ABSTRACT

Why are China’s notoriously competitive local governments increasingly cooperating with each other? Combining interjurisdictional cooperation data from 820 counties and fieldwork in 24 localities, we argue that the increasing trend of inter-county cooperation is the newest manifestation of China’s state-rescaling initiative. It is the combined result of the state’s devolution of governance responsibilities and competitive-minded local cadres’ interests in benefits associated with scaling up. The study contributes to understanding how counties’ growing interdependence intersects with the regime’s survival logic in the unfolding reconfiguration of China’s counties.

JEL:

1. INTRODUCTION

Relations between local governments in China are notoriously frosty. In China’s system of decentralized authoritarianism, local leaders are driven to compete for promotion up the political ladder by striving to outdo each other on economic and social targets written into the cadre evaluation system (Zhou, Citation2007; Zuo, Citation2015). While some see these local political tournaments as the driving force behind China’s unprecedented economic transformation (Xu, Citation2011), this zero-sum competition also has the negative unintended consequence of breeding enmity between local officials. The multitude of ‘broken roads’ (断头路) across China – highways which come to an abrupt end at administrative borders – are just one potent symbol of the high barriers to cooperation between competitive local governments. This paper suggests that this status quo of discord in local China’s interjurisdictional relations is in a nascent state of change at the county level (县级).

Our analysis begins from the observation that county-level governments are increasingly joining forces in the provision of public goods in certain regions of China. They form partnerships to transfer poverty alleviation funding and know-how from wealthier to poorer counties. They cooperate on transboundary ecosystem management. They unite in regional cooperation blocs to build harmonized transport systems. And they sometimes even share policing duties. While certain interjurisdictional cooperation practices have longer lineages in local Chinese politics, others are quite new, and all of them are occurring with more frequency since Xi Jinping’s coming to power. The research questions we pursue here are: How and why are China’s asocial county governments suddenly seeking out connection?

Combining insights from scholarship on Chinese politics and urban planning literatures (Jaros, Citation2016; Li & Wu, Citation2012, Citation2018), we identify inter-county cooperation as the newest manifestation of ‘state rescaling’ in China, by which we mean the processes of change within states through which new hierarchies of state spatiality are generated (Brenner, Citation2004). The state rescaling framework provides this article with two theoretical bases. It first gives us a means of analysing state rescaling against the ‘contextually specific political strategies that engendered them’ and linking it to China’s political economy at both national and local levels (Brenner, Citation2009, p. 127). Second, drawing on research highlighting state agency (Jessop, Citation2002; Lim, Citation2017), this article identifies different forms of state intervention in generating rescaling outcomes. We argue that the new form of state rescaling in China is a nationally coordinated process that is a combined result of the central government’s devolution of responsibility for public goods provision and county-level governments’ pursuit of new state power (through the acquisition of capital and technological know-how) via inter-county cooperation (Chien, Citation2013). The two rationalities work independently in certain types of rescaling, and are mutually reinforcing in others, producing different types of rescaling initiatives. While these processes serve to upscale county-level governments’ regulatory and economic power, they remain subject to the whims of a central state seeking solutions for environmental crisis and regional inequality.

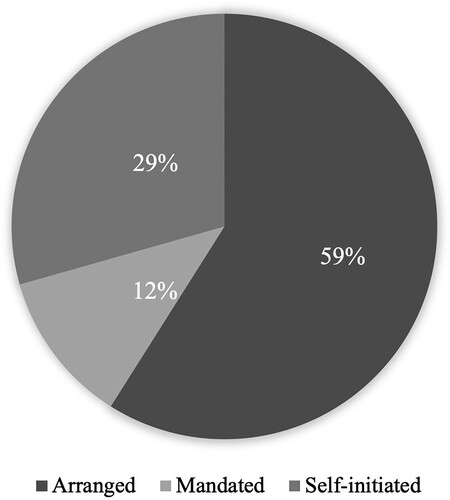

Based on the specific political–economic conditions in which inter-county cooperation occurs, we identify three mechanisms through which the rescaling process unfolds: arranged, mandated and self-initiated. Arranged cooperation refers to inter-county partnerships that are brokered above the heads of the parties involved. In recent years, they have emerged as a key tool in China’s poverty alleviation campaign, a centrepiece of Xi’s administration. Forms of mandated cooperation emerge directly between local governments with little to no coordination from above but are responses to new governance mandates emanating from Beijing. Self-initiated cooperation, by contrast, is negotiated in bottom-up fashion directly between local governments and is not driven directly by changes in state policy.

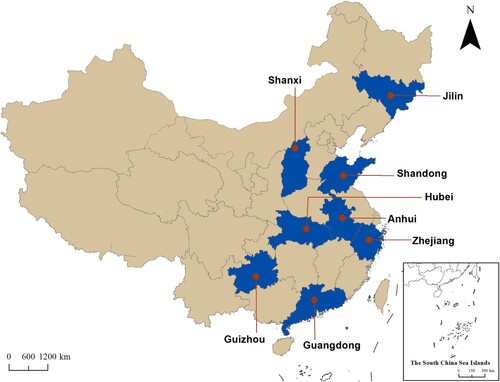

We employ a nested research design including both quantitative and qualitative data (Lieberman, Citation2005). To analyse the overall patterns, we compiled a dataset of 1,126 county-level cooperation cases from 820 counties (2009–20) across eight provinces located in coastal, central and north-eastern China ().Footnote1 We also conducted in-depth fieldwork in 24 locations in Anhui, Zhejiang, Shanxi, and Beijing between July and December 2019. Our findings draw on 76 semi-structured interviews with officials and NGO workers at local levels, and decision-makers in Beijing, focusing on issue areas that produced most cooperation based on our dataset: poverty reduction, environment and economic development.

The paper makes four broad contributions. First, while prior studies of state rescaling in China focus on the creation of city regions, we advance the study of China’s state rescaling by examining how it is unfolding at very local levels in China’s five-tier administrative system.Footnote2 Second, theoretically, we provide a comprehensive categorization of state rescaling in counties and unpack the role of the state in different rescaling initiatives. Third, our paper contributes to studies of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) authoritarian survival in the field of Chinese politics by highlighting the crucial role that interjurisdictional cooperation plays in delivering (or not) on Xi’s agenda (Dickson, Citation2016; Nathan, Citation2003). Finally, our findings extend recent scholarship examining how China’s political tournaments – seen by many as the secret to China’s high-growth success – are shifting along with the emergence of new priorities (Zhou, Citation2007).

2. INTERJURISDICTIONAL RELATIONS IN CHINA: FROM CELLULAR TO COMPETITIVE TO COLLABORATIVE?

The transition from the command economy in Maoist era to ‘reform and opening’ (改革开放) under Deng Xiaoping prompted a transformation in relations within the local state from cellularity to competition. Shue (Citation1990) characterizes the local state under Mao as a ‘honeycomb’ made up of cell-like units rigidly separated from one another. In rural China, this cellularity was the combined result of the vertically oriented planning system, Mao’s emphasis on regional self-reliance and tight enforcement of the household registration (户口) system which made movement even out of one’s village a rare occurrence as late as the 1970s (p. 136). Following Mao’s death, economic and political reforms post-1978 gradually replaced the autarky of the Maoist period with fierce competition between local officials for promotion up the political ladder. Zhou Li-an’s (Citation2007) seminal work highlights economic growth as the essential currency of these local political tournaments. Other applications of the theory have found tournament dynamics behind local revenue collection patterns (Lü & Landry, Citation2014), spatially uneven local debt levels (Pan et al., Citation2017), and even the number of local coal miner deaths (Shi & Xi, Citation2018).

While tournament competition has been interpreted as the institutional foundation of China’s great economic transformation (Xu, Citation2011), state-sanctioned rivalry between local officials has also generated negative unintended consequences over time. Amid growing concerns about high rates of ‘wasteful’ investment in many industries, even the Party’s leading official journal has pointed to growth-focused tournament competition as a primary source of excessive investment (Seeking Truth, Citation2013). This chronic investment fever at local levels has fuelled ‘duplicated construction’ (重复建设) across localities and reinforced a longer term trend of local protectionism (Poncet, Citation2003). Local officials’ competitive instincts have also contributed to the 6000 km of ‘broken roads’ in China’s highway system, as prefectural officials are reluctant to pay for transportation links that have positive spillover effects for neighbouring localities (Liu & Zhou, Citation2017). And as China’s environmental regulations have become core components of local officials’ performance evaluations,Footnote3 local officials have devised means of strategically ‘polluting thy neighbour’ by passing water pollution on to their neighbours to avoid bearing the costs of abatement themselves (Cai et al., Citation2016).

Interjurisdictional competition remains deeply embedded in local Chinese politics. However, there are also signs of growing collaboration on infrastructure and economic development, particularly in China’s thriving coastal regions, as well as on non-economic topics. Given their status as China’s most economically advanced regions, the Pearl River Delta (PRDFootnote4) and Yangtze River Delta (YRDFootnote5) regions have led the way in regional cooperation initiatives involving deepening ties across administrative borders and high degrees of polycentricity (Liu et al., Citation2016).Footnote6 Another driver of interjurisdictional cooperation is China’s new approach to development, best captured by the ‘Five-in-One’ socialist goals which aim at establishment of an ‘economic, political, cultural, social and ecological civilization’. The 2014 declaration of a ‘war on pollution’ marked a key moment in the enactment of this strategy and regional governance experimentation has featured prominently in conducting the ‘war’. One prominent example is the Action Plan for Preventing and Controlling Air Pollution in Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei and the Surrounding Regions which established transboundary mechanism to manage air quality in this mega-region.

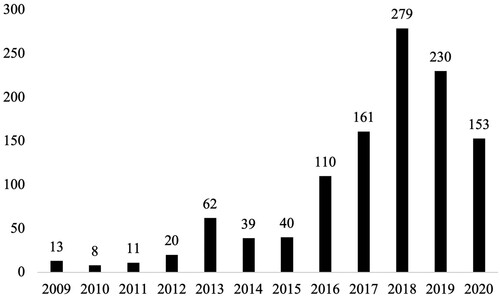

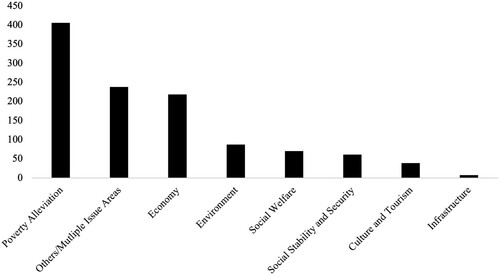

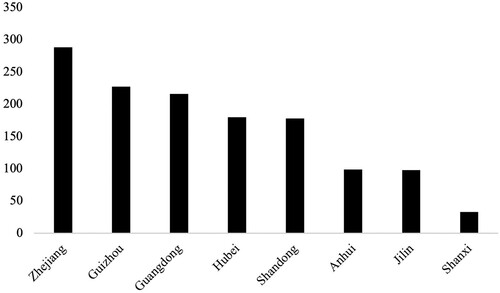

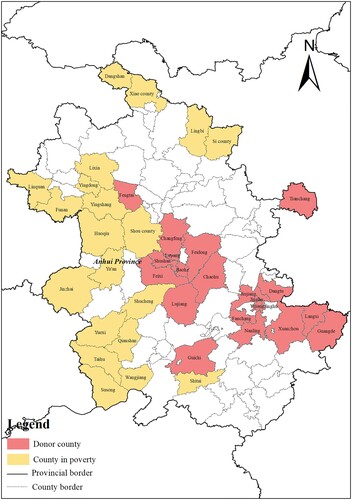

Our database suggests that county-level interjurisdictional cooperation rose markedly over Xi’s tenure as leader (2012–) ().Footnote7 The increase in cases from 2013 is attributable largely to a surge in poverty alleviation partnerships as part of Xi’s campaign to eliminate extreme poverty by 2020 (). shows a slight decrease in 2019 and 2020. This reflects both the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the fact that the campaign was scheduled to end in 2020. The geographical characteristics of our data () are partially consistent with past research pointing to the prosperous coastal regions as the most fertile ground for interjurisdictional cooperation (Guangdong, Zhejiang, Shandong) with lower frequencies in less prosperous regions (Shanxi, Anhui, Jilin). The two exceptions are the high numbers of cases in Hubei and Guizhou, which are explained by the high proportion of poverty alleviation partnerships with many counties assigned to pair up with coastal counties as aid recipient counties.

What explains this curious combination of competitive and cooperative behaviours among China’s county-level governments? Why are local officials in a zero-sum game with peers suddenly collaborating? In the following section we draw on the scholarship of state rescaling in formulating an analytical framework to make sense of this trend.

3. STATE RESCALING: THEORIES AND DEVELOPMENT

3.1. Evolution of the state-rescaling literature

Originally proposed in the 1970s, the concept of state rescaling depicts the process of ‘transformations of state spatiality’ at subnational scales in response to the regulatory crisis of the state (Brenner, Citation2004). Examples of early state rescaling projects include the transformation from Keynesian welfare national states to the ‘glocalization’ which prioritized urban areas as engines for growth with entrepreneurial cities working to be integrated within the global circuits of capital in post-1970s Western Europe (Brenner, Citation2004). City governments, including Milan, Paris and Frankfurt, gained more autonomy from national governments in this period and formulated place-specific socioeconomic policies to attract capital while at the same time assuming more fiscal responsibilities (Gualini, Citation2006).

Recent contributions to the state rescaling literature have used the framework to analyse the creation of state power at different scales and across different contexts. The accumulation of empirical cases, however, has also posed new questions and challenges for the theory. Two such debates are particularly relevant to the study of state rescaling in China: first, the relation between the state and subnational scales; and second, the political–economic context of rescaling initiatives. While the devolution of regulatory power to subnational entities in the late 1970s was once seen as the ‘hollowing out’ of the state (Jessop, Citation2002), later studies argue that rather than following a ‘zero sum’ logic, the rescaling of regulatory power should be understood as the state’s active redefinition of inter-scalar relations (Brenner, Citation2009, p. 126). Oftentimes, devolution is one of several options for the state rather than an inevitable outcome. In the case of South Korea’s Roh Administration, for instance, a devolution policy option was up against a regional balance option, and eventually the latter won out with the state creating several mega projects including the Sejong City and Innovative Cities to relocate state agencies (Sonn, Citation2010). Even during the processes of devolution, as in the case of the rise of large-scale metropolitan regions in EU countries during the 1990s, the rescaling itself was part of the state’s strategic institutionalization of inter-jurisdictional competition to ‘position local and regional economies within supranational circuits of capital’ (Brenner, Citation2004, p. 481).

The redefining of the state’s role in rescaling further opens room for the discussion of the political–economic contexts that shape rescaling outcomes. The transformation of state spatiality is essentially, as Brenner (Citation2004, p. 458) pointed out, a ‘path-dependent layering process in which inherited and emergent projects interacted conflictually’. Emergent projects interact not only with extant scaling projects, but also with the political–economic institutions against which the projects are implemented. For instance, the variation of economic reconfiguration outcomes under the UK-wide devolution policy during Prime Minister Tony Blair’s first two administrations provides compelling evidence of local political–economic conditions’ impact. In this case, local governments and social forces negotiated hard for their preferred strategies, actively reshaping the state’s plan (Goodwin et al., Citation2006).Footnote8

3.2. State rescaling in China

With insights from the rescaling literature on state agency and the importance of political–economic conditions in the processes of rescaling, we now turn to the case of China. To begin with, the state plays the predominant role in both the formulation of rescaling plans and the shaping of agendas to incentivize local governments’ scaling up efforts (Lim, Citation2017; Wu, Citation2016). For instance, behind the rise of city-regionalism in China – urban agglomerations defined by a core city and its surrounding areas – is Beijing’s effort to curb the downsides of negative entrenched local competition and foster a more coordinated and sustainable development mode (Harrison & Gu, Citation2021). At the same time, the state’s rescaling down to the city-regions also relies on the CCP’s hierarchical and performance-based personnel management system, with the promotion of lower-level officials largely decided by their performance on a list of targets assigned from the top, which now includes Beijing’s region building initiatives (Edin, Citation2003; Li & Wu, Citation2018).

While the state is the primary engineer of rescaling initiatives, these processes are also shaped by an array of political, economic, and social forces (Lim, Citation2017). For instance, as Lim’s (Citation2017, p. 1586) amended state rescaling framework suggests, the outcome of rescaling in China is intertwined with inherited developmental pathways. In the case of city-regionalism, despite the state’s plan to use city-regionalism for a more sustainable development route, the processes remain conflictual as many city officials treat the region-building initiatives as means for land acquisition (Yang et al., Citation2019), a primary source of revenue for local governments in the ‘growth at all costs’ era. Similarly, Shaanxi province’s attempt to integrate the neighbouring Xi’an and Xianyang and build the greater Xi’an metropolis ended up reproducing, if not exacerbating, provincial-city and inter-city turf battles over the distribution of earmarked fundings and resources (Jaros, Citation2016).

In this article, we use the state rescaling analytical framework to examine the rise of China’s inter-county cooperation. While still limited, the study of state rescaling in China’s counties has made progress in recent years as counties have begun to scale up in order to enhance their state power by increasing developmental competence and expanding territorial space (Chien, Citation2013). Just like ‘entrepreneurial cities’ in western Europe, China’s ‘entrepreneurial counties’ played a crucial role in its economic transition and became an important locus of growth. The low administration rank of counties, however, limits their say in planning and budgeting; scaling up is attractive to county officials as a means of enhancing their power and authority in China’s hierarchical political system (Chien, Citation2013). Based on Chien’s (Citation2013) decade-long research on China’s entrepreneurial counties, he identified three mechanisms to acquire such new state power through scaling up: reclassification of ‘counties’ to ‘county-cities’, upgrading local leaders’ administrative rank, and territorial expansion through inter-county cooperation. In other words, rescaling in China’s counties served as a ‘spatial-fix’ to expand counties’ developmental space.

Our research engages with the existing literature on state rescaling in China’s counties and expands it by highlighting different rationalities driving counties’ cooperation-based scaling up efforts. In so doing, this article speaks to the broad literature of state rescaling in identifying the roles of an authoritarian state and the existing political–economic conditions in shaping the outcome of rescaling initiatives. First, our empirics suggest that expanding developmental space is just one of the many motives behind the observed cooperative trend between counties. Like Europe in the 1970s, this new form of state spatiality in China’s counties is also a result of the state’s crisis management strategy (Brenner, Citation2004), as counties are increasingly called upon to play a role in reversing environmental degradation and narrowing regional development gaps (Li & Wu, Citation2012). For a central government eager to guard its fiscal resources, horizontal partnerships are an attractive means of offloading the high costs of an expanding list of public goods promised to citizens (Jiang et al., Citation2021). Second, the top-down imposed governance responsibilities also intertwine with local political–economic conditions, creating the unevenness of the advancement of counties’ scaling up efforts across localities and across issue areas. The inherited political–economic conditions include, for instance, the CCP’s performance-based cadre evaluation system, local fiscal capacity, and counties’ location (both geographical and jurisdictional)

In the following section, we identify different mechanisms through which the observed trend of state-rescaling in China’s counties unfolds. While some mechanisms are directly tied to the state’s scale-specific policies that devolve ‘new responsibilities for planning, economic development, social services’ downwards to the counties (Brenner, Citation2004, p. 472), other mechanisms derive from counties’ activism for new state power through inter-county cooperation. All are a function of the CCP’s performance-based cadre management system which rewards counties’ scaling up efforts, whether in fulfilling the state’s devolution of responsibilities or in achieving economic growth.

4. RESCALING THROUGH INTER-COUNTY COOPERATION

State-rescaling at the county level is unfolding through three mechanisms of inter-county cooperation, each with different rationalities and forms (). Arranged cooperation takes the form of explicitly top-down state policy directives and entails upper-level authorities (such as provincial and prefectural government) directly match-making between county governments for the purpose of addressing a widening regional development gap. It is by far the largest category in our database, making up 59% of cases (). Poverty alleviation partnerships account for the vast majority of such cases but arranged marriages are also found in other issue areas including partnership between state-funded trade unions. Self-initiated cooperation refers to bottom-up linkages initiated by local governments themselves. Such projects are most often focused on economic topics and are typically the result of less-developed counties seeking ties with prosperous localities, or jointly initiated by counties with complementary endowments to have a size effect on the market. Mandated cooperation (12%) has both top-down and bottom-up features. It is formed freely by counties without the direct intervention of state matchmaker but is, nonetheless, a response to mandates from above. Mandated cooperation is particularly closely associated with China’s new generation of stringent environmental policies aiming for rapid improvements in transboundary air and water quality. To achieve individual governance targets, counties have, for the first time, been required to work with neighbouring localities. Mandated cooperation is also seen in border policing which entails policemen conducting joint highway or mountain patrols as a response to Beijing’s ‘safe border’ policy. In the following, we analyse each mechanism according to (1) the precise triggers (e.g., policy interventions); (2) how partners are chosen; and (3) how receptive local governments are to cooperation (e.g., potential conflicts and contradictions). Together, the analysis offers comprehensive insights into the state’s role in this new type of rescaling, as well as the manner in which local political–economic conditions shape the initiation and implementation of rescaling efforts.

Table 1. State-rescaling through three forms of inter-county cooperation.

4.1. Arranged cooperation

Arranged cooperation has increased markedly since China’s adoption of the Five-in-One development strategy in 2012 and become a central tool in the ‘war on poverty’ initiated by Xi Jinping in 2015. While this form of arranged cooperation has many precedents in reform-era China, the political signals for cooperation have become much stronger since then, with localities increasingly forced ‘to sacrifice their own potential benefit in order to fulfil regional agendas’ (Xu & Yeh, Citation2013, p. 134). For example, with the Opinions on Poverty Alleviation through Inter-County Cooperation, Anhui paired 20 economically developed counties with 20 counties in need (). The Anhui government keeps a very close eye on the partnerships and even ranks the 40 participating counties according to how cooperative they are. One official described how striving to look like a good partner actually became a priority: ‘our rank among the forty counties fell behind in 2018 because we were busy with other targets. [After the ranking], our attention turned to fulfilling this partnering thing’ (transcript 009).

While the terms of such agreements are mostly predetermined, the provincial documents also purposefully leave room for a degree of local officials’ discretion. For example, while Anhui province assigned several mandatory tasks to the donor county, including horizontal transfers of 10 million RMB per year and mandated agricultural produce purchase,Footnote9 counties are also encouraged to improvise based on their own endowments. In the effort to play this new game of ‘impression politics’ (Huang & Zhou, Citation2019), county X went above and beyond its contractual obligations by pairing up four townships under its jurisdiction with four counterpart townships from the poorer county Y. Each township is tasked with providing four million RMB in aid to each of its counterpart towns, on top of the ten million already transferred to the poorer county Y under the provincial matchmaking scheme.

In matchmaking counties, upper-level authorities also consider social foundation for cooperation, such as the compatibility between economy structures and cultural and historical proximity. As a provincial official working on poverty alleviation explained: ‘even though it is like an arranged marriage … the prefectural government would still run a comprehensive evaluation. They need to evaluate the county’s cultural traditions, major industries, etc. You cannot match two counties with completely different industries’ (transcript 002). As an example, the two paired counties described above are both famous for their lotus industry and in the course of their partnership, co-hosted a ‘Lotus Festival’ to attract tourists. Similar complementarities undergird another Anhui poverty alleviation arranged marriage: one county known for its ecological crab farming cooperated with its ‘spouse’ county on developing a crab farming business since the latter has the perfect natural conditions for crab farming.

Poverty alleviation pairings can be quite contentious since the pairings involve large horizontal transfers of government revenue, and county leaders’ receptivity and openness to them is highly conditional on the donor county’s economic strength. As an official from a prosperous county told us: ‘honestly, (transferring) ten million yuan is nothing to us. We learned a lot from the county we helped’ (transcript 003). In comparison, another donor county with much weaker fiscal capacity complained bitterly about the pressure to donate their hard-won government revenue: ‘who loves giving out money to other counties? No way!’ (transcript 005).

4.2. Mandated cooperation

Mandated cooperation arises when the governance issue in question is transboundary in nature and also a central state policy priority. It falls predominantly in the areas of environment, infrastructure, and border security.

4.2.1. Cooperation on the environment

The increasing trend of counties joining forces in environmental governance is closely linked to China’s declaration of a ‘war’ on pollution with mounting environmental targets incorporated to the state’s recent Five-Year Plans (e.g., 2011–15, 2016–20), the ultimate governance guideline. Many of the environmental targets effectively require or encourage interjurisdictional cooperation. Ambitious local officials wishing to make a good impression on their superiors have no alternative but to work with their peers (Huang & Zhou, Citation2019), as cooperation is connected to local governments’ individual efforts to achieve stricter environmental standards, attainment of which are ‘hard’ targets in local government performance’s evaluation (Ran, Citation2013). As one local head of the Ecology and Environment Bureau discussing the necessity of coordinating with his counterparts on the other side of a provincial border to maintain air quality standards put it, ‘What are our alternatives? Build a wall?’ (transcript 033).

The introduction of rules mandating cooperative management of transboundary ecosystems has substantially increased pressure on polluting localities to change their ways. For example, when Anhui province began enforcing the Rules for Anhui Surface Water Eco-Compensation in 2018, many counties, especially those in downstream locations, had already tried to initiate bilateral negotiations, generally without much success. Reaching agreement with recalcitrant upstream counties was said to be much easier once the provincial policy came into force (transcript 036). For instance, one county in Anhui had fought with its upstream neighbour for years over water quality issues, involving two drawn out lawsuits. It was only following introduction of the provincial policy that the downstream county finally succeeded in getting its neighbour to sign an eco-compensation agreement.

Upstream local governments may also proactively initiate cooperation when they perceive marketizing their ecological products as a means of revenue generation. This is especially common when the upstream locality economically lags behind its downstream neighbour. Examples include the eco-compensation agreement between Huangshan city and Hangzhou since 2012, and between Lu’an and Hefei since 2014. In both cases, the upstream city’s economy was underdeveloped. In the Lu’an-Hefei case, Lu’an had long sent clean water to Hefei and, with the introduction of eco-compensation rules, saw an opportunity to marketize the water quality and ‘sell’ it downstream (transcript 005). Typically, this type of deal is not warmly welcomed by downstream localities since they are accustomed to enjoying clean water for free, and thus tend to complain that ‘it is [the upstream locality’s] obligation to protect the environment’ (transcript 001).

Counties’ water shortages can also trigger cooperation when local government with scarce water resources purchases claims on water resources in neighbouring counties. There are several such cases in prosperous regions we studied, where local governments are fiscally capable to enter such arrangements. We found that the counties in need of water often take the first step. In one instance, one county built a tunnel directly linking to the water reservoir in another county, for which it paid a vast sum, on top of utility charges. In 2018, the water-seeking county negotiated an increase of provision to 80 million m3 per year.

4.2.2. Cooperation on infrastructure

Local infrastructure needs are another driver of mandated cooperation. The building of roads, ports and, in recent years, highspeed rail, often take shape in the context of central- or city-level planning activities, exemplified by the national highway development plans as well as other spatial plans promulgated by the National Development and Reform Commission (Liu & Zhou, Citation2017). Yet, infrastructure projects are very decentralized in practice, partly because local governments often provide the bulk of financing themselves. Such projects often require extensive bilateral collaboration and improvisation in long and complex processes involving demolition and even forced migration.

Power (a)symmetry between negotiating parties often shapes interjurisdictional project outcomes. In circumstances of decentralized transportation infrastructure construction, conflict often emerges when developmentally weaker localities attempt to link up with their richer neighbours. There is typically an asymmetry of enthusiasm between ‘have-not’ and ‘have’ localities since the poorer localities generally have more to gain from smoother transport links. This dynamic has contributed to the ‘broken road’ phenomenon mentioned earlier because the less enthusiastic rich localities sometimes simply refuse to connect to infrastructure development across borders (Liu & Zhou, Citation2017). During our trip to one area on the border of three provinces, we observed many broken roads on the side of poorest province since it has the greater need for connection with its highly developed provincial neighbours.

Conditions of symmetrical cooperation are more propitious for infrastructure development across borders. One such example arises in a border area between two poorer provinces, a setting in which one would expect high barriers to cooperation since this is an underdeveloped region separated by an institutionally thick border. One county took the initiative to construct a highspeed railway station on a top-down designed line that connects directly to Shanghai. Local officials approached their counterparts in the county on the other side of the provincial divide to coordinate their road construction plans so that residents from both places would benefit from the new station. The mayor of the project-initiating county related how surprising their offer was to officials in the other county:

When we started making plans for our new railway station, we also made one for them. It was funny. Our Bureau of Transport just brought the plans to them and showed how they should design their roads so that residents could use our station. They were confused and wondering why we are doing this. They kept asking us, ‘brother, why are you being so nice?’ They thought we definitely wanted something from them. They think people are selfish and will not do something unless it serves their own interests.

(transcript 007)

4.2.3. Cooperation on security

Security cuts across jurisdictional boundaries and counties are increasingly joining hands in the provision of this public good. Behind this trend is Beijing’s grand ‘Safe China’ (平安创建) initiative which first emerged in the early 2000s yet has gained in importance since the 2010s. Our dataset shows that a large portion of security cases are for collaboration on the inhibition and control of crimes in border areas – where criminals are known to hide precisely because they know policing is weak. The chance of building such cooperation increases if the bordering administrative units are already familiar with one another and face common threats. For example, one county located in a mountainous region along a provincial border, had been advocating for a border security alliance with its neighbours since the late 2000s due to the rise of illegal activities such as gambling and illegal sand mining (transcript 019). Local officials decided to initiate talks first with neighbouring counties within the same prefecture since ‘we meet them all the time during city-level meetings’ (transcript 019). After first persuading them, the officials then extended the cooperation to bordering counties in other prefectures and even difference provinces.

4.3. Self-initiated cooperation

Self-initiated cooperation directly links to local government’s pursuit of state power in terms of capital acquisition and developmental space. As such, it typically centres on economic projects, including joint construction of industrial parks, formation of investment promotion alliances, and the founding of regional economic organizations. Partnerships between local governments typically form between counties with significant development gaps or complementary industry structures. Agreements are often signed between the counties’ Federation of Industry and Commerce (FIC) or the Bureau of Investment Promotion (BIP), with the aim of providing networking opportunities for local entrepreneurs and attracting investment. Such agreements entail regular business trips to the partner county, and occasional co-hosting of seminars and charity events (transcript 007). Informants from an inland county revealed that almost all factories in a newly built industry park were invested through connections made during the cooperation with coastal FICs (transcript 007).

Two triggers are behind local officials’ seeking out for cooperation on their own initiative. First, officials in less-developed regions often desired to partner up with counties in coastal regions. Not only are they attracted by the potential economic benefits of establishing friendly relations with well-to-do localities (Chien, Citation2013), they appear also to be lured by the prestige of linking to the coast. In an inland county, local officials from the Development and Reform Commission explained to us why they preferred long-distance cooperation with coastal counties than with immediate neighbours:

We only talk to counties from developed regions. We want to learn from them. We need to visit the best places – Zhejiang, Jiangsu, or Shanghai – and even foreign countries. We are aiming for the best and we have to talk to the best.

(transcript 035)

Second, while less developed counties prefer prosperous coastal partners, they will not miss an opportunity to take advantage of a rich neighbour, referred by local officials as the ‘gold rush’ (淘金) phenomenon. Such cases were often motivated by the neighbours’ sudden obtaining of top-down transferred grants or preferential policies. As a local official recounted: ‘The other county enjoys a lot of preferential treatment from the central government because it is part of China’s ‘Western Development Program’ initiative. We want to tag along and take advantage of their special treatment’ (transcript 007). In another less-developed, inland county, officials were active in both linking up with the coast and simultaneously digging for gold in the neighbour’s yard. It was in the process of setting up an office in Shanghai to attract investment when the provincial government suddenly announced its plan to build a tourist centre on a sacred mountain in the neighbouring county located in a different prefecture. In response, the county directed their township officials to prioritize cooperation with the neighbouring township where the tourist centre would be built. As an official from the ‘gold rushing’ county recounted their Party Secretary saying: ‘all townships should look to the east [coastal regions], except [township X]. [township X] needs to look west, right at [township Y], because there you have the [sacred mountain] tourist project. It is a gold mine’ (transcript 024).

5. THE DOG’S NOT BARKING: REGIONAL GAPS IN COUNTY-LEVEL RESCALING

Despite the state’s aim to scale down certain responsibilities to the counties, the processes of rescaling are advancing unevenly across China’s regions. Among the eight provinces included in our database, Shanxi has by far the fewest cooperation cases (33) despite having a larger population than two other provinces in our sample (Guizhou and Jilin). On the whole, the state of interjurisdictional relations in Shanxi province resembles the Maoist honeycomb pattern more closely than the polycentrism of contemporary China’s booming coastal regions.

The relative absence of rescaling initiatives in Shanxi are attributable to a combination of economic and political factors. First, in stark contrast to coastal provinces, Shanxi is not a dynamic, export-oriented economy. Its extractive economy is characterized by a highly fragmented coal industry which the national government has been working to consolidate through successive waves of mandated mergers between state-owned coal firms (Shen et al., Citation2012). Developing away from ‘king coal’ remains a major challenge for the province and many localities are locked in to path-dependent economic structures that date to the command economy period (Eaton & Kostka, Citation2014). Under these circumstances of heavy reliance on coal and weak economic integration across local borders, there is little functional rationale for officials to initiate joint infrastructure construction, for example.

In such regions, low levels of development also make political signals from Beijing on the Five-in-One development targets less relevant than in more prosperous regions. For example, the low number of poverty alleviation cases in Shanxi stem partly from the scarcity of prosperous counties that could assume a donor role:

Some prefectures are not financially capable of implementing this policy [the poverty alleviation partnerships]. If you look at [county X], it has several county-level cities, such as county–city X and county–city Y. They are rich. And they can therefore help other poor counties. But if the whole city is poor, you cannot even find a rich county to help the poor ones, right?

(transcript 002)

[City X] and [county Y] have been discussing eco compensation on [river X] for a long time. County Y is located upstream. But there is no conclusion. County Y asked for money in very strong terms. But city X does not want to give them. It’s a firm no. Negotiation is very, very difficult.

(transcript 001)

We do not have competition, nor do we cooperate with other counties. It is related to the evaluation system for local governments. If you look at the coastal provinces, they are preoccupied with economic development and every indicator is highly detailed and quantified. But we are different. The most important thing for Shanxi’s local governments is stability [稳定].

(transcript 004)

6. WHAT DOES COUNTY-LEVEL RESCALING IMPLY FOR INTERJURISDICTIONAL RELATIONS?

The central state’s devolution of governance combined with local governments’ activism are, in some regions of China, leading to rising rescaling efforts between counties. Some local officials interpret growing interconnection as a sign of a broad shift away from the reform era mode of highly competitive interjurisdictional relations: ‘in the past, counties treated their neighbours as enemies. But now, they gradually realize that one county is too small to achieve high-quality development’ (transcript 006).

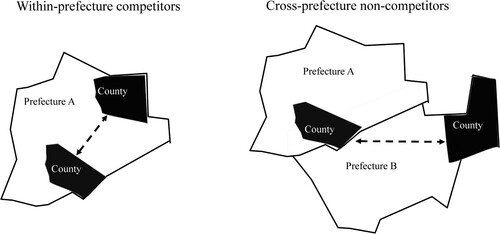

But is county-level rescaling really dampening competition between local governments? Past research suggests that answering this question requires looking closely at the nature of local governments’ relations with their immediate rivals for promotion. The core insight of the political tournament literature is that local officials in China regard each other as competitors and strive to outperform their peers in the hopes of gaining promotion up the bureaucratic ladder. However, local leaders do not perceive themselves as competing against all other officials at their level; instead they set their sights only on peers in the same administrative jurisdiction, with whom they directly compete for promotion to the next administrative level, for example, all county leaders within the same prefecture (Zhou, Citation2007). As such, leading officials in two counties divided by a prefectural border are not direct competitors for promotion, whereas leaders in two counties belonging to the same prefecture are direct rivals ().Footnote10

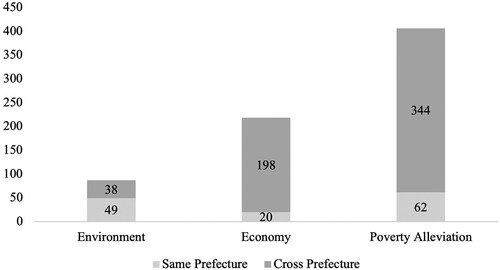

Consistent with this pattern of counties competing only with peers from within the same prefecture, interjurisdictional cooperation cases in our database are overwhelmingly formed between counties in different prefectures, that is, between non-competing localities.Footnote11 Fully 85% of our cooperation cases are cross-prefectural. This preference for cross-jurisdictional partnerships is particularly pronounced within the economic cooperation category: 91% of such cases are cross-prefectural (). We surmise that these distinctive spatial characteristics of interjurisdictional cooperation at the county level are shaped by two factors. First, as discussed above, officials often seek to exploit wide development gaps across regions. Second, in strategically selecting counterparts outside their political tournaments, county leaders hope that any benefits generated through cooperation will enhance their chances of promotion, and theirs alone. These striking spatial characteristics of inter-county cooperation suggest that this trend of county rescaling is essentially embedded in the country’s political tournament institutions and is not diluting longstanding patterns of interjurisdictional competition substantially.

7. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This article identifies the increasingly cooperative local governments in emerging networks of stronger and weaker dyadic ties in China as the newest form of state-rescaling unfolding at the county level. The argument builds on prior theorization of ‘state rescaling’ through creation of new hierarchies of state spatiality (Brenner, Citation2004, Citation2009; Lim, Citation2017). In the case of China, the pursuit of inter-county cooperation as a new state spatiality is a combined result of the state’s devolution of governance responsibilities in face of regulatory crisis (such as environment degradation and a widening regional development gap), and counties’ activism in scaling up for development opportunities and capital accumulation. The two rationalities work together as well as independently, engendering different types of initiatives.

These findings contribute to the broad state rescaling literature in two respects. By identifying multiple rationalities and tracing their interactions in shaping county-level rescaling, our work extends the rescaling literature which has so far conceptualized state rescaling mainly in relation to changes in the global capitalist system. Prior literature, whether focused on EU or China, conceives of state rescaling as driven by shifting global capitalism and states’ efforts to respond to new pressures such as the collapse of Fordist–Keynesian capitalism and China’s re-entering the capitalist system (Brenner, Citation2009; Lim, Citation2017). However, we show that changes in domestic conditions also engender state’s rescaling efforts, as our cases of arranged and mandated rescaling suggest. In both cases, the initiatives are part of the state’s political strategy to address domestic governance crises in relation to environment and inequality. We also go beyond a monocausal account in pointing to multiple sources of state rescaling trends. In the case of mandated rescaling, for instance, the central state’s strategy of devolution intersects with county-level activism in scaling up as part of local leaders’ promotion-seeking efforts.

Additionally, we engage with the analytical framework of state rescaling in highlighting both the roles of state and local political–economic conditions in shaping the outcome of the rescaling initiatives. In particular, our proposed three mechanisms of inter-county cooperation include diverse forms of state intervention (such as direct match-making and the assigning of targets). Based on different forms of state intervention, our analysis also shows how these scale-specific policies interact with local politics and economy, leading to variation in outcomes across regions. As a result, the rescaling trend is the weakest in regions with limited fiscal capacity, isolated economy, and a cadre evaluation list that places less emphasis on economic prosperity.

More specifically, our findings also speak to the state rescaling literature on China. In part, we build on and extend previous work examining the role of economic and political factors in shaping new spatial configurations in China which mostly focuses on coastal cities (Li & Wu, Citation2012; Yang et al., Citation2019). First, our analysis shows that growing economic interdependence and strong political incentives are driving interjurisdictional collaboration not only within cities but also at more local administrative scales and also beyond China’s polycentric city regions. While the emergence of city-regionalism has been dated to the early 2000s (Li & Wu, Citation2012), our database suggests that county-level rescaling is a more recent phenomenon that has only really gained momentum under Xi Jinping. Second, rather than taking the role of state as homogenous, our proposition of three different rescaling pathways at the county level shows different types of state intervention and includes discussion of the processes of their interaction with local political-economy. In so doing, we challenge the static view of rescaling as simply an existing form of hierarchy, and instead offer empirical support for Brenner’s (Citation2004) suggestion that state rescaling should be seen more as a dynamic process with diverse political, economic, and social forces in action.

Our approach also engages with Chinese politics scholarship by shedding light on how county-level rescaling is increasingly tied in with the CCP’s authoritarian survival logic (Nathan, Citation2003). As Dickson (Citation2016) has argued, the state’s new focus on charting a path of inclusive and sustainable growth is an implicit response to public opinion that is generally supportive of CCP one-party rule but ‘dissatisfied with specific policy issues such as the environment, food safety, and the cost and quality of health care and education’. However, meeting the public’s expectations on these issues entails massive state investment, costs that the central government does not want to shoulder alone. Wong (Citation2021) finds that under Xi Jinping, central to local fiscal transfers have slowed markedly in comparison to Hu Jintao’s administration (2002–12) for whom reducing inequality was a core priority. Wong (Citation2021, p. 20) argues that this ‘sharp downturn reflects a pivot in the central government’s willingness to fund local expenditures’. In circumstances of slowing government revenue growth and a more cautious approach to sending funds down to local governments, Beijing increasingly sees interjurisdictional cooperation as a core means of delivering on its expensive new governance agenda and anchors to the regime’s longevity (Nathan, Citation2003).

Additionally, our findings also shed light on how the institution of the political tournament induced by the CCP’s cadre management system is deeply imprinted on emerging patterns of inter-county cooperation. While counties are now incentivized to work together as never before, such cooperation is conditioned by the enduring zero-sum logic of the political tournament. This is suggested most clearly by the striking spatial patterns of cooperation. When county officials have free choice to select their partners, they almost always seek out non-competitors from outside their prefecture. They do so partly in the hopes of capturing any benefits generated through cooperation to improve their standing in the competition for promotion.

Finally, while our findings show that the trend of state rescaling now extends beyond China’s highly developed regions, it is not advancing evenly across regions. Inter-county cooperation remains rare in Shanxi and this is likely true of many of China’s other less-developed regions. Here neither condition of state rescaling is met. Processes of economic integration and marketization have not advanced at the same rate as they have in more prosperous regions and there is consequently little genuine economic demand for the kinds of infrastructure and development projects seen in China’s most economically dynamic regions. The central state also appears to have somewhat less leverage in its efforts to download its development priorities on local governments as officials there clearly perceive preserving stability and building guanxi ties to their superiors as determining factors in their career pathways. This suggests that Beijing’s efforts to manufacture inter-county cooperation will meet with more resistance in poorer regions where revenue is scarce and where the Party’s cadre management system cannot always be relied on to incentivize local officials to closely follow Beijing’s lead. In the years to come, we can expect both the extension of ties between counties in networked forms of state rescaling alongside the persistence of disconnection in regions where honeycomb patterns remain deeply entrenched.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The research team obtained informed verbal consent to take part in this research project from all interviewees.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Luisa Flurap, Haoying Li, Lejie Zeng and Kaiqin Li for their research assistance. Helpful suggestions from the editor and three anonymous reviewers greatly improved the quality of the paper. We also benefited from feedback on a previous draft presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, 13 September 2020.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We used 16 Chinese keywords including cooperation (合作) and agreement (协议) to scrape cases from both county government websites and Google search results. We only included cases that: (1) had a formal agreement and were implemented indicating tangible specifics such as meeting frequency and co-built project; (2) were signed by county-level government agencies or bureaus; and (3) were signed between 2009 and 2020.

2. The five administration divisions are: central government, provinces, prefectures (cities), counties and townships.

3. Chinese cadres’ performance is evaluated by the upper level government through the Target Responsibility System (TRS), which holds officials accountable for meeting targets with promotion rewards or punishment.

4. Formed by nine cities from Guangdong province and with a population of 65 million people, PRD’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020 makes up 8.8% of the country’s total value.

5. YRD is made of 26 cities across four coastal provinces. With a population of 235 million, its share of the country’s GDP amounts to 24%.

6. Past studies have also analysed specific collaborative projects in the two regions, including the construction of the Guangzhou–Zhuhai railway (Xu & Yeh, Citation2013), collaborative development projects between Shanghai and Kunshan, and the development of Nanjing’s metro transit system with neighbouring localities (Li & Wu, Citation2012; Yang et al., Citation2021). In general, regional governance experiments appear to be less common in other less-developed regions of China, although studies of the Xi’an–Xianyang New Area and the Chongqing Liangjiang New Area show that inland localities are also following suit to some degree (Jaros, Citation2016).

7. We collected both intra- and inter-provincial cases in the dataset. In calculating total cases, we only counted an inter-provincial case once. For individual provincial case summary, we counted them twice towards each recorded province.

8. Wales, for example, decided to set up two departments for economic governance with one specifically dedicated to skill development, partly because of the strong resistance from the training and enterprise councils in Wales to preserve the training delivery there (Goodwin et al., Citation2006, p. 985).

9. Information from Anhui’s provincial document, Opinion to Promote Poverty Alleviation through County Pairs, obtained through interviewee AH002.

10. Tournament-driven competition between local governments within such ‘peer groups’ has been studied in the literature. Using prefecture-level economic investment data from 2000 to 2005, Yu et al. (Citation2016) demonstrated that prefectures’ investment levels are only significantly correlated with those of their rivals, namely prefectures within the same province. Similar spatial effects have also been found at the county level. In an effort to keep up, counties tend to generate more fiscal revenue when the number of competitors within a prefecture increases (Lü & Landry, Citation2014).

11. As mentioned above, the choice for partner in mandated cooperation is largely decided by the issue at stake. In the case of eco-compensation, for instance, counties do not have much choice but to cooperate with neighbouring counties, regardless of their competition. Similarly, with other top-down-arranged cooperation such as the ‘river leader’ system where prefectural government intervened directly in river pollution management (Chien & Hong, Citation2018), our proposed spatial pattern does not apply.

REFERENCES

- Brenner, N. (2004). Urban governance and the production of new state spaces in Western Europe, 1960–2000. Review of International Political Economy, 11(3), 447–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969229042000282864

- Brenner, N. (2009). Open questions on state rescaling. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 2(1), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp002

- Cai, H., Chen, Y., & Gong, Q. (2016). Polluting thy neighbor: Unintended consequences of China’s pollution reduction mandates. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 76, 86–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2015.01.002

- Chien, S. S. (2013). New local state power through administrative restructuring – A case study of post-Mao China county-level urban entrepreneurialism in Kunshan. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 46, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.12.015

- Chien, S. S., & Hong, D. L. (2018). River leaders in China: Party–state hierarchy and transboundary governance. Political Geography, 62(October 2016), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.10.001

- Dickson, B. J. (2016). The survival strategy of the Chinese communist party. The Washington Quarterly, 39(4), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2016.1261563

- Eaton, S., & Kostka, G. (2014). Authoritarian environmentalism undermined? Local leaders’ time horizons and environmental policy implementation in China. The China Quarterly, 218, 359–380. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741014000356

- Edin, M. (2003). State capacity and local agent control in China: CCP cadre management from a township perspective. The China Quarterly, 173, 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0009443903000044

- Goodwin, M., Jones, M., & Jones, R. (2006). Devolution and economic governance in the UK: Rescaling territories and organizations. European Planning Studies, 14(7), 979–995. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310500496446

- Gualini, E. (2006). The rescaling of governance in Europe: New spatial and institutional rationales. European Planning Studies, 14(7), 881–904. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310500496255

- Harrison, J., & Gu, H. (2021). Planning megaregional futures: Spatial imaginaries and megaregion formation in China. Regional Studies, 55(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1679362

- Huang, X., & Zhou, L.-A. (2019). ‘Jiedui jingsai’: Chengshi jiceng zhili chuangxin de yizhong xin jizhi [‘Paired competition’: A new mechanism for the innovation of urban local governance]. Society, 39(5), 1–38. https://www.society.shu.edu.cn/article/2019/1004-8804/20190501.htm

- Jaros, K. A. (2016). Forging greater Xi’an: The political logic of metropolitanization. Modern China, 42(6), 638–673. https://doi.org/10.1177/0097700415616116

- Jessop, B. (2002). The future of the capitalist state. Polity.

- Jiang, X., Eaton, S., & Kostka, G. (2021). Not at the table but stuck paying the bill: Perceptions of injustice in China’s Xin’anjiang Eco-compensation program. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 24(6), 1–17. 10.1080/1523908X.2021.2008233

- Li, Y., & Wu, F. (2012). The transformation of regional governance in China: The rescaling of statehood. Progress in Planning, 78(2), 55–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2012.03.001

- Li, Y., & Wu, F. (2018). Understanding city-regionalism in China: Regional cooperation in the Yangtze river delta. Regional Studies, 52(3), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1307953

- Lieberman, E. S. (2005). Nested analysis as a mixed-method strategy for comparative research. American Political Science Review, 99(3), 435–452. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051762

- Lim, K. F. (2017). State rescaling, policy experimentation and path dependency in post-Mao China: A dynamic analytical framework. Regional Studies, 51(10), 1580–1593. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1330539

- Liu, X., Derudder, B., & Wu, K. (2016). Measuring polycentric urban development in China: An intercity transportation network perspective. Regional Studies, 50(8), 1302–1315. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1004535

- Liu, X., & Zhou, J. (2017). Mind the missing links in China’s urbanizing landscape: The phenomenon of broken intercity trunk roads and Its underpinnings. Landscape and Urban Planning, 165, 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.05.005

- Lü, X., & Landry, P. F. (2014). Show me the money: Interjurisdiction political competition and fiscal extraction in China. American Political Science Review, 108(3), 706–722. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000252

- Nathan, A. (2003). Authoritarian resilience. Journal of Democracy, 14(1), 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2003.0019

- Pan, F., Zhang, F., Zhu, S., & Wójcik, D. (2017). Developing by borrowing? Inter-jurisdictional competition, land finance and local debt accumulation in China. Urban Studies, 54(4), 897–916. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015624838

- Poncet, S. (2003). Measuring Chinese domestic and international integration. China Economic Review, 14(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1043-951X(02)00083-4

- Ran, R. (2013). Perverse incentive structure and policy implementation Gap in China’s local environmental politics. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 15(1), 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2012.752186

- Seeking Truth. (2013). Pochu ‘wei GDP lunyingxiong’ de guannian [Breaking the ‘only GDP counts’ concept]. Seeking Truth, December 6. http://www.qstheory.cn/zs/201312/t20131206_299519.htm

- Shen, L., Gao, T.-M., & Cheng, X. (2012). China’s coal policy since 1979: A brief overview. Energy Policy, 40, 274–281. 10.1016/j.enpol.2011.10.001

- Shi, X., & Xi, T. (2018). Race to safety: Political competition, neighborhood effects, and coal mine deaths in China. Journal of Development Economics, 131, 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2017.10.008

- Shue, V. (1990). The reach of the state: Sketches of the Chinese body politic. Stanford University Press.

- Sonn, J. W. (2010). Contesting state rescaling: An analysis of the south Korean state’s discursive strategy against devolution. Antipode, 42(5), 1200–1224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00799.x

- Wong, C. (2021). Plus ça change: Three decades of fiscal policy and central–local relations in China. China: An International Journal, 19(4), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1353/chn.2021.0039

- Wu, F. (2016). China’s emergent city-region governance: A new form of state spatial selectivity through state-orchestrated rescaling. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(6), 1134–1151. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12437

- Xu, C. (2011). The fundamental institutions of China’s reforms and development. Journal of Economic Literature, 49(4), 1076–1151. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.49.4.1076

- Xu, J., & Yeh, A. G. O. (2013). Interjurisdictional cooperation through bargaining: The case of the Guangzhou–Zhuhai railway in the pearl river delta, China. The China Quarterly, 213, 130–151. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741013000283

- Yang, J., Li, Y., Hay, I., & Huang, X. (2019). Decoding national New area development in China: Toward New land development and politics. Cities, 87, 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.12.030

- Yang, Liuqing et al. 2021. State-guided city regionalism: The development of metro transit in the city region of Nanjing. Territory, Politics, Governance, 1–21. 10.1080/21622671.2021.1913217

- Yu, J., Zhou, L.-A., & Zhu, G. (2016). Strategic interaction in political competition: Evidence from spatial effects across Chinese cities. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 57, 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2015.12.003

- Zhou, L. A. (2007). Zhongguo difang guanyan de jinfeng jinbiaosai moshi yanjiu [Governing China's local officials: An analysis of promotion tournament model]. Jingji Yanjiu [Economic Research Journal], 7(36), 36–50.

- Zuo, C. (2015). Promoting city leaders: The structure of political incentives in China. The China Quarterly, 224, 955–984. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741015001289