ABSTRACT

After unprecedented events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, organisations reflect on their responses. In this research, we explore how regional creative industries responded to the pandemic to inform future strategies, government and council policies, and crisis responses. This article explores how community and fringe theatres, known for their community connections, responded to the pandemic in several high-growth regions in Queensland, Australia. Much like the general community, these theatres responded and were impacted differently; some felt little impact, while others were severely financially and creatively impacted. While they all had to adapt, the fringe theatres were more likely to further innovate.

JEL:

1. INTRODUCTION

Creative industries can be defined as creative activities and skills that are applied by individuals in a way to acquire wealth and create job opportunities (Department for Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport (DCMS), Citation2018). These creative activities are linked to industries such as advertising and marketing; architecture; design and designer fashion; film, television, video, radio, and photography; information technology, software, and computer services; music, performing, and visual arts; publishing (Khlystova et al., Citation2022), and new media. These activities tend to have traditionally clustered in a relatively small number of well-known global and mostly urban hubs, for example, New York and London (Brydges & Hracs, Citation2019). However, regional communities can also be incubators of creative output (Brydges & Hracs, Citation2019). These incubatory arts’ practices (through artist-run initiatives) (de Klerk & Hodge, Citation2021) can be more focused and connected to their communities in regional areas when compared with ones in urban areas (Duxbury, Citation2021; McDonald & Mason, Citation2015, p. 217). Beckett et al. (Citation2020, p. 4) go as far as to argue that ‘regional, rural and remote cultural activity often punches above its weight in finding new modes of expression, fostering community, and contributing to the local economy’. Furthermore, creative practices in regional communities can lead to unique, sustainable, and innovative practices and ideas and broader understandings of the community (McDonald & Mason, Citation2015). As such, there is a growing body of work exploring creative industries in regional localities due to both academic and policy interests (Andres & Chapain, Citation2013). Prior research has explored regional creative industries through various lenses, such as policymaking (Andres & Chapain, Citation2013; Watson, Citation2020), economic development (Currid, Citation2009; Leriche & Daviet, Citation2010), and urban development (Miles & Paddison, Citation2005). However, as the world begins to chart a way forward from the COVID-19 pandemic, exploring how regional creative industries grappled with and responded to COVID-19 is a pertinent area of research to help inform government and council policies, and practices generally, and to prepare for any future pandemics.

This research paper seeks to address this research gap by exploring how community theatres in several regional growth areas in Queensland, Australia, responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. Australian community theatres are known for their strong connections to their communities as well as the ability to innovate. Within Australia, regional theatre is a dynamic force that has and continues to enhance communities. Australia has a rich history of community theatre dating back to the 1960s and has been a major contributor to the understanding of Australian ‘culture’ and ‘national identity’ and has given voice to large numbers of marginalised groups (Watt, Citation1993, p. 11). The communities in which these theatres operate can be strongly invested and engaged in their theatres (Warren, Citation2019) due to much of the theatrical and other work in them being done by volunteers and thus unpaid. Loewendahl (Citation2020, p. 175) studied three regional theatre companies in Victoria, Australia, and found that ‘it is precisely because they are unpaid-led that emotions and associated emotional labour take on extra weight regarding their regional economies’. As such, Australian regional community theatres are strongly connected within their communities. However, the COVID-19 pandemic and associated health orders isolated these theatres from their communities and aspects of their identities. This research explored how 13 community theatres based in two regional growth areas in Queensland responded and adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Community and fringe theatre

Community theatre, also sometimes known as amateur theatre, can often involve substantial volunteering from making costumes, building and dismantling the sets (Penny & Gray, Citation2017), and the maintenance of the physical theatre location (Gray, Citation2020). These activities are in addition to the volunteer roles taken on by directors and cast members. These back-of-stage volunteer processes are essential to productions, and also help contribute to a sense of belonging with fellow volunteers, the theatre and the wider community (Penny & Gray, Citation2017; Sigurðardóttir, Citation2017). As such, community theatres have an innate and strong connection within their local communities, which is especially strong within Australian community theatre. During interviews with community theatres on the Gold Coast and Toowoomba in Queensland, Mitchell (Citation2015) found that community theatre develops its connectivity via ‘affirmation of values’, ‘solidarity in terms of shared experiences’ and develops ‘relationships for encouragement and for entertainment’ (p. 200). It should be noted here what Mitchell observed in the interviews: a ‘sensitivity among participants about the perceived quality of the experience and the use of the word ‘amateur’, ‘and thus many individuals instead use the term ‘community theatres’ (p. 197).

van Erven (Citation2001, p. 244) noted that it is ‘difficult to pigeonhole’ community theatre, but general characteristics of the artform include the reliance on ‘community support’, the ‘improved self-esteem’ of participants and ‘the ability to adapt pre-planned structures and schedules to unforeseen developments’. Sigurðardóttir’s (Citation2017) research on Icelandic theatre indicates that community theatre participants and performers have no desire to be ‘professional’ (to make a living from their art). That said, community theatre does need to engage with some business practices, such as promotion and sales as they, like other creative practitioners, are effectively running small businesses (Chen et al., Citation2018). Therefore, community theatres, like other creative practitioners, have two identities: one as a creative practitioner, and the other as a small business that enables and sustains their creative output (Eikhof & Haunschild, Citation2006). These two identities can create tension as the creative practitioner can find the differing priorities of profit and creativity to conflict with each other (Jaouen & Lasch, Citation2015; Paige & Littrell, Citation2002; Pisotska et al., Citation2020). Sigurðardóttir (Citation2017, pp. 193–194) also draws attention to the subliminal experience of creating community theatre that provides a ‘separation from our ordinary world’ and ‘a revitalization and an opportunity for personal growth and interpersonal connections that do not happen just anywhere’. Unless community theatres receive funding and community support, which is rare and precarious, they must break-even when putting on a show as they incur costs such as purchasing props, designing sets, and potentially leasing or hiring performance spaces. Community in this sense also refers to building social ties, social practices, and social cohesion (Duxbury, Citation2021).

Community theatre is a broad term that can also encompass regional theatre, theatre that is located within regional communities, and fringe theatre. Watt (Citation1993) notes that community theatre very much includes the fringe theatre characteristics of a political agenda, accessibility, playfulness, and challenges to notions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ art. Community theatre is also described as a ‘place’ to inspire social change (McKenna, Citation2014) and an ‘instrument for community sensitisation and mobilisation’ (Inyang, Citation2016, p. 149). Fringe theatre is a fluid term that generally describes performance that challenges established norms, is politically motivated, accessible, and low budget regarding both ticket costs and the production budget (Chambers, Citation2011). In the creative industries, the term ‘fringe’ has become inextricably linked with the phenomenon of fringe festivals that provides opportunities for emerging artists and is based on a philosophy of being ‘accessible, inexpensive and fun’ (Bushnell, Citation2004, cited in Frew & Ali-Knight, 2009, p. 215). Fringe festivals also challenge established norms or practices and notions of ‘high’ and ‘low’’ arts (Quinn, Citation2005). The importance of theatres becoming more entrepreneurial has been widely discussed in the literature (de Klerk & Hodge, Citation2021; Frigotto & Frigotto, Citation2022). Increased challenges necessitate theatres to make do with whatever resources they have available and develop strategies accordingly (de Klerk, Citation2015). The need to be resilient and innovative in their approaches became even more important for theatres during the COVID-19 pandemic to survive and thrive.

For this research, we define resilience as organisational resilience, since the theatres’ resilience is not an individual activity, but rather the combined effort by a range of stakeholders. Therefore, we describe resilience as ‘adapting to the requirements of the environment and being able to manage the environment’s variability’ (McDonald, Citation2006, p. 155). This adaptability ‘includes both stability and change at a consistent level; it refers to a system’s ability to produce buffer capacity, withstand shock, and maintain function during a transition to a new state’ (Pinheiro et al., Citation2022, p. 15) and was used by the theatres to navigate and respond to uncertain times. To be resilient, organisations need to change their approach according to the situation and what is needed internally at any given time (Burnard & Bhamra, Citation2019). This flexibility in their approach needs to be strategic. It could include new combinations of stakeholders and resources or create new resources to remain relevant and reach the organisational long-term goals (Krueger, Citation1993). Resilience increases the performance and competitiveness of organisations (Pratono, Citation2022) including theatres. In everyday operations, theatres must use this resilience mindset because the general creative industry environment demands constant change, perseverance, and adaptability to navigate the dynamic economic, regulatory and market pressures that are the norm (de Klerk, Citation2015). This resilience mindset includes a critical capacity to adapt to a dynamic environment and this leads to increased efficiency and efficacy (Abourokbah et al., Citation2023). However, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in extensive upheaval and change that demanded further resilience and adaptability on the part of the theatres to navigate negative conditions.

2.2. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Australian arts and theatre

Australia’s borders were closed to non-residents on 20 March 2020, and many other countries around the world also closed their borders (Khlystova et al., Citation2022). Shortly after, Australia’s states and territories also closed their borders and imposed social distancing measures and the closure of ‘non-essential services’, which included leisure and the arts. These restrictions began to be progressively eased from 2 May 2020. The impact of the first wave of COVID-19 and the resulting lockdown resulted in Australia’s first recession in 30 years, with the overall arts sector one of the worst impacted (Marsh, Citation2020). Between 16 and 23 March 2020, 73% of arts and recreation businesses reported that their business had been adversely affected by COVID-19 in the previous two weeks – second only to accommodation and food services businesses (78%) (Australia Council, Citation2020). The impact on the arts sector of just the first wave of COVID-19 was estimated to be between AU $850 million and AU$2 billion (Marsh, Citation2020). Impacts included loss of revenue from performances, festivals, speaking engagements, venue and costume hire, inability to hire or pay staff or contracts, rents, and utilities as well as mental health impacts (Australia Council, Citation2020). Due to the short-term contract-based nature of arts and theatre employment (Khlystova et al., Citation2022), many performers were let go without severance pay and were not eligible for JobKeeper (Reich, Citation2020), the Australian government’s wage subsidiary scheme offered from 28 March 2021. During the March lockdown, it was reported that music and theatre organisations within Australia, and around the world, turned to the internet to broadcast performances without audiences (Morris, Citation2021). However, it was found that the experience of watching such performances live was difficult to replicate and audiences were reluctant to pay the full cost. Digital technology also made it harder for rights holders to exert control over their work (Morris, Citation2021). While the live-streaming of theatre and other artistic events made the creative industries accessible during a lockdown, it was unable to replicate the communal aspect of a theatre performance (Mueser & Vlachos, Citation2018), which is a key part of its appeal and enhances the emotion and intensity of the experience (Majumdar & Naha, Citation2020). Furthermore, performers found it challenging to engage with a distant audience; the lack of audience feedback and reactions changed how they experience theatre and perform (Mueser & Vlachos, Citation2018).

Even when the March lockdown was lifted, many theatre companies were unable to begin performing again until more restrictions were eased due to social distancing and audience capacity limits making performances financially unviable until further easing took place in late 2020 (Jefferson, Citation2020). The initial Australian wave of COVID-19 cases was brought under control by the end of April 2020, although additional lockdowns were imposed by individual state and territory governments to counter new waves of disease, prominently in the two most populated states of Victoria and New South Wales. Theatre groups in regional Australia in 2021 reported fatigue as they had to develop plans to operate safely, continually cancel shows and communicate with audiences as lockdowns were imposed or lifted as well as try to plan how they would operate once lockdowns permanently ceased amid concerns about policing audience vaccination requirements. Lockdowns in cities hundreds of kilometres away can impact theatres in regional areas as the theatres can sell to school groups or tourists. Regional theatres have also reported missing the joy, connections, and relationships that come from operating (Blake, Citation2021). As noted, the communal aspect of community theatre is at the centre of its being, and these theatres can help bring a regional community together. The role of communities in times of adversity and hardship also has been found to support individuals and organisations to be more resilient. The creative industries, as one of the most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, had to be especially resilient and needed to rely on the resources that they could access in and from their local communities (Ratten, Citation2021). However, the lockdowns and health restrictions meant the community theatres were unable to engage with their communities (Jacobs et al., Citation2020). The restrictions on volunteers and other patrons of the arts to be involved in the hosting, managing, and operations of these community theatres’ events added to the challenges faced by them, especially in regional settings (Beckett et al., Citation2020). They were also faced with no revenue from ticket sales due to restrictions necessitating the cancellation of their shows. Prior research into COVID-19 and the creative industries found that, in general, these industries were not well supported by governments, and that practitioners had to be resilient and adaptative to survive (Khlystova et al., Citation2022). Research also established how entrepreneurial management decisions (Purnomo et al., Citation2021) aided by some responsive government policies (Frigotto & Frigotto, Citation2022) helped navigate uncertain times and find opportunities to adapt during COVID-19. However, research into how theatres, community or otherwise, responded to and survived the pandemic is limited. In this research, we focus on 13 regional community theatres in regional Queensland. The research explores how these theatres responded to the COVID-19 pandemic to navigate the uncertain and rapidly changing landscape. We focus on their motivations and the processes they used to contribute to the literature on theatre and creative industry business model innovation and resilience.

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Research design and data collection

The location of this research was the Sunshine Coast (including the Noosa Shire) and Moreton Bay regions in south-east Queensland, Australia, due to their prevalence of theatre companies, and the culture and environment that supports them. The Moreton Bay, Sunshine Coast and Noosa Shire regional councils have included a focus on arts and culture in their strategic and community plans. The Moreton Bay Regional Council notes it wants to ‘develop and showcase the region’s diverse arts’ sector (Moreton Bay Regional Council, Citation2017, p. Citation19), while one of the five outcomes resulting from the Sunshine Coast Council 2019–2041 community strategic plan was a creative, innovative community including support for the arts (Sunshine Coast Council, Citation2019). The Noosa Shire Council has a specific cultural plan to enhance capacity in the cultural arts, recognising its importance to the economy and society (Services & Organisation Committee, Citation2018). Furthermore, both councils are focusing on tourism, arts and culture to help enhance their attractiveness as tourism destinations by providing and funding attractions and events for visitors. As such, these regions were considered suitable to investigate regional theatre companies’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ethics approval was sought and granted from the authors’ institution (ethics approval number A211527). Representatives from 13 community and fringe theatre companies across the Sunshine Coast and Moreton Bay regions were interviewed using semi-structured interviews (). Interviews commenced in January 2021 and concluded in June 2021. To ensure informed consent, all participants were provided with an information sheet before the interview and verbally reconfirmed their consent to take part and have the interview recorded. Participants were recruited using snowball sampling to use the networks maintained by the researchers and to take advantage of the networks between the theatre companies themselves. Recruitment ceased when theoretical convergence was achieved, and interviews failed to provide new insights or new information (Patton, Citation2002).

Table 1. Interviews’ participant profile.

Using semi-structured interviews allowed for follow-up questions, probing and clarification to gain rich insights (van de Weerd et al., Citation2016). The interviews commenced with a grand tour question (Leech, Citation2002) asking participants to describe their theatre company before moving on to specific questions about the impact of COVID-19. Prompt questions (Leech, Citation2002) were used to elicit further details and insights. The interviews predominantly took place over the phone (n = 8), although some were via Zoom (n = 3) or face to face (n = 2). Participants were asked which interview method was most convenient for them given the pressures they faced during COVID-19 and reactivating their theatres. All the interviews used the same structure to ensure validity and were conducted one on one with the theatre representative, who was the owner or president, except community 7 which was with the president and the treasurer. The interviews were transcribed using artificial intelligence-powered software, and then checked, listened to and edited by the interviewer to ensure accuracy. The participants are listed in and are classified as fringe or community theatre based on their self-reported descriptions.

3.2. Data analysis

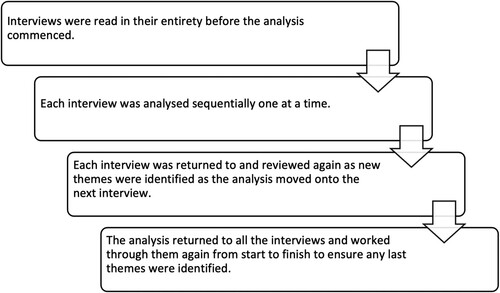

This research adopted a qualitative approach using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Qualitative analysis aided in understanding the participants’ thoughts, feelings and attitudes regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (Guest et al., Citation2012). The data were analysed using a traditional human interpretative approach in combination with the software program NVivo 12 plus to allow for greater accuracy of meaning (Arvidsson & Caliandro, Citation2016; Kozinets et al., Citation2018). The human coder analysed each interview transcript, and analysis moved on to the next transcript when no new themes could be identified, or existing themes were not further refined. The process was iterative and continuous, and transcripts were returned to and re-examined to refine codes and groupings as the analysis progressed (McCosker et al., Citation2004). To ensure validity, peer debriefing was used during the coding process to validate the thematic analysis and the codebook (Creswell & Miller, Citation2000). The qualified peer researchers were the two co-authors of the study who did not participate in the coding process. Thus, the analysis also applied the phenomenographic approach involving iterative familiarisation, analysis and interpretations to consider collective meaning (Åkerlind, Citation2012; McCosker et al., Citation2004). A theoretical rather than an inductive approach to the data analysis coding was adopted to provide a nuanced account of specific themes instead of a description of all the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Thematic analysis’s flexibility can become a limitation if the research is not sufficiently focused (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), thus the coding was guided by the research objective and question. provides an overview of the codebook used to identify the themes that emerged from the research.

Table 2. Codebook.

A visual illustration of the analysis process is presented in :

4. RESULTS

Overall, the resulting themes can be clustered together into three general categories. These were (1) how the theatres view themselves in relation to their communities and business, (2) how the theatres were impacted by and responded to the COVID-19 pandemic health orders and (3) how the theatres returned from these health orders. For clarity, the following results section uses these categories to structure the presentation of the results.

4.1. The theatres and their communities

As expected, based on the literature, the community was a critical aspect of the theatres. Seven of the eight community theatres explicitly noted that they had a strong community and family feeling within the theatre. Their theatres were a community and family within themselves, but they were also involved in and provided for their wider, external community. As one theatre put it, ‘our mission is to provide a variety of performances to suit diverse audiences and have an ever-growing family of volunteers. So, we do see it as a theatre family’ (community 7). The participants also stressed how they were inclusive in terms of the audiences they welcomed, the shows they put on, and the way they behaved towards their members. That they were friendly, warm, and welcoming was important to the theatres. Eight of the participant theatres, 61%, had been in operation for 10 years or more giving them ample time to establish a reputation and networks within their community. This included all the community theatres, for whom the connection with their community is a core aspect. Four of the community theatres also explicitly noted they had a core audience group who ‘see just about everything we put on’ (community 10), while six theatres believed they had a mixed and diverse audience group: ‘We often see people who’ve never been at the theatre before’ (community 7). This suggests that the theatres are valued by diverse elements of their communities as something special and important. Thus, it is indicative that the communities of these theatres value the contribution they make to their community. Furthermore, two of the fringe theatres noted they consulted with the community as to the kind of productions they staged. ‘So, our goal is to usually consult the community, devise our shows, based on each of those issues, and bring the shows to the heart of the community’ (fringe 4). Considering that the fringe theatres, in general, were more newly established, they were still building networks within their region and community, which could account for the fact that community was not as much of a focus for these theatres.

4.2. The theatres as businesses

Interestingly, in contrast to prior research, four community theatres and one fringe theatre explicitly explained they require a positive financial outcome to continue to stage shows. As one theatre put it: ‘We’ve got to put on good plays, get bums on seats so we can keep the doors open’ (community 11). Another two community theatres were more implicit and aimed to break-even with each show. Relatedly, five theatres noted they staged shows they believed would appeal to their audiences and communities. That is not to say that the theatres did not have a passion for the arts. Six of the theatres explicitly stated they did, and the amount of time and effort each theatre put into their productions and running them was motivated by the love of what they were doing. However, the theatres were cognisant of their financial situation and the reality that they were effectively running a business and had to ensure it was sustainable and resilient. As one theatre noted, ‘as a committee, we’ve had a big focus on culture and also prudent, responsible financial management’ (community 8). Three even explicitly talked about marketing ideas and actions, such as running social media accounts and courting sponsorship.

Four of the community theatres also explicitly noted they delivered quality performances and entertainment to their communities: they created ‘high-quality performances that are affordable’ (community 13). Just because they were not for personal profit did not preclude them from offering something of quality to their communities that were accessible, but also allowed the theatre to earn enough to continue. Thus, it could be said that the business mindset expressed was motivated by concern for their community. To be able to offer high-quality and affordable theatre, the theatre had to ensure they earned enough to continue. Both the fringe and community theatres felt accessibility was important: communities needed access to enhance culture and mental health. The fringe theatres were also conscious that they delivered quality theatres. Still, they communicated this more implicitly by describing how they wanted to offer thought-provoking theatre or discussing how they worked with clients. One fringe theatre explicitly noted they were ‘professional’ and it was not something they did in their ‘free time’ (fringe 4). Thus, the fringe theatres were more likely to approach theatre and its community contribution as a professional job that earned their personal income. However, both types of theatres were thus clear that they considered the business aspects of their craft and delivered high quality to their audiences and communities.

4.3. Responding to COVID-19

Since both community and finances were important to the theatres, the impact of COVID-19 was two-fold since it isolated the theatres from their communities, and effectively ended their income. Interestingly, the theatres’ experience of the pandemic, initial Australian lockdown, and health restrictions from March to May varied with half of the theatres financially struggling to support themselves. They drained their financial reserves, while the other half could pause all operations and performances and then resume when it was possible. These three theatres attributed their ease to their financial prudence. As one explained: ‘We’re actually quite savvy with our money anyway because we do not rely on ticket sales. … We honestly didn’t find it too difficult’ (community 10).

Of the theatres that found it possible to pause and then restart, two of them had no fixed expenses, while another had significant financial reserves. As one theatre noted, ‘Living in a small community helped us too. The big guys … still have overheads. They’ve still got to pay electricity’ (fringe 1). Thus, whether the theatre owned space or had built up financial reserves had a big impact on how they weathered the pandemic. While some theatres did own their own spaces, others took advantage of their regional communities and networks and hired or used space when they were going to perform.

Two of the fringe companies (fringes 2 and 6) were resilient and used COVID-19 lockdowns to engage in the creative development of new work and skills, and/or the development of artistic networks. Fringe company 2 received several grants that supported the writing of a new play and the creation of a podcast. The artistic director of fringe company 6 maintained and developed their connections by collaborating with artists and networks via zoom and noted that this process ‘forged … those relationships on a much more intimate level’. With the extra time available, due to projects being halted, they were also able to engage in a playwriting mentorship programme.

However, the theatres that relied on performances for personal income or owned their space struggled. These theatres either lost income or had to drain their cash reserves by paying for fixed costs associated with owning a theatre venue and found it very challenging. One theatre explained how, until JobKeeper was available, they had little income for half of the year and ‘was borrowing from mum and my friends and things were really scary’ (fringe 5). Another described how they ‘even turned off the fridge to try and keep our costs as low as possible. It was, it was, really, really hard’ (community 11). For those theatres that operated in their own space, this provided certainty because they knew they had a space to perform in, which could also function as a ‘community place’ and meeting point. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, this flipped and became a liability. Having these spaces and maintaining them without reaping the benefit of using them, added to the financial and emotional burden for theatre operators.

Likewise, theatres that operated more commercially, performed for profit at festivals, or were hired as entertainment were without income until restrictions eased significantly. Therefore, like many other leisure businesses, they were required to be resilient. Interestingly, those who had managed their businesses very well, building up significant reserves, or operated much more casually without fixed costs or ties, weathered the pandemic well. Theatres that generated personal income for the owners, or owned venues, were more impacted.

All the theatres had to postpone productions, but five were able to continue with their planned programme, just delayed. Five theatres had to completely cancel shows either halfway through or just before beginning to perform. For two theatres, this included postponing significant anniversary celebrations. Others had to cancel everything due to rights issues, or the festival or event they were going to perform at was also being cancelled. Regardless, this meant that the community was without a theatre for several months, and the time that the theatres had spent planning, casting, rehearsing and preparing was lost. In these turbulent and uncertain times, community theatre is also seen as a ‘therapeutic’ outlet (Yotis et al., Citation2017) where social and emotional issues can be addressed and communicated in a safe space. Not having an operational space to produce and educate also created a gap in communicating with communities. Three theatres also noted that they lost actors, who moved away or took on new commitments, indicating a loss of cultural capital to the theatre and its community and audiences.

4.4. Returning from COVID-19

Just as they were impacted differently during the restrictions, the theatres also employed different strategies to return to giving performances. These resilience strategies operated in four main areas, business, relationships, creativity, and opportunity, to find a pathway to transition to performing again. Nine theatres modified their performances in some way so they could return more quickly to provide the community with theatre and also recoup some money. Some performed small shows for audiences of just 20 and did more in a day than normal. Some did online performances, some did small outdoor performances, and some did one-act plays. For example: ‘we found a playwright and two fabulous plays, and we did them in gardens and driveways’ (fringe 1) and ‘we put on a very small production called “Love Letters” that was chosen because there were no lines to learn’ (community 11). This meant that theatres adapted the style of their performances, or upskilled and taught themselves new, technical knowledge. As such, the pandemic did allow some theatres to develop new skills and knowledge and put them to use. Six theatres noted they adapted, came up with new ideas during the lockdown, and as result, ‘we discovered that we were really good at being able to pivot’ (community 13). However, four theatres waited to perform a more traditional show, feeling that they needed time to prepare a show of high quality, and they also decided it would not be worthwhile to perform for a smaller audience. Regardless of how they returned, all the theatres had to adapt to the new health measures, such as ensuring social distancing and contract tracing information was collected, which five of the theatres noted was difficult because it was so new. These regional theatres, through different actions, had to improvise, be resilient, and experiment to find the best way forward and seize opportunities.

Interestingly, four of the theatres that adapted were community theatres, while all the fringe theatres adapted or innovated to return more quickly. And of the five theatres that did use Zoom or other online software, none of them felt it was a comparable substitute to live performance: ‘There wasn’t that energy that you can’t explain, that is between a performer and the audience in a live setting’ (fringe 2). All of them felt that the energy and feedback between audiences and performers were missing. This research sheds some light on how regional theatres responded by developing strategies to support their focus and values in turbulent and uncertain times.

The results unpack how these theatres navigated their way through this to be resilient. Regardless of the strategy they employed to begin performing again, the theatres noted they had enthusiastic responses from their audiences when they did return. Theatres noted that they ‘couldn’t accommodate everybody that we would have liked to’ (community 7) and that there was that ‘excitement and the joy just pours off the stage, and the audience gives it back and standing ovations every night’ (community 8). Both the audiences and the theatres were elated to return to the stage, and not just for financial reasons, but for the love of the theatre and performing. Thus, it was not just the audiences, who were excited to be back, but the performers too, which highlights how community theatre can be a dual transfer of passion. The theatres are motivated to put on productions due to their love of the arts, which is the same reason why audiences attend. However, three theatres did note that some of their audiences were hesitant to return due to health concerns or restrictions that might be reimposed, although one added they had a large surge of audiences booking at the last moment. We now discuss the findings and focus specifically on the four resilience strategies employed by these theatres to excel in the post-COVID-19 environment.

5. DISCUSSION

As expected, the theatres noted that community and inclusivity were important aspects of their identity. Community theatres and fringe theatres are known to have a strong sense of belonging (Penny & Gray, Citation2017; Sigurðardóttir, Citation2017), which was expressed by the theatres often using the word ‘family’ or ‘community’ to refer to themselves. At the same time, they also maintained strong relationships with the community concerning the entertainment that they offered (Mitchell, Citation2015). The theatres noted strong support from their audiences upon their return after the COVID-19 lockdowns and health orders ended, which also supports prior work highlighting the investment and connection that the community has in these theatres (Warren, Citation2019) and is indicative of the relationships’ resilience during this time. The strong support was noted by both the community and fringe theatres. Therefore, our research supports the findings of prior research into community theatres’ identities and values. However, in contrast to Mitchell (Citation2015), the community theatres within our study did not express sensitivity about the level of ‘quality’ that they offered. They were often quite confident that they did indeed offer their communities quality, accessible theatre and thus cultural enrichment, representing their creative resilience. Furthermore, our findings are also in contrast to Sigurðardóttir (Citation2017) as the community theatres within our study, while not operating for personal financial gain, were quite explicit and aware that they had business and financial responsibilities, thus needed business resilience. Rather than experiencing tension (Jaouen & Lasch, Citation2015; Paige & Littrell, Citation2002), the theatres in this study appeared to easily merge both the creative and the business aspects of their identities. Although they were passionate about the theatre art they were delivering and were motivated by love, they also had financial goals for their productions and wanted to ensure their theatre could produce enough profit to continue providing for their community.

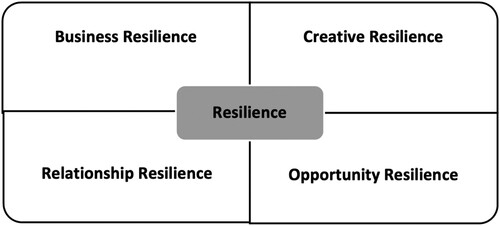

However, our findings supported prior research that community and fringe theatres, like other regional creative industries, are innovative and adaptive (McDonald & Mason, Citation2015). The theatres in this study engaged in numerous adaptive, creative, and even opportunistic practices to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, from adhering to new health restrictions to, in the case of nine, adapting and innovating their performances in various ways, including upskilling and utilising technology, thus exhibiting opportunity resilience. That said, four of the community theatres did not overly modify their performances compared with all five fringe theatres, which are more likely to (in part) be operating to provide a livelihood for their performers. That might suggest that higher business abilities, such as innovation, are harder for community theatres than fringe theatres since fringe theatres are more explicitly a business. How different theatres respond to the challenges and use different types of resilience to navigate these circumstances is explained by the findings. In examining the 13 regional theatres’ practices, we could observe four main resilience strategies that emerged as entrepreneurial responses after transitioning post-COVID-19. These strategies were employed at different stages of the response, but sometimes overlapped or emerged as a combination of strategies. In some cases, the theatres moved from one strategy to another, with some having a stronger preference for a specific one or combination of strategies. The four strategic resilience strategies identified from this research are depicted in and include: (1) business resilience, (2) relationship resilience, (3) creative resilience and (4) opportunity resilience.

Figure 2. Resilience strategies identified by the authors.

In their efforts to move beyond the effects of COVID-19 on the marketplace, they had to adapt, change, trial, and be patient in their approaches. They had to employ this at all levels and build resilience into all that they did. Community capital supported them in this process by enhancing their resourcefulness. From this research, we can describe (1) business resilience as the will to keep things operational, either because the business model strongly dictates what needs to happen as a formal structure or for the preservation of the business model and ‘way of doing things’. For example: ‘But I think the success was that we managed to carry on once the complete ban, you know, the blanket thing that happened in the beginning. I think we were able to work around it and, and still, produce live theatre by carrying out the things that we did’ (community 6).

The strategic focus of some theatres is very much community oriented with their funding, and in some cases, their very existence relies on their community stakeholders. These theatres had to continue to develop (2) relationship resilience to keep the connections and networks optimal during this time. The relationships could include the local regional community, artists, and other stakeholders. The productions and theatre experience were seen as not being replicable online or in other forms. Therefore, this relationship and interaction with the stakeholders dictated their responses:

Well, the theatre was dark for about six months. But once we got our COVID plan in place … , we started with a music workshop run by one of our members. … And then we had our one-act plays. So, we could start to get some money in and have social interaction and connection and offer some entertainment to people who just wanted to be entertained.

How can we make the space work differently? How do you fit this show in a different way and present it differently to an audience and sell it to them knowing that they’re going to come in expecting one thing?

We run the workshops with a theatre. And we perform outdoors, so we’ve done shows in different areas of the Sunshine Coast. Our show last year was at Mooloolaba. This year we’re going to Cotton Tree in the park.

The regional community theatres were more focused on business and relationship resilience, and the fringe theatres were on the opportunity and creative resilience. For community and fringe theatres, the community is an integral aspect of their identity, so the communal aspect of theatre would be of greater importance compared with other, larger theatres in metropolitan areas where the community is more diluted that have incorporated live streaming more substantially.

6. CONCLUSIONS

This paper explored how community theatres, which also encompass fringe theatres, in two high-growth regional areas in Queensland, Australia, were impacted, responded to and adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic. The research has added to the understanding of community and fringe theatre as well as creative industries in regional areas. It was found that, as expected, community and inclusivity were very important to the theatres. However, in contrast to prior research, the theatres were more comfortable with their business identities and confident with the level of quality they were offering in their productions. Much like the general community, the theatres differed in how they were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. While some felt little impact, others were severely financially and creatively impacted. Likewise, the theatres differed in their responses. Although they all had to adapt and practice resilience, the fringe theatres were more likely to innovate further and modify their practices and thus demonstrate more creative and opportunistic resilience.

Our findings uncovered what drives the strategic resilient responses to adverse situations, and the business model and overall focus of the theatres play an integral role in providing direction. The funding support and resources available also steered the organisation towards a specific type of resilience at that time. Even though fringe and community theatres use different business models and resilience strategies, there are touchpoints in their approaches during times of uncertainty. In these post-COVID-19 times, it seems to be more important to the individual theatre’s approach and flexibility to persevere and be resilient. We identified four types of resilience from this research: business, relationship, creative, and opportunity. Still, future research should explore the nuances and transitions between these types of resilience, also possible overlaps, and other emerging themes not presented by this cohort. The findings of this research could expand beyond small businesses that operate in regional communities and beyond creative industries. The resilient responses adopted by the theatre companies depended on their unique approach and outlook, which is not dissimilar to how small business owners influence the strategy of their business (Barnes et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, the connectedness of regional communities meant that central ‘places’ or businesses, such as the local bar, could become a community gathering space, just as a theatre can be. As such, both creative industries and small businesses in regional areas are likely to have some of the same priorities and challenges working with limited resources, but still trying to provide for their local community. Further research should investigate what social inclusion and social cohesion look like for regional areas through theatre and creative industry development compared with urban and developed regions.

Further research could also explore and identify the differences between the fringe and community theatres in different regions, cultures, and countries. The impacts and responses by other types of creative industries in regional localities in Australia and around the world are also rich areas for future study. How these creative industries define resilience and what they attribute to their successful strategies should be explored as well. Furthermore, how the culture, location and connectedness to the community in regions impacted these responses would also appear relevant to explore.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Amy Curran and Eden Mitchell, who worked as research assistants on this project, and the two anonymous reviewers of the manuscript whose comments have helped to enhance it.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

REFERENCES

- Abourokbah, S. H., Mashat, R. M., & Salam, M. A. (2023). Role of absorptive capacity, digital capability, agility, and resilience in supply chain innovation performance. Sustainability, 15(4), 3636. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043636

- Åkerlind, G. (2012). Variation and commonality in phenomenographic research methods. Higher Education Research & Development, 31(1), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2011.642845

- Andres, L., & Chapain, C. (2013). The integration of cultural and creative industries into local and regional development strategies in Birmingham and Marseille: Towards an inclusive and collaborative governance? Regional Studies, 47(2), 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.644531

- Arvidsson, A., & Caliandro, A. (2016). Brand public. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(5), 727–748. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucv053

- Australia Council. (2020). Measuring the impacts of COVID-19 on the Australian arts sector. Australian Federal Government. https://australiacouncil.gov.au/workspace/uploads/files/8042020-summary-of-covid-19-ar-5e8d010193a6c.pdf

- Barnes, D., Clear, F., Dyerson, R., Harindranath, G., Harris, L., & Rae, A. (2012). Web 2.0 and micro-businesses: An exploratory investigation. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(4), 687–711. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001211277479

- Beckett, J., Fensham, R., & Rae, P. (2020). Regional theatre in Australia. Australasian Drama Studies, 77, 1–19. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316informit.645110749527852

- Blake, E. (2021, October 6). ‘The show can’t always go on’: Will regional theatre bounce back in the Covid-normal age? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2021/oct/06/the-show-cant-always-go-on-will-regional-theatre-bounce-back-in-the-covid-normal-age

- Bonin-Rodriguez, P., & Vakharia, N., (2020). Arts entrepreneurship internationally and in the age of Covid-19. Artivate: A Journal of Entrepreneurship in the Arts, 9(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.34053/artivate.9.1.122

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brydges, T., & Hracs, B. J. (2019). The locational choices and interregional mobilities of creative entrepreneurs within Canada’s fashion system. Regional Studies, 53(4), 517–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1478410

- Burnard, K. J., & Bhamra, R. (2019). Challenges for organisational resilience. Continuity & Resilience Review, 1(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/CRR-01-2019-0008

- Bushnell, C. C. (2004). Independent theatres and the creation of a fringe atmosphere. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3(3), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1108/17506180910980528

- Chambers, C. (2011). Fringe theatre before the fringe. Studies in Theatre and Performance, 31(3), 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1386/stp.31.3.327_7

- Chen, M.-H., Chang, Y.-Y., & Pan, J.-Y. (2018). Typology of creative entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial success. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 12(5), 632–656. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-07-2017-0041

- Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into Practice, 39(3), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

- Currid, E. (2009). Bohemia as subculture; ‘Bohemia’ as industry: Art, culture, and economic development. Journal of Planning Literature, 23(4), 368–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0885412209335727

- de Klerk, S. (2015). The creative industries: An entrepreneurial bricolage perspective. Management Decision, 53(4), 828–842. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-03-2014-0169

- de Klerk, S., & Hodge, S. (2021). The case of the creative accelerator. Creative Industries Journal, 14(2), 169–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2020.1813480

- Department for Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport (DCMS). (2018). DCMS sector economic estimates methodology. DCMS. https://osr.statisticsauthority.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Assessment_Report_340_DCMS_Sectors_Economic_Estimates-2.pdf

- Duxbury, N. (2021). Cultural and creative work in rural and remote areas: An emerging international conversation. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 27(6), 753–767. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2020.1837788

- Eikhof, D. R., & Haunschild, A. (2006). Lifestyle meets market: Bohemian entrepreneurs in creative industries. Creativity and Innovation Management, 15(3), 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8691.2006.00392.x

- Frigotto, M. L., & Frigotto, F. (2022). Resilience and change in opera theatres: Travelling the edge of tradition and contemporaneity. In R. Pinheiro, M. L. Frigotto, & M. Young (Eds.), Towards resilient organizations and societies (pp. 223–247). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gray, C. (2020). The repairer and the ad hocist. Performance Research, 25(1), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2020.1747268

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K., & Namey, E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. SAGE.

- Inyang, E. (2016). Community theatre as instrument for community sensitisation and mobilisation. Tydskrif vir Letterkunde, 53(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.4314/tvl.v53i1.10

- Jacobs, R., Finneran, M., & D’Acosta, T. Q. (2020). Dancing toward the light in the dark: COVID-19 changes and reflections on normal from Australia, Ireland and Mexico. Arts Education Policy Review, 123(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2020.1844836

- Jaouen, A., & Lasch, F. (2015). A new typology of micro-firm owner-managers. International Small Business Journal, 33(4), 397–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0266242613498789

- Jefferson, D. (2020, December 8). Melbourne Theatre Company 2021 season a ‘survival year’ following the ‘seismic trauma’ of COVID-19. ABC Arts. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-12-08/melbourne-theatre-company-2021-season-rebound-covid-19/12959002

- Khlystova, O., Kalyuzhnova, Y., & Belitski, M. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the creative industries: A literature review and future research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 139, 1192–1210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.09.062

- Kozinets, R., Scaraboto, D., & Parmentier, M.-A. (2018). Evolving netnography: How brand auto-netnography, a netnographic sensibility, and more-than-human netnography can transform your research. Journal of Marketing Management, 34(3–4), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2018.1446488

- Krueger, N. (1993). The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879301800101

- Leech, B. L. (2002). Asking questions: Techniques for semistructured interviews. PS: Political Science & Politics, 35(4), 665–668. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096502001129

- Leriche, F., & Daviet, S. (2010). Cultural economy: An opportunity to boost employment and regional development? Regional Studies, 44(7), 807–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343401003732639

- Loewendahl, A. (2020). The economic aesthetics of three regional, unpaid-led theatre-producing companies. Australasian Drama Studies, 77, 173–207. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/economic-aesthetics-three-regional-unpaid-led/docview/2481234641/se-2?accountid=28745

- Majumdar, B., & Naha, S. (2020). Live sport during the COVID-19 crisis: Fans as creative broadcasters. Sport in Society, 23(7), 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1776972

- Marsh, W. (2020, June 25). The arts receive $250 million federal stimulus, but is it months too late, and hundreds of millions short? Adelaide Review. https://www.adelaidereview.com.au/arts/2020/06/25/arts-covid-federal-250-million/

- McCosker, H., Barnard, A., & Gerber, R. (2004). Phenomenographic study of women’s experiences of domestic violence during the childbearing years. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 9(1), 1–16. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Phenomenographic-study-of-women’s-experiences-of-McCosker-Barnard/59c4ef3794f1639b7dfed889dddd8c9659ce87d4

- McDonald, J., & Mason, R. (2015). Creative communities: Regional inclusion and the arts. Intellect Books.

- McDonald, N. (2006). Organisational resilience and industrial risk. In E. Hollnagel, D. D. Woods, & N. Leveson (Eds.), Resilience engineering: Concepts and precepts (pp. 155–179). Ashgate.

- McKenna, J. (2014). Creating community theatre for social change. Studies in Theatre and Performance, 34(1), 84–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682761.2013.875721

- Miles, S., & Paddison, R. (2005). Introduction: The rise and rise of culture-led urban regeneration. Urban Studies, 42(5–6), 833–839. https://doi.org/10.1080/2F00420980500107508

- Mitchell, P. (2015). Practising for life: Amateur theatre, regionalism and the gold coast. In J. McDonald, & R. Mason (Eds.), Creative communities: Regional inclusion and the arts (pp. 189–204). Intellect Books.

- Moreton Bay Regional Council. (2017, p. 19). Corporate Plan 2017–2022. https://www.moretonbay.qld.gov.au/files/assets/public/services/publications/corporate-plan-2017-2022.pdf

- Morris, L. (2021, July 13). What ballet dancers learned from watching the footy. Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/culture/art-and-design/what-ballet-has-learned-from-watching-the-footy-20210712-p588vi.html

- Mueser, D., & Vlachos, P. (2018). Almost like being there? A conceptualisation of live-streaming theatre International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 9(2), 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-05-2018-0030

- Paige, R. C., & Littrell, M. A. (2002). Craft retailers’ criteria for success and associated business strategies. Journal of Small Business Management, 40(4), 314–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-627X.00060

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods. SAGE.

- Penny, S., & Gray, C. (2017). Materialities of amateur theatre. Contemporary Theatre Review, 27(1), 104–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/10486801.2016.1262850

- Pinheiro, R., Frigotto, M. L., & Young, M. (2022). Towards resilient organizations and societies: A cross-sectoral and multi-disciplinary perspective (p. 336). Springer Nature.

- Pisotska, V., Giustiniano, L., & Gurses, K. (2020). How co creative entrepreneurs respond to the tension between art and business? In Academy of management proceedings (Vol. 1, pp. 19582). Academy of Management.

- Pratono, A. H. (2022). The strategic innovation under information technological turbulence: The role of organisational resilience in competitive advantage. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 32(3), 475–491. https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-03-2021-0046

- Purnomo, B. R., Adiguna, R., Widodo, W., Suyatna, H., & Nusantoro, B. P. (2021). Entrepreneurial resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: Navigating survival, continuity and growth. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 13(4), 497–524. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-07-2020-0270

- Quinn, B. (2005). Arts festivals and the city. Urban Studies, 42(5/6), 927–943. https://doi.org/10.1080/2F00420980500107250

- Ratten, V. (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) and entrepreneurship: Cultural, lifestyle and societal changes. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 13(4), 747–761. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-06-2020-0163

- Reich, H. (2020, December 20). Australian theatre grapples with access, diversity and job losses through the coronavirus shutdown. ABC Arts. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-12-19/australian-theatre-access-diversity-job-losses-coronavirus-covid/12996568

- Services & Organisation Committee. (2018). Noosa Cultural Plan 2019–2023, Attachment 1 to Item 10. (11 December). Noosa Council. https://www.noosa.qld.gov.au/downloads/file/552/2018-12-11-s-o-agenda-attachment-1-to-item-10-noosa-cultural-plan-2019-2023-pdf

- Sigurðardóttir, G. H. (2017). Popular participation: Why do people participate in amateur theatre? Nordic Theatre Studies, 29(2), https://doi.org/10.7146/nts.v29i2.104611

- Sunshine Coast Council. (2019). Sunshine Coast Community Strategy 2019–2041. https://d1j8a4bqwzee3.cloudfront.net/~/media/Files/ComDev%20Files/Sunshine%20Coast%20Community%20Strategy%2020192041.pdf?la=en

- van de Weerd, I., Mangula, I. S., & Brinkkemper, S. (2016). Adoption of software as a service in Indonesia: Examining the influence of organizational factors. Information & Management, 53(7), 915–928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.05.008

- van Erven, E. (2001). Community theatre: Global perspectives. Routledge.

- Warren, A. (2019). Our town local politics, community theatre and power. Performance Research, 24(8), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2019.1718425

- Watson, A. (2020). Not all roads lead to London: Insularity, disconnection and the challenge to ‘regional’ creative industries policy. Regional Studies, 54(11), 1574–1584. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1738012

- Watt, D. (1993). Excellence/access and nation/community: Community theatre in Australia. Canadian Theatre Review, 74(Spring), 7–11. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/excellence-access-nation-community-theatre/docview/211996231/se-2?accountid=28745. https://doi.org/10.3138/ctr.74.002

- Yotis, L., Theocharopoulos, C., Fragiadaki, C., & Begioglou, D. (2017). Using playback theatre to address the stigma of mental disorders. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 55(September), 80–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.04.009