ABSTRACT

In the 1980s, Switzerland’s Jura Arc region was a globally competitive ‘new industrial space’ in the Third Industrial Revolution’s flexible accumulation regime based on information and communication technology (ICT) and automation processes. Recently, this nowadays ‘old industrial space’ has been experiencing the implementation of Industry 4.0. Caught between the use of existing productive assets and the development of platform-based market ecosystems, this region illustrates the challenges inherent in implementing ‘forking innovation’, which requires the development not only of new business models, but also of collaborative and investment models in order to scale up and increase local value capture.

INTRODUCTION

Since the end of the 1980s, Switzerland’s Jura Arc region has been considered a typical post-Fordist model of locational value creation based on flexible production and external economies. Along with the emblematic technopole of Silicon Valley and the industrial districts of the Third Italy, this historic watchmaking, machine tool and microtechnology manufacturing region has demonstrated the regional competitiveness of ‘new industrial spaces’ (Scott, Citation1988) during the Third Industrial Revolution, which was based on information and communication technologies (ICT) and automation processes.

Riding the first wave of digitalization, the contemporary generalization of Internet-based services, devices, applications and networks, combined with recent developments such as the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), big data computing (big data) and blockchains, is paving the way for a Fourth Industrial Revolution (De Propris & Bailey, Citation2020; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2019; Schwab, Citation2017). How are current developments in digital technologies and digital business models challenging an incremental and small and medium-sized enterprise (SME)-based innovation system such as that found in Switzerland’s Jura Arc region? How may this old ‘new industrial space’ evolve to lead rather than follow in value creation and value capture under Industry 4.0 (I4.0)? And what can regional studies and economic geography learn from this region?

Regardless of whether current digital challenges enhance or revolutionize earlier digital transformations, in this article we argue that the primary issue that contemporary digital transformations raise for industrial regions concerns the emergence of a new value creation and value-capture paradigm. In contrast to the successful business models of Silicon Valley’s data platform companies, the I4.0 models currently being explored and experimented with in traditional European industrial regions remain ambiguous and uncertain (De Propris & Bailey, Citation2020).

The next section describes a heuristic shift in value creation and value capture from the current Industry 3.0 (I3.0), based on commodity sales, to the expected I4.0, based on data platform services. For industrial regions, and more particularly for SME-based regions, this transition not only challenges traditional business models, but also builds upon investment rationales that are motivated by the strategy to control a market ecosystem rather than a market value chain. Together with place-based experimentation, this transformation actuates and performs a new possible accumulation regime.

The third section examines current I4.0 transformations in the Jura Arc region. The transition to a new value-capture model presents a collective challenge that goes hand in hand with building a new narrative built on proofs of value. We introduce the term ‘forking innovation’ to describe the challenge of creating pathways in new platform-based market ecosystems in line with existing productive capital assets. Forking innovation requires the development not only of new business models, but also of collaborative and investing models in order to scale up and enhance value capture in the region.

Our empirical analysis draws upon three research projects conducted between 2018 and 2020. The first, ‘Definition and Evaluation of the Neuchâtel Canton Regional Policy Programme 2019–2023’ (hereafter, PROJECT-1), conducted with a regional authority, co-elaborated the strategy of a four-year regional innovation programme for industry and tourism. The second, ‘Diagnostics and Futures of Industrial Subcontractors in the Canton of Neuchâtel’ (PROJECT-2), conducted with a regional bank and a chamber of commerce, investigated the current economic challenges and future opportunities for regional manufacturing-supplier SMEs. The third, ‘Financing Industry 4.0: The Case of SMEs in the Jura Arc Region’ (PROJECT-3), consisted of exploratory research on regional industrial investment circuits.

From these three projects, we gathered information from 57 interviews and six focus groups. Around two-thirds of our discussion partners were representatives of regional industrial producers, suppliers and investors, while the rest were representatives of public or private organizations promoting collaborative innovations in the region (public authorities, innovation intermediaries, technology centres, professional organizations, leading experts). Complementary data on the state of industry in the region, ongoing projects and emerging initiatives were also collected from official statistics, regional and professional newspapers and web documentation.

This paper describes some of the challenges faced by industry in the Jura Arc region in its transition to I4.0, and it concludes with a research agenda that pivots on the cross-fertilization between business models, finance and transition literature, with the intention of renewing regional innovation studies on the economic sustainability of industrial sectors or regions and SMEs in an era characterized by digitalization and financialization.

DIGITALIZATION: TOWARDS A NEW VALUE-CAPTURE APPROACH FOR REGIONS

In regional studies and economic geography, the 1980s and 1990s are commonly described as an era of crisis for Fordism and the Keynesian welfare state that gave rise to a new accumulation regime based on flexible regional organization and innovative production within global value chains. In contrast to large manufacturing regions, ‘new industrial spaces’ (Scott, Citation1988) such as Silicon Valley and the Third Italy were proving successful in the new global economy. The former was the epitome of a science–industry technopole, pioneering disruptive enterprises and new global industries and markets. The latter demonstrated that industrial districts based on SMEs able to export high-quality products due to their incremental capacity to innovate in ever-changing markets could be successful as well. Features similar to those in these two ideal types were also found in other regions (Becattini et al., Citation2009; Benko & Lipietz, Citation2000; Castells & Hall, Citation1994; Porter, Citation1990; Ratti et al., Citation1997).

Over the years, these new industrial spaces have been remarkably influential in regional innovation studies and innovation geography. They have also been acknowledged as territorial innovation models characterized by their endogenous capacity to innovate on the basis of locational resources (e.g., formal and informal networks, specialized know-how, cumulative learning) (Doloreux et al., Citation2019; Lagendijk, Citation2006; Moulaert & Sekia, Citation2003).

Drawing mostly on a Marshallian understanding of innovation that is based on industrial and technological path dependences (Frenken & Boschma, Citation2007; Martin & Sunley, 2006), these models have subsequently been broadened in line with the general and intensified adoption of digital technologies in economy and society. They were, for instance, reconsidered in light of the immaterial economies (Cooke & Leydesdorff, Citation2006; Lazzeretti, Citation2008; Power & Scott, Citation2004), cross-sectoral fertilizations (Asheim et al., Citation2011; Boschma & Frenken, Citation2012) and global innovation systems (Binz & Truffer, Citation2017) that are facilitated and enhanced by the ongoing ICT transformations.

These conceptual enlargements (Shearmur et al., Citation2016) have mainly occurred from a production perspective. They point to the implications of ICT for the locational path creation of new sectors (e.g., new computer products and services), the locational combination of sectors (e.g., electronic products, computerized services, automated processes) and the local–global organization and flows of knowledge (e.g., instant digital communication channels). More than ever, the digital economy operates through combinatorial and multi-local territorial knowledge dynamics (Crevoisier & Jeannerat, Citation2009; Jeannerat & Crevoisier, Citation2016) within and across different technologies, industries, sectors and disciplines in globalized open innovation systems (OECD, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2017c, Citation2018, Citation2019).

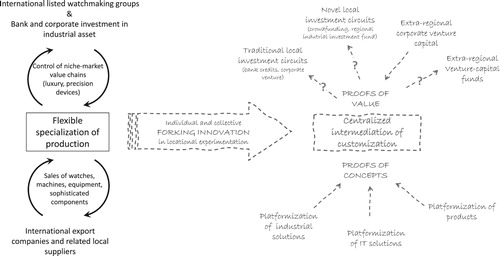

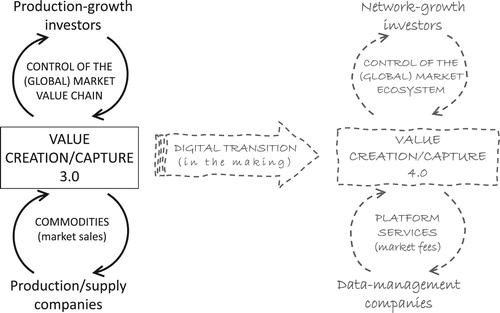

Nevertheless, contemporary digital businesses redefine not only how value is created across space, but also how and where value is captured in increasingly open and decentralized business models (Bharadwaj et al., Citation2013; Chesbrough et al., Citation2018). Digital technologies make possible new productive solutions, such as robotics, machine learning, and new ‘sharing’ and ‘on-demand’ economies that shift business opportunities away from the production of physical goods and services. Digital data have become a key raw material and are turning platform services into dominant businesses. In light of these changes, the digital transition is characterized by three major perspective shifts that are challenging the established territorial innovation model (): (1) a shift from product and process innovations to business model innovations; (2) a shift from production-growth investment to network-growth investment; and (3) a shift from innovation systems to system innovations.

Figure 1. Digital transition as a new value creation and value-capture paradigm in the making.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

From product and process innovations to business model innovations

Views differ regarding whether data will indeed turn out to be the central economic raw material in the future. Nevertheless, and regardless of the terminology used, crucial resources such as knowledge, capital and infrastructure are being invested in to ‘turn dataset into datasset’, with the aim of creating a new competitive advantage in today’s globalized economy (Birch & Muniesa, Citation2020). The digital economy seems to be shifting the focus from production and delivery companies that sell commodities in markets to data management companies that charge fees to access and operate in a market ecosystem they mediate through platform services (Kenney et al., Citation2019) ().

Apart from optimizing market mechanisms for traded goods and services, digital platform businesses fundamentally centralize and control both the infrastructure (i.e., data, networks and technology) and the rules according to which markets operate (Birch, Citation2020). More than the simple culmination of a lean management and mass-customization process fostered by digital automation, the Fourth Industrial Revolution also involves the rise of platform businesses based on digitalized networks and data processing that are becoming or attempting to become dominant revenue sources in their own right. These new businesses do more than provide innovative collaborative services and marketization facilities. Through their capacity to mediate and intermediate producer–user–influencer relations, they also change the nature of markets (Birch, Citation2020).

Apart from the productivity and quality gains that digitalization may provide, regional economies must also rely on a new value-capture paradigm (Bailey et al., Citation2018; Citation2019a; Vendrell-Herrero & Wilson, Citation2017). Still largely focused on production dynamics, regional innovation systems need to be understood as spatially constructed valuation and marketization systems (Berndt & Boeckler, Citation2012; Jeannerat & Kebir, Citation2016; Macneill & Jeannerat, Citation2016). It is also crucial to investigate not only the rise of new business models in specific regions and industries, but also how they shape the way the global economy operates. Silicon Valley is the exemplary case of this new local–global competitiveness. With its science–industry collaborations, pioneer entrepreneurs, ‘garage’ start-ups, breakthrough spin-offs and venture services, it is no longer the type of innovative region characteristic of a flexible accumulation regime. It is the success story of globally competitive business model innovation paradigm that is giving rise to a new platform capitalism (Kenney & Zysman, Citation2020; Langley & Leyshon, Citation2016; Srnicek, Citation2017).

In Europe, this new value-capture paradigm is currently understood as part of a ‘servitized’ I4.0 (Baines et al., Citation2014; Bellandi & Santini, Citation2019), for which a profitable business model still needs to be identified for traditional industries and industrial regions (Bellandi et al., Citation2019; Caruso, Citation2018). The economic challenges faced by established SMEs do not only include accessing extra-regional technologies and implementing them in new smart factory processes that make it possible to sell customized or decentralized production close to demand. They also include understanding how industrial servitized solutions can be scaled up to the global level and finding niche markets among global oligopolies (Bellandi et al., Citation2019). This multi-scalarity of value creation and value-capture 4.0 thus implies crucial interdependences between start-ups, established SMEs and large multinational companies sustaining revenue flows at the global level and anchoring them in the region (Bailey et al., Citation2018).

From investment in production growth to investment in network growth

Along with new forms of value capture in platformized markets, economic digitalization raises new avenues for value capture in investment markets as well. Platform capitalism, as pushed by Silicon Valley, builds on ‘winner-takes-all’ monopoly rent created by network effects (Birch, Citation2020; Kenney & Zysman, Citation2020; Srnicek, Citation2017). Investments are a means to grow the network upon which a platform business is based, and returns on investments are expected to result from control over a (global) market ecosystem rather than a (global) market value chain ().

In an era of abundant liquidity and access to funding, platform business model innovations have been used to encourage ‘high risk–high return’ investment in a fast-growing venture capital system, as demonstrated by the increasing number of ‘unicorn’ start-ups valued at over US$1 billion (Kenney & Zysman, Citation2019). Similarly, the promise of being able to capture platform service revenues in the long term maintains the capital market performance of digital platform companies such as Uber, even though they do not generate profit immediately (Langley & Leyshon, Citation2016). Digital giants such as Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft (GAFAM) are also key players in this venture capital system. Via strategic acquisitions and investments, these giants seek to enlarge and consolidate their own platform ecosystem and reinforce a platform-based rationale for capitalist investments (Kenney & Zysman, Citation2019).

Regional value capture of capital is governed by global financial markets (Corpataux et al., Citation2017). The development of a shareholder value logic has increased pressure on economic activities and regions (Pike, Citation2006). At the same time, regional connections with external investment circuits are key to growth in today’s financialized economy. The ways in which these connections are embedded across regions and nations depend on institutional contexts (Hall, Citation2013).

In Europe, where industrial investment has shifted from bank credit to financialized mechanisms governed by large listed corporations (Alessandri & Zazzaro, Citation2009; Appleyard, Citation2013; Corpataux et al., Citation2009, Citation2017; Klagge and Martin, Citation2005), regions and SMEs find it particularly challenging to invest in digital innovations when they lack ties to large corporate groups or venture capital channels devoted to start-ups (Feldman et al., Citation2019). On the one hand, large listed companies are able to invest in large-scale industrial experimentation and ambitious public–private research consortiums (De Propris & Bailey, Citation2020). On the other, start-up ventures can rely on dedicated venture and scale-up investment funds that are increasingly global (Kenney & Zysman, Citation2019).

As a result, further research is required to understand the local and global conditions that determine why some regions succeed in capturing capital for innovation while others do not (Feldman et al., Citation2019). In particular, the conditions that determine traditional industrial SMEs’ ability to partake in global financial networks remains under-researched. Regarding the ability to scale up value capture in commodity markets, it is also necessary to investigate the interrelations and interdependences between start-ups, SMEs and large companies in order to scrutinize local–global investments mechanisms (Coe et al., Citation2014).

From innovation systems to system innovations

Beyond the new value creation and value-capture mechanisms described above, the Fourth Industrial Revolution is a general process in the making involving both economy and society. Spatial variations in this transformative process are usually the result of local and national socio-institutional production, innovation and experimentation contexts that may provide new competitive advantages in a future globalized economy.

In European countries and regions, I4.0 seeks to address the future of production – of working and living in various sectors and regions that are more reliant on export-based manufacturing than the US service economy. I4.0 is meant to promote reflective experimentation that explores novel manufacturing and policy solutions (Audretsch, Citation2018; Bailey & De Propris, Citation2019; Berger, Citation2015; Bailey et al., Citation2019a; Bianchi & Labory, Citation2019; De Propris & Bailey, Citation2020). Acting as a servitized industry, I4.0 is expected to provide higher revenue streams and profit margins, in contrast to the decreasing value of products in business-to-business (B2B) transactions. It presents a vision of an economy that integrates digital technologies and transforms existing activities in order to achieve new societal goals, such as the backshoring of manufacturing (Ancarani et al., Citation2019; Pegoraro et al., Citation2020) and sustainable development (Stock & Seliger, Citation2016).

In this view, innovation involves not only technological change in an innovation system, but also a change of socio-economic paradigm (De Propris & Bailey, Citation2020). I4.0 is a scheme for an envisaged society rather than a regime that has already been realized. It has a heuristic and performative dimension that entails a full transformation of local production culture, collaborative practices and economic representations (De Propris & Bailey, Citation2020; Bailey & De Propris, Citation2020). I4.0 goes beyond striving to become competitive, as the new digitalized industrial techno-economic paradigm should exist to support sustainable development, not the other way around.

In this context of system innovation, the capacity for new path creation in regions and cities is crucial, and it must be addressed and investigated in the context of specific regional path dependencies that may, in turn, form the basis of new industrial branching (Martin & Sunley, Citation2015; Morgan, Citation2017; Strambach, Citation2010). The regional adoption of new digital technologies and the identification of new business models is multidimensional and multi-scalar (Bellandi et al., Citation2020a; Bellandi & Santini, Citation2019). In this local–global interplay, regional Marshallian conditions of production can be strengths or weaknesses. They may restrain or hamper the collective diffusion of new social practices and use of digital technologies in SME-based industrial regions (Bellandi et al., Citation2020b; Hervas-Oliver et al., Citation2019).

While experimentation and niche projects are a necessary step towards innovation, the diffusion and adoption of technological changes are a political struggle as well as a market issue. Regional industrial and innovation policy issues are transformative issues that are also political when it comes to value capture. The political nature of these issues goes hand in hand with the institutionalization of upper-scaled rules and standards that define what the digital transition should consist of and on what basis value creation and value capture should be distributed (Bailey et al., Citation2019b). In parallel, new regional path creation is embedded in multi-actor and multi-scalar innovation and transition networks (Binz et al., Citation2016; Boschma et al., Citation2017; Hassink et al., Citation2019; Trippl et al., Citation2018) that possess a strong political dimension as well. The structure of this global political path-creation network has yet to be fully understood, however, especially in traditional industrial regions (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019).

The next section addresses these various aspects of the digital transition as a new possible regional path of value creation and capture in the case of the Jura Arc region. It demonstrates the scope of the digital transition as a process in the making that challenges existing interrelations and interdependences between start-ups, SMEs and large companies, and it investigates the role of potential leaders and the collective benefits of this digital transition.

SWITZERLAND’S JURA ARC REGION AND THE FOURTH INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Regional I3.0: flexible specialization, export sales and niche market-value chains

With similar features to the industrial districts of the Third Italy, Switzerland’s Jura Arc region has been referred to as a ‘new industrial space’ since the 1980s (Scott, Citation1988). The active role of local actors in the re-emergence and repositioning of the region in a globalized market, most notably after a deep industrial crisis, has been discussed in the context of the issue of ‘innovative milieus’ (Crevoisier, Citation1993; Maillat et al., Citation1995).

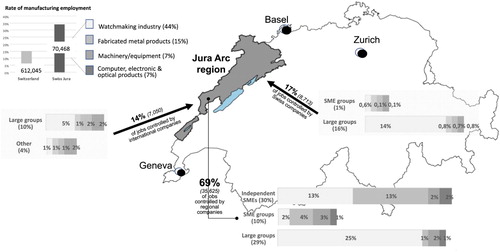

Relative to Switzerland as a whole, the region’s economy remains strongly industrial. In 2017, 34% of jobs in the region were in manufacturing, compared with around 15% for Switzerland (). With 44% of all manufacturing employment in the region, the watchmaking sector is the core industry in the region. Fabricated metal products (15%), machinery and equipment (7%), and computer, electronic and optical products (7%) are further significant sectors that together with watchmaking comprise three-quarters of the region’s manufacturing jobs.

Figure 2. The regional profile of the Jura Arc in terms of employment and control in the four main manufacturing sectors.

Sources: Swiss Federal Statistical Office (Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

Flexible specialization and external economies are not sufficient to explain the significance and competitiveness of the region’s industry. The industrial success of the Jura Arc region primarily relies on the ‘culturization’ of the watchmaking industry, which has driven the constant increase in exports and regional employment for the past two decades (Kebir & Crevoisier, Citation2008). The renaissance in mechanical watchmaking since the 2000s (Jeannerat & Crevoisier, Citation2011) has fuelled the growth in demand for precision components, machines and tools in the region. It has also given rise to large integrated and listed companies (Corpataux et al., Citation2009; Crevoisier & Quiquerez, Citation2005) that have progressively established control over the global market chain through the development of transnational production and retail networks (Jeannerat & Crevoisier, Citation2011; Theurillat & Donzé, Citation2017).

While SMEs were the main employers in the four sectors outlined above in the early 1990s (Crevoisier, Citation1993), today companies with over 250 employees represent more than 55% of jobs in those same sectors. Large companies are especially important in the watchmaking industry, which employs 25% (12,979) of all manufacturing workers and where new international key players have increasingly entered the business since the 2000s (e.g., LVMH in luxury watchmaking). Nonetheless, control over manufacturing employment in the four main sectors remains mostly regional or national. A total of 29% of manufacturing employment is controlled by large regional groups and 16% by national large groups, while 40% is controlled by regionally based independent SMEs and small SME groups ().

Large companies and some SMEs have become leading producers and sellers in global niche markets such as luxury watches, precision machines and specialized equipment. The majority of industrial SMEs are specialized suppliers of sophisticated components for regional lead producers and extra-regional buyers of precision devices, for instance in the automotive, aircraft, aerospace, medtech and biotech industries.

Still very much centred on its products and means of production, industry in the Jura Arc region is facing increasingly pressing challenges. On the one hand, business and industrial uncertainties are extremely high due to ongoing economic and social changes. Conjunctural crises follow upon each other in quick succession and cumulate in structural reconsiderations pushed by digital and sustainability transitions promoted by business and policy. On the other hand, production and innovation cycles have become drastically short and require project-based organization (flexibility and responsiveness) that is difficult to reconcile with the industrial imperatives of investment in heavy equipment, returns to scale and medium- and long-term amortization (PROJECT-2).

While large listed companies generate strategic cash flows and have access to financial markets to pursue research and development, independent SMEs and SME groups struggle to launch development projects that deviate from their incremental production trajectory and core business. Regional banks, a traditional source of investment in SMEs (Crevoisier, Citation1997; Dietrich et al., Citation2017), tend to rely on a risk analysis based mainly on existing markets and customer demand, and they consider new production and business developments involving new markets, prototypes and experimental solutions high risk.

While banks have provided SMEs with capital for equipment leasing (machines) and mortgages (factory extensions), they are an inappropriate source of capital for regional SMEs to finance prospective or path-breaking business developments. Moreover, as a result of the Swiss financial system’s shift towards investment banking and real estate, the proportion of bank credit dedicated to business investment has decreased over the last two decades, while mortgage credit to firms and households has increased significantly throughout the same period (PROJECT-3) (Swiss National Bank, Citation2020; Theurillat et al., Citation2010).

Regional I4.0: forking innovation in locational experimentation

Industry in the Jura Arc region is becoming increasingly aware of new digital challenges. In combination with other terms – including ‘IoT’, industry ‘as a service’, ‘machine learning’, ‘smart factory’, ‘data-driven value chain’ and ‘decentralized autonomous organization’ (DAO) – ‘I4.0’ has become a key concept through which industry players have reflected on the future of the regional economy. These players now recognize the risks and opportunities arising from the ongoing digitalization of economy and society (PROJECT-1) (Comtesse, Citation2019, Citation2020).

The challenges related to I4.0 are far from simple for regional industries that have to maintain their traditional production activity and business models that have proven profitable while imagining future digitalized services and revenue flows. The term ‘forking’ – used by information technology (IT) developers when giving an original source code a new development direction – is helpful in addressing SMEs’ innovation strategies. At the nexus of productive incrementation, traditionally applied to Marshallian SMEs, and market disruption, commonly associated with unicorn start-ups, ‘forking innovation’ can be defined as:

the innovation strategy consciously implemented by a company, a group of companies or a consortium to create a new development pathway on the basis of inherited products, production means, markets and competences.

Forking innovation is even more challenging for B2B component suppliers than for end-product companies because this type of innovation fundamentally redefines the understanding of a quality offering from individual products to collaborative services. While end-product companies dedicate more and more resources to positioning their brand in the market, suppliers and subcontractors are responsible for production and quality management to principals. Quality is therefore not a product attribute or production constraint, but a dynamic service to be sold as such to customers (PROJECT-2).

Forking innovation entails accessing and implementing new digital technologies in the development of new products and processes, and also imagining new business and collaborative models that challenge the traditional industrial approach and culture (Bellandi & Santini, Citation2019). The traditional culture of in-house production and research and development still dominates, and it generates fear of sharing ideas and projects with neighbouring companies that may be or become competitors (PROJECT-2).

While large private investments and state funding have been dedicated to experimental I4.0 programmes in European Union (EU) countries (Dosso, Citation2020), in Switzerland I4.0 is addressed from the bottom. Entrepreneurial projects are accompanied by new regional groups and associations of interest as well as expert, policy and opinion leaders. This constellation of innovative and institutional entrepreneurship combined with place-based leadership is a core ingredient of change (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020).

In the Jura Arc region, several experimental initiatives have recently been launched to develop new collaborative platforms that enable shared production and allow human resources to be more responsive to and proactive vis-à-vis market demand and customers. Such experimental projects are still rare. PROJECTS -1, -2 and -3 have identified most of them and depicted their main features. For example, the MicroLean Lab, a collaborative project that involves major regional watchmaking and other SMEs, experiments with IoT solutions to enable more decentralized and more customized microtechnology manufacturing. Another project by a regional start-up and a few supplier SMEs is developing an adaptive Smart Micro Factory that provides low-energy, automated flexible solutions.

Apart from these collective experiments, there are several other showcase initiatives in the region. For instance, Swiss Smart Factory, a model open factory, was launched in 2017 to enhance knowledge transfer and sharing in the field of I4.0 through emblematic success stories and advanced manufacturing solutions. Other promotional activities include a collective publication and the creation of a yearly award dedicated to pioneering SME entrepreneurs considered regional ‘Industry 4.0 Shapers’. These two regionally born initiatives promote local as well as national cases.

In this context, collective forking innovation exists in small experimental niches and is highly dependent on public spending. Large regional and national companies remain hesitant to invest heavily in collaborative digital projects. For SME firms or groups, participation in collaborative projects represents a more significant investment, and only a few of them are willing or able to engage financially. Public support mainly relies on regional and innovation policies. These policies do not permit funding for profit-making companies, but only for pre-competitive start-ups, inter-firm organizations and research centres. This often requires a complex financial ‘bricolage’ of financing and in-kind contributions from various sources. Thus, to benefit from state help, specific entrepreneurial skills are required, which makes forking innovation in the region highly dependent on start-uppers, researchers and collective project makers who have developed skills and expertise in such projects and benefit financially from them (PROJECT-3).

Platformization: technical proofs of concept in early stages

Many regional industrial players continue to believe that digital technologies will primarily reduce production costs and make production more flexible and responsive (automated, just in time, tailor-made, accurate and precise). Most ongoing experiments were conceived from this production-focused perspective, typical of the Third Industrial Revolution, according to which value is captured by the sale of goods. Services are means to sell these goods and ensure their quality (e.g., quality control, marketing, retail and after-sale).

Value capture among leading data management companies today is the other way around: goods are a means to sell platform services. Manufacturers, whose value capture is based on their traditional existing assets (product, production means, know-how, markets), find it difficult to adopt this perspective. While this ‘platformization’ of economic revenue is more advanced in traditional service sectors (e.g., restaurant, retail, hotel booking), it is a quickly growing trend in any industry that will reconfigure global value capture (Srnicek, Citation2017).

In the current experimentation occurring in the Jura Arc region, three different kinds of platformization processes are in their early stages (). First, the platformization of products involves the development of a novel market offering developed in addition to, as a complement to or as a replacement of a traditional manufactured good. Digivitis, the aforementioned platform to improve the management of vineyards, is a prime example. This platform is conceived as a new offering with its own revenue model (PROJECT-1).

Second, the platformization of industrial solutions promotes more flexible and more responsive collaborative production processes. An example is the Factory 5 platform developed in a neighbouring region by an industrial start-upper for a small milling machine engineered and patented in the Jura Arc region. This platform offers an integrative software solution to provide decentralized and smart coordination between complementary machines and/or factories to increase efficiency and the ability to respond quickly to customer demand. Another example is Human Hub, a human-resources platform to facilitate companies’ ability to share key competences with each other and manage volatile production conditions more efficiently (PROJECT-2).

Third, the platformization of IT solutions is led by regional digital business services that are shifting from being IT providers to companies to developers of integrated data management solutions. Whether hardware or software suppliers, IT businesses have to become proactive co-developers with industrial companies of digital ecosystems that integrate data mining, data sharing, data securing, data valuing and software updating. This type of platformization creates new opportunities for inter-firm collaborative platforms, and it is illustrated by MUSE. Initiated by a regional IT start-up and co-developed with the main regional machine-tool producer, five SMEs and two regional research centres, MUSE is developing a centralized platform to enable remote updating and repair services for machines sold by regional producers (PROJECT-3).

These pioneering projects offer collective opportunities that go beyond individual initiatives and promote a shift from a production-based perspective focused on manufactured goods to a market-ecosystem perspective focused on responsive solutions. From this latter perspective, the region is a ‘smart market’ able to implement new experimental digital solutions. However, these current experiments mostly remain technical proofs of concept that draw attention to productive solutions rather to new models of value capture (PROJECT-1).

To become viable, these nascent platforms must acquire partners that believe in the future of decentralized industrial processes and offerings. The quest for more ‘network effects’ is even more pressing, considering that foreign industrial platforms may enter the competition. For example, advanced German platforms, which are currently still focused on national companies, may soon be in a position to offer industrial firms in the Jura Arc similar platform services as that being developed by the MUSE project.

DISCUSSION: THE NEED FOR PROOFS OF VALUE TO SCALE UP A NEW ‘SURTRAITANCE’

The French term surtraitance, which can be translated as ‘supercontracting’ in contrast to ‘subcontracting’ (sous-traitance in French), has recently been adopted by regional I4.0 opinion leaders to address the new digital business opportunities for industry. In contrast to GAFAM’s current business models, supercontracting involves becoming the lead organizer of an industrial market ecosystem instead of a simple supplier in a production chain. This model involves the creation and capture of value by a centralized intermediation of customization processes that applies to both B2C and B2B markets ().

For now, however, the aforementioned projects remain confined to limited firm ecosystems and have failed to attract scale-up investments. To convince a broader range of companies and investors to scale up and embrace the Fourth Industrial Revolution in the Jura Arc, a concrete ‘proof of value’ is needed.

Paradoxically, the region’s still quite remarkable industrial competitiveness could stifle this search for a new proof of value. In more deindustrialized regions in Europe, I4.0 appears to be a clear opportunity to restore industrial competitiveness (Ancarani et al., Citation2019; Bailey & De Propris, Citation2014). The still successful industrial firms of the Jura Arc region, in contrast, see what they have to lose more clearly than what they have to gain from such a change. In this context, the proof of value faces two interdependent challenges.

First, the nascent platforms must enable their users to monetize a new or more efficient service. As showed by Corò and Volpe (Citation2020) in the Veneto region of Italy, profitability ratios are not significantly higher for early adopters of I4.0 technologies. While long-established companies have proven to be profitable in the selling of specialized niche products or components, they are reluctant to implement digital solutions that go beyond optimized production processes and entail new ways of monetizing services that are not (yet) part of their core competences. They also find it difficult to imagine that inter-firm sharing platforms could enhance their development capacity.

Integrating different firms and operations into a corporate group is still often considered the most efficient way to exploit synergies for more advanced products or more complex solutions for customers. Vertical integration also remains more attractive for financial investors. For instance, a quite young regional suppliers’ group has become large enough to attract one the world’s largest private equity funds. With the backing of this investor, this group plans to become a global supplier of precision components for diverse markets, in particular medtech.

The second challenge is that nascent platforms must generate viable revenue for their developers (e.g., access fees). Usually developed as start-ups, these platforms find it difficult to position themselves as strategic gatekeepers attracting more partners and investors. Large established regional companies in the watchmaking and machine-tool industries that could afford to scale up investments do not do so because they are already at the centre of their markets and are still uncertain about the possible effects of the emerging platforms on their centrality. Furthermore, current bottom-up innovation policy in the region is far from the major I4.0 public–private investment plans in leading industrial export-based countries such as Germany and China, where a move to platform business has been promoted heavily in recent years.

As previously explained, it is rare for traditional local investment sources such as banks and venture capital from large regional groups to invest in forking innovation. It is also still rare for extra-regional venture capital to invest in regional digital start-ups. Local direct investment from successful (industrial and non-industrial) entrepreneurs, members of boards of directors, industrial families and interdependent partner firms is possible, but its scale and scope are often limited to the early stages of development. Novel local investment circuits such as crowdfunding and a new regional industrial investment fund are also being considered by some industrial stakeholders, but the former solution seems limited to providing capital for initial developments, while the latter is unlikely to prove a sustainable source of capital.

Very recently, the Factory 5 platform has been integrated into a German industrial group, and a key IT firm involved in one of the projects referred to above has obtained financial support from an extra-regional Swiss industrial company. These developments demonstrate, first, the potential of such platforms built upon technological developments or IT solutions initiated in the Jura Arc region and, second, that it is possible in at least some circumstances to raise capital. A still open question is how to ensure that external investments will be anchored locally and help sustain regional development.

Between the ‘high risk–high return’ promised by unicorn start-ups and the ‘lower risk–lower return’ guaranteed by mortgage credit, the forking innovation undertaken by industrial start-ups and SMEs remains unable to convince scale-up investors. Forking innovation falls somewhere between the ‘great’ disruptive innovations of Silicon Valley and the ‘small’ adaptive innovations of the Jura Arc region’s manufacturing industry, and remains in the blind spot of both the market and capital value-capture 4.0, at least for the time being.

CONCLUSIONS: FOR A VALUE (CAPTURE) AGENDA

In recent years, industrial stakeholders in Switzerland’s Jura Arc region have increasingly adopted I4.0 rhetoric to talk about their future. This rhetoric is inspired by exemplary cases in other regions and countries, in particular digital business in the United States and smart manufacturing solutions in Germany. It is also being promoted by the federal government’s Digital Switzerland strategy, which was launched in 2018 to increase social awareness of the digital transition and foster this transition in every policy sector.

Direct stakeholders in the changing industrial paradigm, regional policymakers, key companies and opinion leaders see in the historic and dense industrial conditions of the Jura Arc the potential to become leading players in rather than followers of the Fourth Industrial Revolution currently underway. The analysis presented here demonstrates that it will not be easy to fulfil this aspiration. As already noted by other scholars, the Fourth Industrial Revolution requires traditional industrial companies in district-like regions to consider innovation anew, from both a path-dependent and a path-creation perspective (Bellandi & Santini, Citation2019; Bianchi & Labory, Citation2019; Bramanti, Citation2019; Hervas-Oliver et al., Citation2019).

Along with ongoing experimentation and the development of dedicated policy, this forking innovation needs a new innovation narrative that differs from the dominant one. To be convincing, this new story must convey not only a technological rationale, but also a value rationale. It needs to explain why already profitable companies should collectively embrace I4.0, what the evaluation criteria for forking innovations should be, what additional profit can be made from developing collaborative solutions and what investment criteria a regional industrial investment fund should adopt for the manufacturing sector.

These issues lie at the crossroad of innovation, transition and financial geography, and they constitute the backbone of strategic agendas for industrial stakeholders, policymakers and regional studies. These agendas should complement each other in contributing to renewed territorial innovation models while reconsidering traditional schemes inherited from the Third Industrial Revolution. In addition to recent critical calls to improve the multi-agency, multi-scalarity and collective ideation of the future (Binz et al., Citation2016; Boschma et al., Citation2017; Hassink et al., Citation2019), we argue that the question of value should be at the centre of a consolidated regional studies programme, not as a consequence of innovation, but as its driver (Jeannerat & Kebir, Citation2016). This question of value is also a political issue of performing the rules of a new accumulation regime and rent profits (Birch & Muniesa, Citation2020; Feldman et al., Citation2019).

The old European ‘new industrial spaces’ of the 1980s, so distinct from the unicorn start-ups, winner-takes-all companies and large I4.0 consortiums of other parts of the world, should contribute to analysing and understanding the local–global challenges of both digitalization and financialization. We have argued that these issues can be addressed together through the general question of value creation, and foremost of value capture, which places renewed focus on inter-firm interdependences (Bailey et al., Citation2018, 2019) and diffusion-oriented industrial innovation policy (Kitson, Citation2019). Furthermore, and as stressed by previous studies, value-capture 4.0 must go beyond mainstream technological innovation and marketization discourses. It must include the aspiration for sustainability that should drive the business and investment rationales of a digital transition to an ‘I4.0+’ (De Propris & Bailey, Citation2020).

In the Jura Arc region, I4.0+ is still regarded from the narrow perspective of mobility and energy savings enabled by a decentralized micro-factory paradigm. However, it is possible to imagine a more societal and cultural approach to sustainability that goes beyond this narrow perspective and exploits the value of past successful innovations. Since the 1980s, the watchmaking industry in the Jura Arc region has been able to align technological innovation with cultural innovations based on design, fashion, social distinction, authenticity and exclusiveness with extraordinary success (Jeannerat & Crevoisier, Citation2011). In a similar way, I4.0+ contains the potential for the confluence between a new societal transformation and business models with a strong cultural dimension. Combining ongoing experimentation with the investment and marketing competences of leading watchmaking companies could result in a new regional value leadership and an alternative I4.0 story.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Particular thanks are extended to the research partners of the projects ‘Definition and Evaluation of the Neuchâtel Canton Regional Policy Programme 2019–2023’, ‘Diagnostics and Futures of Industrial Subcontractors in the Canton of Neuchâtel’, and ‘Financing Industry 4.0: The Case of SMEs in the Jura Arc Region’: Jean-Luc Bochatay, Marie-Laure Chapatte, Caroline Choulat, Olivier Crevoisier, Patricia Da Costa, Ariane Huguenin, Florian Németi and Victoriya Salomon. The authors are also thankful to those who commented on a previous version of this paper, in particular Max Monti, Daniel Moure and the three anonymous referees.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. Of course, responsibility for the interpretation proposed in this paper remains entirely that of the authors alone.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Alessandri, P., & Zazzaro, A. (2009). Bank’s localism and industrial districts. In G. Becattini, M. Bellandi, & L. De Propris (Eds.), A handbook of industrial districts (pp. 471–482). Edward Elgar.

- Ancarani, A., Di Mauro, C., & Mascali, F. (2019). Backshoring strategy and the adoption of Industry 4.0: Evidence from Europe. Journal of World Business, 54(4), 360–371. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2019.04.003

- Appleyard, L. (2013). The geographies of access to enterprise finance: The case of the West Midlands, UK. Regional Studies, 47(6), 868–879. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.748979

- Asheim, B., Boschma, R., & Cooke, P. (2011). Constructing regional advantage: Platform policies based on related variety and differentiated knowledge bases. Regional Studies, 45(7), 893–904. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2010.543126

- Audretsch, D. (2018). Developing strategies for industrial transition. Background paper for an OECD/EC Workshop on 15 October 2018 within the workshop series ‘Broadening innovation policy: New insights for regions and cities’, Paris.

- Bailey, B., Pitelis, C., & Tomlinson, P. R. (2019a). Strategic management and regional industrial strategy: Cross-fertilization to mutual advantage. Regional Studies, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1619927

- Bailey, D., & De Propris, L. (2014). Manufacturing reshoring and its limits: The UK automotive case. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 7(3), 379–395. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu019

- Bailey, D., & De Propris, L. (2019). Industry 4.0, regional disparities and transformative industrial policy. Regional Studies Policy Impact Books, 1(2), 67–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2578711X.2019.1621102

- Bailey, D., & De Propris, L. (2020). Industry 4.0 and transformative regional industrial policy. In L. De Propris, & D. Bailey (Eds.), Industry 4.0 and regional transformations (pp. 238–252). Routledge.

- Bailey, D., Glasmeier, A., Tomlinson, P., & Tyler, P. (2019b). Industrial policy: New technologies and transformative innovation policies? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 12, 169–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsz018

- Bailey, D., Pitelis, C., & Tomlinson, P. R. (2018). A place-based developmental regional industrial strategy for sustainable capture of co-created value. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 42(6), 1521–1542. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bey019

- Baines, T., Lightfoot, H., Palie, S., & Fletcher, S. (2014). Servitization of the manufacturing firm: Exploring the operations practices and technologies that deliver advanced services. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 24(4), 637–646. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17410381311327431

- Becattini, G., Bellandi, M., & De Propis, L. (Eds.). (2009). A handbook of industrial districts. Edward Elgar. doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781007808

- Bellandi, M., Chaminade, C., & Plechero, M. (2020a). Transformative paths, multi-scalarity of knowledge bases and Industry 4.0. In L. De Propris, & D. Bailey (Eds.), Industry 4.0 and regional transformations (pp. 62–83). Routledge.

- Bellandi, M., De Propris, L., & Santini, E. (2019). Industry 4.0+ challenges to local productive systems and place-based integrated industrial policies. In P. Bianchi, & S. Labory (Eds.), Transforming industrial policy for the digital Age: Production, territories and structural change (pp. 201–218). Edward Elgar.

- Bellandi, M., & Santini, E. (2019). Territorial servitization and new local productive configurations: The case of the textile industrial district of Prato. Regional Studies, 53(3), 356–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1474193

- Bellandi, M., Santini, E., Vecciolini, C., & De Propris, L. (2020b). Industry 4.0: Transforming local productive systems in the Tuscany region. In L. De Propris, & D. Bailey (Eds.), Industry 4.0 and regional transformations (pp. 84–96). Routledge.

- Benko, G., & Lipietz, A. (2000). La richesses des régions. La nouvelle géographie socio-économique. Presse Universitaire de France.

- Berger, R. (2015). The digital transformation of industry. Roland Berger Strategy Consultants. A European study commissioned by the Federation of German Industries.

- Berndt, C., & Boeckler, M. (2012). Geographies of marketization. In T. J. Barnes, J. Peck, & E. Sheppard (Eds.), The new companion to economic geography (pp. 2199–2212). Wiley Blackwell.

- Bharadwaj, A., El Sawy, O. A., Pavlou, P. A., & Venkatraman, N. (2013). Digital business strategy: Toward a next generation of insights. MIS Quarterly, 37(2), 471–482. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37:2.3

- Bianchi, P., & Labory, S. (2019). Regional industrial policy for the manufacturing revolution: Enabling conditions for complex transformations. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 12(2), 233–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsz004

- Binz, C., & Truffer, B. (2017). Global innovation systems – A conceptual framework for innovation dynamics in transnational contexts. Research Policy, 46(7), 1284–1298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.05.012

- Binz, C., Truffer, B., & Coenen, L. (2016). Path creation as a process of resource alignment: Industry formation for on-site water recycling in Beijing. Economic Geography, 92(2), 172–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1103177

- Birch, K. (2020). Technoscience rent: Toward a theory of rentiership for technoscientific capitalism. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 45(1), 3–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243919829567

- Birch, K., & Muniesa, F. (2020). Datassets: Assetizing and marketizing personal data. In K. Birch, & F. Muniesa (Eds.), Turning things into assets (pp. 75–95). MIT Press.

- Boschma, R., Coenen, L., Frenken, K., & Truffer, B. (2017). Towards a theory of regional diversification: Combining insights from evolutionary economic geography and transition studies. Regional Studies, 51(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1258460

- Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2012). Technological relatedness and regional branching. In H. Bathelt, M. P. Feldman, & D. F. Kogler (Eds.), Beyond territory. Dynamic geographies of knowledge creation, diffusion and innovation (pp. 64–81). Routledge.

- Bramanti, A. (2019). New manufacturing trends in developed regions: Three delineations of new industrial policies, ‘Phenix Industry’, Industry 4.0’ and ‘Smart Specialisation’. In H. Hilpert (Ed.), Diversities of innovation (pp. 239–274). Routledge.

- Caruso, L. (2018). Digital innovation and the fourth industrial revolution: Epochal social changes? AI & Society, 33(3), 379–392. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-017-0736-1

- Castells, M., & Hall, P. G. (1994). Technopoles of the world: The making of 21st century industrial complexes. Routledge.

- Chesbrough, H., Lettl, C., & Ritter, T. (2018). Value creation and value capture in open innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 35(6), 930–938. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12471

- Coe, N., Lai, K., & Wojcik, D. (2014). Integrating finance into global production networks. Regional Studies, 48(5), 761–777. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.886772

- Comtesse, X. (Ed.). (2019). Industry 4.0: The shapers. Georg.

- Comtesse, X. (Ed.). (2020). Résilience et innovation. Penser. Georg.

- Cooke, P., & Leydesdorff, L. (2006). Regional development in the knowledge-based economy: The construction of advantage. Journal of Technology Transfer, 31(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-005-5009-3

- Corò, G., & Volpe, M. (2020). Driving factors in the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies: An investigation of SMEs. In L. De Propris, & D. Bailey (Eds.), Industry 4.0 and regional transformations (pp. 112–132). Routledge.

- Corpataux, J., Crevoisier, O., & Theurillat, T. (2009). The expansion of the finance industry and its impact on the economy: A territorial approach based on Swiss pension funds. Economic Geography, 85(3), 313–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01035.x

- Corpataux, J., Crevoisier, O., & Theurillat, T. (2017). The territorial governance of the financial industry. In R. Martin, & J. Pollard (Eds.), Handbook on the geographies of money and finance (pp. 69–88). Edward Elgar.

- Crevoisier, O. (1993). Spatial shifts and the emergence of innovative milieux: The case of the Jura region between 1960 and 1990. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 11(4), 419–430. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/c110419

- Crevoisier, O. (1997). Financing regional endogenous development: The role of proximity capital in the age of globalization. European Planning Studies, 5(3), 407–415. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654319708720407

- Crevoisier, O., & Jeannerat, H. (2009). Territorial knowledge dynamics: From the proximity paradigm to multi-location milieus. European Planning Studies, 17(8), 1223–1241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310902978231

- Crevoisier, O., & Quiquerez, F. (2005). Inter-regional corporate ownership and regional autonomy: The case of Switzerland. The Annals of Regional Science, 39(4), 663–689. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-005-0017-7

- De Propris, L., & Bailey, D. (2020). Disruptive Industry 4.0+: key concepts. In L. De Propris, & D. Bailey (Eds.), Industry 4.0 and regional transformations (pp. 1–23). Routledge.

- Dietrich, A., Wernli, R., & Duss, C. (2017). Etude sur le financement des PME en Suisse, Institut pour les services financiers. Haute école de Lucerne.

- Doloreux, D., Gaviria de la Puerta, J., Pastor-López, Igone Porto Gómez, I., Sanz, B., & Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, J. M. (2019). Territorial innovation models: To be or not to be, that’s the question. Scientometrics, 120(3), 1163–1191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03181-1

- Dosso, M. (2020). Technological readiness in Europe: EU policy perspectives on Industry 4.0. In L. De Propris, & D. Bailey (Eds.), Industry 4.0 and regional transformations (pp. 214–237). Routledge.

- Feldman, M., Guy, F., & Iammarino, S. (2019). Regional income disparities, monopoly & finance. Working Paper NO. 43, October. Birkbeck, University of London.

- Frenken, K., & Boschma, R. (2007). A theoretical framework for evolutionary economic geography: Industrial dynamics and urban growth as a branching process. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(5), 635–649. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm018

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Hall, S. (2013). Geographies of money and finance III: Financial circuits and the ‘real economy’. Progress in Human Geography, 37(2), 285–292. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512443488

- Hassink, R., Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2019). Towards a comprehensive understanding of new regional industrial path development. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1636–1645. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Hervas-Oliver, J.-L., Estelles-Miguel, S., Mallol-Gasch, G., & Boix-Palomero, J. (2019). A place-based policy for promoting Industry 4.0: The case of the Castellon ceramic tile district. European Planning Studies, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1642855

- Jeannerat, H., & Crevoisier, O. (2011). Non-technological innovations and multi-local territorial knowledge dynamics in the Swiss watch industry. International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development, 3(1), 26–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIRD.2011.038061

- Jeannerat, H., & Crevoisier, O. (2016). Editorial: From ‘territorial innovation models’ to ‘territorial knowledge dynamics’: On the learning value of a new concept in regional studies. Regional Studies, 50(2), 185–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1105653

- Jeannerat, H., & Kebir, L. (2016). Knowledge, resources and markets: What economic system of valuation? Regional Studies, 50(2), 274–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.986718

- Kebir, L., & Crevoisier, O. (2008). Cultural resources and the regional development: The case of the cultural legacy of watchmaking. In P. Cooke, & L. Lazzeretti (Eds.), Creative cities, cultural clusters and local economic development (pp. 48–69). Edward Elgar.

- Kenney, M., Petri Rouvinen, P., Timo Seppälä, T., & Zysman, J. (2019). Platforms and industrial change. Industry and Innovation, 26(8), 871–879. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2019.1602514

- Kenney, M., & Zysman, J. (2019). Unicorns, Cheshire cats, and the new dilemmas of entrepreneurial finance. Venture Capital, 21(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2018.1517430

- Kenney, M., & Zysman, J. (2020). The platform economy: Restructuring the space of capitalist accumulation. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsaa001

- Kitson, M. (July 2019). Innovation policy and place: A critical assessment. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 12(2), 293–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsz007

- Klagge and Martin, R. (2005). Decentralized versus centralized financial systems: Is there a case for local capital markets? Journal of Economic Geography, 5(4), 387–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbh071

- Lagendijk, A. (2006). Learning from conceptual flow in regional studies: Framing present debates, unbracketing past debates. Regional Studies, 40(4), 385–399. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400600725202

- Langley and Leyshon. (2016). Platform capitalism: The intermediation and capitalisation of digital economic circulation. Finance and Society, 3(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2218/finsoc.v3i1.1936

- Lazzeretti, L. (2008). The cultural districtualization model. In P. Cooke, & L. Lazzeretti (Eds.), Creative cities, cultural clusters and economic development (pp. 93–120). Edward Elgar.

- MacKinnon, D., Dawley, S., Pike, A., & Cumbers, A. (2019). Rethinking path creation: A geographical political economy approach. Economic Geography, 95(2), 113–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Macneill, S., & Jeannerat, H. (2016). Beyond production and standards: Toward a status market approach to territorial innovation and knowledge policy. Regional Studies, 50(2), 245–259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1019847

- Maillat, D., Lecoq, B., Nemeti, F., & Pfister, M. (1995). Technology districts and innovation: The case of the Swiss Jura Arc. Regional Studies, 29(3), 251–263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409512331348943

- Martin, R., Berndt, C., Klagge, B., & Sunley, P. (2005). Spatial proximity effects and regional equity gaps in the venture capital market: Evidence from Germany and the United Kingdom. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 37(7), 1207–1231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/a3714

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2015). Towards a developmental turn in evolutionary economic geography? Regional Studies, 49(5), 712–732. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.899431

- Morgan, K. (2017). Nurturing novelty: Regional innovation policy in the age of smart specialization. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(4), 569–583. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X16645106

- Moulaert, F., & Sekia, F. (2003). Territorial innovation models: A critical survey. Regional Studies, 37(3), 289–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340032000065442

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2017a). Key issues for the digital transformation in the G20. Report prepared for a joint G20 German Presidency/OECD conference, Berlin, Germany, 12 January 2017.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2017b). The future of global value chains: Business as usual or a new normal. OECD Science, Technology and Innovation Policy Papers No. 41, July.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2017c). The next production revolution: Implications for governments and business. OECD Publ. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264271036-en

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2018). Digitalisation, business models and value creation. In Tax challenges arising from digitalisation – Interim report 2018: Inclusive framework on BEPS. OECD Publ. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264293083-4-en

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2019). Going digital: Shaping policies, improving lives. OECD Publ. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264312012-en

- Pegoraro, D., De Propris, L., & Chidlow, A. (2020). De-globalisation, value chains and reshoring. In L. De Propris, & D. Bailey (Eds.), Industry 4.0 and regional transformations (pp. 152–175). Routledge.

- Pike, A. (2006). ‘Shareholder value’ versus the regions: The closure of the Vaux brewery in Sunderland. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(2), 201–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbi005

- Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. Billing & Sons.

- Power, D., & Scott, A. J. (Eds.). (2004). Cultural industries and the production of culture. Routledge.

- Ratti, R., Bramanti, A., & Gordon, R. (Eds.). (1997). The dynamics of innovative regions: The GREMI approach. Ashgate.

- Schwab, K. (2017). The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Penguin.

- Scott, A. (1988). New industrial spaces. Pion.

- Shearmur, R., Carrincazeaux, C., & Doloreux, D. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook on the geographies of innovation. Edward Elgar.

- Srnicek, N. (2017). Platform capitalism. Polity.

- Stock T., & Seliger, G. (2016). Opportunities of sustainable manufacturing in Industry 4.0. Procedia CIRP, 40, 536–541. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2016.01.129

- Strambach, S. (2010). Path dependence and path plasticity: The co-evolution of institutions and innovation – The German customized business software industry. In R. Boschma, & R. Martin (Eds.), The handbook of evolutionary economic geography (pp. 406–431). Edward Elgar.

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office. (2017a). Structural business statistics.

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office. (2017b). Business group statistics.

- Swiss National Bank. (2020). Housing mortgages, credits and mortgages to firms: Online statistics. https://data.snb.ch/en/topics/banken#!/cube/bakredsekbrlzm

- Theurillat, T., Corpataux, J., & Crevoisier, O. (2010). Property sector financialization: The case of Swiss pension funds (1992–2005). European and Planning Studies, 18(2), 189–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310903491507

- Theurillat, T., & Donzé, P.-Y. (2017). Retail networks and real estate: The case of Swiss luxury watches in China and Southeast Asia. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 27(2), 126–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2016.1251954

- Trippl, M., Grillitsch, M., & Isaksen, A. (2018). Exogenous sources of regional industrial change: Attraction and absorption of non-local knowledge for new path development. Progress in Human Geography, 42(5), 687–705. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517700982

- Vendrell-Herrero, F., & Wilson, J. R. (2017). Servitization for territorial competitiveness: Taxonomy and research agenda. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 27(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-02-2016-0005