ABSTRACT

With the structuring of subnational governance driven primarily by economic goals, an issue that has become increasingly overlooked is that of identity. Drawing on interviews with stakeholders from the Sheffield City Region, the paper builds on Jones and Woods’ framework of 2013 of ‘material’ and ‘imagined’ coherence, demonstrating the ‘imaginary’ challenge of remaking subnational governance in the context of rescaling from regions to city-regions. It shows that historical regional identities can persist even in the absence of associated material components of governance, and that rescaling can create asymmetries between material and imagined coherence, resulting in competing imaginaries that hinder the new subnational arrangements.

INTRODUCTION

A well-established scholarly debate exists in urban and regional studies about the restructuring of economic and political spaces to accommodate the demands of an increasingly networked global economy (Brenner, Citation1998; MacKinnon, Citation2011; Swyngedouw, Citation1997). In contrast to the emphasis placed on ‘regionalism’ during the spatial Keynesian era as a stable subnational policy platform for delivering public services (Storper, Citation1997), the focus since has been on finding a form of metropolitan governance that prioritizes and best serves functionality, competitiveness and innovative capacity (Brenner, Citation2009; Davoudi & Brooks, 2020; Jessop, Citation2000). Fed by neoliberal rationality (Brenner & Theodore, Citation2002), this has given rise to a series of alternative and largely experimental efforts to dismantle and reconceptualize conventional regions into more narrowly defined relational spaces (Harrison, Citation2007; Massey, Citation2011).

While such decentralization experiments have been premised largely on economic arguments, many have noted the importance of identity in developing effective subnational governance arrangements – one that has nevertheless become increasingly overlooked (Rodríguez-Pose & Sandall, Citation2008; Van Houtum & Lagendijk, Citation2001). Some argue that subnational governance structures should reflect the history and identity of communities and thus match community boundaries (e.g., Hooghe et al., Citation2020). This raises important questions in the context of recent governance rescaling initiatives that have seen historical regions dismantled into a mosaic of city-regions, such as top-down devolution-led city-regionalization in the UK. A major assumption of such governance reforms is that the urban institutions, actors and citizens that occupy these new scalar arrangements will cohere, collaborate and coordinate to bring the proposed workings of a new growth model into effect. Yet, this overlooks the importance of established ‘practices’, ‘relationships’ and, importantly, ‘identities’ that reside in places and that impact, ultimately, the delivery of a new approach. Given that regions have been highlighted as sources of identity (Paasi, Citation2001; Citation2011), there are questions as to whether new spatial imaginaries, such as city-regions, will supplant historically and culturally rooted regional identities and foster collaboration at the new level.

This paper contributes to debates on the link between subnational governance, spatial imaginaries, identity and politics (Calzada, Citation2015; Davoudi & Brooks, 2020; Herrschel, Citation2002; Hincks et al., Citation2017; Keating, Citation2014; Paasi, Citation2009; Vallbé et al., Citation2018; Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2013), through conversations with policymakers and entrepreneurs. Drawing on in-depth interviews with stakeholders from the Sheffield City Region (SCR) in the UK, and building on Jones and Woods’ (Citation2013) framework of ‘imagined’ and ‘material’ coherence, the paper explores the challenges of remaking subnational governance spaces. The research question informing this paper is: Why do some spatial imaginaries become institutionalized and accepted while others encounter resistance? We focus on city-region-building in the UK, which in England saw the regional governance tier in the form of regional development agencies (RDAs) abolished by 2012 and replaced by local enterprise partnerships (LEPs) and combined authorities (CAs) via devolution at the city-regional level.

The findings demonstrate the ‘imaginary’ challenge of remaking subnational governance, in our case study exemplified by the asymmetry between imagined and material coherence that sees the SCR imaginary, and by extension the city-regional economic development narrative, rejected by some local authorities. We show that a strong regional identity endures within the hinterland and is used strategically by local elites to legitimize demands for alternative scalar Devolution Deals. The ensuing local tensions and resistance to the city-regional arrangements stymie the prospects for SCR to become socially embedded. While ‘imaginary’, the challenge is real in its consequences, hindering collaboration and participation in city-regional activities.

Our findings contribute to the broader literature on devolution, rescaling and subnational governance, drawing attention to the importance of identity, community imaginaries and imaginary coherence in crafting subnational governance spaces. They highlight the need for devolution to move beyond economic-centric arguments and political preference. We argue that subnational governance arrangements need to exist at a scale that provides imagined coherence and aligns with bottom-up community identities. While the challenges surrounding regional identity in places such as SCR may be seen by policymakers as simple frictions to work through, the extent to which imaginaries become accepted, and the effectiveness of subnational governance, is contingent on subnational arrangements providing a coherent identity to local communities. We discuss the implications for city-regionalism and subnational governance more broadly.

LITERATURE REVIEW

‘Identity’ in regional economic development

The shift from ‘old’ to ‘new’ regionalism has transformed identity discourses and changed the way regions are conceptualized. While endorsed by some as the embodiment of people, cultures and traditions associated with territoriality and ‘historical depth’ (Paasi, Citation2009; Raagmaa, Citation2002; Vainikka, Citation2012; Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2013), regional identities are also promoted as fluid and adaptive to suit external markets and political projects (Allen & Cochrane, Citation2007). Yet, despite the force of globalization processes that continue to shape the way we think about regions, cultural differences (Paasi, Citation2001) and boundaries (Geschiere & Meyer, Citation1998) continue to matter.

Regions are discursive constructs that are constantly produced, shaped, reshaped and removed by policymakers in the processes of institutionalization and de-institutionalization (Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2013). Enforced by the state in the form of subnational policy and institutional restructuring, a process of region-building to construct ‘closer economic, political, security and socio-cultural linkages between states and societies that are geographically proximate’ (Börzel, Citation2012, p. 255) assists in redefining the norms of centre–regional and intra-regional relationships (Brigevich, Citation2018). This links to literature on the role of ‘spatial imaginaries’ used by urban and policy elites to influence political and public opinion of highly selective readings of the form regions should take to promote subnational economic development (Davoudi & Brooks, 2020; Hincks et al., Citation2017; Hoole & Hincks, Citation2020). However, these ignore the presence of ‘actually existing economies’ and pre-existing ideas and imaginaries residing in place that are historically and culturally rooted.

Importantly, spatial imaginaries and (regional) identity are entwined. As ‘deeply held, collective understandings of socio-spatial relations’ (Davoudi, Citation2018, p. 101), spatial imaginaries bring places into existence by fostering a shared sense of identity. The alignment of spatial imaginaries employed in subnational governance and place identity is therefore essential for the effectiveness of subnational governance. Davoudi and Brooks (2020) note the gulf between ‘technocratic imaginaries’ and the ‘imaginaries of communities’ in the context of city-regionalism, highlighting that spatial imaginaries also need to become socially embedded, namely to provide a sense of community and belonging. Similarly, Keating and Wilson (Citation2014) refer to the emergence of ‘regions without regionalism’. It is often these already established spatial scales and identities that are used to challenge new growth models, depending on whether central and local interpretations of the ‘region’ agree or conflict. Where there is resistance, this can be driven by uncertainty and a feared loss of identity of old organizations. Calzada (Citation2018, Citation2019) demonstrates how resistance can lead to grassroots secessionist movements demanding alternative subnational governance and policy arrangements and the ‘right to decide’.

Therefore, ‘identity’ discourse is important in the economic growth or decline of regions (Semian & Chromý, Citation2014; Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2013). Regional identity is defined as a type of ‘collective identity’ and ‘key element’ in the formation of regions (Brigevich, Citation2018). A distinction can be made between the regional identities pursued by regional elites (Semian & Chromý, Citation2014) and those of ordinary citizens (Paasi, Citation2001). The former can be far removed from the awareness (cognitive) and emotional attachment (affective) citizens have for a place (Keating, Citation1998). Furthermore, regional identities are strongly associated with history and ‘images of the past’ that are hugely influential on the patriotism and emotional attachments residents develop towards places (Šerý & Šimáček, Citation2012). Šerý and Šimáček (Citation2012) also remind us of the importance of regional traditions for shaping regional character, and Raagmaa (Citation2002) of the significance of the name of a region. This relates to ‘regional consciousness’ that is about how regions are imagined, understood and spoken about within communities (Vainikka, Citation2012).

Thus, Paasi (Citation2011) further distinguishes between two types of regional identity, namely ‘institutional structures’ and ‘regional consciousness’. This relates to Jones and Woods’ (Citation2013, p. 36) distinction between material coherence, namely ‘the social, economic and political structures and practices that are uniquely configured around a place’, and imagined coherence, which denotes a ‘sense of identity with the place and with each other, such that they constitute a perceived community’ in a way that fosters collective action. These provide a valuable framework for research on devolved regional geographies. The alignment of material and imagined coherence is important not only for national–regional cohesion but also for intra-regional alignment, as a region’s success is heavily contingent on the extent to which the ‘idea’ of a region is shared: (1) amongst regional stakeholders for promoting common interests, shared visions, and mature and trusting relationships; and (2) between regional stakeholders and citizens for promoting a sense of belonging and regional pride, and ensuring their engagement with the region. As Semian and Chromý (Citation2014, citing Deas & Ward, Citation2000) emphasize, ‘success depends on the interlacing of the regional authorities’ development visions, their ‘imposed’ identity of the region, and the community’s sense of belonging … on the willingness of inhabitants to participate in regional development and associated activities’ (p. 265).

Identity is particularly important in the context of devolution and subnational governance rescaling whereby new spatial imaginaries are reified through institutional structures at a new scale. To foster collaboration, the new imaginaries need to become socially embedded and create a shared sense of identity. Yet there is a question as to whether they can replace old imaginaries, especially where the latter are linked to strong historically and culturally rooted identities. We examine these issues in the context of governance rescaling from regions to city-regions.

Subnational governance, scale and identity

The recent decades have seen a move away from centralized forms of governance in a global drive towards devolution (Calzada, Citation2017). This saw powers, authority and resources transferred from national to subnational scales, with governance tiers emerging at the regional, city-regional and metropolitan levels (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2008). The search for the right scalar fix resulted in experimentation, with subnational governance rescaled from metropolitan areas to regions and from regions to city-regions. The latter have become the latest international trend in defining metropolitan spaces and the favoured scale for concentrating subnational economic activity and policy (Calzada, Citation2015; Moisio & Jonas, Citation2017). While the city-region concept remains fuzzy, most definitions refer to an urban core linked by functional ties to its surrounding hinterland (Neuman & Hull, Citation2009). With city-regions regarded as regional engines of growth, much of the rationale behind city-regional governance is rooted in economic- and city-centric growth (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2006), reflecting a shift in the devolution narrative from a bottom-up identity-based to an economic-centric discourse (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2008).

This, however, is problematic as it overlooks the importance of historical and cultural identity rooted in place in providing social cohesion and fostering collaboration in economic development across places. While rescaling subnational governance remakes the material (i.e., institutional structures) at a new scale around new administrative boundaries, this is not automatically followed by the creation of new subnational identities, as previous imaginaries can persist and continue to manifest at the community level. As Paasi (Citation2001, p. 138) notes ‘regional consciousness has no necessary relations to administrative lines drawn by governments’. Thus, even when a region ceases to have an official status linked to formal structures and policy, it may continue to dominate the imaginations of local communities (Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2013), and remain in existence for as long as people believe in and make claim to it (Paasi, Citation2003; Vainikka, Citation2012). This has key implications for subnational governance rescaling. As Healey (Citation2009, p. 834) emphasizes regarding city-regions:

to have significant effects and to endure through changes in intellectual fashions and political attention, the idea of the ‘place’ of a ‘city-region’ has to become embedded in key relations and imaginations within place itself. It has to act as a critical identity shaping force, mobilizing attention locally when neglecting externally. Only then, will a city-region concept have significant effects in generating and maintaining synergies and resistances which will produce distinct place qualities.

However, primacy was given to economic growth targets and to cities, despite early criticism of city-centric economic growth, governance, and reductionism (Morgan, Citation2007). Thus, many cast doubt over the legitimacy of city-regionalization, deemed by some more as political fiat rather than bottom-up localism (Jones, Citation2013). Healey (Citation2009, p. 833), for example, questioned ‘who is doing the “summoning up” of the idea of a city-region, for what purposes, and in what institutional arenas, with what legitimacy and accountability?’ Similarly, Harrison (Citation2010) noted the underemphasis on how city-regions are constructed politically, highlighting a rather ‘compromised city-regionalism’ – centrally orchestrated and constrained by political–administrative boundaries. Rees and Lord (Citation2013) refer to this process as ‘making space’ – a process of inserting the institutional architecture of the new localism within the multi-scalar hierarchy of governance, on the one hand, and as the territorial legitimization of (city-regional) space itself, on the other. They argue that LEPs were, to a great extent, politically reified based on political convenience reflected in the central government’s preference for scale, agglomeration of critical assets, and the continuation of pre-existing partnerships. Likewise, many CAs seeking alternative arrangements to those prescribed by the central government were unsuccessful in securing Devolution Deals (Ayres et al., Citation2018). Indeed, many LEPs were superimposed over pre-existing arrangements, ‘unable to escape the existing territorial mosaic of political–administrative units’ (Harrison, Citation2010, p. 71). The influence of historical partnership legacies therefore cannot be ignored (Ayres & Stafford, Citation2014), as ‘[t]he rescaling of state space never entails the creation of a “blank slate” on which totally new scalar arrangements could be established’ (Brenner, Citation2009, p. 134).

While scholars have highlighted the challenges of subnational governance in various contexts (e.g., Ayres et al., Citation2018; Calzada, Citation2018; Davoudi & Brooks, 2020; Gherhes et al., Citation2020; Keating & Wilson, Citation2014), the issue of identity remains less understood. As territorial identity is not confined within existing politico-administrative boundaries (Lackowska & Mikuła, Citation2018), this has seen demands for independence, autonomy, and even secession in many places across the world. Prominent examples include regional-nations with a strong cultural and historical identities such as Catalonia, the Basque Country, Scotland and the Flemish Region (Calzada, Citation2019; Hooghe et al., Citation2020; Vallbé et al., Citation2018). Recent studies point at the importance of identity in the context of city-regionalization, highlighting significant differences in territorial identities between citizens living in core cities and those living the suburban municipalities and peripheral areas (Lidström & Schaap, Citation2018). In Poland, for example, Lackowska and Mikuła (Citation2018) observed stronger city-regional identities among those living in suburban areas, with a lower regional identity in core cities. Similarly, in Switzerland, Kübler (Citation2018) found that citizens living in the suburbs have stronger intermunicipal attachments than citizens living in the core city, even in the absence of city-regional institutions, arguing that ‘the functional integration of city-regions leads to a rescaling of citizens’ territorial identities’ (p. 64). Similar patterns were observed across Sweden regarding the intermunicipal orientation and identity (Lidström, Citation2018). However, in other cases such as the Barcelona metropolitan area and the Greater Stuttgart city-region, those living in the core cities of Barcelona and Stuttgart have stronger metropolitan and city-regional identity, respectively, than those living in the peripheral and surrounding areas (Vallbé et al., Citation2018; Walter-Rogg, Citation2018). Therefore, varying degrees of material and imagined coherence exist across places, but we are yet to understand the roots and implications for economic development.

In England particularly, Richards and Smith (Citation2015) emphasize how state-driven devolution has been guided by economic rationale that bears limited or no resemblance to shared political, cultural or social identities that people relate to. In a case study of the Greater Cambridge Greater Peterborough (GCGP) LEP – wound up in 2018 – Marlow (Citation2019, p. 140) highlights that ‘these long-standing dysfunctional features of England’s subnational growth approach are “alive and well”’, alluding to identity as part of unresolved tensions inherent in city-regional arrangements. While LEPs and CAs provide ‘material identity’ in their subregions, they also aim to construct new ‘imagined identities’ but as highlighted earlier, regional identities can persist. Therefore, there are questions as to whether this ‘hard’ approach to city-regionalization will ever filter to the ‘soft’ everyday and unite local identities to foster regional development (Beel et al., Citation2016), especially as ‘few localities share Greater Manchester’s economic coherence and cultural identity or its historic strengths in collaborative working across constituent boroughs’ (Lowndes & Gardner, Citation2016, p. 365). Rescaling fragmented historical regions into a mosaic of subregions and city-regions, yet here is a question as to whether these have supplanted historically rooted regional identities.

While it has been shown that citizens develop multiscalar identities (Lackowska & Mikuła, Citation2018; Walter-Rogg, Citation2018), our understanding of the variation in how these manifest across regional and national contexts, and of the implications for subnational governance, remains limited (Lidström & Schaap, Citation2018). Therefore, this paper aims to answer the important question of why some spatial imaginaries become institutionalized and accepted while others encounter resistance. We build on Jones and Woods’ (Citation2013) framework of material and imagined coherence, examining the interplay between identity, scale and subnational governance in the context of rescaling from regions to city-regions in the UK, specifically in a city-region that is part of a wider region with strong historical and cultural roots.

EMPIRICAL FOCUS AND METHODOLOGY

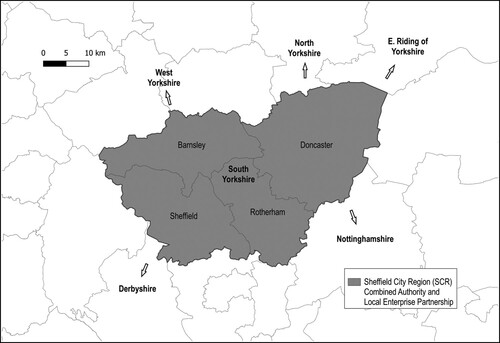

The empirical focus of this paper is SCR, supported by the SCR LEP and SCR CA. Centred around the core city of Sheffield, the LEP and CA span four local authority areas that make up South Yorkshire (), a metropolitan county located in Yorkshire – an historic regional county in the north of England with a population of 5.3 million. SCR resembles a traditionally monocentric city-region, with Sheffield as the economic and employment core (). However, other major towns such as Doncaster are emerging alongside as key growth poles (One NorthEast, Citation2009). Therefore, while drawing on SCR-wide insights, our focus is on the local authorities of Sheffield and Doncaster as the two economic growth drivers in SCR.

Table 1. Sheffield City Region economic statistics

Following a City Deal in 2012 and Growth Deal in 2014, SCR became the second city-region after Greater Manchester to reach a Devolution Deal with central government in 2015. Conditional on electing a metro mayor in May 2017, this would give SCR an extra £30 million per annum over 30 years to boost growth. However, due to heightened tensions between SCR stakeholders in 2016 – including disagreement over the station location of the High Speed 2 (HS2) rail line in the region that ‘exposed antagonistic relations and the perseverance of local politics and diverging interests within the SCR’ (Hoole & Hincks, Citation2020, p. 1597) – a mayor was not elected until 2018. The region then entered a period of further turmoil between 2017 and 2019 when Doncaster and Barnsley began campaigning for devolution to Yorkshire. Moreover, while the SCR ‘brand’ aims to provide a cohesive imaginary and civic identity, it is up against a strong Yorkshire regional identity that is commemorated yearly on Yorkshire Day. This issue has been highlighted elsewhere by Marlow (Citation2019) who showed that the GCGP LEP had ‘retained strong local identity of two distinctive and different medium-size cities with large rural hinterlands’ (p. 143). SCR’s contested monocentric status and the pre-existing regional identity provide an appropriate setting for examining rescaling and the extent to which the new SCR imaginary has been successful in galvanizing local actors and fostering participation in economic development activities.

To examine this, we adopted a qualitative methodological approach. In total, 34 in-depth interviews were conducted between November 2015 and December 2018 with six different stakeholder groups: local authority officials (11), entrepreneurs (12), SCR LEP representatives (six), chamber of commerce representatives (two), SCR CA representatives (two) and one civic organization representative (). Most interviews were conducted in Sheffield and Doncaster, with a small number of interviews from Rotherham, Barnsley and Bassetlaw to gain a wider perspective. The interviews were typically 60–90 minutes in length, primarily face to face, and recorded with interviewee consent. Interview transcripts were thematically coded based on prior theoretical assumptions and novel ideas or contradictions that emerged from the data. This followed an iterative process of reasoning involving ‘deductive’ and ‘inductive’ techniques until ‘circularity’ within the research process was reached (Bryman, Citation2012). The codes were grouped based on similarity and revised and refined through constant comparison with the data and key literature, yielding the final themes presented in the next section.

Table 2. Profiles of the respondents.

FINDINGS

The findings are presented in relation to three overarching themes which together highlight an asymmetry between material and imagined coherence in SCR and the persistence of a regional consciousness. First, SCR is characterized by a weak imagined coherence that fosters local disengagement and perceptions of inter-place rivalry. Second, the importance attributed to core cities in Devolution Deals creates a fragile material coherence, generating local governance tensions. Third, this has seen the resurgence of a regional identity discourse at the local level, prompting some local authorities to use regional identity strategically to push for a regional Devolution Deal.

A weak imagined coherence fosters local disengagement and inter-place rivalry perceptions

The interviews highlighted that, rather than providing a new identity for local communities to coalesce around, the SCR brand is in fact a source of tensions at the local level. Criticism levied towards SCR for being an ‘artificial construct’ (INT17-LA) that local communities do not identify with revealed a weak imagined coherence. As a stakeholder explained, ‘Just the term “city-region” … not everyone wants to live in cities. … Not a lot of people live in cities, actually’ (INT4-LA), highlighting that the city-centric identity does not resonate with hinterland communities. Moreover, the name of the city-region itself is problematic for some local communities and a hindrance to local engagement, as the core city-centric identity fails to represent all localities:

What’s it called? Sheffield, not South Yorkshire. … What does the Sheffield LEP represent? It might just be an awkward typo, but it still carries on through.

(INT22-ENT)

If the name of the city-region was the Barnsley, Doncaster, Rotherham and Sheffield City Region … it might be different.

(INT12-LEP)

If you look at devolution … it just looks like Sheffield getting bigger.

(INT21-ENT)

[Funding] should be given to each individual town … because if it’s done through Sheffield, Sheffield keeps it all and Rotherham, Doncaster, other towns like that will see hardly any of it because they’ll focus on particular projects that are ‘by chance’ based around Sheffield and the growth of Sheffield as a city.

(INT27-ENT)

The concern would be that somebody like Sheffield, that perhaps is bigger, vibrant, more figures, more turnover, more people, would get more resources than perhaps a one-man-band in Doncaster.

(INT26-ENT)

My town, for my sector, is still third in the pecking order.

(INT22-ENT)

I would never speak of the Sheffield regional bit as the first point of contact. … I would just think of the likes of Business Doncaster. … I almost feel as though Doncaster and Sheffield are rivals, and any other town, place is a rival. … There’s always been this funny relationship between Sheffield and Doncaster so that’s why I’d probably try to avoid it.

(INT29-ENT)

We run an economic survey for Doncaster every quarter. … We went from being part of the Sheffield City Region project with City Region branding on it to doing exactly the same project with the same level of resource pretty much, put a Doncaster badge on it and then just said we’d share the data, and the response rate tripled … because people are responding to a Doncaster thing, not a City Region thing.

(INT8-CC)

Doncaster feels increasingly divorced or disengaged from Sheffield City Region … the City Region feels increasingly irrelevant to us. … People don’t talk city-region to us. They talk about Doncaster, they talk about Yorkshire, they talk about the UK.

(INT8-CC)

In hindsight, the local stakeholders admitted that not enough effort has been dedicated to obtaining civic buy-in and building the SCR brand in the public perception:

There’s quite a lot of apathy anyway and … lack of engagement from the public on Sheffield City Region deal because I don’t think people will see it as touching their life particularly. And I don’t think we’ve done a great job as individual authorities and collectively through the City Region to engage local people with it. I mean, it’s difficult enough as officers to understand how it all works and to be able to explain the benefits and to accept that there are overall benefits and it is overall a good thing for us, without being able to sell it to the public.

(INT7-LA)

I suppose what hasn’t gone so well is the process of doing the deal didn’t create the level of in-depth attitudinal change that we thought it might have done … .

(INT18-CA)

The result is a hinterland that feels disconnected from the city-regional imaginary. As an interviewee emphasized, in SCR ‘there’s still almost a divide that needs to be broken before it can be fully embraced’ (INT25-ENT). Unlike other established city-regions, such as Greater Manchester, SCR does not benefit from ‘a more cohesive civic identity’ (INT4-LA). Instead, some localities have retained a strong regional identity: ‘Yorkshire has more of an identity than Sheffield City Region … so people are going to relate more to Yorkshire’ (INT17-LA). This indicates the existence and persistence of multiscalar identities (Lackowska & Mikuła, Citation2018) within the city-regional periphery that connect to the wider region, the consequences of which are unpacked in the next sections.

A fragile material coherence: core–periphery polarization and local governance tensions

Further to the weak imagined coherence, a key issue is that the SCR governance setting polarizes economic development interests, leading to local governance tensions as opposed to fostering collaboration between localities. Two interviewees emphasized:

[The devolution] doesn’t give the impression of everyone working together.

(INT21-ENT)

[The LEP] just doesn’t feel as joined up as it probably ought to be.

(INT19-ENT)

There’s always been a reluctance of the coalfields to work with Sheffield. Sheffield’s always really been seen as the bad brother, and Barnsley, Doncaster and Rotherham are the coalfield areas, but the problem is they don’t work together either. There doesn’t seem to be a regional perception that the only way to get the region going is there’s got to be integration and interconnection between the local authorities.

(INT24-ENT)

Prior to Roslyn … [Doncaster] was controlled by an English Democrat. … Because he was anti-South Yorkshire, instead of looking to South Yorkshire as it had historically done as an old mining, rail, industrial city … he was trying to get it to look the other direction, eastwards, looking at trying to connect Doncaster with Hull, Scunthorpe, and Newark.

(INT22-ENT)

Sheffield naturally sees itself in any city-region as the centre of gravity and there’s a lack of humbleness and humility perhaps not from any one individual but just the challenge when you’re looking at devolution from a city-region concept rather than a region concept. It’s lack of equity … what would be perceived.

(INT1-LA)

Doncaster is a bit on the edge of the City Region … further away from Sheffield, which means it doesn’t have quite the same impact on Doncaster as it does, say, somewhere like Rotherham in terms of drawing away economic growth.

(INT33-LEP)

Probably a key weakness is the fact that Doncaster is overshadowed by Sheffield and also Leeds … so quite often it may be overlooked in terms of where the government may want to invest in schemes or external businesses may want to come and invest.

(INT31-LEP)

There are some tensions around the role of core cities versus mid-sized cities like Doncaster. … There’s an assumption in many quarters at national level and regionally that, if you consolidate all your assets and support to the core city, by definition everybody else benefits, but city-regions are different. Sheffield City Region is polycentric. Doncaster increasingly is punching its weight in terms of the growth it’s supporting in the Sheffield City Region, so do government adequately recognise the role of mid-sized cities as well as core cities? Because we’re always going to be up against it … but we’ve got our own large economy with our own distinctive offer. We’ve got assets that many core cities can’t compete with. … It shouldn’t be polarised and it shouldn’t be seen as one thing or the other.

(INT32-LA)

In terms of commuter flows, we look to the West and we look to the East, so Wakefield, Leeds, but also North Lincolnshire, Humberside. We’ve got strong economic connections there. So yeah, we are in the SCR camp and obviously working as hard as we can to make that a success, but we’ve also got major economic ties and great potential … [and] we need to be nurturing those global trade flows beyond the SCR. … That’s a real big challenge for Doncaster.

(INT32-LA)

The fragility of the material coherence is also visible in the economic geography of the city-region, specifically the interconnectedness – or lack thereof – of city-regional localities. This is seen to stymie inter-local economic practices and to limit the economic development potential of the peripheries:

I can’t get a train from Barnsley to Doncaster or Rotherham. It doesn’t even exist. They closed the lines down in the 60s … so I can’t even improve the line speed because it doesn’t even exist. … That’s an impediment to local growth, because actually, if you could then connect up with some of those core cities, that would make a huge difference for learning potential, for growth, aspiration, et cetera.

(INT10-LA)

Sheffield still struggles to deliver and collaborate with the wider region … that’s where things like HS2 has been very fractious in the Sheffield City Region.

(INT10-LA)

the fact that you’ve got … four main local authorities, all of the same political disposition, that cannot agree on black and white stuff is a farce. … Couldn’t agree on HS2 station location, we couldn’t agree on devolution … .

(INT8-CC)

Using regional identity strategically: the push for ‘One Yorkshire’

In the context of a weak imagined coherence, since 2017 SCR has been involved in a campaign for Yorkshire-wide devolution. This came about when Doncaster and Barnsley pledged their allegiance, together with 16 other local authorities across the region and the Mayor of SCR, to devolution for Yorkshire. Meanwhile, Sheffield and Rotherham continued in their efforts to push a SCR Devolution Deal over the line. While in part fed by diverging local identities and resistance to city-centric policies, as outlined in the previous sections, also relevant to this change of direction was a resurgence of ‘regionalism’ following the 2014 Scottish independence referendum that brought to the fore the possibility for alternative devolution arrangements as a solution to London-centrism. This desire to explore alternative approaches to growth was reinforced by the 2016 Brexit vote:

The world is now very different to the world that we agreed a devolution deal in 2015 … leaving the European Union … brings new relatives, new challenges, new difficulties … there’s not an appetite just to blindly sign up to what was agreed in 2015 … .

(INT4-LA)

A really important point … missed in devolution, is the connection with people … we need to do something that is for and with people … add to it the post-Brexit world about scale and brand and identity and the need to articulate a voice, and you’ve got the genesis of the One Yorkshire proposition.

(INT5-LA)

if you bring this down to a people scale, because we’re dealing with people who live in places ultimately, I think they struggle to understand what the Sheffield City Region is, because really it’s just an economic geography that’s been drawn up to fit around the other bits.

(INT7-LA)

We’ve got our eyes on what we see as the bigger benefits, which would come through the agglomeration of having a Yorkshire area … Yorkshire has got international significance … so we see it as something that is a marketable position … as opposed to something like a South Yorkshire brand.

(INT7-LA)

Moreover, some interviewees were of the view that working together at a larger scale would strengthen their national position and influence. This was especially the case for supporters in SCR that had witnessed the city-region’s weakening position and a growing uncertainty over the future of the existing arrangement. Once one of the front runners of devolution, since 2016 SCR has been falling behind other city-regions in its devolution journey due to the delay in electing a metro mayor and signing the SCR Devolution Deal. In this context, interviewees in Doncaster suggested that devolution to Yorkshire would increase their influence over government for obtaining the kind of Devolution Deal that was wanted locally – or at least in the peripheries – as well as enhance their competitiveness relative to other areas bidding for devolution funds and powers:

[For] allowing those conversations with central government, scale helps. That’s why we’re favouring the Yorkshire side of things … it does give you the kind of massing and scale to be able to have a discussion and a conversation with central government around strategic things.

(INT7-LA)

If we’re working together with democratic legitimacy over 5.3 million people, which is the size of Scotland, then there’s a better chance of influencing and lobbying and getting the deal that we need.

(INT4-LA)

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The findings show that, in SCR, devolution-led city-regionalization is not supported by a widely shared city-regional identity and a strong governance framework that fosters collaboration. We show that the formation of SCR failed to seek and obtain the legitimacy of local communities, with some localities feeling trapped in a city-regional narrative to which they do not feel they belong. A weak imagined coherence fosters disengagement and perceptions of inter-place rivalry, with some hinterland communities feeling disconnected from the city-regional narrative and contesting the SCR imaginary. The city-centric SCR brand is a barrier to constructing a shared city-regional identity, being inconsistent with the community imaginary and perceived to disadvantage city-regional peripheries. Moreover, the material coherence provided by the LEP and CA is fragile, being weakened by a city-centric growth discourse perceived to foster core–periphery polarization. The ensuing local governance tensions further weaken the precarious SCR imaginary, hindering collaboration and participation in city-regional affairs. Instead, a regional Yorkshire identity endures in the hinterland, reflecting the persistence of regional consciousness.

These dynamics led to the resurgence of regional identity discourse locally, prompting some local authorities to leverage regional identity to push forward the One Yorkshire agenda – a region-wide Devolution Deal proposition constructed around the argument that the wider region provides superior economic development opportunities for local communities (i.e., beyond SCR borders) and better reflects local identities. The dominance of economic arguments in favour of regional devolution highlights that identity is, however, secondary to the economic discourse (Hoole & Hincks, Citation2020; Rodríguez-Pose & Sandall, Citation2008), being used strategically by local elites to legitimize demands for alternative governance structures. Thus, One Yorkshire is partly a response to city-centric policies that are seen to marginalize city-regional peripheries. Support for One Yorkshire can be seen as an attempt to challenge an existing centrally led devolution model (Hoole & Hincks, Citation2020) defined in mainly ‘functional’ terms towards adopting a more ‘bottom-up’, place-relevant approach based on identity and ‘political’ regionalism.

While SCR has recently managed to secure a Devolution Deal, the underlying challenges highlighted in this paper cannot be overlooked. Beyond the One Yorkshire devolution proposition supported by the Yorkshire Party, identity-driven political claims have seen the rise of political parties claiming for regional independence, like the Northern Independence Party – similar to other places in Europe and around the world where territorial identity and the demand for self-rule have been mobilized to influence subnational governance (Calzada, Citation2019; Hooghe et al., Citation2020). Given the historical roots of such tensions and continued opposition to the city-regional narrative, the bottom-up demand for regional devolution is rather a ‘deferred problem’ (Hoole & Hincks, Citation2020, p. 16), with issues likely to persist and re-emerge in the future. Meaningful devolution therefore needs to transcend an obsession with scale and economic centricity (Gherhes et al., Citation2020) and seek to better align with bottom-up community imaginaries. Otherwise, it risks fuelling identity-based politics, destabilizing subnational arrangements as opposed to fostering local collaboration.

Therefore, our paper demonstrates the ‘imaginary’ challenge of remaking subnational governance based on political convenience and the top-down imposition of centrally preferred governance scales (Rees & Lord, Citation2013). It shows that historically and culturally rooted regional identities cannot be simply remoulded around relatively recent technocratic conceptualizations of city-regions as functional economic geographies. Building on Jones and Woods (Citation2013) framework, we demonstrate that politically driven rescaling can create asymmetries between material and imagined coherence, and show how competing imaginaries can hinder subnational arrangements. Specifically, historical (regional) identities can persist and continue to provide a sense of belonging to local communities, outside of new administrative boundaries imagined by political elites. In our case study, a city-centric narrative perceived as exclusionary exacerbates the ‘imaginary’ challenge, generating local tensions and resistance. In the UK, the challenge is arguably compounded by the constant remaking of subnational governance, which has not allowed sufficient time for new imaginaries to become established and accepted. Indeed, institution-building and public acceptance of new institutions is a slow and drawn-out process (Harding, Citation2020). In some cases, such as Manchester City Region – hailed as an exemplar of city-regionalism – efforts to build city-regional institutions span decades (Deas, Citation2014). This, however, is not the case in city-regions such as SCR which, as relatively new propositions, are not supported by similar histories of collaborative working and image-making efforts that are essential to legitimizing new spatial imaginaries (Lowndes & Gardner, Citation2016; Van Houtum & Lagendijk, Citation2001). Old, or already lived, imaginaries can thus be perceived to provide better governance alternatives. Given that city-regionalism is in a fledgling state, the ‘imaginary’ challenge may be merely an effect of evolutionary tensions that such places undergo in establishing their identity.

However, even in well-established city-regions with a long tradition of city-regional cooperation, such as Greater Stuttgart which has experienced metropolitan governance for decades, surrounding areas have not developed the same strong city-regional identity and attachment as those living in the core city (Walter-Rogg, Citation2018). This raises questions over whether identity formation is merely a question of time. In fact, Chojnicki (Citation1993) argues in the context of regionalism that the existence of a common regional identity should be a prerequisite for the institutionalization of a region. This common identity fosters place attachment and springs a sense of community (Lackowska & Mikuła, Citation2018), which are critical to fostering cohesion and civic engagement (Kübler, Citation2018). Importantly, the rescaling of governance space is not automatically followed by a rescaling of territorial identity. Thus, Chojnicki’s (Citation1993) argument can be extended to any spatial scale, namely that the institutionalization of a spatial scale ought to be supported by the pre-existence of a community identity that confers imagined coherence to that scale. To paraphrase Davoudi and Brooks (2020), a spatial imaginary can only become socially embedded when a significant number of people imagine themselves as belonging to that community, regardless of the scale involved, be it regional, city-regional, or metropolitan.

The implications extend beyond SCR and the English context. Our case study highlights the consequences of top-down ‘manufactured’ scalar fixes that clash with community imaginaries in the context of city-regionalism. However, asymmetries between material and imagined coherence can manifest in different ways across places. For example, they can be more extreme, such as demands for territorial autonomy or independence as seen in places across Europe and around the world (Calzada, Citation2018; Rodríguez-Pose & Sandall, Citation2008) or, as our case study illustrates, ‘softer’ demands for devolution at a scale that is coherent with the community imaginary. Thus, not all demands for devolution are driven by secessionist aspirations. Unlike places such as Catalonia, Basque Country, Corsica, and Scotland, recognized widely as regional-nations, localities in SCR and Yorkshire are not advocating for independence but for a more constructive and inclusive subnational governance framework. These peripheral localities want a voice and for that to be recognized in governance structures, as current arrangements are perceived to marginalize that voice. Our case study thus provides an additional perspective of a region that is not as prominent as those previously studied – what we might consider ordinary – thereby illustrating that the issue of territorial identity is pervasive and can influence the effectiveness of governance at different scales, and that tensions are likely to arise where the material and the imagined are not mutually reinforcing.

While geographically focused on SCR, our paper yields key implications for the devolution agenda in the UK and beyond. First, it challenges the way top-down city-regionalism has been imposed across England, particularly in regions that similarly are made up of localities with distinct identities (Lemprière & Lowndes, Citation2019). As Van Houtum and Lagendijk (Citation2001, p. 765) emphasize, ‘proximity is not a cause for interaction’, and therefore bundling localities around core cities based on spatial proximity and economic functionality rationales does not provide a solid foundation for collaborative local governance. In regions with strong historical and cultural roots, politically driven city-regionalism can create what Deas and Giordano (Citation2003) refer to as competing geographies of identity. The dominance of core cities can be perceived as encroaching on local identities, with hinterlands subsumed to an overpowering core. This stifles collaboration between the urban core(s) and their hinterlands, which is essential to the functioning of a city-region (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2008). However, where regional identity is fragmented and strong subregional or local identities exist, establishing arrangements at the regional scale can be equally challenging (Lemprière & Lowndes, Citation2019). While the challenges surrounding regional identity may be seen by policymakers as simple frictions to work through, the extent to which imaginaries become accepted, and the effectiveness of subnational governance, is contingent on subnational arrangements providing a coherent identity to local communities (Davoudi & Brooks, 2020). For example, efforts to establish city-regional arrangements in places where strong city-regional or intermunicipal identities already exist (e.g., Kübler, Citation2018; Lackowska & Mikuła, Citation2018), are unlikely to encounter the level of opposition seen in SCR. If imposed, spatial imaginaries can create a disjuncture with bottom-up community identities which goes against the constructive delivery of these economic and social imaginaries of place.

There is therefore a need to move beyond economic-centric devolution. At a time of heightened challenges relating to Brexit and the ongoing Covid-19 crisis, and a pledge from central government to connect local recovery with ‘levelling up’, more than ever before our findings emphasize the importance of taking local and regional identity discourse in local economic development policy seriously. If further reforms – as anticipated in the recently promised publication of a landmark Levelling Up White Paper in late 2021 – are to be about ‘strengthening community and local leadership, restoring pride in place, and improving quality of life in ways that are not just about the economy’ (HM Government, Citation2021, p. 30), they will need to foster collaboration across places and better reflect bottom-up identities and preferences for scale. This will help enhance subnational governance capacity and capability for improving the effectiveness of local areas to respond.

Our case study contributes to the broader literature on devolution, subnational governance, scale and identity (Calzada, Citation2017; Davoudi & Brooks, 2020; Keating & Wilson, Citation2014; Vallbé et al., Citation2018), demonstrating the importance of identity and community imaginaries in crafting subnational governance spaces. It highlights that imagined communities can exist and persist even in the absence of associated material components of governance. While the material can be endlessly remade, imaginaries lag behind and can create resistance to new arrangements that do not align with community identities. Moreover, as material and imagined coherence can exist at different scales, asymmetries can exist between subnational governance arrangements and the territorial identities that spring community imaginaries. These risks creating, (re)surfacing or exacerbating local tensions, thus undermining rather than facilitating local economic development, and can become a source of local tensions and legitimize identity-based political claims for territorial autonomy.

Given the diverse geographies of city-regions and other types of subnational and multi-scalar governance arrangements, as is exemplified within SCR but the consequences of which are relevant more broadly in different contexts, nationally and internationally, there is scope for future research to expand on our study and examine these dynamics in other contexts and at different scales. Similar identity-related issues are apparent in other places across the world like the Basque Country, Catalonia, and Galicia in Spain (Calzada, Citation2019; Vallbé et al., Citation2018), the Greater Stuttgart city-region in Germany (Walter-Rogg, Citation2018), the Flemish Region of Belgium, Quebec (Canada), as well in places across Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Panama and Venezuela, the latter of which have seen increased mobilization of territorial identity and demand for self-rule among indigenous communities (Hooghe et al., Citation2020). Future studies can explore the interplay between scale, governance, and identity within and between multi-scalar arrangements. Particularly, polycentric city-regions, polycentric urban regions, non-core city-regions, and places that are part of more than one subnational arrangement (e.g., places that are part of two city-regions) provide interesting case studies for additional insights into the dynamics between identity and subnational governance. Finally, given ongoing identity-fuelled territorial tensions across the world, future studies can examine how other places have sought to build materially and imaginarily coherent subnational governance spaces and the strategies and approaches employed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions, which helped to improve the manuscript throughout the review process.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Sheffield has the lowest gross value added (GVA) per capita of all other core city-regions in England.

REFERENCES

- Allen, J., & Cochrane, A. (2007). Beyond the territorial fix: Regional assemblages, politics and power. Regional Studies, 41(9), 1161–1175. doi:10.1080/00343400701543348

- Ayres, S., Flinders, M., & Sandford, M. (2018). Territory, power and statecraft: Understanding English devolution. Regional Studies, 52(6), 853–864. doi:10.1080/00343404.2017.1360486

- Ayres, S., & Stafford, I. (2014). Managing complexity and uncertainty in regional governance networks: A critical analysis of state rescaling in England. Regional Studies, 48(1), 219–235. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.672727

- Beel, D., Jones, M., & Rees Jones, I. (2016). Regulation, governance and agglomeration: Making links in city-region research. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 3(1), 509–530. doi:10.1080/21681376.2016.1255564

- Börzel, T. A. (2012). Do all roads lead to regionalism? In T. A. Börzel, L. Goltermann, & K. Striebinger (Eds.), Roads to regionalism: Genesis, design, and effects of regional organizations (pp. 273–286). Routledge.

- Brenner, N. (1998). Global cities, glocal states: Global city formation and state territorial restructuring in contemporary Europe. Review of International Political Economy, 5(1), 1–37. doi:10.1080/096922998347633

- Brenner, N. (2009). Urban governance and the production of new state spaces in Western Europe, 1960–2000. In B. Arts, A. Lagendijk, & H. van Houtum (Eds.), The disoriented state: Shifts in governmentality, territoriality and governance (pp. 41–77). Springer.

- Brenner, N., & Theodore, N. (2002). Cities and the geographies of ‘actually existing neoliberalism’. Antipode, 34(3), 349–379. doi:10.1111/1467-8330.00246

- Brigevich, A. (2018). Regional identity and support for integration: An EU-wide comparison of parochialists, inclusive regionalist, and pseudo-exclusivists. European Union Politics, 19(4), 639–662. doi:10.1177/1465116518793708

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Calzada, I. (2015). Benchmarking future city-regions beyond nation-states. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2(1), 351–362. doi:10.1080/21681376.2015.1046908

- Calzada, I. (2017). Metropolitan and city-regional politics in the urban age: Why does ‘(smart) devolution’ matter? Palgrave Communications, 3(1), 17094. doi:10.1057/palcomms.2017.94

- Calzada, I. (2018). Metropolitanising small European stateless city-regionalised nations. Space and Polity, 22(3), 342–361. doi:10.1080/13562576.2018.1555958

- Calzada, I. (2019). Catalonia rescaling Spain: Is it feasible to accommodate its ‘stateless citizenship’? Regional Science Policy & Practice, 11(5), 805–820. doi:10.1111/rsp3.12240

- Centre for Cities. (2021). City by city. https://www.centreforcities.org

- Chojnicki, Z. (1993). The region in a perspective of change. Regional and Local Studies (University of Warsaw), 67–74.

- Davoudi, S. (2018). Imagination and spatial imaginaries: A conceptual framework. Town Planning Review, 89(2), 97–107. doi:10.3828/tpr.2018.7

- Davoudi, S. (2019). Imaginaries of a ‘Europe of the regions’. Transactions of the Association of European Schools of Planning, 3(2), 85–92. doi:10.24306/TrAESOP.2019.02.001

- Davoudi, S., & Brooks, E. (2021). City-regional imaginaries and politics of rescaling. Regional Studies, 55(1), 52–62. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1762856

- Deas, I. (2014). The search for territorial fixes in subnational governance: City-regions and the disputed emergence of post-political consensus in Manchester, England. Urban Studies, 51(11), 2285–2314. doi:10.1177/0042098013510956

- Deas, I., & Giordano, B. (2003). Regions, city-regions, identity and institution building: Contemporary experiences of the scalar turn in Italy and England. Journal of Urban Affairs, 25(2), 225–246. doi:10.1111/1467-9906.t01-1-00007

- Deas, I., & Ward, K. G. (2000). From the ‘new localism' to the ‘new regionalism'? The implications of regional development agencies for city-regional relations. Political Geography, 19(3), 273–292.

- Geschiere, P., & Meyer, B. (1998). Globalization and identity: Dialectics of flow and closure. Introduction. Development and Change, 29(4), 601–615. doi:10.1111/1467-7660.00092

- Gherhes, C., Brooks, C., & Vorley, T. (2020). Localism is an illusion (of power): the multi-scalar challenge of UK enterprise policy-making. Regional Studies, 54(8), 1020–1031. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1678745

- Giovannini, A. (2016). Towards a ‘new English regionalism' in the North? The case of Yorkshire first. The Political Quarterly, 87(4), 590–600.

- Harding, A. (2020). Collaborative regional governance: Lessons from Greater Manchester (IMFG Papers No. 48). University of Toronto, Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance.

- Harrison, J. (2007). From competitive regions to competitive city-regions: A new orthodoxy, but some old mistakes. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(3), 311–332. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbm005

- Harrison, J. (2010). Networks of connectivity, territorial fragmentation, uneven development: The new politics of city-regionalism. Political Geography, 29(1), 17–27. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2009.12.002

- Haughton, G., Deas, I., Hincks, S., & Ward, K. (2016). Mythic Manchester: Devo Manc, the Northern Powerhouse and rebalancing the English economy. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 9(2), 355–370. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsw004

- Healey, P. (2009). City regions and place development. Regional Studies, 43(6), 831–843. doi:10.1080/00343400701861336

- Herrschel, T. (2002). Governance of Europe’s city regions: Planning, policy, and politics. Routledge.

- Hincks, S., Deas, I., & Haughton, G. (2017). Real geographies, real economies and soft spatial imaginaries: Creating a ‘more than Manchester’ region. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 642–657. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12514

- HM Government. (2021). Queen’s Speech 2021: background briefing notes. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/queens-speech-2021-background-briefing-notes

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Schakel, A. (2020). Multilevel governance. In D. Caramani (Ed.), Comparative politics (pp. 193–210). Oxford University Press.

- Hoole, C. & Hincks, S. (2020). Performing the city-region: Imagineering, devolution and the search for legitimacy. Environment and Planning A, 52(8), 1583–1601. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20921207.

- Jessop, B. (2000). From the KWNS to SWPR. In G. Lewis, S. Gewirtz, & J. Clarke (Eds.), Rethinking social policy (pp. 171–184). Sage.

- Jones, M. (2013). It's like deja vu, all over again. In M. Ward, & S. Hardy (Eds.), Where next for local enterprise partnerships? (pp. 85–94). Smith Institute.

- Jones, M., & Woods, M. (2013). New localities. Regional Studies, 47(1), 29–42. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.709612

- Keating, M. (1998). The new regionalism in Western Europe: Territorial restructuring and political change. E. Elgar.

- Keating, M. (2014). Territorial imaginations, forms of federalism and power. Territory, Politics, Governance, 2(1), 1–2. doi:10.1080/21622671.2014.883246

- Keating, M., & Wilson, A. (2014). Regions with regionalism? The rescaling of interest groups in six European states. European Journal of Political Research, 53(4), 840–857. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12053

- Kübler, D. (2018). Citizenship in the fragmented metropolis: An individual-level analysis from Switzerland. Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(1), 63–81. doi:10.1111/juaf.12276

- Lackowska, M., & Mikuła, Ł. (2018). How metropolitan can you go? Citizenship in Polish city-regions. Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(1), 47–62. doi:10.1111/juaf.12260

- Lemprière, M., & Lowndes, V. (2019). Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 34(2), 149–166. doi:10.1177/0269094219839021

- Lidström, A. (2018). Territorial political orientations in Swedish city-regions. Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(1), 31–46. doi:10.1111/juaf.12244

- Lidström, A., & Schaap, L. (2018). The citizen in city-regions: Patterns and variations. Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(1), 1–12. doi:10.1080/07352166.2017.1355668

- Lowndes, V., & Gardner, A. (2016). Local governance under the conservatives: Super-austerity, devolution and the ‘smarter state’. Local Government Studies, 42(3), 357–375. doi:10.1080/03003930.2016.1150837

- MacKinnon, D. (2011). Reconstructing scale: Towards a new scalar politics. Progress in Human Geography, 35(1), 21–36. doi:10.1177/0309132510367841

- Marlow, D. (2019). Local Enterprise Partnerships: Seven-year itch, or in need of a radical re-think? – Lessons from Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, UK. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 34(2), 139–148. doi:10.1177/0269094219839335

- Massey, D. (2011). A counterhegemonic relationality of place. In E. McCann & K. Ward (Eds.), Mobile urbanism: Cities and policymaking in the global age (pp. 1–14). University of Minnesota Press.

- Moisio, S., & Jonas, A. E. G. (2017). City-regions and city-regionalism. In A. Paasi, J. Harrison, & M. Jones (Eds.), Handbook on the geographies of regions and territories (pp. 285–297). Edward Elgar.

- Morgan, K. (2007). The polycentric state: New spaces of empowerment and engagement? Regional Studies, 41(9), 1237–1251. doi:10.1080/00343400701543363

- Neuman, M., & Hull, A. (2009). The futures of the city region. Regional Studies, 43(6), 777–787. doi:10.1080/00343400903037511

- One North East. (2009). City relationships: Economic linkages in Northern city regions Sheffield City Region. https://www.centreforcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/City-Relationships-Sheffield.pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2006). Competitive cities in the global economy. OECD Territorial Review. https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/37839981.pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). Enhancing productivity in UK core cities: connecting local and regional growth. https://www.oecd.org/unitedkingdom/enhancing-productivity-in-uk-core-cities-9ef55ff7-en.htm

- Paasi, A. (2001). Europe as a social process and discourse: Considerations of place, boundaries and identity. European Urban and Regional Studies, 8(1), 7–28. doi:10.1177/096977640100800102

- Paasi, A. (2003). Region and place: Regional identity in question. Progress in Human Geography, 27(4), 475–485. doi:10.1191/0309132503ph439pr

- Paasi, A. (2009). The resurgence of the ‘region’ and ‘regional identity’: Theoretical perspectives and empirical observations on regional dynamics in Europe. Review of International Studies, 35(S1), 121–146. doi:10.1017/S0260210509008456

- Paasi, A. (2011). The region, identity, and power. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 14, 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.011

- Raagmaa, G. (2002). Regional identity in regional development and planning. European Planning Studies, 10(1), 55–76. doi:10.1080/09654310120099263

- Rees, J., & Lord, A. (2013). Making space: Putting politics back where it belongs in the construction of city regions in the North of England. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 28(7–8), 679–695. doi:10.1177/0269094213501274

- Richards, D., & Smith, M. J. (2015). Devolution in England, the British political tradition and the absence of consultation, consensus and consideration. Representation, 51(4), 385–401. doi:10.1080/00344893.2016.1165505

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2008). The rise of the ‘city-region’ concept and its development policy implications. European Planning Studies, 16(8), 1025–1046. doi:10.1080/09654310802315567

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Sandall, R. (2008). From identity to the economy: Analysing the evolution of the decentralisation discourse. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 26(1), 54–72. doi:10.1068/cav2

- Semian, M., & Chromý, P. (2014). Regional identity as a driver or a barrier in the process of regional development: A comparison of selected European experience. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 68(5), 263–270. doi:10.1080/00291951.2014.961540

- Šerý, M., & Šimáček, P. (2012). Perception of the historical border between Moravia and Silesia by residents of the Jeseník area as a partial aspect of their regional identity. Moravian Geographical Reports, 20(2), 36–46.

- Storper, M. (1997). The regional world: Territorial development in a global economy. Guilford.

- Swyngedouw, E. (1997). Neither global nor local: ‘glocalisation’ and the politics of scale. In K. Cox (Ed.), Spaces of globalization: Reasserting the power of the local (pp. 137–166). Guilford.

- Vainikka, J. (2012). Narrative claims on regions: Prospecting for spatial identities among social movements in Finland. Social & Cultural Geography, 13(6), 587–605. doi:10.1080/14649365.2012.710912

- Vallbé, J.-J., Magre, J., & Tomàs, M. (2018). Being metropolitan: The effects of individual and contextual factors on shaping metropolitan identity. Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(1), 13–30. doi:10.1111/juaf.12243

- Van Houtum, H., & Lagendijk, A. (2001). Contextualising regional identity and imagination in the construction of polycentric urban regions: The cases of the Ruhr area and the Basque country. Urban Studies, 38(4), 747–767. doi:10.1080/00420980120035321

- Walter-Rogg, M. (2018). What about metropolitan citizenship? Attitudinal attachment of residents to their city-region. Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(1), 130–148. doi:10.1080/07352166.2017.1355664

- Zimmerbauer, K., & Paasi, A. (2013). When old and new regionalism collide: Deinstitutionalization of regions and resistance identity in municipality amalgamations. Journal of Rural Studies, 30, 31–40. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.11.004