ABSTRACT

Understood in some conceptual analysis as a pillar of territorial cohesion and due to its critical role in promoting territorial integration, territorial cooperation is often presented as one of the major positive achievements of European Union (EU) Cohesion Policy. In this context, this article proposes a conceptual framework to assess the contribution of the European Territorial Cooperation process, including the beyond-funding support from the Border Focal Point, to the ultimate goal of EU Cohesion Policy: territorial cohesion. For that, expertise from the leaders of European cross-border associations is used, as well as European Commission officials.

JEL:

1. INTRODUCTION

Rooted in the vision of a balanced and harmonious European Union (EU), the policy goal of territorial cohesion has involved multiple conceptual interpretations and considerable debate. While sometimes analytically perplexing and difficult to translate in terms of concrete indicators (Molle, Citation2007), territorial cohesion has received increasing attention from academics and policymakers since its prioritisation in the 2009 ‘Lisbon’ treaty. The general goal of cohesion is to work towards greater social and spatial equality within the EU, counteracting the disintegrating tendencies inherent in strengthening core–periphery dichotomies throughout the continent. At the same time, Faludi (Citation2007), Van Well (Citation2012) and others have suggested that the notion of cohesion is of necessity ‘fuzzy’ in order to facilitate its implementation as a policy in highly diverse regional contexts. Nowhere is the need for Cohesion Policy flexibility greater than in its application in cross-border and transnational contexts. Many border regions are themselves national and European peripheries seeking development potential while thriving interdependent cross-border regions struggle to generate appropriate forms of governance coordination across boundaries to deal with everyday concerns.

Cross-border cooperation (CBC), which began as a grassroots experiment in intercultural dialogue, has been ‘Europeanised’ and is now subsumed under the official category of European Territorial Cooperation (ETC), which covers a wider spectrum of border-transcending possibilities. However, the original logic of CBC, that of creating multiple synergy effects between public, civil society and economic actors across state borders, has remained an important element in Cohesion Policy. The question the paper raises here regards the contribution of ETC to wider territorial cohesion. The research background has indeed grown significantly in the last two decades suggesting that territorial cooperation at different scales is more than just a niche area of academic interest. Moreover, numerous studies have suggested that territorial cooperation have significant positive development impacts associated with the reduction of barrier effects of national borders (Dühr et al., Citation2010). Many of these impacts are ‘soft’ in the sense of capacity-building and encouraging informal networking, intergovernmental arrangements and cross-sectoral policy coordination between actors (Böhme et al., Citation2011; Faludi, Citation2013; Luukkonen, Citation2010). In terms of concrete economic impacts, Basboga (Citation2020) estimates that between 2007 and 2013, CBC and the reduction of border obstacles resulted in an almost 3% increase in per capita gross value added for Europe’s border regions.

The purpose of this paper is to take stock of the rich research literature on territorial cooperation and its impacts in order to identify specific implications of territorial cooperation for the achievement of European cohesion goals. However, we argue that in order to gauge the impact of territorial cooperation on territorial cohesion, a pragmatic understanding of the latter is needed that reflects actual policy practices rather than essentialist a priori definitions (Abrahams, Citation2014). Andreas Faludi (Citation2007) has argued that when concepts such as cohesion are left ‘fuzzy’, the ability to use them under very different conditions and within different national and regional policy frameworks increases. As Evrard (Citation2022) mentions, territorially in the EU is not a ‘smooth space’ but made of very different legal forms and welfare regimes that impact spatially. Moreover, the significant border effects that persevere within the EU and the ways they impact territorial cooperation at different scales need to be considered. Chilla and Sielker (Citation2022) interpret these border effects in terms of friction and multilevel mismatches and, in their analysis, the uncertain future of the DG REGIO’s European Cross-Border Mechanism initiative due to national administrative hurdles is a case in point.

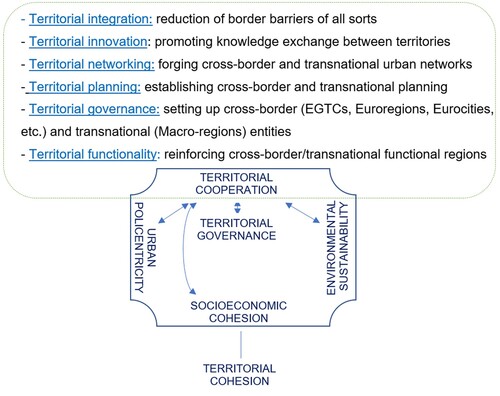

It is evident that the full potential of territorial cooperation to more significantly contribute to territorial cohesion is held back by a number of structural and contextual conditions. With this in mind, the paper suggests six key areas where territorial cooperation has significant socio-spatial impacts and where it can potentially foster territorial cohesion processes in terms of reducing territorial disadvantages and linking together various actors and communities. These six areas entail (1) processes of spatial integration through more intensive administrative, economic and social interaction, (2) processes of social innovation in terms of the diffusion of knowledge that addresses social needs; (3) networking effects that are reflected in territorially flexible cooperation arrangements, (4) the promotion of adaptive planning processes; (5) governance impacts in terms of the formal and informal institutionalisation of cooperation, and (6) the strengthening of functional (e.g., economic, social, service-related) relationships between communities. Clearly, there are numerous overlaps between these different areas and it is these overlaps that reinforce the overall cohesion-related impact of territorial cooperation. As part of the proposed conceptual framework, we situate territorial cooperation within a tension between networked forms of cross-border and transnational interaction, nationally centred understandings of territorial cohesion and the negotiation of administrative and other border obstacles within the EU. Much of the advantage of territorial cooperation lies in the flexible and highly adaptable ways in which knowledge-exchange, agenda-setting and other cooperation activities unfold. In the more concrete context of border regions (borderlands), the benefits of cooperation are tangible in the form of public service delivery, local economic development, etc.

In this context, this conceptual review paper contributes to intensify the debate of the underlying importance of territorial cooperation related processes, including cross-border, transnational and interregional cooperation processes to achieving territorial cohesion. Although the analysis is mostly centred on CBC processes as they are particularly relevant in existing literature and policy implementation examples, namely in Europe. More broadly, the paper provides a first attempt to explore and propose a comprehensive conceptual framework with proposed key components which can contribute to increasing territorial cohesion trends by fostering territorial cooperation processes. These are presented and elaborated here for the first time. Methodologically, the analysis draws mostly on literature review. Ultimately, the research intends to answer the following research questions:

In what measure can territorial cooperation contribute towards more cohesive territories?

In which dimensions can territorial cooperation foster territorial cohesion?

2. TERRITORIAL COOPERATION AND ITS CONCEPTUAL EVOLUTION

Since the early 2000s, regional and spatial sciences have attempted to better understand processes promoting socio-economic integration in Europe and social equality across state borders through a focus on their territorial embeddedness. Unsurprisingly, the results of these research endeavours have been somewhat ambiguous, as territory both promotes and constrains the achievement of social equality, more effective governance and other objectives. Among the key constraints is the frequent self-referentiality and introverted nature of territorial embeddedness of local societies which can exacerbate existing patterns of unequally distributed economic opportunity. At the same time, a strong sense of local territorial identity can strengthen capacities for networked cooperation, and this situation characterises many dynamic and resilient cities and regions throughout the EU (Capello, Citation2018). Consequently, the debate regarding economic, social and political integration has spurred academic and policy-oriented interest in better understanding mutual relationships between European integration processes and local, regional and national cooperation across borders (Durand & Decoville, Citation2020).

As the name indicates, territorial cooperation involves a set of processes, principles and organisational arrangements between two or more entities targeted at normative goals of mutual territorial development and integration benefits (Beck, Citation2019; Guillermo-Ramirez, Citation2018). Normally, these entities are located on different countries and engage in one or more of the three most common processes of territorial cooperation: (1) local and regional CBC; (2) transnational cooperation; and (3) interregional cooperation (Reitel et al., Citation2018). Since the beginnings of Interreg in 1990, CBC has received the lion’s share of EU funds dedicated to ETC. Understood in a myriad of ways in the current literature and EU official reports, CBC can be regarded as a process intended to foster territorial integration by reducing barrier effects and by enriching the territorial assets and social capital of border areas (Medeiros, Citation2015). Similarly, transnational cooperation aims at promoting better cooperation and regional development processes between territories located in different countries, via a joint approach to tackle common issues (Medeiros, Citation2021c). Lastly, interregional cooperation is a question of networking communities beyond territorial proximity and border region contexts (Reitel et al., Citation2018).

The first known conceptual attempt to identify concrete analytic dimensions, components and respective indicators to measure territorial cohesion trends was initiated in 2003 with the elaboration of a ‘star model’ of territorial cohesion. This ‘star model’ proposed a definition of territorial cohesion as:

the process of promoting a more cohesive and balanced territory, by: (i) supporting the reduction of socioeconomic territorial imbalances; (ii) promoting environmental sustainability; (iii) reinforcing and improving the territorial cooperation/governance processes; and (iv) reinforcing and establishing a more polycentric urban system.

Soon afterwards, subsequent attempts were made to advance novel theoretical backgrounds and alternative territorial cohesion models. Amongst others, one can highlight the publication of the Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion which identified ‘territorial cooperation’ as a main policy component of territorial cohesion as ‘the problems of connectivity and concentration can only be effectively addressed with strong cooperation at various levels’ (European Commission, Citation2008, p. 7). Furthermore, the ESPON (Citation2011) report associated one of the seven main advanced dimensions for analysing territorial cohesion (integrated polycentric territorial development) to the need to analyse the degree and intensity of cooperation. In the following year, the ESPON (Citation2012) report proposed an inventory of 20 key indicators for territorial cohesion and spatial planning. By 2013 the ESPON (Citation2013) report provided a more targeted analysis on cross-border spatial development planning. A year later, the European Territorial Monitoring System (ETMS) report (ESPON, Citation2014) included the need for denser cooperation patterns, a key component of one of the five proposed analytic dimensions of territorial cohesion (access to territory and services) (Zaucha & Böhme, Citation2020). Finally, a more recent proposed conceptual model of territorial cohesion invokes the need for a multilevel governance (cooperation of cities) which can create ‘a network-type of economies of agglomeration which are important for the development of medium-sized cities’ (Zaucha & Komornicki, Citation2019, p. 50).

It is frequently argued that ETC is one of the most successful policy implementation stories of the EU (Medeiros, Citation2018). Much of the appeal of ETC derives from its flexibility in creating project-oriented networks that target multifarious development and economic growth concerns, including local services and entrepreneurship, and that expand the remits of local and regional actors (European Commission, Citation2011; Medeiros et al., Citation2021; Svensson & Balogh, Citation2018). Similarly, ETC reinforces multilevel governance processes and a stronger interaction between local and global actors (Louwers, Citation2018). In addition, ETC projects have embraced multi-sectorial policy interventions in crucial dimensions of territorial development, such as the improvement of environmental sustainability and socio-economic development trends (Graute, Citation2006). As the EU Green Deal expresses, ‘Member States should also reinforce CBC to protect and restore more effectively the areas covered by the Natura 2000 network’ (European Commission, Citation2019, p. 13). Moreover, ETC is important to the promotion of urban polycentrism and planning (Decoville et al., Citation2021) and territorial governance processes (Evrard & Engl, Citation2018).

Based on the conceptual development and practical aspects discussed above, we propose a comprehensive and integrated conceptual framework for better understanding the contribution of territorial cooperation to territorial cohesion processes (). This is based on the authors’ experience in analysing the implementation of EU territorial cooperation projects and programmes, and includes the following areas: (1) territorial integration, (2) territorial innovation; (3) territorial networking; (4) territorial planning; (5) territorial governance; and (6) territorial functionality ().

Figure 1. The main components of territorial cooperation as a main dimension of territorial cohesion.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Before appreciating more fully the cohesion impacts of each of the six selected components of territorial cooperation, it should be noted that, as expressed above, territorial cohesion is not understood as economic cohesion in space, as economists often tend to see it, by merely using simplified gross domestic product (GDP) trend analysis. Instead, territorial cohesion is viewed as a holistic and multidimensional concept (Medeiros et al., Citation2022), aligned with the more global level of territorial relations and their policy expressions (Medeiros, Citation2017). It is important to note that these different areas are interconnected. For instance, territorial functionality entails the need for territorial networking between urban areas. The level of functionality (interdependency and interconnectivity) is, however, variable and influences the network flows, and ultimately is largely related with the degree of territorial integration, especially on cross-border regions. Likewise, the higher the cross-border or transnational levels of interaction (knowledge, workers, ideas, capital, tourists, trade, etc.), the higher are the possibilities to increasing levels of territorial innovation. Similarly, the setting up of transnational and cross-border governance structures tends to facilitate territorial networking as well as territorial planning, since they operate according to mutually agreed strategies to develop cross-border and transnational processes. In simple terms, under this conceptual rationale, territorial cooperation contributes to more cohesive territories, by: (1) proactively fomenting the reduction of border barriers (integration) and thus increasing territorial functionality and knowledge exchange; and (2) fostering the establishment of new governance bodies and increasing networking and planning between existing entities.

2.1. Territorial integration, reduction of border barriers

Territorial integration, in the context of transnational spaces, is conditioned by cooperation propensities and practices that connect a variety of actors at different scales (Medeiros et al., Citation2021). Indeed, the imaginary of a highly integrated European space is contingent upon the elimination of existing cooperation barriers (Cappelli & Montobbio, Citation2016) in order to overcome territorial divisions, as ‘problems of connectivity and concentration can only be effectively addressed with strong cooperation at various levels’ (European Commission, Citation2008, p. 7). Overcoming such barriers is essential to ensure that border regions have equal opportunities to exploit their potential, as non-border regions. Border barriers create a significant loss of potential development. In concrete terms, a European Commission (EC) (2017) communication argues that solving 20% of such obstacles would allow for an increase of 2% in border regions’ GDP. Following from the proposed definition of territorial cohesion, the improvement of socio-economic trends in each territory is one of the preconditions to achieving territorial cohesion. In this light, the reduction of border obstacles can positively influence territorial cohesion trends.

In Europe, border interactions have reached increasing levels in recent decades (Castanho et al., Citation2018). These interactions are often measured in all sorts of cross-border flows (Decoville & Durand, Citation2021). For De Sousa (Citation2013), the impacts of increasing integration in border regions can simultaneously contribute to dismantling physical border barriers and boost institutional innovation. For Makkonen et al. (Citation2018), cross-border metropolitan areas and twin cities are frequently mentioned as examples of cross-border integration based on socio-economic interaction. These sometimes-called Eurocities (Medeiros, Citation2021b) are concrete and operational ongoing experiments of territorial cooperation. Crucially, both EU cross-border and transnational cooperation programmes have contributed to reducing cross-border barriers since their first phases, at the beginning of the 1990s. In this regard, Dühr (Citation2018) notes the crucial role of transnational regional-making in Europe in shaping new governance arenas and fostering more differentiated transboundary collaboration. Likewise, Wassenberg et al. (Citation2016) claim that the links between cross-border and transnational territories provide a crucial impetus for territorial integration (European Commission, Citation2021). Ultimately, territorial cooperation has contributed, especially in Europe, via the EU Interreg Programmes, to reducing institutional, legal, administrative, social, cultural, environmental, economic and accessibility-related border barriers, over the past decades (Svensson & Balogh, Citation2018), and consequently to a more cohesive EU territory. Indeed, much contemporary research alludes to the role of border regions as living labs of European Integration (European Commission, Citation2021).

2.2. Territorial innovation: promoting knowledge exchange between territories

For Moulaert and Sekia (Citation2003) cooperation and partnership are key ingredients for territorial innovation processes. As highlighted by the Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion (European Commission, Citation2008) regional innovation clusters (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2021), alongside polycentric development and new forms of partnership and territorial governance can also drive territorial cohesion trends. Being a critical element in current EU policy debates on regional innovation (Makkonen et al., Citation2018) cross-border regions can play and have played a pivotal role in stimulating regional innovation clusters via, for instance, the creation of cross-border university networks, as is the case of the University Alliance in Inner Scandinavia (UNISKA) project:Footnote1 a University Alliance in Inner Scandinavia, which wants to establish and consolidate the collaboration between the universities in Gjövik, Hedmark, Lillehammer and Östfold, on the Norwegian side of the border, and Karlstad University and Dalarna University, on the Swedish side. The alliance cooperates with the region’s business community, and it will be an important strategic party for promoting local and regional development and competence. Indeed, the existing evaluations of EU Interreg-A programmes have revealed their importance in supporting innovation processes in cross-border regions (Mehlbye & Böhme, Citation2018). Similarly, EU transnational cooperation programmes and EU macro-regional strategies have financed, among other things, research and innovation, in human capital and in enterprises, as a means to foment transnational development processes via intergovernmental cooperation (Gänzle & Kern, Citation2016). The salient point here is the positive contribution of territorial cooperation processes to promote and increase knowledge exchange between transnational territories, with the potential to improving socio-economic development trends in the involved regions, which is a vital pillar to foster territorial cohesion trends.

Furthermore, the literature on cross-border regional innovation systems identifies critical elements of regional innovation, such as the support to knowledge infrastructure, that lead to positive economic, integrated and innovative impacts for cross-border regions (Makkonen, Citation2015). In the US–Mexican border region, for instance, Schoik et al. (Citation2004) conclude that an increasing porous border leads to higher rates of exchanges of innovation, ideas and capital. From a territorial cohesion standpoint, regional integration of border areas facilitates the strengthening of the regional economy’s innovative capacity (Krätke, Citation1999). In their essay on the importance of EU territorial cooperation policies, Mehlbye and Böhme (Citation2018) also highlight the need for increasing territorial interactions and interdependencies on innovation policies, among others, in particular within functional areas, for more cohesive territories. In a different prism, researchers are more open to cooperation in the border areas than in the non-border areas, which has the potential to trigger innovation processes in the former areas (OECD, Citation2013). Largely linked to the other five proposed components of territorial cooperation as a main dimension of territorial cohesion, territorial innovation is, however, distinct from them since it is particularly important to condition processes of socio-economic development, regarded as a key pillar for territorial cohesion. And in Europe, for instance, border regions are commonly linked to lagging socio-economic developed regions.

2.3. Territorial networking: forging cross-border and transnational urban networks

In his seminal work on territorial cohesion, Faludi (Citation2006) recognises that its materialisation in concrete policy actions goes beyond the support of socio-economic development related aspects, and that it should integrate development opportunities to encourage cooperation and networking. In a slightly different manner, Servillo (Citation2010, p. 407) proposes that the network paradigm grounds the interpretation of the territorial cohesion concept ‘allowing it to become an expression of connective capacity between regions, either in terms of physical proximity (e.g., the cross-border areas), or, in the absence of spatial contiguity, of common concerns, e.g., network cooperation on specific issues’. Driven by concrete policy measures towards more cohesive territories, Vanolo (Citation2010) alerts us to the fact that the strengthening of polycentric regions towards territorial cohesion requires the improvement of accessibility and communication networks. Ultimately, as Peyrony (Citation2021a) asserts, cross-border arrangements are crucial to build cohesion via the reduction of cross-border obstacles. Hence, increasing support is required for cross-border regional and local authorities to be able to apply tailor-made arrangements to foster new joint bilateral or trilateral agreements, or amending existing mutual agreements (AEBR & European Commission, Citation2020).

Notably, the fundamental notion of territorial cooperation entails the forging of partnerships established between the regional or local authorities (Wassenberg et al., Citation2016). Or, put differently, a territorial networking process in the making. As many would agree, border regions can be represented as networks of linkages resulting from social interactions, networks of firms and other social entities, as well as networks of individuals in certain territories (Strihan, Citation2008). In this line, Dühr and Nadin (Citation2007, p. 388) stress that ‘transnationality is thought of as international networking’. Indeed, regions engage in networking to push for a stronger financial and institutional voice (Plangger, Citation2018), and ‘transnational regions have to rely on a networked structure of governance and some type of network integration that involves actors from different levels and from different countries’ (Dühr, Citation2018, p. 547). In the end, territorial cooperation arrangements ultimately forge territorial networking at all scales, starting from the operation of clusters of neighbouring municipalities and city networking (Mehlbye & Böhme, Citation2018). In sum, and supported by the proposed territorial cohesion model, territorial cooperation, as a vehicle of increasing urban networking, can contribute to territorial cohesion trends via the reinforcement of urban polycentricity levels, in its relational dimension (ESPON, Citation2004).

2.4. The role of territorial planning

Territorial planning, or spatial planning in a more Anglo-Saxon fashion, has been, from the beginning, linked with the notion of territorial cohesion (Faludi, Citation2006). As Van Well (Citation2012, p. 1596) notes, ‘the context in which the concept of territorial cohesion surfaced was an abortive quest for an EU role in spatial planning’. Concomitantly, a rich vein of theoretical thinking conveys territorial cohesion as a new buzzword for spatial planning (Schön, Citation2005), which have been linked closely to European spatial planning policies (Abrahams, Citation2014). If the contribution of territorial planning to territorial cohesion is easily justifiable, such as, for instance, to increase urban polycentrism, compactness and connectivity levels (Medeiros, Citation2016), the role of territorial cooperation is increasingly influential in European transnational collaborations (Nadin & Shaw, Citation1998) towards the implementation of cross-border (Ocskay et al., Citation2021) and transnational planning processes (Sielker & Rauhut, Citation2018). Of particular note was the mandatory requirement for implementing integrated spatial planning in the Community Initiative Interreg IIC (1997–99) (Dühr, Citation2018). This policy goal, was not, however, continued in subsequent Interreg programmes.

As Rivolin (Citation2005, p. 93) puts it, ‘the pursuit of territorial cohesion requires coordination of national planning systems and subsidiarity’. While the principle of subsidiarity is aimed at empowering subnational levels (Moodie et al., Citation2021), governance related to the way power is exercised in the management of specific territory (Rose & Peiffer, Citation2019). Ultimately, increasing cross-border integration tends to stimulate the need for cross-border environmental planning (Hansen, Citation2000). However, as Knippschild (Citation2011) suggests, territorial cooperation in spatial planning is a difficult task and dependent on several factors such as: (1) the size of cooperation areas, (2) structures of the cooperating public administrations, (3) existing transnational organisations and legal frameworks, (4) the intensity of cultural barriers, (5) cooperation transaction costs versus stakeholder expectations and (6) the competences and resources of involved partners. Moreover, several legal and administrative obstacles need to be considered in the area of territorial planning (Liberato et al., Citation2018), and border interactions depend on several elements such as planning activities and infrastructure construction (Castanho et al., Citation2018). By being a holistic concept, spatial planning touches all the dimensions of the proposed territorial cohesion model. As such, by fostering the implementation of cross-border and transnational spatial plans, territorial cooperation programmes have the potential to increasing territorial cohesion trends, not only by contributing to foster socio-economic development, but also to stimulate environmental sustainability and territorial connectivity (polycentricity) in lagging territories.

2.5. Territorial governance as institution-building

Being a complex set of policies by which public powers regulate, from an institutional lens (Rivolin, Citation2010) territorial governance can be regarded as a key dimension and component of territorial cohesion (Medeiros, Citation2016), as it stimulates territorial networking, planning and integration. Established to deal with administrative and organisational matters, cross-border and transnational cooperation entities are seen as concrete examples of territorial governance arrangements, to achieve better policy coordination. These are constantly evolving and adapting, for instance, by fostering joint agendas and establishing governance arrangements (Dühr, Citation2018). Establishing a governance platform for engaging in cooperation involves challenges (Dühr & Nadin, Citation2007) to be capable of functioning as a policy framework (Zonneveld, Citation2005). What distinguishes this governance-related component of territorial cooperation from the remaining five is its direct association with the establishment of transnational and cross-border governance structures, which are commonly viewed as critical element to implement territorial cooperation processes (Lange & Pires, Citation2018).

Crucially, in contrast to the script of the centralised state, territorial cooperation has manifested increasing contributions to the process of institution-building and multilevel governance involving a complex network of actors and entities (Perkmann, Citation1999). Oftentimes, this territorial cooperation imaginary is revealed by the regional construction of cross-border and transnational entities, including Euroregions since the late 1950s, macroregional strategies and, more recently, European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation (EGTCs) (Evrard & Engl, Citation2018). Introduced in 2006, as a governance instrument, EGTCs are often regarded as a form of governance (Wassenberg et al., Citation2016) denominated as ‘soft spaces’ (Caesar, Citation2017). Alongside, border cities, also known as Eurocities in Europe (Jurado-Almonte et al., Citation2020), aim at a greater interconnection between territories and stakeholders (Liberato et al., Citation2018).

For Perkmann (Citation1999, p. 661), CBC governance has positively contributed:

to create new opportunities for actors that might administrative procedures for CBC measures tend to change the strategic landscape both in border areas as being the same as, say, for the implementation of standard well as on a European level.

Needless to say that the formation of transnational regions can be regarded as a gradual consolidation of regional governance (Paasi, Citation2013). Resulting from the direct involvement of EU institutions, the genesis of EU macro-regional strategies (Sielker & Rauhut, Citation2018), was spurred in an EU policy context aligned with the goal of achieving better coordination of EU policies and their spatial impacts. This favourable transnational scenario ‘provided a window of opportunity to introduce a new transnational governance tool, aimed at achieving greater cohesion in selected “macro-regions”’ (Dühr, Citation2018, pp. 559–560). These transnational governance entities permit diverse stakeholders to pursue their goals within different institutional backgrounds, in what is sometimes called as metagovernance practices (Metzger & Schmitt, Citation2012). As such, they can be key vehicles towards increasing positive socio-economic trends in involved territories, and consequently to territorial cohesion trends, based on the proposed star model of territorial cohesion.

2.6. Territorial functionality: reinforcing cross-border/transnational functional regions

A functional region is often regarded as bounded space, or geographical area, defined by a set of linkages, interdependencies and interactions (Haggett, Citation2001). Expectedly, the more integrated and functional a territory, the more cohesive it is (Faludi, Citation2013). Frequently, functional regions are concerned with the human organisation of space whilst capturing the idea of a territory marked by spatially related human activities (Tomaney, Citation2009). For OECD (Citation2020), functional areas bring about several advantages which include the stimulation of cross-border commuting and cross-border governance processes. In this domain, cross-border and transnational areas implicate a complex web of varied territorial elements, including functional spaces or shared ecosystems (Dühr, Citation2018). Hence, as several scholars agree, territorial cooperation enables opportunities that mobilise functional solutions (Plangger, Citation2018). More specifically, Peyrony (Citation2021b) concludes that cooperation across administrative borders within functional spaces contribute to implementing territorial cohesion processes. This can be particularly verified by the contribution of increasing cross-border flows of all sorts, and cross-border connectivity. Both domains are directly linked with polycentricity, as a main dimension of territorial cohesion.

Indeed, for Blatter (Citation2004), functional governance, or spaces of flows are coined by: (1) a polycentric structural pattern of interaction; (2) integration of public and private/non-profit sectoral differentiation; (3) a narrow functional scope; (4) a multiple/fuzzy geographical scale; and (5) fluid/flexible institutional stability. By drawing functional cooperation and territorial cohesion closer together (Gyelník & Ocskay, Citation2020), EU macro-regions encourage, for instance, collective action between private and public actors in multi-sectoral areas (Gänzle & Kern, Citation2016). Driven by new forms of functional cooperation, or neo-functionalism, these macro-regions govern specific policy areas (Piattoni, Citation2016). For Makkonen et al. (Citation2018) cross-border regions are eloquent examples of ‘functionally differentiated systems’ with fuzzy geographical scales. According to De Sousa (Citation2013) neighbouring authorities are forced to negotiate under a functional cooperation environment, whereas Wastl-Walter (Citation2009) asserts that borderlands are functional spaces, which function dynamically, and with asymmetries and differences between both sides of the border. Indeed, Möller et al. (Citation2018) acknowledge that the reduction of border barriers within a cross-border region entails a more functional view of these spaces. These policymakers show of appetite for functional areas is not new. In past years, for instance, the EU programme Interact, closely linked with ETC programmes, organised events debating the importance of ‘functional areas and territoriality’.

3. INTERROGATING THE TERRITORIAL COOPERATION AND COHESION POLICY NEXUS

ETC has had a clear pedagogical effect on the EU integration and cohesion of the former Communist Bloc countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) at three different levels. First, considering that there is no integration without cooperation and no cooperation without interactions, the ETC played a triggering role of interactions. As several (e.g., European Commission, Citation2007, Citation2016a) documents highlight, in many cases, without the Phare and Interreg programmes, no cooperation activities would have been taking place across the previously strictly protected, threatening borders of the region. Indeed, different CBC programmes promoted territorial cohesion via a strategic approach at different levels and by different tools (e.g., the large infrastructural projects of the Hungary–Slovakia–Romania–Ukraine European Neighborhood Instrument (ENI) CBC programme; the strategic projects of the Hungary–Serbia Interreg Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA) CBC and the Greece–Bulgaria, the Romania–Hungary or the Italy–Croatia Interreg CBC programmes) and the integration of projects (e.g., through the tool of Territorial Action Plans for Employment (TAPE), the TAPE of the Slovakia–Hungary Interreg CBC programme) which are essential for the development of cross-border functional areas (functionality).

Besides support for territorial functionality, these examples showcase the positive role of Interreg programmes in fostering territorial networking, planning, innovation and governance. Crucially, ETC facilitated the establishment of cross-border innovative governance structures. While the second half of the 1990s and the first half of the 2000s were characterised by the proliferation of town-twinning and the set-up of Euroregions, since 2008 the number of EGTCs has been remarkably increasing in the CEE countries. Up to 2022, 82 EGTCs have been set up in the EU. A total of 38 of them involved CEE members and 29 had even the seat in the region (some of them are dissolved). Especially the Slovak–Hungarian border is populated by groupings, whose representative participates with an observatory status in the Monitoring Committee meetings of the Interreg CBC programme whose Small Project Fund is managed by the Rába–Danube–Váh EGTC in the west and the Via Carpatia EGTC in the east.

One elegant example of cross-border governance contributing to a more integrated and cohesive territory is the cross-border Hospital of Cerdanya (EGTC-HC) founded in April 2010 (but only operational since September 2014) in the remote and mountainous plateau on the Franco-Spanish border at an altitude of 1200 m, whose inhabitants share a common regional identity, and where the population can increase from 32,000 residents to more than 150,000 in the tourist seasons (summer and winter). With binational staff and patients, it is unique in Europe, despite all the difficulties of operation behind setting the necessary conditions which allowed its realisation. Its day-to-day work entails continuous adaptations, whether to patient reimbursement procedures, employee status or healthcare procedures. The project has led to some very specific progress in the field of European cooperation by providing a concrete policy step to mitigate administrative and legal border obstacles towards a more integrated and cohesive border area.

As expressed by the EU Commissioner for Cohesion, Elisa Ferreira, ‘borders still represent hurdles to individuals, companies, or civil society, due to incompatible legal frameworks or administrative procedures that do not fully consider the territory beyond the border’ (Ferreira, Citation2021, p. 4). Such border obstacles do create a border effect than can be seen as the loss of GDP due to the existence of a border. From Camagni et al. (Citation2017) we can conclude that solving 20% of existing border obstacles would lead to a 2% gain in border regions’ GDP. Other estimates of border effects apply to diverse contexts (Ferreira & Mourato, Citation2011). To reach those goals, the main instrument in Cohesion Policy has been ETC, also known as Interreg. An extensive literature demonstrates its role as the main trigger for CBC experiences in Europe in the past 30 years (Pinto et al., Citation2021; Verschelde & Ferreira, Citation2019).

Territorial cooperation has also contributed to greater territorial integration through the multi-thematic integrated territorial plans (PITERs), financed via the Interreg programme Alcotra (FR-IT) 2014–2020, that has contributed to the economic, social and environmental development of cross-border territories through the implementation of common strategies. The resulted cooperation dynamic may lead to a further structuration of the cross-border governance (creation of EGTCs), with a perspective to be integrated into the cross-border committee that will be set up, following the Quirinal Treaty, signed by France and Italy in November 2021.

Another domain in which territorial cooperation has contributed to more integrated and cohesive territories is via a strong focus by EU institutions to promote the provision of cross-border public services, which foster the mitigation of all sorts of border barriers. In close relationship with the efforts to identify legal and administrative obstacles, this approach can be considered a new generation of initiatives to increase effectively territorial cohesion and integration through cooperation. Some of these cross-border services have already existed for many years, as has been shown in an ESPON targeted analysis (ESPON, Citation2019), but as long as cross-border interaction increases, at least in some border areas, there is a need of developing these services in a growing number of fields, for increasing territorial integration and cohesion.

Finally, the value of ‘soft’ cooperation initiatives has been of particular relevance in the post-conflict context pertaining to Northern Ireland and to the Northern Ireland–Republic of Ireland border region. Without ongoing efforts to address social divisions that in this context are founded on diametrically opposing views on the very nature and existence of the border, initiatives to enhance territorial cohesion would be substantially undermined. That is to a large extent why, complementing successive Interreg-A programmes, since 1995 Northern Ireland and the border counties of the Republic of Ireland have benefited from the establishment of a unique ETC programme: the PEACE programme. The programme’s overarching twin aims of supporting cohesion, between communities involved in the conflict in Northern Ireland and the border counties of the Republic of Ireland, and economic and social stability, not only denote how the two are fundamentally intertwined (with the achievement of lasting peace dependent on social prosperity and cohesion, and vice versa), but also how true territorial cohesion (one that is meaningful to and felt by all citizens in their everyday lives) is dependent on social cohesion across the relevant territory.

4. BY WAY OF CONCLUSION: CBC AS PLACE-MAKING AND COMMUNITY-BUILDING

As the EU Commissioner for Cohesion, Elisa Ferreira has expressed that borders still represent hurdles to individuals, companies or civil society, due to incompatible legal frameworks or administrative procedures that do not fully consider the territory beyond the border. As this paper indicates, in both conceptual and practical terms, territorial cooperation is essentially a response to persistent border barriers. As discussion has indicated, ‘border transcending’ has advanced multilevel and networked governance (in particular via the implementation of cross-border and transnational entities) and the creation of innovation spaces (Makkonen et al., Citation2017). Finally, and especially in Europe, territorial cooperation processes have fomented the implementation of cross-border and transnational planning and territorial functionality, in particular in past years.

This paper proposes a novel conceptual framework aiming at providing a meaningful picture of the main components that territorial cooperation processes (cross-border, transnational and interregional) and how they can contribute to territorial cohesion trends in a given territory. Although the six proposed components (territorial integration, innovation, networking, planning, governance, functionality) are largely interlinked, each has a distinct role in reinforcing territorial cohesion processes. In essence, the paper concludes that territorial cooperation is a crucial process to mitigate persistent border barriers, thus fomenting territorial integration, and ultimately cohesion. Finally, and especially in Europe, territorial cooperation processes have fomented the implementation of cross-border and transnational planning, networking, and territorial functionality, in particular in recent years.

Nevertheless, both in terms of conceptual development and empirical insights, this paper supports the argument that territorial cooperation represents a yet underexploited ‘opportunity space’ for, among others, innovative governance, synergies in the provision of public goods and strategic approaches to territorial development. Unlocking the considerable potential of territorial cooperation in promoting territorial cohesion is subject to complex institutional conditionalities and national interests in the definition of EU Cohesion Policy priorities. Territorial cooperation is also vulnerable to political shocks, temporary border closures and measures such as ‘covidfencing’ which for a time made cross-border interaction highly difficult (Medeiros et al., Citation2021).

In this final section of our joint paper, the authors draw attention to more everyday and less ‘technocratic’ or expert-driven aspects of territorial cooperation. Indeed, it is perhaps fitting in this context to revert to the older concept of CBC which has been highly influenced by local and ‘bottom-up’ experience. Social and territorial cohesion are mutually interdependent and attachment to locale is a major resource for the articulation of individual and collective interests. The suggestion is that territorial cooperation can also be productively conceptualised in terms of place-making projects that not only improve a sense of place identity but also contribute to territorial cohesion trends, through inclusive engagement with locale, for example, in the elaboration of development visions and strategies. In fact, territorial cooperation has been a relatively unrecognised and perhaps neglected pioneer of place-based thinking. This should not be a surprising suggestion, as planning and policy debates have shown for quite some time that place and locality are not mere sites of policy intervention but are communities where meaningful policy action can be co-owned and co-created.

Recognising the importance of local rootedness and a sense of inclusion, achieving a place-sensitive cohesion goal would require greater social understanding, more targeted engagement with different groups and their specific needs, and sensitivity to questions of access, opportunity and local capabilities. At one level then, territorial cooperation can be related to processes of community-building through connecting local organisations, actors and citizens in ways that promote a sense of shared purpose and practical agency. Moreover, this can be more easily achieved if concrete benefits, for example, in the form of public goods and services, are seen to result out of mutual action. Belanche et al. (Citation2016) emphasise the role of local attachments and positive attitudes towards, and greater accessibility of, public services in order to achieve efficiency and sustainable development goals.

Based on the ideas elaborated in the paper, we might conclude with the idea that, in addition to the more formal instruments and procedures that promote territorial cooperation within the EU, territorial cooperation can be strengthened through policy tools oriented towards place-making and community-building. Admittedly, conceiving territorial cooperation in this way still faces the challenges of deep-seated national orientations, both politically and at the level of everyday life. Policy tools are required that incentivise multilevel partnerships, facilitate institutional learning and promote the improvement of local capacities for action. Above and beyond functional and technical integration, social processes such as the creation of communities of practice across borders could also enhance territorial cooperation’s role in strengthening cohesion. To an extent, little of this is really new: territorial cooperation has existed for some time now as community-building projects that create a sense of shared purpose in promoting development goals across borders. However, more specific opportunity structures derived from place-based and community development are needed. Local development is seldom a question of bottom-up agency alone: it is a site where community interests, various levels of governance, multi-actor networks, funding modalities and sources of general support coalesce, but always in highly contingent and specific ways. Ultimately, borders are not only constructed by states. They are also made and remade by everyday individuals as well and are defined by patterns of interaction and exchange.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful for the constructive comments and suggestions offered by two anonymous referees and the editor of this journal.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

REFERENCES

- Abrahams, G. (2014). What ‘is’ territorial cohesion? What does it ‘do’?: Essentialist versus pragmatic approaches to using concepts. European Planning Studies, 22(10), 2134–2155. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.819838

- AEBR & European Commission. (2020). b-Solutions: Solving border obstacles. A compendium of 43 cases, association of European border regions. European Commission.

- Basboga, K. (2020). The role of open borders and cross-border cooperation in regional growth across Europe. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 7(1), 532–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2020.1842800

- Beck, J. (2019). Transdisciplinary discourses on cross-border cooperation in Europe. Peter Lang.

- Belanche, D., Casaló, L., & Orús, C. (2016). City attachment and use of urban services: Benefits for smart cities. Cities, 50, 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.08.016

- Blatter, J. (2004). ‘From spaces of place’ to ‘spaces of flows’? Territorial and functional governance in cross-border regions in Europe and North America. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28(3), 530–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00534.x

- Böhme, K., Doucet, P., Komornicki, T., Zaucha, J., & Swiatek, D. (2011). How to strengthen the territorial dimension of ‘Europe 2020’ and the EU Cohesion Policy? Ministry of Regional Development.

- Caesar, B. (2017). European groupings of territorial cooperation: A means to harden spatially dispersed cooperation? Regional Studies, Regional Science, 4(1), 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2017.1394216

- Camagni, R. (2020). The pioneering quantitative model for TIA: TEQUILA. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), Territorial impact assessment (pp. 27–54). Springer.

- Camagni, R., Capello, R., Caragliu, A., & Toppeta, A. (2017). Quantification of the effects of legal and administrative border obstacles in land border regions. European Commission.

- Capello, R. (2018). Cohesion policies and the creation of a European identity: The role of territorial identity. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(3), 489–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12611

- Cappelli, R., & Montobbio, F. (2016). European integration and knowledge flows across European regions. Regional Studies, 50(4), 709–727. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.931572

- Castanho, R., Loures, L., Fernandez, J., & Pozo, L. (2018). Identifying critical factors for success in cross border cooperation (CBC) development projects. Habitat International, 72(2018), 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.10.004

- Chilla, T., & Sielker, F. (Eds.). (2022). Cross-border spatial development in Bavaria – Dynamics in cooperation – Potentials of integration. Arbeitsberichte der ARL 34.

- Danson, M., & De Souza, P. (2012). Regional development in Northern Europe. Peripherality, marginality and border issues. Regions and cities. Regional Studies Association/Routledge.

- De Sousa, L. (2013). Understanding European cross-border cooperation: A framework for analysis. Journal of European Integration, 35(6), 669–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2012.711827

- Decoville, A., & Durand, F. (2021). An empirical approach to cross-border spatial planning initiatives in Europe. Regional Studies, 55(8), 1417–1428. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1902492

- Decoville, A., Durand, F., & Sohn, C. (2021). Cross-border spatial planning in border cities. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), Border cities and territorial development (pp. 39–55). Routledge.

- Dühr, S. (2018). A Europe of ‘Petites Europes’: An evolutionary perspective on transnational cooperation on spatial planning. Planning Perspectives, 33(4), 543–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2018.1483262

- Dühr, S., Colomb, C., & Vincent, N. (2010). European spatial planning and territorial cooperation. Routledge.

- Dühr, S., & Nadin, V. (2007). Europeanization through transnational territorial cooperation? The case of INTERREG IIIB North-West Europe. Planning, Practice & Research, 22(3), 373–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450701666738

- Durand, F., & Decoville, A. (2020). A multidimensional measurement of the integration between European border regions. Journal of European Integration, 42(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1657857

- European Commission. (2007). Phare Ex post evaluation. Phase 3, thematic evaluations – cross-border cooperation. Thematic evaluation. Phare cross-border cooperation programmes 1999–2003. European Commission.

- European Commission. (2008). Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion. Turning territorial diversity into strength. Communication from the Commission to the Council, The European Parliament, The Committee of the Regions and the European Economic and Social Committee, October 2008, Brussels.

- European Commission. (2011). European territorial cooperation – building bridges between people. European Commission.

- European Commission. (2016a). Ex post evaluation of Cohesion Policy programmes 2007–2013 financed by the European regional development fund (ERDF) and cohesion fund (CF). case study: Hungary–Slovakia cross-border cooperation programme 2007–2013. European Commission.

- European Commission. (2019). The European green deal, COM(2019) 640 final. European Commission.

- European Commission. (2021). EU border regions: Living labs of European integration, COM(2021) 393 final. European Commission.

- European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion (ESPON). (2004). Potentials for polycentric development in Europe, Project ESPON Report 1.1.1, Luxembourg.

- European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion (ESPON). (2006). ESPON 3.2: Spatial Scenarios and Orientations in relation to the ESDP and Cohesion Policy, Volume 5 – Territorial Impact Assessment, Final Report, October 2006, Luxemburg.

- European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion (ESPON). (2011). Indicators of territorial cohesion, Scientific Platform and Tools Project 2013/3/2, (Draft) Final Report, Part C, Scientific report, ESPON & University of Geneva, Luxembourg.

- European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion (ESPON). (2012). Key Indicators for territorial cohesion and Spatial Planning, Interim Report, Version 31/10/2012, Luxembourg.

- European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion (ESPON). (2013). Using applied research results from ESPON as a yardstick for cross-border spatial development planning, Final Report. ESPON, Luxembourg.

- European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion (ESPON). (2014). European territorial monitoring system, Final Report. ESPON, Luxembourg.

- European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion (ESPON). (2019). Cross-border Public Services, Final Report. ESPON EGTC, Luxembourg.

- Evrard, E. (2022). Reading European borderlands under the perspective of legal geography and spatial justice. European Planning Studies, 30(5), 843–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1928044

- Evrard, E., & Engl, A. (2018). Taking stock of the European grouping of territorial cooperation (EGTC): From policy formulation to policy implementation. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), European territorial cooperation (pp. 209–227). Springer.

- Faludi, A. (2006). From European spatial development to territorial cohesion policy. Regional Studies, 40(6), 667–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400600868937

- Faludi, A. (2007). Territorial cohesion and European model of society. Lincoln Institute for Land Policy.

- Faludi, A. (2013). Territorial cohesion and subsidiarity under the European Union treaties: A critique of the ‘territorialism’ underlying. Regional Studies, 47(9), 1594–1606. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.657170

- Ferreira, E. (2021). Preface by the European Commission. In Living in a cross-border region – Seven stories of obstacles to a more integrated Europe. Publications Office of the European Union. doi:10.2776/420556

- Ferreira, R., & Mourato, J. (2011). Border effect in interregional Iberian trade. Journal of Economics and Business Research XVII, (1), 35–50. www.uav.ro/jour/index.php/jebr/issue/view/807

- Gänzle, S., & Kern, K. (2016). A ‘macro-regional’ Europe in the making theoretical approaches and empirical evidence. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Graute, U. (2006). European territorial co-operation to improve competitiveness of the union – The case of EU co-operation in Central and South-Eastern Europe. Edward Elgar.

- Guillermo-Ramirez, M. (2018). The added value of European territorial cooperation. Drawing from case studies. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), European territorial cooperation (pp. 25–47). Springer.

- Gyelník, T., & Ocskay, G. (2020). System error. Reflections on the permanent failure of territoriality of the European cohesion policy. EUROPA XX1, 39(2020), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.7163/Eu21.2020.39.7

- Haggett, P. (2001). Geography. A global synthesis. Prentice Hall.

- Hansen, C. L. (2000). Economic, political, and cultural integration in an inner European Union border region: The Danish-German border region. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 15(2), 91–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2000.9695558

- Jurado-Almonte, J. M., Pazos-García, F. J., & Castanho, R. A. (2020). Eurocities of the Iberian borderland: A second generation of border cooperation structures. An analysis of their development strategies. Sustainability, 12(16), 6438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166438

- Knippschild, R. (2011). Cross-border spatial planning: Understanding, designing and managing cooperation processes in the German–Polish–Czech borderland. European Planning Studies, 19(4), 629–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2011.548464

- Krätke, S. (1999). Regional integration or fragmentation? The German-Polish border region in a new Europe. Regional Studies, 33(7), 631–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409950078675

- Lange, E., & Pires, I. (2018). The role and rise of European cross-border entities. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), European territorial cooperation (pp. 135–149). Springer.

- Liberato, D., Alén, E., Liberato, P., & Domínguez, T. (2018). Governance and cooperation in Euroregions: Border tourism between Spain and Portugal. European Planning Studies, 26(7), 1347–1365. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1464129

- Louwers, R. (2018). The transnational strand of INTERREG: Shifting paradigm in INTERREG North-West Europe (NWE): From spatial planning cooperation to thematic cooperation. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), European territorial cooperation (pp. 171–205). Springer.

- Luukkonen, J. (2010). Territorial cohesion policy in the light of peripherality. Town Planning Review, 81(4), 445–466. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2010.12

- Makkonen, T. (2015). Scientific collaboration in the Danish–German border region of Southern Jutland–Schleswig. Geografisk Tidsskrift – Danish Journal of Geography, 115(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167223.2015.1011180

- Makkonen, T., Weidenfeld, A., & Williams, A. M. (2017). Cross-border regional innovation system integration: An analytical framework. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 108(6), 805–820. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12223

- Makkonen, T., Williams, A., Weidenfeld, A., & Kaisto, V. (2018). Cross-border knowledge transfer and innovation in the European neighbourhood: Tourism cooperation at the Finnish–Russian border. Tourism Management, 68(2018), 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.03.008

- Medeiros, E. (2015). Territorial impact assessment and cross-border cooperation. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2(1), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2014.999108

- Medeiros, E. (2016). Territorial cohesion: An EU concept. European Journal of Spatial Development, 60, http://www.nordregio.org/publications/territorial-cohesion-an-eu-concept

- Medeiros, E. (2017). Uncovering the territorial dimension of European Union cohesion policy. Routledge.

- Medeiros, E. (2018). European territorial cooperation. Theoretical and empirical approaches to the process and impacts of cross-border and transnational cooperation in Europe. Springer.

- Medeiros, E. (2021b). Border cities and territorial development. Routledge.

- Medeiros, E. (2021c). Principles for delimiting transnational territories for policy implementation. Regional Studies, 55(5), 974–985. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1839642

- Medeiros, E., Ramírez, M. G., Ocskay, G., & Peyrony, J. (2021). Covidfencing effects on cross-border deterritorialism: The case of Europe. European Planning Studies, 29(5), 962–982. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1818185

- Medeiros, E., Zaucha, J., & Ciołek, D. (2022). Measuring territorial cohesion trends in Europe. A correlation with EU cohesion policy. European Planning Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2022.2143713

- Mehlbye, P., & Böhme, K. (2018). More territorial cooperation post 2020? A contribution to the debate of future EU Cohesion Policy (Spatial Foresight Brief No. 2017:8). Spatial Foresight GmbH.

- Metzger, J., & Schmitt, P. (2012). When soft spaces harden: The EU strategy for the Baltic Sea region. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(2), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44188

- Molle, W. (2007). European cohesion policy. Routledge.

- Moodie, J., Salenius, V., & Meijer, M. (2021). Why territory matters for implementing active subsidiarity in EU regional policy. Regional Studies, 56(5), 866–878. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1966404

- Moulaert, F., & Sekia, F. (2003). Territorial innovation models: A critical survey. Regional Studies, 37(3), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340032000065442

- Möller, C., Alfredsson-Olsson, E., Ericsson, B., & Overvåg, K. (2018). The border as an engine for mobility and spatial integration: A study of commuting in a Swedish–Norwegian context. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 72(4), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2018.1497698

- Nadin, V., & Shaw, D. (1998). Transnational spatial planning in Europe: The role of INTERREG 11c in the UK. Regional Studies, 32(3), 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409850119760

- Ocskay, G., Jaschitz, M., & Scott, J. (2021). Borderland formation processes. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), Border cities and territorial development (pp. 171–189). Routledge.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2013). Regions and innovation: Collaborating across borders (OECD Reviews of Regional Innovation). OECD Publ.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). Delineating functional areas in All territories (OECD Territorial Reviews). OECD Publ.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2021). Entrepreneurship in regional innovation clusters: Case study of Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai, Thailand (OECD. Studies on SMEs and entrepreneurship). OECD Publ.

- Paasi, A. (2013). Regional planning and the mobilization of ‘regional identity’: From bounded spaces to relational complexity. Regional Studies, 47(8), 1206–1219. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.661410

- Perkmann, M. (1999). Building governance institutions across European borders. Regional Studies, 33(7), 657–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409950078693

- Peyrony, J. (2021a). Border obstacles. In B. Reitel & B. Wassenberg (Eds.), Critical dictionary on borders, cross-border cooperation and European integration (pp. 184–186). Peter Lang.

- Peyrony, J. (2021b). Cohesion. In B. Reitel & B. Wassenberg (Eds.), Critical dictionary on borders, cross-border cooperation and European integration (pp. 131–136). Peter Lang.

- Piattoni, S. (2016). Exploring European Union macro-regional strategies through the lens of multilevel governance. In S. Gänzle & K. Kern (Eds.), A ‘macro-regional’ Europe in the making theoretical approaches and empirical evidence (pp. 75–97). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pinto, A., Ferreira, R., & Verschelde, N. (2021). Public consultation on overcoming cross-border obstacles 2020. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Plangger, M. (2018). Building something beautiful with stones: How regions adapt to, shape and transform the EU opportunity structure. Regional & Federal Studies, 28(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2017.1354851

- Reitel, B., Wassenberg, B., & Peyrony, J. (2018). The INTERREG experience in bridging European territories. A 30-year summary. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), European territorial cooperation (pp. 7–23). Springer.

- Rivolin, U. J. (2005). Cohesion and subsidiarity: Towards good territorial governance in Europe. Town Planning Review, 76(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.76.1.8

- Rivolin, U. J. (2010). EU territorial governance: Learning from institutional progress. European Journal of Spatial Development, Refereed Articles, 38, 1–28. https://archive.nordregio.se/Global/EJSD/Refereed%20articles/refereed38.pdf

- Rose, R., & Peiffer, C. (2019). Political corruption and governance. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schoik, R. V., Brown, C., Lelea, E., & Conner, A. (2004). Barriers and bridges: Managing water in the U.S.–Mexican border region. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 46(1), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139150409603196

- Schön, P. (2005). Territorial cohesion in Europe? Planning Theory &Practice, 6(3), 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350500209397

- Servillo, L. (2010). Territorial cohesion discourses: Hegemonic strategic concepts in European spatial planning. Planning Theory & Practice, 11(3), 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2010.500135

- Sielker, F., & Rauhut, D. (2018). The rise of macro-regions in Europe. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), European territorial cooperation (pp. 153–169). Springer.

- Strihan, A. (2008). A network-based approach to regional borders: The case of Belgium. Regional Studies, 42(4), 539–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701541813

- Svensson, S., & Balogh, P. (2018). Limits to integration: Persisting border obstacles in the EU. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), European territorial cooperation (pp. 115–134). Springer.

- Tomaney, J. (2009). Region, international encyclopedia of human geography (Vol. 9, pp. 136–151). Elsevier.

- Van Well, L. (2012). Conceptualizing the logics of territorial cohesion. European Planning Studies, 20(9), 1549–1567. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.708021

- Vanolo, A. (2010). European spatial planning between competitiveness and territorial cohesion: Shadows of neo-liberalism. European Planning Studies, 18(8), 1301–1315. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654311003791358

- Verschelde, N., & Ferreira, R. (2019). Experiencias de cooperación transfronteriza en la unión europea y su impacto a nivel regional. In L. Bendelac Gordon, & M. Guillermo Ramírez (Eds.), La cooperación transfronteriza para el desarrollo (pp. 158–172).

- Wassenberg, B., Reitel, B., & Peyrony, J. (2016). Territorial cooperation in Europe. A historical perspective, regional and urban policy. European Commission.

- Wastl-Walter, D. (2009). Europe of regions. In R. Kitchin & N. Thrift (Eds.), International encyclopedia of human geography (Vol. 3, pp. 332–339). Elsevier.

- Zaucha, J., & Böhme, K. (2020). Measuring territorial cohesion is not a mission impossible. European Planning Studies, 28(3), 627–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1607827

- Zaucha, J., & Komornicki, T. (2019). Territorial cohesion: The economy and welfare of cities. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), Territorial cohesion (pp. 36–66). Springer.

- Zonneveld, W. (2005). Expansive spatial planning: The new European transnational spatial visions. European Planning Studies, 13(1), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965431042000312442