ABSTRACT

As a lagging regional economy that underperforms the rest of the UK, Northern Ireland represents a number of continuing challenges that have a long history. In recent years, technologies and processes associated with Industry 4.0 have had little impact with a few exceptions. Yet these activities have become central to industrial policy and strategies in the last two decades, in spite of the path-dependent nature of the economy. The underperformance is exacerbated by Brexit and increased hybridity of the economy due to the Northern Ireland Protocol that appears to be a form of industrial policy to be analysed.

1. INTRODUCTION

Discussing Northern Ireland’s (NI) economic past, present and future in the light of place-based perspectives is a potentially vast topic. To keep the task manageable, we provide a very brief overview of the chief insights from the place-based model. Elsewhere in the paper, the reader will be confronted with a historical overview of the NI economy in the light of the model, and there is some discussion of the relationship between the way Brexit has evolved and place-based issues, with respect to industrial strategies.

The two approaches discussed in this paper (space neutral and place based) ultimately represent different interpretations of the relationships between economic history and economic geography (Barca et al., Citation2012; Bailey et al., Citation2015, p. 291; Beer et al., Citation2020). In a memorable analogy, the ‘space-neutral’ world has been likened to a ‘smooth free-flowing river system’ (Bailey et al., Citation2015, p. 291). Space-neutral, spatially blind (or equilibrium-focused) approaches interpret effective responses to regional economic imbalances as involving the spatially blind provision of public services and regulation of product and factor markets to make an economy work more along the lines of textbook supply-and-demand models. What spatially blind approaches have in common is that they highlight price signals as well as downplay contextual factors – such as institutions, geography, history and culture – unique to particular locations. These approaches tend to view the path to development following a single route to convergence that can be imitated and diffused.

In contrast to spatially blind approaches, place-based approaches have been likened to a river facing ‘big boulders and rapids that cause many disruptions to the natural flow of the market system’ (Bailey et al., Citation2015, p. 291). Instead of the space-neutral optimistic analysis of equilibrium and unique first-best outcomes, place-based approaches discuss the possibility of underdevelopment traps and associated issues such as path dependence, sunk costs and institutional distortions. Underdevelopment traps in particular tend to be related to the interests of elites in particular locations, not enabling step improvements to occur. In contrast to the space-neutral argument, place-based models contend that space matters not just for territories, but also through externalities and the individuals who live in them. In policy terms, context and uniqueness rather than imitation are crucial in thinking about appropriate policy menus (Barca et al., Citation2012).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section investigates the models that link strategic management (SM) to the development of regional economies. The following section provides a historical overview of the path dependency of the NI economy, concluding with some commentary on the organisational weakness underlying contemporary industrial strategies. The fourth section analyses Brexit as a place-based shock to the NI economy, especially the complexity of implementing the Northern Ireland Protocol (NIP) and its consequence for both east–west and north–south economic flows, with reference to Industry 4.0 (I4.0) The penultimate section examines place-based approaches to industrial strategies in the context of I4.0, although this perspective appears to be absent from NI industrial strategies. The final section on policy implications makes some specific industrial policy observations as they relate to NI. In conclusion, the paper seeks to further open debates about the economic performance of NI and its industrial strategies within the UK economic space in the context of its increased hybridity due to Brexit and its associated governance arrangements.

2. PLACE-BASED MODELS LINKING STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT TO REGIONAL ECONOMIES

In this section we note the existence of rival perspectives on diagnosing regional economic problems in general and then consider why place-based approaches have become more relevant recently to thinking about regional policy in a range of contexts. Such place-based analyses of regional ecosystems lead us to thinking about the relationship between SM and regional economics. The abiding message from the recent literature is that it is possible to think that when industrial strategy becomes more place-based that the insights from SM regarding strategic positioning can contribute to improving regional policy formulation and application. In this sense, it is argued that strategy may be scalable from firms to regions (Bailey et al., Citation2018, Citation2020).

Underlying spatially more or less neutral approaches to regional policy is the appropriateness of model to be used. Neoclassical economic models of the simplest type tend to assume away market power, suggest that the world is ‘flat’ and that regional economic imbalances can be reversed by greater market flexibility ensuring convergence. Models of this type suggest that convergence occurs as labour supply shifts should alter relative wage rates so that previously low wage regions experience a labour outflow (thereby raising wages): while the reverse process will operate in previously high wage regions. Inflows of investment into low wage regions are premised on the same line of reasoning.

Such equilibrium-based model leads to spatially ‘blind’ or neutral view of policy in which the promotion of market flexibility is viewed as a ‘one-size-fits-all’ cure to regional economic divergence. Spatially blind policies thus are concerned with promoting market clearing or ‘getting the prices right’. In the language of industrial policy, a ‘horizontal’ (or cross-sectoral) set of policies that derive from this approach ensue. Policies aimed at promoting market flexibility across a region and those such as tax credits that range across sectors are favoured. Deregulation of planning is just one concrete outworking of this focus on improving market efficiency Likewise, there is a concern that excessive government intervention may ‘crowd out’ rather than ‘crowd in’ the operation of private sector actors. These spatially neutral models hence downplay the contextually specific aspects of regional economic development, such as economic history, and instead present market flexibility as the cure to regional economic underperformance (Bailey et al., Citation2018).

Since the 2000s within Europe and the United States, however, there has been growing dissatisfaction with the ability of spatially neutral approaches to deliver solutions to the problems of persistent regional economic underperformance. The place-based approach is a particularity based one, which acknowledges that regional geography, history, culture and institutions may lie at the heart of the problem. This place-based approach to economic geography in turn is connected to an approach that views economic history as important in explaining the paths that a regional economy may follow. This greater analytical role for economic history connects to the idea that path dependence rather than equilibrium may better characterise actual economic activity. Such an insight links the study of regional economic development to complexity (Arthur, Citation2021).

The analysis underpinning the place-based approach is to build upon the existing industrial starting point, one that recognizes the path that has been followed, rather than assume ‘horizontal’ measures will solve any problem. The key focus is for regions to generate value creation opportunities by developing (new) place-specific specialisms and capabilities, which emerge from regional geographies, histories, cultures and institutions (Barca, Citation2011).

In terms of Regional Industrial Strategy (RIS), it has become focused on Constructed Regional Advantage (CRA) and Smart Specialisation Strategies (S3) within Europe and the United States (Foray, Citation2015; Bailey et al., Citation2020,). These are distinct, but related, policy concepts that are associated I4.0 and the 4th Industrial Revolution. The European Commission defines the latter as: ‘The Fourth Industrial Revolution aims to leverage differences between the physical, digital and biological sphere. It integrates cyber-physical systems and the Internet of Things, big data and cloud computing, robotics, artificial intelligence based systems and additive manufacturing’ (European Commission, Citation2018, p. 8).

According to De Propris and Bailey (Citation2020), the origin of I4.0 goes back to 2011:

The term was coined in Germany in 2011, when the Federal Government launched a project in relation to industry–science partnerships called Industrie 4.0. It described the impact that the ‘Internet of Things’ was going to have on the organisation of production thanks to a new interplay between humans and machines and a new wave of digital application to manufacturing production.

(p. 7)

The cross-fertilization between RIS of the S3 kind and corporate strategy or SM can arise from several mechanisms. At root, the relationship between value creation and value capture may give rise to the need for public policy. Therefore, for instance, where value capture potential is limited, firms may under-invest in value creating activities.

The key is that corporate strategies may be scalable to the level of the region, so just as following Porter a firm can adopt strategic positioning that involves offering a distinctive price-quality bundle offer to consumers, whilst regions can likewise try and differentiate themselves from other regions (Porter, Citation1990; Bailey et al., Citation2020). Of course, there is a danger of both firms and regions finding themselves ‘stuck in the middle’ when trying to offer such a bundle or find that even a distinctive position can be imitated. The role of S3 in the NI RIS is implicit in its successive economic strategies whose weaknesses tend to be the adoption of ‘silver bullet’-type solutions (Quigley, Citation1976).

Turning to CRA in general, it developed as a response to the perception that EU technology and innovation policy was too narrowly focused on a few high-tech locations rather than accounting for a wider range of contexts (Boschma, Citation2014). CRA acknowledges the legacy of history for instance and it suggests that such ‘related variety’ should not be ignored in policy formulation. As Bailey et al. (Citation2020) observe:

In regions where sectors are technologically adjacent and there is a sufficient degree of cognitive proximity, there may arise opportunities for mutual learning, knowledge exchange and cross-fertilization. This may lead to technological diversification and ‘regional branching’, where new industrial and technological paths emerge out of existing embedded industrial structures.

(p. 651)

3. PATH DEPENDENCY OF THE NORTHERN IRELAND ECONOMY

In this section the continuities in NI’s pattern of industrial development are discussed. It is demonstrated that while organisational restructurings have been common, it has proven much more difficult to promote a model of industrial development consistent with promoting high productivity and structural change. Furthermore, in contrast to any simple ‘crowding out’ explanations of persistent productivity weaknesses, the evidence presented indicates that the enduring high dependency of the regional economy on fiscal transfers was more a consequence than a cause of NI’s supply-side problems. Government deficits were, for instance, only around 7% as a share of regional output during the mid-1960s, but low productivity and high unemployment had already ossified into persistent weaknesses.

The survey papers by Ó Gráda (Citation1995, Citation1997), O’Rourke (Citation2017) and Ó Gráda and O’Rourke (Citation2022), covering long-run economic performance on the island of Ireland, are of particular relevance in terms of developing a place-based interpretation. O’Rourke demonstrated that in the 75 years after 1926, independent Ireland grew exactly in line with its initial income level. Furthermore, given data availability issues, when it is possible to compare with Wales and NI between 1954 and 1973, Ireland’s growth performance was very similar. All three economies perform less well than initial income levels would have indicated. O’Rourke suggested that all three economies (only two of which remained in the UK) may have suffered from an excessive reliance on the sluggish economy of Great Britain (GB) (O’Rourke, Citation2017). Ó Gráda and O’Rourke (Citation2022) extend the discussion into a more formal comparative analysis of the two Irelands since partition. They note that problems in the effective economic restructuring of the NI economy have been long-standing. Indeed, their analysis indicates that such problems can be traced back to the 1920s and 1930s (Ó Gráda & O’Rourke, Citation2022). In place-based terms, it is important to note that Ó Gráda and O’Rourke agree with the assessment of other economic historians in noting that political elites during devolution between the 1920s and the 1970s tended to assist the politically well-connected but ailing staples with loan guarantees and grants rather than promote new entrants (Johnson, Citation1985; Brownlow, Citation2007; Brownlow & Geary, Citation2005; Jordan, Citation2020). Furthermore, Ó Gráda and O’Rourke concede that while NI suffered deindustrialisation like other UK regions during the 1970s, its painful experience of industrial decline was compounded by the Troubles.Footnote1 Political instability (a region-specific issue) ensured that inflows of investment were inadequate to offset industrial decline (a much wider economic problem) (Ó Gráda & O’Rourke, Citation2022).

Ó Gráda and O’Rourke note that when inward investment was promoted in the period 1945–2000 it was often in product categories that were either coming to the end of their product cycle or (as in the case of DeLoreanFootnote2), ‘a product whose cycle never really began’ (Ó Gráda & O’Rourke, Citation2022, p. 362). Ó Gráda and O’Rourke observe that we might ascribe the quantitative and qualitative failures of inward investment to a consistent run of bad luck. An alternative interpretation, more in keeping with place-based interpretations, is that institutional factors and recurrent issues with rent-seeking are traceable back to the way regional economic policy operated first under devolution (c.1921–72), then under Direct Rule and then since the late 1990s under devolution (Johnson, Citation1985). In this sense, Ó Gráda and O’Rourke suggest that both Irelands have been locked into underdevelopment traps, which the south struggled to break free from until the 1990s, whilst NI still struggles to emerge from despite the economic improvements of recent decades.

There have been three main interpretations of the challenges facing the contemporary NI economy. First, what can be described as a ‘silver bullet’ or ‘game changer’ interpretation that looks to imitating particular parts of the Irish Celtic Tiger model (Dooley & Hodson, Citation2014). Advocates of this interpretation argue that NI needs a lower corporation tax rate than the rest of the UK in order to invigorate the private sector (and inward investment in particular). It is asserted that the stimulus created by lower corporate taxation would rebalance the economy away from what is presented as an excessive reliance on the public sector (Economic Advisory Group, Citation2011; PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), Citation2011). As has been noted elsewhere, such market focused interpretations ignore the race to the bottom that such a ‘game changing’ approach might encourage within the UK as a whole and moreover fail to acknowledge that reductions in public expenditure might deflate rather than reinvigorate the region’s economy (Brownlow, Citation2016; Budd, Citation2016; Birnie & Brownlow, Citation2017).

Second, a more skills-based interpretation, associated with FitzGerald and Morgenroth, is to present the productivity failings of the NI economy as being a failure to invest in capital of both the physical and human form (FitzGerald & Morgenroth, Citation2019). In this regard, the interpretation they present is a ‘people-based’ one as deficiencies in education are viewed as the explanation for low productivity.

A third interpretation is associated with Birnie (Birnie & Hitchens, Citation1999; Birnie & Brownlow, Citation2017; Brownlow & Birnie, Citation2018; Birnie et al., Citation2019). The kind of underdevelopment trap discussed within the place-based approach, and within the long-run historical account of Ó Gráda and O’Rourke finds echoes in Birnie’s discussions concerning productivity (or indeed competitiveness) gaps. In this interpretation, the uniqueness of NI (both before and after 1998) is an important element in explaining the persistence of weak economic performance. Birnie’s critique of the ‘game changer’ argument suggests that market forces alone via lower corporate taxes will not necessarily attract a sufficient quantity or quality of inward investment (Birnie & Brownlow, Citation2017). Moreover, Birnie’s analysis indicates that the problems of the economy are due to an excessively weak private sector rather than a bloated public sector. Furthermore, the evidence points to public sector growth as a response to a region-specific legacy of industrial decline and political unrest (Brownlow & Birnie, Citation2018).

illustrates that while the political settlement in 1998 undoubtedly has contributed to greater political stability under which investment has created opportunities for better performance. Yet equally over the period 2000–18, gross domestic product (GDP) per head growth in NI lagged the rest of UK and the ROI (HM Treasury, Citation2011). Although a rising labour force participation rate made for a higher contribution than the UK average. However, the relative underperformance of NI’s GDP growth was driven by the exceptionally sluggish productivity growth between 2000 and 2018 (FitzGerald & Morgenroth, Citation2019). As should be clear, the longstanding productivity gap was thus not closed by political settlement, that has arisen again in the context of Brexit and the NIP and the continuing standoff between the political parties of NI over the reopening of the NI Assembly and Executive (Jordan & Turner, Citation2021). These issues form a backcloth to the analysis of the next section.

Table 1. Decomposition of growth in gross domestic product (GDP) per head, 2000–18.

4. ECONOMICS OF THE NORTHERN IRELAND PROTOCOL: BREXIT AS A PLACE-BASED SHOCK?

Brexit, however it turns out, has important political and economic implications for the UK as a whole (Brooks et al., Citation2020). Such implications reflect the fact that economic and political (dis)integration represent interconnected processes (Machlup, Citation1970; Brownlow & Budd, Citation2019). To date, it is estimated that the long-term decline in GDP as a result of Brexit is between 4% and 6% over 15 years and a current loss of international trade around 15% (Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), Citation2022; Bank of England, Citation2022). Furthermore, disruption to supply chains and certification agreements will cause further problems, manifested in the trade friction between GB and NI due to the conditions of the NIP. NI’s regional economic fortunes are connected to its foreign direct investment (FDI) prospects and these in turn are tied to how Brexit develops (Teague, Citation2021).

The theory of economic integration remains far more worked out than that of disintegration however, indeed to a greater or lesser extent it might be a case of practice running ahead of theory where taking ‘off the shelf’ textbook solutions may not be available (Sampson, Citation2017; Morgenroth, Citation2017; Brownlow & Budd, Citation2019). However, when such a model of economic disintegration finally develops (the details of which are well beyond the scope of this paper), it will be one that is bound to highlight again the importance of path dependence, complexity and place-based factors rather than observe any smooth convergence.

Moreover, such a model needs to recognize the role that transactions costs play in real world. For example, one lesson of the Brexit process from the Northern Irish context has been the important role of all-Ireland supply chains in agrifood. Roughly, 40% of north–south trade involves agrifood products (Teague, Citation2021). The integration of the milk and dairy product and complexity of the supply chain is particularly profound, and products move in both directions. Moreover, the agrifood sector as a whole is a key function in global value chain (GVC) terms that is another distinctive feature (Budd, Citation2019; Brownlow & Budd, Citation2019). In addition to the sizable employment and gross value added (GVA) contributions of agrifood on both sides of the border, there is also a high degree of economic cooperation creating spillovers in terms of demand for physical and financial capital, in addition to research and development (R&D) and sustainable practices (Budd, Citation2019; Brownlow & Budd, Citation2019). Hence, any damage through Brexit has profound negative implications for both this sector and the cross-border ‘place’ that it serves.

The issues surrounding Brexit as it relates to NI are not merely issues of the costs of reversing economic integration, the issues involve deeply political concerns including identity, sovereignty, legitimacy and the role of European economic integration in promoting peace (O’Rourke, Citation2018; Gudgin, Citation2019; McBride, Citation2019; Teague, Citation2021; Shirlow et al., Citation2021). NI barely got a mention in the Brexit campaign of 2016, and nor did Ireland more generally, but its relevance has become much clearer since the Brexit Referendum (D’Arcy & Ruane, Citation2018; O’Rourke, Citation2018; McCall, Citation2021). Indeed, it is the fact that the border between NI and its neighbour serves also as the UK’s only land frontier with the EU, combined with the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement (GFA), which has influenced the form that Brexit has taken (Teague, Citation2021).

The NIP has arisen out of a political desire to prioritise keeping the border open between the two Irelands. This emphasis on north–south rather than east–west relationships has political as well as economic ramifications. At the political level, it shattered any smooth EU withdrawal (Teague, Citation2021). Furthermore, by placing a border in the Irish Sea it has created tensions. In terms of place-based economics Brexit, by potentially making any land border into a frontier between the EU internal market and a third country, turned the negotiations into ones more focused on border custom and regulatory checks, whose compliance costs are large. NI will continue to be part of the UK’s customs territory, which means that the region will be included in any free trade agreement that the UK government signs with a third country. At the same time, cross-border trade on the island of Ireland will be governed by EU customs rules, which ensures that no customs checks or controls at the border (Teague, Citation2021).

Yet the implication of aligning NI with EU customs rules is to ensure that while it remains part of UK customs territory, goods moving from GB to NI will be subject to tariffs if they are ‘at risk’ of moving into the EU. Goods that are not at risk of entering the Single European Market (SEM) need not be subject to customs duties (the issue of distinguishing between goods ‘at risk’ or not will lead to further complexityFootnote3). A further result is to produce what has been described as a sea border as parts of UK internal trade will be made subject to checks and controls in order to comply with these rulebooks. In addition, regulatory alignment for NI – in areas such as technical standards, environmental regulations and state aid – needs to be maintained with the SEM (Teague, Citation2021).

However, while the NIP may offer opportunities it is not without challenges too, the hybridization potential of the NIP – that is, the fact it allows unfettered access to Britain while still retaining SEM benefits – for good or ill is a very real one. While agrifood has a very important north–south dimension discussed earlier, overall trade linkages within the internal UK market (or east–west) have been much greater than on the island of Ireland (north–south) (Central Statistical Office (CSO), Citation2021). Hence, supply chain readjustment (or what could be termed import substitution) will not be costless. Another way costs may be manifested could be in a reduction in the variety of products available to consumers.

Into this landscape the complexities associated with NI remaining within the SEM unlike the rest of the UK, when combined with monitoring issues, gives rise to smuggling risks.Footnote4 There was a conundrum involved in any model of Brexit as a hard land border would have possible implications for political stability, while also creating issues of efficiency (Hayward, Citation2019). The NIP can be viewed as an attempt to solve that conundrum but there are negative externalities that arise that tend to reinforce the path dependent nature of many activities in NI.

With the creation of the SEM in 1992 import duties on goods were swept away, but excise duties on fuel, tobacco and alcohol remained. In political terms, the removal of customs controls had favourable symbolic as well as commercial effects (Morgenroth, Citation2019). Economically the SEM promoted the integration in certain sectors. By 2018, 60% of cross-border trade was concentrated in agrifood, chemicals and building materials. Within agrifood the integration of supply chains became particularly pronounced with half of all NI produced flour going to Ireland and with spillovers in terms of demand for machinery, services, R&D and sustainability best practice (IBEC and CBI, Citation2018, Budd, Citation2019). The fact that NI’s legal status under the NIP ensures that it operates differently from the rest of the UK is just another reminder of its place-based uniqueness, one that may contribute to an increase in transactions costs of regulating the economy. In effect, the NIP could be considered the only industrial policy operating at present, whose context is an important consideration in discussions of approaches to industrial strategies in NI.Footnote5 This is discussed more fully in the next section.

5. THE NORTHERN IRELAND ECONOMY IN THE LIGHT OF PLACE-BASED APPROACHES TO INDUSTRIAL STRATEGIES

So far, we have considered both the general issues that arise from the connections between RIS and SM in terms of place-based approaches as well as the specific issues of how Brexit and the NIP act as a place-based ‘shock’ uneven in its locational and sectoral impacts for the NI economy. Even if we have specific objections with the details of either CRA or S3 and the application of I4.0, there is little doubt that thinking about the NI economy in a place-based way (one more aligned with complexity thinking) makes more sense than the equilibrium alternative. Any shock (positive or negative) to firms as a result of Brexit will impact the NI economy and that shock in turn will be recursive.

Just as modern place-based approaches suggest that regions should use existing areas of sector strength to create and capture value, so the NIP complicates matters for while on the one hand it may make for NI becoming a greater FDI hub, so on the other hand it poses challenges to efficient supply chains. What is clear is that any possibility of developing economic strategy in NI cannot be sectorally neutral, path dependency has already had enormous impacts on the shape of the economy. In terms of developing I4.0, it suggests that the relationship between SM and RIS practices will remain vital. In a range of high value-added sectors such as Fintech, tradable advanced business services, cybersecurity and film and television there has been success already, but there is a huge gap between these areas and agrifood, so a challenge remains that the NI economy has a few unconnected centres of excellence in a regional economy long blighted by low skills, wages and productivity (NISRA, Citation2022).

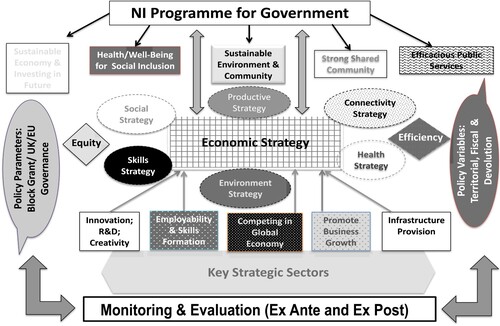

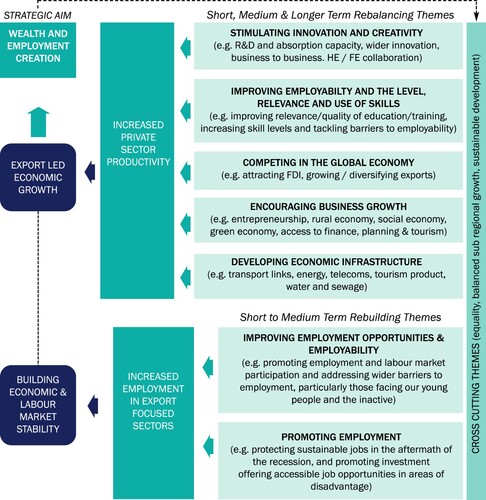

This trajectory of industrial policy over the decades appears to support Aiginger and Rodrik’s contention that ‘societal goals should be paramount, moving beyond the correction of market failures‘(Aiginger & Rodrik, Citation2020, p. 202). This contention also supports the development and application of I4.0 and its supporting elements. I4.0 does encompass GPTs that can transform industrial and innovation policy. In the context of NI, industrial policy is implicit in its 2012 economic strategy and explicit in Economy2030: A Draft Industrial Strategy for Northern Ireland (Department for the Economy, Citation2017a). The 2012 Economic Strategy Priorities for Sustainable Growth and Prosperity sets out the economic vision as for the NI economy in 2030 as ‘An economy characterised by a sustainable and growing private sector, where a greater number of firms compete in global markets and there is growing employment and prosperity for all’ (NI Executive, Citation2012, p. 9). The key priorities are rebalancing; rebuilding; and prioritisation of the NI Economy. Several themes that feed into the strategic framework displayed in .

Figure 1. Components of the Northern Ireland economic strategy in the context of the programme for government.

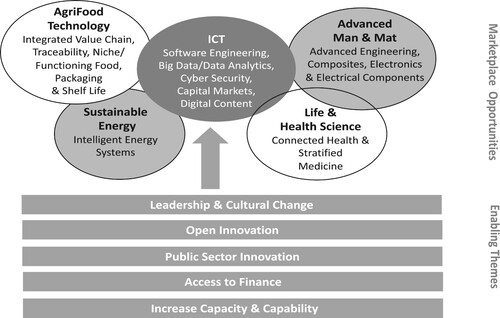

The priorities of the 2012 Economic Strategy were expanded under Economy 2030, which includes 10 related indicators.Footnote6 Again, such indicators seek to address weaknesses in the NI Economy to date rather that providing a rationale for policy levers to exploit the transformative potential of I4.0 and its S3 and CRA elements for which certain sectors are viewed as the drivers of industrial strategy and policy (Gorecki, Citation1997). The governance of these sectors is organised by the MATRIX Panel, an industry-led panel advising government and informing academia and industry on the commercial exploitation of R&D and science and technology.Footnote7 The MATRIX sectors are displayed in . Prioritisation in general is based upon supporting and stimulating the MATRIX sectors that underpin the strategic framework for growth objectives. In a sense, I4.0 is implicit in the MATRIX sectors, with the exception of agrifood, but there is no explicit mention or analysis that would strengthen the implementation of industrial strategy and policy. This appears perverse given the NI Executive’s S3 priorities that are set out in .

Figure 2. Strategic framework for economic growth.

Source: Northern Ireland Executive (Citation2012).

Table 2. MATRIX panel priorities.

The logic of the industrial strategy consultation Economy 2030 rests on learning from global best practice by comparing the competitiveness of NI with similar small economies. In terms of the development of industrial policy, competitiveness has been shown to be a part of the current industrial policy, rooted in evolutionary economics (Peneder, Citation2017). But the issue of the conceptual weakness of competitiveness,Footnote8 notwithstanding, NI is not an open national economy, so the comparison is moot. The other fundamental weakness of Economy2030 is the lack of any analysis of the impact of Brexit: surprising given the proposed strategy consists of the following five pillars (Department for the Economy, Citation2017b, p. 30):

• Pillar 1: Accelerating innovation and research.

• Pillar 2: Enhancing education, skills and employability.

• Pillar 3: Driving inclusive, sustainable growth.

• Pillar 4: Succeeding in global markets.

• Pillar 5: Building the best economic infrastructure.

The five pillars and the MATRIX priorities appear at first sight to fulfil some of the criteria of S3 and CRA capabilities by applying I.40. As pointed out above, the weakness of applying these approaches is the stress on scientific and technological aspects of innovation, as described above In 2014, the NI Executive published Innovation Strategy 2012–2025, that is linked to the 2012 economic strategy, which sets out S3 priorities for NI that are displayed in (NI Executive, Citation2014). As can be seen, these priorities are closely aligned to most of the MATRIX sectors but there is no mention of the capacities needed to develop I.4.0 more comprehensively within place-based approaches.

Figure 3. Smart Specialisation priorities for Northern Ireland.

Source: Northern Ireland Executive (Citation2014).

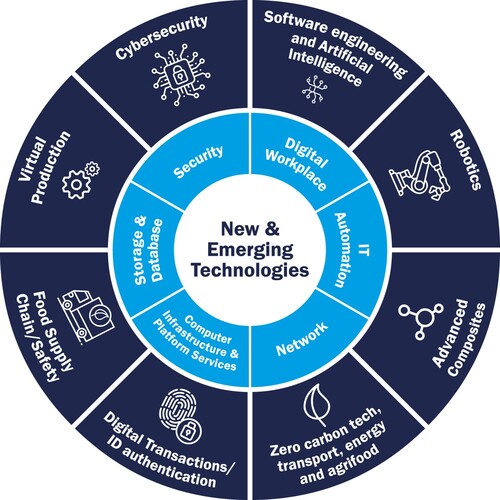

In 2021, the Department for the Economy produced its vision for the NI Economy, A 10X Economy, based upon a set of enabling technologies from which, S3 and I.4.0 activities would be promoted in order to achieve CRA outcomes (Department for the Economy, Citation2021). These are set out in but clearly relate to the MATRIX sectors on which current industrial strategy is built. The fundamental issue with this report is that it further shifts the emphasis towards SM, without due consideration to operational effectiveness of achieving industrial policy objectives (MacFlynn, Citation2017). This shift in emphasis is summarised in the 10 guiding principles of A 10X Economy.Footnote9

Figure 4. Enabling technologies for Northern Ireland.

Source: Department for the Economy (Citation2021).

However worthy, there are no means in the 10X vision to address the continuing path dependent weakness of the NI economy. The continuing stress on high-value-added activities in successive economic and industrial strategies enabled by I4.0 technologies, based on very limited analysis, appears to be emblematic of the institutional path dependency in managing economic policy. What is interesting is that Brexit remained the ‘elephant in the room’ for all three strategies until the creation of the NIP that now appears to dominate industrial policy, at least in the short term.

Although, ROI–NI trade flows are increasing, they only represent 2% and 4% of the former’s exports and imports respectively. Since 2020, comparative figures for GB–NI trade no longer exist as the Northern Ireland Statistics Agency (NISRA) no longer collects such data. Notwithstanding the anecdotal evidence of the disruption to GB–NI supply chains, trade flows still constitute about three times that of north–south volumes.

A recent Regional Studies paper focuses on two channels of trade friction caused by the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) and NIP: tariff (TB) and non-tariff barriers (NTB). Using a computable general equilibrium model for Northern Ireland (NIGCE), the authors estimate the macroeconomic and trade implication of the NTBs and potential TBs (Duparc-Portier & Figus, Citation2021). The critiques of GCE models, notwithstanding (e.g., Hazledine, Citation1992), three central conclusions are drawn. First, trade in NI under the TCA will be less detrimental than under a No-Deal Brexit outcome. Second, due to the larger trade barriers for GB goods imported into NI, NI will substitute rest of the world (incl. EU) intermediate inputs for GB inputs. Third, the expectation is that NTBs between GB and NI will account for around 80% of the impact on GDP, consumption and employment as well as other macroeconomic variables.

The analysis of various scenarios leads to the conclusion that the NIP will not deliver the ‘best of both worlds’ scenario and that the NI economy does not improve under any other one than a no-Brexit one (Duparc-Portier & Figus, Citation2021). The north–south transactions enabled by the NIP may ultimately be advantageous in creating and sustaining the appropriate regulatory mechanisms to support I.40 and its S3 and CRA capabilities. This conclusion, however, is too early to draw given the post-Brexit uncertainty at the time of writing.

6. POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The analysis within this paper has involved the application of a range of economic concepts (e.g., transactions costs, path dependence) to the issue of place-based strategies to what can be described as a lagging region, which may have relevance elsewhere. Throughout this paper, we have suggested that as a general observation, place-based rather than spatially blind approaches are more likely to reverse underdevelopment traps. Long-standing uneven regional economic geographies of the kind described by McCann (Citation2019) for example, are unlikely to find a correction via price-based adjustments alone. Likewise, the preceding analysis suggests that ‘crowding out’ may not be the best way to conceptualise the role that public sector interventions can play in regional economies. This analysis rests on an understanding of both economic geography and history as long-standing regional economic underperformance may reflect underdevelopment traps that are a product of specific (place-based) economic histories.

Four policy observations are set out in brief in the remainder of this section as they relate to the NI case. First, the bulk of previous attempts at correcting the region’s economic underperformance have assumed that a (factor) price-based approach would be sufficient to the task. Circumstance, not least the existence of political instability has however tended to reduce the range of options in the area of industrial assistance. For instance, grants became more generous in response to political unrest in part as a form of risk premium. Yet increasing the inducement gap – the difference between NI and GB subsidies – tended to encourage opportunistic entrepreneurs to be attracted to NI. Such projects usually failed quickly and did little to remedy the region’s economic underperformance (Brownlow, Citation2020).

Second, NI’s economy has shared in the regional problems that have beset the UK economy as a whole; in addition, other problems either represent a magnification of such difficulties or relate to factors unique to NI (Crafts, Citation1995; Gardiner et al., Citation2013; McCann, Citation2019). Issues surrounding the NIP and the current imbroglio concerning the Assembly and Executive for instance represent problems unique to NI. These current political difficulties have reinforced a coercive kind of institutional isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983) in the form of departmental government responsibilities being distributed to different political parties: reinforcing silo approaches industrial policy that undermine a place-based emphasis. The combination of these different types of problems have made it difficult for policymakers to provide a correct diagnosis even before they try to design remedies. In defence of the policymakers, even the best-designed place-based policies would run into challenges of identifying the exact source of the problem. For example, addressing NI’s productivity weakness requires us to decompose the source of the productivity problems into those areas shared with the rest of the UK, those that represent magnifications and those that were unique to NI. Any future industrial policymaking agencies will have to put more effort into diagnosing the sources of the region’s specific economic weaknesses.

Third, in the case of NI, the recurrent problem of opportunistic behaviour has bedevilled the formulation and implementation of effective regional industrial policy. It is therefore crucial that any future place-based industrial strategy ensures that the underlying institutional machinery prevents rent-seeking or regulatory capture. Objective considerations of efficiency and equity rather than considerations of political and economic power need to underpin future industrial policy and its institutional processes.

Fourth and specifically linked to the NIP, there remains a range of uncertainties (political and economic) about the net effects that it will bring. However, the good news is that economic integration on the island to some extent should simulate producers on both sides of the border. The bigger concern is that clear winners from such north–south integration, such as agrifood, are economically unconnected from the high value-added sectors such as Fintech, tradable advanced business services, cybersecurity, film and television and consulting services; sectors that are more likely to promote positive I4.0, S3 and ultimately CRA outcomes.

7. CONCLUSIONS

How are we to interpret the relevance of place-based approaches to revitalising the NI economy? As the material presented above indicates, we need to be careful about not confusing the organisational structures of industrial policy formulation and implementation with the actual policy content. As noted throughout this paper, path dependence has tended to reduce the range of options. Furthermore, the combination of UK wide as well as more NI-based problems has made it difficult to extricate the region from any underdevelopment trap.

Into this complicated situation, the development of S3 and CRA in the context of I4.0 as being central to RIS and associated industrial strategies and policies is a challenge. The emergence of cyber security, Fintech, tradeable advanced business services and parts of the creative industries in NI do point towards some grounds for optimism. Moreover, the successes of these industries can either be interpreted as a consequence of wise policy measures or as something of a puzzle. While it might be convenient to see the emergence of these new industries as the economy finally moving towards a better path in which I4.0, S3 and CRA become more developed, the current path dependent nature of the NI economy may constrain potential beneficial outcomes. Furthermore, as we have noted in the previous section, if new industries have emerged in the province, without being reliant on an imperfect set of governance arrangements, then it suggests that ‘leapfrogging’ might be possible.

However, the analysis in this paper requires some caveats before we point to future work. The very fact that we have focused on a place-based (region specific) analysis of the NI economy limits the generality of some of the policy prescriptions. Uncertainties concerning the NIP for instance necessarily involves issues unique to NI. There are enough points made in this paper however, which suggest that future research might involve exploring more generally how place-based and space-neutral approaches diverge as well as using the distinction to explore the NI case in more detail. For example, whether the NIP and subsequent changes in the relationship with the EU (especially the ROI) can contribute to ‘leapfrogging’ is a question for future research. Comparative implications of the analysis set out in this paper may also be relevant for explaining the relative performance of different UK regions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank David Bailey and Phil Tomlinson, and two anonymous referees.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. The Troubles, as commonly known, was a violent sectarian conflict in NI between Unionists and Nationalists from the late 1960s to the 1990s, concerning its relationship with the UK and the Republic of Ireland (ROI).

2. The US car company DeLorean set up a facility in West Belfast in 1979 to produce a sports car with the financial assistance of the British government. Despite its promise, production ceased in 1982 due to a combination of factors with the British government refusing further aid.

3. The creation in 1923 of a customs frontier on the island of Ireland encouraged ‘tariff jumping’ industrial enterprises in sectors such as tobacco in both directions (Barry et al., Citation2020, p. 63). This tariff jumping – along with the overlapping export platform rationale – has continued to shape inward investment on the island. At the very least, the experience of tariff jumping may provide a template for the geography of future industrial development on the island. The extent to which NI may be able to leverage its unique legal position, while avoiding any future trade costs, will determine the extent to which it will benefit.

4. Opportunities for smuggling exist where prices (e.g., differences in duty) or product availability (e.g., prohibitions) differ between two sides of a border and in which enforcement is weak. The economic geography and history of the island of Ireland is once in which smuggling has been a recurrent issue (McCall, Citation2019; Northern Ireland Affairs Committee, Citation2002; Young, Citation2022).

5. At the time of writing, the UK government and the European Commission jointly announced a new deal over the NIP concerning a reduction in trade friction. The political implications of its implementation are currently not worked through, but the continuing hybridity of the NI Economy appears to be sustained.

6. These include conventional economic strategy measures concerning business formation; R&D, skills, employability inclusive economic growth, etc. (Department for the Economy, Citation2017b, p. 59).

8. See Budd and Hirmis (Citation2004) for analysis of the canard of competitiveness in a regional setting.

REFERENCES

- Aiginger, K., & Rodrik, D. (2020). Rebirth of industrial policy and an agenda for the twenty-first century. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 20(2), 189–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-019-00322-3

- Arthur, W. B. (2021). Foundations of complexity economics. Nature Reviews Physics, 3(2), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-020-00273-3

- Bailey, D., Hildreth, P., & de Propris, L. (2015). Mind the gap! what might a place-based industrial and regional policy look like? In D. Bailey, K. Cowling, & P. Tomlinson (Eds.), New perspectives on industrial policy for a modern policy (pp. 287–308). Oxford University Press.

- Bailey, D., Pitelis, C. N., & Tomlinson, P. R. (2018). A place-based developmental regional industrial strategy for sustainable capture of co-created value. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 42(6), 1521–1542. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bey019

- Bailey, D., Pitelis, C. N., & Tomlinson, P. R. (2020). Strategic management and regional industrial strategy: Cross-fertilization to mutual advantage. Regional Studies, 54(5), 647–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1619927

- Bank of England. (2022). Monetary policy report, May 2022.

- Barca, F. (2011). Alternative approaches to development policy: Intersections and sivergences. In OECD regional outlook 2011: Building resilient regions for stronger economies. OECD Publ. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264120983-17-en

- Barca, F., McCann, P., & Rodriguez-Pose, A. (2012). The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. Journal of Regional Science, 52(1), 134–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2011.00756.x

- Barry, F., Sun, X., & Hogan, B. F. (2020). Brexit damage limitation: Tariff-jumping FDI and the Irish agri-food sector. Irish Journal of Management, 39(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.2478/ijm-2010-0007

- Barzotto, M., Corrandinic, C. F., Labory, F., & Tomlinson, P. R. 2020. Smart specialisation, Industry 4.0 and lagging regions: Some directions for policy. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 7(1), 318–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2020.1803124

- Beer, A., McKenzie, F., Blažek, J., Sotarauta, M., & Ayres, S. (2020). Every place matter: Towards effective place-based policy, regional studies policy impact books. Regional Studies Association.

- Birnie, E., & Brownlow, G. (2017). Should the fiscal powers of the Northern Ireland assembly be enhanced? Regional Studies, 51(9), 1429–1439. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1206655

- Birnie, E., & Hitchens, D. (1999). Northern Ireland economy: Performance, prospects, policy. Ashgate.

- Birnie, E., Johnston, R., Heery, L., & Ramsay, E. (2019). A critical review of competitiveness measurement in Northern Ireland. Regional Studies, 53(10), 1494–1504. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1569757

- Boschma, R. (2014). Constructing regional advantage and smart specialisation: Comparison of the two European policy concepts. Scienze Regionale, 39(1), 61–74. 10.3280/SCRE2014-001004

- Brooks, T., Scott, L., Spillane, J. P., & Hayward, K. (2020). Irish construction costs cross border trade and Brexit: Practitioner perceptions on periphery of Europe. Construction Management and Economics, 38(1), 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2019.1679382

- Brownlow, G. (2007). The causes and consequences of rent-seeking in Northern Ireland, 1945–1972. Economic History Review, 60(1), 70–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2006.00357.x

- Brownlow, G. (2016). Soft budget constraints and regional industrial policy: Reinterpreting the rise and fall of DeLorean. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 40(6), 1497–1515. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bev077

- Brownlow, G. (2020). Industrial policy in Northern Ireland: Past, present and future. Economic and Social Review, 52(3), 407–424.

- Brownlow, G., & Birnie, E. (2018). Rebalancing and regional economic performance: Northern Ireland in a Nordic mirror. Economic Affairs, 38(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecaf.12267

- Brownlow, G., & Budd, L. (2019). Sense making of Brexit for economic citizenship in Northern Ireland. Contemporary Social Science, 14(2), 294–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2019.1585564

- Brownlow, G., & Geary, F. (2005). Puzzles in the economic institutions of capitalism: Production coordination, contracting and work organisation in the Irish linen trade, 1750–1850. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 29(4), 559–576. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bei010

- Budd, L. (2016). Economic challenges and opportunities of devolved corporate taxation in Northern Ireland in. In D. Bailey, & L. Budd (Eds.), Devolution and the UK economy (pp. 95–115). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Budd, L. (2019). Irish cows don’t respect borders. In J. Mair, S. McCabe, N. Fowler, & L. Budd (Eds.), Brexit and Northern Ireland: Bordering on confusion (pp. 171–179). Bite-Sized Books.

- Budd, L., & Hirmis, A. (2004). Conceptual framework for regional competitiveness. Regional Studies, 38(9), 1015–1028. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340042000292610

- Central Statistical Office (CSO). (2021). External trade. CSO.

- Crafts, N. (1995). The golden Age of economic growth in postwar Europe: Why did Northern Ireland miss out? Irish Economic and Social History, 22(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/033248939502200101

- D’Arcy, M., & Ruane, F. (2018). The Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, the island of Ireland economy and Brexit. The British Academy and Royal Irish Academy.

- De Propris, L., & Bailey, D. (2020). Disruptive Industry 4.0+ key concepts. In L. De Propris, & D. Bailey (Eds.), Industry 4.0 and regional transformations (pp. 1–23). Routledge.

- Department for the Economy. (2017a). A consultation on an industrial strategy for Northern Ireland.

- Department for the Economy. (2017b). Economy 2030: A consultation on an industrial strategy for Northern Ireland. https://www.economy-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/consultations/economy/industrial-strategy-ni-consultation-document.pdf

- Department for the Economy. (2021). A 10X economy.

- Department of Business, Enterprise and Innovation. (2019). Ireland’s Industry 4.0 strategy 2020–2025 supporting the digital transformation of the manufacturing sector and its supply chain. Government of Ireland.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Dooley, J. F., & Hodson, A. (2014). Ireland’s RIS3 strategy. Department of Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation.

- Duparc-Portier, G., & Figus, G. (2021). The impact of the new Northern Ireland Protocol: Can northern enjoy the best of both worlds? Regional Studies, 56(8), 1404–1417. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1994547

- Economic Advisory Group. (2011). The impact of reducing corporation tax on the Northern Ireland economy.

- European Commission. (2018). Capitalising on the benefits of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Publications Office of the European Commission.

- Eurostat. (2018). Real growth rate of regional gross value added (GVA) at basic prices. Eurostat.

- FitzGerald, J., & Morgenroth, E. (2019). The Northern Ireland economy: Problems and prospects (Economic Papers No. 0619). Trinity College.

- Foray, D. (2015). Smart specialisation: Opportunities and challenges for regional innovation policy. Routledge.

- Gardiner, B., Martin, R., & Tyler, P. (2013). Spatially unbalanced growth in the British economy. Journal of Economic Geography, 13(6), 889–928. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbt003

- Gorecki, P. (1997). Industrial policy in Northern Ireland: The case for radical reform. Manchester Statistical Society.

- Gudgin, G. (2019). Border issues are surmountable. In J. Mair, S. McCabe, N. Fowler, & L. Budd (Eds.), Brexit and Northern Ireland: Bordering on confusion? (pp. 104–110). Bite-Sized Books.

- Hayward, K. (2019). Johnson’s unworkable Brexit plan won’t solve the Northern Ireland border issue. Belfast Telegraph, October 3.

- Hazledine, T. (1992). A critique of computable general equilibrium models for trade policy analysis, working papers 51131. International Agricultural Trade Research Consortium.

- HM Treasury. (2011). Rebalancing the Northern Ireland economy. HM Treasury.

- IBEC and CBI. (2018). Business on a connected island. IBEC & CBI Northern Ireland.

- Johnson, D. S. (1985). The Northern Ireland economy, 1914–39. In L. Kennedy, & P. Ollerenshaw (Eds.), An economic history of ulster, 1820–1940 (pp. 184–240). Manchester University Press.

- Jordan, D. (2020). The economics of devolution: Evidence from Northern Ireland 1920–1972 [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Queen’s University Belfast.

- Jordan, D. P., & Turner, J. (2021). Northern Ireland’s productivity challenges: Exploring the issues (Productivity Insights Paper No. 004). The Productivity Institute.

- MacFlynn, P. (2017). Industrial policy in Northern Ireland: A regional approach (Working Paper WP2017/No. 42). Nevin Economic Research Institute (NERI).

- Machlup, F. (1970). Homo oeconomicus and his class mates. In M. Natanson (Ed.), Phenomenology and social reality: Essays in memory of Alfred Schutz (pp. 122–139). Springer Nature.

- McBride, I. (2019). How the border moved from a symbol of antagonism to an irrelevance. In J. Mair, S. McCabe, N. Fowler, & L. Budd (Eds.), Brexit and Northern Ireland: Bordering on confusion? (pp. 22–30). Bite-Sized Books.

- McCall, C. (2019). Smuggling in the Irish borderlands – And why it could get worse after Brexit. The Conversation, February 11. https://theconversation.com/smuggling-in-the-irish-borderlands-and-why-it-could-get-worse-after-brexit-111153

- McCall, C. (2021). Border Ireland from partition to Brexit. Routledge.

- McCann, P. (2019). Perceptions of regional inequality and the geography of discontent: Insights from the UK. Regional Studies, 54(2), 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1619928

- Morgenroth, E. (2017). Examining consequences for grade: Integration and disintegration effects. In D. Bailey, & L. Budd (Eds.), The political economy of Brexit (pp. 17–34). Agenda.

- Morgenroth, E. (2019). Brexit and the all-island economy. In J. Mair, & S. McCabe (Eds.), Brexit and Northern Ireland bordering on confusion? (pp. 149–156). Bite-Sized books.

- Northern Ireland Affairs Committee. (2002). Minutes of evidence taken before the Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Wednesday 16 January 2002 – Memorandum submitted by Police Service Northern Ireland. House of Commons Library Publ. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200102/cmselect/cmniaf/978/2011602.htm

- Northern Ireland Executive. (2012). Economic strategy: Priorities for sustainable growth and prosperity. Northern Ireland Executive.

- Northern Ireland Executive. (2014). Innovate NI: Innovation strategy for Northern Ireland 2014–2025. Northern Ireland Executive.

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Authority. (2022). Economic overview. NISRA. https://datavis.nisra.gov.uk/economy-and-labour-market/economic-overview.html

- O’Rourke, K. (2018). A short history of Brexit from Brentry to backstop. Pelican.

- Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). (2022 March). Economic and fiscal outlook. OBR.

- O’Rourke, K. H. (2017). Independent Ireland in comparative perspective. Irish Economic and Social History, 44(1), 19–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0332489317735410

- Ó Gráda, C. (1995). Ireland 1780–1939: A new economic history. Oxford University Press.

- Ó Gráda, C. (1997). A rocky road: The Irish economy since the 1920s. Manchester University Press.

- Ó Gráda, C., & O’Rourke, K. H. (2022). The Irish economy during the century after partition. Economic History Review, 75(2), 336–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.13106

- Peneder, P. (2017). Competitiveness and industrial policy: From rationalities of failure towards the ability to evolve. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 41(3), 829–858. 10.1093/cje/bew025

- Porter, M. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. Macmillan.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). (2011). Corporation tax: Game changer or game over? Government Futures, PwC.

- Quigley, G. (1976). Economic and industrial strategy for Northern Ireland, Report by Review Group. Her Majesty’s Stationary Office (HMSO).

- Sampson, T. (2017). Brexit: The economics of international disintegration. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(4), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.4.163

- Shirlow, P., D’Arcy, M., Grundle, A., Kearney, J., & Murtagh, B. (2021). The Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol: Responding to tensions or enacting opportunity? Institute of Irish Studies.

- Teague, P. (2021). Brexit and the political economy of Ireland: Creating a new economic settlement. Routledge.

- Young, D. (2022). Smugglers trying to move counterfeit goods into single market via NI, says EU. Belfast Telegraph, June 15. https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/smugglers-trying-to-move-counterfeit-goods-into-single-market-via-ni-says-eu-41755807.html