ABSTRACT

In the tradition of Christaller’s central place theory, policy and scientific studies delineate retail markets around predefined central places. Evolutions on the demand and supply side have changed where consumers shop and where stores are located. We use spatial network analysis techniques (Leiden detection algorithm) that allow for a bottom-up approach. The data were sourced from a questionnaire on shopping in Flanders (Belgium). The results show that community detection is able to deal with the geographical complexity of retail. Communities for daily goods shopping remain small, for recurring goods have become very large, even bigger than those for exceptional goods.

INTRODUCTION

In the tradition of Christaller’s central place theory, retail (and other services) can only survive when a threshold of demand is available within a range (Christaller, Citation1933). Retail centres, as central places for the supply of retail, can be identified by analysing the inventory of shops. Depending on the supply size, a retail centre can be placed higher or lower within a hierarchy. Once the retail centres are known, data on shopping trips can be used to delineate the catchment areas. This is usually done by assigning municipalities to the retail centres where a majority of the inhabitants do their shopping. However, data on actual retail flows are only scantily available, even in data-rich countries such as the UK (Lovelace et al., Citation2016; Siła-Nowicka & Fotheringham, Citation2019). They are usually sourced from surveys (e.g., Dolega et al., Citation2016), but also from loyalty card or other client data such as financial data (e.g., Waddington et al., Citation2018), social media (e.g., Lloyd & Cheshire, Citation2017; van Meeteren & Poorthuis, Citation2018), phone data (Lovelace et al., Citation2016), and Global Positioning System (GPS) data (Siła-Nowicka & Fotheringham, Citation2019). These new data claim to provide more information, often resulting in big data, but new information is seldom delivered in a satisfactory way because these data suffer from issues such as privacy, level of aggregation and problems with geolocation.

Since the 1960s, public authorities in charge of spatial planning and local economics have regularly asked economic geographers and urban planners to provide evidence and arguments for support and guidance for the regulation of retail (Davies, Citation1995). In most countries, regular attempts are made to depict urban hierarchies. These analyses are costly in terms of time and money: the inventories that have to be constructed are large and mostly not available through other readily accessible sources. Commercial business consultants also still frequently use the methodology to discover underserviced markets, often by using either basic statistics or simple gravity models (Hernández & Bennison, Citation2000; Wood & Browne, Citation2007). Large retail organizations, however, have begun using more advanced techniques (Reynolds & Wood, Citation2010) and have increasingly started cooperating with academia (e.g., Newing et al., Citation2015).

From the 1970s onwards, researchers have been struggling to amend existing theories in order to incorporate changes in retail hierarchies, for example, due to retail suburbanization and urban sprawl. Not only housing but also retail and other private and public services (culture, recreation, education, health, etc.) spread out from the traditional urban centres towards the periphery. In the Western world, this has become most apparent in the United States, where deconcentration has been abundant since the 1950s (Dyer, Citation2002; Lord & Guy, Citation1991; Nayga & Weinberg, Citation1999). In Western Europe, these trends were mitigated by restrictive retail policies (Cant, Citation2019; Fernandes & Chamusca, Citation2014; Guimarães, Citation2016). European Union (EU) lawmakers did introduce restrictions on national retail policies (Korthals Altes, Citation2016), though the effects on geographical retail patterns remain modest. While countries such as the Netherlands and Germany managed to control deconcentration, Belgium was confronted by significant retail–residential unbundling (Cant, Citation2019).

Naturally, such a deconcentration was only possible due to evolutions in consumers’ options and preferences (). Growing welfare, mobility and free time changed the traditional relationship between threshold and range values, as consumers can now bypass the nearest shopping clusters for more attractive options further afield. Furthermore, run shopping emerged as a common supplement to fun shopping. While fun shopping in Western Europe refers to the leisure aspect of luxury goods retailing as usually enjoyed in historical urban central places (out-of-centre shopping malls are relatively rare in the European context; Guy, Citation2007), run shopping focuses on efficiency: driving to out-of-town strip malls or ribbon developments focused on food and bulky goods retailing where shopping is organized rationally and efficiently. Economies of scale and scope (Basker et al., Citation2012; Guy et al., Citation2005; Reutterer & Teller, Citation2009) in the typical big-box developments ensure cheap and diversified assortments, while a location near a major road and with ample parking ensures convenience. Finally, sofa shopping emerged with the rise of e-commerce. This type of shopping further emphasizes efficiency (Kirby-Hawkins et al., Citation2019), though it is certainly not yet ubiquitous and these customers still tend to be young, well-educated, affluent and male (Beckers et al., Citation2018; Clarke et al., Citation2015; Kirby-Hawkins et al., Citation2019).

These evolutions have resulted in fragmented retail flows. The main research question of this paper is therefore: How has the traditional central place organization of retail developed as a result of societal and technological changes, and how resilient has the traditional urban hierarchy proven to be? To answer this question, a novel approach is required, given that the traditional top-down perspective, which starts with the identification of central places, is unable to capture the observed fragmentation. This paper, therefore, also explores whether a more bottom-up methodology, meaning first delineating shopping hinterlands and then identifying new central retail places, would better suit the new reality. To delineate the catchment areas, we used community detection.

We start by describing how the retail landscape has developed from a hierarchical central place logic into a far more fragmented and complex retail landscape due to changes in consumer behaviour and technological and organizational developments in the retail sector. Subsequently, we describe the methodology used to capture the geography of complex consumer behaviour in the changing retail landscape. The empirical study was carried out using survey data on consumer flows in Flanders from 2014. In the final section, the results are discussed, and we reflect on limitations, policy recommendations and further research.

TOWARDS A NEW RETAIL LANDSCAPE

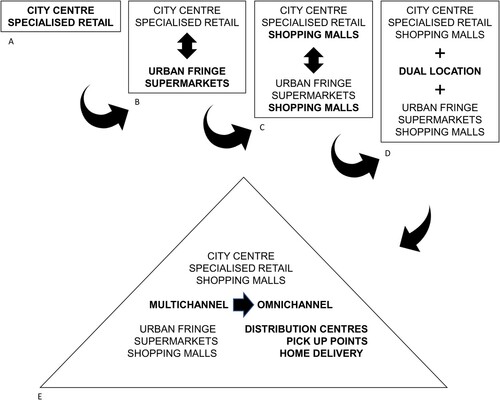

In Europe, retail has its origins in the medieval markets near castles and monasteries. Their inhabitants were the first consumers who could buy the surplus of traditional production. Where consumption became sufficiently large and stable, permanent shops emerged on central locations (i.e., squares and major junctions) (A) (Froy, Citation2016; Lesger, Citation2011, Citation2007; Van Damme & Van Aert, Citation2014). For a long time, retail remained small in scale. A true spatial retail revolution only occurred after the Second World War, although important organizational, commercial, technological, distributional and marketing evolutions had already taken place in the mid-19th and early 20th centuries (Crossick & Jaumain, Citation2019; Dyer, Citation2002; McArthur, Citation2013).

Since then, large supermarkets and hypermarkets, as well as other big-box developments in the urban periphery and – in Western Europe to a far lesser extent than in the United States – peripheral shopping malls, have profoundly changed traditional shopping. In Western Europe, it started with the scale increase in the food retail sector. While still mostly small scale and traditional until after the Second World War, the food retail sector became dominated by the supermarkets and hypermarkets of multiple retailers from the 1960s onwards (B) (Alexander et al., Citation2008; Jacques, Citation2018; Van den Eeckhout, Citation2012). This new and rational organization of retailing resulted in a supply shift from centres to the periphery. Centres generally lacked the necessary space or real estate to house large-scale retailing or provide substantial parking facilities, and additionally, the market was shifting to the periphery due to the suburbanization of the middle classes (Guy, Citation1998; Péron, Citation2001).

Most of the decentralization of retailing in Western Europe consisted of single or small groups of standalone shops, which occupied new, large and rationally organized premises in suburban areas along major approach roads close to new suburban residential areas; so-called ribbon developments and strip malls. Three waves of decentralization can be discerned (Fernie, Citation1998, Citation1995; Schiller, Citation1986). After the first wave in the 1960s, with food retailing (supermarkets and hypermarkets), the second wave started around 1980, and typically concerned big-box developments selling bulky items (e.g., furniture, DIY items, white goods, plants and gardening items, etc.). A third wave, the decentralization of luxury goods (e.g., clothing, shoes, etc.), started in the early 1990s in Western Europe but failed to fully materialize as policies largely quelled peripheral shopping malls.

On a global scale, the emergence of planned malls is undoubtedly one of the most visible forms of decentralization of the retail sector (C). A planned mall is a grouping of commercial facilities (not only retail) that are designed, developed, planned and organized as a whole, usually mostly focused on fun shopping. Shopping malls became widespread in North America in the 1950s and started appearing in Europe in the 1960s (Kellerman, Citation1985). In the United States, more than half of the total retail trade passed through shopping malls. In the UK, for example, this is far less; there, most malls are located in traditional city centres (Guy, Citation2007). Similar observations can be made for most of Western Europe, with shopping malls mainly being a central urban phenomenon.

From the 1990s onwards, in Western Europe at least, deconcentration trends seem to have peaked (Guy, Citation2007; Thomas & Bromley, Citation2003; Wrigley et al., Citation2015), and some urban retail centres started to flourish again thanks to regeneration efforts (e.g., Lowe, Citation2005). This resulted in a dual retail landscape with pleasant central shopping areas for fun shopping and rational peripheral locations suitable for run shopping (D). Many chains now follow a dual strategy of being present in both city centres as well as along approach roads. This is very clear in the food sector, for example, where big-box developments have increasingly been supplemented with small ‘urban formats’ (Elms et al., Citation2010; Hood et al., Citation2016), although this trend can also be observed in luxury and even bulky goods retailing. Secondary shopping centres and scattered stores have a hard time surviving in this dual-strategy landscape.

In recent years, e-commerce has emerged as a third channel, accommodating sofa shopping and home delivery, further complicating retail hierarchies (E). Multichannel retailers offer goods through the various sales channels. E-commerce is still dominated by pure online players, although most bricks-and-mortar retailers also have an online presence nowadays. The Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated this trend towards multichannel retailing (Beckers et al., Citation2021). For some products, such as travel and insurance, e-commerce has been extremely disruptive for traditional bricks-and-mortar retailing (Verhoef et al., Citation2015). However, the interplay between distribution channels (run, fun and sofa shopping) is often still lagging (Herhausen et al., Citation2015; Verhoef et al., Citation2015; Zhang et al., Citation2010), although the degree of integration from multichannel towards omnichannel depends on the retailer (Emrich et al., Citation2015). For many goods, the future probably lies with omnichannel retailers (Zhang et al., Citation2010) due to significant competitive advantages over pure online players (Herhausen et al., Citation2015). There does not appear to be a less loyal customer than an online customer, which means that material stores remain crucial. Moreover, both retail warehouses and inner-city stores are increasingly used as pick-up points or even storage for e-commerce (Gorczynski & Kooijman, Citation2015). In addition, flexibility and disruption are creeping into the retail landscape through new (e.g., pop-up shops; Jones et al., Citation2018, Citation2017; and local food systems; van Gameren et al., Citation2015) and renewed (e.g., reassessment of mobile retail; Carey et al., Citation2011; McEachern et al., Citation2010) phenomena. The latter, in turn, brings us back to the revival of the markets that started it all. While large, attractive shopping locations seem to be e-resilient, medium-sized retail clusters have and will continue to experience a profound negative impact (Singleton et al., Citation2016).

As a result of societal and technological transitions, the traditional hierarchical and centre–periphery relations in the organization of retail have changed into more complex and blurred retail landscapes. The theory of market areas in the meantime did evolve significantly beyond the basic central place model. Hanjoul et al. (Citation1989), for example, describe a number of geographical properties of theoretical market areas. The basic building blocks of their analysis, however, still focus on urban influence and transportation cost functions. The traditional approach of first identifying retail centres and subsequently delineating retail hinterlands seems less appropriate to capture the complexity of contemporary retail relations. Over the past decade, methods of community detection have proven to be appropriate and successful in the analysis of complex and networked relations in social sciences. It has been used to analyse many different types of geographical data, covering diverse topics such as mobile telephony patterns (Blondel et al., Citation2010), commuting regions (Kropp & Schwengler, Citation2016; Nelson & Rae, Citation2016; Verhetsel et al., Citation2018), daily intercity travel (Zhang et al., Citation2018), research and development (R&D) networks (Barber & Scherngell, Citation2013), interurban firm networks (Martinus & Sigler, Citation2017) and migration patterns (Tranos et al., Citation2015). To our knowledge, community detection has not yet been used in retail geography studies, but we believe that the aforementioned changes in the retail landscape can be better explored and understood through a bottom-up approach such as community detection analysis. This paper aims to answer the following questions:

Considering retail, to what extent does the traditional central place landscape survive?

Do ‘peripheral’ shopping areas emerge, and are they strong enough to compete with the traditional shopping areas?

Can we observe the complexity and fragmentation caused by both decentralization and e-commerce?

Is community detection a useful tool to delineate shopping hinterlands and identify new central retail places in the described networked retail landscape?

CASE STUDY OF RETAIL LANDSCAPES IN FLANDERS (BELGIUM), DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Belgium has a long history of studies identifying central places and delineating their hinterlands. Goossens (Citation1963) conducted the first methodological study in the region regarding the hierarchy and hinterlands of urban centres in the north-east of Belgium. This was later replicated and extended to the whole of Belgium and published in the National Atlas by the National Committee for Geography for use in the first Belgian national spatial planning process (Goossens & Van der Haegen, Citation1972). It was followed by one of the first European comparative studies on urban settlements (Van der Haegen et al., Citation1982) with an extension to very small settlements and an analysis of the relationships between market size and market area. A complete picture of the Belgian urban hierarchy was last published in the 1990s (Van Hecke, Citation1998).

The most recent study in this tradition was conducted by consultants (IDEA Consult et al., Citation2014) (). They identified central places and hinterlands based on shopping flows between Flemish municipalities, collected mostly through telephone interviews in 2013. However, data were only available for Flanders, the northern part of Belgium, and the consultants only used a subset of the retail flows collected. However, as more information is available from the original surveys, these data are further analysed in this paper. In the survey, a distinction was made between daily goods, recurring goods, exceptional goods, culture and hospitality. Daily goods, such as groceries, are purchased frequently, and recurring goods are purchased with a certain regularity, such as clothing, jewellery and books. Exceptional goods are purchased irregularly, and include white goods, furniture and cars. The culture and hospitality sectors are not further discussed in this paper, as we focus on the retail sector. Some limited information on online consumption patterns was collected as well. Ultimately, 30,691 interviewees provided information on shopping flows between the 308 Flemish municipalities. This is a representative sample for every municipality. Each interviewee was asked to indicate their primary retail destination for each of the aforementioned categories. The interviewees received detailed information about what was included in each product category. Unfortunately, no data were collected for the Brussels Capital Region, which, as a major city and enclave within Flanders, is an important destination for shoppers from the surrounding areas.

This resulted in a 308 × 308 matrix for each product category, detailing the shopping flows within and between municipalities. The values represent the percentage of respondents in municipality X who indicated that municipality Y was their primary retail destination for a certain product category. By combining these data with municipal population data, we obtained estimates on the number of people in a municipality who rely on their own or another municipality for their shopping. Internal shopping trips or ‘loops’ are thus considered. The described dataset is freely available at www.detailhandelvlaanderen.be. More specifically, a top 10 of shopping destinations is provided for every municipality. Generally, there are only significant flows from any given municipality for any of the product categories to a maximum of five or six other municipalities.

In contrast to the 2014 study, we approached the dataset from a network perspective to identify the hierarchy of the retail sector with a bottom-up approach, without predefined central places, and we included all three shopping flows instead of only those for recurring goods. As stated, community detection has recently proven to be appropriate and successful in the identification of hierarchical structures in complex and networked relations (Beckers et al., Citation2019). Community detection algorithms group nodes with higher link densities within communities.

Many different methodologies to delineate communities exist. A frequently applied community detection algorithm in our study area is the ‘Louvain method’, proposed by Blondel et al. (Citation2008). The Louvain method is a popular modularity optimization approach that scores well in comparative benchmark analyses (Lancichinetti & Fortunato, Citation2009; Yang et al., Citation2016). Optimizing modularity implies maximizing the fraction of links within communities compared with the expected fraction in a randomized network with the same characteristics. The optimization is considered successful when a modularity between 0.3 and 0.7 is achieved (Newman & Girvan, Citation2004). The Louvain method suffers from three well-documented issues. First, the algorithm may find communities that are internally disconnected (Traag et al., Citation2019). The origin of this issue lies in the iterative nature of the Louvain algorithm, where nodes acting as bridges within the community might be moved to another community. Although this occurs only when it improves the overall modularity, it might yield disconnected communities as an artefact. The second issue is the resolution limit, resulting from the Louvain method being a modularity-optimization approach that tends to operate at a course level, limiting the identification of small communities (Fortunato & Barthélemy, Citation2007; Lancichinetti & Fortunato, Citation2011). This results in a similar outcome compared with the first issue (i.e., ‘clustered’ communities). The last caveat is the dependence of the communities on the input order of the nodes (Blondel et al., Citation2008).

To cope with these issues we applied a recent modification of the Louvain method, the so-called Leiden algorithm (Traag et al., Citation2019). This approach further outperforms the Louvain method and most other algorithms (Osaba et al., Citation2020; Traag et al., Citation2019). The modification adds a refinement phase by identifying subcommunities in the aggregated ones calculated by the traditional Louvain algorithm, and subsequently continues the iteration with those subcommunities. In a sense the Leiden algorithm takes one step back in each iteration to prevent the formation of disconnect communities. An added value of the Leiden algorithm is that it allows for the inclusion of the direction of flows, although this did not seem to impact the results in a significant way. Our chosen implementation of the Leiden algorithm maintains a modularity optimization, making it vulnerable to the resolution limit. While this is relevant for our study and should be taken into account in our analysis, we partly circumvent the issue by comparing the flows related to different types of products. Finally, the algorithm is run a number of times with a randomized input order to solve the last issue. Empirically, 1000 runs proved to yield stable results (Thomas et al., Citation2017). The nodes, that is, the municipalities, were grouped together when they ended up in the same community in at least 70% of the iterations. All the calculations were performed in python, using the leidenalg package (Traag et al., Citation2020) in python 3.7.

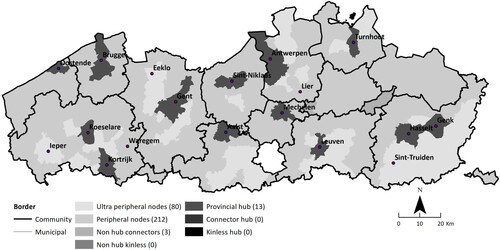

Community detection allows for the delineation of service areas. Their size and quantity provide insights in the hierarchical organization of the network, especially when comparing different types of shopping trips. In order to identify the position of the municipalities within the communities and thus derive a hierarchy of places, we calculated parameters of node connectivity as proposed by Guimerà and Nunes Amaral (Citation2005). The within-module degree z measures the connectedness of a node within its community. The participation coefficient P indicates the participation in the overall network. Guimerà and Nunes Amaral (Citation2005) defined seven types of nodes based on the combination of both parameters (). Ultra-peripheral and peripheral nodes are at the fringe of the network, with low connectivity to nodes both within and outside their community. Non-hub nodes are not hubs due their low internal connectivity, yet they are strongly embedded in the overall network. As a result, they do not play an important role in the formation of the communities. Provincial and connector hubs are the most important types from a community perspective. Provincial hubs represent important local centres, and connector hubs play a regional role due to their better connectivity outside of the community. Finally, kinless hubs are equally well connected to the entire network. Hubs by definition can be regarded as central places.

Table 1. Parameters of node connectivity in a network.

RESULTS: RETAIL LANDSCAPES IN FLANDERS FOUND THROUGH COMMUNITY DETECTION

As central place theory combines two dimensions, first, the identification of the central places and, second, the delineation of service areas, we analyse these in separate paragraphs. Because we use a bottom-up strategy we first discuss the emerging communities as a proxy for service areas. Only afterwards we calculate the hubs as the operationalization of central places. Before reporting on the network analysis, the next paragraph first discusses some data on the share of e-commerce. Further information is also provided on trips with origins and destinations within the same municipality (i.e., local shopping trips or loops).

Share of e-commerce

About 55% of the respondents indicated that they had made online purchases in the past. While this number may seem low, one should take into account that the interviews took place in 2013. However, the number does coincide with findings from a 2016 database reported in Beckers et al. (Citation2018). Flanders, as well as Belgium as a whole, was and still is lagging in e-commerce penetration, certainly when compared with European frontrunners (Eurostat, Citation2021). There are, of course, large differences between activities, for instance with books, computer appliances and software being bought online very regularly and goods such as cars and furniture being bought online very infrequently.

Approximately 20% of the respondents indicated that they sometimes buy recurring goods through e-commerce. For daily and exceptional goods, only 6% of the respondents sometimes buy online. The share of total expenditure in each of the product categories was very low: about 1% for daily and exceptional goods and about 4% for recurring goods. While and E and the accompanying text argue that the potential impact of e-commerce on the physical retail landscape is substantial, the current overall impact on bricks-and-mortar shops still remains modest, at least in the study area.

Local shopping trips

On average, 65% of daily shopping trips is done in one’s own municipality (). As expected in the densely urbanized Flemish region (Verhetsel et al., Citation2010), most people find grocery stores and other goods bought with great regularity in their own municipality. While there has been a significant retail sprawl of super- and hypermarkets (B), market saturation and centre–periphery dual location strategies (D) ensure the local availability of grocery stores. Only in 68 of the 308 Flemish municipalities, fewer than half of the daily shopping trips are made locally.

Table 2. Share (average %) of local purchases.

Shopping for recurring goods mostly takes place outside of one’s own municipality (only 26% is done locally). It is astounding that local shopping is more common for exceptional goods, at 38%. The most likely reason for this is that peripheral shopping malls were largely quelled by planning authorities, so step C in never fully materialized. Step B, peripheral big-box developments, did transpire, and exceptional goods retailers had more opportunities to settle outside of urban areas than recurring good retailers.

In both major and regional cities, more than 80% of all types of shopping trips can be done locally. In the smaller municipalities, about a quarter of the recurring shopping trips and about a third of the exceptional shopping trips can still be done locally. Again, it is astonishing that the number of local exceptional shopping trips is higher than the number of local recurring trips.

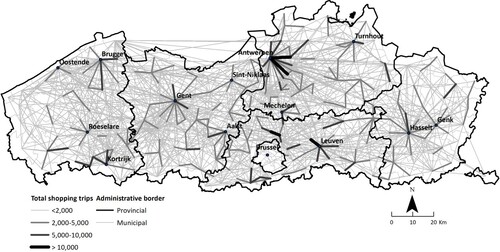

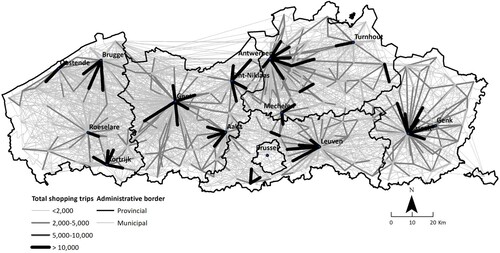

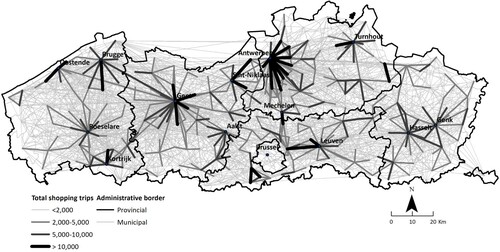

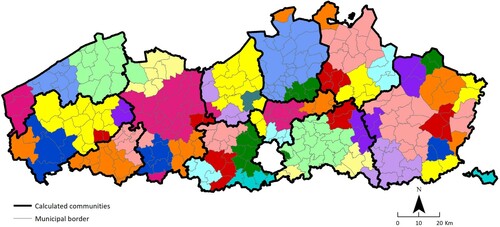

Service areas approximated by community detection

map shopping trips across municipalities for daily, recurring, and exceptional shopping. These are all somewhat oriented towards central shopping areas. In the background, however, randomly dispersed shopping trips are clearly present. This can be seen as an indication that consumers indeed ‘shop around’. At first glance, seems to suggest that central place theory still applies to exceptional goods shopping. The major and regional cities clearly emerge. A closer look at the underlying numbers, however, shows that the reality is more complex (see the Appendix in the supplemental data online). In the Antwerpen region, for example, there is a significant inward movement towards the central city, while there is also a significant outward movement from the central city to the periphery. This coincides with the observation that a significant number of shops for exceptional goods have settled in the periphery, usually along major approach roads (B), where they accommodate run shopping, but. The sprawl of these shops goes beyond the central cities into suburban areas. Furthermore, there is a dispersion in all directions, that is, traffic does not just occur radially but also tangentially. Nonetheless depending on the administrative delineations of the municipalities these peripheral shops can still be located within the city. It should be remembered that a significant majority of customers shop in their own municipality. However, high personal mobility levels allow people to buy their goods in other municipalities.

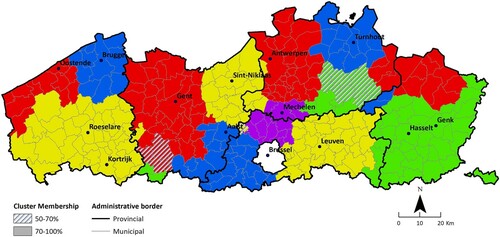

show the results of the community detection. One can consider the resulting regions as coherent service areas because municipalities with major reciprocal shopping trips are grouped together. Dashed areas are municipalities that tend to switch community quite often over iterations. summarizes the results and some characteristics of the community detection. The presence of only 1 isolate (for daily shopping) and a high average modularity are satisfying. As expected the number of communities for daily shopping trips is far higher than for recurring and exceptional shopping trips. It means that daily shopping trips are carried out in smaller areas. The calculated radius indicates that daily shopping trips occur within 11.5 km ().

Table 3. Results of community detection.

Table 4. Surface area of different shopping trips.

In contradiction to central place theory and former empirical analysis the number of communities for exceptional shopping trips is higher than for recurring shopping trips. The surface and radius in indicate that the travel distance to exceptional goods has become smaller than to recurring goods. Recurring goods are found mainly in historical central shopping areas used by fun shoppers, while exceptional goods retailers tend to settle in large peripheral developments that can be found sprawled across Flanders and which accommodate run shopping. This is again an indication that peripheral shopping malls are rare in Flanders due to restrictive retail policies and the situation in C thus never fully materialized, while retail sprawl towards the urban fringe in the form of big-box shops (B) did.

This results in an increased proximity for exceptional goods, in the end making them less exceptional. When comparing the recurring shopping communities to the map made using the traditional methodology on the same data (), similar spatial patterns are visible. However, smaller service areas identified by the traditional methodology have merged into joint communities. So by the proposed bottom-up approach using all recurring shopping trips, connectedness between service areas of former predefined recurring shopping centres was exposed. provides further information on the difference between the traditional methodology (column IDEA consult) and community detection (column recurring goods), showing that the service areas resulting from community detection are indeed much larger than those calculated through the traditional methodology.

Figure 9. Community borders of recurring shopping trips overlayed on service areas identified using the bottom-up approach (shaded areas).

Source: Elaborated from IDEA Consult et al. (Citation2014).

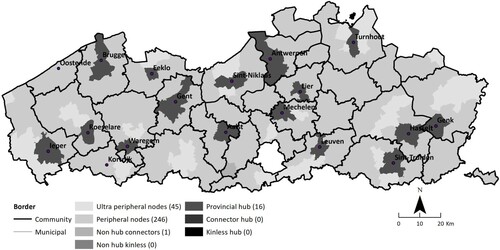

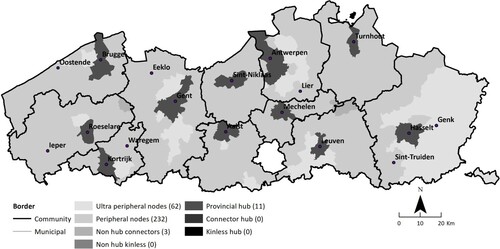

Central places – hubs

The node characteristics are mapped in . All but one of the identified hubs are provincial hubs. These can be considered as the central places of service areas and provide information on hierarchies among municipalities. gives an overview of the identified central places, also compared with the results of Van Hecke (Citation1998). There is a remarkable correspondence between the two sets of results, arising from the fact that urban systems are relatively inert over time. Also in the older studies mentioned in the case study section of this paper, few changes manifest themselves between 1960 and 1998. Examples of cities whose role did change are Roeselare, Turnhout and Genk, which grew significantly over the course of the past century. All major and regional cities identified in 1998 (data from 1990) are still central places for exceptional and recurring shopping trips in our analysis, except for Oostende and Genk. These two cities experience competition from the nearby very attractive historical cities Brugge and Hasselt, and consumers seem to prefer these attractive shopping places for fun shopping. Van Hecke (Citation1998) did identify many more smaller cities as central places, not just for daily goods shopping but also for recurring goods. These smaller cities do not emerge as hubs anymore, certainly not for recurring goods.

Table 5. Central places emerging as provincial hubs.

Almost all service areas have one or no provincial hub. Only twice communities with two hubs emerged, both in the map for exceptional shopping (): Hasselt and Genk in the east, and Roeselare and Kortrijk in the west. Hasselt-Genk is frequently considered to be a twin-city in the context of Flemish urbanization studies. Since exceptional goods retailing is often found in the periphery (B), Genk functions as a central place in the network, even though it cannot compete with the more attractive historical shopping centre of Hasselt for recurring goods (A). The separate service areas for recurring goods of Roeselare and Kortrijk (A) merge to one service area for exceptional goods (B), but both cities serve as a central place in both maps ( and ).

For daily shopping Kortrijk and Oostende are the only regional cities that do not function as a central place. Kortrijk suffers from extensive peripheral developments, while Oostende has to share the market for daily goods with well-equipped coastal municipalities. Another 12 daily goods communities do not have a hub. Daily shopping destinations are spread over the service area and consequently no central place can be identified. Only few small cities function as a central place in their service area for daily goods (Ieper, Waregem, Eeklo, Lier, Sint-Truiden). These are all small cities serving mostly rural hinterlands. These results teach us that especially for shopping trips of daily goods, consumers no longer focus on one hub but have several daily shopping opportunities within their range. The traditional approach of starting with the identification of central places and only taking into account the dominant direction of shopping trips, overlooked this complexity. Presumably there were also dispersed shopping trips from the 1960s onwards (B), but usually only the dominant and sometimes the second most important shopping direction was recorded and analysed. Our approach allows to uncover the complexity behind the shopping trips, which was not done before.

The node characteristics also provide insights in the potential occurrence of the resolution limit in this study. As mentioned, the choice for a modularity-optimization approach potentially limits the identification of small communities. This substructure would result in municipalities that are only loosely connected within their communities, that is, ultra-peripheral nodes. Such nodes are mostly present in the east or our study area and around regional and particularly major cities (Antwerpen, Gent, Leuven). In the case of the eastern municipalities, the influence of cross-(language) border linkages and the presence of shopping malls in Genk and Maasmechelen may be the cause of low within-module degree. Yet we are unsure whether a separate community would be more correct, given the absence of foreign municipalities to complete the community. The other cases mostly represent affluent suburbs with a rural landscape strongly focused on the nearby central place, limiting the connectedness with other municipalities in the community.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

For decades, Christaller’s central place theory dominated not only the academic research agenda on retail locations but also the practice of consultants advising retail entrepreneurs on location strategies and, to a large extent, the retail policies that guide the granting of location permits by authorities. The classical methodology starts with an inventory of shops in municipalities, followed by a delineation of areas predominantly focused on the identified central places. Typically, a hierarchical spatial structure emerges from a traditional operationalization of the interplay between the core concepts of threshold and range. Within retail geography the use of spatial network analysis techniques is quite novel. It allows to capture the spatial heterogeneity of consumer behaviour, that is, not only the dominant shopping direction but also smaller and blurred flows are included in the construction of the retail landscape. Only after delineating retail communities, within which the shopping relationships between municipalities are stronger than those with external places, shopping central places are identified based on the characteristics of the nodes within the retail network.

This bottom-up network approach allows for an objective confirmation of field data that indicated the dispersal of some retail activities and the concentration of others. Most of the resulting retail communities are spatially contiguous, which on the one hand means that distance still matters, but on the other hand that the many overlapping networks prove that growing mobility and welfare add complexity to the retail landscape. While the data used are suitable for network analysis, they do have certain limitations. First, the spatial aggregation level (municipalities) does not allow for differentiation between central and peripheral locations within cities. If it did, then this would allow for a more detailed analysis of centralization and dispersion trends. Second, interregional and international shopping trips were insufficiently recorded to include them in the analysis. These trips do play an important role in language and international border regions and might alter the strength of the communities there. Particularly regrettable is the lack of shopping flows between Brussels and Flemish municipalities, which is due to the choice of the commissioner of the study to only collect data within the Flemish provinces. Third, the data lack information on time of day and day of the week or season, while temporal variations in communities are likely and interesting to consider. Finally, the data rely on respondents identifying the municipality of their shopping destination; other data (e.g., financial transaction data) could provide this information in a more direct and accurate manner.

As expected, the results of the analysis differ between product categories. The majority of daily goods shopping is, in line with central place theory, a local affair, despite the substantial retail sprawl of super- and hypermarkets (B). As in other European countries (e.g., Wood & McCarthy, Citation2014), the grocery sector is very mature, even saturated and retailers started implementing a central–periphery dual location strategy (E), meaning a good variety of local options is usually available, even in rural areas (Cant, Citation2019). Similarly, van Leeuwen and Rietveld (Citation2011) found that small European towns function as important local shopping destinations for daily goods. A retail landscape with little hierarchy is therefore a logical result. Still, the reported flows are more complex than one would expect, and a significant number of consumers choose to do their shopping outside of the municipality where they reside, probably bypassing the closest option. This increased complexity is likely due to trip chaining (e.g., commuting and family trips) as well as supermarket brand loyalty (Newing et al., Citation2015).

Recurring goods shopping is still highly centralized, as central place theory would predict. The well-known major and regional cities function as the main hubs. Both the comparative aspect and the fun aspect are of course extremely important for these types of goods. There are few retail configurations that can accommodate this type of shopping, that is, shopping malls are the only true alternative to historical city centres (C). As in other European countries (Guy, Citation2007), the relevant authorities in Flanders and in Belgium as a whole have been reluctant to issue permits for peripheral shopping malls, meaning the historical city centres retained their function as fun shopping hotspots. When compared with previous studies, however, shows that catchment areas have merged. In other words, the number of cities acting as recurring goods hubs has decreased and the retail landscape has become more hierarchical. The resulting communities are very similar to those for mobile telephony (Blondel et al., Citation2010) and commuting (Verhetsel et al., Citation2018). Spatial, social, work and retail environments thus seem to be converging. Not only did small and regional cities lose a lot of fun shopping to major cities, some recurring goods shopping historically bound to the urban core was also replaced by run shopping in new peripheral big-box developments.

Interestingly, in comparison with the traditional conceptualization, different patterns were observed between recurring and exceptional goods. The lower share of local (within municipality) purchases in recurring shopping trips compared with exceptional shopping trips hints at a more dispersed landscape of shopping for exceptional goods. From Christaller’s central place theory, we would expect that shopping for exceptional goods would occur only in major cities due to large thresholds and ranges. Following the same reasoning, recurring goods are expected to be purchased more locally than exceptional goods, given the intermediate thresholds and ranges. The observation of the inverse effect, however, is the result of evolutions in welfare, mobility and retail organization (). Thus, we found that exceptional shopping trips are much more complex than central place theory would predict. There are trips from the periphery to central locations but also from central locations to the periphery and between peripheral locations. Additionally, a further sprawl of shops for exceptional goods even beyond the urban peripheries was observed. Rather than the historical monocentric configuration, the Flemish retail landscape for exceptional goods has now become dispersed, with major approach roads functioning as the major anchor points for ribbon developments and strip malls, complemented by isolated locations that allow for large-scale retailing and parking facilities and that accommodate flexible and fast travel by car and thus run shopping. As a result, the retail landscape for exceptional goods is less hierarchical than could be expected from using traditional approaches.

As the recurring goods retail landscape thus became more hierarchical, the exceptional goods retail landscape became more dispersed. Both trends are consistent with observations that the high streets in small and medium-sized cities in Flanders are struggling. Similar patterns can be found across Western Europe (e.g., Delage et al., Citation2020, for France). While it is argued that medium-sized cities are particularly exposed to the risks of e-commerce (Singleton et al., Citation2016), the respondents indicated – in line with other Belgian datasets (Beckers et al., Citation2018) – that online shopping only represented a small share of their expenditure. Indeed, these trends of decline in secondary retail clusters have been present for decades, long before the rise of e-commerce (Delage et al., Citation2020). The reasons for this are very complex and not entirely clear (Delage et al., Citation2020). Ultimately, it seems that consumers are simply willing to bypass these small and medium-sized cities for more attractive major retail centres, both central (for recurring goods) and peripheral (for exceptional goods).

While the use of complex network algorithms allows the identification of hierarchical regions, it is important to note the impact of the chosen algorithm on the findings. We calculated our results by using both the Louvain and the Leiden algorithm. Our conclusions regarding hierarchy between recurring and periodical goods are better supported by the Leiden algorithm, potentially due to its strength to prevent the occurrence of disconnected communities. We do, however, remain advocates of the application of these methods in social sciences, especially considering our findings on the differences between the top-down and bottom-up approach (see the discussion of ).

As discussed in and E and the accompanying text, online retail potentially has an important impact on consumer behaviour, the physical retailing landscape and shopping flows. E-commerce penetration was, however, still minor when the interviews used for our analysis were conducted. In subsequent years, its influence increased, but was still significantly lagging behind Europe’s e-commerce leaders (Eurostat, Citation2021). The Covid-19 crisis seems to have significantly accelerated the use of e-commerce in Belgium (Beckers et al., Citation2021) and online shopping rates are expected to remain high even after the pandemic (Roggeveen & Sethuraman, Citation2020). The impact of this evolution on the retail landscape and the difference between types of goods requires further research.

We believe that our analyses and results provide retailers with a new framework for location strategies, helping them find the right position within a new, complex retail geography. Furthermore, a setting has been created for local, regional and national policies to consider this new, complex retail geography, which replaces the traditional hierarchical model. From a traditional monocentric hierarchical system, a regional polycentric retail landscape has emerged; a new geography that certainly requires substantial further research.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (525.9 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Alexander, A., Phillips, S., & Shaw, G. (2008). Retail innovation and shopping practices: Consumers’ reactions to self-service retailing. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 40(9), 2204–2221. https://doi.org/10.1068/a39117

- Barber, M. J., & Scherngell, T. (2013). Is the European R&D network homogeneous? Distinguishing relevant network communities using graph theoretic and spatial interaction modelling approaches. Regional Studies, 47(8), 1283–1298. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.622745

- Basker, E., Klimek, S., & Van, P. H. (2012). Supersize it: The growth of retail chains and the rise of the ‘big-box’ store. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 21(3), 541–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9134.2012.00339.x

- Beckers, J., Cárdenas, I., & Verhetsel, A. (2018). Identifying the geography of online shopping adoption in Belgium. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 45, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.08.006

- Beckers, J., Vanhoof, M., & Verhetsel, A. (2019). Returning the particular: Understanding hierarchies in the Belgian logistics system. Journal of Transport Geography, 76, 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.09.015

- Beckers, J., Weekx, S., Beutels, P., & Verhetsel, A. (2021). COVID-19 and retail: The catalyst for e-commerce in Belgium? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 62, 102645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102645

- Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R., & Lefebvre, E. (2008). Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2008(10), P10008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008

- Blondel, V., Krings, G., & Thomas, I. (2010). Regions and borders of mobile telephony in Belgium and in the Brussels metropolitan zone. Brussels Studies. https://doi.org/10.4000/brussels.806

- Cant, J. (2019). Food inaccessibility in Flanders: Identifying spatial mismatches between retail and residential patterns [Dissertation]. Universiteit Antwerpen.

- Carey, L., Bell, P., Duff, A., Sheridan, M., & Shields, M. (2011). Farmers’ market consumers: A Scottish perspective. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 35(3), 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2010.00940.x

- Christaller, W. (1933). Die zentralen Orte in Süddeutschland. Gustav Fischer.

- Clarke, G., Thompson, C., & Birkin, M. (2015). The emerging geography of e-commerce in British retailing. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2, 371–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2015.1054420

- Crossick, G., & Jaumain, S. (Eds.). (2019). Cathedrals of consumption: The European department store, 1850–1939. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429026249

- Davies, R. L. (Ed.). (1995). Retail planning policies in Western Europe. Routledge.

- Delage, M., Baudet-Michel, S., Fol, S., Buhnik, S., Commenges, H., & Vallée, J. (2020). Retail decline in France’s small and medium-sized cities over four decades. Evidences from a multi-level analysis. Cities, 104, 102790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102790

- Dolega, L., Pavlis, M., & Singleton, A. (2016). Estimating attractiveness, hierarchy and catchment area extents for a national set of retail centre agglomerations. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 28, 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.08.013

- Dyer, S. (2002). Markets in the meadows: Department stores and shopping centers in the decentralization of Philadelphia, 1920–1980. Enterprise and Society, 3(4), 606–612. https://doi.org/10.1093/es/3.4.606

- Elms, J., Canning, C., Kervenoael, R. D., Whysall, P., & Hallsworth, A. (2010). 30 years of retail change: Where (and how) do you shop? International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 38(11/12), 817–827. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551011085920

- Emrich, O., Paul, M., & Rudolph, T. (2015). Shopping benefits of multichannel assortment integration and the moderating role of retailer type Journal of Retailing, 91, 326–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2014.12.003

- Eurostat (2021). Internet purchases by individuals (until 2019). https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/xxvsku3ractkhljecfic4g?locale=en

- Fernandes, J. R., & Chamusca, P. (2014). Urban policies, planning and retail resilience. Cities, 36, 170–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.11.006

- Fernie, J. (1995). The coming of the fourth wave: New forms of retail out-of-town development. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 23(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590559510078061

- Fernie, J. (1998). The breaking of the fourth wave: Recent out-of-town retail developments in Britain. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 8, 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/095939698342797

- Fortunato, S., & Barthélemy, M. (2007). Resolution limit in community detection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(1), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0605965104

- Froy, F. E. (2016). Understanding the spatial organisation of economic activities in early 19th century Antwerp. The Journal of Space Syntax, 6, 225–246. http://joss.bartlett.ucl.ac.uk/journal/index.php/joss/article/view/287

- Goossens, M. (1963). Hiërarchie en hinterlanden der centra; methodologische studie toegepast op noord-oost België. KU Leuven.

- Goossens, M., & Van der Haegen, H. (1972). Atlas van België: commentaar bij de bladen 28 A–B–C: stedennet I–II–III: de invloedssferen der centra en hun activiteitsstructuren. Nationaal comité voor geografie. Commissie voor de nationale atlas.

- Gorczynski, T., & Kooijman, D. (2015). The real estate effects of e-commerce for supermarkets in the Netherlands. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 25, 379–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2015.1034750

- Guimarães, P. (2016). Revisiting retail planning policies in countries of restraint of Western Europe. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 20(3), 361–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2016.1194225

- Guimerà, R., & Nunes Amaral, L. A. (2005). Functional cartography of complex metabolic networks. Nature, 433(7028), 895–900. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03288

- Guy, C. (2007). Planning for retail development a critical view of the British experience. Routledge.

- Guy, C., Bennison, D., & Clarke, R. (2005). Scale economies and superstore retailing: New evidence from the UK. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 12(2), 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2004.03.002

- Guy, C. M. (1998). Controlling new retail spaces: The impress of planning policies in Western Europe. Urban Studies, 35(5–6), 953–979. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098984637

- Hanjoul, P., Beguin, H., & Thill, J.-C. (1989). Advances in the theory of market areas. Geographical Analysis, 21(3), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-4632.1989.tb00888.x

- Herhausen, D., Binder, J., Schoegel, M., & Herrmann, A. (2015). Integrating bricks with clicks: Retailer-level and channel-level outcomes of online–offline channel integration. Journal of Retailing, 91, 309–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2014.12.009

- Hernández, T., & Bennison, D. (2000). The art and science of retail location decisions. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 28(8), 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550010337391

- Hood, N., Clarke, G., & Clarke, M. (2016). Segmenting the growing UK convenience store market for retail location planning. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 26, 113–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2015.1086403

- IDEA Consult, MAS Research, GeoIntelligence. (2014). Interprovinciale studie detailhandel.

- Jacques, T. (2018). The state, small shops and hypermarkets: A public policy for retail, France, 1945–1973. Business History. 60(7), 1026–1048. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2017.1413092

- Jones, P., Comfort, D., & Hillier, D. (2017). A commentary on pop up shops in the UK. Property Management, 35, 545–553. https://doi.org/10.1108/PM-10-2016-0055

- Jones, P., Comfort, D., & Hillier, D. (2018). Surveying the pop-up scene. Geography, 103(1), 50–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167487.2018.12094036

- Kellerman, A. (1985). The suburbanization of retail trade: A U.S. Nationwide view. Geoforum, 16(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7185(85)90003-X

- Kirby-Hawkins, E., Birkin, M., & Clarke, G. (2019). An investigation into the geography of corporate e-commerce sales in the UK grocery market. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 46(6), 1148–1164. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399808318755147

- Korthals Altes, W. K. (2016). Freedom of establishment versus retail planning: The European Case. European Planning Studies, 24(1), 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1029441

- Kropp, P., & Schwengler, B. (2016). Three-step method for delineating functional labour market regions. Regional Studies, 50(3), 429–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.923093

- Lancichinetti, A., & Fortunato, S. (2009). Community detection algorithms: A comparative analysis. Physical Review E, 80(5), 056117. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.80.056117

- Lancichinetti, A., & Fortunato, S. (2011). Limits of modularity maximization in community detection. Physical Review E, 84(6), 066122. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.84.066122

- Lesger, C. (2007). De locatie van het Amsterdamse winkelbedrijf in de achttiende eeuw. Tijdschrift voor Sociale en Economische Geschiedenis/The Low Countries Journal of Social and Economic History, 4, 35–70. https://doi.org/10.18352/tseg.628

- Lesger, C. (2011). Patterns of retail location and urban form in Amsterdam in the mid-eighteenth century. Urban History, 38(1), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926811000022

- Lloyd, A., & Cheshire, J. (2017). Deriving retail centre locations and catchments from geo-tagged Twitter data. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 61, 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2016.09.006

- Lord, J. D., & Guy, C. M. (1991). Comparative retail structure of British and American cities: Cardiff (UK) and Charlotte (USA). The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 1, 391–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969100000001

- Lovelace, R., Birkin, M., Cross, P., & Clarke, M. (2016). From big noise to big data: Toward the verification of large data sets for understanding regional retail flows. Geographical Analysis, 48(1), 59–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/gean.12081

- Lowe, M. (2005). The regional shopping centre in the inner city: A study of retail-led urban regeneration. Urban Studies, 42(3), 449–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500035139

- Martinus, K., & Sigler, T. J. (2017). Global city clusters: Theorizing spatial and non-spatial proximity in inter-urban firm networks. Regional Studies, 52, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1314457

- McArthur, E. (2013). The role of department stores in the evolution of marketing: Primary source records from Australia. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 5, 449–470. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHRM-11-2013-008

- McEachern, M. G., Warnaby, G., Carrigan, M., & Szmigin, I. (2010). Thinking locally, acting locally? Conscious consumers and farmers’ markets. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(5–6), 395–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/02672570903512494

- Nayga, Jr., R. M., & Weinberg, Z. (1999). Supermarket access in the inner cities. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 6(3), 141–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-6989(98)00029-0

- Nelson, G. D., & Rae, A. (2016). An economic geography of the United States: From commutes to megaregions. PLOS ONE, 11, e0166083. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166083

- Newing, A., Clarke, G. P., & Clarke, M. (2015). Developing and applying a disaggregated retail location model with extended retail demand estimations. Geographical Analysis, 47(3), 219–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/gean.12052

- Newman, M. E. J., & Girvan, M. (2004). Finding and evaluating community structure in networks. Physical Review E, 69(2), 026113. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.69.026113

- Osaba, E., Del Ser, J., Camacho, D., Bilbao, M. N., & Yang, X.-S. (2020). Community detection in networks using bio-inspired optimization: Latest developments, new results and perspectives with a selection of recent meta-heuristics. Applied Soft Computing, 87, 106010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2019.106010

- Péron, R. (2001). The political management of change in urban retailing. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 25(4), 847–878. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00347

- Reutterer, T., & Teller, C. (2009). Store format choice and shopping trip types. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 37(8), 695–710. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550910966196

- Reynolds, J., & Wood, S. (2010). Location decision making in retail firms: Evolution and challenge. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 38(11/12), 828–845. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551011085939

- Roggeveen, A. L., & Sethuraman, R. (2020). How the COVID-19 pandemic may change the world of retailing. Journal of Retailing, 96(2), 169–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2020.04.002

- Schiller, R. (1986). Retail decentralisation: The coming of the third wave. The Planner, 72, 13–15.

- Siła-Nowicka, K., & Fotheringham, A. S. (2019). Calibrating spatial interaction models from GPS tracking data: An example of retail behaviour. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 74, 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2018.10.005

- Singleton, A. D., Dolega, L., Riddlesden, D., & Longley, P. A. (2016). Measuring the spatial vulnerability of retail centres to online consumption through a framework of e-resilience. Geoforum, 69, 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.11.013

- Thomas, C. J., & Bromley, R. D. F. (2003). Retail revitalization and small town centres: The contribution of shopping linkages. Applied Geography, 23(1), 47–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0143-6228(02)00068-1

- Thomas, I., Adam, A., & Verhetsel, A. (2017). Migration and commuting interactions fields: A new geography with community detection algorithm? Belgeo, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.4000/belgeo.20507

- Traag, V. A., Waltman, L., & van Eck, N. J. (2019). From Louvain to Leiden: Guaranteeing well-connected communities. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 5233. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41695-z

- Traag, V., Zanini, F., Gibson, R., Ben-Kiki, O., & van Kuppevelt, D. (2020). Leidenalg: A python package for community detection. Zenodo, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4047113

- Tranos, E., Gheasi, M., & Nijkamp, P. (2015). International migration: A global complex network. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 42(1), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1068/b39042

- Van Damme, I., & Van Aert, L. (2014). Antwerp goes shopping! continuity and change in retail space and shopping integrations from the 16th to the 19th century. In J. H. Furnée, & C. Lesger (Eds.), The landscape of consumption: Shopping streets and cultures in Western Europe (pp. 1600–1900). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van den Eeckhout, P. (2012). Shopping for food in Western Europe in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Food and History, 10(1), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.FOOD.1.102960

- Van der Haegen, H., Cardyn, C., & Pattyn, M. (1982). The Belgian settlement system, acta geographica Lovaniensia. KUL Geografisch Instituut.

- van Gameren, V., Ruwet, C., & Bauler, T. (2015). Towards a governance of sustainable consumption transitions: How institutional factors influence emerging local food systems in Belgium. Local Environment, 20(8), 874–891. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.872090

- Van Hecke, E. (1998). Actualisation de la hiérarchie urbaine de Belgique. Bulletin trimestriel du Crédit Communal, 52, 45–76.

- van Leeuwen, E. S., & Rietveld, P. (2011). Spatial consumer behaviour in small and medium-sized towns. Regional Studies, 45(8), 1107–1119. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343401003713407

- van Meeteren, M., & Poorthuis, A. (2018). Christaller and ‘big data’: recalibrating central place theory via the geoweb. Urban Geography, 39(1), 122–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1298017

- Verhetsel, A., Beckers, J., & De Meyere, M. (2018). Assessing daily urban systems: A heterogeneous commuting network approach. Networks and Spatial Economics, 18(3), 633–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11067-018-9425-y

- Verhetsel, A., Thomas, I., & Beelen, M. (2010). Commuting in Belgian metropolitan areas: The power of the Alonso–Muth model. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 2(3), 109–131. https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.v2i3.19

- Verhoef, P. C., Kannan, P. K., & Inman, J. J. (2015). From multi-channel retailing to omni-channel retailing: Introduction to the special issue on multi-channel retailing. Journal of Retailing, 91, 174–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2015.02.005

- Waddington, T. B. P., Clarke, G. P., Clarke, M., & Newing, A. (2018). Open all hours: Spatiotemporal fluctuations in U.K. grocery store sales and catchment area demand. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 28, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2017.1333966

- Wood, S., & Browne, S. (2007). Convenience store location planning and forecasting – a practical research agenda. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 35(4), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550710736184

- Wood, S., & McCarthy, D. (2014). The UK food retail ‘race for space’ and market saturation: A contemporary review. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 24, 121–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2013.839465

- Wrigley, N., Lambiri, D., Astbury, G., Dolega, L., Hart, C., Reeves, C., Thurstain-Goodwin, M., & Wood, S. (2015). British high streets: From crisis to recovery? A comprehensive review of the evidence. ESRC.

- Yang, Z., Algesheimer, R., & Tessone, C. J. (2016). A comparative analysis of community detection algorithms on artificial networks. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 30750. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30750

- Zhang, J., Farris, P.W., Irvin, J.W., Kushwaha, T., Steenburgh, T.J., & Weitz, B.A. (2010). Crafting integrated multichannel retailing strategies. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 24(2), 168–180. Special Issue on ‘Emerging Perspectives on Marketing in a Multichannel and Multimedia Retailing Environment’. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2010.02.002

- Zhang, W., Derudder, B., Wang, J., & Shen, W. (2018). Regionalization in the Yangtze River Delta, China, from the perspective of inter-city daily mobility. Regional Studies, 52(4), 528–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1334878