ABSTRACT

There is an ongoing dialogue that explores how the global production network and evolutionary economic geography (EEG) literatures can make promising crossovers. This paper aims to contribute to this debate by outlining a theoretical-analytical approach to regional studies on global value chains (GVCs). Building on the EEG literature on relatedness, economic complexity and regional diversification, this approach aims to develop a better understanding of the ability of regions to develop new and upgrade existing GVCs, and why regions may experience the loss or downgrading of existing GVCs. We present the features of this relatedness/complexity approach to GVCs and discuss potential fields of applications.

1. INTRODUCTION

Research on global value chains (GVCs) is currently triggered by global developments that are considered to make major impacts on the spatial organisation of GVCs (Yeung, Citation2024), such as digital technologies (Rehnberg & Ponte, Citation2019), COVID-19 (Bryson & Vanchan, Citation2020; Pahl et al., Citation2022), deglobalisation (Jaax et al., Citation2023)Footnote1 and international geo-political tensions (Bednarski et al., Citation2023; Whiteside et al., Citation2023). Another factor that is boosting GVC research is the public availability of longitudinal datasets, such as the World Input-Output data (Timmer et al., Citation2015, Citation2019) and the OECD Inter-Country Input-Output data (OECD, Citation2021). However, at the subnational scale, this data revolution has not yet occurred. At the urban and regional scale, data issues remain challenging when analysing GVCs, to say the least (Almazán-Gómez et al., Citation2023; Bolea et al., Citation2022; Comotti et al., Citation2020; Hernández Rodríguez et al., Citation2023; Karbevskaa & Hidalgo, Citation2023; Los et al., Citation2017).Footnote2

Despite all this excitement, scholars also observe there has been little theoretical development in the GVC literature in recent years (Kano et al., Citation2020). In the field of economic geography, Yeung (Citation2021) and Boschma (Citation2022) have recently initiated a debate on how the global production network (GPN) and the evolutionary economic geography (EEG) literatures can make promising crossovers and exploit potential synergies. This dialogue has been taken up by others and is ongoing (see e.g., De Propris, Citation2024; Lee, Citation2024; Poon, Citation2024; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2021; Yeung, Citation2024).

This paper aims to contribute to this dialogue by outlining a theoretical-analytical approach to regional studies on GVCs that draws on recent insights in evolutionary economic geography. It combines concepts from literatures on relatedness, economic complexity and regional diversification (Balland et al., Citation2022; Boschma, Citation2017, Citation2022; Hernández Rodríguez et al., Citation2023; Hidalgo, Citation2021; Hidalgo & Hausmann, Citation2009) to study the geography of GVC dynamics. This approach focuses on the ability of regions to develop new GVCs and upgrade existing ones, and why regions may experience the loss or the downgrading of existing GVCs. This necessitates an assessment of potential externalities between the underlying capabilities of all possible value-chain functions and their complexity. In other words, it requires the construction of a measure of relatedness between industry-functions to assess whether industry-functions share similar capabilities (Hernández Rodríguez et al., Citation2023; Ye, Citation2021). And it requires a measure that can assess and compare levels of complexity of industry-functions to determine whether changes in GVCs can be associated with upgrading or downgrading processes in regions (Colozza et al., Citation2021; Hernández Rodríguez et al., Citation2023). Doing so, we aim to introduce a quantitative method to the study of GVCs that incorporates insights from literatures on relatedness (Boschma, Citation2017; Hidalgo et al., Citation2007, Citation2018) and economic complexity (Balland et al., Citation2022; Hidalgo & Hausmann, Citation2009) that is complementary to qualitative approaches on GVCs (Ambos et al., Citation2021; Kano et al., Citation2020).

The paper is structured as follows. The first part will discuss the origins and main features of the relatedness/complexity approach to GVCs. The second part will summarise some of the research questions this framework can address.

2. TOWARDS A RELATEDNESS/COMPLEXITY APPROACH TO GLOBAL VALUE CHAINS

It is not that straightforward to outline the key features of an evolutionary approach to GVCs, evolutionary economics has paid little explicit attention to the study of GVCs so far. If one takes a look at some of the key volumes that have been published on evolutionary economics in the last decades (e.g., Dopfer et al., Citation2024; Dosi et al., Citation1988; Hanusch & Pyka, Citation2007; Nelson et al., Citation2018), one can observe that none of the chapters devote explicit attention to global value chains. In other words, it is fair to say that GVCs has remained a rather peripheral topic to this field of thinking in economics.

The same applies to the field of EEG (Boschma & Frenken, Citation2006, Citation2018; Martin & Sunley, Citation2006) where GVCs have not been a key research topic. Having said that, Boschma (Citation2022) identified significant crossovers between EEG and GVCs, most notably in the influential literature on global production networks (Coe & Yeung, Citation2015; MacKinnon, Citation2012; Yeung, Citation2015, Citation2021; Yeung & Coe, Citation2015), with their focus on the dynamic interplay between strategic needs of lead firms and regional assets on the one hand, and the vast literature on clusters and upgrading linked to GVCs on the other hand (Giuliani et al., Citation2005; Morrison et al., Citation2008; Pietrobelli & Rabellotti, Citation2011).

More recently, there is a nascent literature on value chains (VCs) that draws insights from the evolutionary literature on related/unrelated diversification in regions (Boschma, Citation2022; Yeung, Citation2021). Following the seminal work of Hidalgo et al. (Citation2007), the focus of the regional diversification literature in EEG is to understand the ability of regions to diversify into new activities of many kinds, such as industries (Neffke et al., Citation2011), products (Boschma et al., Citation2013), technologies (Kogler et al., Citation2013; Rigby, Citation2015), occupations (Muneepeerakul et al., Citation2013), scientific topics (Boschma et al., Citation2014) and trademarks (Castaldi & Drivas, Citation2023; Drivas, Citation2022). A key finding is that, in all these cases, regions tend to diversify into activities closely related to their existing activities (Boschma, Citation2017; Hidalgo et al., Citation2018). This can be attributed to the fact that moving into a new activity is risky and costly, as capabilities (knowledge, skills, institutions) need to be developed and adapted. Such costs will be lower the higher the fit between capabilities required for the new activity and the local supply of capabilities: the more related they are, the less risky and costly it is to develop this new activity.

Another key finding in this literature is that the economic benefits of diversification will be higher the more complex the new activities are (Hidalgo & Hausmann, Citation2009; Maskell & Malmberg, Citation1999; Rigby et al., Citation2022). Complex activities combine many capabilities, which makes it hard for other regions to master, develop and produce them. This is different from low-complex activities that depend on capabilities that can be mastered by many regions, which implies their economic value is also much lower (Balland & Rigby, Citation2017).

In the following, we propose to apply such a relatedness/complexity framework (Balland et al., Citation2019; Buyukyazicia et al., Citation2023; Rigby et al., Citation2022) to regional studies on GVCs. An evolutionary take on GVCs would start arguing that history matters when explaining GVC dynamics at the regional scale. More in particular, it would claim that the ability of regions to develop complex VCs and upgrade existing VCs is likely to depend on the degree of relatedness with pre-existing VCs in regions.

To explain GVC dynamics in regions from a relatedness framework, it is useful to focus on region-industry-functions that account for potential combinations of horizontal and vertical upgrading (Ye, Citation2021). Doing so, one accounts for what is produced or exported in the region, but also for what is actually done (in terms of tasks or functions) when producing or exporting (Timmer et al., Citation2019). This allows us to test whether the development of a new VC (the formation of a new industry, also known as horizontal upgrading), a new function in an existing VC (the establishment of a new R&D or management function, also known as vertical upgrading) or a new industry-function (a new function in a new industry) depends on the local presence of related VCs (e.g., moving from mobile phones to laptops), related functions (e.g., moving from management to R&D in laptops) and related industry-functions (e.g., moving from management in mobile phones to R&D in laptops), respectively.

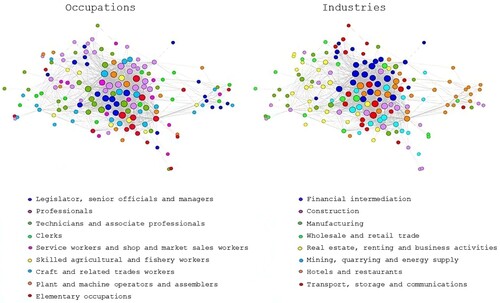

To assess whether the principle of relatedness is underlying the dynamics of GVCs in regions, one first needs to determine the degree of relatedness between industry-functions in GVCs.Footnote3 Following the product space concept of Hidalgo et al. (Citation2007), a network of industry-functions can be constructed based on geographical co-occurrence (Ye, Citation2021). This measures the extent to which industry-functions (such as R&D in textiles, management in computers, production of cars) share similar capabilities. shows the industry-function space of Europe, in which functions are proxied by occupations (see Hernández Rodríguez et al., Citation2023). Each node represents an industry-function. If two industry-functions are linked, they are related above a certain threshold, meaning the industry-functions rely on similar (but not identical) capabilities. The two networks shown in are the same, but the network on the left highlights the occupations, while the network on the right marks the industries concerned. So the node on the top of the figure represents the industry-function of technicians and associate professionals in the transport, storage and communication industry. What is typical about this industry-function space is a core of industry-functions that are tightly connected to each other. But there are also industry-functions that are poorly connected, or not connected at all, signalling they share similar capabilities with only a small number of other industry-functions.

Figure 1. An example of the industry-function space in Europe.

Source: Hernández Rodríguez et al. (Citation2023).

When the relatedness between all industry-functions have been determined, the next step is to position regions in this industry-function space, to identify in what industry-functions regions are specialised and to determine how many and what kind of diversification opportunities regions have in terms of upgrading their GVCs. If a region is specialised in many industry-functions in the core of this network, it would imply it has plenty of options to diversify into new industry-functions related to existing industry-functions in the region. This is different from a region that is specialised in a small number of industry-functions in the periphery of the network, which would indicate the region has little diversification opportunities.

So far we mentioned upgrading of GVCs, but what does upgrading exactly mean in our evolutionary approach to GVCs? The GVC literature (Giuliani et al., Citation2005; Humphrey & Schmitz, Citation2002; Parrilli et al., Citation2011; Ponte & Ewert, Citation2009) often refers to upgrading in terms of entering new industries and functions along a value chain that provide higher value added. In that context, the value added of functions tends to be pre-ranked, like functions such as R&D and marketing are considered to have higher levels of value added than manufacturing or distribution. A prime example is the so-called ‘smiling curve’, in which functions at the early and late stages of a value chain are considered to have the highest value added (Shin et al., Citation2012; Stöllinger, Citation2021). However, such rankings might be obvious for some but rather arbitrary in other functions (Hernández Rodríguez et al., Citation2023). For instance, it is not entirely clear why moving from manufacturing to sales/after sales is necessarily associated with upgrading. This is even harder to determine for shifts across industries: does a move from laptops to mobile phones imply upgrading or not? And how to compare all the possible industry-functions: would a shift from marketing in laptops to design in mobile phones indicate a process of upgrading or downgrading?

One way of dealing with this (but definitely not the only way) is to differentiate between industry-functions in terms of their complexity, following the seminal work of Hidalgo and Hausmann (Citation2009) on economic complexity (Koch, Citation2021). In our context, complexity captures the difficulty of mastering capabilities that are needed to excel in an industry-function. Following Hidalgo and Hausmann (Citation2009), this can be measured by the non-ubiquity of industry-functions on the one hand, and the diversity of capabilities that need to be combined in industry-functions on the other hand. This measure will result in a complete list of all industry-functions in terms of their complexity scores. Such a measure would indicate whether, for instance, management in laptops is more complex than R&D in mobile phones. Another advantage of such a measure is that it can account for the fact that the complexity of industry-functions can change over time, due to technological change (like robotisation or AI), or processes of standardisation and ubiquitification (Maskell & Malmberg, Citation1999).

3. POTENTIAL CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE STUDY OF THE GEOGRAPHY OF GLOBAL VALUE CHAINS

So far, we briefly outlined how to characterise industry-functions in GVCs in terms of the capabilities they share with others (based on the relatedness scores of each pair of industry-functions) and their levels of complexity (in terms of how difficult it is to master the underlying capabilities of each industry-function). Following the Balland et al. (Citation2019) relatedness/complexity framework, this reveals crucial information of how costly (relatedness) and economically beneficial (complexity) it might be for a region to develop a specific industry-function. Some new industry-functions might be feasible to develop, while others might not, just because relevant capabilities are missing in the region. Following this relatedness/complexity framework opens up a number of potential contributions to the study of the geography of GVCs, which will be briefly discussed below.

The relatedness/complexity framework on GVCs could contribute to a better understanding of the evolution of uneven development. The framework allows us to determine the position of each region in the industry-function space. This would provide insights on what the opportunity set in a region is to develop new industry-functions. Each region will differ in that respect, as regions accumulate different sets of capabilities over time. Local capabilities provide opportunities to regions to upgrade their participation in GVCs and to diversify into complex industry-functions in particular, but they also set serious limits to what can be achieved in this upgrading process.

Introducing such an evolutionary approach in GVC studies would also have the potential to shed light on regional diversification from a GVC perspective. It would provide a conceptual framework and methodological tool to assess the ability of regions to participate in new industry-functions, depending on the degree of relatedness with pre-existing industry-functions in a region. Such a focus on externalities across industry-functions highlights the role of capabilities specific to the development of GVCs that would be complementary to other capabilities that are technology-, industry-, occupation- and trademark-specific (Boschma, Citation2017). In that sense, it takes up an additional dimension of GVC capabilities to explain regional diversification that has not yet been accounted for before.

A relatedness/complexity framework on GVCs could also provide additional insights to the low value added trap literature (MacKinnon, Citation2012; Phelps et al., Citation2003; Stöllinger, Citation2019). An evolutionary approach to GVCs would suggest that local capabilities in GVCs might become an obstacle for diversification in regions and limit the capacity of regions to upgrade their GVCs and to diversify into complex industry-functions. Following Hartmann et al. (Citation2021) and Pinheiro et al. (Citation2022), this GVC perspective allows the identification of whether regions might become trapped in low-complex industry-functions because they lack diversification opportunities in high-complex industry-functions, due to a low degree of relatedness with high-complex industry-functions. In other words, they miss the relevant capabilities to move up the GVC ladder and therefore, they get stuck in low-complex, value added, traps (see also Ye, Citation2021).

Such a relatedness/complexity approach to GVCs could also shed light on the question of whether such dynamics in GVCs would favour high-income regions, rather than low-income regions, and thus have the potential to widen regional inequalities. Pinheiro et al. (Citation2022) applied such a relatedness/complexity framework to the potential of regions to diversify in complex technologies or industries and found that this potential is not evenly distributed across regions. Their study found that high-income regions often have a high potential to diversify into complex activities, while low-income regions rely more on related activities of low-complexity when diversifying (Pinheiro et al., Citation2022). Given the higher economic potential of complex activities (Pintar & Scherngell, Citation2020; Rigby et al., Citation2022), this implies income disparities across regions are more likely to be reinforced due to diversification processes. This still needs to be tested in the case of GVCs. One might expect that high-income regions often find themselves in the core of the industry-function space of where the most complex industry-functions are also most likely to be found. This implies they have many options to develop complex industry-functions that would strengthen further their leading economic positions. Instead, low-income regions might find them positioned more often in the periphery of the industry-function space where low-complex industry-functions are also more likely to be found. If this would be the case, low-income regions would have little diversification opportunities to move into complex industry-functions.

Another field of application of the relatedness/complexity approach to GVC is to examine the impact of inter-regional VC linkages on upgrading in regions. In the GVC literature, there have been many studies assessing the effect of GVC participation on upgrading processes in countries and regions, with mixed outcomes (see e.g., De Marchi et al., Citation2018; Pahl & Timmer, Citation2020; Tajoli & Felice, Citation2018). This shows a resemblance to studies that examined the role of inter-regional linkages for innovation (Ascani et al., Citation2020; Barzotto et al., Citation2019; Fitjar & Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2011; Grillitsch & Nilsson, Citation2015; Kogler et al., Citation2023; Miguelez & Moreno, Citation2015, Citation2018; Trippl et al., Citation2018). Inspired by Boschma and Iammarino (Citation2009), it may be argued that VC linkages per se do not contribute to functional upgrading, but VC linkages that offer access to complementary capabilities across regions would matter (Balland & Boschma, Citation2021). This requires that one has to be specific about which capabilities would enhance the probability of a region to diversify into a new industry-function (i.e., identify the capabilities related to the new industry-function), which of those are missing in the region and which other regions could provide access to those. VC linkages with regions that provide access to complementary capabilities that are needed to develop a complex industry-function but are missing in a region would then increase the likelihood of the region to diversify successfully into the complex industry-function and thus foster functional upgrading in GVCs (Hernández-Rodríguez et al., Citation2024; Sebestyén et al., Citation2024). This interplay between regional capabilities and external linkages comes close to the dialectical approach proposed by Yeung (Citation2024) in which branching of regional actors into related industries is reinforced by their strategic coupling with extra-regional networks. This also shows a resemblance with the work of Binz et al. (Citation2016) that depict the rise of GVCs in places being a result of the interplay between building local capabilities (including legitimacy and institutions) and mobilising resources globally.

As discussed above, a key claim of the relatedness/complexity approach to GVCs would be that the ability of regions to develop new complex VCs and upgrade existing VCs would depend on the degree of relatedness with pre-existing VCs in regions. Preliminary results show this is indeed the case (Cortinovis et al., Citation2020; Hernández Rodríguez et al., Citation2023). But as many of these GVCs are heavily influenced by the investments of multinational companies (Crescenzi et al., Citation2014 Crescenzi & Iammarino, Citation2017; Iammarino & McCann, Citation2013), the question is whether these investments may also induce processes of unrelated diversification, as demonstrated by Neffke et al. (Citation2018) and Elekes et al. (Citation2019). This could be a key question to take up in future research when applying the relatedness/complexity approach to GVCs.

The relatedness/complexity framework could also trigger new thinking of how GVCs can be better integrated in the design of regional innovation policies (Comotti et al., Citation2020; Dannenberg et al., Citation2018). An evolutionary take on regional policy would advocate that policies need to be adapted to place-specific capabilities (Alshamsi et al., Citation2018; Balland et al., Citation2019; D’Adda et al., Citation2020) but it is not immediately clear how to link this to GVCs (Brennan & Rakhmatullin, Citation2015). The relatedness-complexity approach could offer a framework and tool to identify EU partner regions that can provide complementary capabilities to regions that want to upgrade their GVCs. This approach can identify untapped learning opportunities for regions involved in GVCs, following the method proposed by Balland and Boschma (Citation2021). This method has been adopted, for instance, by Bachtrögler-Unger et al. (Citation2023) to identify complementarities across European regions to promote the twin transition. This study found a strong national bias in many inter-regional collaborations that prevents the exploitation of complementary capabilities that require international collaborations across regions in Europe. Our framework on GVCs may be of special interest to policymakers that aim to promote regional collaborations in their Smart Specialisation Strategies, which has remained a major challenge so far (Barzotto et al., Citation2019; Giustolisi et al., Citation2023; Iacobucci & Guzzini, Citation2016; Radosevic & Ciampi Stankova, Citation2015; Uyarra et al., Citation2018). In this context, policy could support the exploitation of regional capabilities and the making of connections to complementary capabilities in other regions in order to promote functional upgrading of GVCs in regions.

The relatedness/complexity approach also offers a united framework to study processes of upgrading and downgrading of GVCs in regions. There is an increasing focus on (economic, social and environmental) downgrading processes in regional studies in GVCs (Bair & Werner, Citation2011; Blažek, Citation2016; Blažek et al., Citation2020; Gereffi, Citation2019; Krishnan et al., Citation2023; Phelps et al., Citation2018; Plank & Staritz, Citation2015). A relatedness/complexity framework to economic downgrading in GVCs could investigate which industry-functions are shrinking or disappearing in regions, and whether these concern industry-functions of high complexity. Preliminary evidence tends to suggest that complex industry-functions are more likely to exit a region when positive externalities from local industry-functions are missing (Hernández Rodríguez et al., Citation2023). These concern industry-functions that are not strongly anchored or embedded in local capabilities, and therefore have a higher risk to decline and disappear.

A final question that has been rightly put forward by Yeung (Citation2024) is to develop more understanding of the role of institutions and geo-political developments for GVCs in regional settings. The GPN literature has made important contributions in this respect, especially linking it to the role of lead firms in GVCs, and how lead firms shape assets in their host regions including local institutions. The role of the social, political and institutional context is still understudied in regional diversification (Boschma & Capone, Citation2015), and especially how local institutional agents and lead firms interact in this process, which has important implications for regional development (Boschma, Citation2022; MacKinnon et al., Citation2019). This makes it crucial to better understand how unfavourable regional institutional settings, like low quality of government, can act as a barrier to upgrading processes in GVCs (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2021). Another promising research avenue is the extent to which institutional complementarities can make a difference in diversification processes (Boschma, Citation2024). When applied to regional studies in GVCs, it would revolve around questions like whether prevailing institutions specific to existing industry-functions in regions can enable the development of new industry-functions that require similar institutions, and whether these prevailing institutions can facilitate a process of institutional change that is required to develop new industry-functions in GVCs. This would add a new and promising layer in regional studies to GVCs that has remained relatively unexplored so far.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author

Notes

1. Jaax et al. (Citation2023), for instance, found no general trends of deglobalisation, regionalisation of value chains and reshoring in the period up to 2020.

2. A novel and promising way to map GVCs has been proposed by Karbevskaa and Hidalgo (Citation2023) who inferred detailed product-level VC linkages from fine-grained international trade data.

3. Input-output data have also been used to derive an indicator of relatedness between industries (see e.g., Essleztbichler, Citation2015).

REFERENCES

- Almazán-Gómez, M. A., Llano, C., Pérez, J., & Mandras, G. (2023). The European regions in the global value chains: New results with new data. Papers in Regional Science, 102(6), 1097–1126. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12760

- Alshamsi, A., Pinheiro, F. L., & Hidalgo, C. A. (2018). Optimal diversification strategies in the networks of related products and of related research areas. Nature Communications, 9(1), 1328. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03740-9

- Ambos, B., Brandl, K., Perri, A., Scalera, V. G., & Van Assche, A. (2021). The nature of innovation in global value chains. Journal of World Business, 56(4), 101221. forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2021.101221

- Ascani, A., Bettarelli, L., Resmini, L., & Balland, P. A. (2020). Global networks, local specialisation and regional patterns of innovation. Research Policy, 49(8), 104031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.104031

- Bachtrögler-Unger, J., Balland, P. A., Boschma, R., & Schwab, T. (2023). Technological capabilities and the twin transition in Europe. Opportunities for regional collaboration and economic cohesion, report, Bertelsmann Stiftung, Berlin, 82.

- Bair, J., & Werner, M. (2011). Guest editorial – commodity chains and the uneven geographies of global capitalism: A disarticulations perspective. Environment and Planning A, 43(5), 988–997. https://doi.org/10.1068/a43505

- Balland, P. A., Boschma, R., Crespo, J., & Rigby, D. (2019). Smart specialization policy in the EU: Relatedness, knowledge complexity and regional diversification. Regional Studies, 53(9), 1252–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1437900

- Balland, P. A., Broekel, T., Diodato, D., Giuliani, E., Hausmann, R., O’Clery, N., & Rigby, D. (2022, April). The new paradigm of economic complexity. Research Policy, 51(3), 104450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2021.104450

- Balland, P. A., & Rigby, D. L. (2017). The geography of complex knowledge. Economic Geography, 93(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2016.1205947

- Balland, P., & Boschma, R. (2021). Complementary inter-regional linkages and smart specialisation. An empirical study on European regions. Regional Studies, 55(6), 1059–1070. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1861240

- Barzotto, M., Corradini, C., Fai, F. M., Labory, S., & Tomlinson, P. R. (2019). Enhancing innovative capabilities in lagging regions: An extra-regional collaborative approach to RIS3. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsz003

- Bednarski, L., Roscoe, S., Blome, C., & Schlep, M. C. (2023). Geopolitical disruptions in global supply chains: A state-of-the-art literature review. Production Planning and Control. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2023.2286283

- Binz, C., Truffer, B., & Coenen, L. (2016). Path creation as a process of resource alignment and anchoring – industry formation for on-site water recycling in Beijing. Economic Geography, 92(2), 172–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1103177

- Blažek, J. (2016). Towards a typology of repositioning strategies of GVC/GPN suppliers: The case of functional upgrading and downgrading. Journal of Economic Geography, 16(4), 849–869. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbv044

- Blažek, J., Květoň, V., Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., & Trippl, M. (2020). The dark side of regional industrial path development: Towards a typology of trajectories of decline. European Planning Studies, 28(8), 1455–1473. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1685466

- Bolea, L. R., Duarte, G. J. D., Hewings, S. J., & Sánchez-Chóliz, J. (2022). The role of regions in global value chains: An analysis for the European Union. Papers in Regional Science, 101(4), 771–794. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12674

- Boschma, R. (2017). Relatedness as driver behind regional diversification: A research agenda. Regional Studies, 51(3), 351–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1254767

- Boschma, R. (2022). Global value chains from an evolutionary economic geography perspective: A research agenda. Area Development and Policy, 7(2), 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2022.2040371

- Boschma, R. (2024). Exploring the concept of institutional relatedness and potential applications, unpublished manuscript.

- Boschma, R. A., & Frenken, K. (2006). Why is economic geography not an evolutionary science? Towards an evolutionary economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(3), 273–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbi022

- Boschma, R. A., & Iammarino, S. (2009). Related variety, trade linkages, and regional growth in Italy. Economic Geography, 85(3), 289–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01034.x

- Boschma, R., & Capone, G. (2015). Institutions and diversification: Related versus unrelated diversification in a varieties of capitalism framework. Research Policy, 44(10), 1902–1914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.06.013

- Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2018). Evolutionary economic geography. In G. Clarke, M. Feldman, M. Gertler, & D. Wojcik (Eds.), New Oxford handbook of economic geography, Chapter 11 (pp. 213–229). Oxford University Press.

- Boschma, R., Heimeriks, G., & Balland, P. A. (2014). Scientific knowledge dynamics and relatedness in biotech cities. Research Policy, 43(1), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.07.009

- Boschma, R., Minondo, A., & Navarro, M. (2013). The emergence of new industries at the regional level in Spain: A proximity approach based on product relatedness. Economic Geography, 89(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2012.01170.x

- Brennan, L., & Rakhmatullin, R. (2015). Global value chains and smart specialisation strategy: Thematic work on the understanding of global value chains and their analysis within the context of smart specialisation, EUR 27649 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- Bryson, J. R., & Vanchan, V. (2020). COVID-19 and alternative conceptualisations of value and risk in GPN research. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 111(3), 530–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12425

- Buyukyazicia, D., Mazzonia, L., Riccabonia, M., & Serti, F. (2023). Workplace skills as regional capabilities: Relatedness, complexity and industrial diversification of regions. Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2023.2206868

- Castaldi, C., & Drivas, K. (2023). Relatedness, cross-relatedness and regional innovation specializations: An analysis of technology, design, and market activities in Europe and the US. Economic Geography, 99(3), 253–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2023.2187374

- Coe, N. M., & Yeung, H. W. (2015). Global production networks: Theorizing economic development in an interconnected world. Oxford University Press.

- Colozza, F., Boschma, R., Morrison, A., & Pietrobelli, C. (2021). The importance of global value chains and regional capabilities for the economic complexity of EU-regions, Papers in evolutionary economic geography, no. 21.39, Utrecht University, Utrecht.

- Comotti, S., Crescenzi, R., & Iammarino, S. (2020). Foreign direct investment, global value chains and regional economic development in Europe, report, European Commission, DG Regional and Urban Policy, Brussels.

- Cortinovis, N., Crescenzi, R., & van Oort, F. (2020). Multinational enterprises, industrial relatedness and employment in European regions. Journal of Economic Geography, 20(5), 1165–1205. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbaa010

- Crescenzi, R., & Iammarino, S. (2017). Global investments and regional development trajectories: The missing links. Regional Studies, 51(1), 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1262016

- Crescenzi, R., Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2014). Innovation drivers, value chains and the geography of multinational corporations in Europe. Journal of Economic Geography, 14(6), 1053–1086. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbt018

- D’Adda, D., Iacobucci, D., & Palloni, R. (2020). Relatedness in the implementation of smart specialisation strategy: A first empirical assessment. Papers in Regional Science, 99(3), 405–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12492

- Dannenberg, P., Revilla Diez, J., & Schiller, D. (2018). Spaces for integration or a divide? New-generation growth corridors and their integration in global value chains in the Global South. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie, 62(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw-2017-0034

- De Marchi, V., Giuliani, E., & Rabellotti, R. (2018). Do global value chains offer developing countries learning and innovation opportunities? The European Journal of Development Research, 30(3), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-017-0126-z

- De Propris, L. (2024). Globalisation must work for as many regions as possible. Regional Studies. forthcoming.

- Dopfer, K., Nelson, R. R., Potts, J., & Pyka, A. (2024). Routledge handbook of evolutionary economics. Routledge.

- Dosi, G., Freeman, C., Nelson, R., Silverberg, G., & Soete, L. (1988). Technical change and economic theory. Pinter Publishers.

- Drivas, K. (2022). The role of technology and relatedness in regional trademark activity. Regional Studies, 56(2), 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1808883

- Elekes, Z., Boschma, R., & Lengyel, B. (2019). Foreign-owned firms as agents of structural change in regions. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1603–1613. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1596254

- Essleztbichler, J. (2015). Relatedness, industrial branching and technological cohesion in US metropolitan areas. Regional Studies, 49(5), 752–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.806793

- Fitjar, R. D., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2011). When local interaction does not suffice: Sources of firm innovation in urban Norway. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 43(6), 1248–1267. https://doi.org/10.1068/a43516

- Gereffi, G. (2019). Economic upgrading in global value chains. In S. Ponte, G. Gereffi, & G. Raj-Reichert (Eds.), Handbook on global value chains (pp. 240–254). Edward Elgar.

- Giuliani, E., Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2005). Upgrading in global value chains: Lessons from Latin American clusters. World Development, 33(4), 549–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.01.002

- Giustolisi, A., Benner, M., & Trippl, M. (2023). Smart specialisation strategies: Towards an outward-looking approach. European Planning Studies, 31(4), 738–757. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2022.2068950

- Grillitsch, M., & Nilsson, M. (2015). Innovation in peripheral regions: Do collaborations compensate for a lack of local knowledge spillovers? The Annals of Regional Science, 54(1), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-014-0655-8

- Hanusch, H., & Pyka, A. (2007). Elgar companion to neo-schumpeterian economics. Edward Elgar.

- Hartmann, D., Zagato, L., Gala, P., & Pinheiro, F. L. (2021). Why did some countries catch-up, while others got stuck in the middle? Stages of productive sophistication and smart industrial policies. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 58, 1–13. forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2021.04.007

- Hernández Rodríguez, E., Boschma, R., Morrison, A., & Ye, X. (2023). Functional upgrading in global value chains. Evidence from EU regions using a relatedness/complexity framework. Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography, no. 23.16, Utrecht University, Utrecht.

- Hernández-Rodríguez, E., Boschma, R., Morrison, A., & Ye, X. (2024). Functional upgrading and downgrading in global value chains: The role of complementary interregional value chain linkages in EU regions, working paper.

- Hidalgo, C. A. (2021). Economic complexity theory and applications. Nature Reviews Physics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-020-00275-1.

- Hidalgo, C. A., Klinger, B., Barabasi, A. L., & Hausmann, R. (2007). The product space and its consequences for economic growth. Science, 317(5837), 482–487. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1144581

- Hidalgo, C., Balland, P. A., Boschma, R., Delgado, M., Feldman, M., Frenken, K., Glaeser, E., He, C., Kogler, D., Morrison, A., Neffke, F., Rigby, D., Stern, S., Zheng, S., & Zhu, S. (2018). The principle of relatedness. Springer Proceedings in Complexity, 451–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96661-8_46

- Hidalgo, C., & Hausmann, R. (2009). The building blocks of economic complexity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(26), 10570–5. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0900943106

- Humphrey, J., & Schmitz, H. (2002). How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Regional Studies, 36(9), 1017–1027. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340022000022198

- Iacobucci, D., & Guzzini, E. (2016). Relatedness and connectivity in technological domains: Missing links in S3 design and implementation. European Planning Studies, 24(8), 1511–1526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1170108

- Iammarino, S., & McCann, P. (2013). Multinationals and economic geography. Edward Elgar.

- Jaax, A., Miroudot, S., & van Lieshout, E. (2023). Deglobalisation? The reorganisation of GVCs in a changing world, OECD Trade Policy Paper, April, n°272.

- Kano, L., Tsang, E. W. K., & Yeung, H. W. (2020). Global value chains: A review of the multi-disciplinary literature. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(4), 577–622. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00304-2

- Karbevskaa, L., & Hidalgo, C. A. (2023). Mapping global value chains at the product level, arXiv:2308.02491v1 [econ.GN] 12 Jun 2023, 10 pages.

- Koch, P. (2021). Economic complexity and growth: Can value-added exports better explain the link? Economics Letters, 198, 109682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2020.109682

- Kogler, D. F., Rigby, D. L., & Tucker, I. (2013). Mapping knowledge space and technological relatedness in US cities. European Planning Studies, 21(9), 1374–1391. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.755832

- Kogler, D. F., Whittle, A., Kim, K., & Lengyel, B. (2023). Understanding regional branching: Knowledge diversification via inventor and firm collaboration networks. Economic Geography, 99(5), 471–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2023.2242551

- Krishnan, A., De Marchi, V., & Ponte, S. (2023). Environmental upgrading and downgrading in global value chains: A framework for analysis. Economic Geography, 99(1), 25–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2022.2100340

- Lee, N. (2024). Global production networks meet evolutionary economic geography. Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2024.2316175.

- Los, B., Lankhuizen, M., & Thissen, M. (2017). New measures of regional competitiveness in a globalizing world. In P. McCann, F. van Oort, & J. Goddard (Eds.), The empirical and institutional dimensions of smart specialisation (pp. 105–126). Routledge.

- MacKinnon, D. (2012). Beyond strategic coupling: Reassessing the firm-region nexus in global production networks. Journal of Economic Geography, 12(1), 227–245. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbr009

- MacKinnon, D., Dawley, S., Pike, A., & Cumbers, A. (2019). Rethinking path creation: A geographical political economy approach. Economic Geography, 95(2), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Maskell, P., & Malmberg, A. (1999). The competitiveness of firms and regions: ‘Ubiquitification’ and the importance of localized learning. European Urban and Regional Studies, 6(1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977649900600102

- Miguelez, E., & Moreno, R. (2015). Knowledge flows and the absorptive capacity of regions. Research Policy, 44(4), 833–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.01.016

- Miguelez, E., & Moreno, R. (2018). Relatedness, external linkages and regional innovation in Europe. Regional Studies, 52(5), 688–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1360478

- Morrison, A., Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2008). Global value chains and technological capabilities: A framework to study learning and innovation in developing countries. Oxford Development Studies, 36(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600810701848144

- Muneepeerakul, R., Lobo, J., Shutters, S. T., Gomez-Lievano, A., & Qubbaj, M. R. (2013). Urban economies and occupation space: Can they get ‘there’ from ‘here’? PLoS One, 8(9), e73676. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073676

- Neffke, F., Hartog, M., Boschma, R., & Henning, M. (2018). Agents of structural change. The role of firms and entrepreneurs in regional diversification. Economic Geography, 94(1), 23–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2017.1391691

- Neffke, F., Henning, M., & Boschma, R. (2011). How do regions diversify over time? Industry relatedness and the development of new growth paths in regions. Economic Geography, 87(3), 237–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2011.01121.x

- Nelson, R. R., Dosi, G., Helfat, C., Pyka, A., Saviotti, P. P., Lee, K., Dopfer, K., Malerba, F., & Winter, S. (2018). Modern evolutionary economics. Cambridge University Press.

- OECD. (2021). OECD inter-country input-output database’.

- Pahl, S., Brandi, C., Schwab, J., & Stender, F. (2022). Cling together, swing together: The contagious effects of COVID-19 on developing countries through global value chains. The World Economy, 45(2), 539–560. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13094

- Pahl, S., & Timmer, M. P. (2020). Do global value chains enhance economic upgrading? A long view. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(9), 1683–1705. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1702159

- Parrilli, M. D., Nadvi, K., & Yeung, H. W.-C. (2011). Local and regional development in global value chains, production networks and innovation networks: A comparative review and the challenges for future research. European Planning Studies, 21(7), 967–988. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.733849

- Phelps, N. A., MacKinnon, D., Stone, I., & Braidford, P. (2003). Embedding the multinationals? Institutions and the development of overseas manufacturing affiliates in Wales and north east England. Regional Studies, 37(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340022000033385

- Phelps, N., Atienza, M., & Arias, M. (2018). An invitation to the dark side of economic geography. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50(1), 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17739007

- Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2011). Global value chains meet innovation systems: Are there learning opportunities for developing countries. World Development, 39(7), 1261–1269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.05.013

- Pinheiro, F. L., Balland, P. A., Boschma, R., & Hartmann, D. (2022). The dark side of the geography of innovation: Relatedness, complexity, and regional inequality in Europe. Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2106362

- Pintar, N., & Scherngell, T. (2020). The complex nature of regional knowledge production: Evidence on European regions. Research Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.104170

- Plank, L., & Staritz, C. (2015). Global competition, institutional context, and regional production networks: Up- and downgrading experiences in Romania’s apparel industry. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(3), 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsv014

- Ponte, S., & Ewert, J. (2009). Which way is “up” in upgrading? Trajectories of change in the value chain for South African wine. World Development, 37(10), 1637–1650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.03.008

- Poon, J. P. H. (2024). Regional capability, evolutionary economic geography and global production networks. Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2024.2316177

- Radosevic, S., & Ciampi Stankova, K. (2015). External dimensions of smart specialization. Opportunities and challenges for trans-regional and transnational collaboration in the EU-13, Joint Research Centre S3 Working paper series, N° JRC96030, ISSN 1831-9408.

- Rehnberg, M., & Ponte, S. (2019). From smiling to smirking? 3D printing, upgrading and the restructuring of global value chains. Global Networks, 18(1), 57–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12166

- Rigby, D. (2015). Technological relatedness and knowledge space: Entry and exit of US cities from patent classes. Regional Studies, 49(11), 1922–1937. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.854878

- Rigby, D. L., Roesler, C., Kogler, D., Boschma, R., & Balland, P. A. (2022). Do EU regions benefit from smart specialisation principles? Regional Studies, 56(12), 2058–2073. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2032628

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2021). Costs, incentives, and institutions in bridging evolutionary economic geography and global production networks. Regional Studies, 55(6), 1011–1014. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1914833

- Sebestyén, T., Braun, E., & Elekes, Z. (2024). Resolving the complexity puzzle: economic complexity and positions in global value chains jointly explain economic development, Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography, no. 24.01, Utrecht University, Utrecht.

- Shin, N., Kraemer, K. L., & Dedrick, J. (2012). Value capture in the global electronics industry: Empirical evidence for the “smiling curve” concept. Industry and Innovation, 19(2), 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2012.650883

- Stöllinger, R. (2019). Functional specialisation in global value chains and the middle-income trap, Research report 441, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Vienna.

- Stöllinger, R. (2021). Testing the smile curve: Functional specialisation and value creation in GVCs. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 56, 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2020.10.002

- Tajoli, L., & Felice, G. (2018). Global value chains participation and knowledge spillovers in developed and developing countries: An empirical investigation. The European Journal of Development Research, 30(3), 505–532. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-017-0127-y

- Timmer, M. P., Dietzenbacher, E., Los, B., Stehrer, R., & de Vries, G. J. (2015). An illustrated user guide to the world input-output database: The case of global automotive production. Review of International Economics, 23(3), 575–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/roie.12178

- Timmer, M. P., Miroudot, S., & de Vries, G. J. (2019). Functional specialization in trade. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby056

- Trippl, M., Grillitsch, M., & Isaksen, A. (2018). Exogenous sources of regional industrial change: Attraction and absorption of nonlocal knowledge for new path development. Progress in Human Geography, 42(2), 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517700982

- Uyarra, E., Marzocchi, C., & Sorvik, J. (2018). How outward looking is smart specialisation? Rationales, drivers and barriers. European Planning Studies, 26(12), 2344–2363. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1529146

- Whiteside, H., Alami, I., Dixon, A., & Peck, J. (2023). Making space for the new state capitalism, part I: Working with a troublesome category. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 55(1), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X221140186

- Ye, X. (2021). Task space: the shift of comparative advantage in globalized production, unpublished work.

- Yeung, H. W. (2015). Regional development in the global economy: A dynamic perspective of strategic coupling in global production networks. Regional Science Policy and Practice, 7(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12055

- Yeung, H. W. (2021). Regional worlds: From related variety in regional diversification to strategic coupling in global production networks. Regional Studies, 55(6), 998–1010. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1857719

- Yeung, H. W. (2024). From regional to global and back again? A future agenda for regional evolution and (de)globalized production networks in regional studies. Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2024.2316856

- Yeung, H. W., & Coe, N. M. (2015). Toward a dynamic theory of global production networks. Economic Geography, 91(1), 29–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecge.12063