ABSTRACT

Despite universalising ambition, the literature on ‘left-behind’ places is dominated by viral, noisy and Northern examples. Therefore, we examine the case of Zambia’s Western Province, a severely ‘left-behind’ place, to make two arguments based on a Southern experience. First, a systematic conceptualisation of hope shows that hope rather than hopelessness can prevail in ‘left-behind’ places. Second, hope against-all-odds may function as generative mechanism for quiet rather than noisy path-formation processes. Therefore, mundane path development in the (Southern) periphery requires attention if the literature on ‘left-behind’ places is to inform more foundational theorisations of uneven development.

JEL:

1. INTRODUCTION

The spatial imaginary of ‘left-behind’ places has gained traction for highlighting uneven spatial development and explaining the closely related emergence of ‘geographies of discontent’ (De Ruyter et al., Citation2021; Dijkstra et al., Citation2020). ‘Left-behind’ places are typically defined by a ‘combination of economic disadvantage, lower living standards, population loss/contraction/low-growth, a lack of infrastructure and political neglect’ (MacKinnon et al., Citation2021, p. 4). As such, they epitomise the geographical and structural consequences of protracted processes of socio-economic decline and peripheralisation that accompany uneven accumulation processes such as metropolisation, (de-)industrialisation and globalisation (Gordon, Citation2018). Importantly, however, the phenomenon – of being structurally and relatively ‘left behind’ – has received growing attention not only for its structural component, but also for facilitating contentious affect and the rise of anti-establishment backlashes. Noisy and sometimes violent backlashes originating in ‘left-behind’ places and pointing toward industrial or metropolitan regions imply thereby that uneven spatial development is no longer seen as an issue limited to ‘left-behind’ peripheries; it is also an immediate threat to the cohesion and stability of otherwise advantaged core regions (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018).

The rise of ‘left-behind’ places has generated a laudable renewal of interest in more nuanced understandings of uneven spatial development (MacKinnon et al., Citation2021; Tomaney & Pike, Citation2020). Notably, however, research on ‘left-behind’ places remains narrowly focused on cases – typically in the Global North – which have articulated their discontent through popular backlashes. Today, the Brexit movement (Lenzi & Perucca, Citation2021), the anti-establishment parties in the European Union (EU) (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018), the rural electorates in Donald Trump’s presidency (Ulrich-Schad & Duncan, Citation2018), or also the pink and blue tides in Latin America (Edwards, Citation2010) stand for a surprisingly narrow set of particularly resonant case studies.

In this article, we question the focus on mainly Northern and per se noisy case studies. Although this focus is unsurprising given the etymology of the term ‘left behind’ (Pike et al., Citation2023), especially the structural conditions of ‘left behindness’ are just as evident – if not more so – in Global South settings. After all, enduring processes of economic decline and disruptive crises in the agricultural or industrial sectors are most widespread in the Southern periphery (Pike, Citation2022; Schindler et al., Citation2020). More specifically, we argue that recent calls for using the phenomenon of ‘left-behind’ places to inform more foundational conceptualisations of spatially uneven development (cf. MacKinnon et al., Citation2021) risk amplifying two major caveats. First, if qualifying to be ‘left behind’ depends on the place-based agency to articulate the structural symptoms of ‘left behindness’ most virally, loudly or even violently, attention by policymakers – and researchers – would be exclusively directed to places that succeed in formulating their discontent. The perils of uneven spatial development of Southern and quiet(er) places would then be at risk to be disregarded as a whole, even when respective places feature similar or worse experiences of marginalisation. Second, if progressive theory-making is predominantly informed by noisy and Northern cases, a universalisation of Northern experiences emerges as a conspicuous issue (Connell, Citation2014; Obeng-Odoom, Citation2019). Despite universalising claims that ‘a number of territories across the world are being left behind’ (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018, p. 196), a retheorisation of uneven spatial development on basis of a narrow set of ‘left-behind’ examples would not only imply negligence towards Southern theories of uneven development but also fail to learn from insightful experiences made in Southern and quieter ‘left-behind’ places. Indeed, it would be a serious oversight to ignore Southern experiences of ‘left-behindness’ when retheorising uneven development simply because the dark sides of the inherently uneven processes of urbanisation, industrialisation and globalisation have to some extent become accepted as the defining feature of ‘the’ Global South. For it is precisely in the Southern periphery that the multiple consequences of austerity – here geographically understood as a ‘socially regressive form of scalar politics’ (Peck, Citation2012, p. 631) – are not too often the norm rather than the exception, but in their ultimate consequences not only more severe, but also often an existential matter of life and death.

We stress test, therefore, the spatial imaginary of ‘left-behind’ places beyond its Northern bias and noisy expressions. To do so, we examine quantitative and qualitative data from the secessionist Western Province in Zambia, a region in an objectively severe state of being ‘left behind’. The case study supports two arguments. First, we contend that the example of a surprisingly quiet place under severe stress rejects straightforward assumptions that ‘left behindness’ necessarily evokes noisy and sometimes violent backlashes. Whereas the literature on Northern places states that ‘left behindness’ goes hand in hand with the collective feeling that there is no future and no hope, we propose a more differentiated understanding of hope. A systematic conceptualisation of hope helps us move beyond just emphasising hopelessness but also hopefulness. Second, we argue that different modes of hope can help explain contingent forms of mundane regional path development. Whereas ‘left behindness’ is often related to locked-in path development, we propose a four-fold typology of regional path development in ‘left-behind’ places. The typology differentiates potential pathways not only concerning dominant modes of hope but also regarding their likelihood to constitute viral and noisy geographies of discontent. Combining principal elements from the literature on ‘left-behind’ places with elements from the literature on new regional path development contributes thereby an important explanation for why quiet and mundane rather than noisy responses to a severe state of being ‘left behind’ seem to be widespread. We illustrate our arguments with three research questions applied to the case study Western Province. How is ‘left behindness’ in Western Province expressed? What constitutes dominant modes of hope in Western Province? Which pathways are related to these hopes?

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. The next and third sections establish our conceptual framework by examining the role of hope and conceptualising its role in constituting regional pathways under conditions of ‘left behindness’. The fourth section outlines the research region, methods and data. The fifth section presents the results based on primary data from Western Province. The final section concludes our results and positions them within wider debates on and conceptualisations of ‘left-behind’ places.

2. CONCEPTUALISING HOPE AND PATH DEVELOPMENT IN ‘LEFT-BEHIND’ PLACES

An analytical strength of the literature on ‘left-behind’ places is its attention to the combination of structural and affective factors of uneven spatial development (MacKinnon et al., Citation2021). While structural factors entail broadly objectifiable dimensions such as material and pecuniary inequality, affective factors entail more subjective dimensions such as emotional affect, sense of belonging or place attachment among ‘left-behind’ people (Díaz-Lanchas et al., Citation2021; Koeppen et al., Citation2021; Mayer et al., Citation2021). Thus, the literature on ‘left-behind’ places continues to be highly attentive to explaining the economic and material effects of some of the broader forces driving uneven local development outcomes, such as metropolitanisation, (de)industrialisation and globalisation (Gordon, Citation2018). However, the literature on ‘left-behind’ places is also increasingly paying attention to ‘alternative goals’ (MacKinnon et al., Citation2021) of regional development by considering providential services (e.g., culture, care, leisure) as well as affective geographies (e.g., emotions, aspirations, fears, hopes). The latter in particular encourages policymakers and researchers thereby to move beyond conventional growth- and gross domestic product (GDP)-oriented approaches (e.g., post-growth or neo-endogenous development) and consider alternative analytical categories such as well-being, belonging, and social innovation (Fudge et al., Citation2021; Hansen, Citation2021). Although similar calls for more foundational approaches to regional development are not new (Lee, Citation2019; Pike et al., Citation2007; Pike et al., Citation2017), novel approaches informed by the rise of ‘left-behind’ places claim to be more explicitly dedicated to the lived realities and aspirations of people in affected regions (MacKinnon et al., Citation2021).

Emphasising the double-sided character of ‘left-behind’ places – structural marginalisation paired with regional affect – surely is a laudable effort for improving the analysis of uneven spatial development. However, especially the explanatory basis for a crucial affective dimension of ‘left behindness’ is often taken for granted. This is as the burgeoning of discontent, resentment, and populist backlashes is seen as an immediate consequence of a distinct exposition towards the future. Namely, the feeling – or ‘main narrative’ (Nilsen et al., Citation2022, p. 7) – that there is ‘no future and no hope’ (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018, p. 196). Indeed, hopelessness may rather straightforwardly explain how reactionary movements succeed to orchestrate contorted imaginaries of the past and put these in juxtaposition to a bleak future (Ulrich-Schad & Duncan, Citation2018). However, assumptions that foreclose the future to be non-existent, or only in form of dystopia, clearly underestimate the multidimensional nature of hope, even under dire conditions.

To systematically conceptualise hope and its role in quiet or mundane regional path development, we link two conceptual approaches. First, we establish a basic model of hope inspired by Southern literature from development studies and anthropology. Second, we discuss the role of hope relative to the literature on regional path development.

2.1. Hope in ‘left-behind’ places

Hope can be an important factor as it co-constitutes the affective dimension of ‘left-behind’ places. Emphasising hopefulness and hopelessness adds to understanding how future aspirations are affected under adverse regional conditions (Hassink et al., Citation2019). And it adds to explaining future-oriented practices of dealing with ‘left behindness’. Hope is widely regarded for its paradoxical nature and lack of a common definition. Whereas hope is often defined with a positive connotation as ‘the perceived capability to derive pathways to desired goals, and motivate oneself via agency thinking to use those pathways’ (Snyder, Citation2002, p. 249), anthropologists and sociologists, who added perspectives from the global margins, insist that hope contains its negative opposites within itself. For Miyazaki (Citation2017), Hage (Citation2003) and Appadurai (Citation2013), hope is not only also intricately related to fear, disappointment and even despair, but also far from automatically motivating action as it may just as well justify inaction. For instance, Appadurai’s (Citation2013) conceptualisation of the ‘capacity to aspire’ understands hope as a navigational capacity toward the future that may indeed explain confident and active forms of future-oriented action, even under the most radical adverse conditions at the Southern margins (e.g., dump sites, squatter settlements, etc.). By looking for hope where it is least expected, his work on urban slum dwellers recognises not only the persistence of hope, but also that hope is not necessarily expressed through direct action. For him, hope is also at play when people engage in a politics of waiting (e.g., occupying land through temporary dwellings) rather than more explicit action and contestation (e.g., organised protest, open confrontation). This role of hope and its surprising persistence i.e., at the margins of the margins, accordingly, demonstrates that hope operates under the contradictions of confidence versus despair as well as action versus passivity.

Taking the above foundational theories of hope seriously, a conceptualisation of hope in ‘left-behind’ places, must consider both hopefulness and hopelessness as well as action and inaction. In doing so, we adapt the general mechanisms reflected by Lybbert and Wydick’s (Citation2018) behaviourist ‘basic model of hope’. The model is derived from sociological work on the ‘economics of hope’ (Swedberg, Citation2017) and it provides an analytical tool to explain how ‘psychological phenomena affecting economic decisions can exert significant impacts on welfare outcomes and poverty dynamics’ (Lybbert & Wydick, Citation2018, p. 709).

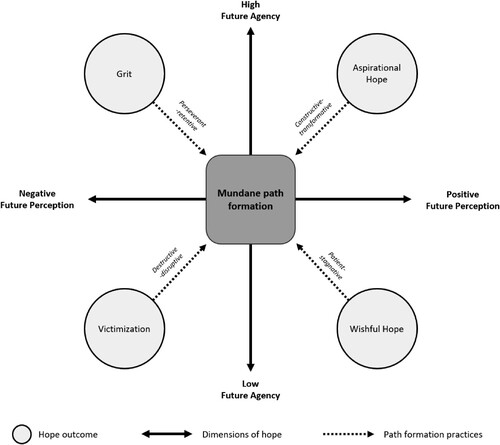

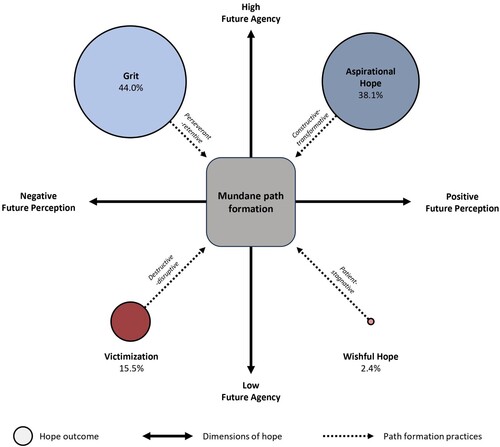

Generally, the model features two explanatory dimensions (). The first dimension, future perceptions, dichotomises a range of future aspirations (e.g., dreaded and desired scenarios) into more negative or more positive perceptions. The second dimension, future agency, depicts self-efficacy in shaping future outcomes, simplified into low or high agency. These two dichotomous dimensions translate into four possible outcomes of hope: aspirational hope, wishful hope, victimisation and grit.

Figure 1. An ideal-type basic model of hope and mundane path formation.

Source: Authors partly adapted from Lybbert and Wydick (Citation2018).

Aspirational hope is the most positive outcome in the model. It includes a positive perception of the future and high agency and drives a self-determined optimism in which agents are highly motivated and optimistic about achieving their desired future. As such, aspirational hope is directly related to a high ‘capacity to aspire’ (Appadurai, Citation2013), which may provide the basis for marginalised communities – and places – to pursue proactive actions that positively shape their future. Typically, aspirational hope would translate into qualitative statements such as ‘I can affect the future and this will help me to achieve what I want’. In ‘left-behind’ places, one may not expect to find a high prevalence of aspirational hope. However, and regardless of whether aspirational hope is justified by the structural barriers and potentials in place, it should be considered as a feasible outcome perceived by people. Indeed, the prevalence of aspirational hopefulness against-all-odds (Kleist & Jansen, Citation2016; Morisson & Mayer, Citation2021) can explain why even the worst structural conditions are not necessarily inciting reactionary affect and noisy discontent.

Wishful hope derives from a low agency over the future while aspirations are nevertheless optimistic. Wishful hope can lead to a stagnant but optimistic fatalism, sometimes also referred to as ‘aspirations fatalism’ (Bloem et al., Citation2018). Optimistic fatalism acknowledges that simply having optimistic aspirations can be futile and even harmful. This is as wishful hope risks relying on a falsely informed, paralysing hope that relief provided by external actors such as the state, development agencies or even metaphysical forces (e.g., God, fortune, etc.) is the only form of available agency. Rather than inspiring actors to act, wishful hope is overwhelming and it can prevent actions that would make otherwise feasible aspirations come true (cf. Swedberg, Citation2017). Wishful hope typically translates into statements such as ‘I cannot affect the future, but I am optimistic that someone else will shape my future positively’. In ‘left-behind’ places, wishful hope can be a double-edged sword. Its underpinning optimism allows people to remain reasonably hopeful and endure periods of decline, marginalisation and catastrophe through implicit or explicit politics of waiting (Stasik et al., Citation2020); yet its underpinning fatalism may mute actually existing agency, distort the full range of proactive actions, and even obscure the acute need for interventions by outside agents (e.g., the state, development aid).

Grit includes negative perceptions about the future paired with high agency. It leads to self-determined pessimism that recognises structural and material limits and acknowledges partly insurmountable dependency on external factors. However, grit does not translate into feelings of helplessness or hopelessness. Instead, grit may even encourage agents to work harder, stay stubborn, or simply ‘hanging in’ to conserve existing livelihoods despite dire conditions (Aring et al., Citation2021; Dorward, Citation2009).Footnote1 Grit would typically translate into statements such as ‘Even though the future is bleak and out of my control, I will carry on making the best out of it’. In ‘left-behind’ places, grit can be a dominant and highly relevant phenomenon. On the one hand, grit may alleviate out-migration, widespread paralysis or fatalism as it implies that people pragmatically continue or adapt their mundane, everyday practices under the expectation to prevent otherwise uncontrollable structural conditions from full escalation (cf. Oldfield & Greyling, Citation2015). On the other hand, grit relates also directly to practices of acquiescence, understood as silent disagreement, rather than explicit resistance which may numb or fully succumb the formulation of explicit discontent (Hall et al., Citation2015).

Victimisation is the most critical outcome. It is constituted by negative perceptions about the future merged with low agency. Victimisation resembles pessimistic fatalism, which is characterised by perceived powerlessness and highly fatalistic feelings about the future. While pessimistic fatalism may lead to a forfeiture towards an ostensibly foreclosed and daunting future, it can also provide the substrate for protest, resistance or even violence and sabotage under the premise that there is ‘nothing to lose’ (Saab et al., Citation2016). Qualitatively, victimisation would translate into statements such as ‘I cannot affect the future and I am without hope that someone or something will shape my future positively’. In ‘left-behind’ places, victimisation resonates with the widespread notion of hopelessness and a foreclosed future. Such disenchantment may imply that hope is ‘threatened by nausea, fear, and anger for many subaltern populations’ (Appadurai, Citation2013, p. 299) and that hopelessness is indeed inciting a radicalisation of ‘left-behind’ places.

Taken together, foundational theories of hope, often informed by Southern experiences from the margins (Appadurai, Citation2013; Miyazaki, Citation2017), and a basic modelling of hope (Lybbert & Wydick, Citation2018; Swedberg, Citation2017) help postulating the generative mechanisms (combinations of aspirations and agency) and also the contradictory outcomes of hope. As indicated already in our summary of each outcome, the basic model of hope foremost helps to nuance the affective and agentic dimension of ‘left behindness’, albeit arguably in a highly simplified way. The model is also not universal: variations and overlapping layers exist within places and even among individuals. Nevertheless, we contend that this systematic approach for differentiating hope bares explanatory value in understanding why ‘left behindness’ must not automatically translate into popular and explicit forms of discontent. In the following section, we establish how the model of hope may explain also the emergence of quiet(er) and more mundane regional pathways in ‘left-behind’ places.

2.2. Mundane path development in ‘left-behind’ places

Just as different outcomes of hope contribute to the affective dimension of ‘left-behind’ places, they can also add to explaining practices of shaping industrial path development processes for an entire region; and effectively to manipulating the structural dimension of ‘left-behind’ places as well. This is not to say that there is a law-like causal relationship between hope and material and economic regional development. But it is to recognise that different constellations of hope – at both the individual and regional levels – can drive or inhibit different processes of path formation. Indeed, the literature on ‘left-behind’ places shares many overlaps with the evolutionary economic geography-cum-literature on regional path development (for a review, see Hassink et al., Citation2019). After all, regional lock-ins, understood as the inability to reinvent a path-dependent regional trajectory without exogeneous influence, are discussed as a causal driver for the phenomenon of ‘left-behind’ places (Sotarauta et al., Citation2023). In this section, we establish a non-deterministic approach to understanding path development in ‘left-behind’ places. In doing so, we add to explaining quiet articulations of ‘left behindness’ in and from the periphery and to understanding the role of future expectations in regional path development (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2019; Hassink et al., Citation2019).

Whereas much of the literature on regional path development has focused on core regions, recent literature has also investigated how new path development is both possible and inhibited in peripheral regions (Barratt & Klarin, Citation2022 Breul et al., Citation2021; Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2017; Nilsen et al., Citation2022). This literature suggests that the main factors for regional agency in new path development, Schumpeterian innovative entrepreneurship, institutional entrepreneurship and place-based leadership (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2019) tend to be barely available in the most peripheralised regions. In fact, it would all too often be cynical to claim that these factors can be straightforwardly extrapolated from experiences in core regions. Nilsen et al.’s (Citation2022) work on the varieties of peripheries and local agency illustrates this impasse for ‘left-behind’ places: on the one side, resilient regional service centres or locked-in specialised peripheries may maintain a certain degree of human capital, connectivity with external networks and institutional thickness. This allows them to tap into opportunity spaces and engage in processes of transformative path formation and reformation (cf. Breul et al., Citation2021). On the other side, deep peripheries such as vulnerable rural regions and locked-in vulnerable resource-based regions tend to be far more disadvantaged, ultimately leading to highly vulnerable and locked-in pathways. These peripheries are thereby often exposed to the ‘dark side of path development’ (Blažek et al., Citation2020) as trajectories of decline rather than any form of sustainable and emancipatory regional development may prevail.

This growing awareness of the distinction between core and periphery in path development is arguably even more important when it comes to large parts of the Global South. First, ongoing processes of structural decline due to uneven accumulation processes, combined with long histories of austerity, often mean that the dark sides of path development extend even beyond remote and resource-poor regions, as they also affect large parts of Southern cities (Schindler, Citation2017; Schindler et al., Citation2020). Second, and in terms of the severity of how ‘left behind’ is expressed relative to the Northern experience, Southern ‘left-behind’ places and their inhabitants are not only likely to be worse off relative to their regional counterparts, but they may even face acute threats to their most existential livelihoods for an extended period of time.

Attentive to these innate limitations of path development in ‘hyper-peripheral’ settings (Barratt & Klarin, Citation2022), the remainder of this section provides a non-deterministic approach for analysing hope and mundane path development in ‘left-behind’ places that is informed by experiences from the margins. Importantly, the approach is non-deterministic as it understands hope as a generative mechanism in a critical realist sense. While generative mechanisms are inherent to entities (in our case, different types of hope), their causal power stands for potentiality and contingency, rather than determinacy (Bhaskar, Citation1975; see also Sotarauta et al., Citation2023). Resonant with the already established basic model of hope, we postulate a typology of four regional pathways in ‘left-behind’ places: constructive–transformative, patient–stagnative, perseverant–retentive and destructive–disruptive pathways ().

Table 1. Hope and principal regional pathways in ‘left-behind’ places.

2.2.1. Constructive–transformative pathways

The constructive–transformative pathway is mostly associated with aspirational hope. It is constructive because it implies a substantial share of agents sees reason to carry on or align their practices despite deteriorating structural conditions in a ‘left-behind’ place. It is transformative because it relates to optimism about the place-based potential to engage in new path development and to eventually overcome structural limitations. As such, the constructive–transformative pathway aligns strongly with the mainstream literature on path development. It is constituted by practices of proactive asset mobilisation, for instance through processes of political ‘scale jumping’ (Cox, Citation1998) or couplings with global production networks and it may be an important factor to prevent a regional brain drain due to out-migration (Chamberlin et al., Citation2021). Further, it involves an openness among political leaders, local entrepreneurs, and common people to seek and capitalise on opportunity spaces against-all-odds (cf. Sotarauta et al., Citation2023 and the example of Lapland’s transition from pulp producer to eco-region). Taken together, the constructive–transformative pathway is, therefore, very unlikely to incite widespread repercussions towards core regions, nor within peripheries themselves.

2.2.2. Patient–stagnative pathway

The patient–stagnative pathway relates mainly to the prevalence of wishful hope. It is shaped by patience, as its underpinning optimistic fatalism motivates agents to speculate on extra-regional agents rather than their own agency to nudge a place-based trajectory into a more promising pathway. Therefore, it is also stagnative as it can lead to widespread passivity and negligence towards capitalising on potentially existing opportunity spaces, but also to acquiescence in face of fraudulent marginalisation (Hall et al., Citation2015). Patient–stagnative practices of inaction may indeed serve a stabilising function in cases of temporary structural downturn under the condition that the expected extra-regional support can be realised. However, it carries also the immanent risk to entrench regional ‘trajectories of decline’ which may include a path downgrading, contraction, or delocalisation in the long run (Blažek et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, and as long as wishful hope prevails to be widespread, the patient–stagnative pathway is, therefore, very unlikely to incite discontent on a short-term basis.

2.2.3. Perseverant–retentive pathways

The perseverant–retentive pathway relates to grit in ‘left-behind’ places. It is perseverant as it implies that agents continue to make an effort, even despite the bleak prospect of successful path reformation. It is further retentive as it involves crucial practices to prevent or at least alleviate a regional path downgrading, contraction or delocalisation. The perseverant–retentive pathway is constituted by practices of ‘hanging in’ – or in Dorward’s (Citation2009, p. 136) words: ‘strategies, which are concerned to maintain and protect current levels of wealth and welfare in the face of the threats of stresses and shocks’. Grit and related perseverant–retentive practices add in this way to maintaining a crucial regional asset base (e.g., by preventing out-migration of human capital and contraction of regional innovation systems) and extra-regional connections (e.g., by providing sudden decouplings from production networks). Both can allow regional actors to capitalise on unexpected opportunity spaces for new path development (cf. Hulke et al., Citation2022, and their example of agricultural commercialisation in Namibia amid the COVID pandemic). Taken together, the perseverant–retentive pathway is, therefore, more likely to incite discontent. After all, grit can be quite gruelling, on both individual and collective levels. Nevertheless, even the perseverant–retentive pathway is overall still unlikely to drive discontent that is explicitly articulated if determinist pessimism prevails.

2.2.4. Destructive–disruptive

The destructive–disruptive pathway relates mainly to victimisation and it is a prominent feature of some of the most popular and noisy ‘left-behind’ places. The pathway is destructive as its underpinning pessimist–fatalism justifies individual and coordinated desperate actions under the premise that there is nothing to lose. It is further disruptive, as the explosive potential of victimisation and desperate action may make an evident trajectory of decline intolerable for both place-based and extra-regional institutions. For instance, the uprise of the French Gilet Jaunes relied on self-categorising as ‘victims of inequality’ to mobilising violent and highly destructive protests all over the country (Jetten et al., Citation2020; Morales et al., Citation2020). The same applies for the mobilisation of Indian farmers who opposed the liberalisation of agricultural policies since 2020 (Baviskar & Levien, Citation2021). As Indian policy reforms existentially threatened agrarian livelihoods, desperate, nothing-to-lose measures included self-destructive action such as encircling Delhi for months, whilst disregarding the cultivation of farms in the periphery. Surrendering and the immediate destruction of regional assets and extra-regional networks can hence be a constituting element of destructive–disruptive pathways in ‘left-behind’ regions. Destructive–disruptive pathways are accordingly likely to drive noisy discontent.

In sum, our typology of path development in ‘left-behind’ places establishes two points. First, it relates path development non-deterministically to different modes of hope. Although hope is naturally grounded in past experiences and the structural conditions in place (Steen, Citation2016), it is also complemented by the contingency of the totality of per se uncertain and subjective future expectations. This implies that all structural conditions can principally lead to one or another configuration of dominant types of hope. As such, our typology is not about law-like principles positing that certain structural conditions determine a definitive set of hopes, and that hope determines either quiet or noisy forms of discontent. Rather, it is about postulating generative mechanisms which may fuel one tendency or another. Second, the typology further enables statements about more likely or unlikely explicit repercussions of being ‘left behind’. Whereas a dominance of victimisation may indeed easily drive geographies of discontent, the alternative modes of hope and their related pathways are more likely to drive mundane and quieter forms of path development.

3. RESEARCH REGION, DATA AND METHODS

To illustrate our conceptual arguments, we use the case of Zambia’s Western Province. We respond to three research questions: How is ‘left behindness’ in Western Province expressed? What constitutes dominant modes of hope in Western Province? Which pathways are related to these hopes?

3.1. Research region

Zambia is one of the world’s poorest countries and is characterised by a sharp socio-economic divide between metropolitan core regions vis-à-vis their rural peripheries. This divide has been exacerbated during the commodities boom in the 2000s and an ensuing macro-economic crisis (Aguirre Unceta, Citation2021; Chikalipah & Makina, Citation2019). Whereas these macro-trends have driven a general tendency towards leaving Zambia’s rural peripheries behind Zambia’s core regions (Lusaka and the Copperbelt region) (Cheelo et al., Citation2022), our research region, Western Province, is an exceptionally ‘left-behind’ place for three reasons.

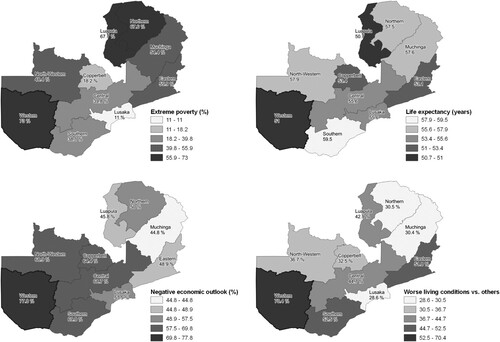

First, Western Province is Zambia’s most rural and marginalised region. Structurally, the region suffers from enduring poverty, and its residents have a much lower life expectancy than in other regions. In fact, and contrary to Zambia’s urbanising core regions, Western Province is undergoing ruralisation processes. Between 2004 and 2015, the share of urban population decreased from 15.0% to 12.5%.Footnote2 These structural factors are also emphasised in more subjective assessments. According to the Afrobarometer, people from Western Province are the most pessimistic about Zambia’s future development and they evaluate their living conditions relative to others to be the worst (). Already on a macro-level, structural and affective factors illustrate thereby how Western Province is not only lacking behind in relation to runaway regions such as Lusaka and the Copperbelt but also is lacking behind rural regions with similar features.

Figure 2. Zambia's spatial divide into core and periphery regions along structural (upper maps) and affective dimensions (lower maps).

Sources: Data are from the Zambia Population and Housing Census Data 2015 and Afrobarometer 2017.

Second, Western Province is the main site of the contested Barotseland question, a conflict that has loomed already since the Barotseland Agreement from 1964 between the secessionist Lozi kingdom and Zambia’s national government was abrogated. Today, Barotseland activists and elected representatives continue to demand recognition as a sovereign state which goes hand in hand with contentious criticism about Western Province’s systematic exclusion from basic development initiatives, infrastructure provisioning and political decision-making (Englebert, Citation2005; Noyoo, Citation2014).

Third, and embedded into the foregoing trends, an acute food crisis in 2018–19 has recently escalated the already severe conditions. The poorest rainfalls in Zambia’s history paired with flash floods existentially endangered the livelihoods of rural residents. By March 2020, 77% of Western Province’s population was affected by food shortages or severe hunger.Footnote3 However, emergency food aid was distributed insufficiently due to a lack of infrastructure, but also due to the region’s difficult political positioning vis-à-vis the central government (Banda & Mulenga, Citation2019). Although representatives from Western Province alerted the National Assembly of Zambia that ‘people are dying of hunger while others are eating grass’,Footnote4 calls for immediate food relief were rebuffed due to suspicions of covert politicisation of the Barotseland question.

3.2. Data and methods

Our study draws from two datasets. The first consists of quantitative household survey data collected in June 2019. The survey questionnaire served to measure how ‘left behindness’ is structurally and emotionally expressed among a representative sample of rural people of Western Province.Footnote5 The questionnaire included structural indicators such as basic demographic and socio-economic data. Additionally, it addressed affective and more subjective indicators. These related especially to assessments of future fears and aspirations as well as future-related agency. Following a two-staged stratified random sampling process, four districts in Western Province (Shang’ombo, Sioma, Shesheke and Mwandi) were sampled by a systematic grid sampling technique. The survey sampled a total of 425 households.Footnote6

The second dataset consists of qualitative interviews from February 2021. The interviews served to contextualise the relationship between different hopes and emergent regional pathways which can only be qualitatively assessed (Steen, Citation2016). In total, we draw from 12 semi-structured interviews evenly distributed among respondents from the survey regions Sioma and Sesheke. Although we could not revisit former household survey respondents, we purposefully selected interview respondents along stratifying indicators such as age, sex and economic livelihoods (). All interviews were held in the vernacular language (Lozi) and translated into Bemba or English by local interlocutors. For the ensuing content analysis, the interviews were translated and transcribed into English.

4. RESULTS

We use the three research questions as structuring elements to present the results of our study.

4.1. How is ‘left behindness’ in Western Province expressed?

In this section, we differentiate how the pernicious – and in the most extreme cases life-threatening – combination of persistent marginalisation and an immediate food crisis constitute a severe state of being ‘left behind’ among people in Western Province. Using our first dataset, which includes information from 425 survey respondents, we distinguish between structural indicators (mainly material and objectifiable conditions) and affective indicators (immaterial and subjective conditions).

Regarding structural indicators, summarises how enduring marginalisation and the recent food crisis shaped some of the most existential rural livelihoods. While Zambian census data estimated the share of extreme poverty in Western Province to be around 73% in 2015,Footnote7 our seasonal data from 2018–19 suggest that the share of extreme poverty spiked temporarily upwards to 96.1%. This is mainly because about half of all households (46.6%) reported any net income after losing their investments in agricultural inputs, livestock and labour amid the drought. Aligned with this, some of the most existential household assets were structurally lacking. Only a fourth of all households had access to electricity (25.8%), less than half had access to safe drinking water (39.3%) and in about a third of all households no household member finished formal education beyond primary school (30.3%). Finally, the region’s ‘left behindness’ was expressed through lacking success in mobilising external assets amid the food crisis. Although about a third of all households benefitted from some form of external support, such as food or cash, only 6.3% were directly supported by the Zambian government. Most households relied on support mobilised through social networks and remittances of proximate friends, relatives, and neighbours (26.9%). In the reversal, roughly two-thirds of all households received no external support at all (65.7%).

Table 2. Structural indicators of ‘left-behindness’ among households from Western Province (n = 425).

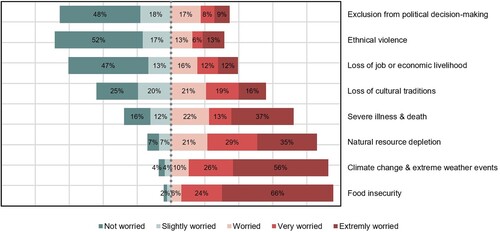

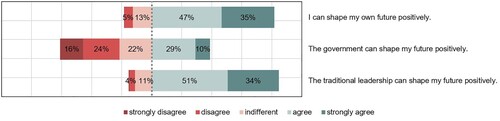

Regarding affective indicators, summarises the multiplicity of worries about the future expressed amid the dire conditions. Importantly, more economic, cultural and political issues such as exclusion from political decision-making, the decline of economic livelihoods, ethnical violence and the loss of cultural traditions were rarely perceived as imminent threats. Rather, some of the most fundamental and sometimes life-threatening worries such as food insecurity, weather events, natural resource depletion and serious illness were raised frequently, oftentimes by extreme degrees. Resonant with the lack of external support, further substantiates, that solutions for these existential worries were typically associated with intra- rather than extra-regional actors. Asked about who could best shape their future positively, respondents trusted much more in themselves and their traditional leadership than in the national government.

Figure 4. Confidence in the ability of regional and extra-regional actors to shape the future among households in Western Province (n = 425).

In sum, our data highlights how enduring economic and political marginalisation combined with the lacking ability to mobilise extra-regional support amid a crisis event exacerbated the already fragile structural conditions that were in place. Although the structural determinants of ‘left behindness’ are severe, our data provides, however, no evidence for explicit affect which could explain noisy geographies of discontent. On the contrary, most respondents expressed being most concerned with the tangible and existential issues and solutions in place.

4.2. What constitutes dominant modes of hope in Western Province?

Against the background of the severity of ‘left behindness’ in the region, our household data on future aspirations and agency rejects assumptions that structural marginalisation automatically translates into perceiving of hopeless future. A categorisation of future aspirations and agency derived from self-reported assessments and applied to the basic model of hopeFootnote8 helps to map out the dominant modes of hope (). While all four combinations of aspirations and agency were evident, derived modes of hope were distributed unevenly. Grit was the most frequent model outcome (44.0%). The prominence of grit suggests that despite widespread pessimism a certain self-determination was conserved. Aspirational hope was the second most frequent model outcome with 38.1%. Aspirational hope complemented therefore the pessimist self-determinism of grit with substantial evidence for optimist self-determination. Victimisation was a less frequent aspirational outcome (15.5%). Pessimist fatalism was hence also far less evident than one would assume given the severity of ‘left behindness’ in the region. Finally, wishful hope was the least frequent model result (2.4%).

Figure 5. Dominant modes of hope in Western Province, Zambia (n = 425).

Source: Authors partly adapted from Lybbert and Wydick (Citation2018).

The descriptive results on dominant modes of hope can be further analysed regarding its constituent factors. Univariate tests of independence suggest that the distribution of dominant types of hope was significantly related to several household and household head characteristics (). Regarding household characteristics, respondents from households with income sources outside of the primary sector, with improved housing conditions, and from less geographically remote regions were significantly more likely to express aspirational hope and more unlikely to express victimisation. While the relationship to grit was less clear for housing conditions, preferential income sources and a household’s geography also relate to a more unlikely expression of grit. Given its rarity, the effects on wishful hope cannot be further detailed. Regarding individual characteristics, dominant modes of hope were independent of the sex and education of the survey respondents. However, age had a significant effect on hope. Whereas the older generation tended to be divided between relatively high aspirational hope and victimisation, the younger generation tended more toward grit.

Table 3. Dependencies between structural factors and aspiration outcomes.

Taken together, the data foremost suggests a surprising persistence hope and does so against-all-odds, that are the structural factors in place. Rather than expressing helplessness in form of wishful hope or victimisation, most respondents indicated grit or aspirational hope. Moreover, hope was not distributed randomly. Especially respondents from better-off households tended to be more hopeful and to perceive higher agency towards the future.

4.3. Which pathways are related to dominant modes of hope in Western Province?

Our qualitative interview data suggest that people in Western Province involve in path-formation practices which were characterised by their mundanity. In doing so, their constituting hopes and practices were unlikely to incite popular geographies of discontent. Based on our earlier conceptualisation of regional pathways in ‘left-behind’ places, we discuss the evidence for each pathway. A summary of the interview sample and results is provided ().Footnote9

Table 4. Qualitative interview sample and coding overview.

Perseverant–retentive practices underpinned by grit were most prominently addressed in the interviews. Albeit making their dire expectations towards the future explicit, interviewees highlighted the importance of ‘hanging in’ and continuing their established livelihood activities. Statements such as ‘The future that is possible for the household is farming and with the hope of expanding the activities in future’ (HH#2) indicate not only a certain modesty of aspirations but also the hope that stubbornness and perseverance may eventually lead to a somehow better future. A similar tendency is also highlighted by statements such as ‘Our future is to do business and farming provided we have access to a water pump to help us with the gardening’ (HH#5). Rather than aspiring or demanding a disruptive future, the interviewee gave priority to mundane, place-based solutions such as a water pump. Acknowledging these perseverant–retentive practices for their mundane and place-based nature is quite important. In their totality, they can stabilise mundane regional pathways which capitalise on assets and actions in place.

Constructive–transformative practices underpinned by aspirational hope came up less frequently in the interviews. Although our qualitative sample included expressions of aspirational hope, aspirations and future-oriented practices were characterised by a similar mundanity despite indicating transformative ambition. Statements such as:

I believe the household has a bright future because through hard work things are going to be better. … If I can start a business, I will be able to take some money to the bank for savings and we will have good meals in the household

(HH#1)

If I had a market and sell some things such as relish on the roadside then the future would be better because transport for going to Katima and Shesheke to do business is very expensive and you find that little or no profit is made.

(HH#11)

Patient–stagnative practices underpinned by wishful hope were more frequently raised than our mapping of hope suggests. While statements such as:

We have a bright future. … The future depends on God. He helps us to live well, to find food and to live well with others

During the drought, the elephants came and destroyed everything, I called the ZAWA [Zambia Wildlife Authority] officers and there is nothing they did. All they did is watch and do nothing and then they went back. If they can change that and feel pity for us, and do something for us, then we can prosper

(HH#12)

Destructive–disruptive practices underpinned by victimisation were rarely explicitly raised but reflected by pessimist–fatalist statements. Statements such as ‘We are depending on farming. Now there is an issue of drought and human–animal conflicts where if we cultivate the elephants come and destroy our fields. Now how can our future go somewhere?’ (HH#4) shows how some interviewees explicitly perceived to have no agency over an overall dire future. As such, they also implicitly put the continuation of most existential livelihoods in question. Further, statements such as:

I have no bright future because things are bad, back then things were a bit okay, but now it’s worse. There is nothing to do. … If we had someone to help we could live better, but now there is no one to help

(HH#10)

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This article contributed to stress testing the spatial imaginary of ‘left-behind’ places by adding a perspective that goes beyond the predominance of Northern, viral, and noisy case studies. In doing so, the article added to empirically broadening the understanding of how ‘left behindness’ is expressed in different peripheries, but it also called for conceptually emphasising the role of hope and mundane path development in explaining quiet rather than noisy responses to severe states of ‘left behindness’.

Empirically, the case study of Western Province highlighted how the combination of enduring marginalisation along multiple structural dimensions and a recent food crisis have created a regional condition of structural decline, loss of existential livelihoods, and lack of extra-regional support in the midst of a life-threatening crisis for many – or in other words: a severe state of being ‘left behind’. However, and contrary to the mainstream assumption, the analysis of representative survey data suggested that severe and escalating structural factors typically associated with ‘left-behind’ places did not incite affective geographies of discontent. Rather, a focus on the role of prevailing hope and related practices of mundane path development underlined two tendencies. First, the analysis of quantitative survey data suggested that affective reactions to the structural realities in Western Province included existential worries over health- and life-threatening hunger and starvation rather than resentment about purely economic or political marginalisation that is explicitly directed to runaway regions. In other words, in face of the severity and acuteness of deteriorating structural conditions, maintenance of some of the most existential livelihoods at present and in place arguably left little attention and resources to articulate effective forms of popular and noisy discontent targeted toward the future and runaway regions/actors. Second, the analysis of qualitative interview data added to this that future-oriented practices showed no signs of constituting any form of noisy discontent. Most interviewees indicated pursuing a range of actions and inactions fuelled by self-determined and fatalist as well as optimist and pessimist modes of hope. Despite the contingent variety and of these practices, the most remarkable observation was that they all tended towards maintaining or only slightly transforming already existent and per se mundane regional pathways (e.g., frugal improvement of available assets such as a household’s farm, maintenance of urban–rural remittances networks via the extended family). Rather than imagining or demanding transformational or disruptive change (including viral forms of discontent), most interviewees saw more reason and agency in mundane forms of path development.

Importantly, these empirical results must be considered for their limitations. Our mixed-methods approach allowed us to quantitatively investigate a representative sample of Western Province’s rural population which was especially supportive to trace how ‘left behindness’ is expressed structurally and affectively among common people. However, this also carried two major risks. First, the analysis of affective and subjective factors such as hope, future, aspirations, and agency through quantitative measures and a basic modelling of hope risked overgeneralisation of naturally complex realities (first and second research question). Other studies on the affective dimensions of ‘left-behind’ places – or also on regional path development – typically propose qualitative rather than quantitative methodological approaches (Hassink et al., Citation2019; Steen, Citation2016). Second, our approach (all research questions) risked to underestimating the role of exalted individuals such as emergent entrepreneurs, established elites, or political actors who are typically understood as pivotal actors for place-based leadership, scale-jumping processes and change agency in path development (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2019; Jolly et al., Citation2020). A purposeful sampling and qualitative in-depth methods to better emphasise the role of such regional pacemakers could enable more nuanced and potentially contradictory insights on emergent pathways in Western Province.

Conceptually, our work contributed to scrutinising the spatial imaginary of ‘left-behind’ places by linking literature on hope and regional path development. This helped to establish an important antithesis relative to some of the most popular literature on ‘left-behind’ places. Our conceptualisation of hope and mundane path development questioned an important and usually taken-for-granted qualifier of ‘left-behind’ places. Namely, the assumption that ‘left-behind’ places necessarily express their discontent through clearly articulated, potentially organised and per se noisy backlashes. Acknowledging the complexity of hope and its role in shaping mundane path development, calls for expanding the notion of ‘left-behind’ places to also include quiet(er) places that see no use or have no agency to articulate their discontent more virally and effectively, even if life-threatening structural conditions prevail. Considering such types of ‘left-behind’ places beyond the most resonant set of noisy cases is not trivial. After all, a well-established strand of literature on uneven spatial development at the global margins of today and in history (cf. Amin, Citation2010; Escobar, Citation2011; Obeng-Odoom, Citation2020), should remind us that many of the world’s peripheries tend to be quite silent, even under the enduring experience of abysmal structural conditions. Although the spatial imaginary of ‘left-behind’ places allures for its potential to inform new foundational theorisations of uneven development (MacKinnon et al., Citation2021), the same imaginary can only serve its purpose if the diversity of expressions and responses to ‘left behindness’ are considered for cases in the North and the South. Perspectives from the (extreme) margins can, therefore, contribute to a shift of discourse about one ‘left-behind’ periphery to be more productively informed by the actually existing diversity of peripheries.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Grit should not be confused with automatic resilience. This is because grit may not be sufficient to maintain or improve the condition of an individual or region in the face of a shock. It may simply be the only non-fatalist response available, even if adverse outcomes cannot be completely prevented (for a discussion of regional resilience, see also Boschma, Citation2015).

2. Data are derived from Zambia Population and Housing Census Data 2004 and 2015.

3. The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification monitors food security and food crises in the Global South. For more information, see www.ipcinfo.org

4. Mundia Ndalamei, national assembly representative of Sikongo, on 8 October 2019. For the full transcript, see https://www.parliament.gov.zm/node/8976

5. All respondents provided informed consent for this study. Informed consent was based on a detailed written description of the purpose of the survey and required respondents to verbally agree to participate in the study. The description stated that the anonymity of all respondents would be protected and that aggregated results would be disseminated after data collection and cleaning.

6. For the survey questionnaire and basic descriptive data, see a stable DOI at https://doi.org/10.5880/TRR228DB.11

7. Share of people living with less than US$1.90/day (in 2019 nominal price, US$2.16).

8. Our dichotomous modelling approach bares the caveat of crude simplification despite the discussed complexity of hope. Nevertheless, we contend that a mapping of principal modes of hope based on self-assessments serves our cause of identifying the diversity of major outcomes. To do so, we reclassified the survey respondents’ Likert-scale evaluations of their future perceptions (‘My future is bright’) and agency (‘My future depends on me’). Only explicitly positive self-assessments (agree, strongly agree) were classified as indications of positive future perceptions or high agency. Negative or indifferent statements (strongly disagree, disagree, indifferent) were categorised as negative/low outcomes.

9. Due to the limited scope of 12 qualitative interviews, we cannot reasonably link this dataset to the quantitative data. Therefore, the qualitative findings are subject to the limitation that they are not representative of the region as a whole. However, we have cross-validated the data with our regional interviewees and research assistants in terms of the most common practices for responding to the dire conditions during the data collection period.

REFERENCES

- Aguirre Unceta, R. (2021). The economic and social impact of mining-resources exploitation in Zambia. Resources Policy, 74, 102242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102242

- Amin, S. (2010). Global history: A view from the south. Pambazuka.

- Appadurai, A. (2013). The future as cultural fact. Verso.

- Aring, M., Reichardt, O., Katjizeu, E. M., Luyanda, B., & Hulke, C. (2021). Collective capacity to aspire? Aspirations and livelihood strategies in the Zambezi region, Namibia. European Journal of Development Research, 33, 933–950. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00412-1

- Banda, A., & Mulenga, B. (2019). Food security status report. Indaba Agricultural Policy Research Institute.

- Barratt, T., & Klarin, A. (2022). Hyper-peripheral regional evolution: The ‘long histories’ of the Pilbara and Buryatia. Geographical Research, 60(2), 286–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12517

- Baviskar, A., & Levien, M. (2021). Farmers’ protests in India: Introduction to the JPS forum. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 48(7), 1341–1355. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2021.1998002

- Bhaskar, R. (1975). A realist theory of science. Leeds Books.

- Blažek, J., Květoň, V., Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., & Trippl, M. (2020). The dark side of regional industrial path development: Towards a typology of trajectories of decline. European Planning Studies, 28(8), 1455–1473. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1685466

- Bloem, J. R., Boughton, D., Htoo, K., Hein, A., & Payongayong, E. (2018). Measuring hope: A quantitative approach with validation in rural Myanmar. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(11), 2078–2094. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1385764

- Boschma, R. (2015). Towards an evolutionary perspective on regional resilience. Regional Studies, 49(5), 733–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.959481

- Breul, M., Hulke, C., & Kalvelage, L. (2021). Path formation and reformation: Studying the variegated consequences of path creation for regional development. Economic Geography, 97(3), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.1922277

- Chamberlin, J., Ramos, C., & Abay, K. (2021). Do more vibrant rural areas have lower rates of youth out-migration? Evidence from Zambia. The European Journal of Development Research, 33(4), 951–979. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00404-1

- Cheelo, C., Hinfelaar, M., & Ndulo, M. (2022). Inequality in Zambia. Routledge.

- Chikalipah, S., & Makina, D. (2019). Economic growth and human development: Evidence from Zambia. Sustainable Development, 27(6), 1023–1033. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1953

- Connell, R. (2014). Using southern theory: Decolonizing social thought in theory, research and application. Planning Theory, 13(2), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095213499216

- Cox, K. R. (1998). Spaces of dependence, spaces of engagement and the politics of scale, or: Looking for local politics. Political Geography, 17(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(97)00048-6

- De Ruyter, A., Martin, R., & Tyler, P. (2021). Geographies of discontent: Sources, manifestations and consequences. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 14(3), 381–393. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab025

- Díaz-Lanchas, J., Sojka, A., & Di Pietro, F. (2021). Of losers and laggards: The interplay of material conditions and individual perceptions in the shaping of EU discontent. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 14(3), 395–415. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab022

- Dijkstra, L., Poelman, H., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2020). The geography of EU discontent. Regional Studies, 54(6), 737–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1654603

- Dorward, A. (2009). Integrating contested aspirations, processes and policy: Development as hanging in, stepping up and stepping out. Development Policy Review, 27(2), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2009.00439.x

- Edwards, S. (2010). Left behind: Latin America and the false promise of populism. University of Chicago Press.

- Englebert, P. (2005). Compliance and defiance to national integration in Barotseland and Casamance. Africa Spectrum, 40(1), 29–59.

- Escobar, A. (2011). Encountering development. Princeton University Press.

- Fudge, M., Ogier, E., & Alexander, K. A. (2021). Emerging functions of the wellbeing concept in regional development scholarship: A review. Environmental Science & Policy, 115, 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.10.005

- Gordon, I. R. (2018). In what sense left behind by globalisation? Looking for a less reductionist geography of the populist surge in Europe. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx028

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2019). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Hage, G. (2003). Against paranoid nationalism – Searching for hope in a shrinking society. Pluto.

- Hall, R., Edelman, M., Borras Jr, S. M., Scoones, I., White, B., & Wolford, W. (2015). Resistance, acquiescence or incorporation? An introduction to land grabbing and political reactions ‘from below’. Journal of Peasant Studies, 42(3–4), 467–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2015.1036746

- Hansen, T. (2021). The foundational economy and regional development. Regional Studies, 56(6), 1033–1042. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1939860

- Hassink, R., Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2019). Towards a comprehensive understanding of new regional industrial path development. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1636–1645. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Hulke, C., Kalvelage, L., Kairu, J., Revilla Diez, J., & Rutina, L. (2022). Navigating through the storm: Conservancies as local institutions for regional resilience in Zambezi, Namibia. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 15(2), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsac001

- Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2017). Exogenously Led and policy-supported New path development in peripheral regions: Analytical and synthetic routes. Economic Geography, 93(5), 436–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2016.1154443

- Jetten, J., Mols, F., & Selvanathan, H. P. (2020). How economic inequality fuels the rise and persistence of the Yellow Vest Movement. International Review of Social Psychology, 33(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.356

- Jolly, S., Grillitsch, M., & Hansen, T. (2020). Agency and actors in regional industrial path development. A framework and longitudinal analysis. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 111, 176–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.013

- Kleist, N., & Jansen, S. (2016). Introduction: Hope over time – Crisis, immobility and future-making. History and Anthropology, 27(4), 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2016.1207636

- Koeppen, L., Ballas, D., Edzes, A., & Koster, S. (2021). Places that don’t matter or people that don’t matter? A multilevel modelling approach to the analysis of the geographies of discontent. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 13(2), 221–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12384

- Lee, N. (2019). Inclusive growth in cities: A sympathetic critique. Regional Studies, 53(3), 424–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1476753

- Lenzi, C., & Perucca, G. (2021). People or places that don’t matter? Individual and contextual determinants of the geography of discontent. Economic Geography, 97(5), 415–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.1973419

- Lybbert, T. J., & Wydick, B. (2018). Poverty, aspirations, and the economics of hope. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 66(4), 709–753. https://doi.org/10.1086/696968

- MacKinnon, D., Kempton, L., O’Brien, P., Ormerod, E., Pike, A., & Tomaney, J. (2021). Reframing urban and regional ‘development’ for ‘left behind’ places. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 15(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab034

- Mayer, H., Tschumi, P., Perren, R., Seidl, I., Winiger, A., & Wirth, S. (2021). How do social innovations contribute to growth-independent territorial development? Case studies from a Swiss mountain region. DIE ERDE – Journal of the Geographical Society of Berlin, 152(4), 218–231. https://doi.org/10.12854/erde-2021-592

- Miyazaki, H. (2017). The economy of hope: An introduction. In H. Miyazaki, & R. Swedberg (Eds.), The economy of hope (pp. 1–36). University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Morales, A., Ionescu, O., Guegan, J., & Tavani, J. L. (2020). The importance of negative emotions toward the French Government in the Yellow Vest Movement. International Review of Social Psychology, 33(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.373

- Morisson, A., & Mayer, H. (2021). An agent of change against all odds? The case of ledger in Vierzon. France. Local Economy, 36(5), 430–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/02690942211052014

- Nilsen, T., Grillitsch, M., & Hauge, A. (2022). Varieties of periphery and local agency in regional development. Regional Studies 57(4), 749–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2106364

- Noyoo, N. (2014). Indigenous systems of governance and post-colonial Africa: The case of Barotseland.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. (2019). The intellectual marginalisation of Africa. African Identities, 17(3–4), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2019.1667223

- Obeng-Odoom, F. (2020). Property, institutions, and social stratification in Africa. Cambridge University Press.

- Oldfield, S., & Greyling, S. (2015). Waiting for the state: A politics of housing in South Africa. Environment and Planning A, 47(5), 1100–1112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15592309

- Peck, J. (2012) Austerity urbanism. City, 16(6), 626–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2012.734071

- Pike, A. (2022). Coping with deindustrialization in the global north and south. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 26(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2020.1730225

- Pike, A., Béal, V., Cauchi-Duval, N., Franklin, R., Kinossian, N., Lang, T., Leibert, T., MacKinnon, D., Rousseau, M., Royer, J., Servillo, L., Tomaney, J., & Velthuis, S. (2023). ‘Left behind places’: A geographical etymology. Regional Studies, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2023.2167972.

- Pike, A., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2007). What kind of local and regional development and for whom? Regional Studies, 41(9), 1253–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701543355

- Pike, A., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2017). Shifting horizons in local and regional development. Regional Studies, 51(1), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1158802

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx024

- Saab, R., Spears, R., Tausch, N., & Sasse, J. (2016). Predicting aggressive collective action based on the efficacy of peaceful and aggressive actions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 46(5), 529–543. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2193

- Schindler, S. (2017). Towards a paradigm of Southern urbanism. City, 21(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2016.1263494

- Schindler, S., Gillespie, T., Banks, N., Bayırbağ, M. K., Burte, H., Kanai, J. M., & Sami, N. (2020). Deindustrialization in cities of the Global South. Area Development and Policy, 5(3), 283–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2020.1725393

- Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 249–275. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01

- Sotarauta, M., Kurikka, H., & Kolehmainen, J. (2023). Change agency and path development in peripheral regions: From pulp production towards eco-industry in Lapland. European Planning Studies, 31(2), 348–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2022.2054659

- Stasik, M., Hänsch, V., & Mains, D. (2020). Temporalities of waiting in Africa. Critical African Studies, 12(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681392.2020.1717361

- Steen, M. (2016). Reconsidering path creation in economic geography: Aspects of agency, temporality and methods. European Planning Studies, 24(9), 1605–1622. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1204427

- Swedberg, R. (2017). A sociological approach to hope in the economy. In H. Miyazaki, & R. Swedberg (Eds.), The economy of hope (pp. 37–50). University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Tomaney, J., & Pike, A. (2020). Levelling up? The Political Quarterly, 91(1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12834

- Ulrich-Schad, J. D., & Duncan, C. M. (2018). People and places left behind: Work, culture and politics in the rural United States. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 45(1), 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1410702