ABSTRACT

To what extent do subnational differences in the configurations of formal and informal institutions shape the relative capacities of state and regional agents? This article considers the distribution of capacities and powers among regional actors, as defined by their organizational roles and the power of the state. After comparing the management of economic change in two peripherally located and coal-dependent areas in different States in Australia, the article concludes that accounts of institutional change in regional studies have paid insufficient attention to the limitations on agency arising from organizational positioning and the ‘top down’ assertion of state power.

JEL:

INTRODUCTION

That institutional arrangements condition social action and shape regional path trajectories is demonstrated by an extensive literature associating positive developmental trajectories with the quality and effectiveness of institutions (Amin & Thrift, Citation1995; Dellepiane-Avellaneda, Citation2010; Martin, Citation2000; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013; Rodríguez-Pose & Ketterer, Citation2020; Rodríguez-Pose & Storper, Citation2009). Contemporary interest in the conditions under which entrepreneurial agents are able to effect institutional change to advance their regional development objectives concentrates interest on agency (Garud et al., Citation2007; Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020), but tends to overlook the role of institutional structures and arrangements in shaping the objectives of regional change agents (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2009) and in conditioning the trajectories of change (Grabher & Stark, Citation1997; Macleod & Goodwin, Citation1999; Miörner, Citation2020). Advancing understandings of evolutionary change demands interrogation of agency, socio-institutional structures and their interactions under different socio-economic conditions (Evenhuis, Citation2017; Gong & Hassink, Citation2019; Hassink et al., Citation2014; MacKinnon et al., Citation2009; Martin & Sunley, Citation2015; Zukauskaite et al., Citation2017). Rebalancing the research effort demands more rigorous theorization of the role of the state and its agencies (Boschma & Martin, Citation2010; Pike et al., Citation2016), and of associated power dynamics (Oinas et al., Citation2018; Yeung, Citation2005).

This article considers the role of the state in relation to debates about power dynamics, embedded agency and institutional change and how these affect peripheral regions. It suggests that the nature and extent of the capacities of institutional change agents depends on shifts in the dynamics of geometries of power as the configurations of organizations and the capacities of agents evolve. The role of power relations in regional change is well established, but to date the focus has been either on the modalities of power available to particular agents (Sotarauta, Citation2016), or on the networks of relational power produced by groups of regional change agents working together (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Dawley, Citation2014). This, we argue, does not sufficiently account for the influence of the state in shaping agential capacities and regional change processes. This article examines how differences in the interaction of regional forces ‘upward’ and central forces ‘downward’, as well as subnational differences in organizational configurations, shape the relative capacities of state and regional agents. It considers the power of the state in shaping organizational roles and the distribution of capacities among regional actors.

These processes are illustrated in two case studies comparing attempts to forge transformative change in two peripheral regional areas in different States in Australia, both places where higher level policies accelerating the phase out of coal-based electricity production are compromising the industries that in the past have dominated these regional economies.Footnote1 The Australian case is illuminating because the introduction of devolved responsibilities and collaborative systems of governance are less pronounced, compared with the European context, making it easier to observe state strategies directly. The narrative draws out how State-based differences in institutional arrangements produce different relationships between State and regional administrations, strategically selects which local agents are empowered to influence outcomes and tempers the capacities available to local agents. We show that in this context, local and regional actors are most effective when they align their strategies to those of higher tiers of government.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. This introduction is followed by a review of the extant literature on institutions, organizations and embedded agency in regional development. It suggests theorizations of regional change would benefit from more careful interrogation of agency, the role of the state and the operation of power. The third section begins with an introduction to Australia’s governmental framework before examining how it shapes the options available to actors in the two case studies – the Upper Hunter in New South Wales (NSW) and the Latrobe Valley in Victoria. The penultimate section reflects on the role of the state in shaping regional development trajectories. The conclusion argues that accounts of institutional change in regional development have paid insufficient attention to the limitations on agency arising from organizational positioning. It calls for renewed attention to how state-dominated geometries of power condition the potentials for localized action, and more careful exploration of the impact of organizational changes on deeper institutional arrangements.

INSTITUTIONS, ORGANIZATIONS, AGENCY – LOCATING THE STATE

This section surveys contemporary understandings of the relationship between institutions, organizations and agents in regional studies before introducing the overlooked elements of embedded agency, the role of the state and the effect of power dynamics.

Institutions and organizations in regional development

The importance of institutions in stimulating or constraining regional development is well-established (Ashiem & Gertler, Citation2005; Gertler, Citation2010; Martin, Citation2000; North, Citation1990), but there is confusion about both the definition of institutions and the mechanisms through which they influence regional development outcomes. As Bathelt and Glückler (Citation2014, p. 340) observe, institutions are ‘often vaguely defined, refer to different meanings, or almost become a “black box” to relate to otherwise unexplained influences in economic development’. The word ‘institutions’ might refer to deep social norms (North, Citation1990); to habits and routines (Hodgson, Citation2008); to durable, territorially specific organizational structures (Boschma & Frenken, Citation2009); or to formal frameworks of government (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2009; Charron et al., Citation2014).Footnote2 Typically, the regional development literature follows North’s (Citation1990, p. 477) definition of institutions as the ‘rules of the game in a society’ (Gertler, Citation2010). Bathelt and Glückler (Citation2014, p. 340) emphasize underlying social structures – such as trust, property rights or the work ethic – when they describe institutions as ‘accepted, existing patterns of interaction … [and] relatively stable patterns of social practice based on mutual expectations’. Similarly, Hodgson (Citation2006, p. 18) defines institutions as ‘systems of established and embedded social rules that structure social interactions’.

Confusion arises over the question of whether organizational forms are institutions in their own right or merely material expressions of underlying (norm-based) institutions. Hodgson (Citation2006) allows that organizations are a form of institution with established boundaries, sovereignty and organizational structure, while North (Citation1990) saw organizations as ‘players’ of the games within the rules established by institutions, as do Bathelt and Glückler (Citation2014). However, North’s (Citation1994) distinction between informal and formal institutions is now widely accepted. The familiar tacit-codified binary distinguishes one from the other in Amin’s (Citation1999, p. 367) definition of informal institutions ‘as individual habits, group routines and social norms and values’ and formal institutions as ‘rules, laws and organizations’. Rodríguez-Pose and Storper (Citation2009) adopt this approach and contend that what matters for development is an efficacious balance between formal and informal institutions. Rodríguez-Pose (Citation2013) stresses the relationship between formal and informal institutional/organizational structures – referring to institutions and their fitness for purpose – and institutional arrangements, which refers to the articulations among various institutions (see also MacKinnon et al., Citation2009). Recent contributions stress the recursiveness of these interactions. For Zukauskaite et al. (Citation2017, p. 329), the form adopted by organizations reflects institutional pressures, but at the same time organizations are the ‘means and mechanisms via which institutions … are enacted and further reinforced’. Similarly, Sotarauta et al. (Citation2021) argue that incremental institutional change is produced by interactions among regulatory, normative and socio-cultural institutions.

In innovation-oriented accounts of regional development, the quality of institutions becomes the central driver of economic performance via their role in facilitating cooperation, mobilizing regional voice and fostering linkages among productive sectors (Farole et al., Citation2011; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2012). Consequently, improving the quality of the local – formal and informal – institutional fabric has become a major justification for place-based regional policy (Tomaney, Citation2014). Improving governance through institutional reform is considered especially important for peripheral or lagging regions where lock-ins might close down potential development pathways (Hassink, Citation2005). Rodríguez-Pose and Ketterer (Citation2020) suggest that lagging regions have the most to gain from improving their institutional fabric, and for Trippl et al. (Citation2018) this is best facilitated by local agents forging stronger extra-local network linkages.

If improving the institutional fabric is the key to the regeneration of regional economies, then the role of institutional entrepreneurs becomes a central concern (Battilana et al., Citation2009; DiMaggio, Citation1988). Entrepreneurs champion change by doing ‘institutional work’ to alter organizational arrangements (Lawrence et al., Citation2011). Their motivations might be to advance particular place-specific development projects, to (re)invigorate regional agency, to trigger the processes of discovery which underpin innovation, or to aid legitimizing other changes (Garud et al., Citation2007). Such agents flourish when conducive ‘field’ or ‘organizational’ conditions reinforce individual motivations, and this underscores the need for multilevel analysis (Battilana & D’Aunno, Citation2009). The former refers to characteristics of the context, such as an external crisis, while the latter arises from fortuitous organizational positioning. For Zukauskaite et al. (Citation2017, p. 339) examining ‘how actors involved in path development activities capitalize on complementary and reinforcing institutions at other levels and develop strategies to overcome contradicting ones’ is key to overcoming regional development bottlenecks. In a similar vein, Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020, p. 705) see development outcomes as the product of ‘what actors do to create and exploit opportunities in given contexts’. By reframing contextual and institutional constraints as ‘opportunity spaces’ they focus attention on the available and feasible range of potential strategic interventions available to regional entrepreneurs.

This account of institutions and agency brings actors to centre-stage and tilts the long-standing agency-structure problematic (Giddens, Citation1979) in the direction of agency. By focusing on the immediacy of opportunity spaces, it tends to push the laws, regulations and policies of governments – and the wider social justifications for their existence – into the background. There is also a strong tendency to privilege the micro-to-macro direction of institutional change rather than to dwell on macro-to-micro possibilities (Jepperson & Meyer, Citation2007). Much of the work in this vein assumes that downward macro-to-micro change is discouraged by policy disinterest, broader governmental agendas or the inability of central agencies to mobilize the necessary resources (Weller & Rainnie, Citation2021). Some recent work rekindles interest in how organizational forms can be change agents and shape the agency of others, for example, Evenhuis’s (Citation2017) consideration of ‘top-down’ innovation and Miörner’s (Citation2020) notion of system selectivity.

The following sections propose this account would be strengthened by reorienting to a less voluntaristic formulation of agency, by reintroducing the role of the state as a distinctive form of organization with entrepreneurial agency, and by greater attention to the dynamics of interorganizational power relations.

Reorienting agency

The agent-oriented framing of institutional work views agency in voluntaristic terms, as though individuals are able to distance themselves from, transcend or resist the cognitive influence of the institutions in which they are embedded (Lawrence et al., Citation2011, p. 54). The independence of actor identities and interests is taken for granted. This underplays the extent to which structures (that is, informal and formal institutions) shape agential capacities and therefore the range of strategies and tactics available to actors. Powell and DiMaggio (Citation1991), for example, recognized the stringent limits on individual agency imposed by internalized rules of conduct, which led them – in their ‘paradox of embedded action’ – to question the possibility of intentional institutional change. More recently, Drori et al. (Citation2009) have suggested that actors follow ‘scripts’ that not only define their interests, purposes and actions but also link them into (globalized) networks of organizations and discourses. Weller (Citation2017) shows that local actors revise these scripts to support pre-existing political positions. Both agree that local development entrepreneurs are always embedded in wider networks and extra-local projects and that these forces shape their agency.

In Emirbayer and Mische’s (Citation1998, p. 984) understanding, agency can have different dimensions that vary with the context, rendering it ‘neither radically voluntarist nor narrowly instrumentalist’. The emphasis on the recursiveness of the agency-structure binary in Jessop’s strategic relational approach provides a middle road between voluntarism and embeddedness. Thus, for MacKinnon et al. (Citation2019, p. 125), the agency of agents operating in dynamic and evolving systems works to legitimize or delegitimize institutions even as the evolving powers of institutions reshape the ambitions and capacities of the actors. In their notion of institutional environments, sets of rules and norms inform the behaviour and strategies of actors but do not determine their actions. Accepting that identities and institutions emerge and develop in specific historical and locational contexts, the degree of voluntarism of agential action is likely to vary across space and over time, making the configurations that emerge in practice an empirical question.

Institutions are ‘more or less enduring’ (Lawrence et al., Citation2011, p. 53), but some are more enduring than others, some need more maintenance work than others, and some are more susceptible than others to the efforts of institutional entrepreneurs. If the institutional context shapes the roles of actors and the sorts of institutional work available to them, then the task is to better understand how some actors become capable of institutional work, and how the context influences how their interests are constructed (Fligstein, Citation2001). The actions of individual agents in regional development are likely to be governed by multiple, potentially conflicting organizational and institutional roles and positions, creating contradictory imperatives that suggest varied action options (Fraser, Citation1989). Although the regional studies literature focuses on opportunistic forms of action, challenging institutions from the outside (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020), Mahoney and Thelen (Citation2009) extend the range of types of change agents by including saboteurs and symbionts dedicated to destabilizing organizations from the inside. From a distributional perspective, the ‘losers’ from existing arrangements might be more likely to become institutional entrepreneurs, but if that were the case, change processes would lose momentum as soon as the losers won a redistribution of resources (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2009).Footnote3

A related problem is that much of the discussion of agency in regional studies confines the notion of agency to purposeful actions for transformative ends (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). Yet as Bellandi et al. (Citation2021) and Sotarauta et al. (Citation2021) have observed, a focus on successful change excludes – and denies the legitimacy of – a range of other actions and purposes including local actors defending the status quo or higher level actors vetoing locally inspired projects. Restricting the range of admissible forms of agency weakens the capacity to understand the complexity of the processes in play. Finally, accounts of institutional entrepreneurialism that focus on success stories risk exaggerating the short-term malleability of organizational arrangements, underestimating the extent of political contestation in ‘left behind’ places, and overrating endogenous change relative to change imposed by external forces (Marques & Morgan, Citation2018).

Reintroducing the state

This brings us to the role of the state. Most regional contexts host many organizations, many of which exist in hierarchical relations to one another. State and quasi-state agencies often play a crucial, if not dominant, role (Cumbers & Mackinnon, Citation2011; Dawley, Citation2014; Dawley et al., Citation2015). Yet in contemporary studies of institutions in evolutionary regional development, explicit discussion of the role of the state is largely absent. This is unfortunate because, as the varieties of capitalism literature attests, the nature of states and their styles of rule have profound implications for regional development. The state is an especially enduring institution by virtue of its constitutional formation and rule-making capabilities. These observations suggest an urgent need to better locate the state’s role in evolutionary regional studies.

In geographical scholarship, Jessop’s strategic relational understanding of the state has been the most influential. Here the state comprises ‘a set of institutions concerned with the territorialisation of political power … forged through the ongoing engagements between agents, institutions and concrete policy circumstances’ (Jones, Citation2018, pp. 28, 29). The state is ‘strategically selective’ about which places and projects it supports, and this generates uneven outcomes for different places and social groups. The strategic relational view does not see the state as ‘outside’ the social or economic domain, acting as an external orchestrator, nor does it assume the state to be a coherent and unified strategic actor with the capacity to mandate change consistent with its policy agency. Rather, Jessop (Citation2016, p. 20) stresses the four dimensions that give rise to the state’s ‘polymorphic’ and ‘variegated’ nature: (1) a set of apparatuses of rule over (2) territories and (3) populations, held together by (4) a semantic framework. The latter – the state’s role in managing discourse and creating meaning – has become increasingly important in advanced economies (Jessop, Citation2016). For example, Dobbin (Citation1994) shows that the political cultures of different states – effectively the deep institutional form underpinning the organization of the state – shape the identification and framing of regional problems which in turn circumscribes the range of conceivable solutions. The strategic relational framework recognizes that the evolution of the state is not simply a reaction to economic conditions but results from the increasingly complex interplay and interdependencies among economic, social, cultural, environmental and political forces. Legitimizing (market-supporting) modes of social organization (Gramsci, Citation1971) and reproducing its own power to govern (Mann, Citation1984) are both crucial state objectives that might conflict with regional ambitions.

The state’s strategies and objectives impose conditions on regional agency. When involved in regional development plans and projects, the state’s representatives, as with the employees of other organizations, are obliged to act in accordance with their organization’s norms and policies. In the practice of regional development, the out-posted representatives of central governments might become advocates for local projects and direct their energies to changing the state’s policies or priorities; or the reverse, their commitment to enacting the state’s policies could put them into conflict with local interests. Over time, through repeated interactions with other institutions and organizations, different branches of the state tend to form allegiances with their various constituencies – a process described as institutional capture (Phelps, Citation2008) – leading, in the absence of remedial action, to the gradual divergence in the purposes, programmes and motivations of the state’s various departments, agencies and levels of administration. This process in effect internalizes threats to accumulation or legitimacy within the state apparatus, making states unavoidably conflicted internally (O’Neill, Citation1997). The state becomes an arena of struggle over conflicting goals (Offe, Citation1984), with the resulting incompatibilities likely to manifest at the regional scale, hampering the state’s coordination and effectiveness (Fuller, Citation2010), and leading to internal demands for institutional reform. As relationships with other organizations are continuously renegotiated, in part in response to policy changes, the relationships between different tiers of governments, and between branches within tiers also evolve. This makes the state both the medium and the outcome of policy processes (Jessop, Citation1990).

The contemporary regional studies literature discusses the merits of networking beyond the territorially defined region (Trippl et al., Citation2018), but it avoids engaging with the hierarchical dimension of extra-local associations, omitting consideration of the imposed will of ‘higher’ levels of government and the decisions of the head offices of global firms. The flat ontology of networks levels out differences in power and resources among the organizations involved in regional development and erases awareness of the role of the state as an exceptionally powerful player in the regional development game. In short, we need to understand the state as simultaneously an external orchestrator of regional development fortunes and a key player in shaping and maintaining the complementary and reinforcing regional institutions that contribute to regional path development activities.

Interrogating power relations

Appreciating the state’s role necessitates consideration of power dynamics (Oinas et al., Citation2018; Yeung, Citation2005). Since power dynamics produce a degree of organizational stratification (Joseph, Citation2004), networked ontologies focused on horizontal relationships need to be supplemented with a recognition of the hierarchical dimension of power and its impact on regional dynamics.

Consistent with its focus on individualized agency, a centred view of power as individualized capacity dominates the contemporary regional change literature. Sotarauta (Citation2016), for example, draws on Lukes (Citation2005) to distinguish overt and covert power, decision making and non-decision making, agenda setting and the subtle influence of preference shaping. He identifies six forms of power: the power of legitimacy derived from a position held; referent power derived from the ability to attract others to a position or cause; the power of knowledge (including the expert power of authoritative knowledge and the informational power associated with holding current knowledge); the reward power that comes from the ability to reward others and control resources; and, the coercive power to force others to a particular action or prohibit them from taking action. Sotarauta (Citation2016, p. 73) defines institutional power as ‘a combination of legitimate power and reward power, but not coercive power’. In this framing, power tends to be viewed as a one-to-one dyadic interaction between agents, and this underplays the networked forms of power exercised by states and political movements.

Allen (Citation2003) identified three ‘spatial vocabularies’ of power, the first two of which are relevant to the current discussion. The first is, as above, power as the capacities held in store by entities, the second is networked power as mobilized in collective associational action, and the third is power as an imminent force.Footnote4 In regional development, networked and associational forms of power are especially important. These are inherently political and multi-scalar in nature (Allen & Cochrane, Citation2007). Associational power is diffused across participating agents, imbuing agency with a collective quality, and making actors working in combination more powerful than individual entrepreneurs. For Mahoney and Thelen (Citation2009, p. 7), for example, the capacity of different agents to effect institutional change depends on the quality of the coalitions they forge – or that form spontaneously – in the course of distributional struggles. In their view, the sources of change in institutions are less about the entrepreneurial action of individual agents and more about shifts in the balance of power among associated organizations. Their analysis suggests that revised analytical frameworks could pay more attention to which organizations are involved in regional change, how they are related to each other and what role political affiliations play in mediating their relationships. They stress that both the types of power available to various agents and the susceptibility of agents to different forms of power are shaped by their institutional and organizational positions, and this limits the range of each actor’s strategic options. Allen (Citation2003) also stresses the importance of distinguishing between power as capacity – as a resource or potential for action – from power as the exercise (or not) of that capacity. The actual exercise of power is always relational, situationally specific and delimited by the capacities of participating actors (Sayer, Citation2012). Relationality implies that the activation of capacity is rarely unilateral; rather, it depends on the capacities and susceptibilities of other actors. The net effect of all power relations, at any time and place, is a geometry of power incorporating horizontal (networked) and vertical (hierarchical) forms and which ‘we tend to think of as the balance, or geography of power’ (Sayer, Citation2012, p. 184).

When thinking about state power, Mann (Citation1984, p. 113) usefully introduces the notion of infrastructural power, defined as the state’s ‘institutional capacity … to penetrate its territories and logistically implement decisions’. Through this diffused and associational form of power, the centralized state binds local communities to its strategies. When infrastructural power is weak, Soifer (Citation2008) argues, politics is likely to be shaped less by formal institutions and more by informal institutions, and vice versa.Footnote5 Multilevel governance arrangements and temporary development coalitions in regional development typically put state and quasi-state actors in central roles (Dawley, Citation2014), but often in a way that makes the state appear equivalent to the other organizations with which it collaborates. In Mann’s (Citation1984) account, however, the state is crucial to regional development governance through its infrastructural power, that is, through its capacity to distribute and delegate powers to various agencies and its power to establish the spatial organization of rulemaking within its territory. In reality, then, many regional organizations and networks operate in the ‘shadow’ of state hierarchies (Whitehead, Citation2003). The influence of state power might play out in the discursive reframing of issues and problems, the reorganization of inter-scalar connectivities, or the reordering of territorial boundaries (Brenner, Citation2001). Jessop (Citation2001) stresses that state power is emergent, in the sense that its actualization depends on other contingent conditions, and that its operation is never independent of relations in the economic, social and ideological domains.

These considerations suggest that understanding the relationship between organizational arrangements and agency in regional development at the regional scale demands simultaneous attention to centralized and dispersed forms of power, to the uneven distribution of capacities among agents, and to the role of different levels of government in shaping those capacities. This means interrogating how states empower some actors more than others, but also how the exercise of power influences and reconfigures wider geometries of power. The next section explains how these considerations play out in Australia.

STATE AGENCY AND LOCAL AGENCY IN THE AUSTRALIAN CONTEXT

Australia is an advanced capitalist economy with well-developed formal and informal institutions. The foundational informal institutions like trust and social norms are maintained by well-established rules of (Common) law, there is a well-established system of state authority, and a plethora of quasi-independent state-agencies established to deal with specific policy realms. Australia is a Federation of States. The Federal government has jurisdiction over international and interstate matters, including international trade, while the component States control most internal matters including responsibility for regional development. This separation creates challenges for regional development policy because the States have no control over the central levers of international competitiveness (such as exchange rates, tariffs and migration policy). Local governments exist but are not recognized in the Constitution as a separate autonomous tier of government. Rather, local government is answerable to its corresponding State government, and this means that institutional entrepreneurs tend to focus their efforts at the State scale. The nation’s political and legal systems follow the Westminster model at both Federal and State levels, except that an American-style Senate and a compulsory and preferential voting system increase government responsiveness to the wishes of electorates (Weller, Citation2021). Australia’s Constitution was designed to be difficult to amend but the system has evolved over time, mainly in response to coordination problems between Federal and State scales.

Infrastructural power is principally the domain of State level governments and their agencies, which work with business and civil society groups to coordinate resources. Political and social organizations are abundant, with many existing to influence policy and capture resources. Typically, political organizations are national in scope but organized into State-based branches to facilitate interaction with both tiers of government. Most States have a dominant capital city (Sydney in NSW and Melbourne in Victoria), but beyond these centres the sub-State scale is organizationally thin. The nodes of geometries of power gravitate to the urban centres.

In Australia, the word region describes non-metropolitan areas, most of which are sparsely populated with few major urban settlements. These regions are doubly peripheral, ‘lagging’ both relative to Australia’s core capital cities and relative to the flows of the global economy. Although Australia has been categorized as a ‘Liberal Market’ economy, it retains strong redistributive policies and mechanisms (Weller & O’Neill, Citation2014). Peripheral locations rely on redistributive transfers either directly to households, via the social protection system, or indirectly via government or government-funded social services. In such areas, government has a heavy footprint, with the public sector a major source of employment. Historically, Australia’s non-metropolitan settlements were created and nurtured by development-oriented governments and did not emerge from incremental growth processes (Beer et al., Citation2003). Consequently, the elements associated with endogenous growth are not well established (Beer & Lester, Citation2015), and intervention by higher tier governments to facilitate development is the accepted norm. In recent times, State-level regional development policy in peripheral locations has sought to replicate European ‘Smart Specialisation’ approaches promoting the formation of regional (sub-State) business networks and regional innovation systems. This approach assumes – quite wrongly in Weller and Rainnie’s (Citation2021) analysis – that regional development in peripheral locations has been constrained either by weak institutional systems or by strong local institutions locked-in to the service of, or captured by, moribund fossil fuel industries. Weller and Rainnie (Citation2021) instead attributes the failure of these institutional fixes to insufficient local value capture and underlying weakness in market competitiveness due to factor price and distance disadvantages.

History and time have generated State-level differences in the configurations of both formal and informal institutions. NSW has a more liberal (free trade) approach while Victoria is more oriented to a statist (government intervention) approach. This deep institutional difference is reinforced by the political complexion of current elected governments: NSW has a low intervention politically Liberal government, but Victoria has a high intervention Labor government. In both States, governments have sought to operate collaboratively with community organizations, and in both this has generated intermittent corruption scandals. In Victoria, local government is tightly controlled by the State administration, while in NSW local government is more autonomous and more responsive to its local community. However, with very few services provided locally, European notions of devolution are not applicable. In Victoria, we will show below, the State government’s infrastructural power penetrates to a deeper, more local, level than in NSW.

With power and resources concentrated at State level, the configurations of power that emerge in relation to regional development also gravitate to State level, although more intensely so in Victoria than NSW. This means that although organizations are thin in regional areas, numerous outposted agents of State-level organizations (government, firms and community) are placed in regional areas, where they collaborate regionally while at the same time enacting the policies of their organization. This leads to coordination problems and to the escalation of decision-making ‘upward’. Regional development agencies positioned between the state and local scales – such as federal Regional Development Australia Committees and multilevel structural adjustment committees – have been inserted to improve coordination, but they have a limited role, few resources and tend to operate in the shadow of State activities. In Australia, regional development agencies and funding programmes tend to come and go depending on which political party is in power (Beer et al., Citation2003). Incessant change in regional policy settings (‘churning’) adds to policy ineffectiveness and fuels the accusation that interventions are pork-barrelling exercises (Jones, Citation2018; Weller, Citation2021).

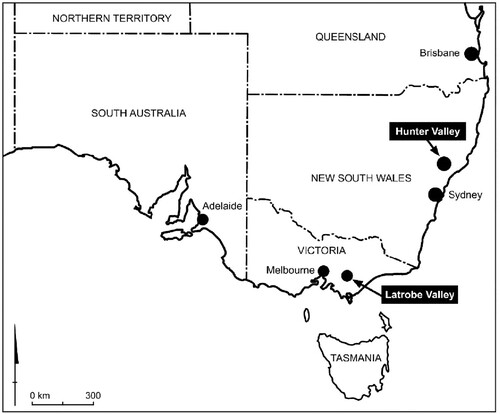

The two case study areas described below – the Upper Hunter Valley in NSW and the Latrobe Valley in Victoria – are both relatively peripheral to the centres of power, both coal-dependent areas facing the phasing out of coal production, and both places where Smart Specialisation-type policies have failed to gain traction. shows the locations relative to State capital cities.

In both places coal-based electricity production was established as a public sector initiative, and later privatized, leaving a strong residual legacy of sector-based regulatory institutions. However, the Upper Hunter’s coal resource is high grade (low carbon emission) black coal which is likely to continue to be mined for export for some years to come, whereas Latrobe’s coal is low-grade (high carbon emission) brown coal (lignite) which will be completely closed in the near future. Nonetheless, the description below reveals similarities in approach which arise from policymakers involved with both places drawing actively on knowledge of each other’s experiences, as well as on international best practice in the transition from coal (Weller, Citation2017; Weller et al., Citation2020). The case studies reveal that in Latrobe the transition has been orchestrated from State level, while in the Upper Hunter leadership has come from the local government.

The Latrobe Valley

The Latrobe Valley is an industrial enclave in the rural region of Gippsland, Victoria, located a two-hour drive east of the state capital – Melbourne (). The Valley’s abundant brown coal resources were developed by the Victorian Government from the 1920s, and at that time the state orchestrated all aspects of the Valley’s prosperous development with paternalistic authority (Langmore, Citation2013). The privatization and rationalization of the power stations in the 1980s devastated the local community as more than half the local energy workforce lost employment. Despite numerous government initiatives since then, new industries have not established, and until recently the Valley’s trajectory has been one of relentless decline. Weller (Citation2012, Citation2019) attributes the failure of past policies to approaches that seemed more concerned with the State’s legitimacy – with appearing to act on just transition to court urban voters – by discursive reframing of the problem rather than by tackling the economic foundations of Latrobe’s challenges.

The trigger for change was the political crisis following an uncontained fire in an open cut coal mine in the summer of 2014. The fire exacerbated local community dissatisfaction with government and a subsequent inquiry found failures of both regulation and enforcement in the energy sector and the near absence of coordination among different government departments and agencies. In other words, the problem was framed as an issue of embedded agency – where agents in Latrobe in theory worked to achieve their department’s objectives but in practice had been ‘captured’ by their constituencies, resulting in policies not implemented effectively and a ‘silo mentality’ that propelled government agencies into conflict.

In response, tightened regulations soon resulted in the closure of the Hazelwood Power Station. To restore legitimacy, the State government allocated structural adjustment expenditures of more than A$225 million in the years 2017–20 focused on job creation, mainly in rebuilding community amenities, rail and road upgrades, housing developments and upgrading social services. The government established an agency – the Latrobe Valley Authority (LVA) – to coordinate the delivery of the assistance and to improve the coordination among government agencies. It reported directly to the Victorian Premier, the only person empowered to resolve interdepartmental squabbles over local resource allocations. The grounding of power was State based and Melbourne centred, thereby bypassing elected local government and reinforcing its marginalization. Some influential local voices – in particular, the Gippsland Trades and Labour Council (GTLC) – supported this authoritative intervention. Whilst the State government, via the LVA, has promoted cooperation with the GTLC, local business, environment groups and the nearby university to legitimize its interventions and build a local innovation system, it has not relied on these associations. The Victorian government’s visible deployment of reward power has consolidated its infrastructural power over the area. Importantly, however these interventions have not (yet) resulted in new private investment that would address the long-term problem of industrial stagnation.

To summarize, the geometries of power licensing these developments were centred in the State capital, Melbourne, and informed by the international debate about phasing out coal. To reproduce its own power to rule (Mann, Citation1984) the Victorian government needed the support of both urban voters concerned about the environment and trade unionists. Re-distributional funds flowed to the Latrobe Valley because its future was positioned as the litmus test for the government’s delivery of a ‘just’ transition. This example highlights the importance of meaning-making in contemporary statehood (Jessop, Citation2016).

The Upper Hunter Valley

The Upper Hunter Valley is found two hours west of the NSW port city of Newcastle, and three hours north of Sydney (). The Upper Hunter region is both isolated and sparsely populated, with a local economy dominated by two industries: agriculture and coal mining. The area has abundant resources of high-quality black coal, most of which is exported, but some of which is used to generate electricity for domestic use. As in Victoria, the area’s power stations were developed as State-owned assets, and privatized in the late 2000s. However, the Upper Hunter’s situation is not as dire as the Latrobe case because much of its energy workforce commutes from the urban Newcastle area and because the coal export industry will continue to provide local employment for some time.

Here the structures of power are markedly different to the Latrobe Valley. The State government in NSW has historically been less interventionist, and it allows local government more capacity for agency. As in Victoria, government, community, and business organizations in the Upper Hunter are strongly linked to NSW State and national organizations, but they cohere more effectively at the regional scale and express a ‘regional’ voice. Local government in the Upper Hunter sees itself as responsible for establishing a transformative economic development pathway and for delivering a just transition. This reflects, in part, regulatory arrangements that have delivered more authority over, and more value from, mining activities to the local administration (as compared with Victoria). Control of resources and more extensive regulatory capacities gives local government in the Upper Hunter more capacity for exercising both coercive and reward power. In contrast to Victoria, the coal mines in the Upper Hunter obtain their licence to operate from local government and pay royalties for that privilege. These regulatory capacities also mean that local government in the Upper Hunter has repeated interactions with the energy sector which engenders some predictability and trust in discussions around the future. In the Upper Hunter, although there are continuing debates about the direction of that future, the agents concerned are more likely to be embedded in the region and regional interests.

The NSW State government is less obviously present in the Upper Hunter area compared with the Latrobe Valley, suggesting that the weaker exercise of State infrastructural power has created a space for local government and other organizations to fill. Regional development agencies are more influential than in Victoria, although the Upper Hunter has an uneasy relationship with (Lower) Hunter Valley agencies centred in the city of Newcastle. The weak footprint of State-scale networks of power in the Upper Hunter Valley can be partly explained by a State political environment wherein the Liberal state government is less concerned with attracting ‘green’ votes, and less concerned with basing its legitimacy on the idea of just transition.

The long-term involvement of local government in the oversight of mining activities in the Upper Hunter has created opportunities for Council to promote the repurposing, rather than outright closure, of coal-related industrial sites (Weller et al., Citation2020, Citation2021). Resource-based power delivers it a degree of leverage that is not available to local government in Victoria, but local government has also marshalled expert knowledge (knowledge power) and built local alliances around the shift to renewable energy sources (referent power). At the time of writing, the establishment of a battery power facility is planned for the soon-to-close Liddell Power Station site. But there are obstacles as these local initiatives are not well aligned to the State level energy future ‘Roadmap’, which makes it harder to secure State funding and makes the plans vulnerable to replacement by funded initiatives in other places.

AGENCY, POWER AND THE STATE

Attempts to manage the transition from coal and forge new developmental pathways have produced institutional innovation in relation to both the Latrobe and Upper Hunter sites, but change has materialized in quite different ways in the two places. Our case studies show considerable variation in local–central power dynamics despite similar overall State forms and organizational frameworks. As Farole et al. (Citation2011, p. 74) observed ‘very similar institutional settings work in different ways in different territories’.

In the Latrobe Valley case, the Victorian government – a government building its reputation on getting the job done and doing what works to achieve its objectives – was the institutional entrepreneur. It used a quasi-independent inquiry to identify the problem as principally about intra-government coordination and embedded agency and crafted a solution – the LVA – that consolidated its infrastructural power over this territory and its population. Its dominance enabled this ‘layering’ of the organizational landscape (Martin & Sunley, Citation2006; Thelen, Citation2003) to achieve its coordination objectives (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). Whilst this represented a consolidation of Weberian statehood – where state power is ‘wielded through highly institutionalized, routinized means’ (Soifer, Citation2008, p. 233), it also recast local power by forging closer ties with progressive forces in the Valley (like the GTLC), while distancing itself from ineffective and disfavoured organizations. Much of the Authority’s subsequent work has focused on the discursive dimension of restoring the State’s legitimacy. Victoria’s authoritative strategy increased the reach of the state into this regional area, and – reflecting the dominance of legitimacy objectives – concentrated effort in the social and political realms while it searched for a new developmental path. There was no place in this strategy to work collaboratively at the regional scale to branch from, or decarbonize, the energy sector. It is also possible, however, that this organizational innovation reinforced, rather than addressed, the underlying problems with trust, regional voice and the elusive qualities associated with institutional thickness that have hampered redevelopment in this area (Weller, Citation2020).

In the Hunter Valley, the local government-led strategy worked locally within the existing organizational framework, building on established relationships. This approach did not involve innovation to the structure of institutions or organizations, nor the exercise of novel powers, but rather focused on the creative re-deployment of existing resources. This local government strategy had more capacity to work cooperatively with the private sector to encourage the repurposing of coal-related sites for new employment-generating industrial activities. The NSW government remained in the background, and whilst it had similar capacities to those of the Victorian government, those powers were not exercised. Since the NSW government’s non-agency still shaped what happened in the region, this underscores the need for a broader understanding of the scope of agency in regional development (Bellandi et al., Citation2021). The greatest risk to locally devised plans was being overtaken by State and Federal initiatives that were likely to tilt the location decisions of firms to other sites.

Both case studies demonstrate that in Australia networks of power with the capacity to shape regional development paths are focused on the State level, over which regional actors have limited power or influence. Formal authority and resources are controlled by State Governments, but they vary in approach. Victoria has a more ‘statist’ orientation, and in Victoria engagement with community-based agencies is more oriented to building legitimacy than in NSW, where engagement is more oriented to economic development projects. Nonetheless, in both jurisdictions State-wide policy orientations have locationally selective implications.

The association between the quality of government and economic development is well established, as is the normative idea that institutional innovation will unleash the potential for growth. There is a growing literature concerned with the understanding the variability of that relationship, but often the contrast is between places with different systems (Evenhuis, Citation2017). This case shows that variations can emerge with the same overall system. It is possible to discern a co-evolution of institutions and economies (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019), since the policy changes described here are attempts to manage the economic shift from coal dependence. But moving from this general objective to the particulars of action shifts the focus to the ways institutional arrangements selectively shape agential powers and regional reconfiguration capacity in response to relatively subtle differences in context (Miörner, Citation2020). These examples also reveal the much wider scope of forms of agency than is admitted by regional studies’ current focus on entrepreneurial actors sensing opportunities for innovation. The institutional innovations described here have been championed by the state in its attempts to manage the contradiction between legitimacy and accumulation in a context that demands restructuring of the established sources of accumulation (Offe, Citation1984). Changes can be triggered by field conditions – such as the crisis of mine fire in Latrobe – but often the change agents are already ‘inside’ the state, although expressing and responding to external conflicts. As Mahoney and Thelen (Citation2009, p. 14) suggest, ‘the basic properties of institutions contain within them possibilities for change’ and what animates change is political, that is ‘the power-distributional implications of institutions’. The case studies also extend the repertoire of modes of agency, while highlighting the tendency for institutional change to reproduce and even reinforce pre-existing institutional scripts – as in the reassertion of central authority in Victoria – and identifies the dilemmas of allegiance among agents who are located in the region but answerable to extra-regional organizations.

Despite their different attempts at institutional innovation, neither of the case study sites has yet attracted new investment in major enterprises with the potential to shift their local economies to new trajectories. The inflexibility of the Australian framework, and the spatial concentration of power in the major cities, inhibits organizational innovations able to deliver both local empowerment and local economic development. These limits on local agency suggest the need for more careful consideration of the geography of situated agency, of the role of the state and of the dynamics of power, in particular the dynamics of central versus local control. In Australia powers over regional development are centred at the State level, which suggests that the regional boundaries most relevant to economic development are State level boundaries.

CONCLUSIONS

The principal aim of this article has been to show that revealing the mechanisms through which regional transformation emerges requires a more explicit focus on organizational forms – in particular, the role of the state and systems of government – and on their roles in wider dynamics of power and influence. By focusing on how power is configured and enacted, this conceptual framework overcomes the dichotomy of agency and structure that persists in the institutional entrepreneurship literature. It also moderates the overly voluntaristic tenor of much of the discussion of agency in regional studies and elsewhere. These findings underscore the need for more precise examinations of power, and its relationship to formal organizational structure, in shaping the mechanisms that drive regional transformation processes.

A crucial question is whether ‘interactions between institutions and industries support or hinder change’ (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019) and under what circumstances the interaction between the evolution of institutions and the evolution of economies produces successful outcomes. In the case of the restructuring of deindustrializing areas – especially those deindustrializing as result of the radical institutional changes inherent in climate mitigation policies – it is assumed that failures to branch to new economic activities are the product of institutional hysteresis (Setterfield, Citation1993) or lock-ins (Hassink, Citation2010). It follows that ‘unlocking’ new developmental pathways hinges on institutional change. However, this paper also suggests a need for further analytical work on the relationship between organizational change and the evolution of deeper institutionalized norms and expectations. To be effective institutional entrepreneurship must restore the competitiveness of economic activities, which means the key question is not about the institutional vehicle but about the strategy for restoring accumulation. If the institutional changes offer no such promise, then their primary purpose lies more in legitimization and the reproduction of state power than in the reinvigoration of the local economy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Muswellbrook Shire Council, which provided them the opportunity to contribute to their planning of the Upper Hunter’s coal closures.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Throughout, the capitalized ‘State’ refers to Australia’s component State territories, while the uncapitalized ‘state’ refers to the abstract concept of the state.

2. Institutions, organizations and discourses are all part of the wider category of ‘structures’, which Sayer (Citation2012, p. 186) defines as ‘relatively durable interlocking, internal social/material relations which have emergent powers, and which can survive change in the membership of their constituents’, although not all social structures are institutions (Hodgson, Citation2006).

3. In any case, embeddedness in multiple institutions complicates the ‘winner’ versus ‘loser’ framing because agents could be losers in one domain but winners in another.

4. Consideration of this Deleuzian form, where power is produced in social situations and indistinguishable from its effects, is beyond the scope of this article. Logistical power, which is of this type, plays out over extended time frames (Neilson, Citation2012).

5. Infrastructural power fits in the Weberian tradition of the state as ‘a set of institutions that exercise control over territory and regulate social relations’ (Soifer, Citation2008, p. 233), where state power is ‘wielded through highly institutionalized, routinized means’ and has formal territorial boundaries. Soifer (Citation2008, p. 234) identifies three forms of infrastructural power: the state’s capability to deploy the resources at its disposal; the territorial reach of their actual deployment; and subnational variations in the embeddedness of the state in civil society.

REFERENCES

- Allen, J. (2003). Lost geographies of power. Blackwell.

- Allen, J., & Cochrane, A. (2007). Beyond the territorial fix: Regional assemblages, politics and power. Regional Studies, 41(9), 1161–1175. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701543348

- Amin, A. (1999). An institutionalist perspective on regional economic development. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 23(2), 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00201

- Amin, A., & Thrift, N. (1995). Institutional issues for the European regions: From markets and plans to socioeconomics and powers of association. Economy and Society, 24(1), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085149500000002

- Ashiem, B., & Gertler, M. (2005). The geography of innovation: Regional innovation systems. In J. Fagerberg & D. Mowery (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of innovation (pp. 1–29). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199286805.003.0011

- Bathelt, H., & Glückler, J. (2014). Institutional change in economic geography. Progress in Human Geography, 38(3), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513507823

- Battilana, J., & D’Aunno, T. (2009). Institutional work and the paradox of embedded agency. In T. Lawrence, R. Suddaby, & B. Leca (Eds.), Institutional work: Actors and agency in institutional studies of organizations (pp. 31–58). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511596605

- Battilana, J., Leca, B., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). How actors change institutions: Toward a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 65–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903053598

- Beer, A., & Lester, L. (2015). Institutional thickness and institutional effectiveness: Developing regional indices for policy and practice in Australia. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2(1), 205–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2015.1013150

- Beer, A., Maude, A., & Pritchard, W. (2003). Developing Australia’s regions: Theory & practice. UNSW Press.

- Bellandi, M., Plechero, M., & Santini, E. (2021). Forms of place leadership in local productive systems: From endogenous rerouting to deliberate resistance to change. Regional Studies, 55(7), 1327–1336. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1896696

- Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2009). Some notes on institutions in evolutionary economic geography. Economic Geography, 85(2), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01018.x

- Boschma, R., & Martin, R. (2010). The aims and scope of evolutionary economic geography. In R. Boschma & R. Martin (Eds.), The handbook of evolutionary economic geography (pp. 3–40). Edward Elgar.

- Brenner, N. (2001). The limits to scale? Methodological reflections on scalar structuration. Progress in Human Geography, 25(4), 591–614. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913201682688959

- Charron, N., Dijkstra, L., & Lapuente, V. (2014). Bringing the regions back in: A study of subnational variation in quality of government within the EU. Regional Studies, 48(1), 48–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.770141

- Cumbers, A., & Mackinnon, A. (2011). Putting ‘the political’ back into the region: Power, agency and a reconstituted regional political economy. In A. Pike, A. Rodríguez-Pose, & J. Tomaney (Eds.), Handbook of local and regional development (pp. 249–258). Routledge.

- Dawley, S. (2014). Creating new paths? Offshore wind, policy activism, and peripheral region development. Economic Geography, 90(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecge.12028

- Dawley, S., MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., & Pike, A. (2015). Policy activism and regional path creation: The promotion of offshore wind in North East England and Scotland. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(2), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu036

- Dellepiane-Avellaneda, S. (2010). Review article: Good governance, institutions and economic development: Beyond the conventional wisdom. British Journal of Political Science, 40(1), 195–224. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123409990287

- DiMaggio, P. J. (1988). Interest and agency in institutional theory. In L. Zucker (Ed.), Institutional patterns and organizations (pp. 3–32). Ballinger.

- Dobbin, F. (1994). Cultural models of organization: The social construction of rational organizing principles. In D. Crane (Ed.), The sociology of culture: Emerging theoretical perspectives (pp. 117–141). Basil Blackwell.

- Drori, G. S., Meyer, J. W., & Hwang, H. (2009). Global organization: Rationalization and actorhood as dominant scripts. In R. Meyer, K. Sahlin, M. Ventresca & P. Walgenbach (Eds.), Institutions and ideology: Research in the sociology of organizations, Vol. 27 (pp. 17–43). Emerald Group. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0733-558X(2009)0000027003

- Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023. https://doi.org/10.1086/231294

- Evenhuis, E. (2017). Institutional change in cities and regions: A path dependency approach. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 10(3), 509–526. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx014

- Farole, T., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2011). Human geography and the institutions that underlie economic growth. Progress in Human Geography, 35(1), 58–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510372005

- Fligstein, N. (2001). Institutional entrepreneurs and cultural frames – The case of the European Union’s single market program. European Societies, 3(3), 261–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616690120079332

- Fraser, N. (1989). Unruly practices: Power, discourse, and gender in contemporary social theory. University of Minnesota Press.

- Fuller, C. (2010). Crisis and institutional change in urban governance. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(5), 1121–1137. https://doi.org/10.1068/a42245

- Garud, R., Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2007). Institutional entrepreneurship as embedded agency: An introduction to the special issue. Organization Studies, 28(7), 957–969. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607078958

- Gertler, M. (2010). Rules of the game: The place of institutions in regional economic change. Regional Studies, 44(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400903389979

- Giddens, A. (1979). Central problems in social theory. Macmillan.

- Gong, H., & Hassink, R. (2019). Co-evolution in contemporary economic geography: Towards a theoretical framework. Regional Studies, 53(9), 1344–1355. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1494824

- Grabher, G., & Stark, D. (Eds.). (1997). Restructuring networks in post-socialism: Legacies, linkages, and localities. Clarendon.

- Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio Gramsci (Q. Hoare & G. N. Smith, Eds. and trans). Lawrence & Wishart.

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Hassink, R. (2005). How to unlock regional economies from path dependency? From learning region to learning cluster. European Planning Studies, 13(4), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310500107134

- Hassink, R. (2010). Locked in decline? On the role of regional lockins in old industrial areas. In R. Boschma & R. Martin (Eds.), Handbook of evolutionary economic geography (pp. 450–468). Edward Elgar.

- Hassink, R., Klaerding, C., & Marques, P. (2014). Advancing evolutionary economic geography by engaged pluralism. Regional Studies, 48(7), 1295–1307. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.889815

- Hodgson, G. (2006). What are institutions? Journal of Economic Issues, 40(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2006.11506879

- Hodgson, G. (2008). The concept of a routine. In M. Becker (Ed.), Handbook of organizational routines (pp. 15–27). Edward Elgar.

- Jepperson, R., & Meyer, J. (2007). Analytical individualism and the explanation of macro social change. In V. Nee & R. Swedberg (Eds.), On capitalism (pp. 273–304). Stanford University Press.

- Jessop, B. (1990). State theory. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Jessop, B. (2001). Institutional re(turns) and the strategic–relational approach. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 33(7), 1213–1235. https://doi.org/10.1068/a32183

- Jessop, B. (2016). State theory. In C. Ansell & J. Torfing (Eds.), Handbook on theories of governance (pp. 71–85). Edward Elgar.

- Jones, M. (2018). The march of governance and the actualities of failure: The case of economic development twenty years on. International Social Science Journal, 68(227–228), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/issj.12169

- Joseph, J. (2004). Foucault and reality. Capital and Class, 28(1), 143–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/030981680408200108

- Langmore, D. (2013). Planning power: The uses and abuses of power in the planning of the Latrobe Valley. Australian Scholarly Publishing.

- Lawrence, T. B., Suddaby, R., & Leca, B. (2011). Institutional work: Refocusing institutional studies of organization. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20(1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492610387222

- Lukes, S. (2005). Power a radical view. Palgrave Macmillan.

- MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., Pike, A., Birch, K., & McMaster, R. (2009). Evolution in economic geography: Institutions, political economy, and adaptation. Economic Geography, 85(2), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01017.x

- MacKinnon, D., Dawley, S., Pike, A., & Cumbers, A. (2019). Rethinking path creation: A geographical political economy approach. Economic Geography, 95(2), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Macleod, G., & Goodwin, M. (1999). Space, scale and state strategy: Rethinking urban and regional governance. Progress in Human Geography, 23(4), 503–527. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913299669861026

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (2009). Explaining institutional change: Ambiguity, agency, and power. Cambridge University Press.

- Mann, M. (1984). The autonomous power of the state: Its origins, mechanisms and results. European Journal of Sociology, 25(2), 185–213. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975600004239

- Marques, P., & Morgan, K. (2018). The heroic assumptions of smart specialisation: A sympathetic critique of regional innovation policy. In A. Isaksen, R. Martin, & M. Trippl (Eds.), New avenues for regional innovation systems-theoretical advances, empirical cases and policy lessons (pp. 275–293). Springer.

- Martin, R. (2000). Institutional approaches in economic geography. In E. Sheppard & T. Barnes (Eds.), A companion to economic geography (pp. 77–94). Blackwell.

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2015). Towards a developmental turn in evolutionary economic geography? Regional Studies, 49(5), 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.899431

- Miörner, J. (2020). Contextualizing agency in new path development: How system selectivity shapes regional reconfiguration capacity. Regional Studies, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1854713

- Neilson, B. (2012). Five theses on understanding logistics as power. Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory, 13(3), 322–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/1600910X.2012.728533

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

- North, D. C. (1994). Economic performance through time. American Economic Review, 84(3), 359–367. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2118057

- O’Neill, P. (1997). Bringing the qualitative state into economic geography. In R. Lee & J. Wills (Eds.), Geographies of economies (pp. 290–301). Arnold.

- Offe, C. (1984). Contradictions of the welfare state (J. Keane, Ed.). Hutchinson.

- Oinas, P., Trippl, M., & Höyssä, M. (2018). Regional industrial transformations in the interconnected global economy. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(2), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy015

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2012). Promoting growth in all regions. OECD Publ.

- Phelps, N. A. (2008). Cluster or capture? Manufacturing foreign direct investment, external economies and agglomeration. Regional Studies, 42(4), 457–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701543256

- Pike, A., MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., Dawley, S., & McMaster, R. (2016). Doing evolution in economic geography. Economic Geography, 92(2), 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1108830

- Powell, W., & DiMaggio, P. (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. University of Chicago Press.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013). Do institutions matter for regional development? Regional Studies, 47(7), 1034–1047. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.748978

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Ketterer, T. (2020). Institutional change and the development of lagging regions in Europe. Regional Studies, 54(7), 974–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1608356

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2009). Better rules or stronger communities? On the social foundations of institutional change and its economic effects. Economic Geography, 82(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2006.tb00286.x

- Sayer, A. (2012). Power, causality and normativity: A critical realist critique of Foucault. Journal of Political Power, 5(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2012.698898

- Setterfield, M. (1993). A model of institutional hysteresis. Journal of Economic Issues, 27(3), 755–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.1993.11505453

- Soifer, H. (2008). State infrastructural power: Approaches to conceptualization and measurement. Studies in Comparative International Development, 43(3–4), 231–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-008-9028-6

- Sotarauta, M. (2016). Leadership and the city: Power, strategy and networks in the making of knowledge cities. Routledge.

- Sotarauta, M., Kurikka, H., & Kolehmainen, J. (2021). Patterns of place leadership: Institutional change and path development in peripheral regions. In M. Sotarauta & A. Beer (Eds.), Handbook on city and regional leadership (pp. 203–225). Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788979689

- Thelen, K. (2003). How institutions evolve: Insights from comparative historical analysis. In J. Mahoney & D. Rueschemeyer (Eds.), Comparative historical analysis in the social sciences (pp. 208–240). Cambridge University Press.

- Tomaney, J. (2014). Region and place I: Institutions. Progress in Human Geography, 38(1), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513493385

- Trippl, M., Grillitsch, M., & Isaksen, A. (2018). Exogenous sources of regional industrial change. Progress in Human Geography, 42(5), 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517700982

- Weller, S. (2012). The regional dimensions of the ‘transition to a low-carbon economy’: The case of Australia’s Latrobe Valley. Regional Studies, 46(9), 1261–1272. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.585149

- Weller, S. (2017). Fast parallels? Contesting mobile policy technologies. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(5), 821–837. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12545

- Weller, S. (2019). Just transition? Strategic framing and the challenges facing coal dependent communities. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 37(2), 298–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654418784304

- Weller, S. (2020). The dialectics of community and government. In A. Campbell, M. Duffy, & B. Edmondson (Eds.), Located research: Regional places, transitions and challenges (pp. 369–386). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Weller, S. (2021). Places that matter: Australia’s crisis intervention framework and voter response. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 14(3), 529–544. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab002

- Weller, S., Beer, A., Porter, S., & Veitch, W. (2020, April). Identifying measures of success for a global best-practice thermal coal mine and thermal coal-fired power station closure – Final report (Consultancy Report prepared for Muswellbrook Shire Council. Mimeo). UNiSA Business.

- Weller, S., Beer, A., Snell, D., Porter, J., & Horne, S. (2021, April). Social and economic adjustment in the Upper Hunter (Consultancy Report prepared for Muswellbrook Shire Council. Mimeo). UNiSA Business.

- Weller, S., & O’Neill, P. (2014). An argument with neoliberalism: Australia’s place in a global imaginary. Dialogues in Human Geography, 4(2), 105–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820614536334

- Weller, S., & Rainnie, A. (2021). Not so ‘smart’? An Australian experiment in smart specialisation. Geographical Research, https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12499

- Whitehead, M. (2003). ‘In the shadow of hierarchy’: Meta-governance, policy reform and urban regeneration in the West Midlands. Area, 35(1), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4762.00105

- Yeung, H. (2005). Rethinking relational economic geography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 30(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2005.00150.x

- Zukauskaite, E., Trippl, M., & Plechero, M. (2017). Institutional thickness revisited. Economic Geography, 93(4), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2017.1331703