ABSTRACT

The locational pattern of clubs in four professional football leagues in Europe is used to test the causal effect of relegations on short-run regional development. The study relies on the relegation mode of the classical round-robin tournament in the European model of sport to develop a regression-discontinuity design. The results indicate small and significant negative short-term effects on regional employment and output in the sports-related economic sector. In addition, small negative effects on overall regional employment growth are found. Total regional gross value added remains unaffected.

INTRODUCTION

Every year in May, a spectre haunts Europe: relegation in professional football. In these times, football clubs close to the relegation ranks across the continent face uncertainty about their league membership in the subsequent season. This situation is noteworthy because many of these clubs performed almost identically in terms of points gained and goals scored in competition over several months. Before the final match day of the 1998/99 German Bundesliga season, for example, five teams were on the verge of relegation: 1. FC Nürnberg, VfB Stuttgart, SC Freiburg, Hansa Rostock and Eintracht Frankfurt.

While the drama of the relegation decision provides utility to fans from an economic perspective, the relegation itself has clearly negative economic consequences for all actors involved. Relegation leads to a reduction in the quality of the game offered to fans (Szymanski & Valletti, Citation2005). Since consumers of sports events are characterized by preferences for extraordinary talent (MacDonald, Citation1988; Rosen, Citation1981), relegations bring about economic shocks that affect everything from labour market consequences for individual players to a drop in income at the club level, to reduced economic opportunities for regional actors in football-related sectors. The regional dimension is a factor mainly because fan interest has a distinctive spatial dimension (Borland & MacDonald, Citation2003).

This paper tests the last part of the assumption. It focuses on the estimation of the regional effects of relegation on professional football clubs across Europe. The set of regions under analysis comprises those with clubs in the English Premier League (EPL), German Bundesliga, Italian Serie A and French Ligue 1 in the period 1995–2010. It demonstrates that relegation contributes to an adjustment in demand for live attendance. This result is in line with earlier findings for the UK (e.g., Simmons, Citation1996). In addition, it is shown that relegation also affects regional economic outcomes. To estimate the size of these effects, the study makes use of the particular characteristics of the system of relegation and promotion in Europe. The presence of a smooth forcing variable (the points a club has achieved during the season), an arbitrarily defined cut-off (the ranks dedicated to relegation in the league) and the imprecise control clubs have on the cut-off value (the points necessary to reach a non-relegation rank in the final league table) allows a regression-discontinuity design (RDD) to be developed.

The empirical analysis compares the post-relegation performance of regions with clubs close to the relegation ranks. This approach extends the existing empirical literature on the regional impact of large sporting events by adopting a new perspective. The identification strategy abstracts from the use of the presence, arrival or departure of professional sports franchises as a source of identification (Baade & Sanderson, Citation1997; Coates & Humphreys, Citation1999, Citation2003). Instead, the focus is on regular changes in top-division membership. It is argued that tight relegation decisions produce situations in which the economic situation of the region is independent of treatment and therefore avoids potential endogeneity problems that occur because relegations might be the result of the economic weakness of the region or regional sponsors. This reduces potential bias and allows a consistent estimate of the net effect of relegation on regional development.

The results reveal that relegations indeed result in significant, negative short-term effects on regional employment and gross value added (GVA) growth in football-related economic sectors. In contrast to existing studies on large sporting events, a small negative effect on total regional employment growth is also found. Total regional GVA growth, however, remains unaffected by relegation, implying that substitution takes place and sectors outside the football-related economy benefit in terms of higher productivities from the relegation of a top-division football club.

The paper is structured as follows. The second section discusses the research on regional effects of large sporting events and describes the particularities of the system of relegation and promotion in European sports’ leagues. The third section highlights the identification strategy and the data used to perform the analysis. The fourth section presents and discusses the results. The fifth section concludes.

THE ECONOMIC SIGNIFICANCE OF PROFESSIONAL SPORTS EVENTS

European professional football has become a big business in the last decades. Only recently, the EPL sold its television rights for the three seasons from 2016 onwards for a record £5.136 billion. Television rights for four seasons in the Bundesliga, starting in 2017, totalled €4.64 billion. Live attendance figures reveal the interest in football across the continent. Approximately 14 million people attended regular league games in the EPL during the season 2015/16. The Bundesliga attracted 12 million visitors over the same period (Deutsche Fussball Liga (DFL), Citation2017). Given these (and other) sources of income, today’s top-division football clubs in Europe can be described as medium to large enterprises with increasing relevance for regional development. If these firms are hit by idiosyncratic firm-level shocks, such as relegation, this might provide a case where microlevel shocks translate into aggregate regional outcomes.Footnote1

The presence of regional effects of professional sports clubs or events, however, has been the subject of intense scientific debate (Coates, Citation2015). In this context, ex-ante studies on the economic impact of major sports events tend to present overly optimistic claims for regional or even national outcomes (see Baade & Matheson, Citation2016; and Maennig, Citation2017, for some illustrative examples). In contrast, scientific papers already have argued for more cautious expectations about the regional relevance of professional sport (Baade & Dye, Citation1990). For example, Baade and Sanderson (Citation1997) found no increase in the economic activity in US cities that had seen new stadiums built or acquired additional professional sports teams between 1958 and 1993. The same applies to Värja (Citation2016), who finds no evidence of a positive effect of professional football and ice hockey teams on the local tax base in Sweden. Storm et al. (Citation2019) contribute to this discussion by showing that there is no effect of Formula 1 races on the regional economy in Europe. Coates and Humphreys (Citation1999) even found consistently negative effects of the presence of professional sports franchises belonging to the US National Football League (NFL) (i.e., American football), Major League Baseball (MLB) or National Basketball Association (NBA) on individual incomes in their host regions. Coates and Humphreys (Citation2001) provide one of the first studies to address these questions in a causal research design. Using strikes/lockouts as an example of unexpected, infrequent events that contribute to situations where there are no sporting events to draw outside visitors to a city, they showed that real income per capita in metropolitan areas did not fall during these periods.

The key rationale behind these findings is the argument of substitution. The majority of consumers are characterized by a fixed budget for leisure (sport) activities. While the presence of sports events may cause individuals to rearrange their spending, they are not likely to add much to it (Siegfried & Zimbalist, Citation2000). Consequently, the literature on the economic effects of sports events is in agreement that if there are positive effects from professional sports, they are likely to be temporally, sectorally and geographically bounded. Using a sample of 37 US cities over the period 1969–97, Coates and Humphreys (Citation2003) demonstrate that professional team sport has a positive effect on earnings per employee in the amusement and recreation sector, but that this effect is offset by a decrease in earnings and employment in other sectors. Furthermore, Baade et al. (Citation2011) analysed 25 years’ (1979–2007) of monthly sales tax data for every county in Florida to show that the games of American college football teams yielded modest gains of about US$2 million in taxable sales in host cities, while men’s basketball games did not. The same line of argument can be found in a study on Denmark by Storm et al. (Citation2017), who find that the effect of football and hockey clubs on average income is not significant at the municipal level, while the effect professional handball clubs is positive.Footnote2

Regional (sectoral) effects of professional sports teams can only evolve if the effect of substitution is offset by demand-side effects. Professional sports teams provide a service (Hamm et al., Citation2016; Siegfried & Zimbalist, Citation2000). For the provision of the service, they demand labour (e.g., players, coaches, administrators and managers). The respective employees receive income that – if they live in the same region as the club – they also spend there. Depending on the marginal propensity to consume locally, this creates a direct income effect of professional sports teams on the host region. However, there are further demand-side effects. Clubs use the sports-related infrastructure of a region (e.g., the stadium and the club ground) and make investments to maintain and expand it. As soon as services are purchased from the region, club spending induces additional employment and income effects (Amador et al., Citation2016; Hamm et al., Citation2016; Preuss et al., Citation2010; Roberts et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, local economic effects may arise through visitor spending or sports-related tourism. Home matches of top-division football clubs regularly attract thousands of visitors to the stadiums. Some of these visitors come from the region or city where the sporting event takes place. In this case, regional income is bound in the region. If, however, the games attract visitors from outside regions and if these visitors spend money at the club’s location, then the club’s activity has the characteristics of an export-base sector. Income from outside the region will flow into the region to help secure employment there (see also Hamm et al., Citation2016).

Given this, shocks to professional sports clubs can affect regional growth via the inflow or outflow of extra-regional income and local multipliers of income expenditure (Preuss et al., Citation2010). The existence of such income and multiplier effects has been demonstrated in case study research for different teams in the leagues under analysis (see Roberts et al., Citation2016, for the EPL; Amador et al., Citation2016, for Spain’s La Liga; and Hamm et al., Citation2016, and Könecke et al., Citation2017, for the Bundesliga). Furthermore, Roberts et al. (Citation2016) and Amador et al. (Citation2016) highlight that the (change in the) regional stimulus of a professional football club and the inflow of extra-regional income are exceptionally large in the case of changes in top-division membership. The identification of the net effect of changes in league membership is, however, subject to rigorous empirical analysis. Thereby, the set of theoretical arguments forms the basis for the hypotheses to be tested.

The first hypothesis addresses changes in the economic relevance of professional football clubs because of relegation. The club represents the nucleus of the overall regional effects. Relegations are assumed to contribute to an adjustment in the quality of the game offered to fans (see also Szymanski & Valletti, Citation2005). As a consequence, the club itself will face income losses since the demand for football activities will decline:

Hypothesis 1: Relegations have a negative effect on the income level of a club.

The income effect provides the most direct channel between the relegation decision and aggregate regional effects. However, there are also additional channels through which the relegation shock may translate into regional outcomes. Regular game days are events where regions can benefit from drawing outside visitors to a city. Since these consumers of professional sport events have a specific consumption pattern, the effect of relegation is assumed to have a specific sectoral pattern. The literature on football trip-related spending highlights that consumption-related sectors such as providers of food and drinks (bars, restaurants), the accommodation and transport sector as well as retail businesses (Amador et al., Citation2016 Könecke et al., Citation2017; Preuss et al., Citation2010; Roberts et al., Citation2016) are most likely to benefit from the inflow of income. This implies that the direct consequences of less extra-regional income flows are most likely to be concentrated on those sectors in a region. A direct test of this hypotheses puts a high demand on regional-level data about sales and employment in the amusement sector, detailed information on arrivals or overnight stays in the respective region, and would at best cover facilities in direct vicinity to the stadium. However, the study did not have access to these data at the European Union NUTS-3 level. Therefore, the next hypothesis states the following more generally:

Hypothesis 2: Relegations have a negative effect on the sports-related sectors of a region.

Hypothesis 3: Relegations have a negative effect on regional development.

The main task is now to provide empirical evidence for the existence and size of these effects.

EMPIRICAL APPROACH

Identification strategy

While research on the regional effects of professional sports franchises so far has produced consistent results, it becomes apparent that the literature mainly relies on results from major US leagues. However, there remain fundamental differences between the European and the US models of professional sport that may limit the transferability of results to the European context. The US sporting model is characterized by a closed contest that does not allow for year-by-year changes in top-league membership. Hence, empirical identification of the effects of these sporting franchises or (new) stadia on regional outcomes relies mainly on the arrival, departure or presence of teams – from the NFL, NBA, MLB, National Hockey League (NHL), Major League Soccer (MLS), National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) – in the respective regions, or on natural experiments such as lockouts or strikes (Coates & Humphreys, Citation2001).

The pyramid structure of most European professional sporting leagues, however, creates interdependence and exchange between leagues from different levels. In Europe, all teams in a certain discipline belong to a governing body that supervises a strictly defined hierarchy of divisional competitions. At all levels, a predefined number of the lowest performing teams in any given division relegates at the end of the season to the immediate minor league. In an effort to ensure consistency in league size, an equivalent number of top-performing teams from the respective minor league replaces the relegated clubs (European Commission, Citation1998). This hierarchy connects the lowest level of local amateur competition to the highest national level of professional competition (Szymanski & Valletti, Citation2005).

The analysis focuses on the effects of relegations of teams from four top-division football leagues: the EPL, Bundesliga, Serie A and Ligue 1 over the period 1995–2010. In all these leagues, the system of relegation and promotion was applied during the period under study.Footnote3 Systematic evidence on the net effect of the presence of top-division football clubs on regional development is, however, missing so far (Roberts et al., Citation2016). The majority of existing studies use a case-study approach or rely on panel estimations with region fixed effects and some higher level regional trends to perform the analysis. This study, however, uses the relegation decision to develop a regression discontinuity (RD) design.

The RD approach allows endogeneity concerns related to the relegation of a club (e.g., the regional performance may translate into club performance) to be addressed, and to limit the bias of anticipatory effects before relegation. Anticipation effects may result from cases where relegations are a result of the poor long-term performance of clubs during a season (e.g., see the football clubs AC Arles-Avignon in the 2010/11 season, AFC Sunderland and West Bromwich Albion in 2002/03, Derby County in 2007/08 and FBC Unione Venezia in 2001/02). In the RD design, units receive a treatment based on whether the value of an observed covariate is above or below a certain cut-off (Hahn et al., Citation2001; Hausman & Rapson, Citation2017). In this paper, a region is treated if a top-division club in the region has been relegated in a given season to an immediate lower league. The treatment assignment occurs because of the proximity of the treatment assignment variable X to a threshold c. In the present case, X is the difference in points for the club in the region and the first non-relegation rank in the final league table of the season. This procedure sets the threshold c to zero. That is, if the difference in the number of points to the first non-relegation rank X ≥ 0, the region is not treated, and if X < 0, the region faces the relegation of a top-division football club. Table A1 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online explains the approach in detail for the EPL. The same logic holds for the other leagues included in the analysis.

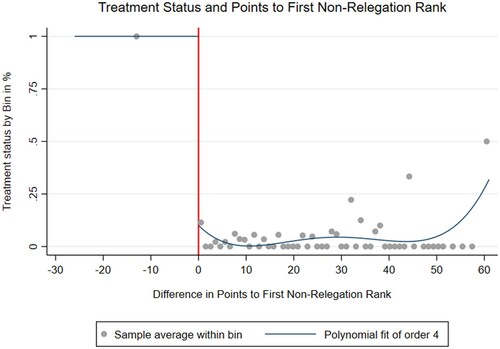

In the absence of clubs finishing the season with a similar number of points, a sharp RD design can be applied, comparing the changes in regional development outcomes of regions with clubs close with the relegation ranks. However, the presence of clubs with the same number points in the final league table and the small share of regions with more than one club playing in the top division of the respective country makes the approach a fuzzy RD design. illustrates the relationship between the assignment variable and the treatment. In the fuzzy RD design, the officially fixed relegation ranks in each league are used to specify the treatment status variable.

Figure 1. Relegation status by bins of size one.

Note: Average treatment rates in equally sized bins of 1 point are shown. The vertical line represents the difference to the first non-relegation rank.

Source: Author’s own illustration.

The proper estimation of the size of the effect in an RD design relies on the continuity assumption. In this case, it requires that regions with clubs just below and just above the relegation ranks have the same potential outcome in the case of relegation. Although this is not directly testable, Lee (Citation2008) demonstrates that if a treatment depends on whether an assignment variable exceeds a known threshold and agents cannot control the forcing variable precisely, the continuity assumption is satisfied since the variation in treatment around the cut-off is randomized.

This lack of control is a reality and precisely what makes the drama of most relegation decisions. The nature and uncertainty of outcome on the final game days ensures that clubs close to the relegation ranks have imprecise control over the difference in points between the relegation and non-relegation ranks. This is because the difference can change even until the final whistle on the final game day. For this reason, a close relegation decision to produce exogenous shocks to the regions of the relegated clubs is assumed. Nevertheless, the randomization assumption implies that whether regions with relegated and non-relegated clubs as well as those clubs close to the relegation ranks are similar can be tested. Thereby, the similarity between the two groups of clubs is the result of the randomization (Lee, Citation2008). This test will be part of the third section below.

Given the exogeneity of relegation ranks and the non-deterministic relationship between relegation ranks and treatment, the treatment effect is estimated within a fuzzy RD design. A robust data-driven inference procedure for the estimation is made use of by using local polynomial regressions, as suggested in the recent econometrics literature (Calonico et al., Citation2014, Citation2015).

Data and outcomes

The analysis relies on data from various sources. First, attendance and final league table data are taken from http://www.european-football-statistics.co.uk/. The attendance data are combined with regional information from the clubs’ NUTS-3 region. The European Regional Database of Cambridge Econometrics provides the regional data. This database offers a wide-ranging, subnational (up to NUTS-3), pan-European Union database of economic indicators. It allows a complete and consistent, historical time series of data for the period of analysis (1995–2012) to be accessed. In this way, the regional (NUTS-3) and sectoral disaggregation represent the most detailed information available for European regions. Both data sets are merged by the location (NUTS-3 code) of the clubs under analysis.Footnote4

The data set allows working with information from the 1995/96–2010/11 seasons. The year 1995 was chosen for the start for reasons of German reunification: in line with the reunification of the two parts of the country, there was a unification of the two formerly independent football leagues. The presence of former GDR Oberliga clubs contributed to the introduction of an integration scheme between the two leagues, starting in the season 1991/92 and ending in 1993/94. In the following season of 1995/96, the German football league introduced the three-point rule. This meant that from that season onwards clubs would receive three instead of two points per win. Hence, by conducting the analysis from the 1995/96 season, one can work with a consistent application of the three-point rule across all leagues under analysis and avoid endogeneity issues related to the presence of former GDR Oberliga clubs in the Bundesliga.

A total of 16 seasons in four leagues were analysed, leading to 1202 observations and including 218 relegations. The data for all seasons were pooled. In the observation period, a total number of 151 clubs from 128 NUTS-3 regions participated in the respective top divisions.Footnote5 Of these 128 NUTS-3 regions, 23 (18.0%) had never seen clubs relegated to the second division in the period of analysis. A total of 43 NUTS-3 regions (36.7%) experienced this event once, 36 NUTS-3 regions twice (28.9%), 12 regions three times (11.7%) and 14 regions (6.3%) more than three times.

The hypotheses require empirical tests on two different levels of analysis. The club represents the first level of analysis. If relegation does not affect a club’s income, regional effects are unlikely. As mentioned above, the case study literature shows that relegations have a direct negative impact on the club’s television receipts as well as on sponsorship income. However, there is no access to detailed club-level data. Instead, the focus is on live attendance at home games that is largely an expression of interest for the club (Simmons, Citation1996). Furthermore, this indicator is of importance because outside visitors to a region are the primary driver of economic impact in recent empirical studies (Coates & Humphreys, Citation2001).

The regional outcomes involve employment and GVA growth in football-related sectors in the NUTS-3 region in which the club is located. In line with the consumption pattern of football spectators, the wholesale, retail, transport, accommodation and food services, and information and communication sectors (the most detailed sectoral disaggregation in the Cambridge Database) are considered to have the closest links to football-related activities (see also Coates & Humphreys, Citation1999, Citation2003, for a similar approach). The second regional outcome addresses the overall regional level. Here, the mean growth of employment and GVA in the period t – 1 to t + 1 of relegation are used. This procedure results mainly from the fact that the only available data are calendar year data, which does not match football season data.

presents pre-relegation differences in means between regions with relegated and non-relegated clubs for selected variables.Footnote6 The mean comparison between both groups shows that relegated teams perform worse in attracting attendance to the stadium. The regional characteristics (calculated for the year in which the season started) also differ across the two groups. For the overall regional size (population and active population), regions with non-relegated teams are significantly larger, indicating the presence of greater market potential. The same holds true for the sectors related to football activities. Here, regions with non-relegated teams display significantly larger means. The differences clearly point towards differences in regional economic potential as a source of endogeneity bias.

Table 1. Sample properties of pre-relegation characteristics.

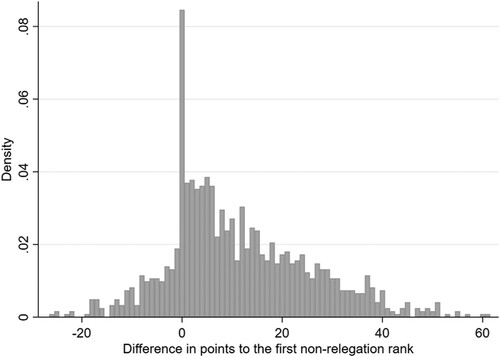

displays the density distribution of the sample by differences in points to the first non-relegation rank. The density distribution is obviously lower on the left-hand side of the cut-off because of the smaller number of relegated teams than non-relegated teams. The highest densities in cases of relegation are given for a zero difference in points to the first definite relegation rank. However, overall, 278 observations (23.1%) can be found in the range of −3 to +3 points around the first non-relegation ranks in all four leagues in the sample period. Given this fact, many regions are indeed threatened by the relegation of a top-division club until the final match day of the season.

Randomization assumption of the RD design

The randomization assumption in RD designs implies that whether regions with clubs close to the relegation ranks are a more appropriate control group and similar in dimensions related to the outcomes of interest can be tested. While indicates significant differences in the sample properties of regions when considering all observations for regions with relegated and non-relegated clubs, highlights that these differences become insignificant around the cut-off. Seven different indicators are used to illustrate this. The results in are estimated using local polynomial and partitioning methods as proposed by Calonico et al. (Citation2014, Citation2015).

Table 2. Testing for regional differences around the cut-off before treatment.

The tests for differences at the club and regional levels consider the pre-relegation differences in mean attendance at home games in the season of the relegation. Hence, it is tested whether clubs around the cut-off differ with respect to attractiveness to fans during the season of relegation. The study also tested for differences in regional characteristics such as market size by using total population, total active population, total regional employment and total regional gross value. Furthermore, the attractiveness of the sports-related economic sectors of the regions was considered by testing for differences in the absolute size of these sectors in terms of GVA and employment, the base for the growth rates analysed in this paper. In all these cases, no significant differences between the characteristics of regions and clubs (attendance) around the cut-off were found. This implies that NUTS-3 regions hosting a top-division football club that is working against relegation in one of the four leagues under analysis are an appropriate control group with regard to the indicators analysed in .

RESULTS

Baseline results

Effect of relegation on the demand for live attendance

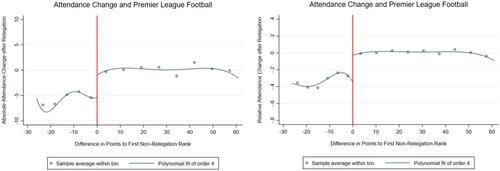

After having demonstrated that the research design contributes to the construction of a credible control group, this section now discusses the results. It starts with the demand for live attendance in the stadium. It first presents visual evidence with data-driven RD plots using evenly spaced binning and, second, estimates the results using a clubs change in the average absolute and relative number of live spectators at home games in the season following relegation (Calonico et al., Citation2014). A negative coefficient in the regressions implies that relegated clubs suffered from attendance losses more than non-relegated clubs close to the cut-off. illustrates the relationship between the absolute (left-hand side of ) and the relative development (right-hand side of ) of attendance in relation to the difference in points to the first non-relegation rank using a fourth-degree polynomial on either side of the cut-off. Both plots indicate that there is a considerable jump in attendance change at the cut-off value.

Figure 3. Regression discontinuity (RD) plots using club-level attendance data as an outcome.

Source: Author’s own illustration.

This visual interpretation is confirmed by the econometric estimates (cf. ). The findings give support to the results of Simmons (Citation1996) for the more general sample of four major European football leagues. They highlight that demand for live attendance is very elastic to changes in league membership. The size of the effects suggests that relegation contributes to a substantial loss in the income base of former top-level football clubs. Although showing similar attendance figures during the season of relegation (cf. ), relegated clubs face an average reduction of −4.254 (in thousands) spectators per home game in the season onwards. The coefficients for relative changes in inter-seasonal attendance also indicates this negative and highly significant effect. Here, estimates show a reduction in live attendance of about 28.7%. Given that teams in these four leagues have between 17 and 19 home games per season, relegations create a substantial and continuous loss of demand for football-related activities in a region over the entire following season.

Table 3. Effects of relegation on the demand for live attendance in the stadium.

These results confirm Hypothesis 1. The relegation affects the income level of the club negatively. The negative income effect via fewer spectators is most likely accompanied by further losses in club-level income through lower television receipts or sponsorship. Altogether, this provides a source of negative local economic effects of relegation. As stated above, local multiplier effects arise if relegations lead to changes in income that flows into the region or via the rearrangement of the spending by persons within the region. In the present case, the results indicate that clubs lose their relevance as an export-base sector with smaller inflows of extra-regional income to the region.

Effect of relegation on football-related sectors in a region

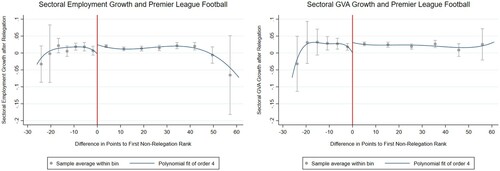

The next step shifts the focus to the more aggregated level of the region. First, it follows the hypothesis of Feddersen and Maennig (Citation2012) that any economic impact from major sporting events might be spatially, temporally and sectorally localized. It tests this hypothesis based on employment and GVA growth rates for the aggregate figures of the wholesale, retail, transport, accommodation and food services sector at the NUTS-3 level. Again, the paper starts with a visual representation of the results and then reports regression estimates in .

Table 4. Estimation of the effects of relegation on football-related sectors in the region.

In line with the results for live attendance, regional sectoral outcomes also seem to respond negatively to relegation shocks. indicates small decreases in the growth rates at the cut-off. supports this finding. The estimations show a significant negative short-term effect of the relegation on both dimensions of regional sectoral outcomes. First, regional sectoral employment growth in football-related sectors decreases by about 2.7 percentage points in regions facing relegation. In addition, the effect on regional sectoral growth in GVA is negative and significant. Here, the effect size is about −3.0 percentage points. Hence, Hypothesis 2 is confirmed as well as the results of Feddersen and Maennig (Citation2012) that short-term sectoral employment and GVA effects of large sporting events exist for the set of regions under analysis.

Figure 4. Regression discontinuity (RD) plots using regional sectoral development as an outcome.

Source: Author’s own illustration.

Potential drivers of these effects may include intra-regional displacement effects. In this case, the income that was bound in the football-related economy could be shifted to alternative offers (in the same or in other regions) with lower demand for products or services of the football-related economy. Furthermore, as stated above, especially the football-related sectors might lose their export base since declining income flows from outside the region lead to lower income effects in the region.

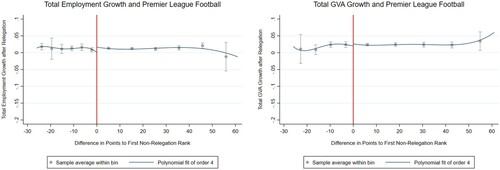

Effect of relegation on overall regional development

While research has provided support for the presence of regional, sectoral effects of sporting events, scholarly analysis has so far found almost no evidence for the relevance of such events on aggregated regional outcomes (Coates & Humphreys, Citation2008). This question is addressed here by estimating the model on overall short-term regional employment and GVA growth. shows the results. The comparability of the effect size between and is ensured by using the similar scale of the legend. also indicates a small decrease in the regional growth rate at the cut-off, which points to total regional employment effects of relegation. However, in the case of the growth of total regional GVA, the polynomial specification does not seem to indicate any effect of relegation.

Figure 5. Regression discontinuity (RD) plots using total regional development as an outcome.

Source: Author’s own illustration.

The respective regression results are illustrated in . In contrast to the results observed at the club and sectoral level, the effects are less clear for the overall regional level. Note that the specification for overall regional employment growth shows a small negative effect of about −1.3 percentage points. However, relegation has no effect on regional output growth. This means there may be some negative effects on regional employment, but, in line with the literature, relegations appear to be events of minor importance for short-term regional output growth. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 can only be partially confirmed.

Table 5. Estimation of the effects of relegation on football-related sectors in the region.

The reason for these results appears to be that sectoral shocks, as well as the overall income and multiplier effects, are not large enough to translate into aggregated results. One reason for this may be found in the process of substitution. Relegations can trigger the rearrangement of income expenditures from persons within the region into other sectors of the same region. This seems to be the case in the present study. The results imply that relegation has a positive effect on the productivity of the non-football sectors in the same region.Footnote7

CONCLUSIONS

This study is the first to test for regional (sectoral) growth effects of relegations of top-division football clubs in four major countries in Europe. To date, studies have mainly focused on regional, sectoral or temporal effects of mega-sporting events such as the FIFA World Cup, the UEFA European Football Championship and the Olympic Games, or on regional effects of the arrival, presence and departure of American sports franchises in the NFL, NHL, MLB or NBA using modern panel approaches.

The particularity of the European sports system is used and the design of the relegation mode to develop an RDD is relied upon. The effects using local polynomial regressions as proposed by Calonico et al. (Citation2014, Citation2015) are estimated. Significant negative effects of the relegation of a top-division club on its income level, as well as on short-term regional sectoral employment and GVA growth, are found. These results contribute to the literature on the economic relevance of major sporting events. It is important to understand the regions’ response to relegation shocks, as shocks will be significantly felt in the regions. As far as football is concerned, the basic underlying mechanisms are the income effects and the process or intra-regional substitution. The results highlight the fact that not only players, fans and club employees, but also pub and restaurant owners as well as owners of accommodation facilities in the region face the burden of relegation.

The results also show that there are small general effects of relegation on overall regional development. Overall employment reacts more sensitive to relegation than overall GVA growth. This makes the non-football-related sectors a short-term beneficiary of relegation through rising productivity. The process of substitution favours these sectors. The results therefore show some parallels between the relegation of a football club and the regional effects of the closure of large companies or adverse shocks to industries that have important regional effects. As a consequence, local policy-makers often provide public support to private professional football clubs in order to keep the clubs in the top division (e.g., provision of stadia and infrastructure as well as sponsorship from public enterprises) and of alleviating the effects for their electorates.

Whether such support improves welfare depends on the effects and persistence of the underlying relegation shocks. As output effects of relegations were not found in the analysis, there are clear doubts about the effectiveness of such measures in the short-term. The negative output effects in football-related sectors are likely to be offset by positive effects in the non-football economy. However, short-term sectoral labour market efforts could be one way to address labour market problems.

The results of this study can, therefore, serve as a starting point for future research. This research needs to address more directly the channels behind the net effects of relegation on regional development. So far, the findings of this paper offer only limited explanations for the specific role of the different channels. Therefore, it seems necessary, first, to identify the direct monetary effects of relegations on the incomes of clubs, players and club employees and, second, to determine to what extent these income losses (or gains in the case of promotions) lead to local multiplier effects. This is of particular relevance in the analysis of the regional effects of professional sports since especially players are characterized by a low marginal propensity to consume at the local level. In addition, further insights on channels can be derived from in-depth studies on sport-related tourism patterns. The research in this field has mainly focused on questions such as how often people travel to cities with top football clubs, how often they stay overnight there, and how their spending behaviour changes as a result of relegation. Detailed systematic studies on arrivals, overnight stays and the spending behaviour of sports tourists can provide valuable and policy relevant insights into this channel. This also holds true for research on the role of local ownership in sport-related sectors (especially bars, restaurants and accommodation facilities), and on the consumption behaviour of people in the host region of the clubs. The literature on leisure expenditure is mainly concerned with substitution. It is emphasized that it is likely that substitution plays a role in this context, but it cannot show which actors directly benefit/suffer from relegation. This lack of identification of the relevance of the different channels is a clear weakness of the empirical approach and requires complementary quantitative and qualitative work that provides deeper insights into relegation-related changes in the consumption behaviour of local and non-local football-related actors.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (202.8 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author thanks Steffen Mueller, Mirko Titze, Claus Michelsen, Tom Broekel and two anonymous referees whose comments greatly improved the paper. Also thanked is Alexander Giebler for great research assistance.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. See Gabaix (Citation2011) for the more general granular hypothesis.

2. Feddersen and Maennig (Citation2012) use the FIFA World Cup in 2006 in Germany to confirm the presence of small positive short-term effects on certain sectors in the host regions. Feddersen and Maennig (Citation2013) demonstrate that the effect of the Atlanta Olympic Games in 1996 was sectorally and regionally bounded. Richardson (Citation2002) finds that sports-related variables have a slight statistically positive effect on both real per capita personal income and its growth in the United States.

3. There remain differences across leagues regarding the number of relegation ranks and the size of the league.

4. Standard Eurostat or Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) regional-level data do not allow for such a finely grained analysis.

5. Of these 151 clubs, 42 (27.8%) never experienced relegation during this period. Fifty clubs (33.1%) experienced relegation once, 37 clubs twice (24.5%), 15 clubs three times (9.9%) and seven clubs more than three times (4.6%).

6. Regions appear more than once in each group. The sample properties are calculated for the pooled version of the data.

7. The results are robust to several data manipulations and the exclusion of outliers. For the robustness checks, see Appendix B in the supplemental data online.

REFERENCES

- Amador, L., Campoy-Muñoz, P., Cardenete, M. A., & Delgado, M. C. (2016). Economic impact assessment of small-scale sporting events using social accounting matrices: An application to the Spanish football league. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 9(3), 230–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2016.1269114

- Baade, R. A., Baumann, R., & Matheson, V. A. (2011). Big men on campus: Estimating the economic impact of college sports on local economies. Regional Studies, 45(3), 371–380. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400903241519

- Baade, R. A., & Dye, R. F. (1990). The impact of stadiums and professional sports on metropolitan area development. Growth and Change, 21(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2257.1990.tb00513.x

- Baade, R. A., & Matheson, V. (2016). Going for the gold: The economics of the Olympics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(2), 201–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.2.201

- Baade, R. A., & Sanderson, A. R. (1997). The employment effect of teams and sports facilities. In R. G. Noll, & A. Zimbalist (Eds.), Sports, jobs and taxes: The economic impact of sports teams and stadiums (pp. 92–118). Brookings Institution.

- Borland, J., & MacDonald, R. (2003). Demand for sports. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 19(4), 478–502. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/19.4.478

- Calonico, S., Cattaneo, M. D., & Titiunik, R. (2014). Robust nonparametric confidence intervals for regression-discontinuity designs. Econometrica, 82(6), 2295–2326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA11757

- Calonico, S., Cattaneo, M. D., & Titiunik, R. (2015). Optimal data-driven regression discontinuity plots. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 110(512), 1753–1769. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2015.1017578

- Coates, D. (2015). Growth effects of sports franchises, stadiums, and arenas: 15 Years later (Mercatus Working Paper), Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

- Coates, D., & Humphreys, B. R. (1999). The growth effects of sport franchises, stadia, and arenas. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 18(4), 601–624. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6688(199923)18:4<601::AID-PAM4>3.0.CO;2-A

- Coates, D., & Humphreys, B. R. (2001). The economic consequences of professional sports strikes and lockouts. Southern Economic Journal, 67(3), 737–747. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1061462

- Coates, D., & Humphreys, B. R. (2003). The effect of professional sports on earnings and employment in the services and retail sectors in US cities. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 33(2), 175–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-0462(02)00010-8

- Coates, D., & Humphreys, B. R. (2008). Do economists reach a conclusion on subsidies for sports franchises, stadiums, and mega-events? Econ Journal Watch, 5, 294–315.

- Deutsche Fussball Liga (DFL). (2017). Die wirtschaftliche situation im Lizenzfussball. DFL.

- European Commission. (1998). The European model of sport (Consultation Paper of DGX). European Commission.

- Feddersen, A., & Maennig, W. (2012). Sectoral labour market effects of the 2006 FIFA World Cup. Labour Economics, 19(6), 860–869. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2012.07.006

- Feddersen, A., & Maennig, W. (2013). Mega-events and sectoral employment: The case of the 1996 Olympic Games. Contemporary Economic Policy, 31(3), 580–603. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7287.2012.00327.x

- Gabaix, X. (2011). The granular origins of aggregate fluctuations. Econometrica, 79(3), 733–772. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA8769

- Hahn, J., Todd, P., & van der Klaauw, W. (2001). Identification and estimation of treatment effects with a regression-discontinuity design. Econometrica, 69(1), 201–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00183

- Hamm, R., Jäger, A., & Fischer, C. (2016). Fußball und Regionalentwicklung. Eine Analyse der regionalwirtschaftlichen Effekte eines Fußball-Bundesliga-Vereins – dargestellt am Beispiel des Borussia VfL 1900 Mönchengladbach. Raumforschung and Raumordnung, 74(2), 135–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13147-016-0389-4

- Hausman, C., & Rapson, D. (2017). Regression discontinuity in time: Considerations for empirical applications (Working Paper Series No. 23602). National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

- Könecke, T., Preuss, H., & Schütte, N. (2017). Direct regional economic impact of Germany’s 1. FC Kaiserslautern through participation in the 1. Bundesliga. Soccer and Society, 18(7), 988–1011. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2015.1067786

- Lee, D. S. (2008). Randomized experiments from a non-random selection in U.S. House elections. Journal of Econometrics, 142(2), 675–697. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2007.05.004

- MacDonald, G. (1988). The economics of rising stars. American Economic Review, 78, 155–166.

- Maennig, W. (2017). Major sports events: Economic impact (Hamburg Contemporary Economic Discussions No. 58).

- Preuss, H., Könecke, T., & Schütte, N. (2010). Calculating the primary economic impact of a sports club’s regular season competition: A first model. Journal of Sport Science and Physical Education, 60, 17–22.

- Richardson, S. (2002, February). Revisiting the income and growth effects of professional sport franchises: Does success matter? SSRN Electronic Journal. doi: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.968521

- Roberts, A., Roche, N., Jones, C., & Munday, M. (2016). What is the value of a Premier League football club to a regional economy? European Sport Management Quarterly, 16(5), 575–591. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2016.1188840

- Rosen, S. (1981). The economics of superstars. American Economic Review, 71, 845–858.

- Siegfried, J., & Zimbalist, A. (2000). The Economics of sports facilities and their communities. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(3), 95–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.14.3.95

- Simmons, R. (1996). The demand for English league football: A club-level analysis. Applied Economics, 28(2), 139–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/000368496328777

- Storm, R. K., Jakobsen, T. G., & Nielsen, C. G. (2019). The impact of Formula 1 on regional economies in Europe. Regional Studies. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1648787

- Storm, R. K., Thomsen, F., & Jakobsen, T. G. (2017). Do they make a difference? Professional team sports clubs’ effects on migration and local growth: Evidence from Denmark. Sport Management Review, 20(3), 285–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2016.09.003

- Szymanski, S., & Valletti, T. M. (2005). Promotion and relegation in sporting contests. Rivista di Politica Economica, 95, 3–39.

- Värja, E. (2016). Sports and local growth in Sweden: Is a successful sports team good for local economic growth? International Journal of Sport Finance, 11, 269–287.