ABSTRACT

This study looks to understand the dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems by exploring the complex interactions between multiple stakeholders operating at different levels of governance. Drawing on network governance, it provides new insights into collective and individual actions taken to coordinate and implement enterprise support. Through an in-depth study of the Tay Cities Region in Scotland, UK, the study details the relational organizing various stakeholders undertake to form, structure and interrupt the entrepreneurial ecosystem network. Through effective coordination, the region attracts inward investment and creates new valuable programmes, which increases the efficacy of enterprise support.

INTRODUCTION

A vibrant regional entrepreneurial ecosystem (EE) can lead to increased entrepreneurial performance, the creation of jobs and economic growth (Audretsch & Belitski, Citation2021; Content et al., Citation2020; Szerb et al., Citation2019). EEs have been defined as a combination of political, economic and cultural elements in a region that support the development and growth of innovative start-ups, where a ‘set of interdependent actors and factors coordinate in such a way that they enable productive entrepreneurship’ (Stam, Citation2015, p. 1764). Governments support EEs through policies that encourage entrepreneurial development (Spigel, Citation2017). They can act as proponents creating effective institutions that promote and produce new ventures by using their procurement spend to incentivise entrepreneurship (Isenberg, Citation2010; Orser et al., Citation2019). Similarly, enterprise support organizations (ESOs) help new ventures overcome their lack of resources and market access which is critical for an EE to function (Spigel, Citation2016). Yet, while the importance of various stakeholders (entrepreneurs, governments and ESOs) is undeniable, understanding their coordinating activities, governing structures and development has become an important focus for scholars (Autio & Levie, Citation2017; Colombelli et al., Citation2019; Colombo et al., Citation2019).

Given the role of various actors in the governance of EEs, the importance of multiple stakeholders in developing and implementing enterprise policy has gained recent traction (Arshed, Citation2017; Arshed et al., Citation2016). Policy formation typically employs a ‘top-down’ approach designed to address specific market failures (Arshed et al., Citation2014; Autio & Levie, Citation2017). However, this approach is regarded as ineffective in redressing complex and systemic challenges, or stimulating development in resource constrained environments (Roundy et al., Citation2018). This contributes to the formation and implementation of ‘ineffective’ policies that lack coherent agenda and fail to meet the needs of the business base (Arshed et al., Citation2014, Citation2016; Niska & Vesala, Citation2013; Xheneti, Citation2017). Other researchers and practitioners call for ‘bottom-up’ approaches, advocating leadership from business owners and smaller ESOs (Feld, Citation2012; Motoyama & Knowlton, Citation2016). This places an unreasonable burden on entrepreneurs who do not have the resources and political influence of larger organizations (Pitelis, Citation2012). While this work debates the effectiveness of the governance structure, the micro-level dynamics, interactions and activities that create EEs have received less attention (Cunningham et al., Citation2019; Han et al., Citation2021).

The minutiae of the interactions and activities of individuals and organizations within EEs represents an important research gap to explore because variations in the structures and components of EEs can lead to performance variance (Colombelli et al., Citation2019; Szerb et al., Citation2019). Our study aims to understand the dynamics of EE organizing activities at multiple levels of governance (Brown & Mason, Citation2017; Han et al., Citation2021). Thus, we ask: How is an entrepreneurial ecosystem coordinated across multiple levels of governance through multiple stakeholders?

We draw on network governance to answer this question (Davies, Citation2012; Laffin et al., Citation2014; Provan & Kenis, Citation2008). Network governance has been discussed widely in terms of its definition but there is no consistent classification as such (Jones et al., Citation1997; Powell, Citation1990). In this context we subscribe to Jones et al. (Citation1997, p. 914) network governance which ‘involves a select, persistent, and structured set of autonomous firms (as well as non-profit agencies) engaged in creating products or services based on implicit and open-ended contracts to adapt to environmental contingencies and to coordinate and safeguard exchanges’. Furthermore, the idea of ‘governance’ in this study captures the process and approach to coordination amongst organizations (Jones et al., Citation1997). Specifically, we conceptualize the EE as a complex network of formal public and private sector institutions (government bodies and ESOs) and informal organizations (entrepreneur networks, role models and advisors) which create and maintain governing structures located within a geopolitical boundary (Mason & Brown, Citation2014; Spigel, Citation2017). We adopt a network perspective to understand how ecosystem stakeholders collaboratively organize their activities to deliver support to entrepreneurs (Ayres & Stafford, Citation2014; Huggins et al., Citation2018).

We base our findings on an in-depth case study of the coordinating activities of the Tay Cities Region (TCR) in Scotland. Against the backdrop of a UK government City Region Deal, the UK and Scottish governments, local councils and non-governmental organizations committed to investing in the economic development of the region. We highlight that those involved in constructing the EE network to deliver enterprise support are involved in three types of relational work that organizes governance activity: work that forms, work that structures and work that interrupts the EE network. This allows us to detail the external and internal governance of national, local, and private organizations that create ecosystem structure and coordinate activity across the region. This study contributes to existing work on EE governance and coordination (Colombelli et al., Citation2019; Cunningham et al., Citation2019; Motoyama & Knowlton, Citation2016), and enterprise policy literature (Arshed et al., Citation2014, Citation2016; Autio & Levie, Citation2017).

LITERATURE REVIEW

Entrepreneurial ecosystem coordination and governance

An EE is an interconnected set of entrepreneurs, organizations, institutions and processes (Mason & Brown, Citation2014). These components are the combination of socially based networks, material attributes and the entrepreneurial culture of a region (Spigel, Citation2017). Within an EE there are multiple stakeholders operating at different levels, such as universities, local governments and national economic development agencies (Spigel, Citation2016). Taken together with entrepreneurs and ESOs, these layers create multiple governing forces, which has created debate about how to effectively manage their complexity (Han et al., Citation2021; Roundy et al., Citation2018).

There are typically three schools of thought on how an EE is governed. First, the ‘top-down’ approach where government at either a national (e.g., Bergek et al., Citation2008) or a local level (e.g., Motoyama & Knowlton, Citation2016) leads the ecosystem by directing resources and policy to plug gaps and address market failures. Second, the ‘bottom-up’ approach sees entrepreneurs organize into the networks, groups and programmes needed to support themselves (Feld, Citation2012). Finally, the collective impact approach sees stakeholders engage with policymakers (Autio & Levie, Citation2017), providing the knowledge from the ‘bottom-up’ to inform decisions in managing the ecosystem (Stringer et al., Citation2006).

The top-down approach is often taken in enterprise policymaking involving government formulating policy with little input from stakeholders (Arshed et al., Citation2016). Governments play a key role in advocating entrepreneurship by promoting new ventures through legislation and policy (Isenberg, Citation2010). They can remove ‘red tape’ regulations that act as barriers to venture creation and place emphasis on economic development through supporting entrepreneurship (McMullen et al., Citation2008). The principal methods to develop entrepreneurs are through training, providing finance or supplying other resources (Lundstrom & Stevenson, Citation2005). They can also coordinate stakeholders and resources within a region (Motoyama & Knowlton, Citation2017), and invest in small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) development through procurement (Orser et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, governments address perceived market failures and provide economic incentives to encourage specific activities and plug gaps in resource availability (Autio & Levie, Citation2017).

The top-down method of enterprise policymaking has come under scrutiny (Arshed et al., Citation2014, Citation2016; Van Cauwenberge et al., Citation2013; Xheneti, Citation2017; Xheneti & Kitching, Citation2011). It does not fully capture the complexity of EEs where the entrepreneur is at the centre of the system dynamic (Autio & Levie, Citation2017; Stam, Citation2015). Opponents of top-down policymaking favour bottom-up approaches led by entrepreneurs and the stakeholders who are delivering support (Atherton et al., Citation2010; Feld, Citation2012; Woods & Miles, Citation2014). These entrepreneurs and stakeholders create support organizations, providing mentoring and networking to help establish a culture that supports entrepreneurship (Feld, Citation2012; Feldman & Zoller, Citation2012; Pitelis, Citation2012).

There are two main limitations of the bottom-up approach. First, the issue of appropriability acts as a barrier to coordinating activity. Pitelis (Citation2012) highlights that cultivating an EE requires an unreasonable amount of time, effort and resources on the part of entrepreneurs. Second, governments and larger organizations play an important role in regional development, even in ecosystems regarded as being entrepreneur-led transformations, such as Silicon Valley (Adams, Citation2021; Lécuyer, Citation2006). As such, some scholars have called for attention to collaborative and multilevel governance approaches (Arshed et al., Citation2016; Autio & Levie, Citation2017; Woods & Miles, Citation2014).

The stakeholders involved in collective impact approaches can build networks and give structure to an EE (Roundy, Citation2017). These stakeholders can help shape common commitment and coordinate activity between networks of EE stakeholders (Piattoni, Citation2010). However, these networks have not been sufficiently explored (Motoyama & Knowlton, Citation2016). The governance of EE networks is thought to lack robust theoretical and empirical foundations (Neumeyer et al., Citation2019). While much work has focused on the structure of EE networks (Colombo et al., Citation2019; Neumeyer et al., Citation2019), less attention has been given to the organizing practices that shape EE dynamics (Alvedalen & Boschma, Citation2017; Sohns & Wójcik, Citation2020).

Theoretical background: network governance

This study draws on network governance as a lens through which to explore the organizing activities of EE stakeholders. Network governance is a mechanism to coordinate interactions between public and private actors across multiple levels of a social organization (Davies, Citation2012; Gustavsson et al., Citation2009; Provan & Kenis, Citation2008). It focuses on the ‘nature of relationships, linkages and networks that exist between regional actors’ (Huggins et al., Citation2018, p. 1295). This is a distinct form of governance characterized by having unique structural characteristics, modes of conflict resolution and basis of legitimacy (Jones et al., Citation1997). Efficient practices are adaptive and allow self-organizing groups of policymakers to create learning loops and visualize direction towards improvement (Provan & Kenis, Citation2008). There are regular meetings between informal network actors. Rules for ‘collective’ operation are not prescribed and membership is open. The network deals with specific problems and has a propensity to experiment on approach (Provan & Kenis, Citation2008).

Proponents argue that this method of governance eclipses hierarchical modes of coordination because it allows considerable freedom to coordinate and self-organize, diminishes central government involvement, and includes service delivery from private and third sectors (Laffin et al., Citation2014). However, the assumption that removing bureaucratic structures gives rise to self-organizing networks has been questioned, because a lack of policy and institutional frameworks can reduce guidance and direction (Laffin et al., Citation2014; Rhodes, Citation2007). Provan and Kenis (Citation2008) highlight three modes of network governance that structure the relationships between organizations in different ways: participant governed, lead governed and network administrated.

The first mode, participant governed, highlights how network members organize themselves with no unique coordinating entity. This suggests that purely informal networks develop in a bottom-up process as a shadow network that has no official link to formal policy and management (Pahl-Wostl, Citation2009). The second mode, lead governed, highlights how central large powerful actors coordinate the network. This mode of governance is common in buyer–supplier relationships where there is a single powerful player and several weaker players (Provan & Kenis, Citation2008). The third mode, network administrated, shows a managerial entity setup to coordinate the ecosystem. This administrative organization plays a role in sustaining the network as a ‘broker’, mandated by network members (Provan & Kenis, Citation2008).

Within the extant EE literature, all these governance structures have been highlighted: bottom-up complex adaptive systems in Zhongguancun, China (Han et al., Citation2021); hierarchical systems in Turin, Italy (Colombelli et al., Citation2019); and administrative body organized systems in Scotland, UK (Autio & Levie, Citation2017). These studies show the different governance structures and their development, with network governance viewed as a promising means to implement enterprise and innovation policies (Huggins et al., Citation2018). However, there is still much to learn in terms of the on-going organizing behaviours of the actors within EEs that coordinate these networks.

The different organizing components that shape networks include relationship-building, information flows, regulations, shared goals and cultural norms (Cabanelas et al., Citation2017; Robins et al., Citation2011; Semlinger, Citation2008). These components shape the interactions between actors which create institutional frameworks and patterns of rule (Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2012). However, governance networks are not institutions based on fixed rules, norms and procedures, but relative frameworks in which interaction is negotiated, opportunities for joint decisions created and actions coordinated (Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2007). Therefore, interaction frameworks are informal, dynamic and shaped by network actors who impose their own rules during interaction (Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2007). In this sense, EE networks are not disembodied macrolevel constructs that shape organizations (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983), but shared practices which are created and maintained by individuals’ purposive action (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006).

Networks comprise a range of interactions among participants who are guided by authority, trust and legitimacy (Provan & Kenis, Citation2008). Coordinating EE activities, therefore, requires activities that facilitate interactions between network actors. This ‘relational work’ concerns ‘efforts aimed at building linkages, trust, and collaboration between people involved’ (Cloutier et al., Citation2016, p. 266). In network governance theory, interdependencies and interactions between organizations are crucial for effective coordination (Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2012). Maintaining relationships within networks is therefore a key part of managing and coordinating activities. The various relational practices undertaken to maintain networks in EEs, however, remain unclear (Colombelli et al., Citation2019; Sohns & Wójcik, Citation2020). Unpacking how EE stakeholders in EE networks coordinate their activities can address some of the shortcoming in the current literature (Alvedalen & Boschma, Citation2017) by detailing the dynamics which shape EE outcomes (Ter Wal et al., Citation2016; Wurth et al., Citation2021).

METHODS

To address our research question, we adopted an interpretative methodology designed to capture the organizational activities of stakeholders. Consistent with previous studies of enterprise policy (Arshed et al., Citation2019), our study is built upon a single in-depth case detailing the inner workings of a particular region in Scotland: Tay Cities. The qualitative case study design facilitated the capture of data at the micro-foundational level which allowed us to directly observe system-level activity and elucidate links between stakeholder activities and macro-level EE practices (Arshed et al., Citation2019; Dacin et al., Citation2010). Our research design was inductive, and the purpose was to build a conceptual explanation of the governance of the TCR EE based on the experiences of the multiple stakeholders operating in the region (Gioia et al., Citation2013).

Research setting

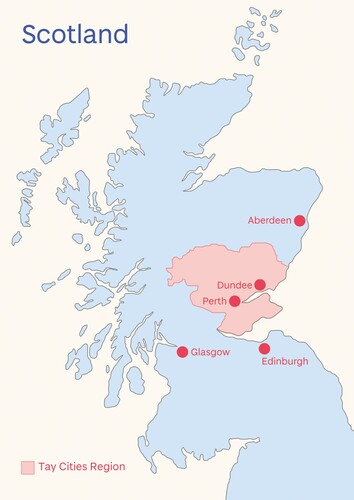

The focus of our study is the TCR, located in Central/North East Scotland (). This region includes four local authority areas: Angus, Dundee, Fife and Perth & Kinross. Almost 500,000 people live in the TCR, an estimated 10% of Scotland’s population, with approximately 15,500 businesses in the region. We selected the TCR as an appropriate research setting because it provides novel insight into governance arrangement. Scotland’s fourth biggest city, Dundee, is located in TCR. It is a post-industrial city with the third highest unemployment rate in Scotland. The transformation of the city to a ‘centre for innovation and ideas’ has not been as effective as other regions in the UK (Martin et al., Citation2016, p. 269). As such, Dundee has been the recipient of multiple transformation attempts (Peel & Lloyd, Citation2008). With regard to leadership and governance, The Dundee Partnership, established in 1981 and comprising several public, private and voluntary sector bodies, has delivered a number of economic development projects. This has put in place a framework for integrated and collaborative approaches, maintaining a shared vision and commitment to regional economic activity (McCarthy, Citation2007; Peel & Lloyd, Citation2007).

More recently in Scotland policy discussions have advocated for a more concentrated regional approach to economic development (Scottish Government, Citation2017). This stems from a 2011 UK government policy introducing City Region Deals to encourage local economic growth and decentralized decision-making (Scottish Parliament Information Centre, Citation2017). These are agreements between the UK government, the Scottish government and local authorities directing enterprise policies to support the development of a specific region. The TCR received a deal worth £763 million over 10 years from the Scottish and UK governments and their agencies, private partners, local authority governments, universities, colleges and the voluntary sector. As part of this deal, enterprise hubs, innovation parks, incubator and accelerator programmes are being developed across the region (Tay Cities, Citation2019). The commitment of these various stakeholders to developing EE infrastructure gave the study a platform to explore multilevel governance.

Data collection

The study, conducted between 2018 and 2019, took a qualitative approach to gain insights into four levels of governance: national government, local government, ESOs and entrepreneurs. These different stakeholder groups were selected because they represent, based on the literature review, the various levels that exist in EEs. The selection of participants was based on gaining a conceptual understanding of how the TCR governed its enterprise support activities, rather than on representativeness (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). To do this, we deployed two complementary sampling strategies: purposive and snowball. Purposive sampling facilitated the identification of appropriate participants for the study, while snowball sampling allowed participants to identify others they knew to be information rich (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation1984). This approach allowed us to target stakeholders with different perspectives to understand a ‘complete’ picture of the TCR EE.

Data were collected from a wide range of primary and secondary data sources to capture the perspectives of multiple stakeholders. This included policy document analysis, semi-structured interviews and observational notes. These data allowed us to collect information across the multiple stakeholder groups, facilitating triangulation and strengthening the validity of our research (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). shows an overview of the various stakeholders and the details of the data sources used to capture the different perspectives.

Table 1. Stakeholder groups and data sources.

Semi-structured interviews

We conducted a total of 31 semi-structured interviews with groups of informants from national government bodies (four interviews), local government (five interviews), ESOs (10 interviews) and entrepreneurs (12 interviews). The interviews lasted between 45 and 90 min and followed a broad thematic protocol aimed at understanding the individual’s and organization’s experiences of business support. They also captured their relationships with other stakeholders and their perceptions, motives and rationales underpinning their participation in the overall governance of the TCR EE. A modified interview structure was used for entrepreneurs, where they were asked about their perception of business support, relationships between various stakeholders and the organization of the TCR EE.

Participant observation

During data collection, the lead author was working in the Scottish government’s Economic Directorate during the time the TCR Growth Deal was announced. The researcher was privy to numerous policy meetings, informal interactions with policymakers and key stakeholders. Actors within the host organizations were aware of the research project and agreed to take part in the study, conditional on certain sensitivities. The lead author was able to make field notes on non-sensitive interactions including observations of formal discussions and attendance at 24 meetings over a six-month period. Two EE coordination events were also attended, where notes were taken on interactions between entrepreneurs, ESOs and policymakers. Participation in these meetings and interaction with these subjects, ultimately shaped informants’ behaviour (Johnstone, Citation2007). However, instead of contaminating what was observed these unavoidable effects were used to heighten sensitivity to the social processes and interactions under observation (Emerson et al., Citation2011). Effectively, by becoming a part of TCRs network governance efforts, albeit in a minor way, the researcher was able to witness closely the interactions and activities that stakeholders adopted. The observation notes that were taken supplemented and clarified specific points and reflections with those interviewed.

Archival data

A range of documentary evidence, including policy reports, ministerial briefings, economic strategies, media documents and Scottish parliamentary archives, were also assembled. The analysis of this material focused on understanding policy approaches, rationale and impact. This allowed for data triangulation, particularly with respect to investigating the links between individual-level observations and any responses actioned at the wider EE level (Arshed et al., Citation2019).

Data analysis

Our analysis used multiple data sources and followed inductive, qualitative approaches designed for the development of theoretical concepts (Gioia et al., Citation2013; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998). In line with recent research exploring the institutional context in which enterprise policymaking is implemented (e.g., Arshed et al., Citation2019), our data analysis started with the archival data and notes from the participant observations. We used policy documents, parliamentary hearings, reports and strategic documents to form a baseline understanding of the different stakeholders involved in the coordination of the TCR EE.

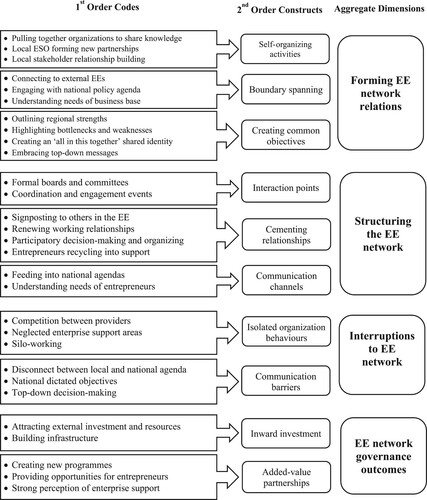

From our primary source of data collection, the semi-structured interviews, we were then able to unpack the roles of each entrepreneur, ESO, local council and national economic development agency. This inductive phase of analysis was detailed and involved line-by-line coding of our interview transcripts. We categorized and labelled any direct statements regarding stakeholder relationships, organizing behaviours and coordinating activities (first-order coding). This initial round of ‘open-coding’ allowed ideas about the coordination and governance of the EE to emerge.

We then synthesized our first-order codes into theoretical categories (second-order coding). This was done in an iterative and comparative manner that involved going through multiple stakeholder perspectives (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998) which served as the basis for our theorizing on the internal governance of the TCR EE. provides a representative data structure of the links between first-order coding and the theoretical categories underpinning our contributions. Representative data extracts for each theoretical category are presented in Table A1 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online.

RESULTS

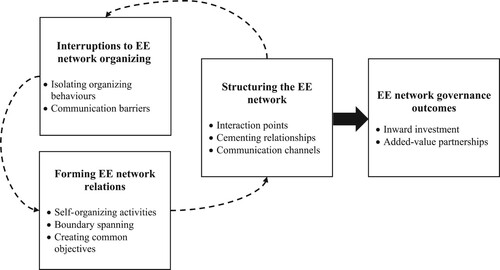

The following presentation of the findings explores the organizing activities of EE stakeholders within the TCR. Our data led us to identify three types of relational work that EE actors performed. These included: ‘forming EE network relations’, ‘structuring the EE network’ and ‘interrupting EE network organising’. An overview of our finding is presented in . This model proposes that these three types of relational work interlink, resulting in two main outputs from network coordinating efforts: attracting inward investment and sponsorship into the region, and the creation of added-value partnerships.

Figure 3. Summary of findings for multiple entrepreneurial ecosystem (EE) stakeholder network governance.

Forming EE network relations

To form EE network relations, our informants highlighted three critical activities. First, stakeholders self-organized into groups and partnerships to create new initiatives and working relationships. Second, national agendas and policy was embraced to create connections with larger, national, and powerful organizations. Finally, stakeholders worked together to create common agenda for coordination efforts.

A key part to the organization of the TCR EE network was forming new relationships to deliver and coordinate support. The stakeholders shared knowledge about the challenges that entrepreneurs had and created services to support them. These self-organizing activities often included multiple stakeholders joining together to create new working relationships:

I met a number of different organisations, and [ESO7] is a local organisation within Perth and Kinross that have a presence within rural Perthshire. And so, I think just as an initial conversation really, to try to establish where gaps existed in service provision and therefore where the solutions could be provided in order to address the gaps, we put our heads together along with [ESO1] and a fourth organisation that specifically support the third sector and we established a partnership.

We called it Business Enterprise Month and so using that we tried to pull everyone together, social enterprise, public sector, private sector. And almost if it come off this very, very busy environment where there’s a lot of support out there … .

We also saw that it was important that you have the public sector and the private sector businesses that left to themselves, they weren’t really connecting adequately with each other. It was important that there was an organisation that was available to sort of bring those strands together.

There was a sense that embracing these messages also helped to create a collective identity for delivering enterprise support in the region. This notion that working together would improve the regional development of TCR was shared by most stakeholders in the network:

There’s that genuine sense of everybody having to work together. But there’s also a genuine sense of as the tide rises for one, it rises for everyone, and I think people get that if something’s spinning then that will basically help other things.

Structuring the EE network

To structure the EE network stakeholders worked to formalize procedures, activities and means of communication. Our informants highlighted three critical activities. First, stakeholders created formal interaction points, such as formal committees and regular events. Second, stakeholders cemented relationships with the region which encouraged collaboration and strengthened bonds. Finally, stakeholders worked to uphold both top-down and bottom-up communication channels that they had established.

While work to form network relations was largely informal and sporadic, structural work transitioned these informal self-organizing into something slightly more formal. The national public sector agencies that operated in the TCR established such practices from the top-down by creating committee and organizational structures to coordinate regional activities amongst national bodies, local government, and ESOs:

[NG1] needs to be involved and [NG3] and other key partners, councils have to be involved at every stage of that. So, at the top level, you’ve got your joint committee and we’ve got a governance chart … it sets out really, really clearly and it shows that we’ve got the joint committee at the top, beneath that you have a private sector business group that we are the secretariat for.

It starts at a very high level of the board and then it filters right down to specific local community groups. So, it’s a whole host of partners who are part of that structure and that covers some of what we do when it comes to partnership working.

When you look at the amount of manpower that is put into putting Business and Enterprise Month together, the number of hours it takes. … We had two or three [meetings] since the last month. We had a mop-up session, we then get together to put together who’s going to chair it, etc. this year. But yes, given that, after the summer break, you’re probably looking at us all getting together for two hours, and that’s like 12 individuals around the table from the six, seven partners.

I’ve never really gone out there looking at what the government says is needed. I’ve gone out there looking at what stares at me in the face and I see the communities and what they tell me they need.

The focus is really on maintaining constructive dialogue and partnership working so that our offer is complementary to their offers and where there are opportunities to do things jointly, we’re able to do that.

I’ve had quite a few referrals from [ESO3], lots of referrals from even [ESO8]. I’ve had a lot of referrals from [ESO10] and [ESO6], not to mention I get a heck of a lot of referrals coming from the business community because they now know we exist.

Interrupting EE network organizing

Numerous informants highlighted behaviours that acted to interrupt the way the network was organized, which included two critical activities. First, some stakeholders chose to operate in isolation, without collaboration and often in competition with others. Second, examples were given when communication channels would break down, making collaboration more difficult.

Numerous stakeholders spoke about isolated organizing behaviours that threatened the way network relations were governed. Some ESOs were ‘competitive’ and operated in ‘silos,’ whilst some of the larger EE players would create restrictive criteria for supporting entrepreneurs, causing tension:

There’s still a lot of silo-ization within the ecosystem. You’ve still got people that, kind of, focus on a demographic and forget that there’s other groups all around that demographic who’ve got a role to play. I think we’ve got to break down that. … Sometimes it’s a sense of elitism, because some organisations only want to deal with the big companies, or the high-growth companies.

I think really just the being aware of things is definitely a factor because there does seem to be quite a lot of pockets of support, but it’s just knowing which one of them are applicable to you and useful to you, and people just finding out about them is sometimes a challenge.

lots of information out there on going about setting up your own business and sometimes it’s conflicting or you’re told that there’s funding available for setting up and start up grants … it’s really hard detracting these kinds of information.

I’ll be under some contractual restrictions like a minimum number of attendees at workshops and that makes it difficult to run rural workshops consistently. … So really the aspect I was looking for through this relationship was partners working together in order to be able to bolster numbers for workshops.

Outcomes of effective EE network governance

The outcomes of effective EE network governance were two-fold: inward investment was attracted to help stimulate regional development and stakeholder collaborated to create value-added support programmes for entrepreneurs. In the TCR, there were numerous development projects, such as the V&A, a design museum and centre for creative businesses, or Medipark, an innovation centre for biotech businesses. The local government recognized the importance of having a collaborative environment in attracting this investment into the region:

I think the V&A in Dundee for example is an area where we have shown that joined up working can deliver a heck of a lot more in terms of impact than an individual organisation doing its own thing.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The aim of this paper was to address the under researched area of EE governance by asking: How is an entrepreneurial ecosystem coordinated across multiple levels of governance, through multiple stakeholders? By drawing on the network governance approach in understanding the interconnected set of entrepreneurs, organizations, institutions, and processes that make up the TCR EE (Mason & Brown, Citation2014) our findings highlight various organizing activities undertaken by stakeholders within an EE network. Hence, the governance of EEs is an iterative process that is shaped by the stakeholders operating in a network. The efficacy of the EE network relied on the effective management of relationships, communication ties with local and national agendas and a shared collaborative culture for delivering enterprise support.

Our study highlighted how EE stakeholders construct the EE network to deliver enterprise support. Three types of organizing activity are identified: forming EE network relations, structuring the EE network, and interrupting EE network organizing. The outcomes of the effective coordination of the EE network were inward investment to the region and collaboratively delivered support programmes that added value to entrepreneurs. These findings make several contributions to the existing EE and enterprise policy literature.

First, we extend work on network structure of EEs (e.g., Colombelli et al., Citation2019; Motoyama & Knowlton, Citation2016; Neumeyer et al., Citation2019; Spigel & Harrison, Citation2018) by detailing how the relationships and organizing behaviours effect the on-going development of the EE network. Wider contributions have been made to enterprise policy research that calls for entrepreneurial approaches to policymaking (Brown et al., Citation2017; Huggins et al., Citation2018; Isenberg, Citation2010) by showing the effectiveness of network governance approaches. This extends current insights into collaborative policy development processes (Autio & Levie, Citation2017), offering potential solutions to the ineffectiveness of enterprise policymaking and implementation (Arshed et al., Citation2014, Citation2016; Niska & Vesala, Citation2013; Van Cauwenberge et al., Citation2013). In order for complex EEs to run at optimal levels, alignment of all stakeholders is required (Han et al., Citation2021; Roundy et al., Citation2018). The network governance approach that cuts across multiple levels is one such example of how complex systems can be coordinated.

Second, by capturing the multi-foundational elements of an EE we were able to advance debate regarding the structure of EEs (Colombelli et al., Citation2019; Colombo et al., Citation2019; Cunningham et al., Citation2019). Current insights into network governance indicates how various structures govern the action of stakeholders within a network (Provan & Kenis, Citation2008). We focused on the behaviours of the stakeholders which offers insights into the practices and processes they undertake to manage the network. Thus, indicating how various EEs are structured in an on-going dynamic.

Finally, we contribute to the debate on the outputs of effective regional EEs, which to date is explicitly linked to economic performance (Audretsch & Belitski, Citation2021; Brown & Mawson, Citation2019; Content et al., Citation2020; Szerb et al., Citation2019). Our analysis offers insight from a governance perspective – the outcomes of effective ecosystem coordination is its ability to attract investment, resources and coordinating activities to create value-added enterprise support interventions. This contributes to literature that looks to understand the complexity of causal chains that exist within an EE (Autio & Levie, Citation2017; Stam, Citation2015). By focusing on the relationships between EE stakeholders, we were able to understand the outcomes of effective coordination activities. We argue that these are valuable output indicators of an effective ecosystem policy in addition to new venture creation and growth measures, which may take longer than a typical policy cycle to realize.

This study is not without its limitations. First, generalizing should be done with caution as our study undertook a single case of TCR. In Scotland there are 11 Growth Regions, each with different economic activities, geography, and institutional setups, which could utilize different variations on the coordinating activities that are highlighted in this study. The different relational and structural embeddedness of a region may demand alternative governing activities to assist with development. Future research should build upon existing studies that look at EE dynamics to better understand the role of policy in driving the growth of effective EEs. Furthermore, studying different contexts and environments in understanding relational and structural embeddedness of a region would be beneficial in comparing the dynamics of individuals within EEs with respect to enterprise policy.

Second, the research looks at single actors within organizations within the network. Future studies have the potential to move beyond single organization, single sector and single level studies and consider multi-actors within the same organizations across EEs. This allows for different narratives from the same organizations to understand how they shape events around an overarching set of enterprise policy aims. This can shed further light on potential tensions within EE coordination and on enterprise policy processes (Arshed et al., Citation2014; Arshed et al., Citation2021; Xheneti, Citation2017).

Third, the limited insights from policymakers hindered our deep understanding into the role of government in the EE. Exploring the role of government and policymakers within EEs will allow for relationships between government and central agencies, as well as the relationships between central and local government to be studied. This is important to explore because collaboration can be encouraged by central government funding and by governments facilitating, influencing, and informing effective enterprise policy (Moseley & James, Citation2008). This will allow policymakers within government (national, regional and local) to move beyond the narrow scope of formal institutions and consider the different types of entrepreneurship which can be supported in a region (Audretsch & Belitski, Citation2021).

A final limitation of the study is that it only explores network governance within the EE once it has been established. There is a lack of knowledge as to the prior conditions and, specifically, their influence in the decision to form networks and the impact of this element on the networks’ development and structure of governance (das Mercês Milagres et al., Citation2019). This opens an avenue of research where prior conditions could be explored to understand the dynamics and the nature of governance within regional EEs (Colombelli et al., Citation2019).

To conclude, this study extends the literature on regional EE governance which predominately focuses on network structures that govern enterprise policy (Colombelli et al., Citation2019; Cunningham et al., Citation2019; Neumeyer et al., Citation2019). We highlight the organizing activities of stakeholders which gives rise to the coordination of an EE network through their relational work: forming, structuring, and interrupting. Hence, our study illustrates how effective network governance approaches can be developed to manage both top-down and bottom-up EE demands and deliver effective enterprise support in a region.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (135.3 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Adams, S. B. (2021). From orchards to chips: Silicon Valley's evolving entrepreneurial ecosystem. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 33(1–2), 15–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2020.1734259

- Alvedalen, J., & Boschma, R. (2017). A critical review of entrepreneurial ecosystems research: Towards a future research agenda. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 887–903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1299694

- Arshed, N. (2017). The origins of policy ideas: The importance of think tanks in the enterprise policy process in the UK. Journal of Business Research, 71, 74–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.10.015

- Arshed, N., Carter, S., & Mason, C. (2014). The ineffectiveness of entrepreneurship policy: Is policy formulation to blame? Small Business Economics, 43(3), 639–659. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9554-8

- Arshed, N., Chalmers, D., & Matthews, R. (2019). Institutionalizing women’s enterprise policy: A legitimacy-based perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(3), 553–581. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718803341

- Arshed, N., Knox, S., Chalmers, D., & Matthews, R. (2021). The hidden price of free advice: Negotiating the paradoxes of public sector business advising. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 39(3), 289–311. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242620949989

- Arshed, N., Mason, C., & Carter, S. (2016). Exploring the disconnect in policy implementation: A case of enterprise policy in England. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 34(8), 1582–1611. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X16628181

- Atherton, A., Kimo, J. P., & Kim, H. (2010). Who’s driving take-up? An examination of patterns of small business engagement with business link. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 28(2), 257–275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/c09152

- Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2021). Towards an entrepreneurial ecosystem typology for regional economic development: The role of creative class and entrepreneurship. Regional Studies, 55(4), 735–756. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1854711

- Autio, E., & Levie, J. (2017). Management of entrepreneurial ecosystems. In G. Ahmetoglu, T. Chamorro-Premuzic, B. Klinger, & T. Karcisky (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of entrepreneurship (pp. 423–449). Wiley.

- Ayres, S., & Stafford, I. (2014). Managing complexity and uncertainty in regional governance networks: A critical analysis of state rescaling in England. Regional Studies, 48(1), 219–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.672727

- Bergek, A., Jacobsson, S., Carlsson, B., Lindmark, S., & Rickne, A. (2008). Analyzing the functional dynamics of technological innovation systems: A scheme of analysis. Research Policy, 37(3), 407–429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.12.003

- Brown, R., & Mason, C. (2017). Looking inside the spiky bits: A critical review and conceptualisation of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9865-7

- Brown, R., & Mawson, S. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and public policy in action: A critique of the latest industrial policy blockbuster. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 12(3), 347–368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsz011

- Brown, R., Mawson, S., & Mason, C. (2017). Myth-busting and entrepreneurship policy: The case of high growth firms. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29(5–6), 414–443. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1291762

- Cabanelas, P., Cabanelas-Omil, J., Lampón, J. F., & Somorrostro, P. (2017). The governance of regional research networks: Lessons from Spain. Regional Studies, 51(7), 1008–1019. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1150589

- Cloutier, C., Denis, J.-L., Langley, A., & Lamothe, L. (2016). Agency at the managerial interface: Public sector reform as institutional work. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 26(2), 259–276. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muv009

- Colombelli, A., Paolucci, E., & Ughetto, E. (2019). Hierarchical and relational governance and the life cycle of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 505–521. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9957-4

- Colombo, M. G., Dagnino, G. B., Lehmann, E. E., & Salmador, M. P. (2019). The governance of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 419–428. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9952-9

- Content, J., Bosma, N., Jordaan, J., & Sanders, M. (2020). Entrepreneurial ecosystems, entrepreneurial activity and economic growth: New evidence from European regions. Regional Studies, 54(8), 1007–1019. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1680827

- Cunningham, J. A., Menter, M., & Wirsching, K. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystem governance: A principal investigator-centered governance framework. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 545–562. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9959-2

- Dacin, M. T., Munir, K., & Tracey, P. (2010). Formal dining at Cambridge colleges: Linking ritual performance and institutional maintenance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1393–1418. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.57318388

- das Mercês Milagres, R., da Silva, S. A. G., & Rezende, O. (2019). Collaborative governance: The coordination of governance networks. Revista de Administração FACES Journal, 18(3), 103–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21714/1984-6975FACES2019V18N3ART6846

- Davies, J. S. (2012). Network governance theory: A Gramscian critique. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(11), 2687–2704. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/a4585

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1984). Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Sage.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. University of Chicago Press.

- Feld, B. (2012). Startup communities: Building and entrepreneurial ecosystem in your city. Wiley.

- Feldman, M., & Zoller, T. D. (2012). Dealmakers in place: Social capital connections in regional entrepreneurial economies. Regional Studies, 46(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.607808

- Gioia, D., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Gustavsson, E., Elander, I., & Lundmark, M. (2009). Multilevel governance, networking cities, and the geography of climate-change mitigation: Two Swedish examples. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 27(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/c07109j

- Han, J., Ruan, Y., Wang, Y., & Zhou, H. (2021). Toward a complex adaptive system: The case of the Zhongguancun entrepreneurship ecosystem. Journal of Business Research, 128, 537–550. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.077

- Huggins, R., Waite, D., & Munday, M. (2018). New directions in regional innovation policy: A network model for generating entrepreneurship and economic development. Regional Studies, 52(9), 1294–1304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1453131

- Isenberg, D. J. (2010). How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard Business Review, 88(6), 40–50.

- Johnstone, B. A. (2007). Ethnographic methods in entrepreneurship research. In H. Neergaarde & J. P. Ulhoi (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research methods in entrepreneurship (pp. 97–121). Edward Elgar.

- Jones, C., Hesterly, W. S., & Borgatti, S. P. (1997). A general theory of network governance: Exchange conditions and social mechanisms. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 911–945. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9711022109

- Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. (2012). Governance network theory: Past, present and future. Policy & Politics, 40(4), 587–606. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655431

- Laffin, M., Mawson, J., & Ormston, C. (2014). Public services in a ‘postdemocratic age’: An alternative framework to network governance. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 32(4), 762–776. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/c1261

- Lawrence, T. B., & Suddaby, R. (2006). 1.6 institutions and institutional work. In S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. B. Lawrence, & W. R. Nord (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organization studies (p. 215). Sage.

- Lécuyer, C. (2006). Making Silicon Valley: Innovation and the growth of high tech, 1930–1970. MIT Press.

- Lundstrom, A., & Stevenson, L. A. (2005). Entrepreneurship policy: Theory and practice. Springer.

- Martin, R., Sunley, P., Tyler, P., & Gardiner, B. (2016). Divergent cities in post-industrial Britain. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 9(2), 269–299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsw005

- Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2014). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth oriented entrepreneurship. Final Report to OECD, Paris, 30(1), 77–102.

- McCarthy, J. (2007). Partnership, collaborative planning and urban regeneration. Ashgate.

- McMullen, J. S., Bagby, D., & Palich, L. E. (2008). Economic freedom and the motivation to engage in entrepreneurial action. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(5), 875–895. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00260.x

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An extended sourcebook (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Moseley, A., & James, O. (2008). Central state steering of local collaboration: Assessing the impact of tools of meta-governance in homelessness services in England. Public Organization Review, 8(2), 117–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-008-0055-6

- Motoyama, Y., & Knowlton, K. (2016). From resource munificence to ecosystem integration: The case of government sponsorship in St. Louis. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 28(5–6), 448–470. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2016.1186749

- Motoyama, Y., & Knowlton, K. (2017). Examining the connections within the start-up ecosystem: A case study of St. Louis. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 7(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/erj-2016-0011

- Neumeyer, X., Santos, S. C., & Morris, M. H. (2019). Who is left out: Exploring social boundaries in entrepreneurial ecosystems. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(2), 462–484. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9694-0

- Niska, M., & Vesala, K. M. (2013). SME policy implementation as a relational challenge. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(5–6), 521–540. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2013.798354

- Orser, B., Riding, A., & Weeks, J. (2019). The efficacy of gender-based federal procurement policies in the United States. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 491–515. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9997-4

- Pahl-Wostl, C. (2009). A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Global Environmental Change, 19(3), 354–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.06.001

- Peel, D., & Lloyd, G. (2007). Community planning and land use planning in Scotland: A constructive interface? Public Policy and Administration, 22(3), 353–366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076707078765

- Peel, D., & Lloyd, G. (2008). New communicative challenges: Dundee, place branding and the reconstruction of a city image. Town Planning Review, 79(5), 507–532. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.79.5.4

- Piattoni, S. (2010). The theory of multi-level governance. Oxford University Press.

- Pitelis, C. (2012). Clusters, entrepreneurial ecosystem co-creation, and appropriability: A conceptual framework. Industrial and Corporate Change, 21(6), 1359–1388. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dts008

- Powell, W. W. (1990). Neither market nor hierarchy: Network forms of organisation. In B. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behaviour (pp. 295–336). JAI Press.

- Provan, K. G., & Kenis, P. (2008). Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(2), 229–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum015

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (2007). Understanding governance: Ten years on. Organization Studies, 28(8), 1243–1264. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607076586

- Robins, G., Bates, L., & Pattison, P. (2011). Network governance and environmental management: Conflict and cooperation. Public Administration, 89(4), 1293–1313. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01884.x

- Roundy, P. T. (2017). ‘Small town’ entrepreneurial ecosystems: Implications for developed and emerging economies. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 9(3), 238–262. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-09-2016-0040

- Roundy, P. T., Bradshaw, M., & Brockman, B. K. (2018). The emergence of entrepreneurial ecosystems: A complex adaptive systems approach. Journal of Business Research, 86, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.032

- Scottish Government. (2017). Enterprise and skills review report on phase 2: Regional partnerships. https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/progress-report/2017/06/enterprise-skills-review-report-phase-2-regional-partnerships/documents/00521431-pdf/00521431-pdf/govscot%3Adocument/00521431.pdf

- Scottish Parliament Information Centre. (2017). City region deals. http://www.parliament.scot/ResearchBriefingsAndFactsheets/S5/SB_17-19_City_Region_Deals.pdf

- Semlinger, K. (2008). Cooperation and competition in network governance: Regional networks in a globalised economy. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 20(6), 547–560. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620802462157

- Sohns, F., & Wójcik, D. (2020). The impact of Brexit on London’s entrepreneurial ecosystem: The case of the FinTech industry. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(8), 1539–1559. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20925820

- Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2007). Theoretical approaches to governance network dynamics. In E. Sørensen & J. Torfing (Eds.), Theories of democratic network governance (pp. 25–42). Springer.

- Spigel, B. (2016). Developing and governing entrepreneurial ecosystems: The structure of entrepreneurial support programs in Edinburgh, Scotland. International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development, 7(2), 141–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIRD.2016.077889

- Spigel, B. (2017). The relational organisation of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12167

- Spigel, B., & Harrison, R. (2018). Toward a process theory of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 151–168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1268

- Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1061484

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Stringer, L. C., Dougill, A. J., Fraser, E., Hubacek, K., Prell, C., & Reed, M. S. (2006). Unpacking ‘participation’ in the adaptive management of social–ecological systems: A critical review. Ecology and Society, 11(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01896-110239

- Szerb, L., Lafuente, E., Horváth, K., & Páger, B. (2019). The relevance of quantity and quality entrepreneurship for regional performance: The moderating role of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Regional Studies, 53(9), 1308–1320. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1510481

- Tay Cities. (2019). Tay Cities Region economic strategy 2019–2039. https://www.taycities.co.uk/sites/default/files/tay_cities_res_2019.pdf

- Ter Wal, A. L. J., Alexy, O., Block, J., & Sandner, P. G. (2016). The best of both worlds: The benefits of open-specialized and closed-diverse syndication networks for new ventures’ success. Administrative Science Quarterly, 61(3), 393–432. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839216637849

- Van Cauwenberge, P., Vander Bauwhede, H., & Schoonjans, B. (2013). An evaluation of public spending: The effectiveness of a government-supported networking program in Flanders. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 31(1), 24–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/c11329b

- Woods, M., & Miles, P. (2014). Collaborative development of enterprise policy: A process model for developing evidence-based policy recommendation using community focused strategic conversations and SERVQUAL. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 27(3), 174–189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-09-2012-0121

- Wurth, B., Stam, E., & Spigel, B. (2021). Toward an entrepreneurial ecosystem research program. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 1042258721998948. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258721998948

- Xheneti, M. (2017). Contexts of enterprise policy-making – an institutional perspective. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29(3–4), 317–339. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2016.1271021

- Xheneti, M., & Kitching, J. (2011). From discourse to implementation: Enterprise policy development in postcommunist Albania. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 29(6), 1018–1036. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/c10193b