ABSTRACT

The supply of entrepreneurial finance in Europe is constrained by the geographical fragmentation of its capital market. The need to facilitate more cross-border investing by business angels – the main source of early stage finance – is recognized. A study of business angels on the island of Ireland identifies three constraints on cross-border investing: (1) lack of information on cross-border investment opportunities; (2) the preference of angels to invest locally; and (3) tax incentives that are only available for investments in the angel’s own country. Increasing cross-border investment requires mechanisms that build relationships between business angels in different countries.

INTRODUCTION

The European Investment Bank (EIB) (Citation2019, p. 279) has recently highlighted Europe’s ‘poor track record when it comes to forming start-ups and scaling up young firms with high growth ambitions, particularly when compared to the United States and China’. Its analysis indicates that the EU-27 lags behind the United States in its number of young, high-growth firms by a factor of three (EIB, Citation2019). This has significant economic implications. Start-up and scale-up businesses are drivers of aggregate investment activity, in particular investment in intangible assets, investing significantly more per employee than do more mature firms. Start-ups and scale-ups are also a key source of innovation. They also make an important contribution to employment growth (EIB, Citation2019).

Europe’s lack of scale-ups is widely attributed to its relatively under-developed business angel and venture capital (VC) markets (AFME, Citation2017; Duruflé et al., Citation2018; EIB, Citation2019). VC investments in European tech start-ups amounted to US$41 billion in 2020 (up from US$38.6 billion in 2019 despite the Covid-19 pandemic). However, this was considerably lower than in both the United States where tech start-ups raised US$141 billion and Asia where tech start-ups raised US$74 billion (Atomico, Citation2020). European Union (EU) scale-ups are significantly more likely to report access to finance as an issue compared with their US peers (EIB, Citation2019).

Europe’s smaller VC industry – which is manifest in the smaller size of funds, smaller average size of funding rounds, fewer number of rounds and smaller proportion of later stage rounds (Duruflé et al., Citation2018) – is attributed in large measure to its fragmented capital market (Kraemer-Eis et al., Citation2018). As one commentator notes: ‘The European Union … is still not one large VC market; instead, the EU is made up of twenty-eight markets with different regulatory regimes’ (Moehr, Citation2017). Europe’s fragmented capital market also creates legal and fiscal obstacles for business angels which hampers their ability to make cross-border investments (Mollen, Citation2019a). A survey of 90 active business angels in 11 European countries reported that 55% of those who have made cross-border investments reported that it was ‘difficult’ or ‘very difficult’ (EBAN, Citation2020).

The EU has recognized the need to bring about a more unified capital market to drive forward the European economy. Its Capital Markets Union (CMU) initiative was launched in 2014 with the aim of deepening and further integrating the capital markets of EU member states. Specific initiatives in the plan to address the fragmented nature of Europe’s VC market include regulatory changes and the creation of a pan-European VC fund-of-funds programme (VentureEU) managed by the European Investment Fund (EIF). However, as an EU High Level Forum on CMU (Citation2020) had noted, ‘the EU has struggled to make its capital markets work as one, and to a large degree still has 27 capital markets’. Its report to the European Commission, published in June 2020 – which stresses that a single capital market is even more important now as the EU recovers from the Covid-19 economic crisis – recommends a further array of measures to move the EU much closer to a single market for savings, investments and capital-raising.

The need to facilitate more cross-border investments by European business angels to increase the number of competitive start-ups has also been recognized. Business angels play a critical role in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, funding the start of the entrepreneurial pipeline. They are the dominant source of early stage VC, investing just over €8 billion in early stage businesses in Europe in 2019 compared with €4.4 billion by VC funds (EBAN, Citation2020). Nevertheless, Europe’s angel market is not as deep as that of the United States, and its pool of entrepreneurs who have successfully built, scaled and sold start-ups its much smaller. Moreover, sources of risk capital are more abundant in the United States so start-ups have got more avenues for obtaining their initial funding and do not necessarily have to raise an angel round before getting funding from larger investors. And because Europe’s VC market is not as deep in many European countries entrepreneurs who have raised finance from business angels may be unable to raise scale-up funding. These problems are exacerbated by the fragmentation of Europe’s early stage capital market along national lines (Mollen, Citation2019a, Citation2019b).

A European Commission (Citation2012) Expert Group argued that the EU must play a more active role in stimulating and advancing cross-border investing by business angels. Other institutions (e.g., AFME, Citation2018) and commentators (e.g., Mollen, Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2019a; Viimsalu, Citation2014) have also argued for the need to facilitate more cross-border angel investment in Europe. One commentator has argued that ‘building cross-border angel investment is a very useful first step to building a more unified EU funding market’ (Mollen, Citation2019a). Increased cross-border investing by its business angels is required to enable European companies to scale up to the point where they can attract global investors and access foreign investors who can play a role in facilitating their international expansion (Mollen, Citation2019a). Companies that are unable to raise sufficient early stage finance in Europe may move to the United States, or, increasingly to China, may struggle against better funded competitors or may simply fail (Mollen, Citation2019a). Angels will also benefit from making cross-border investments. These include the potential for investing in start-ups which, because of their location, have lower costs burn rates and hence longer financial runways, access to deals in entrepreneurial ecosystems that are hubs for new technologies, broader deal flow and portfolio diversification (Helsinki Business Hub, Citation2020). However, the objective of increasing the scale of cross-border investments by business angels goes against their strong tendency to invest locally (Avdeitchikova, Citation2009; Harrison et al., Citation2010). A study of angels who partner with the EIF angel fund reported that only 12% of their investments were cross-border (Gvetadze et al., Citation2020). An EU-wide study found that 10% of investments by business angels were cross-border (Ali et al., Citation2017). Both studies focused on experienced and wealthier angels. Other studies report much lower proportions of cross-border investments (AFME, Citation2017; Harrison et al., Citation2010).

Given this evidence of the strong tendency of business angels to invest within their own countries, this paper offers a critical assessment of this policy aspiration to promote cross-border investing by business angels and what initiatives are required to ‘move the needle’. It draws on evidence from a study of business angel investing on the island of Ireland where despite specific interventions to enable angels in Northern Ireland (part of the UK) and the Republic of Ireland to make cross-border investments the volume of such investments remains low. The paper examines the reasons for the limited scale of cross-border investments and then draws on this evidence to offer guidance to policymakers on the barriers that need to be overcome, and the types of initiatives that are required to facilitate angels to make cross-border investments.

The paper is structured as follows. First, evidence on the role of distance in the investment decisions of business angels is reviewed. Second, the geographical context of the study is discussed. Third, the data sources are described and the respondents are profiled. Fourth, a brief overview of their investment activity is provided. Fifth, the engagement of business angels in, and attitudes to, cross-border investing are examined. The concluding section re-engages with policy, considering in the light of this evidence what are the key barriers to increasing the scale of cross-border investing by business angels and what actions policymakers in the EU and elsewhere require to implement to achieve their goal of promoting angel investment across borders.

THE INFLUENCE OF DISTANCE IN BUSINESS ANGEL INVESTMENT DECISION-MAKING

Business angels invest primarily for financial reasons, seeking a capital gain on their investments through a harvest event (normally the acquisition of the investee business). However, most acknowledge that they also seek physic income which they derive from engaging with new entrepreneurial ventures, notably the satisfaction and excitement from helping them to succeed and, in some cases, from the societal benefits that their investee businesses might generate (Morrissette, Citation2007; Sullivan & Miller, Citation1996; Wetzel, Citation1983). Whilst most invest on their own, angels are increasingly investing as part of more formalized angel groups (Mason et al., Citation2016). Angel groups have the financial resources both to make larger initial investments and follow-on investments, filling the funding gap created by the shift in the investment activity of VC funds to both larger and later stage deals.

The early stage at which business angels are investing is characterized by significant information asymmetries, many of which are distance related (Gvetadze et al., Citation2020). These information asymmetries create a high risk of adverse selection and moral hazard. A key strategy used by business angels to minimize these risks is therefore to invest locally. This influences all stages of the investment process: deal flow, investment appraisal and post-investment relations.

Business angels find their investment opportunities from a variety of sources. Better known investors and angel groups receive unsolicited approaches from entrepreneurs on account of their visibility. Angels who do not have a public profile rely on their own personal networks of trusted friends, business associates and professional contacts for their deal flow. As Riding et al. (Citation1995) comment, ‘even if the principals of the firm are unknown to the investors, if the investor knows and trusts the referral source risk is reduced’. Deal referrers are passing judgement on the merits of the opportunity and so are putting their own credibility and reputation on the line. This reliance on trusted personal networks creates a local bias in both the investment opportunities that angels receive and those that pass their initial screening filter. This point is illustrated by one Philadelphia-based angel quoted by Shane (Citation2005, p. 22):

we have more contacts in the Philadelphia area. More of the people we trust are here in the Philadelphia area. So therefore we are more likely to come to some level of comfort or trust with investments that are closer.

The investment appraisal process involves three distinct stages – pre-screen, initial screening and detailed investigation (Mason & Botelho, Citation2018). The initial step of business angels is to assess investment opportunities for their ‘fit’ with their own personal investment criteria, knowledge of the sector and ability to add value to the business. In angel groups the initial screening stage is typically undertaken by the manager (often termed the ‘gatekeeper’; Paul & Whittam, Citation2010) where the ‘fit’ with the group’s investment focus (e.g., sector, stage, size of investment, existing investment portfolio) is a key consideration (Mason & Botelho, Citation2017). The location of the business is considered at this stage, with those that are judged to be ‘too far away’ more likely to be rejected regardless of their intrinsic merits (Mason & Rogers, Citation1997).

Angels and gatekeepers then undertake a quick review of those opportunities that fall within their investment criteria. Their aim at this point in the decision-making process is simply to assess whether the proposal has sufficient merit to justify devoting time to undertake a detailed assessment. The market, financial considerations, product/service and the entrepreneur are the key considerations at this stage (Harrison et al., Citation2015; Mason & Stark, Citation2004). Some angels will be flexible, willing to treat these criteria as compensatory and prepared to invest in ‘good’ opportunities that are located beyond their preferred distance threshold (Mason & Rogers, Citation1997), whereas others will regard them as non-compensatory (Feeney et al., Citation1999; Maxwell et al., Citation2011). The initial screening stage has a very high attrition rate with angels rejecting upwards of 90% of opportunities that they receive (Carpentier & Suret, Citation2015; Croce et al., Citation2017; Riding et al., Citation1995).

The minority of investment proposals that get through the initial screening stage are then subject to detailed appraisal. Whereas the focus at the initial screening stage is on verifiable attributes such as skills, experience and track-record of the entrepreneur, it is intangibles such as leadership abilities, trustworthiness and enthusiasm that are the focus at the due diligence stage (Brush et al., Citation2012; Maxwell et al., Citation2011; Mitteness et al., Citation2012; Riding et al., Citation2007). Trust is particularly important (Harrison et al., Citation1997). Business angels give considerable attention to key signals from entrepreneurs that indicate positive or negative displays of trust-based behaviours (Maxwell & Lévesque, Citation2014). Angels are ‘backing the horse, not the jockey’ (Harrison & Mason, Citation2017), hence people factors are the dominant reason why they reject investment opportunities (Mason et al., Citation2017).Footnote1

The geographical proximity between the angel and the potential investee business has an influence on two aspects of the investment appraisal. First, because of the emphasis on people factors – which reflects the early stage at which they invest – a critical aspect of the angel’s investment appraisal process requires face-to-face meetings with the entrepreneur. The travel time involved in meeting with the entrepreneur is therefore a potential influence on their decision whether to undertake a detailed investment appraisal. Second, business angels engage with the business after they have made the investment. This has two dimensions. They monitor their investee businesses, for example by taking a seat on the board, to minimize the risk of opportunistic behaviour by the entrepreneur. They also engage with their investee businesses to add value, including advice, sharing of networks, providing contacts, mentoring and coaching. Angels prefer to undertake these roles through personal interaction with the entrepreneurs (Ali et al., Citation2017). Physical separation decreases the likelihood of personal interaction which, in turn, reduces the effectiveness of monitoring and oversight and support, impedes information flow and tacit knowledge exchange and the development of close working relationships with their investee companies, all of which aggravate information asymmetries and agency-related problems. Angels will therefore take into account the level of involvement that is likely to be required and the associated travel time involved in visiting the business. To quote one angel: ‘a one day a week involvement is going to be closer than a one day a month involvement’ (Innovation Partnership, Citation1993). Not surprisingly, active investors give greater emphasis to proximity than passive investors (Sørheim & Landström, Citation2001). Proximity is particularly important in crisis situations where the investor needs to get involved in problem-solving. One of the investors in the study by Paul et al. (Citation2003, p. 323) commented ‘if there’s a problem I want to be able to get into my car and be there in the hour. I don’t want to be going to the airport to catch a plane’. However, angels will consider making long distance investments in situations where someone that they know and trust who is local to the potential investee business is co-investing with them (Shane, Citation2005).

The effect of distance on investment is mediated by two factors. First, the average investment distance increases with the size of business angel’s portfolio (Gvetadze et al., Citation2020; Harrison et al., Citation2015). This is likely to reflect the fact that more active investors exhaust the local pool of potential investment opportunities that meet their investment criteria and preferences and therefore have to expand their search space. A higher volume of investments made can also be interpreted as a surrogate for experience (Kelly & Hay, Citation1996, Citation2000), suggesting that experienced investors are better able to manage the higher information costs (information asymmetries, uncertainty, transaction costs of maintaining relationships) of non-local investments. Experienced business angels are also likely to have more geographically dispersed networks, hence their deal flow will have a significant non-local component and they will know individuals in various locations with whom they trust to undertake the due diligence and post-investment monitoring and can co-invest with them. Cowling et al. (Citation2021) present evidence that more experienced investors are much more willing to invest at a distance.

Second, locational context matters. Business angels generally only look for distant investments after local investment opportunities have been exhausted (Gvetadze et al., Citation2020). Investors in major centres of economic activity are therefore more likely to invest locally on account of the much denser and richer investment opportunities available in such locations (Cowling et al., Citation2021; Harrison et al., Citation2010). In Sweden 75–80% of the angel investment that originates in metropolitan regions is invested locally. The equivalent proportion in peripheral regions is around 25% on account of the limited availability of local investment opportunities (Avdeitchikova, Citation2009).

Investing across borders creates further unique challenges for angels. Political borders are a barrier to economic interaction, impacting on the movement of goods, services and people between countries. Globalization and the creation of economic and political unions between independent states and the creation of institutions to foster cross-border interactions have increased economic interaction across borders recent decades. But their impact varies significantly depending on the degree of cultural, racial and linguistic differences, political relations between the respective regions and the extent of economic disparity (Anderson & Wever, Citation2003).

Differences in legal, tax, regulatory and governance regimes, and the potential costs arising from the need to hire foreign lawyers and accountants and to translate documents all create obstacles for business angels in making investments in other countries (Shane, Citation2005). An EU-wide survey of business angels highlighted the lack of harmonized legal frameworks as a barrier to making cross-border investments (Ali et al., Citation2017). Tax creates a further impediment to cross-border investing. This has three aspects (Mollen, Citation2019b). First, is the taxation of start-ups in different countries (e.g., corporate tax, social taxation, etc). Second is the local taxation on the disposal of the disposal of the angel’s interest in their investee company. Third, and most influential are the fiscal incentives that governments offer business angels to stimulate investment activity in early stage businesses. A high proportion of business angels across Europe make use of these tax incentives (Ali et al., Citation2017). Evidence from both the UK and elsewhere suggests that tax incentives increase investment activity (British Business Bank, Citation2017; Carpentier & Suret, Citation2016; Denes et al., Citation2019) and increase angel returns (Harrison et al., Citation2020) although there is also evidence that they disproportionately attract inexperienced investors, distort resource allocation, predominantly to poor quality deals and has poorer exit outcomes (Carpentier & Suret, Citation2016; Denes et al., Citation2019; Harrison et al., Citation2020). However, with few exceptions, governments restrict tax incentives to individuals and businesses in their own jurisdictions, potentially discouraging angels from making investments in other countries. Government funding programmes that co-invest alongside business angels are also restricted to their own jurisdiction (Mollen, Citation2019a). The existence of different currencies creates additional risks arising from exchange rate fluctuations.

STUDY CONTEXT

The geographical context for this study is the island of Ireland, comprising Northern Ireland, which is part of the UK (with regulatory and governance structures that oversee the operation of its capital market controlled from London), and the Republic of Ireland. The Republic of Ireland has existed as a separate state since 1921, created in the context of increasing militant nationalism and unionism leading to sectarian civil war. In response, the UK government separated the six counties in the north east of the island which remained in the UK (but with its own parliament) and negotiated a new independent Irish Free State (Gibbons, Citation2020; Townshend, Citation2021). However, the actual border – which is 500 km in length – was arbitrary, lacking any correspondence to the realities of economic and social interaction. ‘The Troubles’ which began in the late 1960s turned the border into a military zone. But ‘having been hardened by violence’ the border ‘was softened by the peace’ which followed the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 and the ending of paramilitary campaigns (McNaney, Citation2019). With the creation of the European Market which both the UK and Ireland joined in 1993, the border has receded in peoples’ imagination (Smyth, Citation2019), becoming ‘seamless and frictionless’, resulting in a significant growth in trade and population flows (Daly, Citation2017) and, in the words of one commentator, ‘a blurring of the lines between British, Irish, Northern Ireland and European identities’ (Smyth, Citation2019). Under the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol of the UK’s Brexit withdrawal agreement Northern Ireland would in effect remain in the EU’s single market for goods and subject to its custom rules, with border controls with the rest of the UK, in order maintain an open border on the island of Ireland and safeguard the peace process.

This study seeks to contribute to the business angel cross-border investment policy agenda with evidence on the scale of, and constraints on, cross-border angel investing on the island of Ireland. Support for angel investing across the island of Ireland is provided by the Halo Business Angel Network (HBAN). HBAN was established in 2007 as a joint initiative of Enterprise Ireland, InterTrade Ireland and Invest Northern Ireland to develop angel investment across the island of Ireland by supporting existing angel networks and syndicates, assisting with the formation of new ones and increasing the number of business angels. Its membership currently comprises 10 all-island Syndicate groups, including HBAN Ulster which operates in Northern Ireland and five regional Business Angel Networks.Footnote2

DATA SOURCES

The challenges in identifying businesses angels are well-rehearsed (Avdeitchikova et al., Citation2008; Farrell et al., Citation2008; Mason, Citation2016; Mason & Harrison, Citation2008). Angel investing is primarily an informal activity that is largely unreported and unrecorded. As Wetzel (Citation1983, p. 26) – the pioneer of angel research – observed, the total population of business angels ‘is unknown and probably unknowable’. It is therefore simply not possible to undertake research on the basis of a representative sample. Instead, researchers have identified angels through a variety of imperfect sources, often relying on intermediaries in the market (e.g., angel networks) which creates the potential for bias (e.g., to more visible and more active angels, those who are members of angel groups) but with no way in which to test for the representativeness of the samples that have been generated. Our approach also involved sourcing angels through intermediaries.

This study is based on information collected in 2015 from just under 100 business angels.Footnote3 An online survey attracted responses from 74 individuals, 56 in the Republic of Ireland and 18 in Northern Ireland, 54 of whom were active investors and 20 were nascent angels looking to make their first investment. Respondents were concentrated in the main urban centres of Dublin (26), Belfast (11) and Cork (10). The online survey was promoted and distributed by a variety of methods including through HBAN, Halo NI and Enterprise Ireland (economic development agency), referrals from financial advisers and other professional intermediaries, and promotion via social media. Because it is unknown how many individuals were approached by these organizations to complete the survey it is not possible to calculate a response rate. This survey collected information on the personal characteristics of respondents, their experience as business angels, post-investment involvement with their investee businesses, constraints on investing and views on the investment landscape and support available. This was complemented by semi-structured interviews with 21 business angels, 15 in the Republic of Ireland and 6 in Northern Ireland, from a list of 31 contacts provided by HBAN, Halo NI and Enterprise Ireland. These were conducted by telephone. The interviews involved a ‘deep dive’ into the topics covered in the online survey. Just one of these respondents had yet to make any investments.

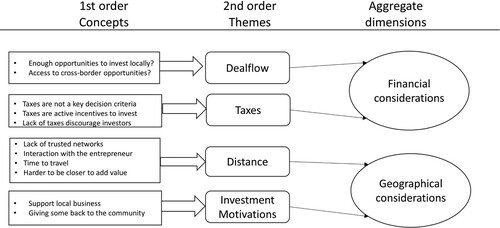

The interview data was analysed by the authors. In the first step of the analysis, the interview transcripts were read several times and summary reports were generated for each interview. This follows the approach suggested by Miles and Huberman (Citation1994). In the second step, open coding was used to identify the first-order concepts. At this stage, two of the authors compared first-order concepts to identify potential. The third step involved a comparison of the coding to identify how similar or distinct the first-order categories were (axial coding) (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). This enabled the first-order concepts to be deduced into second-order themes grounded in angel investment literature (investment motivations, deal flow, etc.). As a final step the authors combined similar second-order themes into broader aggregate dimensions (Gioia et al., Citation2013).

Profile of respondents

Respondents to the online survey conform to the well-established characteristics of angel investors reported other studies (e.g., BBB, Citation2020; Mason & Botelho, Citation2014). They were predominantly male (91%) and middle aged (69% were aged 45–64). They were well educated: 80% had university degrees and 63% had professional qualifications (mainly chartered accountants and engineers). The majority were experienced entrepreneurs: 82% had started at least one business (32% had started three or more businesses) and one-third had led a management buyout or buy-in. In addition, 40% have held senior positions in large firms. Just under two-thirds of ‘active’ respondents made their first investment in the past five years (63%), and 32% had started investing less than two years prior to the survey. This profile is replicated in the sample of angels who participated in the telephone interviews.

The investment activity of the online respondents exhibits a skewed distribution that is also found in other studies, being characterized by a small number of ‘serial business angels’ investing large amounts in multiple businesses, and a ‘long tail’ of those who have made just one or two investments businesses, with a lower median size of investment. There were 14% of angels who had made more than 10 investments. These investors accounted for 40% of the total investments made by respondents. It is noteworthy in view of our earlier discussion that angels are increasingly involved in financing the initial stages of scale-up that the majority of angels (59%) had made follow-on investments in their investee companies. There are no significant differences in the characteristics of respondents to the online survey who were based in Northern Ireland with those in the Republic of Ireland.

The similarities between this profile of the online and interviewee respondents and that of other studies suggests that no significant source of bias is present. However, a high proportion of business angels were members of a network or group – 73% of respondents to the online survey and 90% of interviewees. To a large extent this reflects the distribution and promotional channels used to advertise the online survey and identify interviewees, an approach that is widely used in angel research. But it also reflects the growth of more formalized angel networks and groups (Mason et al., Citation2016) that have also developed on the island of Ireland with government support.

ANGEL INVESTMENT ACTIVITY: AN OVERVIEW

The evidence from the online survey suggests that business angels on the island of Ireland are generally ‘reactive’ in identifying investment opportunities, preferring to use network events, direct approaches from entrepreneurs, and referrals from friends and business associates. Angel groups and networks play a key role as a source of investment opportunities, cited by 51% of angels. Friends and business associates were cited by 46%, while 39% cited approaches from entrepreneurs. Only a small number of business angels identified ‘direct’ opportunities flowing from innovation-support organizations, such as accelerators and science parks. However, there are some differences between investors in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland in the relative importance of their main sources of information on deal flow. The most frequently cited sources by angels in the Republic of Ireland were the angel groups that they were affiliated with (55%) and referrals from friends and business associates (43%). For Northern Ireland angels the most frequently cited sources were approaches from entrepreneurs (67%) and referrals from friends and business associates (56%). One-third of Northern Ireland angels also cited science parks and universities as an important source of deal flow whereas no angels in the Republic of Ireland mentioned this source.

The volume of investment opportunities was generally not regarded by respondents to the online survey as a barrier to making more investments. However, issues surrounding the poor quality of the opportunities (cited by 40%) and the unrealistic expectations of entrepreneurs (e.g., regarding valuation and deal terms) (cited by 52%) did constrain higher levels of investing. Consistent with this evidence, the telephone interviews indicated that the volume of opportunities was regarded generally as sufficient, but the quality was variable.

In aggregate, the active angels amongst the respondents to the online survey had invested in a total of 250 businesses, 22% of which had subsequently attracted follow-on investments from these angels. Their investments had a particular focus on ICT and related digital industries. This reflects both the strength of the technology base (especially around Dublin), and the consistent focus of business angels investors on technology-based industries (with 83% of ‘active’ business angels indicating they typically invest in technology-intensive industries). However, most respondents indicated that they invest in multiple industries. Less than one-fifth of business angels reported that they typically make investments in only one industry, generally an industry in which they had deep experience. This picture was consistent in the interviews, where most business angels indicated that they focused on a handful of, often related, industries. Those business angels interviewed who did not have this focus were generally from a professional services background, and therefore had less industry-specific experience and expertise. The majority of respondents were actively involved with their investee companies. Over half (53%) described themselves as being active in every investment, 35% indicated that the extent of their involvement varied according to the nature of the investment and the needs of the business, and just 12% described themselves as passive investors.

Angels based in Northern Ireland were slightly more active than their counterparts in the Republic of Ireland. They accounted for 30% of the respondents but 38% of investments (96) and 41% of the amount invested (€8.8 million). Those angels based in the Republic of Ireland comprised 70% of respondents but made only 62% of investments (154) and accounted for only 59% of the amount invested (€21.3 million). Northern Ireland investors also had larger investment portfolios than those in the Republic of Ireland.

CROSS-BORDER INVESTING

The level of cross-border investing across the island of Ireland amongst business angels was, in absolute terms, modest. In the online survey just five of the 54 respondents (9%) who had made investments had invested in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, while one Northern Ireland angel had invested in the Republic of Ireland (). In the interviews just three of the 20 angels who had made investments had made cross-border investments (15%). ‘Within jurisdiction’ investing therefore dominates investment activity. The scale of cross-border investing on the island of Ireland is similar to that reported in the EIF angel partners (Gvetadze et al., Citation2020) and European Commission (Ali et al., Citation2017) studies of angel investing in the EU but higher than reported in the other studies cited earlier.

Table 1. Location of investments.

Interviewees identified four main reasons for not making cross-border investments, only one of which was related to the effect of the border (). Indeed, eight (38%) indicated that they would consider making cross-border investments. The most frequently cited constraint was simply associated with deal flow: the majority of angels had either not seen any investment opportunities on the other side of the border, or the opportunities that they had seen were considered to be poor quality. Just 6% of Northern Ireland angels said that they saw investment opportunities in the Republic of Ireland. The proportion of Republic of Ireland angels who saw investment opportunities in Northern Ireland was slightly higher at 13%. One Republic of Ireland angel commented that ‘Northern Ireland deals have less visibility than those in the Republic of Ireland.’ Another noted that, ‘I am open to investing in Northern Ireland but lack knowledge on opportunities.’ A Northern Ireland based angel noted that he had seen Republic of Ireland opportunities at Halo meetings ‘but none were right for me’. The availability of sufficient local investment opportunities is a further constraint on cross-border investing. One Republic of Ireland angel observed that he sees sufficient investment opportunities in the Republic and so ‘doesn’t need to look seriously into Northern Ireland opportunities’.

The distances involved, particularly between the major conurbations of Dublin, Cork and Belfast, where many of the business angels are based, is a further significant constraint on cross-border investing. One investor in the Republic of Ireland based in Dublin commented that, ‘I have nothing against Northern Ireland opportunities in principle, but it is the distance that puts me off. I’m even reluctant to invest in Cork and Galway because they’re too far from Dublin’. Distance was a particular constraint on the appraisal process. One angel observed that, ‘getting to know the entrepreneur is critical so extra distance would be a hindrance … ’. Another noted that he prefers, ‘not to travel more than one hour from home or work to see potential investments’. Investing over a long distance also has a negative effect on the post-investment relationship:

I want to be a coach/mentor to entrepreneurs so proximity is essential.

Geographically, it’s an issue to invest in Northern Ireland from Cork. Proximity to the investee business makes a difference, as it’s all about on-going relationships.

Tax incentives is a further constraint on cross-border investing. Investors in the Republic of Ireland have access to the Enterprise Investment Incentive (EII) while those in Northern Ireland can qualify for the UK’s Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS) and Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme (SEIS).Footnote4 Almost half (46%) of the business angels responding to the online survey indicated that they would stop making investments if all tax incentives were removed, and 34% reported that they would scale back their investing (). Whilst this is a response to a hypothetical scenario, the findings do highlight the importance of tax to the business angel community. Angels in Northern Ireland were more likely to say that they would cease their investment activities if tax incentives were ended than those in the Republic of Ireland (56% cf. 41%). This reflects the greater benefits offered by the UK’s SEIS and EIS compared with the Republic of Ireland’s EII scheme (SQW, Citation2016, fig. 5.1).Footnote5 Business angels in the Republic of Ireland regarded the EII less favourably to the SEIS/EIS, with the lack of relief on capital gains seen as a particular disadvantage. However, angels in both jurisdictions were unanimous that whereas the existence of tax incentives had an influence on how much of their investment portfolio that they would allocate to early stage businesses they did not influence their investment decisions. This point was well made by one angel:

on the broad level of deciding how many investments to make in a year tax is important. But when evaluating a specific opportunity tax is not important. The quality and likelihood of success of a given opportunity are much more important.

Table 2. Influence of tax incentives on business angels.

The inability of angels to benefit from tax incentives for investments that they make in companies located in another country is therefore a further constraint on cross-border investments. Northern Ireland investors making investments in the Republic of Ireland would not qualify for SEIS/EIS relief on these investments, while Republic of Ireland angels would not be eligible for tax incentives on investments that they made in businesses located in Northern Ireland. A total of 20 out of 63 business angels in the online survey indicated that a lack of, or insufficiently attractive, tax incentives had acted as a constraint to cross-border investing. One Northern Ireland angel commented that, ‘I am more likely to invest in Great Britain than the Republic of Ireland opportunities because of tax.’ Another stated that, ‘I would invest in the Republic if there was a cross-border agreement on tax.’ But of the six business angels who had actually invested outside their jurisdiction of residence, just one identified tax as a constraint.

Those angels who have made cross-border investments are not distinctive in terms of age, education or entrepreneurial experience. However, they are significantly more experienced investors (years investing and number of investments) and the amount that they have invested is larger. In terms of sources of deal flow, angels who have made cross-border investments place greater importance on referrals from friends and business associates (100% cf. 42%), approaches from entrepreneurs (67% cf. 35%) and their own research (50% cf. 15%) and give less importance to membership of angel groups, syndicates and networks (0% cf. 60%). Angels who have made cross-border investments also have larger investment portfolios and spend less time on angel investing and with their investee companies. Angels who make cross-border investments also have more exits, more positive exits (38% cf. 29%) and fewer negative exits (31% cf. 45%) (). There was no difference in the proportions of angels who were members of an angel syndicate. This suggests that those angels who make cross-border investments have sufficiently strong personal networks that they are not reliant on membership of angel groups, syndicates and networks to source their deal flow.

Table 3. Investment activity of business angels who have made cross-border investments.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The need to encourage cross-border investing by business angels – the main source of risk capital for start-ups – has been identified as an important policy objective for the EU as part of its broader strategy to create a more unified funding market overcome the financial constraints that contribute to its deficiency in start-ups and scale-ups compared with the United States. However, there is little empirical evidence that can inform policymakers on the factors that discourage business angels from making cross-border investments, the feasibility of intervention and what interventions might be effective. This paper presents evidence from the island of Ireland. It has highlighted the limited scale of cross-border investing by business angels on the island or Ireland, a geographical context in which there is currently a largely frictionless border. Those angels who have made cross-border investments are more experienced, with larger investment portfolios, make larger investments and have had more exits. This might imply that cross-border investing will increase as Europe’s angel market matures.

The evidence also indicted that many angels are open to the possibility of making cross-border investments. However, most angels are unaware of investment opportunities on the other side of the border. Moreover, most have sufficient investment opportunities in their own localities and so do not need to look further afield to invest. And distance compromises key aspects of the investment process, notably appraisal and the ability to support their investee companies. The existence of the border is less significant as a barrier than these broader effects of distance on angel investing.

The key effect of the border is that each of the jurisdictions offer tax incentives to business angels which are only available to angels who are resident in that country (Republic of Ireland, United Kingdom) and for investments in businesses located in that country. Angels in Northern Ireland who invest in businesses located in the Republic of Ireland would lose the considerable tax benefits offered under the EIS/SEIS and would not qualify for the tax incentives available to Republic of Ireland angels investing in their home country. Similarly, Republic of Ireland angels are not eligible for EIS/SEIS relief if they invest in Northern Ireland. And because of asymmetries in the tax incentives available in the two jurisdictions, with the UK’s SEIS/EIS much more generous than the Republic of Ireland’s EII, Northern Ireland angels have a greater disincentive to make cross-border investments that angels in the Republic of Ireland.

The majority of respondents considered that tax incentives have a positive impact on the number of investments that they make and the overall amount that they invest, although not on their investment decisions. Governments therefore have two policy options for stimulating cross-border investing. They could extend the eligibility of tax incentives to business angels based in other countries in order to increase the supply of finance available to their own entrepreneurs. The only example of this approach is Germany’s INVEST scheme which offers a subsidy to angels to purchase shares and an exit grant (to offset capital gains tax) that are available to permanent residents in counties in the EEA (Ali et al., Citation2017). However, investors may favour investing in countries that offer the most generous tax incentives. Hence, allowing Northern Ireland angels to qualify of tax relief under the EII may not significantly increase cross-border investing because it offers less generous incentives than the EIS/SEIS. Alternatively, Government could follow the example of France: its tax incentives apply to residents making investments in companies located in any EU member state (AFME, Citation2017). However, given the competition between European countries for ‘start-up supremacy’ (Mollen, Citation2019a), governments would be concerned that it would result in an outflow of finance – even though the capital gains made from investments in another country might be reinvested in domestic companies.

However, there are two reasons for suggesting that the introduction of tax incentives to encourage business angels to make cross-border investments might not be an appropriate form of intervention. First, there is currently no systematic evidence that tax incentives for business angels are effective, with expenditure (in terms of tax foregone) greater than tax revenues when additionality and displacement are considered, or in terms of the performance of investee businesses. It is also suggested that they distort the market, attracting inexperienced investors (‘dumb money’) and inflate company valuations (Carpentier & Suret, Citation2016: Denes et al., Citation2019). Second, even if tax incentives are designed to encourage cross-border investing the constraints on making long distance investments remain, hence they may not change the deep-seated preference of angels to invest locally. Other interventions are therefore required.

Our evidence shows that a significant minority of angels are not opposed to making cross-border investments but are constrained from doing so because they lack information on investment opportunities and networks of trusted individuals to refer deals and could co-invest with them. Hence, complementary initiatives that improve the visibility of investments in other countries, ensure that such opportunities are investment ready, and build trusting relationships between angels in different jurisdictions are also essential. This requires that existing business angel networks (BANs) go beyond simply providing information on investment opportunities to angels in neighbouring states and play a more proactive role to facilitate the development of personal relationships between angels in different countries.

Governments typically provide financial support to BANs to enable them to improve market efficiency by connecting angels with entrepreneurs seeking finance (Mason, Citation2009; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2011). However, evidence on the cost-effectiveness of BANs is mixed (Lahti & Keinonen, Citation2016). A more effective approach is for governments to support the creation of angel groups by subsidizing their operating costs. Angel groups – which typically have 20–75 members (but some are larger) – operate by aggregating the investment capacity of individual angels. They have a manager (‘gatekeeper’) whose key roles are to undertake the initial screening of investment opportunities and to manage investor engagement. Many angels have been attracted to join angel groups because of the reduction in risk that arises from investing as part of a group, notably the ability to develop a diversified portfolio of investments and providing access to group skills and knowledge to evaluate investment opportunities and provide more effective post-investment support. A further attraction is the opportunity to learn from more experienced angels. They have also attracted high net worth individuals (HNWIs) who would not otherwise invest in emerging companies, for example, because they lack the time, referral sources, investment skills or the ability to add value. Thus, angel groups are able to attract and mobilize funds that might otherwise have been invested elsewhere (e.g., property, stock market, collecting: Mason & Harrison, Citation2000). By pooling the financial resources of their members as well as being credible co-investors with other investors (including crowdfunding platforms) angel groups have been able to make bigger investments, thereby filling the funding gap that has arisen as VC funds have consistently raised their minimum size of investment and largely abandoned the early stage market. However, as the evidence in the paper shows, even when angels are members of groups they still predominantly make local investments.

Business angels typically only make cross-border investments if trusted relationships are in place with local lead investors in the country in which the investee business is located (Mollen, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; OECD, Citation2011; Viimsalu, Citation2014). The Nordic Angel Programme (Citation2019), which has as one of its goals to promote cross-border investment across the Nordic region, comments that ‘angel investing, especially cross-border investing, is always about building trust … so unless you trust a local co-investor and his or her relationship with the start-up team the natural reaction would be to say no to the investment’. Angel groups that are organized on a chapter model, a common structure in the United States (e.g., Angel Capital Group, Tech Coast Angels), are able to overcome these factors that inhibit long distance investing. There are now angel groups that operate an international chapter model (e.g., Keiretsu). In the chapter model groups operate in two or more locations under the same brand management (but have their own gatekeeper), use standard procedures for generating deal flow, screening and due diligence, and run common training sessions, seminars and other events which create a safe space to build collaborate social relationships and develop trust between members across the group. This model gives individual angels the opportunity to make investments in distant locations, including other countries, by providing them with screened deal flow that they can have confidence in and facilitating co-investment alongside angels who are members of other chapters with whom they have developed trusting relationships. This is, in effect, the new approach that HBAN has adopted, replacing their partnership model comprising separate organizations operating in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland with an all-Ireland structure with the same model, platform and process in each territory. Government support for this model of angel investing might therefore offer a more effective approach to the facilitation of cross-border investing by business angels.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper is based on data collected for a study of the business angel market on the island of Ireland that was conducted by SQW on behalf of InterTrade Ireland. We are grateful to John Phelan, All-Island Director of the Halo Business Angel Network (HBAN), for providing us with information on how the organization has evolved since the study was undertaken. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors alone and may not be endorsed by the sponsors of the study.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1992930)

Notes

1. Typical of this approach is one business angel speaking at the NACO West virtual summit (31 March 2021) who commented that ‘as an angel investor the only criteria is the founder’.

3. The study was therefore undertaken prior to the Brexit vote, hence this was not an issue that was covered in the research. Although it would have been of interest to have captured the views of angels on the likely effect of Brexit on where they invest, this might have dominated responses, hence limiting the potential generalizability of the findings.

4. The main benefits of the UK’s EIS/SEIS compared with the Republic of Ireland’s EII are: (1) the tax relief under EIS/SEIS is available up-front, whereas only 30% of the EII tax relief is available in year 1 with the additional 10% after three years; (2) the lifetime limit of investment under the EII is €15 million, whereas EIS/SEIS does not have any lifetime limit; and (3) in the case of EIS/SEIS there is no capital gains tax on the disposal of shares (if held for a minimum of three years), whereas EII investments are subject to capital gains tax on disposal (SQW, Citation2016).

5. The SEIS was ranked by the European Commission in 2017 as the best angel tax incentive across 36 sample countries in terms of good practice. The following features of the scheme were specifically highlighted: loss relief, investee company targeting (age and sector exclusions), relief restricted to newly issued ordinary shares, provision for investors to participate in the management of the investee company and a cap on the maximum tax relief available to keep the scheme affordable (European Commission, Citation2017).

REFERENCES

- AFME. (2017). The shortage of rick capital for Europe’s high growth companies. https://www.afme.eu/globalassets/downloads/publications/afme-highgrowth-2017.pdf

- AFME. (2018). Capital markets union: Measuring progress and planning for success. https://www.afme.eu/globalassets/downloads/publications/afme-cmu-kpi-report-3.pdf

- Ali, S., Berger, M., Botelho, T., Duvy, J. N., Frencia, C., Gluntz, P., Delater, A., Lichy, G., Losso, J., & Pellens, M. (2017). Understanding the nature and impact of the business angels in funding research and innovation. ZEW-Gutachten und Forschungsberichte, Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforchung (ZEW).

- Anderson, J., & Wever, E. (2003). Borders, border regions and economic integration: One world, ready or not. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 18(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2003.9695599

- Atomico. (2020). The state of European tech 2020. https://2020.stateofeuropeantech.com/chapter/state-european-tech-2020/

- Avdeitchikova, S. (2009). False expectations: Reconsidering the role of informal venture capital in closing the regional equity gap. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 21(2), 99–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620802025962

- Avdeitchikova, S., Landström, H., & Månsson, N. (2008). What do we mean when we talk about business angels? Some reflections on definitions and sampling. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 10(4), 371–394. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691060802351214

- British Business Bank. (2017). Business angel spotlight. Research by IFF Research and RAND for British Business Bank together with UK Business Angels Association. https://british-business-bank.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Business-Angels-2017-Research-Findings-compressed-FINAL.pdf

- British Business Bank. (2020). The UK business angel market 2020. Research by IFF Research and RAND for British Business Bank together with UK Business Angels Association. https://www.british-business-bank.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/20201008-BBB-Business-Angels-Report-Final.pdf

- Brush, C., Edelman, L. F., & Manolova, T. S. (2012). Ready for funding? Entrepreneurial ventures and the pursuit of angel financing. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 14(2–3), 111–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2012.654604

- Carpentier, C., & Suret, J.-M. (2015). Angel group members’ decision process and rejection criteria: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(6), 808–821. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.04.002

- Carpentier, C., & Suret, J.-M. (2016). The effectiveness of tax incentives for business angels. In H. Landström, & C. Mason (Eds.), Handbook of research on business angels (pp. 327–353). Edward Elgar.

- Cowling, M., Brown, R., & Lee, N. (2021). The geography of business angel investment in the UK: Does local bias (still) matter? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20984484

- Croce, A., Tenca, F., & Ughetto, E. (2017). How business angel groups work: Rejection criteria in investment evaluation. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 35(4), 405–426. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615622675

- Daly, M. (2017). Brexit and the Irish Border: Historical context. British Academy and Irish Academy/Academh Ríoga na hÉireann. https://www.britac.ac.uk/sites/default/files/BrexitandtheIrishBorderHistoricalContext_0.pdf

- Denes, M., Wang, X., & Xu, T. (2019). Financing entrepreneurship: Tax incentives for early-stage investors. http://jhfinance.web.unc.edu/files/2019/12/2020_Denes_Wang_Xu__Financing_Entrepreneurship_Tax_Incentives_for_Early_Stage_Investors.pdf

- Duruflé, G., Hellman, T., & Wilson, K. (2018). From start-up to scale-up: Policies for the financing of high-growth ventures. In C. Mayer, S. Micossi, M. Onado, M. Pagano, & A. Polo (Eds.), Finance and investment: The European case (pp. 179–219). Oxford University Press.

- EBAN. (2020). European early stage market statistics 2019. https://www.eban.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/EBAN-Statistics-Compendium-2019.pdf

- European Commission. (2012). Report of the Chairman of the Expert Group on the Cross Border Matching of Innovative Firms with Suitable Investors. http://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regexpert/index.cfm?do=groupDetail.groupDetailDoc&id=6008&no=1

- European Commission. (2017). Effectiveness of tax incentives for venture capital and business angels to foster the investment of SMEs and start-ups: Final report. Working Paper No. 68. European Commission.

- European Investment Bank (EIB). (2019). European Investment Bank investment report 2019/2020: Accelerating Europe’s transformation. EIB.

- Farrell, E., Howorth, C., & Wright, M. (2008). A review of sampling and definitional issues in informal venture capital research. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 10(4), 331–353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691060802151986

- Feeney, L., Haines, G. H., & Riding, A. L. (1999). Private investors’ investment criteria: Insights from Qualitative data. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 1(2), 121–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/136910699295938

- Ferriter, D. (2019). The border: The legacy of a century of Anglo-Irish politics. Profile.

- Gibbons, I. (2020). Partition: How and why Ireland was divided. Haas.

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Gvetadze, S., Pal, K., & Torfs, W. (2020). The business angel portfolio under the European Angels Fund: An empirical analysis. Working Paper No. 2020/62. EIF Research and Market Analysis.

- Harrison, R., & Mason, C. (2017). Backing the horse or the jockey? Due diligence, agency costs, information and the evaluation of risk by business angel investors. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 15(3), 269–290.

- Harrison, R. T., Bock, A. J., & Gregson, G. (2020). Stairway to heaven? Rethinking angel investment policy and practice. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 14, article e00180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2020.e00180

- Harrison, R. T., Dibben, M. R., & Mason, C. M. (1997). The role of trust in the informal investor’s investment decision: An exploratory analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 21(4), 63–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879702100405

- Harrison, R. T., Mason, C. M., & Robson, P. (2010). Determinants of long-distance investing by business angels in the UK. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 22(2), 113–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620802545928

- Harrison, R. T., Smith, D., & Mason, C. M. (2015). Heuristics, learning and the business angel investment decision making process. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 27(9–10), 527–554. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2015.1066875

- Helsinki Business Hub. (2020). What we learned about cross-border angel investing from our Angel track. https://www.helsinkibusinesshub.fi/what-we-learned-about-cross-border-angel-investing-from-our-angel-track/

- High Level Forum on the Capital Markets Union. (2020). A new vision for Europe’s capital markets: Final report. European Union. https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/cmu-high-level-forum_en#200610

- Innovation Partnership. (1993). Private investor networks: A study commissioned by the National Westminster Bank plc. The Innovation Partnership.

- Kelly, P., & Hay, M. (1996). Serial investors and early stage finance. Journal of Entrepreneurial and Small Business Finance, 5, 159–174.

- Kelly, P., & Hay, M. (2000). ‘Deal-makers’: Reputation attracts quality. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 2(3), 183–202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691060050135073

- Kraemer-Eis, H., Signore, S., & Prencipe, D. (2018). The European venture capital landscape: An EIF perspective, Volume I: The impact of EIF on the VC ecosystem. Working Paper No. 2016/34. http://www.eif.org/news_centre/publications/eif_wp_34.pdf

- Lahti, T., & Keinonen, H. (2016). Business angel networks: A review and assessment of their value to entrepreneurship. In H. Landström, & C. Mason (Eds.), Handbook on research on venture capital, Volume 3: Business angels (pp. 354–378). Edward Elgar.

- Mason, C. (2016). Researching business angels: Definitional and data challenges. In H. Landström, & C. Mason (Eds.), Handbook on research on venture capital, Volume 3: Business angels (pp. 25–52). Edward Elgar.

- Mason, C., & Botelho, T. (2014). The 2014 Survey of Business Angel Investing in the UK: A changing market place. http://www.gla.ac.uk/media/media_362647_en.pdf

- Mason, C., & Botelho, T. (2017). Comparing the initial screening of investment opportunities by business angel group gatekeepers and individual angels. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2941852

- Mason, C., & Botelho, T. (2018). Early sources of funding (2): business angels. In L. Alemany, & J. Andreoli (Eds.), Entrepreneurial finance: The art and science of growing ventures (pp. 60–96). Cambridge University Press.

- Mason, C., Botelho, T., & Harrison, R. (2016). The transformation of the business angel market: Evidence and research implications. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 18(4), 321–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2016.1229470

- Mason, C., Botelho, T., & Zygmunt, J. (2017). Why business angels reject investment opportunities: It is personal? International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 35(5), 519–534. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242616646622

- Mason, C. M. (2009). Public policy support for the informal venture capital market in Europe: A critical review. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 27(5), 536–556. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242609338754

- Mason, C. M., & Harrison, R. T. (2000). Influences on the supply of informal venture capital in the UK: An exploratory study of investor attitudes. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 18(4), 11–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242600184001

- Mason, C. M., & Harrison, R. T. (2008). Measuring business angel investment activity in the United Kingdom: A review of potential data sources. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 10(4), 309–330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691060802380098

- Mason, C., & Rogers, A. (1997). The business angel’s investment decision: An exploratory analysis. In D. Deakins, P. Jennings, & C. Mason (Eds.), Entrepreneurship in the 1990s (pp. 29–46). Paul Chapman.

- Mason, C., & Stark, M. (2004). What do investors look for in a business plan? A comparison of the investment criteria of bankers, Venture Capitalists and Venture Capitalists. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 22(3), 227–248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242604042377

- Maxwell, A. L., Jeffrey, S. A., & Lévesque, M. (2011). Business angel early stage decision making. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(2), 212–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.09.002

- Maxwell, A. L., & Lévesque, M. (2014). Trustworthiness: A critical ingredient for entrepreneurs seeking investors. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(5), 1057–1080. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00475.x

- McNaney, J. (2019). That damnable inventor. Dublin Review of Books, issue 112 (June). http://www.drb.ie/essays/that-damnable-invention

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis – An expanded source book. Sage.

- Mitteness, C. R., Baucus, M. S., & Sudek, R. (2012). Horse vs. jockey? How stage of funding process and industry experience affect the evaluations of angel investors. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 14(4), 241–267. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2012.689474

- Moehr, O. (2017). Venture capital in Europe: State of play. http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/venture-capital-in-europe-state-of-play

- Mollen, R. (2018a). Can we build cross-border angel investment in Europe? https://www.leadingedgeonly.com/article/can-we-build-cross-border-angel-investment-in-europe-

- Mollen, R. P. (2018b). Constraints for cross border angel investing in Europe. EBAN. http://www.eban.org/article-robert-p-mollen-can-build-cross-border-angel-investment-europe

- Mollen, R. (2019a). Can European angels fly cross-border? https://www.leadingedgeonly.com/blogs/can-european-angels-fly-cross-border-

- Mollen, R. (2019b). US Angels can fly cross-border. https://www.leadingedgeonly.com/article/us-angels-can-fly-cross-border

- Morrissette, S. G. (2007). A profile of business angels. Journal of Private Equity, 10(3), 52–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3905/jpe.2007.686430

- Nordic Angel Program. (2019). What is cross-border investments made of? https://www.nordicangelprogram.com/news/what-is-cross-border-investments-made-of

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2011). Financing high-growth firms: The role of angel investors. OECD Publ.

- Paul, S., & Whittam, G. (2010). Business angel syndicates: An exploratory study of gatekeepers. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 12(4), 241–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691061003711438

- Paul, S., Whittam, G., & Johnston, J. (2003). The operation of the informal venture capital market in Scotland. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 5(4), 313–335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369106032000141931

- Riding, A. L., Duxbury, L., & Haines, G., Jr. (1995). Financing enterprise development: Decision-making by Canadian angels. School of Business, Carleton University, Ottawa.

- Riding, A. L., Madill, J. J., & Haines, G. H., Jr. (2007). Investment decision making by business angels. In H. Landström (Ed.), Handbook of research on venture capital (pp. 332–346). Edward Elgar.

- Shane, S. (2005). Angel investing: A report for the federal reserve banks of Atlanta, Cleveland, Philadelphia, Kansas City and Richmond. Wetherhead School of Management, Case Western Reserve University.

- Smyth, J. (2019, January 31). Return of Irish border would threaten golden age of peace. Financial Times.

- Sørheim, R., & Landström, H. (2001). Informal investors – A categorisation with policy implications. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 13(4), 351–370. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620110067511

- SQW. (2016). Funding for growth: The business angel market on the island of Ireland. InterTrade Ireland. https://intertradeireland.com/insights/publications/funding-for-growth-the-business-angels-market-on-the-island-of-ireland/

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Sage.

- Sullivan, M., & Miller, A. (1996). Segmenting the informal venture capital market: Economic, hedonistic, and altruistic investors. Journal of Business Research, 36(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(95)00160-3

- Townshend, C. (2021). The partition: Ireland divided, 1885–1925. Penguin.

- Viimsalu, S. (2014). Facilitating business angel investments. Paper presented at Eurofenix, Autumn, 16–19. file:///C:/Users/masco959/Downloads/SR_-_Estonia_-_2014_Autumn_-_Facilitating_Business_Angel_Investments_by_Signe_VIIMSALU.pdf

- Wetzel, W. E., Jr. (1983). Angels and informal risk capital. Sloan Management Review, summer, 23–34.