ABSTRACT

This paper further explores the novel concept of the opportunity space, which refers to the limits and possibilities of regional development trajectories and the idea of deliberative agency. Opportunity spaces are formed, perceived and used by individual agents or groups of agents and serve as a bridge between structure and agency. Drawing on six comparative case studies from Finland, Norway and Sweden, the study introduces a conceptual framework to investigate how actors search for and construct opportunities in regions by linking opportunity spaces to social filters that frame their perception.

1. INTRODUCTION

In their provocative paper, Amin and Thrift (Citation2000, p. 4) maintain that economic geography can no longer ‘fire the imagination’ of researchers. Since then, rapidly emerging evolutionary approaches have provided a new impetus for research. Over the last two decades, the question of how cities, regions and industries evolve over time has become central to regional studies and economic geography. Subsequent studies in the tradition of evolutionary economic geography have focused on the path development of industrial evolution, its place-dependent nature and its manifestation in cities and regions (Boschma & Wenting, Citation2007; Martin & Sunley, Citation2006). These studies have argued that industrial change is framed and shaped by history and existing industrial structures, causing industries and entire regions to remain locked into past development paths (Grabher, Citation1993). Against this backdrop, several evolutionary studies have argued for a deeper understanding of how actors shape regional development trajectories (Dawley, Citation2014; Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2013). As Hassink et al. (Citation2019, p. 3) summarized, ‘new growth paths are created through multiple actors’ activities’.

Studies in the institutional tradition have focused on how institutions mediate local and regional development in subtle but pervasive ways (Gertler, Citation2010; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013). The institutional approach has, however, remained too abstract to contribute more fully to regional development studies (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013, p. 1037). Institutions are usually viewed top-down in terms of the general ‘rules of the game’ (Gertler, Citation2010). Sotarauta (Citation2017) argues that a bottom-up analysis of institutions would deepen our understanding of how actors and institutions interact. Institutions condition agency, and people work to change the institutions in which they are embedded (Battilana et al., Citation2009). Still, regional development studies have tended to focus on either institutions or agency.

Arguing that we must look beyond the dialectical structure–agency relationship and identify conceptual bridges between evolutionary and institutional approaches, Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) suggest a dynamic approach ‘to examine structures in relation to action and action in relation to structure’ (Jessop, Citation2001, p. 1223). Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) further suggest that the concept of an opportunity space will facilitate an exploration of the interplay between structure and agency. For example, it might help to identify how particular structural factors condition the actors constructing, perceiving, and exploiting opportunities in specific places and times while also acknowledging how the same actors contribute to the formation of new structures over time. Structural properties are thus considered both as medium and outcome of activities and agency in the region (cf. Giddens, Citation1979).

Given the current lack of research on the connection between regional opportunity spaces, agency and regional development, there is a need to develop the concept of the opportunity space further. Consequently, this article continues the discussion initiated by Scott and Storper (Citation1987) and Boschma (Citation1997) on opportunities and regional preconditions when explaining the spatial patterns of emerging industries and related opportunities. Boschma (Citation1997) argues that ‘windows of locational opportunity’ unravel or expand in conjunction with emerging business opportunities and industries. Our objective is to explore the concept of the opportunity space, focusing in particular on perceived opportunities. To that end, we address the following research questions:

How can the concept of the opportunity space be operationalized in the context of regional development?

What are the key factors that frame opportunity spaces?

How are perceived opportunity spaces shaped?

2. OPPORTUNITY SPACE

2.1. The basic tenets of opportunity

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, opportunity is ‘a time or set of circumstances that makes it possible to do something’. It is an intuitive concept that has been approached in several distinct ways.

In business studies, a ‘window of opportunity’ refers to the optimal timing for market entry based on a product lifecycle (Suarez et al., Citation2015). Innovation studies refer to ‘white spaces’ and ‘adjacent possibilities’ at different scales (e.g., between existing related industries and clusters) as sources of innovation (Cooke & Eriksson, Citation2012; Johnson, Citation2010). The concept of ‘policy windows’ describes, in policy studies, periods that afford opportunities for advocates to advance their goals (Kingdon, Citation1984). Entrepreneurship research discusses the epistemology of perceived opportunities. Notably, Alvarez et al. (Citation2010) distinguish between realist, constructionist, and evolutionary approaches. The realist perspective assumes that opportunities are ‘out there’, waiting to be observed and used by those possessing necessary qualities and the best knowledge of reality. In contrast, the constructionist perspective views opportunities as individuals’ constructions, which are based on the interpretation of raw data, phenomena, and available resources. By assigning meanings, be they rational or emotive, that differ from one person to the next, individuals create their own realities, which orient their actions. The evolutionary realist combines these two approaches. Individuals create new opportunities through action. Action provides feedback, serving as a reality check that causes actors to adjust and readjust their behaviour continually. According to the evolutionary view, opportunities are emergent and path dependent.

As applied in regional development contexts, the concept of the opportunity space refers to the limits and possibilities of regional development in a specific place at a certain point in time (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). In economic geography, Scott and Storper (Citation1987) introduced the concept of a ‘window of locational opportunity’, referring to times when new fast-growing industries appear to a region and how these moments may release regions from many locational constraints (Storper & Walker, Citation1989). Boschma (Citation1997) and Boschma and Van der Knaap (Citation1999) used the same concept but emphasized the relevance of spatial conditions and chance. A window of locational opportunity differs from the regional opportunity space, which has a more continuous temporal nature. Additionally, the use of the latter is not restricted to a narrow range of new technologies and industries.

Grillitsch et al. (Citation2021) connect the concept of the regional opportunity space to regional industrial path development. Because the domain is not an individual but a region, the concept refers to a field of opportunities encompassing different types of path development. Grillitsch et al. (Citation2021) identify space and industry structure as distinct dimensions of the regional opportunity space. Space refers to a concrete geographic space as the local arena for learning and knowledge exchange, as well as to abstract economic space, which is not confined to a specific region but includes technologies and knowledge that may, in principle, be accessed by anyone. The second dimension, industry structure, refers to regional specialization and related or unrelated variety (Frenken et al., Citation2007). The systemic view of regional opportunity spaces aims to support the analysis of the circumstances and structural preconditions that limit or enable regional possibilities for path development. In a further development of the concept, Grillitsch and Sotarauta’s (Citation2020) region-specific opportunity space refers to what is possible considering regional preconditions, including industrial structures and institutional environment (e.g., innovation support systems), as well as informal institutions such as entrepreneurial climate and knowledge networks (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020, pp. 715–716). With respect to specific opportunities, region-specific characteristics may be supportive, constraining, or neutral.

Moreover, Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) identify a time-specific opportunity space. This term describes what is possible at a specific point in time based on existing knowledge, technologies, institutions, resources, and emerging demand in the global market. This broadly corresponds to a realist perspective and the ‘absolute’ abstract economic space, which is available to anyone (Grillitsch et al., Citation2021).

When analysing regional opportunity spaces, it is essential to consider whose opportunities we are considering. Paasi (Citation2010, p. 2300) notes that we should not ‘see a region as a unit capable of acting (“competing”, “learning”, etc)’ – that is, as a subject of the action or as a given unit. The status and agency of a region as a collective actor is not innate or pre-given (Lagendijk, Citation2007). In practice, regions are ever-changing constellations of economic, social and ecological elements. While it would be easy to think of a regional opportunity space as the sum of regional actors’ opportunity spaces, it can be more than that. As Grillitsch et al. (Citation2021) pointed out, new activities emerge when individual actors’ opportunities overlap and interconnect or when various industries find one another through networks of regional specialization.

2.2. Perceived nature of opportunity space

A region-specific opportunity space involves shared institutional practices or ways of thinking; existing as individual cognitive models and affecting and being affected by collectively perceived opportunity spaces. Crucially, the opportunity space is not only a matter of regional preconditions but also depends on individual agents’ or groups’ perceptions of potential opportunities and their ability to exploit those opportunities (Laasonen & Kolehmainen, Citation2017). Therefore, opportunity spaces may also be agent-specific. Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) described how individual agents differ in terms of capabilities and opportunity perceptions. For example, agents’ capabilities may vary because of their internal skill bases and network positions because they construct their perceived opportunity space through ongoing interactions with others, leading to the formation of a collectively perceived regional opportunity space. Perceived opportunity spaces are closely linked to regional imaginaries that reflect actors’ understandings of the future and provide a context and direction for their work.

The core idea of the concept of the regional imaginary, as Miörner (Citation2022, p. 4) puts it, is that ‘fundamental perceptions, conventions, mental representations and world views exist not only within regional industrial paths but, through discourses and institutional rationalities, are ingrained at a very fundamental level of the regional innovation systems’. Miörner (Citation2022) further argues that well-established imaginaries shape regional opportunity spaces, empowering or restraining actors in taking advantage of emerging opportunities. Regional imaginaries are constructed based on and framed by combinations of actors’ experiences and expectations (Steen, Citation2016). Steen (Citation2016) shows how expectations of changing markets, technology, demand, and customer needs influence regional actors’ strategies and, thus, play a significant role in regional development, in other words, in the construction of regional imaginaries. For their part, Gong and Hassink (Citation2019) argue that cognitive institutions are an essential factor in multi-scalar coevolution and, thus, also in continuously evolving regional imaginaries and the individual and collective expectations that undergird them. For these reasons, we are interested in socially constructed perceived opportunity spaces, drawing on subjective expectations and interpretations of available and potentially emerging opportunities.

Krueger and Day (Citation2010) identify several individual cognitive processes, which in turn shape the processes of recognizing, creating and using opportunities. While imaginaries and expectations define what actors see, these same actors require creativity to act on their perceptions and the intention to pursue opportunities based on these opportunities’ perceived feasibility and desirability. Persistent goal-oriented behaviour is driven by beliefs and attitudes, especially those regarding self-efficacy, building deep-knowledge structures, and learning to interpret and combine this knowledge. Contextual and situational factors, such as the entrepreneurial environment, also affect individual perceptions and behaviours. In other words, the emergence of regional perceived opportunity spaces, which are built on regional imaginaries and collective expectations, is an evolutionary process of collective belief formation and knowledge justification (Sotarauta, Citation2015), preserving the past while also challenging old structures and seeking to break with history.

Indeed, as Rodríguez-Pose (Citation1999) maintains, social structures precondition the regional innovation capacity and, thus, also how actors perceive opportunities or not, making some courses of action easier than others (Morgan, Citation2004). To unify all this, we use Rodríguez-Pose’s (Citation1999) powerful metaphor of a ‘social filter’ to describe the combination of social conditions and socially hegemonic ways of perceiving opportunities in a region (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation1999; Rodríguez-Pose & Crescenzi, Citation2008; Sotarauta, Citation2015). For us, social filters are complex social constructions built on differences in and similarities of the collective and individual expectations prevailing in a region, combining actors’ goals, values, and regional imaginaries. Social filters are often overlapping and potentially conflicting.

2.3. Telescope and projector

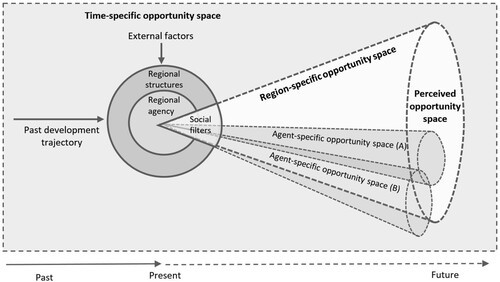

The complex relationships among concepts related to the opportunity space are summarized in . It illustrates the perceived opportunity space in terms of two metaphors: the telescope and the projector. First, the past development path plays an essential role in shaping the regional agency embedded in regional structures. Because external forces, such as strategic intentions at various levels (e.g., changes in regulations and support system) and emergent developments (e.g., new technologies), shape regional conditions, the surrounding time-specific global opportunity space is in a constant state of flux. Second, regional agents view the world of opportunities through a ‘telescope’ in the sense that each agent has their own individual social filters. Regional structures and shared collective beliefs also frame their observations but do not determine them. The telescope may be broad or narrow in scope, magnifying or downsizing items; filters may exclude some opportunities while emphasizing others; the focal point may be in the near future or far away and the telescope may be directed to distant or close locations.

However, the telescope metaphor is only half the story. Future opportunities are not just seen and discovered but also the result of active efforts and creations, as in the case of a ‘projector’. There is a two-way relationship between an opportunity space and agency; actors project imagined opportunities onto the canvas of the future, and through their actions, these opportunities are tested, adjusted, and realized. The twofold interpretation of opportunity space embodies the realist evolutionary perspective that Alvarez et al. (Citation2010) describe. Regional opportunity spaces are shaped by the opportunity spaces of individual agents, but they are more than the sum of those agents’ opportunity spaces. A regional opportunity space can be described as a common denominator or power vector of its components because agents’ opportunity spaces may reach beyond the regional opportunity space and stretch it over time.

2.4. Dimensions of social filters

Future expectations and regional imaginaries do not emerge from thin air. Instead, they are filtered through complex socio-economic–political discourses on regional development theories and frameworks, debates about policies and various regional development strategies, observed regional development patterns in a country or a specific place and the success of dominant industries or emerging economic trends (e.g., Clark et al., Citation2000; Hilding-Rydevik et al., Citation2011). We assume that the extensive knowledge on regional economic growth is reflected in filtering processes and, thus, also in the social construction of regional imaginaries and future expectations. Therefore, we identify seven generic dimensions of social filters for the empirical analysis. We do not scrutinize the dimensions per se but, rather, use them to highlight the differences and similarities between case regions, and thus, they assist us in identifying how perceived opportunity spaces are shaped. Because these dimensions are well known in regional development, they are only briefly introduced below.

The assumptions guiding actors’ views on growth logic shape the ways opportunities are searched for and realized. The central axis is the one between exogenous and endogenous economic growth. In exogenous growth theory, the underlying assumption is that economic growth and prosperity are influenced by external, independent factors rather than being generated internally (endogenous growth, with applications in economic geography; e.g., Clark et al., Citation2000). The nature and scope of specialization versus variety is another central dimension of regional development and growth. We do not engage in the lively debate on specialization or diversification by specialization (Foray, Citation2014) or related and unrelated variety (Frenken et al., Citation2007) but, rather, define regional specialization as a process of a region concentrating more on and possessing expertise in particular industries or fields of knowledge. Variety refers to diversified industrial structures and skill-bases, a number or range of things that are somehow distinct, and thus, what we see as wide strategic thinking is a question of searching ways to increase variety or broaden specialization (e.g., Boschma & Frenken, Citation2011; Glaeser et al., Citation1992; Malmberg & Maskell, Citation1997). Spatial scale refers to whether opportunities are sought primarily from local and regional networks or externally to a region, nationally or internationally.

Regional development is about change, and hence, collective assumptions related to the time horizon are central in filtering processes. The time horizon is a projected temporal range in the future describing the degree of the forward-looking orientation in the construction of and search for opportunities. Are they believed to be occurring over a long or short period? The time horizon is closely related to the projected and aspirational scale of progress, ranging from gradual transformation (incremental change) to abrupt change, leading to discontinuities (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). Assumptions about the time horizon and scale of progress are then closely linked to the mode of action, which is either proactive or reactive, with the former referring to actors constructing or controlling situations and the latter referring to actors responding to situations (Oxford English Dictionary; Crant, Citation2000). Finally, we place the opportunity type within the well-known typology of exploration and exploitation introduced by March (Citation1991). To quote March (Citation1991, p. 71), ‘Exploration includes things captured by terms such as search, variation, risk-taking, experimentation, play, flexibility, discovery, innovation. Exploitation includes such things as refinement, choice, production, efficiency, selection, implementation, execution.’ The social filters and their various dimensions are summarized in .

Table 1. Dimensions of social filters.

The theoretical contribution of this paper is to scrutinize the formation and search of regional futures as an interplay of agency and structure that have often been studied apart from each other. Our conceptual framework links these two by using the concept of opportunity space that gradually evolves and which is affected by social filters.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our analysis of opportunity spaces is based on extensive data collected during the Swedish–Finnish–Norwegian research project ‘Regional Growth Against All the Odds’ (ReGrow), which explored regional economic growth in unlikely conditions. This article draws on data from six case regions: Jakobstad and Eastern Lapland in Finland; the Gislaved and Emmaboda labour market regions in Sweden, and the Ulsteinvik and Mo i Rana labour market regions in Norway (). The regions were selected based on an extensive quantitative analysis aimed at identifying outliers (positive or negative) in terms of employment growth in the three above-mentioned countries. All labour-market regions (Sweden and Norway) or subregions (Finland) were analysed for the period from the 1990s to 2015. Under- and overperforming regions, that is, regions that perform significantly better or worse in terms of employment growth than what could be expected given their structural conditions, were identified. Structural conditions included variables representing, for example, industry structure, human capital, and population (Grillitsch et al., Citation2021). Twelve case regions were selected from the list of outliers, four from each country, to represent a variety of regions, for example, various growth outcomes and regional varying preconditions, such as peripherality and specialization. A qualitative study was conducted in each case region in the period 2018–20, producing comprehensive case study reports. The aim of the case studies was to explain regional under- versus overperformance. The analytical focus was on agency, which was based on the assertion that performance residuals that cannot be explained by structural conditions may be explained by local agency.

Table 2. Case study regions: basic information.

An identical methodology was followed in each case (e.g., common interview guides and interview protocols). The first stage of each case study was to map the regional economic landscape and produce a first draft of the regional event history based on an analysis of policy documents, media archives and other relevant material. Based on this, a total of 207 semi-structured interviews were conducted in the 12 regions. This paper draws on 90 of these, which are related to the six case regions analysed here. The respondents include individuals from locally present firms, local and regional government, development organizations (e.g., science parks and cluster initiatives) and higher education institutions. The aim was to identify and understand the key events in the regional development trajectory, the actions and actors behind them and the obstacles and enablers related to agency in these actions. The interviews covered individuals involved in key events since the 1990s but with a stronger emphasis on the 2000s and 2010s.

A comparative analysis of the dimensions of social filters was conducted to identify the key factors framing the process of perceiving regional opportunity spaces. To begin, social filters were categorized in a data-driven manner based on two example cases (Jakobstad and Eastern Lapland) in which these filters were apparent and diametrically opposite. The categories did not yet have labels arising from the literature (Kurikka et al., Citation2020). Next, the categories were further developed and anchored in theory-based concepts and categories and labelled according to established scientific terminology (e.g., endogenous and exogenous), but the typology is not based on a theoretical framework developed ex ante.

To further understand and corroborate the applicability of these categories in other regional contexts, four additional cases, two from each country, were chosen. These six cases represent regions in which we identified changes in opportunity spaces, providing rich data about the dynamics and characteristics of the phenomenon. Each social filter dimension was coded by a group of researchers responsible for the case study in question. Coding was performed using three alternatives. The classes described the opposite ends of the scale; for example, is it common to seek incremental solutions versus large scale abrupt solutions in the region? The middle alternative indicated that both types of social filters are present and there is no clear and consistent emphasis on either one.

The collection and analysis of data thus followed an abductive logic (Dubois & Gadde Citation2002, Citation2014) in which empirical phenomena (agency in the under- and overperformance of regions) represent the starting point of the analysis. However, we iterate between theory and data, rather than inductively, analysing the empirical matter without confrontation with theory, or deductively, basing the analysis on a predefined theoretical framework to be tested. The abductive approach allowed us to draw on existing theory as inspiration to identify empirical patterns, which helped us to interpret the cases. Thus, we alternated between theory and empirics, both being reinterpreted throughout the research process (Alvesson & Sköldberg, Citation1994). The preliminary framework, in terms of elements and dimensions of local agency, opportunity space and social filters, represents ‘a rough working frame’ (Miles, Citation1979, p. 218, cited in Dubois & Gadde, Citation2014), which is refined throughout the research process via the critical evaluation of emerging constructs (Dubois & Gadde, Citation2014).

In addition, we drew on extensive case study reports and one-page narrative summaries detailing the characteristics and development of opportunity spaces in each region. The data provided empirical instances of the concepts of agent-, region- and time-specific opportunity spaces. The material also served to confirm the processual nature of opportunity spaces and their links to actual regional development.

4. THE ELEMENTS OF THE OPPORTUNITY SPACE

4.1. Matching agent-, region- and time-specific opportunity spaces in Ulsteinvik

The Ulsteinvik case serves as a useful example for illustrating opportunity space types and relationships (time-, region- and agent-specific opportunity spaces). This labour market region in West Norway has a strong tradition of shipbuilding and fisheries and has become a global hub for the maritime industry. It is known as a strong cluster encompassing all parts of the maritime value chain (shipbuilders, ship owners and suppliers). The local maritime industry has increasingly focused on the oil and gas market, which is highly volatile. Consequently, the region is highly dependent on a global, exogenous, time-specific opportunity space.

In the 1970s, some local ship owners and shipbuilders perceived opportunities in the offshore service vessel industry. They began designing ships based on local experience and expertise, that is, they discovered their agent-specific opportunity space. The success of these vessels on the US market was an important signal to other regional actors that they could compete in global markets, and innovative entrepreneurship became the norm among local maritime firms. ‘They showed the local people that it is possible for smaller regions to grow and compete on global markets,’ an actor within the regional support system and previous shipbuilder explained. In short, the new opportunity spaces of a few individual actors spread to other companies and affected the region-specific opportunity space as a whole. Additionally, systematic cluster-building in the maritime industry further strengthened regional competence and sectoral development, resulting to the emergence of a full value chain.

In the early 2000s, the regional maritime industry underwent a crisis because of international turbulences that led to cutbacks and layoffs. However, despite great uncertainty in global markets, local shipbuilders developed new designs in the early 2000s. Some local shipowners identified new opportunities arising from the rapid industrialization of China (the so-called ‘China effect’ 2004–13) and commissioned new ships from local shipyards. These actions encouraged other regional actors to do the same, facilitating rapid growth in the local maritime industry from 2004 onwards. ‘In 2004, early 2005, they ordered a couple of offshore vessels – this began rumours, and other actors also started to order new boats (actors within the regional support system).’ These events illustrate the crucial importance of matching region- and agent-specific opportunity spaces with a time-specific situation in order to survive and generate growth, often depending on pioneers to explore new possibilities and take financial risks. ‘Shipowners influence each other; one of them does something new, and the others will follow,’ a local mayor explained. During the international oil crisis of 2014, demand for offshore oil and gas service vessels dropped dramatically, again exposing the region’s sensitivity to global trends. The regional support structure played a key role in exploring new technologies and markets typically linked to the ‘green growth’ agenda (e.g., cruise ships, battery ferries, offshore wind and fish farming), and these initiatives contributed to a widening of the regional opportunity space.

4.2. How social filters shape the perceived opportunity space: Jakobstad, Gislaved and Eastern Lapland

The three case regions of Jakobstad, Gislaved and Eastern Lapland serve to clarify the dimensions of social filters that frame the perception of opportunities. We identified two case regions with very similar profiles: Gislaved in Sweden and Jakobstad in Finland, along with a third region with an almost opposite profile, Eastern Lapland in Finland. The sharp contrast between these regions helped to identify the dimensions and extremes of social filters.

Both Gislaved and Jakobstad have large small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) sectors and long traditions of successful industrial manufacturing. Despite some economic fluctuations, recovery after recessions has been relatively quick, and unemployment levels have remained well below the national average. These similarities are not only structural and historical but also relate to strong social filters. Because their growth logic is highly entrepreneurial, growth is largely sought through endogenous activities. For example, Gislaved (that is, the Gnosjö region) is famous for its entrepreneurial spirit, or ‘Gnosjöandan’. Additionally, SMEs in these regions emphasize incremental improvement, a continuous development logic and exports. However, their opportunity space is, to some extent, confined to existing industries and technologies. Family ownership, a deep commitment to the region and community- and local trust-based networks are also common, providing long-term strategic perspective and social filters that focus on the local spatial scale regarding the supplier base and value chains. As one company interviewee stated about family-owned firms in the Jakobstad region, ‘their quartile is 25 years’. Because no two regions are ever entirely similar, there are also some slight differences. Gislaved is somewhat more specialized, and enterprises focus on supplying their standard customers, which are mostly multinational companies (MNCs), making the region more sensitive to international competition and periods of global recession. Gislaved thus has some elements of exogenous growth logic; however, the local culture and local value chains remain dominant. In Jakobstad, the variety of business structures is considered enriching, and a diverse range of manufacturing and active sales is seen as a source of resilience.

An opposite example is provided by Eastern Lapland in Finland. This remote region once had a pulp industry and electronics manufacturing. The closing of the Salcomp electronics factory in 2004 and the pulp mill of Stora Enso in 2008 caused increasing unemployment and outmigration. State support and the public sector have been important drivers of creating and sustaining new jobs in the region, where the sustaining logic has traditionally involved either small-scale natural livelihoods or employment in large industrial corporations and ski resorts owned by investors from elsewhere. Entrepreneurship is not often considered a viable choice, and the growth logic can be described as exogenous. Local responses to plant closures have been reactive and resistance focused. Lately, however, there has been a new local effort to establish a large modern biorefinery funded by foreign and domestic extra-regional investors. As one regional developer stated:

Entrepreneurial spirit is missing, and people are used to having big employers. Now, they are waiting for the Bioref [the new bio refinery] to be established – somehow, the atmosphere here is kind of oppressive because of the state dependency and the dependency on big projects. Kind of waiting.

The collectively perceived regional opportunities in Eastern Lapland often have a very long timescale and require radical and abrupt development actions. Over the decades, proposed initiatives have included a large mine, a very large artificial lake for hydropower production and a new railroad. None of these, however, has come to fruition. In some cases, this is because local actors are still waiting for the final decisions, which are made by stakeholders outside the region. It also seems that these perceived opportunities focus mainly on natural resources and social filters have restricted the identification of some opportunities or the capacity to exploit them. On the other hand, the crisis prompted increasingly active local agency, and some individual actors are attempting to break old social filters – for example, by showing that locals can drive initiatives and that the state is not the only potential partner.

4.3. Emergence and change in perceived opportunity spaces – the cases of Mo i Rana and Emmaboda

The Mo i Rana labour market region in North Norway is traditionally known for its large-scale manufacturing and mining industries, which date to the early 1900s. For a long time, the industry was dominated by the state-owned Norsk Jernverk (the Norwegian Ironworks), which was shut down, split into different units and sold to private actors in 1988 following a long period of economic difficulties. This was followed by a huge national restructuring package, which was designed to reduce this overdependency on the process industry by exploring new opportunities (e.g., Grønlund, Citation1994; Jakobsen & Høvig, Citation2014). Since the early 2000s, the regional opportunity space has undergone two significant changes.

First, the rapid increase in demand for steel and minerals on global markets played a key role in the growth of the process industry after 2004. Also, MNCs began to enter the region in 2003 to exploit perceived opportunities in global markets. The favourable industrial environment in Mo i Rana was very attractive for such purposes. ‘What attracted them to enter was the strong infrastructure, relevant competencies, and industrial culture; that is, the local people are willing to work very much’ (an actor within the local support structure). Unlike previous owners who had taken over the different units of Norsk Jernverk, the arriving MNCs began to invest heavily in facilities and a more environmentally friendly process for technologies and products, demand for which has increased greatly in global markets. This contributed to path upgrading, creating new jobs, and facilitating the growth of the local supplier sector in Mo Industry Park (MIP).

Second, the development of national public services played an important role in diversifying the regional economy. Although part of a national initiative following the shutdown of Norsk Jernverk, the local leaders of these organizations perceived great opportunities afforded by the digitalization of national services, which had previously been mostly analogous and involved regular office hours. Starting out as small units, these began to grow, gradually resulting from a proactive leadership and location-specific competencies. This was supported by the local industrial shift culture, that is, employees were willing to work and offer services outside the traditional nine to five office hours, and there was a relevant local competence base because of past activities. Specifically, Norsk Jernverk’s ‘crown jewel’ was once their large digital department, which was among the first of its kind in Norway. The proactive efforts of these organizations have continued to develop new types of service at the national level and successfully maintained employment growth. This has diversified the regional economy and widened the perceived opportunity space, including further digitalization and automation.

The regional support structure has grown significantly since the early 2000s and played an important role in the development of the Mo i Rana region by successfully mobilizing regional and national resources to create new paths for the local economy. Actors within the support structure began to perceive great opportunities for increased cross-sectoral networking and collaboration that were not apparent in the early 2000s. ‘We connected people – this was the most important thing that we did’ (previous key actor within the local support structure). Despite unfavourable pre-structural conditions characterized by a single dominant industry and a weak collaboration culture, a range of proactive initiatives have changed the local mindset regarding what is possible and how the region can move beyond the way things have always been done. ‘We focus on the gap between [the] industry way of thinking and [the] research way of thinking,’ an actor within the local support structure explained. As a result, regional actors are now much more networked and open to both cross-sectoral and industry–university collaborations (see also Karijord, Citation2016; Nilsen & Lauvås, Citation2018). The Mo i Rana case illustrates that even a peripheral and traditionally resource-based region that was very dependent on a single dominant firm or industry can explore and exploit new kinds of opportunities in order to create new regional development paths. Change agency and perceived opportunity space have played a key role in this process.

By way of contrast, the Swedish region of Emmaboda is an example of a region that has struggled to widen its perceived opportunity space after the loss of its traditional glass industry over the last 30 years. The region currently relies heavily on one foreign-owned MNC in industrial manufacturing. Even though there is an obvious risk that the multinational will exit the region in the future, stakeholders are unable or unwilling to envision new futures. For example, municipal actors believe that the further growth of the MNC, as their largest employer, is the most promising future opportunity. At the same time, they acknowledge that this is beyond their sphere of influence. More disconcerting still, they admit to remaining unprepared for a decision to downsize or move the plant, despite an attempt to move production to China a few years ago. One public policymaker explained this, after some hesitation: ‘we don’t think about it, because it is too difficult to think about, and there is anyway nothing we can do about it’. This demonstrates that, even a crisis or the threat of one is not always sufficient to trigger a change in the perceived opportunity space without active change agency among enterprises, individuals and organizations, allowing them to perceive and avail themselves of such opportunities.

5. DISCUSSION OF THE MAIN OBSERVATIONS

To achieve long-term growth, a region must constantly seek new opportunities; without opportunities, there is no development. Our argument is that a region’s possibilities for development depend on perceived opportunity spaces, reaching beyond time-specific windows of opportunity or individual actors’ search for opportunities. By focusing on perceived opportunity spaces, we follow Grillitsch and Sotarauta’s (Citation2020) suggestion that the concept of opportunity space would provide analytical leverage and thus shed light on the interaction between structures and agency. Moreover, the future is implicitly present in regional development analysis and practice; still, it is often poorly, if at all, conceptualized in regional development studies. Opportunity space provides a conceptual link between (1) structure and agency and (2) the past and the future. We find this important for advancing our theoretical understanding of regional development dynamics.

We show that perceived opportunity spaces play a central role in the regional economic development puzzle and that the concept can be applied across empirical cases. Importantly, regions differ in how they frame opportunity spaces. We also show how perceived opportunity spaces co-evolve with actual regional development, in other words, how regional preconditions shape the process of perception and the social filters guiding them, as well as how actors draw on their perceptions to find ways to improve structures. Regional actors determine how opportunities are perceived and used, as well as how structural obstacles are assumed to be overcome.

We argued that social filters frame perceived opportunities in terms of where, when and how actors assume it is possible to enhance economic growth. While a single study cannot capture all possible social filters or their dimensions that shape the ways opportunities are perceived, we reveal the similarities and differences between the social filters of six peripheral Nordic regions (). As our case studies highlight, regions differ in terms of perceived region-specific opportunity spaces, which may be shared, wide or narrow, restricting or encouraging individual actors. Some regions may have weaker region-specific opportunity spaces, making regional development more likely to occur through the development of respective agents than through joint efforts and initiatives.

Table 3. Dimensions of social filters and the way they frame opportunity spaces in case regions.

presents a summary of our empirical observations. It illustrates how the social filters drawing on mainstream regional development theories guide thinking in regions. In some regions, social filters were more industry-specific than region-specific, for instance, in Mo i Rana and Ulsteinvik. In some other regions, the search for future opportunities was clearly dominated by a more coherent and collective social filter, with Jakobstad serving as a prime example. Of course, as stressed throughout the paper, the relationship between the perceiving of opportunities and preconditions (structures) is a reciprocal one. Therefore, we are not able to conclude whether Jakobstad and Gislaved, for example, have export-oriented SME sectors because the dominant social filter is proactive and internationally oriented. Alternatively, are the social filters proactive and internationally oriented because there is a vibrant and international SME sector?

Our results demonstrate how social filters can differ considerably between regions. Only the opportunity type was heavily focused on exploitation instead of exploration. This was to be expected in non-core regions where the highly research and development (R&D)-intensive activities are less common.

What we can say is that by focusing specifically on opportunity spaces, it is possible to open up a novel view on well-known issues. Conversely, it is possible to shed light on opportunity spaces using grand theories (like exogenous versus endogenous growth or specialization versus variety) as dimensions of social filters. In sum, we can say that, by focusing specifically on opportunity spaces, it is possible to identify region-, agent- and time-specific patterns of opportunity search, construction and exploitation.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Regional development studies ought to reach beyond formal policies and industrial structures to identify the dynamics of the reciprocal interaction between actors and structures, on the one hand, and the future and path dependencies, on the other. We should not ignore the opportunity spaces and assume that opportunities are more or less the same, while only structures or agency differ. Therefore, we contribute to the literature on the relationship between human agency and structures by applying the concept of the opportunity space. In this way, we linked agency and a future orientation with the literature on evolutionary approaches, which has been criticized for neglecting the role of agency and focusing too heavily on past developments and structural preconditions (e.g., Hassink et al., Citation2014; Pike et al., Citation2009; Steen, Citation2016). Moreover, we develop a conceptual framework to investigate how actors search for and construct opportunities in regions by linking opportunity spaces to the mainstream targets of attention and using them as dimensions of social filters. This differs from and complements many other studies using the same concepts to explain regional economic growth quantitatively (e.g., Capello & Nijkamp, Citation2009) or shed light on policymaking (e.g., McCann & Ortega-Argilés, Citation2015). Instead of operationalizing grand theories quantitatively one by one, we approached them holistically, viewing opportunity spaces through them. Well-known theories and concepts were used to qualitatively understand how key actors search for and perceive opportunities and what shapes expectations in regions, thus answering our research questions.

More specifically, we add to the literature on locational opportunities, regional imaginaries, and regional expectations by identifying how opportunities are perceived and regional expectations are shaped. By showing how varying social filters shape regional imaginaries, we join earlier studies that call for a more nuanced understanding of actors’ cognitive patterns concerning regional development and related policies (e.g., Asheim, Citation2012; Flanagan et al., Citation2011). This may prove crucial because rationality often follows effective knowledge filtering and belief formation, and not vice versa (e.g., Flyvbjerg, Citation1998).

From this point of departure, the need for further investigation is twofold. Firstly, we must learn more about how futures-oriented thinking in regions is influenced, by whom and how the capabilities of purposive actors are shaped by social filters, instead of simply considering formal positions or policies (Dahl, Citation1961/Citation2005). Understanding how opportunities are perceived at a more in-depth level, as well as the development strategies filtered through a shower of external and internal influences, might allow us to better explain the variance in regional development and connect the evolutionary to the institutional. Secondly, the identified generic dimensions of social filters with this deepened understanding could be exposed to vast and rigorous quantitative scrutiny, to study to what extent the generic dimensions of social filters are shared within and among regions and how are they related to the actual economic development paths and prospects of the regions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are thankful for both the cooperation with the Regional Growth Against All Odds project team and valuable comments from the anonymous reviewers.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Alvarez, S. A., Barney, J. B., & Young, S. L. (2010). Debates in entrepreneurship: Opportunity formation and implications for the field of entrepreneurship. In Z. J. Acs & D. B. Audretsch (Eds.) Handbook of entrepreneurship research (pp. 23–45). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1191-9_2

- Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg, K. (1994). Tolkning og reflektion. Vetenskapsfilosofi och kvalitativ metod. Studentlitteratur.

- Amin, A., & Thrift, N. (2000). What kind of economic theory for what kind of economic geography. Antipode, 32(1), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00117

- Asheim, B. (2012). The changing role of learning regions in the globalizing knowledge economy: A theoretical re-examination. Regional Studies, 46(8), 993–1004. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.607805

- Battilana, J., Leca, B., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 65–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903053598

- Boschma, R. (1997). New industries and windows of locational opportunity: A long-term analysis of Belgium. Erdkunde, 51(1), 12–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25646864. https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.1997.01.02

- Boschma, R. & Frenken, K. (2011). Technological relatedness, related variety and economic geography. In P. Cooke, B. Asheim, R. Boschma, R. Martin, D. Schwatz, & F. Tödtling (Eds.), Handbook of regional innovation and growth. Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9780857931504.00028

- Boschma, R., & Van der Knaap, G. A. (1999). New high-tech industries and windows of locational opportunity: The role of labour markets and knowledge institutions during the industrial era. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 81(2), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.1999.00050.x

- Boschma, R., & Wenting, R. (2007). The spatial evolution of the British automobile industry: Does location matter? Industrial and Corporate Change, 16(2), 213–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtm004

- Capello, R., & Nijkamp, P. (2009). Handbook of regional growth and development theories. Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781848445987

- Clark, G. L., Feldman, M. P., & Gertler, M. S. (2000). The Oxford handbook of economic geography. Oxford University Press.

- Cooke, P., & Eriksson, A. (2012). Resilience, innovative ‘white spaces’ and cluster-platforms as a response to globalisation shocks. In P. Cooke, M. D. Parrilli, & J. L. Curbelo (Eds.), Innovation, global change and territorial resilience (pp. 43–70). Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9780857935755.00009

- Crant, J. M. (2000). Proactive behavior in organizations. Journal of Management, 26(3), 435–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600304

- Dahl, R. A. (1961/2005). Who governs? Democracy and power in an American city. Yale University Press.

- Dawley, S. (2014). Creating new paths? Offshore wind, policy activism, and peripheral region development. Economic Geography, 90(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecge.12028

- Dubois, A., & Gadde, L. E. (2002). Systematic combining: An abductive approach to case research. Journal of Business Research, 55(7), 553–560.

- Dubois, A., & Gadde, L. E. (2014). Systematic combining – A decade later. Journal of Business Research, 67(6), 1277–1284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.03.036

- Flanagan, K., Uyarra, E., & Laranja, M. (2011). The ‘policy mix’ for innovation: Rethinking innovation policy in a multi-level, multi-actor context. Research Policy, 40(5), 702–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.02.005

- Flyvbjerg, B. (1998). Rationality and power: Democracy in practice. University of Chicago Press.

- Foray, D. (2014). From smart specialisation to smart specialisation policy. European Journal of Innovation Management, 17(4), 492–507. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-09-2014-0096

- Frenken, K., van Oort, F., & Verburg, T. (2007). Related variety, unrelated variety and regional economic growth. Regional Studies, 41(5), 685–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400601120296

- Gertler, M. S. (2010). Rules of the game: The place of institutions in regional economic change. Regional Studies, 44(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400903389979

- Giddens, A. (1979). Central problems in social theory. Macmillan.

- Glaeser, E., Kallal, H., Scheinkman, J., & Shleifer, A. (1992). Growth in cities. Journal of Political Economy, 100(6), 1126–1152. https://doi.org/10.1086/261856

- Gong, H., & Hassink, R. (2019). Co-evolution in contemporary economic geography: Towards a theoretical framework. Regional Studies, 53(9), 1344–1355. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1494824

- Grabher, G. (1993). The weakness of strong ties: The lock-in of regional development in the Ruhr area. In G. Grabher (Ed.), The embedded firm: On the socioeconomics of industrial networks (pp. 255–277). Routledge.

- Grillitsch, M., Martynovich, M., Fitjar, R. D., & Haus-Reve, S. (2021). The black box of regional growth. Journal of Geographical Systems, 23(3), 425–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10109-020-00341-3

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Grønlund, I. L. (1994). Restructuring one-company towns: The Norwegian context and the case of Mo i Rana. European Urban and Regional Studies, 1(2), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977649400100205

- Hassink, R., Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2019). Towards a comprehensive understanding of new regional industrial path development. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1636–1645. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Hassink, R., Klerding, C., & Marques, P. (2014). Advancing evolutionary economic geography by engaged pluralism. Regional Studies, 48(7), 1295–1307. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.889815

- Hilding-Rydevik, T., Håkansson, M., & Isaksson, K. (2011). The Swedish discourse on sustainable regional development: Consolidating the post-political condition. International Planning Studies, 16(2), 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2011.561062

- Jakobsen, S.-E., & Høvig, Ø. S. (2014). Hegemonic ideas and local adaptations: Development of the Norwegian regional restructuring instrument. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 68(2), 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2014.894562

- Jessop, B. (2001). Institutional re(turns) and the strategic-relational approach. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 33(7), 1213–1235. https://doi.org/10.1068/a32183

- Johnson, M. W. (2010). Seizing the white space: Business model innovation for growth and renewal. Harvard Business Press.

- Karijord, C. (2016). Skal ruste opp nordnorske bedrifter. High North News. https://www.highnorthnews.com/nb/skal-ruste-opp-nordnorske-bedrifter

- Kingdon, J. W. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Little, Brown.

- Krueger, N. F. Jr., & Day, M. (2010). Looking forward, looking backward: From entrepreneurial cognition to neuroentrepreneurship. In Z. J. Acs & D. B. Audretsch (Eds.) Handbook of entrepreneurship research (pp. 321–357). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1191-9_13

- Kurikka, H., Kolehmainen, J., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). Agency and perceived regional opportunity spaces. Conference paper. GeoInno 2020, Stavanger. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339653006_Agency_and_perceived_regional_opportunity_spaces

- Laasonen, V., & Kolehmainen, J. (2017). Capabilities in knowledge-based regional development – Towards a dynamic framework. European Planning Studies, 25(10), 1673–1692. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1337727

- Lagendijk, A. (2007). The accident of the region: A strategic relational perspective on the construction of the region’s significance. Regional Studies, 41(9), 1193–1208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701675579

- Malmberg, A., & Maskell, P. (1997). Towards an explanation of regional specialization and industry agglomeration. European Planning Studies, 5(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654319708720382

- March, J. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.71

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- McCann, P., & Ortega-Argilés, R. (2015). Smart specialisation, regional growth and applications to EU cohesion policy. Regional Studies, 49(8), 1291–1302. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.799769

- Miles, M. B. (1979). Qualitative data as an attractive nuisance: The problem of analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(4), 590–601. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392365

- Miörner, J. (2022). Contextualizing agency in new path development: How system selectivity shapes regional reconfiguration capacity. Regional Studies, 56, 592–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1854713

- Morgan, K. (2004). The exaggerated death of geography: Learning, proximity and territorial innovation systems. Journal of Economic Geography, 4(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/4.1.3

- Nilsen, T., & Lauvås, T. A. (2018). The role of proximity dimensions in facilitating university–industry collaboration in peripheral regions: Insights from a comparative case study in northern Norway. Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 9, 312–331. https://doi.org/10.23865/arctic.v9.1378

- Paasi, A. (2010). Regions are social constructs, but who or what ‘constructs’ them? Agency in question. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(10), 2296–2301. https://doi.org/10.1068/a42232

- Pike, A., Birch, K., Cumbers, A., MacKinnon, D., & McMaster, R. (2009). A geographical political economy of evolution in economic geography. Economic Geography, 85(2), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01021.x

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (1999). Innovation prone and innovation averse societies: Economic performance in Europe. Growth and Change, 30(1), 75–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/0017-4815.00105

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013). Do institutions matter for regional development? Regional Studies, 47(7), 1034–1047. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.748978

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Crescenzi, R. (2008). Research and development, spillovers, innovation systems, and the genesis of regional growth in Europe. Regional Studies, 42(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701654186

- Scott, A. J., & Storper, M. (1987). High technology industry and regional development: A theoretical critique and reconstruction. International Social Science Journal, 112, 215–232.

- Sotarauta, M. (2015). Leadership and the city: Power, strategy and networks in the making of knowledge cities. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315753256

- Sotarauta, M. (2017). An actor-centric bottom-up view of institutions: Combinatorial knowledge dynamics through the eyes of institutional entrepreneurs and institutional navigators. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(4), 584–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X16664906

- Steen, M. (2016). Reconsidering path creation in economic geography: Aspects of agency, temporality and methods. European Planning Studies, 24(9), 1605–1622. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1204427

- Streeck, W., & Thelen, K. (2005). Introduction: Institutional change in advanced political economies. In W. Streeck, & K. Thelen (Eds.), Beyond continuity: Institutional change in advanced political economies (pp. 3–39). Oxford University Press.

- Storper, M., & Walker, R. (1989). The capitalist imperative: Territory, technology and industrial growth. Basil Blackwell.

- Suarez, F. F., Grodal, S., & Gotsopoulos, A. (2015). Perfect timing? Dominant category, dominant design, and the window of opportunity for firm entry. Strategic Management Journal, 36(3), 437–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2225

- Tödtling, F., & Trippl, M. (2013). Transformation of regional innovation systems: From old legacies to new development paths. In P. Cooke (Ed.), Re-framing regional development: Evolution, innovation and transition (pp. 297–317). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203097489