007.Footnote14

The fast growth of the lead regional firms, has facilitated the growth of other up- and downstream firms in the same and related sectors. For example, due to the enlargement of production capacity of People's Food, more firms and people are engaged in the activities of feeding pigs. The production network has expanded. The food industry grew significantly from 2000 to 2010. In food processing sector, the number of firms in 2010 was five times of that in 2000, and total sales were about 10 times larger. The food manufacturing industry exhibits a similar growth trend. The food industry has become the pillar of Linyi's economy.Footnote15 Consequently, Linyi has become nationally well known for its pork-processing and manufacturing sector. As mentioned proudly by the local official, ‘Linyi is famous for its pork processing industrial cluster. It is especially competitive in feeding pigs and pork processing. Jinluo (People's Food) has become one of the largest pork processing firm in China since it got listed on SGX.’Footnote16

Furthermore, following the success of the lead regional firms in listing shares on overseas stock exchanges, information about the international capital market, and particularly information on how to access external capital, has spread quickly. As a result, other firms in the food industry and other sectors have started to raise capital from stock markets in international financial centres. Linyi has become the city within Shandong province with the largest number of firms listing on overseas stock exchanges.Footnote17 The Linyi local government has continued to encourage local firms to list on overseas stock exchanges, and considers it an important way to boost local economic development.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Financialization and globalization have together shaped the global economic landscape. As Clark (Citation2005, p. 99) noted, ‘if we are to understand the economic landscape of 21st century capitalism, it should be understood through global financial institutions, its social formations and investment practices’. Global financing has important impacts on regional development (Zademach, Citation2009); however, the conceptualization and theoretical development on this topic is still limited in economic geography.

Drawing on the GFN framework, this study investigated the role of ABS firms and the geographical structure of overseas listings of firms from Linyi. It shows that a few ABS firms from Singapore and Hong Kong played a key role in the process. Singapore and Hong Kong were the major world cities in which the stock exchanges and ABS firms involved are located. Bermuda and Singapore are key offshore jurisdictions (Palan, Citation2010) as incorporation places of the listing firms. The results indicate that the GFN framework can be well applied to explore the process of global financing activities of regional economies.

By integrating into the GFN via overseas listing on the SGX, the regional lead firms and the whole food processing sector in Linyi have created global capital and knowledge pipelines. With capital raised overseas, the lead regional firms in Linyi managed to overcome the local and regional ‘funding gap’. As a consequence, they were able to enlarge their production capacity and invest more in activities such as marketing and research and development (R&D). With the new knowledge pipeline the firms involved and the regional economy have equipped themselves to compete in the national and international market. Corporate governance and reporting requirements from the SGX, and introduction of experienced, international and independent board members have helped the listing firms adjust their corporate governance and management. In addition, they have improved their visibility and reputation significantly since the IPO. With the fast growth of the listing firms, the local production networks of food processing have become more dynamic and the local production chains have been enlarged and extended.

This study indicates that beyond applying the GPN or the global value chain framework, regional economic development can also be understood through the lens of the GFN. With financial globalization, more firms from less developed regions in particular have obtained financial resources in global capital markets. The world cities, offshore jurisdictions and the key ABS firms are crucial to understand the process. Moreover, integration into the GFN is a way in which regional economies can establish global pipelines, which has been considered crucial for regional economic development in the globalization era (Bathelt, Malmberg, & Maskell, Citation2004). This study indicates that overseas listings of lead regional firms could help establish global capital and knowledge pipelines for the regional economy.

Economic geographical studies need to pay more attention to the financial activities of economic actors and regions. In a world of financial globalization, local economic actors and even the local economy as a whole are exposed to the vagaries of the global financial system. It has been long argued that while the developed world has been increasingly integrated by financial flows, lower income countries derived few benefits from the process (Sarre, Citation2007). However, it seems apparent that both government and private actors in less developed economies can also tap into the global financial markets for the benefit of their local and regional economies. This is not to say that there are no major disadvantages and risks of financial globalization (Engelen, Konings, & Fernandez, Citation2010; Lee, Clark, Pollard, & Leyshon, Citation2009; Martin, Citation2011), but to state there are great opportunities for firms and local economies in developing areas.

Admittedly, insertion into GFN can also lead to negative impacts on the local economy. It can lead to disruptive restructuring and dislocation of labour, as well as excessive financialization of the local economy (Muellerleile, Citation2009). It can also lead to conflicts between shareholders, local and remote, and local stakeholders. The shareholders of the firm can surely make decisions at the expense of local development (Pike, Citation2006).

Future studies on the GFN should be strengthened both theoretically and empirically. On the theoretical side, the governance structure of the GFN needs more investigation. In particular, the power relations between ABS firms and their common clients, and among ABS firms (Dorry, Citation2015), are crucial for understanding the formation of the GFN. On the empirical side, more case studies from various regions and countries in different development stages and institutional contexts are needed (Wójcik, Citation2018). Detailed data on overseas listings, for example, is available from stock exchanges and corporate prospectuses, offering opportunities to analyze firms, localities and intermediaries involved in this important subset of the GFN, and ultimately the relationships between the GFN and the GPN.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr Zuoli Liu for help with the interviews in Linyi. The authors are very grateful for the insightful comments made by the editor and anonymous reviewers. All remaining errors are the authors’ own.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Fenghua Pan http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0317-4420

Chun Yang http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0169-3449

He Wang http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3436-1299

Dariusz Wójcik http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2158-284X

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2. Calculated based on the Linyi Statistical Yearbook 2011.

3. Interview with the manager of an overseas listed firm, Linyi, on August 1, 2012.

4. Interview with the manager of an overseas listed firm, Linyi, on August 1, 2012.

5. Interview with a local official, Linyi, July 31, 2012.

6. Interview with a local official, Linyi, July 31, 2012.

7. Interview with a representative officer, Beijing, September 25, 2012.

8. Interview with a manager of an overseas listed firm, Linyi, August 1, 2012.

9. Including the food processing and food manufacturing sectors in Linyi Statistical Yearbook 2001.

10. Interview with a manager of an overseas listed firm, Linyi, August 1, 2012.

11. Interview with a manager of an overseas listed firm, Linyi, August 1, 2012.

12. Interview with a manager of an overseas listed firm, Linyi, August 1, 2012.

13. Interview with a manager of an overseas listed firm, Linyi, August 1, 2012.

16. Interview with a local official, Linyi, July 31, 2012.

REFERENCES

- Bathelt, H., & Graf, A. (2008). Internal and external dynamics of the Munich film and TV industry cluster, and limitations to future growth. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 40(8), 1944–1965. doi: 10.1068/a39391

- Bathelt, H., Malmberg, A., & Maskell, P. (2004). Clusters and knowledge: Local buzz, global pipelines and the process of knowledge creation. Progress in Human Geography, 28(1), 31–56. doi: 10.1191/0309132504ph469oa

- Buckley, P. J., Sutherland, D., Voss, H., & El-Gohari, A. (2015). The economic geography of offshore incorporation in tax havens and offshore financial centres: The case of Chinese MNEs. Journal of Economic Geography, 15(1), 103–128. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbt040

- Clark, G. L. (2005). Money flows like mercury: The geography of global finance. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 87(2), 99–112. doi: 10.1111/j.0435-3684.2005.00185.x

- Clark, G. L., & Wójcik, D. (2003). An economic geography of global finance: Ownership concentration and stock-price volatility in German firms and regions. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93(4), 909–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.2003.09304012.x

- Clark, G. L., & Wójcik, D. (2005). Path dependence and financial markets: The economic geography of the German model, 1997–2003. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 37(10), 1769–1791. doi: 10.1068/a3724

- Coe, N. M., Dicken, P., & Hess, M. (2008). Global production networks: Realizing the potential. Journal of Economic Geography, 8(3), 271–295. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbn002

- Coe, N. M., Hess, M., Yeung, H. W., Dicken, P., & Henderson, J. (2004). ‘Globalizing’ regional development: A global production networks perspective. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 29(4), 468–484. doi: 10.1111/j.0020-2754.2004.00142.x

- Coe, N. M., Lai, K. P., & Wójcik, D. (2014). Integrating finance into global production networks. Regional Studies, 48(5), 761–777. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2014.886772

- Dixon, A. D. (2011). The geography of finance: Form and functions. Geography Compass, 5(11), 851–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00458.x

- Doidge, C., Karolyi, G. A., & Stulz, R. M. (2004). Why are foreign firms listed in the US worth more? Journal of Financial Economics, 71(2), 205–238. doi: 10.1016/S0304-405X(03)00183-1

- Dorry, S. (2015). Strategic nodes in investment fund global production networks: The example of the financial centre Luxembourg. Journal of Economic Geography, 15(4), 797–814. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbu031

- Engelen, E., Konings, M., & Fernandez, R. (2010). Geographies of financialization in disarray: The Dutch case in comparative perspective. Economic Geography, 86(1), 53–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01054.x

- French, S., Leyshon, A., & Wainwright, T. (2011). Financializing space, spacing financialization. Progress in Human Geography, 35(6), 798–819. doi: 10.1177/0309132510396749

- Gertler, M. S. (2003). Tacit knowledge and the economic geography of context, or the undefinable tacitness of being (there). Journal of Economic Geography, 3(1), 75–99. doi: 10.1093/jeg/3.1.75

- Giuliani, E., Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2005). Upgrading in global value chains: Lessons from Latin American clusters. World Development, 33(4), 549–573. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.01.002

- Glassmann, U. (2008). Beyond the German model of capitalism: Unorthodox local business development in the Cologne media industry. European Planning Studies, 16(4), 465–486. doi: 10.1080/09654310801983258

- Humphrey, J., & Schmitz, H. (2002). How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Regional Studies, 36(9), 1017–1027. doi: 10.1080/0034340022000022198

- Kenen, P. B. (2007). Benefits and risks of financial globalization. Cato Journal, 27(2), 179–183.

- Klagge, B., & Martin, R. (2005). Decentralized versus centralized financial systems: Is there a case for local capital markets? Journal of Economic Geography, 5(4), 387–421. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbh071

- Kose, M. A., Prasad, E., Rogoff, K. S., & Wei, S. J. (2006). Financial globalization: A reappraisal. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

- Lee, R., Clark, G., Pollard, J., & Leyshon, A. (2009). The remit of financial geography – Before and after the crisis. Journal of Economic Geography, 9, 723–747. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbp035

- Linyi Statistical Yearbook 2011. (2011). Linyi Statistical Bureau.

- Long, C., & Zhang, X. (2011). Cluster-based industrialization in China: Financing and performance. Journal of International Economics, 84(1), 112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.03.002

- Martin, R. (2011). The local geographies of the financial crisis: From the housing bubble to economic recession and beyond. Journal of Economic Geography, 11(4), 587–618. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbq024

- Martin, R., Sunley, P., & Turner, D. (2002). Taking risks in regions: The geographical anatomy of Europe’s emerging venture capital market. Journal of Economic Geography, 2(2), 121–150. doi: 10.1093/jeg/2.2.121

- Muellerleile, C. M. (2009). Financialization takes off at Boeing. Journal of Economic Geography, 9(5), 663–677. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbp025

- Pagano, M., Röell, A. A., & Zechner, J. (2002). The geography of equity listing: Why do companies list abroad? Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2651–2694. doi: 10.1111/1540-6261.00509

- Palan, R. (2010). International financial centers: The British Empire, city-states and commercially oriented politics. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 11(1), 149–176. doi: 10.2202/1565-3404.1239

- Pan, F., & Brooker, D. (2014). Going global? Examining the geography of Chinese firms’ overseas listings in international stock exchanges. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 52, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.12.003

- Pan, F. H., He, Z. Y., Sigler, T., Martinus, K., & Derudder, B. (2018). How Chinese financial centers integrate into global financial center networks: An empirical study based on overseas expansion of Chinese financial service firms. Chinese Geographical Science, 28(2), 217–230. doi: 10.1007/s11769-017-0913-7

- Pan, F., & Xia, Y. (2014). Location and agglomeration of headquarters of publicly listed firms within China’s urban system. Urban Geography, 35(5), 757–779. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2014.909112

- Pike, A. (2006). ‘Shareholder value’ versus the regions: The closure of the Vaux Brewery in Sunderland. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(2), 201–222. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbi005

- Pollard, J. S. (2003). Small firm finance and economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 3(4), 429–452. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbg015

- Ruan, J., & Zhang, X. (2009). Finance and cluster-based industrial development in China. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 58(1), 143–164. doi: 10.1086/605208

- Ruan, J., & Zhang, X. (2012). Credit constraints, clustering, and profitability among Chinese firms. Strategic Change, 21(3–4), 159–178. doi: 10.1002/jsc.1901

- Sarre, P. (2007). Understanding the geography of international finance. Geography Compass, 1, 1076–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2007.00059.x

- Schmukler, S. L. (2004). Financial globalization: Gain and pain for developing countries. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Economic Review, 89(2), 39–66.

- Sokol, M. (2013). Towards a ‘newer’ economic geography? Injecting finance and financialisation into economic geographies. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 6(3), 501–515. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rst022

- Stulz, R. M. (2005). The limits of financial globalization. Journal of Finance, 60(4), 1595–1638. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00775.x

- Sturgeon, T., Van Biesebroeck, J., & Gereffi, G. (2008). Value chains, networks and clusters: Reframing the global automotive industry. Journal of Economic Geography, 8(3), 297–321. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbn007

- Wójcik, D. (2006). Convergence in corporate governance: Evidence from Europe and the challenge for economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(5), 639–660. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbl003

- Wójcik, D. (2007). Geography and the future of stock exchanges: Between real and virtual space. Growth and Change, 38(2), 200–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2257.2007.000364.x

- Wójcik, D. (2009). Geography of stock markets. Geography Compass, 3(4), 1499–1514. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00255.x

- Wójcik, D. (2018). Rethinking global financial networks: China, politics, and complexity. Dialogues in Human Geography, 8(3), 272–275. doi: 10.1177/2043820618797743

- Wójcik, D., & Burger, C. (2010). Listing BRICs: Stock issuers from Brazil, Russia, India, and China in New York, London, and Luxembourg. Economic Geography, 86(3), 275–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2010.01079.x

- Wójcik, D., & Camilleri, J. (2015). ‘Capitalist tools in socialist hands’? China Mobile in global financial networks. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 40(4), 464–478. doi: 10.1111/tran.12089

- Wray, F. (2012). Rethinking the venture capital industry: Relational geographies and impacts of venture capitalists in two UK regions. Journal of Economic Geography, 12(1), 297–319. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbq054

- Zademach, H.-M. (2009). Global finance and the development of regional clusters: Tracing paths in Munich’s film and TV industry. Journal of Economic Geography, 9(5), 697–722. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbp029