ABSTRACT

While the enabling role of the state in the financialization of urban development has been widely noted, the changing and variegated roles of different state actors have been less explored. This paper investigates this issue based on chengtou as financial agencies in China. First, we show that financialization is not merely a state-led process, but that the state also restricted financialization at different stages. Second, albeit with stringent central regulations, local states have striven to support chengtou, which demonstrates intrastate divergence. Third, we illustrate the performance of local states across regions to show that financialization further differentiates the patterns of local financing.

INTRODUCTION

While financialization has been a pervasive phenomenon in both developed and developing countries, it is variegated and locally embedded (Aalbers, Citation2017; Lapavitsas & Powell, Citation2013; Rethel & Thurbon, Citation2020). The state is essential in facilitating and enabling the financialization of urban development because financial deregulation and financial policies set the background for capital circulation (Ashton et al., Citation2016; Halbert & Attuyer, Citation2016; Weber, Citation2010). While some states are relatively passive with regard to financialization, some scholars have observed state-led or state-driven financialization in that states proactively intervened in and orchestrated financialization (Belotti & Arbaci, Citation2020; Gotham, Citation2016; Lagna, Citation2016; Yeşilbağ, Citation2019). In these cases, states do not merely enable financialization but have a central role in financialization. Nevertheless, various states seem to act in the same direction of facilitating financialization either proactively or passively. This paper, however, enquires into the exact roles of different state actors in the process of financialization. Focusing on the role of the state, we aim to unravel the Chinese characteristics of financialization and contribute to the understanding of the relationship between state and finance based on the development of chengtou (short for chengshi touzi gongsi, urban development and investment corporations) as financial agencies.

The state of China has a central role in the economy in terms of its control over strategic sectors and the state-controlled financial environment (Tsai, Citation2015; Wu et al., Citation2020). China has experienced the financialization of urban development since the global financial crisis (GFC). To counteract the recession caused by the crisis, the central state initiated a plan to stimulate the national economy by investing 4 trillion yuan in the built environment over two years (State Council, Citation2008). This stimulus plan triggered the financialization of urban development in China, which is extensively using financial agencies and instruments to invest in the built environment. Therefore, the financialization of urban development in post-crisis China is a state-led project (Bai et al., Citation2016; He et al., Citation2020). However, we do not simply argue that state-led financialization happens in China. Instead, we aim to unpack the multiple and divergent roles of different state actors in the financialization of urban development.

Chengtou are the entry point for examination of this issue because they connect the state and the financial market as financial intermediaries, especially in the post-crisis era. Chengtou are state-owned enterprises (SOEs) specialized in urban development and investment. Their business varies from infrastructure construction and utility management to large-scale land development. Beyond all these functions, chengtou are essential to the financing of these projects (Wong, Citation2013). After the GFC, chengtou expanded their financial function to support the stimulus plan. As the plan left looming problems with local debt, the central government then adopted rigid management regarding local borrowing and asked that chengtou be detached from local states from 2014 onwards. Although some studies have addressed the importance of chengtou in Chinese urban development (Jiang & Waley, Citation2018; Li & Chiu, Citation2018; Shen et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2011), the impacts of these regulations have been unexplored. Besides, chengtou are created by local states, while the central state regulates the financial functions of chengtou using policy. Therefore, the development of chengtou possibly engenders divergence within the state apparatus. Focusing on the development of chengtou as financial agencies, we will unpack the complexity of the state’s involvement in financialization based on longitudinal and cross-regional analyses.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section will first review the literature on the financialization of urban development, which demonstrates the essential role of the state in it. It will also review the characteristics of financialization and the state in China. Stemming from the literature, the third section will explain cases and methodology. The fourth section will show that the central state dominates the evolution of chengtou using policy. Fifth, we will illustrate how local governments support the financial operations of chengtou through state-owned assets. The sixth section will illustrate the performance of chengtou across regions and explain the variations of local states. Finally, the conclusion will discuss the findings.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The complexity of the state in the financialization of urban development

Financialization has been widely adopted to illustrate financial expansion in various sectors (Krippner, Citation2005; Pike & Pollard, Citation2010). In urban studies, financialization is an umbrella term to illustrate the pervasiveness of finance at various scales and in connecting local politics, individuals and the urban landscape with global financial flows (Aalbers, Citation2015; Fields, Citation2017). This research focuses on the financialization of urban development, which means that financial intermediaries, instruments and products are mobilized to channel ‘investments in the forms of equity and debt into urban production’ (Halbert & Attuyer, Citation2016, p. 1347). An emerging body of literature has illustrated the financialization of housing (Aalbers, Citation2017), infrastructure (Ashton et al., Citation2016; O’Brien et al., Citation2019), and urban development projects (Gotham, Citation2016; Guironnet et al., Citation2016). The inflow of financial capital into urban spheres may be partly understood through the capital switch from commodity production to the built environment (Harvey, Citation1978). Moreover, in recent studies, the GFC should also be integrated to account for the pervasiveness of financialization in the urban landscape (Fields, Citation2017).

At the same time, financialization is ‘fundamentally fragmented, path-dependent and variegated’ (Aalbers, Citation2017, p. 544). Generally speaking, in the Global North, financialization happens within systematic austerity, while subordinated financialization happens in the Global South due to the global financial hierarchies (Fernandez & Aalbers, Citation2019; Yeşilbağ, Citation2019). Albeit with similar supra-national conditions, ‘historical and institutional variation is a necessary feature of financialization’ (Lapavitsas, Citation2013, p. 800). Therefore, many scholars have suggested granular and detailed analyses to illustrate the exact process of financialization and its concrete modalities (Christophers, Citation2015; Pike et al., Citation2019).

The role of the state is critical to understanding the process of financialization as well as its variegated forms. The literature has shown the essential role of the state in facilitating and shaping distinct forms of financialization in both the Global North and Global South (Fernandez & Aalbers, Citation2019; Karwowski, Citation2019; Lagna, Citation2016). There have been three strands of opinions. First, the most noted role of the state is enabling financialization via monetary and financial policies, which set the contexts for financialization in urban spheres (Aalbers, Citation2019; Guironnet et al., Citation2016). In recent studies, financial deregulation was largely caused by the GFC and ensuing systematic austerities (Christophers, Citation2019). The second strand of the literature stresses intensive intervention of the state in financialization. That is, beyond the enabling role of the state in financialization, some states have been central to driving the financialization of urban development. For instance, Gotham (Citation2016) contends that financialization is a conscious state project to legally promote specific financial instruments. In Turkey, Yeşilbağ (Citation2019) asserts that the state ‘drives the housing–finance nexus’ rather than just enabling financialization. In these practices, the state not only permits or facilitates financialization but intervenes in the financial mechanism by acting as active actors. The third strand of literature poses critical reflection on the state–finance relationship and highlights the risk of the state when entangling with the financial market. Scholars argue that financial market also reshapes the state and leads to the financialization of the state (Karwowski, Citation2019; Peck & Whiteside, Citation2016). Karwowski (Citation2019) defines ‘financialisation of the state broadly as the changed relationship between the state, understood as sovereign with duties and accountable towards its citizens, and financial markets and practices, in ways that can diminish those duties and reduce accountability’ (p. 1001). For instance, in Paris, financial actors were empowered and the city government made compromises to ensure funding for a development project (Guironnet et al., Citation2016). In Ireland, Waldron (Citation2018) shows that financial actors co-opted state institutions to incorporate financial rationales into policymaking. Therefore, scholars warn that financialization undermines the functions of the state (Weber, Citation2010).

Nevertheless, the complex roles of the state in financialization have been insufficiently examined. The complexity lies on two dimensions. First, inspired by Christophers (Citation2019), urban financialization can be understood as a response to its specific financial conjuncture. As the financial conjuncture is dynamic, the state may facilitate financialization at some times while exerts its control later. For instance, based on practices in Chicago, Ashton et al. (Citation2016) argue that financialization is a recursive policy project but each round of transactions leads towards more financialization. While many scholars are pessimistic about the effects of state re-regulation (Halbert & Attuyer, Citation2016), the roles of the state need to be verified based on a longitudinal analysis. The other dimension of the complexity of the state in financialization is due to heterogeneity within the state apparatus, leading to the divergent and even countervailing roles of various state actors (Yrigoy, Citation2018). As argued by Aalbers (Citation2017), ‘some state agents actively create the conditions for the financialization of housing … while other state agents may try to limit financialization pressures’ (p. 550). As ‘the state is a complex and polymorphous reality’ (Jessop, Citation2015, p. 31), different state strategies pursued by various actors also engender tension (Yrigoy, Citation2018). These arguments inspire the understanding of state and financialization by pointing out the contradictions within the state during the process of financialization, which have been insufficiently explored. Moreover, understanding the complexity of the state in financialization could also shed light on the financialization of the state. Jessop (Citation2015) argues that ‘as the state intervenes more in various spheres of society … its own unity and distinctive identity diminish as it becomes more complex internally, its powers are fragmented across branches and policy networks, and coordination problems multiply’ (p. 89). In this sense, the financialization of the state does not necessarily mean reduced accountability (cf. Karwowski, Citation2019). It means that financialization deepens fragmentation and complexity within the state.

Therefore, our focus is the evolving process of financialization and the multiple roles of state actors during the process. We first notice that the Chinese state is dominant in promoting financialization in the post-crisis era, which demonstrates similarities compared with the Global North. However, China has not experienced a continuation of neoliberal logic because the state does not further step back to give space for the market. Instead, the state proactively used financial instruments and products to achieve its goal. Second, albeit with some attempts, the state has been generally analysed as a whole rather than as an institutional ensemble (Ashton et al., Citation2016). This leads to the simplification of the relationship between the state and finance. It also hinders our understanding of the extent to state financialization. Based on the case study of chengtou in China, we enquire into the exact roles of the state by asking who they are and how they act at different stages of financialization.

The Chinese state in financialization

This paper unpacks the complexity of the state in financialization in China. Capitalism in China demonstrates the characteristics of both state authority and indigenous capitalism (Peck & Zhang, Citation2013). To make contradictory facts coherent, scholars have adopted terms such as ‘authoritarian capitalism’ and ‘state capitalism’ (Petry, Citation2020; Tsai, Citation2015). At the same time, some scholars have emphasized the ‘long-lasting contradictions’ of the Chinese state (Howell, Citation2006; Peck & Zhang, Citation2013). Nonetheless, the consensus is that the state retains a central role in the development of China. In the urban development of China, the role of the state has also been highlighted, especially at the local level (Chien, Citation2013; Wang et al., Citation2011; Wu, Citation2018). Local officials act as entrepreneurs to pursue growth through investing in the built environment (Shen & Wu, Citation2017; Yang & Wang, Citation2008). Wu (Citation2018) defines this as ‘state entrepreneurialism’ in that the state dominates entrepreneurial activities by deploying market instruments.

The state is essential to understanding financialization in China as the state not only facilitates financialization but is also a critical player. Petry (Citation2020) argues that the Chinese characteristics of financialization lie in that ‘states can also (partially) exert control over, actively manage and shape financialization’ (p. 213). Moreover, the state is adept in devising market instruments to exert its influence. Wang (Citation2015) illustrates the Chinese ‘shareholding state’ in that the state uses financial means such as shareholding to manage its ownership and assets. Therefore, the state also demonstrates its power in the financial development of China.

The financialization of urban development in post-crisis China has been found in various aspects, including housing (Wu et al., Citation2020), urban redevelopment (He et al., Citation2020) and land development (Pan et al., Citation2017; Wu, Citation2019). These phenomena largely derive from a state plan to stimulate the economy via direct investment to combat the recession caused by the GFC. In this sense, state-led financialization in China can be understood as a state project to tackle stagnation in the post-crisis era (He et al., Citation2020). Based on the government-guided investment fund, Pan et al. (Citation2020) illustrate that ‘state-led financialization in China has strengthened rather than weakened the influence of the state in the economy’ (p. 1). While the essential role of the state in promoting and facilitating the process of financialization has been widely noted, the tension within the state during the process has been largely overlooked.

This research aims to unravel the changing and multiple roles of the state in shaping and regulating financialization based on the investigation of chengtou. Chengtou are typical entities at the interface of the state and the financial market, which partly represents the state and follows the rules of the financial market. The emergence of chengtou in the 1990s had institutional origins including local motivations for growth and restrictions on local borrowing (Wong, Citation2013). Chengtou have various forms and are usually responsible for specific projects, such as redevelopment projects (Su, Citation2015), new town development projects (Li & Chiu, Citation2018) and mega-events (Li & Xiao, Citation2020). As for operation, chengtou rely heavily on state-owned land as assets (Zhang, Citation2018) and land conveyance fees (LCFs) for debt repayment (Feng et al., Citation2020; Jiang & Waley, Citation2018). The financial role of chengtou expanded in the post-crisis era. The People’s Bank of China (PBC) supported local governments to establish local government financial vehicles (LGFVs; difang rongzi pingtai) and innovate financial instruments (PBC, Citation2009). As a result, local governments transformed, established or acknowledged many government-related agencies as LGFVs, with chengtou comprising the largest portion. Given this backdrop, chengtou have expanded their financial instruments from land-backed loans to bonds, securities and even shadow banking (Chen et al., Citation2020). Considering the close relationship between the state and chengtou, scholars have emphasized the financial risks associated with chengtou (Fan & Lv, Citation2012).

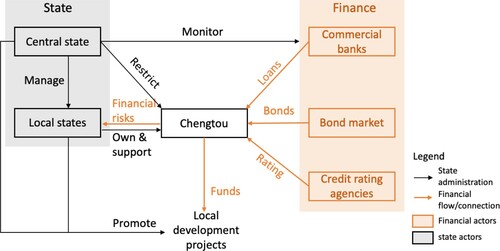

This paper analyses chengtou by putting them in the state–finance relationship and mapping out key actors (). First, chengtou reflect the changing relationship between the state and the financial market. Chengtou are established by local governments. They have a function to raise funds from the financial market to support local development projects. In this sense, the state uses chengtou to invite capital and investors. Nevertheless, the Chinese state has a strong power over the financial system, which enables the state to regulate the financing process of chengtou. Through policies and institutions, the central state stipulates whether a financial channel could be used and how it could be used by chengtou. For example, to implement pump-priming strategies, the central state opened up the bond market and offered cheap credit for chengtou to issue bonds. Conversely, the central state could also tighten its control over the financing channel of chengtou to mitigate risks, as it did in 2014.

Chengtou also reflect the tension within the state. For the state, the mission of chengtou is to promote local development rather than simply raising funds. Therefore, both the central state and local states generally promote the operation of chengtou. Local states have provided strong support, including capital and guarantee to chengtou to maintain their financial function. With government support, chengtou get loans and bonds to invest in local development projects. These projects usually reflect entrepreneurial goals of local states. As many projects could hardly earn profits in a short term, the liability of chengtou climbs. Due to the close relationship between local states and chengtou, the financial risks of chengtou could be partly transferred back to local states. The central state is sensitive to the financial risks brewed in the financial mechanism of chengtou. Therefore, it tends to restrain the financial operation of chengtou to cope with risks. However, local states have a strong will to maintain chengtou as both financing agencies and development agencies. The treatment towards chengtou may engender divergence among state actors. Being aware of the divergent roles of the central state and local states towards chengtou, we can unpack the complexity of the state’s involvement in the financialization of urban development.

METHODOLOGY

Based on cases of chengtou, this paper aims to uncover the complex roles of the Chinese state in the financialization of urban development. As the complexity of the state consists of both longitudinal transformations and intrastate divergence, we study chengtou on two dimensions. First, we examine the changing roles of the state in the development of chengtou to reveal the complexity of the state longitudinally. We conduct desk research at the central level. We collect policy documents promulgated by main state actors at the central level, including the State Council, PBC, the Ministry of Finance (MOF), the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), and the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC). These documents are publicly available. The data are analysed using thematic analysis to illustrate changing regulations and impacts on chengtou.

Second, we examine divergence within the state in two aspects. We first explain how local states supported the financial operations of chengtou before and after 2014. We also use two cases to illustrate the operations in detail. The analysis of these two chengtou is based on data collected from auditing reports and rating reports released on the chinabond website. By tracing the money flow, we discover the financial support provided by local states. The other aspect of divergence within the state lies in the variations of local states across regions. We investigate regional differentiation in two aspects, including the distribution of chengtou and chengtou bonds. For the distribution of chengtou, we rely on data released by the CBRC. The CBRC is authorized to monitor all LGFVs based on a national list, and most chengtou are included in the list. Therefore, we extracted chengtou from the LGFV list to get a national dataset of chengtou. For the second indicator, we use chengtou bond data retrieved from the Wind dataset. Moreover, we illustrate the divergence of local states by comparing Zhejiang and Guizhou provinces.

THE CHANGING ROLES OF THE CENTRAL STATE IN THE EVOLUTION OF CHENGTOU

First, following the trajectory of chengtou, we find that the central state is decisive in the financialization of urban development in China. The central state first encouraged the establishment of chengtou to promote urban development, then mobilized chengtou to cope with recession after the GFC, but soon restricted chengtou to limit financial risks.

Chengtou were first established to deal with the insufficiency of local funds in the 1980s. In 1986, the Shanghai government planned to attract overseas investment to promote urban infrastructure and economic development. To undertake the whole plan and manage funds, Shanghai Jiushi corporation (an SOE) was established by the Shanghai government in 1987. It mobilized US$1.4 billion for urban infrastructure projects including Nanpu bridge and metro Line 1. Hence, Shanghai Jiushi was the first chengtou in China. Considering the success of Shanghai, the central state encouraged local states to innovate financing approaches to facilitate urban infrastructure in 1991. The tax sharing system in 1994 further restricted the fiscal power of local governments while devolving almost all municipal responsibilities to local states (Wu, Citation1999). Furthermore, before 2014 the budget law prohibited local states from borrowing. To circumvent the law and fill the financial gap, subnational governments established chengtou. Chengtou are shareholder corporations, but local states at various administrative levels are usually the only shareholders. In this sense, chengtou are arms of local states. Apart from infrastructure projects, chengtou were also in charge of land development, facilities, maintenance and management before the GFC. Therefore, chengtou were the creatures to deal with both central fiscal control and local pressures for urban development.

After the GFC, the financial function of chengtou expanded as they were mobilized by the central state to counteract recession. Confronting the GFC, China strove to stimulate the economy and absorb surplus labour via pump-priming measures (State Council, Citation2008). As these measures were estimated to cost 4 trillion yuan up to 2010, the whole plan was also called a Four-trillion Plan. The central state promised to provide only 1.8 trillion yuan, while local states were responsible for the rest. However, local states were not allowed to borrow. Meanwhile, the PBC promoted local governments’ use of LGFVs to borrow externally (PBC, Citation2009). Given this context, local states acknowledged previously existing chengtou as LGFVs to seek finance in the specific period. They also set up new chengtou and other government institutions as LGFVs. Therefore, the number of chengtou and the amount of chengtou debts soared. Chengtou expanded their financial capabilities by issuing chengtou bonds, which were also promoted by the central state. Most chengtou did not issue bonds before 2008 because the NDRC stipulated that bond issuance should not exceed 20% of a fixed-asset investment project. However, after the GFC, the NDRC loosened the criteria for issuing enterprise bonds to facilitate the entry of chengtou into the bond market (NDRC, Citation2008). The State Council also prioritized bonds related to infrastructure (State Council, Citation2008). With the endorsement of the State Council and the NDRC, chengtou bonds started to increase.

Although the expansion of chengtou was supported by the central state, their financial function developed beyond the expectations of the central state. According to a report of the National Audit Office in 2013, local government debt was 10.89 trillion yuan, with an extra 7 trillion yuan of contingent liabilities. Most of the contingent liabilities were borrowed by chengtou. The amount excessively exceeded the original target. The expansion of chengtou and chengtou debts caused severe problems, including soaring housing prices and shadow banking (Ambrose et al., Citation2015). Especially in the less-developed regions, extensive borrowing led to the abandonment of unfinished projects, which caused serious financial and social problems (Deng, Citation2019).

To limit financial risks, the State Council forced LGFVs to be detached from local states. Meanwhile, injecting assets including reserved land and other types of public assets into LGFVs was forbidden (State Council, Citation2014). Moreover, since 2014 the central state has opened an outlet for local states to borrow by allowing local states to issue local government bonds. By restricting LGFVs and promoting local government bonds, the central state has tightened control over local borrowing.

Based on these policy transitions, we show that the central state dominates the development of chengtou as financial agencies. Nevertheless, the roles of the state have been transformed. In the first stage, the central state promoted the establishment of chengtou as development agencies, and the financial function of chengtou was secondary. After the GFC, the state actively embraced the financial market and facilitated chengtou as its representatives in the financial market. However, the state soon realized there were local borrowing problems. It halted local government borrowing via chengtou from 2014. Therefore, the central state not only enables or promotes financialization but also effectively restricts and regulates financialization at different stages.

THE CONSISTENT SUPPORT OF LOCAL STATES TO CHENGTOU

While the central state required chengtou to transform and not to finance local states, local states consistently supported the financial operations of chengtou. This section will illustrate how local states underpinned the operations of chengtou before and after the GFC, and, more importantly, how local states respond to central regulations today.

The financial mechanism of chengtou before the GFC consisted of three steps, including capital injection, fund-raising and repayment. First, local states established chengtou with capital injection. Land development was the main function for chengtou, and they were in charge of designated areas assigned by the local states. Second, chengtou leveraged state-owned assets to seek funds. A normal practice was to use land as collateral to get loans from banks (Tsui, Citation2011). After receiving funds, chengtou invested in local development projects. Finally, chengtou could receive LCFs from local states to repay the primary cost of land development and facilities. Therefore, chengtou initially raised funds for first-step development and then waited for several years to get repaid. Local states could avoid borrowing to conduct development projects and shift the financial risks to chengtou.

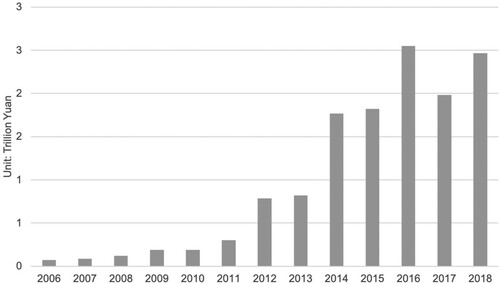

These operations continued after the GFC. Scholars believe that LCFs were still the major source to repay chengtou debts (Ang et al., Citation2015; Pan et al., Citation2017), which also pushed up land prices and led to soaring housing prices (Ambrose et al., Citation2015). Apart from land-backed loans, many chengtou entered the bond market to issue enterprise bonds (chengtou bonds) after the GFC. Moreover, there was a very strong boom in chengtou bonds (), which was a delayed effect of the stimulus plan (Chen et al., Citation2020). Chengtou bonds were adopted as a refinancing tool to repay the accumulated debts of the stimulus plan.

Local states used to be essential to facilitate chengtou into the bond market by enhancing their financial performance. For instance, Jiaxing chengtou, an SOE established by the Jiaxing municipal government, issued a seven-year bond of 1.7 billion yuan in 2008. The municipal government supported Jiaxing chengtou by injecting land, providing guarantees and giving subsidies. The Jiaxing government first injected state-owned land as assets into Jiaxing chengtou before the bond issuance, comprising nearly 20% of the assets of Jiaxing chengtou and hence reducing its leverage ratio. Second, the issuance of the chengtou bond was guaranteed by the build-and-transfer protocols signed with the Jiaxing government. The Jiaxing government promised to pay 3.4 billion yuan to Jiaxing chengtou within five years. Therefore, repayment for the bond was guaranteed. Third, the Jiaxing government gave subsidies to Jiaxing chengtou every year to cover its operating losses. By so doing, Jiaxing chengtou maintained positive income during the term of the bond. Therefore, local states used to be pivotal in helping chengtou to issue bonds.

However, in 2014, the central state asked chengtou to detach and opened an outlet for local states to borrow. Although issuing local government bonds is more transparent than borrowing from chengtou, local states could hardly discard chengtou for three reasons. First, as most chengtou are used to conduct urban projects and land development for local governments, seeking funds for these projects has been the usual routine. Second, chengtou have been closely connected with local governments in terms of staff appointments and asset ownership. Therefore, despite the regulations on local financing in 2014, chengtou remain trustworthy partners for local governments. Moreover, issuing local government bonds increases accountability at the sacrifice of local autonomy. It is the provincial-level government that is eligible to issue bonds, and the MOF controls the total amount. Lower level governments, including district-level, county-level and township governments, do not have direct access to the bond market. They need approval from all the upper levels. Thus, the local government bond system recentralizes fiscal power. On the contrary, chengtou operate fully under the control of local states. Therefore, using chengtou for finance is still attractive.

To keep chengtou as local financial agencies, local states help them to transform and circumvent central manipulation. For central regulations, the MOF authorizes the CBRC to monitor LGFVs. It monitors LGFVs based on a national list. CBRC requires that banks should not give loans to LGFVs on the monitoring list for new development projects in principle. LGFVs can exit from the list as long as they fulfil the requirements to become financially independent entities. These requirements include a leverage ratio of < 70% and that cash flow can cover all liabilities (CBRC, Citation2011). To circumvent the CBRC and access more financial resources like bonds, many chengtou transform themselves in order to exit from the monitoring list. A typical practice is to reorganize chengtou owned by the same level government and form a chengtou group. By doing so, chengtou can merge into companies with higher cash flow and stable returns. Moreover, chengtou with good performance after such transformations are more competitive in the financial market, which gives them greater access to it. One of their major financial instruments is still the issuing of chengtou bonds. It is tricky for the CBRC that these bonds are not government-related debts because these chengtou claim that they do not rely on local states for repayment. But the Wind database identifies a chengtou bond only if the bond is for urban development and public facilities. According to Wind, chengtou bond issuance continued to increase after 2014 (). Therefore, chengtou are still active in the financial market.

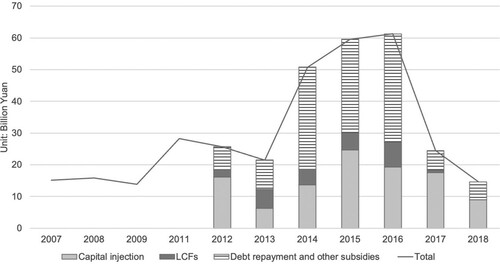

Chengtou still manage to raise funds based on the tacit knowledge that they are backed by local governments. Although the central state denies its responsibility towards chengtou debts, local states in practice act oppositely. The central state declared that the state would not be responsible for any chengtou debts after 2014. But this is not the case. For example, the Shanghai Municipal Investment Corporation (Shanghai chengtou) owned by the Shanghai municipal government is the largest chengtou in China. Based on its reports, Shanghai chengtou still receives capital injections and government subsidies to repay the interest on debts after 2017 (). In its latest credit rating report, the rating agency still emphasizes that the probability of default is low considering the relationship between Shanghai chengtou and the Shanghai government (Shanghai Brilliance Credit Rating, Citation2020). Therefore, the credit of chengtou is still backed by the credit of local states, and this diverges from the central policy.

Figure 3. Government injection to Shanghai chengtou, 2007–18.

Note: LCFs, land conveyance fees.

Data source: Credit reports of Shanghai chengtou, 2009–19.

The treatment towards chengtou after 2014 has demonstrated the tension between the central state and local states. The central state is anxious about the financial risks caused by chengtou and tries to mitigate risks by detaching chengtou from local states. However, local states do not give up chengtou not just for seeking finance but also for conducting projects. They continuously provide implicit support to chengtou. The central state is also aware of the necessity of chengtou in local development. Therefore, it requires chengtou to become independent enterprises rather than merely financing vehicles relying on local states. The central state manages chengtou using a list system, and local states help chengtou to exit the list by providing implicit support. As a result, the central government recentralizes control over chengtou through the list system. Meanwhile, some local states tried to circumvent central control through maintaining their chengtou in another form. Therefore, the tension between the central state and local states towards chengtou has been temporarily resolved by restricting the financial operations of chengtou and normalizing local borrowing through local government bonds. However, the divergence between the central state and local states still exists. The inconsistency between local states and the central state reflects the twin objectives of the state to promote development and mitigate financial risks. Local states have more focus on the former target, and the central state is more aware of the latter. This finding also echoes previous studies on the polymorphous patterns and contradictions of Chinese state rather than understanding the state using a single logic (Peck & Zhang, Citation2013).

REGIONAL DIVERGENCE OF THE STATE IN THE FINANCIALIZATION OF URBAN DEVELOPMENT

While local states have consistently supported chengtou in general, they demonstrate different characteristics in various regions. Based on the latest data on chengtou and regional performance, we analyse the contemporary status of chengtou in different regions and illustrate the various roles of local states.

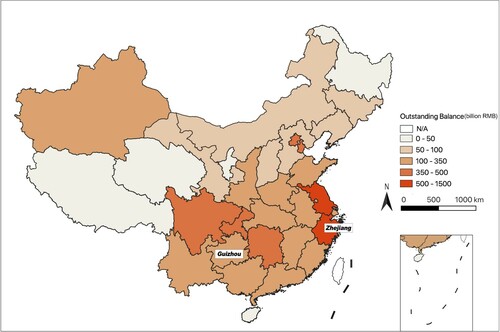

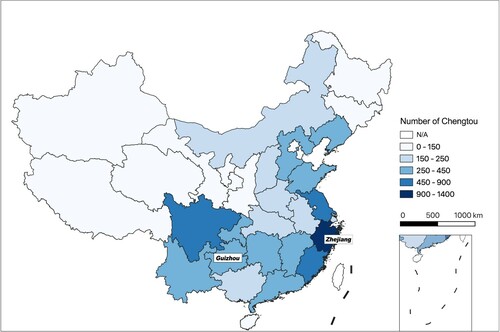

First, we find a significant divergence across regions. There are 8487 chengtou (December 2018). The eastern area is the most developed region in China, and provinces in this area have the largest number of chengtou (). Nevertheless, not only the coastal region but also provinces in the middle and western regions are active in utilizing chengtou to seek finance. The second indicator is the outstanding balance of chengtou, which is representative of the vitality of chengtou. The distribution of outstanding balance () shows that provinces in the eastern area are more active in using chengtou to seek funds. Considering the difference between the eastern and western regions of China, we make a further comparison to illustrate the divergence in detail. For the eastern region, Zhejiang province is selected because it ranks first in the number of chengtou. For the western region of China, Guizhou province is selected for two reasons. First, though the eastern region shows more vitality of chengtou and chengtou bonds, several provinces in the western region demonstrate vigour in using chengtou (). Guizhou province is one of the western provinces seizing the chance to use chengtou for massive infrastructure projects. Second, Guizhou province has the most reported local debt problems, including default issues and abandoned projects (cf. Deng, Citation2019). Therefore, these two provinces are representative to illustrate the divergence of chengtou and local financing mechanisms.

Figure 4. Number of chengtou by province, 2018.

Data source: China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC).

Local states in developed regions have more chengtou and are more active in using chengtou than their counterparts in less developed regions because of the vigour of lower level governments. For instance, Zhejiang province ranks first among 31 provinces with 1333 chengtou (). As a city in Zhejiang province, Jiaxing city has 290 chengtou, of which 223 were established by county- and town-level governments. Compared with Zhejiang, Guizhou province has only 290 chengtou in total. Of the outstanding balance of chengtou bonds in 2018, Zhejiang province has 0.53 trillion yuan, while Guizhou province has 0.21 trillion yuan. Therefore, local states in Zhejiang are more adept in using chengtou to access funds. This is largely due to the vigour of lower level governments (especially county- and town-level governments) in the eastern region (Chien, Citation2013). Besides, it should be noted that lower level states have less accessibility to local government bonds in the recentralized financial system. Therefore, for local governments, especially lower level governments in the eastern region, their reliance on chengtou to seek funds for local development has strengthened.

The central regulations on chengtou from 2014 onwards have further differentiated financial mechanisms in the eastern and western regions. The central state has required chengtou with stable income to transform so that they could become independent entities and exit from the central monitoring list. Based on the data of CBRC, 2669 chengtou exited from the monitoring list until 2018. For Zhejiang province, nearly half of its chengtou have successfully exited from the central monitoring list. As illustrated above, local states have striven to reorganize chengtou to circumvent central control. In doing so, local states manage to keep their financial arms in order to seek funds from the financial market. While for less developed regions, although local states have ambitions to use chengtou for urban development, they find it hard to transform chengtou or seek external finance. In Guizhou province, only 37 of 290 have exited from the central monitoring list.

Local states in Guizhou province could barely maintain the financial function of chengtou because of pressures from both the financial market and the central state. First, chengtou in Guizhou have accumulated a large amount of debt with a dubious level of assets since the GFC. The financial market has been rather pessimistic towards the chengtou of Guizhou. Consequently, their credit ratings are lower and financing costs are higher than for chengtou from developed regions. Therefore, using chengtou in Guizhou province to access funds is more costly than in developed regions. Second, local states in Guizhou are subsidized and under the severe surveillance of the central state to prevent financial risks. As contingent liabilities of chengtou before 2014 have been swapped for local government bonds, local governments in Guizhou have suffered from a large amount of local government bonds. In 2018, the outstanding balance of local government bonds in Guizhou province was 0.88 trillion yuan, which was more than five times the amount of general budgetary revenue (GBR). Even the interest on the debt has increased annually to more than 10% of GBR in 2019. To cover the deficit, the central state annually allocates funds twice the size of the GBR of Guizhou province. Therefore, local states in Guizhou province have become increasingly reliant on transfers from the central state. At the same time, the central state has stringently regulated local implicit borrowing since 2014. In 2017, many officials from five cities in Guizhou were punished as local states had illegally provided financial support to chengtou or had provided illegal guarantees for the debts of chengtou (MOF, Citation2017). The provincial government has urged local states to obey the guidelines of the central state. Nevertheless, the size of local debt has exacerbated the fiscal burdens of Guizhou province and engendered risks.

Comparing Zhejiang and Guizhou, we find that they are heading on two tracks of local financing. The former maintains its ability in mobilizing funds from the financial market, albeit with central regulations on local financing. It does so because chengtou in developed regions are generally accepted by the financial market, and local states are able to provide sufficient support. The latter, however, reflects a rather subsidized pattern with increasing reliance on central bailouts to cope with previous debts. Therefore, the expansion of financial agencies has exacerbated uneven development and differentiated local financing patterns.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper investigates the roles of the state in the financialization of urban development based on the development of chengtou as financial agencies. Regarding chengtou, the Chinese state demonstrates specificities in terms of its authority over the financial system and responsive bureaucratic system. Nevertheless, similar practices of state-led financialization can be found in Turkey (Yeşilbağ, Citation2019), Italy (Belotti & Arbaci, Citation2020; Lagna, Citation2016) and Belgium (Van Loon et al., Citation2018). However, even in China with a powerful state, we find the complexity of the state in financialization and contribute to the literature threefold.

First, we contribute to understanding the role of the state in shaping variegated financialization by illustrating Chinese characteristics. While previous studies have argued the dominance of the state in facilitating financialization in China (Pan et al., Citation2020; Petry, Citation2020; Wang, Citation2015), we emphasize the changing roles of the state and intrastate divergence in the process of financialization. The previous routine extra-budgetary financing mechanism originated from the mismatch between local responsibilities and fiscal power and existed to promote local growth (Wang et al., Citation2011; Wu, Citation2018). However, the exceptional growth of chengtou and local debt after the GFC was not a consequence of promoting growth, but to cope with the crisis (He et al., Citation2020). Confronting recession after the GFC, chengtou were effective tools for the state to solve fiscal insufficiency and stimulate the economy. This echoes ‘state entrepreneurialism’ in that market instruments are mobilized for state goals (Wu, Citation2018). To deal with local debt problems, strict measures by the central state after 2014 have also demonstrated that the state still maintains strong control over the financial market and local borrowing. Moreover, we also emphasize intrastate divergence in the financialization of urban development. While the central state restricted the financial function of chengtou for some time, local states have consistently supported chengtou to maintain their financial function for local development. The divergence between the central state and local states also reflects the inconsistency within the Chinese state (Howell, Citation2006; Li et al., Citation2014), which is pronounced in the financialization of urban development.

Second, as we illustrate the changing roles of the state in the financialization of urban development, we advance the understanding of the broader state–finance relationship. The development of chengtou not only demonstrates state-led financialization, but shows how the central state speeded up and restricted financialization at different stages. This finding inspires studies on state-led financialization, such as in Italy and Turkey, to make a longitudinal observation. It also contributes to further studies on ‘de-financialization’ or re-regulating financialization (Karwowski, Citation2019; Lapavitsas, Citation2013).

Third, we contribute to the understanding of how the state is affected during the process of financialization. In Western studies, the power of the state has been curtailed by the financial market when utilizing financial intermediaries, instruments and products (Guironnet et al., Citation2016; Karwowski, Citation2019; Peck & Whiteside, Citation2016). But in studies on China, scholars argue that the development of the financial market is a means to consolidate the legitimacy of the state (Pan et al., Citation2020; Petry, Citation2020; Wang, Citation2015; Wu et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, insufficient attention has been paid to explain how different state actors are affected and reacted in the process of financialization. Based on the cases of chengtou, we find that although the Chinese state may retain control over the financial market, financialization reshapes relationships within the state and may lead to further intrastate divergence in two aspects. First, although the central state advocated local government bonds rather than chengtou borrowing after 2014, local states especially lower level governments still favour chengtou. Second, local states in developed regions still manage to maintain and transform chengtou to fit for central regulations and the financial market. However, in less-developed regions, local states have become conservative to the financial market and increasingly reliant on the central bailout. In this sense, the Chinese state is not shaped by the financial market as described in Western studies, but demonstrates the alternative proposition that the process of financialization deepens the degree of divergence and inconsistency within the state.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Aalbers, M. B. (2015). The potential for financialization. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(2), 214–219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820615588158

- Aalbers, M. B. (2017). The variegated financialization of housing. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 542–554. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12522

- Aalbers, M. B. (2019). Financial geography III: The financialization of the city. Progress in Human Geography, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853922

- Ambrose, B. W., Deng, Y., & Wu, J. (2015). Understanding the risk of China’s local government debts and its linkage with property markets. SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2557031

- Ang, A., Bai, J., & Zhou, H. (2015). The great wall of debt: The cross section of Chinese local government credit spreads. SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2603022

- Ashton, P., Doussard, M., & Weber, R. (2016). Reconstituting the state: City powers and exposures in Chicago’s infrastructure leases. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1384–1400. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014532962

- Bai, C.-E., Hsieh, C.-T., & Song, Z. M. (2016). The long shadow of a fiscal expansion (Paper No. 22801). National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

- Belotti, E., & Arbaci, S. (2020). From right to good, and to asset: The state-led financialisation of the social rented housing in Italy. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420941517

- CBRC. (2011). Supervision of local government financing vehicles (CBRC No. 91). http://www.cbrc.gov.cn/chinese/newIndex.html

- Chen, Z., He, Z., & Liu, C. (2020). The financing of local government in China: Stimulus loan wanes and shadow banking waxes. Journal of Financial Economics. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2019.07.009

- Chien, S.-S. (2013). New local state power through administrative restructuring – A case study of post-Mao China county-level urban entrepreneurialism in Kunshan. Geoforum, 46, 103–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.12.015

- Christophers, B. (2015). The limits to financialization. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(2), 183–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820615588153

- Christophers, B. (2019). Putting financialisation in its financial context: Transformations in local government-led urban development in post-financial crisis England. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 571–586. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12305.

- Deng, C. (2019). ‘There’s no money right now’: China’s building boom runs into a great wall of debt. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/theres-no-money-right-now-chinas-building-boom-runs-into-a-great-wall-of-debt-11551267002

- Fan, G., & Lv, Y. (2012). Fiscal prudence and growth sustainability: An analysis of China’s public debts. Asian Economic Policy Review, 7(2), 202–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-3131.2012.01234.x

- Feng, Y., Wu, F., & Zhang, F. (2020). The development of local government financial vehicles in China: A case study of Jiaxing Chengtou. Land Use Policy, Art. 104793. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104793

- Fernandez, R., & Aalbers, M. B. (2019). Housing financialization in the Global South: In search of a comparative framework. Housing Policy Debate, 30(4), 680–701. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2019.1681491

- Fields, D. (2017). Urban struggles with financialization. Geography Compass, 11(11), e12334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12334

- Gotham, K. F. (2016). Re-anchoring capital in disaster-devastated spaces: Financialisation and the Gulf Opportunity (GO) Zone programme. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1362–1383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014548117

- Guironnet, A., Attuyer, K., & Halbert, L. (2016). Building cities on financial assets: The financialisation of property markets and its implications for city governments in the Paris city-region. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1442–1464. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015576474

- Halbert, L., & Attuyer, K. (2016). Introduction: The financialisation of urban production: Conditions, mediations and transformations. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1347–1361. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016635420

- Harvey, D. (1978). The urban process under capitalism: A framework for analysis. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 2(1–3), 101–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.1978.tb00738.x

- He, S., Zhang, M., & Wei, Z. (2020). The state project of crisis management: China’s shantytown redevelopment schemes under state-led financialization. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(3), 632–653. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19882427

- Howell, J. (2006). Reflections on the Chinese state. Development and Change, 37(2), 273–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155X.2006.00478.x

- Jessop, B. (2015). The state: Past, present, future. Polity.

- Jiang, Y., & Waley, P. (2018). Shenhong: The anatomy of an urban investment and development company in the context of China’s state corporatist urbanism. Journal of Contemporary China, 27(112), 596–610. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1433580

- Karwowski, E. (2019). Towards (de-)financialisation: The role of the state. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 43(4), 1001–1027. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bez023

- Krippner, G. R. (2005). The financialization of the American economy. Socio-Economic Review, 3(2), 173–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/SER/mwi008

- Lagna, A. (2016). Derivatives and the financialisation of the Italian state. New Political Economy, 21(2), 167–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2015.1079168

- Lapavitsas, C. (2013). The financialization of capitalism: ‘Profiting without producing’. City, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2013.853865

- Lapavitsas, C., & Powell, J. (2013). Financialisation varied: A comparative analysis of advanced economies. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 6(3), 359–379. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rst019

- Li, J., & Chiu, L. H. R. (2018). Urban investment and development corporations, new town development and China’s local state restructuring – The case of Songjiang new town, Shanghai. Urban Geography, 39(5), 687–705. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1382308

- Li, L., & Xiao, Y. (2020). Capital accumulation and urban land development in China: (Re)making Expo Park in Shanghai. Land Use Policy, Art. 104472. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104472

- Li, Z., Xu, J., & Yeh, A. G. O. (2014). State rescaling and the making of city-regions in the Pearl River Delta, China. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 32(1), 129–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/c11328

- Ministry of Finance (MOF). (2017). Dealing with the problems of illegal debt guarantee in Guizhou province and strengthening financial and economic discipline. http://yss.mof.gov.cn/zhuantilanmu/dfzgl/ccwz/201712/t20171222_2787142.html

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). (2008). Promoting corporate bond market and simplifying the issuance approval process (NDRC No. 7). https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xzzq/200801/t20080104_1204541.html

- O’Brien, P., O’Neill, P., & Pike, A. (2019). Funding, financing and governing urban infrastructures. Urban Studies, 56(7), 1291–1303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018824014

- Pan, F., Zhang, F., & Wu, F. (2020). State-led financialization in China: The case of the government-guided investment fund. The China Quarterly, 1–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741020000880

- Pan, F., Zhang, F., Zhu, S., & Wójcik, D. (2017). Developing by borrowing? Inter-jurisdictional competition, land finance and local debt accumulation in China. Urban Studies, 54(4), 897–916. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015624838

- PBC. (2009). Guidelines on further restructuring of credit system and promoting steady and rapid economic development (PBC No. 92). http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2009/content_1336375.htm

- Peck, J., & Whiteside, H. (2016). Financializing Detroit. Economic Geography, 92(3), 235–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1116369

- Peck, J., & Zhang, J. (2013). A variety of capitalism … with Chinese characteristics? Journal of Economic Geography, 13(3), 357–396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbs058

- Petry, J. (2020). Financialization with Chinese characteristics? Exchanges, control and capital markets in authoritarian capitalism. Economy and Society, 49(2), 213–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2020.1718913

- Pike, A., O’Brien, P., Strickland, T., Thrower, G., & Tomaney, J. (2019). Financialising city statecraft and infrastructure. Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788118958.

- Pike, A., & Pollard, J. (2010). Economic geographies of financialization. Economic Geography, 86(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01057.x

- Rethel, L., & Thurbon, E. (2020). Introduction: Finance, development and the state in East Asia. New Political Economy, 25(3), 315–319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1562435

- Shanghai Brilliance Credit Rating. (2020). Credit rating report for the first enterprise bond in 2020 of SMI. https://www.chinabond.com.cn/Channel/21280

- Shen, J., Luo, X., & Wu, F. (2020). Assembling mega-urban projects through state-guided governance innovation: The development of Lingang in Shanghai assembling mega-urban projects. Regional Studies. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1762853

- Shen, J., & Wu, F. (2017). The suburb as a space of capital accumulation: The development of new towns in Shanghai, China. Antipode, 49(3), 761–780. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12302

- State Council. (2008). Providing financial support for economic development (State Council No. 126). http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2008-11/10/content_1143831.htm

- State Council. (2014). Strengthening the management of local government debts (State Council No. 43). http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-10/02/content_9111.htm

- Su, X. (2015). Urban entrepreneurialism and the commodification of heritage in China. Urban Studies, 52(15), 2874–2889. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014528998

- Tsai, K. S. (2015). The political economy of state capitalism and shadow banking in China. Issues and Studies, 51, 55–97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2607793

- Tsui, K. Y. (2011). China’s infrastructure investment boom and local debt crisis. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 52(5), 686–711. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2747/1539-7216.52.5.686

- Van Loon, J., Oosterlynck, S., & Aalbers, M. B. (2018). Governing urban development in the low countries: From managerialism to entrepreneurialism and financialization. European Urban and Regional Studies, 1–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776418798673

- Waldron, R. (2018). Capitalizing on the state: The political economy of real estate investment trusts and the ‘resolution’ of the crisis. Geoforum, 90, 206–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.014

- Wang, D., Zhang, L., Zhang, Z., & Zhao, S. X. (2011). Urban infrastructure financing in reform-era China. Urban Studies, 48(14), 2975–2998. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010392079

- Wang, Y. (2015). The rise of the ‘shareholding state’: Financialization of economic management in China. Socio-Economic Review, 13(3), 603–625. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwv016

- Weber, R. (2010). Selling city futures: The financialization of urban redevelopment policy. Economic Geography, 86(3), 251–274. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2010.01077.x

- Wong, C. P. W. (2013). Paying for urbanization in China. In R. W. Bahl, J. F. Linn, & D. L. Wetzel (Eds.), Financing metropolitan governments in developing countries (pp. 273–308). Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- Wu, F. (2018). Planning centrality, market instruments: Governing Chinese urban transformation under state entrepreneurialism. Urban Studies, 55(7), 1383–1399. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017721828

- Wu, F. (2019). Land financialisation and the financing of urban development in China. Land Use Policy, Art. 104412. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104412

- Wu, F., Chen, J., Pan, F., Gallent, N., & Zhang, F. (2020). Assetization: The Chinese path to housing financialization. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 110(5), 1483–1499. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1715195

- Wu, W. (1999). Reforming China’s institutional environment for urban infrastructure provision. Urban Studies, 36(13), 2263–2282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098992412

- Yang, D. Y.-R., & Wang, H.-K. (2008). Dilemmas of local governance under the development zone fever in China: A case study of the Suzhou region. Urban Studies, 45(5–6), 1037–1054. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098008089852

- Yeşilbağ, M. (2019). The state-orchestrated financialization of housing in Turkey. Housing Policy Debate, 30(4), 533–558. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2019.1670715

- Yrigoy, I. (2018). State-led financial regulation and representations of spatial fixity: The example of the Spanish real estate sector. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(4), 594–611. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12650

- Zhang, Y. (2018). Grabbing land for equitable development? Reengineering land dispossession through securitising land development rights in Chongqing. Antipode, 50(4), 1120–1140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12390