ABSTRACT

The paper studies city-regional spatial planning from an institutional perspective. It applies theories of discursive institutionalism and gradual institutional change to analyse the dialectics of spatial planning and governance between discursively constructed city-regions and the pre-existing regional and local institutional territories. A strained dialectical relationship emerges when city-regional strategic spatial planning is instituted as a supplementary programmatic layer onto the existing strongly regulatory statutory planning, yet leaving intact its deeply institutionalized core-level meaning. Through the case study of the Kotka-Hamina city-region of Finland, the paper explores a situated city-regional attempt to overcome these tensions and generate policy-level change by blending the layered rules and reinterpreting their meaning.

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, the city-region has emerged as a key scale for spatial planning across European countries and the world. It has gained prominence, since political–economic theory and policy praxis have promoted it to be a superior scale for pursuing economic competitiveness and addressing the emerging challenges that cities and regions are facing. Nevertheless, the emergence of city-regions as platforms of planning has only rarely led to formal replacement of rules in the existing statutory system of planning or spatial adjustments vis-à-vis administrative boundaries (e.g., Gualini & Gross, Citation2019; Harrison & Growe, Citation2014; Herrschel & Dierwechter, Citation2018; Salet, Thornley, & Kreukels, Citation2003).

Instead, city-regional policies and governance arrangements tend to layer over existing institutions of regional and local economic governance and spatial planning (Waite & Bristow, Citation2019). City-regions are, therefore, often ‘soft’ planning spaces that exist outside, alongside or in between administrative territories and statutory scales of planning (e.g., Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009). Whereas in territorially bounded ‘traditional’ statutory planning, the central aim has been to produce legally binding plans and regulations for guiding land use within bounded ‘hard’ administrative areas, city-regional planning spaces propose an alternative institutional logic of ‘soft’ strategic spatial planning. This logic yields exploratory, flexible, integrative, action-oriented and agreement-based planning that emphasizes the need for breaching administrative boundaries and accentuating urban entrepreneurialism (Albrechts, Citation2017; Albrechts & Balducci, Citation2013; Dembski & Salet, Citation2010). Indeed, strategic spatial planning for city-regions aims to break away from statutory planning, perceived as slow, bureaucratic and unreflective to the ‘real’ geographies of challenges and opportunities (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009, p. 619). Nevertheless, in practice, strategic spatial planning in administratively fragmented city-regions has been rife with tensions (Jonas & Ward, Citation2007; Salet et al., Citation2003), ranging from technical challenges in defining functional urban systems (Davoudi, Citation2008) to organizational flux (Balducci, Citation2018) and intermunicipal competition over investments and taxpayers (Kantor, Citation2008).

To study the tension-ridden spatial planning of city-regions, we take an institutional approach. It contributes to the growing literature of city-regions that view the city-region as politically constructed (e.g., Harrison, Citation2007; Jonas & Ward, Citation2007) and questions the mainstream academic and political rhetoric of competitive city-regionalism, which assumes a smooth transition to city-regional administrative arrangements (Gualini & Gross, Citation2019; Waite & Bristow, Citation2019, p. 4). Indeed, previous studies have found that instead of a smooth transition, institutional frictions strain city-regional policies. Frictions emerge when discursively constructed city-regional policies and programmes challenge the meaning of pre-existing and deeply embedded norms (e.g., Brenner, Citation2009; Dembski, Citation2015; Dembski & Salet, Citation2010; Fricke & Gualini, Citation2018; Harrison & Growe, Citation2014; O’Brien, Citation2019; Olesen & Richardson, Citation2012; Salet, Citation2018). The contexts of city-regional planning are tension-ridden platforms bringing together local and regional territories and discursively constructed city-regional programmes. In order to enhance the understanding of their dialectical relationship, we propose a framework that draws on recent theoretical work explaining gradual (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010) and discursive institutional change (Schmidt, Citation2008, Citation2011, Citation2016), and apply it to a case of city-regional strategic planning.

The paper examines city-regional strategic planning in the Finnish city-region of Kotka-Hamina. Similar to many other countries, the statutory planning system in Finland bypasses the city-regional scale. However, the Finnish central government has exhorted the municipalities in large- and medium-sized city-regions to cooperate on issues of land use, housing and transport through means of both legal norms and financial support. It has, therefore, instituted cooperative and integrative city-regional planning alongside the formal statutory system of local government-driven and regulatory land-use planning (Bäcklund, Häikiö, Leino, & Kanninen, Citation2018; Hytönen et al., Citation2016). Therefore, the logics of statutory and ‘soft’ planning coexist in Finnish city-regional planning practice. The case of Kotka-Hamina represents an innovative attempt to combine and harmonize these logics in the process of drafting a strategic, yet legally binding, city-regional master plan, jointly coordinated by the five municipalities of the city-region. Being a relatively peripheral and small city-region, Kotka-Hamina may be regarded as an anomaly in the city-region literature, which has typically focused on large and metropolitan city-regions (e.g., Rodriquez-Pose, Citation2008; Scott, Citation2001, Citation2019). While the scope and magnitude of dilemmas often differ between the large and small (peripheral) city-regions (Bell & Jayne, Citation2009; Cardoso & Meijers, Citation2016; Fertner, Groth, Herslund, & Carstensen, Citation2015; Humer, Citation2018), an institutional perspective identifies shared challenges between them, when faced with the contrasting logics of statutory and ‘soft’ planning (e.g., Kantor, Citation2008). Thus, the case provides an example in which joint city-regional planning in an administratively fragmented city-region is conducted within the statutory regulatory planning system. With its innovative use of the statutory master planning instrument, Kotka-Hamina attempted to grasp the benefits and overcome the tensions of city-regional planning. However, it was only partially successful in its effort to challenge and reconstitute the meaning of statutory master planning.

The general implications of our case analysis draw attention to the layered institutional rules of ‘soft’ city-regional and ‘hard’ statutory planning at play in city-regions and their dialectics, when local actors are (re)interpreting the rules in situated policies (cf. Buitelaar, Lagendijk, & Jacobs, Citation2007; Dembski, Citation2015; Neuman, Citation2012; O’Brien, Citation2019; Waite & Bristow, Citation2019). For the study of policy responses to the layered rules, we aim to develop an analytical framework that draws from theories on discursive institutionalism and gradual institutional change. We call our approach dialectical institutionalism (cf. Hay, Citation1999). It discerns the levels of policy, programme and philosophy, which evolve at different intensities and paces, in relation to the emergence of the spatial imaginary of city-region, and sheds a light on how the dynamics of their evolution contribute to the layering of institutional rules. Furthermore, we use the framework to explain how the relationship of layered rules becomes dialectic when situated city-regional policies (re)interpret them in practice. The layered rules create not only tensions for city-regional policies but also favourable conditions for innovation at the policy level, where the rules are validated (cf. Rodriquez-Pose, Citation2008, p. 1036; Salet, Citation2018, p. 2).

The paper is structured as follows. It starts with an introduction to current theories of discursive institutionalism and gradual institutional change, which set the framework for explaining how city-regions are discursively brought into existence and how the emergence of the city-region as a focus of planning and governance has precipitated a change in the institutional set-up of spatial planning. After introducing the institutional context of spatial planning in Finland, the paper turns to explaining the case of city-regional planning practice in Kotka-Hamina as its situated interpretation. It then analyses how layered institutional rules enable and constrain the city-regional master planning process. The paper concludes by outlining its contribution to the institutional approach to planning theory by emphasizing the more general implications drawn from our case analysis.

DISCURSIVE INSTITUTIONALISM AND GRADUAL INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

In planning theory, much attention has been paid to institutions (e.g., Gualini, Citation2001; Salet, Citation2018; Verma, Citation2007) and institutional change (e.g., Alexander, Citation2005; Buitelaar et al., Citation2007; Moroni, Citation2010; Sorensen, Citation2015), following the re-emergent interest in institutions in social and political sciences that was termed ‘New Institutionalism’ (e.g., Hall & Taylor, Citation1996; March & Olsen, Citation1983; Powell & DiMaggio, Citation1991). However, the conceptualizations of institutions are wide ranging among the ‘New Institutionalist’ approaches (Hall & Taylor, Citation1996, pp. 936–7). Based on conceptualizations of the structuring role of institutions and their change, Hall and Taylor (Citation1996) discern three approaches: rational choice, historical and sociological institutionalism. Recently, discursive institutionalism has emerged as a complementary approach to the three New Institutionalist approaches (e.g., Davoudi, Citation2018; Hay, Citation2011; Mehta, Citation2011; Schmidt, Citation2008). Schmidt (Citation2008, p. 304) defines discursive institutionalism as an umbrella concept for approaches that concern themselves with the substantive content of ideas and the interactive processes of discourse and policy argumentation in an institutional context. While in principle discursive institutionalism can provide a complementary view to any of the three New Institutionalist approaches (p. 304), its concept of institution is closest to sociological institutionalism, according to Schmidt (p. 320). Indeed, discursive institutionalism shares the core premises of sociological institutionalism, such as perceiving ideas as internalized in agency, and norms as dynamic, existing only when validated in situated practice (Dembski & Salet, Citation2010; Hall & Taylor, Citation1996, p. 948).

We approach institutions as public norms, which condition interactions between individual or collective subjects, and which, in turn, are validated in this interaction (Dembski & Salet, Citation2010; Salet, Citation2018). Institutions are, thus, not to be confused with organizations. While organizations are systematic arrangements of resources for achieving explicit goals, institutions provide the norms that condition them (Moroni, Citation2010, p. 277; Salet, Citation2018, p. 2). In addition to formal norms, in other words, rules and procedures, institutions can take the form of informal devices that structure action, such as social conventions, mental scripts (e.g., March & Olsen, Citation1983), and background ideas that define them (Schmidt, Citation2008). In our study, we draw on the discursive institutionalist approach that views dynamically constructed ideas, such as the imaginary of the city-region, potentially to reside in the very foundation of institutions (Davoudi, Citation2018; Hay, Citation2011; Neuman, Citation2012; Schmidt, Citation2016). Indeed, the subtle, yet central, aspect that distinguishes discursive institutionalism from sociological institutionalism is its emphasis on dynamically constructed ideas in explaining institutional change (Schmidt, Citation2008, p. 304). In the next subsections, we explain the relationship between dynamic ideas and institutional change as well as the role of agency in this relationship.

The role of ideas in institutional change

The New Institutionalist approaches are often attentive to ideas but frequently focus on how institutions shape ideas, not on how ideas shape institutions (Davoudi, Citation2018, p. 66). To grasp the institution-shaping role of ideas, Schmidt (Citation2008, Citation2011, Citation2016) divides them into distinct analytical categories, namely types, forms and levels. Schmidt delineates different types (cognitive and normative) and forms of ideas, including imaginaries, narratives, stories, frames and myths (cf. Davoudi, Citation2018, p. 67). In this study, we focus particularly on ideas in the form of spatial imaginaries, understood as selective ‘mental maps’ into complex spatial reality (Jessop, Citation2012, p. 17), often involving both visual and textual elements (Davoudi et al., Citation2018).

The ideas, irrespective of their type and form, lie at different levels of generality, including policy, programme and philosophy (Alexander, Citation2005; Mehta, Citation2011, p. 26; Schmidt, Citation2016, p. 319). On this lattermost level, the deepest level of generality, are the axiomatic background ideas that are rarely contested except in times of crisis. They undergird the programmes, as well as policies, with organizing ideas, values and principles of society. On the intermediary level operate the programmatic ideas that define the problems to be solved and the issues to be considered as well as norms, methods and instruments to be applied in the immediate policy ideas. These programmatic ideas, which reflect the background ideas, present the institutional formations (cf. Waite & Bristow, Citation2019). In contrast, the intentional policies or policy solutions for any given problem reside on the surface level (Schmidt, Citation2008, pp. 306–308).

The triggers for institutional change may stem from any of these levels, yet their change occurs at differing paces. While policy ideas may change rather rapidly, in response to changes in the operating environment, programmatic ideas tend to change in either an abrupt revolutionary manner or a gradual evolutionary manner (Schmidt, Citation2016, p. 326). The revolutionary change may occur in critical junctures in a response to external shocks (e.g., Sorensen, Citation2015) or via institutional design (e.g., Alexander, Citation2005; Buitelaar et al., Citation2007), which may lead to substituting not only the policies but also the background ideas (Blyth, Citation2002). In contrast, the evolutionary change occurs endogenously through incremental steps, fuelled by certain gaps in institutions themselves.

Mahoney and Thelen (Citation2010) discern four different types of incremental change (drift, displacement, conversion and layering), depending on the characteristic differences of the institutions in question. With these differences, they refer to the varying veto opportunities of the defenders of the existing institutional rules as well as the varying levels of flexibility for discretion in applying institutional rules. A common starting point for programmatic change is drift, where the changing circumstances motivate practical policy responses that drift apart from existing programmatic rules. As an example of drift, Sorensen (Citation2015, p. 30) mentions city-regional governmental fragmentation due to the strong veto possibilities of existing actors. The counterpart to drift is displacement of an existing institution. With regard to the previous example, change through displacement would mean the establishment of a city-regional government, with statutory planning tasks, and the abolishment of the preceding administrative frames. However, there are also more subtle ways of change, which affect the meaning of the pre-existing institutions. When there is a high degree of discretion in the interpretation or enforcement of institutions, the institutional rules might be strategically enacted in new ways by converting them. In turn, when there is a combination of low discretion and strong veto opportunities, new rules are simply added alongside the pre-existing ones as a new institutional layer (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010). As Waite and Bristow (Citation2019) note, this often happens when city-regional rules are layered on top of existing statutory planning spaces. Layering includes amendments, revisions or additions to existing rules, but it can bring substantial change if amendments alter the logic of the institution or compromise the reproduction of the original deep-seated background idea (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010, p. 17). Yet, competing and conflicting ideas may coexist for even a lengthy period of time (Reay & Hinings, Citation2009), prompting institutional ambiguity (Hajer, Citation2006). In such conditions, the level of intentional policies becomes the site at which the meaning of rules is reflected and possibly changed.

Agency in (re)interpreting institutional rules

In explaining how the ideas at different levels change institutions, discursive institutionalism emphasizes human agency. In order to do so, it defines institutions as dynamic constructs instead of given and continuous structures within which agents act (Schmidt, Citation2008). According to this dynamic view, the institutional norms are justified and reproduced in processes of action. The potential for their change, thus, emerges from agents (re)interpreting the rules in new ways (Salet, Citation2018, p. 3). Indeed, according to Mahoney and Thelen (Citation2010, p. 14), institutional change occurs precisely in the ‘gaps’ between the rule and its local contextualization.

Correspondingly, discursive institutionalism posits agency into institutional change by viewing the relationship between institutions and agents as co-constitutive. While the rules serve as structures constraining action, the agents can reflect and review them through their ideational abilities. Moreover, agents can consciously alter them through their discursive abilities, which enable them to debate and convey ideas (Davoudi, Citation2018; Schmidt, Citation2011, p. 7). Institutions, in turn, affect actors’ conceptions of purposive and interest-promoting action (Hay, Citation2011). Thus, the actors simultaneously embody structure and agency when they think and act beyond institutions to reconstruct them (collectively) even when they operate within their rules (Carstensen & Schmidt, Citation2016; Schmidt, Citation2008, p. 314).

This resembles sociological institutionalism and especially Giddens’ structuration theory (Citation1984), which considers the relationship between structure and agency as co-constitutive, and especially Jessop’s (Citation2001) development of the theory in terms of the strategic-relational approach. In order to transcend the duality of structure and agency, Jessop (Citation2001, pp. 1223–1226) suggests that structures should be treated analytically as strategic in their form, content and operation, thus, privileging some actors, strategies and operations over others. In turn, agency should be treated analytically as structured but strategically calculative, when actors (individual or collective) reflect on the strategic selectivity of structures in choosing a course of action. Hence, they come to orient their strategies in light of their understanding of the game. On this point, Buitelaar et al. (Citation2007, p. 895) have aptly described such a dynamic change process as tireless tinkering of institutions, where institutional arrangements are patched together from mainstream and alternative logics.

Consequently, much emphasis has been placed on the role of agents in constructing new planning spaces. While agents generate and frame new ideas as well as deliberately foster them in intentional policies (Schmidt, Citation2008, p. 309), Salet (Citation2018, pp. 152–153) highlights that ideas as such cannot be institutionalized. In order to institutionalize them, the policies need to reconstitute the meaning of programmatic institutional rules or prevailing normative background ideas (e.g., Dembski, Citation2015; Dembski & Salet, Citation2010; O’Brien, Citation2019). Schmidt (Citation2011) connects the reconstitution with two different types of idea-generating arguments: cognitive and normative. Cognitive arguments generally provide policies or programmes with justification, by framing the problem and presenting the solution, whereas normative arguments provide the programmes with legitimation by speaking to their appropriateness or engaging with deeper core ideas. If the cognitive discourse justifying a particular policy or programme collides with the more deep-seated normative commitments, they either yield or reconstitute it (Schmidt, Citation2011). The delineation between these two types of ideas may explain the success or failure of a certain policy (Davoudi, Citation2018, p. 70).

RESPONSES TO INSTITUTIONAL LAYERING IN THE CITY-REGIONAL PLANNING PRACTICE OF KOTKA-HAMINA

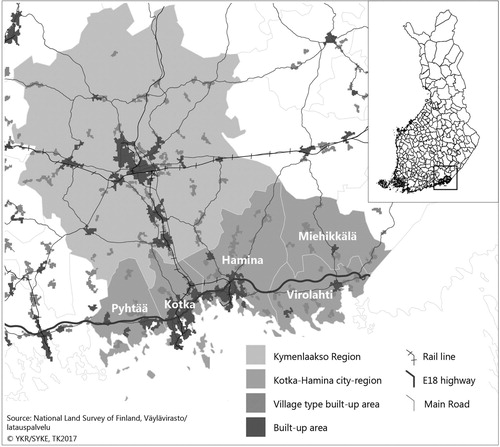

In order to illustrate how the discursively constructed imaginary of the city-region has prompted change in the institutional set-up of spatial planning, which local actors (re)interpret in practice with their situated policies, the paper examines city-regional strategic planning in the Finnish city-region of Kotka-Hamina. The city-region is located in south-east Finland, forming the southern part of the administrative Kymenlaakso region (). It is considered to consist of five municipalities: Kotka, Hamina, Pyhtää, Miehikkälä and Virolahti, which cooperate on a formal basis. By population, the city-region of Kotka-Hamina is middle sized, and the largest of the municipalities, Kotka, accounts for two-thirds of its population of 85,000. These five municipalities have jointly coordinated their local master planning in order to form one city-region-wide master plan, ‘the Kotka-Hamina strategic master plan’, representing an innovative policy-level practice.

This section proceeds with an introduction to the research data and methods applied in the analysis of the policy practice of Kotka-Hamina. Before the analysis, we describe the imaginary of the city-region and the change it has incrementally precipitated in the institutional context of spatial planning in Finland, resulting in the layering of the rules of city-regional planning and local master planning. We then analyse how the layered rules are interpreted in the innovative policy practice of Kotka-Hamina. In our analysis of the city-region, we reveal how the discursively constructed imaginary of the city-region has influenced the emergence of such a practice, in which the actors have strategically used the rules of city-regional planning and statutory local master planning in the same process. The practice exemplifies how agents can innovatively reconstitute the meaning of programmatic rules. However, we finish our case study by revealing how the persistence of the tensions between the underlying normative ideas of city-regional strategic planning, on the one hand, and local government-driven statutory planning, on the other, compromised the innovative policy-level practice.

Data and methods

The empirical data consisted of interviews and policy documents related to the planning process of the Kotka-Hamina strategic master plan, since its initiation in 2007. The process can be divided into three phases, during which the document material was collected:

Drafting of the structural scheme in the course of the temporary Act on Restructuring Local Government and Services (PARAS Act) (2007–12): structural scheme reports (six in total); and meeting minutes of the city-regional council (nine in total) and the city-regional committee (nine in total).

Preparatory phase for the city-regional master plan (2013–15): work programme for the master plan; and meeting minutes of the city-regional council (one in total) and the city-regional committee (three in total).

Jointly coordinated strategic master planning process (2015–19): the draft master plan, the revised plan proposal and the final plan, including attachments (eight in total); official statements on the draft master plan (12 in total) and the master plan proposal (15 in total); and decisions and meeting minutes of the city-regional council (seven in total) and the city-regional committee (seven in total).

The 19 semi-structured interviews were conducted between October 2017 and February 2018. From each of the five municipalities, we approached the mayor, the chair of the municipal council or executive board, and at least one planning official involved in the process. Two of the approached interviewees, however, declined the request. Furthermore, the interviewees included stakeholders actively participating in the process: Kotka-Hamina City-Regional Council, Kymenlaakso Regional Council, Ramboll (a planning consultancy commissioned to draft the plan) and Cursor Ltd (a city-regional development company coordinating the structural scheme and master plan drafting). All interviews were recorded and fully transcribed.

Methodologically, the analysis of the data is based on content analysis. The data were thematically categorized based on interpretations of the Kotka-Hamina city-region as well as related rationalities of city-regional and statutory planning. These two broad categories were further divided into subcategories. The third broad category consisted of tensions that emerged during the planning process. These were connected to the subcategories of interpretations of the city-regional and statutory planning. Finally, we connected the categorized statements to the theoretical framework.

The spatial imaginary of city-region prompting programmatic change in the Finnish planning system

On the deep normative background level, the imaginary of the city-region constitutes a set of theoretical and political core assumptions framing it as the ideal scale, through which economic competitiveness can be pursued within globalized capitalism (Rodriquez-Pose, Citation2008, p. 1029), and through which the emerging challenges facing cities and regions can be addressed (e.g., Albrechts & Balducci, Citation2013). Agglomeration and clustering processes in the global networked economy are regarded as favouring city-regions, where proximities of industry, higher education and services create competitive advantage in terms of complementarities, interdependencies and knowledge exchange. Consequently, the scale and density of production in city-regions is seen to enable them to function as nodes for contesting global markets (Porter, Citation2001; Scott, Citation2001, p. 817; Scott & Storper, Citation2003). While the city-regions are anchored to global networks through the intensifying economic activities of their centres, they spread into the diffuse hinterlands, forming functionally assembled geographical areas, which are often defined based on labour market geographies and commuting flows (Davoudi, Citation2008). This dominating economic–functional imaginary of city-regions (Luukkonen & Sirviö, Citation2019; Waite & Bristow, Citation2019) is fostered with claims that they perform as ‘engines’ of national economic growth and wealth generation (Jonas & Ward, Citation2007; Scott & Storper, Citation2003). From this perspective, the prosperity of the hinterlands is also regarded as dependent on city-regions (Rodriquez-Pose, Citation2008). Such assumptions have motivated a scalar shift in which the centralized welfare state has made room for the devolved entrepreneurial state that seeks new spaces at subnational levels to take forward its competitive agenda (e.g., Brenner, Citation2003, Citation2009; Harrison, Citation2007; Jonas & Ward, Citation2007). From the scalar perspective, city-regions are presented as free from regulatory supervision by the nation-states (Harrison, Citation2007). This leaves city-regions responsible for their own competitiveness, thus prescribing a motivation for voluntary cooperation (Waite & Bristow, Citation2019).

In Finland, such an imaginary of the city-region has paved the way for the territorial transformation of the state. The imaginary was initiated in the 1990s when the rationalities of the competitive and metropolitan state started to challenge the rationalities of the national decentralized welfare state (e.g., Moisio, Citation2012; Moisio & Paasi, Citation2013). The neoliberal ideas of competitiveness and economic attractiveness, which emphasized city-regions as fundamental spatial units in global economic competitiveness, challenged the rationalities of state-orchestrated equalizing of living conditions and balanced regional development. Furthermore, while earlier the cities of various sizes had played a notable role in the hierarchical and centralized planning system of the welfare state, as mediators of national policies and services, the major cities and city-regions became newly rationalized as competition-orientated ‘soft spaces’. As such, they were prioritized as entrepreneurial and autonomous subjects, responsible for their own competitiveness and connectedness to national and global networks (Luukkonen & Sirviö, Citation2019; Moisio, Citation2012).

The discursive construction of city-regions as entrepreneurial subjects and competition-oriented ‘soft spaces’ sparked off initiatives to reduce the number of municipalities through mergers. The aim was to map functional urban regions and gradually develop political governance to match their geographical reaches (Moisio & Paasi, Citation2013, pp. 275–256). For such a purpose, the central government launched the PARAS Act, in force from 2007 to 2012. The Act instructed municipalities in the 17 largest city-regions to produce strategic city-regional plans for integrating land use, housing and transport. While the legal obligations were instigated without provisions on specific tools, city-regional structural schemes became broadly established as the primary tool for their implementation (Hytönen et al., Citation2016). The structural schemes are cross-sectoral and intermunicipal non-statutory documents that express the spatial articulations of city-regional strategic development goals. Since the 2000s, the focus has turned from a nationwide and equally distributed network of city-regions to supporting only the largest city-regions as a source of Finland’s global competitiveness (Moisio, Citation2012). Accordingly, the central government has established two agreement programmes with the local governments of major city-regions, one to support their economic growth (‘Growth Agreements’) and another to foster the intermunicipal implementation of the integrative structural schemes (‘MAL-agreements’ – land-use (M), housing (A) and transport (L)) (e.g., Bäcklund et al., Citation2018). As a result, the spatial planning of city-regions has been institutionalized in the form of ‘soft’ cooperative, voluntary and integrative strategic planning.

However, such city-regional planning has not replaced the statutory planning system that builds on the Nordic tradition of comprehensive planning and the constitutional principle of municipal self-governance as well as the regulatory nature of plans (Nadin & Stead, Citation2008). The system is defined in the Land Use and Building Act (LUBA) (Citation1999), which defines three tiers of land-use plans in a hierarchically binding order: regional land-use plan, local master plan and local detailed plan (local authorities may also draft a joint local master plan). In principle, regional planning is also a form of joint municipal activity because the 18 regional councils drafting them are associations of local governments. Thus, it follows that the local government is the institutional backbone of the system, and all 311 of them are equipped with equal planning powers, irrespective of their size or competences (Hytönen & Ahlqvist, Citation2019).

The LUBA defines the plans in their content, form and preparation process. While the convention is to draw the entire regional or local master plan as legally binding, the Act also enables non-binding or partially binding plans. Furthermore, the plans can be phased or staged to focus only on certain themes at a time. Indeed, although the local master plan should comply with the comprehensive content requirements of the Act (LUBA § 39), their rather general nature leaves room for adapting the master plan to local conditions and needs, in terms of the level of detail and thematic focus. Despite this flexibility of the norms in the Act itself, a convention is to use regional plans and local master plans as legally binding comprehensive and clear-cut zoning plans, based on broad surveys and impact assessments as well as stakeholder participation processes, managed by the corresponding regional or municipal planning department. This follows from the strict policies on interpreting the Act in the administrative courts and the national government’s regional authorities, namely the centres for economic development, transport, and environment. Although the local governments have the authority to ratify their own master plans, appeals on their non-compliance with the Act, on the grounds of, for example, survey requirements not met, may be filed to the regional administrative court (and subsequently to the supreme administrative court) (Mäntysalo, Kangasoja, & Kanninen, Citation2015).

While the plan hierarchy, the comprehensive and binding nature of the plans and the conventionally strict readings of the LUBA by the state authorities provide the system with legal certainty, they leave relatively little room for discretion (Mäntysalo et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, the veto opportunities of the supporters of the current system, namely the local authorities, are strong. The municipalities with the constitutional right for self-governance have economic and political incentives to sustain their local planning autonomy. For example, locally accountable politicians are keen to sustain statutory powers in order to secure re-election, and the local governments in order to guarantee the existing levels of tax revenues and service provision (Hytönen et al., Citation2016). These conditions of low discretion and strong veto opportunities, as Mahoney and Thelen (Citation2010) argue, have led to a gradual change in terms of the layering of institutional rules on the programmatic level.

With the city-regional structural schemes responding to the PARAS Act and the state-local agreements (MAL-agreements) supporting their implementation, the national government has instituted ‘soft’, collaborative and integrative strategic planning at the city-regional level as a layer onto the statutory planning system (Bäcklund et al., Citation2018; Laitio & Maijala, Citation2010). However, implementing these coexisting logics has proven challenging on the level of policy practice. City-regional ‘soft’ planning has especially suffered from the evasive manoeuvring of municipalities, holding on to the deeply rooted background notions of the statutory planning system, namely the municipal planning autonomy (Granqvist, Sarjamo, & Mäntysalo, Citation2019; Hytönen et al., Citation2016). The innovative policy practice of Kotka-Hamina aimed to overcome such manoeuvring by a new interpretation of the coexisting logics, aiming for their blending.

Agents strategically (re)interpreting institutional rules in Kotka-Hamina: innovative institutional practice of city-regional planning

The cooperation between the local governments in the Kotka-Hamina city-region has roots stretching back decades. However, city-regional spatial planning only began in 2007, in order to comply with the requirements of the PARAS Act for intermunicipal cooperation concerning land use, housing and transportation. While the Act exhorted the cooperation between the three municipalities of Kotka, Hamina and Pyhtää, Miehikkälä and Virolahti joined in city-regional spatial planning voluntarily.

Similar to the other city-regions of Finland, Kotka-Hamina initially opted to comply with the requirements of the PARAS Act by drafting an intermunicipal non-statutory document, the city-regional structural scheme. The drafting of the structural scheme served to define core principles guiding city-regional land-use planning and to develop a model for integrated planning of land use, housing, transport, services and economic development. Cultivating such an integrated model involved generating a city-region-wide knowledge base and an organizational structure for intermunicipal planning cooperation: the Working Group on City-Regional Spatial Planning of Kotka-Hamina. The group consisted of the land-use planning officials of the five municipalities, the city-regional economic development agency and the regional council of Kymenlaakso (Cursor, Citation2012a). The city-regional council and city-regional committee, the political powers of which are subordinate to the local governments, were assigned to be the political decision-making bodies for city-regional spatial planning. Although the drafting of the scheme was assessed as a successful initiation of a city-regional spatial planning cooperation (Cursor, Citation2012b, pp. 8–11), in practice the cooperation remained rather inactive. Instead of committing to the city-regional planning cooperation and the non-binding structural scheme, the local governments continued to rely on their local statutory planning authority.

In order to overcome the lack of motivation and commitment to city-regional planning especially among local politicians but also the local planning officials, the local governments decided to use the statutory planning rules as its strategic resource. Consequently, the local governments commenced a process of drafting a city-regional strategic plan, which consists of jointly coordinated statutory and legally binding local master plans (Seutuvaliokunta, Citation2008). With such a process, they aimed for enlarging and reconstituting the meaning of statutory local master planning to cover also city-regional strategic planning. Indeed, the plan sought to combine the ‘soft’ programmatic rules and core ideas of city-regional strategic planning, namely flexibility, responsiveness, selectivity and broad long-term action-orientated visioning, with the rules of statutory planning, such as a legally binding status, planning hierarchy, steering nature and concreteness (Ramboll, Citation2018).

To justify the process, the Working Group on City-Regional Spatial Planning of Kotka-Hamina used not only legitimating normative arguments offered by the statutory system but also cognitive arguments offered by the imaginary of the city-region. These framed the city-region as a prime economic–functional area for pursuing competitiveness, reaping agglomeration benefits for service delivery, and connecting to national and global networks of competition. Indeed, the local officials and politicians single-mindedly adopted the view that all available resources should be pooled together in the city-region for tackling the consequences of abrupt structural economic change, due to the declining forestry industry and the resulting high unemployment and outflow of population. While such a pooling of resources had proven successful in attracting large companies, such as Google, to the city-region, and gaining a central government-funded motorway across the city-region from the capital, Helsinki, to the Russian border, the city-regional master plan was innovatively given a status of an enabling instrument for supporting economic restructuring (Ramboll, Citation2018, p. 78). Such a status challenged the previous approach to master planning as a restrictive instrument.

The central objectives of the city-regional master plan included accommodating flexibly different development paths, increasing attention to the land-use needs of current and prospective businesses, and enabling the implementation of the city-regional (economic) development strategy with its ambitious growth targets of 35,000 new inhabitants and 25,000 new jobs by 2040 (currently 85,000 inhabitants and 30,000 jobs). The implementation of economic development targets meant integrating economic development with land-use planning throughout the process, from objective-setting to emphasizing business locations in the plan content and appointing the city-regional economic development agency as the leader of the planning process.

The economic situation in the region is so poor and the magnitude of the structural change so big that we need to pool all possible resources to tackle it. This was the main reason for commencing the plan, and its particular economic focus. … For us, getting new businesses here is simply a matter of life and death.

(city-regional economic development official A)

The process has broadened the understanding of the local master plan instrument, as well as its relation to city-regional (economic) development strategies. It has especially enhanced the understanding of the use of the statutory master plan as a flexible implementation instrument for strategic objectives.

(planning consultant A)

Because of the new scalar and temporal focus, the plan provided less detailed legal guidance than zoning-type local master plans. Instead, it emphasized the joint recognition of strengths. These strengths were translated spatially in terms of ample and versatile business areas with distinctive profiles, enabling the generation of new agglomerations and synergies of industries. The final plan map expressed these area profiles with informative non-binding land-use guidelines. Novel legally binding land-use guidelines were also provided, limiting business locations only based on their environmental impacts (Ramboll, Citation2018, p. 89). Both types of guidelines provided new tools for marketing the city-region, thus concretely tying the joint vision to implementation. Therefore, the reinterpreted rules of statutory planning served as a resource to strategic planning, when they legitimated the plan and added certainty to its implementation.

The word ‘strategic’ means for us that we scrutinize the issues from the city-regional perspective. In addition to providing a tool to implement our joint objectives, the plan needs to comply with the requirements set on the local master plan in every municipality. … As a planning document it does not introduce many new issues, with the exception of adding the economic development perspective, but with its legally binding role we seek legitimacy for city-regional cooperation.

(local mayor B)

The process started with scenarios. With scenarios, we tested how the city-region would develop if any of our key sectors would grow. In my understanding, this is a novel starting point for a local master plan process. Subsequently, the land uses of the plan reflect the business potentials we found. Currently, we think how to use the plan … as part of marketing and selling investment locations.

(city-regional economic development official A)

Tensions in interpreting layered rules: the persistence of underlying ideas of statutory local and regional planning

The process to draft the city-regional master plan commenced as an ambitious and innovative project between the municipalities to incorporate city-regional strategic planning into statutory local master planning. By a ‘strategically calculative’ interpretation (Jessop, Citation2001), the institutional layers of city-regional and statutory local master planning were brought together into a single process. However, this innovative process was vulnerable since the agents were not only enabled but also bound by two sets of rules and their underlying philosophical background ideas.

While the aim of the planning process was to produce a city-regionally coordinated master plan that is legally binding (LUBA § 42.1), the plan was bound by the content and survey requirements set on statutory local master plans as well as the frames set by the hierarchically superior regional statutory plan. According to the statements to the plan proposal by the regional council and the overseeing regional agency of the state (Regional Centre for Economic Development, Transport, and Environment), the plan proposal failed to comply with many of these. The plan proposal did not meet the content requirements on a legally binding master plan because instead of paying equal attention to all land uses (LUBA § 39), it focused on land uses contributing to city-regional competitiveness, such as business development and transport. Furthermore, in their statements, the two regional actors did not find that the survey requirements (LUBA § 9) were sufficiently met. According to interviewed planning officials (local planning officials B and C), the heavy survey base was regarded as a limitation to the visionary, agile, and strategically selective nature of city-regional planning, and contrary to its logic. Lastly, the logic of city-regional strategic planning resulted in a superficially presented overarching vision that the statements found to be too lacking in detail to serve as a basis for sound guidance of detailed land-use plans (cf. Ramboll, Citation2018, p. 63). Furthermore, the regional authorities were not satisfied with the visual appearance of the plan map, which combined the conventional statutory legally binding land uses with the informative flexible and non-binding land uses. They considered the unconventional informative land use guidelines unfit for a master plan, and yet these visualizations embodied much of the joint city-regional visioning and the novel enabling approach. While with their statements, the regional actors sought to align the plan proposal with the legal requirements on statutory local master plans, the municipalities and their joint city-regional organs found the statements to express an overly rigid interpretation of the ‘old-fashioned’ core idea of statutory planning.

Most local master plans follow a general thumb-rule: the population forecast is translated into the number of housing units, which are then placed on a map as zones. However, our master plan is different. It is an enabling plan. It enables development and growth of different sectors. … Our plan is based on a roadmap, not zoning. … If the Centre for Economic Development, Transport, and Environment sustains a limited view and does not see what can be done with a master plan or why we have done it, the plan has failed. … In the process, we have learned one important lesson. Views on what land-use plans are or what they should be, are very persistent. In my opinion, these views limit the development of urban structure in Finland.

(planning consultant A)

The first adjustment concerned the status of the plan. Because the regional authorities in their statements deemed the selective focus on city-regional competitiveness as unsuitable for a legally binding master plan, its status was reduced to a stage master plan (Ramboll, Citation2018, p. 1). Furthermore, the land uses that were on purpose initially overlooked in the strategically selective plan proposal, such as preservation of green and cultural environments (Ramboll, Citation2018, p. 65), were added to the final plan. They were directly adopted from the superior regional plan but as non-binding land uses, when sufficient impact assessments were lacking.

The second adjustment concerned the position of the city-regional plan in the hierarchy of statutory plans. Contrary to its initial aim, the plan did not replace any of the municipalities’ previously approved zoning-based partial master plans. Instead, it was approached as an additional ‘fourth level’ in the statutory hierarchy, between the local zoning-based master plans and the regional plan (Ramboll, Citation2018, p. 53). Many interviewed local planning officials were of the opinion that strictly defining a position for a plan in the statutory hierarchy sacrificed its strategic flexibility and relative weight towards other planning levels.

The third adjustment considered the visual appearance of the statutory plan map. Clarifying the visual appearance of the plan, which the regional authorities demanded in their statements, resulted in removing all of the initial non-binding informative land uses from the final map. Consequently, the land-use guidelines of the regional plan remained effective without scrutinizing their timeliness or reflecting on their alignment with the jointly defined strategic content of the plan. While the regional authorities demanded the removal of all of the initial non-binding strategic land uses, adding new non-binding land uses corresponding exactly to the content of the regional plan was acceptable, in their opinion.

The map looked crude when only the legally binding land-uses were included. Therefore, we added the green areas. … However, we did not survey and assess them very carefully but instead, drew them based on existing knowledge and some statements. Therefore, the green areas are included but as non-binding and the Regional Plan is effective in these areas.

(local planning official B)

The new perspective that we came up with was that the plan could help tackle structural economic change and generate new growth. In defining the focus, we also thought how to communicate it to decision makers to get them on board. If I am completely honest, more traditional general planning would not have got funding. If we had followed that approach, we would not have got funding for city-regional planning.

(local planning official A)

If I would not have been involved myself in defining the growth goals, I would wonder, from which fiction novel are they taken.

(local mayor A)

If the plan would have been more realistic and more concrete, the political decision makers would have understood it better and it would have provided a basis for concrete political decisions. People do not commit to a plan they do not believe in, or even the planners don’t believe.

(local politician E)

CONCLUSIONS

This paper adopted an institutional perspective for the study of tension-ridden city-regional spatial planning. While in planning theory, much explanatory value has been placed on the institutional approach, the institutional theories that emphasize the role of ideas and discourse, adopting an endogenous and gradual view on institutional change, have remained underused to date, however (Davoudi, Citation2018; Sorensen, Citation2015). We argue that they provide an apt framework for studying city-regional spatial planning, where tensions emerge from discursively constructed city-regional programmes layering onto the pre-existing institutional framework of local and regional government and statutory land-use planning.

Indeed, the discursively constructed spatial imaginary of the economic–functional city-region has come to change spatial planning processes at different levels, including the philosophical, programmatic and policy levels. While, according to Schmidt (Citation2008), the triggers for institutional change may stem from any of these levels, their change occurs at different intensities and paces as we have aimed to show with our Finnish case study. On the programmatic level, the central government has gradually instituted city-regional ‘soft’ planning through means of legal norms and financial support as a complementary layer onto the ‘hard’ statutory planning system that bypasses the city-regional scale. Mahoney and Thelen (Citation2010) define such layering as one of the four possible types of incremental change at the programmatic level. In Finland, it has occurred in a problematic institutional context in which local governments have strong veto powers to sustain the current system which affords them authority over planning of their own territories, and which, in its conventional use, offers little room for discretion. Thereby, an institutional set-up of mutually discordant logics has emerged, providing the policy level of situated city-regional planning with highly challenging conditions.

The case of Kotka-Hamina illustrates that such a set-up allows, in principle, substantial leeway for actors in the city-regions to respond and strategically enact the institutional rules of the two layers. According to the theories of discursive institutionalism (Schmidt, Citation2008) and gradual institutional change (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010) such leeway emerges because the institutional rules are dynamic. While the rules constrain action, the local actors can reflect on them and orient their own strategies, based on their understanding of the rules (cf. Jessop, Citation2001). The local strategic (re)interpretations may, furthermore, reconstruct the rules and induce their change. Indeed, with its innovative policy practice of integrating city-regional strategic planning with statutory local master planning, Kotka-Hamina aimed to use strategically the ‘best of both worlds’. While doing so, the discursive framing of the city-region reconstituted the meaning of statutory local master planning in the innovative policy of Kotka-Hamina, prompting policy responses towards institutional change. However, the deeply embedded normative background ideas of statutory planning that remained resistant to the imaginary of the city-region, hampered such innovative interpretation of institutional rules. Indeed, it is the mismatch of the core ideas of ‘hard’ statutory and ‘soft’ city-regional planning that creates the tension to be dealt with at the policy level of situated city-regional planning.

While previous studies have discerned the emergence of ‘soft’ city-regional planning spaces (e.g., Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009; Olesen, Citation2012), they have often overlooked the role of coexisting ‘hard’ territories in conditioning city-regional spatial planning. To address this gap, the present paper examined institutional layering and the dialectical dynamics of ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ planning behind the complexities faced in framing situated city-regional policies (Harrison & Growe, Citation2014; Waite & Bristow, Citation2019). Indeed, the dialectical dynamics appear when the layered rules and core ideas are validated in policy practices. For this purpose, we have developed an analytical framework that combines the theoretical approaches of discursive institutionalism (e.g., Schmidt, Citation2008, Citation2011, Citation2016) and gradual institutional change (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010).

Indeed, this combination of approaches that we call ‘dialectical institutionalism’ offers, in our view, a new analytical insight for the study of the dialectical relationship between ‘soft’ city-regional and ‘hard’ statutory planning. By delineating the different levels on which ideas generate institutional change, the framework offers an analytical tool to unpack evolutionary institutional change, which commonly leads to increasing complexity. Complexity increases when the new rules of city-regional planning do not replace the pre-existing institutional rules but add a new layer onto them. Furthermore, the framework provides researchers with a tool for understanding how the city-regional policies respond to the layered institutional logics in practice. By applying the framework in a case of city-regional strategic planning, this paper presents an initial effort to understand the responses. Its further application in other city-regional contexts could help to shed a light on the conditions for turning the institutional dialectics into truly productive practice responses.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Besides the two anonymous referees and the editor, John Harrison, the authors thank Janne Oittinen for support in conducting and transcribing some of the interviews.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Albrechts, L. (2017). Some ontological and epistemological challenges. In L. Albrechts, A. Balducci, & J. Hillier (Eds.), Situated practices of strategic planning: An international perspective (pp. 1–13). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Albrechts, L., & Balducci, A. (2013). Practicing strategic planning: In search of critical Features to explain the strategic character of plans. DisP – The Planning Review, 49(3), 16–27. doi: 10.1080/02513625.2013.859001

- Alexander, E. R. (2005). Institutional transformation and planning: From institutionalization theory to institutional design. Planning Theory, 4(3), 209–223. doi: 10.1177/1473095205058494

- Allmendinger, P., & Haughton, G. (2009). Soft spaces, fuzzy boundaries, and metagovernance: The new spatial planning in the Thames gateway. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 41(3), 617–633. doi: 10.1068/a40208

- Balducci, A. (2018). Pragmatisms and institutional actions in planning the metropolitan area of Milan. In W. Salet (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of institutions and planning in action (pp. 303–314). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bäcklund, P., Häikiö, L., Leino, H., & Kanninen, V. (2018). Bypassing publicity for getting things done: Between informal and formal planning practices in Finland. Planning Practice and Research, 33(3), 309–325. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2017.1378978

- Bell, D., & Jayne, M. (2009). Small cities? Towards a research agenda. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(3), 683–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00886.x

- Blyth, M. (2002). Great transformations: Economic ideas and institutional change in the twentieth century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brenner, N. (2003). Metropolitan institutional reform and the rescaling of state space in contemporary Western Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies, 10(4), 297–324. doi: 10.1177/09697764030104002

- Brenner, N. (2009). Open questions on state rescaling. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 2(1), 123–139. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsp002

- Buitelaar, E., Lagendijk, A., & Jacobs, W. (2007). A theory of institutional change: Illustrated by Dutch city–provinces and Dutch land policy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 39(4), 891–908. doi: 10.1068/a38191

- Cardoso, R., & Meijers, E. (2016). Contrasts between first-tier and second-tier cities in Europe: A functional perspective. European Planning Studies, 24(5), 996–1015. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2015.1120708

- Carstensen, M. B., & Schmidt, V. A. (2016). Power through, over and in ideas: Conceptualizing ideational power in discursive institutionalism. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(3), 318–337. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2015.1115534

- Cursor. (2012a). Kaakon suunta. Kotkan-Haminan seudun kehityskuva 2040. Kotka: Cursor, Oy.

- Cursor. (2012b). Tavoitteistaminen kehityskuvaprosessissa. Kaakon suunta-hankkeen osaraportti B. Kotka: Cursor Oy.

- Davoudi, S. (2008). Conceptions of the city-region: A critical review. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Urban Design and Planning, 161(2), 51–60. doi: 10.1680/udap.2008.161.2.51

- Davoudi, S. (2018). Discursive institutionalism and planning ideas. In W. Salet (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of institutions and planning in action (pp. 61–73). New York: Routledge.

- Davoudi, S., Crawford, J., Raynor, R., Reid, B., Sykes, O., & Shaw, D. (2018). Policy and practice spatial imaginaries: Tyrannies or transformations? Town Planning Review, 89(2), 97–124. doi: 10.3828/tpr.2018.7

- Dembski, S. (2015). Structure and imagination of changing cities: Manchester, Liverpool and the spatial in-between. Urban Studies, 52(9), 1647–1664. doi: 10.1177/0042098014539021

- Dembski, S., & Salet, W. (2010). The transformative potential of institutions: How symbolic markers can institute new social meaning in changing cities. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(3), 611–625. doi: 10.1068/a42184

- Fertner, C., Groth, N. B., Herslund, L., & Carstensen, T. A. (2015). Small towns resisting urban decay through residential attractiveness. Findings from Denmark. Geografisk Tidsskrift/Danish Journal of Geography, 115(2), 119–132. doi: 10.1080/00167223.2015.1060863

- Fricke, C., & Gualini, E. (2018). Metropolitan regions as contested spaces: The discursive construction of metropolitan space in comparative perspective. Territory, Politics, Governance, 6(2), 199–221. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2017.1351888

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society. Outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Granqvist, K., Sarjamo, S., & Mäntysalo, R. (2019). Polycentricity as spatial imaginary: The case of Helsinki city plan. European Planning Studies, 27(4), 739–758. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1569596

- Gualini, E. (2001). Planning and the intelligence of institutions: Interactive approaches to territorial policy-making between institutional design and institution-building. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Gualini, E., & Gross, J. S. (2019). Introduction: Actors, policies and processes in the construction of metropolitan space: Conceptual and analytical issues. In J. S. Gross, E. Gualini, & Y. Lin (Eds.), Constructing metropolitan space. Actors, policies and processes of rescaling in world metropolises (pp. 3–29). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hajer, M. A. (2006). The living institutions of the EU: Analysing governance as performance. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 7(1), 41–55. doi: 10.1080/15705850600839546

- Hall, P. A., & Taylor, R. C. M. (1996). Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Political Studies, 44(5), 936–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x

- Harrison, J. (2007). From competitive regions to competitive city-regions: A new orthodoxy, but some old mistakes. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(3), 311–332. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbm005

- Harrison, J., & Growe, A. (2014). From places to flows? Planning for the new ‘regional world’ in Germany. European Urban and Regional Studies, 21(1), 21–41. doi: 10.1177/0969776412441191

- Hay, C. (1999). Crisis and the structural transformation of the state: Interrogating the process of change. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 1(3), 317–344. doi: 10.1111/1467-856X.00018

- Hay, C. (2011). Ideas and the construction of interests. In D. Béland & R. H. Cox (Eds.), Ideas and politics in social science research (pp. 65–83). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Herrschel, T., & Dierwechter, Y. (2018). Smart transitions in city regionalism. Territory, politics and the quest for competitiveness and sustainability. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Humer, A. (2018). Linking polycentricity concepts to periphery: Implications for an integrative Austrian strategic spatial planning practice. European Planning Studies, 26(4), 635–652. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2017.1403570

- Hytönen, J., & Ahlqvist, T. (2019). Emerging vacuums of strategic planning: An exploration of reforms in Finnish spatial planning. European Planning Studies, 27(7), 1350–1368. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1580248

- Hytönen, J., Mäntysalo, R., Peltonen, L., Kanninen, V., Niemi, P., & Simanainen, M. (2016). Defensive routines in land use policy steering in Finnish urban regions. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(1), 40–55. doi: 10.1177/0969776413490424

- Jessop, B. (2001). Institutional re(turns) and the strategic – Relational approach. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 33(7), 1213–1235. doi: 10.1068/a32183

- Jessop, B. (2012). Economic and ecological crises: Green new deals and no-growth economies. Development, 55(1), 17–24. doi: 10.1057/dev.2011.104

- Jonas, A. E. G., & Ward, K. (2007). An introduction to a debate on city-regions: New geographies of governance, democracy and social reproduction. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 31(1), 169–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2007.00711.x

- Kantor, P. (2008). Varieties of city regionalism and the quest for political cooperation: A comparative perspective. Urban Research and Practice, 1(2), 111–129. doi: 10.1080/17535060802169799

- Laitio, M., & Maijala, O. (2010). Alueidenkäytön strateginen ohjaaminen. Suomen Ympäristö 28/10. Helsinki: Ympäristöministeriö.

- Land Use and Building Act (LUBA) 132/1999. (1999). Retrieved from https://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/1999/en19990132.pdf

- Luukkonen, J., & Sirviö, H. (2019). The politics of depoliticization and the constitution of city-regionalism as a dominant spatial-political imaginary in Finland. Political Geography, 73, 17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.05.004

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (Eds.). (2010). Explaining institutional change: Ambiquity, agency, and power. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Mäntysalo, R., Kangasoja, J. K., & Kanninen, V. (2015). The paradox of strategic spatial planning: A theoretical outline with a view on Finland. Planning Theory and Practice, 16(2), 169–183. doi: 10.1080/14649357.2015.1016548

- March, J., & Olsen, J. (1983). The new institutionalism: Organizational factors in political life. American Political Science Review, 78(3), 734–749. doi: 10.2307/1961840

- Mehta, J. (2011). The varied roles of ideas in politics: From ‘whether’ to ‘how’. In D. Béland & R. H. Cox (Eds.), Ideas and politics in social science research (pp. 23–46). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Moisio, S. (2012). Valtio, alue, politiikka: Suomen tilasuhteiden sääntely toisesta maailmansodasta nykypäivään. Helsinki: Vastapaino.

- Moisio, S., & Paasi, A. (2013). From geopolitical to geoeconomic? The changing political rationalities of state space. Geopolitics, 18(2), 267–283. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2012.723287

- Moroni, S. (2010). An evolutionary theory of institutions and a dynamic approach to reform. Planning Theory, 9(4), 275–297. doi: 10.1177/1473095210368778

- Nadin, V., & Stead, D. (2008). European spatial planning systems, social models and learning. DisP – The Planning Review, 44(172), 35–47. doi: 10.1080/02513625.2008.10557001

- Neuman, M. (2012). The Image of institution. A cognitive theory of institutional change. Journal of the American Planning Association, 78(2), 139–156. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2011.619464

- O’Brien, P. (2019). Spatial imaginaries and institutional change in planning: The case of the Mersey belt in north-west England. European Planning Studies, 27(8), 1503–1522. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1588859

- Olesen, K. (2012). Soft spaces as vehicles for neoliberal transformations of strategic spatial planning? Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 30(5), 910–923. doi: 10.1068/c11241

- Olesen, K., & Richardson, T. (2012). Strategic planning in transition: Contested rationalities and spatial logics in twenty-first century Danish planning experiments. European Planning Studies, 20(10), 1689–1706. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.713333

- Porter, M. (2001). Regions and the new economics of competition. In A. J. Scott (Ed.), Global city-regions: trends, theory, policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Powell, W. W., & DiMaggio, P. J. (Eds.). (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ramboll. (2018). Kotkan-Haminan seudun strateginen vaiheyleiskaava. Kaavaelostus. Retrieved from https://www.kotka.fi/instancedata/prime_product_julkaisu/kotka/embeds/kotkawwwstructure/33471_KotkaHamina_STRYK_2018-11-09_selostus_hyvaks.pdf

- Reay, T., & Hinings, C. R. (2009). Managing the rivalry of competing institutional logics. Organization Studies, 30(6), 629–652. doi: 10.1177/0170840609104803

- Rodriquez-Pose, A. (2008). The rise of ‘city-region’ concept and its development policy implications. European Planning Studies, 16(8), 1025–1046. doi: 10.1080/09654310802315567

- Salet, W. (2018). Public norms & aspirations: The turn to institutions in action. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Salet, W., Thornley, A., & Kreukels, A. (Eds.). (2003). Metropolitan governance & spatial planning: Comparative case studies of European city-regions. London: Spon.

- Schmidt, V. (2008). Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 303–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060606.135342

- Schmidt, V. (2011). Discursive institutionalism: Scope, dynamics and philosophical underpinnings. In F. Fischer & H. Gottweis (Eds.), The argumentative turn revised: Public policy as communicative practice (pp. 85–113). Durham: Duke University Press.

- Schmidt, V. (2016). The roots of neo-liberal resilience: Explaining continuity and change in background ideas in Europe’s political economy. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18(2), 318–334. doi: 10.1177/1369148115612792

- Scott, A. J. (2001). Globalization and the rise of city-regions. European Planning Studies, 9(7), 813–826. doi: 10.1080/09654310120079788

- Scott, A. J. (2019). City-regions reconsidered. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 51(3), 554–580. doi: 10.1177/0308518X19831591

- Scott, A., & Storper, M. (2003). Regions, globalization, development. Regional Studies, 37(6–7), 579–593. doi: 10.1080/0034340032000108697a

- Seutuvaliokunta. (2008). Seutuvaliokunnan päätös (September 9).

- Sorensen, A. (2015). Taking path dependence seriously: An historical institutionalist research agenda in planning history. Planning Perspectives, 30(1), 17–38. doi: 10.1080/02665433.2013.874299

- Verma, N. (Ed.). (2007). Institutions and planning. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Waite, D., & Bristow, G. (2019). Spaces of city-regionalism: Conceptualising pluralism in policy-making. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 37(4), 689–706. doi: 10.1177/2399654418791824