ABSTRACT

This paper shows how certain spatial logics are used to support contemporary region-building processes, and how these become taken for granted and institutionalized in specific regional settings. These spatial logics are also representative of the spatial logics dominating contemporary regionalism and affect the ways ‘spaces’ and ‘citizens’ are treated and valued in regional planning and policy. Few studies have shown how spatial logics are implemented, transformed and turned into policy across a wider set of regions. Exemplified by The Scandinavian 8 Million City project, the paper shows how this regional imaginary was constructed by the project promotors using several representative spatial logics of what constitutes the ‘best’ region as idealized in planning and policies.

INTRODUCTION

The debate over regions and their meanings has a long history within regional geography and regional science. Historically, depending on the context in which they were studied, regions were either defined as political units, demarcated by administrative and political borders, or based on their cultural or natural settings. Today, this is considered a simplistic view of regions. Rather than being accepted as a natural unit of analysis, the intent is to explain the social processes forming contemporary regions, which has become a complex issue. Efforts to redefine regions and the growth of new categories, such as city-regions, megaregions and networked regions, have contributed to new meanings for already abstract definitions. However, a common viewpoint is that regions are historically contingent processes that are always ‘in the becoming’ (Pred, Citation1984). From this perspective, regions are not fixed territorial entities but are instead under constant change in time and space (Amin, Citation2002, Citation2004). This is consistent with Massey’s (Citation1991) relational view on space, which defines regions as entities shaped by social relations and networks made up of complex linkages between places, power and people. In the policy debate, however, regions ‘out there’ are still treated as what might be understood as ‘spatial fetishism’; in other words, regions are treated as real actors, given specific qualities and taken for granted ‘as a (bounded) setting or background for diverging social processes’ (Paasi & Metzger, Citation2017, p. 24). Spatial fetishism occurs in a variety of fields from research, media, education, planning and policy, in which the focus is on, for example, learning regions, entrepreneurial regions or competitive regions. Hence, regions are treated as actors that can make decisions, compete or promote themselves. Other forms of spatial fetishism are the ways city-regions, global cities (e.g., Calzada, Citation2015; Harrison & Growe, Citation2014; Sassen, Citation2002) and other large-scale urban areas are portrayed as drivers of economic growth and development, and advanced by both local and regional policy-making and planning (Harvey, Citation1989). For instance, global cities and larger city-regions came to represent a new spatial logic within planning and policy-making in the beginning of the 2000s, being seen as nodes in transnational networks binding together larger city-regions and making them competitive and attractive for investments, talents and global capital (Olesen & Richardson, Citation2012; Sassen, Citation2002). As a result, new understandings about space and place have enabled a new vocabulary in which networks, corridors, hubs, zones and soft spaces are frequently used to support the development of specific region-building processes (Paasi & Zimmerbauer, Citation2016). Hence, today’s region-building processes are the result of the interplay of regional imaginaries and spatial fetishisms, political projects, and institutional arrangements supported through examples of best practices for regional growth and development. From this perspective, regions are emerging from the intersecting trajectories of ideas, policies, individuals and other resources in their making (Wetzstein & Le Heron, Citation2010).

Against this background, the aim of this paper is to show how certain spatial logics are used to support specific region-building processes and how these become taken for granted and institutionalized in a specific regional setting. These spatial logics are also representative of the spatial logics dominating contemporary regionalism and affect the ways ‘spaces’ and ‘citizens’ are treated and valued in regional planning and policy. Few studies have shown how spatial logics are implemented, transformed and turned into policy across a wider set of regions (e.g., Harrison & Growe, Citation2014; Hidle & Leknes, Citation2014; Olesen & Richardson, Citation2012). Thus, it is necessary to highlight cases from different geographical contexts to broaden our understanding of the evolving imaginaries and spatial logics of contemporary regionalism and region-building processes. Inspired by the policy mobility literature, a field that highlights the ways successful policy models, planning and best practices travel, trickle down, transform and are renegotiated in regional settings that are here interpreted as wider spatial logics of contemporary regionalism. In this paper, this is exemplified by The Scandinavian 8 Million City project, which started as an Interreg project in the early 2000s with the aim to develop a common infrastructure corridor to bind the larger cities (i.e., Oslo, Gothenburg, Malmö and Copenhagen) into a larger networked megaregion. Since this particular region-building process aimed to construct a larger megaregion, one part of the process was to create a regional imaginary of the region ‘in becoming’. The regional imaginary was also constructed by the project promotors using several representative spatial logics for successful regions from a variety of contexts. The paper aims to answer the following research questions:

What were the dominant spatial logics in this region-building process?

How do these spatial logics relate to other contemporary region-building initiatives and regionalization processes?

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. A theoretical overview of the literature on regionalism and regionalization processes is presented in the following section. The concept of ‘spatial logic’ is then used as an analytical tool to link the circulating political and academic imaginaries, policy models, political initiatives and particular policy rationales (Wetzstein & Le Heron, Citation2010) on contemporary regionalism. The methods section describes the methods and empirical material used in the study, while the results section presents the spatial logics that were used, transformed and renegotiated to support the region-building process of The Scandinavian 8 Million City project. The paper concludes with a final discussion of the dominant spatial logics in The Scandinavian 8 Million City project in relation to contemporary regionalism and regionalization processes.

WHAT KIND OF REGIONALISM?

Gregory (Citation1978) used the ‘fetishism of area’ concept to describe the phenomenon of treating regions as actors that are interrelating with other regions, as if they are acting apart from the social world. This type of spatial fetishism is especially reflected in today’s political rhetoric on the increased competition between places (Paasi & Metzger, Citation2017). In the following text, the concept of spatial logic will be used to address the common spatial fetishisms and spatial frames used in contemporary regionalism and region-building processes (e.g., Hidle & Leknes, Citation2014; Olesen & Richardson, Citation2012). Inspired by the policy mobility literature, where spatial reference points, narratives and political rhetoric are used as political strategies to frame problems and persuade policy-makers and the general population of the benefits of particular solutions (McCann, Citation2017), this is here linked to the spatial logics used to support contemporary regionalization processes. In a similar manner, in their study of Norwegian city-regions, Hidle and Leknes (Citation2014) discussed regionalism in terms of treating regions as tools for activating certain ends, goals and objectives, where strategies and policies were directed to a specific regional setting. They defined regionalism as a bottom-up process driven by local actors and regionalization as a top-down process driven by state actors. Regionalism is also defined as a political process driven by specific actors to maintain, enhance or develop social structures containing normative and discursive assumptions, reference points and political strategies supporting specific region-building processes. As such, regionalism is not a new phenomenon, that is, it has been coloured by different political ideologies and planning discourses throughout history (Harrison & Growe, Citation2014). For instance, scholars differed between an ‘old regionalism’ and a ‘new regionalism’ occurring before and after the 1970s. During the first half of the 20th century, the old regionalism was primarily a manifestation of a state-centred Keynesianism used to create regional convergence and redistribution of economic resources. The old regionalism often built on regional differences, such as a strong divide between the centre and its periphery, or between strong cultural and identity tiers, such as a common language, religion or other cultural signifiers within a specific region (Keating, Citation1998, Citation2001; Syssner, Citation2002, Citation2006). In turn, new regionalism developed together with the growth of neoliberalism in the 1970s as represented by increased globalization, deregulation, privatization and a decentralization of the nation-state in which the regional scale was identified as a suitable geographical scale for rolling out economic growth and development (Brenner & Theodore, Citation2002, Citation2005). Consequently, and especially from the 1980s, economic interests pushed a new regionalism agenda within many European countries and responsibility for economic development and growth was decentralized to the regional level, leading to increased regionalization. During that period, scholars also wrote about the ‘renaissance of the regions’ (Törnqvist, Citation1998) or an ‘Europe of the regions’ (Harvie, Citation2004; Storper, Citation1995).

A critique of new regionalism as an explanatory term evolved during the 1990s, consisting of multiple and diverse theoretical definitions that hollowed out the explanatory vigour of both regions and regionalism (Harrison, Citation2008). In addition, many explanations of new regionalism had a strong focus on regions as subnational units (Keating, Citation1998), but the latest round of territorial restructuring concerns instead the growth of new regional constellations with relatively vague borders including, for example, the growth of city-regions, cross-border regions and polycentric megaregions (Harrison & Growe, Citation2014; Hincks et al., Citation2017). These new regions are often referred to as ‘soft spaces with fuzzy boundaries’ (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009). Also, the Regionalism 2.0 concept (e.g., Andrew & Ward, Citation2007; Harrison & Growe, Citation2014; Jonas, Citation2012) was used to explain the shift towards city-regions as the ideal territorial shape for further developing capitalism and economic growth (Brenner, Citation2004; Brenner & Theodore, Citation2005; Bristow, Citation2010), where larger city-regions were seen as growth engines and global economic nodes (Sassen, Citation2002).

SPATIAL LOGICS IN CONTEMPORARY REGIONALISM

As shown above, contemporary regionalism and regionalization processes show traces of several spatial logics, which will be presented below (). These multiple spatial logics are elaborated on in the literature (e.g., Hidle & Leknes, Citation2014; Olesen & Richardson, Citation2012) and were also identified as highly relevant tools for the analysis of the case under study. To some extent the different logics are overlapping and intertwined in time and space. In the following text these logics are also presented in relation to economy, scale and politics and are interpreted as key drivers for contemporary regionalism and regionalization processes. At more general levels, these spatial logics are also used by, for example, planners, local and regional development actors and politicians as motivations for why to do certain things, for example, support investments in large-scale infrastructure and flagship projects, invest in urban versus rural areas, invest in place-marketing campaigns or, as in this case, frame a specific region-building project (Brenner, Citation2004; Bristow, Citation2010; Kornberger & Carter, Citation2010; Wachsmuth, Citation2017).

Table 1. Dominant spatial logics in contemporary regionalism.

Economic and territorial competitiveness

One of the spatial logics driving contemporary regionalism and regionalization processes is economic and concerns territorial competitiveness, in which nations, cities and regions are portrayed as competitors that ‘compete’ to attract talents, private and public investment, visitors, new inhabitants, firms and industries (e.g., Hidle & Leknes, Citation2014; Wachsmuth, Citation2017). Hence, an important part of today’s state development includes strategies to maintain state competitiveness, including a wide range of space-making activities (Moisio & Paasi, Citation2013). As such, the idea of increased competition between places goes hand in hand with previous and ongoing globalization processes and the continuous internationalization of the market. An early result of this logic was the reorientation of spatial Keynesianism and a more balanced regional and economic development towards more growth-oriented planning and policy approaches, especially supporting the development of larger city-regions (Brenner, Citation2004; Harvey, Citation1989). Part of the expanding logic on competitiveness is also the development of policy to accelerate ‘soft (city) regional spaces’ that can stimulate economic growth and competitiveness (Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2020, p. 776). In a similar manner, in their study of the development of strategic spatial planning in Denmark, Olesen and Richardson (Citation2012) identified an emerging neoliberal agenda promoting a growth-oriented policy and planning approach. This agenda also emphasized economic and territorial competitiveness with a focus on growth centres in major cities and urban regions. In addition, the spatial logic of economic and territorial competitiveness is advanced through a wide range of policies, as a response to perceived threats, problems or challenges in a world of global competition (Brenner & Wachsmuth, Citation2012) where other spatial logics representative of contemporary regionalism become either solutions or threats to the competitive state. Typically, these more growth-oriented policies and strategies are not associated with current systems of local government, and they require new ways of working and new constellations of actors (Allmendinger et al., Citation2015).

Imaginaries on large-scale urban regions

The second spatial logic is mainly related to scale, that is, it concerns ideals and imaginaries regarding large-scale megaregions as well as functional regions and ‘soft spaces’ (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009; Hincks et al., Citation2017). This logic is mainly an expression of ongoing rescaling processes to adapt territories to fit the international market (Harrison, Citation2007). Hence, this logic favours both city-regionalism, the growth of megaregions and new transnational regions supporting growth at both the regional and national levels (e.g., Hincks et al., Citation2017). This logic also incorporates planning ideals such as polycentrism, increased mobility, networked regions, urban growth, economic development and the growth of new networks and supranational relations (e.g., Healey, Citation2013; Neuman & Zonneveld, Citation2018; Paasi & Zimmerbauer, Citation2016; van Straalen & Witte, Citation2018). Similarly, the megaregion concept is supported by a strong geoeconomic logic enhanced by a rhetoric of economic boosterism and neoliberal pro-growth models of how economic development and competitiveness should be achieved in a rapidly changing global economy. This development was also supported by powerful interest groups, including federal and state governments, business and industry leaders, private investment groups, and real estate developers. Research shows that these actors mobilize to support the development of megaregions when they see the potential for planning on this scale to defend and enable their own essential interests (e.g., decisions regarding high-speed rail routes or other large-scale infrastructure projects) to prioritize funding and expansion (e.g., Harrison & Hoyler, Citation2015; Wachsmuth, Citation2017).

Part of this logic is also the constant use of successful examples of larger functional regions as ideals and norms for planning. Examples often used in both literature and policy are Silicon Valley in the United States and the Blue Banana, that is, ‘the backbone of Europe’ (Jensen & Richardson, Citation2004; Richardson & Jensen, Citation2000). The use of ideas from these ‘ideal regions’ increased in regional policy and planning from the beginning of the 2000s. There was also growth in what Deas and Lord (Citation2006, p. 1848) called ‘unusual regions’ or ‘soft spaces’ that lacked any formerly known administrative borders but were defined instead by functional and ‘fuzzy borders’ and comprised new regional coalitions and institutions (Allmendinger et al., Citation2015; Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009). The development of these unusual regions with rather vague borders, for example, local and regional labour markets or flows of trade in goods, services, shopping or other economic activities, is often the result of growth policy directed towards the development of functional regions and city-regions (e.g., Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009; Paasi & Zimmerbauer, Citation2016; Purkarthofer, Citation2018; Syssner, Citation2009).

In addition, European spatial planning policies, such as the European Spatial Development Perspective (ESDP) (European Commission, Citation1999) and the trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) strategy in the transport sector supporting the construction of high-speed railways around Europe (European Commission, Citation1999), have played important roles in advancing the development of urban regions in the European Union (EU) (e.g., Purkarthofer, Citation2018; van Straalen & Witte, Citation2018). As such, the ESDP is an expression of a European vision of an open, cohesive EU, without internal borders and with free movement of people, capital and information. One result of this EU policy has been the linking of larger urban areas to one another in networked regions which stretch national, administrative and political borders (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009), for example, the Oresund region (Ek, Citation2003), the Fourth City region in Sweden (Syssner, Citation2011) or more recent examples such as the Bothnian Arc (Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2020). The aim was to create more balanced development between European regions through a specific focus on polycentrism. However, there are some contradictions with the development of polycentrism in Europe. For example, there is a paradox to enhancing competitiveness and growth in larger city-regions by directing resources and infrastructure projects to these places, while at the same time aiming for economic convergence between more peripheral regions and city-regions (Davoudi, Citation2003; Richardson & Jensen, Citation2003). Polycentrism was originally used as an analytical tool to explain an emerging reality, but within the EU it has instead become a tool to determine that reality (Davoudi, Citation2003) and affects both national and regional policy and planning structures within the EU (Richardson & Jensen, Citation2003). In addition, many local and regional governments used the TEN-T strategy as a new source of funding during a time when resistance to infrastructure development was increasing. This in turn led to a wide range of local and regional cross-border projects around Europe (Jensen & Richardson, Citation2004; Purkarthofer, Citation2018).

Managerial forms of regional policy and planning

Consequently, contemporary forms of regionalism have led to new forms of territorial governance and (re)organization, which affect both regional planning and what regional planners and politicians do. Thus, the third spatial logic is primarily political and regards the ways managerial forms of regional policy and planning are developing. This logic regards the ways regional actors turn regions into marketed products through local boosterism, ranking lists, flagship projects or other forms of branding (Brenner & Wachsmuth, Citation2012). This is also illustrated by the ways in which regional policies, strategies and visions are used to brand regions. Today, the work of regional practitioners and policy-makers includes methods for developing and promoting regional brands, brand platforms and other place-branding practices to create and build ‘attractive regions’ (Grundel, Citation2013; Hospers, Citation2006; Zimmerbauer, Citation2011). An important part of this spatial logic was also highlighted in the beginning of the 2000s where a strong regional and cultural identity were believed to strengthen social capital. In turn, a strong social capital was assumed to lead to economic growth and development, enhancing regional attractiveness and competitiveness. Closely linked to social capital was a strong regional identity and image, pushing regional authorities to strengthen the regional culture of more peripheral regions (e.g., Hidle & Leknes, Citation2014; Syssner, Citation2008, Citation2009). Hence, new forms of governance and multilevel governance arrangements, such as public–private partnerships, urban and regional development and growth agencies, place marketing, and new public management are growing. Institutions, political and administrative structures, and power hierarchies involve actors who were previously nonparticipants in policy processes (Allmendinger et al., Citation2015; Bristow, Citation2010). New forms of territorial (re)organization also challenge democratic processes in planning and policy-making (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009; Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2010), favouring consensual, technocratic and growth-oriented approaches (Kenis & Lievens, Citation2017; Swyngedouw, Citation2005; Swyngedouw, Citation2009). Competitiveness, increased individualization, privatization and entrepreneurship have become representative of a new state–citizenship relationship, which can also be seen at the regional level (Dean, Citation2010; Sager, Citation2011; Syssner, Citation2011).

METHODS AND EMPIRICAL MATERIAL

This paper draws on an earlier study conducted during the period 2009–14 (Grundel, Citation2014). It was inspired by political economy and the extended case method (ECM) developed by Peck and Theodore (Citation2015). A combination of methods was used, including participatory observations, document and policy analysis, and in-depth interviews. Participatory observations were made at activities ranging from workshops and breakfast meetings to conferences promoting the idea of and visions for The Scandinavian 8 Million City project. These events were primarily arranged by the project owners. The analysed documents included policy documents, websites, strategies, visions and reports related to the project. Some of these materials dated to the first round of the project in 2000, and others were from the end of the project in 2014.

To complement the policy analysis, 11 interviews with politicians and practitioners from all three countries in the larger region were also conducted. Some of the interviewees were interviewed twice. The interviews were semi-structured and followed predetermined themes. This semi-structured format allowed the interviewer the opportunity to follow-up on other important issues raised during the interviews and allowed the respondents to speak more freely. The interviews were conducted, transcribed and analysed in Swedish. The quotations from both interviews and texts were translated into English by the author.

The analysis of these materials followed discourse analysis, that is, the empirical material were treated and analysed as ‘political’, which means that they have performative power to shape the ways we think, value and understand a specific matter (Hall, Citation1997), here also referring to the ways we understand contemporary region-building processes and regionalism. Both texts and practices were treated as discourse (Fairclough, Citation1992; Richardson & Jensen, Citation2000); therefore, the empirical material not only includes documents and interviews but also the organization and performance of different events. Together, these materials reproduce and express the imaginaries, ideas, norms and values supporting The Scandinavian 8 Million City project (Foucault, Citation2008). First, these materials were analysed to identify common themes in both texts and interviews. Second, they were analysed in relation to the spatial logics identified in the literature and presented in the former section and used to support this particular region-building process. Many of the respondents repeated and copied the same messages from visions, strategies and reports produced by consultants and regional practitioners to support the project. In the following text the spatial logics that were used, transformed and renegotiated in The Scandinavian 8 Million City project are presented.

SPATIAL LOGICS IN THE SCANDINAVIAN 8 MILLION CITY

The first ideas regarding The Scandinavian 8 Million City project date to the first high-speed rail connection between Paris and Lyon in 1981. Three years after its opening, Per Gyllenhammar, then-President of Volvo Cars, presented a vision of a common Scandinavian high-speed rail link. However, it was not until the beginning of the 2000s that the first real collaboration towards the ‘imaginary region’ was initiated. This collaboration was the result of the initiation of the Scandinavian Arena by the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs with political representation from Norway, Sweden and Denmark to increase collaboration between these three countries. Since the start of the project, the region-building process was supported by the EU using its structural funds and Interreg IV A to support cross-border collaborations in the EU. Initially, the project goal was to create a regional growth corridor with excellence in research and innovation within the life sciences by binding the larger cities in the region together into a common labour market. In 2008, there was a shift towards the vision of developing a common infrastructure corridor by the construction of a high-speed railway that could bind the larger cities together into a networked region and an imaginary megaregion, that is, The Scandinavian 8 Million City.

The geographical area of the proposed region extended over 600 km, crossing the three Scandinavian countries, including the three larger cities in the region: Copenhagen, Oslo and Gothenburg (). By the end of the project period (2014), approximately 7.4 million people lived within the borders of the imaginary megaregion (43% in Sweden, 34% in Denmark and 23% in Norway).

Figure 1. Map of the proposed Scandinavian 8 Million City and its 10 administrative regions.

Source: The Scandinavian 8 Million City (Citation2013).

The Scandinavian 8 Million City project was initially set up as a collaboration between the Swedish Ministry of Affairs and representatives from the other Scandinavian countries. Hence, the project was mainly a top-down initiative. From 2008 onward, the project was run by regional and local planners and officials, with the lead partners being Oslo Teknopol, a regional development agency established by the municipality of Oslo, Akershus County Council and Business Region Gothenburg.Footnote1 This also reflects the strong interests from the larger city-regions Oslo and Gothenburg to build an infrastructure corridor that could bind the larger cities in the region together to increase their own territorial competitiveness. Other project members were Oslo, Akershus County Council, Østfold, Västra Götalandsregionen, Region Skåne, Malmö, Helsingborg, the Swedish transport administration, Jernbaneverket,Footnote2 the Norwegian Public Roads Administration, Region Huvudstaden, and Gothenburg and Company. The spatial logics identified as part of contemporary regionalism and region-building processes will be discussed below in relation to The Scandinavian 8 Million City ().

Table 2. Spatial logics in The Scandinavian 8 Million City project.

ECONOMIC AND TERRITORIAL COMPETITIVENESS IN THE SCANDINAVIAN 8 MILLION CITY

The main spatial logic used to support The Scandinavian 8 Million City region-building project was economic and territorial competitiveness. ‘Competitiveness’ as such was frequently used as the main argument to push for the construction of the infrastructure corridor and high-speed railway for the region-building project. As in many other cases, the competitiveness between places was portrayed as being both a future challenge to further economic development and growth for all of Scandinavia and simultaneously, territorial competitiveness was a necessity for developing regional development and economic growth. This double-sided argument was portrayed in The Scandinavian 8 Million City project through the argumentation that without the construction of a high-speed railway, the region would not be competitive enough and the future economic growth of the region was dependent on its construction:

2 capitals – 3 countries – 4 city-regions. Of the approximately 19 million inhabitants in Scandinavia, 8 million live along the Copenhagen–Gothenburg–Oslo line. Modernizing and constructing a new railroad in this megaregion will create a common, integrated labor market with global competitiveness. This will not only lead to increased quality of life and opportunities — the future economic growth of Scandinavia depends on it.

(The Scandinavian 8 Million City, Citation2012)

It is important that we work together from a global perspective. If we do not realize how small we are in a global context and work together to maintain competitiveness, then we will have a hard time asserting ourselves. And the further away you get from Scandinavia, the harder it is for them to keep the Scandinavian countries apart.

(politician, The Scandinavian 8 Million City project)

An increasingly globalized economy increases the demand for efficiency and mobility. Larger and stronger regions are needed to keep and attract people and firms that will build future welfare. There is also a need for fast, efficient and sustainable transport solutions to connect the regions.

(Norway Communicates, Citation2011)

It is difficult to say what would happen if the expansion of the railway were hindered. A negative spiral of course. Accessibility would not be the same and the region would lose attractiveness. Investments and new establishments would decrease. And it would be difficult to keep already established firms and industries.

(official, The Scandinavian 8 Million City project)

So, we must collaborate in certain areas and bind ourselves closer geographically, that is, by infrastructure, to create shorter distances. We will all benefit from that. That is, when you look at our ability to act globally, then we must cooperate. None of us will survive if we also have to fight internally.

(politician, The Scandinavian 8 Million City project)

City regions have become the engines in developing the knowledge and information based community. Their performance and competitiveness rely on knowledge, economy, quality of life, connectivity, urban diversity, urban scale, social capital, politics/framework and image.

(The Scandinavian 8 Million City Guide, Citation2011, p. 8)

IMAGINARIES ON LARGE-SCALE URBAN REGIONS IN THE SCANDINAVIAN 8 MILLION CITY

Even though it can be argued that the overall spatial logic that supported the region-building process in The Scandinavian 8 Million City project was built on territorial competitiveness, this logic was in turn supported by other spatial logics. As shown, the territorial competitiveness logic was closely connected to globalization and economic growth and especially spatial logics on city-regions and megaregions as the most competitive scalar units, such as through the ambition to build an internationally competitive megaregion:

A region consisting of one million inhabitants is unremarkable. In the USA, there is a plan to connect the largest cities via fast connections. In Scandinavia, Copenhagen and Stockholm have the largest populations, soon there will be three million inhabitants in each city-region.

(Reinertsen Sverige, Citation2012, p. 7)

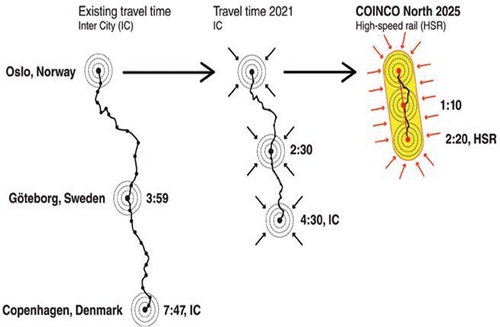

Figure 2. Image over COINCO North – The corridor of innovation and cooperation.

Source: COINCO North, 2012 (www.coinconorth.com).

As such, the imaginary of The Scandinavian 8 Million City project rested on best practices, ideas and successful examples of developing global cities and megaregions from across the world. The borrowing of best practices and successful policy and planning models occurred frequently to demonstrate good examples of megacities and enlarged labour markets. Consequently, consultants and officials working on the project produced reports and other texts by incorporating planning ideals and examples from other parts of the world. In particular, Chinese and other Asian megacities were frequently used as examples of ‘successful’ growing megaregions made possible through efficient high-speed railways. In this way, the imaginary of the Scandinavian city was also built on a mobility discourse that pointed to megaregions as the result of increased mobility patterns within society. In addition, references to successful networked regions such as Silicon Valley, the Green and the Blue Banana in Europe were also made frequently: ‘it is the closest a banana that Sweden, Scandinavia will become compared to the regions on the European continent’ (official, The Scandinavian 8 Million City project). The common denominator among these examples are the ways they connected smaller regions and cities through geographical nodes in a polycentric network. These ideas and references were especially adopted in planning The Scandinavian 8 Million City through the connection to the ESDP and the European TEN-T strategy, especially focusing on polycentrism and the TEN-T vision. The Scandinavian 8 Million City project is a good example of how both national and regional policy and planning structures within the EU have a close relation to the development of the ESDP (Richardson & Jensen, Citation2003). Just as in many other cases, The Scandinavian 8 Million City project also used the TEN-T strategy as a new source of funding for this specific region-building process. This was also visible in the change of forms for collaboration within the project itself that in 2008 went from wider collaborations within tourism, culture and life sciences to the development of the high-speed railway, which would also fit the narratives on EU structural funding, especially the ESDP and the TEN-T strategy. As in this region-building project, many cross-border areas in Europe have served as transnational laboratories in which mega-visions of European space have been tested and applied, leading to new governance structures (Albrechts et al., Citation2003).

The advancement of The Scandinavian 8 Million City project is also in line with the growth and development of new soft spaces in Europe often pushed for by the EU and the ESDP (Purkarthofer, Citation2018). The aim is often to stimulate economic growth and competitiveness in a new functional cross-border region stretching formerly known administrative and national borders:

Capital is flowing freely over national borders and, as a result of the globalization of economic activities, it has become important to create new strategic geographic collaborations and networks. This will lead to new organizational structures and cross-border regions in which city-regions are the new growth engines for society’s knowledge and information.

(The Scandinavian 8 Million City, Citation2012)

This also shows how a variety of theories on successful global cities, such as the theory of the creative class (Florida, Citation2002) have largely influenced policy-makers and planners worldwide, including those involved with The Scandinavian 8 Million City project. International rankings and indices, and Florida’s own nation brand index, have contributed to increasing the circulation of policies on how to be the most ‘attractive’ and ‘competitive’ region, and also influence the ways regional servants, planners, and politicians work.

MANAGERIAL FORMS OF REGIONAL POLICY AND PLANNING IN THE SCANDINAVIAN 8 MILLION CITY

The collaboration between the wide range of actors from public agencies and semi-public entities that promoted the region-building process of The Scandinavian 8 Million City project was an expression of networked forms of governance that challenged traditional planning and policy structures. These networked forms of governance are also representative of the development of growth of cross-border projects and the growth of soft spaces, requiring new constellations of actors and new ways of working (Allmendinger et al., Citation2015). This cross-border project challenged national borders, but also included a wide range of actors lobbying to influence the Nordic governments to accept a memorandum of understanding on a common planning structure and shared funding to build the high-speed infrastructure. Therefore, the creation of a strong regional imaginary around the concept of The Scandinavian 8 Million City became an important part of the region-building process itself. Regional visions, maps and other documents portraying a successful megaregion were important to influence officials and politicians’ support for the project. This shows how official projects have moved towards more managerial forms of governance, in which the use of successful policy models or other successful spatial references are as important as creating one’s own ‘successful’ vision. This construct was also portrayed by the establishment of a communication department working explicitly to market the project to relevant actors. The respondents expressed the importance of having a communication department to ‘sell’ their vision of The Scandinavian 8 Million City project. This was closely related to the project name itself, that is, the name both expresses the future image of the region and was a way of branding it:

When young, successful people want to live in these places, then we know that the places are attractive. There is a top five among such places. At the same time, the brands of the cities also matter. It is geography in practice. … If we look at Silicon Valley, it is a huge geographic area. The name is widely known, but it is also a large geographic area. Skåne is extremely small. It is all about a larger geography. The name becomes the geography.

(regional politician, Region Skåne)

In terms of identity-building, the region-building process of The Scandinavian 8 Million City project did not particularly focus on strengthening regional identities or cultures. Instead, its citizens were portrayed as mobile objects, which is often a common nominator for this kind of transnational corridor. In this kind of narrative, citizens are often represented as ‘elite travellers’ travelling from ‘place to place across previously impractical distances’ (Jensen & Richardson, Citation2007, pp. 137–138). This was also visible in the imaginary of The Scandinavian 8 Million City project where its citizens were to be mobile, flexible and talented as they moved around the globe:

The COINCO Train platform at København H station is where Scandinavians meet: wealthy suits hurrying for business in Copenhagen, healthy sportsmen heading for thrilling adventures up north and tourists travelling south to the European continent. Rugged Norwegians, snooty Swedes and chic Danes: but only a trained eye would recognize these Scandinavian clichés.

(The Scandinavian 8 Million City Guide, Citation2011, p. 24)

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The Scandinavian 8 Million City project was discontinued after 2014 predominantly because the Swedish state decided not to support the development of the planned high-speed railway in the region financially. However, the example of the project is still an interesting example of contemporary region-building processes. It primarily showed how the multiple spatial logics presented here are intertwined and overlapping. However, it also showed how spatial logics for territorial competitiveness became the main spatial logic permeating all other logics in contemporary forms of regionalism especially from the 2000s onward (Bristow, Citation2010; Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2020), although the new regionalism agenda developed already in the 1970s hand in hand with the growth of neoliberalism to enhance economic development and growth the spatial logics for territorial competitiveness have increased. Just as shown by The Scandinavian 8 Million City project, this development is connected with the increasing speed of travelling ideas and ideals on what constitutes the most competitive spaces, enhanced by consultants and business organizations (e.g., Temenos & McCann, Citation2013; Temenos & Ward, Citation2018). Also, spatial reference points, spatial fetishisms and political rhetoric were used to frame problems and persuade policy-makers of the benefits with this particular solution (McCann, Citation2017), that is, the construction of the high-speed railway and thus limited visions of other possible development trajectories. This is also in line with Hidle and Leknes (Citation2014) defining regionalism as ways of using regions as tools for activating certain ends, directing strategies and policies to a specific regional setting. In The Scandinavian 8 Million City project, other spatial logics for megaregions, networked regions and functional regions were used to build an imaginary of the necessity of this particular region-building process, and thus simultaneously contribute to megacities and city-regions as the ideal territorial fix for the further development of capitalism. Also, the European ESDP and the TEN-T strategy played an important part of the spatial logics on imaginaries on large-scale urban regions, also supporting the imaginary of The Scandinavian 8 Million City project. This was especially clear in terms of the financing of the project being part of Interreg IV A, as a way to EU funding and to garner support for the development of this specific region-building process and the construction of the high-speed railway. Even so, the imaginaries of polycentrism and networked regions supported by the TEN-T strategy fits well with the imaginaries on large-scale urban, functional, city-regions as nodes in the global economy, promoting them as larger growth engines of whole nations. This has also contributed to the growth of soft regional spaces, including new governance formations and cross-border collaborations (Hincks et al., Citation2017). As pointed out by Zimmerbauer and Paasi (Citation2020, p. 776), soft spaces, such as The Scandinavian 8 Million City project, which stretch across administrative borders, ‘are regarded as both tools and engines for increasing competitiveness, and eventually for economic success’.

As a result of the strong connections to the spatial logic on economic and territorial competitiveness, this region-building process bore traces of as well new regionalism as Regionalism 2.0, but not as much of an old regionalism aiming to construct the region upon regional differences, such as a strong regional identity. Other region-building projects might still bare traces of an old regionalism already having a strong regional identity or culture, but in this case, the aim of this specific region-building process was purely economic and spatial. Although this specific process did not aim to strengthen a regional identity or culture, however, regional image-building was an important part of the region-building process also including an ideal view of its future citizens as mobile talents. This turn to managerial forms of regional policy and planning as part of contemporary regionalism is also related to the spatial logics for territorial competitiveness since one of the most common ways of measuring an ‘attractive region’ is made in terms of its capacity to attract capital, investments, talents, visitors and new ‘attractive’ inhabitants. Hence, there is an increasing overlap between spatial planning and place-branding practices having effects on both regional and local planning (Lucarelli & Heldt Cassel, Citation2019). As such, these practices enhance spatial fetishism and contributes to the treatment of regions as real actors.

In conclusion, the main spatial logic in contemporary regionalism is the logic for territorial competitiveness, which as shown here is supported by other spatial logics and regional imaginaries regarding the best and most competitive ‘territorial fixes’, especially focusing on large-scale urban areas as drivers of economic growth and development. This also contributes to a possible polarization between centralization and peripheralization processes, especially in the construction of metropolitan regions, privileging urban regions over more ‘peripheral’ ones (Kühn, Citation2015), also leading to increasing regional disparities (Matern et al., Citation2019). As such, the logic for economic and territorial competitiveness must be seen as a prolongation of new regionalism and Regionalism 2.0, but these explanations of regionalism might still be to narrow and to better understand the various forms of today’s regionalization processes and region-building initiatives, their affects must be studied in relation to the specific geographical contexts in which they are embedded.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Business Region Gothenburg is a non-profit company owned by the city of Gothenburg, which also represents the 13 municipalities in the larger Gothenburg region.

2. From 2017 onward, Jernbaneverket transformed into Bane NOR.

REFERENCES

- Albrechts, L., Healey, P., & Kunzmann, K. R. (2003). Strategic spatial planning and regional governance in Europe. Journal of the American Planning Association, 69(2), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360308976301

- Allmendinger, P., & Haughton, G. (2009). Soft spaces, fuzzy boundaries, and metagovernance: The new spatial planning in the Thames Gateway. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 41(3), 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1068/a40208

- Allmendinger, P., & Haughton, G. (2010). Spatial planning, devolution, and new planning spaces. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 28(5), 803–818. https://doi.org/10.1068/c09163

- Allmendinger, P., Haughton, G., Knieling, J, et al. (2015). Soft spaces, planning and emerging practices of territorial governance. In Allmendinger, P., Haughton, G., Knieling J. et al. (Eds.), Soft spaces in Europe (pp. 3–22). Routledge.

- Amin, A. (2002). Spatialities of globalization. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 34(3), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3439

- Amin, A. (2004). Regions unbound: Towards a new politics of place. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 86(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00152.x

- Andrew, J. E. G., & Ward, K. (2007). Introduction to a debate on city-regions: New geographies of governance, democracy and social reproduction. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 31(1), 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2007.00711.x

- Brenner, N. (2004). New state spaces: Urban governance and the rescaling of statehood. Oxford University Press.

- Brenner, N., & Theodore, N. (2002). Cities and the geographies of actually existing neoliberalism? Antipode, 34(3), 349–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00246

- Brenner, N., & Theodore, N. (2005). Neoliberalism and the urban condition. City, 9(1), 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810500092106

- Brenner, N., & Wachsmuth, D. (2012). Territorial competitiveness: Lineages, practices, ideologies. In B. Sanyal, L. J. Vale, & C. D. Rosan (Eds.), Planning ideas that matter: Liveability, territoriality, governance and reflective practice (pp. 179–204). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Bristow, G. (2010). Critical reflections on regional competitiveness: Theory, policy, practice. Routledge.

- Calzada, I. (2015). Benchmarking future city-regions beyond nation-states. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2(1), 351–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2015.1046908

- Davoudi, S. (2003). European briefing: Polycentricity in European spatial planning: From an analytical tool to a normative agenda. European Planning Studies, 11(8), 979–999. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965431032000146169

- Dean, M. (2010). Governmentality, power and rule in modern society. SAGE.

- Deas, I., & Lord, A. (2006). From a new regionalism to an unusual regionalism? The emergence of non-standard regional spaces and lessons for the territorial reorganisation of the state. Urban Studies, 43(10), 1847–1877. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600838143

- Ek, R. (2003). Öresundsregion – bli till! De geografiska visionernas diskursiva rytm. Lunds Universitet – Campus Helsingborg: Institutionen för Service Management.

- European Commission. (1999). ESDP – European spatial development perspective. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Blackwell.

- Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class: And how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. Basic.

- Foucault, M. (2008). Diskursernas kamp. Texter i urval av Thomas Götselius och Ulf Olsson. Brutus Östlings Bokförlag Symposium.

- Friberg, T. (2008). Det uppsplittrade rummet. Regionförstoring i ett genusperspektiv. In F. Andersson, R. Ek, & I. Molina (Eds.), Regionalpolitikens geografi – Regional tillväxt i teori och praktik (pp. 257–258). Studentlitteratur.

- Gregory, D. (1978). Ideology, science and human geography. St. Martin’s.

- Grundel, I. (2013). Kommersialisering av regioner: Om platsmarknadsföring och regionbyggande. In T. Mitander, L. Säll, & A. Öjehag-Petterson (Eds.), Det regionala samhällsbyggandes praktiker: Tiden, Makten, Rummet (pp. 163–182). Daidalos.

- Grundel, I. (2014). Jakten på den attraktiva regionen. En studie om samtida regionaliseringsprocesser. Institutionen för geografi, medier och kommunikation. Karlstads universitet.

- Hall, S. (1997). Representation; cultural representations and signifying practices. SAGE.

- Harrison, J. (2007). From competitive regions to competitive city-regions: A new orthodoxy, but some old mistakes. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(3), 311–332. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm005

- Harrison, J. (2008). The region in political economy. Geography Compass, 2(3), 814–830. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00113.x

- Harrison, J., & Growe, A. (2014). From places to flows? Planning for the new ‘regional world’ in Germany. European Urban and Regional Studies, 21(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776412441191

- Harrison, J., & Hoyler, M. (2015). Megaregions: globalization’s new urban form? Edward Elgar.

- Harvey, D. (1989). From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: The transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 71(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583

- Harvie, C. (2004). The rise of regional Europe. Routledge.

- Healey, P. (2013). Circuits of knowledge and techniques: The transnational flow of planning ideas and practices. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(5), 1510–1526. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12044

- Hidle, K., & Leknes, E. (2014). Policy strategies for new regionalism: Different spatial logics for cultural and business policies in Norwegian city regions. European Planning Studies, 22(1), 126–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.741565

- Hincks, S., Deas, I., & Haughton, G. (2017). Real geographies, real economies and soft spatial imaginaries: Creating a ‘more than Manchester’ region. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 642–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12514

- Hospers, G.-J. (2006). Borders, bridges and branding: The transformation of the Øresund region into an imagined space. European Planning Studies, 14(8), 1015–1033. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310600852340

- Jensen, A., & Richardson, T. (2007). New region, new story: Imagining mobile subjects in transnational space. Space and Polity, 11(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562570701722014

- Jensen, O. B., & Richardson, T. (2004). Making European space. Mobility, power and territorial identity. Routledge.

- Jonas, A. E. G. (2012). City-regionalism: Questions of distribution and politics. Progress in Human Geography, 36(6), 822–829. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511432062

- Keating, M. (1998). The new regionalism in Western Europe: Territorial restructuring and political change. Edward Elgar.

- Keating, M. (2001). Rethinking the region: Culture, institutions and economic development in Catalonia and Galicia. European Urban and Regional Studies, 8(3), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977640100800304

- Kenis, A., & Lievens, M. (2017). Imagining the carbon neutral city: The (post)politics of time and space. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(8), 1762–1778. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16680617

- Kornberger, M., & Carter, C. (2010). Manufacturing competition: How accounting practices shape strategy making in cities. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 23(3), 325–349. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571011034325

- Kühn, M. (2015). Peripheralization: Theoretical concepts explaining socio-spatial inequalities. European Planning Studies, 23(2), 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.862518

- Lucarelli, A., & Heldt Cassel, S. (2019). The dialogical relationship between spatial planning and place branding: Conceptualizing regionalization discourses in Sweden. European Planning Studies, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1701293

- Massey, D. (1991). A global sense of place. Marxism Today, 24–29.

- Matern, A., Binder, J., & Noack, A. (2019). Smart regions: Insights from hybridization and peripheralization research. European Planning Studies, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1703910.

- McCann, E. (2017). Mobilities, politics, and the future: Critical geographies of green urbanism. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49, 1816–1823. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17708876

- Moisio, S., & Paasi, A. (2013). From geopolitical to geoeconomic? The changing political rationalities of state space. Geopolitics, 18(2), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2012.723287

- Neuman, M., & Zonneveld, W. (2018). The resurgence of regional design. European Planning Studies, 26(7), 1297–1311. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1464127

- Norway Communicates. (2011). The Scandinavian mega-region, The Scandinavian 8 Million City. Retrieved from www.norwaycommunicates.com/highspeedrail.html.

- Olesen, K., & Richardson, T. (2012). Strategic planning in transition: Contested rationalities and spatial logics in twenty-first century Danish planning experiments. European Planning Studies, 20(10), 1689–1706. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.713333

- Paasi, A., & Metzger, J. (2017). Foregrounding the region. Regional Studies, 51(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1239818

- Paasi, A., & Zimmerbauer, K. (2016). Penumbral borders and planning paradoxes: Relational thinking and the question of borders in spatial planning. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15594805

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2015). Fast policy. Experimental statecraft at the thresholds of neoliberalism. University of Minnesota Press.

- Pred, A. (1984). Place as historically contingent process: Structuration and the time–geography of becoming places. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 74(2), 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1984.tb01453.x

- Purkarthofer, E. (2018). Diminishing borders and conflating spaces: A storyline to promote soft planning Scales. European Planning Studies, 26(5), 1008–1027. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1430750

- Reinertsen Sverige, A. B. (2012). The Scandinavian 12-million city. Reinertsen Sverige AB i samarbete med underkonsulter SDG och FCF.

- Richardson, T., & Jensen, O. B. (2000). Discourses of mobility and polycentric development: A contested view of European spatial planning. European Planning Studies, 8(4), 503–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/713666421

- Richardson, T., & Jensen, O. B. (2003). Linking discourse and space: Towards a cultural sociology of space in analysing spatial policy discourses. Urban Studies, 40(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980220080131

- Sager, T. (2011). Neo-liberal planning policies: A literature survey 1990–2010. Progress in Planning, 76, 147–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2011.09.001

- Sassen, S. (2002). Global networks, linked cities. Routledge.

- The Scandinavian 8 Million City. (2012). The Scandinavian 8 Million City. Retrieved from www.8millioncity.com

- The Scandinavian 8 Million City. (2013). Hurtige tog får arbejdsmarket til at vokse. Regional udvikling: tilgaenglighed og arbejdsmarked i The Scandinavian 8 Million City. Retrieved from www.8millioncity.com

- The Scandinavian 8 Million City Guide. (2011). The Scandinavian 8 Million City guide – trains, planes & automobiles. Retrieved from www.8millioncity.com

- Storper, M. (1995). The resurgence of regional economies, ten years later: The region as a nexus of untraded interdependencies. European Urban and Regional Studies, 2(3), 191–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977649500200301

- Swyngedouw, E. (2005). Governance innovation and the citizen: The Janus face of governance-beyond-the-state. Urban Studies, 42(11), 1991–2006. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500279869

- Swyngedouw, E. (2009). The antinomies of the postpolitical city: In search of a democratic politics of environmental production. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(3), 601–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00859.x

- Syssner, J. (2002). Culture, identity and the region. Informationen zur Raumentwicklung. Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung.

- Syssner, J. (2006). What kind of regionalism?: Regionalism and region building in Northern European peripheries. Peter Lang.

- Syssner, J. (2008). Regionen och dess medborgare. In F. Andersson, R. Ek, & I. Molina (Eds.), Regionalpolitikens geografi, Regional tillväxt i teori och praktik (pp. 37–56). Studentlitteratur.

- Syssner, J. (2009). Conceptualizations of culture and identity in regional policy. Regional and Federal Studies, 19(3), 437–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560902957518

- Syssner, J. (2011). No space for citizens? Conceptualizations of citizenship in a functional region. Citizenship Studies, 15(1), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2010.534934

- Temenos, C., & McCann, E. (2013). Geographies of policy mobilities. Geography Compass, 7(5), 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12063

- Temenos, C., & Ward, K. (2018). Examining global urban policy mobilities. In J. Harrison, & M. Hoyler (Eds.), Doing global urban research (pp. 66–80). SAGE.

- Törnqvist, G. (1998). Renässans för regioner: om tekniken och den sociala kommunikationens villkor. SNS (Studieförb. Näringsliv och samhälle).

- van Straalen, F. M., & Witte, P. A. (2018). Entangled in scales: Multilevel governance challenges for regional planning strategies. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 5(1), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2018.1455533

- Wachsmuth, D. (2017). Competitive multi-city regionalism: Growth politics beyond the growth machine. Regional Studies, 51(4), 643–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1223840

- Wetzstein, S., & Le Heron, R. (2010). Regional economic policy ‘in-the-making’: Imaginaries, political projects and institutions for Auckland’s economic transformation. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(8), 1902–1924. https://doi.org/10.1068/a42248

- Zimmerbauer, K. (2011). From image to identity: Building regions by place promotion. European Planning Studies, 19(2), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2011.532667

- Zimmerbauer, K., & Paasi, A. (2020). Hard work with soft spaces (and vice versa): Problematizing the transforming planning spaces. European Planning Studies, 28(4), 771–789. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1653827