ABSTRACT

This paper explores the value of provenance representations in the marketing and promotion of craft beers, which have seen an increase in sales in recent years. A cross-comparative analysis of qualitative data from the labels of 118 craft beers in Wales (UK) and 124 in Brittany (France) identifies an abundant use of cultural representations, especially language, symbols and folklore. Findings point to the value of craft brewing in supporting local economies through social terroir, and consumers’ connections to place, which promote social and economic sustainability, and could be harnessed through marketing strategies to stimulate local beer tourism.

JEL:

1. INTRODUCTION

Beer is the third most consumed beverage worldwide, after water and tea (Patterson & Hoalst-Pullen, Citation2014). Traditionally a locally produced beverage, beer has become dominated more recently by global giants, such AB InBev, or Heineken, who collectively account for over 40% of global sales (Statista, Citation2020). However, while international brands are increasingly evident, recent years have also seen a growing trend towards more local craft beers. SIBA (Citation2020) statistics show an increase in craft beer production from 2.23 million hectolitres (hL) by its members in 2011 to a peak of 2.84 million hL in 2017. The extent of beer production means that some small-scale brewers have even managed to develop global brands, such as BrewDog, which has been effective in its unique marketing (Smith et al., Citation2010).

This surge in craft beer production coincides with consumers’ increasing interest in better quality beers, as well as brewers with strong ethical and environmental credentials (SIBA, Citation2020). Consumers demonstrate a growing demand for authenticity, which is attributed with premium prices (Melewar & Skinner, Citation2020). There has been a move away from the placelessness (Relph, Citation1976) of mass-produced foods to more locally produced authentic products, particularly among higher income consumers (Ellis & Bosworth, Citation2015). This is true for beer, as the number of microbreweries in the UK has almost doubled since 2012 (Brewers of Europe, Citation2020). Provenance, the place of origin, is a core aspect of food as many foods have strong associations of place, evoking expressions of heritage, authenticity and local culture (Tregear, Citation2001). This is evident in the terroir, the unique characteristics derived from the soil, climate, topography and local traditions (Charters et al., Citation2017). This also applies to craft beer, particularly due to the location specificity of the product (Melewar & Skinner, Citation2020), and the social ties to place and community (Sjölander-Lindqvist et al., Citation2020). Such food–territory associations can be marketed as a means to differentiate products (Testa, Citation2011), uniquely branding the product's ‘sense-of-place’ (Hede & Watne, Citation2013), and thereby attract customers’ newly acquired and increasingly sophisticated beverage preferences.

Research on craft beer has spanned entrepreneurship (cf. Ellis & Bosworth, Citation2015; Sjölander-Lindqvist et al., Citation2020), tourism (cf. Cabras et al., Citation2020; Eades et al., Citation2017), economic development (cf. Argent, Citation2018; Cabras & Mount, Citation2016), and branding (cf. Melewar & Skinner, Citation2020; Smith et al., Citation2010). Previous research has looked at how breweries create a sense of place or local identity (Gatrell et al., Citation2018; Hede & Watne, Citation2013; Melewar & Skinner, Citation2020). However, these studies focused on the brand names of beer rather than considering all place representations, such as the text and imagery used on labelling. Additionally, craft beer research has primarily been concentrated in North America (cf. Eades et al., Citation2017; Gatrell et al., Citation2018), and Northern Europe (cf. Cabras et al., Citation2020; Sjölander-Lindqvist et al., Citation2020). Some exceptions include Australia (Argent, Citation2018) and Greece (Melewar & Skinner, Citation2020). This paper differs from previous research on place representations in craft beer, offering unique contributions by adopting innovative methods through analysing images and text on beer labels. It also provides a comparative evaluation of research settings, Wales and Brittany, that have previously been overlooked. Furthermore, while previous research has widely viewed the terroir of beer from a Country-of-Origin (COO) theoretical standpoint, this study considers how resource-based view (RBV) theory aligns with the terroir of craft beers as a means of leveraging a competitive advantage through distinct resources of place.

The aim of this study is to evaluate expressions of provenance in regional craft breweries and explore how these could be used to enhance economic opportunities. Specifically, it develops a cross-comparative analysis of two regions to understand how local craft breweries use representations of place to market and brand their beer, and the extent to which this is a representation of the locality or based on regional or national cultural values. While previous research in this area has concentrated on the brand name, this research investigates the text and imagery used on the label of craft beers, which represent the expression of the brand's identity. The analysis provides insights into ways in which craft beers can be seen as assets for places in supporting local development, whether economic, cultural or social development (Pike et al., Citation2007). The regional focus of the study is Wales and Brittany, two predominantly rural areas within the UK and France, respectively. These two countries possess the highest number of active breweries across the EU (Brewers of Europe, Citation2020). This comparative analysis presents a valuable contribution to research on regional impacts of craft beer between a region known for producing beer (Wales), and one which is more associated with cider (Brittany).

The following sections present a review of relevant literature, primarily focusing on place representations of food, the RBV as the theoretical viewpoint of this paper, and place identity as it relates to craft beer. The methods section aims to justify and promote the analysis of images within research, as well as outlining the rigorous process of analysis. Findings of this analysis are then presented, analysed and discussed to draw conclusions based on the research aims established above.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Foods have close associations with place, to the extent that typical local foods are embedded in the cultural heritage of a location (Tregear, Citation2001). This relationship echoes Relph’s (Citation1976) discussions of a deep sense of place. Foods are strong indicators of the heritage, local traditions, authenticity and the identity of a place (Bowen & Bennett, Citation2020; Tregear, Citation2001), such as the Cornish pasty, which comprises meat in one end and jam in the other. Here, the pasty reflects a connection between the provenance and the mining heritage of Cornwall. Such food–place associations are recognized by geographical indications of foods, such as Protected Destination of Origin (PDO) or Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), which provide intellectual property rights to designated products (Tregear et al., Citation2015). Notable examples include Parma ham or stilton cheese. Beers that benefit from this include Kentish Ale and Rutland Bitter (PGI) in the UK, and Kölsch and Münchener Bier (PGI) in Germany (European Commission, Citation2020).

The provenance of foods can also evoke socio-economic, unique climatic and geographical characteristics of a place (Tregear, Citation2001) as expressed in the concept of terroir. The terroir of food reflects local physical conditions of production, notably the climate, topography, soil and cultural traditions of place (Charters et al., Citation2017). This is true for Champagne, a product closely associated with its region of France. Considering the cultural traditions evident in beer production, such as British traditions for ale, or German wheat beer, this paper argues that terroir can be associated with beer production. The wide variety of beers is indicative of social place characteristics as well as the natural characteristics associated with the ingredients required for beer production. Thus, this paper builds on theoretical perspectives of country-of-origin and terroir, through consideration of place resources and provenance in relation to RBV theory (Barney, Citation1991); a conversation we turn to next.

2.1. RBV theory

RBV theory, based on the VRIN model (Barney, Citation1991), suggests that unique characteristics of terroir provide valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable resources of place to their food products, which provide a distinct identity to the food that cannot be replicated elsewhere. Geographical location and access to raw materials are noted as physical capital resources under Barney’s (Citation1991) categories of resources, underlining that resources of place can be valuable to a business, particularly the unique place resources of terroir. Testa (Citation2011) states that food–territory associations can be used to derive competitive advantage through differentiating or adding value to food products. This is evident with geographical indications, such as PGI. With 29 geographical indications for beer products registered with the European Union (European Commission, Citation2020), the legitimacy of terroir for beer is further supported. Therefore, this paper considers how these unique resources of place can provide craft beer producers with opportunities to distinguish themselves from other local, national and international brands of beer.

Gatrell et al. (Citation2018) underline the opportunities for authentic spatial brands to develop a competitive edge. They note that the spatial branding of localized beers has the potential to attract interest from consumers in a global marketplace, leading to enhanced local economies. The concept of terroir has been debated in relation to beer, most notably by Melewar and Skinner (Citation2020, p. 680), who indicate that it ‘has yet to be widely accepted as a way of conveying authenticity and sense of place for beers’. Sjölander-Lindqvist et al. (Citation2020, p. 151) argue that craft beer derives originality and authenticity through ‘social terroir’, the social ties to place and community, rather than natural resources. Social connections to place represent a significant aspect in establishing and promoting a sense of local identity for beer, which is mostly evident in the beer brand name (Melewar & Skinner, Citation2020). This is consistent with findings of other studies on place branding in relation to beer (cf. Eades et al., Citation2017; Gatrell et al., Citation2018; Hede & Watne, Citation2013; O’Neill et al., Citation2014).

2.2. Place identity and branding

Consumers are increasingly seeking authenticity and engagement with local producers (Bowen & Bennett, Citation2020), which is a manifestation of consumers reconnecting with places, history and culture (Eades et al., Citation2017). Consumers are often prepared to pay premium prices for authentic products, such as craft beer, especially products associated with specific places (Melewar & Skinner, Citation2020; SIBA, Citation2020). This quest for authenticity and local consumption is a rejection of the homogenization of place (Cresswell, Citation2004) and placelessness (Relph, Citation1976) caused by places resembling each other. Globalization has brought a McDonaldization of society (Ritzer, Citation1992), with large multinational chains including McDonald's or Starbucks evident across the world. Indeed, the global beer market is dominated by two large multinational companies, as AB InBev and Heineken account for over 40% of global sales (Statista, Citation2020). Thus, locally orientated and authentic food experiences can be positioned as alternatives to these processes of globalization and homogenization (Ellis et al., Citation2018). Consequently, leveraging the unique resources of place, as ascribed under the RBV (Barney, Citation1991), could provide valuable opportunities for food and drink businesses to underline the authenticity of their products.

Contrary to the authenticity of food–territory relationships, Pike (Citation2009) acknowledges that places are open to social construction, which can be developed through brands or branding. Brands can be a valuable intangible asset for regional development (Suriñach & Moreno, Citation2012). Place and destination branding can be used to develop competitive advantage by creating a narrative to engage internal and external audiences (Colomb & Kalandides, Citation2010). Places can distinguish themselves through strong product images that induce visual expressions of provenance, including landscapes, people and stereotypical rural imagery (Tellstrom et al., Citation2006). Herein, a sense of place is more valuable to craft beers than country-of-origin brand narratives because of the local appeal (Hede & Watne, Citation2013). Thereby developing sense of place narratives through real or imagined heroes, folklores or myths as a valuable way of humanizing the brand (Hede & Watne, Citation2013). However, Gatrell et al. (Citation2018) state that effective spatial brands must leverage a spatial triple helix of place, practice and region to validate and authenticate a spatial brand. To achieve this, beer brands need to capture rich place-based histories that captivate the consumer's imagination through more sophisticated spatial brands.

2.3. Locality and beer tourism

Breweries construct and leverage identity across different tiers of space, using the unique identity of place to capture and share authentic senses of place through multiple levels of localism (Eades et al., Citation2017). Local foods and drinks are considered significant attributes of tourism strategies, building on the traditions, symbols and heritage of food and place (Du Rand et al., Citation2003; Du Rand & Heath, Citation2006). Beer is a traditional product that can be used in many different diversification strategies, as some breweries have been able to develop brands and become sought after destinations (Everett, Citation2016). Such unique selling points enable the owners to create ‘beer tourist pilgrimage destinations’ (Bujdosó & Szûcs, Citation2012, p. 107), that could offer unique visitor experiences. Indeed, craft beer literature identifies tourism as an area in which craft breweries can contribute to local and regional development. Cabras et al. (Citation2020) underline the role of beer festivals in promoting local breweries, acting as an ‘appreciation strategy’ through which consumers identify themselves with their local breweries, akin to the social terroir expressed by Sjölander-Lindqvist et al. (Citation2020). Thus, craft beers form part of a local strategy to promote tourism at regional and subregional levels.

In addition to tourism, previous research on craft beer has also pointed to the potential impact on entrepreneurship and local economic development. Ellis and Bosworth (Citation2015) note the increased entrepreneurial activity of new microbreweries in the UK at a time when the number of pubs was decreasing. This increase in microbreweries has led to increased competition, generating a competitive edge for some businesses, and created opportunities for tourism, including in rural areas. For Sjölander-Lindqvist et al. (Citation2020), the social terroir is the critical ingredient in the appeal of craft beers, underlining how craft beer is contextually situated, linking people, places and businesses. They acknowledge the value of social terroir to the product's local identity and authenticity, and a critical component in the marketing of the product, which can draw benefits to local communities through tourism and awareness of local sustainability. This is particularly true for rural areas, as supported by Argent (Citation2018), who pointed to the growth of rural craft beers in Australia through identifying and exploiting a ‘resource space’, and an interest in locally produced beer. Links with tourism represent benefits to the local community and increased opportunities for craft breweries to reach their target markets.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-comparative research takes an exploratory approach to investigating the use of regional provenance in the marketing and branding of craft beer, using examples from Wales and Brittany. These settings were chosen as places that share similar cultural and geographical characteristics, as predominantly rural areas within the UK and France, respectively, where the food and drink industry is a prominent part of the local economy (Bowen, Citation2019). The UK and France are the top two countries with the highest number of active breweries in Europe (Brewers of Europe, Citation2020), however, differences exist in the perception of both areas in terms of beer production. Although beer would be considered as the most produced beverage in Wales, often linked with place associations such as rugby, Brittany is known for producing cider, and France is more associated with wine. While most research on craft beer focuses on research settings more associated with beer production, Melewar and Skinner (Citation2020) underline the value of terroir and authenticity of a local beer in Greece, a country not naturally associated with beer. Therefore this comparison between Wales and Brittany seeks to analyse the differences in place associations, enhancing knowledge on the value of craft beer production to places that are seemingly less affiliated with beer.

Oriented by pragmatism, the research design is based on the ‘what works’ principle (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2011), and emphasizes producing practical research. As this research aims to investigate the use of provenance in the marketing and branding of craft beer, a qualitative methodology was considered appropriate, analysing the text and images displayed on the labelling of craft beers in Wales and Brittany, whether in the form of a bottle or can. Food labelling is an important source of information for consumers about the production process and identity of the product, such as beer, as the type of beer depends on the production process. While the labelling on beer bottles or cans provides information about the type of beer, its origins and the brand, this is an underused source of data in beer-specific research. As such, this research distinguishes itself from previous studies on place representations of craft beers through using data gathered from the text and images of beer labels. Previous research has included labelling as part of data collection on place representations of craft beer, but this has been accompanied by text and image data drawn from company websites (Hede & Watne, Citation2013).

Text is a commonly used form of data in qualitative research; however, the use of images is only recently gaining traction in social sciences, but is an increasingly accepted method in tourism research (Balomenou & Garrod, Citation2019), an area to which research on regional provenance belongs. The use of images in this research on marketing and branding is significant, as Pink (Citation2013) points to visuals as one of the most persuasive and pervasive sources of human sensorial experience. Here, beer labels from craft breweries in Wales and Brittany were identified, photographed and documented in NVivo 12.

To begin the comparative analysis, we developed a database of craft brewers in Wales and Brittany, based on two key criteria: production of less than 6 million barrels a year, and less than 25% of the brewery being owned or controlled by an alcohol industry member that is not a craft brewer (Brewers Association, Citation2020). A robust process was used to establish the databases, using official documents relating to food and drink producers in each region, with these confirmed through national government websites in each country. This led to a database of 118 active craft breweries in Wales and 124 in Brittany.

Following a robust process of first and second cycle coding (Miles et al., Citation2014), images and text of the labelling of all beers associated with each brewery were documented and coded in NVivo 12. A total of 717 beers were documented in Wales, and 726 in Brittany. Initially, directed content analysis was conducted to evaluate frequencies of the use of cultural representations on the labelling. This method is consistent with previous research on the branding of craft beers (cf. Eades et al., Citation2017; O’Neill et al., Citation2014). Additionally, thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) was conducted to further evaluate the use of images and text on the labelling, in understanding the types of images and text used in marketing and branding the beer. This method is consistent with food place branding research (Bowen & Bennett, Citation2020). Text and image data were analysed separately through the same process, before all data was gathered for collective interpretation, as presented in the findings section.

4. FINDINGS

4.1. Beer brand provenance indicators

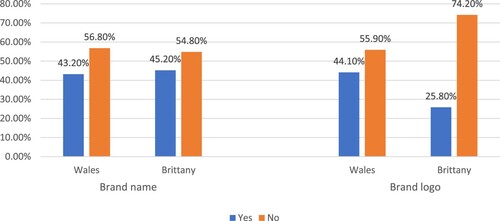

An initial analysis phase looked at provenance indicators in the names and logos of the beer brands, as these are the main expressions of identity of the company. Among the 118 craft beer brands in Wales, 51 (43.2%) included provenance indicators in their brand name, compared with 56 of the 124 brands in Brittany (45.2%) (). These mostly included place names, whether making reference to specific places within the region, or the region itself. Differences were observed for brand logos, with 52 of the 118 brands (44.1%) in Wales possessing provenance indicators in their logo, compared with only 32 of the 124 brands (25.8%) in Brittany. These primarily included symbols relating to the region. In Wales, this comprised images of dragons, daffodils or sheep, as recognized visual indicators of place for Wales. For Breton beers, this is mostly manifested through a canton ermine (Breton symbol), an outline of the map of Brittany or depictions of Breton legends, such as fairies associated with the Brocéliande forest.

Analysis of the images and text of the 717 beers in Wales and 724 beers in Brittany found that provenance images and text were evident on the labelling of all beers from Wales (100%). However, in Brittany 9.4% of the beers contained no provenance images, and 22.9% contained no text relating to provenance.

4.2. Thematic analysis

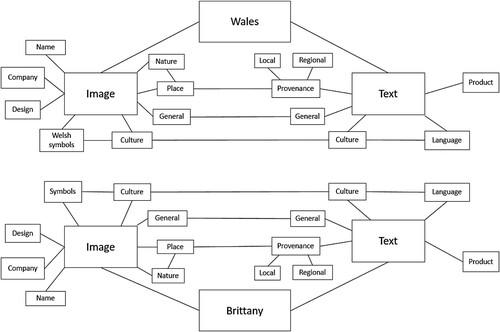

Following the six-step process of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), codes were generated for both image and text data in Wales and Brittany, which were used to generate themes. Initially, 1168 codes were generated from image data of Welsh beers, which equated to 30 unique codes, including place imagery, location outlines and mythological images. These codes were then grouped into eight themes: nature, place, general, culture, Welsh symbols, design, company and name. The themes capture the various place representations expressed in the images, from showing the brand name, logo or company information to specific cultural expressions of place. These are presented in the thematic map shown in , along with themes from text data in Wales, and both image and text data from Brittany. Text data from Wales initially produced 1375 codes, which equated to 16 unique codes, once duplicates were removed. Among these were place names, place descriptions and references to industrial heritage. These codes were grouped into five themes: product, language, culture, general, and provenance, which can be divided into subthemes of local and regional provenance. Image data from Brittany generated 26 unique codes from 1847 initial codes, leading to eight themes (), which resembled those seen in Wales for image data, except that the symbols theme was not specific to Breton symbols, but also included symbols relating to France. Many image codes related to the sea, rural imagery and Breton symbols. Text data produced 16 unique codes from Breton beers, from 1445 initial codes. These initial codes include local place names, exotic names and Breton words. These were transferred into the same five themes as those for Welsh text data, namely, product, language, culture, general and provenance, with the latter including subthemes of local and regional provenance. Text themes also express wide variations including product information, generic branding and specific cultural place representations. The thematic map outlines the themes derived from all data, as well as the relationships that exist between the themes, such as links between culture and language, or nature to place.

4.3. Image themes

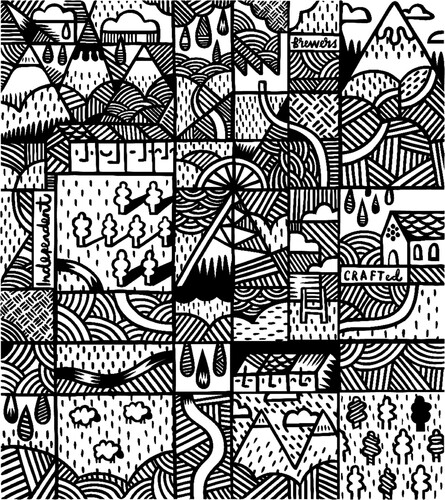

Themes derived from image data show that beers in both Wales and Brittany used a variety of different visual cues on the labelling of their beers. Provenance was a significant aspect of this, with the themes of nature, place, culture and symbols all highlighting visual representations of the provenance of the beer, whether on a local or regional scale. Nature was a common theme across both research settings, as label images depicted the value of the natural local landscape, notably images of Snowdonia or the Pembrokeshire coast park in Wales, as well as numerous depictions of the sea or coastline in Brittany, as a region surrounded by the sea. Place depictions were mostly seen on a local level, such as the Cardiff skyline or castles, but also represented the region as a whole, such as the outline of the map of Brittany. Cultural representations were strong indictors used in both regions, including the cultural and industrial heritage of both regions. This is highlighted in , the label of a beer brand from the South Wales valleys, which is a mosaic of artistic cultural representations of the area, including rugby posts, the headstocks and wheel of a coal mine, a factory, and other representations of place, including rivers, mountains, sheep and rain. Indeed, some of these aspects could be considered as place stereotypes (Tellstrom et al., Citation2006). Place and cultural symbols were also prominent in beer labelling imagery. Welsh symbols, such as dragons, daffodils or the Prince of Wales’s logo were common on Welsh beer labelling, while Breton labelling included some Breton symbols, such as the ermine canton, as well as more generic Celtic symbols not specific to Brittany, including Celtic knots, crosses or a triskele. The flags of Wales and Brittany were also used as place depictions on many beer labels.

Figure 3. Beer label depicting cultural representations of South Wales.

Source: Grey Trees (Citation2022).

Some provenance depictions were also evident through the company logo, which varied between companies, but sometimes included place-specific images, notably local landmarks. shows that depictions of place in the brand logo were more evident in Wales (44.1%) than Brittany (25.8%). Alternative brand logo images were more generic, based on general designs, and images unrelated to the name of the product or brand. Two other themes from image data point to images not related to provenance. These are the design and name themes. As with the brand logo, these are based on generic images, which are not related to the name of the product or brand. Common design images were general shapes, animal images not associated with the beer, and simplistic designs where the text of the beer name took prominence. The name theme refers to images that relate to the name of the beer, some of which relate to provenance, others to generic names.

Other notable images on the labelling of some Breton beers were the logo of the Produit en Bretagne origin brand, and the official logo certifying an organic product. This is an official origin brand and association established in Brittany, comprising over 420 company members across a range of industries (Produit en Bretagne, Citation2020). Findings show that 75 beers included the Produit en Bretagne logo on their labelling. The organic produce certification logo was carried by 138 beer labels.

4.4. Text themes

As with the image data, themes for the text data were identical for Welsh and Breton beers. Product was the most prominent theme, as the majority of beer labels included descriptions of the product, including the type of beer and production process. This often focused on the style of beer, referring to various international types of beer, including American pale ale, English stout or Kölsch. Product names often reflect the beer type. For one Breton beer company, their range of international-type beers was associated with a ‘so British’ identity, with the beers including English names and English text on the labelling.

Language was a notable theme, due to the two regions possessing their own languages. Beers in Wales included text in English, Welsh or both, with the Welsh language being an important cultural marker of the identity of a wide variety of beers, particularly in areas of Wales where Welsh language is more prominent, thus acting as a representation of place. In Brittany, Breton was used as part of a distinct identity with some beers, including representing identities of place, but French was the most significant language. A number of beers included English names and text on their labelling, as part of a more generic brand identity, with no provenance indicators. Culture was another prominent theme, particularly in representing regional cultural representations. For Wales, this included references to Welsh mythology, rugby, or industrial heritage. Myths and legends were also evident in Brittany, as well as references to Brittany's maritime heritage. The general theme accounts for the inclusion of general text data, which had no provenance indicators. This includes exotic beer names and the use of colours in naming beers, evident in Brittany, and the use of play on words expressions among some Welsh beers.

Finally, the provenance theme was common in both Wales and Brittany, observed from a local, regional and national perspective. Local provenance representations were evident in the use of local place names in the beer names, and the descriptive information provided on labels. This was evident for the name of the locality where the beer was produced, but also made reference to significant places of interest, such as the Brocéliande forest in Brittany, or Snowdonia National Park in Wales. While some beers favoured referencing their specific location, others emphasized regional provenance. In Brittany, this often included text accompanying the Produit en Bretagne brand logo. Although no origin logo exists in Wales, several beers included variations of ‘Made in Wales’ on their labelling, making reference to the industrial heritage through the phrases ‘Nailed in Wales’ and ‘Handcrafted in Wales’.

5. DISCUSSION

Findings from this research illustrate that many craft beers in both research settings use provenance representations on their labelling to promote their beers, supporting findings from previous studies that craft beers can establish and promote a sense of identity through provenance indicators (Eades et al., Citation2017; Gatrell et al., Citation2018; Hede & Watne, Citation2013; Melewar & Skinner, Citation2020; O’Neill et al., Citation2014). Provenance representations are evident both in the images and text included on the labelling, however analysis acknowledged some beers possess no place representations, favouring generic text or images. Findings indicate the majority of beer brands observed in this research used provenance indicators in their brand, consistent with findings by Melewar and Skinner (Citation2020).

The use of provenance in labelling was also prominent, with cultural representations of place, such as place names, local landmarks, or regional myths, legends and customs, which evoke strong expressions of place (Tellstrom et al., Citation2006). Although craft beers from both regions widely use local and regional cultural representations of place, observations point to Breton beers showing a greater expression of their specific locality, while many Welsh beers displayed a Welsh identity. Language was a notable aspect of Welsh beers, as a sign of the use of Welsh language in society. Welsh was very prominent in the branding of the brewery and on its labelling, and was the main language on labelling for many beers. This could be observed largely in areas where the Welsh language is more prominent, such as North West and South West Wales, indicative of the hyperlocal focus that some breweries took in their identity. The use of text and images relating to specific places enables craft breweries to draw upon the unique place identities and terroir, particularly social terroir, that stems from a specific locality. This hyperlocal focus can be advantageous as it limits the number of breweries that could use the same place identity. For example, rural villages where only one craft brewery exists could provide a unique identity to a local brewery using place representation on its beer labelling, whereas breweries using more regional identities for Wales or Brittany face competition from other craft beers that carry the regional identity, and could limit the awareness of the brand identity. However, the reach of a hyperlocal brand identity may be limited (Argent, Citation2018), as consumers that are unaware of its locality may not resonate with the place identity of the craft beer. We return to this point further below.

The use of provenance indicators in the craft beer data is consistent with literature on the marketing of food products, underlining the connection between food and the local heritage and identity of a place (Bowen & Bennett, Citation2020). Considering the theoretical underpinnings of the RBV, the various place representations expressed in beer labelling align with the product terroir. This is mostly manifested in the local traditions and customs relating to the food production process, as the brewing process is based on the specific approach that the brewery takes to producing its beer. Additionally, unique place characteristics are also evident in the climatic conditions in which the hops are grown, and unique qualities of the water used, which could be particularly advantageous in mountainous areas. Therefore, place indicators that promote these could enhance consumers’ perceptions of the qualities of the beer. This could be evident in Snowdonia in Wales, an area that possesses a notable identity as a national park, which could bring perceptions of natural qualities and valuable terroir, such as in the water used in producing the beer. Several craft beers observed in this area used the Snowdonia identity on their labels.

The inclusion of organic certification logos on some Breton beers likely contributes to the perceived quality of these beers in the minds of some consumers, particularly those who value organic production. Organic beer could be seen to have strong connections with the terroir, as they are based on natural processes and resources. Such production of beer is rare, which further underlines the unique local production process. Similarly, the various cultural markers evident in the data can emphasize the local production process, and provide unique place distinctions of the products. These place representations act as an important resource for breweries in differentiating their beers, and can provide a competitive advantage (Testa, Citation2011), particularly providing authentic brands with an edge in a competitive market (Gatrell et al., Citation2018). Although none of the beers in this research possessed a protected food status, several European beers possess this status. Obtaining geographical indications could be an important strategy in protecting the qualities of certain beers, and enhancing the reputation of a place for beer production, based on the local terroir. This is evident in the food industry with Scotch whisky, or French wine. Indeed, the general reputation of Wales for food production has been advanced in recent decades through the acquisition of 15 protected food names (Bowen & Bennett, Citation2020).

Although the use of provenance indicators supports previous literature on the subject, the findings qualify distinctions between place representations on a local, regional or national scale. The notion of social terroir (Sjölander-Lindqvist et al., Citation2020) was widely observed in the data, in that originality and authenticity are derived from social connections to place. This implies that place representations would be most appreciated by those who can relate closely with this identity, and those with limited awareness of the identity may be less likely to appreciate the value of the identity to the authenticity of the product. Local craft beers appeal to consumers in close proximity to their place of origin as they could relate to the specific place representations, but regional or national beers are more likely to achieve higher levels of awareness as their place representations would appeal on a wider scale. This has implications on the focus of the company to local, regional, national or international markets, as well as consumer awareness of the brands. The homogenization of place (Cresswell, Citation2004) reinforces a level of comfort and assurance in brands that are well-known, leading to greater awareness of international brands, and less awareness of smaller local brands. For beer this is evident in the dominance of AB InBev and Heineken in the global market (Statista, Citation2020). BrewDog has shown that beer brands can grow from small-scale production to large international success (Smith et al., Citation2010).

Given their increasing popularity, craft beers could be valuable place assets in promoting awareness of a place, or region, and developing a reputation for food and drink. Places could enhance their reputation for beer through promoting notable or unique examples, such as the tradition of the Felinfoel brewery in Llanelli, Wales, which is noted as the first brewery ever to produce beer in cans, linked to the town's tinplate industry. From a RBV perspective, this underlines the terroir (including social terroir) that exists in some places through unique social or historical connections to place. Such characteristics and unique resources should be emphasized within the labelling and branding which can enhance the authenticity of the beer in the eyes of the consumer, and provide distinctive advantages in the marketing of the beer. Additionally, places could look to promote and protect their identity for craft beer through geographical indications. Policymakers could look to develop a strategy for obtaining geographical indications for beer producers within the region or country, as this could develop a positive reputation for beer. Alternatively, craft beers could be supported by place brands, such as the Produit en Bretagne brand in Brittany, which has reinforced the reputation of the region for food and drink production (Bowen & Bennett, Citation2020). This place brand could be seen to enhance awareness of the social terroir of products from Brittany to consumers from outside the region, which acts to widen the awareness and potential market for Breton products. Suriñach and Moreno (Citation2012) point to the value of intangible assets, such as a brand, to regional development.

Craft beers that emphasize local provenance serve the demand for localized beers (Hede & Watne, Citation2013), and help consumers to reconnect with their localities (Gatrell et al., Citation2018). Thus local and authentic aspects of craft beer brands could align with food tourism strategies, building on representations of heritage of food to place (Du Rand et al., Citation2003; Du Rand & Heath, Citation2006). There is value in beer festivals promoting craft beers, enabling consumers to identify themselves with local breweries (Cabras et al., Citation2020), and developing local economic value through attracting tourists and raising awareness of local craft beers. Craft beer producers could also seek connections with other craft brewers to form part of a craft beer trail. This could attract tourists to sample a variety of local beers aligned to the notion of ‘beer tourist pilgrimage destinations’ (Bujdosó & Szûcs, Citation2012, p. 107). This could be linked to craft beer festivals or more general events, such as the annual Festival Interceltique de Lorient in Brittany, which celebrates the cultural traditions, especially food and drink, of Celtic regions.

Research findings have pointed to different opportunities for craft breweries to draw on the place resources associated with terroir, notably social terroir, to promote their beers. Differences are observed in the types of markets to which craft beers could appeal, depending on the identity of the brand and how this would align with local development or tourism prospects. explores the different identities observed among craft beers in this research, exploring development opportunities for beers according to their local, regional, national or international identity. Specifically, it evaluates how the identity of the craft beer relates to provenance, awareness of the identity, the potential market for the craft beer, and the opportunities for growth that could be derived from this identity, should the craft brewery seek growth. Provenance indicators are more likely to be seen by local, regional or national brands, with many international brands likely to take a generic identity. This was observed in the research findings through using more generic designs that had no specific provenance indications. Awareness differs on each level, depending on the reach of the beer brand and its marketing activities. This also relates to the social terroir of the craft beer, and how consumers associate its social ties to its place of origin. Awareness of places and their meanings would have a bearing on how consumers could relate to brands that carry place representations, with a hyperlocal identity, such as a specific village or suburb, potentially limiting the awareness of consumers to a local or regional scale, while regional or national identities, such as Breton or Welsh, may derive awareness and appeal on a wider scale. Consequently, the type of market that a brand would engage in would depend on awareness, as brands with a more localized identity may not derive awareness or appeal beyond a regional level. However, all brands have the opportunity to achieve growth on all levels, even rapid international growth, as experienced by BrewDog, although slower incremental growth is more likely, depending on the resource allocation of the company. As previously suggested, localized beers could be part of tourism trails or beer festivals as a means of raising awareness and engaging with tourism businesses. This could be expanded on regional or national scales, with increased awareness developing new opportunities for growth. Provenance indicators, such as the Produit en Bretagne brand could add value in developing increased awareness beyond the geographical level of the business.

Table 1. Opportunities and challenges for beer brands according to their identity.

Finally, pubs are recognized as the heart of many communities, and play an important role in local economies, particularly in rural areas (Mount & Cabras, Citation2016). A recent decline in the number of public houses has affected local communities, impacting jobs and business opportunities (Cabras & Mount, Citation2016; Ellis & Bosworth, Citation2015). However, the increasing frequency and popularity of craft beers underline the changing nature of beer consumption, and present entrepreneurial opportunities for local craft brewers (Ellis & Bosworth, Citation2015). As seen in , craft brewing can derive economic value from its provenance, initially in developing sales locally, with potential for growth, particularly through tourism. A local, regional, or national identity has the potential to resonate with consumers on these scales and instil a sense of place, encouraging consumers to support local businesses. Thus, the social terroir is valuable in helping craft breweries promote social and economic sustainability (Sjölander-Lindqvist et al., Citation2020), and promote sales of local craft beers. Argent (Citation2018) points to the positive roles of craft breweries in engendering social, symbolic and financial capital for places, encouraging local government, regional development agencies and rural tourism boards to develop tourism strategies that capitalize on the increasing popularity of craft beer, and its potential to make a meaningful contribution to local economies. The literature points to great potential for beer tourism, as some breweries develop brands and become destinations (Everett, Citation2016), while beer festivals offer unique visitor experiences (Bujdosó & Szûcs, Citation2012), and help consumers identify with local breweries (Cabras et al., Citation2020).

6. CONCLUSIONS

This research supports previous findings that craft beers can develop and exploit provenance representations (Gatrell et al., Citation2018; Melewar & Skinner, Citation2020). However, this research attempts to go further by raising questions about the value of the focus of provenance representations to craft beers, through understanding how their level of identity could equate to awareness, potential markets, and opportunities for business growth. This differs from previous research that focused on territorial management of beer brands, which have failed to address questions of the level of locality and how this impacts brand identity. To that end, this research has highlighted differences in the level of locality of place representations, and advances previous studies that have demonstrated how craft breweries can promote a sense of local identity through the brand (e.g., Hede & Watne, Citation2013). This study questions whether hyperlocal place representations would derive the same strength as a brand possessing a regional or national identity, as this offers opportunities in expanding the business reach into newer markets, whereas awareness of specific localities may not carry meaning for consumers. As such, the level of focus of the brand identity reflects the strategic focus of the company. This could be especially significant in the wake of challenging economic conditions, such as the Coronavirus pandemic, as businesses have experienced constrained business activities. Opening up to international markets offers businesses with opportunities to spread the business risk across different markets, therefore awareness on an international scale would be advantageous, and more likely to be achieved where consumers are more aware of the place used in provenance indicators. Findings point to the value of craft beers as an asset in supporting local economies through social terroir, with opportunities for strategic approaches to promote tourism, such as through local beer festivals, or beer tourism trails. Further advantages could be derived by policymakers in supporting the development of geographical indications in protecting the unique qualities that some beers could derive from its place identity, or through origin brands, which could enhance the local reputation for beer production, and food more generally, and encourage tourism. Development strategies, whether economic, cultural or social development (Pike et al., Citation2007), should consider the scale of the intended impact and whether engaging with local, regional, national, or internationally focuses craft beers would be best suited.

Contributions of this research are seen in taking a comparative approach, with differences observed between beer brands in Wales and Brittany in their use of cultural representations, and particularly in the way they distinguish themselves using their provenance and locality, as many Breton beers tended to focus on a hyperlocal level, while Welsh beers used the Welsh language and cultural symbols more prominently in marketing, providing many beers with a Welsh identity. Findings imply that local craft beers can have a positive impact on the local economy in places that are not notorious for beer production, as the popularity in the production and consumption of craft beer is seen in many places. This could be true for Brittany, which is largely recognized for its cider production, yet possesses a growing craft beer sector. Similarities observed between the regions imply that findings could be generalized and applied to other places, as craft beer could be an asset to any region, and an integral part of development strategies, particularly food or tourism strategies. A methodological contribution was also evident in the use of image and text data derived from beer labelling, as a significant manifestation of the identity of beer brands. Limitations are acknowledged in the scope of the study in evaluating the use of provenance representations in the marketing of beers, but not exploring the economic value that this adds to beer brands, such as whether the use of provenance representations actually translates into increased sales. Additionally, the large sample size within the study would be appropriate for quantitative research, possible exploring a correlation between image and place. Research into levels of locality, is an area for future research, and would be beneficial in understanding the value of place representations. In particular research could explore this from an economic perspective to better understand how the use of different levels of provenance representations could add value to the brand.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

REFERENCES

- Argent, N. (2018). Heading down to the local? Australian rural development and the evolving spatiality of the craft beer sector. Journal of Rural Studies, 61, 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.01.016

- Balomenou, N., & Garrod, B. (2019). Photographs in tourism research: Prejudice, power, performance and participant-generated images. Tourism Management, 70, 201–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.08.014

- Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Bowen, R. (2019). Motives to SME internationalisation: A comparative study of export propensity among food and drink SMEs in Wales and Brittany. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 27(1), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-08-2018-0125

- Bowen, R., & Bennett, S. (2020). Selling places: A community-based model for promoting local food. The case of Rhondda Cynon Taf. Journal of Place Management and Development, 13(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-10-2018-0081

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brewers Association. (2020). Craft brewer definition. https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/craft-brewer-definition/

- Brewers of Europe. (2020). The contribution made by beer to the European economy. https://brewersofeurope.org/uploads/mycms-files/documents/publications/2020/contribution-made-by-beer-to-EU-economy-2020.pdf

- Bujdosó, Z., & Szûcs, C. (2012). Beer tourism – From theory to practice. Academica Turistica, 5(1), 103–111.

- Cabras, I., Lorusso, M., & Waehning, N. (2020). Measuring the economic contribution of beer festivals on local economies: The case of York, United Kingdom. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(6), 739–750. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2369

- Cabras, I., & Mount, M. (2016). Economic development, entrepreneurial embeddedness and resilience: The case of pubs in rural Ireland. European Planning Studies, 24(2), 254–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1074163

- Charters, S., Spielmann, N., & Babin, B. J. (2017). The nature and value of terroir products. European Journal of Marketing, 51(4), 748–771. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-06-2015-0330

- Colomb, C., & Kalandides, A. (2010). The ‘Be Berlin’ campaign: Old wine in new bottles or innovative form of participatory place branding? Edward Elgar.

- Cresswell, T. (2004). Place: A short introduction. Wiley.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE.

- Du Rand, G. E., & Heath, E. (2006). Towards a framework for food tourism as an element of destination marketing. Current Issues in Tourism, 9(3), 206–234. https://doi.org/10.2167/cit/226.0

- Du Rand, G. E., Heath, E., & Alberts, N. (2003). The role of local and regional food in destination marketing: A South African situation analysis. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 14(3–4), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49852-2_5

- Eades, D., Arbogast, D., & Kozlowski, J. (2017). Life on the ‘beer frontier': A case study of craft beer and tourism in West Virginia. In Kline, C., Slocum, S., & Cavaliere, C. (Eds.), Craft beverages and tourism, Vol. 1. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49852-2_5

- Ellis, A., Park, E., Kim, S., & Yeoman, I. (2018). What is food tourism? Tourism Management, 68, 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.03.025

- Ellis, V., & Bosworth, G. (2015). Supporting rural entrepreneurship in the UK microbrewery sector. British Food Journal, 117(11), 2724–2738. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2014-0412

- European Commission. (2020). eAmbrosia – The EU geographical indications register. https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/food-safety-and-quality/certification/quality-labels/geographical-indications-register/#

- Everett, S. (2016). Food and drink tourism: Principles and practice. SAGE.

- Gatrell, J., Reid, N., & Steiger, T. L. (2018). Branding spaces: Place, region, sustainability and the American craft beer industry. Applied Geography, 90, 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.02.012

- Grey Trees. (2022). Grey Trees brewery. https://greytreesbrewery.com/.

- Hede, A.-M., & Watne, T. (2013). Leveraging the human side of the brand using a sense of place: Case studies of craft breweries. Journal of Marketing Management, 29(1–2), 207–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2012.762422

- Melewar, T. C., & Skinner, H. (2020). Territorial brand management: Beer, authenticity, and sense of place. Journal of Business Research, 116, 680–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.038

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis. SAGE.

- Mount, M., & Cabras, I. (2016). Community cohesion and village pubs in Northern England: An econometric study. Regional Studies, 50(7), 1203–1216. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.989150

- O’Neill, C., Houtman, D., & Aupers, S. (2014). Advertising real beer: Authenticity claims beyond truth and falsity. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 17(5), 585–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549413515254

- Patterson, M. W., & Hoalst-Pullen, N. (2014). Geographies of beer. In Patterson, M. W., & Hoalst-Pullen, N. (Eds.), The geography of beer. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7787-3_1

- Pike, A. (2009). Brand and branding geographies. Geography Compass, 3(1), 190–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00177.x

- Pike, A., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2007). What kind of local and regional development and for whom? Regional Studies, 41(9), 1253–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701543355

- Pink, S. (2013). Doing visual ethnography. Sage.

- Produit en Bretagne. (2020). Produit en Bretagne: Les chiffres clés. http://www.produitenbretagne.bzh/les-chiffres-cles

- Relph, E. C. (1976). Place and placelessness. Pion.

- Ritzer, G. (1992). The McDonaldization of society. Pine Forge.

- SIBA. (2020). The SIBA British craft beer report 2020.

- Sjölander-Lindqvist, A., Wilhelm, S., & Daniel, L. (2020). Craft beer – Building social terroir through connecting people, place and business. Journal of Place Management and Development, 13(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-01-2019-0001

- Smith, R., Moult, S., Burge, P., & Turnbull, A. (2010). BrewDog: Business growth for punks! The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 11(2), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000010791291785

- Statista. (2020). Global market share of the leading beer companies in 2019, based on volume sales. https://www.statista.com/statistics/257677/global-market-share-of-the-leading-beer-companies-based-on-sales/

- Suriñach, J., & Moreno, R. (2012). Introduction: Intangible assets and regional economic growth. Regional Studies, 46(10), 1277–1281. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.735087

- Tellstrom, R., Gustafsson, I.-B., & Mossberg, L. (2006). Consuming heritage: The use of local food culture in branding. Place Branding, 2(2), 130–143. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.5990051

- Testa, S. (2011). Internationalization patterns among speciality food companies: Some Italian case study evidence. British Food Journal, 113(11), 1406–1426. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701111180012

- Tregear, A. (2001). What is a ‘typical local food’?: An examination of territorial identity in foods based on development initiatives in the agrifood and rural sectors. Centre for Rural Economy, University of Newcastle upon Tyne.

- Tregear, A., Török, Á, & Gorton, M. (2015). Geographical indications and upgrading of small-scale producers in global agro-food chains: A case study of the Makó onion Protected Designation of Origin. Environment and Planning A, 48(2), 433–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15607467