ABSTRACT

In ‘Alfred Nobel’s Karlskoga’, Sweden, the municipality has placed its most famous former resident at the heart of its economic development strategy. Through an in-depth qualitative case study, we examine the tensions and complexities surrounding this process and fill an existing research gap around personality-based place branding for regional development purposes. The findings suggest that even with a world-famous figure as talisman, personality-based place branding is a complex endeavour where old rivalries, tightknit social structures and economic dependencies makes us question – is it even possible to build a brand that is both inclusive and truly representational of a place?

1. INTRODUCTION

At first glance, it would make the perfect place-branding strategy: drawing on the local heritage of world-famous inventor Alfred Nobel to brand Karlskoga – a small industrial town in central Sweden that was his official home at the time of his death. Perhaps particularly so, as the strategy of personality-associated place branding is argued to be especially useful for smaller cities (Ashworth, Citation2010). Behind the brand ‘Alfred Nobel’s Karlskoga’ (ANK) is a three-pronged regional development strategy to attract tourists, business and residents to Karlskoga in order to halt population decline and replenish the local pool of skilled labour. However, the ambitions behind ANK will be difficult to realise for the stakeholders involved – as this paper will demonstrate – for several reasons.

The choice of Nobel as a branding talisman, or Alfred Nobel, as the ANK enthusiasts are quick to point out the importance of using his full name – to avoid being mixed-up with the Nobel Prize and the Nobel Foundation – is based on a meandering logic highlighting certain values of the man’s heritage and connection to the local area, while actively ignoring and dismissing other and perhaps more problematic dimensions of the Nobel pedigree in Karlskoga. Furthermore, recent scholarship (Björner & Aronsson, Citation2022; Jernsand, Citation2016; Zenker & Erfgren, Citation2014) has pointed out that successful place branding is seldom built around a central organisation conveying a top-down message to the masses. Instead, an inclusive process is recommended whereby residents and consumers of brands are seen as co-creators and in dialogue with the branding organisation, while at the same time acknowledging the diversity and multidimensional aspects of place (Andersson & James, Citation2018). Therefore, at the core of this paper lies the question: How inclusive and tenable is the place-branding strategy of ANK when seen from a wider regional development perspective?

Often described as the ambition of governments to attract people and money to a city, region or nation (Kavaratzis et al., Citation2015), place branding has become common practice amongst governments to develop and circulate certain images of the quality of life, location and convenience of the places that they represent. Four main instruments have been identified for place branding: (1) signature buildings and urban design, that is, the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain; (2) event hallmarking, that is, the Eurovision Song Contest; (3) policy boosterism, that is, the ‘greenest city’; and (4) personality association, that is, Rotterdam as the ‘City of Erasmus’ (Ashworth, Citation2009, Citation2010; Boland & McKay, Citation2021; McCann, Citation2013). Place branding involves leveraging ‘softer intangible assets for regional resilience and growth’ (Castaldi & Mendonça, Citation2022, p. 177).

Personality association, which is the focus of this paper, implies that ‘places associate themselves with a named individual in the hope that the necessarily unique qualities of the individual are transferred by association to the place’ (Ashworth, Citation2009, p. 11). It is rather under-researched compared with other place-branding instruments (Ashworth, Citation2010; Boland & McKay, Citation2021), and especially in relation to inclusive place branding (Jernsand, Citation2016). We were motivated to conduct research into this issue, guided by a broad interest in finding out how personality-based place branding can be leveraged as part of an inclusive regional development strategy.

The case we have chosen with which to unpack this topic is one not yet reported, and likely not well known to an international readership. The ANK brand is built around the historical legacy of Alfred Nobel and his home in Karlskoga, and the contemporary spirit of innovation and industry, which is promoted by Swedish regional development policies (Grundel, Citation2022). Karlskoga is also the home of the historic arms company Bofors, which still maintains a strong physical and economic presence in the town, having been the single largest private employer for centuries. However, since the late 1970s, Karlskoga has experienced a significant drop in population, from a high of around 40,000 residents to approximately 27,000 people today. Also, in the surrounding region of Bergslagen – historically dependent on mining and iron and steel works – an overall economic stagnation has taken place causing factory closings, unemployment and out-migration (Lundmark & Hedfeldt, Citation2015). Thereby, we engage with contemporary discussions within the regional studies literature around industrial districts, de- and post-industrialisation, and economic restructuring (Beer et al., Citation2023; Sunley et al., Citation2021; Tomlinson & Robert Branston, Citation2018). Specifically, we focus on the role of place branding as a strategy that local and regional governments enact as part of their wider regional development efforts.

2. THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS

Hall and Hubbard (Citation1996) identify place branding as ‘a set of specific policies and strategies deployed in policy-making by local governments and through which promotional activities are incorporated alongside planning and physical developments’ (Andersson, Citation2015, p. 34). It is agreed that place-branding research blossomed in the last 20 years, moreover from different disciplinary perspectives (Kavaratzis et al., Citation2015). The place-branding concept is criticised for being under-theorised (Andersson, Citation2014b) and non-inclusive (Jernsand, Citation2016), providing an additional motivation for this contribution.

Emergent in a context of ‘urban entrepreneurialism’ (Harvey, Citation1989) almost all place-branding strategies share universal goals of attracting mobile human and/or financial capital, while maintaining and keeping existing inhabitants, companies and flows of tourists happy and content with their place of residence, business and visit (Andersson, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Kavaratzis et al., Citation2015). As such, place branding is often organised into ‘internal’ and ‘external’ target groups (Pike, Citation2009; Stålnacke & Andersson, Citation2014), where the external communication is directed to audiences outside the place being branded, and internal communication addresses the existing population. However, no place-branding campaign can be successful without being firmly embedded and rooted in the physical and socio-economic structures of a place (Ashworth, Citation2009): externally focused campaigns must be reflected in the relationship between the local population and the place, to render legitimacy and credibility to the place brand itself (Andersson, Citation2014a; Kavaratzis et al., Citation2015). Internally oriented place branding must resonate with the local populations’ self-identity and recognition of themselves, and with the place in question (McCann, Citation2013; Pike, Citation2009). For instance, if a place is perceived as dangerous due to a high crime rate, no place-branding strategy can wash away that identity without also being accompanied by effective crime prevention policies and interventions.

We also contribute to advancing place-branding scholarship through considering a smaller peripheral city-region rather than large cities and capitals (Andersson, Citation2014b; Björner & Aronsson, Citation2022). There has been an emphasis within place-branding scholarship, especially that conducted in the Nordics, on networked and participatory approaches to place branding, which engage the community of a place to generate inclusive place brands (Björner & Aronsson, Citation2022; Cassinger et al., Citation2021). This has in turn inspired scholars and practitioners to engage resident communities and brand consumers as active co-creators of place brands (Björner & Aronsson, Citation2022; Karavatzis et al., Citation2017; Zenker & Erfgren, Citation2014). However, to what extent this community participation and inclusive approach is occurring or more taken for granted is an important element to unpack further through empirical research (Jernsand, Citation2016). Challenges remain around ensuring inclusive gender dimensions in place-branding strategies, and more research on this is needed at the city and regional levels because much of the research into gender and place branding is focusing on the national level (Jezierska & Towns, Citation2018; Rankin, Citation2012). Some previous cases (such as Boland & McKay’s case of Belfast, UK) have highlighted some of the issues around gender dimensions in place branding, as we discuss below.

A common understanding of place branding ‘lies [in] the assumption that, not too differently from goods and services, cities, countries and other spatially extended “products”, can be managed, developed and promoted following a marketing business philosophy’ (Lichrou et al., Citation2017, p. 2). It also resonates with a wider conceptualisation of trademarks leveraged at the regional level (Castaldi & Mendonça, Citation2022). However, when connecting the reputation of a celebrity to a particular city, the links need to be based on different grounds than sponsorship deals, public endorsements and commercials. In Kruse’s (Citation2004) study of the geography of The Beatles, he argues that the economic and cultural ties between the history of the band and their hometown Liverpool creates ‘Beatlespace’, providing opportunities for tourism and place branding beyond appreciation of their music.

‘Personality association’ place branding is low cost and easy to use, as it requires little or no investments in branding infrastructure (arenas, venues, bidding costs for large events, etc.) and is best applied, Ashworth (Citation2010) reasons, using cultural and/or historical figures. However, personality association is not a stand-alone approach and needs to be embedded within a wider set of strategies. Successful examples from Barcelona and Stratford, Ontario, illustrate that it is not merely the association with architect Antoni Gaudi (Buchrieser, Citation2019) and playwright William Shakespeare (Ashworth, Citation2010), respectively, that laid the foundation of successful place-branding campaigns. Rather, these tools were adopted in wider strategies of economic redevelopment and transformation, supported by large-scale events such as the Summer Olympic Games and an annual literature festival. Ashworth (Citation2010), encourages all policy professionals attempting to apply personality association to ask themselves, ‘Can this association be supported by other policy instruments, such as for example signature buildings, hallmark events, urban design or planning actions?’ (p. 233). If the answer is ‘no’, then the strategy is unlikely to succeed.

Also, the choice of celebrity might not be representative for the whole group of people that the brand should speak for, and speak to (Belabas & Eshuis, Citation2019). For example, discussing Belfast’s branding around footballer George Best, Boland and McKay (Citation2021) explain how Best’s well-known problems with alcoholism, drunk driving and domestic abuse have attracted criticism. Another challenge lies in matching the intended message of the brand with both the internal and external audiences being targeted (Ashworth, Citation2009; Giovanardi, Citation2011; Pike, Citation2011). The geographical reach of the celebrity’s reputability is crucial: a global icon will receive recognition with a wider group of people compared with a local hero whose actions are not known to an international audience (Boland & McKay, Citation2021; Buchrieser, Citation2019; Giovanardi, Citation2011). Moreover, all personalities are complex entities combining both commendable and less attractive traits. Clearly, in this approach a degree of selectiveness is needed, and place-branders must ask the question: What values of a personality are actively embedded with the brand, and what values are steered clear from?

So, personality association place branding is far from easy to achieve (Ashworth, Citation2009; Boland & McKay, Citation2021). A clear link between the person and the place, and ability to fight off competing claims to the person is required. A high degree of familiarity with the attributes that the person linked to the branding is also needed. The case of Rotterdam in the Netherlands as the city of Erasmus provides a good example of when it can go wrong (Belabas & Eshuis, Citation2019). Rotterdam’s efforts to leverage the brand of Erasmus were largely unsuccessful and can be understood through a series of factors. First, as an industrial city lacking in an attractive and culturally modern city image, Rotterdam was struggling with its brand and identity in comparison with the other large Dutch cities. Second, the chosen personality brand, Erasmus, in fact lived in several European cities for quite some time, so the link to Rotterdam as his place of birth was not an obvious one. Third, Erasmus was not well known or connected to Rotterdam within the city by either its residents or outsiders. Fourth, the difficulty of commodifying something such as philosophy (versus the tangible architecture or music examples above) all combined to make this a very difficult place-branding mission (Ashworth, Citation2009, Citation2010).

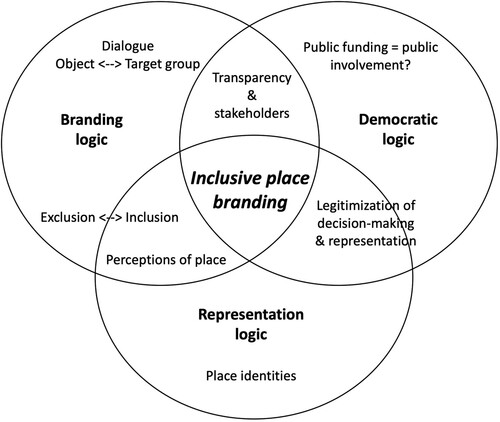

Building on this current state of the art in place branding and personality association research, before moving onto our empirical case we provide a conceptual framework for understanding inclusive place branding. combines three separate logics of inclusion. The first logic stems from the inevitable geographical differentiation of branding, where branding can be understood a simultaneous process of inclusion and exclusion of different stakeholders, unequivocally intertwined with the socio-spatial differentiation of people (Pike, Citation2009). This logic relates to the fact that branding (often described as ‘a dialogue’ between the branded object and the targeted group), requires the ability to both detect the brand and to understand what it stands for and attach value to it (Andersson, Citation2014a, Citation2015; Pike, Citation2009). Put simply, if you cannot see the brand nor do you understand its message, branding becomes obsolete.

Figure 1. The three logics of inclusive place branding.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

The second logic relates to discussions of democratic legitimation of decision-making in relation to place-branding strategies (Jernsand, Citation2016; Franzen, Citation2010). Often criticised for being pushed by economic growth narratives and/or urban elites, place branding is largely financed through tax revenues and public income, and spending public funds on campaigns, slogans and events can be quite a contested issue between different stakeholder groups (Andersson, Citation2014a: Citation2014b; Ashworth et al., Citation2015; McCann, Citation2013). If place-branding decision-making is not done in a transparent and democratic fashion involving different stakeholders that the brand aims to speak for, or whose tax payments are used for investments, place brands run the risk of being ‘short-circuited’ (Franzen, Citation2010).

The third logic of inclusive place branding connects to branding representation, and whose place identities or perceptions of a place that are being represented (Boland, Citation2010; Gotham, Citation2007; Jernsand, Citation2016). This logic often relates to stereotypes and preconceptions, and in what ways different stakeholders are being represented through branding narratives. Representation is often discussed in place-branding research when it is lacking, that is, when a plurality of stakeholder representations is missing or when people and places are being misrepresented through place branding (Belabas & Eshuis, Citation2019; Boland & McKay, Citation2021). As illustrated in , these three logics are somewhat overlapping and intertwined, but represent three different points of departure that give different perspective on inclusivity in place branding (Andersson, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Stålnacke & Andersson, Citation2014).

3. METHODS AND CASE STUDY

We draw on two main methods in this paper: (1) analysis of public documents and strategies by the local and regional authorities, and internal documents, reports, evaluations and memos provided by our participants; and (2) twelve in-depth semi-structured interviews with individuals involved in the branding and regional development strategising representing public authorities, business and university. In designing our approach to data collection and analysis, we consulted guidance on case study research (Yin, Citation2009). Official regional and local documents are accessible in Sweden online, and our participants also provided us with extra materials such as reports, slide shows, information and marketing materials, pamphlets, and even books about local history. These were all in Swedish, and we have translated these materials to convey their meaning but are providing a precis rather than raw excerpts for this reason. We used these materials either as general background information to help us build up the rich picture of the case study, or derived information about specific activities and facts (especially historical ones) from them. We searched for mentions of our keywords inspired by the research question we set out at the outset: regional development, place branding and Alfred Nobel.

For the interviews, participants were recruited via a snowballing strategy, using three main gatekeepers to find more relevant actors to speak to. The interviewees were equally split between the municipality, industry and university to capture different organisations involved in the ANK project. All our interviewees had senior and managerial roles because we wanted to speak to those directly involved in the place-branding and regional development activities in the city and region. We used an interview proforma to collect comparable data from across the different participants, but approached the interviews in a semi-structured and flexible manner to account for each participant’s different perspectives and experiences of the topic. Interviews ranged from 45 to 90 minutes. The interviews were recorded and fully transcribed, with participants’ permission. Our ethical process was in line with the guidelines at our institution at the time, and can be summarised thus: we prepared an information sheet summarising the intention of our research, who would be involved in processing the data, and how it would be stored securely according to our university’s rules. We explained that all participation was voluntary, could be withdrawn at any time, and that participants could review transcripts and amend or withdraw data as they saw fit. We provided contacts at the university in case of any questions or concerns. These information sheets were provided in advance of interviews, and at the start of each interview participants we asked to verbally agree that they had read and understood the information and were consenting to their participation as an interviewee.

Transcripts were analysed in an inductive manner, working directly from the data to identify themes and commonalities, as well as contrasts in the participant’s responses. We grouped together the data into trees and branches relating to different topics and themes and discussed these between the two researchers involved. We then went backwards and forwards between our empirical data and the literature to refine our understanding of what we were seeing in Karlskoga, and to pinpoint the pertinent elements of our case that could help us puh forward thinking and theorising around personality-based place branding and regional development. The interviews were conducted in a mixture of Swedish and English. In presenting the qualitative data we took on board the message provided by Yin, referring to case study research: consideration needs to be taken that participants’ opinions are not misrepresented and that their voice is preserved; the logic of the analysis should be clear to the reader, and they should be able to hear the different voices of the interviewees and the researcher (Yin, Citation2009, p. 78).

Due to the nature of our conversations, we had agreed anonymity and because of the small pool of individuals we were speaking to (and the fact that the city itself is quite small) we have needed to decouple the quotes from the respondents so as not to unblind our respondents and cannot provide information about specific respondents’ positions here. By triangulating these methods, as per the rationale that the ‘combination of multiple methodological practices, empirical materials, perspectives … adds rigor, breadth, complexity, richness, and depth to any inquiry’ (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2011, p. 5), we were able to collect and analyse a large quantity of qualitative data regarding the ANK case, and how it fits into the wider regional development strategy.

3.1. Introducing Karlskoga

Karlskoga is a small town in central Sweden, placed halfway between Oslo and Stockholm. There are two notable (and interconnected) facts about Karlskoga: it was the home of Alfred Nobel for a short period towards the end of his life, and it is the home of Bofors, one of the world’s best-known arms manufacturers, which still operates in the town today. Bofors is known for its Second World War Bofors gun, and the so-called ‘Bofors scandals’: the illegal smuggling of weapons to Dubai in 1984 and kick-back schemes in 1988, involving the US$1.4 billion (at the time) sale of guns to India. Bofors is also the reason why Nobel relocated to rural Karlskoga when acquiring the company: it has since the mid-1600s been a steel and weapons producer, benefitting from the many mines and mills in the region. With the purchase of the factory and the testing grounds came the mansion Björkborn, which became Nobel’s last official residence. So Karlskoga played an important role when the enormous fortune he left behind should accrue. As such, the local geography has very much developed in tandem with Bofors, providing a home for the development and testing of explosives and chemicals, while also having a major part in the foundation of the Nobel Prize in Sweden.

However, with a population drop with over 31% over the last 50 years (SCB, Citation2021) and the close relationship between the town and the company, the local authorities felt a need to decouple the negative associations with the Bofors scandals and the continued production of weapons. Therefore, beginning around 2016, the leading public and businesses representatives in Karlskoga decided to rebrand the town as ‘Alfred Nobel’s Karlskoga’ (ANK) and instigated a joint place-branding and infrastructure development strategy with the aim of attracting more residents, businesses and tourists to Karlskoga by focusing on the entrepreneurship and industrial spirit of Nobel himself. As one of our respondents describes it:

We are actually representing the knowledge, the technology, the high spirits, the entrepreneurship [of Nobel]. The only thing we must be hands off is the Nobel Prize. We want to take care of Alfred Nobel, the person, entrepreneur, global businessman. (Lars)

4. ALFRED NOBEL’S KARLSKOGA – CONTESTED AND CONTENTIOUS?

Having outlined the brief history of Karlskoga and the overall motives of ANK, we now move on to analyse and discuss some of the challenges and complexities we uncovered through our research in Karlskoga.

4.1. Sharing a famous figure

One major complexity in this case is the issue of who and where gets ownership of a famous figure, particularly one who is elevated to the national or international level. Thus, Karlskoga shares similarities with the Erasmus–Rotterdam case (Belabas & Eshuis, Citation2019). Concerning Nobel, the starkest contest is between the capital Stockholm – where the Nobel Prize ceremony takes place and the Nobel Prize Museum is a popular tourist visitor attraction – and Karlskoga. Indeed, the Nobel Foundation requested that Karlskoga rename their museum Alfred Nobel’s Björkborn to avoid confusion with the Nobel Museum in Stockholm which deals with the history of the prizes. Adding to the competition, and following the historical union between Sweden and Norway, Oslo is the home of the Nobel Peace Prize and hosts the Nobel Peace Museum. Consequently, the need to share the figure of Nobel with other places speaks against the coherent branding logic of inclusive place branding. To try to deal with this confusion, the ANK strategy focuses on the entrepreneur and inventor elements of Nobel’s legacy, while using his full name to distinguish from Nobel Prize attractions and activities, making it difficult for an outsider to understand the branding:

It’s very important that you use the full name, if we disconnect Alfred and Nobel we’ve got problems. It must be Alfred Nobel otherwise it’s not understandable. And if you talk about Nobel only then we are on our way into the Nobel Prizes because that’s what people connect to. (Lars)

There are both ANSP in Karlskoga and in Örebro. … There were some interesting things going on because of course they [in Örebro] want to use the Alfred Nobel name, and that was reserved for Karlskoga. So, it wasn’t fun because the people in Örebro made some. … I don’t know all the tricks they made … they managed to hijack the name [Alfred Nobel] to Örebro! They are trying to sell it as ANSP in Örebro [laughs]. (David)

In Örebro they want to get rid of it [the testing grounds]. No one in Karlskoga would dare say something like that because [they know] that it is their livelihood. … In Örebro they say ‘I don’t want anything bad in Karlskoga’, and these are quite large wooded areas where they could stroll and ride their bikes and do whatever they want to do, [but] they can’t use them. So of course, if you live in Örebro you want to get rid of it and have more woods. [In] Karlskoga they understand [that both] from a regional perspective but also from a national perspective, this is a very crucial area to use. … So yeah they [Örebro people] have got to pick their berries somewhere else. That’s just the way it is. (Benny)

4.2. Branding dynamite without mentioning it

Nobel’s most famous invention was dynamite, and though he may have hoped that the result would be an end to war and increasing world peace, indeed quite the opposite is true. Given that ANK rests on his innovation and entrepreneurship, it can be said without exaggeration that Karlskoga is a place built on explosives. Like Rotterdam with its industrial port (Belabas & Eshuis, Citation2019), it is difficult to improve a ‘dirty’ city image through branding alone. Indeed, the physical fabric of Karlskoga still bears the scars of this long tradition of industrial activity and has proven difficult to transform. It poses very real challenges for the city planners who are trying to develop and modernise the town, making it an attractive place for residents to live. A city planner sums up some of the challenges as follows:

There’s a lake and a beach and everything. But a great deal of the lake shore is where the companies are … it’s because you got your power there back in history [from the water wheels]. … Especially since there has historically been a defence industry and what they do there is secret so, up until the ’60s, ’70s, the municipality wasn’t even allowed to plan for them [i.e., the areas where the industries where located]. And then step by step it opened up more. But now we are going back again from being more open, they are closing them again. They are gonna put up guards in the entrances now. … We have a plan to make a bicycle path along the lake shore and a bridge over the river. And everyone has been for that, even the companies, but just a couple of years ago that started to change and they don’t want it … [sighs] it’s really tough. … If you wanna spy on these companies, I don’t think you are going to take a bicycle! You get the drones and everything … . (Benny)

People are proud to work for this company in Karlskoga. So, we have a long history, and we try to in different ways connect our history with Alfred Nobel. We have good working conditions and a long history of people who worked in Bofors and their sons and daughters also would like to work in [the] Bofors company. (Tim)

Bruksanda: you have a proudness of this area, being part of this. Almost in some ways it is not a good force because it holds you in the past. Bruksandan-mill society spirit. … Culture, and then you say you need to struggle, you don’t give up. … You need to tell the people why and where you are going and so on, and then they use the force, the union, so we do it in cooperation. And that Bruksanda and pride is very important – don’t give it up, never give up. And we understand we are not Stockholm; this is not Stockholm and you cannot compare us to Stockholm. Of course, it is easy in this Bruksanda to point to the enemy, it could be Stockholm and Örebro. … You need to understand that force because it can be bad and it can be good. (Maria)

The company had done awful things actually. And I guess the bribing affair with India was not very good … many people hated [the whistleblower]. So it is, so it was. The community, or most of the people, defended Bofors in a way. They said, ‘you sell some missiles to Dubai, what does it matter? A little place like Dubai does it matter?’ But it matters. I mean it is forbidden, against the law. That matters. And if you are bribing someone in India that matters, you shouldn’t do it. … I think it affected Bofors[’] reputation higher up and on other affairs. (Harry)

You can’t talk about Karlskoga without mentioning the scandals, the affairs going on … .

I don’t think it really changed anything, it was just the things that surfaced, and they’ve probably happened many times before, ha-ha. I think from a Karlskoga perspective it probably made people more together and they wanted to defend, defend themselves from being accused from the outside.

That’s my guess as well.

And then if it’s morally OK or not, that’s another question.

That’s never been a problem in the minds of Karlskoga.

No, I mean as long as you get your living out of the company, then it’s OK.

If you’re from Karlskoga, if you’re working in these companies, you always have to be prepared to explain WHY you work there. And [that] you’ve taken a stand when you signed [your employment contract]. … So, the bribes and all … [clicking noise with tongue]. … It was more the media who wrote about it, you understand, the paper wrote about it but for the people in the city. ‘Ok you are free to tell … ’: in Sweden you have this freedom of speech, and to think whatever you wish. But it has been unfortunate … when you work with war material it is complicated. (Maria)

4.3. Inclusive place branding and taking pride in contested heritage: democracy and representation?

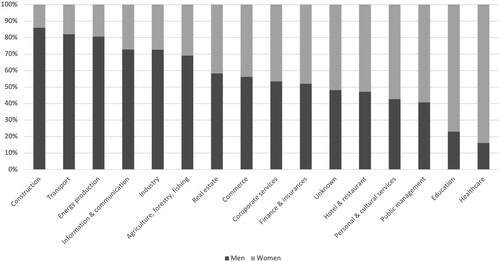

We cannot escape the question of how inclusive and representative of modern Sweden the ambition of the ANK brand really is. On all measures of health, economy, well-being, etc. there are clearly deep inequalities in Swedish society. Neither is life for people of colour, disabled, LGBTI in Sweden straightforward, and there are large variances in tolerance and life scenarios if we look across urban and rural areas. The picture is very complex (cf. Andersson & Molina, Citation2018; Forsberg & Stenbacka, Citation2018; Molina & De los Reyes, Citation2002). Relating to our case, current estimates given were that 3000 more workers are needed to match the demand for engineers and technicians in Karlskoga (Pugh & Lundmark, Citation2020), and the town is hoping to increase by 5000 people by 2025 (Karlskoga, Citation2020). At the same time, Karlskoga has the highest share of unemployment among foreign born in the region (28.9%), and the overall unemployment rate is 4.2% higher than the national average (13.0% in Karlskoga compared with 8.8% in Sweden), indicating matching difficulties between the positions offered and the competences of the unemployed local labour force (SVT, Citation2022). The industry in Karlskoga is still very gender biased towards men, and figures show a low proportion of women working in the highly paid technical jobs in the city (Pugh & Lundmark, Citation2020).

Against this backdrop, the question arises: Is ANK an appropriate image for the future of Karlskoga, and one that will make people feel welcome? This critical perspective was not present much in our interviews, neither from those within the municipality devising the strategy, nor from those other stakeholders commenting on it. Karlskoga has previously been criticised for lacking awareness of women’s role in the development of the town and in portraying its industrial history, for instance by celebrating ‘men of steel’ in the town square (Forsberg, Citation2003). Thus, the question of inclusiveness and co-creation of the new place brand emerges. Part of the story is our sampling problems conducting this research, whereby those occupying key positions in the university, municipality, industry associations and companies that we contacted are almost exclusively middle-aged white males. We suggest our lack of data in this area represents most respondents being ‘blind’ to these issues given their white majority male status, simply not seeing the potential inclusivity issues at play. However, following Forsberg’s (Citation2003) critique and illustrative example 20 years ago, the gendered structure of the Karlskoga labour market is still rather entrenched (). In the sectors embraced in the ANK campaign, such as industry and construction, the male dominance is significant (only 14.0% women employed in construction and 27.3% in industry), while the female dominated sectors such as education (77.0% women) and healthcare (83.9% women), generally receive much lower renumeration being dominated by assistant roles (the share of qualified doctors and teachers within these categories is quite low).

Figure 2. Labour market in Karlskoga, 2021: share of men and women in different sectors.

Source: SCB (Citation2023).

During our interviews, the only instance of inclusivity being discussed at length, in the case of gender dynamics, was with the only female respondent (although other respondents made some passing comment or small references to the gender imbalance in Karlskoga industry to date). In this discussion, we touched on the male dominated history of the city’s industry, and that Bofors had very few female managers. However, this was not felt to be problematic due to the inclusive and helpful culture of the Karlskoga industrial community:

But to be the manager might be a bit more controversial … in a male dominated environment but the men were very helpful. I can say this: men help each other. But I got a lot of support and help from men when I became manager. So that’s the culture – you help each other. (Maria)

On the issue of inclusivity according to race, nationality, etc. very little was said. Those discussions that did touch on this topic were around the problems in recruiting enough engineers into the city to work in the industry which is currently blooming due to the increased demand in a less peaceful world: ‘Karlskoga is still very deep into the defence industry. Now we have a world that is not peaceful anymore and what do you know, Karlskoga does better’ (Benny).

There are concerns, as with other technical industries in Sweden, that not enough technically qualified people are being trained by universities in Sweden (Persson & Hermelin, Citation2018), nor is the international migration situation open enough to allow the recruitment of qualified people from overseas. A further compounding problem for Karlskoga is that because of the nature of the defence industry, it is very hard for security reasons to employ people who are not Swedish citizens. There is also high competition for skilled workers with other Swedish towns that are making big investments, such as Skellefteå with the electric battery factory, and the mining industry in Kiruna (Lundmark et al., Citation2022). In which case, the key question around place branding becomes whether the image portrayed through ANK is that of an open and progressive city that is attractive for people to move to. This is a question we cannot answer without some sort of sophisticated market research much beyond what we have undertaken in our case study, but we find it an important issue to raise and one that does not seem to have been well considered by those instigating and involved in the branding of ANK.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This paper set out to investigate how place branding can be leveraged as part of an inclusive regional development strategy, using contemporary theorising around personality-based and inclusive place branding (Ashworth, Citation2009, Citation2010; Björner & Aronsson, Citation2022; Buchrieser, Citation2019; Karavatzis et al., Citation2017). This case, and the complexities therein, remind us that place branding is no easy task; indeed, it is ‘fraught with difficulty’ (Medway & Warnaby, Citation2014, p. 163). In particular, we agree with researchers who have previously found personality-based approaches to be difficult to implement for a variety of reasons (Ashworth, Citation2009; Boland & McKay, Citation2021). In this paper we critically examined a personality-based place branding effort – ANK – from the perspective of inclusive place branding using a bespoke theoretical framework we developed from the literature ().

Our case shows that several interesting dynamics and tensions arise when attempting to implement a personality-based place-branding strategy for the purpose of regional development. A challenge for those trying to implement the ANK strategy is that it is often poorly linked to wider regional development strategies (Ashworth, Citation2010; Buchrieser, Citation2019), involving a complex set of stakeholders from within and beyond the public sector. As an example, when the city planners wanted to develop the beach area of central Karlskoga with a new bike path, aligning with the overall goal to provide attractive nature areas and active travel possibilities for residents, the local power dynamics (and might of the defence industry in the city) put a stop to it – for security reasons. These types of tensions and challenges are specific to the Karlskoga case, but nevertheless speak to broader concerns within regional development, such as how to design a strategy for regional development and planning that is truly inclusive of all a regions’ residents, and how to forge a path forward for industrial regions steeped in an unfavourable or problematic industry when considered with contemporary views of sustainability on environmental, social and economic grounds.

Following discussions in participatory and inclusive place branding (Björner & Aronsson, Citation2022; Jernsand, Citation2016; Karavatzis et al., Citation2017), it is clear there is an apparent lack of inclusiveness in the ANK place-branding efforts. Whilst the logic and character of the ANK brand is clear (Nobel is an extremely well-known figure and his invention of dynamite conducted in Karlskoga is one of Sweden’s most famous innovation histories), this strategy underperforms the other elements of inclusive place branding that we identify: the representation and democratic logics. We saw little effort in our research on behalf of the strategies proponents to ensure a representative and democratic process behind choosing and rolling out the brand. Indeed, there is little consideration that anyone except ‘the guys’ should be involved in the development of ANK, and when the regional council wanted to expand the geographical scope of the Nobel branding to include the whole region, this was met with resistance in Karlskoga. In addition, in its current format ANK is still very much a central organisation broadcasting a message ‘to the masses’. In doing so, the warning issued by Medway and Warnaby (Citation2014, p. 153) seems pertinent to this case:

the commodifying effects of places as brand names, with their associated brand values and imagery, can potentially suppress the alternative place perceptions of users, and in doing so stifle the natural potential for cocreation of the place ‘product’ and its related value.

The message broadcast via ANK is not always very sensitive to the local place nor the local identity. True, a certain amount of ‘cherry-picking’ in personality-based branding is inevitable (Ashworth, Citation2010; Buchrieser, Citation2019), and in this case especially to avoid any trademark infringements with the Nobel Prize and museum in Stockholm. Thus, the city planners meet an issue that is already reported in the literature on place branding around contestations, both internal and external to the place in question (Medway & Warnaby, Citation2014). The ANK place brand skirts the issue that sits at the heart of Karlskoga: the invention of dynamite and the historic development of the defence industry which still dominates the city today. In doing so, they are actively disregarding the local identity, pride and Bruksanda connected to the company Bofors, rather than to Alfred Nobel himself. Therefore, unlike the case of Rotterdam where the Erasmus brand was not very well recognised among the local population (Ashworth, Citation2010; Belabas & Eshuis, Citation2019), the branding of ANK risks not resonating with Karlskoga residents – not because the connection is not there, but that the real connection embedded in the Bruksanda is actively being hidden and downplayed in the place brand.

Another issue related to the lack of inclusiveness in the ambitions of ANK is gender awareness. This also happens to be scantily covered in the place-branding literature to date, especially at the local level (Jezierska & Towns, Citation2018; Rankin, Citation2012). Nevertheless, in the case of ANK, it is clear that the gendered structure of the local labour market has not been a concern when designing the place brand, despite the fact that the male domination of the main sectors is acknowledged as a problem. And following Forsberg’s (Citation2003) historical account of Karlskoga, gender awareness has never been present when local stakeholders define what best represents their town. However, this is not unique to Karlskoga, but likely true for many industrial towns. Nonetheless, it is an important lesson to be learned if we are to fully understand how gender norms influence regional development outcomes in general (Forsberg & Stenbacka, Citation2018) and in place branding specifically. There is also more to unpack and investigate regarding the inclusion and awareness of foreign born and immigrants (especially those who migrated to Sweden precisely to avoid war and conflict) in the population where place branding is concerned, but this has not been within the scope of this paper.

Furthermore, we remain somewhat confused as to who the audience for ANK is, especially in the light of inclusive and participatory place branding. Potential residents, existing residents, new business and tourists are all mentioned, but the approach does not seem particularly tailored to any of them and is quite scattered. There seems to be little inclusion of these groups in the process; they can hardly be considered co-creators of the brand. We are not even sure if what Karlskoga is doing can qualify as a place-branding strategy because it is so disconnected and varied, it seems more a case of capturing whatever opportunities are available to link up aspects of the city’s development and branding to Nobel wherever possible.

In terms of tangible policy recommendations that arise from this case, we could suggest that branding a particular element or infrastructure under the Alfred Nobel moniker may be more suitable than the entire town. We felt that the branding of ANSP was a good example of this because it could be relevant to connect Nobel’s inventions and innovations with the innovation infrastructure. However, since we undertook this study and wrote this paper, the city has decided to close ANSP and remove its funding from it because it was felt not to align with the city’s wider strategy and priorities. We are both surprised and puzzled by this move, given that the strategy of branding a science park using Alfred Nobel seems a logical move, and during our case study collection seemed to be an important element of the city’s economic development and innovation approach. The loss of the Alfred Nobel name in the science and innovation infrastructure from Karlskoga to Örebro is a sign that the town has failed to really capitalise on the brand, and that it has indeed been captured by other places and interests from the ‘outside’.

Finally, we situate our contribution against a trend recognised by Cassinger et al. (Citation2021) within Nordic place-branding scholarship towards critical and provocative perspectives. Given the ‘explosive’ nature of the issues we are dealing with in the case of Karlskoga, especially considering the scandals that made Bofors, and the town itself, famous for all of the wrong reasons, this critical perspective is indeed necessary – from an inclusivity perspective, in asking who place branding is by and for – but also from the perspective of transitioning to a more sustainable mode of regional economic development. Where exactly does the heavily industrialised production and testing of defence materials and technologies, and the strongly gendered nature of the industry and the city’s power structures we uncovered, fit within the ideal picture of a socially equitable, high trust society and environmentally responsible mode of being commonly associated with the Nordics (Cassinger et al., Citation2021) is an unanswered question. Overall, we are forced to end on a question, which has been opened up by this study: Is it possible to do inclusive personality-based place branding, or is it by definition exclusive to chose one person or figure to brand a whole city (and all the people therein) around?

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Andersson, F., Ek, R., & Molina, I. (2008). Regionalpolitikens geografi. Studentlitteratur.

- Andersson, I. (2014a). Beyond ‘Guggenheiming’: From flagship buildings to flagship space in Sweden. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 68(4), 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2014.927915

- Andersson, I. (2014b). Placing place branding: An analysis of an emerging research field in human geography. Geografisk Tidsskrift – Danish Journal of Geography, 114(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167223.2014.895954

- Andersson, I. (2015). Geographies of place branding: Researching through small and medium-sized cities [Doctoral dissertation]. Digitala Vetenskapliga Arkivet, Stockholm Universitet, p. 156.

- Andersson, I., & James, L. (2018). Altruism or entrepreneurialism?: The co-evolution of green place branding and policy tourism in Växjö, Sweden. Urban Studies, 55(15), 3437–3453. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017749471

- Andersson, R., & Molina, I. (2018). Racialization and migration in urban segregation processes Key issues for critical geographers. In Öhman, J. & Simonsen, K. (Eds.)., Voices from the North (pp. 261–282). Routledge.

- Ashworth, G. (2009). The instruments of place branding: How is it done? European Spatial Research and Policy, 16(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10105-009-0001-9

- Ashworth, G. (2010). Personality association as an instrument of place branding: Possibilities and pitfalls. In G. Ashworth, & M. Kavaratzis (Eds.), Towards effective place brand management (pp. 222–233). Edward Elgar.

- Ashworth, G. J., Kavaratzis, M. & Warnaby, G. (2015) The need to rethink place branding. In M. Kavaratzis, G. Warnaby & G. J. Ashworth (Eds.), Rethinking place branding. Comprehensive brand development for cities and regions. Springer.

- Beer, A., Barnes, T., & Horne, S. (2023). Place-based industrial strategy and economic trajectory: Advancing agency-based approaches. Regional Studies, 57(6), 984–997.

- Belabas, W., & Eshuis, J. (2019). Superdiversity and city branding: Rotterdam in perspective. In P. Scholten, M. Crul, & P. van de Laar (Eds.), Coming to terms with superdiversity. IMISCOE research series (pp. 209–223). Springer.

- Björner, E., & Aronsson, L. (2022). Decentralised place branding through multiple authors and narratives: The collective branding of a small town in Sweden. Journal of Marketing Management, 38(13–14), 1587–1612.

- Boland, P. (2010). Sonic geography, place and race in the formation of local identity: Liverpool and Scousers. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 92(1), 1–22.

- Boland, P., & McKay, S. (2021). Personality association and celebrity museumification of George Best (with nods to John Lennon). Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 17(4), 409–419. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-020-00170-7

- Buchrieser, Y. (2019). Simulacra architecture in relation to tourism: Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Glasgow and Antoni Gaudi in Barcelona. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 17(1), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2019.1560915

- Cassinger, C., Gyimóthy, S., & Lucarelli, A. (2021). 20 years of Nordic place branding research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1830434

- Castaldi, C., & Mendonça, S. (2022). Regions and trademarks: Research opportunities and policy insights from leveraging trademarks in regional innovation studies. Regional Studies, 56(2), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.2003767

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Sage.

- Forsberg, G. (2003). Genusforskning inom kulturgeografin – en rumslig utmaning. Högskoleverket.

- Forsberg, G., & Stenbacka, S. (2018). How to improve regional and local planning by applying a gender-sensitive analysis: Examples from Sweden. Regional Studies, 52(2), 274–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1296942

- Franzén, M. (2010) Varumärkets kortslutning?: 'Stockholm the Capital of Scandinavia'. Kultur & Klasse, 109, 119–132.

- Giovanardi, M. (2011). Producing and consuming the painter Raphael's birthplace. Journal of Place Management and Development, 4(1), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538331111117160

- Gotham, K. F. (2007). (Re)branding the big easy: Tourism rebuilding in post-Katrina New Orleans. Urban Affairs Review, 42(6), 823–850.

- Grundel, I. (2022). Regioner och regional utveckling i en föränderlig tid. SSAG.

- Hall, T., & Hubbard, P. (1996). The entrepreneurial city: new urban politics, new urban geographies? Progress in Human Geography, 20(2), 153–174.

- Harvey, D. (1989). From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: The transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, 71(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583

- Jernsand, E. M. (2016). Inclusive place branding: What it is and how to progress towards it [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Gothenburg, p. 96. https://gup.ub.gu.se/publication/247394

- Jezierska, K., & Towns, A. (2018). Taming feminism? The place of gender equality in the ‘progressive Sweden’ brand. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 14(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-017-0091-5

- Karavatzis, M., Giovanardi, M., & Lichrou, M. (Eds.). (2017). Inclusive place branding: Critical perspectives on theory and practice. Routledge.

- Karlskoga. (2020). Hur visionen och målet 32 000 hänger ihop. www.karlskoga.se.

- Kavaratzis, M., Warnaby, G., & Ashworth, G. (Eds.). (2015). Rethinking place branding: Comprehensive brand development for cities and regions (pp. 1–11). Springer.

- Kruse, R. (2004). The geography of the Beatles: Approaching concepts of human geography. Journal of Geography, 103(1), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340408978566

- Lichrou, M., Kavaratzis, M., & Giovanardi, M. (2017). Introduction. In M. Kavaratzis, M. Giovanardi, & M. Lichrou (Eds.), Inclusive place branding. Critical perspectives on theory and practice (pp. 23–32). Routledge.

- Lillback, S. (2017). Bruksare – mer än ett yrke? Om platsens betydelse i valet att identifiera sig som bruksare (pp. 1–34). Linnéuniversitetet.

- Lundmark, L., Carson, D., & Eimermann, M. (2022). Spillover, sponge or something else?: Dismantling expectations for rural development resulting from giga-investments in Northern Sweden. Fennia, 200(2), 157–174.

- Lundmark, M., & Hedfeldt, M. (2015). New firm formation in old industrial regions: A study of entrepreneurial in-migrants in Bergslagen, Sweden. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 69(2), 90–101.

- McCann, E. (2013). Policy boosterism, policy mobilities, and the extrospective city. Urban Geography, 34(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2013.778627

- Medway, D., & Warnaby, G. (2014). What’s in a name? Place branding and toponymic commodification. Environment and Planning A, 46(1), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1068/a45571

- Molina, I., & De los Reyes, P. (2002). Kalla mörkret natt!: kön, klass och rasetnicitet i det postkoloniala Sverige.

- Persson, B., & Hermelin, B. (2018). Mobilising for change in vocational education and training in Sweden – A case study of the ‘technical college’ scheme. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 70(3), 476–496.

- Pike, A. (2009). Brand and branding geographies. Geography Compass, 3(1), 190–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00177.x

- Pike, A. (2011). Placing brands and branding: A socio-spatial biography of Newcastle Brown Ale. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 36(2), 206–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00425.x

- Pugh, R., & Lundmark, M. (2020). Economic development and place attractiveness: The case of Karlskoga in Sweden. Siirtolaisuus-Migration, 46, 21–29. https://siirtolaisuus-migration.journal.fi/article/view/95555

- Rankin, P. L. (2012). Gender and nation branding in ‘The true north strong and free’. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 8(4), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2012.18

- SCB. (2021). Folkmängden i Sveriges kommuner 1950–2020 enligt indelning 1 januari 2021. Statistikdatabasen SCB.

- SCB. (2023). Registerbaserad arbetsmarknadsstatistik (RAMS) efter region, näringsgren SNI 2007 och kön (2019–2021). Statistikmyndigheten SCB.

- Stålnacke, F., & Andersson, I. (2014). Interna eller externa målgrupper?: En studie om platsmarknadsföring i Göteborg och Stockholm. Geografiska Notiser, 72(1), 7–18.

- SVT. (2021). Karlskoga kommun väljer att dra sig ur Science Park. SVT Örebro. www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/orebro/

- SVT. (2022). Karlskoga har högst arbetslöshet i länet bland utrikesfödda: ‘Det gäller att alla hjälper till’. SVT Örebro. www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/orebro/

- Ström, O. (2020). Örebro län kraftsamlar kring alfred nobel. Pressmeddelande TT. https://via.tt.se/pressmeddelande/orebro-lan-kraftsamlar-kring-alfred-nobel?publisherId=3235654&releaseId=3270756

- Sunley, P., Evenhuis, E., Harris, J., Harris, R., Martin, R., & Pike, A. (2021). Renewing industrial regions? Advanced manufacturing and industrial policy in Britain. Regional Studies, 1–15.

- Tomlinson, P. R., & Robert Branston, J. (2018). Firms, governance and development in industrial districts. Regional Studies, 52(10), 1410–1422. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1324199

- Yin, R. (2009). Case study research; design and methods (4th Ed.). Sage.

- Zenker, S., & Erfgren, C. (2014). Let them do the work: A participatory place branding approach. Journal of Place Management and Development, 7(3), 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-06-2013-0016