?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

We investigate whether the development of regional disparities in entrepreneurship and innovation in Germany can be traced back to Roman rule 2000 years ago. We find a lasting positive Roman effect on the level and quality of entrepreneurship and innovation. This effect might be due to the imprint of local hard factors, such as interregional social and economic exchange, particularly emerging from the integration into the Roman Empire. This effect remains robust when a number of other significant historical developments are taken into account. We hope that these results stimulate a scholarly debate on the probably underestimated importance of ancient roots of economic development.

1. INTRODUCTION: FAR-REACHING HISTORICAL ROOTS

Exploring the connection between history and geography has emerged as a focal point in economic geography research (Martin & Sunley, Citation2022). Although history is widely acknowledged to cast a ‘long shadow’ over the economic trajectories of regions, the length of this shadow remains uncertain (Martin, Citation2021). Yet, a growing body of evidence indicates that historical events that may reach far back in time – possibly centuries or millennia ago – can affect economic outcomes today in profound ways (e.g., Alesina & Giuliano, Citation2015; Bazzi et al., Citation2020; Buggle & Durante, Citation2017; Giuliano & Nunn, Citation2013; Guiso et al., Citation2006; Lowes et al., Citation2017; Schulz et al., Citation2019). Moreover, going back to ancient high cultures to understand the nature and roots of entrepreneurship and innovation has guided seminal theorising on these topics (e.g., Baumol, Citation1990). However, our knowledge and understanding of such a long-lasting imprint of history is still rather limited.

Recent studies of regional entrepreneurship and innovation activity found indications for historical roots that date back more than a century (Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2023). For example, Fritsch and Wyrwich (Citation2018) and Fritsch et al. (Citation2019) showed for the case of Germany that many regions with high levels of self-employment and innovation activity today also had high levels of self-employment and innovation in the early 20th century. Since it is plausible to assume that entrepreneurship and innovation in the early 20th century did not come out of thin air, the underlying historical roots may reach much deeper. Further studies cite the role of historical industry specialisation (Glaeser et al., Citation2015; Stuetzer et al., Citation2016), historical events shaping the regional knowledge base (e.g., Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2018; Cosci et al., 2021), and entrepreneurship in earlier historical epochs (e.g., Opper & Andersson, Citation2019). At the same time, other factors such as agglomeration economies play no important role for persistence of entrepreneurship (Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2023). Previous studies do not go back in time to the degree we do in the current paper.

Throughout the course of history, regions are exposed to all kinds of events that shape their future developments, but these events may leave different effects, with some overshadowing and disrupting others. Scholars have developed a special interest in identifying those historical factors that left a particularly deep imprint in that they anchored persistent comparative economic advantage (Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012; Huggins et al., Citation2021). One can distinguish such historical imprint with respect to imprinting hard factors (e.g., establishing local infrastructure and other physical assets) versus imprinting soft factors (e.g., local entrepreneurial, innovative culture) (Saxenian, Citation1996). In the present study, we focus on the long-lasting effects of the occupation of certain parts of Germany by the Roman Empire about 1700 years ago on entrepreneurship and innovation activity in these regions today. Taking history more seriously via historical cognizance (Martin & Sunley, Citation2022), we postulate that one can expect such a deep imprinting effect in those regions that were part of the Roman Empire since the Roman civilisation was not only much more developed than that of the ‘Barbarians’ at that time, but it particularly offered abundant opportunities for entrepreneurship and innovation. In other words, the Roman occupation might have imprinted a local competitive advantage that is still detectable today.

Our analysis is consistent with the notion of a positive impact of Roman occupation on the quantity and quality of the level of entrepreneurship and innovation of today in the regions that were part of the Roman Empire. Our findings suggest that there was a Roman imprinting effect evident in the commercial activity and education levels during the late Middle Ages that encouraged entrepreneurship and innovation. The results remain robust when accounting for a number of important developments, such as membership in the Hanseatic League, massive cultural and socio-economic shocks, such as medieval plagues, the effect of the Napoleonic occupation, the massive inflow of German expellees from Eastern Europe after the Second World War, as well as German separation and reunification.

To better describe and test the potential Roman effect on current economic performance, we distinguish two potential transmission channels that are related to some degree. The first is the number of Roman markets and mines in a region that indicates the intensity of the direct historical imprint resulting from the level of economic activity and social exchange. The second transmission channel could be the massive increase in geographical mobility, social interaction and trade due to the network of roads that were built by the Romans and that shaped the geographical patterns of interregional relationships until today (Flückiger et al., Citation2021). We find a significantly positive effect for the regional density of the Roman road network, while the results for the number of Roman markets and mines are much weaker. Given the many disruptive shocks and the vast migration movements following the demise of the Roman Empire, this weaker effect of the direct historical imprint of Roman presence on these present-day outcomes is hardly surprising.

By analysing the nature and scope of the effect of Roman rule in Germany, we contribute to the literature on the nexus between history and path dependence (Martin, Citation2021), historical imprinting mechanisms (e.g., Diamond & Robinson, Citation2010; Nunn, Citation2009), and particularly the present-day geography of entrepreneurship, innovation (Cosci et al., Citation2022; Crescenzi et al., Citation2020; Fritsch et al., Citation2019) and its historical roots. The main novelty is that we focus on a specific, clearly defined historical epoch affecting entrepreneurship and innovation today. Most previous studies have considered long periods of time, specifically examining long time-series data, without considering an initial event or process. Hence, we are able to demonstrate the historical roots of current regional differences in entrepreneurship and innovation. In this sense, our study is informative about how single historical events influenced the current economic landscape. Another contribution of the paper lies in the fact that our analysis suggests that entrepreneurship and innovation are dominant channels through which the effect of the Romans on contemporary regional development levels can be explained. Although the development effect of the Romans is well documented by previous studies, the specific factors behind it have not yet been fully understood.

Given that innovation and entrepreneurship can be regarded as the key drivers of growth and represent economic vitality in modern economies, investigating their historical roots is of crucial importance. A better understanding of historical sources of innovation and entrepreneurship may be particularly helpful for respective policy promotion programmes, since the failure of such programmes may have to do with deep historical imprints that shape and maintain regional disparities (e.g., Huggins et al., Citation2021).

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 describes the Roman occupation and its direct impact in some more detail. Section 3 introduces data and definitions. Section 4 presents the results of the empirical investigation. Section 5 concludes.

2. ROMAN OCCUPATION IN GERMANY

2.1. The Roman Limes wall through Germany

The Romans constructed the Limes wall c.150 CE to protect their territory and its cultural and economic advancements. The Limes acted as a border between the Roman and Germanic cultures (Von Schnurbein, Citation1995) and marked the boundary of the Roman road network (McCormick et al., Citation2013). The wall served as the empire’s border for over a century and comprised three main rivers, namely the Rhine, Danube and Main (also known as ‘Main Limes’), as well as a physical wall. The wall consisted of the Upper Germanic and Rhaetian Limes, which were joined by the River Main. The walled portions of the border left physical remains, such as walls, towers, ditches, forest aisles and hills with stone rubble. Many Roman forts were also built along the wall, which helped to identify the course of the Roman border. However, the Romans abandoned the Limes in 275–76 CE following the invasion of German tribes and moved to positions west of the Rhine, south of the Danube and east of the River Iller.

In particular, the Limes was established to create a secure connection between the Roman provinces of Upper Germany and Rhaetia. Therefore, its course primarily reflects military and strategic considerations, rather than economic or engineering factors. The design of the Limes followed a straight line to facilitate border surveillance and communication between watch towers, and demonstrated the superior scientific knowledge of the Romans in the German barbaric area (Planck & Beck, Citation1987; Schallmayer, Citation2011; Wahl, Citation2017). This reasoning makes it unlikely that pre-existing economic conditions and path dependency shaped the location and course of the Limes.Footnote1

2.2. Pre-Roman characteristics of Germany

The Romans had initially planned to conquer a larger part of Germany, including the north, but eventually established the border of the empire along the Rhine and Danube rivers.Footnote2 Before Roman occupation, there were settlements of Germanic tribes in both the north and south of Germany. The area to the west and east of the later border was settled by Celtic tribes. Therefore, there is no reason to believe that northern Germany was less attractive to the Romans due to intrinsic detrimental characteristics.

It is also unlikely that the south of Germany was already better developed or that Roman settlement patterns are just a reflection of pre-Roman Celtic ones. In general, Roman settlement patterns looked significantly different than the Celtic ones, meaning that the most densely populated areas during Celtic times were not among the most densely populated areas during the Roman period (Wahl, Citation2017, has more evidence on this). Furthermore, there is evidence that south-west Germany was even almost uninhabited before the Roman conquest (Rieckhoff, Citation2008; Rieckhoff & Biel, Citation2001). Knowledge of producing iron tools and weapons was widespread throughout the whole area of what is Germany today for centuries before the Roman expansion, indicating that the Roman parts of Germany were not already better developed before the Roman presence (Kristiansen, Citation2000).

2.3. The Roman development effect

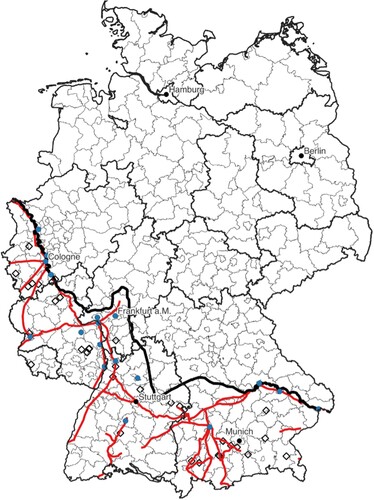

shows the course of the Limes Wall (the border of the Roman Empire with the Germanic tribes) through Germany c.200 CE,Footnote3 the main Roman roads, Roman markets and mines, as well as some contemporary large cities (for details regarding the Limes, see Appendix B in the supplemental data online; Wahl, Citation2017). When the Romans occupied certain parts of Germany (those south of the Limes) and made them part of their empire, they brought with them superior scientific knowledge and civilisation that – compared with the local tribes – was in many respects much more developed and offered abundant opportunities for entrepreneurship and innovation. Roman society was much wealthier and considerably more structured and organised with a quite effective public administration and a relatively well-elaborated legal system (Drexhage et al., Citation2002; Franke, Citation1980). That many state tasks were performed by private entrepreneurs – most importantly tax collection (Badian, Citation1980, Citation1997; Löffl, Citation2014) – suggests that a belief in the ability of the private economic sector to be efficient might have already existed during the Roman era.

Figure 1. The Limes Germanicus, Roman roads, markets, mines, current NUTS-3 regions and federal states.

Note: The Limes Germanicus (Upper Germanic and Rhaetian Limes) is the solid black line. Solid red lines are major Roman roads. Black diamonds indicate the location of a Roman market or mine. Thinner borders indicate NUTS-3 regions (counties); thicker borders indicate federal states. Blue dots are Roman settlements; black dots are main cities in contemporary Germany that did not exist as major settlements in the Roman era.

The Romans possessed a large part of the technological and natural scientific knowledge that existed at that time. They developed water mills, mining technologies and water supply systems (e.g., their well-known aqueducts), and many of their cities had sewerage systems (De Martino, Citation1985; Lucas, Citation2005; Schneider, Citation2005).Footnote4 There existed a quite well-educated upper class and a considerable literacy rate among the population. Actually, the Roman schooling system provided the basis for the later Western education systems in the Middle Ages and still today (Bloomer, Citation2011; Bonner, Citation1977).

The Roman economy of which the occupied German regions were part was characterised by a relatively pronounced division of labour. The presence of well-accepted money and a banking system facilitated economic exchange and financial relationships (Drexhage et al., Citation2002; Finley, Citation1973). Non-agricultural production was mainly at a small scale, but there were also some larger manufacturers. However, commercial activity, such as entrepreneurship, was of low prestige in Roman society and rather unpopular among the ‘upper class’ (Baumol, Citation1990; Finley, Citation1973). Hence, most of the entrepreneurs came from the lower classes, such as former slaves. In the occupied German territories, a considerable number of the entrepreneurs during the Roman period were natives of the local tribes (Badian, Citation1997).

An important cornerstone of the cultural and economic Romanisation of the occupied German territories was massive advancements in infrastructure. For example, the Romans built a road system that connected their German provinces to the rest of their empire. The road system built by the Romans had a strong influence on the geographical pattern of trade, mobility and social interactions. For a number of countries, Roman roads have been shown to have long-lasting effects by shaping the traffic infrastructure and urbanisation patterns that exist today (Daalgard et al., Citation2020; Wahl, Citation2017).Footnote5 Flückiger et al. (Citation2021) demonstrate that the Roman trade network throughout Europe is still important for understanding the trade patterns and the behaviour of cross-regional investments today. The authors explain the long-term persistence of this connectivity by a relatively high level of cultural integration in terms of converging values and preferences of the population, which may be due to dense and repeated social and economic interactions between the well-connected parts of the network.

Wahl (Citation2017) suggests that the Roman road network was an important channel of a ‘Roman development effect’ that can still be identified today. He showed that regions in the former Roman part that are within 100 km from the border of the Limes have significantly (at least 10%) higher night-light luminosity today than those within the same distance on the other side of the Limes. Closely related to this study, Daalgard et al. (Citation2020) investigated night-light intensity around the location of historical Roman roads, finding that not only night-light intensity but also the density of nearby historical settlements are notably and robustly larger. All these studies make use of the fact that, according to historical accounts and empirical tests, Roman roads follow an economically suboptimal path.Footnote6 Hence, the course and the location of Roman roads can be considered exogenous to Roman or pre-Roman economic patterns.Footnote7

2.4. Did the Romans leave a particularly deep imprint on entrepreneurship and innovation?

Beyond this general Roman development effect, the present study specifies the Roman imprint on entrepreneurship and innovation in Germany. To this end, we distinguish two types of imprinting effects. First, the direct influence of the Roman cultural civilisation that resulted from the integration into the Roman Empire gave the Roman region a first development advantage over the less advanced ‘barbaric’ regions on the other side of the Limes. This early comparative advantage might still exist today, in the form of more entrepreneurship and innovation. Second, indirect imprinting effects related to the formative and long-lasting infrastructure built by the Romans, particularly the road system and its heritage, conducive to entrepreneurship and innovation.

The direct civilisation-based imprinting effect due to the integration of the occupied area into the Roman Empire has many facets. It implies relatively early contact with and learning from a considerably more developed society with an advanced knowledge base, a higher level of economic organisation and labour division, as well as a wider geographical scale of economic interactions such as larger markets (De Martino, Citation1985). Therefore, there was ample opportunity for intensive knowledge spillover from the Romans to the local population, which was essential for the development of innovation and entrepreneurial ideas (e.g., Acs et al., Citation2009). It is quite likely that contact with Roman entrepreneurs led to demonstration and peer effects that were conducive to entrepreneurial spawning among the local population. Such a pattern would be in line with the abundant empirical evidence on the pivotal impact of role-modeling effects on the decision to become an entrepreneur (e.g., Bosma et al., Citation2012; Wyrwich et al., Citation2019). Locals working in Roman ventures may have acquired entrepreneurial skills by observing the behaviour of the owner-manager. Role-model effects are also a source of self-perpetuation and persistence of entrepreneurship over time (Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2018; Minniti, Citation2005) and may imply that regions that were part of the Roman Empire have an above-average level of (high-quality) entrepreneurship today. Knowledge transfer from the Romans to the local population had many channels, such as diverse types of cooperation and economic exchange or apprenticeship of locals in Roman-led firms. People from the local tribes also served in the Roman army (Coulston, Citation2016), which was an important repository of technological knowledge at that time with institutionalised training of the ‘engineers’ of the past (Goldsworthy, Citation2011).

Although the demise of the Roman Empire was followed by vast migration movements and many fundamental changes, some elements of the direct imprinting effect of the Romans in the occupied German area may have remained until today. An illustrative example of such a long-lasting effect of the adoption of advanced technology, managing methods and integration into larger markets in Roman times is the mining, preparation and export of basaltic millstones from the village of Mayen in the Eifel region. Due to geological specificities, the basaltic rock in that region has special properties that make it well suited for use as a millstone. In pre-Roman times, the local Celtic tribes produced and traded such millstones across a distance of up to 100 km. Demand by the Roman army,Footnote8 application of more advanced technology and export to other parts of the Roman Empire (e.g., France and Britain) led to a strong increase in the produced amounts of millstones involving up to 600 workers.Footnote9 The region considerably benefited from the production and trade of basaltic millstones until the late 19th century (for details, see Mangartz, Citation2008). Such centres of economic activity might have been characterised by pronounced incentives for creativity and innovation and may therefore have attracted people with entrepreneurial talent. In our empirical analysis, we use the number of Roman markets and mines in a region to test for such a lasting direct imprinting effect on innovation and entrepreneurship (see section 4.2).

An indirect long-term imprinting effect on entrepreneurship and innovation that is rooted in the former integration into the Roman Empire more than 1700 years ago could be higher levels of geographical mobility and interregional trade, particularly the knowledge transfer that was related to these activities. We know from previous research that the geographical structure of the road network built by the Romans strongly shaped the traffic infrastructure today and also has a significant effect on today’s structure of interregional trade relationships (Flückiger et al., Citation2021). Higher interregional mobility and interaction were not only important for the transfer of knowledge and economic development, but could very likely also have affected attitudes of the population that are important for innovation and entrepreneurial activity, such as tolerance toward strangers, openness to change, and new ideas, as well as a certain willingness and ability to bear risk (Tavassoli et al., Citation2021). Hence, even if a direct civilisation-based imprinting effect did not persist, the Roman road network might have fuelled the described indirect imprinting effect even long after the Romans had to give up their German provinces. In the empirical analysis, we use the density of Roman roads in a region to test for a persistent effect of the Romans on innovation and entrepreneurship.

Both the direct civilisation-based effect and the indirect long-term effect of geographical mobility and interregional trade may be a reason for the Roman development effect, why regions in the former Roman part of Germany are today wealthier in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and have higher population density with larger cities (Wahl, Citation2017). An important alternative hypothesis would suggest that any impact of the Romans on innovation and entrepreneurship may also be attributed to agglomeration economies resulting from city size and population density (Florida et al., Citation2017). The Romans established several cities in German territory, while urbanisation began much later in non-Roman German territory. However, since it has been shown that there is no significant positive relationship between population density, innovation and new business formation in Germany (Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2021a, Citation2021b),Footnote10 such a transfer channel via density and agglomeration is rather implausible.

3. DATA AND EMPIRICAL APPROACH

3.1. Data

In this section we discuss the data underlying our research. First, we discuss the data sources for the outcomes related to entrepreneurship and innovation. Second, we introduce the historical and geographical data that we use. Third, we provide some descriptive insights.

3.1.1. Outcomes related to entrepreneurship and innovation

The spatial framework of our analysis comprises the current 401 German NUTS-3 (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) regions (counties).Footnote11 We overlay shapefiles of the walled Limes parts and courses of the Danube, Rhine and Main, with one of the current borders of the counties. In doing so, we are able to assign the counties to the historical Roman area. We assign counties to the historical Roman area if their centroid (mid-point) is located within the Roman Empire.Footnote12

Since we are interested in the impact of the Roman regime on entrepreneurship and innovation today, we examine regional differences in both the quantity and quality of these activities. Quantity innovation activity is measured as the number of patents per region, taken from the RegPat database provided by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (Maraut et al., Citation2008). Patents as an innovation indicator have a number of advantages and disadvantages (for an overview, see Griliches, 1990; Nagaoka et al., Citation2010). A disadvantage of patents is that they represent only the first stage of the innovation process. Therefore, one does not know if, when or how an invention is applied in a new process or product (Feldman & Kogler, Citation2010). Another critical issue is that not all inventors and firms use patents to protect their intellectual property (Cohen et al., Citation2000). Hence, not all inventions are patented. Moreover, some inventors obtain multiple related patents for basically the same invention to block follow-up patents from rivals. There is also a clear indication that the economic value of patents varies significantly, indicating that their economic impact is unpredictable.

Patents are assigned to the region where the inventor has her or his residence. If a patent has more than one inventor, the count is divided by the number of inventors, and each inventor is assigned his/her share of that patent. We considered the average number of patent applications filed in the years 2008–16, with at least one inventor residing in the region per 10,000 workforce. Information on the size of the regional workforce comes from the labour market statistics of the German Federal Statistical Office. The share of research and development (R&D) employees accounts for innovative input and is an alternative proxy variable for the quantity of innovation in a region.

Focusing on quality innovation, we use common indicators for the originality and radicalness of a patent, provided by the OECD RegPat database (see Squicciarini et al., Citation2013, for details). Both measures are based on backward citations and are supposed to indicate inventions of relatively high quality in terms of technological and economic impact. While radicalness is measured by the number of International Patent Classification (IPC) classes of the patents that are cited by the focal patent, originality is measured by the breadth of the distribution across these IPC classes. We used the top 10% of German patents with respect to the OECD radicalness indicator and the originality indicator per priority year. There is also a recent critique arguing that this approach does not necessarily identify the most radical patents (Taalbi, Citation2022). As mentioned above, the use of patents comes with advantages and disadvantages.

Quantity entrepreneurship is measured by the average number of start-up companies per 10,000 economically active population in the period 2008–16. Information on the number of new businesses comes from the Enterprise Panel of the Center for European Economic Research (ZEW-Mannheim). These data are based on information from the largest German credit rating agency (Creditreform).Footnote13 We used the average regional start-up rates for a longer period of time in order to avoid possible bias related to short-term and stochastic effects.

Quality entrepreneurship is measured by means of the start-up rate in high-tech manufacturing industries, representing knowledge intensity that requires specific qualifications. Since high-tech start-ups are relatively likely to introduce risky innovations, setting up and running such a firm requires specific entrepreneurial attitudes and abilities. Moreover, start-ups in high-tech industries can be assumed to generate a particularly pronounced positive impact on regional development by being often economically or technologically more successful than other firms and by creating larger numbers of promising entrepreneurial opportunities for other firms.Footnote14

3.1.2. Historical and geographical data

For each region, we also create a variable for the number of Roman-era markets or mines. These variables are extracted shapefiles from the DARMC. Data on the course and coordinates of Roman roads are taken from the shapefile of McCormick et al. (Citation2013), who digitised the information in the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World.Footnote15 Based on these data, we calculate Roman road density (km of major Roman roads per km² of area) as an indicator of integration into the Roman Empire and an indirect long-term imprinting effect resulting (see section 2.2).

We calculate a host of historical variables at the county level, to account for competing factors explaining entrepreneurship and innovation today (for a detailed discussion, see Appendix C in the supplemental data online). Table A1 in Appendix A online provides an overview of the definition of variables and data sources.

3.1.3. Descriptives

Table A2 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online shows some descriptive statistics; and Table A3 online depicts correlations between the three indicators of Roman presence and the measures of regional entrepreneurial and innovative activities. This provides a first more suggestive indication of a relationship between Roman’s presence and contemporary levels of innovation and entrepreneurship.

Although many of these correlations are statistically significant, we find that the relationship between the number of Roman markets and mines and the outcome variables is relatively weak. The correlation of all three Roman variables and the number of radical patents over the workforce is insignificant. The statistical relationship between the dummy variable for Roman presence and Roman road density is considerably larger than between the Roman dummy and the number of Roman markets and mines. The correlation between the density of Roman roads and the number of Roman markets and mines is relatively low (0.2) but statistically significant.

3.2. Empirical approach

Our main analysis of the effect of the Romans on entrepreneurship and innovation in Germany is based on cross-sectional ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions. We estimate the equation:

(1)

(1) where

is one of our measures of regional innovative or entrepreneurial activity. The indices i and s represent counties (i) and federal states (s), respectively.

is the variable for a Roman effect that can have three alternative forms. First, a dummy variable for Roman presence that is equal to 1 if the centroid of region i is located in the historic Roman area. Second, the number of Roman markets and mines is supposed to measure the direct civilisation-based imprinting effect. Third, the density of Roman roads is assumed to indicate the indirect long-term imprinting effect (see section 2.3).

is a vector of geographical and historical control variables. Since the federal states (Länder) are an important level of policy making in Germany, we attempt to control for such effects by including dummy variables for these federal states which is

.

is the error term.Footnote16 We estimate heteroskedasticity robust standard errors throughout the analysis.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Results for Roman occupation

We begin the empirical analysis by investigating the relationship between innovation and historical Roman occupation. We find highly significant positive relationships between Roman occupation and the share of R&D employees as a measure of innovation input (, models 1–3) and the overall number of patents over the workforce as an indicator for innovation output (models 4–6). These relationships are rather robust when dummies for the federal states and further control variables are included.Footnote17 The positive relationship with Roman rule remains if only patents that are classified as being radical or original are taken into account (models 8 and 9).

Table 1. Innovation and Roman legacy.

In addition to the positive effects on quantity and quality innovation, formerly Roman regions also show significantly higher rates of quantity and quality entrepreneurship. Specifically, the data reveal a positive effect on the formation of new businesses in general (models 1–3 in ). The estimated coefficient for the Roman dummy increases quite considerably when federal state dummies and further control variables are included. These findings are also valid for start-ups in innovative manufacturing industries (models 4–6 in ). Higher start-up rates in high-tech manufacturing industries in the former Roman regions correspond to higher levels of innovation activities there (see Table A3 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online).

Table 2. Entrepreneurship and Roman legacy.

The size of this Roman effect on entrepreneurship and innovation is also quite considerable. For example, the Roman legacy is associated with, on average, around 25% more patents per 10,000 economically active people in historically Roman counties (according to , column 6), and at least three more start-ups per 10,000 economically active persons ().

We also investigated the relationship between Roman rule and earlier outcomes that, because if there is a persistent effect of the Romans, it should also be visible when looking at earlier outcomes. To this end, we explored data from the 15th and 16th centuries that indicate the level of education and local development, which are both crucial conditions for entrepreneurship and innovation. The results (reported in Appendix D in the supplemental data online) are in line with previous results on the persistent development effect of Roman legacies in Germany (Wahl, Citation2017), but also suggest that the Roman part of Germany had a higher educational level and more trading and commercial activity, and thus probably also a more developed entrepreneurial and innovative culture already in the Middle Ages.

4.2. Where does the effect of the Romans come from?

We focus on two mechanisms that may be responsible for the long-lasting effect of the Romans on current entrepreneurship and innovation: first, the number of Roman markets and mines; and second, the density of Roman roads that connected a region to other parts of the Roman Empire. Although the number of Roman markets and mines can be regarded as a measure of the intensity of the historical imprinting in Roman times that may have given these regions a head start, Roman road density represents the long-term effect of traffic infrastructure that considerably shaped the geographical pattern of mobility and the structure of interregional trade relationships through to today (see section 2.2). We substitute the dummy variable for the presence of Romans with these two variables (). There is a certain overlap between both measures (see Table A3 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online), and many cities located on Roman roads that were not original centres of the Roman economy in Germania developed into trade centres in later periods. In this sense, one may suppose that the effect of markets and mines is likely to pick up an ‘early start advantage’ of the original Roman economic centres.

Table 3. Entrepreneurship, innovation and Roman legacy: accounting for potential mechanisms.

According to the results, the density of the road infrastructure built by the Romans shows a statistically significant and positive effect on all outcome variables, with the exception of the overall number of patents over the workforce, which is significantly related to the number of markets and mines. Our measure for Roman markets and mines is always insignificant for the other outcomes. These results suggest that access to Roman roads – the indirect long-term imprinting effect (see section 2.3) – is the dominant channel through which the effect of the Romans transmits to entrepreneurship and the ability of groundbreaking innovations today.Footnote18

4.3. Results for imprinting effects of further historical events

Given the rather long period of time between the Roman occupation and today, other major historical events that occurred during this period may also have had a long-term imprinting effect, shaping regional outcomes. Two such events are of special interest in our case.

The first of such events is the French occupation of several areas of Germany during the Napoleonic period in the early 19th century, which, among other things, induced the early adoptionFootnote19 of the Code Napoleon (Buggle, Citation2016). The Code Napoleon introduced equality before the law and led to the abolition of guilds and trade licences, thereby significantly enhancing economic freedom and creating entrepreneurial opportunities for large parts of the population. As shown by Donges et al. (Citation2021), the Code Napoleon had positive effects on innovative activities and especially on high-tech innovations measured by patents.

The second event is the labour demand shock caused by the influx of refugees from the previously German areas of Eastern Europe after the Second World War. At that time, Germany was divided into four Allied occupation zones, and the zone in the south-west of Germany that was governed by France was the only one that did not allow immigration of these refugees. As a consequence, the area of the French occupation zone experienced lower population growth at least until the 1970s (Schumann, Citation2014; Wyrwich, Citation2020). Since both events were limited to areas on the Roman side of the Limes, they may confound our results with regard to the effects of Roman occupation. To account for these two events, we make use of two dummies equal to 1 if a county is located in the area occupied by Napoleon in 1804 or within the French occupation zone after 1945, respectively. We create these variables using information about the border of the French-occupied territories that introduced the Code Napoleon in 1804 (from Buggle, Citation2016) and of the French occupation zone (from Schumann, Citation2014).Footnote20

To examine the impact of these variables and their effect on the Roman dummy coefficient, we incorporated both into the regression models alongside a complete range of controls, as detailed in and . reports the results of these extended specifications. Most importantly, the coefficient of the Roman dummy remains virtually unchanged and significant for all outcome variables. It is evident from this result that the Roman effect cannot be attributed to the other two historical events. The dummy variable for the French occupation zone is insignificant in almost all models and only shows a significantly negative effect on the share of R&D employees. The Code Napoleon dummy seems to positively and significantly affect the number of highly original and radical patents per workforce, but not the overall number of patents per workforce.

Table 4. The Roman effect when controlling for Napoleon and the French occupation after the Second World War.

It could be an issue that regional differences in entrepreneurship and innovation are mainly a result of regional prosperity and structural differences rather than caused by unique historical events. According to both empirical and conceptual literature, entrepreneurship and innovation have an impact on regional prosperity, including GDP and employment growth, rather than the other way around (e.g., Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2017; Glaeser et al., Citation2015). Therefore, we suspect that differences in regional wealth are not falling from heaven but link to entrepreneurship and innovation, which, in turn, are affected by historical events such as Roman occupation. We hypothesise that regional variations in GDP are the result of economic endeavours such as the establishment of businesses or research and development leading to patent registration. To confirm our theory, we perform a mediation analysis ().

Table 5. Roman legacy, entrepreneurship, innovation and regional economic development – mediation analysis.

According to previous research (Daalgard et al., Citation2020; Wahl, Citation2017), our analysis confirms that there is a direct and significant positive effect of the Romans on regional economic development measured by regional GDP per capita (averaged over the period 1992–2019) (model 1). The regressions in columns (2) and (3) repeat the regressions in the baseline and , once again showing the significantly positive relationship between the Romans and both patents and start-up activities. We can also confirm a significant positive relationship between the rates of start-ups and patents on GDP per capita (models 4–6). The regression in column (7) shows that the Roman effect becomes insignificant when regional start-up rates are included in the estimation specification. The regression in column (8) suggests that, in contrast, the Roman effect remains significant and sizeable when we include patenting activity to the model, which also has a significant and positive coefficient. However, if both start-up rates and patenting activity are included together with the Roman dummy (model 9) only the start-up rate remains statistically significant. Overall, these findings suggest that the influence of the Romans on economic growth, as observed in prior studies, is mediated by their effect on local levels of entrepreneurship.

In order to make sure that what we are picking up with our regressions is not just the Roman development effect, but particularly an effect on innovative and entrepreneurial activity that goes beyond the well-documented Roman development effect, we run our baseline models including GDP per capita despite our concerns that this variable is a bad control (see Table E1 in Appendix E in the supplemental data online). It turns out that the Roman effect is slightly reduced for most outcomes but remains both economically and statistically highly significant in all cases. GDP per capita, in contrast, is significantly positively related to most outcomes, but to radical and original patents. This can be regarded as an indication that the effect of the Romans on these specific high-value patents is unique and independent of their effect on overall economic development. Given the bad control problem, one should be careful when interpreting these results and not read too much into them.

4.4. Further robustness checks

We run additional robustness checks, reported in Appendix E in the supplemental data online. In these models, we included additional control variables, alternative measures for potentially relevant factors, and a varying number of regional units (see Tables E2–E5 in Appendix E in the supplemental data online).

The most important of these checks is testing how the results change when we exclude all counties in federal states that are completely outside of the historically Roman area (see Table E4 in Appendix E in the supplemental data online).Footnote21 This is important to further reduce concern that unobserved heterogeneity drives our results and to come closer to the idea of a spatial regression discontinuity design (RDD) around the Roman border. It also ensures that what we pick up is not just north–south or west–east development differences. When regressions are run with this reduced sample, the Roman dummy remains statistically significant for all the outcomes considered. Thus, our findings do not reflect any overall north–south or east–west patterns of development and remain consistent even for counties located in federal states that are divided by the historical Roman border. In sum, our results and conclusions remain fully intact after these additional robustness checks.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Linking ancient events to current economic trajectories of regions is a challenging empirical undertaking, given the complex nature of the mechanisms involved, as well as the scarcity of data that span such a significant period of time. However, it has become clear that if we really want to identify the effects of historical roots, we have to take history very seriously by advancing our theoretical and empirical knowledge in this field (Martin, Citation2021; Martin & Sunley, Citation2022). This article presented empirical evidence for a statistically significant relationship between being part of the Roman Empire about 1700 years ago and current regional disparities in terms of quantity and quality of entrepreneurial activity, as well as innovation. These statistical relationships remain rather robust when controlling for several alternative explanations that do not go directly back to Roman occupation, such as general locational characteristics or other historical events, such as the Napoleonic occupation in the early 19th century.

It is important to approach the mechanisms behind the Roman effect with caution when relying solely on single explanation models. However, our data suggest that the density of the Roman road network, and its lasting impact as a challenging location factor, played a significant role in the transmission of this imprint over time. The establishment of a road network in the formerly Roman parts of Germany facilitated interregional mobility and interaction within these regions and particularly linked them to other parts of the Roman Empire.

Another Roman legacy that may explain a relationship between Roman occupation and current innovation and entrepreneurship is the presence of Roman markets and mines, indicating high levels of economic activity and social exchange between Romans and members of German tribes. Such high levels of activity may have created pronounced incentives for creativity, innovation, and commercialisation that could have attracted like-minded people to these places. In our statistical analysis, the number of Roman markets and mines turned out to be statistically significant for patents per workforce, but the relationship was not as strong as the impact of the density of Roman roads.

Altogether, there is now growing evidence that Roman rule left a deep, long-term imprint on regional development in Germany, supporting the notion that the ‘shadow of history’ is indeed very long. Our study specifies how this Roman effect could have shaped entrepreneurship and innovation activities through a massive and lasting anchoring of better hard (and potentially soft) factors beneficial for entrepreneurship and innovation.

These preliminary, but rather astonishing empirical patterns that we have presented here call for more research on such deep imprinting effects of historical events. What were the defining characteristics of historical events that could have had significant and long-lasting effects on the respective regions? What are the mechanisms behind the long-term persistence of such effects despite several rather disruptive shocks, including massive in- and out-migration? Even more importantly, what are the concrete implications for economic policies addressing current and future entrepreneurial and innovative activity and the underlying culture in regions (Huggins et al., Citation2021)? Is there something such as the ‘spirit’ of a place – or what Alfred Marshall (Citation1920) suspected to be ‘in the air’ that can be traced back to historical roots and different forms of imprinting effects? Does a region-specific, place-based ‘cultural memory’ (Gieryn, Citation2000; Olick et al., Citation2011; Zukin, Citation2011) play a role here that lies dormant for some longer period of time until triggered by specific events? What are the relevant hard and soft artifacts by which ancient events and cultures have shaped today’s regions?

From this perspective, one has to conclude that the link between history and path dependency is probably much deeper than what is commonly believed. It seems such as we have just begun to scratch the surface of this relationship.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (395.2 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This is further substantiated by a probit regression shown in Table E8 in Appendix E in the supplemental data online, implying that geographical and historical characteristics, such as soil quality, elevation, location at rivers or the number of Celtic oppida, do not significantly predict whether or not a county was conquered by the Romans.

2. The defeat in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (9 CE) played a significant role in the Romans’ decision to retreat to their previous positions west of the Rhine and south of the Danube. Nevertheless, the successors of Tiberius repeatedly tried to reconquer parts of Germania east of the Rhine (Riemer, Citation2006; Wolters, Citation2011).

3. Based on a shapefile of European borders from the Digital Atlas of Roman and Medieval Civilizations (DARMC) by McCormick et al. (Citation2013), which is the digital version of Talbert’s (Citation2000) atlas. For the DARMC, see http://darmc.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do?keyword=k40248&pageid=icb.page188865/. Regarding Roman roads, we limit ourselves to roads that are classified by Talbert to be certain and major. We do not show the location of earlier border walls such as the ‘Odenwald Limes’.

4. It is remarkable that the Romans hardly conducted any basic research but applied existing knowledge mainly in a problem-oriented learning-by-doing mode. Large parts of the technological knowledge were present in the powerful Roman army that was frequently involved in setting up infrastructure facilities.

5. For example, around 87% of the contemporary highways in the Roman areas of Germany are located within 10 km of a Roman road (Wahl, Citation2017).

6. The reason may be that these roads were primarily built for military purposes (e.g., moving troops from one location to another) without accounting for terrain characteristics such as elevation or slope – which would be important for the efficient transportation of goods with oxen or by foot.

7. Michaels and Rauch (Citation2017) came to a more nuanced conclusion about the effect of the Romans on subsequent developments. Investigating urbanisation in Britain and France from the Roman era until today, they found that the breakdown of the Western Roman Empire ended urbanisation in Britain, but not in France. When urbanisation started again in the medieval period, towns in France were often rebuilt or founded on old Roman town locations. In England, where Roman rule ended considerably earlier than in France, the urban network of Roman roads did not persist. Much later, new towns emerged close to the coast or at navigable waterways. This gave these newly emerging cities a decisive advantage over their counterparts from the Roman period, as access to waterways became a decisive growth factor for cities only after the time of Roman occupation.

8. In the Roman army of that time, smaller groups of soldiers used to share a small handmill for grinding grain. Handmills with millstones from the Eifel region were widely used in the Roman army because of their higher productivity and because their use led to lower levels of mechanical wear. It is estimated that production of handmills with these millstones over the entire Roman period may have amounted to about 17 million units (Mangartz, Citation2008).

9. Mining of the basalt stones was organised in several open pits that were operated by private entrepreneurs.

10. There is, however, a slightly higher level of start-ups in innovative industries set up in some larger cities.

11. Shapefiles for the borders of the counties and federal states are from the Federal Agency of Cartography and Geodesy (Bundesamt für Kartographie and Geodäsie). They are freely available at https://gdz.bkg.bund.de/index.php/default/digitale-geodaten/verwaltungsgebiete/verwaltungsgebiete-1-250-000-ebenen-stand-01-01-vg250-ebenen-01-01.html

12. This pertains to 150 of the 401 counties.

13. As with many other data sources on start-ups, these data may not completely cover the case of solo entrepreneurs. However, once a firm is registered, hires employees, requests a bank loan or conducts reasonable economic activities, even solo entrepreneurs are included, and information about their activities is gathered beginning with the ‘true’ date the firm was established. Hence, many solo entrepreneurs are captured along with the correct business founding date. This information is limited to the set-up of a firm’s headquarters and does not include the establishment of branches. For details, see Bersch et al. (Citation2014).

14. The definition of high-tech start-ups is based on the common classification of industries according to their innovativeness as measured by their share of research and development (R&D) inputs (OECD, Citation2005; Gehrke et al., Citation2010). A problem of this classification is that industry affiliation is a fuzzy criterion because there may be innovative and not so innovative firms in all industries. However, given the limited availability of data on the innovativeness of individual businesses, this is often the only feasible way to identify new businesses as being innovative (for details, see Fritsch, Citation2011). New businesses in innovative manufacturing industries make up only a rather small fraction of all start-ups. In the 2008–16 period the average share is below 0.8%.

15. For the data, see https://harvard-cga.maps.arcgis.com/apps/View/index.html?appid=b38db47e08ca40f3a409c455ebb688db (latest accessed 27 June 2021). The course, building and characteristics of Roman roads have been extensively studied by historians and archaeologists (e.g., Laurence, Citation1999). From such works, the Roman road network can be reconstructed with some certainty. Nevertheless, for some of the roads, there is a scholarly disagreement about their exact course. These roads are classified in the Barrington Atlas as being uncertain and are excluded from the subsequent analysis.

16. Given that any effect of the Romans on innovation and entrepreneurship may also work through agglomeration economies (see section 2.3) including variables for current population density or city size would be faced with the problem of ‘bad controls’ (Angrist & Pischke, Citation2009). Since Fritsch and Wyrwich (Citation2021a, Citation2021b) showed that there is no significant relationship between these measures for agglomeration, innovation activities and entrepreneurship in Germany, such an indirect effect of the Romans via population density is not needed. Note that we do control for the settlement structure at Roman times by including the number of Celtic oppida.

17. In the case of patents over workforce (columns 4 and 5) the coefficient does, however, drastically decrease from 0.876 to 0.277. This is because the federal state fixed-effects are jointly significant and explain alone around 30% of the variation in this variable (R² increases from around 0.2 to around 0.5 when they are included). Thus, heterogeneity across different federal states is apparently very important for regional understanding differences in patenting activity. Nevertheless, the Roman dummy remains both economically as well as statistically significant.

18. One concern with the regressions in is that Roman roads, market and mines are only present in the Roman part of Germany. This is not optimal as these regressions then could reflect both variation within Roman Germany as well as variation between Roman Germany and non-Roman Germany. To address this problem, we estimate regressions where we explain the outcomes with the Roman dummy but limit the sample to (1) only counties with Roman roads and non-Roman counties, (2) counties with Roman markets or mines and non-Roman counties, and (3) Roman counties without a market, mine or road and non-Roman counties – giving us an idea whether some direct effect of the Romans remains even for Roman regions without roads or markets and mines. These are shown in Table F1 in Appendix F in the supplemental data online. The results show that the Roman effect is there both for (1) and (2) but the coefficients (with the exception of radical patents) are notably larger in the first set of regressions, where we compare counties with a Roman market or mine to non-Roman counties. This indicates that while both roads and markets/mines have a significant effect, the effect of markets and mines is larger in particular for overall patenting activity and entrepreneurship. Furthermore, when comparing Roman counties without a road, market or mine with non-Roman counties we do find much smaller and sometimes even insignificant effects for the share of R&D employees and patent activity. With respect to entrepreneurship, however, we actually find effects that look similar to those for Roman counties with markets or mines. Therefore, there seem to be additional channels through which the Romans have influenced entrepreneurship.

19. The Code Napoleon was introduced in all French territories in 1804. Later on it was also adopted in some other regions and particularly led to rather similiar regulations in many parts of Germany over the course of the 19th century.

20. For descriptive statistics of both dummy variables, see Table A2 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online.

21. This means that we drop 10 of the 16 federal states and only keep the six which are fully or partly located within the historical borders of the Roman Empire (Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Hesse, North-Rhine Westphalia, Rhineland-Palatinate and the Saarland).

REFERENCES

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown.

- Acs, Z. J., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9157-3

- Alesina, A., & Giuliano, P. (2015). Culture and institutions. Journal of Economic Literature, 53(4), 898–944. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.53.4.898

- Angrist, J., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricists guide. Princeton University Press.

- Badian, E. (1980). Römischer Imperialismus. Teubner-Studienbücher Geschichte.

- Badian, E. (1997). Zöllner und Sünder-Unternehmer im Dienst der Römischen Republik. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Baumol, W. J. (1990). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5, Part 1), 893–921. https://doi.org/10.1086/261712

- Bazzi, S., Fiszbein, M., & Gebresilasse, M. (2020). Frontier culture: The roots and persistence of ‘rugged individualism’ in the United States. Econometrica, 88(6), 2329–2368. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA16484

- Bersch, J., Gottschalk, S., Müller, B., Niefert, M. (2014) The Mannheim enterprise panel (MUP) and firm statistics for Germany. ZEW discussion paper No. 14-104. ZEW. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2548385

- Biraben, J.-N. (1975). Les hommes et la peste en France et dans les pays Europeens et Mediteraneens: Le peste dans l’histoire. Mouton.

- Bloomer, M. W. (2011). The school of Rome: Latin studies and the origin of liberal education. University of California Press.

- Bonner, S. (1977). Education in ancient Rome. From the Elder Cato to Younger Pliny. Routledge.

- Bosma, N., Hessels, J., Schutjens, V., van Praag, M., & Verheul, I. (2012). Entrepreneurship and role models. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(2), 410–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.03.004

- Buggle, J. (2016). Law and social capital: Evidence from the Code Napoleon in Germany. European Economic Review, 87, 148–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.05.003

- Buggle, J., & Durante, R. (2017). Climate risk, cooperation and the co-evolution of culture and institutions (DP12380). Centre for Economic Policy Research. http://www.cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=12380

- Büntgen, U., Ginzler, C., Esper, J., Tegel, W., & McMichael, A. J. (2012). Digitizing historical plague. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 95(11), 1586–1588. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis723

- Christakos, G., Olea, R. A., Serre, M. L., Yu, H.-L., & Wong, L.-L. (2005). Interdisciplinary public health reasoning and epidemic modelling: The case of Black Death. Springer.

- Cohen, W. M., Nelson, R. R., & Walsh, J. P. (2000). Protecting their intellectual assets: Appropriability conditions and why U.S. manufacturing firms patent (or not) (working Paper No. 7552). National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). https://www.nber.org/papers/w7552

- Cosci, S., Meliciani, V., & Pini, M. (2022). Historical roots of innovative entrepreneurial culture: The case of Italian regions. Regional Studies, 56(10), 1683–1697. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.2002838

- Coulston, J. C. N. (2016). Mercenaries, Roman. In Oxford classical dictionary. https://oxfordre.com/classics/view/10.1093acrefore/9780199381135.001.0001/acrefore-9780199381135-e-7256

- Crescenzi, R., Iammarino, S., Ioramashvili, C., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2020). The geography of innovation and development: Global spread and local hotspots. Papers in economic geography and spatial economics. London School of Economics. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/105116

- Daalgard, C.-J., Kaarsen, N., Olsson, O., & Selaya, P. (2020). Roman roads to prosperity: Persistence and non-persistence of public goods provision (Working Papers in Economics). University of Gothenburg, Department of Economics.

- De Martino, F. (1985) Wirtschaftsgeschichte des alten Rom. C.H. Beck.

- Diamond, J., & Robinson, J. A. (Eds.). (2010). Natural experiments of history. Harvard University Press.

- Dollinger, P. (1966). Die Hanse. Alfred Kröner.

- Donges, A., Meier, J.-M., & Silva, R. C. (2021). The impact of institutions on innovation (DP16212). Centre for Economic Policy Research. https://cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=16212

- Drexhage, H.-J., Konen, H., & Rüffing, K. (2002). Die wirtschaft des römischen reiches (1.−3. Jahrhundert). eine einführung. Akademie Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783050077215

- Feldman, M., & Kogler, D. (2010). Stylized facts in the geography of innovation. In B. H. Hall, & N. Rosenberg (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of innovation (Vol. 1, pp. 381–410). North Holland. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-7218(10)01008-7

- Finley, M. I. (1973). The ancient economy. University of California Press.

- Florida, R., Adler, P., & Mellander, C. (2017). The city as innovation machine. Regional Studies, 51(1), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1255324

- Flückiger, M., Larch, M., Ludwig, M., & Mees, A. (2021). Roman transport network connectivity and economic integration. The Review of Economic Studies, https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdab036

- Franke, A. (1980). Rom und die Germanen. Das neue Bild der Deutschen Frühgeschichte. Grabert.

- Fritsch, M. (2011). Start-ups in innovative industries—causes and effects. In D. B. Audretsch, O. Falck, S. Heblich, & A. Lederer (Eds.), Handbook of innovation and entrepreneurship (pp. 365–381). Elgar.

- Fritsch, M., Obschonka, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2019). Historical roots of entrepreneurial culture and innovation activity – An analysis for German regions. Regional Studies, 53(9), 1296–1307. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1580357

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2017). The effect of entrepreneurship on economic development – An empirical analysis using regional entrepreneurship culture. Journal of Economic Geography, 17(1), 157–189. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbv049

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2018). Regional knowledge, entrepreneurial culture and innovative start-ups over time and space – An empirical investigation. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0016-6

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2021a). Is innovation (increasingly) concentrated in large cities? An international comparison. Research Policy, 50(6), 104237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2021.104237

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2021b). Does successful innovation require large cities? Germany as a counterexample. Economic Geography, 97, 284–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.1920391

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2023). Entrepreneurship in the long Run: Empirical evidence and historical mechanisms. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 19(1), 1–125. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000100

- Gehrke, B., Schasse, U., Rammer, C., Frietsch, R., Neuhäusler, P., & Leidmann, M. (2010). Listen wissens- und technologieintensiver Güter und Wirtschaftszweige. In Studien zum Deutschen Innovationssystem, 19–2010. Frauenhofer ISI, NIW, ZEW. https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/156548

- Gieryn, T. F. (2000). A space for place in sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 463–496. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.463

- Giuliano, P., & Nunn, N. (2013). The transmission of democracy: From the village to the nation-state. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 103(3), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.3.86

- Glaeser, E. L., Kerr, S. P., & Kerr, W. R. (2015). Entrepreneurship and urban growth: An empirical assessment with historical mines. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97(2), 498–520. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00456

- Goldsworthy, A. (2011). The complete Roman army. Thames & Hudson.

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2006). Does culture affect economic outcomes? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2), 23–48. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.20.2.23

- Hager, A., & Hilbig, H. (2019). Do inheritance customs affect political and social inequality. American Journal of Political Science, 63(4), 758–773. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12460

- Huggins, R., Stuetzer, M., Obschonka, M., & Thompson, P. (2021). Historical industrialisation, path dependence and contemporary culture: The lasting imprint of economic heritage on local communities. Journal of Economic Geography, 21(6), 841–867. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbab010

- Jedwab, R., Johnson, N. D., & Koyama, M. (2022). The economic impact of the black death. Journal of Economic Literature, 60(1), 132–178. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20201639

- Kristiansen, K. (2000). Europe before history. Cambridge University Press.

- Kuckenburg, M. (2000). Vom Steinzeitlager zur Keltenstadt. Siedlungen der Vorgeschichte in Deutschland. Konrad Theiss.

- Laurence, R. (1999). The roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and cultural change. Routledge.

- Löffl, J. (2014). Negotiatores in Cirta. Sallusts Iugurtha und der Weg in den jugurthinischen Krieg. Frank & Timme.

- Lowes, S., Nunn, N., Robinson, J. A., & Weigel, J. L. (2017). The evolution of culture and institutions: Evidence from the Kuba Kingdom. Econometrica, 85, 1065–1091. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA14139

- Lucas, A. (2005). Wind, water, work. Ancient and medieval milling technology. Koninklijke Brill.

- Mangartz, F. (2008). Römischer Basaltlava-Abbau zwischen Eifel und Rhein. Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum.

- Maraut, S., Dernis, H., Webb, C., Spiezia, V., & Guellec, D. (2008). The OECD REGPAT database: A presentation (OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers No. 2008/02). OECD Publ. https://doi.org/10.1787/241437144144

- Marshall, A. (1920). Principles of economics (8th ed.). Macmillan.

- Martin, R. (2021). Path dependence and the spatial economy: Putting history in Its place. In Handbook of regional science (pp. 1265–1287). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-60723-7_34

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2022). Making history matter more in evolutionary economic geography. ZFW – Advances in Economic Geography, 66(2), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw-2022-0014

- McCormick, M., Huang, G., Zambotti, G., & Lavash, J. (Eds.). (2013). Digital atlas of Roman and medieval civilizations. DARMC, Center for Geographic Analysis, Harvard University.

- Menghin, W. (1995). Kelten, Römer und Germanen. Archäologie und Geschichte in Deutschland. Weltbild.

- Michaels, G., & Rauch, F. (2017). Resetting the urban network: 117–2012. Economic Journal, 128(608), 378–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12424

- Minniti, M. (2005). Entrepreneurship and network externalities. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 57(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2004.10.002

- Nagaoka, S., Motohashi, K., & Goto, A. (2010). Patent statistics as an innovation indicator. In B. H. Hall, & N. Rosenberg (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of innovation (Vol. 2, pp. 1083–1127). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-7218(10)02009-5

- Nunn, N. (2009). The importance of history for economic development. Annual Review of Economics, 1(1), 65–92. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.economics.050708.143336

- Olick, J. K., Vinitzky-Seroussi, V., & Levy, D. (2011). Introduction. In J. K. Olick, V. Vinitzky-Seroussi, & D. Levy (Eds.), The collective memory reader (pp. 3–62). Oxford University Press.

- Opper, S., & Andersson, F. N. G. (2019). Are entrepreneurial cultures stable over time? Historical evidence from China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 36(4), 1165–1192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-018-9573-0

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2005). OECD handbook on economic globalization indicators. OECD.

- Parker, S. C. (2009). Why do small firms produce the entrepreneurs? The Journal of Socio-Economics, 38(3), 484–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2008.07.013

- Planck, D., & Beck, W. (1987). Der Limes in Südwestdeutschland. Konrad Theiss.

- Rieckhoff, S. (2008). Geschichte der Chronologie der Späten Eisenzeit in Mitteleuropa und das Paradigma der Kontinuität (Leipziger Online-Beiträge zur Ur- und Frühgeschichtlichen Archäologie No. 30). https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:15-qucosa2-338709

- Rieckhoff, S., & Biel, J. (Eds.). (2001). Die Kelten in Deutschland. Konrad Theiss.

- Riemer, U. (2006). Die Römische Germanienpolitik. Von Caesar bis Commodus. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Saxenian, A. (1996). Regional advantage: Culture and competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128. Harvard University Press.

- Schallmayer, E. (2011). Der Limes. Geschichte einer Grenze. C.H. Beck.

- Schneider, H. (2005). Einführung in die antike Technikgeschichte. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Schulz, J. F., Bahrami-Rad, D., Beauchamp, J. P., & Henrich, J. (2019). The church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation. Science, 366(6466), eaau5141. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau5141

- Schumann, A. (2014). Persistence of population shocks: Evidence from the occupation of West Germany after World War II. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 6(3), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.6.3.189

- Squicciarini, M., Dernis, H., & Criscuolo, C. (2013). Measuring patent quality: Indicators of technological and economic value. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k4522wkw1r8-en

- Stuetzer, M., Obschonka, M., Audretsch, D. B., Wyrwich, M., Rentfrow, P. J., Coombes, M. J., Shaw-Taylor, L., & Satchel, M. (2016). Industry structure, entrepreneurship, and culture: An empirical analysis using historical coalfields. European Economic Review, 86, 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.08.012

- Taalbi, J. (2022). Innovation with and without patents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.04102.

- Talbert, R. J. A. (Ed.). (2000). Barrington atlas of the Greek and Roman world. Princeton University Press.

- Tavassoli, S., Obschonka, M., & Audretsch, D. B. (2021). Entrepreneurship in cities. Research Policy, 50(7), 104255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2021.104255

- Von Schnurbein, S. (1995). Vom Einfluss Roms auf die Germanen. (Vol. 331). Nordrheinwestfälische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Wahl, F. (2017). Does European development have Roman roots? Evidence from the German Limes. Journal of Economic Growth, 22(3), 313–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-017-9144-0

- Wolters, R. (2011). Die Römer in Germanien. C.H. Beck.

- Wyrwich, M. (2020). Migration restrictions and long-term regional development: Evidence from large-scale expulsions of Germans after the Second World War. Journal of Economic Geography, 20, 481–507. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbz024

- Wyrwich, M., Sternberg, R., & Stuetzer, M. (2019). Failing role models and the formation of fear of entrepreneurial failure: A study of regional peer effects in German regions. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(3), 567–588. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby023

- Zabel, F., Putzenlechner, B., & Mauser, W. (2014). Global agricultural land resources. A high resolution suitability evaluation and its perspectives until 2100 under climate change conditions. PLoS One, 9(9), e114980. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107522

- Zukin, S. (2011). Reconstructing the authenticity of place. Theory and Society, 40(2), 161–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-010-9133-1