ABSTRACT

The concentration of economic growth into large metropolises is widely documented across Europe. Yet, planning of this growth at the strategic metropolitan scale shows significant variation. This paper documents the evolution of Opportunity Areas within Greater London. Through statistical and documentary analysis, and participant observation, we reveal how they have been repurposed from a tool employed to facilitate brownfield regeneration to one that sustains growth through brokering relationships, enhancing land value and capturing it. The paper argues that the cumulative impact of these ‘soft spaces’ of planning represents a fundamental change in the nature of strategic planning for city-regions.

INTRODUCTION

Spatial planning at the city-regional and metropolitan scale is an increasingly complex and multilayered activity. Operating in the context of an urban-focused competitive growth agenda (Scott & Storper, Citation2015), it has been appropriated as a tool to accommodate and sustain economic growth. The nature and impact of this growth has been the subject of much debate and critique as it is considered to contribute to growing inter-regional (Crouch & Le Galès, Citation2012) and intra-regional inequalities (Pike et al., Citation2007). As growth is increasingly consolidated into major metropolitan areas, public policy has been enacted in support of this agenda and the role of spatial planning has become contested. On the one hand, it is embraced as a tool to enable territorial cohesion and social inclusion (European Commission, Citation2011), to uphold the public interest and promote sustainable development (TCPA, Citation2018). On the other hand, there is an equally strong view that spatial planning has become a vehicle for delivering private sector housing and economic growth (TCPA, Citation2018). To facilitate a globally focused growth agenda (Imrie et al., Citation2009), new spatial planning instruments have emerged in many contexts to either fast-track or by-pass the statutory planning process, facilitating urban development. In Ireland, for example, strategic development zones have been deployed to cut through perceived planning bureaucracy and remove barriers to efficient development (Byrne, Citation2016). In Sydney, Australia, a series of collaboration areas have been identified to bring together stakeholders to prepare place strategies to facilitate growth (Greater Sydney Commission, Citation2019). In England, the introduction of Opportunity Areas (OAs) in the 2004 London Plan was part of a broader emphasis in urban policy to channel growth to brownfield locations, remove some of the barriers associated with hard-to-develop sites, and divert ‘growth to the east side of London because that is where both the potential and need is’ (Imrie et al., Citation2009, p. 24). Unlike opportunity zones in the US context, which are a territorially based community investment tool designed to attract capital into low-income areas in return for a tax incentive, OAs in London are quasi-planning tools, rather than fiscal incentives. In the European context, the English case is instructive since the marketization of planning, originally introduced in the 1980s, has significantly intensified under Conservative-led administrations since 2010 (Parker et al., Citation2014). Allmendinger and Haughton (Citation2013) suggests that spatial planning can now be seen as a form of ‘neoliberal spatial governance’ (p. 6).

The purpose of this paper is to document the growth of OAs in London as a spatial and institutional tool, and explore their evolving character, role, governance and politics. OAs are designated growth poles, many of which do not have defined boundaries. They range in scale from 19 ha in constrained Central London locations such as the Tottenham Court Road OA to 3900 ha at the Lee Valley OA, a swathe of largely industrial land spanning the River Lee and part of the London–Stansted–Cambridge–Peterborough growth corridor. We characterize OAs as a new meso-scale institutional fix between the city-regional and local (borough) scale, and as such a new soft space (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009) of planning. Academic attention to date has focused on selected OA case studies, including the high-profile Vauxhall Nine Elms Battersea (VNEB) (Freire Trigo, Citation2020), Kings Cross (Robin, Citation2018) and Old Oak Park Royal (Robinson & Attuyer, Citation2020). In the latter, Robinson and Attuyer bring attention to the role of the state in promoting OAs as spaces of intense development, in order to extract value to meet the costs of infrastructure provision, and the tensions arising as the outcomes directly undermine the wider public interest. However, the evolution of OAs as a policy tool and their growing relevance in terms of the broader spatial development of the city has received relatively limited attention. The impact of this policy initiative is only now becoming apparent as some of the original OAs are nearing completion, and in the context of a significant increase in both their number and distribution in the new London Plan (2021). When viewed over time, the explosion of these soft spaces across the metropolitan region has been accompanied by a shift in their conceptualization and deployment: from a tool of urban regeneration on predominantly brownfield land to a way of delivering efficient and effective redevelopment and sustaining growth. At the city-regional scale, they are conceptualized as a tool to accommodate growth through densification within metropolitan London and one of the only mechanisms through which London governance can affect wider city-regional planning. OAs indicate a shift in the nature and purpose of planning away from direct intervention and regulation towards a focus on brokering relationships at the metropolitan scale to better manage and accommodate growth. This research could therefore offer valuable insights into other planning contexts experiencing similar marketization pressures within largely laissez-faire city-regional planning regimes.

The paper is exploratory and the basis for and outline of a broader research agenda. Following a discussion of OAs as a particular type of soft space of planning, it is structured in three parts. First, we provide an overview of OAs and their introduction in the context of the London Plan. Second, we document and analyse their growth, distribution and character across the metropolitan area. Third, we explore their governance and politics. Our research is based on a descriptive spatial analysis of OA designation and character, thematic documentary analysis of successive London Plans and their revisions since 2004, as well as other relevant documentation including strategic housing and land availability assessments, tall building surveys, OA planning frameworks and the GLA Act 2007. One of the authors has been a member of the London-wide network of community groups, Just Space, serving on the Economy and Planning subgroup since 2014, and attending wider meetings of the Just Space network as an observer. This active participation in London planning issues over many years has provided insight into pockets of resistance to London planning across the city. Two of the authors attended the London Plan Examination in Public (EiP) session focused on OAs (GLA, Citation2019), and notes from participant observation at that meeting have been included as part of the analysis. Planning documents and notes from participant observation were thematically coded and illustrative quotes selected for inclusion.

OPPORTUNITY AREAS AS ‘SOFT SPACES’ OF PLANNING

Although regional government outside Greater London was formally abolished in England under the Localism Act 2011, to some extent ‘regional’ planning still exists in different guises. Although no longer a requirement, strategic planning activity across local authority boundaries is on the rise (Riddell, Citation2019) despite a lack of institutional frameworks to support them. Partly, this is explained by the duty to cooperate across local authority boundaries, enshrined in the Localism Act and described by Allmendinger et al. (Citation2016, p. 42) as ‘a factor in the emergence or strengthening of existing patterns of closer cooperation and partnership between adjacent local authorities’. At the same time, city-regionalism has been growing in importance and extent through central government deal-making at a supra-local but subregional level, illustrative of a particular form of statecraft to incentivize collaboration in practice (Pemberton & Searle, Citation2016). London has a well-established metropolitan governance structure in place since 2004 – the mayor, London Plan and Greater London Assembly – but these governance and administrative structures have not kept pace with the growth of the city-region. Effective city-regional planning is largely dependent on voluntary cooperation or collaboration across local authority boundaries (Brown et al., Citation2018) with OAs providing a mechanism for containing at least some of the growth of London within the metropolitan boundaries.

Allmendinger and Haughton (Citation2010) identify these in-between types of arrangements as evidence for the emergence of ‘soft spaces’ of planning. These may take a variety of forms, but are all inherently based on stakeholder negotiation and characterized by porous or fuzzy boundaries reflecting the predominantly relational rather than necessarily territorial nature of their existence. These soft spaces may be temporary and time-limited connected to the existence of particular projects, but they can also become hardened through discourse and practice (Metzger, Citation2013). Paasi and Zimmerbauer (Citation2016) reflect on the paradoxical nature of these types of in-between spaces of planning, many of which have no institutional foundation. They exist alongside statutory scales of government and hard administrative boundaries but can also challenge the status quo as they become bound up in a ‘discourse of competitiveness [that] re-orchestrates and compels state spaces to the direction of soft (city) regional spaces in the name of stimulating economic growth’ (Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2020, p. 776) and spatial restructuring. Faludi (Citation2010, p. 23) contrasts hard planning with the soft planning required to make soft spaces work; the latter relying on the joint formulation of strategies where ‘the only investment needed is the will to cooperate and to continue to cooperate in settings that evolve over time’.

The attention in the literature on soft spaces of planning at the city-regional and metropolitan level is unsurprising given the growing significance in the academic and policy fields to the power of cities and particularly metropolitan areas in driving national economic growth (Glaeser, Citation2011; Scott, Citation2008). In the UK context, the creation of new metro-regions is couched in discourses related to inter-urban global competitiveness and enabling growth along particular development trajectories (Pike et al., Citation2019). The creation of new practices and spaces of planning is based on a ‘growth lifts all boats’ approach to local and regional development, although there is growing evidence that this approach exacerbates existing spatial inequalities (Moore-Cherry et al., Citation2021). This conundrum is exemplified across the European Union where there is widespread recognition of growing regional divergence and a need for increased territorial cohesion, at the same time as sustaining the most dynamic metropolitan regions in order to ensure Europe’s global competitiveness (Iammarino et al., Citation2017). While contemporary spatial planning has a crucial role to play in harnessing and steering growth, it is increasingly appropriated in the service of economic growth and the enabling of (private sector) development (Lennon et al., Citation2018) as local authorities face increased pressure from both global competition and reduced state funding (Hulst & van Montfort, Citation2007). Zimmerbauer and Paasi (Citation2020, p. 776) highlight the role of soft spaces within this broader political economic context as ‘both tools and engines for increasing competitiveness, and eventually for economic success’.

Acknowledging the potential for inequalities within city-regions, Henderson (Citation2018) calls for attention to also focus on the sub-metropolitan scale arguing that not all areas within a city-region or metropolitan area are necessarily moving in the same direction: some parts of a metro region get turbo-charged and others remain less embedded, for a variety of reasons including institutional variation across territorial administrative boundaries. This chimes with recent work on project-based urbanism (Raco, Citation2014; Robin, Citation2018), a form of soft space assembled on an ad-hoc basis ‘to displace politics away from the democratic arrangements of statutory local government planning in order to more easily facilitate growth and neutralize opposition’ (Allmendinger et al., Citation2016, p. 41). The implications of this type of projectification can be increasing levels of exclusion and intra-urban inequality. Robin (Citation2018) and Robinson and Attuyer (Citation2020) have drawn particular attention to this in the context of the Kings Cross and Old Oak Park Royal OAs highlighting the territorial, social and economic impacts on a variety of stakeholders. However, significant variability exists between OAs across a number of dimensions and this complexity demands a more holistic analysis. A broader examination of the rolling out of OAs in London since 2004, included in this paper, provides a chance to reflect on the implications for metropolitan and wider city-regional planning and governance of replacing traditional, technocratic planning with the widespread use of soft planning tools, which embed a growth-led logic and are heavily reliant on brokering relationships.

THE RISE AND RISE OF OPPORTUNITY AREAS IN LONDON PLANNING

A rapidly changing city, London’s population is currently just under 9 million and has been growing from 6.7 million in 1991 to a projected total of 10.8 million by 2041 (GLA, Citation2017). Over the last five decades, the economic and demographic structure of the city has been radically transformed as London has asserted itself in the global economy. In spatial terms, employment is increasingly clustered in inner London (GLA, Citation2016). A key challenge of this agglomeration economy is mobility and accessibility. With Transport for London’s (TfL) funding model threatened by withdrawal of central government grants, this has resulted in greater reliance on high density development to subsidize transport infrastructure (Pike et al., Citation2019). Combined with falling revenue from core activities, this development model is also at risk from the structural changes to cities that could materialize as a result of the 2020 pandemic. At the same time, London also faces a significant housing crisis both in terms of supply and affordability (Bowie, Citation2017) and the city has seen widening inequalities including an estimated increase in poverty of 80% between 1980 and 2010 (Dorling et al., Citation2007; Office for National Statistics (ONS), Citation2011).

These challenges are at the heart of the new London Plan (2021), a metropolitan planning document coordinated by the Greater London Authority (GLA), in partnership with 33 local authorities, which seeks to tackle growing inequalities and facilitate ‘good growth’. Arguably, the new London Plan is just the latest in a series of interventions in and actions upon the physical space of the city (Imrie et al., Citation2009) that, over the last thirty years, has followed a global ‘growth first’ (Cochrane, Citation2007) logic. The metropolitan area – Greater London – is led by a directly elected mayor of London that has been characterized as one of strategic enabling rather than strategic governing (Tewdwr-Jones, Citation2009) given its limited powers compared with other contexts such as New York or Paris. While the London Plan was originally a key instrument in the coordination of spatial planning through the provision of a guiding framework for local borough plans, increasingly it has become more focused on economic development planning, particularly with the extension of mayoral powers in the Greater London Authority Act 2007.

A cursory reading of the different iterations of the London Plan highlights the growing relevance of OAs in the making of London. The first London Plan in 2004 identified 28 OAs, and this has risen to 48 in the new London Plan. This growth has taken place in the absence of any formal evaluation (to date) of the delivery, impact and outcomes of the OA policy and tool. There is no clear justification for the growth of OAs or the resultant prominence of this strategic planning tool. Different iterations have loosely justified the creation of new OAs to meet the growing needs and demands of London’s population. The new London Plan classifies OAs, for the first time, according to their delivery progress as: nascent, ready to grow, underway, maturing or mature. Yet, 15 years on from their designation, none of the original OAs has been fully completed (considered ‘mature’) with the majority still ‘nascent’ or ‘ready to grow’ while fewer than half are ‘underway’ or ‘maturing’.

Over time, the purpose of OAs has shifted. At the beginning of the 2000s, London and the South East of England were already experiencing an incipient housing affordability crisis. The allocation of land for large-scale residential-led projects became one of the key strategies to meet the needs of the growing population in this part of the country (e.g., HM Treasury, Citation2004; Urban Task Force, Citation1999). In this context, the first OAs were described as ‘major brownfield sites with capacity for new development and places with potential for significant increases in density’ (GLA, Citation2004, para. 2.8, emphasis added). This was consistent with a planning approach that had deliberately attempted to divert growth to the east of the city, to the Olympic Park in Newham, and to vacant or under-utilized industrial locations in other parts of East London. In this way, OAs were conceived as a tool to highlight and support locations where regeneration activity was to be focused. A similar emphasis is evident in the 2011 London Plan, with OAs defined as ‘the capital’s major reservoir of brownfield land with significant capacity to accommodate new housing, commercial and other development’ (GLA, Citation2011, para. 2.58). This deliberate spatial selectivity and the strategic identification of potentially winning locations was characteristic of government interventions to concentrate regeneration that would sustain wider metropolitan, city-regional and national economic growth and, through trickle-down economics, spread the benefits of development to disadvantaged local communities (Imrie et al., Citation2009).

The new London Plan also includes OAs, but their definition already indicates that there has been a significant shift in their conception. In the new Plan, ‘Opportunity Areas are identified as significant locations with development capacity to accommodate new housing, commercial development and infrastructure (of all types) … ’ (GLA, Citation2021, para. 2.1.1, emphasis added). The attention to brownfield regeneration is no longer central. Instead, OAs have been reconceptualized as a planning tool to direct and coordinate growth and development around new infrastructure provision in a wide variety of locations. These new OAs serve broader political and strategic purposes too, as the new London Plan indicates, such as addressing the housing crisis and the dispersion of concentration of jobs. Arguably they are also an attempt to contain the growth of London within the metropolitan area and thus meet other political and environmental objectives. In this regard, OAs are considered strategically important for delivering housing on large sites, with the potential to accommodate almost 70% of London’s 10-year housing target for large sites (GLA, Citation2017, p. 2). Overall, the 48 proposed OAs have capacity to deliver up to 496,100–497,100 new homes and 728,600–735,000 new jobs across the metropolitan area over the long-term (GLA, Citation2021, tab. 2.1).

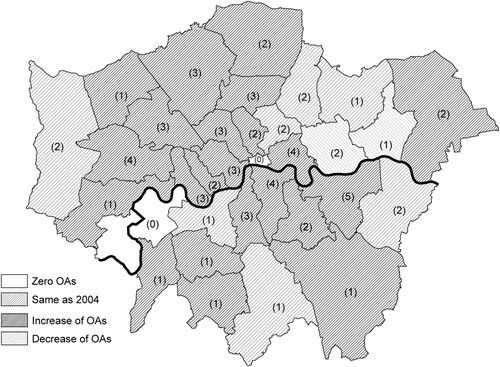

The spatial distribution of the 48 OAs in the new London Plan reveals a different logic behind their designation to that of the original 28 OAs of the London Plan 2004. As illustrates, most London boroughs have seen an increase in numbers of OAs, but their distribution is no longer skewed towards East London. Moreover, all but two local authority areas (Richmond and the City of London) contain at least one OA, compared with only nine local authorities in 2004. This geography of OAs illustrates the conceptual shift in their role and purpose since 2004. Only 10 of the original 28 OAs have remained unchanged over the past 15 years, while the boundaries of many others have become more expansive, illustrating the fluid nature of OAs and the institutionalization and de-institutionalization of these soft spaces of planning (Paasi & Metzger, Citation2017; Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2020).

Figure 1. Distribution of the 48 Opportunity Areas (OAs) in the new London Plan.

Note: Fourteen OAs cross local borough boundaries, but they have been counted in each of the boroughs they occupy.

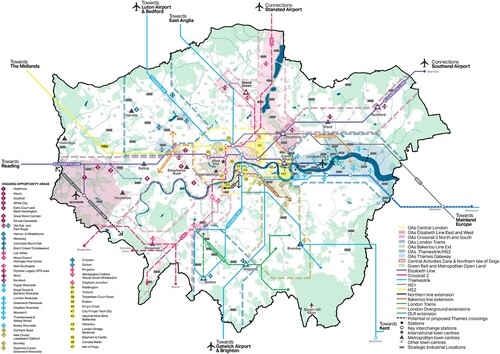

OAs are still described as areas that ‘have the potential to deliver a substantial amount of the new homes and jobs that London needs’ (GAL, Citation2021, para. 2.0.4). However, their designation is no longer linked to surplus land but to ‘growth corridors’ (para. 2.0.4) that crisscross the London metropolitan area along existing and anticipated transport corridors (). These transport corridors matter from a connectivity point of view, but also because they unlock ‘new areas for development, enable the delivery of additional homes and jobs, facilitating higher densities’ (para. 2.1.6). In this regard, OAs have become an important mechanism for land value capture associated with the provision of new transport infrastructure (Curtis et al., Citation2017; Robinson & Attuyer, Citation2020) and are thus critical to achieving housing and employment objectives as well as sustaining mobility. It is evident in the new London Plan that the spatial distribution of OAs is no longer tied to areas in need of regeneration. Instead, it is strongly determined by the planning of transport infrastructure and the need to broker diverse sets of relationships to deliver on these strategic goals. This is particularly illustrated in chapter 2 and table 2.1 which organize the discussion and listing of OAs on the basis of existing or future transport lines.

Figure 2. Key diagram of the new London Plan.

Note: Shown, among other things, is the distribution of its 48 Opportunity Areas (OAs), that is, the numbered diamond shapes, along its growth (or transport) corridors, that is, the dashed and continuous coloured lines. The diagram contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v 3.0.

Source: GLA (Citation2021, p. 28).

DEVELOPMENT CAPACITY AND CHARACTER OF OPPORTUNITY AREAS

One aspect of continuity has been the minimum expected development capacity in each OA – at least 5000 new jobs and 2500 homes – that has remained unaltered since the concept was first introduced. However, just as their scale and scope varies, so too do the indicative development capacities across the OAs. They have changed over time informed by updates to the evidence base underpinning the London Plan: the London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA), which directly informs housing capacity, and the London Employment Sites Database that informs estimated numbers of new jobs.

The variation between OAs in terms of development capacities is notable. In the new London Plan, the Tottenham Court Road OA is expected to provide 300 homes, while the Olympic Legacy OA is expected to provide 39,000 homes. In other words, the latter has a residential development capacity that is 130 times larger than the former. The analysis finds a similar situation when looking at the provision of jobs. At the lowest end of the spectrum, the Ilford OA – an East London suburban town centre – has an expected capacity of 500 jobs, while at the opposite end, the Isle of Dogs OA – the location of the Canary Wharf financial district – has a target of 110,000 jobs (220 times the target in Ilford). These variations could be linked to the different sizes of OAs, which range from 19 to 3900 ha. However, our comparative analysis shows that even OAs of similar sizes (e.g., Ilford and Euston) () have very different development capacities, jobs and homes targets.

Table 1. Comparison between the Ilford and Euston Opportunity Areas (OAs) in the new London Plan.

Key to these differences is both the availability of developable large sites in the OA, and the likely densities that are deemed acceptable in particular locations. In calculating development capacities of OAs, the GLA is able to make more realistic assumptions of achievable density based on past delivery trends in suburban, urban and central locations (GLA, Citation2021, p. 90). However, the new London Plan (and all the previous iterations) lack a clear connection between the indicative homes and jobs targets and the qualitative nature of places envisioned. Our analysis highlights the difficulty for existing communities and other interested parties to understand the anticipated spatial impacts of these strategic interventions. This is not unusual in the context of new soft spaces of planning which are ‘essentially pragmatic exercises in ensuring plans are produced in effective ways rather than visionary exercises in place-making’ (Allmendinger et al., Citation2016, p. 39). Nevertheless, it raises questions about the transparency and governance of such new spaces as their public scrutiny is thwarted by their lack of spatial detail, a point we return to in the next section.

When comparing the 2016 and 2021 iterations of the London Plan (), our analysis shows that the 38 OAs included in both plans have seen substantial increases in development capacities for jobs (+17.32%) and homes (+31.73%), transport improvements despite their boundaries not being expanded. An explanation for this remarkable increased capacity can be found in the new London Plan, which explains that ‘transport improvements lead to increased delivery of homes and jobs’ (GLA, Citation2021, para. 2.1.11). In this regard, transport corridors seem to have given OAs a limitless (or at least, a spatially unbounded) capacity for growth, with implications for the densities being sought in these areas. The imprecise location of the 10 new OAs in the new London Plan illustrates this ‘spatially unbounded’ logic even further and highlights the potential and dangers of these new spaces of planning. While the tool facilitates a more strategic and multilayered process of development, it dilutes appreciation of the (necessary) limits of a place to support growth and thus seems inconsistent with the rhetoric of sustainability that permeates the plans.

Table 2. Increased development capacity within Opportunity Areas (OAs) of the new London Plan 2021 compared with that of the London Plan 2016.

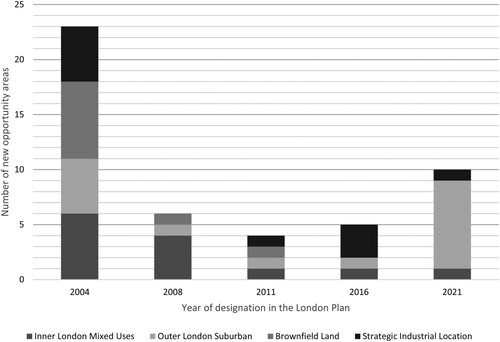

Finally, our analysis turns to the more qualitative dimension of the character of the places designated as OAs. In order to make judgments about character, we have consulted information available in the different iterations of the London Plan; the information about OAs available on the GLA website; and the authors’ own knowledge of many of these areas. The analysis has identified four typologies of OAs that we identify as: Inner London mixed use; Outer London suburban; brownfield land; and strategic industrial locations. Acknowledging the reductivist nature of this approach, the purpose of this characterization is to assess any noticeable patterns in the changing character of newly designated OAs and to provide further evidence for a shift from an initial focus on brownfield regeneration to a new emphasis on sustaining ‘growth first’.

, based on our analysis, reveals how the dominant character of OAs has shifted considerably over time. One observation is the limited relevance that brownfield land now plays in the strategic planning of London. Only nine of the 48 OAs can be characterized as brownfield land, with seven of them dating back to 2004. Since then, only two OAs – Euston, around the railway station, and Kensal Canalside, in North Kensington – could be broadly categorized in this way. The majority of the newly designated OAs in the new London Plan comprise Outer London suburban places. The delivery of transport infrastructure emerges as the key factor behind this trend, both in terms of spatial distribution and development capacity. The implications of this for the governance and politics of these new spaces of planning is significant, an issue that we now explore.

THE GOVERNANCE AND POLITICS OF OPPORTUNITY AREAS

The introduction of OAs in the first London Plan provided for softer, more informal spaces of planning, to enable project-led development and enhanced responsiveness to the reality of investment dynamics and the financialization of housing and infrastructure. OAs remain a prominent feature in the London Plan, but there is variation in their governance arrangements and in how they relate to statutory planning. They are part of an already complex set of institutional assemblages that exist across interlocking spatial scales in the capital region. Mayoral development corporations (MDCs) have been set up in two OAs to date: the London Legacy (Olympic) site and Old Oak Park Royal – where Crossrail and the proposed new High-Speed Rail 2 (HS2) line meet. An MDC is a functional body of the GLA, with planning powers, and it is the largest landowner in the area. In other locations, OAs overlap with enterprise zones, which offer tax incentives for business investment, such as at the Royal Docks and Beckton Riverside OA (London Borough of Newham). Across the spectrum of OAs, it is not clear what their status is in planning terms. In 23 OAs, the GLA – in partnership with local authorities and other key stakeholders – has prepared an opportunity area planning framework (OAPF) to guide development. However, these are not compulsory and lack formal statutory status. In other OAs, councils have prepared formal planning documents – area action plans (AAPs) or supplementary planning documents (SPDs) – but there is no obligation on local authorities to do so. The upshot of this is that a variety of localities are given OA status by the metropolitan governance structures, with indicative minimum targets for homes and jobs, but there is no guarantee of a formal plan being prepared at the local level which goes through the normal processes of consultation and examination by a planning inspector. This is significant, since in the absence of local planning frameworks for an OA, the London Plan on its own has development plan status. The precise status of OAs and their relationship to other elements of the formal planning system and the role and influence of different stakeholders remains unexplained. There is no formal guidance on how they should operate, characteristic of their fuzziness and typical of new soft spaces of planning. In some senses, OAs are less material and more symbolic tools, and perhaps more indicative of planning tolerances or limits.

For the GLA itself, OAs are understood as a tool to fast-track planning. At the EiP on the new London Plan, GLA planning officers contested the claim that there was inadequate consultation on OAs. Since their designation and broad development capacities had been through scrutiny at previous London Plan EiPs, they ‘are not developed behind closed doors. Everyone has had the opportunity to comment on them’. GLA planning officers resisted any notion that boroughs should be required to develop statutory planning documents for OAs since ‘we need the flexibility to get development in place in a timely manner’, suggesting that OAs are, in fact, a malleable, amorphous tool that can justify new planning practices. GLA officers even see a potential role for the private sector in preparing OAPFs in the future: ‘It could be done in principle but would need to follow the due process and be prepared in partnership with the borough and Mayor.’ Thus, OAs have emerged as an increasingly powerful, utilized, but informal planning tool, used to broker high level strategic collaboration between stakeholders and operate outside the sphere of normal planning policy and practice. Whether this brokerage role expedites planning processes to the benefit of the public interest is questioned by Robinson and Attuyer (Citation2020), who point to the tensions inherent in the blurring of public and private sector roles and their interests in urban development. Across the city, therefore, the cumulative impact of these brokering dynamics could result in a very different city-region landscape than that envisioned in the London Plan.

While the MDC’s have been critical in some OAs, the role and influence of TfL – another arm of mayoral power – has been crucial more generally. This is partly a direct result of TfL’s landownership of under-utilized, centrally located land dominated by rail infrastructure. A less direct and growing influence is through the funding of future transport infrastructure in the capital. This has become increasingly reliant on speculative activity through the capturing of land value uplift associated with development. As revealed in the previous section, the new OAs identified in the new London Plan are associated primarily with planned strategic transport infrastructure. In recent years, TfL’s funding model has been overhauled as central Government funding has been gradually withdrawn since 2013 so that TfL’s budget is now entirely dependent on other forms of revenue generation. Although the government has offset the loss of some of this direct funding with the retention of London business rates, TfL is required ‘to develop new and innovative ways to supplement the revenue from transport operations’, which includes using ‘our land for property development’ (TfL, Citation2019). OA designations allow TfL to use their property portfolio to generate growth and development, increasing future predicted patronage and underpinning the business case for investment in transport infrastructure. There is some circularity to this, called into question by developers represented at the EiP, who did not agree with paying for infrastructure through planning gain mechanisms without any certainty that the infrastructure would come forward within a reasonable timescale. The ongoing delays to Crossrail 1 (also known as the Elizabeth Line) were cited as grounds for their scepticism. This points to an emerging interdependency between different public and private sector actors. The private sector is dependent on TfL for the delivery of the infrastructure to support new development, and on the boroughs and the GLA to facilitate a pro-development planning environment. In turn, TfL and the GLA are dependent on the private sector to deliver the housing and development that underpins and justifies this broader investment.

For local authorities, OAs provide a mechanism for bringing a range of high-level stakeholders (e.g., TfL, developers) around the table that might otherwise be difficult to engage. Only a small handful of London boroughs submitted representations to the EiP, suggesting there is limited institutional opposition to the OA model. The Royal Borough of Kingston, in outer London, had its first OA – Kingston town centre – designated in the new London Plan, and attended the EiP, commenting that they ‘see the Opportunity Area as bringing the support of the GLA to the table to help bring necessary infrastructure to support the delivery of homes and jobs that we need to deliver anyway’. Outer London boroughs collectively saw their housing targets double (since 2016) in the consultation draft of the new London Plan. Much of this new housing was planned to be delivered on ‘small sites’, and there was significant local political opposition to this, resulting in the inspector recommending to the mayor that outer London targets be reduced (The Planning Inspectorate, Citation2019). Without capacity on small sites, outer London boroughs are more reliant on OA designation and investment in associated transport infrastructure that such designation brings.Footnote1 Yet other boroughs – such as Enfield in North London – drew attention to the problems of relying on long-term proposals for forthcoming transport infrastructure to unlock growth and deliver jobs and homes. In their written representation to the EiP, they explained that a combination of the restrictive policies on employment land, ‘the prolongation of the Crossrail 2 business case process and a lack of transport corridor-based planning policy frameworks and delivery mechanisms would … significantly hinder the delivery of development’. Evident here is the level of dependency between the boroughs and the GLA; the boroughs rely on mayoral support to secure infrastructure and bring development partners together, and the GLA relies on boroughs and a smooth political process to deliver on the housing targets. However, tensions also arise, particularly around delivering social and community infrastructure, where the prioritization of transport infrastructure and affordable housing can be at the expense of other local provision.

This issue was raised by the London Forum of Civic and Amenity Societies which identified a ‘democratic deficit’ in the preparation of OAPFs to date, because they had been subject to ‘inadequate community consultation’. In the case of the VNEB OA, there was a perception amongst community groups that ‘there was a collusion between the OA team at the GLA and gung-ho local development partners’, which had resulted in the renegotiation of maximum building heights in the area from 150 to 200 m. Just Space, a London-wide network of community groups and activists, suggested the process ‘doesn’t take into account the views of communities or borough character studies’ and that ‘it is done behind closed doors, in secret, no one knows about it’. The GLA team responded to these criticisms by emphasizing that under the new mayor, this is ‘a new OAPF approach, a new plan, a new team and new methods’ and that, as part of the preparation of an OAPF, they would take a ‘finer grain approach’, integrating character studies, doing ‘more detailed capacity assessments working with the boroughs and consulting with local communities’. Objectors were, however, sceptical that the process would be any different to the past.

Participants at the EiP voiced concerns about the scale of development proposed in OAs and the impact of this both on communities and to neighbourhood character and sense of place. For example, the Camden Civic Society commented on the fact that towers were being built on green spaces in the residential neighbourhood of Somerstown in Central London, between Euston and Kings Cross stations: ‘We’re really concerned about new street canyons being created and being trapped in poor air quality.’ Several times during the course of the EiP, the model of growth dependency in OAs in order to fund transport infrastructure was questioned on the basis that the density required for development to be viable is likely to have a disproportionate impact on lower socioeconomic groups. A Just Space representative projected that, ‘you’ll end up paying for the infrastructure with poor housing outcomes … Opportunity Areas are impacting on the poorest communities’.

The use of the word ‘opportunity’ has been divisive, with a perception amongst activists and campaigners that the opportunity rests solely with the private sector with few positive impacts or outcomes for the communities that currently reside in or work in areas designated as OAs. Grassroots resistance is visibly strong and growing across a number of OAs in London. Naturally, there has been resistance to private sector-led growth and development before the term opportunity area was used. For example, there have been longstanding campaigns in Waterloo and Kings Cross, with the formation of the Waterloo Community Development Group in 1972 and the Kings Cross Railway Lands Group in 1987. Wider impacts include the development pressure felt by numerous communities that fall outside a designated OA as it becomes established. Resident and business campaigners in Camley Street to the north of Kings Cross, whose housing and industrial estates are under threat of development, are concerned as development opportunities are sought on the fringes of the OA. This is likely to become a more widespread concern as more OAs move from Nascent to Underway status.

This section on the governance and politics of OAs, explored how they are perceived by the city-regional governing bodies (GLA, TfL), the local boroughs and communities. It revealed a strong and growing interdependency between private, public and community actors and ‘lock-in’ to a development model that is predicated on growth first, trickle-down economics, and is an inherently precarious way to deliver basic infrastructure and community services. Local communities and the local authorities representing them are dependent on the resources and partners that the GLA brings, but at the same time are sceptical that adequate infrastructure will be forthcoming to support growth. They are increasingly ‘pushing back’, reluctant to accept the dependence on growth that this funding model entails and pushing for greater democratic accountability of the process that is unravelling. Nonetheless, the radical change demanded is unlikely to happen given that successive institutions of London government and waves of metropolitan policies over many decades have been about opening up opportunity as a way of balancing and redirecting growth rather than redistributing wealth (Imrie et al., Citation2009).

CONCLUSIONS: TOWARDS A RESEARCH AGENDA

Although London planning has long been driven by a growth logic (Imrie et al., Citation2009), the expansion of OAs in London and their growing centrality to the planning of the city and its infrastructure represents a change in the nature of strategic metropolitan planning that has wider significance given the increasing concentration of economic growth and policy attention in large metropolises across Europe. First introduced in 2004 by the mayor of London as a quasi-planning tool primarily to facilitate regeneration on brownfield land, OAs have since expanded in both number and territorial coverage and have been re-purposed to direct and coordinate growth around new infrastructure provision in a wide variety of locations that are identified as having development capacity. Arguably, in the absence of wider effective city-regional planning, the thrust of metropolitan planning has been to find new mechanisms to accommodate growth through densification within the Greater London boundary.

This has been enabled through the fostering of soft spaces of planning (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009) – OAs in this case – that have evolved as informal meso-scale planning tools or new ‘institutional fixes’ to enable flexibility and fast-track planning. OAs are deployed as territorial tools to locate places of potential, with high-level targets set for delivery of jobs and homes, performing a powerful symbolic function within the metropolitan area, and acting as a signal to both real estate and local state interests. They are flexible in scale, with undefined boundaries that change and morph, and they become institutionalized and de-institutionalized over time (Purkarthofer, Citation2018). Some OAs sit clearly within individual local authority areas, others sit on the boundaries of more than one, and how they relate to borough-level statutory planning frameworks is variable. Although this suggests possible tensions between the metropolitan and local levels of state government, with the latter traditionally being seen as the guardians of local public interests, there is equally a possibility that the reliance of local government on large-scale development to fund public infrastructure (Robinson & Attuyer, Citation2020) has drawn the metropolitan and local state into closer dependency than previously. This shifting relationship between metropolitan and local territorial politics, and the impact on the ground of top-down target setting and planning-by-numbers, in the context of an increasingly viability-driven planning system (Ferm & Raco, Citation2020), would be a fruitful area for future research.

An evaluation of the cumulative spatial and social impact of OAs has yet to be undertaken. In any future work on this, the question of ‘opportunity for whom’ (Curtis et al., Citation2017) will be a key consideration. Focusing on the impacts on communities within, as well as between, the soft spaces of OAs would draw attention to the intra-urban inequalities that are generated or reinforced by these soft planning approaches. Whereas the attention to date in the literature on intra-urban inequalities (Henderson, Citation2018) has been on the uneven spatial distribution of growth generated by instruments that boost some areas over others, we have revealed here that there are questions of inequalities arising even within designated OA areas. Evidence to date suggests that local communities are critically concerned about a lack of social and community infrastructure, displacement, quality of life and health in the OAs that are underway (Robinson & Attuyer, Citation2020). These tensions are perhaps inevitable by-products of an approach to economic development that continues to promote already successful city-regions, and areas within city-regions, at the expense of ‘less successful’ places in order to sustain a globally focused growth agenda.

Given the non-statutory nature of OAs, they have also been linked to the literature on the projectification of planning, invoking short-termism. However, this paper has revealed the persistent existence of the same OAs over time and their very slow development, with some ‘nascent’ OAs remaining so sixteen years after they were first designated. This might support Metzger’s (Citation2013) assertion that these spaces gradually become hardened through discourse and practice. This suggests some further consideration might be given in theoretical terms to the temporality of soft spaces of planning, and the institutional responses that emerge. Further research is required to understand to what extent the designation of OAs help to create the necessary demand for large-scale transformations to happen, in other words the nature of the relationship between these soft spaces of planning and investor and developer appetite and action.

Our wide investigation into the range of OAs across London suggests metropolitan planning has become less about providing strategic direction for local plans to conform to and more about brokering high-level relationships that promote growth, embedding market signals about growth locations and planning tolerances, and underpinning these actions through financial instruments that enable land value capture. The extent to which local authorities’ dependence on metropolitan government clout to broker the relationships required to deliver cross-border infrastructure and attract global investment weakens their position in negotiating for local public benefit is a further line of investigation. The research suggests that the brokering role of OAs might be bringing about a reorganization of the institutional scales of planning, which will make public scrutiny even harder to achieve. What is clear is that the focus on high-level brokerage raises questions about the role and meaningful participation of local communities in these relational dialogues. The explosion of soft spaces of planning in the London metropolitan region, which are primarily relational rather than territorial in nature (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2010), relies – as Faludi (Citation2010) has emphasized – on the ongoing cooperation and coordination of a variety of actors across diverse contexts and time horizons. Understanding the cumulative, long-term social, environmental and economic impacts of this intervention forms the basis, we suggest, for a substantial research agenda.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the editor and two anonymous referees for helpful comments, and Professor Mike Raco for comments on an earlier draft of this article. We also thank members of Just Space for insights on various local campaigns across and emerging challenges in a variety of Opportunity Areas, which partly inspired the writing of this paper.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. For example, see the London Borough of Sutton’s (Citation2018) response to the London Plan consultation draft.

REFERENCES

- Allmendinger, P., & Haughton, G. (2009). Soft spaces, fuzzy boundaries, and metagovernance: The new spatial planning in the Thames gateway. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 41(3), 617–633. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/a40208

- Allmendinger, P., & Haughton, G. (2010). Spatial planning, devolution, and new planning spaces. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 28(5), 803–818. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/c09163

- Allmendinger, P., & Haughton, G. (2013). The evolution and trajectories of English spatial governance: ‘Neoliberal’ episodes in planning. Planning Practice and Research, 28(1), 6–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2012.699223

- Allmendinger, P., Haughton, G., & Shepherd, E. (2016). Where is planning to be found? Material practices and the multiple spaces of planning. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 34(1), 38–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15614178

- Bowie, D. (2017). Radical solutions to the housing supply crisis. Policy Press.

- Brown, R., Eden, S., & Bossetti, N. (2018). Next-door neighbours – Collaborative working across the London boundary. Centre for London. https://www.centreforlondon.org/publication/collaboration-across-london-boundary/

- Byrne, M. (2016). Entrepreneurial urbanism after the crisis: Ireland’s ‘bad bank’ and the redevelopment of Dublin’s Docklands. Antipode, 48(4), 899–918. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12231

- Cochrane, A. (2007). Understanding urban policy: A critical approach. Blackwell.

- Crouch, C., & Le Galès, P. (2012). Cities as national champions? Journal of European Public Policy: Economic Patriotism: Political Intervention in Open Economies, 19(3), 405–419. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.640795

- Curtis, A., Cargill Thompson, J., Honegger, L., Kafka, G., Liu, W., Montero, A., Mountain, D., Salmi, J., & Seow, N. (2017). Opportunity for whom? How communities engage with land value capture in Opportunity Areas. University College London (UCL). https://www.academia.edu/34860139/Opportunity_For_Whom_How_Communities_Engage_With_Land_Value_Capture_in_Opportunity_Areas

- Dorling, D., Rigby, J., Wheeler, B., Ballas, D., Thomas, B., Fahmy, E., Gordon, D., & Lupton, R. (2007). Poverty, wealth and place in Britain, 1968 to 2005. Policy Press.

- European Commission. (2011). Territorial agenda of the European Union 2020. Towards an inclusive, smart and sustainable Europe of diverse regions. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/communications/2011/territorial-agenda-of-the-european-union-2020

- Faludi, A. (2010). Beyond Lisbon: Soft European spatial planning. disP – The Planning Review, 46(182), 14–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2010.10557098

- Ferm, J., & Raco, M. (2020). Viability planning, value capture and the geographies of market-led planning reform in England. Planning Theory & Practice, 21(2), 218–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2020.1754446

- Freire Trigo, S. (2020). Vacant land in London: A planning tool to create land for growth. International Planning Studies, 25(3), 261–276, https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2019.1585231

- Glaeser, E. L. (2011). Triumph of the city. Pan.

- Greater London Authority (GLA). (2004). The London Plan: Spatial development strategy for Greater London. GLA. https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/planning/london-plan/past-versions-and-alterations-london-plan/london-plan-2004

- Greater London Authority (GLA). (2011). The London Plan: Spatial development strategy for Greater London. GLA. https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/planning/london-plan/past-versions-and-alterations-london-plan/london-plan-2011

- Greater London Authority (GLA). (2016). The London Plan. The spatial development strategy for London consolidated with alterations since 2011. https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/planning/london-plan/current-london-plan/london-plan-2016-pdf

- Greater London Authority (GLA). (2017). The London strategic housing land availability assessment 2017. https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2017_london_strategic_housing_land_availability_assessment_0.pdf

- Greater London Authority (GLA). (2019). New London Plan Examination in Public (EiP) 2019. Opportunity Areas (M14). London Datastore. https://data.london.gov.uk/download/london-plan-eip-2019/cea94dd2-f2ba-4f3d-a2af-905bcbe75934/EIP%20-%2022%20January%202019.wav

- Greater London Authority (GLA). (2021). The London Plan. The spatial development strategy for Greater London https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/the_london_plan_2021.pdf

- Greater Sydney Commission. (2019). Partnerships and place: Insights from collaboration areas 2017–19. Greater Sydney Commission. https://www.greater.sydney/project/collaboration-areas

- Henderson, S. (2018). Competitive sub-metropolitan regionalism: Local government collaboration and advocacy in northern Melbourne, Australia. Urban Studies, 55(13), 2863–2885. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017726737

- HM Treasury. (2004). Review of housing supply. Delivering stability: Securing our future housing needs. HMSO. http://www.andywightman.com/docs/barker_housing_final.pdf

- Hulst, R., & van Montfort, A. (2007). Inter-municipal cooperation in Europe. Springer.

- Iammarino, S., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2017). Why regional development matters for Europe’s economic future. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/work/201707_regional_development_matters.pdf

- Imrie, R., Lees, L., & Raco, M. (Eds.). (2009). Regenerating London: Governance, sustainability and community in a global city. Routledge.

- Lennon, M., Scott, M., & Russell, P. (2018). Ireland’s new national planning framework: (Re)balancing and (re)conceiving planning for the twenty-first century? Planning Practice & Research, 33(5), 491–505. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2018.1531581

- London Borough of Sutton. (2018). Representations on the draft London Plan. https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/London%20Borough%20of%20Sutton%20%282044%29.pdf

- Metzger, J. (2013). Raising the regional leviathan: A relational–materialist conceptualization of regions-in-becoming as publics-in-stabilization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(4), 1368–1395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12038

- Moore-Cherry, N., Tomaney, J., & Pike, A. (Forthcoming 2021). City-regional and metropolitan governance. In M. Callanan and J. Loughlin (Eds.), A research agenda for regional and local government. Edward Elgar. https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/gbp/a-research-agenda-for-regional-and-local-government-9781839106637.html

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). 2011. Inequality exists across England and Wales in the proportion of people reporting that their daily activities were limited The National Archives. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160107055629/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/census/2011-census-analysis/local-authority-variations-in-self-assessed-activity-limitations–disability–for-males-and-females–england-and-wales-2011/sty-activity-limitation.html

- Paasi, A., & Metzger, J. (2017). Foregrounding the region. Regional Studies: 50th Anniversary Special Issue, 51(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1239818

- Paasi, A., & Zimmerbauer, K. (2016). Penumbral borders and planning paradoxes: Relational thinking and the question of borders in spatial planning. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15594805

- Parker, G., Street, E., Raco, M., & Freire-Trigo, S. (2014). In planning we trust? Public interest and private delivery in a co-managed planning system. Town and Country Planning, 83(12), 537–540.

- Pemberton, S., & Searle, G. (2016). Statecraft, scalecraft and urban planning: A comparative Study of Birmingham, UK, and Brisbane, Australia. European Planning Studies, 24(1), 76–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1078297

- Pike, A., O’Brien, P., Strickland, T. L., Thrower, G., & Tomaney, J. (2019). Financialising city statecraft and infrastructure. Edward Elgar.

- Pike, A., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2007). What kind of local and regional development and for whom? Regional Studies, 41(9), 1253–1269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701543355

- Purkarthofer, E. (2018). Diminishing borders and conflating spaces: A storyline to promote soft planning scales. European Planning Studies, 26(5), 1008–1027. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1430750

- Raco, M. (2014). Delivering flagship projects in an era of regulatory capitalism: State-led privatization and the London Olympics 2012. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(1), 176–197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12025

- Riddell, C. (2019). Finding our way back to effective strategic planning in England. Town and Country Planning, 88(11), 477–482.

- Robin, E. (2018). Performing real estate value(s): Real estate developers, systems of expertise and the production of space. Geoforum. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.05.006

- Robinson, J., & Attuyer, K. (2020). Extracting value, London style: Revisiting the role of the state in urban development. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12962

- Scott, A. J. (2008). Resurgent metropolis: Economy, society and urbanization in an interconnected world. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32(3), 548–564. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00795.x

- Scott, A. J., & Storper, M. (2015). The nature of cities: The scope and limits of urban theory. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12134

- TCPA. (2018). Planning 2020. Raynsford review of planning in England. Final Report. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=30864427-d8dc-4b0b-88ed-c6e0f08c0edd

- Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2009). Governing London: The evolving institutional and planning landscape. In R. Imrie, L. Lees & M. Raco (Eds.), Regenerating London: Governance, sustainability and community in a global city (pp. 58-72). Routledge.

- Transport for London (TfL). (2019). Funding sources TfL. https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/investors/funding-sources

- The Planning Inspectorate. (2019). Report of the Examination in Public of the London Plan 2019. https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/planning/london-plan/new-london-plan/what-new-london-plan

- Urban Task Force. (1999). Towards an urban renaissance: Final report of the urban task force. Spon.

- Zimmerbauer, K., & Paasi, A. (2020). Hard work with soft spaces (and vice versa): Problematizing the transforming planning spaces. European Planning Studies, 28(4), 771–789. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1653827