ABSTRACT

Evolutionary economic geography has sought to understand the development of regional industrial pathways but tended to neglect both the multiscalarity of economic development and the role of institutional change. The concept of coevolution seeks to bridge this gap but is still too vague for empirical application. Understanding the interactions between path development and institutional change in regional economies and on higher spatial scales requires retheorizing coevolution along the dimensions of institutional–industrial coevolution, path multiplicity and multiscalarity. The article proposes such a retheorized concept of coevolution by integrating concepts of path development, institutions, institutional change, institutional entrepreneurship, institutional work and nestedness.

INTRODUCTION

The paradigm of evolutionary economic geography is opening up to other schools of thought. In particular, institutional approaches have been identified as useful complements for evolutionary perspectives on regional development (Benner, Citation2020c; Essletzbichler & Rigby, Citation2007; Grillitsch, Citation2015; Harris, Citation2020; Hassink et al., Citation2014, Citation2019; MacKinnon et al., Citation2009; Martin, Citation2000; Strambach, Citation2010; Trippl et al., Citation2018).

When integrating institutional ideas into the evolutionary paradigm, the concept of coevolution (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019; Murmann, Citation2013; Schamp, Citation2009; Strambach, Citation2010; Ter Wal & Boschma, Citation2011) comes to mind. The idea that evolutionary processes do not refer to industrial patterns only but to institutions quite naturally leads to a perspective of analysing the interrelationships between industrial and institutional dynamics. As Gong and Hassink (Citation2019) stress, looking at how industries and institutions coevolve provides a basis for contextualization and complements research on the institutional context of regional economies (e.g., Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Glückler, Citation2020) with an evolutionary perspective. However, the concept of coevolution has so far unfolded limited relevance for empirical research (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019). A reason for this limited uptake so far may be that how precisely industries and institutions interact and on which scale, how industrial and institutional change affects coevolutionary processes, and how coevolution relates to forms of positive and negative path development (Blažek et al., Citation2020; Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Hassink et al., Citation2019; Isaksen, Citation2015; Isaksen et al., Citation2018) remains largely vague. Building on the research gaps identified by Gong and Hassink (Citation2019), this article argues that existing conceptualizations of coevolution, while advancing our understanding of complex evolutionary processes in regional economies, remain too vague to be applied empirically and need to be refined by combining the dimension of industrial–institutional coevolution not only with multiscalarity (i.e., distinguishing different spatial scales) but also with path multiplicity (i.e., distinguishing between pathways of different industries in a regional economy) in a multidimensional conceptual framework.

Following Gong and Hassink (Citation2020), theory-building in economic geography in a critical–realist perspective (Sayer, Citation1992, Citation2000) attempts to achieve abstraction from context, or what Bathelt and Glückler (Citation2003, p. 128) call ‘de-contextualization’, through repeated retheorizing that makes concepts applicable to a wider range of contexts. Gong and Hassink (Citation2020, p. 482) explicitly refer to coevolution as a concept that has not yet been successfully retheorized as it ‘still lacks enough context-sensitive empirical research to adapt it well and convincingly to questions in economic geography’. Such empirical research, however, presupposes a concept of coevolution better connected to existing and empirically grounded concepts of institutional and evolutionary economic geography.

By bringing together coevolution with the regional industrial path development approach and by integrating concepts of institutional change, institutional entrepreneurship and institutional work, and nestedness, the article sets out to suggest a retheorized concept of coevolution. The article’s motivation is thus to propose a conceptual framework that builds on existing accounts of coevolution, extends the concept, and addresses the role of coevolving industrial and institutional patterns in path development. While industrial evolution can be observed by looking at the population of firms in a sector or region (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019) and conceptualized as path development or cluster evolution, the institutional side of coevolution is still little understood, owing to the considerable ambiguity in defining institutions, the concomitant difficulties of observing them, and a certain obscurity of the role of agency in institutional change (e.g., Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Gertler, Citation2010; Hodgson, Citation2006; Jepperson, Citation1991; Lawrence et al., Citation2009; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013; Scott, Citation2014; Seo & Creed, Citation2002). Hence, to pursue its aim of retheorizing coevolution, this article focuses to a large degree on discussing these unresolved institutional questions.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. It starts by discussing theoretical building blocks for coevolution before proposing a multipath and multiscalar conceptual framework. Finally, it draws conclusions for further research.

PATH DEVELOPMENT

Following Martin’s (Citation2010) view of regional evolutionary paths as a continuous process instead of a more or less stable result of single events (see also Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001; Martin & Sunley, Citation2006), the literature on regional industrial path development (Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Isaksen et al., Citation2018, Citation2019; Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2017; Martin & Sunley, Citation2006; Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2013) identified six forms of positive path development (path extension, path branching, path diversification, path creation, path importation and path upgrading). Blažek et al. (Citation2020) add three forms of negative path development (path contraction, path downgrading and path delocalization) that can ultimately result in path disappearance. Critically, the path development literature stresses the role of both local and non-local impacts (Binz et al., Citation2016; Binz & Truffer, Citation2017; Dawley et al., Citation2015; Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Hassink et al., Citation2019; Heiberg et al., Citation2020; Isaksen et al., Citation2018; Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2017; MacKinnon, Citation2012; Miörner & Trippl, Citation2019; Trippl et al., Citation2018).

A different but complementary strand of the literature looks at how clusters evolve. For example, Bergman (Citation2008) and Menzel and Fornahl (Citation2010) conceptualize cluster evolution as a life cycle that describes how clusters expand, stabilize and decline. Martin and Sunley (Citation2011) elaborate an adaptive cluster cycle that allows for a greater diversity of trajectories. Ter Wal and Boschma (Citation2011) propose a cycle that refers to the evolution of clusters, firms, networks and industries. A more specific model of evolution is Butler’s (Citation1980) tourist area life cycle that has been linked to path development (Benner, Citation2020b). While clusters are clearly relevant for path development (Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2013) and both approaches can be combined (Harris, Citation2020), the different trajectories the path development literature offers go beyond the idea of a uniform life cycle metaphor that Martin and Sunley (Citation2011) criticize.

Recent approaches have addressed how different newly emerging paths relate to each other by identifying types of interpath relationships (Frangenheim et al., Citation2020; Hassink et al., Citation2019; Miörner & Trippl, Citation2019) and by building on ideas of ‘interpath coupling’ (Martin & Sunley, Citation2006, p. 411) and ‘path interdependence’ (Martin & Sunley, Citation2006, p. 413). Together with established approaches such as related variety (Frenken et al., Citation2007), these concepts link sectoral path development to the evolution of the wider regional economy (Frangenheim et al., Citation2020).

However, what precisely facilitates or constrains each form of path development is still not sufficiently understood. Doing so requires looking beyond purely descriptive approaches of how industries evolve towards multidisciplinary concepts of why they evolve the way they do. Consequently, calls have surfaced for evolutionary economic geography to integrate insights from institutional and relational economic geography that can help understand the role institutions play for regional evolution including path development (Hassink et al., Citation2014, Citation2019; Trippl et al., Citation2018).

INSTITUTIONS

Institutional literature is rife with varying definitions of what institutions are (e.g., Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Gertler, Citation2010; Hodgson, Citation2006; Jepperson, Citation1991; Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006; Martin et al., Citation2011; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013). Following North (Citation1990, p. 3), institutions can simply be understood as ‘the rules of the game in a society’. More formally, they can be defined as ‘the humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic and social interaction’ (North, Citation1991, p. 97) and distinguished along their degree of formalization as either formal ones such as laws and regulations or informal ones such as customs or routines (North, Citation1990, Citation1991). According to Scott (Citation2014, p. 57), institutions can be understood as ‘multifaceted, durable social structures, made up of symbolic elements, social activities, and material resources’. Hodgson (Citation2006, p. 2) understands them ‘as systems of established and prevalent social rules that structure social interactions’. In a narrower definition that focuses less on formal rules than on practices (see also Jones & Murphy, Citation2010) and similarly to Hall and Thelen’s (Citation2009, p. 9) ‘sets of regularized practices with a rule-like quality’, Bathelt and Glückler (Citation2014, p. 346) understand institutions as ‘ongoing and relatively stable patterns of social practice based on mutual expectations’. In a similar vein, Nunn (Citation2012, p. S120) understands informal institutions as ‘collectively practiced norms of behavior’ which insinuates that formal and informal institutions can overlap because formal institutions can be either practiced or not (see also Glückler & Lenz, Citation2016). However, as Hodgson (Citation2006) argues, even formal institutions that are not actively practiced can remain relevant because changing external circumstances may lead to their reactivation, making it difficult to define institutions in terms of behaviour. Still, although behaviour needs to be distinguished from institutions, both are related because institutions not practiced can vanish in the long term and codifications of rules that are ignored by agents can hardly qualify as institutions (Hodgson, Citation2006; see also Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Martin et al., Citation2011). The link between institutions, formal rules and policies, and informal conventions (Dupuy et al., Citation1989; Hodgson, Citation2006; North, Citation1990; Salais & Storper, Citation1992) is marked by contingency (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2003, Citation2014) as different relationships between formal rules or policies and practiced institutions including reinforcement, substitution, circumvention, competition, coherence, compatibility, or complementarity can ensue (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Boyer, Citation2005; Glückler, Citation2020; Glückler et al., Citation2020; Glückler & Lenz, Citation2016; Zukauskaite et al., Citation2017). These contingent relationships bring with them contested processes of rule or policy implementation and related institutional leeway that accounts for the actual, partial, modified, or lacking transformation of rules and policies into institutions (Hall & Thelen, Citation2009; see also Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005).

Hence, for a precise understanding of what institutions are, distinguishing between formal institutions, informal institutions, and actual practices (Jones & Murphy, Citation2010) and clarifying their relationships is necessary. For the purposes of this paper, I adopt a working definition of institutions that reverts to North’s ‘rules of the game’ (North, Citation1990, p. 3) that can be either formal/explicit or informal/tacit (Hodgson, Citation2006) but have to be accepted by agents as social guidelines for appropriate and legitimate behaviour (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Lenz & Glückler, Citation2021; Martin et al., Citation2011; Oliver, Citation1992; Scott, Citation2014; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005) in the sense of being ‘templates for action’ (Lawrence et al., Citation2009, p. 7), even if they are not currently practiced. Following North’s (Citation1990, p. 4) characterization of organizations as ‘players’ and consistently with Bathelt and Glückler (Citation2014), organizations are not covered by this working definition of institutions (see also Glückler & Lenz, Citation2016; Zukauskaite et al., Citation2017).Footnote1 This understanding follows Hodgson (Citation2006) in that institutions are not identical with practices but are not ‘pure’ social structure detached from practice either; rather, institutions share characteristics of both. They can be understood as the idealized practices that are accepted in society or in a social subsystem as guidelines for behaviour (Glückler & Lenz, Citation2016; Scott, Citation2014). Institutions are what agents imagine what practices should be and thus form part of the social structure but without being a pure construction. These idealized practices shape agents’ expectations (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Jepperson, Citation1991) and thus can cause real social processes in a critical–realist perspective (Sayer, Citation1992, Citation2000).

INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

The insight that institutions affect regional development has become widely accepted (e.g., Martin et al., Citation2011; Zukauskaite et al., Citation2017), but how precisely they do is little understood (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013, Citation2020). While institutions provide framework conditions for relational processes of economic action (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2003), how the nature of institutional change impacts regional economies is probably one of the most relevant and least understood questions about regional development (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Glückler & Lenz, Citation2016; Hall & Thelen, Citation2009).

Institutions exhibit a strong degree of inertia (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Battilana et al., Citation2009; Essletzbichler & Rigby, Citation2007; Hodgson, Citation2006; Martin, Citation2000; Oliver, Citation1992; Scott, Citation2014; Sotarauta & Mustikkamäki, Citation2015; Strambach, Citation2010; Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2013), not least due to the long-term influence and persistence of the cultural norms and values often underlying them (Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012; Hodgson, Citation2006; North, Citation1990, Citation1991; Nunn, Citation2012). Institutional change can be radical or incremental although the borders between both types of change are fluid since incremental change can pile up and over time cause fundamental transformation (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019; MacKinnon, Citation2012; North, Citation1990; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). Patterns of institutional change are contingent on the context at hand (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2003, Citation2014). For example, incremental institutional change plays a prominent role in a system that Glückler et al. (Citation2020) describe as the ‘hourglass model’ marked by strong intra-firm relations, weak inter-firm relations, and strong regional-level networks, while a context marked by firm succession as in the Basque Country and Baden-Württemberg (Lenz & Glückler, Citation2021) could provide a peculiar opportunity for radical institutional change.

Rules or policies can enter a national or regional economy from the outside through policy transfer (see also Peck, Citation2002) following a ‘one size fits all’ logic (Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2005). Radical changes of rules and policies can stimulate processes of radical institutional change (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019) but not necessarily in a straightforward way because local evolutionary dynamics can lead to the adaptation of institutions to the given context and thus to incremental institutional change in a process of ‘hybridization’ (Boyer, Citation2005, p. 70). On the level of rules, agents can drive change through reform, defection, and reinterpretation (Hall & Thelen, Citation2009; see also Strambach, Citation2010; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005).

Institutional inertia makes incremental change seem more relevant and radical institutional change to be caused mainly by external impulses, sudden policy changes, or other pressures (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019; Martin, Citation2000; North, Citation1990). Incremental institutional change is a long-term process that can take decades in the case of formal institutions and even centuries in the case of informal, culturally engrained institutions (North, Citation1990, Citation1991; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2020; Scott, Citation2014; Williamson, Citation2000). Still, radical institutional change is possible. For example, as Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. (Citation2021) argue, radical institutional change can happen within established paths through path transformation (see also Miörner & Trippl, Citation2019; Strambach, Citation2010) which may often be due to intertemporal agency (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998; see also Battilana & D’Aunno, Citation2009), notably through institutional entrepreneurship (Battilana et al., Citation2009; DiMaggio, Citation1988; Greenwood & Suddaby, Citation2006; Hardy & Maguire, Citation2017; Sotarauta & Pulkkinen, Citation2011).

Following Streeck and Thelen (Citation2005), incremental change can often come about through endogenous processes that may be inherent to the practices engendered under an institution itself, and a sequence of such endogenous incremental changes piling up and leading to more radical change provides a trajectory towards endogenous radical institutional change (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). Further, endogenous and exogenous forces of institutional change may reinforce each other (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). As far as endogenous dynamics drive institutional change, they will often be the result of some form of institutional entrepreneurship (Greenwood & Suddaby, Citation2006).

As Streeck and Thelen (Citation2005) argue, apart from looking at radical or incremental changes on the level of results and besides sudden instances of exogenously caused radical breaks, institutional change can be classified in terms of process. They define five forms of slow but nevertheless powerful institutional change processes. Displacement refers to the substitution of one institution by another, possibly due to pre-existing contradictions and institutional competition. Layering means the emergence and eventual rise to dominance of alternatives to existing institutions proving difficult or virtually impossible to change. Drift implies the gradual degeneration of institutions that fail to keep pace with a changing context because of agents’ inactivity. Conversion refers to institutions being adapted to new purposes under changing conditions. Exhaustion describes the decline of an institution along a path of self-destruction which may be due to its inner dynamics (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005; see also Gong & Hassink, Citation2019; Martin, Citation2010).

Oliver (Citation1992) analyses processes of deinstitutionalization that lead either to an incremental erosion or to a more radical rejection of institutions (see also Jepperson, Citation1991; Scott, Citation2014). For example, leadership discontinuity in firm succession (Lenz & Glückler, Citation2021) can provide a context for deinstitutionalization (Oliver, Citation1992) that may often be radical but can also take an incremental form.

Institutional change can be driven by a variety of agency patterns including defection or reinterpretation (Hall & Thelen, Citation2009; Lowe & Feldman, Citation2017; Strambach, Citation2010; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005) which leads to the topics of institutional entrepreneurship and institutional work.

INSTITUTIONAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND INSTITUTIONAL WORK

Endogenous institutional change can be driven by a variety of agents (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020; Jolly et al., Citation2020) both on the firm level and the system level (Isaksen et al., Citation2019; see also Hassink et al., Citation2019) and on the level of a territory through ‘place leadership’ (Sotarauta, Citation2018; Sotarauta & Beer, Citation2017). For instance, Trippl et al. (Citation2020a) show how firm-level agency and system-level agency interact in bringing about changes (including institutional changes) that drive path development towards environmentally friendly technologies.

How agents induce institutional change needs a conceptualization that explains how agents perceive needs for change and enact it through mobilization (Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001; Seo & Creed, Citation2002). The approach of institutional entrepreneurship (Battilana et al., Citation2009; DiMaggio, Citation1988; Greenwood & Suddaby, Citation2006; Hardy & Maguire, Citation2017; Sotarauta & Mustikkamäki, Citation2015) can help us zoom in on the role of agency in shaping the institutional context of a regional economy (Sotarauta & Pulkkinen, Citation2011). For example, Lawrence and Phillips (Citation2004) describe how institutional entrepreneurship contributed to path diversification or even creation towards whale watching and how institutional entrepreneurs set the eventual standards for the new local industry on Vancouver Island through pragmatic and evolutionary decision-making. The same form of decision-making is found by Sotarauta and Mustikkamäki (Citation2015) in the regenerative medicine industry in Tampere. Institutional entrepreneurship can be broadly defined as intended or unintended changes of specific institutions by agents through some form of deliberate action (Battilana et al., Citation2009; Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001; North, Citation1990; Sotarauta & Pulkkinen, Citation2011). Rather than a precisely delimited phenomenon, institutional entrepreneurship provides a lens for understanding permanent processes of renegotiating an economy’s institutional context (Sotarauta & Pulkkinen, Citation2011; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005).

According to Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) and Jolly et al. (Citation2020), while it is possible to analytically distinguish different types of entrepreneurship and notably between commercially minded ‘Schumpeterian innovative entrepreneurship’ (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020, p. 706) and institutional entrepreneurship, empirically these patterns may overlap. Schumpeterian entrepreneurship understood as the establishment of new business models or other forms of seizing ground-breaking business opportunities (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020; Jolly et al., Citation2020) can have institutional implications, notably through the reinterpretation of the institutional context by entrepreneurial agents (Hall & Thelen, Citation2009; Lowe & Feldman, Citation2017; Strambach, Citation2010; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). Schumpeterian and institutional entrepreneurship will often (but not always) be different levels of the same actions (Bækkelund, Citation2021; Battilana et al., Citation2009; Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020), explaining why these actions can drive both industrial and institutional change in coevolution patterns.

A more far-reaching concept than institutional entrepreneurship to elucidate the relationship between institutions and agency (see also Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001; Scott, Citation2014; Seo & Creed, Citation2002) is institutional work (Lawrence et al., Citation2009; Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006). While institutional entrepreneurship in a broader sense aims at ‘changes that diverge from existing institutions’ (Battilana et al., Citation2009, p. 72) and thus covers a wide range of actions creating new institutions or disrupting existing ones (Battilana et al., Citation2009; see also Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001), institutional work additionally includes the day-to-day activities of maintaining existing institutions that are often necessary despite their inertia (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006; Lawrence et al., Citation2009; see also Scott, Citation2014; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). By defining a range of strategies for creating, maintaining, and disrupting institutions, Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006) propose a framework for the role of agency in both institutional change and stability.

These forms of agency can play a role in each of the slow, endogenous processes of institutional change identified by Streeck and Thelen (Citation2005). Institutional entrepreneurship can endogenously cause radical breaks, although such a case might be less frequent than gradual endogenous changes that add up to outcomes of radical institutional change (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). Processes and results of institutional change can span multiple spatial levels which raises the aspect of nestedness.

NESTEDNESS ACROSS SCALES

To operationalize coevolution, the multiscalarity of evolutionary processes and notably of institutional dynamics has to be taken into account (Binz & Truffer, Citation2017; Dawley et al., Citation2015; Gong & Hassink, Citation2019; Grillitsch, Citation2015; Hassink et al., Citation2019; Heiberg et al., Citation2020; MacKinnon et al., Citation2009; Scott, Citation2014; Zukauskaite et al., Citation2017). When looking at the role of institutions in regional economies, Gertler (Citation2010) calls for the consideration of different scales, and the concept of ‘institutional layers’ cutting across scales proposed by Grillitsch (Citation2015) highlights interdependencies between institutional patterns on different spatial scales. An emphasis on these multiscalar processes of institutional change is consistent with the call for a multiscalar perspective in evolutionary economic geography articulated by Hassink et al. (Citation2019). To understand the institutional context of a regional economy or its industries, considering the institutions present at the regional level is not sufficient because institutions are nested across spatial scales (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Binz & Truffer, Citation2017; Boyer & Hollingsworth, Citation1997; Bunnell & Coe, Citation2001; Hall & Thelen, Citation2009; Hassink et al., Citation2014, Citation2019; MacKinnon et al., Citation2009; Martin, Citation2000; Swyngedouw, Citation1997, Citation2004; Trippl et al., Citation2018; Zukauskaite et al., Citation2017).

According to Smith (Citation1992), spatial scales cannot be hierarchically ordered but are nested and socially constructed. Thus, ‘jumping scales’ (Smith, Citation1992, p. 66) of actions and patterns can occur in either direction which makes scales fluid and relative (Bunnell & Coe, Citation2001; Jonas, Citation1994; Smith, Citation1992; Swyngedouw, Citation1997; see also Peck, Citation2002). Socio-economic processes span nested scales, jump between them, and drive these scales’ permanent simultaneous reconfiguration (Swyngedouw, Citation1997, Citation2004). Because of this nestedness, ‘multifaceted causality runs in virtually all directions among the various levels of society’ (Boyer & Hollingsworth, Citation1997, p. 470). Patterns of industrial and institutional change can jump scales which calls for a multiscalar perspective of coevolution. Gong and Hassink (Citation2019, p. 1349) argue that multiscalarity is essential to coevolution because ‘all co-evolving populations are embedded in higher-level systems’. Consequently, their conceptual framework for coevolution refers to the regional, national, and global scales as well as to interregional and transnational relationships (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019). Yet, in a European context, it seems indispensable to consider the supranational level as an additional scale. In particular when it comes to regional policies, the role of European Union Cohesion Policy and its discourses such as Smart Specialisation (e.g., Gianelle et al., Citation2020; Hassink & Gong, Citation2019; Trippl et al., Citation2020b) cannot be ignored. Thus, a multiscalar perspective of coevolution has to include at least four scales (regional, national, supranational and global) and maybe even extend down to the local level.

A FRAMEWORK FOR COEVOLUTION

Coevolution (Malerba, Citation2006; Martin & Sunley, Citation2007; Murmann, Citation2013; Nelson, Citation1998; Schamp, Citation2009; Strambach, Citation2010; see also Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001; Grillitsch, Citation2015) focuses on defining industrial evolution not as an isolated phenomenon but in relation to other phenomena such as institutional change (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019). However, as Gong and Hassink (Citation2019) lay out, the coevolution discourse in the social sciences lacks a common understanding and definition. At the most basic level, coevolution refers to the interrelated dynamics of two populations (Schamp, Citation2009). This is not always clear since Boyer (Citation2005), for instance, discusses the coevolution of institutions with each other. The dynamics of these two populations are interrelated through ‘reciprocal (bidirectional) causal mechanisms’ (Murmann, Citation2013, p. 60). There is considerable ambiguity in the literature in defining what precisely coevolves. Murmann (Citation2013) refers to coevolution between ‘an industry and an important feature of its environment’ (p. 60) and in his study of the synthetic dye industry looks at the coevolution of industry and academic knowledge. Schamp (Citation2009) understands coevolution as linking knowledge and space. Nelson (Citation1998) discusses the coevolution of technologies, industries, and institutions. Gong and Hassink (Citation2019) define the relevant two coevolving populations as firms in an industry and institutions. However, such a definition does not sufficiently distinguish between the sectoral level in a regional economy and the aggregate territorial level of the regional economy (or on other scales). Looking at specific industries is justified because the role of knowledge cannot be dissociated from sectoral dynamics and thus, coevolution is sector or industry specific (Schamp, Citation2009). But how do industries in a regional economy interact? Which organizational or institutional patterns are industry specific and which ones span wider parts of the regional economy or higher scales? How is the impact of agency and policies (e.g., Dawley et al., Citation2015) differentiated across industries in a regional economy? How, for example, does the impact of place leadership (Sotarauta, Citation2018; Sotarauta & Beer, Citation2017) differ among industries in a regional economy? Considering the coevolution of firms and institutions both within and across industries in a given region and beyond and addressing some of these questions leads to a multipath and multiscalar perspective that provides a useful extension of existing concepts of coevolution. However, a comprehensive understanding of coevolution runs the risk of surrendering to the intricacies of regional economies as complex adaptive systems whose precise workings are close to impossible to capture (Bristow & Healy, Citation2014; Martin & Sunley, Citation2007, Citation2011).

Gong and Hassink (Citation2019) criticize that the discourse on coevolution has not yet led to a comprehensive and widely accepted conceptual framework and introduce the aspects of multiscalarity and radical and incremental change. Still, the framework proposed by Gong and Hassink (Citation2019) remains difficult to use for empirical research. To be suitable for empirical operationalization, a conceptual framework of coevolution needs to elucidate how industries and institutions on various scales interact with each other (sectoral level) and with their environment (territorial level) (see also Binz & Truffer, Citation2017) by drawing on forms of path development in multiple industries in a regional economy (see also Miörner & Trippl, Citation2019). Further, we need a clear understanding of precisely which institutions and their persistence or change affect industrial pathways and how concepts of agency such as institutional entrepreneurship or institutional work shape these processes. Such a multidimensional perspective enables to focus on the specific trajectories taken by firms in a specific industry in a regional economy and to understand institutional patterns within an industry, in the regional economy, and on higher spatial scales. Integrating regional industrial path development is useful not only because some institutions will be industry specific but also because institutions at the aggregate regional level as well as on higher scales may affect sectors or industries in uneven ways. Multidimensionality implies that multidirectional causal relationships can occur between dynamics of industrial and institutional change (industrial–institutional coevolution), between the resulting regional industrial paths (interpath relationships) on either scale, and between spatial scales (nestedness), or in all dimensions at once. Further, there is a dynamic perspective involved since the resulting patterns of path development are an ongoing process that affects industrial and institutional change in the future (see also Gong & Hassink, Citation2019).

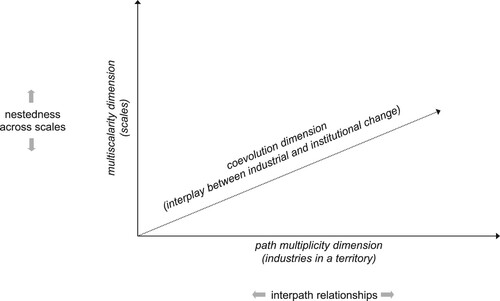

Operationalizing the concept of coevolution based on path multiplicity and multiscalarity requires a more fine-grained conceptual framework that is multidimensional and sufficiently differentiated to address the gaps identified but still sufficiently stylized to distil major coevolutionary trends. illustrates the logic behind such a framework along three dimensions: first, path multiplicity (industries in a territory); second, multiscalarity (scales); and third, coevolution (interplay between industrial and institutional change). Any given combination of these three dimensions yields a form of path development and concomitant patterns of nestedness of the path across scales, as well as interpath relationships on each scale.

Figure 1. Multidimensional framework of industrial–institutional coevolution.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Industries in a regional economy follow different pathways marked by specific interpath relationships (Frangenheim et al., Citation2020; Hassink et al., Citation2019; Miörner & Trippl, Citation2019), each with specific industrial and institutional patterns that coevolve. This multipath sectoral diversity characterizes trajectories of coevolution within and between sectoral pathways and thus calls for distinguishing between sectoral and territorial coevolutionary dynamics (see also Binz & Truffer, Citation2017). These intra- and interpath dynamics are affected by industrial and institutional patterns of change on higher spatial levels (national, supranational, global) and interact by jumping scales (Smith, Citation1992) in interscalar relationships (Peck, Citation2002) which add non-local impacts on path development to local ones (Binz et al., Citation2016; Binz & Truffer, Citation2017; Dawley et al., Citation2015; Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Hassink et al., Citation2019; Heiberg et al., Citation2020; Isaksen et al., Citation2018; Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2017; MacKinnon, Citation2012; Miörner & Trippl, Citation2019; Trippl et al., Citation2018; see also Bunnell & Coe, Citation2001; Martin & Sunley, Citation2006).

Operationalizing the framework needs several steps that are beyond the scope of this article. To demonstrate the approach, illustrates how patterns of industrial and institutional change relate to forms of positive and negative path development. The industrial population includes firms in a given industry but also industry-specific organizations and clusters. The institutional population refers to institutions on the sectoral and territorial levels as far as they are relevant for economic development as understood in the working definition followed here, that is, formal/explicit or informal/tacit rules accepted by agents as social guidelines for appropriate and legitimate behaviour, even if not currently practiced. Hence, formal rules, regulations, laws, and policies are not understood as institutions per se but need a certain degree of acceptance (Hodgson, Citation2006; Oliver, Citation1992). Following the examples for institutional change given by Gong and Hassink (Citation2019) and drawing on the role policy changes and new legislation can have on institutions (e.g., Oliver, Citation1992), formal rulemaking is included in as a source for institutional change. For the sake of brevity, does not include all possible forms of path development identified in the literature but focuses on some selected ones. Following Yeung’s (Citation2019) critical–realist distinction between processes and mechanisms, incremental or radical forms of industrial or institutional change can be understood as contingent, exogenous processes and lead to specific forms of path development through endogenous mechanisms (see also Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2020). This means that given instances of industrial or institutional change arising from within the regional economy or from the outside are hypothesized to coevolve into a specific pattern of path development. Given the bidirectionality and reciprocity of coevolution (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019; Malerba, Citation2006; Murmann, Citation2013; Schamp, Citation2009), not just does institutional change condition industrial change, but so can industrial change condition institutional change.Footnote2 In either case, the resulting pattern of change affects the probability for the resulting form(s) of path development.Footnote3

Table 1. Typology of coevolution and selected forms of path development.

Path extension is likely to ensue in the absence of radical change. While the industrial population is marked by incremental adaptations to slightly changing market conditions and technologies among firms (Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Isaksen, Citation2015; Isaksen et al., Citation2019) and further, probably moderate, growth of existing clusters, the institutional population relies on the reproduction and maintenance of existing institutions (Bækkelund, Citation2021; Jolly et al., Citation2020; Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006) and careful adaptation of institutions to changing contexts, policies, or legislation (Henderson, Citation2020), including through conversion (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005).

Somewhat stronger but still often incremental changes increase the probability for path upgrading. Industrially, firms move towards process, product or functional upgrading (Blažek, Citation2016; Humphrey & Schmitz, Citation2002) either individually or collectively in clusters undergoing a stage of ‘renaissance’ (Bergman, Citation2008, p. 123), ‘rejuvenation’ (Butler, Citation1980, p. 9), or ‘mutation’, ‘stabilization’ or ‘reorientation’ (Martin & Sunley, Citation2011, p. 1313). This might happen either as an incremental process, for example, by acquiring new technologies (Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Isaksen et al., Citation2018, Citation2019), or more radically as a reaction to external shocks, through radical innovations, or through the emergence of new businesses. On the institutional level, existing problems and needs for upgrading might slowly be accepted among agents in layering and conversion while a shift away from risk aversion and towards a more long-term planning horizon can happen through displacement and layering (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). Policies and laws promoting upgrading may increase incentives and pressure on firms and, if implemented, induce incremental institutional change, as the rise of an entrepreneurial academic culture and policies or laws setting incentives accordingly show (Etzkowitz, Citation2003; Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2013). Radical institutional change is possible through a breakdown of existing institutions in deinstitutionalization processes (Jepperson, Citation1991; Oliver, Citation1992), for example, through the market entry of agents introducing new routines and disrupting existing institutions (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006) and thereby acting as institutional entrepreneurs. A context marked by entrepreneurship or firm succession (Lenz & Glückler, Citation2021) might facilitate such a scenario. The sudden introduction of new policies and laws or external shocks might lead to the radical creation of new institutions through institutional entrepreneurship.

Path branching or diversification lead to the emergence of new paths out of existing ones but differ in their degree of newness because path branching builds on knowledge internal to the regional economy while path diversification builds on new knowledge (Benner, Citation2020c; Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Isaksen et al., Citation2018, Citation2019). Inhouse innovation by firms or new business formation through spinoffs can lead to path branching or diversification while more radical changes involving a different sectoral or scientific background will be needed for path diversification to evolve (Cassiman & Ueda, Citation2006; Dawley et al., Citation2015; Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001; Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Isaksen et al., Citation2018, Citation2019; Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2017; Klepper, Citation2007). Institutionally, through layering and conversion (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005), incremental changes can lead to either subtype of path development while a gradual shift away from risk aversion may facilitate path diversification. Radical institutional change can be brought about by new agents introducing new institutions through displacement or reinterpretation (Hall & Thelen, Citation2009; Lowe & Feldman, Citation2017; Strambach, Citation2010; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005) which may be needed for path diversification.

Path creation as the most far-reaching type of positive path development will to a large degree rely on radical change (Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Isaksen et al., Citation2018). Incremental industrial change such as the gradual emergence of a cluster (Bergman, Citation2008; Harris, Citation2020; Martin & Sunley, Citation2011; Menzel & Fornahl, Citation2010) may happen but more substantial changes, for example, through new business formation, are likely to be decisive for the development of the industry (Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Isaksen, Citation2015; Isaksen et al., Citation2018, Citation2019; Martin & Sunley, Citation2006; Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2013). The establishment of new scientific, educational, or support infrastructure (e.g., universities, science parks, incubators) can play a major role in path creation (Isaksen et al., Citation2018, Citation2019; Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2017; Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2013; Trippl et al., Citation2018; see also Miörner & Trippl, Citation2019). New institutions might crystallize incrementally through layering and conversion, including through the reinterpretation of existing institutions (Hall & Thelen, Citation2009; Lowe & Feldman, Citation2017; Strambach, Citation2010; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). Risk aversion might decrease while a competitive spirit and entrepreneurial attitudes might increase through layering and conversion (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). Entrepreneurship can bring with it the introduction of new routines by new firms, including those disrupting existing institutions (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006). Defection from established institutions (Hall & Thelen, Citation2009) by institutional entrepreneurs, including through accumulated displacement (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005), can further contribute to path creation (see also Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001). Again, external shocks and new policies and laws can induce radical institutional change (see also Binz et al., Citation2016; Dawley et al., Citation2015).

Under path contraction, incremental industrial change can be marked by the gradual narrowing of the industrial scope through re-specialization or by lock-in (Grabher, Citation1993; Hassink, Citation2010; Martin & Sunley, Citation2006) due to overspecialization (Blažek et al., Citation2020). A loss of skilled labour, mergers, or staff cutbacks can lead to the decline of a cluster (Bergman, Citation2008; Martin & Sunley, Citation2011; Menzel & Fornahl, Citation2010) which can happen gradually or suddenly. Abrupt external changes in the demand of large multinational buyers (Blažek et al., Citation2020) can be another reason for radical industrial change. Incremental institutional change can strengthen damaging institutions and induce lock-in (Grabher, Citation1993; Hassink, Citation2010; Martin & Sunley, Citation2006), institutional hysteresis (Martin & Sunley, Citation2006; Setterfield, Citation1993), and drift and exhaustion (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005), including through the gradual emergence of an inward-looking vision among agents (Benner, Citation2020c). Existing institutions can radically break down through deinstitutionalization (Jepperson, Citation1991; Oliver, Citation1992) and agents disrupting existing institutions (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006) without creating new ones that could lead, for example, to path upgrading. For instance, a loss of trust relationships due to a shrinkage of the firm population (Blažek et al., Citation2020) or in the context of firm succession (Lenz & Glückler, Citation2021) could lead to displacement, drift, and exhaustion (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005).

Path downgrading can be related to incremental industrial changes such as inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) changing the structure of the industry by creating branch plant economies (Blažek et al., Citation2020; MacKinnon, Citation2012). Sudden external changes such as the transformation of state-owned companies can lead to radical change while staff cutbacks or the loss of skilled labour and the associated knowledge and expertise can be either incremental or radical (Bergman, Citation2008; Blažek et al., Citation2020). Existing institutions can gradually dissolve and be substituted by institutions of a branch plant economy through displacement, drift, and exhaustion (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005) and firms may gradually adopt myopic business philosophies based on cost competition. Deinstitutionalization (Jepperson, Citation1991; Oliver, Citation1992) and the disruption of institutions (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006) can lead to their breakdown, for instance when existing networks break up (Blažek et al., Citation2020), possibly through continued exhaustion (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). Defection from established institutions can occur (Hall & Thelen, Citation2009), including through accumulated displacement (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005).

While the processes described are stylized and shifts between paths, even positive and negative ones, are possible (Blažek et al., Citation2020), the framework offers a heuristic that can be applied for better understanding coevolution but will have to be further elaborated, in particular since the processes can apply to each spatial scale due to the multiscalarity of path dependence (Grillitsch, Citation2015; Hassink, Citation2010; Martin & Sunley, Citation2006).

OUTLOOK

This paper introduced a conceptual framework meant to contribute to a more precise and useful operationalization of coevolution needed to overcome the concept’s limited empirical relevance (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019, Citation2020). Nevertheless, further conceptual research will be needed before the framework can be used empirically. In particular, the framework needs to be further detailed on interpath relationships (Frangenheim et al., Citation2020) between sectoral pathways and their territorial aggregation on the level of the regional economy to fully elaborate the dimension of path multiplicity. In the same vein, the multiscalar dimension needs to be further developed by defining the interrelationships between industrial or institutional change across scales. More detailed elaboration both on interscalar and interpath relationships can guide empirical research that may help us better understand how these relationships work. Such an effort could make us understand more than we presently do about institutional patterns at higher spatial scales including the global and supranational scales which would probably need theories of institutional change and stability similar in scope to those that focus primarily on the national scale (e.g., Boyer, Citation1988; Hall & Soskice, Citation2001). In particular when looking at the global level, such an effort might even require an integration of sectoral patterns to avoid excessive generality and to include the concept of sectoral ‘institutional layers’ (Grillitsch, Citation2015). Focusing on the contested nature of institutional change (e.g., DiMaggio, Citation1988; Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001; Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006; Scott, Citation2014; Seo & Creed, Citation2002) in coevolution could help address the political relevance of multiscalar coevolution processes, for example in a critical perspective or under variegated capitalism (Peck & Theodore, Citation2007; see also MacKinnon, Citation2012; MacKinnon et al., Citation2009). Such a perspective could address questions such as, how do political interests on different scales affect either side of coevolution and which groups do the resulting coevolution processes benefit, including in jumping between nested scales (Smith, Citation1992)?

Further, elaborating on the dynamic perspective of coevolution could help answer the question of how path development further shapes industrial and institutional change in the future and thus add one more dimension (see also Zukauskaite et al., Citation2017). Another avenue for further research is taking a closer look at how precisely agency plays out in industrial–institutional coevolution, in line with the growing interest in agency visible in the regional development discourse in recent years (e.g., Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020; Isaksen et al., Citation2019; Jolly et al., Citation2020; Sotarauta & Beer, Citation2017; Trippl et al., Citation2020a) and possibly extending to concepts of behavioural economics (Benner, Citation2020a). For example, what motivates agents to induce peculiar industrial and institutional changes? Further, while the present article’s focus was on how industrial and institutional change drive coevolution, it will be important to extend the perspective towards maintenance agency by agents working against change (Henderson, Citation2020; Jolly et al., Citation2020) or reproductive agency (Bækkelund, Citation2021; Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005) within the forms of institutional work aimed at maintaining institutions (Lawrence et al., Citation2009; Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006; see also Scott, Citation2014) that could play a significant role in path development. For example, how does the maintenance (as opposed to change) of institutions affect coevolution on either scale?

While the present article can only contribute to a detailed conceptualization of coevolution by proposing a multidimensional framework, further research will be useful to fill the remaining gaps. This article contributes to retheorizing coevolution by postulating mechanisms that drive different forms of path development and by linking them to contingent processes of change (Yeung, Citation2019) and thus aspires to make the concept of coevolution more accessible for empirical research. In the next step, these mechanisms will have to be analysed in concrete empirical cases before being decontextualized again (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2003). Such an exercise of repeated retheorizing by confronting the general concept with particular contexts through empirical case study research that Gong and Hassink (Citation2020) define as the strength of economic geographers can refine the concept of coevolution and with it our understanding of how regional economies develop and why. If successful, such a research agenda could produce powerful analytical tools for scholars and policymakers alike.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research for this paper began while the author was employed at Heidelberg University. The author is grateful to Michaela Trippl for drawing his attention to the relevance of maintenance agency and for suggesting the distinction between sectoral and territorial levels; as well as to Johannes Glückler and Jakob Hoffmann for drawing his attention to the distinction between new business models and institutional entrepreneurship. The author is further grateful to the editor, Michael Fritsch, and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments. Of course, all remaining errors and omissions are the author’s alone.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. As Hodgson (Citation2006) lays out, whether organizations are understood as institutions or agents depends on the level of analysis. To study coevolution it seems justified to understand organizations as agents because they pursue strategies that can lead to industrial or institutional change (see also North, Citation1990; Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020; Scott, Citation2014; Zukauskaite et al., Citation2017).

2. The latter can be the case, for example, when new business models contain a level of institutional entrepreneurship by changing, disrupting of creating institutions (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006; Lawrence et al., Citation2009).

3. The remainder of this section partly builds on Benner (Citation2020c) and Gong and Hassink (Citation2019), as well as on the path development literature (Blažek et al., Citation2020; Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Isaksen et al., Citation2018, Citation2019).

REFERENCES

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity and poverty. Profile.

- Bækkelund, N. G. (2021). Change agency and reproductive agency in the course of industrial path evolution. Regional Studies, 55(4), 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1893291

- Bathelt, H., & Glückler, J. (2003). Toward a relational economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 3(2), 117–144. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/3.2.117

- Bathelt, H., & Glückler, J. (2014). Institutional change in economic geography. Progress in Human Geography, 38(3), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513507823

- Battilana, J., & D’Aunno, T. (2009). Institutional work and the paradox of embedded agency. In T. B. Lawrence, R. Suddaby, & B. Leca (Eds.), Institutional work: Actors and agency in institutional studies of organizations (pp. 31–58). Cambridge University Press.

- Battilana, J., Leca, B., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 65–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903053598

- Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., Miörner, J., & Trippl, M. (2021). Towards a stage model of regional industrial path transformation. Industry and Innovation, 28(2), 160–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2020.1789452

- Benner, M. (2020a). Mitigating human agency in regional development: The behavioural side of policy processes. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 7, 164–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2020.1760732

- Benner, M. (2020b). The decline of tourist destinations: An evolutionary perspective on overtourism. Sustainability, 12(9), 3653. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093653

- Benner, M. (2020c). The spatial evolution–institution link and its challenges for regional policy. European Planning Studies, 28(12), 2428–2446. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1698520

- Bergman, E. M. (2008). Cluster life cycles: An emerging synthesis. In C. Karlsson (Ed.), Handbook of research on cluster theory (pp. 114–132). Elgar.

- Binz, C., & Truffer, B. (2017). Global innovation systems – A conceptual framework for innovation dynamics in transnational contexts. Research Policy, 46(7), 1284–1298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.05.012

- Binz, C., Truffer, B., & Coenen, L. (2016). Path creation as a process of resource alignment and anchoring: Industry formation for on-site water recycling in Beijing. Economic Geography, 92(2), 172–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1103177

- Blažek, J. (2016). Towards a typology of repositioning strategies of GVC/GPN suppliers: The case of functional upgrading and downgrading. Journal of Economic Geography, 16(4), 849–869. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbv044

- Blažek, J., Květoň, V., Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., & Trippl, M. (2020). The dark side of regional industrial path development: Towards a typology of trajectories of decline. European Planning Studies, 28(8), 1455–1473. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1685466

- Boyer, R. (1988). Technical change and the theory of ‘régulation’. In G. Dosi, C. Freeman, R. R. Nelson, G. Silverberg, & L. L. G. Soete (Eds.), Technical change and economic theory (pp. 67–94). Pinter.

- Boyer, R. (2005). Coherence, diversity, and the evolution of capitalisms – The institutional complementarity hypothesis. Evolutionary and Institutional Economics Review, 2(1), 43–80. https://doi.org/10.14441/eier.2.43

- Boyer, R., & Hollingsworth, J. R. (1997). From national embeddedness to spatial and institutional nestedness. In J. R. Hollingsworth & R. Boyer (Eds.), Contemporary capitalism: The embeddedness of institutions (pp. 433–484). Cambridge University Press.

- Bristow, G., & Healy, A. (2014). Building resilient regions: Complex adaptive systems and the role of policy intervention. Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 72(2), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13147-014-0280-0

- Bunnell, T. G., & Coe, N. M. (2001). Spaces and scales of innovation. Progress in Human Geography, 25(4), 569–589. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913201682688940

- Butler, R. (1980). The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer, 24(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.1980.tb00970.x

- Cassiman, B., & Ueda, M. (2006). Optimal project rejection and new firm start-ups. Management Science, 52(2), 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1050.0458

- Dawley, S., MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., & Pike, A. (2015). Policy activism and regional path creation: The promotion of offshore wind in North East England and Scotland. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(2), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu036

- DiMaggio, P. (1988). Interest and agency in institutional theory. In L. Zucker (Ed.), Institutional patterns and organizations: Culture and environment (pp. 3–21). Ballinger.

- Dupuy, J. P., Eymard-Duvernay, F., Favereau, O., Orléan, A., Salais, R., & Thévenot, L. (1989). Introduction. Revue économique, 40, 141–145.

- Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023. https://doi.org/10.1086/231294

- Essletzbichler, J., & Rigby, D. L. (2007). Exploring evolutionary economic geographies. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(5), 549–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm022

- Etzkowitz, H. (2003). Research groups as ‘quasi-firms’: The invention of the entrepreneurial university. Research Policy, 32(1), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00009-4

- Frangenheim, A., Trippl, M., & Chlebna, C. (2020). Beyond the single path view: Interpath dynamics in regional contexts. Economic Geography, 96(1), 31–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2019.1685378

- Frenken, K., Van Oort, F., & Verburg, T. (2007). Related variety, unrelated variety and regional economic growth. Regional Studies, 41(5), 685–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400601120296

- Garud, R., & Karnøe, P. (2001). Path creation as a process of mindful deviation. In R. Garud & P. Karnøe (Eds.), Path dependence and creation (pp. 1–38). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Gertler, M. S. (2010). Rules of the game: The place of institutions in regional economic change. Regional Studies, 44(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400903389979

- Gianelle, C., Guzzo, F., & Mieszkowski, K. (2020). Smart specialisation: What gets lost in translation from concept to practice? Regional Studies, 54(10), 1377–1388. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1607970

- Glückler, J. (2020). Institutional context and place-based policy: The case of Coventry & Warwickshire. Growth and Change, 51(1), 234–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12362

- Glückler, J., & Lenz, R. (2016). How institutions moderate the effectiveness of regional policy: A framework and research agenda. Investigaciones Regionales - Journal of Regional Research, 36, 255–277.

- Glückler, J., Punstein, A. M., Wuttke, C., & Kirchner, P. (2020). The ‘hourglass’ model: An institutional morphology of rural industrialism in Baden-Württemberg. European Planning Studies, 28(8), 1554–1574. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1693981

- Gong, H., & Hassink, R. (2019). Co-evolution in contemporary economic geography: Towards a theoretical framework. Regional Studies, 53(9), 1344–1355. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1494824

- Gong, H., & Hassink, R. (2020). Context sensitivity and economic–geographic (re)theorising. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 13(3), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsaa021

- Grabher, G. (1993). The weakness of strong ties: The lock-in of regional development in the Ruhr area. In G. Grabher (Ed.), The embedded firm: On the socioeconomics of industrial networks (pp. 255–277). Routledge.

- Greenwood, R., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutional entrepreneurship in mature fields: The big five accounting firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.20785498

- Grillitsch, M. (2015). Institutional layers, connectedness and change: Implications for economic evolution in regions. European Planning Studies, 23(10), 2099–2124. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2014.1003796

- Grillitsch, M., Asheim, B., & Trippl, M. (2018). Unrelated knowledge combinations: The unexplored potential for regional industrial path development. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(2), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy012

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). An introduction to varieties of capitalism. In P. A. Hall & D. Soskice (Eds.), Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage (pp. 1–68). Oxford University Press.

- Hall, P. A., & Thelen, K. (2009). Institutional change in varieties of capitalism. Socio-Economic Review, 7(1), 7–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwn020

- Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2017). Institutional entrepreneurship and change in fields. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T. B. Lawrence, & R. E. Meyer (Eds.), SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 261–280). Sage.

- Harris, J. L. (2020). Rethinking cluster evolution: Actors, institutional configurations, and new path development. Progress in Human Geography, 45(3), 436–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520926587

- Hassink, R. (2010). Locked in decline? On the role of regional lock-ins in old industrial areas. In R. Boschma & R. Martin (Eds.), The handbook of evolutionary economic geography (pp. 450–468). Elgar.

- Hassink, R., & Gong, H. (2019). Six critical questions about smart specialization. European Planning Studies, 27(10), 2049–2065. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1650898

- Hassink, R., Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2019). Towards a comprehensive understanding of new regional industrial path development. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1636–1645. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Hassink, R., Klaerding, C., & Marques, P. (2014). Advancing evolutionary economic geography by engaged pluralism. Regional Studies, 48(7), 1295–1307. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.889815

- Heiberg, J., Binz, C., & Truffer, B. (2020). The geography of technology legitimation: How multiscalar institutional dynamics matter for path creation in emerging industries. Economic Geography, 96(5), 470–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2020.1842189

- Henderson, D. (2020). Institutional work in the maintenance of regional innovation policy instruments: Evidence from Wales. Regional Studies, 54(3), 429–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1634251

- Hodgson, G. M. (2006). What are institutions? Journal of Economic Issues, 40(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2006.11506879

- Humphrey, J., & Schmitz, H. (2002). How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Regional Studies, 36(9), 1017–1027. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340022000022198

- Isaksen, A. (2015). Industrial development in thin regions: Trapped in path extension? Journal of Economic Geography, 15(3), 585–600. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbu026

- Isaksen, A., Jakobsen, S., Njøs, R., & Normann, R. (2019). Regional industrial restructuring resulting from individual and system agency. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 32(1), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2018.1496322

- Isaksen, A., Tödtling, F., & Trippl, M. (2018). Innovation policies for regional structural change: Combining actor-based and system-based strategies. In A. Isaksen, R. Martin, & M. Trippl (Eds.), New avenues for regional innovation systems: Theoretical advances, empirical cases and policy lessons (pp. 221–238). Springer.

- Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2017). Exogenously led and policy-supported new path development in peripheral regions: Analytical and synthetic routes. Economic Geography, 93(5), 436–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2016.1154443

- Jepperson, R. J. (1991). Institutions, institutional effects, and institutionalism. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 143–163). University of Chicago Press.

- Jolly, S., Grillitsch, M., & Hansen, T. (2020). Agency and actors in regional industrial path development. A framework and longitudinal analysis. Geoforum, 111, 176–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.013

- Jonas, A. E. G. (1994). The scale politics of spatiality. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 12(3), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1068/d120257

- Jones, A., & Murphy, J. T. (2010). Theorizing practice in economic geography: Foundations, challenges, and possibilities. Progress in Human Geography, 35(3), 366–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510375585

- Klepper, S. (2007). Disagreements, spinoffs, and the evolution of Detroit as the capital of the U.S. automobile industry. Management Science, 53(4), 616–631. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0683

- Lawrence, T. B., & Phillips, N. (2004). From Moby dick to free Willy: Macro-cultural discourse and institutional entrepreneurship in emerging institutional fields. Organization, 11(5), 689–711. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508404046457

- Lawrence, T. B., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutions and institutional work. In S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. B. Lawrence, & W. R. Nord (Eds.), SAGE handbook of organization studies (2nd ed., pp. 215–254). Sage.

- Lawrence, T. B., Suddaby, R., & Leca, B. (2009). Introduction: Theorizing and studying institutional work. In T. B. Lawrence, R. Suddaby, & B. Leca (Eds.), Institutional work: Actors and agency in institutional studies of organizations (pp. 1–27). Cambridge University Press.

- Lenz, R., & Glückler, J. (2021). Same same but different: Regional coherence between institutions and policies in family firm succession. European Planning Studies, 29(3), 536–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1757041

- Lowe, N. J., & Feldman, M. P. (2017). Institutional life within an entrepreneurial region. Geography Compass, 11(3), e12306. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12306

- MacKinnon, D. (2012). Beyond strategic coupling: Reassessing the firm–region nexus in global production networks. Journal of Economic Geography, 12(1), 227–245. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbr009

- MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., Pike, A., Birch, K., & McMaster, R. (2009). Evolution in economic geography: Institutions, political economy, and adaptation. Economic Geography, 85(2), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01017.x

- Malerba, F. (2006). Innovation and the evolution of industries. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 16, 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-005-0005-1

- Martin, R. (2000). Institutional approaches in economic geography. In E. Sheppard & T. J. Barnes (Eds.), A companion to economic geography (pp. 77–94). Blackwell.

- Martin, R. (2010). Roepke Lecture in Economic Geography: Rethinking regional path dependence: Beyond lock-in to evolution. Economic Geography, 86(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x

- Martin, R., Moodysson, J., & Zukauskaite, E. (2011). Regional innovation policy beyond ‘best practice’: Lessons from Sweden. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 2(4), 550–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-011-0067-2

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2007). Complexity thinking and evolutionary economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(5), 573–601. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm019

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2011). Conceptualizing cluster evolution: Beyond the life cycle model? Regional Studies, 45(10), 1299–1318. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.622263

- Menzel, M. P., & Fornahl, D. (2010). Cluster life cycles – Dimensions and rationales of cluster evolution. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(1), 205–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtp036

- Miörner, J., & Trippl, M. (2019). Embracing the future: Path transformation and system reconfiguration for self-driving cars in West Sweden. European Planning Studies, 27(11), 2144–2162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1652570

- Murmann, J. P. (2013). The coevolution of industries and important features of their environments. Organization Science, 24(1), 58–78. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0718

- Nelson, R. R. (1998). The co-evolution of technology, industrial structure, and supporting institutions. In J. Chytry, D. J. Teece, & G. Dosi (Eds.), Technology, organization, and competitiveness: Perspectives on industrial and corporate change (pp. 319–335). Oxford University Press.

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

- North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.5.1.97

- Nunn, N. (2012). Culture and the historical process. Economic History of Developing Regions, 27(Suppl. 1), S108–S126. https://doi.org/10.1080/20780389.2012.664864

- Oliver, C. (1992). The antecedents of deinstitutionalization. Organization Studies, 13(4), 563–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084069201300403

- Peck, J. (2002). Political economies of scale: Fast policy, interscalar relations, and neoliberal workfare. Economic Geography, 78(3), 331–360. https://doi.org/10.2307/4140813

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2007). Variegated capitalism. Progress in Human Geography, 31(6), 731–772. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132507083505

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013). Do institutions matter for regional development? Regional Studies, 47(7), 1034–1047. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.748978

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2020). Institutions and the fortunes of regions. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 12(3), 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12277

- Salais, R., & Storper, M. (1992). The four ‘worlds’ of contemporary industry. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 16(2), 169–193. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.cje.a035199

- Sayer, A. (1992). Method in social science: A realist approach (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Sayer, A. (2000). Realism and social science. Sage.

- Schamp, E. W. (2009). Wissen, Netzwerk und Raum – offen für ein Konzept der ‘co-evolution’? In U. Matthiesen & G. Mahnken (Eds.), Das Wissen der Städte: Neue stadtregionale Entwicklungsdynamiken im Kontext von Wissen, Milieus und Governance (pp. 33–45). Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Scott, W. R. (2014). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities (4th ed.). Sage.

- Seo, M. G., & Creed, W. E. D. (2002). Institutional contradictions, praxis, and institutional change: A dialectical perspective. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 222–247. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2002.6588004

- Setterfield, M. (1993). A model of institutional hysteresis. Journal of Economic Issues, 27(3), 755–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.1993.11505453

- Smith, N. (1992). Contours of a spatialized politics: Homeless vehicles and the production of geographical scale. Social Text, 33(33), 54–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/466434

- Sotarauta, M. (2018). Smart specialization and place leadership: Dreaming about shared visions, falling into policy traps? Regional Studies, Regional Science, 5(1), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2018.1480902

- Sotarauta, M., & Beer, A. (2017). Governance, agency and place leadership: Lessons from a crossnational analysis. Regional Studies, 51(2), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1119265

- Sotarauta, M., & Mustikkamäki, N. (2015). Institutional entrepreneurship, power, and knowledge in innovation systems: Institutionalization of regenerative medicine in Tampere, Finland. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 33(2), 342–357. https://doi.org/10.1068/c12297r

- Sotarauta, M., & Pulkkinen, R. (2011). Institutional entrepreneurship for knowledge regions: In search of a fresh set of questions for regional innovation studies. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 29(1), 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1066r

- Strambach, S. (2010). Path dependence and path plasticity: The co-evolution of institutions and innovation – The German customized business software industry. In R. Boschma & R. Martin (Eds.), Handbook of evolutionary economic geography (pp. 406–431). Elgar.

- Streeck, W., & Thelen, K. (2005). Introduction: Institutional change in advanced political economies. In W. Streeck & K. Thelen (Eds.), Beyond continuity: Institutional change in advanced political economies (pp. 1–39). Oxford University Press.

- Swyngedouw, E. (1997). Neither global nor local: ‘Glocalization’ and the politics of scale. In K. R. Cox (Ed.), Spaces of globalization: Reasserting the power of the local (pp. 137–166). Guilford Press.

- Swyngedouw, E. (2004). Globalisation or ‘glocalisation’? Networks, territories and rescaling. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 17(1), 25–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/0955757042000203632

- Ter Wal, A. L., & Boschma, R. (2011). Co-evolution of firms, industries and networks in space. Regional Studies, 45(7), 919–933. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400802662658

- Tödtling, F., & Trippl, M. (2005). One size fits all? Towards a differentiated regional innovation policy approach. Research Policy, 34(8), 1203–1219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.01.018

- Tödtling, F., & Trippl, M. (2013). Transformation of regional innovation systems: From old legacies to new development paths. In P. Cooke (Ed.), Re-framing regional development: Evolution, innovation, and transition (pp. 297–317). Routledge.

- Trippl, M., Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., Frangenheim, A., Isaksen, A., & Rypestøl, J. O. (2020a). Unravelling green regional industrial path development: Regional preconditions, asset modification and agency. Geoforum, 111, 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.016

- Trippl, M., Grillitsch, M., & Isaksen, A. (2018). Exogenous sources of regional industrial change: Attraction and absorption of non-local knowledge for new path development. Progress in Human Geography, 42(5), 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517700982

- Trippl, M., Zukauskaite, E., & Healy, A. (2020b). Shaping smart specialization: The role of place-specific factors in advanced, intermediate and less-developed European regions. Regional Studies, 54(10), 1328–1340. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1582763

- Williamson, O. E. (2000). The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(3), 595–613. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.38.3.595

- Yeung, W. H. (2019). Rethinking mechanism and process in the geographical analysis of uneven development. Dialogues in Human Geography, 9(3), 226–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820619861861

- Zukauskaite, E., Trippl, M., & Plechero, M. (2017). Institutional thickness revisited. Economic Geography, 93(4), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2017.1331703