ABSTRACT

This paper investigates how actors across spatial levels shape the directions of transition. We examine two Chinese provinces, Inner Mongolia and Jiangsu, with contrasting directionalities of solar photovoltaic (PV) development. The former developed PV as part of the large-scale centralized power system, and the latter focused on PV development as a core element of an alternative distributed form of power generation. We argue that three aspects have been key for understanding the divergent patterns: the specific portfolio of enacted institutional work; the type of interactions between niche and regime actors; and the selective leveraging of national institutional conditions by provincial actors.

INTRODUCTION

The scaling of solar photovoltaics (PV) is one of the major decarbonizing success stories. Generation costs per kWh have decreased by more than 95% since the 1970s (Kavlak et al., Citation2018), and this has led to a large scale of diffusion of solar PV over the last decade (SolarPower Europe, Citation2018). However, despite the success of this technology, the ultimate impact on the structure of the electricity sector remains unclear. Will solar just be an additional source of energy in an otherwise unchanged centralized electricity system or will the diffusion of solar lead to a fundamental restructuring of the sector towards more decentralized power generation with new grids, business models and use patterns? This is a question about the directionality of the transition. We conceptualize two directions: optimizing of the existing institutions in the electricity system in order to accommodate more solar power or transforming those existing institutions as a consequence of the adoption of solar. Our research question is formulated as follows: What kind of strategies do actors enact in order to shape the directionality of a transition?

Our point of entry in order to answer this question is to build on insights from recent studies on institutional work (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006). This literature conceptualizes institutional change as the outcome of actors’ attempts to maintain, create or disrupt institutions (Lawrence et al., Citation2009). Recently, several studies have started to show how concepts of institutional work may be fruitful for analysing sustainability transitions (Binz et al., Citation2016; Brown et al., Citation2013; Fünfschilling & Truffer, Citation2016). We will build on these recent insights but extend them in important respects in order to address questions of directionality. First, we do not assume that most of the transformative institutional work is carried out by niche actors, leaving regime actors in an essentially defensive position. Therefore, we adopt an open attitude regarding the portfolios of institutional work different actors employ, irrespective of their degree of incumbency. Second, and as a consequence, we want to explicitly consider the kind of relationships established between incumbents and new entrants in support of either of the two development patterns. Third, given that institutional structures are defined at different levels of jurisdictions, we propose to analyse institutional work as strategies that may operate at and across different spatial scales.

To answer our research question, we present a comparative case study of the deployment of solar PV in two Chinese provinces, Inner Mongolia and Jiangsu (Yin, Citation2014). These provinces represent strong cases within China for either a centralized, large-scale application of PV (Inner Mongolia) or for a more radical, decentralized trajectory (Jiangsu). Both provinces are leaders in terms of PV deployment, and both operate under the same overarching Chinese industrial and energy policy conditions. The provinces differ with regard to their degree urbanization, industrial structure and population density that may influence the specific technological trajectory. Our assumption is, however, that these factors are not sufficient to explain the different directionalities and that the interplay of actors and distinct forms of institutional work are key to explain the observed divergent development patterns.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section introduces the literature on institutional work and discusses how questions of directionality can be addressed in the analysis of sustainability transitions. Three core aspects are elaborated: (1) portfolios of institutional work; (2) interactions between niche and regime actors; and (3) the multiscalar dimension of institutional work. The third section describes the methodology. The fourth section elaborates on the institutional work actors adopted to shape China’s solar PV development in the two focal provinces as well as at the national level. The fifth section discusses how local actors performed institutional work to shape the directionality of the respective development trajectories in the two provinces. The six section draws the implications of this research for how directionality could be addressed in future transition studies.

Institutional work and directionality

There have been different perspectives on why radical socio-technical change occurs. The most accepted view in sustainability transitions studies is that system change is driven by a combination of exogenous and endogenous driving forces. Moreover, the external shocks ‘do not mechanically impact niches and regimes, but need to be perceived and translated by actors to exert influence’ (Geels & Schot, Citation2007, p. 404). This implies that the actual directions of change are shaped by strategic action (Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Markard & Truffer, Citation2008; Pacheco et al., Citation2010; Smith et al., Citation2010; Yap & Truffer, Citation2019). Although there are many studies on the role of agency in shaping sustainability transitions, there is still limited understanding about how this agency shapes the directionality of the change process. Farla et al. (Citation2012) and Smith and Raven (Citation2012) suggest drawing upon institutional scholarship to fill this gap, and we follow this suggestion given our interest in studying two directions as possible outcomes of a sustainability transition: regime optimization and radical regime transformation. Both imply institutional change, but of a different nature.

Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006) introduced the concept of ‘institutional work’ to explore the proactive role of actors in shaping institutional change. Institutional work conceptualizes how actors purposively engage (individually and collectively) in an effort to prevent or generate institutional change. Lawrence and Suddaby categorize three strategies of institutional work actors can engage in: keep institutions alive (maintenance in the regime), change them (disruption of the regime) or create new ones (built-up niches and reconfiguration of socio-technical elements for new technologies). These three mechanisms are also reflected in sustainability transitions research, where regime actors are conceptualized as primarily busy with reproducing the regime in order to maintain their vested interests (Geels, Citation2014; Hensmans, Citation2003; Hess, Citation2014; Maguire & Hardy, Citation2009; Smink et al., Citation2015; Ting & Byrne, Citation2020). Niche actors in contrast endeavour to create new institutions by setting up protective spaces that enable the maturing and scaling of their preferred alternatives (Geels, Citation2004; Geels et al., Citation2016; Seyfang & Haxeltine, Citation2012). Recent transition studies started to articulate the crucial role of disrupting institutional work by actors who aim at the destabilization of the regime in order to shape the direction of transition (Brown et al., Citation2013; Kivimaa, Citation2014; Kivimaa & Kern, Citation2016).

The three types of strategies can be detailed further. Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006) proposed a list of 18 forms of work by which actors can influence institutions. Drawing on contributions by Scott (Citation2001), we group them by how prominently they address the regulative, normative or cognitive pillar, respectively (). Regulative pillar refers to formal rules, such as laws and government policies. Normative rules refer to values and social norms. Cognitive rules refer to the beliefs and symbolic meanings (Scott, Citation2001). We can take from the literature that mechanisms of creating institutions, include advocacy, defining and vesting. These ‘reflect overtly political work in which actors reconstruct rules, property rights and boundaries that define access to material resources’ (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006, p. 221). Therefore, they contribute primarily to the build-up of regulative rules. Constructing identities, normative networks and changing normative associations emphasize ‘actions in which actors’ belief systems are reconfigured’ (p. 221) and therefore address primarily the normative pillar. And finally, mimicry, theorizing and educating alter the meanings and things taken for granted, and therefore address primarily cognitive rules. For lack of space, we are not in a position to offer a detailed description of the different forms of institutional work. Readers are referred to Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006) and Fünfschilling and Truffer (Citation2016) for further elaborations (see also ).

Table 1. Mechanisms of actors’ institutional work shaping the different pillars of institutions.

For the purpose of our analysis, we want to make two points here. (1) We expect that not all the listed forms of institutional work shown in need to be performed during the process of sustainability transition. For the specific directions of sustainability transition, specific combinations of different forms of institutional work may be needed (creating, maintaining and disrupting) across three institutional pillars (cognitive, normative and regulative). (2) These three institutional pillars generally align with each other to maintain resilient regimes (Geels, Citation2004). However, when shifts occur in one of these institutional pillars, it may create windows of opportunity for changes in other pillars too and thus more radical institutional/regime change is likely to result. We propose to call a specific combination of different forms of institutional work a portfolio. Our assumption is that if actors, through such a portfolio of institutional work, shape all three institutional pillars substantially, the direction of change will be more radical (Ghosh & Schot, Citation2019).

Recently several further empirical studies have been conducted in the sustainability transitions field to explore the relevance of institutional work in order to explore how actors proactively build niches (Brown et al., Citation2013), or direct the course of socio-technical regime change (Fünfschilling & Truffer, Citation2016). However, these studies focus either on the singular socio-technical system transitions (Brown et al., Citation2013; Fünfschilling & Truffer, Citation2016; Novalia et al., Citation2018) or on institutional work towards specific types of institutional change – for example, towards technology legitimacy (Binz et al., Citation2016) or policy change (Hess, Citation2014). There has been less attention on which actors are doing which type of institutional work, and how this influences the directionality of sustainability transitions.

The directionality battle is not about whether the new (niche actors) will win over the old (regime actors). In our research we do not want to tie regime actors upfront to a strategy of maintaining institutions (defending the regime) while niche actors do the creating (building niches) and disrupting work (destabilizing regimes). Rather, battles about the actual course of action may happen equally among regime actors within a prevailing regime as among actors supporting (potentially manifold) niches. Such a view accounts for a situation in which regime actors may operate in the niche and have an interest in promoting niches, while niche actors may not want to destroy the regime and prefer to operate at the niche level only. In the end, the unfolding directionality will be the result of interaction among actors with different degrees of incumbency (Jørgensen, Citation2012; Yap & Truffer, Citation2019). The fact that regime actors are not just defending the status quo has also been recognized in neo-institutional literature. The seminal work of Leblebici et al. (Citation1991) emphasized that internal institutional contradictions may emerge as a starting point for dominant actors to engage with institutional change. In transition studies, Fünfschilling and Truffer (Citation2014) elaborated how different institutional logics in a regime may create tensions within and among actors who are incumbents in the prevailing regime. We have therefore to account for a multiplicity of institutional work strategies of a multitude of actors, which are more or less tied to the prevailing regime structures.

Institutional work requires actors to work not only across niche and regime boundaries but also across spatial boundaries. The recently proposed approach of a ‘geography of transitions’ has started to scrutinize spatial dynamics (Coenen et al., Citation2012; Hansen & Coenen, Citation2015; Truffer et al., Citation2015; Truffer & Coenen, Citation2012). Sustainability transitions studies have traditionally focused on national-level studies, assuming that niche and regime structures would be essentially uniform within a national territory (Coenen et al., Citation2012). As argued by Coenen et al. (Citation2012), it is important not to conflate a conventional view on geography with levels in the multilevel perspective, equating niche with local, regime with national, and landscape with global processes and structures (Bridge et al., Citation2013; Coenen et al., Citation2012; Raven et al., Citation2012). A more geographically informed interpretation would see niche–regime interactions as happening at and across multiple scales to generate specific transition directions (Coenen et al., Citation2012; Fünfschilling & Binz, Citation2018). The regional variation was more easily acknowledged in niche processes (Boschma et al., Citation2017). Raven et al. (Citation2008), for instance, stressed that geographical contextualization was crucial for niche experiments. They argued that local actors reinterpret and reinvent the generic regimes, which enable local variations or the emergence of niches.

To address how actors mobilize institutional work in the spatially very different contexts, we have to conceptualize the regional specificity of both niche and regime structures. Socio-technical regimes may then be conceptualized as multiscalar structures with rules that may be interpreted by regional actors for their local contexts (resulting in regional implementation styles of national regulations). Institutional work can also be oriented towards working at different spatial levels. It can either focus on how regional actors try to shape institutions at the national level, or on how national-level rules are translated selectively into specific regional contexts. Not all actors have equal capability to conduct institutional work in such a multiscalar world. Some actors, such as big national companies, are boundary spanners. They can more easily leverage processes across different scales, while regionally anchored small to medium-sized enterprises will be more restricted. A spatial sensitive approach to institutional work is crucial to investigate how and why developments in certain regions move in divergent directions.

Based on this selective and focused literature review, we are now in the position to explore what portfolio of institutional work niche and regime actors adopt to shape divergent directions of sustainability transition. We will investigate the case of solar PV niche development in two Chinese provinces. One case represents a rather ideal-type regime optimization and the other a radical regime-transformation pattern. We will explore whether we can explain the different patterns by looking at the portfolio of institutional work assuming that such a portfolio may be responsible for the divergent patterns. We will investigate the relationships between niche and regime actors and whether and how they work together in performing institutional work. And finally, we will reconstruct how niche and regime actors adopt their institutional work across multiple scales (provincial and national).

METHODOLOGY

Case study selection strategy

This study focuses on China because of its rapid and large-scale diffusion of solar PV deployment over the last decade and also its divergent regional development. China also holds the global largest solar PV market (SolarPower Europe, Citation2018). The study adopts a comparative case study research design (Creswell, Citation2007; Yin, Citation2014). It investigates two contrasting cases that represent the regime optimization and transformation pattern: solar PV development in two Chinese provinces: Inner Mongolia and Jiangsu. They have both been leaders in China in promoting solar (National Energy Administration (NEA) statistics). The deployment of solar PV in Inner Mongolia is, however, dominated by large-scale centralized solar power plants with long-distance transmission, while Jiangsu is leading in terms of distributed solar PV (DSPV). The two proposed provinces therefore represent contrasting cases exemplifying different directionalities. To elaborate how different actors pushed for institutional change, we focus on the period between 2000 and 2018, which covers the major diverging development phases of solar PV in China.

Data collection and analysis

The study adopts a mix of data collection and analysis methods. Both primary and secondary data were collected. Primary data collection included semi-structured interviews, focus groups and workshop from two rounds of fieldwork, conducted from July 2017 to March 2018, and between December 2018 and January 2019. In total 42 experts were approached covering a wide range of stakeholders (see Table A1 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online for a list of all interviewees). Each interview lasted around one hour. All interviews were conducted in Mandarin, recorded with audiotape, transcribed and translated into English. The secondary data covered newspaper articles, policy documents, organizational reports, academic articles, etc. Relevant industry conferences were also attended to identify key stakeholders and collect useful documents (e.g., presentation slides and conference proceedings).

During a first round of fieldwork, 26 semi-structured interviews and six focus groups were conducted. They served to identify key processes of institutional change, and the role of different stakeholders for solar PV development at the national and provincial levels. Historical changes in national and provincial regulations were identified through secondary data, such as policy documents, newspaper articles and organizational reports. These documents were complemented and triangulated with individual interview data and workshop insights. Changes in cognitive and normative institutions were derived from the interview data.

Based on the information collected, we constructed a timeline of key institutional changes at the national and provincial levels at the end of the first round of fieldwork. We then invited stakeholders to a workshop in March 2018 in order to reflect on the detailed storylines (working with representatives of two provinces separately; hence, we organized two focus groups). The workshop served as both a triangulation for the interview data and an opportunity to specify the role of different stakeholders for solar PV development. In the workshop, the proactive role of local actors became obvious for explaining the diverging development patterns in the two provinces. Phrased by several participants, ‘the divergent development of solar power in the two provinces is largely promoted by the local actors’ (workshop, Beijing, 8 March 2018).

To identify how niche and regime actors adopted different forms of institutional work, we conducted a second round of fieldwork. We ran semi-structured interviews to investigate the specific role of local actors and asked which types of institutional work they mobilized to shape the divergent transition directions. Interviews have the advantage of exploring the invisible and often mundane dimensions of institutional work (Fünfschilling & Truffer, Citation2016). In total, 19 experts from the two provinces were approached with three follow-up interviews, and four focus groups were conducted.

We implemented an abductive coding approach. As a first step, we classified statements of the interviewees, according to the three institutional pillars as depicted in , in order to identify relevant institutional changes. Subsequently, we drew on the general forms of institutional work, as presented in , for a first round of coding the interviews. These codes were revised and refined in several rounds in order to generate a fine-grained and balanced code-tree in order to capture the different forms of institutional work in the two provinces. These data were complemented and validated with secondary data to identify the impacts of actors’ institutional work. Due to length restrictions, we will only be able to present literal quotations from interviews sparingly. They are primarily presented as illustrations for the kind of original data our analysis built on. These results are presented as storylines in the fourth section. To highlight the types of institutional work, we numbered creating institutional work as C1–C9, maintaining institutional work as M1–M6 and disrupting institutional work as D1–D3 (see Table A2 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online for coding structures). Table A3, also online, presents further evidence of different institutional work adopted by actors. Moreover, this evidence is summarized in .

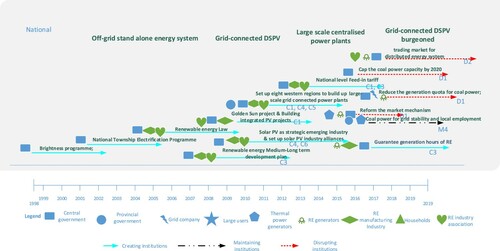

Figure 1. Institutional work and historical institutional change for solar photovoltaic (PV) development at the national level.

Note: Readers of the print version can view the figure in colour online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1903412.

Source: Authors.

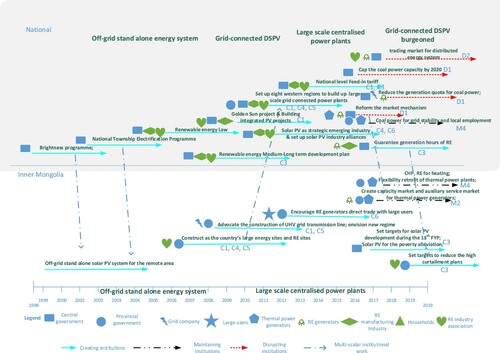

Figure 2. Institutional work and historical institutional change for solar photovoltaic (PV) development in Inner Mongolia and the national level.

Note: Readers of the print version can view the figure in colour online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1903412.

Source: Authors.

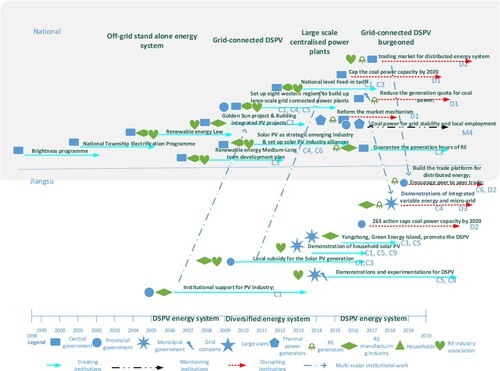

Figure 3. Institutional work and historical institutional change for solar photovoltaic (PV) development in Jiangsu and the national level.

Note: Readers of the print version can view the figure in colour online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1903412.

Source: Authors.

Table 2. Operationalization of the three institutional pillars.

SOLAR PV DEVELOPMENT

In this section we present the historical account of institutional change and different types of institutional work employed by both niche and regime actors for solar PV development from 2000 to 2018 in two focal provinces as well as the national level.

National level

China’s solar PV deployment from 2000 to 2018 can be categorized into three different stages. As depicted in , this process was shaped by different types of institutional work enacted by both niche and regime actors. The key regime actors involved include the thermal power generators, grid company, central government, provincial government and large users. The key niche actors include the solar PV manufacturing industry, solar PV generators and solar PV industry associations.

Before 2009, China’s solar PV deployment was dominated by off-grid stand-alone energy systems (Lv et al., Citation2018). The majority of cumulative PV capacity was located in rural areas that were lacking access to electricity (Bhattacharyya & Ohiare, Citation2012; Li et al., Citation2007; Wallace & Wang, Citation2006). Developments were mostly supported by the central government’s rural electrification programmes, such as the ‘Brightness Programme’ (光明工程) and the ‘National Township Electrification Programme’ (送电到乡). In 2005, China issued the Renewable Energy Law, which set the legal framework for its renewable energy deployment (Zhang & He, Citation2013). In 2007, the central government implemented the ‘Medium–Long Term Renewable Energy Development Plan’, which mandates that the grid company purchases all the generated renewable energy, and the large thermal power generators install a certain proportion of non-hydro-renewable energy (3% by 2010, 8% by 2020). This policy defined a new relationship between conventional utilities and renewable energy generators (vesting, C3). After 2006, the solar PV manufacturing industry took up rapidly in China, mainly aiming at serving rapidly growing markets in Europe and the United States (Fischer, Citation2012). The domestic application of solar PV was only marginal. In 2008, for instance, only 1.5% of the country’s solar PV cell production ended up serving the domestic market (China Renewable Energy Engineering Institute, Citation2012). The national solar PV manufacturing association articulated that the overreliance on overseas markets represented a high risk for Chinese manufacturers. They lobbied the central government to nurture the domestic market (interview, senior policy researcher, Beijing, 14 December 2017) (advocacy, C1). Especially after the global financial crisis in 2008, when the European solar PV market shrunk massively and imports from China were banned, advocacy for supporting solar PV industry development through indigenous markets became stronger (Huang et al., Citation2016). In 2009, the central government initiated the ‘Golden Sun’ project and the ‘Building Integrated PV’ project to boost the domestic market for solar PV (Huang et al., Citation2016).

Since 2009, China experienced a rapid take-up of large-scale centralized solar power plants (Zhang et al., Citation2014). This was shaped by the national solar PV manufacturing industry, together with provincial governments in the western part of China. They engaged in creating institutional work to address the regulative and normative pillars. To be specific, the types of institutional work they enacted included: advocacy (C1), vesting (C3), constructed identities (C4), changed normative associations (C5) and constructed normative networks (C6). The national solar PV industry association argued that large-scale solar power plants could efficiently prevent the desertification of the western provinces of China (C5). Together with provincial governments they lobbied the central government for support for the centralized power system, arguing that the build-up of large-scale centralized solar PV power plants was an efficient way to support industry development (C1). In 2010, the National Development and Reform Commission implemented concession projects to support 280 MW of large-scale centralized power plants in the western provinces (Inner Mongolia as one of them). At the same year, the central government denoted the solar PV industry as a strategic emerging industry for a low-carbon economy. This sent signals to social investors and also to local governments to support the industry (C4). In the same year, the Chinese solar PV Industry Alliance was established, which reinforced the solar PV industry’s lobby power to influence national support policy (Huang et al., Citation2016) (C6). From 2011, the central government set up national-level feed-in tariffs for solar PV-generated power (C3). This further burgeoned the rapid deployment of large-scale power plants.

From 2017, China started to witness a rapid increase in a second development pathway: distributed solar PV (DSPV). This has been a result of both creating and disrupting institutional work entertained by both niche and regime actors, especially at a provincial level (Zhang, Citation2016a). This will be elaborated on in the fourth section. The central government and niche actors, for example, disconnected market rewards for thermal power plants (D1), and dissociated coal power from its foundation as the basic power for electricity (D2). Coal power operators were challenged by the emerging requirement for them moving towards a cleaner, greener and low-carbon energy sector. In 2016, the central government implemented the ‘Energy Supply and Consumption Revolution Strategy’ policy, which capped coal power capacity by 2020 (D1). ‘Clean and low carbon’ have been articulated as the new vision for the next-generation energy system. In 2017, the NEA made a clear statement that:

with the further transformation of the country’s energy system, the future for coal power is to provide dispatching auxiliary service for renewable energy and to make space for renewable energy generation, while previously the function of thermal power was phrased as ‘to guarantee the supply of electricity.

(Cableabc.com, Citation2018) (D2)

To respond to the challenge, regime actors (thermal power generators and grid companies) also proactively shaped institutional change through valorizing and demonizing (M4). In recent years, coal power regime actors publicly rebuilt the good image of thermal power plants to maintain their strategic position in the electricity system. The coal power regime actors valorized the benefits of coal power plants as guaranteeing the safety and stability of the electricity system, while demonizing the grid connection of solar PV as causing stability problems. Moreover, they argued that China’s coal power plants have been much cleaner in terms of waste emissions compared with the level in 2013, and that coal power plants can offer more jobs compared with renewable energy (Zhao et al., Citation2013) (M4).

Inner Mongolia: regime optimization pattern

Inner Mongolia is leading in China’s renewable energy deployment. By the end of 2017, renewable energy contributed to 15.52% of the province’s total electricity generation mix, of which solar, wind and hydropower contributed 2.55%, 12.45% and 0.53%, respectively, while coal power contributed 84.47%.Footnote1 Solar PV was predominately installed in the form of large-scale centralized power plants. By the end of 2018, the total installed capacity of solar PV in Inner Mongolia was 9.45 GW, of which 9.12 GW (i.e., 97%) was in the form of centralized power plants.Footnote2

shows that the deployment of solar PV in Inner Mongolia moved from early-stage off-grid towards large-scale centralized configurations. This has been shaped by different types of institutional work leveraged by both niche and regime actors across different scales (both provincial and national). The key regime actors involved in Inner Mongolia include the thermal power generators, the provincial grid companies,Footnote3 the national and provincial governments, and large users. The key niche actors include the solar PV manufacturing industry, solar PV installers and operators, and national and provincial solar PV industry associations.

Supported by the central government’s rural electrification programmes, solar PV was initially targeted in Inner Mongolia to serve remote areas where there was lack access to electricity (Huo & Zhang, Citation2012; Li et al., Citation2007; Zhang & He, Citation2013) (see the dotted arrow from the national level to Inner Mongolia in ). These demonstration programmes were predominately off-grid residential solar PV systems.

Since 2005, both the national solar PV manufacturing industry and provincial government positioned Inner Mongolia as the perfect national site for large-scale solar power plants. They adopted different types of institutional work, such as lobbying (C1), vesting (C3), constructing identities (C4), changing normative associations (C5) and constructing normative networks (C6) to achieve this goal (). In 2005, Inner Mongolian experts collaborated with national-level research institutes in writing a report named ‘Inner Mongolia Energy Development Strategy Research’. They pointed out that positioning Inner Mongolia as the core national energy supply site was the solution for national energy security concerns (C4). As further advocated, solar PV was perceived as part of this strategy. The report furthermore argued that Inner Mongolia has decisive resource advantages with good solar incidence and large areas of available land, which is suitable for the installation of large-scale centralized PV power plants. These perceived advantages were mobilized by both the national solar PV industry association and the Inner Mongolian provincial government in order to lobby the central government that Inner Mongolia should be prioritized for building large-scale solar power plants (Hu et al., Citation2004) (C1, C4). ‘If we use half of the size of the desert in Inner Mongolia to build solar PV plants, then it can substitute all coal power plants in the country’ (C5) (interview, Inner Mongolia policy advisory expert, Hohhot, 23 January 2019). Moreover, the deployment of large-scale grid-connected solar power plants was regarded as one of the key strategies to promote the province’s economic development and environmental benefits. This fits the purpose of central government’s political agenda to support economically lagging provinces in the western part of China (see the dotted arrow from Inner Mongolia to the national level in ). The connection of solar PV with the national political agenda leveraged political legitimacy for central government support. In 2011, the central government identified Inner Mongolia as the national energy supply site as formulated in the policy document ‘Promote the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region’s Economic and Social Development’ (issued in 2011).Footnote4

Since 2012, renewable energy encountered high curtailment issues in Inner Mongolia due to the standstill of large-scale solar and wind power plants, which caused huge economic losses (Liu et al., Citation2018; Zhao et al., Citation2012). In 2012, the curtailment rates of renewable energy reached above 10% in Inner Mongolia. This undermined the political legitimacy for central government’s support to the region. To relieve this pressure, the local regime actors argued that a strong national transmission grid was a prerequisite to increase the clean energy share in the national electricity mix (C5). When the value of green and low carbon was increasingly accepted in society, grid companies mobilized the narrative of transmitting clean energy from Inner Mongolia to other regions to further lobby central government to support the construction of ultra-high-voltage grids (C1). The provincial electric power association expected that electricity demand would continuously grow in southern areas of China. Inner Mongolia could be the clean energy supplier for the country because of its rich renewable energy resource endowment (C6). Furthermore, the large economies of scale of the massive deployment of PV panels was said to help achieve the cost target of grid parity (C5). Aligning with the national policy to relieve the above accelerated high-curtailment problems of renewable energy (see the dotted arrow from the national level to Inner Mongolia in ), in 2018, the provincial solar PV industry association implemented the ‘Actions to Reduce the Curtailment of Clean Energy in Inner Mongolia’, which aims to achieve zero curtailment of renewable energy by the end of 2020 (C3). To achieve this and following the national-level electricity sector’s reform (see the dotted arrow from national level to Inner Mongolia in ), the provincial government formulated new policies, such as encouraging direct trade between renewable energy generators and large users to further consolidate the market advantages of the large-scale centralized power system (C6).

At a later stage, regime actors proactively mobilized maintaining institutional work to defend the thermal power-dominated centralized power regime (see the dashed line in ). The local regime actors (the grid company and thermal power generators) adopted valorizing and demonizing (M4) to maintain the legitimacy of large-scale power plants. The coal power regime actors valorized the benefits of coal power plants, which is clean with technology improvement and can attribute to the safety and stability of the electricity system. The provincial grid company demonized the integration of solar PV into the grid, which will cause fewer stability problems. Furthermore, strategies were adopted to encourage supply-side flexibility optimization, such as the flexibility retrofit of coal power plants, and setting up auxiliary service markets (M2). However, limited attention was given to demand-side flexibility.

In summary, all the above-referred institutional work mainly addressed regulative and normative pillars. This was confirmed by one of the local interviewees, who criticized the lack of cognitive change in the province: ‘If you treat wind and solar power the same as thermal power plants, and use the idea of managing the big thermal power plants to manage renewable energy, then it would not work’ (workshop participant, Beijing, 7 March 2018).

Jiangsu: regime transformation

Jiangsu has been historically leading the country’s installed capacity of DSPV. By the end of 2018, the total installed capacity of solar PV in Jiangsu was 13.32 GW, of which 40.5% was DSPV. The province is a national leader in DSPV because it represents 25.8% of the national DSPV cumulative capacity. Solar PV generation furthermore contributed 0.937% to the province’s electricity mix.Footnote5 Although this market share seems marginal, it has experienced rapid increase in the last decade.

shows niche and regime actors enacted different types of institutional work, by creating and disrupting mechanisms addressing all three institutional pillars (cognitive, normative and regulative), across both provincial and national levels. The key regime actors involved in Jiangsu include the thermal power generators, the provincial grid company, the national and the provincial government. The key niche actors include the solar PV manufacturing industry, solar PV generators, small to medium-sized solar PV installers, and the provincial solar PV industry association. Actors have been very actively shaping the institutions by creating institutional work, which include lobby (C1), vesting (C3), constructing identities (C4), changing normative associations (C5), constructing normative networks (C6), theorizing (C8) and educating (C9).

In the early 2000s, the provincial solar PV manufacturing enterprises, which are national leaders, proactively lobbied the provincial government to support solar PV deployment in Jiangsu (Li et al., Citation2007). Due to the then increasing electricity shortage problems in the province, solar PV was regarded as one of the solutions to supply clean electricity to the city. Local small and medium-sized enterprises played a leading role in investing in PV, which made the region become the leader in the Chinese solar DSPV market (CIConsulting, Citation2010). Especially after the global economic crisis in 2008, the provincial solar PV manufacturing industry association proactively lobbied the provincial government to implement a feed-in tariff to nurture indigenous markets in order to prevent large-scale bankruptcies in the Chinese industry (Grau et al., Citation2012; Huo & Zhang, Citation2012).

Using the taxes paid by the solar PV industry in order to support the local deployment of solar PV projects, is a worthwhile approach. … We persuaded the provincial government to continuously support the green industry by nurturing the market in the province, and now this mechanism is still in place.

(interview, Jiangsu provincial solar PV industry association, Nanjing, 21 December 2017)

Moreover, the provincial solar PV investors theorized new futures for the solar PV energy system and constructed new identities and values. Since 2014, the small and medium-sized enterprises and the provincial solar PV manufacturing industry constructed strong narratives about more localized energy being energy efficient (C5). They argued that the deployment of renewable energy offers opportunities for the province to achieve a higher share of clean and green energy in the local electricity mix (C4, C5). The deployment of distributed energy was perceived to hold a bright future in Jiangsu. With limited available land, it has less advantage to deploy large-scale solar PV power plants. On the contrary, with its concentration of heavy electricity consumers, such as industrial parks, Jiangsu is the perfect site to adopt DSPV energy (C8). As a result, the provincial ‘13th Five-Year Plan for Energy Development (2016–2020)’ portrayed DSPV as the main development pattern for solar PV deployment in Jiangsu. This led the provincial investors to develop more diversified business models for DSPV deployment (Zhang, Citation2016b) (C5). Apart from rooftop-based DSPV, ‘solar PV +’ business models emerged, such as ‘solar PV + water-related affairs’, ‘solar PV + fishing’, ‘solar PV + agriculture’ and ‘solar PV + transportation’ (Statistical Bureau of Jiangsu Province, Citation2017).

Furthermore, at the city level, the provincial solar PV investors collaborated with the municipal government to further demonstrate local experimentations to connect solar PV with broad social values. For example, in 2015, Yangzhong, a city in Jiangsu, set the goal of building ‘China’s Green Energy Island’ (Sun, Citation2017), and set-up a special funding scheme to promote public building-integrated and household rooftop-based DSPV. It demanded that, by 2030, renewable energy should contribute 100% to the local energy consumption (C3, C5). Another city, Zhenjiang, also supported grid-connected building-integrated solar PV systems, considering it as the crucial strategy for low-carbon city development (Wang et al., Citation2015). In January 2014, the village located in Donghai county of Lianyungang municipality was the first demonstration programme with rooftop DSPV systems connected to the grid in Jiangsu. This local experimentation demonstrated the deployment of household solar PV energy systems as being a success case to contribute to an ecological lifestyle. The village soon became a national model for ‘ecological civilisation’ and ‘beauty China’ (Xinhua News Agency, Citation2014, Citation2018) (C5, C8).

Local solar PV installers also educated users to further promote the local diffusion of DSPV. For example, Wuxi municipal government worked together with the local solar PV installers to promote ‘solar PV enter households’ (光伏进万家-无锡) activity to educate users about DSPV (C9). These local solar PV installers also built heterogenous networks with local government and the local grid company to promote institutional support for DSPV. These local networks enabled the local grid company to construct new identities for a next generation of power grids (C4, C5), and promoted new values, such as flexibility and smartness. As supported by an interviewee from the grid company in Jiangsu:

the utilities need to change their identities in the electricity market from being CHP (cooling, heating and power) providers to becoming energy service providers. This requires the grid company to provide more efficient energy services in order to respond to the diversified user demand. The age of the traditional business model which only concerns providing products from the grid company to the users without responding to the demand flexibility will become the past.

(project manager, Nanjing, 8 January 2019)

Moreover, we also observed niche actors enacting more visible disruptive institutional work at later stage, which included disconnecting sanctions (D1), disassociating moral foundations (D2) and undermining assumptions and beliefs (D3). Jiangsu has been one of the leading provinces to implement policy to cap the provincial-level coal power plants by 2020 (‘263 Action Plan’, 2016) (D1). Articulated by the provincial solar PV industry association, with rapidly decreasing panel costs, solar PV became increasingly economically competitive. It could finally challenge the thermal power in the market (D2). The distributed power generation is believed to be economically and energetically efficient. This undermined the assumptions and beliefs about the superiority of large-scale power plants and long-distance transmission lines (D3). Following the national electricity sector’s reform (issued in 2015), the province adopted strategies such as peer-to-peer trading to encourage the deployment of DSPV (see the provincial policy ‘Market Trade Guidance for DSPV Generation; 分布式发电市场化交易规则, 2019) (see the dashed line from the national to the provincial level in ). This allowed prosumers sell electricity to any consumers with a signed contract, which undermined the monopoly of the big utilities in the electricity retail market, and enabled further transformation of the centralized electricity regime.

DISCUSSION

Solar PV development patterns in the two Chinese provinces can be characterized as: Inner Mongolia following a regime optimization pattern and Jiangsu a regime transformation pattern. Following Smith and Raven (Citation2012) we characterize the two patterns as representing ‘fit-and-conform’ and ‘stretch-and-transform’ patterns. In this section we discuss how niche and regime actors adopted different forms of institutional work to shape these two divergent directions by elaborating on three aspects: (1) the portfolio of institutional work enacted; (2) the interactions between niche and regime actors; and (3) the multiscalar dimension of institutional work.

Portfolio of institutional work

Both our cases show that actors engaged in a rich array of institutional work identified in the literature. In other words, the institutional work portfolio differed substantially between the two provinces. We categorized above institutional work along two axes: institutional pillars (regulative, normative and cognitive) and types of institutional work (creating, maintaining and disrupting). In our case analyses, we mapped the portfolio for both provinces ( and ). This enables us to compare the portfolios of institutional work across cases. summarizes the various forms of institutional work presented by different pillars by colour code.

Table 3. Divergent portfolio of institutional work in the two Chinese provinces of Inner Mongolia and Jiangsu.

The Inner Mongolia case shows that a fit-and-conform transition pattern is more likely when actors adopt a portfolio of creating and maintaining institutional work and privilege the regulative and normative institutional pillar.

Inner Mongolia actors shaped the normative pillar through changing normative associations, constructing normative associations and networks (along the creating institutions axis), and valorized the centralized power plants and demonized decentralized power plants (along the maintaining institutional work axis). Inner Mongolia niche actors constructed normative associations of solar PV to the green and low-carbon values. As green and low-carbon visions became widely shared in society, the local regime actors actively adapted their grid development strategy to accommodate for an increasing share of renewable energy in the electricity mix. However, the Inner Mongolian grid company argued that the integration of solar power in the local grid would undermine the stability to further integrate solar energy to the large-scale centralized system. Moreover, the local regime actors adopted advocacy, vesting (along creating institutional work), enabling and policing (along maintaining institutional work) to address the regulative pillar. More specifically, the regional Grid company strongly argued in favour of building more long-distance transmission lines in order to transmit clean energy from Inner Mongolia to other Chinese regions. Also, the local government encouraged the direct trade between large-scale renewable energy generators and large-scale electricity users. This established new market relationships and further consolidated the large-scale centralized power system. These forms of institutional work forcefully ‘fit’ the development patterns of solar PV in order to ‘conform’ to the centralized system logics.

The Jiangsu case shows that the stretch-and-transform pattern corresponded to actors adopting a portfolio of creating and disrupting institutional work (ignoring maintaining work), while addressing all three institutional pillars. We characterize the portfolio using the three pillars as an entry point. The Jiangsu actors shaped the cognitive pillar by theorizing and educating (along the creating institutions axis) and undermining assumptions and beliefs (along the disrupting institutions axis) (). Niche actors educated users and theorized by voicing expectations on how future solar PV system would fit in a radically transformed electricity system based on more localized and energy-efficient distributed generation. This undermined the core assumptions and beliefs of the regime, namely that the primary task of the sector is to rely on cost-efficient large-scale centralized power plants, and hence long-distance transmission lines. Second, the niche actors were also providing moral and cultural foundations for the decentralized system (work belonging to the creation of institutions focusing on the normative pillar) and disassociated the moral foundations of thermal power plants (disrupting institutions with a strong normative pillar). The local solar PV enterprises – especially the small and medium-sized enterprises – actively constructed and mobilized normative and positive associations between solar PV and a local low-carbon and green-energy systems while thermal power was criticized as unsustainable. Other work belonging to the normative pillar consisted of mobilizing support for new business models that defined new identities to regime actors as energy service suppliers and build networks for new institutional support for a DSPV energy system. For instance, peer-to-peer trading schemes allowed prosumers sell surplus electricity to other users and therefore encroached on the established business model of the centralized grid company. Finally, we observe that local actors (local government, solar PV generators) also engaged in a mixture of creating and disrupting institutional work to reshape the regulative pillar. Local solar PV associations lobbied the provincial government for subsidies and other support resulting in vesting of targets and subsidies by the province (along the creating institutions axis). The provincial government also disconnected sanctions for coal power plants, which included capping coal power plans and reducing their subsidies (along the disrupting institutions axis).

Two differences between two cases stand out. We have formulated them in terms of propositions about the generalized relationships that we would also expect to find in other cases:

Proposition P1: The directionality of a transition will more likely follow a stretch-and-transform pattern if niche and regime actors adopt a portfolio of institutional work that consists of both creating and disrupting institutional work (while ignoring maintaining institutional work) and address all three institutional pillars.

Proposition P2: The directionality of a transition will more likely follow a fit-and-conform pattern if actors focus on creating and maintaining institutional work (while neglecting disrupting institutional work) and address both regulative and normative institutional pillars.

Niche–regime interactions

Both our cases show that niche and regime actors can adopt very diverse types of institutional work: creating, maintaining and disrupting ( and ). For example, in the case of Inner Mongolia, we saw that regime actors (the local government and the local grid company) engaged in creating institutional work, contributing to the development of solar PV, while they also developed maintaining institutional work to further consolidate the legitimacy of centralized power plants. This contrasts with the conventional understanding in transition studies where niche actors are mostly supposed to focus on niche creation and regime actors prefer to maintain the prevailing rule systems. The conventional view sees fit-and-conform and stretch-and-transform as essentially unidirectional processes, which suppose that niche actors either ‘fit’ to or ‘stretch’ the regime. We conclude from our study that the directionality should be better understood as a bidirectional process shaped by both niche and regime actors (this resonates with recent studies; Mylan et al., Citation2019).

However, in our cases there is still a difference in terms of niche–regime actor interactions. In the case of Jiangsu, we observe substantial local experimentations developed in networks of niche and regime actors. Niche actors are large solar panel manufacturers, and a large numbers of local solar PV installers. These local small and medium-sized enterprises held close interactions with the local municipal government, which enabled them to gain local government support for experimenting with DSPV. Moreover, the provincial industry association was able to communicate with the provincial government about the needs of the PV industry, which led to the adaptation of local institutions to the needs of solar PV. In Inner Mongolia, the niche–regime interaction was happening as well, but was not leading to any positive synergies in terms of institutional work. Some local niche actors (local solar PV generators) initiated disruptive institutional work. But they were unable to collaborate with regime actors who perceived limited promise to engage proactively in decentralized PV. This lack of niche–regime interactions shaped the movement towards a fit-and-conform pattern. In more general terms, we propose the following proposition:

Proposition P3: Stretch-and-transform patterns are more likely if niche actors play a leading role in shaping institutional change working with regime actors, while fit-and-conform patterns are more likely when regime actors play a leading role and are in the position to ignore the disruptive institutional work of niche actors.

The multiscalar dimension of institutional work

As a third aspect of conceptual refinement of the institutional work perspective, we identified the need to look at the multiscalar dimensions. In our case, this relates mostly to the way actors selectively interpret or intentionally shape institutions at the national level in order to support the respective transition directions at the provincial level. Two key insights can be generated from our analysis.

First, local actors proactively leveraged opportunities that resulted from the different niche and regime structures in the two regions (see the dotted arrows from the national level to the provincial level in and ). We observe that local actors selectively mobilized national context conditions (policies, visions and infrastructures) to achieve their preferred regional transition directions. For example, Jiangsu intentionally emphasized the liberalization-oriented electricity reform in order to open windows of opportunity for small and medium-sized enterprises, while Inner Mongolia mobilized the national development strategy for the western provinces to position itself as the leading clean energy supplier in China. This created the legitimacy for Inner Mongolia to build up the ultra-high voltage infrastructure for more centralized large-scale power plants.

Moreover, the two provinces interpreted national policies differently in order to encourage experimentation with different forms of solar PV integration into the grid. In the new round of the electricity sector’s reform (No. 9 Document), different provinces adopted divergent local experimentations. Jiangsu actors chose more disruptive market mechanisms, for example, encouraging peer-to-peer trading mechanisms, to support the deployment of DSPV. Inner Mongolia mainly aimed at market mechanisms to maintain the centralized power system, such as those required for cross-regional trade, which imply the long-distance transmission of electricity. Moreover, it encouraged the direct trade of renewable energy with large users, and the build-up of auxiliary service markets for thermal power plants to further protect the market advantages of large-scale power plants (Liu & Tan, Citation2016).

Second, provincial actors not only proactively mobilized external resources to fulfil the local energy vision, they also enacted different forms of institutional work to shape conditions at the national level, in order to support their preferred transition directions (see the dotted arrow from the provincial level to the national level in and ). For example, Inner Mongolian actors directly lobbied the central government to position the region as the country’s predominant energy producer. The close network between the central and the provincial governments of the western part of China enabled the mobilization of national resources to achieve the regional targets. This is in line with similar strategies observed for the case of wind power (Hu, Citation2014).

Moreover, large manufacturing enterprises shaped institutional change across different scales. For example, the large solar panel manufacturers in Jiangsu, such as Trina Solar, Xiexin and Suntech, have actively shaped both provincial- and national-level policies. In 2010, these big players, together with other partners, built up the Chinese solar PV Industry Alliance, which reinforced their power to lobby for a national solar PV supportive policy, such as domestic feed-in tariffs (Huang et al., Citation2016). The powers of these local actors in Jiangsu enabled the region to promote DSPV energy systems since 2013, long before the central government opened up to this direction.

The importance of multiscalar institutional work in these two provinces challenges the conventional understanding of China’s renewable energy development as a process exclusively steered by central government. Most existing studies portray China’s rapid renewable energy deployment as resulting from the central authorities’ active intervention to nurture domestic market and domestic industry (Hochstetler & Kostka, Citation2015; Lewis, Citation2013; Mathews, Citation2014). However, our two cases indicate that the two provinces’ divergent transition patterns are the outcome of interactive process between niche and regime actors across multiple scales (provincial and national levels) to intentionally shape socio-technical development. We translate our findings about multiscalar into a final general proposition:

Proposition P4: Multiscalar interactions of institutional work will influence the directionality of transitions in terms of emergence of a fit-and-conform or a stretch-and-transform pattern.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper investigates how institutional work adopted by niche and regime actors shapes the directionality of sustainability transitions in terms of fit-and-conform and stretch-and-transform patterns. Based on two strands of the literature, sustainability transitions and institutional work studies, we developed a more symmetrical analysis of niche and regime actors’ interactions. Instead of assuming that conventional niche actors focus exclusively on niche development while regime actors resist change, we trace how niche and regime actors may adopt different portfolios of institutional work in order to shape the process of socio-technical change. Moreover, we develop a more spatially sensitive concept of multiscalar institutional work to capture how niche and regime actors shape regional divergent directions of sustainability transition. The paper led to the formulation of four general propositions that have crucial policy implications. The policies aiming for more transformative change should nurture more heterogenous actors to work collectively to shape institutional change across all three institutional pillars. Especially, this study indicates that the build-up of shared visions across niche and regime actors is key, and when these shared visions allow for a leading role of niche actors combined with openings for new roles and identities of core regime actors, the emergence of a stretch-and-transform pattern is more likely.

We suggest the four propositions can be tested in follow-up studies. More comparative case studies could be conducted to provide a comprehensive overview of types of institutional work that are mobilized for a variety of contexts and systems. This study focused on the specific Chinese solar PV case. In general, the type of institutional work, the role of niche and regime actors, and the way multiscalar institutional work plays out may be different in other socio-technical systems and contexts. For example, in China concerned citizens did not play a major role in the process, while in Germany they had a clear voice (Dewald & Truffer, Citation2012). This may have important consequences for the distribution of types of institutional work in which actors engage. Moreover, our study indicates that the sustainability transitions literature could also contribute substantially to the institutional work literature. Future studies could develop a systematic review of institutional work employed by actors in the field of sustainability transitions studies. This could complement the types of institutional work identified in the field of institutional theory, on which this paper is based.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (174 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The first author also acknowledges Dr Ralitsa Hiteva for support for the SeNSS funding application, which made it possible to conduct the follow-up fieldwork for this study. The authors appreciate the comments received from two anonymous reviewers.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Data are from the Inner Mongolia Electric Power Association.

2. Data are from the NEA.

3. Two grid companies operate in Inner Mongolia: State Grid Inner Mongolia Eastern Power and Inner Mongolia Power Group, which operate independently in the east and west of Inner Mongolia, respectively.

5. Calculated by the authors = the generation from solar PV/the provincial’s total electric power generation. The size of electricity demand in Jiangsu province is twice the size of Inner Mongolia. Although the market share of solar PV generation in Jiangsu’s electricity mix is smaller than that of Inner Mongolia, the scale of the installed capacity of solar PV in Jiangsu is larger than that of Inner Mongolia.

REFERENCES

- Bhattacharyya, S. C., & Ohiare, S. (2012). The Chinese electricity access model for rural electrification: Approach, experience and lessons for others. Energy Policy, 49, 676–687. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.07.003

- Binz, C., Harris-Lovett, S., Kiparsky, M., Sedlak, D. L., & Truffer, B. (2016). The thorny road to technology legitimation – Institutional work for potable water reuse in California. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 103, 249–263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.10.005

- Boschma, R., Coenen, L., Frenken, K., & Truffer, B. (2017). Towards a theory of regional diversification: Combining insights from evolutionary economic geography and transition studies. Regional Studies, 51(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1258460

- Bridge, G., Bouzarovski, S., Bradshaw, M., & Eyre, N. (2013). Geographies of energy transition: Space, place and the low-carbon economy. Energy Policy, 53, 331–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.10.066

- Brown, R. R., Farrelly, M. A., & Loorbach, D. A. (2013). Actors working the institutions in sustainability transitions: The case of Melbourne’s stormwater management. Global Environmental Change, 23(4), 701–718. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.02.013

- Cableabc.Com. (2018). China first official declaration of the oversupply issue of electric power, the development of thermal power entering into a ‘reducing overcapacity’ stage. http://news.cableabc.com/hotfocus/20180103831737.html

- China Renewable Energy Engineering Institute. (2012). China solar power construction statistic report.

- CiConsulting. (2010). The geography distribution of solar PV in China. https://max.book118.com/html/2017/0715/122418556.shtm

- Coenen, L., Benneworth, P., & Truffer, B. (2012). Toward a spatial perspective on sustainability transitions. Research Policy, 41(6), 968–979. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.014

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

- Dewald, U., & Truffer, B. (2012). The local sources of market formation: Explaining regional growth differentials in German photovoltaic markets. European Planning Studies, 20(3), 397–420. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.651803

- Farla, J., Markard, J., Raven, R., & Coenen, L. (2012). Sustainability transitions in the making: A closer look at actors, strategies and resources. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 79(6), 991–998. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2012.02.001

- Fischer, D. (2012). Challenges of low carbon technology diffusion: Insights from shifts in China’s photovoltaic industry development. Innovation and Development, 2(1), 131–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2157930X.2012.667210

- Fünfschilling, L., & Binz, C. (2018). Global socio-technical regimes. Research Policy, 47(4), 735–749. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.02.003

- Fünfschilling, L., & Truffer, B. (2014). The structuration of socio-technical regimes – Conceptual foundations from institutional theory. Research Policy, 43(4), 772–791. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.10.010

- Fünfschilling, L., & Truffer, B. (2016). The interplay of institutions, actors and technologies in socio-technical systems – An analysis of transformations in the Australian urban water sector. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 103, 298–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.11.023

- Geels, F. W. (2004). From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems: Insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Research Policy, 33(6–7), 897–920. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2004.01.015

- Geels, F. W. (2014). Regime resistance against low-carbon transitions: Introducing politics and power into the multi-level perspective. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(5), 21–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414531627

- Geels, F. W., Kern, F., Fuchs, G., Hinderer, N., Kungl, G., Mylan, J., Neukirch, M., & Wassermann, S. (2016). The enactment of socio-technical transition pathways: A reformulated typology and a comparative multi-level analysis of the German and UK low-carbon electricity transitions (1990–2014). Research Policy, 45(4), 896–913. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2016.01.015

- Geels, F. W., & Schot, J. (2007). Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Research Policy, 36(3), 399–417. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003

- Ghosh, B., & Schot, J. (2019). Towards a novel regime change framework: Studying mobility transitions in public transport regimes in an Indian megacity. Energy Research & Social Science, 51, 82–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.12.001

- Grau, T., Huo, M., & Neuhoff, K. (2012). Survey of photovoltaic industry and policy in Germany and China. Energy Policy, 51, 20–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.03.082

- Grillitsch, M., Hansen, T., Coenen, L., Miörner, J., & Moodysson, J. (2018). Innovation policy for system-wide transformation: The case of strategic innovation programmes (SIPs) in Sweden. Research Policy, 48(4), 1048–1061. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.10.004

- Hansen, T., & Coenen, L. (2015). The geography of sustainability transitions: Review, synthesis and reflections on an emergent research field. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 17, 92–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2014.11.001

- Hensmans, M. (2003). Social movement organizations: A metaphor for strategic actors in institutional fields. Organization Studies, 24(3), 355–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840603024003908

- Hess, D. J. (2014). Sustainability transitions: A political coalition perspective. Research Policy, 43(2), 278–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.10.008

- Hochstetler, K., & Kostka, G. (2015). Wind and solar power in Brazil and China: Interests, state–business relations, and policy outcomes. Global Environmental Politics, 15(3), 74–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00312

- Hu, X. (2014). State-led path creation in China’s rustbelt: The case of Fuxin. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 1(1), 294–300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2014.976652

- Hu, X., Zhou, X., Bai, X., & Zhang, W. (2004). Development prospects for the very large-scale PV power generation and its electric power systems in China. Science & Technology Review, 22, 4–8.

- Huang, P., Negro, S. O., Hekkert, M. P., & Bi, K. (2016). How China became a leader in solar PV: An innovation system analysis. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 64, 777–789. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.06.061

- Huo, M.-L., & Zhang, D.-W. (2012). Lessons from photovoltaic policies in China for future development. Energy Policy, 51, 38–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.12.063

- Jørgensen, U. (2012). Mapping and navigating transitions – The multi-level perspective compared with arenas of development. Research Policy, 41(6), 996–1010. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.03.001

- Kavlak, G., McNerney, J., & Trancik, J. E. (2018). Evaluating the causes of cost reduction in photovoltaic modules. Energy Policy, 123, 700–710. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.08.015

- Kivimaa, P. (2014). Government-affiliated intermediary organisations as actors in system-level transitions. Research Policy, 43(8), 1370–1380. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.02.007

- Kivimaa, P., & Kern, F. (2016). Creative destruction or mere niche support? Innovation policy mixes for sustainability transitions. Research Policy, 45(1), 205–217. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.09.008

- Lawrence, T. B., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutions and institutional work, 2nd edition. In S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. B. Lawrence, & W. R. Nord (Eds.), Handbook of organization studies. Sage.

- Lawrence, T. B., Suddaby, R., & Leca, B. (2009). Institutional work: Actors and agency in institutional studies of organizations. Cambridge University Press.

- Leblebici, H., Salancik, G. R., Copay, A., & King, T. (1991). Institutional change and the transformation of interorganizational fields: An organizational history of the US radio broadcasting industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 333–363. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2393200

- Lewis, J. I. (2013). Green innovation in China: China’s wind power industry and the global transition to a low-carbon economy. Columbia University Press.

- Li, J., Wang, S., Zhang, M., & Ma, L. (2007). China solar PV report. China Environmental Science Press.

- Liu, P., & Tan, Z. (2016). How to develop distributed generation in China: In the context of the reformation of electric power system. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 66, 10–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.07.055

- Liu, S., Bie, Z., Lin, J., & Wang, X. (2018). Curtailment of renewable energy in Northwest China and market-based solutions. Energy Policy, 123, 494–502. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.09.007

- Lv, F., Xu, H., Wang, S., Li, H., Ma, L., & Li, P. (2018). National survey report of PV power applications in China. In International energy agency: Photovoltaic power systems technology collaboration programme. China PV Industry Association.

- Maguire, S., & Hardy, C. (2009). Discourse and deinstitutionalization: The decline of DDT. Academy of Management Journal, 52(1), 148–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.36461993

- Markard, J., & Truffer, B. (2008). Technological innovation systems and the multi-level perspective: Towards an integrated framework. Research Policy, 37(4), 596–615. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.01.004

- Mathews, J. A. (2014). Greening of capitalism: How Asia is driving the next great transformation. Stanford University Press.

- Mylan, J., Morris, C., Beech, E., & Geels, F. W. (2019). Rage against the regime: Niche-regime interactions in the societal embedding of plant-based milk. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 31, 233–247.

- Novalia, W., Brown, R. R., Rogers, B. C., & Bos, J. J. (2018). A diagnostic framework of strategic agency: Operationalising complex interrelationships of agency and institutions in the urban infrastructure sector. Environmental Science & Policy, 83, 11–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.02.004

- Pacheco, D. F., York, J. G., Dean, T. J., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2010). The coevolution of institutional entrepreneurship: A tale of two theories. Journal of Management, 36(4), 974–1010. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309360280

- Raven, R., Schot, J., & Berkhout, F. (2012). Space and scale in socio-technical transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 4, 63–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2012.08.001

- Raven, R. P., Heiskanen, E., Lovio, R., Hodson, M., & Brohmann, B. (2008). The contribution of local experiments and negotiation processes to field-level learning in emerging (niche) technologies: Meta-analysis of 27 new energy projects in Europe. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 28(6), 464–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467608317523

- Scott, W. R. (2001). Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Seyfang, G., & Haxeltine, A. (2012). Growing grassroots innovations: Exploring the role of community-based initiatives in governing sustainable energy transitions. Sage.

- Smink, M. M., Hekkert, M. P., & Negro, S. O. (2015). Keeping sustainable innovation on a leash? Exploring incumbents’ institutional strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(2), 86–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1808

- Smith, A., & Raven, R. (2012). What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Research Policy, 41(6), 1025–1036. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.12.012

- Smith, A., Voß, J.-P., & Grin, J. (2010). Innovation studies and sustainability transitions: The allure of the multi-level perspective and its challenges. Research Policy, 39(4), 435–448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.023

- SolarPower Europe. (2018). Global market outlook for solar power 2018–2022.

- Statistical Bureau of Jiangsu Province. (2017). The development status and strategy of new normal of Jiangsu’s solar PV industry. http://www.jssb.gov.cn/tjxxgk/tjfx/sjfx/201707/t20170714_307347.html

- Sun, W. (2017). Yangzhong: China’s green energy island. Mondern Express. https://www.ne21.com/news/show-97738.html

- Ting, M. B., & Byrne, R. (2020). Eskom and the rise of renewables: Regime-resistance, crisis and the strategy of incumbency in South Africa’s electricity system. Energy Research & Social Science, 60, 101333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101333

- Truffer, B., & Coenen, L. (2012). Environmental innovation and sustainability transitions in regional studies. Regional Studies, 46(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.646164

- Truffer, B., Murphy, J. T., & Raven, R. (2015). The geography of sustainability transitions: Contours of an emerging theme. Elsevier.

- Wallace, W., & Wang, Z. (2006). Solar energy in China: Development trends for solar water heaters and photovoltaics in the urban environment. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 26(2), 135–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467606286948

- Wang, Y., Song, Q., He, J., & Qi, Y. (2015). Developing low-carbon cities through pilots. Climate Policy, 15(sup1), S81–S103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1050347

- Xinhua News Agency. (2014). Jiangsu’s first village rooftop based solar PV energy system connect with grid. http://guangfu.bjx.com.cn/news/20140109/485451.shtml

- Xinhua News Agency. (2018). First national rooftop based solar PV energy village: Solar PV light rural areas. http://www.ocn.com.cn/touzi/chanye/201810/vtpkj26104019.shtml

- Yap, X.-S., & Truffer, B. (2019). Shaping selection environments for industrial catch-up and sustainability transitions: A systemic perspective on endogenizing windows of opportunity. Research Policy, 48(4), 1030–1047. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.10.002

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage.

- Zhang, S. (2016a). Analysis of DSPV (distributed solar PV) power policy in China. Energy, 98, 92–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2016.01.026

- Zhang, S. (2016b). Innovative business models and financing mechanisms for distributed solar PV (DSPV) deployment in China. Energy Policy, 95, 458–467. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.01.022

- Zhang, S., Andrews-Speed, P., & Ji, M. (2014). The erratic path of the low-carbon transition in China: Evolution of solar PV policy. Energy Policy, 67, 903–912. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.12.063

- Zhang, S., Andrews-Speed, P., & Li, S. (2018). To what extent will China’s ongoing electricity market reforms assist the integration of renewable energy? Energy Policy, 114, 165–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.12.002

- Zhang, S., & He, Y. (2013). Analysis on the development and policy of solar PV power in China. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 21, 393–401. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.01.002