ABSTRACT

A soft spaces lens enables a nuanced perspective on regional resilience governance to disruptions. Focusing on COVID-19, this article illuminates comparative insights into resilience governance in England and how the regional soft spaces of local resilience forums differentially experienced this momentous disruptive event. The pandemic has exposed the limited ability of these regional soft spaces to enhance resilience to disruptions and thus narrow the resilience implementation gap. This article contributes to theory and practice on the tensions and opportunities to progress resilience governance through regional soft spaces amid an evolving policy landscape post-pandemic.

1. INTRODUCTION

Soft spaces have provided a valuable conceptual framework since the late 2000s to describe informal spaces of governance that coexist, and interact with, the formal territorial spaces of government (Haughton & Allmendinger, Citation2007; Hincks et al., Citation2017). Whether focused on devolution in the context of state rescaling (Stafford, Citation2023), or the economic reorientation of strategic planning for city-regions (Ferm et al., Citation2022), soft spaces are implicated within change processes involving new forms of governance and institutional arrangements. Resilience too is a concept enmeshed within explorations of regional transformation (Fastenrath & Coenen, Citation2021; Pitidis et al., Citation2023). Despite various interpretations and critiques (e.g., Welsh, Citation2014), resilience has eclipsed sustainability somewhat as a normative aspiration around which regional actors coalesce (MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2013). Actors at the regional scale are crucial to the coordination and delivery of ‘bottom-up’ resilience actions (Kythreotis & Bristow, Citation2017). Yet, resilience governance has not been investigated vis-à-vis regional soft spaces, so this article examines key dimensions of their interrelationship in theory and practice.

Our argument in this article is that a soft spaces lens enables a nuanced perspective on regional resilience governance. While resilience is promoted globally as being vital to the ability to adapt and thrive amid the current, anticipated and unexpected risks facing humanity (e.g., United Nations, Citation2020), disparities persist between the ambitions of resilience discourses and the practice of institutions (Coaffee et al., Citation2018; Pitidis et al., Citation2023). The effects of risks are locally felt so resilience needs to be built regionally through policy frameworks shaping action on many challenges, including climate change and chronic inequality. To date, few studies have examined alternative modes of resilience governance, which is pivotal to narrowing the ‘resilience implementation gap’ (Coaffee et al., Citation2018; Fastiggi et al., Citation2021; Wagenaar & Wilkinson, Citation2015). Soft spaces offer a valuable conceptual and empirical framing for addressing this lacuna, both in illuminating tensions and pathways on how to progress resilience implementation. For example, the construction of spatial imaginaries to aid the development of ‘adaptive governance mechanisms in conjunction with wide cross-sectoral collaborations’, is an emergent but underexplored perspective on resilience (Pitidis et al., Citation2023, p. 707). Thinking on soft spaces is well-placed to advance this line of enquiry that can inform scholarly and policy–practice agendas on resilience (e.g., Haughton & Allmendinger, Citation2015; Hincks et al., Citation2017; Stafford, Citation2023).

Consistent with Purkarthofer and Granqvist (Citation2021, p. 322), we do not suggest a single ‘correct’ definition of soft spaces, aware that the concept has evolved via its translation into contexts beyond its originating focus on planning and economic development. The borders of regional spaces cannot be denoted straightforwardly, whether as ‘porous, soft, fuzzy, semi-permeable or hard’ (Harrison et al., Citation2017, p. 1031). That is, they exhibit hybrid qualities as complex, multilayered spaces which are ‘part-soft, part-hard’ in their forms and practices – hard denoting territorial spaces that are bounded and operate more formally (Allmendinger et al., Citation2015, p. 6; Paasi & Zimmerbauer, Citation2016; Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2020). What hybridity means in the context of regional soft spaces of resilience governance, and the challenges and possibilities presented for enhancing resilience, are central to our discussion.

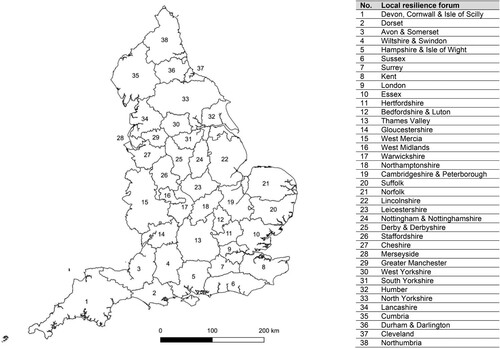

We focus on resilience governance in the aftermath of disruptions – specifically, on soft spaces through the lens of local resilience forums (LRFs) in England, which are the regional multi-agency entities responsible for building resilience to disruptive events such as severe weather (Shaw & Maythorne, Citation2013). They represent regional soft spaces of resilience governance () aiming to develop capabilities to achieve coordination across local authorities, public-service responders, voluntary and community sector organisations. In common with other soft spaces, LRFs are ‘governance bodies’ which are ‘not subject to the formal system of democratic elections’, but rather coexist ‘alongside but separate to the spaces and scales of elected government bodies’ such as local authorities (Allmendinger et al., Citation2015, p. 4). LRFs are key to the prospects for effective subnational governance of resilience (Richmond & Hill, Citation2023; Shaw & Maythorne, Citation2013), and government policy recommends their strengthening over the next decade (Cabinet Office, Citation2022). They are ideally placed to help understand the intersecting impacts of acute and chronic stresses at the regional scale, including how climate-related disruptions such as extreme heat manifest in local communities (Richmond & Hill, Citation2023). By integrating and coordinating multilevel, multisector partners with both short- and long-term perspectives on resilience, LRFs can also perform a boundary management function salient to enhancing resilience to disruptions (Cash et al., Citation2006; Fastenrath & Coenen, Citation2021).

Figure 1. Local resilience forum (LRF) boundaries in England.

Informed by interviews with LRF representatives, combined with ethnographic observations of LRF activities, our study explores COVID-19 pandemic recovery challenges. For the first time, all LRFs faced the same disruptive event simultaneously. This is significant as it permits us to draw comparative insights on resilience governance, the commonalities, and differences in how regional soft spaces perform amid a highly challenging disruption, in a way not previously possible. Resilience can only be truly tested in the context of disruption. The systemic weaknesses and inequalities exposed and exacerbated by the pandemic have informed alternative approaches to recovery (McClelland et al., Citation2023), while placing renewed emphasis on resilience implementation. Critically, this includes how resilience governance influences future regional resilience (Bailey et al., Citation2021). However, the contribution of LRFs to resilience has previously been questioned, with limiting factors including budgetary constraints (Chmutina et al., Citation2016); the dominance of national government in civil contingencies (O’Brien & Read, Citation2005); and a short-term focus on ‘bouncing-back’ rather than transformation (Shaw & Maythorne, Citation2013). We support these assertions and add novel insights focusing on the governance architecture of LRFs which impacts their ability to enhance resilience, as well as on how this disruption is shaping ambitions for resilience governance and practice. Recent publication of the UK Government Resilience Framework 2022 is indicative of an evolving policy landscape.

This article is structured as follows. We next review the theoretical and practical underpinnings of the resilience implementation gap and the relevance of regional soft spaces to resilience governance. We then outline the research setting and design, including introducing LRFs as regional soft spaces of resilience governance. Our findings then illuminate the qualitative insights emerging from semi-structured interviews. We conclude with a discussion on key tensions and opportunities pertaining to regional soft spaces in seeking to advance resilience governance. Questions pertinent to a future research agenda are outlined in the conclusions.

2. REVIEW AND CONCEPTUAL UNDERPINNINGS

2.1. Resilience in theory and practice

Policy actors mobilise resilience as a ‘solution’ to complex challenges such as regional recovery from pandemics (Bailey et al., Citation2021). A key strength resides in the relevance of resilience as a ‘strategic lynchpin’ connecting policy issues (Shaw & Maythorne, Citation2013, p. 57), with its ‘broad appeal’ to regional policymakers, businesses and communities better enabling buy-in from wider networks (Kythreotis & Bristow, Citation2017, p. 1536). Scholarly attention has shifted from definitional concerns to questions of implementation and its value as a ‘progressive practice’ (Vale, Citation2014). Critical perspectives still proliferate, especially over its contribution to the ‘responsibilization’ of risk ‘away from the state’ (Welsh, Citation2014, p. 15), and the degree to which resilience plans integrate social equity (Fitzgibbons & Mitchell, Citation2019). Yet research evidences the role of resilience in fostering transformative change (e.g., Fastenrath & Coenen, Citation2021; Pitidis et al., Citation2023).

An expanding literature draws upon an ‘evolutionary’ perspective of resilience (Davoudi et al., Citation2012; Simmie & Martin, Citation2010) – that views the resilience of socio-ecological systems such as regions as ‘continually altering, as the system adapts and changes’ (Davoudi et al., Citation2013, p. 310). Hence, when faced by disruptions, instead of bouncing back to ‘normality’ or equilibrium after recovery (i.e., status quo), evolutionary resilience emphasises change towards a more desirable state. This contrasts with the engineering or ecological-based understandings, both characterised by White and O’Hare (Citation2014) as ‘equilibrist’ in nature. The interpretation adopted matters given the differing outcomes when distinctive resilience conceptions frame policy actions.

Resilience practice draws upon both the equilibrist and evolutionary ‘meta-approaches’ (Coaffee, Citation2020). However, the emergency management perspective, which encompasses the work of LRFs in England, is considered short-term and response-oriented rather than focused on transformation to ‘improve upon the original status quo’ (Shaw & Maythorne, Citation2013, p. 52). In short, it tends to reproduce a form of resilience that ‘deals with the effects and not the causes’ of the conditions that generate vulnerabilities and differentially exposes regions to stresses and shocks (Chmutina et al., Citation2016, p. 75). With empirical examples of evolutionary resilience being rare (Coaffee et al., Citation2020), disparities are apparent between the theory, policy and practice of resilience to disruptions.

2.2. Resilience implementation gap

Accomplishing the normative ambitions of resilience is confronted by an implementation gap (Chelleri et al., Citation2015; Coaffee et al., Citation2018). Although this gap is multifaceted, matters of governance dominate. Its shortcomings challenge institutions to go beyond ‘business as usual’, for example, by developing anticipatory and adaptive capacities (O’Hare et al., Citation2015). The utility of resilience as a ‘bridging concept’ accommodative of wide-ranging dialogue (Davoudi et al., Citation2012), is reduced without the corresponding transitions in governance required to achieve agreed objectives. We focus on three resilience governance themes: collaboration; innovation and learning; and strategic coordination. These themes imbue the literature and explicate key facets of the implementation gap (Coaffee et al., Citation2018; Fastiggi et al., Citation2021), while resonant as enabling attributes of soft spaces (Othengrafen et al., Citation2015; Stafford, Citation2023).

First, multilevel collaboration that extends across sectoral and institutional boundaries is impeded when public bodies operate within ‘technical, bureaucratic and short-term ways of working in policy silos’ (Coaffee et al., Citation2018, p. 404). Developing broad-based collaborative relationships is critical to implementation, in part because negotiating what resilience entails in specific contexts, the ‘resilience of what to what’ and ‘for whom’ (Cutter, Citation2016; Lebel et al., Citation2006), is contingent on co-constructing inclusive processes (Harris et al., Citation2018). Contextualising resilience to local concerns cannot be achieved top-down or absent of meaningful collaboration (Fastiggi et al., Citation2021).

Second, innovation and learning are important to develop adaptive capacities that enable flexible forms of governance (Boyd & Juhola, Citation2015). Davoudi et al. (Citation2013) position social learning as central to evolutionary resilience, which they relate to the proactive enhancement of preparedness to disruptions. This encompasses fostering anticipation and foresight to divine potential vulnerabilities and opportunities; the importance of which is emphasised in relation to resilience implementation (e.g., Coaffee et al., Citation2018). Further, experimentation can influence resilience agendas, whether in helping to ‘break down bureaucratic silos’ (Fastenrath & Coenen, Citation2021), or leading to new governance practices (Fastiggi et al., Citation2021). Taking calculated risks and learning from failure are important yet underplayed facets (Fastenrath & Coenen, Citation2021).

Finally, strategic coordination at the regional scale is critical to resilience implementation (Wagenaar & Wilkinson, Citation2015). To illustrate in relation to the Resilient Melbourne Strategy, given the absence of a metropolitan governance structure bridging multiple local authority areas, a platform for cross-sectoral and cross-scale governance was instituted as a governance experiment to support strategy delivery (Fastenrath & Coenen, Citation2021). The Resilient Melbourne Delivery Office was integral to initiating and shaping coordination, not least as a ‘continuous platform for knowledge exchange’ (Fastenrath & Coenen, Citation2021, p. 145). Such ‘boundary organizations’ help to integrate stakeholders and identify common goals among the plurality of interests represented within regional networks (Cash et al., Citation2006, n.p.).

Strategic coordination is constrained by tensions in practice. Marshalling ‘sufficient convening power’ is not always possible, making it difficult to operate within and across regional, territorial, or sectoral boundaries and overcome ‘institutional gridlocks’ (Fastenrath & Coenen, Citation2021, p. 145). Divergence between theory and practice is apparent as to how resilience implementation is best organised. Scholars emphasise the importance of a coordinating entity (e.g., chief resilience officer) working across scales, whereas practitioners stress the potential for trade-offs between centralised and decentralised approaches (Fastiggi et al., Citation2021). A centralised approach can enhance the ability to coordinate, but decentralising responsibilities may better institutionalise resilience thinking across policies and practices.

Networks are a more complex terrain than single institutional settings. Territorial sovereignty and the coordination level achieved are highly pertinent to resilience implementation. Hanssen et al.’s (Citation2013) ‘ladder of coordination’, for example, suggests four types of coordination alignment among actors in multilevel collaborations – in their case concerning climate change adaptation. These extend from the lowest rung, which involves the ‘mutual exchange of information’, to the highest, which entails the co-management of ‘joint action’ (Hanssen et al., Citation2013, p. 873). When coordination fails within networks dealing with disruptions, accountability challenges may arise with disastrous outcomes. With few studies examining alternative modes of resilience governance (Wagenaar & Wilkinson, Citation2015), we adopt soft spaces as a novel perspective.

2.3. Soft spaces for resilience implementation

Whereas hard spaces encompass bounded institutions operating through statutory systems and formal practices (e.g., local authorities), soft spaces are more informal, open arenas within which ‘implementation through bargaining, flexibility, discretion and interpretation dominate’ (Haughton & Allmendinger, Citation2007, p. 306). As intimates, soft (and hard) refers both to the type of governance, and the type of space, the latter partly defined by the porosity of its borders. Among the political drivers behind their emergence was a desire for alternative ways to ‘get things done’; as an antidote to siloed and bureaucratic approaches (Othengrafen et al., Citation2015). Soft spaces are thus supportive of policy integration to address the ‘real geographies’ of problems and opportunities (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009; Haughton et al., Citation2010). In the words of Allmendinger et al. (Citation2015, p. 15), they ‘are part of the response to managing the need for and tensions … of relational space against a backdrop of … territorial spaces’. These, together with other perceived benefits of soft spaces, such as improved scope for innovation, speak directly to the resilience implementation gap.

Table 1. Characteristics of ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ regional spaces.

Conceptually, soft spaces bridge territorial and relational understandings of space (Allmendinger, Citation2016). That is, soft spaces are a hybrid between the ‘fixity’ of the former and the ‘fuzziness’ of the latter (Cavaco et al., Citation2023). Relational thinking emphasises the importance of networked relations in which regions, rather than bounded, static entities nested within territorial hierarchies, are understood ‘as fluid entities in the globalised and networked economy’ (Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2020, p. 771). This distinction between territorial and relational perspectives reflects the key characteristics of hard and soft spaces. However, theoretical advances have moved these concepts ‘beyond a simple ‘hard-soft’ dichotomy’ (Stafford, Citation2023, p. 3). Several dynamic and hybrid dimensions of soft spaces are important to understanding resilience governance to disruptions.

The first dimension concerns the ‘tethering’ of soft to hard spaces (Othengrafen et al., Citation2015). In short, soft spaces typically fall ‘back upon the legislative powers and democratic legitimacy of local political processes’ (Allmendinger, Citation2016, p. 163). Getting things done requires resources, and the powers and statutory processes of sovereign entities. Without seeking the legitimacy afforded by democratic processes, soft spaces have been accused of supporting forms of innovation that seek to ‘displace politics’ and avoid accountability (Haughton et al., Citation2013). This is especially so where neoliberal forms of economic growth are a driving objective (e.g., Ferm et al., Citation2022). As indicates, soft spaces’ depoliticised nature means that accountability may be selectively displaced through their constituent organisations. What such decentralisation means for strategic coordination over time is a potential source of tension within a soft space setting.

The ‘hardening’ of soft spaces is a second dimension. In Stafford’s (Citation2023, p. 8) study of Welsh transport policy, the emergence of statutory transport plans represented a ‘key stage’ in the hardening of regional transport consortia. These consortia evolved via a mix of bottom-up and top-down initiatives, moving from working on ‘largely informal lines’, to institutionalising their governance and shifting towards project delivery (Stafford, Citation2023, p. 7). Yet, as Metzger and Schmitt (Citation2012) questioned, the hardening of soft spaces may not increase their durability. It may even render them ‘more brittle, and less resilient to change’, which, in the case of the transport consortia, hastened their dissolution (Stafford, Citation2023, p. 13). Hardening further risks undermining the ‘perceived benefits of soft spaces’, including around flexibility and innovation (Stafford, Citation2023, p. 8).

Zimmerbauer and Paasi (Citation2020) usefully discuss regional soft spaces that become hybrid – in their case of planning. These spaces are formed by the concurrent hardening of soft spaces and ‘softening’ of hard spaces, thereby creating an overlapping ‘in-between’ space of governance denoted by multilayered borders. They propose that these processes, which are context and time-contingent, may lead to ‘hard spaces with soft elements and vice versa’ (Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2020, p. 786). That such spaces consist of an interplay between hard and soft reveals how regional soft spaces can enhance resilience. For example, Harrison et al. (Citation2017) talked about how a higher education consortium softened its initially hard border to broaden collaboration. Adapting relative softness (or hardness) to proactively address a key facet of resilience implementation is replicable elsewhere. However, how hard and soft fuse together is underexplored (Paasi & Zimmerbauer, Citation2016) – as are the tensions and synergies generated when soft spaces become hybrid (Purkarthofer & Granqvist, Citation2021). We examine these issues below.

3. RESEARCH SETTING AND DESIGN

Focusing on resilience governance amid disruptions allows exploration of various dynamics connecting soft spaces and the resilience implementation gap. Below we introduce LRFs as our empirical focal points, followed by the methods and data analysis employed. First, we establish the research context in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.1. COVID-19 as an atypical disruption

COVID-19 represented a global ‘shock’ with uneven impacts across and within regions and an anticipated ‘long shadow’ in terms of its health, socio-economic and political consequences which will unfold over many years (Bailey et al., Citation2021; British Academy, Citation2021). Its scale, scope and cascading effects encompassed every sector of society (McClelland et al., Citation2023), presenting challenges and opportunities in response and recovery that render it distinct from other disruptions such as those associated with geological (e.g., earthquakes) or environmental hazards (e.g., flooding) (Schoch-Spana, Citation2020). For example, as Dzigbede et al. (Citation2020, p. 635) remarked, COVID-19 ‘does not square easily within the framework of weather-related natural disasters’, causing no visible or physical damage, and with unclear temporal boundaries marked by waves of infection rather than more linear beginning and end points. This had governance implications, not least in the prominence of health authorities and national governments in pandemic management.

Before COVID-19, LRFs were accustomed to short-term disruptions that were less pervasive in their threat to human health and mortality, and with impacts that were geographically contained. To reiterate from the introduction, COVID-19 is the only instance when LRFs faced the same disruptive event simultaneously, thus permitting comparative insights on resilience governance. This is especially prescient given the array of weaknesses and vulnerabilities that the pandemic exposed in global–local systems and societies (McClelland et al., Citation2023). What the pandemic’s distinctiveness meant for the work of LRFs is further underlined in the findings section.

3.2. Local resilience forums (LRFs)

LRFs are multi-agency partnerships responsible under the 2004 Civil Contingencies Act for coordinating the preparation for, response to, and recovery from multiple types of disruption such as flooding, wildfires, or major transport accidents, often happening concurrently (Cabinet Office, Citation2013a). They operate within a national framework based on the subsidiarity principle in which decisions are ‘taken at the lowest appropriate level, with coordination at the highest necessary level’ (p. 14). Although not legal entities and without powers to direct members, LRFs are a key ‘statutory process’ in respect of major disruptions (Braithwaite, cited in Brassett & Vaughan-Williams, Citation2013, p. 234). They constitute the regional component of England’s resilience ‘governance fix’ (Coaffee & Wood, Citation2006).

The core membership of LRFs comprises Category 1 (e.g., ‘blue light’ services such as the police) and Category 2 responders (e.g., utility companies), most of which have statutory obligations to support people in need. The involvement of the Environment Agency – an executive non-departmental public body covering England – as well as advisors from the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, evidences their multilevel nature. Other public, private, voluntary and community sector organisations are also involved, including at the discretion of LRFs (Cabinet Office, Citation2013a). Each LRF spans and incorporates multiple local authorities, including higher tier authorities (e.g., county councils and combined authorities).

Critically, the nature and number of local authority and other partners varies across LRFs. The institutional geographies of some are relatively simple and contained, for example, with Cumbria LRF (no. 35 in ) consisting of two new unitary authorities (as of April 2023). Greater complexity is apparent elsewhere. For example, Thames Valley (no. 13 in ) contains 14 local authorities, both higher and lower tier, over a similar geographical footprint to Cumbria, and which differs considerably in terms of population size and urban–rural split. Additional to these local government geographies is the accumulation of other institutional boundaries, including fire and rescue services, National Health Service (NHS) integrated care boards, and local enterprise partnerships. These partners likewise vary in number across LRFs and further influence the degree of alignment between the various boundaries. Such a complicated and uneven landscape, as Newman and Kenny (Citation2023) discuss more broadly in relation to subnational governance in England, has major implications for collaboration and strategic coordination.

The characteristics of LRFs support their categorisation as soft spaces (): they are open, networked arenas where multisectoral, multilevel partners converge to focus on a limited range of aims, and which operate mostly via informal practices. They are not directly accountable to politicians, and issues of sovereignty and accountability are largely dispersed via their multi-agency partners. Although LRFs borders are nominally fixed – based on police areas such as Greater Manchester – they are not bounded, territorial entities and retain much discretion over their operational boundaries, which is particularly important given that disruptions typically transcend boundaries, scales, and institutional capacities. While many soft spaces elsewhere initially emerged with ‘fuzzy’ boundaries, this is not a pervasive or compulsory feature (e.g., Spaans & Zonneveld, Citation2015). However, the external boundaries of LRF activities may morph temporarily during a disruption (i.e., by collaborating with neighbouring LRFs), analogous to the ‘penumbral borders’ spoken of by Paasi and Zimmerbauer (Citation2016, p. 75), suggesting that they are neither ‘“hard” boundary lines nor “fuzzy borderscapes”’.

Further, LRFs are tethered to hard spaces, particularly during recovery, which implies greater political engagement given its long-term developmental nature (McClelland et al., Citation2023). The delivery and resourcing of recovery actions in the context of LRFs – agreed via a recovery strategy – is dispersed through partners such as local authorities. In part, this ensures accountability pathways through the democratic processes of territorial-based organisations.

Hardening and softening processes also characterise LRFs across key disaster management phases (e.g., response and recovery). On the one hand, the response is the space for short-term reactive activities, among other things, to save lives, protect property and maintain essential services. This is a more formal space with less room for discretionary behaviour and external engagement. Response is when LRFs’ hardness is most pronounced, with coordination operating on a command-and-control basis (e.g., the Strategic Co-ordinating Group usually chaired by senior police officer). On the other hand, recovery is when LRFs’ collaborative space softens to embrace wider multisectoral and community interests. Practices are less formal, and coordination is achieved on a consensus basis with greater emphasis on communication and engagement.

Response and recovery are ideally ‘taken forward in tandem from the outset’ of a disruption (Cabinet Office, Citation2013b, p. 17), meaning that hardening and softening processes typically overlap. Parallel response and recovery coordination structures under the auspices of the LRF generate, what Zimmerbauer and Paasi (Citation2020) call, an ‘in-between’ space of governance. These attributes prompt questions for resilience governance at the regional scale. What are the effects of the tethering of soft to hard spaces on resilience governance (e.g., dispersal of recovery activities via LRF partners)? Any loosening of strategic coordination and dissipation of collaboration would likely perpetuate the resilience implementation gap. Further, what does hybridity between soft and hard mean in the context of, and what are its effects on, resilience governance?

3.3. Methods and data analysis

Empirical insights are drawn from qualitative data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our primary source consists of 19 semi-structured interviews with 30 local authority chief executives and directors who were either chairs of recovery coordinating groups (RCG) or supported RCG chairs (see Appendix A in the supplemental data online). RCGs are established within the context of LRFs to coordinate recovery activities following major disruptions. A total of 17 LRFs are represented within our study – just under half of the 38 in England. Interviews, ranging in length from 40 to 80 min, happened online between December 2021 and June 2022, and were recorded and transcribed. Quotations from interviews illustrate key points within the findings (identified by interviewee numbers, e.g., R17).

Interviewees were recruited via our practice networks and selected based on their ability to speak on the strategic operation of LRFs during COVID-19 (Schutt, Citation2006). Access, rapport-development and trust was facilitated by our ethnographic work, which consisted of online meetings with RCGs and multiple local authorities. These were mutually beneficial interactions during which we imparted learning on recovery while gaining access as pandemic recovery activities were planned. Ethnography informed our questions and generated ‘outside–insider’ insights that add rigour and contextual depth to the study (Denzin, Citation2015). These observations, together with knowledge of policy documents, aided probing during interviews and triangulation of the data.

Our interview questions centred on pandemic recovery and renewal. Recovery is a transactional activity to enhance preparedness following a disruption, whereas renewal is a more transformational endeavour aimed at building resilience. Following Sou et al. (Citation2021, p. 10), we interpret renewal as a longer term perspective on recovery, which they define as:

The sustainable restoration or improvement of livelihoods and health, as well as economic, physical, social, cultural, and environmental assets, systems, and activities, of a disaster affected community or society, which reduces future disaster risk and tackles underlying causes of risk through transformational renewal initiatives.

4. FINDINGS

This section relays the empirical evidence emerging from our interviews. The narrative is structured by the three resilience implementation gap themes, namely collaboration, innovation and learning, and strategic coordination. Each subsection is further delineated by interrelated subthemes italicised within the text which invariably relate to the dynamic and hybrid dimensions of soft spaces introduced above (e.g., their tethering to hard spaces).

The pandemic’s distinctiveness requires cognisance of response alongside recovery. Its prolonged and non-linear nature in contrast to other disruptions, made it difficult at times to discern, in the words of one interviewee, ‘whether we were in response or recovery or both’ (R25). Such blurring of boundaries, shaped governance arrangements, as well as LRFs’ thinking on what recovery might look like, and how it could be achieved. As a health-led disruption, subnational actors played a somewhat reactive role in dealing with the secondary effects of control measures decided nationally (e.g., adapting spaces for social distancing). Rapid adjustments were made by LRFs to adapt their working and governance arrangements in a way not previously experienced (e.g., enabling online meetings), while the pandemic’s longevity posed challenges over managing ‘tiredness, fatigue, and staff mental health throughout’ (R26). We recognise that this represents an important context to the governance of pandemic recovery (and response) at the regional scale.

4.1. Collaboration

Effective pre-existing relationships were critical to collaboration in these soft spaces. Recent experience of disruptions influenced the trajectory of these relationships. For example, mobilising the LRF’s multisector ‘partnership of partnerships’ within one region with a history of flooding felt seamless when the pandemic began, and felt like ‘pressing a button’ (R20). Trusting relationships developed via common experiences was linked by another interviewee to attaining agility within collaboration: ‘if you don’t trust other people around the table … you’re going to be more guarded and less flexible’ (R2). Further, the continuity of challenges and relationships shared from pre-pandemic, particularly over tackling socio-economic inequalities, influenced how collaboration unfolded. In some areas, the pandemic even ‘galvanized a much better working relationship’, especially between the public and voluntary and community sectors (R27). These soft spaces had developed a maturity of working through collective experience of disruptions over time.

Harnessing partner networks provided a platform for the recovery activities of these soft spaces at the regional scale in the context of supportive pre-existing relationships. Again, pre-pandemic challenges informed perspectives on the most pressing issues and how their impacts might become more acute if mitigating measures were not taken (e.g., over homelessness). Well-established networks enabled the integration of pandemic recovery objectives into what LRF partners were ‘already doing’ as to policy priorities and governance (R16). This carried strategic benefits in ensuring accountability and political support could more readily be secured among partners – that is, when proposals were taken back to the hard spaces of partner organisations. Allied to this, by utilising pre-existing networks, there was no need to ‘recreate new forms of governance across the region’ (R23). Rather, many LRFs harnessed and branched out from key collaborative networks.

A widening of collaboration was needed to expand the soft space to address the cascading health and economic impacts. For example, ‘newly vulnerable’ groups emerged, including ‘people who'd never been in this situation before’ (e.g., businesses dependent on tourism) (R20). Pandemic recovery was recognised as being different to other disruptions, requiring that ‘the economy, skills, transport, public health, public safety, voluntary sector were all talking to each other … in a way that was more granular and more expansive than would probably have been the case otherwise’ (R23). Engagement was instigated and sustained by many LRFs with their soft space partners such as business, education, and other interests with whom previous interactions may have been limited. Novel communication challenges also presented, such as with the ‘messaging around COVID vaccinations’ (e.g., to overcome vaccine hesitancy) (R2). This issue was approached in one area via a new interfaith forum, which was indicative of the type of collaborations formed to improve interaction with diverse communities. This represented a softening of the collaborative space of LRFs.

Constraining influences on collaboration emerged – being a soft space is no guarantor of collaboration. Problematic footprints characterised areas where collaboration stalled or fragmented. A lack of coterminous borders among partners complicated working together. However, a more complex set of influences rendered LRF footprints challenging for collaboration. For example, ‘there wasn’t an appetite from the partners to do recovery work … at the [LRF] footprint level’ in one area (R6), with activities confined to the hard spaces of local authorities. Where this occurred, footprints spanned multiple authorities (e.g., combined, county, and district), each with varying powers, resources, and divergent priorities. Struggles extended to engaging voluntary and community sector organisations across the entire footprint ‘because there’s no relationship at that … level’ (R6). The discretionary nature of LRFs’ powers as soft spaces were insufficient during recovery to overcome the challenges presented by difficult geographies.

A further constraining influence on collaboration concerned how these soft spaces were challenged by problematic centre–local relations. Many LRFs talked about the difficulties of obtaining relevant data from central government, and the lack of advance warning or consultation on major policy decisions. Relating to the latter, one interviewee considered that there was an ‘unhelpful level of suspicion from central government’, which meant that local and regional actors often did not receive in a timely fashion ‘the information that we needed to make the right decisions’ (R26). Such challenges over vertical relationships were to a degree counteracted by improved horizontal collaboration. Pertinent economy recovery data was generated and shared among partners, for example, by local enterprise partnerships and combined authorities. This is indicative of the challenges and opportunities of the multilevel relationships formed within soft spaces.

4.2. Innovation and learning

Interviewees talked positively of the innovative practices implemented by LRFs and their hard space partners amid pandemic disruption. These included rapidly enacting flexible ways of working and service delivery (e.g., working from home), and the breaking down of silos to allow more internal cross-functional collaboration. A ‘change in risk appetite to get things done’ was detected (R2). The pandemic also contributed to demystifying the work of LRFs, particularly among local politicians, which is important given their tethering to local authorities especially during recovery. Whereas LRFs dominant focus on response had bracketed recovery previously as a ‘Cinderella phase’, recent experiences may make certain partners ‘think about recovery more seriously than they have done in the past’ (R1). Such innovations, many of which are being enfolded into post-pandemic practices, can help to narrow the resilience implementation gap.

However, concerns over political support and accountability tempered recovery ambitions. Several LRFs reoriented their thinking from a transformational to a transactional approach that offered an exit towards ‘business as usual’. Contributing to this moderation was the ‘stop–start’ nature of the pandemic which had an attritional impact on governance. The resource and capacity expended ‘firefighting’ during response (R15), which ‘never really went away’ (R20), lessened the ability of LRFs to pursue longer term agendas. Critically, ensuring political support within their hard space partners became increasingly difficult. Local political leaders were comfortable with response being ‘non-political’ (R10) within the multi-agency setting of these soft spaces, but recovery was different, and politicians ‘were getting quite twitchy … about taking everything back into sovereign bodies’ (R22). This impulse intensified given the prolonged ‘in-between’ period as the softer space of recovery coexisted uneasily in relation to the harder space of response. The tensions of this hybrid space had major implications for strategic coordination.

The pandemic illuminated future governance dilemmas over the prospective role of such soft spaces in progressing transformative regional resilience agendas. Shifting from LRFs current short-term focus poses fundamental questions, not least over whether they are suitable entities to lead such an agenda. One interviewee was told ‘on several occasions that renewal wasn’t the role of the local resilience forum’ (R7), suggesting a reluctancy among multi-agency partners, at least in one area, to envisage LRFs’ purview extending beyond response and a transactional recovery from disruptions. A major pandemic learning point within many LRFs was realisation of the structural limitations in their governance arrangements, which impedes their taking on a more ambitious role in resilience building. One local authority director (R2) encapsulated the challenge:

If you give the LRF that wider longer-term responsibility you probably need to completely redefine who is involved in it. You probably need to engage people with different competencies within it, and you probably need to open it up to political scrutiny.

4.3. Strategic coordination

Pandemic recovery activities dispersed through LRFs’ hard space partners, with local authority representatives taking a lead on strategic coordination via RCGs. What differentiated regions was the degree of coordination, both in determining what the activities should be, and the implementation mechanisms. Accountability and a willingness to collaborate, including across disparate geographies and local government tiers, were critical. Where footprint challenges manifested, LRF oversight tended to be ‘light touch’, and with low expectations (R6). For example, one area ‘split down’ into recovery groups at county levels, with county councils taking ownership of coordination within their respective geographies (R6). In another, comprising multiple local authorities and a combined authority, the LRF resolved that it could offer limited ‘added value’ (P17). Divergence was evident between those areas where LRFs’ were the primary vehicles for coordination, and those where this occurred via the hard spaces of smaller territorial authorities.

The value of strategic coordination via LRFs was most evident where recovery ambitions were highest. Pathways long-term were envisaged through integration into the delivery of pre-existing strategies such as public health (R20), or corporate business plans (R8). Because partners ‘had already signed up’ (R20), this was politically advantageous. Governance arrangements, including lead actors, resources, and delivery timeframes, were already allocated. Critically, those challenges requiring ‘system reengineering or substantive change’, for example, to address inequalities – the ‘renewal bit’ – were deemed to fit best within ‘medium-to-long-term’ strategies (R5). As the pandemic endured, the concurrent disruptions faced (e.g., Brexit) meant that ‘COVID recovery [became] part of a broader package of challenges’ (R25), including under the government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda (R14). Enmeshing of pandemic recovery with other concerns lessened the need for LRFs as coordinating bodies and hastened the standing down of RCGs.

A loosening in the strategic coordination of recovery occurred over time. This was evident across LRFs; a key differentiator being the rapidity with which it occurred. Where collaboration was limited at the regional scale, coordination was barely instigated or swiftly dissipated. Elsewhere, pressure for the dispersal of recovery activities through ‘sovereign bodies’ accumulated during the prolonged in-between period when response and recovery governance structures paralleled. On the one hand, this suggests a major tension between hard and soft during this hybrid period, at least when it extends over time. On the other hand, it indicates the clear tethering for accountability of the soft spaces of LRFs to the hard spaces of their constituent local authorities. However, including where recovery ambitions were high, and activities were migrated into pre-existing strategies, the ability of LRFs to ensure delivery over time at the regional scale remained limited.

5. DISCUSSION

Our focus on regional soft spaces has explored resilience implementation and governance to disruptions. Our questions relate to the tethering of soft spaces to hard spaces on resilience governance, including their interplay and hybridity. We now discuss our findings – concentrating on the tensions and opportunities to advance resilience governance through regional soft spaces.

5.1. Misaligned spaces

When soft space boundaries are defined top-down by national government, the misalignments generated challenge resilience implementation. Many soft spaces emerged from a voluntary mobilising of regional interests to create ‘temporary alignments of space’ to deal with issues crossing territorial boundaries (Cavaco et al., Citation2023, p. 15). For example, Thaler’s (Citation2016) exploration of flood-risk management identified soft spaces as key to the governance of river catchments. However, soft spaces with boundaries prescribed externally – LRFs being examples – are unlikely to reflect shared ambitions, strong ‘place identification’ (p. 334), or the historical identities that influence present-day governance (e.g., Gherhes et al., Citation2023). This resonates with the misalignments of English subnational administrative boundaries, which Newman and Kenny (Citation2023, p. 6) find to ‘cause confusion and uncertainty, and contribute to a lack of accountability’. A lack of coterminous borders among the patchwork of partners incorporated within top-down geographies contributes to scale mismatches. Significant mismatches were evident between the national and local scales during COVID-19, which Broadhurst and Gray (Citation2022, p. 84) relate to ineffective multilevel governance in which ‘decision-making was too often centrally controlled rather than devolved to the most appropriate scale’. Our findings evidence regional mismatches in the context of LRFs, which curtailed the formation and sustenance of collaborative relationships with adverse consequences for resilience implementation.

Additionally, the soft spaces of many LRFs helped to ‘decongest’ some of the fragmentation associated with networked, multilevel governance (Othengrafen et al., Citation2015). In other words, they enabled a cutting through of complexity and the development of a more focused action-based agenda. This was particularly apparent in relation to the assembling of intelligence and data pertinent to the response and recovery work of LRFs. Whereas frustration was expressed by many over the timely availability of locally relevant data from national government, regional actors were able to work horizontally through partners such as local enterprise partnerships, county councils, and combined authorities to generate their own data ecosystem.

Where collaboration via regional soft spaces was minimal, the level of strategic coordination achieved was low on the ‘ladder of coordination’ (Hanssen et al., Citation2013). Again, this had a constraining influence on resilience implementation, as evident in several LRF areas where recovery activities fragmented due in part to misaligned footprints. These footprints comprised a political geography encompassing dissimilar multitiered local authorities with divergent priorities, varying powers, and sometimes frictional relationships (e.g., between district and county councils). Consequently, coordination was confined to the mutual exchange of information and knowledge (Hanssen et al., Citation2013). Although unproblematic during response, the softer space of recovery was when the constraining effects of misaligned footprints manifested. The regional soft space of the LRF was not so much tethered to these harder spaces but disregarded. As with some soft spaces elsewhere, their softness hindered implementation ambitions (Caesar, Citation2017). But unlike other soft spaces that were ‘readily discarded’ and disappeared after a short time (Hincks et al., Citation2017, p. 644), LRFs will persist under the national civil contingencies’ framework (Cabinet Office, Citation2022).

5.2. Developing spatial imaginaries

Spatial imaginaries appear crucial for regional soft spaces of resilience governance to disruptions. According to Haughton and Allmendinger (Citation2015, p. 859), such imaginaries support governance coherence, partly by depicting a particular regional geography as the ‘“natural” and meaningful scale around which policy actors can cohere to undertake strategic work’. Spatial imaginaries draw upon discursive tactics (e.g., rhetorical claims) and material practices (e.g., strategies) to create shared identities that transcend territorial boundaries (Haughton & Allmendinger, Citation2015), thus aiding the formation of synergistic relationships. Yet this was not evident across some LRFs. The meaningful scale for action on pandemic recovery did not embrace the LRF as a regional soft space, but rather the smaller hard spaces such as county councils. Limited spatial imaginaries arguably influenced this disjunction and reinforced the effects of misaligned footprints.

The tethering of soft spaces to hard spaces can fuse short-term response and recovery activities with a longer term focus on resilience. A distinction is first needed between the soft spaces of regional planning, where spatial imaginaries are often discussed (e.g., Hincks et al., Citation2017), and others such as LRFs. The former engages narratives and maps to promote regional development trajectories, whereas the latter rarely employ spatial representations. Our findings suggest the benefits for regional soft spaces of aligning with a hard space actor with a proximate footprint and powers to create and sustain a regional spatial imaginary (e.g., a combined authority). For example, planning authorities are empowered to progress future-oriented visions for the ‘resilience-driven transformation’ of their regions, including through material interventions in the built environment – what Pitidis et al. (Citation2023, p. 702) call ‘resilience imaginaries’. Essentially, hard space actors can weave resilience-building into longer term strategies and implementation, while interlinking with regional soft spaces that maintain a focus on coordinating the more transactional shorter term recovery from disruption. This happened in several LRF areas during the pandemic.

However, such tethering at the regional scale is not possible everywhere given that a cause of misaligned footprints in some areas was the uneasy coexistence of multiple high-tier local authorities. Increased devolution to all parts of England beyond the metro-mayor city-regions proposed under the UK government’s Levelling Up White Paper (HMG, Citation2022), is unlikely to change this situation markedly, as it ‘risks a continuation of the patchwork, piecemeal approach’ on devolution experienced to date (Broadhurst & Gray, Citation2022, p. 100). This indicates further unevenness in the ability of these regional soft spaces to progress resilience implementation. Their tethering to hard spaces enmeshes LRFs within wider subnational governance structures, and they were impacted by the experimentation over the devolution of powers that has occurred over recent decades, with more change anticipated. Continuation of a piecemeal approach to devolution risks some regions getting further left behind in developing resilience governance to disruptions.

5.3. Tensions of the ‘in-between’ space of governance

Focusing on resilience to disruptions has illuminated tensions generated when regional soft spaces become hybrid. Through simultaneous hardening and softening in the transitionary period between response and recovery, LRFs became ‘in-between’ spaces of governance, ‘where soft and hard are elementally threshed over and navigated’ (Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2020, p. 786). As Melo Zurita et al. (Citation2015) explored, this transition involves an overlap between two approaches to coordination predicated on different logics. That is, between the hard space of command-and-control during response, and the softer space of recovery characterised by less formal practices that are more inclusive of wider interests. Tensions typically occur over the allocation of authority and responsibilities among actors under subsidiarity (Melo Zurita et al., Citation2015). What would usually be a short transition during a ‘normal’ disruption (e.g., localised flooding), extended inordinately during COVID-19. Within LRFs, the incompatibilities generated during this in-between period found expression through amplified pressure for greater political involvement in recovery coordination, and the accelerated decentralisation of recovery activities via their hard space partners.

Another benefit of our focus on disruptions is the underexplored temporal dimension that it allows in relation to the hardening and softening processes of regional soft spaces. For example, the timeframe of the evolutionary processes through which soft spaces referred to in the literature institutionalised, unfolded over many years (e.g., Mattila & Heinilä, Citation2022; Metzger & Schmitt, Citation2012; Stafford, Citation2023). We are unaware of equivalent research focusing on rapidly evolving contexts when the challenges faced by soft space actors in ‘real-time’ are urgent and intense as is the case with disruptions. The temporal dynamics in such cases are very different, with the processes of hardening and softening, sometimes happening concurrently, ebbing and flowing according to the situational logic over a shorter period. This temporal aspect and ‘time-contingent junctures’ are key to revealing the multilayered nature of regional spaces in respect of their borders and practices (Paasi & Zimmerbauer, Citation2016, p. 87).

5.4. (In)sufficient convening power

Inadequate convening power curtailed the ability of regional soft spaces to foster and sustain collaboration, innovation and learning, and strategic coordination. As Fastenrath and Coenen (Citation2021, p. 145) elaborated, such power is vital for ‘boundary management’ in bringing actors together and coordinating actions under a common agenda. This is difficult to achieve, and insufficient convening power was evident in those LRFs with misaligned footprints. However, even in those areas where recovery ambitions were high and collaborative relationships evolved, the convening power of LRFs is time-limited as their strategic coordination role dissipates with the decentralisation of recovery activities. A chief resilience officer (CRO) led the convening of city regional actors in respect of the Resilient Melbourne Strategy (Fastenrath & Coenen, Citation2021). Among the questions that arise from such a prospect for regional resilience governance in England (see below), is whether a CRO can overcome the collaborative challenges presented by misaligned spaces. The convening power of a CRO is arguably most relevant to building resilience to disruption via prevention and preparedness.

6. CONCLUSIONS: TOWARDS HARDENING AND SOFTENING?

A soft spaces lens has enabled a nuanced perspective on resilience governance to disruptions. Focusing on COVID-19, we have illuminated comparative insights on resilience governance in England and how the regional soft spaces of LRFs experienced such a momentous disruption simultaneously for the first time. The pandemic has tested the governance architecture of LRFs and their ability to enhance resilience to disruptions, which remains limited and requires attention if they are to narrow the resilience implementation gap. Tensions are apparent over the uneven impact of misaligned space; differing possibilities to create spatial imaginaries around which regional actors cohere; governance incompatibilities generated between hard and soft in the transitionary period between response and recovery; and an insufficiency of convening power to engender collaboration, innovation and learning, and strategic coordination.

However, the resilience governance landscape is evolving post-pandemic. Specifically, The UK Government Resilience Framework signals a shift in the focus of LRFs and an intended coalescing with wider interests ‘to deliver on a new strategic approach to resilience’ (Cabinet Office, Citation2022, p. 2). Although granular details are awaited, enacting the Resilience Framework may engender both a hardening and a softening of LRFs as regional soft spaces. For example, it indicates the adoption of a more expansive, longer term perspective on resilience with greater emphasis on preparation and prevention. This will involve closer integration with place-making and other policy agendas such as net zero and levelling up. A widening of collaborative opportunities is thus anticipated, which is indicative of a prospective softening (e.g., Harrison et al., Citation2017). Greater engagement with place-making also implies potential collaborative opportunities for hard and soft spaces to join up on future-oriented visions and spatial imaginaries.

Further, LRFs may become less informal, more accountable, and harder. This partly stems from the proposed creation of a CRO position, who will be expected to ‘lead the building of resilience and delivery of resilience activity’ within each LRF (Cabinet Office, Citation2022, p. 25). A CRO spanning policymaking and delivery can bolster their regional convening power. Allied to this, the CRO will be accountable to democratic leaders, which will provide a ‘mechanism for local communities to hold local leaders to account for driving and delivering resilience’ (Cabinet Office, Citation2022, p. 23). Yet, a common framework is still needed within which divergent approaches can be ‘considered and reconciled’ (Shaw & Maythorne, Citation2013, p.43). This is critical for resilience to become a strategic lynchpin around which regional actors across diverse policy areas including climate change converge. How the Resilience Framework unfolds is thus of keen interest for future research.

Focusing on regional soft spaces of resilience governance in theory and practice presents promising research prospects. Our focus in this article was on resilience amid disruption, but conceptualising the role of soft spaces in preventing and developing preparedness to disruptions is underexplored. The integration of resilience into the devolutionary and levelling up agendas is likewise significant, particularly as the resilience framework explicitly connects resilience with the UK’s levelling up mission. Finally, place-based leadership for enhancing resilience to disruption via regional soft spaces is a pertinent line of inquiry, especially in the context of persistent regional inequalities and the role of leadership in local and regional development (Vallance et al., Citation2019).

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval for the project on which this article is based was received from the University of Manchester’s Research Ethics Committee. In advance of interviews, participants were sent an information sheet detailing, among other things, the purpose of the project, what their involvement would entail (e.g., length of interview, how recorded, focus of questions), their right to withdraw at any time, and how their anonymity and confidentiality would be protected. Participants provided informed written consent by way of signing and returning a consent form. Verbal consent was also given prior to the recording of each interview.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (95 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to the editor(s) and anonymous reviewers for their consideration and insights throughout the peer-review process.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Allmendinger, P. (2016). Neoliberal spatial governance. Routledge.

- Allmendinger, P., & Haughton, G. (2009). Soft spaces, fuzzy boundaries, and metagovernance: The new spatial planning in the Thames Gateway. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 41(3), 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1068/a40208

- Allmendinger P., Haughton, G., Knieling, J., & Othengrafen, F. (2015). Soft spaces, planning and emerging practices of territorial governance. In A. Phil, H. Graham, K. Jörg, & O. Frank (Eds.), Soft spaces in Europe. Re-negotiating governance, boundaries and borders (pp. 3–22). Routledge.

- Bailey, D., Crescenzi, R., Roller, E., Anguelovski, I., Datta, A., & Harrison, J. (2021). Regions in COVID-19 recovery. Regional Studies, 55(12), 1955–1965. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.2003768

- Boyd, E., & Juhola, S. (2015). Adaptive climate change governance for urban resilience. Urban Studies, 52(7), 1234–1264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014527483

- Brassett, J., & Vaughan-Williams, N. (2013). The politics of resilience from a practitioner’s perspective: An interview with Helen Braithwaite OBE. Politics, 33(4), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.12027

- British Academy. (2021). The COVID decade: Understanding the long-term societal impacts of COVID-19. British Academy.

- Broadhurst, K., & Gray, N. (2022). Understanding resilient places: Multi-level governance in times of crisis. Local Economy, 37(1–2), 84–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/02690942221100101

- Cabinet Office. (2013a). The role of local resilience forums: A reference document.

- Cabinet Office. (2013b). Emergency response and recovery: Non statutory guidance accompanying the civil contingencies Act 2004.

- Cabinet Office. (2022). The UK government resilience framework. HM Government.

- Caesar, B. (2017). European groupings of territorial cooperation: A means to harden spatially dispersed cooperation? Regional Studies, Regional Science, 4(1), 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2017.1394216

- Cash, D. W., Adger, W., Berkes, F., Garden, P., Lebel, L., Olsson, P., Pritchard, L., & Young, O. (2006). Scale and cross-scale dynamics: Governance and information in a multilevel world. Ecology and Society, 11(2), 8. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01759-110208

- Cavaco, C., Mourato, J., Costa, J. P., & Ferrão, J. (2023). Beyond soft planning: Towards a soft turn in planning theory and practice? Planning Theory, 22(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952221087389

- Chelleri, L., Waters, J. J., Olazabal, M., & Minucci, G. (2015). Resilience trade-offs: Addressing multiple scales and temporal aspects of urban resilience. Environment and Urbanization, 27(1), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247814550780

- Chmutina, K., Lizarralde, G., Dainty, A., & Bosher, L. (2016). Unpacking resilience policy discourse. Cities, 58, 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.05.017

- Coaffee, J., et al. (2020). Complexity, uncertainty and resilience. In S. Davoudi (Ed.), The Routledge companion to environmental planning (pp. 93–102). Routledge.

- Coaffee, J., Therrien, M.-C., Chelleri, L., Henstra, D., Aldrich, D., Mitchell, C., Tsenkova, S., & Rigaud, É. (2018). Urban resilience implementation: A policy challenge and research agenda for the 21st century. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 26(3), 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12233

- Coaffee, J., & Wood, A. (2006). Security is coming home: Rethinking scale and constructing resilience in the global urban response to terrorist risk. International Relations, 20(4), 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117806069416

- Cutter, S. L. (2016). Resilience to what? Resilience for whom? The Geographical Journal, 182(2), 110–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12174

- Davoudi, S., Brooks, E., & Mehmood, A. (2013). Evolutionary resilience and strategies for climate adaptation. Planning Practice and Research, 28(3), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2013.787695

- Davoudi, S., Shaw, K., Haider, L. J., Quinlan, A. E., Peterson, G. D., Wilkinson, C., Fünfgeld, H., McEvoy, D., & Porter, L. (2012). Resilience: A bridging concept or a dead end? Planning Theory & Practice, 13(2), 299–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.677124

- Denzin, N. K. (2015). Triangulation. In G. Ritzer (Ed.), The Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology. Wiley.

- Dzigbede, K. D., Gehl, S. B., & Willoughby, K. (2020). Disaster resiliency of U.S. Local governments: Insights to strengthen local response and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Administration Review, 80(4), 634–643. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13249

- Fastenrath, S., & Coenen, L. (2021). Future-proof cities through governance experiments? Insights from the resilient Melbourne strategy (RMS). Regional Studies, 55(1), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1744551

- Fastiggi, M., Meerow, S., & Miller, T. R. (2021). Governing urban resilience: Organisational structures and coordination strategies in 20 north American city governments. Urban Studies, 58(6), 1262–1285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020907277

- Ferm, J., Trigo, S. F., & Moore-Cherry, N. (2022). Documenting the ‘soft spaces’ of London planning: Opportunity areas as institutional fix in a growth-oriented city. Regional Studies, 56(3), 394–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1902976

- Fitzgibbons, J., & Mitchell, C. L. (2019). Just urban futures? Exploring equity in ‘100 resilient cities’. World Development, 122, 648–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.06.021

- Gherhes, C., Hoole, C., & Vorley, T. (2023). The ‘imaginary’ challenge of remaking subnational governance: Regional identity and contested city-region-building in the UK. Regional Studies, 57(1), 153-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2054974

- Hanssen, G. S., Mydske, P. K., & Dahle, E. (2013). Multi-level coordination of climate change adaptation: By national hierarchical steering or by regional network governance? Local Environment, 18(8), 869–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.738657

- Harris, L. M., Chu, E. K., & Ziervogel, G. (2018). Negotiated resilience. Resilience, 6(3), 196–214.

- Harrison, J., Smith, D. P., & Kinton, C. (2017). Relational regions ‘in the making’: Institutionalizing new regional geographies of higher education. Regional Studies, 51(7), 1020–1034. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1301663

- Haughton, G., & Allmendinger, P. (2007). ‘Soft spaces’ in planning. Town & Country Planning, 76, 306–308.

- Haughton, G., & Allmendinger, P. (2015). Fluid spatial imaginaries: Evolving estuarial city-regional spaces. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(5), 857–873. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12211

- Haughton, G., Allmendinger, P., Counsell, D., & Vigar, G. (2010). The New spatial planning. Territorial management with soft spaces and fuzzy boundaries. Routledge.

- Haughton, G., Allmendinger, P., & Oosterlynck, S. (2013). Spaces of neoliberal experimentation: Soft spaces, postpolitics, and neoliberal governmentality. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 45(1), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4512

- Her Majesty’s Government. (2022). Levelling up the United Kingdom, presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities by command of Her Majesty, 2 February 2022. HMSO.

- Hincks, S., Deas, I., & Haughton, G. (2017). Real geographies, real economies and soft spatial imaginaries: Creating a ‘more than Manchester’ region. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 642–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12514

- Kythreotis, A. P., & Bristow, G. I. (2017). The ‘resilience trap’: Exploring the practical utility of resilience for climate change adaptation in UK city-regions. Regional Studies, 51(10), 1530–1541. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1200719

- Lebel, L., Anderies, J. M., Campbell, B., Folke, C., Hatfield-Dodds, S., Hughes, T. P., & Wilson, J. (2006). Governance and the capacity to manage resilience in regional social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 11(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01606-110119

- MacKinnon, D., & Derickson, K. D. (2013). From resilience to resourcefulness: A critique of resilience policy and activism. Progress in Human Geography, 37(2), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512454775

- Mattila, H., & Heinilä, A. (2022). Soft spaces, soft planning, soft law: Examining the institutionalisation of city-regional planning in Finland. Land Use Policy, 119, 106156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106156

- McClelland, A. G., Shaw, D., O’Grady, N., & Fattoum, A. (2023). Recovery for development: A multi-dimensional, practice-oriented framework for transformative change post-disaster. The Journal of Development Studies, 59(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2022.2130055

- Melo Zurita, M. L., Cook, B., Harms, L., & March, A. (2015). Towards New disaster governance: Subsidiarity as a critical tool. Environmental Policy and Governance, 25(6), 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1681

- Metzger, J., & Schmitt, P. (2012). When soft spaces harden: The EU strategy for the Baltic Sea region. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(2), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44188

- Newman, J., & Kenny, M. (2023). Devolving English government. Institute for Government.

- O'Brien, G., & Read, P. (2005). Future UK emergency management: New wine, old skin? Disaster Prevention and Management, 14(3), 353–361. https://doi.org/10.1108/09653560510605018

- O’Hare, P., White, I., & Connelly, A. (2015). Insurance as maladaptation: Resilience and the ‘business as usual’ paradox. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 34(6), 1175–1193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15602022

- Othengrafen, F., Knieling, J., Haughton, G., & Allmendinger, P. (2015). Conclusion – What difference Do soft spaces make? In A. Phil, H. Graham, K. Jörg, & O. Frank (Eds.), Soft spaces in Europe. Re-negotiating governance, boundaries and borders (pp. 215–235). Routledge.

- Paasi, A., & Zimmerbauer, K. (2016). Penumbral borders and planning paradoxes: Relational thinking and the question of borders in spatial planning. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15594805

- Pitidis, V., Coaffee, J., & Bouikidis, A. (2023). Creating ‘resilience imaginaries’ for city-regional planning. Regional Studies, 57(4), 609–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2047916

- Purkarthofer, E., & Granqvist, K. (2021). Soft spaces as a traveling planning idea: Uncovering the origin and development of an academic concept on the rise. Journal of Planning Literature, 36(3), 312–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412221992287

- Richmond, J. G., & Hill, R. (2023). Rethinking local resilience for extreme heat events. Public Health, 218, 146–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2023.03.005

- Schoch-Spana, M. (2020). An epidemic recovery framework to jump-start analysis, planning, and action on a neglected aspect of global health security. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 71(9), 2516–2520. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa486

- Schutt, R. K. (2006). Investigating the social world: The process and practice of research. Sage.

- Shaw, K., & Maythorne, L. (2013). Managing for local resilience: Towards a strategic approach. Public Policy and Administration, 28(1), 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076711432578

- Simmie, J., & Martin, R. (2010). The economic resilience of regions: Towards an evolutionary approach. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp029

- Sou, G., Shaw, D., & Aponte-Gonzalez, F. (2021). A multidimensional framework for disaster recovery: Longitudinal qualitative evidence from Puerto Rican households. World Development, 144, 105489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105489

- Spaans, M., & Zonneveld, W. (2015). Evolving regional spaces: Shifting spaces in the southern part of the Randstad. In A. Phil, H. Graham, K. Jörg, & O. Frank (Eds.), Soft spaces in Europe. Re-negotiating governance, boundaries and borders (pp. 95–128). Routledge.

- Stafford, I. (2023). The rise, fall and resurrection of soft spaces? The regional governance of transport policy in Wales. Regional Studies, 57(9), 1769–1783. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2151997

- Thaler, T. (2016). Moving away from local-based flood risk policy in Austria. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 3(1), 329–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2016.1195282

- United Nations. (2020). United nations common guidance on helping build resilient societies.

- Vale, L. J. (2014). The politics of resilient cities: Whose resilience and whose city? Building Research & Information, 42(2), 191–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2014.850602

- Vallance, P., Tewdwr-Jones, M., & Kempton, L. (2019). Facilitating spaces for place-based leadership in centralized governance systems: The case of Newcastle City Futures. Regional Studies, 53(12), 1723–1733. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1598620

- Wagenaar, H., & Wilkinson, C. (2015). Enacting resilience: A performative account of governing for urban resilience. Urban Studies, 52(7), 1265–1284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013505655

- Welsh, M. (2014). Resilience and responsibility. The Geographical Journal, 180(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12012

- White, I., & O’Hare, P. (2014). From rhetoric to reality: Which resilience, why resilience, and whose resilience in spatial planning? Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 32(5), 934–950. https://doi.org/10.1068/c12117

- Zimmerbauer, K., & Paasi, A. (2020). Hard work with soft spaces (and vice versa): Problematizing the transforming planning spaces. European Planning Studies, 28(4), 771–789. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1653827