ABSTRACT

The paper examines how new airport infrastructure influences regional tourism. Identification is based on the conversion of a military airbase into a regional commercial airport in the German state of Bavaria. The new airport opened in 2007 and promotes travelling to the touristic region of Allgäu in the Bavarian Alps. A synthetic control approach is used to show that the new commercial airport increased tourism in the Allgäu region over the period 2008–16. The positive effect is especially pronounced in the county in which the airport is located. The results suggest that new transportation infrastructure promotes regional economic development.

INTRODUCTION

Transportation infrastructure connects regions and promotes regional (economic) development. Investments in roads, railroads and airports reduce transportation costs for products and people and help to attract new businesses, production plants and jobs. Moreover, infrastructure constitutes the basic determinant of (inter)national tourism flows. Tourists may well travel to rural areas when roads, railways and airports facilitate convenient and low-cost journeys. They demand accommodation and amenities, cultural affairs such as theatres and exhibitions, amusement parks, etc., and their expenditures in these areas often endorse regional economic development.

We examine how new airport infrastructure influences regional tourism. Empirical studies show that building or extending airports and airport services enhanced international tourism flows (Eugenio-Martin, Citation2016; Khadaroo and Seetanah, Citation2007; Khan et al., Citation2017), increased production and employment (Hakfoort et al., Citation2001; Klophaus, Citation2008; Zak and Getzner, Citation2014), endorsed regional economic development (Halpern and Bråthen, Citation2011; Kazda et al., Citation2017; Mukkala & Tervo, Citation2013),Footnote1 and might even generate positive spillover effects to neighbouring regions (Percoco, Citation2010). However, hardly any empirical studies identify the causal effect of airport infrastructure on tourism or economic development. Empirical studies that examine how infrastructure influences economic development have to deal with identification issues. Transportation infrastructure is built to connect economic units, hence disentangling causality between new infrastructure projects and economic development is difficult. New empirical studies use identification strategies such as instrumental variables (IV) or synthetic control to estimate causal effects of infrastructure programmes on population and employment (Duranton & Turner, Citation2012; Gibbons, Lyytikäinen, Overman, & Sanchis-Guarner, Citation2019; Möller & Zierer, Citation2018), or economic development in individual regions (Ahlfeldt & Feddersen, Citation2018; Chandra & Thompson, Citation2000). Castillo, Garone, Maffioli, and Salazar (Citation2017) use a synthetic control approach to estimate the causal effect of an encompassing infrastructure programme (including a new airport) on employment in the tourism sector in Argentina. However, they do not isolate the effect of the airport. Scholars employing IV approaches show that airports or air passenger traffic increased the local population (Blonigen & Cristea, Citation2015), employment in service-related industries (Brueckner, Citation2003; Green, Citation2007) and local employment in services that directly benefit from the air connection (Sheard, Citation2014). Koo, Lim, and Dobruszkes (Citation2017), however, also use an IV and find no effect of direct air services on tourism inflow. Tsui (Citation2017) uses IV and difference-in-differences approaches and shows that low-cost carriers (LCCs) have a positive effect on domestic tourism demand.

We investigate how new airport infrastructure (specialized in LCCs) influences additional guest arrivals in the tourism sector. The identification is based on the conversion of the military airbase of Memmingerberg into the regional commercial airport of Memmingen (Munich-West) in the German state of Bavaria. The military airfield was built by the Nazi regime in 1935–36 and was reused by the German Bundeswehr after the Second World War. In 2003, it was closed because the federal government decided to reorganize and consolidate the German Bundeswehr. We exploit the conversion of the airfield to a commercial airport specialized on LCCs as an exogenous positive infrastructure shock for the touristic sector in counties close to the airport. The commercial airport opened in 2007 and facilitates travelling to the touristic region of Allgäu in the Bavarian Alps. We use a synthetic control approach comparing tourism inflows in counties close to the new commercial airport and their synthetic counterparts when the new commercial airport started operating. Counties from other regions in Bavaria that are not affected by the new airport constitute the donor pool to construct the synthetic counterfactuals. The results show that the new commercial airport increased incoming tourism from abroad in the Allgäu region over the period 2008–16. The positive effect is especially large in the county where the airport is located (Lower Allgäu): Memmingen Airport increased total arrivals of tourists and business travellers at touristic accommodations in Lower Allgäu on average by 54,000 (22%) and arrivals from abroad on average by 23,000 (69%) per year over the period 2008–16. The results suggest that new transportation infrastructure may promote regional economic development.

BACKGROUND: HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, AIRLINES AND PASSENGERS

The Regional Airport of Memmingen (FMM), internationally also known as Munich-West or Allgäu Airport, was opened on the former military airbase in Memmingerberg in Bavaria. The military airbase was built by the Nazis in 1935–36 for strategic military reasons, and was reconstructed and reused by the German Bundeswehr and its NATO partners after the Second World War. In 2003, it was closed because the federal government decided to reorganize and consolidate the German Bundeswehr. Local companies decided to start a commercial civil airport on the former NATO airbase because of the high technical endowment and size of the runway. Local governments and the state government supported the civil airport with investments and subsidies for conversion and construction measures. Memmingen Airport, however, does not receive subsidies for its operating business and has reported a positive operating result (earnings before interest and taxes – EBIT) for several years.Footnote2

FMM started operating commercial air service in mid-2007. The airport already had over 450,000 passengers in 2008 and over 800,000 passengers in 2009, with scheduled flights operated by TUIfly and Air Berlin in the first years. The regional airport is specialized in services by LCCs, such as the Irish airline Ryanair (scheduled flights since 2010) or the Hungarian airline Wizz Air (since 2009).Footnote3 The number of passengers increased to 1.17 million by 2017, a decade after its opening (see Figure A1 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online).

The airport connects several countries in Europe and the Mediterranean region to the Allgäu region. German domestic flights were the most important in the first two years after the launch of air services at FMM, but have been discontinued since 2011. In 2018, connections to and from Spain, Portugal, Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine and the UK had the highest passenger volume at Memmingen Airport (see Table A1 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). A passenger survey conducted in 2018 has shown that 40% of all passengers at Memmingen Airport are incoming passengers, similarly during the winter (46%) and summer season (35%) (Bauer et al., Citation2019).Footnote4

Memmingen Airport is located in the touristic region of Allgäu in the south-west of the German state of Bavaria (see Figure A2 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). The Allgäu is a popular touristic region in Germany. It is famous, for example, for hiking and skiing in the Alps, wellness and health hotels, and Germany’s best-known castle: Neuschwanstein. Allgäu ranks second after the state capital city Munich among the most popular touristic regions regarding arrivals and overnight stays in Bavaria. The 2018 passenger survey has shown that Allgäu (21%) and Munich (33%) account for more than half of all overnight stays by incoming passengers via Memmingen Airport (Bauer et al., Citation2019).Footnote5 Growth rates in guest arrivals and overnight stays in the touristic region of Allgäu have exceeded those of Bavaria in total since 2007.

Connectivity via airport infrastructure depends on air services being offered (Derudder, Devriendt, & Witlox, Citation2005). An airport’s attractiveness for airlines is influenced by its catchment area size (Humphreys and Francis, Citation2002; Lieshout, Citation2012) and airport competition in multiple airport regions (Alberts et al., Citation2009; Derudder et al., Citation2010; Lian & Rennevik, Citation2011; Pels et al., Citation2001; Wiltshire, Citation2018). Memmingen Airport is often advertised abroad as Munich-West and Munich’s LCC airport. Flights to FMM tend to be cheaper than to Munich’s International Airport (MUC). Travel times between Memmingen Airport and Munich’s city centre, however, are about 1.5 h (by car and bus/railway likewise), that is, about 0.5–0.75 h more than from MUC. On the contrary, travel times to several touristic places in the Allgäu are reduced when arriving at Memmingen Airport rather than at any other airport.Footnote6

EMPIRICAL STRATEGY AND DATA

Estimation strategy

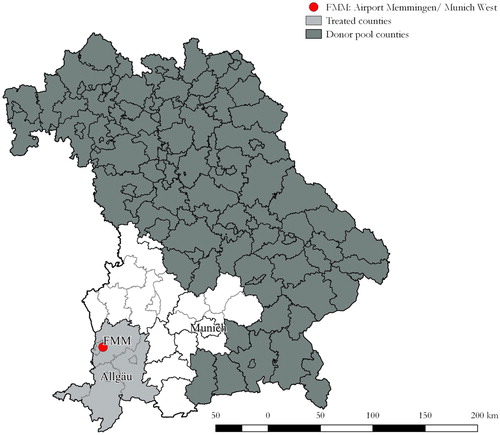

We compare the development of tourism across counties in the German federal state of Bavaria. A total of 96 Bavarian counties form 36 tourism regions (), which merchandise as Bavarian touristic destinations. Therefore, the treatment and control areas (donor pool) are counties belonging to different touristic regions. Memmingen Airport is located in the touristic region of Allgäu, which consists of seven counties constituting the treatment group (light grey counties in ). Counties in touristic regions located in the north and east of Bavaria form the control group (donor pool; dark grey counties in ). Counties from touristic regions bordering the Allgäu, as well as the capital Munich and its vicinity, are excluded from the analysis, that is, they are neither in the treatment nor control groups (white counties in ). Touristic regions bordering Allgäu are likely to be treated to some extent as well. Munich attracts most incoming passengers at Memmingen Airport and is by far the most populous and economically powerful area in Bavaria and, therefore, not comparable with other regions especially in terms of tourism inflows.

Figure 1. Treatment and donor pool regions.

Note: Shown is the federal state of Bavaria with its touristic regions (black boundaries) and the Bavarian counties (grey boundaries). Light grey counties form the treatment region of Allgäu. Dark grey counties form the donor pool. White-shaded counties are not included because they are likely to be treated to some extent as well.

Identification relies on the main assumption that sorting into treatment was exogenous. The placement of the military airbase in 1935–36 and its closure by a decision of the federal government in 2003, hence, the timing of treatment, are obviously independent of touristic considerations. What is more, other former airbases in Bavaria are located relatively close to the international airports in Munich and Nuremberg, or the technical equipment and size of the airfield was not as suitable for a commercial airport. They are reused as special airfields, sport airfields or industrial areas. Memmingen Airport, however, has proximity to the catchment and metropolitan area of Munich. Thus, it was in an ideal location for establishing a specialized LCC airport close to Munich. Its geographical location combined with the circumstances of its conversion renders FMM an ideal testing ground to examine how new transport infrastructure influences tourism indicators in the (peripheral) counties around the airport.

To identify how Memmingen Airport influences tourism in the Allgäu region, we use the synthetic control approach to compare actual developments in tourism with a hypothetical situation, which would probably have arisen without the opening of the commercial airport. The synthetic control method is a powerful approach for comparative case studies when the number of treated units is small, and only aggregated outcomes are observable (Abadie, Diamond, & Gardeazabal, Citation2003; Abadie, Diamond, and Hainmueller Citation2010, Citation2015; Chernozhukov et al., Citation2018). The approach allows one to construct accurate counterfactuals of the counties of interest.Footnote7 The identifying assumption in the present context is that tourism in the treated counties close to the new commercial airport would have evolved in the same manner as in their synthetic counterfactuals in a hypothetical world without the opening of the commercial airport. Synthetic controls for the treated counties are constructed by using lagged values of the outcome variable as predictors (Firpo & Possebom, Citation2018; Kaul et al., Citation2018). The counterfactual outcome is determined as a weighted average of the untreated donor pool counties.Footnote8 Counties from other Bavarian regions that are not affected by the new airport constitute the donor pool in order to construct the synthetic counterfactuals (). The difference in the outcome variable between treated counties and their synthetic counterfactuals following the treatment measures the causal effect of the airport if the following assumptions hold. First, there is a sufficient match between the trends in the outcome variable for synthetic and treated counties over a long pre-treatment period. We provide evidence for this fit in the next section. Second, there are no further interventions that affected treated and untreated counties differently in the treatment period. All counties are part of touristic regions in Bavaria. General policies of the Bavarian state government and actions of the Bavarian Tourism Marketing agency to attract tourists from abroad are supposed to target all Bavarian counties in the post-intervention period. Third, the counties of the donor pool are not affected by the treatment. Counties in touristic regions bordering Allgäu and the capital Munich are not included in the donor pool. A passenger survey conducted at Memmingen Airport in 2018 shows that only up to 7% of all incoming passengers visit one of the 69 donor pool counties in the rest of Bavaria (Bauer et al., Citation2019).Footnote9 By estimating placebo treatment effects in the robustness tests, we show that tourism in donor pool regions is not affected by the opening of the new commercial Memmingen Airport.

We provide parametric estimates from a traditional difference-in-differences model using weighted least squares (WLS) to discuss the significance of the causal inference. When estimating the model with WLS, we weight all counties with the weights derived by the synthetic control approach. In the robustness tests, we also discuss the results when estimating the difference-in-differences model with ordinary least squares (OLS) where all counties receive an equal weight.Footnote10

Data

We use county-level data on registered guest arrivals at touristic accommodations, including business travellers and guests with touristic motives. Guests who do not stay at a touristic accommodation, for example, those staying with friends and relatives, are not registered.Footnote11 The main dependent variable is guest arrivals from abroad because domestic flights were discontinued since 2011. We also use data on total guest arrivals (including domestic and foreign arrivals). The data set encompasses the period 1996–2016.Footnote12 We therefore cover 11 years before the opening of the commercial airport (pre-treatment) and nine years afterwards (post-treatment). The year 2007, when commercial flights started operating, is excluded. We use four treatment regions: East Allgäu, Lower Allgäu, Upper Allgäu and West Allgäu.Footnote13

RESULTS

Baseline

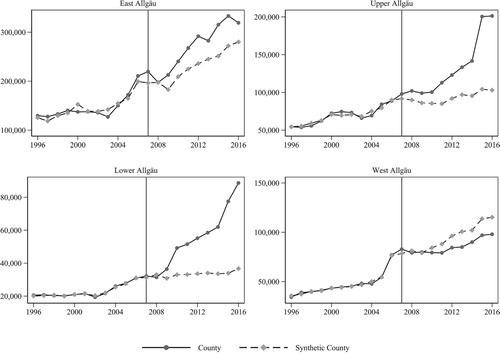

The results of the baseline synthetic control model are shown in and Table A2 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online. We report results for guest arrivals from abroad in the four regions of East, Lower, Upper and West Allgäu. Table A2 online shows that the fitting procedure yields comparable outcomes in treatment and synthetic control units over the pre-treatment period. The ratios of arrivals between the real Allgäu regions and their synthetic counterfactuals amount to almost 100% in all four regions before 2007 (see Table A2 online). shows the pre-treatment matching trends graphically. Table A3 online shows the corresponding individual donor pool weights. The results indicate that the number of total arrivals increased in Lower, Upper and East Allgäu after FMM started operating, compared with their synthetic counterfactuals. The positive effect of Memmingen Airport on arrivals is in relative terms largest in Lower Allgäu, that is, in the counties where Memmingen Airport is based. More precisely, Memmingen Airport increased arrivals from abroad in Lower Allgäu by 69% in the 2008–16 period. The positive effect of the airport on guest arrivals from abroad in Upper and East Allgäu is 45% and 17% (compare the ratios in Table A2, column 2, in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). In West Allgäu, however, the results do not suggest that Memmingen Airport increased the number of arrivals from abroad.

Figure 2. Synthetic control method, arrivals from abroad.

Note: Shown are arrivals from abroad in the four treated regions of East Allgäu, Upper Allgäu, Lower Allgäu and West Allgäu (dark grey), and in their synthetic counterparts (light grey). The donor pool consists of counties in Bavaria that were not treated. The vertical line in each graph marks the opening of Memmingen Airport in 2007.

We compare the synthetic control results with estimates from a difference-in-differences model using WLS where we weight the observations in the regression with the weights derived by the synthetic control approach (for individual weights, see Table A3 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). Hence, we apply the difference-in-differences estimation with the synthetic control group (Roesel, Citation2017). Estimating the effect of the airport on arrivals from abroad using WLS yields similar results to the pre–post-treatment differences of the synthetic control approach (panels A and B of ). When we use the parametric WLS model, the effect of the airport on guest arrivals from abroad is positive and significant in Upper and Lower Allgäu, but does not turn out to be statistically significant in East and West Allgäu (panel B in ). The results suggest that the opening of the commercial airport in Memmingen increased the number of guest arrivals from abroad compared with a counterfactual development without an airport by roughly 42,000 in Upper Allgäu and about 23,000 in Lower Allgäu per year over the 2008–16 period.

Table 1. Difference-in-differences results using weighted least squares (WLS).

We also examine whether the opening of Memmingen Airport influenced total arrivals at touristic accommodations in the Allgäu region (including guests from domestic and abroad). Synthetic control results for total arrivals are very similar to those for arrivals from abroad (see Figure A5 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). Estimates using WLS, however, do not turn out to be statistically significant in East, West and Upper Allgäu. Upper Allgäu county is by far the most popular region for domestic tourists in Bavaria (next to the capital, Munich). Thus, more arrivals from abroad may not translate into more total arrivals in Upper Allgäu. The results suggest that the positive effect of Memmingen Airport on total guest arrivals is only significant in Lower Allgäu, that is, in the counties where FMM is based. The opening of Memmingen Airport increased total guest arrivals in touristic accommodations in Lower Allgäu by year by 54,000 over the 2008–16 period (see Table A4 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). The ratio of real and synthetic total arrivals is 122% for Lower Allgäu over the treatment period 2008–16 (table A2). Lower Allgäu had the lowest number of guest arrivals among all Allgäu regions. Hence, increasing tourism because of the airport is large in relative terms for Lower Allgäu, but, for example, not for Upper Allgäu (see Figure A3 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). Moreover, the counties where Memmingen Airport is based may likewise benefit from incoming and outgoing passengers, for example, if passengers stay in accommodations close to the airport before their departure or after arrival.

Robustness

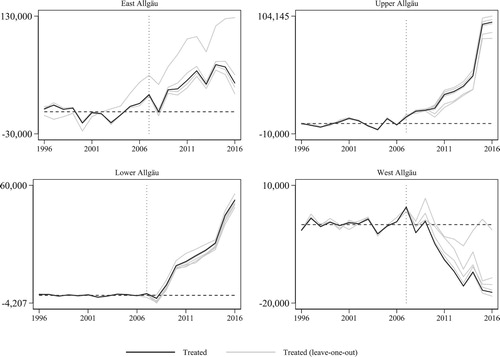

We submit the results to several robustness tests. First, following Abadie et al. (Citation2015), we employ variations in the county weights by constructing leave-one-out distributions of the synthetic control for the Allgäu regions. We re-estimate the baseline model for every treated region and iteratively omit one county from the donor pool that received a positive weight. Results for this robustness test are shown in , which reproduces the baseline results (black line) from with the light grey lines representing the leave-one-out estimates. We focus on the gap in arrivals from abroad between each treated region and its synthetic counterfactual, that is, we calculate the difference between the lines shown in . The estimates excluding individual donor pool counties follow the baseline estimates quite closely in all considered Allgäu regions. The leave-one-out distributions are particularly robust for the Upper Allgäu and Lower Allgäu regions. This finding is in line with the parametric WLS results that only show a significant effect of the airport on guest arrivals from abroad in the Upper and Lower Allgäu regions.

Figure 3. Robustness (I): leave-one-out.

Note: Shown is the gap of arrivals from abroad between the treated regions and their synthetic counterfactuals. The black line represents the gap for the four treated regions of East Allgäu, Upper Allgäu, Lower Allgäu and West Allgäu (baseline synthetic control estimate). The light grey lines represent estimates from repeated synthetic control analyses while iteratively leaving out one donor pool county. The vertical line in each graph marks the opening of Memmingen Airport in 2007.

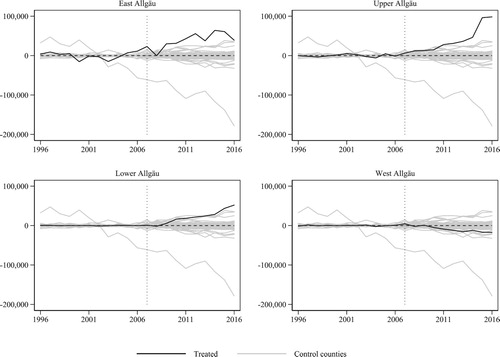

Second, we estimate placebo specifications to verify the validity of the estimation design. We iteratively apply the synthetic control method on every county of the donor pool using them as a placebo-treatment group. If donor pool counties are not affected by the treatment, we should not observe any differences in the development of tourism between the placebo-treatment and control groups, that is, we should estimate zero gaps in guest arrivals for every iteration. The results of this test are shown in , where every light grey line indicates one placebo estimate. This robustness check also corroborates the baseline findings showing that the previously estimated positive treatment effects on arrivals from abroad (black line) in the Allgäu regions are unusually large when compared with the bulk of placebo estimates. What is more, the large majority of placebo estimates reveals a good fit and also produces estimated zero gaps for the control counties. Thus, the selected control counties seem to be a valid comparison group for the treatment regions, since the opening of Memmingen Airport did not influence tourism or coincide with other shocks to touristic inflows in the selected donor pool counties. The positive treatment effect of Memmingen Airport on guest arrivals is indeed considerably larger in East, Lower and Upper Allgäu than in the placebo counties. On the one hand, this validates the choice of control units, but on the other this also increases confidence that the significant baseline estimates for the Upper and Lower Allgäu regions are indeed attributable to the opening of Memmingen Airport.

Figure 4. Robustness (II): placebo test.

Note: Shown is the gap of arrivals from abroad between the treated regions and their synthetic counterfactuals. The black line shows the gap for the four treated regions of East Allgäu, Upper Allgäu, Lower Allgäu and West Allgäu. The light grey lines show 72 placebo gaps for each county in the donor pool. Nuremberg is omitted as an outlier, since it is the upper bound in guest arrivals of the donor pool counties. The vertical line in each graph marks the opening of Memmingen Airport in 2007.

Third, we compare the baseline results with estimates from a traditional difference-in-differences regression using OLS with equal weights of the counties in the control group. Estimating the impact of the airport using difference-in-differences gives rise to positive effects for arrivals from abroad in all the treated regions if we consider all 69 counties of the donor pool (panel A in Table A5 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). Compared with the baseline results, the regions of East and West Allgäu also experienced a significant positive increase of arrivals from abroad. For the regions of East and West Allgäu, the common trend assumption of the difference-in-differences estimation is, however, not fulfilled. Figure A6 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online shows the development of arrivals from abroad in the treatment and control regions between 1996 and 2016. Guest arrivals in the regions of East and West Allgäu experience an increase some years before the airport started operating, compared with the rest of Bavaria. For Upper and Lower Allgäu, in contrast, the common trend assumption fits quite well. Guest arrivals develop similarly compared with the rest of Bavaria before 2007 and start to diverge and increase after Memmingen Airport was opened.Footnote14 In addition, we restrict the counties in the control group to counties that received non-zero weights in the synthetic control approach (but contribute now with an equal weight). The results turn out to be quite similar in economic terms and significance to the baseline estimates using WLS (). When we use the restricted OLS model, the effect of the airport on guest arrivals from abroad is again positive and significant in Upper and Lower Allgäu, but does not turn out to be statistically significant in East and West Allgäu (panel B in Table A5 online).

EFFECTS ON OVERALL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

The results show that new airport infrastructure increases registered arrivals at touristic accommodations. The synthetic control results suggest that every year around 95,000 additional registered guests from abroad arrived in the Allgäu region in the period 2008–16 than would have been the case if the airport had not been opened (see Table A2 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online).Footnote15 The effect is significant and robust for the Upper and Lower Allgäu regions, which amounts to 65,000 additional arrivals from abroad per year. An important question is how the increasing guest arrivals translate into higher revenues in the regional tourist industry. More guests may influence revenues in the tourist industry via numerous channels: they spend on food and accommodation, go shopping and demand, among others, local transport, amenities, spa and skiing, or cultural affairs. At the same time, expenditures in the regional touristic industry induce multiplier effects on other regional industries and often endorse regional economic development. A passenger survey conducted at FMM in 2018 shows that incoming passengers from abroad via Memmingen Airport spent about €131 on average per day, whereas each additional euro in expenditure by an incoming passenger increased purchasing power inflows by a multiplier of around €1.43 in counties located around the airport (Bauer et al., Citation2019).Footnote16

Increasing revenues in the tourism industry because of guest arrivals from abroad are arguably a lower bound of regional economic benefits generated by the opening of the commercial airport. Airport infrastructure is also likely to influence business location and investment decisions, and foster regional economic development by increased production and employment, accounting for the direct effects of production and employment at the airport itself, and indirect effects because of subcontractors benefiting from the new airport infrastructure (Hakfoort, Poot, & Rietveld, Citation2001; Klophaus, Citation2008; Zak & Getzner, Citation2014).Footnote17 In any event, a commercial airport is attractive for tourists and business travellers and might influence business location decisions by helping to enhance a region’s image or facilitate the recruitment of foreign professionals.Footnote18 In 2018, Dorn et al. (Citation2019) conducted a survey asking local entrepreneurs about the extent to which their business benefits from Memmingen Airport and whether their investment decisions have been affected by the airport.Footnote19 The results suggest some positive effects of Memmingen Airport on business connections. A total of 21% of the respondents believe that Memmingen Airport improved business connections, and about one-third reported that the new airport infrastructure helped to improve conditions regarding location and attracting specialist workers from abroad. Breidenbach (Citation2019), however, finds no evidence for spillover effects of regional airports on the surrounding economies in Germany.

Governments and public stakeholders often argue that subsidies and investments in new airport infrastructure pay off because of its regional economic impact. New airport infrastructure has many benefits, but also external costs: ‘the costs are clearly localized in terms of noise, reduced property values, and degradation of health and quality of life’ (Cidell, Citation2015, pp. 1125f.; see also Ahlfeldt & Maennig, Citation2015; Boes & Nüesch, Citation2011). Politicians should consider the total cost–benefit ratio and sustainability of public investment decisions in infrastructure projects.

CONCLUSIONS

Scholars examine the extent to which new transportation infrastructure promotes economic development. Many studies describing the effects of airport infrastructure on economic development employed input–output methods or show correlations. Clearly, the input–output methods and correlations are useful when assessing the benefits of new airport infrastructure, but they do not measure causal effects. Studies examining the causal effect of new airport infrastructure on regional tourism are scarce. We employ a synthetic control approach and estimate how new airport infrastructure increases arrivals of tourists in the Bavarian (peripheral) region of Allgäu. Identification is based on converting a military airbase into the regional commercial airport Memmingen. The results show that additional tourist inflows are particularly pronounced and robust in the county where the airport is located, and are driven by guest arrivals from abroad. The results suggest that new transportation infrastructure promotes regional economic development. The economic effects, however, might also differ among airports in their scale and direction (Allroggen & Malina, Citation2014), and may well depend on the geographical catchment area size and airport competition in multiple airport regions (Lian & Rennevik, Citation2011; Pels, Nijkamp, & Rietveld, Citation2001; Wiltshire, Citation2018). Future research should employ empirical techniques to estimate causal effects of new airport infrastructure in other regions and on other economic outcome variables such as employment and production.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.1 MB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank: the editor, Ben Derudder, and the three anonymous referees; Gabriel Ahlfeldt, Klaus Gründler, Capucine Riom, Felix Roesel and Kaspar Wüthrich; and the participants at the 2019 meeting of the German Economic Association and the 2019 Doctoral conference of the Hanns-Seidel-Foundation in Banz monastery for helpful comments.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Tveter (Citation2017), however, finds small positive effects of regional airports on employment and population in Norwegian municipalities.

2. Many regional airports do not report positive operating results and operate at inefficient levels (Adler, Ülkü, & Yazhemsky, Citation2013). One reason for inefficiency lies in the importance of LCCs (Červinka, Citation2017). Their market power enables LCCs to negotiate favourable agreements, for example, marketing charges (Barbot & D’Alfonso, Citation2014).

3. The emergence of LCCs has led to an overall increase in the number of tourists (Rebollo & Baidal, Citation2009). Tourists choosing LCCs are likely to have different preferences than tourists choosing other carriers (Eugenio-Martin & Inchausti-Sintes, Citation2016).

4. Flight connections to the source regions of Bulgaria, Poland, Romania and Russia had among the highest shares of incoming passengers (> 50%) for all air services in 2018. Air services offered to Sweden and the Mediterranean region, including Croatia, Greece, Italy, Portugal or Spain, are mainly used by outgoing passengers (incoming share < 30%).

5. About 75% among all incoming passengers who stay in the Allgäu region report touristic or private motives; about 20% report business reasons.

6. The only exception is the West Allgäu region close to Lake Constance. For several municipalities in West Allgäu, travel times to Bodensee-Airport Friedrichshafen at Lake Constance are less than to Memmingen Airport. The airport in Friedrichshafen, located in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, was built in 1918 and has been operating as a commercial airport since 1929. Bodensee Airport, however, cannot be described as an LCC airport for Munich such as Memmingen Airport. Passenger numbers at Friedrichshafen Airport have been fluctuating around an annual 550,000 since 2005. Most importantly, passenger numbers of the airport in Friedrichshafen were not altered by the opening of Memmingen Airport (see Figure A1 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). St. Gallen Airport in Switzerland is another small regional airport close to Friedrichshafen, but it has even smaller passenger numbers, which are constantly around 100,000. Innsbruck Airport in Austria and Memmingen Airport might have overlapping catchment areas in the Alps. Innsbruck Airport, however, also increased its passenger numbers since the opening of FMM. We conclude that other airports in the catchment area of Memmingen Airport are no close substitutes (see Figures A1 and A2 online).

7. The synthetic control approach using algorithm-derived weights is supposed to describe better the characteristics of the counties of interest than any single comparison or an equally weighted combination of several control counties. Scholars, however, discuss caveats in the optimal selection of economic predictors for counterfactuals to avoid biased estimates (Kaul, Klössner, Pfeifer, & Schieler, Citation2018).

8. The synthetic control approach is described in technical detail in the supplemental data online.

9. If at all, the airport effect might be biased towards zero if tourists travel to donor pool regions.

10. The method is described in technical detail in the supplemental data online.

11. Using arrivals at touristic accommodations as the dependent variable underestimates the total effect of the airport on tourism, as about half of all incoming passengers reported visiting friends and relatives in a 2018 passenger survey at FMM (Bauer et al., Citation2019).

12. For a raw data plot, see Figure A3 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online.

13. We merge rural counties and independent city counties in the treatment region because the independent city counties are regional centres and geographically enclosed by the rural counties: East Allgäu, including the rural county of Ostallgäu and the city of Kaufbeuren; Lower Allgäu, including the rural county of Unterallgäu and the city of Memmingen; Upper Allgäu, including the rural county of Oberallgäu and the city of Kempten; and West Allgäu, including the rural county of Lindau-Bodensee. For a detailed map, see Figure A4 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online.

14. Similar to Roesel (Citation2017), we find that the results from the difference-in-differences and synthetic control method yield similar results if pre-treatment outcomes follow a common trend. However, if pre-treatment trends are not alike, the synthetic control methods deliver more reliable results.

15. The number 95,000 refers to the sum of the differences between the actual and synthetic arrivals from abroad of the four treatment regions in the period 2008–16.

16. The survey includes 1002 incoming passengers at Memmingen Airport in 2018 (487 during the winter season; 515 during the summer season). Incoming passengers visiting the Allgäu region reported staying around 6.4 days per visit. This would sum up to around €838 direct expenditures and additional €361 indirect multiplier effects in the Allgäu region per incoming passenger from abroad. Considering the total of yearly (significant) 65,000 additional guest arrivals from abroad at accommodations and employing a back-of-the-envelope calculation, Memmingen Airport is supposed to increase direct and indirect tourism revenues by incoming guests from abroad in the Allgäu region by around €77.9 million per year (all in 2018 prices). The calculation must be interpreted with caution, as interviewed incoming passengers at the airport and registered guest arrivals at accommodations are different concepts. On the one hand, one incoming passenger may well count twice in the guest arrivals statistics if they stay in two different accommodations within the same region. On the other hand, average expenditures refer to all surveyed passengers staying at touristic accommodations, or not. While the first could overestimate the economic effect, the latter would underestimate it.

17. One may well want to investigate whether Memmingen Airport had any effect on the overall economic development in the Allgäu region. We cannot use synthetic control techniques to estimate the causal effect of Memmingen Airport on overall economic development measures such as gross domestic product (GDP), because the military airbase that operated until 2003 also had economic impacts on the Allgäu region. The former airbase hosted some 2200 soldiers who stimulated local consumption. They needed to be supplied with necessities including food, etc., which were provided by local enterprises.

18. Scholars examine the extent to which business travellers and tourists have similar preferences regarding airports and airlines. In the San Francisco Bay Area, preferences of business travellers and tourists were quite similar (Pels et al., Citation2001).

19. The survey asked participants in the monthly ifo business survey, whose enterprise is located in 28 counties around Memmingen Airport. The ifo business survey is conducted every month among 7000 German firms; it provides the basis for the ifo Business Climate Index, Germany’s leading business cycle indicator. Among 7000 German firms, 770 are located around Memmingen Airport and have been asked. The response rate was 30.5% (235 firms).

REFERENCES

- Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Gardeazabal, J. (2003). The economic costs of conflict: A case study of the Basque Country. American Economic Review, 93(1), 113–132. doi: 10.1257/000282803321455188

- Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Hainmueller, J. (2010). Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105(490), 493–505. doi: 10.1198/jasa.2009.ap08746

- Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Hainmueller, J. (2015). Comparative politics and the synthetic control method. American Journal of Political Science, 59(2), 495–510. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12116

- Adler, N., Ülkü, T., & Yazhemsky, E. (2013). Small regional airport sustainability: Lessons from bench-marking. Journal of Air Transport Management, 33, 22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2013.06.007

- Ahlfeldt, G. M., & Feddersen, A. (2018). From periphery to core: Measuring agglomeration effects using high-speed rail. Journal of Economic Geography, 18(2), 355–390. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbx005

- Ahlfeldt, G. M., & Maennig, W. (2015). Homevoters vs. leasevoters: A spatial analysis of airport effects. Journal of Urban Economics, 87, 85–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2015.03.002

- Alberts, H. C., Bowen Jr, J. T., & Cidell, J. L. (2009). Missed opportunities: The restructuring of Berlin’s airport system and the city’s position in international airline networks. Regional Studies, 43(5), 739–758. doi: 10.1080/00343400701874248

- Allroggen, F., & Malina, R. (2014). Do the regional growth effects of air transport differ among airports? Journal of Air Transport Management, 37, 1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2013.11.007

- Barbot, C., & D’Alfonso, T. (2014). Why do contracts between airlines and airports fail? Research in Transportation Economics, 45, 34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.retrec.2014.07.005

- Bauer, A., Dorn, F., Doerr, L., Gaebler, S., Krause, M., Mosler, M., … Potrafke, N. (2019). Die regionalökonomischen Auswirkungen des Flughafens Memmingen auf den Tourismus. ifo Forschungsberichte, 100.

- Blonigen, B. A., & Cristea, A. D. (2015). Air service and urban growth: Evidence from a quasi-natural policy experiment. Journal of Urban Economics, 86, 128–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2015.02.001

- Boes, S., & Nüesch, S. (2011). Quasi-experimental evidence on the effect of aircraft noise on apartment rents. Journal of Urban Economics, 69(2), 196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2010.09.007

- Breidenbach, P. (2019). Ready for take-off? The economic effects of regional airport expansions in Germany. Regional Studies, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2019.1659948

- Brueckner, J. K. (2003). Airline traffic and urban economic development. Urban Studies, 40(8), 1455–1469. doi: 10.1080/0042098032000094388

- Castillo, V., Garone, L. F., Maffioli, A., & Salazar, L. (2017). The causal effects of regional industrial policies on employment: A synthetic control approach. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 67, 25–41. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2017.08.003

- Červinka, M. (2017). Small regional airport performance and low cost carrier operations. Transportation Research Procedia, 28, 51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.trpro.2017.12.168

- Chandra, A., & Thompson, E. (2000). Does public infrastructure affect economic activity? Evidence from the rural interstate highway system. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 30(4), 457–490. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0462(00)00040-5

- Chernozhukov, V., Wüthrich, K., Zhu, Y., et al. (2018). An exact and robust conformal inference method for counterfactual and synthetic controls (Working Paper).

- Cidell, J. (2015). The role of major infrastructure in subregional economic development: An empirical study of airports and cities. Journal of Economic Geography, 15(6), 1125–1144. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbu029

- Derudder, B., Devriendt, L., & Witlox, F. (2005). An appraisal of the use of airline data in assessing the world city network: A research note on data. Urban Studies, 42(13), 2371–2388. doi: 10.1080/00420980500379503

- Derudder, B., Devriendt, L., & Witlox, F. (2010). A spatial analysis of multiple airport cities. Journal of Transport Geography, 18(3), 345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.09.007

- Dorn, F., Dörr, L., Fischer, K., Gäbler, S., Krause, M., & Potrafke, N. (2019). Der Flughafen Memmingen als Standortfaktor für die Region: Ergebnisse einer Unternehmensbefragung. ifo Forschungsberichte, 101.

- Duranton, G., & Turner, M. A. (2012). Urban growth and transportation. Review of Economic Studies, 79(4), 1407–1440. doi: 10.1093/restud/rds010

- Eugenio-Martin, J. L. (2016). Estimating the tourism demand impact of public infrastructure investment: The case of Malaga airport expansion. Tourism Economics, 22(2), 254–268. doi: 10.5367/te.2016.0547

- Eugenio-Martin, J. L., & Inchausti-Sintes, F. (2016). Low-cost travel and tourism expenditures. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 140–159. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.019

- Firpo, S., & Possebom, V. (2018). Synthetic control method: Inference, sensitivity analysis and confidence sets. Journal of Causal Inference, 6(2). doi: 10.1515/jci-2016-0026

- Gibbons, S., Lyytikäinen, T., Overman, H. G., & Sanchis-Guarner, R. (2019). New road infrastructure: The effects on firms. Journal of Urban Economics, 110, 35–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2019.01.002

- Green, R. K. (2007). Airports and economic development. Real Estate Economics, 35(1), 91–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6229.2007.00183.x

- Hakfoort, J., Poot, T., & Rietveld, P. (2001). The regional economic impact of an airport: The case of Amsterdam Schiphol Airport. Regional Studies, 35(7), 595–604. doi: 10.1080/00343400120075867

- Halpern, N., & Bråthen, S. (2011). Impact of airports on regional accessibility and social development. Journal of Transport Geography, 19(6), 1145–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2010.11.006

- Humphreys, I., & Francis, G. (2002). Policy issues and planning of UK regional airports. Journal of Transport Geography, 10(4), 249–258. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6923(02)00040-6

- Kaul, A., Klössner, S., Pfeifer, G., & Schieler, M. (2018). Synthetic control methods: Never use all pre-intervention outcomes together with covariates (Working Paper).

- Kazda, A., Hromádka, M., & Mrekaj, B.-R. (2017). Small regional airports operation: Unnecessary burdens or key to regional development. Transportation Research Procedia, 28, 59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.trpro.2017.12.169

- Khadaroo, J., & Seetanah, B. (2007). Transport infrastructure and tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(4), 1021–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2007.05.010

- Khan, S. A. R., Qianli, D., SongBo, W., Zaman, K., & Zhang, Y. (2017). Travel and tourism competitiveness index: The impact of air transportation, railways transportation, travel and transport services on international inbound and outbound tourism. Journal of Air Transport Management, 58, 125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2016.10.006

- Klophaus, R. (2008). The impact of additional passengers on airport employment: The case of German airports. Journal of Airport Management, 2(3), 265–274.

- Koo, T. T., Lim, C., & Dobruszkes, F. (2017). Causality in direct air services and tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research, 67, 67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2017.08.004

- Lian, J. I., & Rennevik, J. (2011). Airport competition – Regional airports losing ground to main airports. Journal of Transport Geography, 19(1), 85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.12.004

- Lieshout, R. (2012). Measuring the size of an airport’s catchment area. Journal of Transport Geography, 25, 27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.07.004

- Möller, J., & Zierer, M. (2018). Autobahns and jobs: A regional study using historical instrumental variables. Journal of Urban Economics, 103, 18–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2017.10.002

- Mukkala, K., & Tervo, H. (2013). Air transportation and regional growth: Which way does the causality run? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 45(6), 1508–1520. doi: 10.1068/a45298

- Pels, E., Nijkamp, P., & Rietveld, P. (2001). Airport and airline choice in a multiple airport region: An empirical analysis for the San Francisco Bay Area. Regional Studies, 35(1), 1–9. doi: 10.1080/00343400120025637

- Percoco, M. (2010). Airport activity and local development: Evidence from Italy. Urban Studies, 47(11), 2427–2443. doi: 10.1177/0042098009357966

- Rebollo, J. F. V., & Baidal, J. A. I. (2009). Spread of low-cost carriers: Tourism and regional policy effects in Spain. Regional Studies, 43(4), 559–570. doi: 10.1080/00343400701874164

- Roesel, F. (2017). Do mergers of large local governments reduce expenditures? – Evidence from Germany using the synthetic control method. European Journal of Political Economy, 50, 22–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2017.10.002

- Sheard, N. (2014). Airports and urban sectoral employment. Journal of Urban Economics, 80, 133–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2014.01.002

- Tsui, K. W. H. (2017). Does a low-cost carrier lead the domestic tourism demand and growth of New Zealand? Tourism Management, 60, 390–403. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.013

- Tveter, E. (2017). The effect of airports on regional development: Evidence from the construction of regional airports in Norway. Research in Transportation Economics, 63, 50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.retrec.2017.07.001

- Wiltshire, J. (2018). Airport competition: Reality or myth? Journal of Air Transport Management, 67, 241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2017.03.006

- Zak, D., & Getzner, M. (2014). Economic effects of airports in Central Europe: A critical review of empirical studies and their methodological assumptions. Advances in Economics and Business, 2(2), 100–111.