ABSTRACT

How urban financialization is achieved across different government levels receives limited attention. This study addresses the gap by examining the deployment of China’s local government bonds (LGBs). LGBs introduce a distinct financialization process in which the government relies on debt-financing for urban development, but in a regulated way to constrain financial risks. Urban financialization is realized through the multi-scalar structure of the government. The centralized procedure strengthens central and provincial regulations on local development projects. The multi-scalar government not only facilitates urban financialization but also executes statecraft by designing the process.

INTRODUCTION

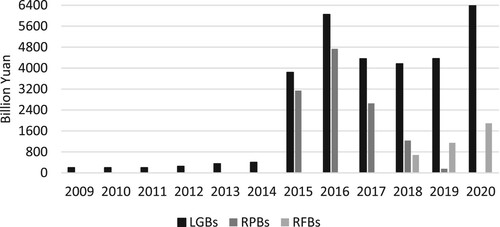

In 2009, the central government of China introduced local government bonds (LGBs), which are the Chinese version of municipal bonds. LGBs were at first described as an alternative for local governmentsFootnote1 to fund urban development projects. Different from local government financing platforms (LGFPs) established by local governments (Pan et al., Citation2017), LGBs require provinces, cities and counties to apply for an annual quota of the bonds from the Ministry of Finance (MOF) based on the specific financing requirements of projects. Only provinces plus five cities with special planning status can issue these bonds. Provinces examine applications from cities and counties, send them to MOF for further evaluation, issue LGBs on behalf of lower level governments and transfer money to them. LGBs experienced restricted growth before 2015 because MOF issued small-scale nationwide quotas of no more than 400 billion yuan each year. During the same period, local debts mainly generated from LGFPs surged (Feng et al., Citation2021) due to the 4 trillion yuan stimulus package (Naughton, Citation2009). According to the National Audit Office, the explicit/implicitFootnote2 debts of local governments at the end of 2014 were 15.4/8.6 trillion yuan. In this situation, the central government decided to rectify local financial practices by LGBs under its control from 2015. The bonds were set as the only legal way for local governments to have debts, while other financial methods have severe regulations imposed. As a result, LGBs have become the most important source for urban development finance. According to MOF, 99.32% of local debts were in the form of LGBs by the end of 2020.

LGB operation suggests a multi-scalar perspective that has not yet received enough attention in urban financialization (Klink & Stroher, Citation2017). Existing studies have discussed the role of the state in the financialization process especially since the 2010s (Wu, Citation2021). Though the concept of financialization emphasizes the increasing influence of financial actors at multiple scales (Aalbers, Citation2017a), the state is neither a passive recipient nor a simple facilitator of financial capital affecting urban development. It is an active participator or even leader (Bryson et al., Citation2017; Hofman & Aalbers, Citation2019; Yeşilbağ, Citation2020) which crafts the process (Belotti & Arbaci, Citation2021). The state usually changes regulatory settings to introduce financial actors into the built environment (Aalbers, Citation2009; Aalbers et al., Citation2017; Gotham, Citation2016) and then relies on diversified ‘financial engineering’ (Ashton et al., Citation2012) for the financing and operation of urban (re)development in a time of austerity (Peck, Citation2012). During the process, the state may use financial approaches to contribute to development goals such as social housing, economic integration, employment and the like (Anguelov et al., Citation2018; Klink & Stroher, Citation2017), but it may also change into a ‘speculator’ prioritizing financial return by regarding the built environment as a tradable asset (Beswick & Penny, Citation2018; Yeşilbağ, Citation2020).

Nonetheless, the understanding of the state is still limited. The literature of the early 2010s paid more attention to the local state under pressure of financial constraints and actively performing financializing governance (Bernt et al., Citation2017; Peck & Whiteside, Citation2016; Weber, Citation2010). Since then some scholars have called for a closer look at the central state (Christophers, Citation2017) which influences local state and financial institutions through policies or direct involvement (O’Brien & Pike, Citation2019). But the multi-scalar perspective remains under-researched with only a few exceptions. Töpfer (Citation2018, pp. 296–297) deems that ‘internal differences’ caused by ‘varying incentives and choices’ within a multilevel government should be considered in state actions towards financial markets. Zhang (Citation2020) discusses how federal, provincial and local states affect the financialization of affordable housing in Toronto and finds that though all levels of governments show financialized features the extent and manifestations are distinct. Belotti and Arbaci (Citation2021) examine how the financialization of social rented housing in Milan is led by the interplay of national, regional and local governments. The findings suggest that all levels help to craft the financialization process through law-making that creates ‘a marketised framework, financial infrastructure and financial–legislative conditions’ (Belotti & Arbaci, Citation2021, p. 429). These two papers provide a good start for exploring more about the multi-scalar government. But financialization is a spatial and fragmented phenomenon embedded in specific contexts (Aalbers, Citation2017b; French et al., Citation2011). A few case studies conducted in similar institutional backgrounds are not enough to understand the role of the multi-scalar state. Further work on different government practices in distinct contexts is needed.

By analysing LGB deployment in China, this paper seeks to create empirical contributions and theoretical implications to understand the role of the multi-scalar state in urban financialization. The findings suggest that though China’s government relies on ‘debt-machine strategies’ (Peck & Whiteside, Citation2016) through LGBs that use government credit and the future revenue of urban development projects to leverage investment as development finance, it does so in a regulated way based on a centralized level-by-level deployment procedure to constrain excessive risk. The central government dominates the procedure with the emphasis on financial safety and regulation. The provincial government acts as the conjuncture of central policy makers and municipal policy executors that ensures upper level policies are properly implemented by lower level governments. The municipal government has to prioritize LGBs though there are the regulations and restrictions. The characteristics of regulation and centralization are generated by the specific institutional context in China and suggest that the multi-scalar state executes statecraft by designing the urban financialization process. More broadly, the case of LGBs reflects the Chinese model of strong state intervention in promoting development, which enriches the understanding of urban financialization and developmental practice.

The study depends on data from published policy documents; disclosed reports about bond applications and approval, audits on the use of money and project information on the China Central Depository & Clearing Co., Ltd (CDCC) platform and government websites; issue-level secondary data about LGBs and other financial methods on the CELMA platform of MOF and the renowned third-party platform WIND; and news about the use of LGB capital from reliable media on the Internet. The data are from 2009 to January 2021. The rest of the study is as follows. The next section critically reviews the literature about the role of the state in urban financialization and introduces the unique features of China’s government. The following three sections respectively explain the roles of central, provincial and municipal governments in LGB development. The seventh section discusses the implications for the role of the multi-scalar government. The conclusion engaging empirical results with broader theoretical debates ends the study.

THE ROLE OF THE STATE IN URBAN FINANCIALIZATION

The concept of financialization has yet to come to a consensus, while the widely adopted one encompasses different dimensions (Aalbers, Citation2017a, p. 3): ‘the increasing dominance of financial actors, markets, practices, measurements, and narratives, at various scales, resulting in a structural transformation of economies, firms (including financial institutions), states, and households’. Based on similar perspectives, urban financialization pays attention to the influence of financial actors on the financing, management and ownership of the built environment (Guironnet & Halbert, Citation2014; Klink & Stroher, Citation2017). LGBs, which securitize the future revenue of urban development projects and use government credit to introduce investment as development finance, reflect the process of urban financialization. This research thus uses LGBs as the empirical focus to examine the role of the government in the process.

Regulatory change and the state

Generally, the main reason for the state enabling, participating in or crafting urban financialization is to raise money from the capital market to finance or operate urban (re)development projects. Because of the sluggish economy in the 1970s, the capitalist state reduced its expenditure on social services through public funds and turned to the financial market for promoting development (Bahle, Citation2003; Weber, Citation2010). Changing regulations is the main method to achieve such a target. The state issues regulations to introduce financial actors into the built environment. In 2005 the US federal and local states issued the Gulf Opportunity Zone Act with a series of ‘neoliberal socio-legal regulations and tax rule changes to allow the state and local governments to issue tax-exempt, private activity bonds – for example, debt securities – for the ‘public purpose’ of financing post-disaster rebuilding’ (Gotham, Citation2016, p. 1375). The mortgage market is shaped by mortgage lenders and the state and its agencies, in which mortgage loan securitization was largely invented by the state and state-backed institutions like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (Aalbers, Citation2009). The state also conducts (regulated) deregulation to remove regulations restricting financial actors. Housing associations in the Netherlands, which are quasi-public institutions, were previously financed by and under the tight control of the state and focused on building social housing (Aalbers et al., Citation2017). In the 1990s, the state cut its ties with these institutions because of national deficits and removed regulations hindering their access to financial capital. Since then, the institutions have acted more freely and used financial instruments to conduct more commercial real estate projects, land speculation and derivatives speculation.

After changing regulations, the state acts variously in different contexts. On the one hand, the state uses financial practices to achieve development goals. The Joint European Support for Sustainable Investment in City Areas, also known as JESSICA, is an initiative of the European Union (EU) to achieve sustainable and integrated development. Using development funds at the EU level to leverage private capital, JESSICA is adopted to finance urban regeneration projects in deprived areas. The initiative tries to use financial instruments that prioritize the rate of return to reach economic and social cohesion within the EU (Anguelov et al., Citation2018). The local state in Brazil sells ‘additional building rights’ within a built-up area allowing developers to build more than the stipulated floor area ratios. The pricing is based on the valorization of the area with future development. The money collected is used to provide infrastructure, low-income housing and parks. Moreover, during the pricing procedure, the state tries to expand the perimeter of the area and divide it into ‘core perimeter’ and ‘extended perimeter’. The core perimeter represents the prime real estate market in which the additional building rights are sold. The extended perimeter includes the outskirts which usually consist of slums. A total of 20% of the revenue from the sales is earmarked to build social housing and public transportation in the extended perimeter (Klink & Stroher, Citation2017).

On the other hand, the state prioritizes financial return but reduces social responsibilities. TOKİ (Mass Housing Administration) is a government agency in Turkey. TOKİ worked with public banks to provide loans at subsidised levels to constructors and homebuyers in the affordable housing sector in the 1980s. But after Turkey’s economic crisis in 2001, the agency became more exploitative. First, it took over control of land resources in the country from the former Land Office, commodified thousands of acres of land and then pledged or sold it on the open real estate market. A mortgage system and real estate investment trusts (REITs) were introduced to fund, operate and sell homes, promoting the securitization of the housing sector. Second, TOKİ undertakes affordable housing (re)development projects. It builds three types of new housing codified from A to C after the construction work. Types A and B are still categorized as affordable housing. But the C type, named as revenue sharing housing, is built as luxurious housing at popular locations for private rent or sale (Yeşilbağ, Citation2020). These exploitative behaviours of TOKİ create extra financial returns for the government but the housing sector become less social with the process of financialization.

The multi-scalar state

While most literature focuses on a particular level of the state, increasing attention has recently been paid to the interplay among government levels, though this is still limited. First, some studies explore the different behaviours of central and local states towards financial actors. Feng et al. (Citation2021) examine the different attitudes of central and local states in China towards the ‘urban development and investment corporations’, also known as Chengtou. A Chengtou is a company established by the local state to fund and operate urban development projects and manage public sectors. Chengtou mainly use the implicit guarantee of the local state to borrow bank loans and issue corporate bonds to raise development finance. Because of the ongoing urbanization process, Chengtou create a large amount of debt for the local state. To restrict local debts and associated financial risks, the central state issued regulations restricting Chengtou from borrowing money. However, the local state has been trying to circumvent these regulations. A typical example is that the central state requires Chengtou to have a liability ratio of less than 70% and cash flow that can cover its liabilities. Some local governments then merge some unqualified Chengtou to form a group company that meets the requirements (Feng et al., Citation2021, p. 6).

Second, a small number of studies apply the multi-scalar perspective to examine every level of the state, represented by Zhang (Citation2020) and Belotti and Arbaci (Citation2021). Zhang (Citation2020) emphasizes that the federal, provincial and municipal governments of Canada behave differently in using financial methods in affordable housing. The federal government actively adopts financial innovations to introduce investment from the market into housing construction. The government of Ontario distributes subsidies to encourage people with lower incomes to use mortgages or other financial methods to rent/buy their homes. The government of Toronto has to implement policies from the Ontario government, but it also applies tax relief and fee waivers for renters and buyers and uses surplus public land to build affordable housing. The methods of Toronto show little financial logic. In contrast, Belotti and Arbaci (Citation2021) suggest that national, regional and local governments in Italy work together to introduce institutional investors into the social rented housing sector. The national government retreated from providing housing with public funds in the 1980s and devolved the responsibility to the regional governments. The government of Lombardy reformed the legal system to commodify land and enable housing to be equally provided by the public and private sectors. The government of Milan worked closely with private investors, mainly multinational pension fund companies, through public–private partnerships to fund and manage housing. After experiments in Lombardy and Milan, the practice was introduced into other areas across the country.

The Chinese government in urban financialization

The government in China also adopts financial approaches to raise development finance, but the background contrasts with the austerity context of the capitalist economy. Since the 1980s, the central government has gradually devolved responsibility for development to local governments (Wong, Citation1991). Nonetheless, the central government has also been trying to take more of local fiscal income to maintain its own revenue. The tax reform of 1994 is widely noted (Wong, Citation2000). The central government set three kinds of tax, namely local tax, central tax and sharing tax. The local and central taxes belonged to local and central governments respectively. The central government took 75% of the sharing tax. By doing this, the central government collected a large proportion of local fiscal income. With the ongoing fast pace of economic development and urbanization, local governments had to find other channels with no need for sharing with the central government to replace traditional tax revenue as the source for development finance. Financial approaches have become the preferred choice. Land transfer is one of the two most important methods. The local government borrows land reserve loans to collect land and then sells its use right to investors and developers through competitive bidding. The pricing is based on future appreciation after development (Du et al., Citation2017; Tao et al., Citation2010). LGFPs are the other method. In a broad sense, LGFPs equal Chengtou mentioned above. The local government uses two main methods to raise funds through LGFPs. First, it injects public land into the company as collateral so that LGFPs can use the estimated value of the land after development to get bank loans and issue corporate (Chengtou) bonds (Wu, Citation2019). Second, it issues guarantees on behalf of LGFPs claiming that it would pay investors with fiscal income or other revenue if the company could not perform repayment (Pan et al., Citation2017; Ye et al., Citation2020). LGFPs became the most important source for development finance between 2009 and 2014. The central government published a 4 trillion yuan stimulus package in late 2008 to maintain development after the global financial crisis (Naughton, Citation2009). The local government had to raise 2.2 trillion yuan as development finance on its own. Compared with one-off land transfers, LGFPs could raise more money within a short period.

But the actual operation of LGFPs had problems. The same piece of land tended to be collateralized multiple times for different investors. The local government issued guarantees for nearly every deal of an LGFP, the sum of which was far more than its fiscal income for the foreseeable future. Moreover, most of the guarantees were implicit and only known to the local government and investors because they violated the regulations of the central government on constraining excessive local debt. These behaviours resulted in enormous local debts and added to risks for the local government, LGFPs and investors. The situation significantly changed when LGBs came to the front in 2015. In the next section, the role of the multi-scalar state in urban financialization will be examined in detail.

THE CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

The central government invented LGBs in 2009. The government issued the bonds to the capital market to raise development finance. LGBs are based on government credit and associated with specific urban development projects. The government provides no collateral for investors and repayment comes from fiscal income or project revenue. Until 2014, LGBs experienced slow growth because of central restrictions. Only provincial governments and five municipal governments with special planning status were permitted to issue LGBs. However, MOF ‘issues LGBs, repays for principal and interest and pays for issuing expenses on behalf of local governments’Footnote3 from 2009 to 2011. MOF set national annual quotas of no more than 400 billion yuan which were very small scale compared with the real demand for development finance. Hence, provinces picked the most appropriate projects from cities and counties to apply for their LGBs. Money raised from LGBs must go to the projects applied for instead of being used as general revenue. The projects should contribute to development goals set by the government for different sectors. From 2012 to 2014, pilot areas were set to issue and repay LGBs by themselves, while the total amount of all places still could not exceed the national quota.

Such operating mode made LGBs receive very little attention before 2015. But this period was an important experiment. Compared with land transfer and LGFPs, LGBs were brand new with heavy intervention from MOF. It was likely that there would be confusion, indifference and even resistance from local governments if MOF directly applied the bonds to local financial practice. Using limited amounts and pilot areas to let local governments gradually understand and then independently operate LGBs was a more reliable way of generating a smooth implementation.

Promoting LGBs as the main approach to financing urban development

Since 2015, the State Council has emphasized ‘opening front doors and closing back doors’ on development finance. The front doors refer to LGBs while the back doors mainly mean LGFPs. The revised Budget Law of 2014 states that ‘provinces permitted by the State Council can borrow money for urban development only through LGBs’, marking that all provincial governments could issue and repay LGBs on their own. For LGBs, there is still a national quota system, but the amounts significantly increased compared with the previous period. The annual quota for each locality is made by MOF by prioritizing ‘local debt risk, fiscal capacity and demand from supporting fund for major central-led projects’.Footnote4 There are specific calculations to produce a quota with a safe debt ratio. Issuance of LGBs cannot exceed the quota in any case. The project information mainly includes implementation and repayment plans, and financial evaluations and legal opinions provided by third-party firms. Provincial governments examine municipal applications first and then submit selected ones together with a few additional provincial applications to MOF. After the quota for the whole province is issued, provinces issue LGBs and transfer money to provincial projects and municipal governments.Footnote5

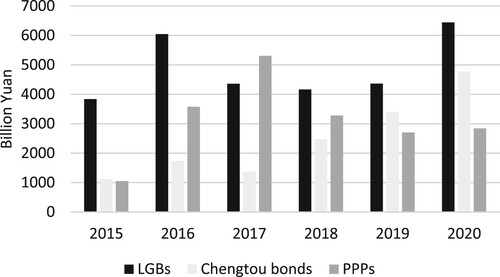

The other way of central government promoting LGBs is by coming up with new categories for urban development projects in various fields. In 2015, the bonds were divided into general bonds (GBs) for projects without a revenue stream and special bonds (SBs) for profitable ones. Governments promised to repay GBs with fiscal funds and SBs with project income or corresponding government-managed funds. In 2017, MOF published a rule for project-level revenue expenditure balancing, which required projects using SBs as a funding source to earn enough income to repay the bonds. According to the disclosed reports, income should be at least 1.2 times the SB amount. Further, MOF came up with three kinds of project-level SBs in 2017 and 2018, namely land reserve bonds (LRBs, in 2017), shanty town rebuilding bonds (STRBs, in 2018) and toll road bonds (TRBs, in 2018). Land is always crucial to local fiscal revenue, and LRBs provide stable capital streams for local governments to purchase land. In 2017, Premier Li Keqiang came up with a three-year plan to redevelop 15 million units of shanty towns between 2018 and 2020. STRBs are mainly used to support this plan. As for TRBs, MOF uses them as an example for local governments to foster new project-level SBs in the transport infrastructure field. These SBs played a leading role in raising development finance. LRBs and STRBs became the most issued SBs in the following two years () while TRBs have encouraged local governments to bring forward more SBs including transport bonds, high-speed railway bonds, urban–rural railway bonds and the like. Moreover, MOF comes up with key fields contributing to development every year in which it encourages LGB capital to invest. In this situation, local governments have designed over eighty different project-level SBs tailored to local contexts which cover the key fields first and then as many other fields as possible. Examples include SBs for public hospitals, environment protection, industrial parks, water governance, infrastructure construction, rural revitalization, etc.

Figure 1. Issuance of land reserve bonds (LRBs) and shanty town rebuilding bonds (STRBs) from 2017 to 2020.

Source: WIND database.

But even after over a decade, LGBs remain experimental for the central government. MOF constantly gives the bonds new functions, while it also changes its mind over previous decisions. In , the proportion of LRB issuance suddenly drops from 25% in 2019 to zero in 2020 and STRBs also shrink from 28% to 10%. It is because the State Council asked local governments to pause applications for ‘fields related to land reserve and real estate’ in September 2019. There was no official explanation of the decision, but the probable reason was that these two bonds did not match the targets to ‘stabilise investment’ in that yearFootnote6 because they cannot directly generate investment. Given the turbulent financial circumstances, there may be more changes to this instrument in the future.

Designing LGBs specially to reduce financial risk

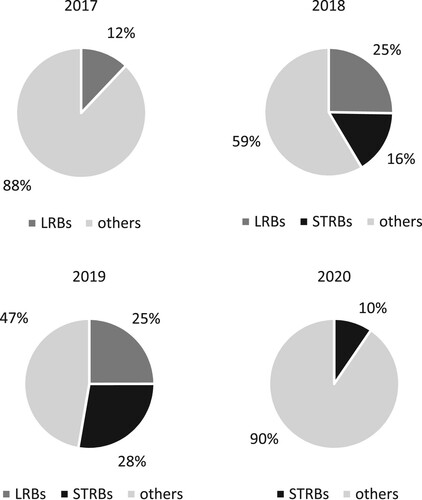

Although the operation of LGBs adds safety measures to local debts through supervision and regulation, enormous risky debts had already accumulated before 2015. To fix this, the State Council came up with the replacement bonds (RPBs) in 2015 as a category parallel to the GBs/SBs taxonomy. RPBs exist specially to swap ‘cumulative explicit local debts in any other form by the end of 2014’.Footnote7 Investors could buy RPBs of the amount equals to the debts they held from local governments. RPBs benefit both local governments and investors. For the former, RPBs have longer maturity periods which can relieve the pressure of intensive repayment. For the latter, RPBs are officially guaranteed by provincial governments and investors need not rely on implicit guarantees from municipal governments. RPBs also benefit investors’ long-term asset allocation, can be further traded in secondary markets, and generate tax-free profits. The State Council set a time limit for swapping all explicit debts from 2015 to 2018. As a result, there was a surge of RPB issuance and a consequent sheer rise of LGBs in total, particularly in 2015 (). By the deadline, the swapping process had almost finished. From 2015 to 2018, though the amount of RPBs was decreasing, this category occupied more than 60% of the total LGB issuance.

Figure 2. Amounts of local government bonds (LGBs), replacement bonds (RPBs) and refinancing bonds (RFBs) from 2009 to 2020.

Source: CELMA Platform; WIND database.

On the other hand, refinancing bonds (RFBs) were published by MOF in 2018. RFBs were first used to repay previous LGBs ‘meeting their due dates’,Footnote8 but the central government has given the category a new function. Though any borrowing outside LGBs is prohibited, there are still irregularities, particularly among lower level governments under pressure from large financing demand. In 2019 six counties in different provinces, most of which were in less developed western and north-eastern areas, were selected as pilot areas using RFBs to swap the implicit debts formed by LGFPs from 2015 to 2018. In less than two years, the swapping process has made notable progress. RFB issuance was worth 1.89 trillion yuan () in 2019, 80 billion yuan of which was to ‘repay cumulative local debts’, based on the disclosure reports. Since 2018, MOF has been publishing partial LGB quotas for new financing requirements for the next year in advance. Notice is usually given in November or December. Because of the Covid-19 disruption, the partial quota for 2021 was published in March 2021. Therefore, no LGBs for new financing demand were issued in January but there were 350 billion yuan RFBs in the same month, all of which stated ‘repaying cumulative local debts’. RFBs will play an increasingly important role in LGB issuance. With more LGBs approaching the due dates, RFBs are the first choice to further extend repayment. Meanwhile, though swapping implicit debts is a difficult task because of problems in classification and transparency, it will be carried out persistently unless there is a policy change at the central level.

THE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENTS

Following central guidance in selecting projects

Provincial governments need to assist the central government to collect and examine LGB applications from municipal governments. In such a process, provinces make decisions by combining central policies and local situations. The application and approval procedure requires cities and counties to hand up applications to the province first. There are plenty of materials they need to prepare, the most important of which is a demand form expressing their requirements and clarifying the ‘qualification’ of the projects. The main indicators across provinces are the same (). Provinces prioritize indicators in the ‘project importance’ column, and they usually select major projects directly linked to central planning schemes or in the key fields emphasized by the central government. In addition, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has a library of major projects led by firms across provinces. In 2019, the State Council encouraged local governments to provide LGB capital to projects achieving enterprise-oriented management, particularly to those approved by NDRC. Thus, whether the projects are in the NDRC library considerably affects the selection. NDRC at both central and provincial levels have also been providing suggestions to provincial financial departments in selecting projects. Projects with provincial funding or support are next. The last are regular municipal projects. Most project information files depict the projects as ‘echoing central/provincial emphasis on … ’ or ‘providing supporting funds to central/provincial-led major projects’.

Table 1. Demand form for the special bonds (SBs) of cities and counties.

Inspecting and correcting violations of central regulations on the use of money

Provinces also organize audits of the use of LGB capital and correct behaviours against regulations. The central government lists typical examples of misuse, including diverting money to other projects, using money as general revenue, and money retention caused by problems in project preparation or construction. The provincial audit department cooperates with its municipal counterparts to investigate misuse and then comes up with rectification measures. For example, in 2017 the auditing officers of Yunnan province and Xishuangbanna-Dai Autonomous Prefecture investigated the use of LGBs. They found that in bonds worth 438 million yuan, 1.2 million yuan were detained in the management department because of the slow progress of some projects in collecting land; 234,000 yuan were used as recurrent expenditure; and 3.4 million yuan of surplus capital were not transferred to the financial department.Footnote9 For these problems, related personnel were admonished and the money was rearranged. Because of misuse for different reasons, provinces are allowed to rearrange the money after reporting to MOF. In May 2020, Shandong suspended transferring money from SBs worth 1900 million yuan for 15 projects to lower level governments because the projects could not start as planned.

THE MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENTS

Using both LGBs and other financial methods

Municipal governments are the main bodies that actually use LGBs. Although LGBs have more restrictions than LGFPs, municipal governments need the bonds and have been proactively applying for their quotas. RPBs saved them from the huge pressure of local debts. Most explicit and implicit debts in the form of short-term financial products less than five years were held by municipal governments. With RPBs, municipal governments are free from explicit debts and can focus more on implicit debts. LGBs will continue to be crucial for municipal governments due to that RFBs are used to swap implicit debts. In the meantime, municipal governments have to use LGBs as the main development finance because other financing channels are restricted. In 2014, the State Council required LGFPs to stop performing fundraising tasks for local governments. In other words, local governments cannot inject land or issue guarantees to help companies raise money (Feng et al., Citation2020). Land reserve loans were banned in 2016, which means no financial institution can issue loans to the land reserve centres of local governments.

However, some drawbacks of LGBs set up obstacles to their adoption. First, the hierarchical application and approval procedure causes delay in municipal governments receiving the money transferred from provinces. Though MOF issues partial quotas for the next year in advance, the allocation of the province still takes time and cities often wait for months for the money. For example, Fuzhou, the capital city of Fujian Province, proposed allocation plan for the money for 2019 on 17 May.Footnote10 Moreover, only after the plan was approved by the municipal People’s Congress could the money be transferred to projects. Second, the quota management results in a large shortage of capital supply for projects. The first principle of MOF in designing the quotas is to maintain safe debt ratios instead of the real demands of projects. With the ongoing urbanization and rural revitalization, municipal officials still face difficulties in raising funds. Third, the requirement of project-level revenue expenditure balancing shuts the door on many projects that really contribute to development but generate less income and do not fit for GBs. Municipal governments still need other financing methods.

Although LGFPs can no longer raise funds for local governments, they are able to undertake development projects as self-financed enterprises. According to the disclosed reports, most developers and investors are LGFPs. Bank loans and Chengtou bonds of these companies can still be used to finance LGB projects. shows that the issuance of Chengtou bonds is on the rise along with LGBs, indicating that municipal governments still rely on LGFPs, but in a different way. Except for LGBs, there are three other sources for development finance: public–private partnerships (PPPs) (Zhang et al., Citation2015), government buying services and industry funds including government-invested and guided funds (Pan et al., Citation2020). These are good complements to LGBs though are under strict regulation from or banned by the central government. PPPs were introduced by MOF in 2015 and actively helped municipal governments over the next two years. Their amount even exceeded LGBs in 2017 (). Nonetheless, there was behaviour in violation of central regulations. Some municipal governments promised investors a minimum return with fiscal funds because certain public projects are of low yields. Such behaviour again added implicit debts. Therefore, in 2018 MOF published regulations on PPPs, and since then the number of projects under this mode has significantly decreased. Government buying services were at first a popular alternative for municipal governments. Some cities used this method to fund projects that did not qualify for LGBs. But the method also led to implicit debts since the payments came from fiscal funds. The consequent regulations ruled out the possibility of this mode being development finance again. Finally, industry funds were used to attract capital from markets to fund projects. This mode is smaller scale by nature and the problem here is very similar to that of PPPs. By the end of 2020, the accumulated amount of industry funds was 430 billion yuan, much less than LGBs, Chengtou bonds and PPPs.

Using LGBs to leverage market investments

For projects using LGBs as the funding source, bond capital cannot cover the total financing because of quota management. On average from 2015 to 2020, a city-level unit acquires 14.6 billion yuan of bonds per year, while a county-level unit only obtains 2.58 billion. With dozens of projects applied for, it is almost impossible for a project to be solely funded by LGBs. Thus, municipal governments use LGBs as a lever to draw capital from markets into projects, attracting more investment without increasing government debts. At the application stage, municipal governments set an appropriate proportion for LGB capital in the project budget. Then provincial governments and MOF decide if the proportion is viable by considering safety and efficiency. The funding proportion from LGBs is mostly between 10% and 60%. At first, the rest of the capital largely came from ‘own funds’ or ‘other funds’ of local governments, most of which is fiscal funds or the income of LGFPs. But there has been an increasing number of cases successfully introducing money from market investors. A series of water system improvement projects in Fuzhou in 2017 were mainly in the PPP mode. The size of the projects was 6.5 billion yuan, of which 10% of the stock rights were in the form of government funds while the remaining 90% were held by investors led by the Beijing Enterprises Water Group Ltd. The investors were responsible for 75% of the financing requirements except for the capital fund, and the Fuzhou government applied for up to 300 million yuan of SBs to pay for the projects.Footnote11 To further attract capital from the market, in 2019 MOF put forward the financing mode of ‘LGBs + PPPs’. For example, a project for establishing new industrial parks consists of numerous sections, some of which such as building construction can use SBs to deal with the intense financing demand over the short term, whereas others such as parking lots, water systems and electricity which need a long time to yield a benefit are suitable for PPPs.

DISCUSSION

The reason for the Chinese government adopting LGBs

LGBs are adopted by the Chinese government to raise development finance due to the continuous growth imperative. Though the bonds, particularly SBs, reflect how the government uses its credit and securitizes project revenue to create financial returns, it applies the returns to achieve developmental goals (Wu, Citation2020). The projects funded by LGBs should significantly contribute to development in key fields prioritized by the government. Such contributions need to be thoroughly demonstrated in the application materials. LGBs are also used by the government to relieve financial risks through swapping local debts in other forms and imposing regulations on bond deployment, which are distinctly invented in the Chinese context. Adopting LGBs with formal credit of the provincial government to replace LGFP debts with implicit guarantee of the municipal government reduces accumulated financial risks. The literature has explored the influence of changing regulatory settings on the process of financialization (Aalbers, Citation2009; Feng et al., Citation2021; Gotham, Citation2016). LGBs also suggest regulation characteristic of but different from the above cases. Regulation reintroduced by LGBs is mainly for the state rather than financial actors because most bond buyers are state-owned banks which act as the government expects. Such regulation does not solely facilitate or restrict financial actors but aims for statecraft. The regulations that solidify dominance, enrich categories and improve the ability to leverage capital of LGBs introduce and promote financial actors in the built environment. But more importantly, measures such as the principle of safe local debt ratios, project-level revenue expenditure balancing and the ban on diverting money prevent risks similar to those of LGFPs from happening again. The government uses regulation to establish LGBs as the main source for development finance and operates them under the premise that the risk can be controlled.

The multi-scalar state in deploying LGBs

Regulation is achieved through the centralized deployment procedure based on the multi-scalar structure of the Chinese government. The central government holds the decision-making power through the application procedure, quota system, and policy- and law-making authority that reflect its priorities on financial safety and rationality. Local governments cannot intervene in how the quota is produced but need to implement central policies unconditionally. The provincial government acts as the conjuncture between central and municipal levels to ensure that policy objectives and regulations from above are fulfilled in local implementation. As the lowest level, the municipal government has to prioritize LGBs though there are complex procedures, restrictions and regulations. It has tried to rely on other financial approaches with less intervention from upper levels and to use LGBs to leverage extra investment from the capital market, but these are regulated and supervised by the central government as well. The municipal government is left with very limited space to circumvent the regulations.

The interplay within the multi-scalar government revealed by LGBs contrasts with that in other contexts. Lower level governments in other countries receive less intervention from above than those in China. They can follow their own ways or even challenge upper level policies if they have different objectives. In Zhang’s (Citation2020) case in Canada, though the government of Toronto is ‘forced’ to implement federal and provincial guidance on embracing financial markets to fund affordable housing, it adopts its own methods with less financial elements and ‘urges’ upper level counterparts to provide more funding to the sector. In the case of LGBs, the municipal government cannot pressure upper level governments or replace the bonds with other financial methods.

The centralized LGB deployment is fostered by the institutional context of China. In contrast to the devolved fiscal responsibility, political power in China is centralized through the political hierarchy (Xu, Citation2011). Officials are appointed by the upper level government based on a complex assessment system rather than elected by people. Most officials attach great importance to the system for the further development of their political careers. In the case of LGBs, provincial governments do not have much debt to repay or many new projects to perform. Their main job is to help the central government with selecting projects and supervising the use of money. As the provincial level answers directly to the central, provincial officials are motivated to follow central policies because doing so benefits their political careers. Some scholars suggest that loyalty to the central level is important for promoting a provincial official (Opper & Brehm, Citation2007). Loyalty is the basis for building connections to senior officials in the central government who may play the decisive role in taking his/her political career one step ahead. Municipal governments have been facing huge expenditure pressure to promote economic growth and urbanization. LGBs change the operation mode for the financing of urban development projects, but the responsibility for and enthusiasm of municipal governments to maintain investment have hardly changed. They actively use LGBs and other methods to raise development finance. Their continuing enthusiasm can be explained by municipal official promotion. Compared with the promotion of provincial officials, the key indicators for municipal officials focus more on growth: exceptional performance in urbanization and local economy supported by ongoing investment (Chen et al., Citation2017).

CONCLUSIONS

Christophers (Citation2015, p. 232) deems that we need to ‘break open the black box’ of financialization, and see ‘institutions, legal contracts, and regulated, as well as informal, interactions’ around financial practice. From this point of view, this study uses LGBs to understand the role of the government in urban financialization. Some of the literature suggests that the government concedes to financial actors by excessively emphasizing financial techniques, interests and ideologies in urban affairs (Ashton et al., Citation2012; Waldron, Citation2019). However, there are situations in which financial actors do not dominate the decision-making of the government but are merely appropriate to deal with problems. The government applies financial practices but is not overwhelmed by them, regarding them as the ‘simply standard operating procedure’ of entrepreneurial tactics (Lauermann, Citation2018, p. 205), the ‘modest helper’ of the real economy (Wijburg, Citation2020, p. 14) or a tool to achieve developmental goals (Wu, Citation2020) and deal with the global financial crisis (Wu, Citation2021), in which financialization may even be a by-product of policy schemes (Bernt et al., Citation2017, p. 556). LGBs reveal that though the Chinese government mainly depends on debt financing that uses government credit and project revenue to leverage investment as urban development finance, it does not turn into a speculator obsessed with returns but pays attention to development and financial risks. Regulation is the main way of the state to introduce or restrict financial actors in the built environment. Regulation in LGBs, however, serves multiple purposes to strengthen the bonds as a financial approach to leverage capital, and more importantly, to ensure that reliance on the bonds does not generate excessive risk.

This study highlights the need to understand the multi-scalar structure of the government. The different objectives of and interactions among government levels saliently influence financialization (Belotti & Arbaci, Citation2021; Zhang, Citation2020). In the case of LGBs, upper level objectives decide the manifestation of urban financialization through a centralized deployment procedure. Before 2015, the overreliance of municipal governments on land and LGFPs boosted urban development but led to financial risks. Since the central government introduced LGBs to rectify local financial practices, the municipal governments have had to adopt this new method and abandon their previous ways despite supervision and regulations from above. For LGBs, the central and provincial governments have absolute authority on approving or denying applications from the municipal government, how much money it can get and how it should use the money. The municipal government can hardly intervene in such decisions. Based on various regulation measures and the centralized deployment procedure of LGBs, the multilevel government meticulously designs the urban financialization process to execute statecraft. The centralized and regulated urban financialization process brought by LGBs is not a simple result of a financial policy from the central government, but is created by the institutional regime in China of single-party rule and its multi-scalar hierarchy. Thus, LGBs could be a starting point to go beyond demonstrating the urban financialization process to critically review the role of governments in different contexts.

The operation of LGBs reveals varieties of urban financialization and development practice. The Chinese state intervenes heavily in development, which is described as ‘state capitalism’ (Alami & Dixon, Citation2020). Compared with liberal market economy, the Chinese model is believed to exert stronger influence on the rest of the world and challenge the West-dominated discourse in the 21st century (Arrighi, Citation2007). The case of LGBs calls for further consideration of China’s experience on both practical implementation into other contexts and theoretical implications. Every country operates in a development financing mode based on its specific institutional context. Different objectives across government levels are usually hard to coordinate in the regimes with partisan politics and officials elected from bottom up rather than appointed by superiors. The development finance of China comes mostly from capital-rich domestic investors with state-owned backgrounds, and thus the state holds a strong position towards financial actors (Wu, Citation2021). Such a circumstance hardly happens elsewhere, as global institutional investors alter behaviours of the state that lacks and craves for capital (Wainwright & Manville, Citation2017). From the perspective of comparative political economy, the case of LGBs in China explains the persistence and reconfiguration of state intervention to maintain a stable domestic policy structure under the pressure of globalization. This paper shows variegated state intervention, which may enrich the concept of state capitalism (Alami & Dixon, Citation2020) and state-led financialization (Pan et al., Citation2020; Wu, Citation2021).

Finally, we argue that the introduction of LGBs is not a process of urban definancialization, although the meaning of the term has yet to achieve consensus. By proposing a research agenda focusing on restraining financial practice in the housing sector, Wijburg (Citation2020, p. 14) suggests that there is a terminological contradiction in definancialization in which it can refer to both ‘the re-embedding of finance in a more regulated form, or the negation of any form of finance’. Nonetheless, we deem that the regulation of finance does not necessarily mean definancialization. In fact, Christophers (Citation2015, p. 230) argues that the financialization literature examines the influence of finance instead of finance itself. Finance in a regulated form does not have to change the way it affects subjects at multiple scales. Urban development projects still become liquid assets through LGBs for the government and investors to create returns. Compared with land reserve loans and LGFPs, the government introduces financial capital into more projects in the less profitable sectors which are usually rejected by investors. LGBs enhance the influence of the debt-machine mechanism on urban development (Peck & Whiteside, Citation2016), only the bonds are operated in a regulated context to make sure that the newly added debts are transparent and generate controllable risks, and the local government does not behave in an overly speculative and risk-laden way as it did with LGFPs. Emphasis on LGBs as the main source for development finance highlights that the multi-scalar government in China accepts a financialization approach with a ‘risk moderation strategy’ (Dagdeviren & Karwowski, Citation2021) instead of abandoning it. Therefore, in the way that O’Brien and Pike (Citation2019, p. 1470) suggest that in the UK the financialization of infrastructure has been ‘limited and attenuated’ with financial practices having to be operated in a conservative way by a state with risk-averse features, LGBs do not represent a departure from financialization. Rather, the instrument reflects a similarly constrained financialization with centralized and regulated characteristics.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In this study, local governments in China include provincial and municipal governments.

2. Local government debts are divided into three categories: the debts that local governments should pay with fiscal income; the debts guaranteed by local governments to pay if the debtors (mainly government departments and LGFPs) cannot do so; and the debts of government departments and LGFPs without government guarantees. The first is explicit debt, while the last two are implicit debts.

3. ‘Measures for budget management of LGBs in 2009’, http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2009-03/19/content_1263068.htm. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

4. ‘Management on quotas for NISBs’, http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-04/01/content_5182868.htm. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

5. ‘Instruction from MOF on the quota management on local government debt’, http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2016/content_5059103.htm. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

6. ‘Important messages from the executive meeting of the State Council on 4th September 2019’, http://www.gov.cn/guowuyuan/2019-09/05/content_5427497.htm. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

7. ‘Using RPBs to swap outstanding debts of local governments’, http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2015-06/11/content_2877793.htm. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

8. ‘Issuance and balance of LGBs by May 2018’, http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-06/14/content_5298701.htm. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

9. ‘Audit on the usage of LGBs in Xishuangbanna-Dai Autonomous Prefecture’, https://www.xsbn.gov.cn/101.news.detail.dhtml?news_id=42012. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

10. ‘Allocation of LGBs of Fuzhou in 2019’, http://www.fuzhou.gov.cn/zgfzzt/czzj/dfzfzqfx/201905/t20190517_2890669.htm. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

11. ‘650-Million-yuan water treatment projects of Fuzhou’, http://www.h2o-china.com/news/256075_2.html. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

REFERENCES

- Aalbers, M. B. (2009). The sociology and geography of mortgage markets: Reflections on the financial crisis. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(2), 281–290. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00875.x

- Aalbers, M. B. (2017a). Corporate financialization. In D. Richardson (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of geography: People, the earth, environment, and technology (pp. 1–11). Wiley.

- Aalbers, M. B. (2017b). The variegated financialization of housing. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 542–554. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12522

- Aalbers, M. B., Loon, J. V., & Fernandez, R. (2017). The financialization of a social housing provider. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 572–587. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12520

- Alami, I., & Dixon, A. D. (2020). State capitalism(s) redux? Theories, tensions, controversies. Competition & Change, 24(1), 70–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529419881949

- Anguelov, D., Leitner, H., & Sheppard, E. (2018). Engineering the financialization of urban entrepreneurialism: The JESSICA urban development initiative in the European Union. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(4), 573–593. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12590

- Arrighi, G. (2007). Adam Smith in Beijing. Verso.

- Ashton, P., Doussard, M., & Weber, R. (2012). The financial engineering of infrastructure privatization: What are public assets worth to private investors? Journal of the American Planning Association, 78(3), 300–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2012.715540

- Bahle, T. (2003). The changing institutionalization of social services in England and Wales, France and Germany: Is the welfare state on the retreat? Journal of European Social Policy, 13(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928703013001035

- Belotti, E., & Arbaci, S. (2021). From right to good, and to asset: The state-led financialisation of the social rented housing in Italy. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 39(2), 414–433. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420941517

- Bernt, M., Colini, L., & Förste, D. (2017). Privatization, financialization and state restructuring in eastern Germany: The case of Am Südpark. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 555–571. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12521

- Beswick, J., & Penny, J. (2018). Demolishing the present to sell off the future? The emergence of ‘financialized municipal entrepreneurialism’ in London. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(4), 612–632. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12612

- Bryson, J. R., Mulhall, R. A., Song, M., & Kenny, R. (2017). Urban assets and the financialisation fix: Land tenure, renewal and path dependency in the city of Birmingham. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 10(3), 455–469. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx013

- Chen, Z., Tang, J., Wan, J., & Chen, Y. (2017). Promotion incentives for local officials and the expansion of urban construction land in China: Using the Yangtze River Delta as a case study. Land Use Policy, 63, 214–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.01.034

- Christophers, B. (2015). From financialization to finance: For ‘de-financialization’. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(2), 229–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820615588154

- Christophers, B. (2017). The state and financialization of public land in the United Kingdom. Antipode, 49(1), 62–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12267

- Dagdeviren, H., & Karwowski, E. (2021). Impasse or mutation? Austerity and (de)financialisation of local governments in Britain. Journal of Economic Geography, 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbab028

- Du, J., Thill, J. C., Feng, C., & Zhu, G. (2017). Land wealth generation and distribution in the process of land expropriation and development in Beijing, China. Urban Geography, 38(8), 1231–1251. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1228373

- Feng, Y., Wu, F., & Zhang, F. (2020). The development of local government financial vehicles in China: A case study of Jiaxing chengtou. Land Use Policy, 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104793

- Feng, Y., Wu, F., & Zhang, F. (2021). Changing roles of the state in the financialization of urban development through Chengtou in China. Regional Studies. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1900558

- French, S., Leyshon, A., & Wainwright, T. (2011). Financializing space, spacing financialization. Progress in Human Geography, 35(6), 798–819. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510396749

- Gotham, K. F. (2016). Re-anchoring capital in disaster-devastated spaces: Financialisation and the Gulf Opportunity (GO) Zone programme. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1362–1383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014548117

- Guironnet, A., & Halbert, L. (2014). The financialization of urban development projects: Concepts, processes, and implications (Working Paper No. 14-04). http://hal-enpc.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01097192

- Hofman, A., & Aalbers, M. B. (2019). A finance- and real estate-driven regime in the United Kingdom. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 100, 89–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.02.014

- Klink, J., & Stroher, L. E. M. (2017). The making of urban financialization? An exploration of Brazilian urban partnership operations with building certificates. Land Use Policy, 69, 519–528. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.09.030

- Lauermann, J. (2018). Municipal statecraft: Revisiting the geographies of the entrepreneurial city. Progress in Human Geography, 42(2), 205–224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516673240

- Naughton, B. (2009). Understanding the Chinese stimulus package. China Leadership Monitor, 28(2), 1–12.

- O’Brien, P., & Pike, A. (2019). ‘Deal or no deal?’ governing urban infrastructure funding and financing in the UK city deals. Urban Studies, 56(7), 1448–1476. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018757394

- Opper, S., & Brehm, S. (2007). Networks versus performance: political leadership promotion in China (Working Paper). Lund University.

- Pan, F., Zhang, F., & Wu, F. (2020). State-led financialization in China: The case of the government-guided investment fund. The China Quarterly, 247, 749–772. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741020000880

- Pan, F., Zhang, F., Zhu, S., & Wójcik, D. (2017). Developing by borrowing? Inter-jurisdictional competition, land finance and local debt accumulation in China. Urban Studies, 54(4), 897–916. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015624838

- Peck, J. (2012). Austerity urbanism: American cities under extreme economy. City, 16(6), 626–655. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2012.734071

- Peck, J., & Whiteside, H. (2016). Financializing Detroit. Economic Geography, 92(3), 235–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1116369

- Tao, R., Su, F., Liu, M., & Cao, G. (2010). Land leasing and local public finance in China’s regional development: Evidence from prefecture-level cities. Urban Studies, 47(10), 2217–2236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009357961

- Töpfer, L. M. (2018). China’s integration into the global financial system: Toward a state-led conception of global financial networks. Dialogues in Human Geography, 8(3), 251–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820618797460

- Wainwright, T., & Manville, G. (2017). Financialization and the third sector: Innovation in social housing bond markets. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(4), 819–838. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16684140

- Waldron, R. (2019). Financialization, urban governance and the planning system: Utilizing ‘development viability as a policy narrative for the liberalization of Ireland's post-crash Planning system. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43(4), 685–704. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12789

- Weber, R. (2010). Selling city futures: The financialization of urban redevelopment policy. Economic Geography, 86(3), 251–274. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2010.01077.x

- Wijburg, G. (2020). The de-financialization of housing: Towards a research agenda. Housing Studies, 36(8), 1276–1293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1762847.

- Wong, C. P. H. (1991). Central–local relations in an era of fiscal decline: The paradox of fiscal decentralization in post-Mao China. The China Quarterly, 128, 691–715. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741000004318

- Wong, C. P. H. (2000). Central–local relations revisited the 1994 tax-sharing reform and public expenditure management in China. In International Conference on ‘Central–Periphery Relations in China: Integration, Disintegration or Reshaping of an Empire?’, 1–20. Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- Wu, F. (2019). Land financialisation and the financing of urban development in China. Land Use Policy, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104412.

- Wu, F. (2020). The state acts through the market: ‘state entrepreneurialism’ beyond varieties of urban entrepreneurialism. Dialogues in Human Geography, 10(3), 326–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620921034

- Wu, F. (2021). The long shadow of the state: Financializing the Chinese city. Urban Geography, 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1959779

- Xu, C. (2011). The fundamental institutions of China’s reforms and development. Journal of Economic Literature, 49(4), 1076–1151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.49.4.1076

- Ye, Z., Zhang, F., Coffman, D. M., Xia, S., Wang, Z., & Zhu, Z. (2020). China’s urban construction investment bond: Contextualising a financial tool for local government. Land Use Policy, 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105153.

- Yeşilbağ, M. (2020). The state-orchestrated financialization of housing in Turkey. Housing Policy Debate, 30(4), 533–558. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2019.1670715

- Zhang, B. (2020). Social policies, financial markets and the multi-scalar governance of affordable housing in Toronto. Urban Studies, 57(13), 2628–2645. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019881368

- Zhang, S., Gao, Y., Feng, Z., & Sun, W. (2015). PPP application in infrastructure development in China: Institutional analysis and implications. International Journal of Project Management, 33(3), 497–509. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.06.006