?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

We investigate whether bank loans specifically designed to reduce credit constraints for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have different impacts depending on where the firm is located. Using detailed firm-level data from the state-owned Swedish bank Almi, which specifically lends to credit-constrained SMEs, and coarsened exact matching and difference-in-difference regressions, we study the causal effects of small business loans on firm growth. The results show that receiving a loan has a greater impact on firm growth for those SMEs located in major cities than for firms located in remote rural regions. This result has implications for policies that aim to increase growth in rural regions and suggests that increasing access to credit alone is not sufficient to increase employment growth.

INTRODUCTION

Among both scholars and policymakers there is a significant and growing interest in how firms, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), can obtain sufficient funding.Footnote1 SMEs are generally viewed as vital for economic growth, for both creating new jobs and innovation (Aghion & Howitt, Citation1992; Haltiwanger et al., Citation2013; Soete & Stephan, Citation2004). At the same time, SMEs are often presumed to suffer from credit constraints because they do not possess sufficient collateral or large cash flows. Young SMEs competing for credit with more mature firms also suffer from not having an established credit history, which exacerbates the problem of asymmetric information, making it even more difficult to obtain external financing. Furthermore, SMEs do not have the same access to bond or equity markets as larger corporations (Aghion et al., Citation2007; Rajan & Zingales, Citation1998). The existence and overall importance of funding constraints for SMEs has been the subject of a great deal of recent research (Brown & Earle, Citation2017; Franklin et al., Citation2019; Hasan et al., Citation2019; Kaya & Masetti, Citation2019).

The question of whether the credit constraints of firms vary over regions, and if additional loans have different effects on the real growth of firms depending on their location, has not received as much attention in previous studies. According to simple textbook theory, if credit markets are perfect and without frictions, all positive net present value projects will receive funding. However, there are several reasons why access to credit could be more difficult for firms in rural regions than for those in urban regions, resulting in significant effects for local economic conditions (Dow & Rodriguez-Fuentes, Citation1997; Klagge & Martin, Citation2005; Ughetto et al., Citation2019). Small firms rely on local bank offices to a greater extent than larger firms; therefore, when banks close local branch offices (often because of advances in information technology – IT), credit constraints for SMEs might become aggravated (Kärnä et al., Citation2021; Nguyen, Citation2019). Urban areas offer greater access to bank offices, increasing the possibility of relationship banking and decreasing asymmetric information, as well as access to other sources of funding such as venture capital. This paper studies how the real growth effects of bank loans that are specially targeted towards credit constrained SMEs varies depending on if the firm is located in an urban area or rural region.

Extending SMEs’ access to credit by using (indirectly) subsidized credit could therefore provide benefits if credit markets are imperfect. Using detailed data on loans from the US Small Business Administration (SBA), Brown and Earle (Citation2017) find significant positive growth effects in terms of the number of employees. It is, however, not known if these positive effects vary between the regions in which the firms are located. From a policy perspective, a fine-tuned understanding of the regional differences in marginal effects of credit is critical in designing policies related to reducing the credit constraints of SMEs.

The contribution of this paper to the literature is twofold. First, we provide explanatory evidence about firm characteristics that increase the likelihood of obtaining a small business loan from a state-owned Swedish bank whose purpose is to reduce credit constraints for SMEs. Second, we estimate the causal treatment effects from those loans on firm growth and analyse whether these effects are conditional on the firm's location, a question rarely addressed in previous studies. We find significant effects of additional credit on firm growth, both economically and statistically. However, our results show that the significance of the effects depend on if the firm is located in an urban area or rural region.

Sweden provides an excellent testbed for studying the effects of small business loans on SME growth for several reasons. First, the state-owned Swedish bank Almi provides small business loans to credit-constrained firms, but rather than offering subsidized bank loans to firms, Almi charges higher interest rates than commercial banks. This is different than many countries where state-owned banks provide subsidized loans with lower interest rates to SMEs and start-ups. The reason that Almi established this interest rate policy was to avoid competing with commercial banks. The second reason is that even though Sweden is a relatively small country, there are both densely populated large metropolitan areas as well as remote rural regions distant from major cities. This provides an ideal environment for testing the effect of remoteness and lack of local financial services on SME credit constraints and on the growth effects for SMEs when credit constraints are relaxed. Third, Sweden is a high-income country with stable institutions, which decreases the risk that we might capture local credit supply inefficiencies caused by policy failures. The detailed loan information from Almi in combination with register data creates a perfect overlap for all the Swedish firms in our sample. Almi specifically lends to credit-constrained SMEs, often in collaboration with commercial banks. The rich dataset covers the entire country between 2000 and 2016 and includes public and private firms, as well as established firms and start-ups. This comprehensive dataset provides an excellent testing ground for investigating the regional dimension of credit constraints and the effects of small business loans.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section summarizes the literature on the regional variation of credit constraints. The third section provides some background on public loans and the state-owned bank Almi. The fourth section describes the empirical strategy, data and results. The fifth section concludes.

SPATIAL VARIATION IN ACCESS TO BANK CREDIT AND ITS EFFECT ON FIRMS

The literature regarding credit constraints for SMEs is both large and heterogeneous. Due to asymmetric information, it is not obvious that credit markets should work perfectly. Therefore, banks and other creditors will ration credit rather than increase the interest rate to a market clearing level (Akerlof, Citation1970; de Meza & Webb, Citation2000; Stiglitz & Weiss, Citation1981). As mentioned above, because young SMEs often do not have as well-developed a credit history as larger, more established firms, asymmetric information issues tend to plague SMEs more than older firms that have established relationships with their creditor (Beck & Demirgüç-Kunt, Citation2006; Kirschenmann, Citation2016). Furthermore, some SMEs might lack sufficient collateral (especially firms in the service sector), and they often depend on bank loans since they are unable to access bond or equity markets (Brown et al., Citation2019). While studies on venture capital often find significant positive effects on firm growth (Gompers & Lerner, Citation2001; Kaplan & Strömberg, Citation2001; Schäfer et al., Citation2004), only a limited number of high-potential firms receive venture capital. Many firms also avoid venture capital since it forces them to relinquish control of the firm, especially if the goal of the owner is not growth maximization, but rather non-monetary rewards earned from entrepreneurship (Bornhäll et al., Citation2016; Hurst & Pugsley, Citation2011).

Observing funding gaps empirically is difficult since it involves the counterfactual question of how firms would develop if they had access to sufficient amounts of capital. As empirical studies rarely have information on the (expected) return from an investment opportunity, it is difficult to know why the firm did not choose, for example, to invest in a new piece of machinery. Without knowing whether there are profitable opportunities for a firm, it is impossible to determine if low investment is due to insufficient credit or lack of possibilities. This makes an empirical assessment of credit constraints difficult to perform and might also explain the lack of consensus in the literature.

The ability of a firm to borrow, and the amount of credit granted to a firm depends, among other factors, on firm characteristics. In spite of an extensive discussion about how cash flows influence credit constraints, there is a lack of consensus (Fazzari et al., Citation1988, Citation2000; Kaplan & Zingales, Citation1997, Citation2000). Indeed, it is difficult to find variables that are well correlated with credit constraints for large public firms (Farre-Mensa & Ljungqvist, Citation2016). For SMEs, the literature suggest that older and larger firms are likely to be less credit constrained (Beck et al., Citation2006; Hyytinen & Pajarinen, Citation2008).

SMEs often engage in relationship banking to reduce asymmetric information between the firm and the bank (Berger & Udell, Citation2002). This increases trust and lowers the asymmetric information that is prevalent in a borrower–lender situation. Since this requires the firm to visit their bank in order to discuss their projects, a firm located far from a bank might have less access to finance than a firm located nearby (Granja et al., Citation2018; Lee & Brown, Citation2017; Nguyen, Citation2019). Not only will transportation costs be higher, but also the bank might have less information regarding the quality of the entrepreneur, local business opportunities, the regional supply of labour, etc., which in turn suggests that firms in more peripheral regions should be more credit constrained than those in urban areas.Footnote2 Furthermore, if a local bank has market power, then it can use this market power to decrease the amount of lending in order to increase its profits (Canales & Nanda, Citation2012; Ryan et al., Citation2014).Footnote3 A firm located far from a bank's headquarters, but close to a branch, might still have less access to credit than a firm located closer to the bank's headquarters (Conroy et al., Citation2017; Zhao & Jones-Evans, Citation2017).

Many banks have introduced credit scoring to determine the creditworthiness of SMEs. While this might decrease the relevance of relationship banking, some studies find that the introduction of credit scoring is associated with an increase in SME lending (Berger et al., Citation2005a; DeYoung et al., Citation2008). Larger banks (measured by total assets) seem to rely less on relationship banking and do little to relieve SMEs’ credit constraints; this is a contrast to smaller banks (Berger et al., Citation2005b; Stein, Citation2002).

A complication that arises when identifying the effects of bank loans on firm growth is that urban areas tend to have higher growth rates than less densely populated regions (Glaeser et al., Citation1992; Glaeser & Mare, Citation2001; Stephan, Citation2011). This result creates a confounding problem since lower firm growth in less densely populated areas might be due to either funding gaps or the lack of growth opportunities, or both (Lee & Drever, Citation2014). Put differently, the more efficient the credit markets are for SMEs, the less important firm location should be for obtaining loans (Klagge et al., Citation2017; Klagge & Martin, Citation2005).

When credit markets are less efficient and the frictions created by asymmetric information are more intense, the more important the spatial component may become. An investigation of the regional effects of bank loans can therefore be viewed as an indirect test of the efficiency of credit markets. If there is no evidence of regional differences in the effects of public bank loans on firm growth, this could be an indication that local knowledge is not overly important for credit allocation. The exact extent of how important geographical location is in the finance literature still debated, with, for example, Petersen and Rajan (Citation2002) and Carling and Lundberg (Citation2005) arguing that it is of limited importance, while, for example, Klagge and Martin (Citation2005) and Bellucci et al. (Citation2013) argue that it is of significant importance. Regional differences could, of course, be measured in terms of both a loan's quantity and/or price; for example, Cowling et al. (Citation2020) find that a firm's location causes greater variations in price rather than quantity.

From the literature, we can identify three different hypotheses regarding bank loans, geography and SMEs. Hypothesis (1) suggests that if the credit market works less well in rural areas and firms are more credit constrained, additional credit should lead to larger positive effects in rural areas. Hypothesis (2) suggests that urban firms should, due to agglomeration effects and positive externalities, respond more positively to obtaining additional credit. Hypothesis (3) suggests that if credit markets are efficient, the effects of additional credit on firms should be the same regardless of firm location. The lack of theoretical consensus regarding the regional variation of the growth effects from obtaining credit provides the rationale for this empirical study.

SMALL BUSINESS LOANS FOR SMEs IN SWEDEN

As in most other developed countries, banking sector employment relative to other sectors has declined in Sweden (see Table A1 in the supplemental data online) from 0.96% in 2002 to 0.81% in 2015. The variation across region types is also worth noting. While the share of commercial bank employees is approximately 1.4% in major cities, it is below 0.4% in remote rural areas. This discrepancy hints at the notion that it might be difficult for firms located in remote rural regions to obtain a bank loan, especially if relationship banking still matters. In a recent paper using Swedish data, the reduction in regional bank offices seems to reduce the scope for relationship banking and increase perceived financial constraints, which is hypothesized to have negative effects on the possibility of SMEs obtaining loans (Backman & Wallin, Citation2018).

Again, as in many other countries, Sweden also has an extensive, though somewhat fragmented, system to promote SMEs and reduce their credit constraints (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2016). This includes direct grants to firms, access to governmental venture capital and direct bank loans via the state-owned bank, Almi. Almi's goal is to complement the commercial bank market by lending directly to SMEs. More specifically, loans from Almi are supposed to complement loans from commercial banks by lending with less strict collateral requirements, thereby enabling those firms to have access to debt finance. Almi charges a higher interest rate than commercial banks and can, therefore, be viewed as a provider of the uncollateralized ‘high risk part’ of business loans.

The argument for the existence of this type of support is that commercial banks are reluctant to give loans to SMEs because of the high risk and high fixed costs involved in providing this financial service for relatively small loans. While expensive, these loans are indirectly subsidized since Almi is not able to sustain its operations without direct support from the public. Since Almi has 40 offices spread throughout Sweden and lends to firms that are located in all municipalities, we have sufficient data to estimate the treatment effect depending on the location of the treated firm, something that, to the best of our knowledge, previous studies have not been able to do.

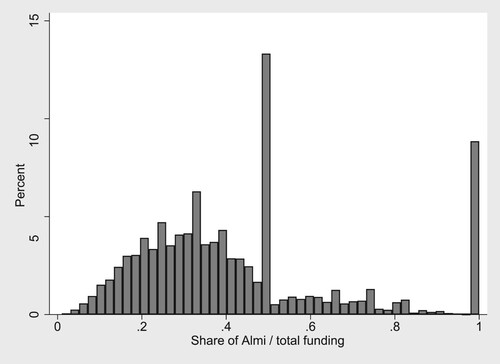

Most of the time, but not always, the firm that borrows from Almi also has a joint commercial loan (the share of commercial to Almi loans is plotted in ). The most common procedure for obtaining a bank loan from Almi is that a firm first asks its commercial bank for a loan. If, after due diligence, the bank rejects the firm's initial loan application, the bank can suggest that the firm applies to Almi for a supplemental loan. This suggestion comes with the understanding that if Almi accepts the application and provides financing to the firm, the bank will then follow suit. Given this scenario, the commercial bank will supply the majority or half share of the financing with a minority or half share coming from Almi (). The commercial loan has a lower interest rate, but comes with stricter bankruptcy rules. The loan from Almi is intentionally more expensive to avoid the possibility of competing with commercial banks.Footnote4 Almi's loan can also be viewed as a form of junior debt and is less stringent on bankruptcy rules. In certain cases, especially for new firms borrowing small amounts of money, the firm can rely on Almi for the entire loan amount. The primary objective of these loans is to facilitate capital investments, such as real estate (for warehouses, factories, etc.) or machinery (Institutet för Tillväxtpolitiska Studier (ITPS), Citation2002; Kärnä, Citation2020).

Figure 1. Distribution of Almi’s share in total funding.

Note: A share of 1 indicates that a firm received only funding from an Almi loan. A value close to 0 indicates that Almi's contribution was small compared with that of a commercial bank and/or internal financing.

Table 1. Summary statistics of firms with a loan from Almi.

While publicly sponsored bank loans are found in other countries, these loans tend to be credit guarantees to private banks rather than direct loans from public banks. For example, the United States has a variety of schemes to increase credit for SMEs (Brown & Earle, Citation2017; Cortés & Lerner, Citation2013), and in Germany, the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) plays a similar role (Lehmann et al., Citation2004). Likewise, in the UK, the Small Firms Loan Guarantee Scheme promotes access to debt finance for small credit-constrained firms (Cowling, Citation2010). Almi's role in Sweden is more direct and pervasive, with the complementary role of providing guidance to firms, even firms that have not received an Almi loan.

The spatial distribution of Almi's 40 branches across all Swedish regions is not a coincidence, but an essential and intentional part of its design to ensure that it fulfils its mission to provide access to funding to all regions in Sweden. This allows us to analyse Almi's lending to firms located in both urban and rural areas. Almi uses the same lending guidelines regardless of firm location, implying that firms eligible for public loans should be similar across locations. It should be noted that since more firms are located in or near major cities, more loans are granted to firms in these regions (the distribution of loans per region type is plotted in Figure A2 in the supplemental data online).

Our register data includes all Swedish firms, both public and private. We are able to match Almi's loan to each firm using the unique firm identification number assigned to all Swedish firms. While Almi does keep track of all their lending decisions, which creates the dataset for this paper, they do not keep a record of firms that applied for a loan from Almi but were rejected. Therefore, we cannot use a regression discontinuity design in our empirical analysis, since we do not know which firms were rejected. Instead, we use the double robust method of matching and difference-in-difference (DiD) described below. In our empirical estimations, it is possible that firms included in the group of firms that were rejected will be included in the control group. This could lead to a pooling bias, since firms that were rejected by Almi are different from firms that never applied for an Almi loan in the first place. However, we do not believe this is a significant issue in practice, as will be discussed below.

EMPIRICAL STRATEGY, DATA AND RESULTS

Matching the data from Almi provided by The Swedish Agency for Growth Policy AnalysisFootnote5 with register employer–employee data from Statistics Sweden (SCB) creates a panel of all firms in Sweden.Footnote6 This panel covers Almi loans for the period 2000–16Footnote7 and firm register data for 1997–2016, allowing us to observe a firm that receives its loan in 2000 for three years prior to the loan and 16 years after the granting of the loan. A firm that receives its loan in 2010 can be observed for six years over the post-treatment period. Most of the firms are not listed on any stock exchange, which increases the likelihood that they are facing funding constraints and makes them more relevant for our analysis (Saunders & Steffen, Citation2011).

MATCHING METHODOLOGY

We use matching and DiD regressions to reduce selection bias between treated and non-treated firms, a method used in other research to analyse SME financing effects (Heckman et al., Citation1997, Citation1998; Ho et al., Citation2007). Saunders and Steffen (Citation2011) and Brown and Earle (Citation2017) use propensity score matching (PSM) to reduce selection bias in their empirical study of SBA loans in the United States. We decided to use coarsened exact matching (CEM) to match firms that receive a loan from Almi with similar firms that did not receive a loan (Iacus et al., Citation2011, Citation2012). CEM is a matching method that uses all the moment conditions of a variable and then coarsens the variable into bins. This method is an improvement over PSM (King & Nielsen, Citation2016). Because of these benefits, CEM is used in applied economic research to reduce bias from non-randomized interventions in fields such as labour economics (Blázquez et al., Citation2019), agricultural economics (Nilsson, Citation2017) and innovation economics (Azoulay et al., Citation2010, Citation2019). Firms are then matched in these bins for all the chosen variables. Bin sizes can be set either manually or by using a default algorithm (Blackwell et al., Citation2009). When matching for categorical variables, such as an industry code, we use exact matching rather than coarsening the variable to ensure that the treated firms are as similar as possible to the control group. Due to the large sample size, we use one-to-one matching so that each treated firm is assigned one similar control firm.

It is advisable to match firms the year before they receive their treatment. Therefore, firms receiving a loan from Almi are matched with non-treated firms one year before they receive their loan. The matching is based on the number of employees, debt to capital stock (in log), sales growth, the two-digit industry code and municipality spatial type. After matching, there is a decrease in the mean imbalance value, indicating that the control group has become more similar to the treated group after matching. For full matching statistics, see Tables A2 and A3, and Figure A3 in the supplemental data online.

A description of variables used in the analysis is provided in . The summary statistics for the firms that received a loan from Almi, as well as the matched control group, can be found in . The data on firm age may be slightly skewed because the founding year of a firm is only available beginning in 1986 and our panel data ends in 2016. Hence, the oldest firms in are only 30 years old, although some may be older.Footnote8

Table 2. Control and dependent variables.

Table 3. Summary statistics after matching.

REGIONAL VARIATION IN LENDING

To investigate regional differences in the effects of public loans, we apply a classification developed by the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (SAERG) that divides all Sweden's 290 municipalities into six different spatial categories. The classification's primary criterion is spatial density, with six municipality spatial types ranging in descending density order from ‘major cities’ to ‘countryside municipalities very far from a major city’. Since there are relatively few observations available in the sixth category (the most remote rural municipalities), we merge those observations with the ones in the fifth category. For a full description of the methodology that defines the different spatial categories of municipalities, see . The number of commercial banks per spatial category, and the change during the time period covered in our panel, is presented in Table A1 in the supplemental data online.

Table 4. Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (SAERG) definition of spatial density types.

We begin our analysis by examining those firms that borrow from Almi and those that default on their Almi loan.Footnote9 As already mentioned, Almi loans are expensive for borrowers, so we assume that only firms that cannot obtain funding from an alternative source will seek an Almi loan. This assumption enables us to identify the specific characteristics of a firm that are related to being credit constraint. This approach also allows us to obtain estimates on how financial constraints vary between the various firm locations. The regression results are shown in .

Table 5. Probit regressions on the determinants (marginal effects) of borrowing and defaulting on an Almi loan.

The results imply that firms with Almi loans are characterized by higher debt levels, lower labour productivity and a lower capital stock than the matched control firms. This is a plausible finding and confirms the assumption that firms that seek Almi loans are financially constrained and have no other access to credit. Relative to firms located in major cities, the probability of borrowing from Almi is significantly higher in all other locations and appears to be increasing with decreasing population density. Firms in remote rural areas – a countryside municipality far from a major city (CFMC) and a countryside municipality very far from a major city (CVFMC) in – are approximately 7% more likely to need an Almi loan, whereas firms in dense municipalities close to a major cities (DCMC) are approximately 3% more likely to use Almi as a source of funding. This result implies that firms outside of cities are more credit constrained, in line with the theoretical discussion on regional credit constraints in the second section. The most constrained firms are located in regions distant from major cities.

We find surprisingly few regional differences in the likelihood of defaulting on the loan; only firms located in remote rural areas are significantly more likely to default than firms in major cities. This may also explain why the interest rate for those firms is on average higher than that for firms located in other regions. We also examine whether firm-specific variables determine loan size, interest rates and Almi's loan share compared with the commercial bank. The results in show that a higher capital stock decreases the size of Almi's loan and interest rate, and increases the share of the loan from commercial banks. A similar result is found for labour productivity, but exactly the opposite for debt levels. This is an intuitive result in the sense that firms relying on loans from Almi and with larger Almi loan shares are more likely to be riskier and more credit constrained, and must accept the higher interest rates required by Almi loans.Footnote10

Table 6. Fixed effects panel regressions on the determinants of the loan size, Almi's share and loan's interest rate.

SPATIAL VARIATION OF REAL EFFECTS FROM OBTAINING A SMALL BUSINESS LOAN

To implement the DiD approach, we run the following fixed effects ordinary least squares (OLS) regression for all outcome variables:

(1)

(1) where α0 is a constant; Xit is the vector of control variables described in ; θit is the post-treatment dummy interacted with the municipality spatial type; ηi and δi are firm fixed effects; τt denotes year dummies; γik denotes industry dummies; and εit denotes an error term. The firm-specific fixed effects account for all systematic time-invariant differences between the control and the treatment group. In the few cases where a firm receives multiple loans from Almi, the first loan observation is used to create the treatment dummy. The post-treatment dummy measures the treatment effect from the time the firm receives their first loan until the panel ends.

Unlike most papers that simply control for and eliminate the region-type effects, this paper follows Tingvall and Videnord (Citation2020) in analysing the treatment effects conditional on firm location and regional characteristics. To avoid post-treatment bias, we use a minimum number of control variables in the regressions (King, Citation2010). For example, controlling for a firm's capital stock in the post-treatment analysis might be problematic since one of the goals of the loan is to increase the capital stock. Therefore, we only control for the share of high-skilled employees, firm age, number of employees and number of employees squared, in addition to the post-treatment dummies that are interacted with the region type.

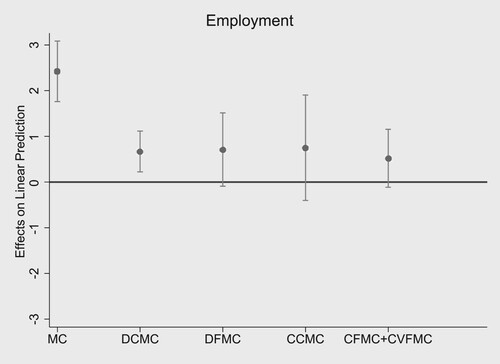

The regression results in show that the effect of bank loans on employment is greater in major cities than in other regions. On average, a firm in a major city that receives an Almi loan will have 2.5 more employees in subsequent years, while the effect on employment in other region types is significantly lower. It is important to note that the post-treatment dummy in represents the treatment effect on firms in major cities. In fact, these effects from Almi loans are only positive and significant in major cities and in municipalities located close to major cities. The marginal effects for employment are also plotted in .

Figure 2. Effect of Almi loan on the number of employees for firms interacted with region type.

Note: Marginal effects from fixed effects regression using matched sample (see ). Points show regression results with 95% confidence intervals. MC, major city (reference category); DCMC, dense municipality close to a major city; DFMC, dense municipality far from a major city; CCMC, countryside municipality close to a major city; CFMC, countryside municipality far from a major city; and CVFMC, countryside municipality very far from a major city.

Table 7. Fixed effects panel regressions (difference-in-difference – DiD) on the real growth effects of Almi's small business loans.

The interaction effect results for the post-treatment dummy show the difference of the treatment effect in the respective region relative to the treatment effect in major cities. These results are in line with results from urban economics literature that suggest that urban areas provide locational advantages to firms. Specifically, firms in major cities (or close to them) generally have better growth opportunities. Thus, once these firms obtain the loans and use the needed funds, they experience higher levels of firm growth (Hottenrott & Peters, Citation2012; Schäfer et al., Citation2017). These findings do, however, conflict with the reasoning of regional credit constraint literature that postulates that the effects from additional funds are stronger for firms in remote regions. The basis for this reasoning is if firms in peripheral regions are on average more credit constrained, it could be expected that the effect of an Almi loan should be greater, rather than smaller, in remote regions.

ANALYSIS AND ROBUSTNESS CHECKS

One explanation for the results could rest on the fact that Almi's mission is to provide loans to firms all over Sweden, and to fulfil this mission Almi must provide loans to less promising projects. Hence, the larger effect of Almi loans regarding employment for firms located in major cities might be a consequence of its mission. If Almi's mission were to fund mainly the most promising projects, our results suggest that they should mainly give loans to firms located in major cities.

The effect of an Almi loan on sales growth is positive and significant for firms in major cities. On average, firms in major cities have 18% higher sales in the years following the loan. Firms in other region types are also able to expand their sales after receiving the loan, though significantly less than firms in major cities. The same pattern holds for the dependent variables: productivity, total factor productivity (TFP) and capital stock. Thus, when taken together, the treatment effect regressions show that the effects from receiving a bank loan on firm growth are stronger in major cities than in other region types. As mentioned above, one explanation of this finding is that firms in major cities have better growth opportunities than firms in other locations, and when credit constraints are relaxed for these firms, they experience better performance in terms of sales, productivity and employment, on average. This contradicts the hypothesis that when the constraints are relaxed for credit-constrained firms in remote regions, the differences in firm growth between urban and remote firms would disappear.

It should be noted that Almi loans also have a positive impact on the performance of targeted firms in rural regions, and the differences in the magnitude of the impact conditional on firm location are in some cases relatively small. Coefficients of interaction terms that are not significant indicate that differences to the base category of major cities are not statistically significant. One tentative conclusion, therefore, is that granting small business loans do mitigate regional differences in access to credit to some extent (Petersen & Rajan, Citation2002).

We performed a number of robustness tests to determine whether the results are robust to variations in methodology, which are reported in Tables A4–A9 in the supplemental data online. Since the results could vary between firm sizes, we split the sample and reran the regressions for firms with more than 10 employees and for firms with 10 or fewer employees. The results remain largely unaffected, with positive effects in major cities and lower effects in every other municipality type. To ensure the results are not driven by outliers, we also trim the outcome variables at a 5% level and repeat the regressions; again, our results are robust to this specification. Some firms in our sample only receive a loan from Almi and not a complementary commercial bank loan. Excluding those firms, the results remain positive, although with a lower treatment effect for firms in major cities and in all other municipality spatial types.Footnote11

This study does not consider regional spillover effects that may extend from firms with loans to firms that did not receive a loan. A recent US study does not find spillover effects from SBA lending (Lee, Citation2018), suggesting that these effects might be negligible. We also do not study how receiving a loan affects the survival of firms, although this question is of major interest in the context of public loans. The main reason for this omission is that our data quality does not allow us to study firm exit since we are unable to determine the reason for the exit (e.g., did the firm exit due to voluntary closure or a bankruptcy). However, in an attempt to shed some light on this issue, we plot Kaplan–Meier survival and hazard rates (see Figures A4 and A5 in the supplemental data online).

CONCLUSIONS

This study uses a unique and detailed firm loan dataset to analyse the selection into and the effect of public loans to SMEs that are credit constrained, with a special focus on the regional variation of these effects. Firms that borrow from the Swedish state-owned bank Almi are in general characterized by being more credit constrained than their peers, as indicated by higher debt levels, lower labour productivity and less equity capital than the matched control group. Furthermore, these firms are more likely to be located outside of urban areas.

Small business loans to firms located in remote rural regions are also riskier and more prone to default, justifying Almi's higher interest rate. Our results support previous research on a spatial dimension of credit constraints in general, and in particular the results show that firms farther from major cities are more credit constrained than firms close to urban areas. Interestingly, even if present-day financial services are more IT based and should depend less on the physical presence of a nearby bank branch, our results imply that SMEs in remote regions are still more credit constrained.

To provide a causal interpretation of the impact of small business loans on firm growth, we combine matching techniques and DiD regressions. Contrary to our expectations, the treatment effect regressions suggest that the real effects from receiving a bank loan on firm growth and productivity are stronger in major cities than in more rural regions. One interpretation of this finding is that firms in major cities have better growth opportunities than firms in other locations. Thus, when credit constraints are relaxed, these firms experience better performance in terms of sales, employment and productivity, on average.

There is an ongoing political debate about how to increase the economic growth of rural and underdeveloped areas (Austin et al., Citation2018). The results of our study show that the growth effects generated by obtaining a small business loan would be higher for SMEs located in major cities. This suggests that policy designed to support SMEs in remote regions by providing small business loans might have lower effects than anticipated. This should be considered by policymakers when designing and funding programmes to improve the economic performance of remote regions. A simple relaxation of credit constraints is not sufficient.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (560.6 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Bo Becker, Alice Hallman, Aleksandar Petreski, Patrik Gustavsson Tingvall, Josefin Videnord and Karl Wennberg, as well as the seminar participants at the Jönköping International Business School, Örebro University and Ratio Institute, for helpful comments and suggestions. We are also grateful to the Swedish Agency for Growth Policy Analysis for generously providing access to the data. The usual disclaimer applies.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In this paper, the definition of an SME is a firm with fewer than 250 employees is in line with Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) definition.

2. A competing hypothesis is that banking markets actually work better in rural regions than in urban areas. In rural regions, it is easier for banks to collect important ‘soft’ information about the quality of the entrepreneur via social networks (Silver, Citation2001). In cities, entrepreneurs are more anonymous, and it is more difficult for a bank to assess the creditworthiness of all their customers. If this is the case, then firms might have larger funding gaps in urban areas compared with firms in other regions.

3. One aspect of relationship banking is that when the firm's major bank fails in dire times, it might be difficult for a firm to switch to a new bank (Greenstone et al., Citation2020). This creates a lock-in effect, which can amplify a financial downturn, but could also ensure that banks keep lending in a downturn (DeYoung et al., Citation2015). It can also increase the difficulties a firm faces if their local bank office closes.

4. For the distribution of interest rates on Almi's loans, see Figure A1 in the supplemental data online.

5. A Swedish agency that evaluates and analyses Swedish growth policy.

6. Firms with industry codes related to agriculture or governmental services, as well as firms with zero employees, are removed from the panel. The distribution of industry codes is plotted in Figure A6 and the description of industry codes is shown in Table A10, both in the supplemental data online.

7. A major restructuring of Almi's internal organization occurred in 2011, resulting in no data being available for that year.

8. Some firms could have changed their legal form and have received a new code from SCB, giving them a firm age of zero, but we cannot differentiate between these firms.

9. The data on defaults are mainly for the period 2012–16, because Almi used less stringent data-collection guidelines during the earlier period. Nonetheless, it is interesting to see what determines default levels for firms that borrow directly from banks that lend to credit-constrained SMEs (Glennon & Nigro, Citation2005).

10. These results remain similar if we use a random effects Tobit panel regression with the share of Almi loan as the dependent variable instead of using a fixed effects panel regression.

11. These additional robustness tests are available from the authors upon request.

REFERENCES

- Aghion, P., Fally, T., & Scarpetta, S. (2007). Credit constraints as a barrier to the entry and post-entry growth of firms. Economic Policy, 22(52), 732–779. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0327.2007.00190.x

- Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1992). A model of growth through creative destruction. Econometrica, 60(2), 323–351. doi:10.2307/2951599

- Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for ‘lemons’: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488–500. doi:10.2307/1879431

- Austin, B., Glaeser, E., & Summers, L. (2018). Jobs for the heartland: Place-based policies in 21st-century America. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 49(1), 151–255. doi:10.1353/eca.2018.0002

- Azoulay, P., Fons-Rosen, C., & Graff Zivin, J. S. (2019). Does science advance one funeral at a time? American Economic Review, 109(8), 2889–2920. doi:10.1257/aer.20161574

- Azoulay, P., Graff Zivin, J. S., & Wang, J. (2010). Superstar extinction. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(2), 549–589. doi:10.1162/qjec.2010.125.2.549

- Backman, M., & Wallin, T. (2018). Access to banks and external capital acquisition: Perceived innovation obstacles. Annals of Regional Science, 61(1), 161–187. doi:10.1007/s00168-018-0863-8

- Beck, T., & Demirgüç-Kunt, A. (2006). Small and medium-size enterprises: Access to finance as a growth constraint. Journal of Banking & Finance, 30(11), 2931–2943. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.05.009

- Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Laeven, L., & Maksimovic, V. (2006). The determinants of financing obstacles. Journal of International Money and Finance, 25(6), 932–952. doi:10.1016/j.jimonfin.2006.07.005

- Bellucci, A., Borisov, A., & Zazzaro, A. (2013). Do banks price discriminate spatially? Evidence from small business lending in local credit markets. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(11), 4183–4197. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.06.009

- Berger, A. N., Frame, W. S., & Miller, N. H. (2005a). Credit scoring and the availability, price, and risk of small business credit. Journal of Money, Credit & Banking, 37(2), 191–223. doi:10.1353/mcb.2005.0019

- Berger, A. N., Miller, N. H., Petersen, M. A., Rajan, R. G., & Stein, J. C. (2005b). Does function follow organizational form? Evidence from the lending practices of large and small banks. Journal of Financial Economics, 76(2), 237–269. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.06.003

- Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2002). Small business credit availability and relationship lending: The importance of bank organisational structure. The Economic Journal, 112(477), F32–F53. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00682

- Blackwell, M., Iacus, S. M., King, G., & Porro, G. (2009). Cem: Coarsened exact matching in Stata. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 9(4), 524–546. doi:10.1177/1536867X0900900402

- Blázquez, M., Herrarte, A., & Sáez, F. (2019). Training and job search assistance programmes in Spain: The case of long-term unemployed. Journal of Policy Modeling, 41(2), 316–335. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2019.03.004

- Bornhäll, A., Johansson, D., & Palmberg, J. (2016). The capital constraint paradox in micro and small family and nonfamily firms. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 5(1), 38–62. doi:10.1108/JEPP-10-2015-0033

- Brown, J. D., & Earle, J. S. (2017). Finance and growth at the firm level: Evidence from SBA loans. The Journal of Finance, 72(3), 1039–1080. doi:10.1111/jofi.12492

- Brown, R., Liñares-Zegarra, J., & Wilson, J. O. (2019). Sticking it on plastic: Credit card finance and small and medium-sized enterprises in the UK. Regional Studies, 53(5), 630–643. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1490016

- Canales, R., & Nanda, R. (2012). A darker side to decentralized banks: Market power and credit rationing in SME lending. Journal of Financial Economics, 105(2), 353–366. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.03.006

- Carling, K., & Lundberg, S. (2005). Asymmetric information and distance: An empirical assessment of geographical credit rationing. Journal of Economics and Business, 57(1), 39–59. doi:10.1016/j.jeconbus.2004.07.002

- Conroy, T., Low, S. A., & Weiler, S. (2017). Fueling job engines: Impacts of small business loans on establishment births in metropolitan and nonmetro counties. Contemporary Economic Policy, 35(3), 578–595. doi:10.1111/coep.12214

- Cortés, K. R., & Lerner, J. (2013). Bridging the gap? Government subsidized lending and access to capital. The Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 2(1), 98–128. doi:10.1093/rcfs/cft002

- Cowling, M. (2010). The role of loan guarantee schemes in alleviating credit rationing in the UK. Journal of Financial Stability, 6(1), 36–44. doi:10.1016/j.jfs.2009.05.007

- Cowling, M., Lee, N., & Ughetto, E. (2020). The price of a disadvantaged location: Regional variation in the price and supply of short-term credit to SMES in the UK. Journal of Small Business Management, 58(3), 648–668. doi:10.1080/00472778.2019.1681195

- de Meza, D., & Webb, D. (2000). Does credit rationing imply insufficient lending? Journal of Public Economics, 78(3), 215–234. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(99)00099-7

- DeYoung, R., Glennon, D., & Nigro, P. (2008). Borrower–lender distance, credit scoring, and loan performance: Evidence from informational-opaque small business borrowers. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 17(1), 113–143. doi:10.1016/j.jfi.2007.07.002

- DeYoung, R., Gron, A., Torna, G., & Winton, A. (2015). Risk overhang and loan portfolio decisions: Small business loan supply before and during the financial crisis. The Journal of Finance, 70(6), 2451–2488. doi:10.1111/jofi.12356

- Dow, S. C., & Rodriguez-Fuentes, C. J. (1997). Regional finance: A survey. Regional Studies, 31(9), 903–920. doi:10.1080/00343409750130029

- Farre-Mensa, J., & Ljungqvist, A. (2016). Do measures of financial constraints measure financial constraints? Review of Financial Studies, 29(2), 271–308. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhv052

- Fazzari, S. M., Hubbard, R. G., & Petersen, B. C. (2000). Investment-cash flow sensitivities are useful: A comment on Kaplan and Zingales. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(2), 695–705. doi:10.1162/003355300554773

- Fazzari, S. M., Hubbard, R. G., Petersen, B. C., Blinder, A. S., & Poterba, J. M. (1988). Financing constraints and corporate investment. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1988(1), 141–206. doi:10.2307/2534426

- Franklin, J., Rostom, M., & Thwaites, G. (2019). The banks that said no: The impact of credit supply on productivity and wages. Journal of Financial Services Research, 57, 1–31. doi:10.1007/s10693-019-00306-8

- Glaeser, E. L., Kallal, H. D., Scheinkman, J. A., & Shleifer, A. (1992). Growth in cities. Journal of Political Economy, 100(6), 1126–1152. doi:10.1086/261856

- Glaeser, E. L., & Mare, D. C. (2001). Cities and skills. Journal of Labor Economics, 19(2), 316–342. doi:10.1086/319563

- Glennon, D., & Nigro, P. (2005). An analysis of SBA loan defaults by maturity structure. Journal of Financial Services Research, 28(1–3), 77–111. doi:10.1007/s10693-005-4357-3

- Gompers, P., & Lerner, J. (2001). The venture capital revolution. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(2), 145–168. doi:10.1257/jep.15.2.145

- Granja, J., Leuz, C., & Rajan, R. G. (2018). Going the extra mile: Distant lending and credit cycles. (Working Paper Series No. 25196). National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

- Greenstone, M., Mas, A., and Nguyen, H.-L.. (2020). Do credit market shocks affect the real economy? Quasi-experimental evidence from the Great Recession and ‘normal’ economic times. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 12(1), 200–225. doi: 10.1257/pol.20160005

- Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R. S., & Miranda, J. (2013). Who creates jobs? Small versus large versus young. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2), 347–361. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00288

- Hasan, I., Jackowicz, K., Kowalewski, O., & Kozłowski, Ł. (2019). The economic impact of changes in local bank presence. Regional Studies, 53(5), 644–656. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1475729

- Heckman, J. J., Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. (1998). Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator. Review of Economic Studies, 65(2), 261–294. doi:10.1111/1467-937X.00044

- Heckman, J. J., Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. E. (1997). Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: Evidence from evaluating a job training programme. The Review of Economic Studies, 64(4), 605–654. doi:10.2307/2971733

- Ho, D. E., Imai, K., King, G., & Stuart, E. A. (2007). Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Analysis, 15(3), 199–236. doi:10.1093/pan/mpl013

- Hottenrott, H., & Peters, B. (2012). Innovative capability and financing constraints for innovation: More money, more innovation? Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(4), 1126–1142. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00227

- Hurst, E., & Pugsley, B. W. (2011). What do small businesses do? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2011(2), 73–118. doi:10.1353/eca.2011.0017

- Hyytinen, A., & Pajarinen, M. (2008). Opacity of young businesses: Evidence from rating disagreements. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32(7), 1234–1241. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2007.10.006

- Iacus, S. M., King, G., & Porro, G. (2011). Multivariate matching methods that are monotonic imbalance bounding. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 106(493), 345–361. doi:10.1198/jasa.2011.tm09599

- Iacus, S. M., King, G., & Porro, G. (2012). Causal inference without balance checking: Coarsened exact matching. Political Analysis, 20(1), 1–24. doi:10.1093/pan/mpr013

- Institutet för Tillväxtpolitiska Studier(ITPS). (2002). Utvärdering av almi företagspartner ab:s finansieringsverksamhet (Technical Report). ITPS.

- King, G., & Nielsen, R. (2016). Why propensity scores should not be used for matching (Technical Report/ Working Paper). Harvard.

- Kaplan, S. N., & Strömberg, P. (2001). Venture capitalists as principals: Contracting, screening, and monitoring. American Economic Review, 91(2), 426–430. doi:10.1257/aer.91.2.426

- Kaplan, S. N., & Zingales, L. (1997). Do investment-cash flow sensitivities provide useful measures of financing constraints? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(1), 169–215. doi:10.1162/003355397555163

- Kaplan, S. N., & Zingales, L. (2000). Investment-cash flow sensitivities are not valid measures of financing constraints. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(2), 707–712. doi:10.1162/003355300554782

- Kaya, O., & Masetti, O. (2019). Small and medium-sized enterprise financing and securitization: Firm-level evidence from the euro area. Economic Inquiry, 57(1), 391–409. doi:10.1111/ecin.12691

- Kärnä, A. (2020). Take it to the (public) bank: The efficiency of public bank loans to private firms. German Economic Review, 22(1), 27–62. doi: 10.1515/ger-2019-0023

- Kärnä, A., Manduchi, A., & Stephan, A. (2021). Distance still matters: Local bank closures and credit availability. International Review of Finance, 21, 1503–1510. doi: 10.1111/irfi.12329

- King, G. (2010). A hard unsolved problem? Post-treatment bias in big social science questions. In Hard problems in social science. Symposium, April, Vol. 10.

- Kirschenmann, K. (2016). Credit rationing in small firm–bank relationships. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 26, 68–99. doi:10.1016/j.jfi.2015.11.001

- Klagge, B., & Martin, R. (2005). Decentralized versus centralized financial systems: Is there a case for local capital markets? Journal of Economic Geography, 5(4), 387–421. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbh071

- Klagge, B., Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2017). The spatial structure of the financial system and the funding of regional business: A comparison of Britain and Germany. In Handbook on the geographies of Money and finance (pp. 125–155). Edward Elgar.

- Lee, N., & Brown, R. (2017). Innovation, SMEs and the liability of distance: The demand and supply of bank funding in UK peripheral regions. Journal of Economic Geography, 17(1), 233–260. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbw011

- Lee, N., & Drever, E. (2014). Do SMEs in deprived areas find it harder to access finance? Evidence from the UK small business survey. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 26(3–4), 337–356. doi:10.1080/08985626.2014.911966

- Lee, Y. S. (2018). Government guaranteed small business loans and regional growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 33(1), 70–83. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.11.001

- Lehmann, E., Neuberger, D., & Räthke, S. (2004). Lending to small and medium-sized firms: Is there an east–west gap in Germany? Small Business Economics, 23(1), 23–39. doi:10.1023/B:SBEJ.0000026024.55982.3d

- Nguyen, H.-L. Q. (2019). Are credit markets still local? Evidence from bank branch closings. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 11(1), 1–32. doi:10.1257/app.20170543

- Nilsson, P. (2017). Productivity effects of cap investment support: Evidence from Sweden using matched panel data. Land Use Policy, 66, 172–182. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.04.043

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2016). OECD reviews of innovation policy: Sweden 2016 (Technical Report). OECD Publ.

- Petersen, M. A., & Rajan, R. G. (2002). Does distance still matter? The information revolution in small business lending. The Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2533–2570. doi:10.1111/1540-6261.00505

- Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (1998). Financial dependence and growth. American Economic Review, 88(3), 559–586.

- Ryan, R. M., O’Toole, C. M., & McCann, F. (2014). Does bank market power affect SME financing constraints? Journal of Banking & Finance, 49, 495–505. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.12.024

- Saunders, A., & Steffen, S. (2011). The costs of being private: Evidence from the loan market. Review of Financial Studies, 24(12), 4091–4122. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhr083

- Schäfer, D., Stephan, A., & Mosquera, J. S. (2017). Family ownership: Does it matter for funding and success of corporate innovations? Small Business Economics, 48(4), 931–951. doi:10.1007/s11187-016-9813-y

- Schäfer, D., Werwatz, A., & Zimmermann, V. (2004). The determinants of debt and (private) equity financing: The case of young, innovative SMEs from Germany. Industry and Innovation, 11(3), 225–248. doi:10.1080/1366271042000265393

- Silver, L. (2001). Credit risk assessment in different contexts: The influence of local networks for bank financing of SMEs, PhD thesis, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

- Soete, B., & Stephan, A. (2004). Introduction: Entrepreneurship, innovation and growth. Industry and Innovation, 11(3), 161–165. doi:10.1080/1366271042000265357

- Stein, J. C. (2002). Information production and capital allocation: Decentralized versus hierarchical firms. The Journal of Finance, 57(5), 1891–1921. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.00483

- Stephan, A. (2011). Locational conditions and firm performance: Introduction to the special issue. The Annals of Regional Science, 46(3), 487–494. doi:10.1007/s00168-009-0358-8

- Stiglitz, J. E., & Weiss, A. (1981). Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. American Economic Review, 71(3), 393–410.

- Tingvall, P. G., & Videnord, J. (2020). Regional differences in effects of publicly sponsored R&D grants on SME performance. Small Business Economics, 54, 951–969. doi:10.1007/s11187-018-0085-6

- Ughetto, E., Cowling, M., & Lee, N. (2019). Regional and spatial issues in the financing of small and medium-sized enterprises and new ventures. Regional Studies, 53(5), 617–619. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1601174

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2009). On estimating firm-level production functions using proxy variables to control for unobservables. Economics Letters, 104(3), 112–114. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2009.04.026

- Zhao, T., & Jones-Evans, D. (2017). SMEs, banks and the spatial differentiation of access to finance. Journal of Economic Geography, 17(4), 791–824. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbw029