?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

We study ‘regional resentment’, or the feeling that one’s region is not treated rightly by citizens and elites from other regions, in a European context. Is this mainly a rural or a peripheral phenomenon, or do these two contextual characteristics matter equally? We present three survey items to measure regional resentment, field it among a geocoded representative sample of 8000 Dutch citizens stratified by region and urbanity, and show that they create a valid scale. Regional resentment differs between urban and rural areas, but is especially strong in peripheral and deprived areas, and amongst citizens with strong place-based identities.

JEL:

1. INTRODUCTION

Political attitudes and behaviours tend to be unevenly distributed across different areas within countries. In particular, anti-EU and anti-immigrant sentiments (Czaika & Di Lillo, Citation2018; Dijkstra et al., Citation2020), support for populist (radical right) parties and candidates (Albertazz & Zulianello, Citation2021; Arzheimer & Berning, Citation2019; Gavenda & Umit, Citation2016; Scala & Johnson, Citation2017), political distrust (Kenny & Luca, Citation2021; Mitsch et al., Citation2021; Stein et al., Citation2021) and voting in favour of Brexit (Becker et al., Citation2017; Johnston et al., Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2018) cluster in areas which Rodríguez-Pose (Citation2018) calls the ‘places that don’t matter’. The literature demonstrates that the discontent experienced in these places is rooted in where citizens live and how they experience their area. Many citizens in these areas believe that elites, who live in places that ‘do matter’, ignore the interests of their area, do not give them their ‘fair share’ and do not respect their way of life (Cramer, Citation2016; Munis, Citation2020; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2020). For this reason, this particular kind of territorially rooted discontent has been labelled ‘place resentment’ (Munis, Citation2020).

However, it remains unclear in what kinds of areas this form of resentment is most prevalent, and amongst what kinds of citizens. Some scholars have argued that it is particularly strong among citizens living in rural areas (e.g., Cramer, Citation2016; Scala & Johnson, Citation2017), while others claim that citizens living in peripheral areas are most likely to experience it (e.g., Guilluy, Citation2019). Distinguishing the two is important, because rurality and peripherality constitute different experiences and the two oppositions only partially overlap. Rural areas can be centrally located (that is, close to a country’s centre of cultural, economic and political dominance), while cities can also be located in the periphery (that is, far away from a country’s centre of cultural, economic and political dominance). While rurality and peripherality might both coexist as drivers of place resentment, the reasons behind this type of discontent might be different. People in rural areas might feel that city folks do not respect their way of life, while inhabitants of cities in peripheral areas may sense that those who live in the cultural and economic centre of the country do not respect them enough. So, distinguishing between the two is crucial for a clear understanding of the distribution as well as the roots of this type of discontent.

While rurality and peripherality are both considered to be related to different types of discontent, these two dimensions have not been tested simultaneously, nor have they been examined extensively outside of the United States. Existing studies on Europe have focused on forms of discontent that are not place-based (such as political trust; e.g., Mitsch et al., Citation2021; Stein et al., Citation2021) and often study aggregate correlations (such as regional economic deprivation and populist party support; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018; or linguistic peripherality and support for the populist radical right; Ziblatt et al., Citation2019). While these studies yield important insights, it remains to be seen whether place resentment can be successfully operationalized in Europe and whether place resentment is mainly a rural or mainly a peripheral phenomenon, or that the two dimensions coexist.

Our paper answers these questions, focusing on the Netherlands. The Netherlands is one of the smaller and most densely populated countries in Europe. Consequently, distances between urban and rural areas, as well as between the periphery and the political, economic and cultural centre are small. Moreover, the highly fragmented Dutch party system has not been structured by the urban–rural and centre–periphery cleavage (e.g., Lipset & Rokkan, Citation1967), and the electoral and media system are highly centralized. Finally, the Netherlands is amongst the European countries with the lowest levels of regional inequalities (Muštra & Škrabić, Citation2014) due to its strong welfare state. Hence, it is in many respects a least likely case to find regional resentment. Moreover, in terms of its structural features, the Netherlands the polar opposite of the UK and the US, the countries in which the geographical of discontent has been studied most frequently. The literature suggests that strong geographical divides are most likely to occur in electoral systems with single-member districts (Rodden, Citation2019), such as those used in the UK and the US. However, with its purely proportional electoral system without districts, the Netherlands is not only a least likely case to find regional resentment, but also more generally to find geographical divides in citizen attitudes.

Our paper makes three contributions to the literature about the geography of discontent. First, we apply the concept of place resentment, developed by Munis (Citation2020) in the US, to the Dutch context. While our concept is the same as Munis’s (Citation2020) concept ‘place resentment’, we prefer the term ‘regional resentment’ as this is linked more closely to the areas that people identify with, at least in the Dutch context. We define ‘regional resentment’ as the sentiment that one’s region is not treated well by those from other regions, whether these are elites or citizens. Our operationalization of this concept, which consists of three survey items that capture the cultural, economic, and political dimension of place resentment, allows respondents to rely on their own understanding what constitutes ‘their region’.

Second, we examine whether these survey items produce a reliable and valid measure of the theoretical concept. We administer the items to a georeferenced representative sample of 8000 Dutch citizens, which was stratified by province and urbanity. The fact that our sample is large and spatially stratified, combined with very fine-grained georeferencing at the neighbourhood level, allows us to make inferences about citizens in a wide range of contexts. We test the construct validity of the operationalization by demonstrating that the three items form a strong Mokken scale. We test the discriminant validity by comparing this scale with a well-known battery measuring populist attitudes (Akkerman et al., Citation2014). While the two scales are related, as expected, the analyses show that regional resentment is distinct from a general dislike of (political) elites. Although our operationalization of regional resentment differs somewhat from Munis’s (Citation2020) operationalization of place resentment, we arrive at very similar conclusions.Footnote1 Place resentment and regional resentment can be measured in a valid way as individual level attitudes, and are distinct from related attitudes measuring, for example, support for populism.

Third, we examine explanations for individual level variation in regional resentment, and study whether it is particularly prevalent in rural or peripheral areas. As far as we are aware, no study exists that has compared the impact of rurality and peripherality on regional resentment. We show that feelings of regional resentment are slightly stronger in rural areas than in urban areas, but the effect of rurality is weak. Regional resentment turns out to be mainly a ‘peripheral’ phenomenon, in the sense that these feelings are especially strong in areas located further from the political, economic and cultural ‘centre’ in Netherlands. Moreover, these sentiments are stronger in the areas that experience economic and demographic decline. At the individual level these feelings are stronger amongst citizens with higher levels of regional identification and lower levels of education.

We conclude that regional resentment is prevalent in the Netherlands, even though it is an unlikely case for finding it. It therefore seems plausible that regional resentment, or other forms of place resentment, will also exist in other European countries, even when these countries historically are not characterized by strong geographical divides and do not display large geographical inequalities. We also conclude that, despite a natural inclination to perceive spatial oppositions along urban–rural lines (Jansson, Citation2013), the geography of discontent in the Netherlands reflects primarily feelings of resentment of the periphery towards the centre, much more than resentment of rural areas towards the cities.

2. THEORY

Social and political geography is back as an explanation for a wide range of political phenomena, including anti-immigrant sentiments (Czaika & Di Lillo, Citation2018), Euroscepticism (Dijkstra et al., Citation2020), political trust (Mitsch et al., Citation2021; Stein et al., Citation2021), voting for populist (radical right) parties and candidates (e.g., Albertazz & Zulianello, Citation2021; Arzheimer & Berning, Citation2019; Di Matteo & Mariotti, Citation2020; Essletzbichler, Citation2018; Fitzgerald, Citation2018; Gavenda & Umit, Citation2016; Scala & Johnson, Citation2017), and voting in favour of Brexit (e.g., Becker et al., Citation2017; Essletzbichler, Citation2018; Johnston et al., Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2018). More generally, it is especially popular when trying to account for discontent with (mainstream) politics, with research studying the geography of discontent in Europe (e.g., Di Matteo & Mariotti, Citation2020; Fitzgerald, Citation2018; Gavenda & Umit, Citation2016; Guilluy, Citation2019; McCann, Citation2020; McKay, Citation2019; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2020) and the US (Cramer, Citation2016; Hochschild, Citation2016; Munis, Citation2020; Rodden, Citation2019). In this section we propose the concept of regional resentment to better understand these phenomena, and subsequently discuss in which areas and among which citizens it is likely to be most prevalent.

2.1. Defining regional resentment

Citizens tend to have a place-based social identity that is constructed around feelings of attachment to the geographical area (e.g., the neighbourhood, town or village, or region) in which they live (Cramer Walsh, Citation2012, Citation2016; Fitzgerald, Citation2018; Munis, Citation2020). Under certain circumstances, this positive in-group identity might result in feelings of resentment towards out-groups living in other geographical areas. Munis (Citation2020) refers to this phenomenon as ‘place resentment’. For various reasons, place-based identity and resentment are closely connected. Citizens with strong place-based identities tend to have perceptions of the ways in which this geographical area is doing culturally, economically, and politically (Ziblatt et al., Citation2020). Moreover, they are more likely to feel personally affected if they perceive the local community to be under threat (Fitzgerald, Citation2018), and they are also more likely to experience a sense of resentment when they perceive that their area suffers from some form of distributive injustice.

Cramer (Citation2016) argues that citizens in rural areas have developed a ‘rural consciousness’ that has spilled over into feelings of ‘rural resentment’. However, similar feelings of resentment exist in urban areas in regions in which many citizens feel ‘left behind’ (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018). We therefore prefer a concept that does not define a priori in which types of larger geographical areas place resentment is strongest. We introduce the concept of regional resentment, which we define as the sentiment that one’s region is not treated well by elites and/or citizens from other regions.Footnote2 In line with the work of Cramer (Citation2016) and Munis (Citation2020), we acknowledge that this sentiment has a political, economic and cultural dimension. It comprises the feeling that (1) politicians and policy makers overlook your region, (2) your region is not getting its fair share and (3) people in your region have distinct lifestyles, norms, values and traditions which are not appreciated by people in other regions.

Different forms of regional resentment feature implicitly or explicitly in dominant accounts of contemporary political geography, but are not often operationalized as an individual level attitude in surveys (but see McKay, Citation2019; Munis, Citation2020). Rodríguez-Pose (Citation2018, p. 199), for example, presents a wealth of evidence on aggregated correlations between economic and demographic decline and support for populist parties, and states that ‘[t]he places that don’t matter are becoming tired of being told that they don’t matter and are exercising a subtle revenge’. Similarly, Ziblatt et al. (Citation2020, p. 7) propose peripherality as an explanation for AfD support, arguing that ‘the lower self-perceived status of citizens in these historically and culturally fringe regions … can be enduring which leads to support for anti-establishment and anti-immigrant radical right political parties’. Although we acknowledge that these accounts might be correct, studying regional resentment requires it to be operationalized in surveys. Although Munis (Citation2020) operationalizes place resentment on the basis of 13 survey items that can be used in the US context, a similar endeavour has not yet been undertaken in the European context. In this paper, we therefore operationalize regional resentment as an individual level attitude and assess its construct validity.

Our definition of regional resentment mentions political, economic, and cultural elites, which makes it conceptually related to populism. When conceptualized as an attitude, populism refers to the belief that there is an antagonism between two homogenous groups: the good people and the corrupt elite (Akkerman et al., Citation2014; Mudde, Citation2004). Populism and regional resentment both rely on in- and out-group thinking and posit that the interests of the in-group are not sufficiently taken into account by the out-group. However, while regional resentment presumes that the elite is based in a certain (kind of) region, populism does not make that assumption. While populism sees the main conflict line between ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’, regional resentment sees the main divide between ‘the people in my region’, and ‘the elite (and people) in another region’. We therefore expect that when we measure the two attitudes in surveys, they tap into distinct but related latent constructs.Footnote3 We take this into consideration when designing our study. When testing the (discriminant) validity of the operationalization of regional resentment, we ascertain that regional resentment is indeed a different attitude than populism. Also in the analyses that focus on the geography of regional resentment – whether it is a rural and/or peripheral phenomenon – we are careful to explain regional resentment and not populist attitudes. For this reason, we will control for populist attitudes in some of our models, as will be explained in more detail in the methodological section.

Of course, regional resentment does not emerge in a vacuum. As we discuss below, it is likely to be influenced by the level of deprivation of an area, which alerts its residents to interregional inequalities, as well as citizens’ affective ties to the region and their networks and resources, which allow them to withdraw from a region. At the same time, we expect that living in a specific area is only relevant for citizens for whom the region is a relevant unit for their place-based identity (Cramer Walsh, Citation2012).

2.2. A rural or peripheral phenomenon?

In which areas of a country is regional resentment most likely to thrive? As mentioned in the introduction, two theories exist: one stressing its rural and the other its peripheral roots. The first account argues that regional resentment is strongest in rural areas and is most dominant in the scholarly and public debate (Cramer, Citation2016; Munis, Citation2020; Rachman, Citation2018). Several studies show that political distrust and dissatisfaction with democracy are more prevalent in European rural areas compared with cities, and increasingly so (Kenny & Luca, Citation2021; Mitsch et al., Citation2021). Indirect evidence for the importance of the urban–rural divide is also provided on the basis of Donald Trump’s 2016 election (Scala & Johnson, Citation2017), the outcome of the Brexit referendum (Becker et al., Citation2017; Lee et al., Citation2018), or the results of the 2017 Austrian presidential elections (Gavenda & Umit, Citation2016). According to most authors’ line of reasoning, urban areas – and especially large metropolitan cities – are benefitting from globalization, the knowledge economy, and other economic transformations, leading their populations to embrace cosmopolitan values. Rural areas, by contrast, are left behind, given that they do not benefit from these transformations. As a result, their entrenched inhabitants resent the (inhabitants of the) cities. In other words, it is the strong sense of place-based identity in rural areas, in combination with the relative decline compared with cities, that creates feelings of regional resentment in the countryside.

Hypothesis 1a: Other things being equal, regional resentment is more widespread in more rural areas.

Hence, an alternative approach looks for the roots of regional resentment in peripheral rather than rural areas. As Guilluy (Citation2019, p. 63) notes about the French case, ‘if the impoverishment of rural areas is often acknowledged, the decline of commerce in the cities of peripheral France is less noted’. Stein et al. (Citation2021) show that in Norway political distrust is first and foremost a peripheral phenomenon, even though it also has an urban–rural dimension. However, their study does not explore whether political distrust has also a distinctly regional dimension in in terms of the sentiments experienced towards the political, economic, and cultural centre. According to Lipset and Rokkan (Citation1967), the periphery refers to those areas that are located outside the part of the country that that initiated the project of nation-building. Peripheral areas retain lower status cultural markers that define these areas in relation to the national community at large, and the centre in particular (Ziblatt et al., Citation2021). In most countries stark political, economic, and cultural differences exist between peripheral and central areas. Peripheral status thus provides citizens with both a place-based identity and a clearly defined hierarchical relation with the centre. Especially if combined with real or perceived political, economic, or cultural disadvantages, this likely creates feelings of regional resentment.

To be sure, the centre–periphery distinction is fluid in time and space. Moreover, the political centre does not have to coincide with the cultural and/or economic centre. For instance, Madrid is Spain’s political centre, but has to share the status of cultural and economic centre with other cities (e.g., Barcelona, Bilbao, Sevilla). In regions in the US where people feel they are not getting their fair share from the federal government, they blame ‘Washington’. Yet, the feeling that one’s way of life is not respected by ‘cultural elites’ may also be directed against ‘liberals’ in New York and San Francisco. Yet, despite this fluidity of the centre–periphery distinction, periphery status has a real spatial component – some areas are far removed from economic, cultural, and political power. It is likely that regional resentment thrives in exactly such peripheral areas. And while peripheral areas are more likely to be rural, they also contain cities and towns.

Hypothesis 1b: Other things being equal, regional resentment is more widespread in more peripheral areas.

2.3. Other explanations: deprivation and place-based identity

Obviously, the rurality or peripherality of the geographical location will not be the only factor shaping regional resentment. In this section, we discuss two factors – one at the regional and one at the individual level – that should impact regional resentment. At the regional level, resentment will resonate more strongly if linked with real regional disadvantages (McKay, Citation2019). When a specific region – regardless of whether it is rural or peripheral – is economically flourishing and when there are good career opportunities for young people, there may be less reason to think that the region is not being treated well (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018). However, if businesses are closing down, public facilities (post offices, libraries, schools and banks, etc.) are disappearing and the most entrepreneurial young people move out of the area (Bock, Citation2016), those who stay may see little opportunity. Such a context seems to provide a fertile breeding ground for feelings of regional resentment, where the ‘arrogant elite in the centre’ is blamed for the problems of the region (Agerberg, Citation2017). So, controlling for individual socio-economic status, we expect that:

Hypothesis 2: Other things being equal, regional resentment is more widespread in areas with higher levels of deprivation.

At the individual level, regional resentment will be higher among those who (strongly) identify with their region and hence have a strong place-based identity (Antonsich & Holland, Citation2014; Hidalgo & Hernández, Citation2001; Stedman, Citation2002). Like other social identities, strong regional ingroup identification does not necessarily involve outgroup derogation. However, if citizens strongly identify with their region, they are more likely to develop a regional lens through which they understand developments. By contrast, residents who did not grow up in the region, or developed little affinity with it, or even consider moving somewhere else, and as a result do not have a strong place-based identity, are less likely to develop the sentiment that ‘the region is not getting its fair share’. Indeed, Munis (Citation2020) demonstrates that place resentment and place identity are strongly related in the United States. Hence, we expect:

Hypothesis 3: Other things being equal, identification with a region has a positive effect on regional resentment.

3. DESIGN, DATA AND METHOD

To examine (explanations for) regional resentment, our study focuses on the Netherlands. Since the early 2000s, the Netherlands has experienced a surge in support for populist parties, with populist radical right (FvD, JA21, LPF, and PVV) and populist radical left (SP) parties gaining parliamentary representation. Political discontent has been cited as one of the factors explaining the support for these parties (e.g., Rooduijn et al., Citation2016). However, given the political, geographical, and demographic characteristics of the Netherlands, it is a least likely case for observing regional resentment and finding strong variations in such resentment between urban and rural areas or the centre and the periphery. After all, the Netherlands is a small-scale country that is densely populated. Consequently, distances between urban and rural areas, as well as between the periphery and the political, economic and cultural centre are small. Moreover, the urban–rural and centre–periphery divides have not been of great importance for the formation of the Dutch party system (e.g., Lipset & Rokkan, Citation1967), and the electoral and media system are highly centralized. Finally, the Netherlands is amongst the European countries with the lowest levels of regional inequalities (Muštra & Škrabić, Citation2014) due to its strong welfare state. Hence, if we find geographical patterns of regional resentment under these circumstances, they probably exist as well in countries in which geographical oppositions are more likely to manifest itself.

In the Netherlands, a large part of the population lives in an area referred to as the ‘Randstad’, a heavily urbanized area spanning three provinces (North Holland, South Holland and Utrecht) and containing the four largest cities in the country (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht). The Randstad is home to more than one-third of the Dutch population, even though it covers only 15% of its land mass. We expect most feelings about the ‘centre’ to implicitly refer to the Randstad, since most key institutions of political, economic and cultural life are located in it. However, within the Randstad, two different centres can be identified: Amsterdam and The Hague. For historical reasons, the Dutch government institutions are in The Hague, while large company headquarters and cultural associations (e.g., media headquarters, debating centres, theatres) are in capital Amsterdam. Hence, in the Netherlands the ‘centre’ usually refers to the Randstad (also often shortened to ‘the west’). The area outside of the Randstad comprises nine other provinces with distinct economic and cultural characteristics – including dialects – rooted in different historical starting points and trajectories. According to this reasoning, areas that are further away could be considered as progressively more ‘peripheral’.

3.1. Data

Our data consists of a survey collected for the purpose of studying subnational variation in political outcomes (SCoRE, Citation2017).Footnote4 This survey was fielded over a two-week period in early May 2017, shortly after the national elections of 15 March. The respondents were sampled from the standing panel of the survey company GfK to be representative of the population in socio-demographic and geographical terms. The sample was stratified by age, education, ethnicity, urbanity, and province. The latter two stratification factors ensure a balanced distribution of respondents over the country, thus creating a dataset unique suited to our purposes. The net response rate was 67.1%, resulting in a dataset with 8133 respondents.Footnote5

The location of the respondents’ residences was recorded, which allows us to connect it to local level data about deprivation. These data were obtained from Statistics Netherlands. As discussed in more detailed in the operationalization section below, we measure deprivation at the level of local neighbourhoods (‘wijk’; average population around 6000) and municipalities (‘gemeenten’, average population around 43,000). The former are perfectly nested within the latter.

3.2. Model

To test our hypotheses, we estimate hierarchical three-level random effects models. The full model can be expressed as follows, where i indexes individuals, j indexes neighbourhoods and k indexes municipalities, Cijk is a vector of individual-level controls (listed in het operationalization section below), u0j and u0k denote random intercepts on the district and municipality level, and eijk refers to the error term:

As discussed in the theory section, our dependent variable regional resentment is expected to be related to populist attitudes, which are general anti-elite sentiments without any geographical roots. Since we want to explain regional resentment only, and since we do not want it to be contaminated with other kinds of (populist sentiments), we include populist attitudes as a control variable in our model.

3.3. Measurement and validation of regional resentment

Determining the region that people are most likely to identify with is far from straightforward. Administrative regions, such as provinces or departments, might not correspond to the area that determines citizens’ place-based identity. Moreover, the area to which a place-based identity is connected can be expected to differ between citizens, as well as between regions and countries. Even citizens living in the same city, town or village can have different conceptions of what ‘their region’ is. For this reason, we build our survey items capturing regional resentment around the notion of ‘your region’, leaving it up to the respondent to interpret the geographical area this concept refers to. In line with our conceptualization, we use three survey items to measure regional resentment (). The items tap into different aspects of regional resentment, focusing on its political, economic and cultural dimensions (cf. Cramer, Citation2016; Munis, Citation2020). Each item pits ‘your region’ against geographical ‘others’. Undoubtedly, by mentioning the government or The Hague, the items to a certain extent also capture political distrust in a more general sense. To isolate the specifically regional component as far as possible we control for respondents’ score on the populism scale (see below). The answer options for each of the items consists of a Likert scale that ranges from 1 (fully disagree) to 7 (fully agree).

Table 1. Statements measuring regional resentment.a

As the descriptive statistics in show, citizens are most likely to agree with the first item (POL), and least likely to agree with the last item (APPR). A remarkable pattern in missing values occurs for the item APPR. This item was answered with ‘Don’t know’ by a large group of respondents. However, these respondents were not evenly distributed over the country: 1% of the respondents in the Northern provinces answered ‘Don’t know’, 25% of the respondents in the Southern and Eastern provinces, and 37% in the Western provinces. This pattern suggests that many respondents in the Randstad, who apparently could not relate to the statement, skipped the item rather than indicating disagreement. To capture the full extent of the intended construct, we nevertheless opt to employ listwise deletion (i.e., only retained respondents who answered all questions) in the main analyses reported below. However, as a robustness check we replicate all analyses using pairwise deletion (i.e., also including those who answered ‘Don’t know’ to an item). These replications produce very similar results.

Table 2. Descriptives for items measuring regional resentment.

Since we present a new concept and its operationalization, we examine its construct, criterion, and discriminant validity. To investigate the construct validity, we analyse whether the three items form a scale that measures a latent construct. Given the three items have a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83, and an H-value of 0.66 in a Mokken scale analysis, it can be concluded that they form a strong scale (Mokken, Citation1971). So, in terms of construct validity the items perform very well.

To examine whether the criterion and discriminant validity of the scale, we investigate whether it is correlated with an existing scale that measures populist attitudes (Akkerman et al., Citation2014). We expect that the two scales are indeed correlated, but that regional resentment is also distinct from populism. Hence, if the relationship between the two scales is too strong, they would tap into the same latent construct. We conducted two tests of the dimensionality of the sets of items that measure regional resentment and populist attitudes. The first test is a simple principal component analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation (see Appendix A in the supplemental data online). The analysis yields two extracted factors with Eigenvalues > 1. The six populism items have a strong loading (all > 0.6) on the first factor, while the three regional resentment items have a strong loading on the second factor (all > 0.7). The cross loadings are all < 0.3. The correlation between the two scales is 0.44.Footnote6 Hence, these results are a first indication the items measure different constructs. The second test is a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (see Appendix B online). This analysis demonstrates that a model with two latent constructs (populism and regional resentment) fits the data sufficiently well (root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.058), whereas a model with one latent construct needs to be rejected (RMSEA = 0.182). The estimated correlation between the two latent constructs is 0.54.Footnote7 Therefore, we conclude that the scale measuring regional resentment meets the standards of criterion validity (a strong correlation with populist attitudes) as well as discriminant validity (the items load on different factors in a PCA/on different latent constructs in CFA). To further distinguish between regional discontent and populist attitudes, we will include the latter as a control variable in our models. This will enable us to estimate geographical variations in regional discontent only, rather than regional discontent combined with populist attitudes.

3.4. Measurement of independent variables at the context level

Urbanity (Hypothesis 1a) is measured using the five-fold categorization developed by Statistics Netherlands based on the density of a respondent’s municipality measured as the average ‘address density’ – that is, the average number of other addresses located in a circle of 1 km around any address. This indicator has the categories ‘Not urban’ (fewer than 500 addresses within 1 km; 19% of the sample), ‘Weakly urban’ (500–1000; 28%), ‘Moderately urban’ (1000–1500; 21%), ‘Strongly urban’ (1500–2500; 18%) and ‘Strongly urban’ (more than 2500; 14%).

Peripherality (Hypotheses 1b and 4b) is measured by calculating the distance to the parliament in The Hague of a respondent’s municipality. This operationalization is very similar to the one employed by Stein et al. for Norway, who use the distance to the capital city as their measure. In the Dutch case, it is a bit more complex, since the government is in The Hague and Amsterdam is the capital. However, Amsterdam is relatively close to The Hague (distance 65 km). We replicated the analyses using the distance from Amsterdam, but – because the two distances are strongly correlated for most parts of the country – the analyses yielded almost identical effects. The average distance is 79.9 km (minimum = 0.38 km; 25th percentile = 45.0 km; 75th percentile = 132.5 km; maximum = 233.8 km).

Local deprivation (Hypotheses 2 and 3b) is measured using indicators of phenomena that signal an area is experiencing economic and demographic deprivation. In particular, we use the following four indicators taken from Statistics Netherlands: unemployment (measured as share of population receiving unemployment benefits; %); mean income (in 1000s of euros); distance to public and private services (km);Footnote8 young residents of 25–45 years (%). Unemployment and (low) income levels are classic contextual indicators of economic hardship used in studies of discontent (e.g., McKay, Citation2019), while a lack of young residents (i.e., demographic decline) and a lack of public and private services (reducing the broader livelihood of a community) are relatively novel contextual indicators of local marginalization that have been shown to correlate with political outcomes elsewhere (Harteveld et al., Citation2021; cf. van Leeuwen et al., Citation2020).

Because we expect economic hardship to vary between and within municipalities, we measure the first two variables on the level of neighbourhoods (‘wijk’, average population 5998). Since we expect local marginalization to play out in areas beyond the immediate neighbourhood, we measure the latter two variables on the level of municipalities (‘gemeente’, average population 43,004). In our main model, we include the absolute level of these variables. In an alternative model, we replace the two indicators at the lowest (neighbourhood) level (that is, unemployment and income) by relative deprivation scores (as suggested by Gutierrez-Posada et al., Citation2021), by calculating the difference with the surrounding municipality. We report this model in Appendix F in the supplemental data online. Appendix C online provides descriptive statistics of all independent and dependent variables.

3.5. Measurement of independent variables at the individual level

To capture respondents’ place-based identity, their identification with their region (Hypotheses 4a and 4b) is measured using the question ‘To what extent do you feel attached to your region’, with the answer scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (a lot). To distinguish any effect or regional discontent from populist attitudes, we measured the latter using a six-item populism scale that is commonly used in populism studies (Akkerman et al., Citation2014; Geurkink et al., Citation2020), of which the mean value is taken.Footnote9 We include the following socio-demographic control variables: education (low, middle and high), age, gender, immigration background (yes/no), religiosity (1 not at all to 7 very religious) and unemployment (yes/no).

4. FINDINGS

4.1. Descriptives

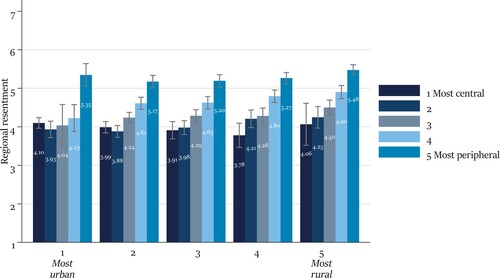

Is regional resentment higher in rural areas and in peripheral areas? explores this question descriptively by displaying the mean level of regional resentment by distance to The Hague (in quintiles) and the level of urbanity. To assess if city dwellers differ from rural residents independently of whether they live in central or peripheral areas (and vice versa), we plot regional resentment over combinations of the two dimensions. In Appendix E in the supplemental data online we also show the geographical distribution of the scores over Dutch municipalities.

A comparison of the urbanity levels (main categories on the x-axis) shows that regional resentment tends to be higher in rural than in urban areas. An exception might be the most central areas in the Randstad: citizens’ level of regional resentment is quite stable regardless of rurality in these areas. At the same time, differences between peripheral and central areas (the bars with different colours) are even more pronounced, with citizens in the most remote areas scoring a full 1.5 point higher on the 1–7 scale than those in the most central areas. This gradient is visible across all urbanity categories, but perhaps most clearly so in more rural areas. Hence, suggests that both peripherality and rurality are associated with more regional resentment in the Netherlands, and that the effect of the former is stronger than that of the latter. It also suggests an interaction might exist between the two, as peripherality appears to matter most in rural areas, although we note that the differences in gradients are small compared with the confidence intervals. Below we provide a formal test of both main effects and their interaction.

4.2. Multivariate analysis

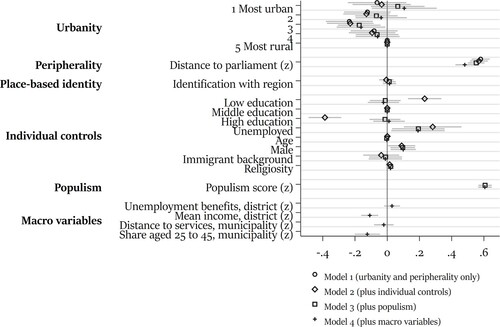

To formally test predictors of regional resentment, we run a number of multilevel regressions ().Footnote10 Model 1 includes our indicators for urbanity and peripherality. Model 2 adds individual level controls. Model 3 adds the populism measure, allowing us to observe to what extent the findings are robust to its inclusion. Model 4, finally, includes the macro level variables capturing regional deprivation, which might partially mediate the effect or urbanity and/or rurality.

Model 1 shows that urban areas score lower on regional resentment than the most rural ones (the reference category), although the difference between the types of areas is not always significant. These effects remain of a similar magnitude in model 2 with individual level socio-demographic control variables present. In other words, the urban–rural gap in regional resentment is not (merely) the product of socio-demographic composition. However, when populist attitudes are included in model 3, the effect of urbanity shrinks considerably and for most categories disappears. Hence, the urban–rural divide in regional resentment reflects a general anti-establishment sentiment and not a strongly place-based resentment. Adding the variables measuring the degree of deprivation of an area hardly reduces the effect of urbanity, suggesting the gap between urban and rural areas is not due to higher levels of deprivation in the latter.

Distance to parliament is a much more robust predictor of regional resentment than urbanity. Its strong predictive power is present even when socio-demographic controls (model 2) and populist attitudes (model 3) are added. Including the deprivation variables slightly reduces its effect, suggesting part of the effect is due to higher levels of deprivation in peripheral areas.Footnote11

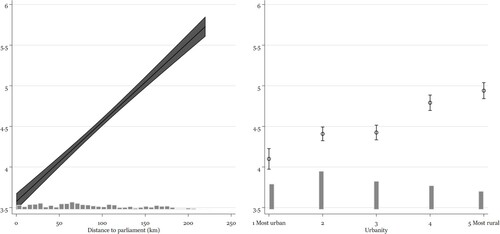

It is difficult to compare the effect sizes of urbanity and peripherality based on the coefficients alone. therefore plots predicted probabilities based on the estimates in model 3, that is, with all individual level predictors and without the macro level variables. In addition, it presents overlaid distributions of the two independent variables. confirms that urbanity and peripherality are both associated with regional resentment. However, it also shows that the difference in regional resentment is far greater between peripheral and central areas than between urban and rural areas.

Figure 3. Predicted regional resentment based on distance to parliament and urbanity.

Note: With overlaid distribution of peripherality and urbanity.

As noted, it is possible that rurality and peripherality interact in shaping regional resentment. The regression model in Appendix F in the supplemental data online tests for this by interacting distance to parliament with, first, the urbanity dummies, and second, a continuous indicator of urbanity. Neither model results in significant interaction effects (p > 0.05), and hence we conclude that rurality matters similarly regardless of peripherality and vice versa.

Moving to the remaining hypotheses, model 4 indicates that two of the four indicators of local deprivation affect regional resentment. Regional resentment is higher in those areas where incomes are lower and where there are few residents between 24 and 45, providing support for Hypothesis 2.Footnote12 The results are the same using a relative deprivation indicator for unemployment and income (see Appendix G in the supplemental data online). By contrast, identification with the region does not have a direct effect on regional resentment, thus refuting Hypothesis 3. The latter finding underlines the need to differentiate place-based identity from place resentment. On the basis of inclusion of the socio-demographic variables in model 1, it can also be concluded that regional resentment is higher among the lower educated, those who are unemployed, and male. However, the education effect disappears completely when populist attitudes are included in model 3, suggesting that education is related to a general anti-establishment sentiment rather than to place resentment. The effects of unemployment and gender remain significant when populist attitudes are added.

In sum, regional resentment appears to be at least as much a function of context (most notably of living far from the centre of the country, of living in a neighbourhood with low incomes, and of living in a municipality with few youngsters), as it is a function of individual characteristics This is a noteworthy finding, because most political attitudes vary more within than between groups.Footnote13

4.3. Cross-level interactions

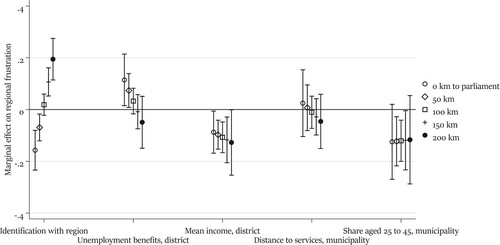

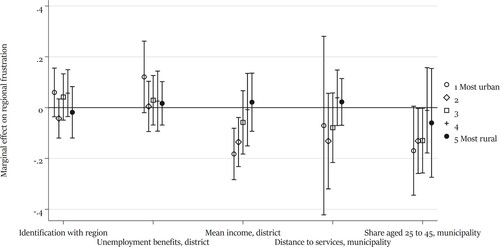

It is possible that the effects of deprivation and of place-based identity vary across areas. We therefore run a separate model in which we interact these variables with urbanity and peripherality. show the marginal effects of the variables over different urbanity (model 4) and peripherality (model 5) scores.

Figure 4. Marginal effects of regional identification and of deprivation indicators, by urbanity category.

demonstrates that the effects of deprivation and place-based identity are not moderated by urbanity. It suggests that a lower income is associated with more regional resentment in the most urban areas, a finding that was not expected, but no other effects are significant. shows that the relationship between place-based identity is moderated by peripherality. Most importantly, it shows that identification with the region increases regional resentment, but only in more peripheral areas. In more central areas, it has a negative effect on regional resentment. This confirms our expectation that place-based identity only translates into resentment if citizens live in peripheral areas. The relationship between deprivation and regional resentment is not moderated by peripherality.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In this article we introduced the concept of ‘regional resentment’, the sentiment that one’s region is not treated well by those from other regions. We proposed a measure of regional resentment, consisting of three survey items that tap into its political, economic and cultural dimension, and fielded it in a geocoded survey among 8000 people in the Netherlands. We find that the three items form a valid and reliable scale. As expected, regional resentment is positively correlated with populist attitudes, but the items do not measure the same latent construct. These findings are remarkably similar to those reported on ‘place resentment’ in the US context by Munis (Citation2020). Whereas the US is perhaps a most likely case for finding such sentiments (it being a federal state with urban areas that are very remote from any city and high levels of geographical inequality), the Netherland may be a least likely case (it being small, densely populated and centralized with low levels of geographical inequality). The fact that we find such similar attitudes in these very different contexts and political systems shows the generalizability of the concept.

The geocoded sample gave us the opportunity to assess whether regional resentment is rural and or peripheral phenomenon. Multilevel regression analyses demonstrated that citizens living further away from the political centre are increasingly more likely to experience regional resentment. Even if regional resentment is somewhat higher in rural than in urban areas, the differences between centre and periphery are much more pronounced. So, at least in the Netherlands, the sentiment that has sometimes been considered ‘rural discontent’ (Cramer, Citation2016) is not so much a rural, but mostly a peripheral phenomenon. An important implication of this finding is that the classic division between centre and periphery introduced by Lipset and Rokkan (Citation1967) is still relevant, even in a small and centralized country like the Netherlands. Our study also shows that regional resentment is especially high in areas experiencing low incomes and/or an exodus of young people. These findings are thus in line with previous studies on ‘the places that don’t matter’ (e.g., Becker et al., Citation2017; Lee et al., Citation2018; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018).

How generalizable are our findings regarding the peripheral nature of regional discontent to other countries? Of course, the Netherlands is a somewhat unusual country given that it is relatively centralized and urbanized and does not have a tradition of regionally defined minorities or historical separatism. However, all this makes it all the more interesting to find a strong feeling of regional resentment, and especially one that is strongly spatially defined. We therefore think it is likely that regional resentment also exists in other European countries, and that it will also have a clear centre–periphery and/or urban–rural component.

Our findings make it relevant to expand this type of research to other contexts. The definition and operationalization of a peripheral area used in this study (that is, distance to the political and cultural capital) will surely require adjustment in order to travel to other contexts. Some countries may have several regional centres, and as a result it may be more difficult to empirically distinguish rural and peripheral areas. In some countries, such as France, the countryside faces more pronounced challenges, and the urban and rural divide could be more important. In other countries, such as Spain, pre-existing regionalism might make the centre–periphery dimension more relevant. Yet, we believe it is important to conceptually distinguish between peripherality and rurality and to try to disentangle them empirically.

We think our findings lead to the following suggestions. First, academics and participants of the public debate should be careful not to conflate ‘rural’ and ‘peripheral’. Second, more research is needed to understand how centre–periphery divides shapes politics in many countries without a strong (historically) separatist regions, the traditional focus of research on the topic. Third, while we think our conceptualization and operationalization of regional resentment is a useful starting point, there remain many avenues to explore the concept further. Future research is needed to better understand, for instance, the relative role of economic, cultural and identity considerations in shaping resentment. Another unanswered question is whether, how, and under what circumstances political actors, such as populist radical right parties, attract support based on regional resentment. This would shed more light on its role in shaping the outcome of recent elections.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (431.1 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We express gratitude to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data and replication syntax for this study is available at https://osf.io/j3sr9/?view_only=d26bbfab71374e148474d5e4db2e0d76.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We fielded our survey items in 2017, several years before Munis (Citation2020) was published.

2. We focus on the level of region as the most important large-scale subnational geographical area with which citizens identify (e.g., Antonsich & Holland, Citation2014).

3. Of course, populist parties can appeal to both populist sentiments and regional resentment to attract voters.

4. For the replication syntax for this study, see https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/95HA39. For the data used, see doi.org/10.17026/dans-znu-4wt8.

5. Ten days after the original invitation, which was sent to 10,000 respondents, a further 2500 respondents were invited, this time focusing especially on underrepresented cells of the stratification matrix.

6. Two of three items mention elites and are thus especially likely to tap into generalized anti-elite sentiment. Therefore, we replicate our main analysis using the third item only.

7. When interpreting this correlation, one should consider the fact that this is an estimated correlation after controlling for measurement error. These correlations tend to be higher than the correlations actually observed in the data.

8. Calculated as the average distance to elementary school, high school, library, general practitioner, supermarket, shop and bar. As an alternative measure, we replicate the main analysis using the average distance to the two most basic services, namely, general practitioner and elementary school.

9. The items were: ‘The politicians in Parliament need to follow the will of the people’; ‘The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions’; ‘The political differences between the elite and the people are larger than the differences among the people’; ‘I would rather be represented by a citizen than by a specialized politician’; ‘Elected officials talk too much and take too little action’; and ‘What people call “compromise” in politics is really just selling out on one’s principles’. The answer scale ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

10. The model specifications have a random intercept for both municipality and neighborhood. Because we are interested in the relative importance of explanations, the continuous independent variables have been standardized.

11. It is possible that peripherality does not only matter in a linear way. Appendix D in the supplemental data online presents a replication of the models with a squared term for distance to parliament. The replication yields a pattern that is strikingly similar to that in , suggesting that peripherality matters consistently.

12. The results are almost identical when using the average distance to only the basic services of general practitioner and elementary school.

13. As a robustness check, we replicated the analysis using only the item that does not mention any elites. This resulted in a somewhat (but significantly) stronger effect of peripherality and a somewhat (but significantly) weaker effect of populism. None of the other indicators differed significantly.

REFERENCES

- Agerberg, M. (2017). Failed expectations: Quality of government and support for populist parties in Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 56(3), 578–600. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12203

- Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., & Zaslove, A. (2014). How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comparative Political Studies, 47(9), 1324–1353. doi:10.1177/0010414013512600

- Albertazz, D., & Zulianello, M. (2021). Populist electoral competition in Italy: The impact of sub-national contextual factors. Contemporary Italian Politics. doi:10.1080/23248823.2020.1871186.

- Antonsich, M., & Holland, E. C. (2014). Territorial attachment in the age of globalization: The case of Western Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies, 21(2), 206–221. doi:10.1177/0969776412445830

- Arzheimer, K., & Berning, C. C. (2019). How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and their voters veered to the radical right, 2013–2017. Electoral Studies, 60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004

- Becker, S. O., Fetzer, T., & Novy, D. (2017). Who voted for Brexit? A comprehensive district-level analysis. Economic Policy, 32(92), 601–650. doi:10.1093/epolic/eix012

- Bock, B. B. (2016). Rural marginalisation and the role of social innovation; A turn towards nexogenous Development and rural reconnection. Sociologia Ruralis, 56(4), 552–573. doi:10.1111/soru.12119

- Cramer, K. J. (2016). The politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. University of Chicago Press.

- Cramer Walsh, K. J. (2012). Putting inequality in its place: Rural consciousness and the power of perspective. American Political Science Review, 106(3), 517–532. doi:10.1017/S0003055412000305

- Czaika, M., & Di Lillo, A. (2018). The geography of anti-immigrant attitudes across Europe, 2002–2014. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(15), 2453–2479. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1427564

- Di Matteo, D., & Mariotti, I. (2021). Italian discontent and right-wing populism: Determinants, geographies, patterns. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 13, 371–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12350

- Dijkstra, L., Poelman, H., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2020). The geography of EU discontent. Regional Studies, 54(6), 737–753. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1654603

- Essletzbichler, J. (2018). The victims of neoliberal globalisation and the rise of the populist vote: A comparative analysis of three recent electoral decisions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 73–94. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx025

- Fitzgerald, J. (2018). Close to home: Local ties and voting radical right in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Gavenda, M., & Umit, R. (2016). The 2016 Austrian presidential election: A tale of three divides. Regional & Federal Studies, 26(3), 419–432. doi:10.1080/13597566.2016.1206528

- Geurkink, B., Zaslove, A., Sluiter, R., & Jacobs, K. (2020). Populist attitudes, political trust, and external political efficacy: Old wine in new bottles? Political Studies, 68(1), 247–267. doi:10.1177/0032321719842768

- Guilluy, C. (2019). Twilight of the elites: Prosperity, the periphery, and the future of France. Yale University Press.

- Gutierrez-Posada, D., Plotnikova, M., & Rubiera-Morollón, F. (2021). ‘The grass is greener on the other side’: the relationship between the Brexit referendum results and spatial inequalities at the local level. Papers in Regional Science, 100(6), 1481–1500. doi:10.1111/PIRS.12630.

- Harteveld, E., Van Der Brug, W., De Lange, S. L., & Van Der Meer, T. (2022). Multiple roots of the populist radical right: Support for the Dutch PVV in cities and the countryside. European Journal of Political Research, 61(2), 440–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12452

- Hidalgo, M. C., & Hernández, B. (2001). Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(3), 273–281. doi:10.1006/jevp.2001.0221

- Hochschild, A. R. (2016). Strangers in their own land. Anger and mourning on the American right. New Press.

- Jansson, A. (2013). The hegemony of the urban/rural divide: Cultural transformations and mediatized moral geographies in Sweden. Space and Culture, 16(1), 88–103. doi:10.1177/1206331212452816

- Johnston, R., Manley, D., Pattie, C., & Jones, K. (2018). Geographies of Brexit and its aftermath: Voting in England at the 2016 referendum and the 2017 general election. Space and Polity, 22(2), 162–187. doi:10.1080/13562576.2018.1486349

- Kenny, M., & Luca, D. (2021). The urban–rural polarisation of political disenchantment: An investigation of social and political attitudes in 30 European countries. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 14(3), 565–582. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsab012

- Lee, N., Morris, K., & Kemeny, T. (2018). Immobility and the Brexit vote. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 143–163. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx027

- Lipset, S. M., & Rokkan, S. (1967). Cleavage structures, party systems and voter alignments: An introduction. In S. M. Lipset & S. Rokkan (Eds.), Party systems and voter alignments: Cross-national perspectives (pp. 1–63). Free Press.

- McCann, P. (2020). Perceptions of regional inequality and the geography of discontent: Insights from the UK. Regional Studies, 54(2), 256–267. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1619928

- McKay, L. (2019). ‘Left behind’ people, or places? The role of local economies in perceived community representation. Electoral Studies, 60, 102046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.010

- Mitsch, F., Lee, N., & Morrow, E. R. (2021). Faith no more? The divergence of political trust between urban and rural Europe. Political Geography, 89, 102426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102426

- Mokken, R. J. (1971). A theory and procedure of scale analysis: With applications in political research. Mouton.

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Munis, B. K. (2020). US over here versus them over there … literally: Measuring place resentment in American politics. Political Behavior, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09641-2

- Muštra, V., & Škrabić, B. (2014). Regional inequalities in the European union and the role of institutions. Review of Urban & Regional Development Studies, 26(1), 20–39. doi:10.1111/rurd.12017

- Rachman, G. (2018). Urban–rural splits have become the great global divider. Financial Times, July 30.

- Rodden, J. A. (2019). Why cities lose: The deep roots of the urban–rural political divide. Basic Books.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx024

- Rooduijn, M., Van der Brug, W., & De Lange, S. L. (2016). Expressing or fuelling discontent? The relationship between populist voting and political discontent. Electoral Studies, 43, 32–40. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2016.04.006

- Scala, D. J., & Johnson, K. M. (2017). Political polarization along the rural–urban continuum? The geography of the presidential vote, 2000–2016. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 672(1), 162–184. doi:10.1177/0002716217712696

- SCoRE (Sub-national Context and Radical Right Support in Europe). (2017). Policy brief. www.score.uni-mainz.de/policybrief.

- Stedman, R. C. (2002). Toward a social psychology of place: Predicting behavior from place-based cognitions, attitude, and identity. Environment and Behavior, 34(5), 561–581. doi:10.1177/0013916502034005001

- Stein, J., Buck, M., & Bjørnå, H. (2021). The centre–periphery dimension and trust in politicians: The case of Norway. Territory, Politics, Governance, 9(1), 37–55. doi:10.1080/21622671.2019.1624191

- van Leeuwen, E. S., Halleck Vega, S., & Hogenboom, V. (2021). Does population decline lead to a ‘populist voting mark-up’? A case study of the Netherlands. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 13(2), 279–301. doi:10.1111/rsp3.12361

- Ziblatt, D., Hilbig, H., & Bischof, D. (2020). Wealth of tongues: Why peripheral regions vote for the radical right in Germany (Working Paper). https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/syr84/