ABSTRACT

The literature integrating an agency perspective with evolutionary economic geography (EEG) has tended to focus on change agency. This paper introduces a distinction between change agency and reproductive agency. The variegated agency understanding is integrated within a path-as-process perspective. By investigating three cases of rural tourism development, changes in types of agency in the course of path evolution are elucidated. It emerges that both change and reproductive agency are important for industry path development. Thus, the article contributes to a more dynamic and nuanced understanding of the role of agency in path evolution, expanding the hitherto change-oriented agency literature in EEG.

JEL:

INTRODUCTION

In recent years the evolutionary economic geography (EEG) field has started to address its structure centrism by granting increased attention to agency (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020; Isaksen et al., Citation2019; Kyllingstad & Rypestøl, Citation2019; Steen, Citation2016). In this endeavour the focus has been on agency in path creation and diversification (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020; Isaksen et al., Citation2019; MacKinnon et al., Citation2019b; Sotarauta et al., Citation2020). Accordingly, radical change agency has moved centre stage. However, Jolly et al. (Citation2020) highlight the strong presence of reproductive agency in some phases of path evolution. Yet, reproductive agency remains under-conceptualized relative to change agency. It is often understood as a source of lock-in or obstruction of innovation, while other roles it might play in industry development have scarcely been investigated. This paper introduces a more nuanced understanding of reproductive agency, thus proposing a framework for investigating the variations in agency across path evolution.

To examine the different combinations of agency throughout industry path evolution, tourism development in the villages Flåm, Odda and Sogndal in Western Norway has been investigated. The villages are by the Sognefjord and the Hardangerfjord, areas with a long history of tourism. The three villages are receiving a disproportionately large share of the visitors in the region and have developed industry paths in distinct types of tourism. As a consequence of its networked nature, as well as the indirect impact of visitors on everyone living in a tourism destination (Milano et al., Citation2019), the tourism sector tends to involve a large number of variegated actors. Therefore, the sector lends itself to a qualitative examination of the varying types of agency in industry development. The following research question is addressed: How do change and reproductive agency vary in the course of path evolution? By addressing this question, the article contributes to nuancing the change-oriented understanding of agency in EEG.

As the tourism geography literature engages both with evolutionary theory and cases of strong agency (e.g., Randelli et al., Citation2014), it would appear as a fruitful strand of literature to draw upon in order to advance the agency perspective in EEG – especially so when using tourism development cases. However, evolutionary perspectives on tourism have mostly brough insights from EEG to tourism geography, rather than being framed as contributions to EEG or economic geography as a whole (Brouder, Citation2017; Dieter, Citation2019, p. 67). To my knowledge, there is no work within the field conceptualizing agency in relation to evolutionary theory. This might reflect a certain tendency towards descriptivism in tourism geographies (de Cássia Ariza da Cruz, Citation2019). Therefore, the understanding of agency in this paper builds upon empirics and existing conceptualizations from EEG and related literatures.

EVOLUTIONARY ECONOMIC GEOGRAPHY AND AGENCY

In spite of path dependence theory in its original form first and foremost explaining why it is sometimes difficult for businesses or industries to break out of certain tracks (David, Citation1988), discussions on the role of agency within EEG also spring out of the path dependency literature. The path dependence perspective’s structure centrism was first challenged by Garud and Karnøe’s (Citation2003) concept of path creation. In their notion of path creation, a new industry path is created through a multi-agentic process. Another question introducing change agency to path-dependent processes was that of breaking out of lock-in (Sydow et al., Citation2009). Both new path creation and breaking out of lock-in have become central topics in EEG (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020; Hassink, Citation2010).

Martin (Citation2010) reformulated the path dependence model as processual, to a larger extent allowing for change as well as continuity, and thus for a more significant role for agency in the course of path evolution. While increasing returns, network externalities and positive feedback cycles are key to the development of a distinct path, they do not necessarily lead to suboptimal lock-in (Martin, Citation2010). Also in established paths, agency may produce dynamism, making path extension, upgrading, diversification or creation possible (Grillitsch et al., Citation2018).

This study joins the economic geography tradition, defining an industry path as a distinct type of activity of economic relevance to the territory, which gathers sufficient critical mass to produce self-reinforcing effects (Fredin et al., Citation2019, p. 797). Although new industry paths are distinct from other activities in the region, they are often created from latent potential in pre-existing activities (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019b; Martin & Sunley, Citation2006; Njøs et al., Citation2020). Thus, new industry creation implies both continuity and change. The latter is often attributed to agency, which in EEG is commonly understood as ‘action or intervention by an actor to produce a particular effect’ (Sotarauta & Suvinen, Citation2018, p. 90).

While the common definition of agency in EEG focuses on the single actor, it is also argued that change is usually not made by single heroic actors, but rather emerges from the actions of multiple actors with different visions and interests (Sotarauta et al., Citation2017). Even in the case of one or a few agents working for a specific change, these depend on others for changing practices (Weik, Citation2011, p. 473) and getting access to resources. Thus, an actor’s social network is an integral part of the actor’s agency (Battilana, Citation2006).

Change is not only made by multiple actors, but through a combination of different forms of agency. Isaksen et al. (Citation2019) suggest that more radical change requires both system- and firm-level agency, while Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) distinguish between Schumpeterian entrepreneurship, institutional entrepreneurship and place-based leadership, arguing that these three types of change agency are essential for regional path development.

In line with Schumpeter’s (Citation1934) notions of entrepreneurship and creative destruction, Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020, p. 7) define Schumpeterian entrepreneurship as entrepreneurs ‘breaking with existing paths and working towards the establishment of new ones’. They emphasize that although innovative entrepreneurship is central, new path development requires wider changes in institutions. Institutional entrepreneurship is key in making such changes. Following Battilana et al. (Citation2009, p. 68), institutional entrepreneurship is understood as actions leveraging resources to create new or transform existing institutions. As path development requires a mix of actions from several actors, mobilization and cooperation between different actors and interests is also central. Place-based leadership plays this mobilizing role (Sotarauta, Citation2016). In the trinity of change agency, place-based leadership is defined as conscious efforts to mobilize actors and coordinate their actions ‘to stimulate the emergence of a regional growth path … ’ (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020, p. 9). While for example a mayor might be a place-based leader, place-based leadership is independent of formal position, and is often relatively hidden. It works through networks and can be distributed among several people (Sotarauta, Citation2016). As the three categories refer to agency, rather than actors, it is also useful to keep in mind that the one and same actor might enact different forms of agency simultaneously or across time, and that the type of agency enacted does not necessarily coincide with the formal role of an actor.

Reproductive agency

While attention towards change agency ameliorates the structure centrism of EEG, this perspective has to a lesser extent been able to take agency’s contribution to path dependence into account (Sunley, Citation2008; Sydow et al., Citation2009). People’s actions can also not produce change, or produce less radical change. Accordingly, it is useful to distinguish between change agency and reproductive agency (Coe & Jordhus-Lier, Citation2011). Reproductive agency can be resistance to novel activities (Jolly et al., Citation2020), but it also involves actions existing in their own right (rather than in opposition to something) and which imply some degree of change, but still hold a small change potential relative to change agency (Kurikka & Grillitsch, Citation2020). Agency as a stabilizing factor is as many-faceted as change agency and should not be reduced to pure obstruction or equated with non-agency. The literature has not yet developed a conceptual apparatus that captures the nuances in reproductive agency. The aim of this paper is to address this issue, building a novel framework by giving Grillitsch and Sotarauta’s (Citation2020) three change-agency types counter categories. The change agency and reproductive agency categories represent two ends of a range, thus giving a more nuanced agency understanding.

While Schumpeterian entrepreneurship refers to the creation of activities that are at least new to the place, the many cases where new firms are created, but where these are similar to existing businesses, will be referred to as replicative entrepreneurship (Baumol, Citation2010, p. 18). Most entrepreneurship is closer to replicative than to Schumpeterian entrepreneurship. Replicative entrepreneurship is also agency, and it involves change for the individual or the firm. Yet, seen in a wider perspective, replicative entrepreneurship is characterized by gradual improvement rather than radical innovation and change. Thus, it is here considered a type of reproductive agency.

Institutional work will be used as a counter category to institutional entrepreneurship. While institutional entrepreneurship is change oriented (Battilana et al., Citation2009), the notion of institutional work has a broader range. It includes efforts that contribute to maintaining existing institutions and institutional practices that are often taken for granted (Lawrence et al., Citation2011). In this paper, institutional work will be used when referring to institutional practices that, unlike institutional entrepreneurship, are not intended to produce radical change.

Place-based leadership is most often associated with change (Benneworth et al., Citation2017; Coenen et al., Citation2020; Jolly et al., Citation2020; Sotarauta et al., Citation2017). However, one may ask whether ‘shared leadership where many different independent actors exercise mutual influence to agree and deliver collective goals’ (Benneworth et al., Citation2017, p. 236) will always be change oriented. Similar networks and collaboration practices may also contribute to strengthening existing activities. Aiming to account for mobilization and collaboration both for change and for maintaining established paths, the contrasting categories change leadership and maintenance leadership are derived from the notion of place-based leadership. Thus, we have a continuum with Schumpeterian entrepreneurship, institutional entrepreneurship and change leadership on the change agency side, and replicative entrepreneurship, institutional work and maintenance leadership on the replicative agency side.

In order to avoid implicit local bias in the theorizing on agency, a distinction between local and non-local actors is added to the perspective. While networks for place development tend to have a strong territorial dimension (Martin & Sunley, Citation2006), extra-regional linkages, giving access to non-local assets, are also key for path creation and development (Binz et al., Citation2016; MacKinnon et al., Citation2019a). Extra-regional linkages are made by relations between local and non-local actors, where the latter have agency too (Binz et al., Citation2016). Non-local actors may enact the same types of agency as local actors. However, they might steer the path in directions not wished for by local actors because they are often characterized by ‘placeless power’, meaning they exercise cumulated power without caring about ‘the consequences of their decisions for particular places and communities’ (Hambleton, Citation2019, p. 3). Yet, non-local actors may also act for the good of particular places, either as a result of coinciding interests or of their mandate and responsibilities (Fløysand et al., Citation2017).

Change agency and reproductive agency in the course of path evolution

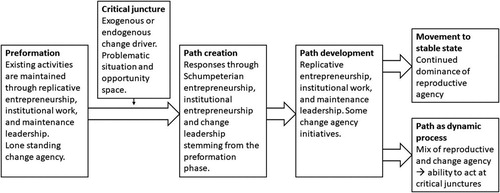

In the following section expectations for different dynamics between the various types of change and reproductive agency and the passages between them in the course of industry path evolution are discussed. The discussion is structured according to Martin’s (Citation2010) path-as-process model, with an emphasis on preformation, path creation and path development. Thus, the section presents an analytical framework (summarized in ) which combines the evolutionary dimension with a variegated agency understanding, treating agency as a factor contributing both to continuity and change.

Figure 1. Types of agency in the course of the path process.Source: Adapted from Martin (Citation2010, p. 21).

The preformation phase

By studying the preformation phase, we may understand the conditions from which a path starts (Martin, Citation2010). In this phase reproductive agency prevails. Habits are slowly evolving as agents reflexively adapt existing patterns to constantly changing situations (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998, p. 968). Through their daily activities, actors are embedded in social networks. While the institutional work enacted in these networks might constrain actors from working for change, such network embedding may also constitute a large part of actors’ agency and give leverage in effecting change. Thus, not only constraints but also capabilities and space for action is built up before the events of immediate relevance to path creation (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020, p. 11).

Although reproductive agency prevails, agentic behaviour in the preformation phase can open new opportunities (Smith et al., Citation2017). Reproductive agency might contribute to maintaining an already favourable environment for industry development, or Schumpeterian entrepreneurship in an otherwise stagnant environment might be the first step towards a new path, inspiring further change agency. For example, the demonstration effect from pioneers of offshore wind made it a focus for the industry development programme in North East England (Dawley et al., Citation2015). New ideas, or emerging challenges to old paths, may first be discussed in pre-existing networks of place-based leadership. Further, the experience of one’s effort making a difference can encourage actors to get involved with or lead change processes in the future, as well as provide knowledge of how to do so (Steen, Citation2016). Thus, different actions and processes in the preformation phase may gather momentum for a subsequent period characterized by change agency and path change.

From preformation to path creation

The shift from the reproductive agency patterns of the preformation phase to a change agency pattern in the path creation phase may be explained both by the agency itself (Sydow et al., Citation2009, p. 5) and by the influence of events and conditions beyond the control of agents (David, Citation1988). Changes in the context may create new opportunities or problems to which actors respond (Araujo & Harrison, Citation2002). These produce critical junctures – ‘relatively short periods of time during which there is a substantially heightened probability that agents’ choices will affect the outcome of interest’ (Capoccia & Kelemen, Citation2007, p. 348). Critical junctures imply the presence of an opportunity space, but also of events that necessitate agency. The notion of ‘problematic situation’ (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998), inspired by Mead’s (Citation1932) theorization of temporality, gives a perspective on the relationship between such contextual events and agency. A problematic situation makes it hard to reproduce existing patterns, thus pushing agents out of routine and allowing for ‘reflective distance to received patterns’ (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998, p. 972). The pressure experienced by actors in the problematic situation makes their actions more conscious or intentional than what is the case in the daily course of things.

Agency in the face of problematic situations means reading the situation not only in terms of interpreting the problem, but also seeing opportunities (Smith et al., Citation2017), drawing on network connections that ‘were there all along’ or creating new ones (Garud et al., Citation2010). This is possible also in the absence of a problematic situation. An agent that spots and starts working towards a new opportunity may induce a critical juncture on the context as their actions open a window of opportunity that others may or may not utilize (Kurikka & Grillitsch, Citation2020). Such agency can be conducted by both firm- and non-firm actors (Binz et al., Citation2016; Isaksen et al., Citation2019).

In particular, the development of a new path requires Schumpeterian entrepreneurship. Yet, the actions that lead to industry development tend to involve changes beyond the single firm (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020; Isaksen et al., Citation2019). There is a dynamic between different types of change agency. For instance, the initiating Schumpeterian entrepreneurship might build on institutional changes or initiatives launched through place-based leadership in the preformation phase, materializing an imagined future shared by several actors. Furthermore, theory indicates that institutional entrepreneurship makes divergent change possible by removing crippling limitations or making necessary resources available (Boschma et al., Citation2017). Thus, a combination of different change-oriented actions affecting different areas are necessary for path creation (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020, p. 11). New non-local actors are also likely to get involved in this phase, for example through Schumpeterian entrepreneurship, or by doing institutional work beyond the local level.

From path creation to path development

While the shift of prevailing types of agency between the preformation and path creation phase is marked by a critical juncture, the transition from the change agency dynamics of the path creation phase to the reproductive agency pattern of the development phase is typically gradual. As the path emerges, those that enacted change agency in the creation phase will have vested interests and might not want to drastically change the emerging path (Musiolik et al., Citation2012). Rather, they might cultivate self-reinforcing dynamics (Fredin et al., Citation2019; Sydow et al., Citation2010). Institutional changes introduced during path creation will also shape and constrain the space for agency (Hassink, Citation2010). For instance, the support structure that might have been developed along with the path also tends to foster path reproduction (Isaksen et al., Citation2019). Simultaneously, new opportunities emerge as the new path develops. Consequently, more actors are likely to further strengthen the self-reinforcing dynamics of the path through replicative entrepreneurship (Elert et al., Citation2019).

Although path development is marked by reproductive agency dynamics, this does not imply a total absence of change agency. As an industry path moves from burgeoning industry to growing industry, initial problems and tensions from conflicts of interest are likely to emerge (Miörner & Trippl, Citation2019). This is further complicated in the case of unequal power relations, especially between local and non-local actors (Hambleton, Citation2019). Institutional entrepreneurship might reduce conflicts, curb development-related problems and give direction, thus contributing to the self-reinforcing dynamics and further development of the path. Place-based leadership, both for change or maintenance, may also play an important role in fostering collaboration and common direction, and entrepreneurs might find solutions to new problems or opportunities stemming from the ongoing development. On the one hand, then, reproductive agency plays the major part in path development and can for instance contribute to diversification of established paths, but on the other hand, some change agency is necessary for the path to continue developing. A situation with too much reproductive agency will likely lead to lock-in and eventually stasis (Martin, Citation2010), with a high risk of the path disappearing in the face of changing conditions (Isaksen, Citation2018). A path with a better mix of reproductive and change agency may remain dynamic, with a higher ability to respond to problematic situations and use critical junctures to renew the path.

METHODS

In this investigation, three cases are examined. Consistent with the evolutionary framework that the study aims to inform, the cases are approached through process tracing (George & Bennett, Citation2005) or, in the language of EEG, tracing the path (Pike et al., Citation2016, p. 131). Locality is the point of departure for tracing the tourism development paths backwards from the current situation to their initial events and conditions. In order to understand the role of different events, conditions and actions in the path evolution process, two types of data have been analysed: interviews and secondary sources. Both types of sources have been consulted in two rounds, first for background information and later for reconstructing the course of events in each of the case locations.

Observation at industry meeting points, analysis of secondary sources such as newspaper articles, policy documents and reports, as well as eight interviews with background informants, comprise the background materials. National and regional tourism strategy documents (e.g., Hordaland Fylkeskommune, Citation2009; Johnsen et al., Citation2009; Vestlandsrådet, Citation2014) and reports on the economics of the sector (e.g., Iversen et al., Citation2014) made up the major share of secondary sources as background material. The background informants, who work in the public support structure or sector organizations for the wider region, were interviewed between November 2018 and January 2019, giving a general overview of the development in different locations.

In order to trace the evolutionary processes in each of the case locations, in the course of 2019 semi-structured interviews were conducted with six actors in Flåm, six in Sogndal and five in Odda. Three follow-up interviews were conducted in August 2020. Including nine background interviews, the interview material consists of 29 interviews. The actors either have long-standing experience from the local tourism sector or from local economic and social life more broadly. Some of them were referred to as key agents by several others. The interview guides were informed by the theoretical framework and by prior analysis of the background materials. Possible biases, as well as hindsight rationalization and the weaknesses of human memory, are important disadvantages of using interviews when studying past events. However, comparing information from different interviews as well as from newspaper articles, and in the case of Odda, archive materials, partly ameliorates these weaknesses. Reconstructing the paths from the increasing amounts of data, questions were adapted and the search for secondary data directed towards blank spaces and points of contradiction in the collected material. For instance, archive material relating to past tourism and restructuring strategies both filled in gaps and (dis)confirmed claims from interviewees in Odda, while statistics on the number of applicants to the university college confirmed claims from interviewees in Sogndal. Thus, the combination of different sources, and the particular attention towards contradictions in the material, contribute to the validity of the study.

CASES

The three cases are all located in Western Norway, two of them by the Sognefjord and one by the Hardangerfjord (). Being in the same region, the cases have similar formal institutions and political and economic conditions. They also share landscape characteristics, as the villages are all located at the end of a fjord branch. Although they have several commonalities, the three cases have seen the evolution of very different tourism sectors. Thus, the design follows the logic of ‘most similar cases, different outcome’ (George & Bennett, Citation2005).

Sogndal village has about 4000 inhabitants and is the centre of a rural region with an even larger population. Sogndal has three hotels and several other providers of accommodation, and in 2018 almost 17,000 tourists stopped there overnight (statistikknett.no, Citation2019). While many tourists simply stop for one night, since 2008 the village has made a name for itself within backcountry skiing and climbing. Sogndal’s mountain sport tourism is a niche with synergies to important sectors in Sogndal, especially higher education, and thus plays a different role from pure accommodation.

Odda has 7000 inhabitants, and approximately 100,000 visitors per year. Most visitors come to hike to a rock formation called Trolltunga, located 10 km into the mountains. This hiking tourism has seen fast growth since the late 2000s and works as a diversification from metallurgic industries in what has been a ‘single industry town’.

Flåm is the smallest village and has the largest number of visitors, with approximately 400 inhabitants and 1 million annual visitors. Tourism is the main economic activity, and a mass tourism strategy has been developed based on a historic railway.

Sogndal

The establishment of a teachers’ school in 1972 and a rural university college in 1975 has been decisive in giving Sogndal unprecedented growth for a village by the Sognefjord. The formation of these educational institutions was a result of a decision made by the state, which has since been an important non-local actor in Sogndal. In the changing political climate of the 1980s the university college took a more business-oriented direction, offering courses in business administration and tourism management (Yttri, Citation2008). This was both a first step towards the synergies that later developed between higher education and tourism and an early example of local agency adapting to that of the state.

A new era of local collaboration and maintenance leadership was sparked when new Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) stadium requirements were introduced, creating a need for a new stadium in Sogndal (Fløysand & Jakobsen, Citation2007). The stadium was built on the campus plot. Long-term rental contracts for teaching space for the university college allowed for use of state resources for local scopes beyond those intended by the state. Thus, Fosshaugane Campus, the major achievement of what some informants call the ‘Sogndal model’, became a prime example of what can be achieved through persistent collaboration. ‘And that’s one of Sogndal’s characteristics: widespread volunteerism and collaboration’ (local entrepreneur).

The same networks of collaboration that made Fosshaugane Campus possible exercised more change-oriented place-based leadership when a mountain sport festival was organized in 2008. By connecting local resources such as mountaineering guides, glacial researchers, spectacular mountains and good snow conditions at the right time, the festival entrepreneur enhanced the opportunity for Sogndal to tap into the growing trend of backcountry skiing and other mountain sports. Perhaps due to the organizer’s journalistic experience, the festival received media coverage that established the reputation of the snow in the Sogndal valley as among the best in the world. This is a form of institutional entrepreneurship that opened opportunities for entrepreneurship. A contributing factor was also that the regional office of the national television had been looking for a winter sport event to cover. Later, the same journalists launched a reality series called Fjellfolk (mountain people), featuring several people from the Sogndal area who work in or spend a lot of time in the mountains. The work behind the series was both replicative entrepreneurship, as they produced and sold a new television series, and a form institutional work that reinforced the image of Sogndal as a mountaineering and backcountry skiing location.

A ball started rolling with the winter sport festival. They have opened the door for many like us. … The mountains were here, then the equipment came, interest grew, and then came the mountain sport festival, then came Fjellfolk and then came we.

(local tourism entrepreneur)

The niche tourism activities have become a positive force for other activities in Sogndal. In the years following the first festival, applicant numbers to the university college in Sogndal grew more than the national average. ‘I don’t think it’s coincidental that the Mountain Sport Festival started in 2008 and that we then saw an upturn in several of our education programmes’ (board member at the university college). In 2017 the university college started offering a bachelor’s programme in nature-based tourism, thus using and reinforcing Sogndal’s new image as a place for mountain sports. In the years following the first winter sport festival, several new outdoor tourism companies have been established in Sogndal, but the companies are all small and of a lifestyle entrepreneurship character. Commercial developments of the ski lifts and second-home properties in its surroundings might be the closest Sogndal comes towards Schumpeterian entrepreneurship within outdoor sports. This involves some central actors from the first years of the festival, as well as non-local investors.

Further development of the mountain tourism path in Sogndal would require more entrepreneurship with a higher degree of novelty, or at least at a larger scale. The slow commercial development may partially be explained by the nature of the local mountaineering sector, where mountaineering guides in particular prioritize protecting the mountains above capitalizing on them. It can also be tied to the priorities emerging from maintenance leadership, seeing mountain sports first and foremost as contributing to community and to making Sogndal attractive for other sectors, rather than as an important economic opportunity in its own right. However, the equilibrium around place-based leadership might be shifting. Some are now debating what is being perceived as unjust concentrations of power through non-formal channels. This may change the dynamism of the mountain sport tourism path.

Odda

Once Norway’s top tourist destination, Odda was transformed to an industrial town in the middle of an otherwise picturesque region after the establishment of the first smelting plant in 1908. Since the 1990s, Odda experienced industrial decline. For a town where three industrial companies employed one-third of the population, the situation was critical (Odda Municipality, Citation2000). From 1997 to 2002, Odda Municipality ran a restructuring project with higher tech industrial spin-offs and tourism development as parallel strategies. In 2003, Odda Smelteverk, the major employer in Odda, finally closed. This loss of 200 jobs represented a critical juncture for Odda. ‘Many lost their jobs, and we suddenly had 160 declares in the town centre that we did not know what to do about. Maybe we to a bigger extent saw that we had to change … ’ (municipal employee).

In response, some wanted the old production facilities removed to free up space for new activities, while others wanted to preserve them as United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) world heritage and use them for cultural tourism (Cruickshank et al., Citation2013). The latter group was inspired by past conservation projects, which, among other things, had led to the establishment of an industrial history museum in Tyssedal, 6 km from Odda. The conflict between the industry-oriented maintenance leadership and the tourism-oriented attempts at change leadership constrained effective response. After years of debate, the smelting premises are still there, mostly unchanged.

The development that led to the current tourism growth was independent of Odda’s major industrial assets and is not a direct result of the past municipal efforts for tourism development. In 2008, facing an economically problematic situation, one of the local co-owners of a new hotel in Odda tried to create new attractions. He picked a rock formation called Trolltunga and a route for a via ferrata.Footnote1 The via ferrata was projected together with the industrial history museum, following the water pipes of the old hydroelectric power station, valorizing this part of the industrial heritage. ‘We collaborated with the museum from day one. They have been a very nice collaborator, both as co-advocate and as thought partner for the historical contents in our trips’ (mountain guide entrepreneur).

In this collaboration Schumpeterian entrepreneurship was coupled with the change leadership behind the industrial history museum. Yet, local collaboration did not change the situation alone. In 2008, the same year as the hotel was on the verge of bankruptcy, the destination marketing organization (DMO) of the Hardanger region made a new marketing strategy, using images of the Trolltunga rock formation on all their materials and communications. ‘We wanted something that drew attention, really. And then we found Trolltunga. … And at the same time [entrepreneur] established [mountain guide company]. It happened contemporarily. And we have kept in touch throughout the years’ (Hardanger DMO).

After discovering each other, the DMO and the Trolltunga mountain guide entrepreneur contacted the supra-regional DMO, which became an important non-local agent for tourism development in Odda. Through the networks of the national tourism marketing organization, the images of Trolltunga gained a massive reach, being displayed in Times Square and on the front page of National Geographic Traveller. As visitors came, had their photograph taken on Trolltunga, and shared the images on social media, the marketing had a self-reinforcing effect. As a result, the number of visitors grew from 1000 in 2009 to 50,000 in 2015 (Hardanger, Citation2015).

Rapid growth gave the Odda community a much needed boost, with an estimated increase in value creation from tourism from approximately €1.3 million in 2012 to €7 million in 2017 (Wigestrand, Citation2018, pp. 28–33). However, quick growth also caused ‘growth pains’. In 2016, there were 40 cases of mountain rescue emergencies. The DMO invited all relevant actors to participate in finding solutions, which involved changes in information and marketing, improvements to physical infrastructure, as well as having safety staff along the trail. In this phase, heterogeneous actors were aligned through maintenance leadership from the DMO. The municipality took a central role in carrying out these changes. Some of the common solutions were institutional changes, introduced to avoid self-undermining effects from tourism growth, thus illustrating how change agency might also have a path-reproducing effect.

Then we no longer wanted attention at any cost and agreed that all photos, TV and video produced at Trolltunga had to fit within the behaviour we want people to have there.

(Hardanger DMO)

So that’s how we work, to make tourism as little of a hassle as possible to the locals. For instance, we have moved a part of the trail to steer away from a popular cabin area on the way to Trolltunga.

(municipal employee)

Since the Trolltunga breakthrough, some new activities have emerged through replicative entrepreneurship. Several non-local actors have expressed interest in Odda and Trolltunga. In dialogue between the mountain guide entrepreneur and the municipality, some projects were deemed unsuitable while others have been welcomed but have yet to materialize. By 2019 visitor numbers stabilized, and one might ask whether local actors will be able to further develop the path that has been created. Until now, commercial entrepreneurship of significance, except for the hotel and mountain guide entrepreneur, is missing. However, the municipality is conducting a public inquiry for a big sky-lift project by a non-local investor group. Although the new tourism path lacked foundations in local norms and imaginations, continued work for tourism development by the municipality and others might indicate a change away from purely industry-focused maintenance leadership.

Flåm

A railroad line, constructed for infrastructural purposes in 1941, is the foundation for today’s large-scale tourism development in Flåm. However, the development does not start with the construction of the line, but rather with the risk of its abandonment. In the 1980s, several railway side tracks around Norway were closed. After warnings from the new county governor, who had previously worked for the national railways (NSB), Aurland municipality initiated a train-based tourism development project in 1994. The change leadership surrounding the project pointed out train-based tourism as a future trajectory for Flåm. The project augmented the perceived importance of the railway, now going beyond its infrastructural function and the jobs at the railways.

In 1997, in spite of having been involved in the tourism project, the NSB decided to terminate the operations of the Flåm railway. In this problematic situation, the mayor, who found himself in a position of particular responsibility, enacted strong change agency. Together with the municipal tourism secretary, he presented the NSB with a tourism-based business model for turning the small deficit into significant profit. The NSB joined the project on the condition that the municipality would buy the railway infrastructures and build a cruise terminal in Flåm. While most municipalities would not have been able to do so, this was a possibility because Aurland municipality had a significant income from hydroelectric energy production. By setting conditions, the NSB as a non-local actor significantly shaped the path taken by Flåm, opening the door for other powerful non-local actors. A highly unusual organizational constellation was formed as the municipality and the local bank together bought the railway and the hotel, while the NSB were paid for operating the trains. In making this deal, the same parties were involved in institutional as well as Schumpeterian entrepreneurship. While the mayor and the local bank were acting for the good of the village, they created a profit-seeking actor that subsequently came to shape the trajectory of Flåm. However, they were careful to make this a publicly owned ‘capitalist’, later rejecting an interested private investor due to disagreements about the further development of Flåm as a destination, thus combining maintenance leadership and replicative entrepreneurship.

There was an investor group that expressed interest. … In principle, it was wrong to privatise the whole area. They wanted to put up a fence towards the local community rather than involving them in the development. … And the happy outcome was that we parked the investor group and got SivaFootnote2 with us.

(former mayor)

Non-local actors have been pushing for growth without concern for the cumulated local effects. Flåm AS and some other local actors have cultivated the growth, trying to maximize local value creation and limit negative side effects. For this purpose, Flåm AS has encouraged and supported local entrepreneurship, while also buying some local companies in order to develop them for tourism purposes. In this way, Flåm AS is exercising both entrepreneurship and maintenance leadership, and fulfilling some of the functions of a destination marketing and management organization. Taking on these wider roles, the company has also enacted institutional entrepreneurship. This form of institutional entrepreneurship contributes to the self-reinforcing dynamics of continued new venture formation within tourism in Flåm. ‘That has been one of the strengths here, that everyone knows everyone. You can give input, join and get traction from the big actors. That new things are started and we get new experiences, that’s a win–win situation’ (local entrepreneur).

In response to tensions regarding crowding and pollution from cruise traffic, in 2015 and 2016 the organization managing the Nærøyfjord world heritage park attempted to reduce the gap between industry and inhabitants through dialogue conferences. This maintenance leadership has contributed to solving problems related to crowding and travellers trespassing on farmland. However, the pollution issues remain. Through the UNESCO status gained by the Nærøyfjord in 2005, the state too entered as a non-local actor, representing a counter-power to the tourism industry forces. In May 2018, Parliament decided that all traffic in the world heritage fjords must be zero emission by 2026.

When it comes to starting to set requirements, the UNESCO-status has been a weight in that direction. … I’d say that thus far we have managed to balance different considerations, so the tourism industry machine has not run out of control. … What happens now when it comes to emissions is surprisingly positive, and it goes faster than I had expected. And what makes me feel a bit optimistic is that the [local] industry itself, at least when they talk to me, are no longer screaming for more, more, more.

(former mayor)

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

As illustrated by the empirical analysis, the prevailing types of agency vary between the path creation phase, which is characterized by change, and the phases where more stability is needed for the path to develop. Seen in retrospect, the paths build on developments and actions that took place in the preformation phase. This historical continuity indicates that even radical change agency has an evolutionary element to it, as it may build on pre-established networks or materialize future visions that emerged over time.

The shift from the reproductive processes of the preformation phase to the change dynamics of path creation can often be traced to a critical juncture, which in two of the discussed cases were triggered by problematic situations. A critical juncture is not made only of problems, but also by an opportunity space that makes certain changes possible. Both the problematic situations and opportunity space at least partially stem from exogenous processes to which agents respond. While non-local actors play an important role in making change possible, in the three cases agency by local actors was key in initiating path creation. This makes sense in light of the agency-triggering effect of problematic situations, which are problematic for specific places or for certain people (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998). Thus, the shift from reproductive to change agency is produced by a mix of exogenous forces and agency by locally embedded actors.

The path creation phase is characterized by the intertwining of Schumpeterian entrepreneurship with change agency beyond the firm. Change agency may be concentrated in a few agents and does not necessarily correspond to their formal position. For instance, institutional entrepreneurship and place-based change leadership may be enacted by firm actors (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). Perhaps more surprisingly, the case of Flåm shows that public actors too may enact Schumpeterian entrepreneurship. The cases of Flåm and Sogndal also show that the one and same actor may be involved with several types of change agency in a concentrated period of time. Further, in the path creation phase local actors typically involve non-local actors who contribute resources that are not available locally. These actors may continue influencing subsequent path evolution (Binz et al., Citation2016).

The shift from change agency dynamics to the reproductive agency patterns of path development is gradual. Due to vested interests, agents actively reproduce and strengthen the path (Musiolik et al., Citation2012). Thus, the same actors who enacted change agency in one situation may enact reproductive agency in another. Compared with the path creation phase, where a few actors tend to enact several types of change agency, agency is more distributed in the path development phase. As the emerging path opens new opportunities, replicative entrepreneurship and complementary activities add critical mass. Place-based leadership is likely to focus on maintenance, as with the dialogue conferences in Flåm. Such reproductive agency may indeed be a positive force for development, without which a path is unlikely to stabilize. Yet, there may be a mix between reproductive and change agency also in the path development phase. For instance, new collaborations and the creation of new institutions in Odda are changes. However, these changes also contribute to the development of the path, as they counter self-undermining effects stemming from the path itself. This illustrates that there is a continuum between change agency and reproductive agency. Such nuance makes analysis less crisp, but it also keeps the door open for some of the complexity of structure–agency interactions and the relationship between intention and outcome, immediate effects and the greater picture.

Although the three cases all have a stronger presence of change agency in the path creation phase and of reproductive agency in preformation and path development, there are variations in the agency mix seen in the different cases. For instance, place-based leadership, both for maintenance and change, is most accentuated in Sogndal, while Schumpeterian entrepreneurship has been most accentuated in Flåm. Also, there has been more change agency in Flåm than in the two other cases. In Odda change agency has continued through path development, but it is being enacted by different actors than those who created the path.

The differences between the paths, both in agency patterns and type of tourism, point towards different future developments. Covid-19 created a problematic situation in 2020, which might represent a critical juncture for places specialized in tourism. This is not so much the case in Sogndal, where mountain sport tourism was already mostly focused on the national market. The positive trend in student numbers continued in autumn 2020 too. However, the resistance recently faced by maintenance leadership might be a step towards changing dynamics, which could speed up, slow down or otherwise alter the tourism path development. In Odda Covid-19 represents a significant challenge, but it seems to have provoked temporary adaptation rather than long-term change agency. Continued action for strengthening the tourism path indicates that self-reinforcing dynamics are in play, and that place-based leadership is starting to consolidate around the hiking tourism path. This illustrates how agency responds to past agency and thus has an evolutionary element to it. This is also the case in Flåm, where the tourism sector is experiencing a double problematic situation, with the challenge to adapt to new environmental regulations and a significant loss of income in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Yet local actors are investing in green technological solutions while doing institutional work in order to shape the environmental regulations to their advantage. Thus, change agency and reproductive agency are being enacted simultaneously and partly by the same actors. Accordingly, at this critical juncture the Flåm tourism path seems to continue as a dynamic process, as suggested by Martin (Citation2010).

The agency perspective of this paper contributes towards an understanding of how human actors may foster regional development. The importance not only of willingness and ability to change, but also of building upon lasting structures, emerges from the investigation of changing agency patterns in the course of path evolution. By directing attention towards reproductive agency in addition to change agency, the paper also contributes to nuancing the understanding of agency and to partially reconciling agency with an evolutionary perspective. While change agency is key to path creation, reproductive agency is necessary for the path to develop. The observed passages between phases characterized by different agency patterns also indicate that the more radical change agency is often connected to critical junctures, which at least partly stem from exogenous events or developments. Thus, new paths cannot be explained by local agency or exogenous shocks alone, but by a mix of local and exogenous developments that offer opportunities and create pressure for change. Accordingly, it emerges that actions contributing to change can be intended and strategic, but also reactive, as they are influenced by problematic situations.

The paper has utilized two supplementary conceptual tools in understanding the relationship between endogenous and exogenous forces. A distinction between local and non-local agents draws to the fore the key role of non-local actors in bringing new resources (Binz et al., Citation2016; Miörner & Trippl, Citation2019), as well as the disproportionate influence they may thus gain (Hambleton, Citation2019). The concept of critical junctures represents another type of link between local path evolution and wider developments, which is also a step towards taking into account the changing conditions for agency across time. The study has some limits as it draws solely on cases from the rural tourism industry, which has several peculiarities relative to other industries. Accordingly, agency and its relationship with exogenous events and processes in industry development should be further investigated and nuanced in future research in other regions and industries. The multiscalarity of agency also needs to be further explored and conceptualized beyond the local, non-local distinction. In addition, new questions emerge regarding the background, knowledge and social networks of key agents in industry path development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Professor Stig-Erik Jakobsen and Associate Professor Rune Njøs are thanked for good discussions of the work leading up to this paper. A special thanks also to the editor and two anonymous referees for providing valuable inputs.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Via ferrata (in Italian) means iron path and refers to steep mountain paths equipped with fixed ladders, cables and bridges.

2. A public company that develops, owns and finances national infrastructure for innovation and industry development.

REFERENCES

- Araujo, L., & Harrison, D. (2002). Path dependence, agency and technological evolution. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 14(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320220125856

- Battilana, J. (2006). Agency and institutions: The enabling role of individuals’ social position. Organization, 13(5), 653–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508406067008

- Battilana, J., Leca, B., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. The Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 65–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903053598

- Baumol, W. J. (2010). The microtheory of innovative entrepreneurship (Kauffman Foundation Series on Innovation and Entrepreneurship). Princeton University Press.

- Benneworth, P., Pinheiro, R., & Karlsen, J. (2017). Strategic agency and institutional change: Investigating the role of universities in regional innovation systems (RISs). Regional Studies, 51(2), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1215599

- Binz, C., Truffer, B., & Coenen, L. (2016). Path creation as a process of resource alignment and anchoring: Industry formation for on-site water recycling in Beijing. Economic Geography, 92(2), 172–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1103177

- Boschma, R., Coenen, L., Frenken, K., & Truffer, B. (2017). Towards a theory of regional diversification: Combining insights from evolutionary economic geography and transition studies. Regional Studies, 51(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1258460

- Brouder, P. (2017). Evolutionary economic geography: Reflections from a sustainable tourism perspective. Tourism Geographies, 19(3), 438–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2016.1274774

- Capoccia, G., & Kelemen, D. R. (2007). The study of critical junctures: Theory, narrative, and counterfactuals in historical institutionalism. World Politics, 59(3), 341–369. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887100020852

- Coe, N. M., & Jordhus-Lier, D. (2011). Constrained agency? Re-evaluating the geographies of labour. Progress in Human Geography, 35(2), 211–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510366746

- Coenen, L., Davidson, K., Frantzeskaki, N., Grenfell, M., Håkansson, I., & Hartigan, M. (2020). Metropolitan governance in action? Learning from metropolitan Melbourne’s urban forest strategy. Australian Planner, 56(2), 144–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2020.1740286

- Cruickshank, J., Ellingsen, W., & Hidle, K. (2013). A crisis of definition: Culture versus industry in Odda, Norway. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 95(2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/geob.12014

- David, P. A. (1988). Path dependence: Putting the past into the future of economics (Stanford University Institute Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences Report No. 533). Stanford University Press.

- Dawley, S., MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., & Pike, A. (2015). Policy activism and regional path creation: The promotion of offshore wind in North East England and Scotland. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(2), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu036

- de Cássia Ariza da Cruz, R. (2019). For a scientific and critical approach to tourism in geography. In D. K. Müller (Ed.), A research agenda for tourism geographies (pp. 42–49). Edward Elgar.

- Dieter, K. M. (2019). A research agenda for tourism geographies. Edward Elgar.

- Elert, N. (2019). Introduction: Why entrepreneurship? In Elert, N., Henrekson, M., & Sanders, M. (Eds.), The entrepreneurial society (pp. 1–23). Springer Link.

- Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023. https://doi.org/10.1086/231294

- Fløysand, A., & Jakobsen, S.-E. (2007). Commodification of rural places: A narrative of social fields, rural development, and football. Journal of Rural Studies, 23(2), 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2006.09.012

- Fløysand, A., Njøs, R., Nilsen, T., & Nygaard, V. (2017). Foreign direct investment and renewal of industries: Framing the reciprocity between materiality and discourse. European Planning Studies, 25(3), 462–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1226785

- Fredin, S., Miörner, J., & Jogmark, M. (2019). Developing and sustaining new regional industrial paths: Investigating the role of ‘outsiders’ and factors shaping long-term trajectories. Industry and Innovation, 26(7), 795–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2018.1535429

- Garud, R., & Karnøe, P. (2003). Bricolage versus breakthrough: Distributed and embedded agency in technology entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 32(2), 277–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00100-2

- Garud, R., Kumaraswamy, A., & Karnøe, P. (2010). Path dependence or path creation? Journal of Management Studies, 47(4), 760–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00914.x

- George, A., & Bennett, A. (2005). Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. MIT Press.

- Grillitsch, M., Asheim, B., & Trippl, M. (2018). Unrelated knowledge combinations: The unexplored potential for regional industrial path development. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(2), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy012

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Hambleton, R. (2019). Place-based leadership beyond place: Exploring the international dimension of civic leadership. Paper presented at the City Futures IV Conference, Dublin, Ireland.

- Hardanger, D. M. O. (2015). Moglegheitsstudie Trolltungaturismen [Possibility report regarding tourism to Trolltunga]. Hardanger DMO, NCE Tourism and Odda Municipality; Reisemål Hardangerfjord.

- Hassink, R. (2010). Locked in decline? On the role of regional lock-ins in old industrial areas. In R. Boschma & R. Martin (Eds.), The handbook of evolutionary economic geography (pp. 450–470). Edward Elgar.

- Hordaland Fylkeskommune. (2009). Reiselivsstrategi for horaland 2009–2015.

- Isaksen, A. (2018). From success to failure, the disappearance of clusters: A study of a Norwegian boat-building cluster. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(2), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy007

- Isaksen, A., Jakobsen, S.-E., Njøs, R., & Normann, R. (2019). Regional industrial restructuring resulting from individual and system agency. The European Journal of Social Science Research, 32(32), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2018.1496322

- Iversen, E. K., Haukland Løge, T., Jakobsen, E. W., & Sandvik, K. (2014). Verdiskapingsanalyse av reiselivsnæringen i Norge – Utvikling og fremtidspotensial [Value creation analysis of the tourism sector in Norway – Development and future potentials]. Menon Economics.

- Johnsen, A. M., Brandshaug, S., & Skrede, J. C. (2009). Reiselivsplan Sogn og Fjordane 2010–2025. Sogn og Fjordane Fylkeskommune.

- Jolly, S., Grillitsch, M., & Hansen, T. (2020). Agency and actors in regional industrial path development: A framework and longitudinal analysis. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 111, 176–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.013

- Kurikka, H., & Grillitsch, M. (2020). Resilience in the periphery: What an agency perspective can bring to the table (Paper No. 2020/07; Papers in Innovation Studies). CIRCLE, Lund University.

- Kyllingstad, N., & Rypestøl, J. O. (2019). Towards a more sustainable process industry: A single case study of restructuring within the Eyde process industry cluster. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 73(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2018.1520292

- Lawrence, T. B., Suddaby, R., & Leca, B. (2011). Institutional work: Refocusing institutional studies of organization. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20(1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492610387222

- MacKinnon, D., Dawley, S., Pike, A., & Cumbers, A. (2019a). Rethinking path creation: A geographical political economy approach. Economic Geography, 92(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- MacKinnon, D., Dawley, S., Steen, M., Menzel, M.-P., Karlsen, A., Sommer, P., Hopsdal Hansen, G., & Endresen Normann, H. (2019b). Path creation, global production networks and regional development: A comparative international analysis of the offshore wind sector. Progress in Planning, 130, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2018.01.001

- Mead, G. B. (1932). The philosophy of the present. University of Chicago Press.

- Martin, R. (2010). Roepke lecture in economic geography – Rethinking regional path dependence: Beyond lock-in to evolution. Economic Geography, 86(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Milano, C., Novelli, M., & Cheer, J. M. (2019). Overtourism and degrowth: A social movements perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1857–1875. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1650054

- Miörner, J., & Trippl, M. (2019). Embracing the future: Path transformation and system reconfiguration for self-driving cars in west Sweden. European Planning Studies, 27(11), 2144–2162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1652570

- Musiolik, J., Markard, J., & Hekkert, M. (2012). Networks and network resources in technological innovation systems: Towards a conceptual framework for system building. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 79(6), 1032–1048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2012.01.003

- Njøs, R., Sjøtun, S. G., Jakobsen, S.-E., & Fløysand, A. (2020). Expanding analyses of path creation: Interconnections between territory and technology. Economic Geography, 96(3), 266–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2020.1756768

- Odda Municipality. (2000). Vedlegg 1 til søknad om omstillingsnmidler [Application for transition resources, Attachment 1]. Odda Municipality.

- Pike, A., MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., Dawley, S., & McMaster, R. (2016). Doing evolution in economic geography. Economic Geography, 92(2), 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1108830

- Randelli, F., Romei, P., & Tortora, M. (2014). An evolutionary approach to the study of rural tourism: The case of Tuscany. Land Use Policy, 38, 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.11.009

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interests, and the business cycle. Harvard University Press.

- Smith, D. J., Rossiter, W., & McDonalt-Junor, D. (2017). Adaptive capability and path creation in the post-industrial city: The case of Nottingham’s biotechnology sector. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 10(3), 491–508. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx010

- Sotarauta, M. (2016). Place leadership, governance and power. Administration, 64(3/4), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1515/admin-2016-0024

- Sotarauta, M., Beer, A., & Gibney, J. (2017). Making sense of leadership in urban and regional development. Regional Studies, 51(2), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1267340

- Sotarauta, M., & Suvinen, N. (2018). Institutional agency and path creation: Institutional path from industrial to knowledge city. In A. Isaksen, R. Martin, & M. Trippl (Eds.), New avenues for regional innovation systems: Theoretical advances, empirical cases and policy lessons (pp. 85–104). Springer.

- Sotarauta, M., Suvinen, N., Jolly, S., & Hansen, T. (2020). The many roles of change agency in the game of green path development in the North. European Urban and Regional Studies https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776420944995

- statistikknett.no. (2019). Hotellovernattinger fra utlendinger i 1420Sogndal. https://www.statistikknett.no/fjordnorge/Default.aspx

- Steen, M. (2016). Reconsidering path creation in economic geography: Aspects of agency, temporality and methods. European Planning Studies, 24(9), 1605–1622. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1204427

- Sunley, P. (2008). Relational economic geography: A partial understanding or a new paradigm? Economic Geography, 84(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2008.tb00389.x

- Sydow, J., Lerch, F., & Staber, U. (2010). Planning for path dependence? The case of a network in the Berlin–Brandenburg optics cluster. Economic Geography, 86(2), 173–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2010.01067.x

- Sydow, J., Schreyögg, G., & Koch, J. (2009). Organizational path dependence: Opening the black box. The Academy of Management Review, 5(2), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.34.4.zok689

- Vestlandsrådet. (2014). Reiselivsstrategi for Vestlandet 2013–20.

- Weik, E. (2011). Institutional entrepreneurship and agency. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 41(4), 466–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.2011.00467.x

- Wigestrand, I. L. (2018). Reiselivets påvirkning på Odda som lokalsamfunn: Økonomiske, sosiale og miljømessige konsekvenser [Master’s thesis]. Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

- Yttri, G. (2008). Frå skuletun til campus: Soga om Høgskulen i Sogn og Fjordane. Skald.