ABSTRACT

This paper is focused on the emergence of new institutional structures and geographies within the context of complex processes of state rescaling characterized by ‘hollowing out’ and ‘filling in’. It explores the regionalization of transport policy within Wales post-devolution and examines the potential of Haughton et al.’s concepts of ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ spaces as useful tools in furthering our understanding of state rescaling. The paper suggests that the case of transport policy in Wales post-devolution provides a useful example of the evolution of ‘soft spaces’ through processes of hardening and softening, and that ‘stickiness’ of regional spatial imaginaries.

JEL:

1. INTRODUCTION

The introduction of devolution by the Labour government in 1999 has been characterized as leading to a fundamental restructuring of territorial governance arrangements within the UK. These processes have been characterized as reflecting a wider global trend which has led to the redistribution of responsibilities between different levels of governance (Rodríguez-Pose & Gill, Citation2003). Before these reforms, the UK was traditionally portrayed as a highly centralized unitary state, although this characterization was challenged as an oversimplification. The introduction of devolution reinvigorated debates in political science regarding how the UK could be characterized as a ‘unitary state’, ‘union state’, ‘quasi-federal state’ or ‘state of unions’ (Bradbury, Citation2021; Mitchell, Citation2009). The piecemeal model of devolution introduced by Labour across the constituent parts of the UK reflected the historically asymmetrical approach to territorial governance (Jeffery, Citation2009). For example, in 1999, Scotland and Northern Ireland were granted primary legislative powers in a range of areas, whereas Wales received secondary legislative powers. Furthermore, the original model of devolution adopted in Wales was based on a conferred powers model whereby the competences of the newly created National Assembly for Wales were specifically laid out in the legislation. This contrasted with the reserved powers model introduced in Scotland and Northern Ireland where all areas that were not explicitly reserved to Westminster were within the general competence of the Scottish Parliament and Northern Ireland Assembly. Since 1999 these devolved ‘settlements’ have continued to evolve, reflecting the then Secretary of State for Wales, Ron Davies’, characterization of devolution as a ‘process not an event’ (Davies, Citation1999). The experience of the first 20 years of devolution in Wales has exemplified this approach, with a shift to full law-making powers following the successful 2011 referendum, the further transfer of some fiscal and borrowing powers, and the shift to a reserved powers model.

The introduction of devolved administrations created a new set of intergovernmental relations between the newly devolved level and pre-existing local government (Himsworth, Citation1998; Laffin et al., Citation2000). Indeed, a recurring area of tension has been the potential for the newly created devolved administrations to engage in ‘regionally orchestrated centralism’ centred on the regional level’s capacity to exercise its scalar power to (dis)empower the local level (Harrison, Citation2008). These tensions have been particularly acute within Wales, where the relative weakness of the original devolved settlement left the Welsh Government dependent on local government for the delivery of its strategic objectives in a wide range of policy fields. This policy development and delivery deficit partly explains why, as Entwistle (Citation2006, p. 234) notes, the notion of partnership was ‘inextricably bound up with the development of the new, devolved institutions of government in Wales’. However, the relationship between the devolved and local levels has not been without tensions, specifically around the recurring theme of local government reorganization, and attempts by the Welsh Government to recreate policy capacity at a regional level (Cole & Stafford, Citation2015). Jones et al. (Citation2005) characterize these latter processes of creating new organizations of governance as reflecting the process of ‘filling in’ the state.

The analyses of ‘hollowing out’ and ‘filling in’ that has evolved over the past 20 years to explore these phenomena has been rooted in the wider literature on sociospatial theory, specifically the strategic–relational approach (SRA) to state theory developed by Jessop (Citation1990, Citation2001, Citation2002). Jones et al. (Citation2005, p. 337) note that three interrelated processes are key to understanding Jessop’s characterization of the ‘hollowing out’ of the national state: ‘the destatisation of the political system’ marked by the shift from government to governance; the internationalization of policy communities and networks; and the denationalization of the state, in which responsibilities are divided across spatial levels. However, Goodwin et al. (Citation2005, p. 424) argue that whilst ‘hollowing out’ provides a useful conceptual metaphor for the delegation of powers away from the national level, due to its ‘spatial myopia’ it ‘makes no explicit claims about the organizational or institutional forms that may result’ due to the concept’s narrow focus on the national level. Therefore, in order to understand the ‘qualitative process of state restructuring’ (Peck, Citation2001), Goodwin et al. (Citation2005) and Jones et al. (Citation2005) put forward the concept of ‘filling in’ to explore the complex and contingent organizational and institutional restructuring of the state at alternative spatial scales. This process of ‘filling in’ is characterized as ‘the sedimentation of new organizations, the reconfiguration of pre-existing organizations, the evolution of new relationships between different organizations and the development of new working cultures’ (Jones et al., Citation2005, p. 357).

The interest in state rescaling has been framed over much of the previous two decades by a fundamental debate regarding relational approaches to analysing and understanding regions within what has been termed the ‘new new regional geography’ (Jones, Citation2022, p. 44). This debate was characterized by Varró and Lagendijk (Citation2013) as being between ‘radical relationalists’ (Allen et al., Citation1998; Allen & Cochrane, Citation2007; Amin et al., Citation2003; Massey, Citation2007) and ‘moderate relationalists’ (Harrison, Citation2010; Hudson, Citation2007; Jones & Macleod, Citation2004; Morgan, Citation2007). On the one hand, the former argued that territorial–scalar approaches should be replaced by a relational approach focused on networks and flows and, on the other, the latter advocated that territorial–scalar approaches should be retained and further developed, alongside this non-territorial, relational approach (Harrison, Citation2013). In the contemporary setting there have been concerted efforts to move beyond this binary division by recognizing the interplay of different factors, for example, Jessop et al.’s (Citation2008) call for a polymorphous framework of socio-spatial relations. Although not its primary focus, this paper is situated within these attempts to move beyond this binary debate and takes as a starting point the assumption that regions are ‘a flexible, malleable and mutable object of analysis’ (Paasi & Metzger, Citation2017, p. 27) that are continuously ‘becoming’ rather than ‘being’. Therefore, the spaces that have emerged through the complex processes of ‘filling in’ identified by Jones et al. (Citation2005) are continuously being made and remade. However, as Brenner (Citation2009) and Harrison (Citation2013) stress, these processes do not occur on a ‘blank slate’ but are shaped and influenced by past or pre-existing arrangements. Similarly, Jones (Citation2022, p. 55) draws on the work of Malabou (Citation2008) on plasticity in characterizing regions ‘not as discrete entities but as multi-dimensional, contingent, and relationally implicated and entwined plastic surfaces’.

Processes of ‘hollowing out’ and ‘filling in’ have been explored across a range of policy areas within the post-devolution context in the UK including economic development (Goodwin et al., Citation2005, Citation2006; Jones et al., Citation2005), transport (Mackinnon et al., Citation2008; Mackinnon & Shaw, Citation2010) and spatial planning (Haughton et al., Citation2010). Mackinnon et al.’s (Citation2008) comparative analysis of transport policy, for example, provided a picture of uneven processes of ‘hollowing out’ and structural and relational forms of ‘filling in’ across different territories within the UK in the first decade of devolution. Significant structural ‘filling in’ was characterized as having taken place in all parts of the UK but most significantly via the establishment of strong executive agencies in London and Scotland through the creation of Transport for London (TfL) and Transport Scotland. However, relational forms of ‘filling in’ were characterized as reflecting more complex processes, for example, the assertion of the newly defined ‘national scale’ in Scotland and Wales encompassed a ‘nationally orchestrated regionalisation of transport governance’ at the expense of existing local and regional arrangements (Mackinnon et al., Citation2008, p. 164). Haughton et al.’s (Citation2010) analysis of ‘hollowing out’ and ‘filling in’ within the context of spatial planning in Ireland and the UK provides interesting parallels with this regionalization of transport governance.

This paper draws on these existing studies and puts forward two core arguments. First, that the concepts of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ spaces offer a valuable framework in furthering our understanding of the emergence of and responses to new geographies of governance within the context of ‘structural’ and ‘relational’ forms of ‘filling in’ (Shaw & Mackinnon, Citation2011). Second, as Harrison et al. (Citation2017, p. 1022) note, the recognition that ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ spaces are not static but can go through processes of ‘softening’ or ‘hardening’, and in some instances ‘be short lived and ultimately disappear’, is integral to understanding processes of institutionalization and what Zimmerbauer et al. (Citation2017) characterized as deinstitutionalization (Allmendinger et al., Citation2014; Metzger & Schmitt, Citation2012; Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2020). The paper examines these arguments through a critical analysis of the changing role of the region in the governance of transport policy in Wales from its bottom-up emergence in the mid-1990s, through a process of institutionalization or ‘hardening’ via the development of statutory regional transport plans (RTPs), its apparent demise and recent resurrection. The paper draws upon an analysis of official documents and semi-structured interviews conducted with a wide range of national and regional stakeholders over the course of the previous 15 years, which were all recorded and fully transcribed. Interviewees ranged from officials within the Welsh Government, the chairs and officials of the previously constituted regional transport consortia, the Welsh Local Government Association (WLGA) and representative organizations, such as Sustrans and Passenger Focus. These interviews were analysed using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software, and quotations are used to identify key issues highlighted by this analysis.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section examines in more depth the concepts of ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ spaces within the context of ‘structural’ and ‘relational’ forms of ‘filling in’ and outlines the theoretical framework operationalized within the paper. Section 3 provides an overview of the ‘rise’ of the region within transport policy in the post-devolved context in Wales. Section 4 explores the institutionalization or ‘hardening’ of the regional spatial imaginaries driven primarily by the policy and decision-making processes around the RTPs. Section 5 briefly explores the demise of the regional transport consortia in 2014, and the relative ‘stickiness’ of the region spatial imaginary which has led to the resurrection of regional working via corporate joint committees (CJCs) in 2021/22. The paper concludes by drawing on the findings of the empirical case to consider the potential policy-related and wider theoretical implications of ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ spaces in enhancing our understanding of complex processes of state restructuring and processes of institutionalization.

2. EXPLORING COMPLEX PROCESSES OF ‘FILLING IN’: ‘SOFT’ AND ‘HARD’ SPACES

The strength of ‘filling in’ as a conceptual tool, as noted in the previous section, lies in its ability to move beyond the national state orientation of ‘hollowing out’ and provide insights into the ‘spatially contingent evolution of governance within particular territories or regions’ (Jones et al., Citation2005, pp. 338–339). The original formulation of ‘filling in’ encompassed two dynamics based on Storper’s (Citation1997) distinction between institutions, defined as ‘customary, and sometimes informal, rules of practice between groups and individuals’, and organizations, characterized as ‘programmed and prescriptive political and administrative reforms’ (Jones et al., Citation2005, pp. 339–340). Shaw and Mackinnon (Citation2011) argue that this distinction is important but the adoption of organizational and institutional categories is problematic given that the former appears to encompass both structural and agency elements. Drawing on the topographical approach to power developed by Allen (Citation2011a, Citation2011b) and Allen and Cochrane (Citation2007, Citation2010), they present a refined version of ‘filling in’ which explicitly distinguishes structure and agency through structural ‘filling in’ focused on the ‘establishment of new institutional forms and the reconfiguration of existing organisations’ and relational ‘filling in’ centred on ‘how such organisations operate in terms of the utilisation of their power and the development of links with other organisations and actors’ (Mackinnon et al., Citation2008, p. 206). This distinction between structural and relational forms of ‘filling in’ provides important insights into the role of actors in the often highly politicized and contested processes of state restructuring (Jessop, Citation2008).

The need to consider both the structural and relational consequences of state restructuring is similarly highlighted by Haughton et al. (Citation2010, p. 11) who argue that state restructuring can be understood as not just ‘a simple redistribution of powers to other scales of government and governance, but a change to the ways in which governments seek to pursue their aims’. They argue that the increased scalar complexity and growing significance of partnership or collaborative governance approaches within spatial planning, local economic development and area regeneration has shaped both the creation of new structures and the behaviour of actors. Haughton et al. (Citation2010, p. 52) characterize traditional ‘hard spaces’ of governmental activity as involving statutory responsibilities, linked to legal obligations and processes, such as democratic engagement and consultation. These spaces are characterized as ‘slow, rigid, bureaucratic, expensive and exclusive, by virtue of the costs, specialist language and legalistic format associated with participation’. They argue that due to the mismatch between these formal processes and the more fluid, porous nature of networks and policy communities which have characterized the shift towards collaborative governance, these ‘hard spaces’ have been supplemented and increasingly subverted by the emergence of ‘soft spaces’. Haughton et al. (Citation2010, p. 52) argue that these ‘soft spaces’ represent a ‘deliberate attempt to insert new opportunities for creative thinking, particularly in areas where public engagement and cross-sectoral consultation has seen entrenched oppositional forces either slowing down or freezing out most forms of new development’. Therefore, these new spaces have been characterized as providing a potentially valuable way around obstacles or blockages within decision-making in order ‘to get things done’ or to disrupt established ways of working or thinking (Othegrafen et al., Citation2015).

The distinction between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ spaces has proven influential, and, as Purkarthofer and Granqvist (Citation2021) note, scholars have identified ‘soft spaces’ at various spatial scales, across a wide range of countries and geographical contexts and in different policy fields. Important theoretical developments have sought to move these concepts beyond a simple ‘hard-soft’ dichotomy and explored how ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ spaces may evolve through processes of ‘softening’ or ‘hardening’, or demonstrate hybrid qualities (Allmendinger et al., Citation2014; Metzger & Schmitt, Citation2012; Zimmerbauer et al., Citation2017; Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2020). Metzger and Schmitt (Citation2012, p. 266), for example, argue that these spaces may undergo ‘processes of solidification, whereby soft spaces are transfigured into harder, more clearly regulated and governed spaces through the establishment of more rigid and strictly formatted and regulated socio-material forms of spatial organisation’. Similarly, ‘hard’ spaces may undergo processes of ‘softening’ or deinstitutionalization, characterized by Zimmerbauer et al. (Citation2017, p. 680) as ‘like peeling an onion layer by layer until nothing is left’. Zimmerbauer and Paasi (Citation2020, p. 785) begin to explore these processes and argue that due to their basis in established political and administrative structures, ‘the softening of hard spaces can thus be more complex and frictional than the hardening of soft spaces, which can happen almost unintentionally or at least without much effort’. The deinstitutionalization of ‘hard’ spaces may prove more challenging because of both the formal institutional architecture and ‘stickiness’ of the space in terms of people’s consciousness and memories (Zimmerbauer et al., Citation2017). However, if ‘soft spaces’ engage in processes of hardening or institutionalization, what implications does this have for the functions and the character of power relations within these institutions? Could this potentially lead to a worse-case scenario whereby these evolving spaces incur many of the costs of both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ spaces but few of the benefits? This paper explores these questions by analysing the changing role of the region in the governance of transport policy in Wales since the mid-1990s.

3. THE RISE OF THE REGION

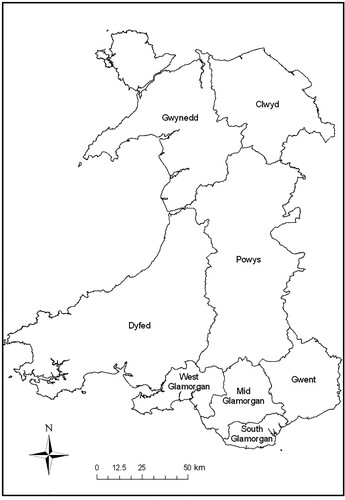

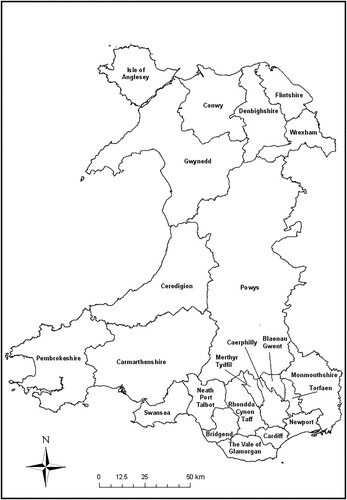

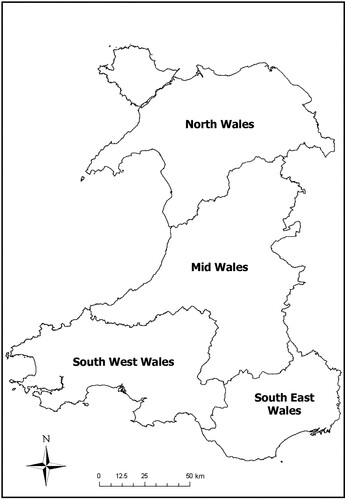

The emergence of regions in the governance of transport in Wales was shaped by two key developments in the mid-to-late 1990s: the reorganization of local authorities in 1996, and the introduction of the National Assembly for Wales in 1999.Footnote1 First, the 1996 reorganization of local authorities replaced the existing two-tier structure of eight county councils and 37 district councils with a single tier of 22 unitary authorities ( and ). The rationale that underpinned these changes centred on the perceived benefits of a unitary system, including improved accountability to local people, the removal of friction between counties and districts, better coordination of local service delivery and enhanced administrative efficiency (Pemberton, Citation2000). However, the extent to which the 1996 reorganization established a system which was fit for purpose in terms of the delivery of public services and strategic policy areas such as transport was questionable. In particular, the unitary authority structure does not reflect wider travel-to-work areas, presents challenges for developing integrated responses to issues around commuting and congestion, and led to serious concerns being raised regarding the capacity of smaller unitary authorities to develop and manage transport schemes.

Second, the introduction of the National Assembly for Wales in 1999 marked a fundamental shift in the governance of Wales, but the range of transport powers included in the original Government of Wales Act 1998 was extremely narrow (Smyth, Citation2003). Before the introduction of devolution, the Welsh Office had relatively limited transport functions, and primary responsibility for the development and delivery of policy lay with local authorities and at the UK level with the Department of Transport. Bradbury & Stafford (Citation2008, p. 69) note that the perception of the Welsh Office was that of ‘an agent of the Department of Transport’ and its core role was to simply ‘welshify’ UK transport policy. Therefore, it is perhaps unsurprising that a transport official within the Welsh Government explained that there was widespread recognition that the National Assembly for Wales had inherited ‘very fragmented transport powers … [that] weren’t at all coherent’. It is within this context of suboptimal local authority boundaries and fragmented powers that the newly devolved administration faced the difficult task of responding to a variety of policy problems, notably severe congestion on the main coastal road corridors in the North and South, high car dependency within ‘deep rural’ areas of Mid-Wales and promoting North–South links as part of wider cultural and economic ‘nation-building’ (Bradbury & Stafford, Citation2008).

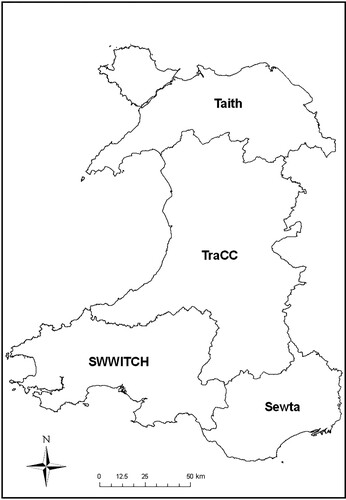

The emergence of voluntary regional level structures, regional transport consortia, designed to promote cross-boundary collaboration between local authorities around transport planning and delivery can be characterized as a bottom-up response to the problems created by local government reorganization (). An official within the South East Wales consortia, South East Wales Transport Alliance (Sewta), for example, explained that ‘whereas in a County Council you had a function covered by three people, it may now be covered by in-effect a third of a person and that obviously has a big impact on the way services are delivered’. Therefore, the consortia were perceived as delivering a range of benefits including economies of scale, enhanced capacity and a more strategic approach to transport planning (Martin et al., Citation2011). The development of these voluntary regional partnerships reflected many of the attributes that characterize ‘soft spaces’, such as providing new spaces for collaboration and ‘creative thinking’ outside of the formal local government boundaries. However, the extent to which the structural dimension of ‘filling in’ was matched by a relational dimension, leading to a reconfiguration of power relations and behavioural culture is perhaps more difficult to assess.

This process of ‘filling in’ at the regional level did not develop uniformly across Wales and the four consortia evolved along very different trajectories. The most well-developed partnership, Sewta, was formed in April 2003 following the merger of two pre-existing partnerships, South Wales Integrated Fast Transit (Swift) and Transport Integration in the Gwent Economic Region (Tiger) which had emerged in the immediate aftermath of the 1996 reorganization. The central rationale that underpinned Sewta’s formation was the high level of interdependency between local authorities in responding to problems related to commuting and transport flows. The South West Wales Integrated Transport Consortium (SWWITCH) was formed in 1998 as a direct response to the perceived success of Swift and Tiger in South East Wales. A SWWITCH official explained that the partnership was initially based on ‘purely pecuniary’ factors and the realization that Swift and Tiger were ‘actually being given money to develop things and perhaps we can get some money if we work together as well’. In contrast, Trafnidiaeth Canolbarth Cymru (TraCC) and Taith reflected the ‘layering’ of the consortia on the inherited institutional landscape and originated as transport subgroups within their respective regional economic partnerships – the Mid-Wales Partnership and North Wales Economic Forum – which had been established in the mid-1990s. The result was that the consortia adopted the same boundaries as the regional economic partnerships, leading to the Gwynedd local authority area being divided between the two.

There was also a gulf between the consortia in terms of levels of funding, the number of constituent local authorities whose resources and capacity they could draw on and the distribution of the population across the four regions (). The largest partnership, Sewta, was able to pool the resources of 10 constituent local authorities, whereas the smallest, TraCC, was only able to draw on two-and-a-half. There were also significant variations between constituent local authorities within the consortia. The SWWITCH region, for example, faced transport problems created by both relatively densely populated urban areas and sparsely populated rural areas with poor transport links. The different institutional legacies of the consortia and their attempts to reconcile potentially competing policy priorities framed the parallel process of ‘filling in’ centred on the newly devolved level.

Table 1. Regional transport consortia – key attributes.

The inadequacy of the transport powers transferred to the National Assembly for Wales in the original Government of Wales Act 1998 were a recurring theme in the early years of devolution. Following a long and tortuous process of lobbying the UK Government and securing tacit support from local government, the Welsh Government secured a raft of further powers through the Railways Act 2005 and Transport (Wales) Act 2006 (Bradbury & Stafford, Citation2008, Citation2010). The legislation conferred a ‘general transport duty’ on the National Assembly for Wales and required production of a statutory Wales Transport Strategy (WTS) (HM Government, Citation2006). The 2006 Act also replaced the existing local transport plan (LTP) system centred on individual authority plans with statutory regional transport plans (RTPs) which were required to be consistent with the WTS. A transport official within the Welsh Government explained that this addressed an inherent weakness of the pre-existing transport planning system whereby ‘there was no mechanism by which we could influence what local authorities were doing other than through the funding, so we couldn’t influence their policies or strategies at all’. Furthermore, the legislation provided powers for the assembly to establish joint transport authorities (JTAs) to deliver transport functions in place of the local authorities if needed. Unsurprisingly, these measures were opposed by the WLGA which argued that JTAs represented a top-down model of ‘dictate and deliver’ (WLGA, Citation2004, p. 2) and that the existing voluntary regional partnerships should deliver the statutory RTPs. These proposals were accepted by the Welsh Government but the threat of JTAs remained a useful policy lever over the existing arrangements (Bradbury & Stafford, Citation2008).

Overall, it is possible to identify the emergence of regional transport consortia as part of a wider process of ‘filling in’ at the regional level within Wales. In much of the pre-Transport (Wales) Act 2006 period, the consortia operated on largely informal lines and encompassed many of the characteristics of ‘soft spaces’ identified by Haughton et al. (Citation2010). The requirement to develop statutory RTPs, driven from the top-down by the Welsh Government, can be seen as the key stimulus in the institutionalization or ‘hardening’ of these ‘soft spaces’ (Metzger & Schmitt, Citation2012; Van der Heijden, Citation2011). Although the consortia themselves did not become statutory bodies, due to the increased demands created by the task of submitting statutory RTPs the consortia took steps to strengthen and formalize their working arrangements. This process of institutional development was facilitated by increased revenue support from the Welsh Government which supplemented the resources provided by constituent local authorities for the core activity and full-time staff of the consortia (Martin et al., Citation2011). In line with Othegrafen et al.’s (Citation2015, p. 217) general observation about ‘soft spaces’, the original rationale for the consortia was not to create ‘hard’ institutional structures, but the requirement to produce RTPs meant that they increasingly resembled ‘an in-between phase in moving towards a new institutionalised space’.

4. THE HARDENING OF REGIONAL SOFT SPACES

Although the introduction of statutory RTPs marked a key stage in the institutionalization or ‘hardening’ of the regional level, the consortia remained largely dependent upon the goodwill and support of their constituent local authorities. On the one hand this process could be seen as bringing the strengths of soft spaces into the formal transport planning process, depoliticizing the process to circumvent tensions and conflicts, and delivering a more coherent, integrated response to policy problems (Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2020). On the other hand, by formalizing these arrangements many of the perceived benefits of soft spaces originally identified by Haughton et al. (Citation2010), such as flexibility and scope for innovation, were potentially undermined. Furthermore, the degree to which this structural process of ‘filling in’ was complemented or matched in relational terms by a strengthening of ‘regional assemblages’ was questionable (Allen & Cochrane, Citation2007). This section focuses on four key aspects of the RTP process to examine the institutionalization of the region and explore the potential implications of the ‘hardening’ of previously ‘soft’ spaces.

4.1. Developing effective decision-making arrangements

The legal status of the consortia dictated that their decision-making mechanisms centred on joint committees or boards made up of voting members from each constituent local authority. The extent to which the membership of these boards reflected the wide-ranging membership of Allen and Cochrane’s ‘regional assemblages’ or the diverse mix of actors characterized as common in ‘soft spaces’, varied across the four consortia. In the Sewta and SWWITCH regions, for example, a range of representative groups from across transport modes and fields were included as permanent non-voting members and were expected to provide regular verbal and written reports. However, there was a clear sense across all of the consortia that the process of institutionalization had a profound effect on the operation of these boards. A Sewta official pointed out, for example, that a common problem with the board in the early days of the RTP process was that ‘half the councillors didn’t turn up’ and those that did were ‘leftover councillors’ who simply needed to be given a role. The introduction of the statutory RTPs and a linked programme of funding was widely perceived as making constituent local authorities and their members take the consortia and therefore the ‘region’ more seriously.

The organizational structures which emerged to support the boards varied across the four consortia but were identified in all of the regions as providing the central arena for negotiations around the drafting of regional strategic priorities. Underneath the boards were directorate or management groups and working groups made up of senior officials from the constituent local authorities, members of the consortia core staff and key stakeholders. Officials identified the use of the directorate and management groups, pre-meetings and informal discussions between officials and members as important elements in resolving many of the areas of tension around the RTPs before they reached the formal board meetings. An unintended consequence of this approach appears to have been the exclusion of many non-local authority actors at key stages in the bargaining around regional priorities. A transport stakeholder explained that:

by the time things have got to the Joint Committee, the official papers are as read and obviously you can comment upon them at the meeting but really your best hope is to influence what goes in that paper before it gets there.

4.2. Enhancing policymaking capacity

The extent to which the consortia were able to provide the enhanced policymaking capacity required to develop the RTPs was shaped by the institutional legacies of the four ‘regions’. The consortia were ‘very heavily’ dependent on constituent local authorities to provide additional staff and expertise (public transport stakeholder). Sewta was perceived by officials and stakeholders alike as being the best resourced, which can partly be explained by the region’s long history of collaboration and ability to draw on 10 constituent local authorities. For example, in the year following its formation, Sewta stated that over 50 local authority planning and transport officers were involved to ‘a greater or lesser extent’ in Sewta work (Sewta, Citation2005). In contrast, a TraCC official argued that the institutional legacy of transport policy in Mid-Wales meant that historically member authorities had not applied for Transport Grant funding and therefore ‘staff and resources internally (within councils) tended to be put into other areas’.

The primary financial support for the core teams within the consortia was provided by revenue funding from the Welsh Government. For example, in the 2009/10 financial year the consortia receiving a total of £1,648,500 (Sewta = £672,000; SWWITCH = £413,700; Taith = £320,250; TraCC = £242,500) (Welsh Assembly Government, Citation2009). Initially, this funding was confirmed on an annual basis, effectively meaning that the long-term future of the consortia was never guaranteed. However, as the consortia shifted from the development of RTPs to the delivery of projects, the Welsh Government opted to provide a fixed annual revenue support of £150,000 (Wales Audit Office, Citation2011). The consortia’s dependence upon local authorities and the Welsh Government for resources highlighted the imbalance between the different scales of governance within Wales and the comparative weakness of the ‘regional’ level. Furthermore, there was evidence that the formalization of regional arrangements appeared to have unintended consequences on transport planning and delivery capacity at the local level. A SWWITCH official noted that two constituent local authorities did not replace transport planners following the publication of the RTP and that this may be due to a perception that ‘they feel they don’t need their own expert’ because the consortia performed that function. Therefore, rather than complementing the local authorities or ‘hard spaces’ of subnational transport planning, the consortia or regional ‘soft spaces’, may have increasingly begun to replace them.

4.3. Promoting collaboration

Given the relative weakness of the ‘region’ compared to the ‘local’ and ‘national’ scales, it is perhaps unsurprising that the most serious challenge facing the consortia in the development of the RTPs was the ability of the constituent local authorities to identify genuine regional priorities. A Welsh Government transport official pointed out that prioritization was a ‘big ask’ for the consortia because ‘each authority tends to have its own favourite scheme’ and to abandon this self-interest required ‘quite a lot of maturity’. Unsurprisingly, the consortia officials and members interviewed were more optimistic regarding the ability of local authorities to do so. The chair of the Sewta board reflected that it was inevitable that ‘individual members representing their own authority will obviously have ambitions and we would all like to see our own projects go forward’. However, the experience of joint working through the consortia arrangements had made board members feel like ‘more of a team’. The deputy chair of the Sewta board explained that collaboration was based on the assumption that:

maybe one authority will get a substantial sum one year or maybe two years, whereas maybe another authority may get very little but because they all buy into it and feel engaged in it, they know that they are in the programme and their projects may be two or three years down the line when the full plan is delivered.

Although it is open to question whether the development of RTPs marked a process of relational ‘filling in’ and a reconfiguration of ‘informal rules of practice, cultural norms, and political loyalties’, it is important not to underestimate the progress that was made in terms of promoting collaboration at the regional level (Jones et al., Citation2005, p. 340). The chair of TraCC, for example, reflected the importance of building a working relationship between the constituent local authorities based on trust and openness:

what I wanted to achieve … when we sat around the table was to think that we are actually working together as a team. … Let’s be up front with each other because we have got the opportunity that if we think somebody is being treated unfairly, let’s put it right and it might be that another scheme has to take a lower priority but let’s all walk away where we consider we have reached a common goal for the area.

4.4. Shifting to delivery

The initial institutionalization or ‘hardening’ of the regional level can be seen as a combination of ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ factors, but as the consortia shifted from the development of strategic priorities in RTPs to the actual delivery of transport projects, the latter came to the fore. The MAG review was critical of the consortia, stating that they ‘do not appear to be adding any significant value and there is no evidence that they have made any significant progress in terms of delivering the Assembly Government’s transport priorities’ (MAG, Citation2009, p. 55). Thus, it recommended that transport functions should either be transferred to newly established JTAs at the regional level or fully centralized within the Welsh Government at the national level. However, rather than adopt either of these approaches, the Welsh Government carried out its own review of transport planning and delivery arrangements in 2009–10 ‘to make sure that the regional consortia are able to deliver the lead priorities that they have identified in their plans’ (Welsh Government official).

The review engaged the WLGA and consortia in developing a preferred model which focused on two core elements. First, revised programme and project management controls were introduced, and whilst the consortia retained primary responsibility for the delivery of projects, they were required to submit business plans for the schemes that would be taken forward and seek Welsh Government approval if schemes exceeded a financial threshold (Wales Audit Office, Citation2011). A Welsh Government official explained that the logic was to maintain the autonomy of the consortia but reduce risk by giving the Welsh Government ‘a much tighter control of schemes and projects’. Second, a series of reconfigured governance arrangements to administer these new programme and project management systems were introduced at both the national and regional levels. The latter were supported by the commitment to provide the fixed annual revenue support, as noted above, and were intended to provide a degree of uniformity across the four regions. These changes were the culmination of an increasingly ‘top-down’ hardening of the consortia designed to embed the region into the statutory process of transport planning and delivery. Indeed, it is questionable whether by the early 2010s the consortia still retained the core features of ‘soft spaces’ identified by Haughton et al. (Citation2010).

5. THE DEMISE AND RESURRECTION OF THE REGION?

Despite continued interest in the potential introduction of JTAs and wider debates around major local government reform, the consortia appeared to be a well-established feature of the transport governance architecture. In evidence to an assembly committee in January 2013, the then-Minister for Local Government and Communities, Carl Sargeant, stated that he was ‘not pursuing JTAs with any vigour at all’ and that he was ‘putting a lot of faith’ in enhancing the strength and capacity of the consortia (National Assembly for Wales, Citation2013). However, just one year later in January 2014, his successor, Edwina Hart, announced that to deliver ‘better value for money’ the revenue funding provided to the consortia would be removed and once again capital funding would be allocated on a competitive basis directly to local authorities via LTPs due by the end of January 2015 (Welsh Government, Citation2014). Although local authorities were given the option of continuing to collaborate in the preparation of new LTPs, the withdrawal of financial support in effect signalled the demise of the consortia. This process can be characterized as one of deinstitutionalization, with the structural elements of ‘filling in’ being removed.

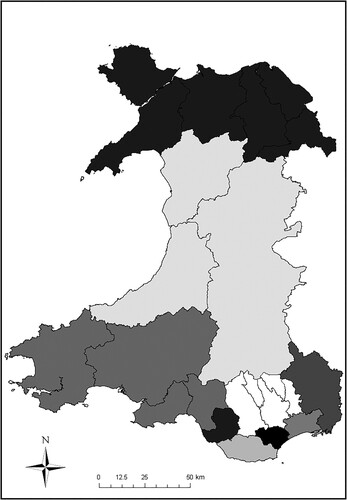

Despite the withdrawal of funding, the regional partnerships continued to form the basis of the LTPs in the Mid, North and South-West regions, although the consortia themselves were either wound up or subsumed into other structures once the process was completed. In marked contrast, the South-East region fragmented into six separate LTPs, although there was a high degree of similarity across them (). A local transport planner in the South-East region explained that this was the result of a shared desire to ‘rescue’ the Sewta objectives but also a recognition that ‘nobody had time to do anything new’, so the previous RTP provided the foundations for the LTPs. There was also continued recognition of the need to respond to transport-related issues that crossed local authority boundaries – for example, the final newsletter published by SWWITCH in March 2014 stated that ‘whilst it is inevitable that there will be changes in terms of capacity (fewer staff) and outward signs (branded website, materials, papers etc) what will not change is the determination of the four Authorities to work with each other’ (SWWITCH, Citation2014). The reality was that the regional spatial imaginaries that underpinned the consortia were relatively weak beyond the range of actors directly involved. For example, a former consortia official reflected that one of the big failures of the consortia was to not ‘have any public image’ – both in terms of the general public and within the Welsh Government and National Assembly for Wales. Establishing the consortia in the public consciousness might have made their demise less straightforward, and the reality was that few would have been aware of their passing.

Despite the demise of the consortia, the continued recognition that transport issues don’t fall neatly within local government boundaries meant that the ‘region’ continued to exist, albeit in a more disjointed form reflecting the type of layering of spatial imaginaries identified by Hincks et al. (Citation2017). The City Deals in the Cardiff Capital Region and Swansea Bay City Region, agreed in March 2016 and 2017, respectively, provided a renewed focus for regional collaboration, and both established transport subcommittees using the same boundaries as Sewta and SWWITCH. In North and Mid-Wales collaboration also continued to some extent via the North Wales Economic Ambition Board and Growing Mid Wales partnership. Furthermore, developments in transport policy continued to raise the question of the most appropriate mode of governance for Wales, such as projects such as the South Wales Metro, and the creation of Transport for Wales in 2015 as a national level, wholly owned, not-for-profit company to provide support and expertise in the management and delivery of transport projects.

The Welsh Government’s 2018 White Paper, Improving Public Transport, directly addressed these questions and to some extent could be seen as recognition of the mistake made in abolishing the consortia. The White Paper proposed two options: a single JTA for the whole of Wales with regional delivery boards, and the combination of a national JTA responsible for national/strategic functions and three regional JTAs with regional/implementation functions (Welsh Government, Citation2018). However, neither option was adopted, and instead the new Welsh transport strategy published in March 2021, Llwybr Newydd, announced the planned re-introduction of RTPs and the creation of four corporate joint committees (CJCs) to develop them and plan services at the regional level (Welsh Government, Citation2021). The CJCs were set up as separate corporate bodies comprised of constituent councils but are democratically accountable through their constituent councils. Although these new bodies are not carbon copies of the consortia, for example, the boundaries have been shifted to move Gwynedd entirely into the North Wales CJC (), they do mark a shift back to the previous governance model and highlight the ‘stickiness’ of the regional spatial imaginary.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The emergence and development of the regional transport consortia within Wales, followed by their demise and subsequent resurrection, provides a useful example of the increasingly complex character of governance associated with forms of state restructuring via processes of ‘hollowing out’ and ‘filling in’. This paper has sought to operationalize a conceptual framework drawing on Haughton et al.’s (Citation2010) distinction between ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ spaces of governance and the related literature exploring processes of ‘hardening’ or ‘institutionalisation’ (Allmendinger et al., Citation2014; Metzger & Schmitt, Citation2012; Zimmerbauer et al., Citation2017; Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2020). The analysis of the role of ‘soft spaces’ within this context reinforces Haughton et al.’s (Citation2010, p. 234) argument that such governance arrangements are ‘contingent on historically and place-specific processes of political contestation’ and the phased building, demolition and rebuilding of regions (Hincks et al., Citation2017). However, it also echoes Jones’s (Citation2022, p. 55) use of plasticity to characterize regions as ‘temporary permanencies’ reflecting the complex interplay of past and present in shaping this process. Therefore, in understanding the emergence of new spatial scales and structures it is crucial to understand the institutional and political legacies within which these processes take place.

The origins of the regional partnerships lay in a ‘bottom-up’ process driven by local authorities in response to the ‘hollowing out’ of the County Councils via reorganization. However, the strengthening and formalization of the consortia can be seen as an increasingly ‘top-down’ process driven by the attempts of the newly devolved administration to gain influence or ‘reach’ over transport policy at the subnational level (Allen & Cochrane, Citation2010). A key element of this process was the gradual ‘hardening’ or ‘solidification’ of the consortia, highlighting the contested and continuously evolving nature of ‘filling in’. In both structural and relational terms, the territorial construct of the ‘region’ in transport policy in Wales remained relatively weak in comparison to local and national levels, and throughout this period was repeatedly constructed and deconstructed. For example, whereas the 22 local authorities in Wales have resisted repeated reorganization attempts, the consortia were effectively dissolved at the whim of a single Welsh Government Minister. To echo the point made by Morgan (Citation2007), although on some level the consortia were underpinned by the porous nature of transport flows within Wales, the context for governance arrangements remained bounded by the point that politicians at both the local and devolved levels remained held to account through the territorially defined ballot box. Metzger and Schmitt (Citation2012, p. 277) raised the question as to whether processes of hardening provide an increased durability, and the experience of the consortia would appear to confirm their point that the more rigid the structure, the more easily it can break under pressure. In many senses, the ‘hardening’ of consortia made them more brittle, and less resilient to change – losing some of the key features associated with ‘soft spaces’ but without inheriting the durability of ‘hard spaces’.

Whilst the relative ‘structural’ and ‘relational’ weakness of the consortia meant that their demise was relatively swift, the ‘stickiness’ of the regional spatial imaginary meant that it survived in some form beyond the dissolution of the consortia, driven by the shared understanding amongst many actors within the transport policy community of the disjuncture between the local and national levels, and the key policy challenges facing Wales. This case highlights the utility of attempts to move beyond the binary division highlighted in the introduction to this paper and engaging with a multidimensional approach reflecting the complex process of the continuous making and remaking of regions. It is early days, but the regional level in transport planning and delivery is back, but its durability will likely be tested again. The debate around the size and scale of local authorities in Wales will return to the forefront of governance debates at some stage, and whilst the Welsh Government retains the power to create JTAs, the balancing act between the local, regional and national levels is likely to continue to spark tensions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The ideas developed in this paper benefited from discussions with colleagues at various away-days and conferences, notably collaborators on previous projects, Professor Jonathan Bradbury and Professor Alistair Cole. The author also thanks the anonymous referees for their comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The names adopted by the devolved administration and legislature in Wales have changed since the introduction of devolution in 1999, reflecting the evolving nature of the devolved settlement. The devolved administration started using the ‘Welsh Assembly Government’ formulation in 2002 in order to distinguish it from the National Assembly for Wales, but the two were not formally separated until the Government of Wales Act 2006. This name was changed to the ‘Welsh Government’ in practice in 2011, and in law by the Wales Act 2014. In May 2020, the National Assembly for Wales itself was renamed to ‘Senedd Cymru’ or ‘the Welsh Parliament’ when section 2 of the Senedd and Elections (Wales) Act 2020 came into force. Throughout this article the devolved administration is referred to as ‘Welsh Government’, the ‘National Assembly for Wales’ is used for the pre-May 2020 period and ‘Senedd Cymru’ is used for the post-May 2020 period.

REFERENCES

- Allen, J. (2011a). Powerful assemblages? Area, 43(2), 154–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2011.01005.x

- Allen, J. (2011b). Topological twists: Power’s shifting geographies. Dialogues in Human Geography, 1(3), 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820611421546

- Allen, J., & Cochrane, A. (2007). Beyond the territorial fix: Regional assemblages, politics and power. Regional Studies, 41(9), 1161–1175. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701543348

- Allen, J., & Cochrane, A. (2010). Assemblages of state power: Topological shifts in the organization of government and politics. Antipode, 42(5), 1071–1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00794.x

- Allen, J., Massey, D., & Cochrane, A. (1998). Rethinking the region. Routledge.

- Allmendinger, P., Chilla, T., & Sielker, F. (2014). Europeanizing territoriality – Towards soft spaces? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 46(11), 2703–2717. https://doi.org/10.1068/a130037p

- Amin, A., Massey, D., & Thrift, N. (2003). Decentering the nation: A radical approach to regional inequality. Catalyst.

- Bradbury, J. (2021). Constitutional policy and territorial politics in the UK volume 1: Union and devolution 1997–2007. Bristol University Press.

- Bradbury, J., & Stafford, I. (2008). Devolution and public policy in Wales: The case of transport. Contemporary Wales, 20, 67–85.

- Bradbury, J., & Stafford, I. (2010). The effectiveness of legislative mechanisms for the devolution of powers in the UK: The case of transport devolution to Wales. Public Money & Management, 30(2), 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540961003665511

- Brenner, N. (2009). Open questions on state rescaling. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 2(1), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp002

- Cole, A., & Stafford, I. (2015). Devolution and governance: Wales between capacity and constraint. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Davies, R. (1999). Devolution: A process not an event. Institute of Welsh Affairs.

- Entwistle, T. (2006). The distinctiveness of the Welsh partnership agenda. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 19(3), 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513550610658196

- Goodwin, M., Jones, M., & Jones, R. (2005). Devolution, constitutional change and economic development: Explaining and understanding the new institutional geographies of the British state. Regional Studies, 39(4), 421–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400500128432

- Goodwin, M., Jones, M., & Jones, R. (2006). Devolution and economic governance in the UK: Rescaling territories and organizations. European Planning Studies, 14(7), 979–995. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310500496446

- Harrison, J. (2008). Stating the production of scales: Centrally orchestrated regionalism, regionally orchestrated centralism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32(4), 922–941. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00815.x

- Harrison, J. (2010). Networks of connectivity, territorial fragmentation, uneven development: The new politics of city-regionalism. Political Geography, 29(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2009.12.002

- Harrison, J. (2013). Configuring the new ‘regional world’: On being caught between territory and networks. Regional Studies, 47(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.644239

- Harrison, J., Smith, D. P., & Kinton, C. (2017). Relational regions ‘in the making’: Institutionalizing new regional geographies of higher education. Regional Studies, 51(7), 1020–1034. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1301663

- Haughton, P., Allmendinger, P., Counsell, D., & Vigar, G. (2010). The new spatial planning: Territorial management with soft spaces and fuzzy boundaries. Routledge.

- HM Government. (2006). Transport (Wales) Act 2006. The Stationery Office (TSO).

- Himsworth, C. M. G. (1998). New devolution: New dangers for local government? Scottish Affairs, 24(1), 6–28. https://doi.org/10.3366/scot.1998.0033

- Hincks, S., Deas, I., & Haughton, G. (2017). Real geographies, real economies and soft spatial imaginaries: Creating a ‘more than Manchester’ region. Region International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 642–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12514

- Hudson, R. (2007). Regions and regional uneven development forever? Some reflective comments upon theory and practice. Regional Studies, 41(9), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701291617

- Jeffery, C. (2009). Devolution in the United Kingdom: Problems of a piecemeal approach to constitutional change. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 39(2), 289–313. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjn038

- Jessop, B. (1990). State theory: Putting the capitalist state in its place. Polity.

- Jessop, B. (2001). Institutional re(turns) and the strategic–relational approach. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 33(7), 1213–1235. https://doi.org/10.1068/a32183

- Jessop, B. (2002). The future of the capitalist state. Polity.

- Jessop, B. (2008). Institutions and institutionalism in political economy: A strategic–relational approach. In J. Pierre, B. G. Peters, & G. Stoker (Eds.), Debating institutionalism (pp. 210–231). Manchester University Press.

- Jessop, B., Brenner, N., & Jone, M. (2008). Theorizing sociospatial relations. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26(3), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1068/d9107

- Jones, M. (2022). For a ‘new new regional geography’: Plastic regions and more-than-relational regionality. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 104(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2022.2028575

- Jones, M., & Macleod, G. (2004). Regional spaces, spaces of regionalism: Territory, insurgent politics and the English question. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 29(4), 433–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-2754.2004.00140.x

- Jones, R., Goodwin, M., Jones, M., & Pett, K. (2005). Filling in the state: Economic governance and the evolution of devolution in Wales. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 23(3), 337–360. https://doi.org/10.1068/c39m

- Laffin, M., Thomas, A., & Webb, A. (2000). Intergovernmental relations after devolution: The National Assembly for Wales. The Political Quarterly, 71(2), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.00297

- Mackinnon, D., & Shaw, J. (2010). New state spaces, agency and scale: Devolution and the regionalisation of transport governance in Scotland. Antipode, 42(5), 1226–1252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00800.x

- Mackinnon, D., Shaw, J., & Docherty, I. (2008). Diverging mobilities? Devolution, power and transport policy in the UK. Elsevier.

- Malabou, C. (2008). What should we do with our brain. Fordham University Press.

- Martin, S., Downe, J., Entwistle, T., & Guarneros-Meza, V. (2011). Learning to improve: An independent assessment of the Welsh government’s policy for local government. Welsh Government.

- Massey, D. (2007). World city. Polity.

- Metzger, J., & Schmitt, P. (2012). When soft spaces harden: The EU strategy for the Baltic Sea region. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(2), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44188

- Ministerial Advisory Group on the Economy and Transport (MAG). (2009). Phase 2 report on transport. Welsh Assembly Government.

- Mitchell, J. (2009). Devolution in the UK. Manchester University Press.

- Morgan, K. (2007). The polycentric state: New spaces of empowerment and engagement? Regional Studies, 41(9), 1237–1251. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701543363

- National Assembly for Wales. (2013). Carl Sargeant, Minister for Local Government and Communities, evidence to The Enterprise and Business Committee Inquiry into Integrated Public Transport, Thursday, 24 January 2013. https://business.senedd.wales/ieListDocuments.aspx?CId=228&MID=1319

- Othegrafen, F., Knieling, J., Haughton, G., & Allmendinger, P. (2015). Conclusions and outlook. In P. Allmendinger, G. Haughton, J. Knieling, & F. Othengrafen (Eds.), Soft spaces in Europe: Re-negotiating governance, boundaries and borders (pp. 215–235). Routledge.

- Paasi, A., & Metzger, J. (2017). Foregrounding the region. Regional Studies, 51(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1239818

- Peck, J. (2001). Neoliberalizing states: Thin policies/hard outcomes. Progress in Human Geography, 25(3), 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913201680191772

- Pemberton, S. (2000). The 1996 reorganization of local government in Wales: Issues, process and uneven outcomes. Contemporary Wales, 12, 77–106.

- Purkarthofer, E., & Granqvist, K. (2021). Soft spaces as a traveling planning idea: Uncovering the origin and development of an academic concept on the rise. Journal of Planning Literature, 36(3), 312–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412221992287

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Gill, N. (2003). The global trend towards devolution and its implications. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 21(3), 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0235

- Shaw, J., & Mackinnon, D. (2011). Moving on with ‘filling in’? Some thoughts on state restructuring after devolution. Area, 43(4), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2011.01032.x

- Smyth, A. (2003). Devolution and sustainable transport. In D. I, & S. J (Eds.), A new deal for transport? The UK’s struggle with the sustainable transport agenda (pp. 30–50). Blackwells.

- South East Wales Transport Alliance (Sewta). (2005). Paper on the constitution of the Sewta Central Support unit. Sewta board meeting, 28 September. http://www.sewta.gov.uk/board.htm

- Storper, M. (1997). The regional world: Territorial development in a global economy. Guilford.

- SWWITCH. (2014). SWWITCH Newsletter, March. http://www.swwitch.net/resources/1/newsletters/SWWITCH%20Newsletter%20MAR%202014.pdf, accessed 30/04/2014

- Thomson, A. M., Perry, J. L., & Miller, T. K. (2009). Conceptualizing and measuring collaboration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 19(1), 23–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum036

- Van der Heijden, J. (2011). Institutional layering: A review of the use of the concept. Politics, 31(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.2010.01397.x

- Varró, K., & Lagendijk, A. (2013). Conceptualizing the region – In what sense relational? Regional Studies, 47(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.602334

- Wales Audit Office. (2011). Major transport projects.

- Welsh Assembly Government. (2009). Regional transport consortia revenue support for 2009/10. Welsh Assembly Government.

- Welsh Government. (2014). Guidance to local transport authorities – Local transport plan 2014.

- Welsh Government. (2018). Improving public transport.

- Welsh Government. (2021). Llwybr Newydd: The Wales transport strategy 2021.

- Welsh Local Government Association (WLGA). (2004). Draft Transport (Wales) Bill: Evidence to the Welsh Affairs Select Committee and Economic Development and Transport Committee, National Assembly for Wales. Welsh Local Government Association.

- Zimmerbauer, K., & Paasi, A. (2020). Hard work with soft spaces (and vice versa): problematizing the transforming planning spaces. European Planning Studies, 28(4), 771–789. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1653827

- Zimmerbauer, K., Riukulehto, S., & Suutari, T. (2017). Killing the regional leviathan? Deinstitutionalization and stickiness of regions. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 676–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12547